Abstract

Male cancers, which refers to cancers that occur exclusively in males, is a prevalent type of cancer worldwide, primarily including prostate cancer (PCa) and testicular cancer (TCa). These cancers are significant contributors to the global disease burden. We aim to study specific patterns and trends in male cancers from 1990 to 2021 to inform health policy, allocation of medical resources, and optimization of patient management plans. We analyzed Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2021 on male cancers data for 21 regions and 204 countries to understand better the health burden using prevalence, incidence, mortality, and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). We tested correlations with Socio-demographic Index (SDI) using Spearman’s analysis. Decomposition analysis was utilized to dissect the reasons behind changes in epidemiological indicators of the disease, and autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) modeling forecasted future disease trends. In 2021, the age-standardized rates (ASR) per 100,000 people for PCa in terms of prevalence, incidence, deaths, and DALYs were 260.05, 34.05, 12.63, and 217.83, respectively, while for TCa were 16.59, 2.24, 0.29, and 13.83, respectively. Compared to 1990, the ratios for PCa changed by 0.19, 0.04, -0.23, and − 0.21, respectively, and for TCa they changed by 0.66, 0.5, -0.14, and − 0.08, respectively. Age analysis revealed a heavier burden of PCa after the age of 70 and a heavier burden of TCa in the 25–34 age group. In regions with High SDI, the ASR for prevalence and incidence were higher, while in regions with Low SDI, the ASR for deaths and DALYs were higher. Aging was the main reason for the increase in PCa, epidemiological change was the main reason for TCa, and population growth was the main reason for death change from 1990 to 2021. Smoking and high calcium diets are risk factors for PCa. For the forecast in 2040, the ASR indicators for PCa in terms of prevalence, incidence, deaths, and DALYs per 100,000 people are projected to be 266.23, 35.21, 9.11, and 176.16, respectively; for TCa cancer they are projected to be 20.63, 2.7, 0.26, and 12.73, respectively. From 1990 to 2021 and with projections to 2040, the prevalence and incidence of global male cancers generally show an upward trend, while deaths and DALYs exhibit a downward trend. Additionally, the higher burden of PCa in individuals over the age of 70 and TCa in the middle-aged group of 25 to 34 years highlights the urgent need for healthcare professionals and policymakers to propose innovative prevention and healthcare strategies based on the existing burden and its new changes, to alleviate the global burden of male cancers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Male cancers, defined as cancers that occur exclusively in males, primarily includes prostate cancer (PCa) and testicular cancer (TCa) and poses a significant challenge to global men’s health. With the growth of the global population and rapid societal advancements, the burden of these cancers is also steadily increasing1. PCa is one of the most common malignant tumors in men2, where a usual lack of initial or early symptoms leads to many patients being diagnosed at a late stage, by which time the cancer has likely metastasized3. Advanced PCa can lead to fatigue due to anemia, bone pain, paralysis caused by spinal metastases, and renal failure due to bilateral ureteral obstruction3. While TCa is relatively rare, it has a higher incidence rate among young men4,5. The majority (> 95%) of TCa are germ cell tumors (GCT) caused by primitive germ cells5. The etiology of this cancer remains unclear, but it is related to both genetic and acquired factors, with cryptorchidism being a significant risk factor6. Although the mortality rate of TCa is currently controlled, if not detected and treated in time, it can still have a severe impact on the fertility and overall health of young patients7. Furthermore, the psychological impact of a male cancer diagnosis should not be underestimated, as anxiety, tension, damaged self-esteem, and increased risk of depression are common psychological disturbances associated with the diagnosis of male cancers8,9. Data from the European Commission show that in Europe, PCa is the third leading cause of cancer death in men10. In 2017, the healthcare cost associated with PCa was estimated at 5.8 billion euros10. According to the Global Cancer Observatory database, there is a significant increasing trend in TCa, and this trend is more pronounced among younger populations8. While epidemiological studies on female cancers have been widely discussed11,12, there is still a significant gap in the overall grasp of the disease burden data for male cancers. The current analyses of the epidemiological trends of male cancers are not comprehensive, with their findings focusing solely on TCa6 or PCa13. Concurrently, while some reports have revealed varying regional disparities in the burden of male cancers14, these data are either outdated or have only examined a limited number of specific countries and regions4,14. Consequently, there is an urgent need for the most current data and a comprehensive analysis of the global disease burden of male cancers.

