Abstract

Manufacturing of metallic components using additive manufacturing technique is of great interest for the industrial applications. Here, the mechanical and microstructural responses of a 316 L stainless steel (316LSS) built by selective laser melting (SLM) with XOY and XOZ directions were revealed by performing in situ neutron diffraction tensile tests. The tensile strength of the XOY-printed samples reaches 700 MPa, while the tensile strength of the XOZ-printed samples is less than 600 MPa. The as-printed 316LSS exhibits anisotropy in tensile property due to the formation of different fractions of nano-sized dimples, twin boundaries, diffraction peak and lattice constants during tensile tests at room temperature. Therefore, choosing right printing direction plays a vital role in forming of metal parts using SLM for further application.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, with the rapid development of advanced manufacturing technology, selective laser melting (SLM), as an additive manufacturing (AM) technique, has attracted much attention due to its ability to directly fabricate complex-shaped parts from 3D model data1,2,3,4. In industries such as aerospace, medical devices, and automotive manufacturing, the demand for high-performance metal materials is increasing, making the research on SLM-formed metal materials of great practical significance and application value2,5,6,7,8,9. Among them, 316 L stainless steel (316LSS), as an alloy material with corrosion resistance and high-temperature resistance10,11,12,13,14, is particularly crucial for studying its performance after SLM forming15,16,17,18,19,20.

As an advanced material characterization method, in situ neutron diffraction technology enables real-time and dynamic observation of the microstructural changes of materials under external loading without damaging the overall structure of the material. This technology provides powerful technical support for deeply revealing the deformation anisotropy mechanism of SLM-formed 316LSS during tensile deformation. Deformation anisotropy refers to the material exhibiting different mechanical properties and deformation behaviors in different directions, which is crucial for understanding and controlling the forming and processing processes of materials.

The physical principles of neutron diffraction technology are highly similar to those of X-ray and electron diffraction technologies, and their core basis is the Bragg Eq. (2)1. In terms of characterizing the residual stress of materials, neutron diffraction exhibits significant advantages compared to traditional methods such as the drilling method, X-ray method, and high-energy synchrotron X-ray method. This has been widely verified and confirmed in relevant studies22,23. It can directly observe critical parameters such as mechanical behavior and grain orientation during material preparation and loading without destroying the material structure. This characteristic makes neutron diffraction irreplaceable in materials science research. With the aid of the most advanced spallation neutron source and analysis technology, researchers can conduct in situ neutron diffraction experiments under complex external environments such as ultra-high/low temperatures and stress24,25. These experiments can not only deeply analyze microstructural changes such as grain rotation and multi-scale stress partitioning of materials, but also reveal key physical processes such as phase transitions and twinning mechanisms in materials.

Tang et al.26 skillfully utilized in situ neutron diffraction technology to deeply explore the tensile deformation mechanism of 316LSS formed by SLM at different temperatures. Their research not only revealed strain-induced twinning transformation as the main deformation mechanism for martensite formation, but also provided valuable insights into understanding the behavior of SS materials under tensile loads. Similarly, Clausen et al.27 also demonstrated superb experimental design in exploring the phase transformation behavior of additive manufactured GP1 SS. They conducted in situ neutron diffraction measurements during heat treatment and uniaxial loading, accurately capturing the significant changes in the austenite-to-martensite phase transformation. This discovery not only further confirmed the powerful application of neutron diffraction technology in materials science, but also revealed the close relationship between material strengthening and the increase in martensite volume fraction, providing an important scientific basis for optimizing the performance of additive manufactured SS.

Moreover, the in situ neutron diffraction experimental technology not only possesses the ability to investigate the crystal texture28,29 and lattice distortion characteristics30,31 of additive manufactured components under load, but it can also accurately measure the dislocation density and dislocation Burgers vector composition during phase transformation32,33. Additionally, through careful observation and analysis of diffraction peak displacement, broadening, and asymmetry, it can further reveal key parameters such as twinning fault probability, dislocation density, and stacking fault energy26,34, providing powerful support for a deeper understanding of the microstructure and properties of materials.

In summary, in situ neutron diffraction technology plays a crucial role in revealing the deformation anisotropy mechanism of SLM-formed 316LSS. Through in-depth study of the microstructural changes and deformation mechanism of SLM-formed 316LSS, its forming process can be further optimized to enhance the material’s mechanical properties and forming quality. Therefore, this article aims to conduct a thorough study on the deformation anisotropy mechanism of SLM-formed 316LSS using in situ neutron diffraction technology, in order to provide beneficial theoretical support and practical guidance for the further development and application of SLM forming technology.

