Abstract

Agriculture significantly impacts the global environment, contributing to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, air and water pollution, and biodiversity loss. As the global population grows and demands higher agricultural output, these environmental impacts are expected to intensify. Among global contributors, China, with its vast population and prominent agricultural sector, plays a leading role in GHG emissions. Understanding and mitigating these impacts in China is crucial for addressing broader global environmental challenges. To address these key issues, we conducted a study on the dynamic impact of agricultural key variables (agricultural land, fertilizer consumption, energy use for agriculture, agricultural value-added, forest land, livestock, fisheries, and crop production) on GHG emissions by utilizing the data from 1990 to 2020, and employed linear and non-linear linear autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL and NARDL) models. In the study, co-integration analysis confirms the long-run relationship between variables, and the long-term findings from the ARDL model reveal important insights, increased agricultural land use, fertilizer consumption, agricultural energy use, crop production, livestock production, and fishery production increases GHG emissions in China and GHG emissions can be reduced by increasing forest land in the long term. Furthermore, with the asymmetric NARDL regression applied to three key variables, the positive shock analysis results confirm that agricultural land use (AGL+), fertilizer consumption (FC+), and agricultural energy use (EUA+) can significantly contribute to long-term GHG emissions. However, adverse shocks to (AGL−), (FC−), and (EUA−) could significantly compress GHG emissions. These findings offer valuable implications for Chinese authorities’ focus on expanding forest land, using more renewable energy, and minimizing the usage of chemicals in agriculture. These measures can help to mitigate emissions while promoting sustainable agricultural practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

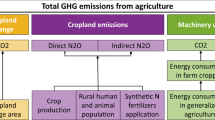

Agriculture continues to be the most susceptible sector to climate change globally as greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the agriculture sector significantly contribute to global warming, posing challenges to human survival and exacerbating food insecurity in both developed and developing countries1,2. The GHG emissions from agriculture pose severe difficulties for environmental degradation and create consequences for economies. Additionally, these GHG emissions contribute to climate change, reduce agricultural productivity, and disrupt food supply chains, especially in areas where agriculture is already vulnerable to such fluctuations3,4,5. In the agriculture sector, the principal sources of GHG emissions are nitrous oxide (N2O), methane (CH4), and carbon dioxide (CO2). The kind of N2O emissions predominantly arise from using nitrogen-based fertilizers, whereas CH4 is primarily emitted from intestinal fermentation in ruminant animals, including cattle. Furthermore, CO2 emissions result from the utilization of fossil fuels in agricultural machinery and transportation which are used for road and shipping agriculture products6. Agriculture contributes about 17% of the nation’s total GHG emissions in China. Notably, in 2020, the country’s overall GHG emissions were estimated at 12.3 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent (GtCO2e), representing 27% of global emissions7.

Although the endeavors by international organizations to alleviate environmental repercussions and formulate different kinds of policies and strategies to diminish CO2 and GHG emissions from global as energy and agriculture-related emissions surged by 53.7 in the last three decades and reached 31.5 gigatons in the previous of 20228. In this manner, a few countries including China adopted policies in agriculture to reduce GHG emissions from the agriculture sector9,10. In addition, at the conference held by the United Nations in Paris, China is one of nearly 200 countries that agreed to the Paris agreement on climate change (PACC) to control global warming within 1.5 °C and maintain it below 2 °C. After the Paris Agreement, China implemented significant policy reforms across agriculture, energy production, industry, transportation, and urban planning to address environmental degradation and mitigate climate risks, ensuring the nation’s long-term prosperity and becoming carbon neutral nation by 2060 (WDI 202211 and12). Furthermore, China has significantly advanced its renewable energy infrastructure during the post-Paris Agreement era, especially in wind and solar power, achieving an installed renewable capacity of around 1380 GW by the close of 202213. This energy transition has enabled projects in provinces such as Zhejiang, where specific laws advocate for low-carbon agricultural practices, enhance fertilizer efficiency, and promote sustainable farming methods to reduce GHG emissions in agriculture14.

Furthermore, China is an emerging economy and one of the world’s largest emitters of GHG as shown in (Fig. 1), accounting for almost 31% of global emissions, with an average growth of 15% over the past few decades, China’s carbon emissions reached 10.56 billion tons in 2020 (WDI 202211). However, regarding methods to mitigate carbon emissions, energy ranks foremost, as the energy utilized in agriculture is directly associated with GHG emissions. Fossil fuels and electricity are important components of new agricultural production, directly used in power machinery and indirectly used to synthesize nitrogen compounds15. In addition, many agriculture activities including irrigation, transportation, and operating machinery require energy, which releases GHG emissions into the environment16. China’s agriculture industry is becoming more dependent on fossil fuel-based energy as energy consumption for agriculture is trending upward3,17. Initiatives to mitigate energy-related GHG emissions concentrate on shifting to renewable energy sources and improving energy efficiency. Adopting cleaner energy alternatives, including wind, solar, and hydropower, can significantly diminish emissions. Moreover, enhancing energy efficiency in structures and transportation helps in reducing total energy usage and emissions from agriculture18. Furthermore, China is reforming subsidies for energy usage such as irrigation, water use, pesticide production, and fertilizer production to support the country’s most impactful actions to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and promote green growth (Zhang et al.19, WDI11).

expresses the distribution of GHG emissions worldwide and specifically within China. (a) illustrates the eight leading nations’ GHG emissions in 2022. (b) illustrates global sectoral emissions, whereas (c) concentrates on agriculture emissions worldwide. (d) depicts the composition of China’s GHG emissions in 2018, while (e) emphasizes the distribution of GHG emissions from Chinese agriculture in 2022. The figure is based on authors’ calculations using data from different sources (the World Bank, OECD, and Statista data web).

While the shift to bio-energy mitigates a substantial fraction of emissions; nonetheless, agricultural practices, especially the application of chemical fertilizers, continue to be a significant source of GHG emissions20,21. The manufacturing, shipping, and applying fertilizers emit considerable quantities of N₂O22. Approximately 58.6% of GHG emissions from fertilizer (synthetic nitrogen fertilizer) originate from soil processes. Crops typically absorb only about half of the applied nitrogen fertilizer, while the remainder leaches into water systems or volatilizes into the atmosphere23. Mitigating these emissions from agriculture practices is important for actual climate action. Measures must be implemented to recognize and reduce fertilizer-related emissions within comprehensive climate policies. By employing modern fertilizer applications, agriculture may reduce emissions from agriculture without affecting productivity and food security16,24. Similarly, emissions from agricultural production contribute to climate issues18,25,26. Globally, over the past 2 decades, agricultural activities account for 10–14% of total global GHG emissions (FAOSTAT27). Despite this, In the last 40 years, China’s cultivated acreage has diminished from 117 million hectares to 116 million hectares, while grain production has risen from 321 to 664 million tons (NBS28). Overall, crop production substantially contributes to GHG emissions, mainly through land usage changes such as deforestation. To reduce GHG from field crops, different types of strategies will be adopted, including incorporating low carbon footprint crop types, modifying cropping techniques, and enhancing crop residue management within agricultural frameworks29,30.

