Abstract

To determine the risk factors for poor prognosis of influenza-associated encephalopathy (IAE), 56 eligible children with IAE who were treated in the pediatric intensive care unit of Wuhan Children’s Hospital from January 2022 to December 2023 were selected for retrospective analysis and grouped according to poor prognosis or not, and independent risk factors for poor prognosis were found by regression analysis. Results showed 26 children (26/30, 46.4%) had a poor prognosis. In the univariate analysis, the poor prognosis group compared with the clinically cured group showed a significant increase in the number of days of hospitalization (3.0 vs. 9.5 days, P < 0.001), high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (6.80 vs. 1.88 mg/L, P = 0.003), interleukin-6 (20.26 vs. 8.24 pg/mL, P = 0.001), interleukin-10 (11.75 vs. 4.72 pg/mL, P = 0.003), alanine aminotransferase (104.0 vs. 20.0 U/L, P = 0.011), aspartate azelotransferase (186.5 vs. 37.0 U/L, P = 0.003), serum albumin (37.99 vs. 40.76 g/L, P = 0.042), prothrombin time (13.2 vs. 11.4 s, P = 0.017), D-dimer (4.34 vs. 0.44 mg/L FEU, P < 0.001), peripheral blood CD19 B-cell count (35.11 vs. 32.75 cells/µL, P = 0.018), and cerebrospinal fluid chloride (126.82 vs. 125.50 mmol/L, P = 0.027) were statistically different in the above 11 indicators. After binary logistic regression analysis, it was concluded that D-dimer was an independent risk factor for poor prognosis (odds ratio = 1.440, 95% confidence interval 1.052–1.972, P = 0.023), and the area under the curve (95% confidence interval) was 0.802 (0.680–0.924), P < 0.001. When D-dimer was ≥ 1.18 mg/L FEU, the occurrence of poor prognosis was predicted with sensitivity and specificity of 65.4% and 96.7%, respectively. In conclusion, IAE has a high incidence of poor prognosis, in which D-dimer is a possible risk factor with discriminatory value in assessing the occurrence of poor prognosis. However, due to the limitations of retrospective single-center small sample size data, more confirmation from multicenter large sample size studies is needed in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Influenza, which has been pandemic worldwide many times, is an acute respiratory disease caused by influenza A or B viruses, mainly in winter. Children are susceptible to influenza, and the infection rate is mostly higher than that of adults1,2. Although most children present only with influenza-like symptoms such as fever and cough, a small number of children will develop severe or even fatal complications in a short period, of which influenza-associated encephalopathy (IAE) is one of the most severe complications3. IAE is a syndrome characterized by acute episodes of severe and prolonged disorders of consciousness, most often in previously healthy children, which usually results in death or severe neurological deficits4. The lack of early diagnostic indicators for influenza-associated neurological injury leads to delayed early diagnosis of critical cases, which in turn results in poor prognosis and high mortality5. Hospitalization rates for influenza in children appear to have risen over the past three years due to some preventive and control measures during the COVID-19 pandemic6. Therefore, early identification and prediction of the risk of possible poor prognosis is critical for subsequent diagnosis and prognosis.

Domestic and international reports on the occurrence of IAE and the adverse prognosis after the occurrence of IAE in influenza-infected children admitted to pediatric intensive care units are numerous, mainly focusing on descriptive and cross-sectional studies7,8,9,10. Still, the analysis of the factors affecting their prognosis has been reported less frequently, especially the poor prognosis, which clinicians are most concerned with11. We hypothesized that it would be possible to collect several children with IAE who present with a poor prognosis and describe their risk factors for poor prognosis to assist physicians in early assessment of the risk of poor prognosis in IAE. Therefore, children with a diagnosis of IAE admitted to the PICU between January 2022 and December 2023 were retrospectively included in our center as study subjects.

Methods

Participants

This is a retrospective study, and 56 eligible children diagnosed with IAE diagnosed in Wuhan Children’s Hospital from January 2022 to December 2023 were selected for the study.

Diagnostic criteria for IAE

(i) impaired consciousness with a Glasgow Coma Scale severity of < 11 points for 24 h or more; (ii) cerebral edema observed on cranial computed tomography/ magnetic resonance; (iii) a positive influenza virus pharyngeal swab; and (iv) other illnesses that rule out impaired consciousness during infectious disease, including intracranial infections (e.g., bacterial meningitis), autoimmune encephalitis, cerebrovascular disease, traumatic, metabolic, and toxic diseases, and the effects of organ failure12,13,14.