Experimental methods

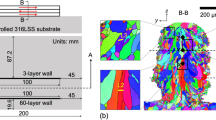

As shown in Fig. 1, the image briefly depicts the process of using 316LSS powder with the powder size distribution of 15–53 μm as the experimental raw material and preparing 316LSS samples through SLM (DiMetal-100 H, Guangzhou laseradd Technology Co.,LTD). As indicated in Table 1, the process parameters for preparing the SLM 316LSS samples include a laser power of 140 W, a scanning speed of 200 mm/s, a layer thickness of 0.03 mm, and a hatch spacing of 0.1 mm.

The SLM-printed 316LSS samples were processed into plate-shaped and rod-shaped tensile samples as shown in Fig. 2 for in situ neutron diffraction tensile testing, the scanning strategy to manufacture the samples is 67-degree rotation. As shown in Fig. 3, this is an image of the SLM 316LSS sample before in situ neutron diffraction tensile testing. Among them, the plate-shaped tensile sample was printed horizontally (XOY), while the rod-shaped tensile sample was printed vertically (XOZ).

As shown in Table 2, the in situ neutron diffraction tensile method for the XOY sample is detailed. Specifically, number 1 represents the state before tension, numbers 2–8 are controlled by force, and numbers 9–25 are controlled by displacement. For each number, in situ neutron diffraction testing is performed with a dwell time of 5–20 min.

As indicated in Table 3, the in situ neutron diffraction tensile method for the XOZ sample is outlined. Specifically, number 1 represents the state before tension, numbers 2–7 are controlled by force, and numbers 8–30 are controlled by displacement. For each number, in situ neutron diffraction test is conducted with a dwell time of 5–20 min.

The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Verios G4 UC) experiments were carried out to observe the fracture surfaces. Electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) analysis was performed using a JEOL JSM-7100 F instrument to investigate the boundaries, grain orientations, and textures within the XOY and XOZ directions of the samples. The acquired data were processed using Aztec Crystal software. Grain boundaries were classified into low-angle grain boundaries (LAGBs), ranging from 2° to 10°, and high-angle grain boundaries (HAGBs), exceeding 10°, based on their misorientation angles. Furthermore, twin boundaries (TBs) with a < 111 > texture tilt angle of 60° were also analyzed.

Results and discussion

Analysis of microstructural and mechanical property

As shown in Fig. 4, the in situ neutron diffraction tensile curves of the XOY and XOZ samples are presented. The maximum force in the force-displacement curve of the XOY sample is close to 12,000 N, with a displacement of approximately 15 mm. In contrast, the maximum force in the force-displacement curve of the XOZ sample is close to 16,500 N, with a displacement of approximately 30 mm. Furthermore, the maximum engineering stress in the engineering stress-strain curve of the XOY sample reaches 700 MPa, with a strain of nearly 45%. However, the maximum engineering stress in the engineering stress-strain curve of the XOZ sample is less than 600 MPa, with a strain of approximately 60%.

This indicates that the sample orientation during SLM formation has a significant impact on the mechanical properties of 316LSS. Relevant literature shows35,36,37 that the sample printing direction during SLM formation has a significant influence on the strength and plasticity of 316LSS. Currently, most literature mainly explains this phenomenon from the perspective of microstructure through EBSD and TEM characterization techniques14,36,38. This paper further explains the differences in mechanical properties of 316LSS formed by SLM in different directions from the perspective of microstructure, specifically the changes in diffraction peaks, through in situ neutron diffraction technology.

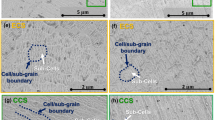

Figure 5 illustrates the fracture morphologies of SLM316LSS samples observed from XOY and XOZ directions. The pores were barely distributed on the fracture surface of the sample, as evident in Fig. 5a,c. Upon closer inspection of the fracture surfaces under high magnification, it became apparent that the primary fracture mode was the classic ductile dimple fracture, characterized by the presence of numerous nano-sized dimples in all cases. This observation was consistent with findings related to wrought stainless steels35 and other SLM316LSSs39,40. Grain refinement increased the stabilization of austenite, which contributed to the excellent combination of strength and ductility of the metastable austenitic steel41. Notably, the nano-sized dimples in the XOY sample were smaller than those in the XOZ sample, suggesting that the printing direction could have a significant impact on the strength and plasticity of 316LSS. However, a significant distinction was the absence of inclusions within the dimples, which differed from traditional casts, forged materials, and other SLM316LSSs42.

