Abstract

In addition to the known link between cholecystectomy and depression, the risk of developing short-term and long-term depression after surgery and whether such mental health issues leads to suicide were not known. Therefore, this study aimed to address these questions. Using data from the National Health Insurance Service of Korea (2002–2019), we conducted a retrospective cohort study including 6,688 cholecystectomy patients matched with 66,880 individuals without a history of cholecystectomy for suicide analysis and 6,694 cholecystectomy patients matched with 66,940 individuals for depression analysis. The non-cholecystectomy group was matched at a 1:10 ratio for sex and age. The incidence of depression and suicide were followed from the day of cholecystectomy to December 31, 2019. Adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression. Short-term depression risk within three years of cholecystectomy was significantly elevated (aHR 1.38, 95% CI 1.19–1.59), while the long-term depression risk beyond three years was not significantly greater (aHR 1.09, 95% CI 0.98–1.22). Cholecystectomy was not associated with an increased risk of suicide in any period. These findings highlight the importance of monitoring and providing postoperative mental health support for patients at risk of short-term depression after cholecystectomy. However, no association was observed with long-term depression or suicide risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cholecystectomy is one of the most common types of organ removal surgery, and most cholecystectomies are performed for people with symptomatic gallstone disease or sludge, gallbladder polyps, and severe complications of gallbladder disease such as acute and chronic cholecystitis, and acute cholangitis1,2. It can also be performed in conjunction with liver transplantation and hepatectomy3. According to medical statistics from the Korea Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service, the number of cholecystectomies performed in South Korea increased from 47,601 in 2010 to 83,479 in 2021.

Patients who undergo cholecystectomy often experience postcholecystectomy syndrome (PCS), characterized by symptoms such as flatulent dyspepsia, dull abdominal pain, and diarrhea4,5,6,7. PCS can be linked to psychological disorders, including depression and anxiety5,8,9,10,11. A recent study of South Koreans that followed patients for an average of 3.67 years revealed that patients in the cholecystectomy group had a greater risk of developing major depressive disorder than the group that did not have cholecystectomy8. A study of a Taiwanese population with a 2-year follow-up also found that patients who had undergone cholecystectomy had an increased risk of developing a depressive disorder compared with those who had not. In particular, the risk of depressive disorders was increased in female patients who underwent cholecystectomy9. Patients with suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction also reported heightened levels of anxiety and depression postcholecystectomy, correlating with their pain and depression12. However, no studies have confirmed the long-term effects of cholecystectomy on depression risk.

The number of cholecystectomies is increasing in Korea, and a multicenter cohort study revealed that 0.9% of patients reported significant levels of anxiety or depression9. However, the specific risk of suicide following cholecystectomy remains poorly understood, despite South Korea’s high suicide rate. A report by Statistics Korea indicated that in 2021, 13,352 individuals died of suicide13. A previous study in Korean population has linked cholecystectomy to depression, attributed in part to changes in the gut microbiome and metabolic consequences14,15,16,17. Given the known association between postoperative depression and suicide, further investigation into cholecystectomy’s potential role in suicide risk is warranted to further explore the possible etiologies, including the gut microbiome and PCS18,19. However, to our knowledge, the association between cholecystectomy and suicide has not been studied. Utilizing the National Health Insurance Service-National Health Screening (NHIS-HEALS) cohort, this study aims to explore both short-term and long-term risks of depression and suicide following cholecystectomy.

Methods

Data source

This study was conducted using the NHIS-HEALS cohort database of South Korea from 2002 to 201920. This database, maintained by the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS), draws from health screening programs accessible to most insured Koreans. Since 1995, the NHIS has conducted standardized general health screenings biennially for Korean adults aged 40 and above. Data encompass key health variables including blood pressure, body mass index, cholesterol levels, smoking and drinking habits, as well as weekly exercise frequency.