Definition of poor prognosis for IAE

Poor prognosis is defined as death during hospitalization and nonmedical discharges, where nonmedical discharges for children are those in which the family requests that treatment be abandoned, including discontinuation of advanced life support and device-assisted therapy, and all nonmedical discharges are those in which the death occurs immediately after hospitalization or within one week.

Inclusion criteria

(i) age 28 days-18 years; (ii) meeting the diagnostic criteria for IAE; (iii) positive throat swabs for influenza virus antigen; and (iv) exclusion of other relevant etiologic factors that could explain the children’s neurological symptoms.

Exclusion criteria

(i) death before diagnosis; (ii) combination of other pathogens; and (iii) missing information and data.

The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Wuhan Children’s Hospital (approval number: 2023R008-E01). Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the Medical Ethics Committee of Wuhan Children’s Hospital waived the need of obtaining informed consent. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations (e.g. Helsinki guidelines).

Methodology

Data collection

Basic data and clinical indicators of children during hospitalization were collected by reviewing the electronic medical record system (Donghua, Beijing, China), including sex, age, weight, time of admission, days of hospitalization, vital signs, routine blood indices, high sensitivity C-reactive protein, ferritin, liver function, renal function, electrolytes, coagulation function, cytokines, immune cell counts, cerebrospinal fluid biochemistry, and other clinical indicators.

Treatment regimen

The primary treatment for all children was oral oseltamivir granules for antiviral and supportive therapy. All children diagnosed with acute necrotizing encephalopathy receive intravenous immunoglobulin (2 g/kg total) and high-dose corticosteroid therapy (10–30 mg/kg/day).

Statistical methods

SPSS 26.0 statistical software (IBM Corp., New York, NY, USA) was used for data analysis. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov method was used to test the normality of the measurements. Measurements that conformed to the normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and independent samples t-test was used to compare the two groups; measurements that did not conform to the normal distribution were expressed as median (Q1, Q3), and the Mann-Whitney test was used to compare the two groups. Count data were expressed as the number of cases (%), and comparisons between the two groups were made using the χ2 or Fisher’s exact test. Variables showing a significant difference (P < 0.05) between the groups in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate binary logistic regression analysis. The correlation and strength between the predictor variables in the regression model were measured using the variance inflation factor (VIF), in which VIF < 10 indicated “free of covariance.” The independent risk factors were derived using the backward elimination method. The maximum Youden index for continuous variables was calculated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves to determine the cutoff values and subsequently converted to dichotomous variables based on these cutoff values. GraphPad Prism 7.0 statistical analysis software (GraphPad, California, USA) was used to plot forest plots. P < 0.05 is considered a statistically significant difference.

Results

Demographic characteristics

A total of 56 eligible children with IAE were admitted to the intensive care unit of Wuhan Children’s Hospital from January 2022 to December 2023. These included 29 boys and 27 girls, with a median age of 5.0 (3.0,7.0) years. In the clinically cured group, there were 30 cases (53.6%), including 18 boys (60%), with a median age of 5.5 (3.3,7.0) years; in the poor prognosis group, there were 26 cases (46.4%), including 11 boys (42%), with a median age of 4.0 (3.0,6.5) years. In the poor prognosis group, 11 had persistent status epilepticus, 7 had multi-organ failure or diffuse intravascular coagulation, 3 had shock, 2 had in-hospital death, 1 had brain death, 1 had brain herniation, 1 had dystonia, and 23 had final nonmedical discharges, 2 were discharged with death, and 1 was discharged nonmedically with brain death. There were no statistically significant differences between the clinically cured group and the poor prognosis group regarding sex, height, weight, maximum body temperature, and admission blood pressure (P > 0.05). In contrast, the heart rate (135.0 vs. 104.8 beats per minute, P < 0.001) and respiratory rate (30.0 vs. 23.5 beats per minute, P = 0.011) were faster in the poor prognosis group than in the clinically cured group, and the difference was statistically significant. The number of days of hospitalization for the children in the poor prognosis group was significantly lower than that in the clinically cured group (3.0 vs. 9.5 days, P < 0.001). Distinguishing the poor prognosis group by the number of hospitalization days calculated from the ROC curve revealed that the area under the curve (AUC) for the probable poor prognosis group was found when the number of hospitalization days was ≤ 6 days (AUC = 0.796, 95% confidence interval 0.666–0.926, P < 0.001), and the sensitivity for predicting the probable poor prognosis outcome was 76.9%. The specificity was 83.3% when the number of hospitalization days was ≤ 6. (Table 1; Fig. 1)