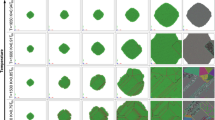

Figure 6a–d depict the inverse pore figure (IPF) maps of the XOY and XOZ direction of SLM316LSS samples before and after fracture, respectively. These maps illustrate a platelet-like grain morphology of the XOY direction sample before fracture, comprising an isotropic structure with a prevalence of < 001>, < 110 > and < 111 > grains. In contrast, the large grains were oriented along the XOZ direction sample before fracture, among which the < 110 > grains were predominant. As a result, the cumulative heat input for each layer might have changed leading to variations in crystallographic orientations between samples in the XOY and the XOZ direction36,43. However, the IPF maps of the XOY and XOZ direction of SLM316LSS samples after fracture were quite different compared with samples before fracture. The twin boundary fraction decreased from ~ 3 to ~ 1% as the direction from XOY to XOZ. The observation of twin boundaries aligned with those in other SLM316LSS specimens20,39. Furthermore, once the SLM316LSS sample was fractured, numerous deformation twins (DTs) were generated during the tensile process (Fig. 6b,d). The appearance of DTs indicated that strength and plasticity of SLM316LSS sample were further improved during the tensile process, which resulted in the improvement of strength and plasticity of SLM316LSS sample during the tensile loading44,45,46. The appearance of DTs aligns with that observed in some SLM316LSSs35,47. Specifically, studies on twinning-induced plasticity (TWIP) in 316LSS materials have shown that TWIP is more facile at lower stacking fault energy and larger grain size45,47,48. As evident from Fig. 6 and earlier works49,50, the successful occurrence of TWIP is demonstrated. Therefore, the deformation mechanism of SLM316LSS samples was primarily attributed to TWIP.

Figure 6e-h show the misorientation distributions of the XOY and XOZ direction of SLM316LSS samples before and after fracture, respectively. The grains within the XOY and XOZ direction of SLM316LSS samples before fracture contained the abundant LAGBs (Fig. 6e,g). It is worth noting that the fraction of HAGBs within the XOZ direction was higher than that in XOY samples after fracture. It is noteworthy that the XOY direction and the XOZ direction displayed a low similarity between the uncorrelated and random curves (Fig. 6e,g), indicating that the microstructures possessed a strong texture. The tolerance used to determine the coincidence site lattice (CSL) boundaries adheres to the Brandon criterion20. Specifically, Σ3 boundaries, characterized by a 60° rotation around a < 111 > direction with a tolerance of 8.66°, also known as twin boundaries, are considered for this purpose. The emergence of twin boundaries aligns with observations in other SLM316LSS specimens20,39. It is widely acknowledged that austenitic stainless steels undergo the formation of twin boundaries during thermomechanical treatments, a phenomenon often harnessed in grain boundary engineering strategies. This is because an increased density of Σ3 twin boundaries can effectively mitigate undesirable interfacial processes such as oxidation, corrosion, grain boundary embrittlement, or fracture20. During SLM processing, the material experiences complex thermomechanical cycles due to thermal stresses and high temperatures resulting from the cooling and reheating cycles during layer building. This can facilitate an in situ thermomechanical treatment, potentially leading to the formation of annealing twins20. Consequently, fracture samples of XOZ, which ensure the largest fraction (~ 55%) of twin boundaries, can maintain a relatively stable ductility (Fig. 4b) compared to the fracture samples of XOY with the ~ 45% fraction of twin boundaries (Fig. 6f, h). Therefore, the TWIP effect in XOY with the maximum strain contributes ~ 45%, while in XOZ contributes ~ 55% TWIP effect.

Analysis of neutron diffraction peak

As shown in Fig. 7, there are significant variations in the diffraction peaks at different orientations during the in situ neutron diffraction tensile deformation process of both the XOY and XOZ samples. For the XOY sample, the diffraction peaks along the loading direction (LD) mainly indicate (111), (200), and (220), while the diffraction peaks perpendicular to the loading direction (ND) mainly indicate (220). For the XOZ sample, the diffraction peaks along the LD and ND mainly indicate (111), (200), and (220). The interplanar spacing of the three main diffraction peaks on the same sample in the LD moves right overall, while the interplanar spacing of the three main diffraction peaks in the ND moves left overall. This is mainly because the LD is the direction of tensile deformation of the sample, while the ND is the direction of compressive deformation (see Fig. 8).

As shown in Fig. 9, the variations of the representative diffraction peak (111) at different orientations during the in situ neutron diffraction tensile deformation process of the XOY and XOZ samples are presented. For the XOY sample, as the deformation increases, the representative diffraction peak (111) along the LD exhibits an overall rightward shift in the interplanar spacing, while the diffraction peak intensity first remains stable and then gradually decreases. However, for the XOY sample along the ND, the representative diffraction peak (111) displays an overall stable change in both interplanar spacing and diffraction peak intensity as the deformation increases.

