Abstract

The digital revolution in power systems has increased their complexity and interconnectivity, thereby exacerbating the risk of cyberattacks. To protect critical power infrastructure, there is an urgent need for an advanced intrusion detection system capable of capturing the intricate interactions within smart grids. Although traditional graph neural network (GNN)-based methods have exhibited substantial potential, they primarily rely on network data (e.g., IP addresses and ports) to construct the graph structure, failing to adequately integrate physical data from power grid devices. Moreover, these methods typically employ fixed activation functions in downstream deep networks, which limits the accurate representation of complex nonlinear attack patterns, thereby reducing detection accuracy. To address these challenges, this paper introduces GraphKAN, a novel intrusion detection framework that leverages graph attention network (GAT) and Kolmogorov–Arnold network (KAN) to enhance detection precision in smart grids. GraphKAN firstly constructs a graph-structured representation with power devices, information technology devices, and communication network devices as nodes, and integrates the physical connections and logical dependencies among infrastructure elements as edges, providing a comprehensive view of device interactions. Furthermore, the GAT module utilizes multi-head attention mechanisms to dynamically allocate node weights, extracting global features that encompass both feature information and interaction patterns. The KAN introduces learnable activation functions based on parameterized B-splines, enhancing the nonlinear expression of the global features extracted by GAT and significantly improving the detection accuracy of complex attack patterns. Experiments conducted on datasets obtained from Mississippi State University and Oak Ridge National Laboratory demonstrate that GraphKAN achieves detection accuracies of 97.63%, 98.66%, and 99.04% for binary, ternary, and 37-class intrusion detection tasks, respectively. These results represent substantial improvements over state-of-the-art models, including GA-RBF-SVM, BGWO-EC, and Net_Stack, with accuracy gains of 5.73%, 0.89%, and 3.52%, respectively. The findings underscore the efficacy of GraphKAN in enhancing intrusion detection accuracy in smart grids and its robust performance in complex attack scenarios.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid advancement of information technologies, including the Internet of Things (IoT), big data analysis, and artificial intelligence, has significantly expanded the capabilities of smart grids1. However, this expansion has also led to increased network complexity and interconnectivity, which in turn has heightened cybersecurity threats to critical power infrastructures. A notable example is the 2015 cyberattack on the Ukrainian power grid, which resulted in a six-hour power outage for approximately 225,000 users, causing significant economic and social disruption2. Attackers can exploit advanced persistent threats (APTs) and coordinated attacks to induce severe operational failures and large-scale power outages, thereby jeopardizing the secure and stable functioning of the grid system. According to an analysis by POLITICO of U.S. Department of Energy data, the number of cyberattacks and threat incidents reported in August 2023 increased by nearly 70% compared to 20223. Consequently, intrusion detection systems (IDS) are crucial for ensuring the secure operation of smart grids, with their detection accuracy being pivotal in identifying potential threats4.

Intrusion detection systems (IDS) are mainly categorized into signature-based and anomaly-based detection methods5. Signature-based methods rely on network activities to known attack signatures, yet they are incapable of detecting unknown attacks. Anomaly-based detection methods establish a baseline for normal network behavior, and any deviation flagging any deviations as potential intrusions. Although anomaly-based methods can detect previously unoknwn attacks, they often suffer from suboptimal accuracy. To overcome these limitations, there has a growing interest in applying machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) techniques to intrusion detection. Various studies have employed feature selection techniques such as Information Gain6, Principal Component Analysis (PCA)7, Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO)8, and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)9 to extract the most representative features. Other research have utilized models like Convolutional Neural network (CNN)10, Deep Belief network (DBN)11, and Gated Recurrent Units (GRU)12 to capture the complex characteristics of input data, thereby enhancing the accuracy of intrusion detection. However, these methods typically treat data as isolated points, neglecting the structured relationships between data points. and thus fail to effectively model the interaction characteristics and topological relationships between devices in smart grids.

Smart grid data is inherently highly interconnected, exhibiting significant graph structural characteristics in terms of data flows between devices, communication patterns, and physical connections. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), with their unique strengths in modeling graph-structured data, have become an important research direction in smart grid intrusion detection. Recent works have adopted methods such as Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN)13, Graph Attention Networks (GAT)14, and Dynamic Graph Neural Networks (DGNN)15, demonstrating high potential in extracting global topological and feature information by embedding node and edge relationships into the models to capture device interactions and abnormal behavior patterns. For instance, Abinesh et al.16 proposed a botnet attack detection model based on Deep Graph Convolutional Neural Networks (DGCNN), addressing the challenge of capturing botnet behaviors by constructing graph structures from network traffic. Kisanger et al.17 designed a GNN-based multi-stage attack intrusion detection framework, effectively overcoming the limitations of traditional methods in detecting complex multi-stage threats. Meanwhile, Tran et al.18 proposed a graph embedding model (FN-GNN) combining GCN and GraphSAGE, significantly improving anomaly detection accuracy by constructing traffic data graph structures based on IP relationships. However, these GNN-based methods often treat IP addresses and ports as nodes, lacking deep modeling of smart grid physical devices and their logical relationships, making it difficult to comprehensively capture the complex multi-dimensional interaction characteristics between devices. Furthermore, fixed and singular activation functions in GNN downstream classification tasks limit the nonlinear feature expression capability for complex attack patterns, resulting in insufficient detection accuracy.

The objective of this paper is to enhance the accuracy of intrusion detection in smart grids. This work proposes an advanced graph-driven framework for intrusion detection in smart grids (GraphKAN). GraphKAN constructs graphs by utilizing infrastructure devices within smart grids as nodes, with the relationship between devices as edges, effectively capturing the global topological characteristics of smart grids. Moreover, the multi-head attention mechanism of Graph Attention Network (GAT) dynamically allocates weights based on the importance of node interactions, comprehensively extracting global features. Additionally, the learnable activation functions of Kolmogorov–Arnold network (KAN) enhance the downstream threat detection model, improving the expression capability of nonlinear features and significantly increasing the detection accuracy of complex attack patterns. The integration of GAT and KAN in the proposed GraphKAN model leverages the strengths of GAT for capturing dynamic interactions within graph-structured data and KAN’s proficiency in classifying intricate attack patterns. This synergistic approach enables GraphKAN to globally analyze nonlinear feature relationships within smart grids and accurately detect cyberattacks. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

-

(1)

A graph construction method based on the topology of power grids is proposed. Within this method, power devices, information technology devices, and communication network devices are designated as nodes, while physical connections and logical dependencies among grid components are utilized as edges to construct a graph that accurately represents the detailed structure of smart grids. By allocating features across various devices, the method effectively integrates network information with physical data, comprehensively representing the complex multi-dimensional relationships between smart grid devices and accurately describing the topological characteristics of the grid.