Study population and design

Figure 1 provides the process of selecting the study population. Utilizing NHIS-HEALS data from 2002 to 2019, 15,437 patients who underwent cholecystectomy between 2004 and 2019 were included. Exclusions comprised 3,819 patients without health screening data, 14 with a history of liver transplantation, 1,032 with liver cancer or choledochocholecystic tumors, and 2,542 with psychiatric disorders diagnosed pre-cholecystectomy. The psychiatric disorders exclusion group was defined as individuals diagnosed with disorders classified under ICD-10 codes F20–F29, F30–F33, F340–F341, F00–F09, and F40–F48. Ultimately, 6,688 patients were included in the cholecystectomy group for depression outcomes, and 6,694 for suicide outcomes. The individuals in the non-cholecystectomy group were matched for age and sex in a 1:10 ratio.

Key variables

We extracted exposure variables using the procedure registry code Q7380 for cholecystectomy. Depression and suicide were defined using codes from the 10th edition of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases (ICD-10)21. Suicide was separately collected by the National Statistical Office of Korea as demographic and sociological statistics, and death could be analyzed by combining it with the death date of the health examination cohort database used in this study. In particular, suicide is defined by using information released as a middle classification unit and is not disclosed as a sub-classification system at the national level because it is sensitive person information. Suicide mortality was designated by codes X60-X84, while depression was diagnosed as F32-F33. Among the ICD-10 codes that correspond to the operational definition of depression, F33 is the definition of recurrence of depression, but due to the limitations of the database we can access, it is impossible to check the history of depression diagnosis before 2002. Therefore, F33 was included in the definition of depression diagnosis in consideration of the fact that a person with a history of depression diagnosis before 2002 could be defined as a recurrence of depression because he was diagnosed with depression during the follow-up period. Patients with an F32-F33 diagnosis, both outpatient and inpatient records, and at least one antidepressant prescription were considered to have depressive disorder. Follow-up for depression and suicide diagnoses was observed until December 31st, 2019. Variables including sex, age, household income, smoking, exercise frequency, alcohol consumption, blood pressure, fasting serum glucose, body mass index, total cholesterol, and Charlson Comorbidity Index were considered. In the evaluation of the patient’s income, the patient’s insurance grade was divided into 20 units and grouped into 4 groups based on the data, and then the income was replaced with the corresponding data grouped. The alcohol consumption refers to the frequency of drinking within 1 week. As a limitation in the database of health screening cohort studies used in this study, drinking consumption behavior was replaced by the date of the number of drinking consumption per week. The number of medium-intensity exercises was the sum of strenuous exercise sessions lasting more than 20 min and moderate exercise sessions lasting more than 30 min within one week. Short-term depression risk was defined as diagnosis within 3 years postcholecystectomy, while long-term risk was defined as diagnosis beyond 3 years postcholecystectomy.

Statistical analysis

The characteristics of the participants in this study were stratified by cholecystectomy. Continuous variables were presented as the means and standard deviations, while categorical and dichotomous variables are expressed as percentages and frequencies. We compared the clinical characteristics between cholecystectomy and non-cholecystectomy groups using the chi-squared test and the independent sample t-test. The Cox proportional hazards model was utilized to estimate the association between cholecystectomy and depression, as well as between cholecystectomy and suicide, producing adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) and 95% confidence interval (CI)22. The hazard ratio was calculated after adjustments included age, sex, diastolic blood pressure, systolic blood pressure, body mass index, household income, smoking, drinking frequency, physical activity, fasting serum glucose, total cholesterol, and Charlson Comorbidity Index23. P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. SAS Enterprise Guide version 8.3 conducted all analyses.

Ethical approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital (IRB number: E-2204-038-1314) and adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent updates. The requirement for informed consent was waived as the NHIS database used for analysis was anonymized according to strict compliance with confidentiality standards prior to analysis.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the population in the study cohort are shown in Table 1. The study cohort comprised 6,688 individuals who underwent cholecystectomy and 66,880 age- and sex-matched controls. Both groups had an average age of 62 years (SD: 9.4). 4,041 males underwent cholecystectomy, alongside 40,410 male controls. For females, 2,647 had cholecystectomy, compared to 26,470 controls. As with several previous studies related to cholecystectomy in Korea, patients with cholelithiasis, one of the subjects of cholecystectomy, seem to dominate in men in Korea. The exposed and control groups were matched at a 1:10 ratio. Median body mass index was 24.5 for cholecystectomy patients and 23.9 for controls. Cholecystectomy patients exhibited higher income, lower alcohol consumption, physical activity, and total cholesterol, along with higher fasting serum glucose, body mass index, and diastolic blood pressure, as well as more comorbidities (p < 0.05 for all).