On the other hand, for the XOZ sample, the representative diffraction peak (111) along the LD exhibits an overall rightward shift in the interplanar spacing as the deformation increases, while the diffraction peak intensity first remains stable and then gradually increases. Conversely, for the XOZ sample along the ND, the representative diffraction peak (111) displays an overall leftward shift in the interplanar spacing, with the diffraction peak intensity gradually decreasing as the deformation intensifies.

The intensity change of the diffraction peak (111) for the XOY-printed sample in the LD is around 10 as the stress increased from 0 to ~ 700 MPa, while the intensity change of the diffraction peak (111) for the XOZ-printed sample in the LD is around 25 as the stress increased from 0 to ~ 570 MPa. For the XOY-printed sample in the ND, the intensity change of the diffraction peak (111) is around 0.5 as the stress increased from 0 to ~ 700 MPa, while for the XOZ-printed sample in the ND, the intensity change of the diffraction peak (111) is around 130 as the stress increased from 0 to ~ 570 MPa (see Fig. 9).

As shown in Fig. 10, the variations of the representative diffraction peak (200) at different orientations during the in situ neutron diffraction tensile deformation process of the XOY and XOZ samples are presented. It can be observed that for the XOY sample, as the deformation increases, the representative diffraction peak (200) along the LD exhibits an overall rightward shift in the interplanar spacing, while the diffraction peak intensity first remains stable and then gradually increases. However, for the XOY sample along the ND, the representative diffraction peak (200) displays an overall stable change in both interplanar spacing and diffraction peak intensity as the deformation intensifies.

For the XOZ sample, the representative diffraction peak (200) along the LD also exhibits an overall rightward shift in the interplanar spacing as the deformation increases. The diffraction peak intensity first remains stable and then gradually increases. However, for the XOZ sample along the ND, the interplanar spacing of the representative diffraction peak (200) first moves left, then right, and finally left again, as the deformation intensifies. Meanwhile, the diffraction peak intensity first decreases and then increases.

The intensity change of the diffraction peak (200) for the XOY-printed sample in the LD is around 6 as the stress increased from 0 to ~ 700 MPa, while the intensity change of the diffraction peak (200) for the XOZ-printed sample in the LD is around 25 as the stress increased from 0 to ~ 570 MPa. For the XOY-printed sample in the ND, the intensity change of the diffraction peak (200) is around 0.5 as the stress increased from 0 to ~ 700 MPa, while for the XOZ-printed sample in the ND, the intensity change of the diffraction peak (200) is around 20 as the stress increased from 0 to ~ 570 MPa (see Fig. 10).

As shown in Fig. 11, the variations of the representative diffraction peak (220) at different orientations during the in situ neutron diffraction tensile deformation process of the XOY and XOZ samples are presented. For the XOY sample, it can be observed that as the deformation increases, the interplanar spacing of the representative diffraction peak (220) along the LD first moves right and then remains overall stable. The diffraction peak intensity first remains stable and then decreases sharply. However, for the XOY sample along the ND, the interplanar spacing moves left as the deformation intensifies, while the diffraction peak intensity first remains stable and then gradually decreases.

For the XOZ sample, the interplanar spacing of the representative diffraction peak (220) along the LD first moves right and then remains overall stable as the deformation increases. The diffraction peak intensity first remains stable and then gradually decreases. However, for the XOZ sample along the ND, the interplanar spacing first moves right, then left, as the deformation intensifies. Meanwhile, the diffraction peak intensity first remains stable, then decreases sharply, and finally exhibits a stable change.

The intensity change of the diffraction peak (220) for the XOY-printed sample in the LD is around 18 as the stress increased from 0 to ~ 700 MPa, while the intensity change of the diffraction peak (220) for the XOZ-printed sample in the LD is around 100 as the stress increased from 0 to ~ 570 MPa. For the XOY-printed sample in the ND, the intensity change of the diffraction peak (220) is around 40 as the stress increased from 0 to ~ 700 MPa, while for the XOZ-printed sample in the ND, the intensity change of the diffraction peak (220) is around 20 as the stress increased from 0 to ~ 570 MPa (see Fig. 11). The following relationship can be obtained by fitting the corresponding diffraction peak intensity with the tensile performance data of XOY and XOZ:

In summary, the relationship between diffraction peak intensity and the tensile performance data of XOY and XOZ follows a quadratic equation with one unknown, that is:

where \(\:y\) represents the corresponding diffraction peak intensity, \(\:x\) refers to the corresponding true strain of XOY and XOZ, and a is a quadratic coefficient, b is a linear coefficient, c is a constant term, respectively.