ROC curves evaluating the discriminatory value of days of hospitalization for poor prognosis of influenza-associated encephalopathy. The horizontal coordinate is the false-positive rate, the vertical coordinate is the true-positive rate, the red 45° diagonal line indicates the baseline (minimum standard), and the blue solid line is the constructed ROC curve, with an area under the curve (95% confidence interval) of 0.796 (0.666, 0.926), P < 0.001. The maximum Youden index corresponded to an optimal cutoff value of 6 days, and when the number of days of hospitalization was ≤ 6, the differentiation between poor prognostic outcomes had a sensitivity of 76.9% and specificity of 83.3%. (ROC curve, receiver operating characteristic curve).

Laboratory tests

Laboratory tests mainly included peripheral blood routine, infection indexes, biochemical indexes, coagulation function, immune indexes, and cerebrospinal fluid examinations at admission. Among them, blood routine mainly included white blood cell count, neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, hemoglobin, and platelet count, and there was no statistically significant difference between the clinically cured group and the poor prognosis group in terms of the above indicators. Infection indicators were mainly incorporated into high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, cytokines, and ferritin, which were significantly higher in the poor prognosis group than in the clinically cured group, including high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (6.80 vs. 1.88 mg/L, P = 0.003), interleukin-6 (20.26 vs. 8.24 pg/mL, P = 0.001), and interleukin-10 (11.75 vs. 4.72 pg/mL, P = 0.003).

In terms of biochemical indexes, liver and kidney functions, and electrolyte indexes were mainly included, among which the alanine aminotransferase (104.0 vs. 20.0 U/L, P = 0.011) and aspartate aminotransferase (186.5 vs. 37.0 U/L, P = 0.003) in the group with poor prognosis were significantly higher than those in the clinically cured group. In contrast, the serum albumin (37.99 vs. 40.76 g /L, P = 0.042) was substantially lower than that of the clinically cured group, and the differences were all statistically significant. No statistically significant differences were seen between the two groups in renal function and electrolytes, including serum urea nitrogen, creatinine, sodium ions, potassium ions, calcium ions, and chloride ions.

In coagulation, the poor prognosis group had a prolonged prothrombin time (13.2 vs. 11.4 s, P = 0.017) and significantly higher D-dimer (4.34 vs. 0.44 mg/L FEU, P < 0.001) compared with the clinically cured group. Immunological indexes were mainly included in the immune cell counts, including T cells, B cells, and natural killer cells, in which CD19 B-cell count was elevated in the poor prognosis group compared with the clinically cured group (35.11 vs. 32.75 cells/µL, P = 0.018). In contrast, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding CD3, CD4, and CD8 T cells and natural killer cells (P > 0.05). The cerebrospinal fluid indexes mainly included cerebrospinal fluid cell count, proteins, glucose, and chloride ions, in which the cerebrospinal fluid chloride ions in the poor prognosis group (126.82 vs. 125.50 mmol/L, reference-range 118-128mmol/L, P = 0.027) were higher than that in the clinically cured group, and the difference was statistically significant (Table 2).

Clinical manifestations and imaging features

We included some of the respiratory symptoms and neurologic manifestations to assist in the evaluation of these children with IAE, with no statistically significant difference between the poor prognosis group and the clinically cured group in terms of cough and stuffy/runny nose. Almost all children had fever (96%), but there was no statistical difference between the two groups in terms of whether or not they had fever (P > 0.05). We included Glasgow coma scale, cranial imaging, and electroencephalography (EEG) to assist in assessing the neurologic performance of children with IAE. Among them, the Glasgow coma scale was significantly lower in the poor prognosis group than in the clinically cured group (7 vs. 12, P < 0.001), suggesting that the deeper the coma, the worse the prognosis may be. All patients underwent magnetic resonance or computed tomography during hospitalization, in which most of the children showed acute brain swelling (46%), followed by acute necrotizing encephalopathy and mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion, and one of them developed brain herniation. However, there was no statistically significant difference in imaging between the two groups. EEG was performed during the hospitalization of all patients, in which the EEG was predominantly slow wave (62%), 90% of the clinically cured group was predominantly slow wave, whereas the EEG of the group with poor prognosis mostly showed electrostatic resting and slow wave, which suggests that this part of the children had already entered into deep coma and the combination of severe brain injury, and even brain death may eventually occur (Table 3; Fig. 2).