The GBD 2021, led by University of Washington, conducted an in-depth assessment of the health hazards related to 371 diseases and injuries and the decomposition of 288 causes of death and life expectancy, covering 204 countries and territories, supported by more than 11,500 collaborators from 164 countries. Through extensive data provision, review, and analysis, it systematically assessed the global health status and disease burden11,15,16,17,18. Therefore, the GBD study is a reliable tool for understanding and assessing the current disease burden of male cancers.

Since the update of the GBD 2021 database, there has not been a systematic report on the epidemiology and trends of male cancers. In this study, we used GBD statistical models to systematically describe the disease burden of male cancer from 1990 to 2021, including prevalence, incidence, mortality, and DALYs, focusing on age distribution, temporal trends, ASR and SDI relationships, and future development predictions. With the changes in modern lifestyle and population aging, the burden of male cancers may further increase. This analysis helps clinicians, epidemiologists, and health policymakers to comprehensively understand the disease burden of male cancer, further optimize the allocation of medical resources, develop more effective public health strategies, and reduce the social burden brought by male cancer diseases.

Methods

Data source

The present study extracted global incidence, prevalence, deaths and DALYs (one DALY represents the loss of one year of full health due to premature death or disability), along with their 95% uncertainty intervals (UI), spanning from 1990 to 2021 from the GBD database (https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/). Data on age groups, risk factors, population, and sociodemographic index (SDI) were also included for comprehensive analysis.

SDI analysis

The SDI was employed as a metric to assess the socio-economic status of countries, with a higher score indicating more robust socio-economic development, which derived from national-level indicators encompassing per capita income, average educational attainment, and total fertility rate, the SDI assumes values ranging from 0 to 1. Countries were stratified into five quintiles based on the GBD studies: High SDI (> 0.81), High-middle SDI (0.70–0.81), Middle SDI (0.61–0.69), Low-middle SDI (0.46–0.60), and Low SDI (< 0.46). To examine the correlation between SDI and the burden of male cancers, locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (loess) models were applied, utilizing the geom_smooth function within the ggplot2 package. This analysis fitted the relationship across global data, 21 regions, and 204 countries and territories.

Decomposition analysis

To quantify the driving factors behind the changes in the number of male cancer cases, we estimated the relative contributions of aging, population, and epidemiological factors. For this decomposition analysis, we employed the classic method developed by Das Gupta19, which uses algebraic decomposition techniques to break down the overall change into the standardized impact of each factor, thereby identifying the contribution of each component.

Trend prediction

The Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) model is a commonly used technique in epidemiology for forecasting time series data20. The detailed method involves combining autoregressive (AR) and moving average (MA) elements with differencing (d) to stabilize the series. In the context of the ARIMA (p, d, q) model, the parameter p represents the autoregressive order, indicating that the current value is predicted using the values from the previous p time points. The autoregressive component implies a dependency of the current value on a linear combination of its preceding p values. The parameter d denotes the degree of differencing, which specifies the number of times the data needs to be differentiated to achieve stationarity. Differencing involves calculating the differences between adjacent observations to eliminate trends or seasonal components within the time series. The parameter q signifies the moving average order, signifying that the current value is predicted using the previous q error terms. The moving average component implies a dependency of the current value on a linear combination of the preceding q error terms.

Statistics analysis

Age-standardized prevalence rates (ASPR), age-standardized incidence rates (ASIR), age-standardized mortality rates (ASMR), and ASR of DALYs were expressed as predicted values per 100,000 population, including their 95% uncertainty intervals (UI). All analytical procedures and graphical representations were executed using the statistical software R (version 4.4.1).