Furthermore, we do not ignore the crucial role of livestock in agriculture which significantly contributes to GHG emissions31,32. However, the animals and poultry industry releases 710 million tons of emissions. Total global GHG of about 18% comes from livestock and their byproducts33. In the last two eras, global livestock consumption has enlarged sharply because of population growth and the luxury of life. Specifically, the consumption of meat has increased by 56.59%. It will increase livestock GHG emissions34. In China’s case, the demand for milk, meat, eggs, and other livestock-derived goods surged, positioning China as one of the top meat consumption markets globally. Thus, the significant enlargement of livestock highlights that it is one of the main pillars of GHG emission contributors from the agriculture sector35,36,37. Along with the livestock industry, the fisheries industry also contributes to GHG emissions38. The enlargement of the fish industry has been creating more global environmental issues, such as water pollution, Land use changes, eutrophication, and increased GHG emissions39,40. Moreover, Blanchard et al.41, suggested that to continue demand for aquatic products, it is essential to identify the strong association within and across the goals of aquaculture, fisheries, and GHG emissions.

Another main issue behind the expansion of GHG emissions worldwide is the increasing rate of deforestation. Forests cover 31% of the world’s land area (4.06 billion). Deforestation and forest degradation are the second largest contributors to emissions, after fossil fuels42. Degradation may result from illicit logging, land conversion for farming, and urban expansion, which release sequestered carbon into the atmosphere. China lost primary forest over 81,500 hectares, representing a 4.7% decline from 2001 to 202143. The deterioration of forests adversely affects GHG emissions, as compromised forests can release significant quantities of CO2, hindering sequestration initiatives. In order to reduce future GHG emissions, it will be essential to enhance forest protection measures, promote environmentally friendly practices, and ensure significant planting activities23,44,45,46.

Currently, many researchers focused on agricultural variables such as crop production, land expansion, fisheries, forestry, and animal husbandry, utilizing panel data and time series to estimate their trends and contributions to GHG emissions, global warming, and climate change46,47,48,49,50. Despite extensive studies on the determinants of GHG emissions in the agricultural sector, a considerable gap persists. Numerous investigations have neglected essential influencing components, neglecting to incorporate them into a cohesive framework. This exclusion constrains our comprehension of the intricate processes influencing agricultural emissions and hinders the formulation and execution of specific mitigation solutions. China, a leading agricultural country and a significant contributor to global GHG emissions, represents a crucial subject for examination. The extensive terrain and varied agricultural methods pose distinct problems and opportunities for customized mitigation techniques. A comprehensive assessment of agricultural GHG emissions in China is crucial for effectively tackling the interconnected challenges of agriculture, food security, and climate change.

Our study builds on this foundation by addressing critical gaps and providing fresh and deep insights into the interplay between agricultural land, fertilizer consumption, energy usage, forest and crop production, livestock, and fisheries, and their impact on GHG emissions from Chinese agriculture. This research is particularly relevant given the urgent need to understand and mitigate the agricultural sector’s role in climate change, making it a valuable contribution to the existing body of knowledge.

In the study, we used time series data from 1990 to 2020, which is essential for a comprehensive analysis of the impact of Chinese agricultural practices on GHG emissions. Furthermore, utilizing this dataset offers an extensive overview of trends and changes over three decades, facilitating a thorough examination of the relationship between agricultural practices and emissions levels. Researchers and policymakers can derive insights from historical trends, evaluate existing initiatives, and formulate future policies to reduce emissions effectively. The study utilized a sophisticated econometric model known as the non-linear autoregressive distributed lag (NARDL) cointegration technique. Most study efforts have predominantly investigated the linear correlations between agricultural indicators and environmental degradation. Thus, there is a significant lack of research examining the non-linear interactions that may exist between these agricultural parameters and ecological degradation.

Overall, this study differs from previous research in three distinct ways, and it has the potential to advance both literature and policymaking significantly. Firstly, this study represents a groundbreaking effort to shed light on the connection between agricultural components and GHG emissions. It is unique in its approach to examining the impact of farming factors on GHG emissions from China’s agriculture sector. In this study, we investigated the influence of several novel factors, previously unexplored in China’s agricultural industry, including the crop and fisheries production index, livestock production index, and fertilizer consumption. Secondly, we employ multiple unit root tests, NARDL tests, and diagnostic procedures to check the accuracy of our outcomes. Lastly, our findings will offer novel insights on benchmarking agricultural management, prioritizing mitigation strategies, and the role of agriculture in attaining overall GHG emissions objectives. This study elucidates the framework of food security and sustainability.

The subsequent sections of this work are organized as follows: Section “Review of relevant studies” examines the current literature on the subject, emphasizing significant discoveries and deficiencies. Section “Methodology” outlines the research methodology, detailing the data collection, analytical processes, and results discussion. Section “Conclusion and policy implications” concludes with a review of the results, elucidating their relevance in the context of prior research and their implications for future inquiry.

Review of relevant studies

In this literature review, we examine to clarify the many pathways through which agricultural activities contribute to GHG emissions and evaluate the efficacy of mitigation options by reviewing the body of current literature and scholarly research. A crucial objective in the fight against environmental change is to reduce GHG emissions from agriculture. The long-term consequences of GHG emissions are taken into consideration by51, which suggests that the capacity of agricultural systems to generate food and other agricultural products is anticipated to be negatively impacted for some time by changes in climatic patterns and conditions. Like other fields, agriculture exhibits various features regarding GHG emissions and energy use52. However, the GHG emissions from livestock, agriculture, and fisheries are significantly greater than those from traditionally high-emission and highly resource-intensive sectors53,54. In addition, most of the greenhouse emissions arise from crop cultivation and animal grazing55,56 and supplementary use of chemicals in agriculture, especially synthetic nitrogen fertilizer. After fertilizer is applied, microbial activity in the soil releases nitrogen oxide. Sustainable agricultural techniques are essential to reduce these emissions and advance climate-smart agriculture. These approaches include conservation agriculture and fertilizer optimization57.

In the context of China, a study was conducted (Rehaman et al.58) by using the granger causality (GC) test and Vector Autoregressive (VAR) model covering the timeframe from 1990–2017. A study showed the substantial influence of CO2 emissions on agricultural variables in China. The study’s conclusions emphasized the intricate connections between carbon dioxide emissions and important agricultural variables such as temperature, rainfall, animal output, and crop productivity. While encouraging economic growth and energy efficiency, it is imperative to focus on the significance of GHG emissions6,49,59. Salari et al.60 analyzed the impact of globalization, renewable energy usage, and agricultural output on the environmental footprints in developing countries and employed a panel quantile regression model. Their results discovered that the use of renewable energy meaningfully increased the footprint, particularly at higher quantiles. Agricultural total output exhibited a significant positive association with the ecological footprint at median quantiles, highlighting its role in environmental pressures. For sustainable development, the consumption of energy is crucial to meet the stability of the country. Ref.61 examined the correlation among energy consumption, economic growth, and green emissions in the agriculture sector of China. According to their assessments based on the environmental kuznets curve (EKC) model, the hypothesis for China’s main grain-producing areas and its impact on emissions, the use of time series data and various econometric models, such as the ARDL model and GC test, reveal both short- and long-run negative impacts of agricultural energy consumption on carbon emissions. Additionally, there is a unidirectional correlation between agricultural energy use, emissions, and economic development, and growth and carbon emissions from agriculture are influenced by a bidirectional causal relationship.