-

(2)

A graph-driven intrusion detection framework for smart grids, named GraphKAN, is developed, which integrates the strengths of the Graph Attention Network (GAT) and the Kolmogorov–Arnold Network (KAN). The GAT module employs a multi-head attention mechanism to dynamically adjust the weights between nodes based on graph-structured data, effectively aggregating information from neighboring nodes to extract global features that capture the complex interaction patterns within smart grids. Additionally, the KAN module utilizes parameterized B-spline functions to construct learnable activation functions, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to express non-linear features extracted by GAT and significantly improving the precision in recognizing complex attack patterns. This synergistic approach leverages the feature extraction capabilities of GAT and the non-linear expressive power of KAN, substantially enhancing the accuracy of the GraphKAN model in detecting intrusions.

-

(3)

A performance evaluation of the proposed GraphKAN model was conducted using power system attack datasets. The experimental results demonstrate that GraphKAN achieved accuracies of 97.63%, 98.66%, and 99.04% for binary, ternary, and 37-class tasks, respectively. Compared to state-of-the-art models such as GA-RBF-SVM, BGWO-EC, and Net_Stack models, GraphKAN exhibited significant improvements in accuracy, with enhancements of 5.73%, 0.89%, and 3.52%, respectively. The results verify the effectiveness and superiority of the proposed GraphKAN model in smart grid intrusion detection.

The remaining sections of this paper are organized as follows: the literature review is presented in the Related Work Section. The experimental results and comparisons are depicted and discussed in the Experimental Section. Conclusion and Future Work Section concludes the whole paper and proposes future work.

Related work

Smart grids, as an innovative paradigm in power systems, integrate communication technology with traditional power infrastructure, thereby enabling the intelligent management of electrical energy19 However, the rapid expansion of smart grids has increased the risk of cyberattacks20. Consequently, the majority of researchers have focused on intrusion detection systems (IDS) to enhance the secure operation of smart grids. For instance, Liu et al.21 developed an IDS approach that combines random forest (RF) and particle swarm optimization (PSO), achieving an accuracy of 95.89% on the NSL-KDD dataset. Chatzimiltis et al.22 introduced a distributed intrusion detection model for smart grids, integrating segmentation learning with federated learning techniques. Hu et al.23 applied the deep deterministic policy gradient (DDPG) algorithm to optimize the feature selection process, proposing an adaptive feature enhancement model. Similarly, Shi et al.24 developed a distributed IDS method that utilizes local state estimation to detect hidden attacks in smart grids, demonstrating high detection accuracy while reducing false alarm rates. Gupta et al.25 devised a method based on an intelligent recurrent artificial neural network (ILANN) to detect false data injection attacks (FDIA) in smart grids, achieving rapid detection by comparing system deviations and device load configurations. Kanna et al.26 developed an integrated spatial-temporal feature learning framework that combines an optimized convolutional neural network with a hierarchical multi-scale LSTM network, employing Lion Swarm Optimization for hyperparameter tuning to enhance model adaptability. Furthermore, Kanna et al.27 implemented a MapReduce-based Conv-LSTM architecture for distributed computing in power systems, enabling efficient processing of large-scale grid monitoring data while maintaining detection accuracy through optimized feature extraction. Additionally, Kanna et al.28 proposed a DoS attack detection mechanism utilizing PCA-based dimensionality reduction to transform network traffic patterns into two-dimensional representations, effectively reducing computational complexity while maintaining detection performance. Yakub et al.29 proposed a hybrid ensemble learning method for intrusion detection, combining multiple machine learning models to achieve anomaly detection, significantly improving detection accuracy while reducing false positives and false negatives. In another work, Yakub et al.30 introduced a DCNN and LSTM hybrid model based on autoencoder dimensionality reduction, achieving excellent detection performance across multiple datasets. To address the challenge of imbalanced network traffic, Yakub et al.31 further proposed an intrusion detection method based on Variational Autoencoder (VAE) and XGBoost, incorporating class-wise focal loss to enhance the detection of minority class attacks. Muthubalaji et al.32 proposed an intrusion detection algorithm by integrating AdaBelief Exponential Feature Selection (AEFS) with Kernel-based Extreme Neural network (KENN), achieving superior accuracy compared to traditional hand-crafted feature-based methods. Diaba et al.33 proposed a smart grid DDoS attack detection model combining CNN and GRU, which exploits CNN for spatial feature extraction and GRU for capturing temporal dependencies. Wang et al.34 proposed an enhanced intrusion detection method based on a deep belief network. Yakub et al.35 proposed a novel XAI-based ensemble transfer learning method (XAIEnsembleTL-IoV) for detecting zero-day botnet attacks. By integrating transfer learning with XAI techniques, the model effectively enhances detection capabilities while improving interpretability and transparency.

While these methods have demonstrated excellent performance in smart grid intrusion detection, they often overlook the topological structure information of power grids, which may reduce the accuracy of intrusion detection. To address this issue, researchers have turned to Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), which can effectively process data from complex network structures. Sweeten et al.36 proposed a network intrusion detection method based on GNNs that integrates physical and network protocol data. Wang et al.37 designed an intrusion detection model based on a spatiotemporal graph neural network (N-STGAT), which analyzes the spatiotemporal data correlation within the system. Xu et al.38 developed a self-supervised intrusion detection model based on a graph attention network, enhancing the representation ability of network traffic features through a graph attention mechanism and contrastive learning strategy. Xia et al.39 introduced an innovative method leveraging Graph Attention Networks (GAT) for detecting False Data Injection Attacks (FDIA) in power grids. This method models grid data as non-Euclidean graph signals and employs attention mechanisms to adaptively assign weights to graph shift operators. Evaluations on IEEE 14-bus and 39-bus test systems demonstrated that this method has superior FDIA localization accuracy and robustness compared to benchmark techniques.

Although the existing graph-based models have offered reliable and effective performances for intrusion detection in smart grid, the following key issues have not been fully explored: (1) Existing GNN-based methods predominantly depend on network information (e.g., IP addresses and ports) to construct graph-structured data, overlooking the physical information of smart grids. This oversight may lead to an inadequate capture of the global and local interaction characteristics of device-level topological structures, thereby diminishing the capability to accurately extract key features within smart grids during the feature extraction process. (2) most GNN methods employed in downstream classification tasks typically utilize multilayer perceptron (MLP) or deep neural network (DNN) architectures, which are limited by fixed and singular activation functions. This constraint hampers their ability to model complex nonlinear features, resulting in suboptimal detection accuracy, especially in scenarios involving sophisticated threats.