Associations of cholecystectomy with depression and suicide outcomes

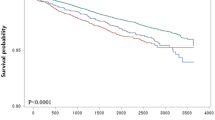

Table 2 provides the results of the multivariable Cox proportional hazards analysis, indicating the association between cholecystectomy and depression risk after covariate adjustments. This analysis was used to determine the association between cholecystectomy and the risk of developing depression after adjusting for covariates. As shown in the graphical summary (see Fig. 2), patients who underwent cholecystectomy showed an increased risk of depression compared to those who didn’t (aHR 1.19 [95% CI, 1.19–1.30]), particularly within 3 years after cholecystectomy (aHR 1.38 [95% CI, 1.19–1.59]). However, no significant long-term risk was observed beyond 3 years postcholecystectomy (aHR 1.09 [95% CI, 0.98–1.22]). Table 3 shows that 229 suicides occurred during the total follow-up period, 22 cases of cholecystectomy and 7 cases of non-operative groups, but there is no association between cholecystectomy and suicide risk (aHR 1.08 [95% CI, 0.69–1.68]). Similarly, there was no significant association observed in the short-term (aHR 0.88 [95% CI, 0.35–2.23]) or long-term (aHR 1.09 [95% CI, 0.68–1.89]) after cholecystectomy.

Subgroup analyses were conducted for age group, sex, comorbidity, and inclusion year to assess study heterogeneity. Among patients with a Charlson Comorbidity Index of less than 2, no significant association was found between cholecystectomy and depression risk, both short-term and long-term. However, those with an index of 2 or more had an elevated risk of short-term depression within 3 years following cholecystectomy (aHR 1.48 [95% CI, 1.24–1.77]) (see Table 4). In the analysis by sex in Table 5, both males and females showed increased depression risk within 3 years of cholecystectomy. Notably, females had a higher risk compared to males (aHR 1.39 [95% CI, 1.13–1.70]). Patients under 65 years old exhibited the highest increase in short-term depression risk after cholecystectomy (aHR 1.48 [95% CI, 1.22–1.80]) (see Supplementary Table S1 online). The association between cholecystectomy and the risk of depression was analyzed based on the year of inclusion. Patients included between 2004 and 2007 (aHR 1.46 [95% CI, 1.05–2.04]) and 2008–2012 (aHR 1.13 [95% CI, 0.89–1.43]) showed a significantly increased risk of depression (see Supplementary Table S2). In contrast, no significant association was found between cholecystectomy and suicide risk when analyzed by sex, age, or comorbidity, both short-term and long-term (see Supplementary Table S3, S4, and S5 online).

Discussion

Our retrospective cohort study is the first to present the results of further studies on whether the previously known association with mental health, such as depression after cholecystectomy, can even affect long-term mental health and suicide. The focus of this study was to examine the associations between cholecystectomy and depression and between cholecystectomy and suicide in Koreans who underwent cholecystectomy. we observed an increased risk of short-term depression postcholecystectomy, particularly among those with more comorbidities and individuals under 65 years old. Additionally, both males and females had a greater risk of short-term depression, and the extent of risk elevation was greater for women. However, we found no association between cholecystectomy and long-term depression risk, nor was there a significant association with suicide risk.

Previous studies have indicated a higher risk of major depressive disorder among those with a history of cholecystectomy, particularly in patients aged 40–49 years8. Another study found a greater risk of depressive disorder postcholecystectomy, especially among women9. To better understand the mechanisms that explain the association between cholecystectomy and depression and between cholecystectomy and suicide, this study analyzed the risk of depression and suicide after cholecystectomy, dividing patients into short-term and long-term categories. The findings revealed an increased short-term risk of depression but no long-term association. Additionally, no significant association was found between cholecystectomy and suicide. These results can be analyzed from three viewpoints.