Nevertheless, the issue of agriculture-based emissions is challenging for nations (Mielcareket al.62, Dar et al.63). To tackle this issue, Ref.64 conducted a study on empirical-based to highlight the linkages between agricultural productivity, crop production, and the influence of fertilizer consumption on emissions in Nepal. This study showed how agricultural productivity, fertilizer, and crop output positive and negative shocks affected Nepal’s emissions between 1965–2018. According to the results of the NARDL model, the land area used for crop production increased emissions in the long run, while crop productivity has no discernible impact on emissions, on the other hand, fertilizer consumption in the agriculture of Nepal is linked to both short- and long-term emissions increases. Conversely, a strong positive correlation between GHG emissions and climate was found by (Bhatti et al.65) in their study that GHG emissions will rise globally66, and decrease GHG emissions globally due to the loss of crops (Nalley et al.67).

Fertilizer use in agriculture has increased as a result of the need to boost crop yields and satisfy food demand for the growing rapidly population68. Conversely, farmers’ overuse of fertilizer may negatively affect the environment, including GHG emissions like CO2 and N2O. A particularly strong GHG with a significant potential for global warming contributes to climate change by using excessive in N2O the field. Ref. discussed the relationship between the different types of fertilizer (K2O, and K2O per unit) impact on GHG emissions, the results showed that increasing one percent of nitrous oxide contributes 47.71% of the overall GHG emissions. In contrast, calcium superphosphate, ammonium bicarbonate, and potassium chloride fertilizers emit less emissions. But another study conducted by69 on Chinese data, urged that synthetic nitrogen fertilizer significantly contributes to emissions of GHG. Additionally, a fresh study was conducted by70 on GHG emissions and fertilizer management. The results proved that fertilizer management applications in agriculture are important for food security and reducing emissions from agriculture. Wrong fertilizer management and practices, such as inefficient use, and overapplication may increase GHG as evidenced by71.

Previous and some current studies illustrated the correlation between forestry and GHG emissions72,73, one major factor of the world’s GHG emissions is the deterioration of forests as highlighted by74. It is very important to understand the deep relationship between forest degradation and GHG emissions. A study conducted by75, is based on an empirical estimation of GHG emissions and forest degradation in 27 developing countries and 2.2 billion hectares of forest land from 1998 to 2017. As per the study estimation, 2.1 billion tonnes of emissions were annually predicted to be emitted from forests, with 53% from the collection of lumber, 30% from the extraction of wood fuel, and 17% from forest fires. Deforestation contributes 25% of all emissions from deforestation and forest degradation. Another study was conducted by (Houghton et al., 2012) on net emissions from degradation and deforestation in the tropics, and the study data was collected from 1990 to 2010. The study results show that 60 to 90% of the emissions of forests come from deforestation, the main reason for deforestation is agriculture as people shift forest land permanently and cut the forest plantations to harvest crops for food.

The existing literature studies have furnished insights into the importance of GHG emissions and agriculture practices. Still, there remains a notable research gap in understanding the specific importance of emerging GHG emissions from agriculture in China. However, China’s agriculture emits more GHG gas emissions than other nations’ agriculture sectors. So far, no empirical studies have been conducted on the joint effect of agricultural land, energy use, fertilizer use, crop production, livestock production, fisheries production, agricultural value-added, and forestry area on GHG emissions in China.

Methodology

Data and source

This research focuses on China, which produces the most GHG gases and is also the country leading the world in agricultural production and consumption because of its high population. Depending on data accessibility and analytical clarity, we selected 1990–2020 yearly statistical data from two different sources. This period is essential for examining the impact of several elements in Chinese agriculture on the environment, particularly GHG emissions. This period encompasses notable transformations in agricultural methodologies, the integration of advanced technologies, variations in agricultural output, and the corresponding effects on climate change. Comprehending these processes is crucial for assessing China’s agriculture sector’s overall sustainability and environmental impact.

The statistical data for GHG emissions, crop production, forest area, livestock index, agricultural value-added, fisheries index, and agricultural land expansion originated from “World Bank Development” (WDI, 202476). GHG statistics in millions of tons (Mt) of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e). Entities such as the World Bank employ this measurement methodology to standardize the effects of different GHGs according to their capacity to exacerbate global warming. The data on agricultural land expansion, measured in square kilometers (sq.km), reflects the growth of land allocated for farming. Additionally, the data on fertilizer input, measured in kilograms (kg) per hectare of arable land, evaluates the intensity of fertilizer application in terms of agricultural productivity. The study accounts for data on livestock and crop production in international dollars. It represents the comprehensive performance of the agriculture sector. The data of Agricultural value-added is evaluated as a percentage of agriculture in national GDP (% of GDP), this measure underscores the agricultural sector’s economic worth to the wider economy. Furthermore, forestry land area quantified in (sq.km), statistic denotes the entire expanse of forestry land, which is crucial for comprehending the effects of forestry on biodiversity and climate change. In addition, fisheries production data quantified in metric tons, assesses the number of fishes produced, offering insights into the sustainability and health of aquatic resources. for this study, the data for energy used in agriculture is extracted from the National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBSC, 2024), this data is measured in hundred million kilowatt-hours (100 million kwh). The further variables overview, definitions, and descriptive statistics are given in (Table 1).

Explained variable: greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions

We use GHG emissions as the dependent variable in this study, indicating the environmental consequences of agricultural practices17,77,78. Comprehending GHG emissions is essential, as agriculture substantially contributes to global emissions, influenced by elements like crop cultivation, energy consumption, agricultural value addition, fertilizer application, land management practices, fisheries production, and livestock farming. This study seeks to clarify the impact of agricultural factors on GHG emissions,this emphasis is essential for formulating successful mitigation methods, especially in significant agricultural economies such as China, where reconciling food production with environmental sustainability is a fundamental challenge. However, mitigating GHG emissions is crucial for decreasing the carbon footprint and for securing long-term agricultural sustainability against evolving climate conditions.