Using in situ neutron diffraction techniques, it was found that due to the unique nature of the SLM forming method, there are significant differences in the microstructure of 316LSS samples printed in XOY and XOZ orientations, specifically manifested in the variations of the three main diffraction peaks (111), (200), and (220) in terms of interplanar spacing and diffraction peak intensity (see Figs. 7, 9, 10 and 11). For the same sample, the three main diffraction peaks (111), (200), and (220) exhibit significant variations in interplanar spacing and diffraction peak intensity when observed along the LD and NDs. Furthermore, there are considerable variations in the interplanar spacing and diffraction peak intensity of the three main diffraction peaks (111), (200), and (220) when comparing XOY-printed and XOZ-printed samples along the same orientation. The reason behind the change in the diffraction peak characteristics is due to change in texture, grain rotation and twinning (see Fig. 6).

Analysis of lattice constants and phase transformation behavior

When comparing the full-spectrum neutron diffraction peaks of sample number 1 before stretching with the results of diffraction peaks fitted by FullProf software, the overall fitting error is relatively small (see Fig. 12). The lattice constants of the samples in Fig. 12a–d are ~ 3.59571 Å, ~ 3.60025 Å, ~ 3.59518 Å, and ~ 3.60026 Å, respectively, showing significant differences in lattice constants among XOZ-samples in different orientations.

Comparing the representative full-spectrum neutron diffraction peaks of the XOY-sample during the in situ neutron diffraction tensile deformation process in the LD with the diffraction peak results fitted by FullProf software, the fitting error increases during the plastic deformation process (see Fig. 13). The lattice constants of the samples in Fig. 13a–e are ~ 3.59571 Å, ~ 3.60282 Å, ~ 3.60394 Å, ~ 3.60552 Å, and ~ 3.60635 Å, respectively, indicating a gradual increase in the lattice constant of the XOY-sample in the LD as the stress increased from 0 to ~ 700 MPa (with lattice parameters increasing ~ 0.296%).

When comparing the representative full-spectrum neutron diffraction peaks of the XOY-sample during the in situ neutron diffraction tensile deformation process in the ND with the diffraction peak results fitted by FullProf software, the overall fitting error is relatively small (see Fig. 14). The lattice constants of the samples in Fig. 14a–e are ~ 3.60025 Å, ~ 3.59948 Å, ~ 3.59917 Å, ~ 3.59658 Å, and ~ 3.59535 Å, respectively, indicating a gradual decrease in the lattice constant of the XOY-sample in the ND as the stress increased from 0 to ~ 700 MPa (with lattice parameters decreasing ~ 0.136%).

When comparing the representative full-spectrum neutron diffraction peaks of the XOZ-sample during the in situ neutron diffraction tensile deformation process in the LD with the diffraction peak results fitted by FullProf software, the fitting error increases during the plastic deformation process (see Fig. 15). The lattice constants of the samples in Fig. 15a–f are ~ 3.59518 Å, ~ 3.60375 Å, ~ 3.60391 Å, ~ 3.60720 Å, ~ 3.60998 Å, and ~ 3.61269 Å, respectively, indicating a gradual increase in the lattice constant of the XOZ-sample in the LD as the stress increased from 0 to ~ 570 MPa (with lattice parameters increasing ~ 0.487%).

When comparing the representative full-spectrum neutron diffraction peaks of the XOZ-sample during the in situ neutron diffraction tensile deformation process in the ND with the diffraction peak results fitted by FullProf software, the overall fitting error is relatively small, but the fitting error is larger during the intermediate stage of plastic deformation (see Fig. 16). The lattice constants of the samples in Fig. 16a–f are ~ 3.60026 Å, ~ 3.59863 Å, ~ 3.59853 Å, ~ 3.59746 Å, ~ 3.59655 Å, and ~ 3.59535 Å, respectively, indicating a gradual decrease in the lattice constant of the XOZ-sample in the ND as the stress increased from 0 to ~ 570 MPa (with lattice parameters decreasing ~ 0.136%).

During the tensile process, the 316LSS sample formed by SLM exhibits significant lattice distortion, which is mainly attributed to the special microstructure and grain orientation formed during the laser melting process. As the tensile strain increases, the degree of lattice distortion gradually intensifies, and significant anisotropy is observed in different directions. As a result, the large strain of XOZ means the large increasing lattice parameters of additive manufactured 316LSS based on in situ neutron diffraction during tensile tests at room temperature, while the small strain of XOY means the small increasing lattice parameters.