First, in line with previous studies reporting that depression occurred in 1.8–3.5% of patients who underwent cholecystectomy8,9,24,25,26, our study showed a 1.3% incidence rate of depression in patients undergoing cholecystectomy. Patients with cholelithiasis have a higher incidence of depression than does the population in general, the relationship between mental health issues and gallbladder disease appears to be bidirectional27,28. There may be a risk of developing depression due to symptomatic cholelithiasis in the cholecystectomy group included in our study. Therefore, to minimize this potential bias, we adjusted for potential confounding factors such as sex, age, total cholesterol, body mass index, smoking status, household income, alcohol consumption, physical activity, diastolic blood pressure, fasting serum glucose, systolic blood pressure and Charlson Comorbidity Index. We also excluded people who were diagnosed with depression before their cholecystectomy. A total of 913 people with a history of depression were excluded from the study. We used the same exclusion criteria to establish an age- and sex-matched non-cholecystectomy group of people who underwent cholecystectomy. This enabled us to eliminate the possibility that the prevalence of depression in the cholecystectomy group may have influenced the risk of depression after cholecystectomy.

Second, the increased short-term risk of depression following cholecystectomy may be attributed to alterations in the gut microbiome, influenced by changes in bile acid flow29,30,31,32. These alterations can disrupt physiological balance, affecting immunity and causing fatigue14,15. Previous studies have linked gut microbiome changes to depression16,17,33,34, impacting neurotransmitter systems and leading to anxiety and stressful behaviors17, possibly exacerbated by an increase in harmful bacteria16,33,35,36. However, the gut microbiome may adapt in the long-term after cholecystectomy, so the medium- to long-term effects of changes in the gut microbiome remain controversial. Therefore, additional studies are needed to further analyze the relationship between the gut microbiome and depression duration.

Finally, PCS is a heterogeneous group of symptoms consisting of persistent postoperative abdominal pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, and jaundice, and has been posited as a mechanism behind the increased risk of short-term depression following cholecystectomy37,38,39,40. The incidence of PCS varies from as little as 2 days to as long as 25 years, but late PCS is defined as PCS occurring several months after surgery1,39,40,41. Although there are various causes of PCS, bowel movement disorders, notably irritable bowel syndrome or sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, are proposed as major causes39,42. PCS is linked to depression and anxiety10,38,43, correlating with decreased quality of life42,44. Patients with symptoms of gallstone disease achieved higher long-term quality of life after cholecystectomy45. Therefore, the increased risk of short-term depression after cholecystectomy in our study may be explained by the early PCS experienced by cholecystectomy patients. There was no association between cholecystectomy and the risk of long-term depression, probably because symptoms, such as pain after cholecystectomy, appear early after surgery46 and gradually improve over time after cholecystectomy, as does quality of life24. Previous studies have reported that more than 90% of patients experience an improvement in symptoms after cholecystectomy 1 year after cholecystectomy47. Further studies on the mechanism of PCS occurrence could be beneficial for understanding the health outcomes of patients who have undergone cholecystectomy. Although PCS may explain the increased risk of short-term depression after cholecystectomy, the underlying mechanism is likely complex, as changes in the gut microbiome may also play a role.

The mechanism behind the highest increase in short-term depression risk in women in the subgroup analysis can be explained as follows. Previous studies have reported that PCS is common in women with a high incidence of gallstones37. Additionally, a negative association between women and health-related quality of life after cholecystectomy has been noted48. Furthermore, our findings indicate a greater risk of short-term depression postcholecystectomy in patients with a higher Charlson Comorbidity Index, which aligns with previous studies showing a higher incidence of major depressive disorder in patients with hypertension, diabetes, or dyslipidemia8. Patients with hypertension, diabetes, or dyslipidemia, in general, were found to have a higher incidence of depression49,50. Changes in bile acids due to cholecystectomy may influence lipid metabolism, potentially contributing to the development of metabolic diseases, which could explain our results15,31.