Regressors and control variables

This study incorporates numerous independent variables to explain the factors influencing GHG emissions in agriculture. We added the energy consumption variables in agriculture, which is a significant factor, as technology, irrigation pumps, and other energy-intensive techniques increase carbon emissions, we used the energy consumption in agriculture variable as it comprehensively signifies the energy dynamics within the agricultural sector, including both renewable and non-renewable sources. By focusing on this variable, we aim to capture the broader impact of energy consumption on GHG emissions in agriculture. By comprehending and enhancing the correlation between fertilizer application and emissions, we included fertilizer as a regressor variable in the study. The research identifies fertilizer consumption as a main predictor variable, associating it with GHG emissions via mechanisms of nitrogen management, soil health, and agricultural practices however, the agriculture land area variable as an independent plays a crucial role, indicating the environmental impact of transforming forests, grasslands, or other natural ecosystems into agricultural land, an action that emits significant quantities of GHG into the upper atmosphere we may discern practical solutions for mitigating GHG emissions in agriculture, fostering sustainability, and bolstering food security. Furthermore, we included a list of variables as control variables in our study to find their impact on GHG emissions. The crop production variable as the control variable shows primary concern, as it substantially impacts emissions via land use changes, irrigation practices, and residue from crop disposal. In the study, we employ agricultural value-added to highlight agriculture’s economic production on GHG emissions, as it is crucial for evaluating the alignment or discord between economic growth objectives and environmental sustainability goals. In the study, we added fisheries and livestock production as regressor variables in the analysis due to their significant contribution to GHG emissions. Nevertheless, deforestation and afforestation in the forestry sector can directly or indirectly influence GHG emissions. To address this important aspect within agriculture, we included forest areas in our study to examine their contribution to greenhouse gas emissions.

Overall, many research scholars have explored the factors selected in this research before in the context of GHG emissions from agriculture. For instance, crop production and fertilizer consumption were studied by, fisheries production was analyzed by79,80, land use change and forestry were explored by (Nobel et al., 2020;81,46), livestock production studied by46,55,82,83 and energy used in agriculture analyzed by48,65. Overall, the mentioned studies provide a basis for incorporating these variables into our analysis to enhance our understanding of their influence on GHG emissions.

Model development

The productivity of crops doesn’t affect emission concentrations, land area used for crop production triggers higher emissions, whereas increased fertilizer usage increases CO2 emission levels in Nepal64. While energy use in agriculture can lead to environmental degradation, enhancing the value of agriculture can elevate Vietnam’s environmental quality from both long-term and short-term viewpoints (Raihan et al.46). The above studies linearly investigated the impact of agricultural indicators (crop yield, land use, fertilizer use, and agricultural energy consumption) on environmental degradation. This research follows the above studies and reveals the non-linear effects of agricultural indicators (crop yield, land use, fertilizer use, consumption of energy for agriculture, forestry area, and agricultural value-added) on GHG emissions. Thus, the following econometric model developed in this study represents GHG emissions as a function of selected variables:

Further, (Eq. 1) is elaborated in the following form:

where GHG, AGL, LFC, EUA, CPI, PI, FP, AVT, FL show the greenhouse gas emissions, agricultural land, fertilizer consumption, energy use for agriculture, crop production, livestock production, fisheries production, agricultural value-added, and forestry area, respectively. While the “t” in each parameter represents the time measurement and \({\vartheta }_{1}-{\vartheta }_{4}\) reveals the long-term effects of the independent factors on the response variable.

Furthermore, to examine the asymmetric effects, we focused on three critical variables (AGL, FC, and EUA), due to their substantial impact on GHG emissions. The (Eq. 3) employs a logarithmic transformation and differentiates between positive and negative variations in these variables to more accurately reflect their influence:

where l indicates the logarithmic transformation, \(\alpha\) represents the intercept, \(\gamma\) expresses the trend effects, \({\delta }_{1 }to {\delta }_{11}\) shows the variable’s coefficients, and \(\mu\) indicates the error term at time t.

In addition, to examine the effects of the independent variables on GHG emissions, this study follows the methodology of64, and (Mujtaba & Jena84) to employ the NARDL techniques. This technique is an advanced econometric technique that was developed by Shin et al.85. This econometric method allows us to decompose the selected explanatory variables (agricultural land, fertilizer consumption, and energy used in agriculture) into their positive (\({lAGL}_{t}^{+};{lFC}_{t}^{+};{lEUA}_{t}^{+}\)) and negative (\({lAGL}_{t}^{-};{lFC}_{t}^{-};{lEUA}_{t}^{-}\)) components, as illustrated below:

The NARDL model is formulated using (Eq. 4 to 9) to incorporate both positive and negative shocks. Thus, the asymmetric model can be estimated according to the farmwork defined in Eq. (3).

Likewise, to examine the short-run asymmetries using the Wald test in the context of both long- and short-run assessments. Here’s how present the ECM representation:

Result and discussion

Unit root test

To avoid errors in annual time series data analysis, the augmented dickey-fuller (ADF), phillips-perron (PP), and kwiatkowski-phillips-schmidt-shin (KPSS) unit root tests are applied to check the stationarity of the series to ensure that none of the underlying variables is stationary or integrated at I (2). The ADF and PP unit root test results in (Table 2). Confirm that GHG, FC, CPI, LPI, FP, and FL are non-stationary in levels but become stationary after first differencing. Furthermore, AGL for both ADF and PP tests remained stationary at the 1(0) level. In contrast, all underlying variables are stationary at the level except lnLPI and lnFL in KPSS unit root analysis.

Correlation analysis

In the study, we conducted a correlation analysis (Table 3) and the correlation results indicate significant relationships among variables impacting GHG emissions. lnGHG has a strong positive correlation with lnFC, and lnAVA shows a strong negative correlation with lnGHG, highlighting that efficiency and sustainable practices can reduce emissions. While lnAGL has a moderate positive correlation with lnGHG, it plays a less critical role. Overall, the findings emphasize the role of efficiency and controlled resource use in mitigating emissions.

The findings of the bound test for cointegration

Table 4 shows information about the NARDL bounds testing method for cointegrating relationships between variables. The bounds test F-statistic (7.998) is greater than the upper bound, which confirms the existence of a long-run relationship between the underlying variables.