Analysis of common cranial images of influenza-associated encephalopathy. Panels (A) and (B) Computed tomography of the brain showing diffuse brain swelling with poorly demarcated gray-white matter suggestive of acute cerebral swelling. Panels (C) and (D) Showing brain swelling with foramen magnum occipitalis hernia. Panels (E) through (H) Showing DWI sequences of magnetic resonance images (MRI) of mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion, where (E) and (G) are the initial images, and (F) and (H) are the follow-up images with lesion disappearance after 1 week. Panels (I) through (K) MRI showing acute necrotizing encephalopathy, with T2 Flair sequences in Figures (I) and (K), and DWI sequences in Figures (J) and (L), showing that the main lesion is located in the thalamic region.

Independent risk factors and predictive value

Independent risk factors for poor prognosis in IAE

In the univariate analysis of the above demographic characteristics and laboratory tests, 15 variables were statistically different (P < 0.05), including days of hospitalization, respiratory rate, heart rate, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, interleukin-10, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, serum albumin, prothrombin time, D-dimer, CD19 B-cell count, cerebrospinal fluid chloride, Glasgow coma scale, and EEG. Five indicators, including days of hospitalization, respiratory rate, heart rate, Glasgow coma scale, and EEG, were not included because they were clinical manifestations or outcomes of IAE., and the remaining 10 indicators were included in binary logistic regression analyses. Defining the poor prognosis group as 1 and ultimately using the backward elimination method stepwise regression, the resulting independent risk factor was D-dimer (odds ratio [OR] = 1.440, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.052–1.972, P = 0.023), suggesting that for every 1 mg/L FEU elevation in D-dimer, the risk of developing a poor prognosis was increased by a factor of 1.440 when compared with the clinically cured group (Fig. 3).

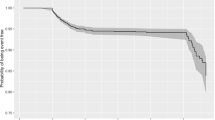

Predictive value of D-dimer in differentiating IAE presenting with poor prognosis

The area under the curve (AUC) for the occurrence of poor prognostic outcomes with elevated D-dimer was calculated using the ROC curve (AUC = 0.802, 95% CI 0.680–0.924, P < 0.001). The sensitivity and specificity for the occurrence of poor prognostic outcomes were 65.4% and 96.7%, respectively, when the D-dimer was ≥ 1.18 mg/L FEU, according to the corresponding cutoff values for the maximum Youden index (Fig. 4).

ROC curve assessing the discriminatory value of D-dimer for poor prognosis in influenza-associated encephalopathy. The horizontal coordinate is the false-positive rate; the vertical coordinate is the true-positive rate; the red 45° diagonal indicates the baseline (minimum standard), and the blue solid line is the constructed ROC curve with an area under the curve (95% confidence interval) of 0.802 (0.680, 0.924), P < 0.001. When D-dimer was ≥ 1.18 mg/L FEU, the sensitivity and specificity for differentiating poor prognosis were 65.4% and 96.7%, respectively. (ROC curve, receiver operating characteristic curve).

Discussion

Most influenza cases have a favorable prognosis, but more children with severe influenza develop severe illness than adults. Severely ill children rapidly progress to acute respiratory failure, sepsis, septic shock, heart failure, renal failure, and even multi-organ dysfunction, and IAE is one of the leading causes of death15. On the one hand, IAE generally presents with convulsions based on influenza-like symptoms and progresses to coma at an early stage, with impaired consciousness occurring in about 70% of cases within 24 h of fever onset. The majority of children no longer regain consciousness after the development of convulsions, resulting in an inferior prognosis16. On the other hand, some children have no specific manifestations in the early stage, similar to upper respiratory tract infections. Some of them are given oral medication home treatment after the first diagnosis. Still, they are readmitted to the hospital due to convulsions or impaired consciousness, and their condition progresses rapidly16, which makes them prone to medical disputes. Therefore, we collected children with IAE admitted to the intensive care unit of our hospital and found that a significant proportion (26/30, 46.4%) of the children had a poor prognosis, leaving severe complications or even death, which is consistent with relevant studies17,18, suggesting that IAE urgently needs to be taken seriously by pediatricians. So, we collected and summarized the findings and shared them with colleagues to provide specific references.