This study has several strengths. First, the study analyzed data from a large population cohort. Data from the entire period established from 2002 to 2019 were used. Second, our study is the first to analyze the association between cholecystectomy and suicide risk in Korean adults. The limitation of this study is that it is not a total inspection database because it is a retrospective cohort study. Since the study was not conducted for the entire population, there are limitations in applying the study results to the entire population. Additionally, as the study population is limited to Korea, the findings may not be broadly applicable to a global context. Second, patients who underwent cholecystectomy may have underlying diseases such as gallbladder cancer, bile duct cancer, or liver cancer, and their gallbladder may have been removed during liver transplantation; Therefore, they could be affected by any of these conditions or surgeries, potentially influencing their outcomes. Third, cholecystectomy, depression, and suicide were identified using ICD-10 codes, which have the potential for misclassification because they may not be accurately recorded. Fourth, inaccuracies in suicide coding within claims databases may have occurred51. Fifth, one limitation of this study is the absence of data on complications following cholecystectomy, specifically PCS, which is often considered a potential mechanism linking cholecystectomy to depression. While we attempted to identify PCS using the ICD-10 code K91.5 in the cholecystectomy group, no cases were recorded in our dataset. This limitation prevents us from analyzing the potential correlation between PCS and outcome parameters, including depression. In addition, there is a limitation that it is not possible to confirm in the database used in our study, but PCS may at least partially include patients with genetic diseases such as ABCB4/LPAC syndrome. Note that these patients may be included, it would be good if a follow-up study on PCS considered genetic diseases. Additionally, this study suggests an association only, and further research is needed to explain the causal relationship between cholecystectomy and depression and suicide.

In conclusion, the results of this study suggest that cholecystectomy is associated with an increased risk of short-term depression within 3 years postoperatively, whereas its association with long-term depression and suicide risk appears to be negligible. These findings emphasize the importance of monitoring and supporting patients’ mental health during the immediate postoperative period. Clinicians should carefully consider the risk of depression in patients undergoing cholecystectomy. Additionally, further research is needed to explore the underlying mechanisms and to validate these findings in diverse populations.

Data availability

The dataset generated in the NHIS repository (https://nhiss.nhis.or.kr/). Data are available from permitted researchers and are not publicly available.

References

Gutt, C., Schlafer, S. & Lammert, F. The treatment of Gallstone Disease. Dtsch. Arztebl Int. 117, 148–158. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2020.0148 (2020).

Shabanzadeh, D. M. The symptomatic outcomes of cholecystectomy for gallstones. J. Clin. Med. 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12051897 (2023).

Akbulut, S. et al. Histopathological evaluation of gallbladder specimens obtained from living liver donors. Transpl. Proc. 55, 1267–1272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transproceed.2022.11.010 (2023).

Eyzaguirre, L. C. A. et al. The most frequent symptoms of postcholecystectomy syndrome for cholelithiasis patients older than 40 years of age. Int. J. Gastrointest. Interv. 12, 55–56. https://doi.org/10.18528/ijgii220064 (2023).

Shrestha, R., Chayaput, P., Wongkongkam, K. & Chanruangvanich, W. Prevalence and predictors of postcholecystectomy syndrome in Nepalese patients after 1 week of laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 14, 4903. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55625-1 (2024).

Alotaibi, A. M. Post-cholecystectomy syndrome: a cohort study from a single private tertiary center. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 18, 383–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtumed.2022.10.004 (2023).

Huang, R. L. et al. Diagnosis and treatment of post-cholecystectomy diarrhoea. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 15, 2398–2405. https://doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v15.i11.2398 (2023).

Jin, E. H. et al. Increased risk of major depressive disorder after cholecystectomy: a Nationwide Population-based Cohort Study in Korea. Clin. Transl Gastroenterol. 12, e00339. https://doi.org/10.14309/ctg.0000000000000339 (2021).

Tsai, M. C., Chen, C. H., Lee, H. C., Lin, H. C. & Lee, C. Z. Increased risk of depressive disorder following cholecystectomy for gallstones. PLoS One. 10, e0129962. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0129962 (2015).

Parkman, H. P. et al. Cholecystectomy and clinical presentations of gastroparesis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 58, 1062–1073. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-013-2596-y (2013).

Talseth, A., Edna, T. H., Hveem, K., Lydersen, S. & Ness-Jensen, E. Quality of life and psychological and gastrointestinal symptoms after cholecystectomy: a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. Gastroenterol. 4, e000128. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgast-2016-000128 (2017).