NARDL and ARDL model findings

After confirming the cointegration relationship between the series of variables, the ARDL and NARDL models were used to unveil the impact of agricultural land, fertilizer consumption, agricultural energy, crop production, agricultural added value, fishery production, forestland and livestock production on GHG emissions. The results in Table 5 show that all explanatory variables with positive shocks have considerable and significant effects on GHG emissions. The correlation between agricultural land with positive shock (AGL+) and GHGs is substantial and positive, suggesting that agricultural land has a non-linear progressive influence on GHG emissions. Over the long term, every 1% expansion of agricultural land is associated with a significant increase in GHG emissions of 0.187%. On the other hand, agricultural land has a greater negative impact on GHGs. For every 1% reduction in agricultural land, GHG emissions can be significantly reduced by 0.316%. The results of the progressive impact of agricultural land on GHG emissions are consistent with19,46. Likewise, expanding the use of agricultural fertilizers could significantly increase GHG emissions. However, reducing fertilizer use can significantly condense emissions. A 1% increase in fertilizer consumption is associated with a 0.463% increase in GHGs. On the other hand, a 1% reduction in fertilizer consumption can significantly reduce GHG emissions by 0.092%. The results of the nonlinear asymptotic association between fertilizer consumption and GHG emissions are consistent with those46,86, and contrary to those47,87. The current findings suggest that increased use of chemical fertilizers in the agricultural sector may increase GHG emissions and lead to long-term environmental degradation. To sustain farms and reduce pollution, the excessive use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides in agriculture must be reduced70. In addition, the Chinese government should develop environmentally sustainable fertilizers to reduce GHG and increase crop yields88. Furthermore, the analysis results show that there is also a positive correlation between agricultural energy consumption and GHG emissions. For every 1% increase in agricultural energy consumption, GHG emissions will increase by 0.242%, for every 1% reduction in agricultural energy use, GHG emissions can be significantly reduced by 0.762%. The positive link between energy consumption and GHG emissions reflects China’s heavy reliance on fossil fuels, especially coal, which makes it a major contributor to global CO2 emissions. Reducing this impact requires transitioning to renewable energy and improving energy efficiency. This result is consistent with the results of89,90,91. Livestock production, crop production index, and fishery production also have significant positive correlations with GHG emissions. A 1% increase in the crop production index and fishery will lead to a significant increase in GHG emissions of 0.044 and 0.491% respectively. The positive correlation between crop and livestock production and GHG emissions is influenced by emissions generated during livestock digestion and manure management, as well as the soil management strategies employed in crop production. Adopting sustainable agriculture techniques is crucial for mitigating these emissions. 4692,93 support our results on the significant and favorable correlation of crop production, fisheries, and livestock production with GHG emissions. In addition, there is a significant positive correlation between agricultural value-added (AVA) and GHG emissions. For every 1% increase in agricultural value added, GHG emissions will significantly increase by 0.345%.94,95 support this result, as agriculture value added positively impacts GHG emissions because higher production often involves activities like livestock farming and fertilizer use, which release greenhouse gases. This highlights the importance of adopting sustainable farming practices, but96 contradict it as mentioned that GHG can be reduced by adopting sustainable and advanced farming methods as high agriculture value added enough to support such practices. Furthermore, in the long run, forest land has a significant negative correlation with GHG emissions, with every 1% increase in forest land associated with a 0.825% decrease in GHG emissions. This result supports the results of43,46,97. Increased investment in forests could reduce China’s GHG emissions, and using forests for farming is one possible way to control emissions.

Diagnostic test results are shown at the end of the (Table 5), reflecting that the model is robust and consistent. The R-squared and adjusted R-squared values present a reliable and significant model fit because the input variables are explained by variation. The results of LM and Jarque–Bera tests prove that the variables in the model are normally distributed and there is no serial correlation. This model does not have heteroscedasticity and fits the Ramsey function form well.

The results of asymmetric causality

Table 6 shows the short-term symmetric and asymmetric adjustment results, reflecting those positive shocks to agricultural land, energy use in agriculture, and fertility consumption can significantly contribute to greenhouse gas emissions. Negative shocks to agricultural land, energy use in agriculture, and fertility consumption can significantly reduce GHG emissions. Likewise, agriculture value addition can also significantly promote GHG emissions. However, crop production, livestock production, and forest land can significantly reduce emissions in the short term. The error correction mechanism (ECM) coefficient is −0.266, indicating that short-term shocks can be recovered at an annual growth rate of 26%.

Dynamic multiplier findings

The dynamic multiplier plots in Fig. 3, 4, and 5 support the results of the asymmetric analysis of long- and short-term correlations between agricultural land use, fertility use, agricultural energy use, and GHG emissions. A positive shock to the agricultural land can significantly promote GHG emission, while a negative shock to the agricultural land can reduce GHG emission, which supports the AGL dynamic multiplier graph, as shown in (Fig. 2), short-run inequality adjusts to equilibrium after about two years. Likewise, the asymmetry in the association between fertility consumption and GHG emission is also supported by the FC dynamic multiplier plot in (Fig. 3). A positive shock to the partial sum of FC can increase emissions, while a negative shock to the partial sum of FC can reduce GHG emissions, which can be observed in the FC dynamic multiplier plot. The dynamic multiplier diagram of energy use in agriculture also supports the long-term asymmetric relationship between energy use in agriculture and GHG emissions. The dynamic multiplier plot of the energy use in agriculture in (Fig. 4) verifies the result that positive shocks to the sum of EUA can increase GHG emissions, while a negative shock to the sum of EUA can condense GHG emissions.

In addition, to test the stability of the model, the recursive cumulative sum of squares (CUSUM) and recursive residual cumulative sum of squares (CUSUMSQ) tests were also used. The blue line in both plots represents the residual values, while the red line represents the confidence level. (Fig. 5) shows the CUSUM and CUSUMSQ plots for the linear model at the 5% significance level, where the CUSUM and CUSUMSQ plots for the nonlinear model are shown in (Fig. 6). The sample data for the selected variables lie within the range, supporting the stability of the model.

Conclusion and policy implications

China is an emerging economy and one of the world’s largest emitters of GHGs, accounting for nearly 31% of global emissions. The agricultural sector, energy, and fertilizer use in agriculture are the main reasons for the increase in GHG emissions in China. To this end, this study used ARDL and NARDL techniques to empirically reveal the impact of agricultural land, fertilizer consumption, energy used in agriculture, livestock production index, crop production index, and fisheries production on China’s emissions from 1990 to 2020. The NARDL results indicate that with positive shock result of agriculture land to GHG emission is substantial and shows positive co-relation, it reveals that agriculture land has a non-linear progressive influence on emissions. On the other hand, negative shocks to agricultural land have a greater negative impact on the emissions of China. Likewise, expanding the use of agricultural fertilizers could significantly increase GHG emissions, and reducing fertilizer use can significantly condense emissions in the case of China. There is also a positive relationship between agricultural energy consumption and GHG emissions. The lower the energy use in agriculture, the lower the GHG emissions. Livestock production, crop production, and fishery production also have significant positive correlations with GHG emissions. The findings of the study also proved a significant positive correlation between AVA and GHG emission in the long run, forest land has a significant negative correlation with GHG emissions. The primary focus of the study is to investigate the effects of escalating GHG emissions from agricultural activities and promote sustainable practices in Chinese agriculture.

We propose some policy recommendations based on the study’s outcome as China’s agricultural sector heavily depends on practices such as excessive use of synthetic fertilizers, monoculture farming, and intensive livestock production, all of which contribute substantially to GHG emissions. This study recommends that policymakers in China strengthen the “green agricultural development practical action plan” by prioritizing the transition to sustainable farming practices. Efforts should focus on reducing dependence on chemical fertilizers and pesticides, aiming to mitigate their environmental impact and lower GHG emissions. Second, the country’s agricultural departments should implement a dual-control action plan that monitors both carbon emissions and energy consumption in the agriculture sector. This approach aims to reduce emissions while maintaining energy security, aligning with China’s broader sustainable development goals. In addition to this, energy consumption in China’s agriculture is considered an important source of GHG emissions. Converting fossil fuel energy to renewable energy will help achieve China’s long-term GHG emissions reduction goals. Third, to promote sustainable agriculture and reduce emissions, policymakers should encourage crop rotation and diversification to enhance soil health and reduce dependency on chemical fertilizers. Additionally, conservation tillage practices should be promoted to sequester carbon in the soil and lower energy consumption. Finally, the Chinese government should adopt strong environmental and climate change policies and also prioritize forestland expansion, which can help maintain environmental quality and promote the development of a green economy. Implementing these guidelines will enable the agricultural sector to achieve substantial reductions in GHG emissions while fostering sustainable practices that enhance both environmental health and agricultural output.