Proposed method

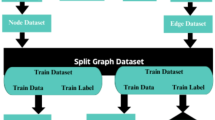

Figure 1 illustrates the flowchart of proposed GraphKAN, which is designed to improve the precision of intrusion detection systems within smart grids. The initial phase involves data preprocessing of the power system attack dataset which including missing values, outlier values, and data types to guarantee data integrity and uniformity. Moreover, the model utilizes the SMOTE algorithm to address class imbalance in the dataset, enhancing its sensitivity to attacks from underrepresented classes. After preprocessing, the model constructs a homogenous graph that fuses the smart grid’s topological structure with network and physical data, laying a comprehensive foundation for feature extraction. The graph serves as input to the Graph Attention Network (GAT), which performs a global extraction of node features to deepen the understanding of intricate network interactions. Finally, the GraphKAN model employs the Kolmogorov–Arnold Network (KAN) for classification, accurately identifying diverse types of intrusion attacks and their subtypes, thus substantially advancing the security framework of smart grids.

Flowchart of proposed GraphKAN model. GraphKAN integrates a graph attention network (GAT) with a Kolmogorov–Arnold network (KAN), while the GAT is introduced to capture the importance among nodes in a graph structure then extracts global features, and the KAN is integrated to learn the activation function and improve the nonlinear representation ability.

Data preprocessing

Given the complexity and heterogeneity of the data, it is essential to preprocess the dataset to ensure data quality and minimize the influence of noise on model training and prediction accuracy. The data preprocessing steps include data type conversion, missing value handling, outlier correction, data balancing, and normalization. These steps are described in detail as follows:

Data Type Conversion: The initial step involves converting raw data from ARFF format to a structured format. Subsequently, non-numerical features are transformed into numerical values to maintain consistency in subsequent processing.

Missing Value Processing: Two strategies are implemented for managing missing values. Samples with missing values constituting less than 5% are eliminated, while those exceeding this threshold are treated using spline interpolation to retain as much data as possible.

Outlier Processing: Outliers within each feature are identified using the Interquartile Range (IQR) method. Outliers comprising less than 5% of the data are removed directly; for those exceeding 5%, spline interpolation is employed to adjust values and mitigate potential impacts on model performance.

Data Augmentation: To tackle class imbalance within the dataset, the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) is utilized. This process involves identifying minority class samples, calculating the five nearest neighbors for each in the feature space, and generating synthetic samples through random interpolation between the sample and its neighbors. This method increases the minority class samples to equalize them with the majority class, thus providing a balanced dataset for model training.

Normalization: We implement min-max normalization to reduce the scale differences among features.

Homogeneous graph construction

We construct a homogeneous graph using preprocessed data based on the framework of the power system, as shown in Fig. 2. In this graph, G1 and G2 represent generators, BR1 through BR4 denote breakers, and R1 through R4 are relays to trip circuit breakers upon detecting equipment faults. Additionally, the graph incorporates elements from the control panel, system logs, and intrusion detection system.

We employ the framework of smart grids to select critical components as nodes in the graph neural network. Physical connections and logical dependencies among infrastructure elements serve as edges in the graph. Network information and physical data are used to assign corresponding feature vectors to each node. The specific implementation steps are as follows:

Graph Construction: As illustrated in Fig. 3, We define 11 elements as nodes from the framework of the power system, which have corresponding values in the dataset. Additionally, since the switch is a crucial part of the power system, we define a switch as an extra node. We treat the above 12 elements as nodes in the homogeneous graph.

The edges linked nodes present the relationship between elements in Fig. 2. Furthermore, the edges demonstrate following types of relationships:

Breakers (BR1 to BR4): Nodes 0, 1, 2, and 3 represent breakers. Each breaker is directly connected to a relay, indicating a control relationship where the relays (R1 to R4) are responsible for tripping the breakers upon detecting faults.

Relays (R1 to R4): Nodes 4, 5, 6, and 7 represent relays. These relays are connected to the breakers they control and also to the switch, suggesting that the relays can communicate or send signals to the switch.

Switch: Node 8 represents the switch, which is centrally connected to all relays (R1 to R4) and also to the control panel, system logs, and the intrusion detection system (Snort). This central position indicates the switch’s role in managing data flow and coordination between different components of the system.

Control Panel: Node 9 represents the control panel, which is connected to the switch and also to the system logs and the intrusion detection system (Snort). This connection implies that the control panel can receive data from the switch and is involved in the monitoring and management of the system.

System Logs (Syslog): Node 10 represents the system logs, which are connected to the control panel and the intrusion detection system (Snort). This connection suggests that system logs are used for recording events and are accessible to the control panel and the intrusion detection system for analysis.

Intrusion Detection System (Snort): Node 11 represents the intrusion detection system, which is connected to the control panel and the system logs. This connection indicates that the intrusion detection system works in conjunction with the control panel and has access to system logs for detecting and responding to security threats. The edges in the graph are represented by solid and dashed lines, which may indicate different types of relationships or communication paths between the nodes. The solid lines could represent direct control or data flow, while the dashed lines might indicate indirect or less direct interactions.

Feature Assignment: In the context of the graph depicted, the feature assignment process is integral to the functioning of the intrusion detection system (IDS) within the smart grid framework. The features are assigned to each node based on the data description provided in the Dataset Section, ensuring a comprehensive representation of the system’s components and their interactions.

Breakers (BR1 to BR4): Nodes 0 to 3 are assigned features from four Phasor Measurement Units (PMUs), which are critical for monitoring the electrical characteristics of the grid. These features are essential for the IDS to detect anomalies in the breaker’s operation.

Relays (R1 to R4): Nodes 4 to 7 are allocated ’relay#_log’ features, which likely contain logs or data specific to each relay’s operation. This data is crucial for the IDS to identify patterns or deviations that may indicate a security threat.

Switch: Node 8, representing the switch, is temporarily assigned zero values as placeholders for features due to the absence of specific switch data. This ensures the switch is included in the graph structure without compromising the uniformity of the feature set across nodes.

Control Panel, System Logs (Syslog), and Intrusion Detection System (Snort): Nodes 9 to 11 are distributed features from the control panel, system logs, and the intrusion detection system, respectively. These features are vital for the IDS to monitor and analyze the control panel’s operations, system events, and security alerts.

The number of features for each node is standardized to 29, with nodes having fewer features being padded with zeros to maintain consistency. This uniform feature assignment is crucial for the graph neural network’s effectiveness in processing and learning from the data, as it allows for a structured and comprehensive analysis of the smart grid’s operations and potential security threats.