Brawman-Mintzer, O. et al. Psychosocial characteristics and pain burden of patients with suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction in the EPISOD multicenter trial. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 109, 436–442. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2013.467 (2014).

Causes of Death Statistics in 2021. 3. Statistics Korea, (2021).

Trauner, M., Claudel, T., Fickert, P., Moustafa, T. & Wagner, M. Bile acids as regulators of hepatic lipid and glucose metabolism. Dig. Dis. 28, 220–224. https://doi.org/10.1159/000282091 (2010).

Pols, T. W., Noriega, L. G., Nomura, M., Auwerx, J. & Schoonjans, K. The bile acid membrane receptor TGR5: a valuable metabolic target. Dig. Dis. 29, 37–44. https://doi.org/10.1159/000324126 (2011).

Jiang, H. et al. Altered fecal microbiota composition in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav. Immun. 48, 186–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2015.03.016 (2015).

Kelly, J. R. et al. Transferring the blues: Depression-associated gut microbiota induces neurobehavioural changes in the rat. J. Psychiatr Res. 82, 109–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.07.019 (2016).

O’Gara, B. et al. New onset postoperative depression after major surgery: an analysis from a national claims database. BJA Open. 8, 100223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjao.2023.100223 (2023).

Ghoneim, M. M. & O’Hara, M. W. Depression and postoperative complications: an overview. BMC Surg. 16 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-016-0120-y (2016).

Seong, S. C. et al. Cohort profile: the National Health Insurance Service-National Health Screening Cohort (NHIS-HEALS) in Korea. BMJ Open. 7, e016640. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016640 (2017).

Quan, H. et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med. Care. 43, 1130–1139. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83 (2005).

Choi, Y. & Choi, J. W. Association of sleep disturbance with risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in patients with new-onset type 2 diabetes: data from the Korean NHIS-HEALS. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 19, 61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-020-01032-5 (2020).

Kim, J. A., Choi, S., Choi, D. & Park, S. M. Pre-existing Depression among newly diagnosed Dyslipidemia patients and Cardiovascular Disease Risk. Diabetes Metab. J. 44, 307–315. https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2019.0002 (2020).

Nilsson, E., Ros, A., Rahmqvist, M., Backman, K. & Carlsson, P. Cholecystectomy: costs and health-related quality of life: a comparison of two techniques. Int. J. Qual. Health Care. 16, 473–482. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzh077 (2004).

Sehlo, M. G. & Ramadani, H. Depression following hysterectomy. Curr. Psychiatry. 17, 1–6 (2010).

Shen, T. C. et al. The risk of depression in patients with cholelithiasis before and after cholecystectomy: a population-based cohort study. Med. (Baltim). 94, e631. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000000631 (2015).

Jukić, T., Margetić, B. A., Jakšić, N. & Boričević, V. Personality differences in patients with and without gallstones. J. Psychosom. Res. 169, 111322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2023.111322 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Abdominal obesity mediates the causal relationship between depression and the risk of gallstone disease: retrospective cohort study and mendelian randomization analyses. J. Psychosom. Res. 174, 111474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2023.111474 (2023).

Wu, T. et al. Gut microbiota dysbiosis and bacterial community assembly associated with cholesterol gallstones in large-scale study. BMC Genom. 14, 669. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-14-669 (2013).

Sauter, G. H. et al. Bowel habits and bile acid malabsorption in the months after cholecystectomy. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 97, 1732–1735. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05779.x (2002).

Chavez-Talavera, O., Tailleux, A., Lefebvre, P. & Staels, B. Bile Acid Control of Metabolism and Inflammation in Obesity, type 2 diabetes, Dyslipidemia, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 152 (e1673), 1679–1694. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.055 (2017).

Wang, W. et al. Cholecystectomy damages Aging-Associated Intestinal Microbiota Construction. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1402. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.01402 (2018).

Tetel, M. J., de Vries, G. J., Melcangi, R. C., Panzica, G. & O’Mahony, S. M. Steroids, stress and the gut microbiome-brain axis. J. Neuroendocrinol. 30 https://doi.org/10.1111/jne.12548 (2018).