During the tensile process, no significant phase transformation behavior was observed in the sample. This indicates that the austenitic structure of 316LSS maintains good stability under tensile stress. However, due to factors such as lattice distortion and stress concentration, the sample may experience local plastic deformation or crack initiation in the later stages of the tensile process.

In situ neutron diffraction has certain potential in the study of deformation anisotropy mechanism of 316LSS in AM, but it also faces many limitations and restrictions. To overcome these limitations, it is necessary to further improve the intensity and flux of the neutron source, optimize sample preparation and processing methods, develop more advanced data analysis algorithms and models, and seek to combine with other experimental technologies. In addition, it is also necessary to strengthen the connection between experimental conditions and the AM site, so as to better understand and control the deformation anisotropy mechanism in the AM process.

Conclusions

-

(1)

Using the SLM forming method, 316LSS samples with different mechanical properties can be prepared. The tensile strength of the XOY-printed samples reaches 700 MPa, while the tensile strength of the XOZ-printed samples is less than 600 MPa, due to the largest fraction of nano-sized dimples. However, the plasticity of the XOZ-printed samples is better than that of the XOY-printed samples, due to the largest fraction of twin boundaries.

-

(2)

Based on the research using in situ neutron diffraction technology, it was found that the diffraction peaks of the XOY and XOZ oriented SLM-formed 316LSS samples underwent significant changes during the tensile deformation process. Specifically, the three major diffraction peaks (111), (200), and (220) along the axial and transverse directions exhibited substantial variations, which were primarily manifested in the changes in the interplanar spacing and diffraction peak intensity.

-

(3)

The lattice constant of the XOY-printed samples in the tensile loading direction increased from ~ 3.59571 Å to ~ 3.60635 Å as the stress increased from 0 to ~ 700 MPa, while the lattice constant of the XOZ-printed samples in the tensile loading direction increased from ~ 3.59518 Å to ~ 3.61269 Å as the stress increased from 0 to ~ 570 MPa. However, the lattice constant of the XOY-printed samples in the direction perpendicular to the tensile loading decreased from ~ 3.60025 Å to ~ 3.59535 Å as the stress increased from 0 to ~ 700 MPa, and the lattice constant of the XOZ-printed samples in the same perpendicular direction decreased from ~ 3.60026 Å to ~ 3.59535 Å as the stress increased from 0 to ~ 570 MPa. Regardless of the differences in neutron diffraction peaks, the lattice constants obtained from the direction perpendicular to the axial orientation during the tensile test were almost identical.

-

(4)

The 316LSS formed by SLM exhibits significant lattice distortion during tensile testing, and exhibits anisotropy in different directions. The deformation anisotropy mechanism of the additively manufactured 316LSS based on in situ neutron diffraction is attributed to the differences of diffraction peaks and lattice constants in the axial orientation during tensile testing at room temperature. Meanwhile, no phase transformation occurred in the sample during the tensile process, but attention should be paid to the risk of local plastic deformation or crack initiation.

IPF maps and misorientation distribution of SLM316LSS samples before and after fracture at the respective direction: (a,b,e,f) XOY and (c,d,g,h) XOZ. “Correlated” signifies the misorientation calculated based on neighboring points. ‘‘Uncorrelated’’ implies the misorientation calculated according to random points in the scan, and ‘‘Random’’ represents the theoretically calculated using random misorientation distribution of a purely random texture, respectively.

The representative in situ neutron diffraction patterns of XOY and XOZ samples collected during deforming at room temperature with their respective directions: (a) LD of XOY specimen, (b) ND of XOY specimen, (c) LD of XOZ specimen, and (d) ND of XOZ specimen. The diffraction peaks of (111), (200), and (220) were marked.

The experimental setup for in situ neutron diffraction involves precise positioning of the tensile loading apparatus, with the loading direction oriented at a 45° angle relative to the incoming neutron beam. The arrangement further incorporates two detectors, each strategically positioned to capture data. Specifically, each detector measures the lattice spacings (or scattering vector, Q) in two distinct directions: parallel to the loading direction (LD) and perpendicular to it, referred to as the normal direction (ND), within the defined scattering volume. This ensures a comprehensive analysis of the lattice planes’ behavior under tensile loading.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kürnsteiner, P. et al. High-strength Damascus steel by additive manufacturing. Nature 582, 515–519 (2020).

Gu, D. et al. Material-structure-performance integrated laser-metal additive manufacturing. Science 372, eabg1487 (2021).