Graph attention network for feature extraction

To efficiently extract features of complex dependencies between nodes in the smart grid, this paper designs a two-layer Graph Attention Network (GAT) based on a multi-head attention mechanism (As shown in Fig. 4). The model first receives a 29-dimensional input feature for each node, which includes physical quantities such as voltage and current, as well as system log information. In the first feature extraction layer, the model deploys three parallel attention heads. Each head transforms the input features into a 16-dimensional feature space and calculates attention coefficients to evaluate the importance between nodes. Through feature concatenation, the first layer generates a 48-dimensional (16×3) node representation, effectively capturing interaction patterns from different perspectives.The second layer also employs a 3-head attention mechanism to process the 48-dimensional node features from the first layer, with each attention head outputting a 32-dimensional feature representation. This layer evaluates the importance of nodes relative to their neighbors and uses attention coefficients to perform weighted aggregation of neighboring features, highlighting critical device connection features while suppressing redundant information. The outputs of the three attention heads are concatenated to form a 96-dimensional (32×3) node representation, which is then aggregated into a graph-level representation using global addition pooling. The hierarchical design enables the model to achieve feature learning from local to global levels: the first layer’s multi-head attention captures direct interaction features between devices, while the second layer extracts network-level topological dependencies through feature aggregation with a larger receptive field. The resulting 96-dimensional feature vector integrates both local interaction and global topology information, providing a complete feature representation for the KAN classifier.

Based on the above network architecture, we will now provide a detailed theoretical explanation of the feature extraction mechanism in GraphKAN. Firstly, we take the graph structure \(G=(V,E)\) as input, where \(V=\{V_i^1\}_{i=1}^{n}\) and \(E=\{E_{ij}\}_{i=1,j=1}^{n}\), and \(V_i^1\) is a group of feature vectors which denote the ith component of smart grids, \(E_{ij}=1\) if \(V_i^1\) and \(V_j^1\) have a physical or communicating connection and otherwise \(E_{ij}=0\). The input graph structure preserves the complex topology of the power grid, enabling the model to effectively capture dependencies among devices, which is crucial for intrusion detection. Many potential attacks in power grids, such as remote tripping command injection, rely on interactions between adjacent nodes. Supported by this graph structure, the model can analyze inter-node relationships at the topological level, thereby identifying network structure-dependent anomalies and enhancing the detection capability for topology-based attack patterns.

Afterward, a multi-head attention mechanism is employed to calculate the ith node of the second layer in GNN (Namely, \(V_i^2\)) by fusing related features from all nodes of the first layer of GNN, which is formalized as follows:

Subsequently, a graph attention network (GAT) is further utilized to map \(\{V_i^2\}_{i=1}^{n}\) to a feature vector \(V^{GAT}\), which is described as follows:

where \(\oplus\), \(W^t\) and \(\Theta\) represent a concatenation operation, the weight matrix of the tth attention head and a single-layer feed-forward neural network, respectively. \(t=1,2,\dots ,k\) and k means the total number of heads in GAT.

where \({\mathcal {N}}_i\) denotes the neighbor of the ith node.

where \(\sigma\) represents a non-linear activation function and \(g^t\) is the feature representation computed by the tth attention head.

By Eq. (5), we can obtain the training set of classification, namely \(G=\{G_i\}_{i=1}^{n_{cls}}\).

Kolmogorov–Arnold network for intrusion detection

To enhance the model’s ability to express the nonlinear characteristics of complex attack patterns, this paper introduces a Kolmogorov–Arnold Network (KAN) with learnable activation functions in the threat detection stage (as shown in Fig. 5). The network architecture consists of two hidden layers: the first layer contains 64 neurons, and the second layer contains 32 neurons. Each layer is connected through parameterized B-spline functions as learnable activation functions, with summation operations used for feature aggregation at each neuron. At the input layer of KAN, the network receives a 96-dimensional graph-level feature vector extracted by the GAT. The first layer processes the input features through 64 parallel neurons, each adopting a dual-branch structure comprising a basis function branch and a spline branch. The basis function branch performs feature transformation using standard basis functions, while the spline branch applies learnable B-spline functions to process the features. The outputs of these two branches are adaptively fused using learnable weight coefficients, allowing the model to dynamically adjust the importance of each branch based on the input features. The second layer retains the same dual-branch structure, using 32 neurons to further extract nonlinear feature representations. The output of each neuron undergoes a nonlinear transformation through a parameterized B-spline function, enhancing the model’s capacity to express complex feature patterns. In the final classification layer, the model selects an appropriate loss function based on the task type: cross-entropy loss for multi-class classification tasks and binary cross-entropy loss for binary classification tasks. This hierarchical architecture design, based on learnable activation functions, enables the model to adaptively capture the nonlinear relationships in different types of attack patterns, offering superior feature representation capabilities compared to traditional methods with fixed activation functions. Furthermore, the parameterized design of KAN allows the model to dynamically adjust the shape of the activation functions based on training data, further improving the accuracy of threat detection.

Given the training set \(G=\{G_i\}_{i=1}^{n_{cls}}\), we put the ith instance \(G_i\) into KAN, the tth output of the first layer is calculated by the following equation:

where \(G_t^1\) is the tth output of the first layer of KAN, and \(d_{G_i}\) is the dimension of the instance \(G_i\). \(\{W_{t1}^1, W_{t2}^1, \cdot \cdot \cdot , W_{td_{G_i}}^1 \}_{t=1}^{64}\) are the parameters of the first layer of KAN. \(G_{ij}\) is the jth component of \(G_i\). Therein, \(W_{tj}^1\) is defined as follows:

where \(w_b\) and \(w_s\) represent the weights of the basic function \(b(G_{ij})\) [as shown in Eq. (8)] and the spline function \({spline}(G_{ij})\) (As shown in Eq. 9), respectively.

where \(B_v(G_{ij})\) denotes the vth basic functions of B-spline. The coefficients \(c_v\) represents the vth learnable control points to adjust the shape of each basic function, and M represents the total number of spline basic functions. The explicit formulation of B-spline basic functions are given by Eqs. (10)–(11):

For zero-degree B-splines (\(r=1\)), the basis functions are defined as:

For higher-degree B-splines (\(r>1\)), the basis functions are defined as:

where r denotes the degree of the B-spline function, \([\xi _v, \xi _{v+1}]\) denotes the range in which the vth B-spline basic function \(B_v(G_{ij})\) is active.

For the second layer of the KAN model, we follow the same computation method as in the first layer, with the only difference is that the second layer contains 32 nodes rather than 64. Thus, the output \(G_t^2\) in the second layer is calculated using the same weight formulation as in Eq. (7). Finally, we leverage the cross entropy loss function to classify the output layer.

For multi classification:

For binary classification:

where \({N_{class}}\) represents the total number of classes. \(y_{i,j}\) denotes the true label of the ith sample for class j, while \(p_{i,j}\) indicates the predicted probability of the ith sample for class j. Additionally, \(y_i\) refers to the true label of the ith sample, and \(p_i\) represents the predicted probability for the ith sample.

The specific execution details are elucidated in Algorithm 1.