In this study, we collected a total of 56 eligible children with IAE with a median age of 5.0 (3.0, 7.0) years, which is consistent with previous reports on the high prevalence of acute encephalopathy in children under the age of 5 years19,20. This suggests the need for early vigilance and aggressive treatment in younger children, especially young children with influenza, once evidence of encephalopathy such as high fever, convulsions, and altered consciousness is present. The median number of days of hospitalization for all children with IAE admitted to the intensive care unit was 7.0 (3.0, 12.5) days, which is not an extended total hospital stay and may further suggest that the disease progresses rapidly. Indeed, the typical clinical presentation of IAE is a sudden onset of hyperthermia and convulsions, followed by rapid onset of severe impairment of consciousness and early progression to coma, with some children already presenting with neurologic symptoms in the emergency or outpatient setting. Our results suggest that children in the poor prognosis group had shorter hospitalization days (3.0 vs. 9.5 days, P < 0.001) relative to the clinically cured group. This may be because, on the one hand, the disease progressed more rapidly in the poor prognosis group, and most of the children showed unrelieved convulsive persistence, which accelerated the brain damage; on the other hand, some of the children showed multiple organ function damage, respiratory and circulatory failure, and even cardiac arrest, which resulted in severe and irreversible injuries in a short period, and increased the difficulty of treatment. Although it is single-center data, it also suggests that the treatment and progression of children with IAE within 6 days of hospitalization is essential to the prognosis, and we need to be alert to the rapid progression of children with IAE in a short period. Active referral is necessary for hospitals without the conditions. The results suggest that all children presented with hyperthermia, with a median temperature of 39.3 (39.0, 40.0) °C, which is consistent with the clinical presentation of IAE, suggesting the need for monitoring and prompt assessment of intracranial conditions such as cranial imaging and electroencephalography after the development of hyperthermia combined with influenza central nervous system manifestations. However, there was no statistically significant difference between the clinically cured group and the poor prognosis group regarding maximum body temperature (39.3 vs. 39.3 ℃, P > 0.05). Therefore, other tests need to be refined to assist in assessing the risk of developing a poor prognosis.

By further collecting some laboratory test indicators, we found that the poor prognosis group had more severe infections, organ damage, and inflammatory reactions compared with the clinically cured group. These indicators provided some value in distinguishing between encephalopathies with severe or poor prognosis. However, due to the lack of specificity, we further performed regression analyses to exclude confounding factors. We found that only the elevation of D-dimer was an independent influence on poor prognosis. When D-dimer was ≥ 1.18 mg/L FEU, the sensitivity for distinguishing poor prognostic outcomes was 65.4%, and the specificity was 96.7%, suggesting that elevated D-dimer may indicate persistent poor prognosis in IAE. This may be due to abnormalities in the microcirculation and coagulation function itself after multi-organ dysfunction. We observed that children in the poor prognosis group had more severe organ dysfunction and higher aminotransferases, which may also lead to secondary coagulation abnormalities exacerbated by decreased coagulation factors, and some children with poor prognosis developed disseminated intravascular coagulation, all of which may have led to an elevation of D-dimer, especially in the poor prognosis group. On the other hand, it is now widely recognized internationally that the onset of IAE is due to the inflammatory response caused by an infection of the organism by the influenza virus. The increased secretion of cytokines by the patient’s peripheral blood mononuclear cells triggers a cytokine storm. It enters the central nervous system through the damaged blood-brain barrier, thus causing lesions4,21. Whereas inflammatory response and cytokine storm can damage vascular endothelial cells, where IL-6 directly affects vascular endothelial cells, vascular endothelial cells produce many cytokines and chemokines that activate the coagulation cascade. Abnormal regulation of endothelial cells characterized by coagulation abnormality and vascular leakage is a common complication of cytokine storm22. It has been reported23 that abnormal elevation of interleukin 6 is observed in both serum and cerebrospinal fluid during the acute phase of IAE, and blood levels are higher than cerebrospinal fluid levels. In conclusion, IAE is a systemic disease in which cytokine storms play an important therapeutic role, leading directly to systemic, including cerebral vascular endothelial damage through high cytokines, followed by cerebral edema, encephalopathy, vascular endothelial damage, and then secondary thrombocytopenia, coagulation abnormality, microthrombosis, multiorgan functional damage, and even disseminated intravascular coagulation, leading to abnormally elevated D dimer levels. In the present study, interleukins were significantly elevated in children in the poor prognosis group, consistent with previous studies. Currently D-dimer is mainly used in the assessment of pulmonary embolism and diffuse intravascular coagulation, but have also been found to be significantly elevated in some specific infectious diseases24. Significantly elevated D-dimer has been reported in patients with COVID-19 and associated with severe outcomes25, suggesting that D-dimer can be used to assess the potential for poor prognosis in infectious diseases. Some scholars have found that decreased lymphocyte counts, abnormalities in liver function, and serum sodium ions in children with IAE may be risk factors for death in IAE, but there are basically no reports on the correlation between D-dimer and IAE26. Compared to previous studies, we found for the first time that elevated D-dimer was a possible independent risk factor for poor prognosis in IAE with an excellent predictive value. This suggests that monitoring coagulation functions, especially D-dimer, may assist us in evaluating the condition and guiding the prognosis after admission of IAE to the intensive care unit.