Ren, J. et al. Strong yet ductile nanolamellar high-entropy alloys by additive manufacturing. Nature 608, 62–68 (2022).

Gao, S. et al. Additive manufacturing of alloys with programmable microstructure and properties. Nat. Commun. 14, 6752 (2023).

Yu, A. H. et al. Development and characterizations of graded porous titanium scaffolds via selective laser melting for orthopedics applications. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China. 33, 1755–1767 (2023).

Ahmadi, M. et al. Review of selective laser melting of magnesium alloys: advantages, microstructure and mechanical characterizations, defects, challenges, and applications. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 19, 1537–1562 (2022).

Yang, P. et al. Influence of surface micro-oxidation on the formability of pure copper powders by selective laser melting. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 28, 4350–4357 (2024).

Yan, X. et al. Study of the microstructure and mechanical performance of C-X stainless steel processed by selective laser melting (SLM). Mater. Sci. Eng. A 781, 139227 (2020).

Dong, D. et al. Selective laser melting (SLM) of CX stainless steel: theoretical calculation, process optimization and strengthening mechanism. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 73, 151–164 (2021).

Sun, Z. J. et al. Selective laser melting of stainless steel 316L with low porosity and high build rates. Mater. Des. 104, 197–204 (2016).

Bartolomeu, F. et al. 316L stainless steel mechanical and tribological behavior—A comparison between selective laser melting, hot pressing and conventional casting. Addit. Manuf. 16, 81–89 (2017).

Shin, W. S. et al. Heat treatment effect on the microstructure, mechanical properties, and wear behaviors of stainless steel 316L prepared via selective laser melting. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 806, 140805 (2021).

Afkhami, S. et al. Effects of manufacturing parameters and mechanical post-processing on stainless steel 316L processed by laser powder bed fusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 802, 140660 (2021).

Zou, Z. et al. Corrosion behavior of different building planes of selective laser melting 316L stainless steel in 0.1 M HCl solution. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 28, 4738–4753 (2024).

Beard, W. et al. The influence of surface finish and build orientation on the low cycle fatigue behaviour of laser powder bed fused stainless steel 316L. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 864, 144593 (2023).

Chen, Y. F. et al. Experimental characterization and strengthening mechanism of process-structure-property of selective laser melted 316 L. Mater. Charact. 198, 112753 (2023).

De Sonis, E. et al. Microstructure–Toughness relationships in 316L stainless steel produced by laser powder bed fusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 877, 145179 (2023).

Delrio, F. W. et al. Porosity, roughness, and passive film morphology influence the corrosion behavior of 316L stainless steel manufactured by laser powder bed fusion. J. Manuf. Process. 102, 654–662 (2023).

Liu, S. J. et al. Effect of additive manufacturing of SUS316L using selective laser melting. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 24, 9824–9833 (2023).

Monier, L. et al. On the origin of grain refinement and twin boundaries in as-fabricated austenitic stainless steels produced by laser powder bed fusion. Addit. Manuf. 61, 103351 (2023).

Deng, H. et al. Application of synchrotron radiation and neutron diffraction technologies in additive manufacturing. Chin. J. Lasers 49, 1902002-1902002-17 (2022).

Plotkowski, A. et al. Operando neutron diffraction reveals mechanisms for controlled strain evolution in 3D printing. Nat. Commun. 14, 4950 (2023).

Beltrami, M. et al. Microstructure and residual stress evolution during cyclic elastoplastic deformation of AISI316L fabricated via laser powder bed fusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 898, 146416 (2024).

Rietveld, H. M. The Rietveld method. Phys. Scr. 89, 098002 (2014).

Bai, B. et al. Development and testing of 4 K cryostat for China spallation neutron source. Cryogenics Supercond.. 51, 1–6 (2023).

Tang, L. et al. Mechanical performance and deformation mechanisms at cryogenic temperatures of 316L stainless steel processed by laser powder bed fusion: In situ neutron diffraction. Scr. Mater. 218, 114806 (2022).

Clausen, B. et al. Deformation behavior of additively manufactured GP1 stainless steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 696, 331–340 (2017).

Uhlmann, E. et al. A laser powder bed fusion system for in situ x-ray diffraction with high-energy synchrotron radiation. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 91, 075104 (2020).

Krohmer, E. et al. Revealing dynamic processes in laser powder bed fusion with in situ X-ray diffraction at PETRA III. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 93, 065104 (2022).

Calta, N. P. et al. An instrument for in situ time-resolved X-ray imaging and diffraction of laser powder bed fusion additive manufacturing processes. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 89, 055101 (2018).