Experiments and results

Datasets

The dataset employed in this paper is the Power System Attack Datasets developed by Mississippi State University and Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Figure 2 illustrates the framework of the power system, in which G1 and G2 represent generators, BR1 to BR4 denote breakers, R1 to R4 indicate relays, and L1 and L2 are transmission lines. Additionally, network monitoring devices such as the Snort intrusion detection system and Syslog are included in the system architecture.

To support a comprehensive analysis of intrusion detection, the Power System Attack Dataset is structured into 15 subsets, enabling both binary and multiclass classification tasks. The dataset comprises 128 features generated from four Phase Measurement Units (PMUs), a control panel, a Snort, and a System logs. As shown in Table 1, each PMU contributes 29 features, accounting for 116 of the measurement features. Following the 116 PMU features, 12 supplementary features are collected by the network monitoring devices, as detailed in Table 2.

Evaluation metrics

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the Intrusion Detection System (IDS), we employed standard metrics including accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, and False Negative Rate (FNR) as specified in Eqs. (14), (15), (16), (17), and (18). The system identifies normal and attack events accurately using true positives (TP) and true negatives (TN), while false positives (FP) and false negatives (FN) indicate misclassifications.

Accuracy directly reflects the accuracy of the IDS in all types of events. Precision assesses the proportion of actual attacks among events flagged as attacks, which is crucial to reducing false alarms and enhancing operational efficiency. Recall measures the percentage of actual attacks that the IDS correctly identifies, focusing on minimizing missed threats to ensure comprehensive security coverage. The FNR quantifies the proportion of actual attacks that the IDS fails to detect, highlighting the importance of minimizing undetected threats to maintain robust security.The F1 score provides a balanced measure between precision and recall, serving as a key indicator of overall system performance. The accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score not only deepen understanding of IDS capabilities but also support security analysts and system administrators in optimizing detection strategies, thereby enhancing network security defenses.

Hyperparameter setting

The experiments conducted in this paper utilized the following hardware and software environment (Table 3).

In this environment, the datasets are divided into training, validation, and test sets with a ratio of 6:2:2. During parameter optimization, we focused on core parameters, including the number of attention heads in the GAT module and key parameters in the KAN module such as Grid Size, Spline Order, Scale Noise, and Grid Epsilon. Figure 6 illustrates in detail the impact of these parameters on classification accuracy for binary, ternary, and 37-class tasks. Through systematic parameter sensitivity analysis, we found that when the number of attention heads fluctuated within the range of 1–6, the model’s classification accuracy remained relatively stable; when the initial learning rate was set to 0.005, the model achieved optimal classification performance, while higher or lower learning rates led to significant decreases in classification accuracy; the model demonstrated the best classification performance with Grid Size of 5 and Spline Order of 4; when Scale Noise parameter was set to 0.1 and Grid Epsilon to 0.2, the model maintained high classification accuracy across all classification tasks.

Based on the results of the above parameter sensitivity analysis, we determined the optimal parameter configuration for the GraphKAN model (As shown in Table 4). Specifically, the GAT module employs 3 attention heads for graph feature extraction, utilizes feature concatenation mechanism to enhance feature representation, and sets dropout rates of 0.1 and 0.2 in the first and second hidden layers, respectively. The KAN module uses 4th-order B-splines to construct approximation functions, with Scale Noise parameter set to 0.1, Grid Epsilon to 0.2, and Grid Range controlled within \([-1,1]\). For model training, we employed the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.005, and adopted a StepLR learning rate scheduler with step size of 100 and decay rate of 0.9, while setting the batch size to 256, using cross-entropy as the loss function, and training for 2000 epochs.

Experimental result and analysis

In the following sections, we evaluate results of our proposed GraphKAN model by conducting ablation and comparative experiments in binary, ternary, and 37-class classification tasks. Specifically, to assess the individual contributions of each module from the GraphKAN framework for intrusion detection, we establish the baseline models, which including GCN-FC (Graph Convolutional Network + Fully Connected Layer)40, GAT-FC (Graph Attention Network + Fully Connected Layer)41, and MLP-KAN (Multilayer Perceptron + Kolmogorov–Arnold Network). Moreover, we review intrusion detection studies on the same dataset from recent years, including BGWO-EC42, RF-RBM43, Net_Stack44, and SVM-AC45. Finally, we analyze and compare the detection times for binary, ternary, and 37-class classifications.

Binary attack classification

Figure 7 presents the binary classification accuracy curves of four different models in the ablation study on the data subset 8. All models experienced a rapid accuracy improvement phase during the initial training period (The first 250 epochs). However, there are significant differences in convergence speed and final accuracy levels among the models. The GraphKAN model exhibited a faster convergence rate throughout the training process and ultimately achieved the highest accuracy level. After approximately 500 epochs, the accuracy of the GraphKAN model stabilized above 0.96, significantly outperforming the other models. This highlights the GraphKAN model’s ability to capture complex data features. In comparison, the GAT-FC and KAN-MLP models also demonstrated high accuracy but showed greater fluctuations during training and achieved slightly lower final accuracies than GraphKAN. The GCN-FC model had a slower initial accuracy improvement and did not reach the final accuracy level of GraphKAN. Additionally, the GraphKAN model showed better stability during training, with smoother accuracy curves and no large fluctuations. This indicates that the GraphKAN model has good generalization ability and can stably learn the data features.

To further comprehensively evaluate the contribution of each module, Table 5 presents the binary classification accuracies of four models-GCN-FC, GAT-FC, KAN-MLP, and GraphKAN-across 15 different data subsets. The GraphKAN model demonstrates superior performance on most data subsets. Its accuracy is no lower than 95% across all subsets and exceeds 98% on subsets 3, 7, 8, and 11. Notably, it achieves an accuracy of 99.30% on subset 8. In comparison, the GAT-FC and KAN-MLP models perform slightly worse on certain subsets. Additionally, the GCN-FC model does not match the performance of GraphKAN on multiple subsets, particularly showing a significantly lower accuracy on subset 9.

Table 6 represents the result of model comparison on binary classification task. GraphKAN demonstrated advantages across four performance metrics, highlighting GraphKAN’s high accuracy in binary classification tasks and its potential for practical applications. In comparison, the RF-RBM model had a slightly lower F1 score of 97.90%. The BGWO-EC model also showed somewhat inferior performance, with precision and recall values of 96.77% and 94.26%, respectively. Traditional machine learning models such as SVM-AC and PSO-SVM lagged significantly behind, with accuracies of 84.40% and 89.50%, respectively. Furthermore, the GA-RBF-SVM model showed improvements in precision and recall, but its F1 score was 87.00%, still below that of GraphKAN. Overall, GraphKAN’s superior performance across all metrics underscores its exceptional effectiveness in binary classification tasks.