Study limitations and future directions

This study has explored the strong dynamic relationship between agricultural land, fertilizer consumption, energy used in agriculture, livestock production, crop production, and fisheries production on China’s GHG emissions. Hence, this study identifies some limitations and future directions This research work only expresses the long-term nonlinear effects of land use in agriculture, fertilizer consumption, and agricultural energy use in Chinese agriculture on GHG emissions. Therefore, in the next step of research, it is important to study the nonlinearity impact of other variables, such as forest land, livestock production index, crop production index, and fisheries production on GHG emissions, because these all are main variables in agriculture and they have a direct and indirect contribution to carbon emissions. The total amount of fertilizers and pesticides should be analyzed to understand their significant impact on sustainable agricultural production and total agricultural GHG emissions. This study considers energy used in agriculture but needs to measure renewable and non-renewable energy in Chinese agriculture. In the future, separate intercorrelated estimates are needed for agricultural land use and GHG emissions, renewable and non-renewable energy use and GHG emissions in agriculture; crop, livestock, and fishery production and GHG emissions; and forest land and GHG emissions.

Data availability

The data we used for our analysis are available publicly from reputable sources. Data on GHG emission in China, agriculture land, fertilizer consumption, crop production index, livestock production index, fisheries production, agriculture value-added, and forest land data were obtained from the World Development Indicators (WDI) of World Bank (https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators). The data on energy used in Chinese agriculture is sourced from the National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBSC) at https://www.stats.gov.cn. You can find these datasets online and obtain them for validation and further research.

References

Muluneh, M. G. Impact of climate change on biodiversity and food security: a global perspective—A review article. Agric. Food Secur. 10(1), 1–25 (2021).

WRI. Climate data for action: Climate Watch emissions and policies. https://ww.climatewatchdata.orga/ (2023).

Habiba, U. & Xinbang, C. The contribution of different aspects of financial development to renewable energy consumption in E7 countries: The transition to a sustainable future. Renew. Energy 203, 703–714 (2023).

Sun, Z., Zhang, X. & Gao, Y. The impact of financial development on renewable energy consumption: A multidimensional analysis based on global panel data. Int. J. EnviroN. Res. Public Health 20(4), 3124 (2023).

Yuping, L. et al. Determinants of carbon emissions in Argentina: The roles of renewable energy consumption and globalization. Energy Rep. 7, 4747–4760 (2021).

Wang, D., Hussain, R. Y. & Ahmad, I. Nexus between agriculture productivity and carbon emissions a moderating role of transportation; evidence from China. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 1065000 (2023).

Hu, Y., Su, M. & Jiao, L. Peak and fall of China’s agricultural GHG emissions. J. Clean. Prod. 389, 136035 (2023).

IEA. IEA Wind TCP Annual Report 2022 Executive Summary. https://orbit.dtu.dk/en/publications/iea-wind-tcp-annual-report-2022-executive-summary (2023).

Ahmed, N., Xinagyu, G., Alnafissa, M., Sikder, M., & Faye, B. Evaluating the impact of sustainable technology, resource utilization, and climate change on soil emissions: A CS-ARDL analysis of leading agricultural economies. Clean. Eng. Technol. 100869 (2024).

Wollburg, P., Hallegatte, S. & Mahler, D. G. The Climate Implications of Ending Global Poverty (The World Bank, 2023).

WDI. (2020). World Bank Indicators of the total greenhouse gas emissions (kt of CO2 equivalent). https://prosperitydata360.worldbank.org/en/indicator/WB+CC+EN+ATM+GHGT+KT+CE (2020).

Zheng, Y., Zhou, M. & Wen, F. Asymmetric effects of oil shocks on carbon allowance price: Evidence from China. Energy Econ. 97, 105183 (2021).

Liang, H., Meng, Y. & Ishii, K. The effect of agricultural greenhouse gas emissions reduction policies: evidence from the middle and lower basin of Yangtze river China. Discov. Sustain. 3(1), 43 (2022).

World Bank. Agriculture, forestry, and fishing, value added (% of GDP). World Bank Databank. (2022).

Smil, V. Energy and Civilization: A History (MIT Press, 2018).

Raeeni, A. A. G., Hosseini, S. & Moghaddasi, R. How energy consumption is related to agricultural growth and export: An econometric analysis on Iranian data. Energy Rep. 5, 50–53 (2019).

Xu, B. & Lin, B. Can expanding natural gas consumption reduce China’s CO2 emissions?. Energy Econ. 81, 393–407 (2019).

Elahi, E., Khalid, Z. & Zhang, Z. Understanding farmers’ intention and willingness to install renewable energy technology: A solution to reduce the environmental emissions of agriculture. Appl. Energy 309, 118459 (2022).

Zhang, J., Jabbar, A., & Li, X. How Does China’s Agricultural Subsidy Policy Drive More Commercially Productive Small Farmers? The Role of Farmland Scale, Labor Supply, and Cropping Structural Change. Land 13(12), 2058 (2024).

Ali, M. I., Ceh, B. & Salahuddin, M. The energy-growth nexus in Canada: new empirical insights. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30(58), 122822–122839 (2023).

Menegat, S., Ledo, A. & Tirado, R. Greenhouse gas emissions from global production and use of nitrogen synthetic fertilisers in agriculture. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 1–13 (2022).

Matthews, E. Nitrogenous fertilizers: global distribution of consumption and associated emissions of nitrous oxide and ammonia. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycl. 8(4), 411–439 (1994).

Sah, P. K., Paudel, S., Oli, B., & Shrestha, A. Greenhouse gases (GHG) emissions from agricultural soil: A review. SSRN 4934905. (2024).

Feng, J., Feng, L., Wang, J. & King, C. W. Evaluation of the onshore wind energy potential in mainland China—Based on GIS modeling and EROI analysis. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 152, 104484 (2020).

Bai, Y. et al. Instability of decoupling livestock greenhouse gas emissions from economic growth in livestock products in the Tibetan highland. J. Environ. Manag. 287, 112334 (2021).

Elahi, E., Khalid, Z., Tauni, M. Z., Zhang, H. & Lirong, X. Extreme weather events risk to crop-production and the adaptation of innovative management strategies to mitigate the risk: A retrospective survey of rural Punjab Pakistan. Technovation 117, 102255 (2022).

FAOSTAT. (2022). World Food and Agriculture Statistical Yearbook 2022. https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/522c9fe3-0fe2-47ea-8aac-f85bb6507776/content.

NBS. (2020). National Bureau of Statistics of China at https://www.stats.gov.cn.