Yoon, W. J. et al. The impact of Cholecystectomy on the gut microbiota: a case-control study. J. Clin. Med. 8 https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8010079 (2019).

Graham, M. E. et al. Gut and vaginal microbiomes on steroids: implications for women’s health. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 32, 554–565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2021.04.014 (2021).

Gao, F. et al. Stressful events induce long-term gut microbiota dysbiosis and associated post-traumatic stress symptoms in healthcare workers fighting against COVID-19. J. Affect. Disord. 303, 187–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.02.024 (2022).

Ros, E. & Zambon, D. Postcholecystectomy symptoms. A prospective study of gall stone patients before and two years after surgery. Gut 28, 1500–1504. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.28.11.1500 (1987).

Luman, W. et al. Incidence of persistent symptoms after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective study. Gut 39, 863–866. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.39.6.863 (1996).

Jaunoo, S. S., Mohandas, S. & Almond, L. M. Postcholecystectomy syndrome (PCS). Int. J. Surg. 8, 15–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2009.10.008 (2010).

Girometti, R. et al. Post-cholecystectomy syndrome: spectrum of biliary findings at magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. Br. J. Radiol. 83, 351–361. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr/99865290 (2010).

Pak, M. & Lindseth, G. Risk factors for Cholelithiasis. Gastroenterol. Nurs. 39, 297–309. https://doi.org/10.1097/sga.0000000000000235 (2016).

Weinert, C. R., Arnett, D., Jacobs, D. Jr. & Kane, R. L. Relationship between persistence of abdominal symptoms and successful outcome after cholecystectomy. Arch. Intern. Med. 160, 989–995. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.160.7.989 (2000).

Schmidt, M. et al. Post-cholecystectomy symptoms were caused by persistence of a functional gastrointestinal disorder. World J. Gastroenterol. 18, 1365–1372. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i12.1365 (2012).

Buono, J. L., Carson, R. T. & Flores, N. M. Health-related quality of life, work productivity, and indirect costs among patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 15, 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0611-2 (2017).

Carraro, A., Mazloum, D. E. & Bihl, F. Health-related quality of life outcomes after cholecystectomy. World J. Gastroenterol. 17, 4945–4951. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i45.4945 (2011).

Bisgaard, T., Rosenberg, J. & Kehlet, H. From acute to chronic pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective follow-up analysis. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 40, 1358–1364. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365520510023675 (2005).

McMahon, A. J. et al. Symptomatic outcome 1 year after laparoscopic and minilaparotomy cholecystectomy: a randomized trial. Br. J. Surg. 82, 1378–1382. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.1800821028 (1995).

Hsueh, L. N., Shi, H. Y., Wang, T. F., Chang, C. Y. & Lee, K. T. Health-related quality of life in patients undergoing cholecystectomy. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 27, 280–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kjms.2011.03.002 (2011).

Ali, S., Stone, M. A., Peters, J. L., Davies, M. J. & Khunti, K. The prevalence of co-morbid depression in adults with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet. Med. 23, 1165–1173. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01943.x (2006).

Li, Z., Li, Y., Chen, L., Chen, P. & Hu, Y. Prevalence of Depression in patients with hypertension: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Med. (Baltim). 94, e1317. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000001317 (2015).

Won, T. Y., Kang, B. S., Im, T. H. & Choi, H. J. The study of accuracy of death statistics. J. Korean Soc. Emerg. Med. 18, 256–262 (2007).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a scholarship from the BK21 FOUR education program, which was provided by the National Research Foundation of Korea.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contributionsStudy concept and design: J.Y., S.P., and S.M.PAcquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data: All the authorsDrafting of the manuscript: J.Y. and S.P.Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All the authorsStatistical analysis: J.Y. and S.P.Administrative, technical, or material support: All authors.Proofreading the article: S.H.Study supervision: S.M.P.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, J., Park, S., Jeong, S. et al. Association of cholecystectomy with short-term and long-term risks of depression and suicide. Sci Rep 15, 6557 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87523-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87523-5