Ternary attack classification

Figure 8 illustrates the validation accuracy curves of four models (GraphKAN, GCN-FC, GAT-FC, and MLP-KAN) on the ternary classification task for Subset 8, providing insights into the ablation study results. The GraphKAN model demonstrates superiority in terms of both final accuracy and stability, showcasing its outstanding performance. The final accuracy of GraphKAN is close to 0.98, significantly higher than that of GCN-FC (approximately 0.95) and GAT-FC (approximately 0.96), and surpassing that of MLP-KAN (approximately 0.97). These results indicate that GraphKAN, by effectively combining the global properties of graph structures with the flexibility of attention mechanisms, is capable of comprehensively capturing the structural information in the data, thereby enhancing classification performance. In contrast, GCN-FC and GAT-FC, while capable of modeling graph structures to some extent, are constrained by their fixed network designs, making it difficult for them to fully extract global information. Similarly, MLP-KAN achieves a certain degree of performance improvement through the incorporation of the KAN mechanism, but its lack of explicit modeling of graph structural information limits its final accuracy, which remains slightly below that of GraphKAN.

Table 7 presents the ternary classification accuracy of GCN-FC, GAT-FC, KAN-MLP, and GraphKAN across 15 data subsets. GraphKAN achieves the highest accuracy on all subsets, demonstrating remarkable stability and further validating the superiority of its design. Specifically, GraphKAN maintains an accuracy consistently above 98%, approaching 99% on several subsets, showcasing its outstanding performance. KAN-MLP ranks second, with its performance close to GraphKAN on some subsets (e.g., subsets 7 and 10), but overall remains slightly inferior. GAT-FC shows decent performance on certain subsets but lags significantly behind GraphKAN and KAN-MLP in overall accuracy. GCN-FC performs the worst, with accuracy below 97% on most subsets, highlighting its limitations in modeling complex graph structures.

Table 8 compares the performance of GraphKAN with other models on the ternary classification task. The results indicate that GraphKAN outperforms all other models across all metrics, demonstrating its superior performance in the ternary classification task. GraphKAN achieves an accuracy of 98.66%, significantly higher than BGWO-EC (97.77%) and RF-RBM (94.30%), and far surpasses traditional machine learning models such as SVM-ACO (78%) and PSO-SVM (85.7%). Net_Stack achieves an accuracy of 97.45%, close to BGWO-EC, but still falls short of GraphKAN. In terms of precision and recall, GraphKAN reaches 98.63% and 99.21%, respectively, excelling in both identifying and capturing positive class samples. These results are clearly superior to those of BGWO-EC (97.39%, 95.24%) and RF-RBM (93.10%, 92.15%). For the F1 score, GraphKAN also leads with 98.63%, further highlighting its significant performance advantage. Traditional machine learning models (e.g., SVM-ACO and PSO-SVM) perform worse than both GraphKAN and other deep learning models across all metrics, reflecting their limited ability to extract complex features. While some traditional models utilize optimization algorithms (e.g., GA, ACO, PSO) to improve performance, they still exhibit clear limitations when dealing with multi-class classification tasks.

37-Class attack classification

Figure 9 illustrates the 37-class validation accuracy curves of GraphKAN, GCN-FC, GAT-FC, and MLP-KAN on Subset 8. Compared to the ternary classification task, the 37-class task significantly increases complexity, providing a more comprehensive evaluation of each model’s feature learning capability. The results show that GraphKAN consistently outperforms all other models throughout the training process, achieving a final validation accuracy close to 1.0, significantly higher than its counterparts. This highlights GraphKAN’s superior feature representation and global modeling capability in handling complex multi-class tasks. GCN-FC performs the weakest, with a final accuracy of only around 0.9, indicating its limited ability to extract complex features and adapt to the demands of multi-class classification. GAT-FC demonstrates moderate improvement, achieving a final accuracy of approximately 0.95, reflecting the benefits of attention mechanisms for capturing local features. However, its integration of global information remains insufficient. MLP-KAN performs better than GAT-FC but falls short of GraphKAN, with a final accuracy of around 0.96. While the KAN mechanism enhances feature learning to some extent, the lack of explicit modeling of graph structure limits further performance improvement.

Table 9 presents the 37-class accuracy of GraphKAN, GCN-FC, GAT-FC, and KAN-MLP across 15 data subsets. The results demonstrate that GraphKAN consistently achieves the highest accuracy across all subsets, showcasing remarkable stability and outstanding performance in complex classification tasks. Specifically, GraphKAN maintains an accuracy above 98% across all subsets, with subsets 7 and 15 achieving nearly 99.5%, indicating its strong adaptability to diverse data distributions and complex feature representations. In comparison, KAN-MLP achieves accuracy close to 98% on most subsets but exhibits slight fluctuations on subsets 5 and 10. This suggests that while the KAN mechanism contributes to improved performance, its lack of explicit modeling for graph structural information limits its classification capability on more complex data distributions. GAT-FC achieves an accuracy range of 96%-98%, outperforming GCN-FC, which highlights the enhancement brought by the attention mechanism for capturing local features. However, in more complex subsets such as subsets 6 and 12, GAT-FC’s accuracy is significantly lower than GraphKAN, indicating insufficient global information integration. GCN-FC shows the weakest performance, with accuracy below 97% on most subsets. Its limitations are particularly evident on subsets 1 and 7, which involve more complex data distributions, demonstrating its inadequacy in modeling high-dimensional features for multi-class tasks. From the perspective of subset characteristics, subsets 5, 7, and 12 serve as good indicators of performance differences between models. On these complex data distributions, GraphKAN consistently achieves the best results, validating its superior capability in feature extraction and handling complex classification tasks. For subsets with simpler data distributions (e.g., subsets 3 and 9), KAN-MLP and GAT-FC achieve performance closer to GraphKAN, though a noticeable gap still exists, further emphasizing GraphKAN’s advantage in complex scenarios.

Table 10 presents the performance of GraphKAN and other comparison models on the 37-class classification task. GraphKAN achieves an accuracy of 99.04%, surpassing all other models by a significant margin. Its precision (98.99%), recall (99.57%), and F1-score (99.00%) reflect exceptional classification capabilities, ensuring both accurate recognition of positive samples and a strong balance between classes, highlighting GraphKAN’s superior feature extraction and global modeling effectiveness. Traditional models, such as Net_Stack (95.52%) and RF-RBM (94.30%), perform reasonably well but struggle to match the performance of GraphKAN in handling the complexities of multi-class tasks. While DDPM-LGBM achieves an accuracy of 94.44%, its precision (92.49%), recall (92.46%), and F1-score (92.47%) are considerably lower than GraphKAN. Deep learning-based models, such as DenseNet-BC (90.79%) and Conv1D (85.27%), exhibit significant shortcomings in capturing the global patterns required for high-dimensional classification tasks. Conv1D demonstrates particularly suboptimal results, with all metrics below 84%, revealing its inability to adapt to the dataset’s complexity. Similarly, KNN (81.81%) and RNN (86.79%) display weak performance, further emphasizing the inadequacy of traditional algorithms and simpler neural network architectures for addressing complex classification challenges.