Zhou, W. et al. Reducing carbon footprints and increasing net ecosystem economic benefits through dense planting with less nitrogen in double-cropping rice systems. Sci. Total Environ. 891, 164756 (2023).

Gangopadhyay, S., Banerjee, R., Batabyal, S., Das, N., Mondal, A., Pal, S. C., & Mandal, S. Carbon sequestration and greenhouse gas emissions for different rice cultivation practices. Sustainable Production and Consumption 34, 90–104 (2022).

Peng, P., Namkung, J., Barnes, M. & Sun, C. A meta-analysis of mathematics and working memory: Moderating effects of working memory domain, type of mathematics skill, and sample characteristics. J. Educ. Psychol. 108(4), 455 (2016).

Bai, S., & An, S. A survey on automatic image caption generation. Neurocomputing 311, 291–304 (2018).

Gerber, P. J. et al. Tackling climate change through livestock: a global assessment of emissions and mitigation opportunities. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). (2013).

Chen, G. Q. & Zhang, B. Greenhouse gas emissions in China 2007: inventory and input–output analysis. Energy Policy 38(10), 6180–6193 (2021).

Dong, B. et al. Carbon emissions, the industrial structure, and economic growth: Evidence from heterogeneous industries in China. Environ. Pollut. 262, 114322 (2020).

Peng, B., Zheng, C., Wei, G. & Elahi, E. The cultivation mechanism of green technology innovation in manufacturing industry: From the perspective of ecological niche. J. Clean. Prod. 252, 119711 (2020).

Zhao, X., Peng, B., Elahi, E., Zheng, C. & Wan, A. Optimization of Chinese coal-fired power plants for cleaner production using Bayesian network. J. Clean. Prod. 273, 122837 (2020).

FAO, (2020). The State of the World’s Forests. https://www.fao.org/state-of-forests/en (2020).

Ray, N. E., Maguire, T. J., Al-Haj, A. N., Henning, M. C. & Fulweiler, R. W. Low greenhouse gas emissions from oyster aquaculture. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53(15), 9118–9127 (2019).

Read, P. & Fernandes, T. Management of environmental impacts of marine aquaculture in Europe. Aquaculture 226(1–4), 139–163 (2003).

Blanchard, J. L. et al. Linked sustainability challenges and trade-offs among fisheries, aquaculture, and agriculture. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1(9), 1240–1249 (2017).

IPCC. Mitigation of climate change contribution of working group III to the fourth assessment report of IPCC http://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/.htm. (2008).

Li, Z., Mighri, Z., Sarwar, S. & Wei, C. Effects of forestry on carbon emissions in China: evidence from a dynamic spatial Durbin model. Front. Environ. Sci. 9, 76067 (2021).

Ali, M. I., Islam, M. M. & Ceh, B. Growth-environment nexus in Canada: Revisiting EKC via demand and supply dynamics. Energy Environ. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958305X241263833 (2024).

Corbera, E., Estrada, M. & Brown, K. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries: revisiting the assumptions. Clim. Change 100(3), 355–388 (2010).

Raihan, A., Rashid, M., Voumik, L. C., Akter, S., & Esquivias, M. A. The dynamic impacts of economic growth, financial globalization, fossil fuel, renewable energy, and urbanization on load capacity factor in Mexico. Sustainability 15(18), 13462 (2023).

Chandio, A. A., Akram, W., Ahmad, F. & Ahmad, M. Dynamic relationship among agriculture-energy-forestry and carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions: empirical evidence from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 34078–34089 (2020).

Flammini, A. et al. Emissions of greenhouse gases from energy use in agriculture, forestry and fisheries: 1970–2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14(2), 811–821 (2022).

Liu, Y. & Feng, C. What drives the decoupling between economic growth and energy-related CO2 emissions in China’s agricultural sector?. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 44165–44182 (2021).

Song, S., Zhao, S., Zhang, Y. & Ma, Y. Carbon emissions from agricultural inputs in China over the past three decades. Agriculture 13(5), 919 (2023).

Hui, D., Deng, Q., Tian, H. & Luo, Y. Global climate change and greenhouse gases emissions in terrestrial ecosystems. In Handbook of Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation 23–76 (Springer, 2022).

Kamyab, H., SaberiKamarposhti, M., Hashim, H., & Yusuf, M. Carbon dynamics in agricultural greenhouse gas emissions and removals: a comprehensive review. Carbon Lett. 1–25 (2023).

Badji, A., Benseddik, A., Bensaha, H., Boukhelifa, A. & Hasrane, I. Design, technology, and management of greenhouse: A review. Journal of Cleaner Production 373, 133753 (2022).

Chen, J., Fei, Y., & Wan, Z. The relationship between the development of global maritime fleets and GHG emission from shipping. J. Environ. Manage. 242, 31–39 (2019).

Garnett, T. Livestock-related greenhouse gas emissions: impacts and options for policy makers. Environ. Sci. Policy 12(4), 491–503 (2009).

Sakadevan, K., & Nguyen, M. L. Livestock production and its impact on nutrient pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. Advances in Agronomy 141, 147–184 (2017).

Elrys, A. S. et al. Traditional, modern, and molecular strategies for improving the efficiency of nitrogen use in crops for sustainable agriculture: a fresh look at an old issue. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 22(3), 3130–3156 (2022).

Rehman, A., Alam, M. M., Ozturk, I., Alvarado, R., Murshed, M., Işık, C., & Ma, H. Globalization and renewable energy use: how are they contributing to upsurge the CO2 emissions? A global perspective. Environ. Sci. Pollution Res. 30(4), 9699–9712 (2023).

Wang, R., Chen, J., Li, Z., Bai, W. & Deng, X. Factors analysis for the decoupling of grain production and carbon emissions from crop planting in China: A discussion on the regulating effects of planting scale and technological progress. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 103, 107249 (2023).

Salari, T. E., Roumiani, A. & Kazemzadeh, E. Globalization, renewable energy consumption, and agricultural production impacts on ecological footprint in emerging countries: using quantile regression approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28(36), 49627–49641 (2021).

Zhang, L., Pang, J., Chen, X. & Lu, Z. Carbon emissions, energy consumption, and economic growth: Evidence from the agricultural sector of China’s main grain-producing areas. Sci. Total Environ. 665, 1017–1025 (2019).

Mielcarek-Bocheńska, P., & Rzeźnik, W. Greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture in EU countries—state and perspectives. Atmosphere 12(11), 1396 (2021).

Dar, A. A., Hameed, J., Huo, C., Sarfraz, M., Albasher, G., Wang, C., & Nawaz, A. Recent optimization and panelizing measures for green energy projects; insights into CO2 emission influencing to circular economy. Fuel 314, 123094 (2022).

Rehman, A. et al. The asymmetric effects of crops productivity, agricultural land utilization, and fertilizer consumption on carbon emissions: revisiting the carbonization-agricultural activity nexus in Nepal. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29(26), 39827–39837 (2022).

Bhatti, U. A. et al. Global production patterns: Understanding the relationship between greenhouse gas emissions, agriculture greening and climate variability. Environ. Res. 245, 118049 (2024).