Of course, our study has some limitations. On the one hand, there may have been some selection bias because of the low prevalence of IAE, the small number of patients, and the fact that this was a single-center retrospective study. For example, we included only common and readily available clinical indicators, which resulted in omitting some potentially superior predictors. In addition, we selected children based on retrospective screening of discharge diagnoses and examination findings, which left some children with other underlying etiologies leading to elevated D-dimer that were not adequately and effectively excluded. Conducting prospective randomized controlled trial studies is clinically challenging due to the very low incidence of IAE and the adverse outcomes it leads to. However, its high mortality rate determines that more studies are needed to clarify it, and in the future, we need more potential biomarkers to predict it or to validate our results by large, multicenter sample size data. On the other hand, there is no standardized diagnostic criteria for IAE, and although some of these children were diagnosed with influenza, we were unable to determine whether they also had other viral infections. Some of the children were comatose at the time of admission to the hospital, so it was not possible to assist in identifying autoimmune encephalitis by observing the children for personality and psychiatric symptoms. In some cases, brain death or brain herniation occurred during the course of the disease, and the condition changed so rapidly that it was impossible to determine in time whether it was due to the progression of IAE or other diseases. Therefore, in the future, it may be necessary to perform pathogen high-throughput sequencing detection and autoimmune encephalitis-associated antibody tests on the blood and cerebrospinal fluid of children with suspected IAE. However, the significance of our study is that summarizing and analyzing some of the pathogenetic features of IAE can provide a reference for pediatricians in assessing IAE, especially the evaluation of the risk of poor prognosis. Early monitoring and treatment or referral provide some reference value for children to get timely management and early identification.

Conclusion

Although our results are based on a single-center small sample size study, we expect that summarizing the possible risk factors for poor prognosis during the onset of IAE may help pediatricians evaluate children with influenza earlier and provide an early warning possibility of poor prognosis for some of the children with IAE.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Committee on Infectious Diseases. Recommendations for Prevention and control of influenza in children, 2022–2023. Pediatrics 150(4), e2022059275 (2022).

Antoon, J. W. et al. Guideline-concordant antiviral treatment in children at high risk for influenza complications. Clin. Infect. Dis. 76(3), e1040–e1046 (2023).

Britton, P. N. et al. The spectrum and burden of influenza-associated neurological disease in children: Combined encephalitis and influenza sentinel site surveillance from Australia, 2013–2015. Clin. Infect. Dis. 65(4), 653–660 (2017).

Mizuguchi, M., Yamanouchi, H., Ichiyama, T. & Shiomi, M. Acute encephalopathy associated with influenza and other viral infections. Acta Neurol. Scand. 115(4 Suppl), 45–56 (2007).

Ekstrand, J. J. Neurologic complications of influenza. Semin Pediatr. Neurol. 19(3), 96–100 (2012).

Kiefer, A., Kabesch, M. & Ambrosch, A. The frequency of hospitalizations for RSV and influenza among children and adults. Dtsch. Arztebl Int. 120(31–32), 534–535 (2023).