Detection time analysis

In this paper, we focus on the performance of proposed GraphKAN model in 37-class intrusion detection task. To thoroughly assess the capabilities of proposed model, we compared its detection time against several other models, as detailed in Table 11. The results indicate that the GraphKAN model recorded a detection time of 124.5 ms. Although not the shortest among the models evaluated, GraphKAN’s performance remains commendable, particularly when contrasted with the KNN (130.4 ms) and RNN (140.2 ms) models, where it demonstrated a clear advantage in terms of efficiency and processing velocity. By integrating the Graph Attention Network (GAT) and the Kolmogorov–Arnold Network (KAN), GraphKAN significantly enhances its ability to detect complex attack patterns and manage diverse classification tasks. Despite this architectural complexity marginally increasing detection times, it substantially improves the precision in detecting intricate attack behaviors, especially in scenarios that demand the precise identification of multiple intrusion types, where its performance is particularly pronounced.

Conclusion and future work

This paper proposed a Graph Attention and Kolmogorov–Arnold network for intrusion detection in smart grids(GraphKAN), aiming to further enhance the accuracy of intrusion detection in smart grids. The proposed method innovatively utilizes the power grid topology to construct graph data, integrating network information and physical data in smart grids. Through the multi-head attention mechanism of the GAT module, dynamic allocation of node weights is achieved, effectively extracting global interaction features between devices. Additionally, the introduction of KAN’s learnable activation functions significantly enhances the model’s ability to express complex attack patterns, enabling more precise detection of abnormal behaviors. Experiments conducted on the MSU-ORNL dataset demonstrated that the proposed method achieved detection accuracies of 97.63%, 98.66%, and 99.04% for binary classification, three-class classification, and 37-class classification tasks, respectively, showcasing excellent classification performance.

To further improve the model’s applicability in real-world scenarios, future work will explore optimization techniques such as network pruning and knowledge distillation to enhance the scalability of GraphKAN in large-scale smart grid systems. By optimizing the model architecture and parameter configurations, we aim to reduce computational complexity and memory overhead while maintaining detection accuracy, enabling efficient deployment of the model in resource-constrained environments.

Data availability

The dataset used in this paper is the publicly available Power System Attack Dataset, which can be accessed via the following link: https://sites.google.com/a/uah.edu/tommy-morris-uah/ics-data-sets.

References

Wu, Y., Dai, H.-N. & Wang, H. Convergence of blockchain and edge computing for secure and scalable iiot critical infrastructures in industry 4.0. IEEE Internet Things J. 8, 2300–2317 (2020).

Sullivan, J. E. & Kamensky, D. How cyber-attacks in Ukraine show the vulnerability of the us power grid. Electric. J. 30, 30–35 (2017).

Guillén, A. Physical Attacks on Power Grid Surge to New Peak. https://www.politico.com/news/2022/12/26/physical-attacks-electrical-grid-peak-00075216 (2023).

Alrumaih, T. N. & Alenazi, M. J. Cgaad: Centrality-and graph-aware deep learning model for detecting cyberattacks targeting industrial control systems in critical infrastructure. IEEE Internet Things J. (2024).

da Silva Ruffo, V. G. et al. Anomaly and intrusion detection using deep learning for software-defined networks: A survey. Expert Syst. Appl. 124982 (2024).

De Sousa, M. S., Veiga, C. E. L., Albuquerque, R. D. O. & Giozza, W. F. Information gain applied to reduce model-building time in decision-tree-based intrusion detection system. In 2022 17th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI) 1–6 (IEEE, 2022).

Angelin, J. A. B. & Priyadharsini, C. Deep learning based network based intrusion detection system in industrial internet of things. In 2024 2nd International Conference on Intelligent Data Communication Technologies and Internet of Things (IDCIoT) 426–432 (IEEE, 2024).

Gharehchopogh, F. S., Abdollahzadeh, B., Barshandeh, S. & Arasteh, B. A multi-objective mutation-based dynamic Harris hawks optimization for botnet detection in iot. Internet Things 24, 100952 (2023).

Qi, H., Liu, X., Gani, A. & Gong, C. Quantum particle swarm optimized extreme learning machine for intrusion detection. J. Supercomput. 66, 1–23 (2024).

Wang, L.-H., Dai, Q., Du, T. & Chen, L.-F. Lightweight intrusion detection model based on cnn and knowledge distillation. Appl. Soft Comput. 165, 112118 (2024).

Elsersy, W. F., Samy, M. & ElShamy, A. Network intrusion detection using deep belief network (dbn). In 2024 Intelligent Methods, Systems, and Applications (IMSA) 193–198 (IEEE, 2024).

Imrana, Y. et al. Cnn-gru-ff: A double-layer feature fusion-based network intrusion detection system using convolutional neural network and gated recurrent units. Complex Intell. Syst. 66, 1–18 (2024).

Deng, X. et al. Flow topology-based graph convolutional network for intrusion detection in label-limited iot networks. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 20, 684–696 (2022).

Haixiao, Z., Mengshuai, M., Bin, W., Zhaowu, Z. & Wenlong, L. Network intrusion anomaly detection with gatv2. Front. Data Comput. 6, 179–190 (2024).

Duan, G., Lv, H., Wang, H. & Feng, G. Application of a dynamic line graph neural network for intrusion detection with semisupervised learning. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 18, 699–714 (2022).

Abinesh, R., VG, Y., TJ, S. & Nandhini, S. Deep graph convolution neural network based intrusion detection system towards early detection of malicious attacks. In 2024 8th International Conference on I-SMAC (IoT in Social, Mobile, Analytics and Cloud)(I-SMAC) 549–554 (IEEE, 2024).

Kisanger, P. Network Anomaly Detection Scheme Using Graph Neural Network. Ph.D. thesis, Toronto Metropolitan University.

Tran, D.-H. & Park, M. Fn-gnn: A novel graph embedding approach for enhancing graph neural networks in network intrusion detection systems. Appl. Sci. 14, 6932 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Zhang, X., Ji, X., Han, X. & Yang, M. Optimization of integrated energy system considering transmission and distribution network interconnection and energy transmission dynamic characteristics. Int. J. Electric. Power Energy Syst. 153, 109357 (2023).

Abdelkader, S. et al. Securing modern power systems: Implementing comprehensive strategies to enhance resilience and reliability against cyber-attacks. Results Eng. 66, 102647 (2024).

Liu, G., Sun, H. & Zhong, G. A smart grid intrusion detection system based on optimization. In 2021 3rd International Conference on Smart Power & Internet Energy Systems (SPIES) 284–290 (IEEE, 2021).