El-Montasser, G., Inglesi-Lotz, R. & Gupta, R. Convergence of greenhouse gas emissions among G7 countries. Appl. Econ. 47(60), 6543–6552 (2015).

Nalley, L., Popp, M., & Fortin, C. The impact of reducing greenhouse gas emissions in crop agriculture: A spatial-and production-level analysis. Agri. Res. Econ. Review 40(1), 63–80 (2011).

Roberts, T. L. The role of fertilizer in growing the world’s food. Better Crops 93(2), 12–15 (2009).

Kahrl, F. et al. Greenhouse gas emissions from nitrogen fertilizer use in China. Environ. Sci. Policy 13(8), 688–694 (2010).

Li, J. et al. Optimizing potassium and nitrogen fertilizer strategies to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions in global agroecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 916, 170270 (2024).

Nayak, D. et al. Management opportunities to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions from Chinese agriculture. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 209, 108–124 (2015).

Miles, L. & Kapos, V. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation and forest degradation: global land-use implications. Science 320(5882), 1454–1455 (2008).

Si, R., Aziz, N. & Raza, A. Short and long-run causal effects of agriculture, forestry, and other land use on greenhouse gas emissions: evidence from China using VECM approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 64419–64430 (2021).

De Sy, V. et al. Tropical deforestation drivers and associated carbon emission factors derived from remote sensing data. Environ. Res. Lett. 14(9), 094022 (2019).

Pearson, T. R., Brown, S., Murray, L. & Sidman, G. Greenhouse gas emissions from tropical forest degradation: an underestimated source. Carbon Balance Manag. 12, 1–11 (2017).

WDI. (2024). World Bank Indicators Global CO2 emissions. https://databank.worldbank.org/metadataglossary/world-development-indicators/series/EN.CO2.OTHX.ZS#:~:text=Global%20emissions%20of%20carbon%20dioxide,or%20by%201.6%25%20per%20year (2024).

Driscoll, A. W., Conant, R. T., Marston, L. T., Choi, E. & Mueller, N. D. Greenhouse gas emissions from US irrigation pumping and implications for climate-smart irrigation policy. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-44920-0 (2024).

Ivanovich, C. C., Sun, T., Gordon, D. R. & Ocko, I. B. Future warming from global food consumption. Nat. Clim. Change https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-023-01605-8 (2023).

MacLeod, M. J., Hasan, M. R., Robb, D. H. F. & Mamun-Ur-Rashid, M. Quantifying greenhouse gas emissions from global aquaculture. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-68231-8 (2020).

Xu, Y., Lin, J., Yin, B., Martens, P. & Krafft, T. Marine fishing and climate change: A China’s perspective on fisheries economic development and greenhouse gas emissions. Ocean Coast. Manag. 245, 106861 (2023).

Datta, A. & Krishnamoorti, R. Understanding the greenhouse gas impact of deforestation fires in Indonesia and Brazil in 2019 and 2020. Front. Clim. 4, 799632 (2022).

Shi, R., Irfan, M., Liu, G., Yang, X. & Su, X. Analysis of the impact of livestock structure on carbon emissions of animal husbandry: A sustainable way to improving public health and green environment. Front. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.835210 (2022).

Manzano, P., del Prado, A. & Pardo, G. Comparable GHG emissions from animals in wildlife and livestock-dominated savannas. NPJ Clim. Atmosph. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-023-00349-8 (2023).

Mujtaba, A., & Jena, P. K. Analyzing asymmetric impact of economic growth, energy use, FDI inflows, and oil prices on CO2 emissions through NARDL approach. Environ. Sci. Pollution Res. 28(24), 30873–30886 (2021).

Shin, Y., Yu, B., & Greenwood-Nimmo, M. Modelling asymmetric cointegration and dynamic multipliers in a nonlinear ARDL framework. Festschrift in honor of Peter Schmidt: Econometric methods and applications, 281-314 (2014).

Ahmad, R., Liu, G., Rehman, S. A. U., Fazal, R., Gao, Y., Xu, D., Agostinho, F., Almeida, C.M.V.B., & Giannetti, B. F. Pakistan road towards Paris Agreement: Potential decarbonization pathways and future emissions reduction by A developing country. Energy 314, 134075 (2025).

Khan, Z., Ali, S., Umar, M., Kirikkaleli, D., & Jiao, Z. Consumption-based carbon emissions and international trade in G7 countries: the role of environmental innovation and renewable energy. Sci. Total Environ. 730, 138945 (2020).

Wu, Y., Wang, E. & Miao, C. Fertilizer use in China: The role of agricultural support policies. Sustainability 11(16), 43 (2019).

Koondhar, M. A. et al. Asymmetric causality among carbon emission from agriculture, energy consumption, fertilizer, and cereal food production—A nonlinear analysis for Pakistan. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 45, 101099 (2021).

Zhong, X., Hu, M., Deetman, S., Steubing, B., Lin, H. X., Hernandez, G. A., Harpprecht, C., Zhang, C., Tukker, A., & Behrens, P. Global greenhouse gas emissions from residential and commercial building materials and mitigation strategies to 2060. Nature Communicat. 12(1), 6126 (2021).

Ben Jebli, M., & Ben Youssef, S. Renewable energy consumption and agriculture: evidence for cointegration and Granger causality for Tunisian economy. Int. J. Sustain. Develop. World Ecology 24(2), 149–158 (2017).

Ali, S., Shah, A. A., Ghimire, A. & Tariq, M. A. U. R. Investigation of the nexus between CO2 emissions, agricultural land, crop, and livestock production in Pakistan. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 1804 (2022).

Ullah, S., Akhtar, P. & Zaefarian, G. Dealing with endogeneity bias: The generalized method of moments (GMM) for panel data. Ind. Market. Manag. 71, 69–78 (2018).

Jebli, M. B., Farhani, S. & Guesmi, K. Renewable energy, CO2 emissions, and value-added: Empirical evidence from countries with different income levels. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 53, 402–410 (2020).

Wang, L., Vo, X. V., Shahbaz, M. & Ak, A. Globalization and carbon emissions: is there any role of agriculture value-added, financial development, and natural resource rent in the aftermath of COP21?. J. Environ. Manag. 268, 110712 (2020).

Ali, S. et al. Analysis of the nexus of CO2 emissions, economic growth, land under cereal crops, and agriculture value-added in Pakistan using an ARDL approach. Energies 12(23), 4590 (2019).

Waheed, R., Chang, D., Sarwar, S. & Chen, W. Forest, agriculture, renewable energy, and CO2 emission. J. Clean. Prod. 172, 4231–4238 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors of this study extend their appreciation to Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2025R932), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.A. collected the data, performed primary analysis, and wrote the main manuscript text. X.G. A. A and M. A. reviewed the manuscript and made the corrections. H.G. read and edited the corrections.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmed, N., Xinagyu, G., Alnafissa, M. et al. Linear and non-linear impact of key agricultural components on greenhouse gas emissions. Sci Rep 15, 5314 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88159-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88159-1