Huijsmans, R. L. N., Braber, A., Fokke, C., Lo Ten Foe, J. R. & Kuindersma, M. Influenza-geassocieerde acute necrotiserende encefalitis [influenza-associated acute necrotizing encephalitis: Unknown makes undertreated?]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 167, D7537 (2023).

Yu, M. K. L. et al. Clinical spectrum and Burden of influenza-associated neurological complications in hospitalised paediatric patients. Front. Pediatr. 9, 752816 (2022).

Togashi, T. Influenza-associated encephalitis/encephalopathy in childhood. Nihon Rinsho 58(11), 2255–2260 (2000).

Sun, R., Zhang, X., Jia, W., Li, P. & Song, C. Analysis of clinical characteristics and risk factors for death due to severe influenza in children. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 43(3), 567–575 (2024).

Song, Y. et al. Influenza-Associated Encephalopathy and Acute Necrotizing Encephalopathy in children: A retrospective single-center study. Med. Sci. Monit. 27, e928374 (2021).

Sugaya, N. Influenza-associated encephalopathy in Japan. Semin Pediatr. Infect. Dis. 13, 79–84 (2002).

Shiomi, M. [Pathogenesis of acute encephalitis and acute encephalopathy]. Nihon Rinsho 69(3), 399–408 (2011).

Mizuguchi, M. et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute encephalopathy in childhood. Brain Dev. 43(1), 2–31 (2021).

Frankl, S., Coffin, S. E., Harrison, J. B., Swami, S. K. & McGuire, J. L. Influenza-Associated neurologic complications in hospitalized children. J. Pediatr. 239, 24–31 (2021).

Sugaya, N. Influenza-associated encephalopathy in Japan. Semin Pediatr. Infect. Dis. 13(2), 79–84. https://doi.org/10.1053/spid.2002 (2002).

Newland, J. G. et al. Neurologic complications in children hospitalized with influenza: Characteristics, incidence, and risk factors. J. Pediatr. 150(3), 306–310 (2007).

Nagao, T. et al. Prognostic factors in influenza-associated encephalopathy. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 27(5), 384–389 (2008).

Morishima, T. et al. Encephalitis and encephalopathy associated with an influenza epidemic in Japan. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35(5), 512–517 (2002).

Lafond, K. E. et al. Global respiratory hospitalizations—influenza proportion positive (GRIPP) working group. Global role and burden of influenza in pediatric respiratory hospitalizations, 1982–2012: A systematic analysis. PLoS Med. 13(3), e1001977 (2016).

Nara, A. et al. An unusual autopsy case of cytokine storm-derived influenza-associated encephalopathy without typical histopathological findings: Autopsy case report. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 36(1), 3–5 (2015).

Kang, S. & Kishimoto, T. Interplay between interleukin-6 signaling and the vascular endothelium in cytokine storms. Exp. Mol. Med. 53(7), 1116–1123 (2021).

Morishima, T. Influenza-associated encephalopathy. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 44(11), 965–969 (2004).

Weitz, J. I., Fredenburgh, J. C. & Eikelboom, J. W. A test in context: D-dimer. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 7(19), 2411–2420 (2017).

Lippi, G. & Favaloro, E. J. D-dimer is associated with severity of coronavirus disease 2019: A pooled analysis. Thromb. Haemost. 120(5), 876–878 (2020).

Bi, J., Wu, X. & Deng, J. Mortality risk factors in children with influenza-associated encephalopathy admitted to the paediatric intensive care unit between 2009 and 2021. J. Paediatr. Child Health https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.16611 (2024).

Acknowledgements

YZ discloses support for the research of this work from the Pediatric Cardiovascular Disease Research Unit of Wuhan Children’s Hospital [grant number 2022FEYJS007]. CL discloses support for the publication of this work from the Soaring Plan of Youth Talent Development of Wuhan Children’s Hospital [grant number 2023TFJH02].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.W. and L.Z. wrote the manuscript, X.C. collected and organized the data, H.L., H.Z., and Y.S. statistics and participated in the discussion; Y.Z. and C.L. conceptualized the paper and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, H., Zeng, L., Cheng, X. et al. Elevated D-dimer on admission may predict poor prognosis in childhood influenza associated encephalopathy. Sci Rep 15, 3122 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87690-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87690-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Risk factors and predictive model for pediatric influenza-associated encephalopathy symptoms: a retrospective study

BMC Infectious Diseases (2025)