Chatzimiltis, S., Shojafar, M., Mashhadi, M. B. & Tafazolli, R. A collaborative software defined network-based smart grid intrusion detection system. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. (2024).

Hu, C., Yan, J. & Liu, X. Reinforcement learning-based adaptive feature boosting for smart grid intrusion detection. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 14, 3150–3163 (2022).

Shi, J., Liu, S., Chen, B. & Yu, L. Distributed data-driven intrusion detection for sparse stealthy fdi attacks in smart grids. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II: Express Briefs 68, 993–997 (2020).

Gupta, P., Singh, N. & Mahajan, V. Intrusion detection in cyber-physical layer of smart grid using intelligent loop based artificial neural network technique. Int. J. Eng. 34, 1250–1256 (2021).

Kanna, P. R. & Santhi, P. Unified deep learning approach for efficient intrusion detection system using integrated spatial-temporal features. Knowl. Based Syst. 226, 107132 (2021).

Kanna, P. R. & Santhi, P. Hybrid intrusion detection using mapreduce based black widow optimized convolutional long short-term memory neural networks. Expert Syst. Appl. 194, 116545 (2022).

Kanna, P. R., Sindhanaiselvan, K. & Vijaymeena, M. A defensive mechanism based on pca to defend denial of-service attack. Int. J. Secur. Appl. 11, 71–82 (2017).

Saheed, Y. K., Abdulganiyu, O. H. & Tchakoucht, T. A. A novel hybrid ensemble learning for anomaly detection in industrial sensor networks and scada systems for smart city infrastructures. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 35, 101532 (2023).

Saheed, Y. K., Misra, S. & Chockalingam, S. Autoencoder via dcnn and lstm models for intrusion detection in industrial control systems of critical infrastructures. In 2023 IEEE/ACM 4th International Workshop on Engineering and Cybersecurity of Critical Systems (EnCyCriS) 9–16 (IEEE, 2023).

Abdulganiyu, O. H., Tchakoucht, T. A., Saheed, Y. K. & Ahmed, H. A. Xidintfl-vae: Xgboost-based intrusion detection of imbalance network traffic via class-wise focal loss variational autoencoder. J. Supercomput. 81, 1–38 (2025).

Muthubalaji, S. et al. An intelligent big data security framework based on aefs-kenn algorithms for the detection of cyber-attacks from smart grid systems. Big Data Min. Anal. 7, 399–418 (2024).

Diaba, S. Y. & Elmusrati, M. Proposed algorithm for smart grid ddos detection based on deep learning. Neural Netw. 159, 175–184 (2023).

Wang, Z., Zeng, Y., Liu, Y. & Li, D. Deep belief network integrating improved kernel-based extreme learning machine for network intrusion detection. IEEE Access 9, 16062–16091 (2021).

Saheed, Y. K. & Chukwuere, J. E. Xaiensembletl-iov: A new explainable artificial intelligence ensemble transfer learning for zero-day botnet attack detection in the internet of vehicles. Results Eng. 24, 103171 (2024).

Sweeten, J., Takiddin, A., Ismail, M., Refaat, S. S. & Atat, R. Cyber-physical gnn-based intrusion detection in smart power grids. In 2023 IEEE International Conference on Communications, Control, and Computing Technologies for Smart Grids (SmartGridComm) 1–6 (IEEE, 2023).

Wang, Y. et al. N-stgat: Spatio-temporal graph neural network based network intrusion detection for near-earth remote sensing. Remote Sens. 15, 3611 (2023).

Xu, R. et al. Applying self-supervised learning to network intrusion detection for network flows with graph neural network. Comput. Netw. 248, 110495 (2024).

Xia, W., He, D. & Yu, L. Locational detection of false data injection attacks in smart grids: A graph convolutional attention network approach. IEEE Internet Things J. (2023).

Fei, S. et al. A power grid topological error identification method based on knowledge graphs and graph convolutional networks. Electronics 13, 66 (2024).

Su, X. et al. Damgat based interpretable detection of false data injection attacks in smart grids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid (2024).

Panthi, M. & Das, T. K. Intelligent intrusion detection scheme for smart power-grid using optimized ensemble learning on selected features. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. Prot. 39, 100567 (2022).

Diaba, S. Y., Shafie-Khah, M. & Elmusrati, M. Cyber security in power systems using meta-heuristic and deep learning algorithms. IEEE Access 11, 18660–18672 (2023).

Wang, W., Harrou, F., Bouyeddou, B., Senouci, S.-M. & Sun, Y. A stacked deep learning approach to cyber-attacks detection in industrial systems: Application to power system and gas pipeline systems. Clust. Comput. 66, 1–18 (2022).

Choraś, M. & Pawlicki, M. Intrusion detection approach based on optimised artificial neural network. Neurocomputing 452, 705–715 (2021).

Kim, J., Kim, J., Kim, H., Shim, M. & Choi, E. Cnn-based network intrusion detection against denial-of-service attacks. Electronics 9, 916 (2020).

Alimi, O. A., Ouahada, K., Abu-Mahfouz, A. M. & Rimer, S. Power system events classification using genetic algorithm based feature weighting technique for support vector machine. Heliyon 7, 66 (2021).

Hink, R. C. B. et al. Machine learning for power system disturbance and cyber-attack discrimination. In 2014 7th International Symposium on Resilient Control Systems (ISRCS) 1–8 (IEEE, 2014).

Li, X. et al. Rolling element bearing fault detection using support vector machine with improved ant colony optimization. Measurement 46, 2726–2734 (2013).

Huang, C.-L. & Dun, J.-F. A distributed pso-svm hybrid system with feature selection and parameter optimization. Appl. Soft Comput. 8, 1381–1391 (2008).

Funding

This research was funded by Chongqing Talent Plan (No. CQYC20200309237) and Chongqing Industrial Internet Intrinsic Security Key Technology Research and Collaborative Innovation Project (HZ2021015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W conceived and designed the study. Y.Z.Z conducted the experiments and drafted the initial manuscript. X.T.Z and W.T.L reviewed and revised the manuscript. N.B provided additional data and resources. Y.X and WW.L assisted in data interpretation. W.D supervised the project and offered critical insights.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, Y., Zang, Z., Zou, X. et al. Graph attention and Kolmogorov–Arnold network based smart grids intrusion detection. Sci Rep 15, 8648 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88054-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88054-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Resilient cybersecurity in smart grid ICS communication using BLAKE3-driven dynamic key rotation and intrusion detection

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Quantum-inspired adaptive mutation operator enabled PSO (QAMO-PSO) for parallel optimization and tailoring parameters of Kolmogorov–Arnold network

The Journal of Supercomputing (2025)