Thampy, V. et al. Subsurface cooling rates and microstructural response during laser based metal additive manufacturing. Sci. Rep. 10, 1981 (2020).

Miao, Y. et al. In situ synchrotron tensile investigations on ultrasonic additive manufactured (UAM) zirconium. J. Nucl. Mater. 568, 153843 (2022).

Prasad, K. et al. In situ synchrotron diffraction study of a crack-free additively manufactured Ni base superalloy. Scr. Mater. 200, 113896 (2021).

Zhang, X. X. et al. Strain hardening behavior of additively manufactured and annealed AlSi3.5Mg2.5 alloy. J. Alloy Compd. 898, 162890 (2022).

Liu, W. et al. Tailoring the microstructural and mechanical properties of 316L stainless steel manufactured by laser powder bed fusion. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 25, 7389–7405 (2023).

Dixit, S. et al., Investigating build orientation-induced mechanical anisotropy in additive manufacturing 316L stainless steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 880, 145308 (2023).

Jinlong, L. et al. The effect of build orientation on tensile properties and corrosion resistance of 316L stainless steel fabricated by laser powder bed fusion. J. Manuf. Process. 106, 363–369 (2023).

Chen, Z. et al. A new phenomenon in a selective laser melted 316L stainless steel with a wider and higher laser energy density. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 30, 1735–1750 (2024).

Li, W. et al., Plastic deformation behavior and strengthening mechanism of SLM 316L reinforced by micro-TiC particles. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 884, 145557 (2023).

Jandaghi, M. R. et al. Comparative assessment of gas and water atomized powders for additive manufacturing of 316 L stainless steel: Microstructure, mechanical properties, and corrosion resistance. Mater. Charact. 204, 113204 (2023).

Mao, W. et al. In situ neutron diffraction revealing the achievement of excellent combination of strength and ductility in metastable austenitic steel by grain refinement. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 176, 69–82 (2024).

Deng, P. et al., On the thermal coarsening and transformation of nanoscale oxide inclusions in 316L stainless steel manufactured by laser powder bed fusion and its influence on impact toughness. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 835, 142690 (2022).

Wang, X. et al., Crystallographic-orientation-dependent tensile behaviours of stainless steel 316L fabricated by laser powder bed fusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 766, 138395 (2019).

Wang, Y. M. et al. Additively manufactured hierarchical stainless steels with high strength and ductility. Nat. Mater. 17, 63–71 (2017).

Pham, M. S. et al. Twinning induced plasticity in austenitic stainless steel 316L made by additive manufacturing. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 704, 102–111 (2017).

Voisin, T. et al., New insights on cellular structures strengthening mechanisms and thermal stability of an austenitic stainless steel fabricated by laser powder-bed-fusion. Acta Mater. 203, 116476 (2021).

He, F. et al. Deformation faulting and dislocation-cell refinement in a selective laser melted 316L stainless steel. Int. J. Plast. 156, 103346 (2022).

Yin, Y. J. et al. Mechanism of high yield strength and yield ratio of 316 L stainless steel by additive manufacturing. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 744, 773–777 (2019).

Mirzababaei, S. et al., Microstructure-property relationship in binder jet produced and vacuum sintered 316 L. Addit. Manuf. 53, 102720 (2022).

Kumar, P. et al. Fatigue strength of additively manufactured 316L austenitic stainless steel. Acta Mater. 199, 225–239 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Certificate Number: 2023TQ0264). This work was also supported by the NSFC Original Exploration Project (Grant No. 12150001) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 11832019, 52104394, and 12405345), and the Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Extreme Conditions (2023B1212010002). The authors also appreciate the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Nos. 2021B1515120028, 2022B1515120066, and 2022A1515110344). SEM data were obtained using equipment maintained by Dongguan University of Technology Analytical and Testing Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.C.: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, validation, visualization, data curation, writing original and revised draft. Z.J., F.W.: Methodology, investigation, validation. D.Z., X.Z., C.W.: Investigation, formal analysis, resources, visualization, validation, neutron diffraction analysis and feedback. J.H., M.T.: Investigation, validation. B.C., H.J.K., B.W.: Supervision, reviewing the original and revised draft. R.L., B.W., G.L.: Funding acquisition, resources, supervision, feedback, reviewing the original and revised draft.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Z., Jiang, Z., Wang, F. et al. Deformation behavior of additive manufactured 316 L stainless steel using in situ neutron diffraction. Sci Rep 15, 3104 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87329-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87329-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Plasticity and ductile fracture of conventionally manufactured AISI 316L compared to one produced by selective laser melting with and without machining

The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology (2025)