Results

Global level

PCa

In 2021, the global number of prevalent cases of PCa was 10,387,521, with ASPR of 260.05; the number of incident cases was 1,324,383. The ASIR was 34.05; the number of deaths was 432,463. The ASMR was 12.63. The global number of DALYs was 8,141,561, with ASR of DALYs of 217.83. From 1990 to 2021, the ASPR increased by 0.19. From 1990 to 2021, the ASIR increased by 0.04. From 1990 to 2021, the ASMR decreased by -0.23. From 1990 to 2021, the ASR of DALYs decreased by -0.21 (Table 1).

TCa

In 2021, the global number of prevalent cases of TCa was 679,103, with ASPR of 16.59; the number of incident cases was 91,507. The ASIR was 2.24; the number of deaths was 11,388. The ASMR was 0.29. The global number of DALYs was 560,921, with ASR of DALYs of 13.83. From 1990 to 2021, the ASPR increased by 0.66. From 1990 to 2021, the ASIR increased by 0.5. From 1990 to 2021, the ASMR decreased by -0.14. From 1990 to 2021, the ASR of DALYs decreased by -0.08 (Table 2).

Regional level

PCa

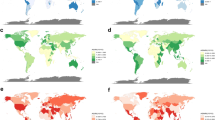

In 2021, a global study conducted across different regional levels found that, at the SDI level, the ASPR for PCa was highest in high SDI regions, at 612.57. Geographically, the region with the highest ASPR was high-income North America, at 910.62. In contrast, the ASPR was significantly lower in low-income regions, including low SDI at 70.35, and low-middle SDI at 85.84. the highest ASPR for PCa was in high SDI regions. The fastest increase was in middle SDI regions, with an upward trend of 1.12. Geographically, the region with the highest ASPR remained high-income North America. From 1990 to 2021, East Asia showed the most significant upward trend, at 2.11 (Table 1; Fig. 1A).

Global distribution of male cancers disease burden in 2021. (A) ASPR in PCa; (B) ASPR in TCa; (C) ASIR in PCa; (D) ASIR in TCa; (E) ASMR in PCa; (F) ASMR in TCa; (G) ASR of DALYs in PCa; (H) ASR of DALYs in TCa. ASPR: Age-standardized prevalence rates, ASIR: Age-standardized incidence rates, ASMR: Age-standardized mortality rates, ASR: Age-standardized rate, DALYs: Disability-adjusted life years; PCa: Prostate cancer, TCa: Testicular cancer.

As for the ASIR in 2021, at the SDI level, PCa remained highest in high SDI regions at 70.92, and the highest ASIR was still in high-income North America at 101.92. The fastest increase from 1990 to 2021 was in low-middle SDI regions at 0.68. From 1990 to 2021, Eastern Europe had the fastest ASIR increase at 1.47 (Table 1; Fig. 1C).

Regarding the ASMR in 2021, at the SDI level, the highest region for PCa became low SDI at 16.8. Geographically, the region with the highest ASMR was Southern Sub-Saharan Africa at 44.25. From 1990 to 2021, the low-middle SDI region had the fastest increase at 0.24. Geographically, Eastern Europe had the fastest ASMR increase at 0.51 (Table 1; Fig. 1E).

As for the DALYs for PCa in 2021, at the SDI level, the ASR of DALYs remained highest in low SDI regions at 294.26. Geographically, the ASR of DALYs remained highest in Southern Sub-Saharan Africa at 774.4. From 1990 to 2021, globally, at the SDI level, low-middle SDI had the fastest increasing trend at 0.24. Geographically, Eastern Europe showed the most significant increase at 0.54 (Table 1; Fig. 1G).

TCa

In 2021, a global study conducted across different regional levels found that, at the SDI level, the ASPR was highest in high SDI regions, at 53.24. Geographically, the highest ASPR was Southern Latin America, at 83.38. In contrast, the ASPR was significantly lower in low-income regions, including low SDI at 1.24, and low-middle SDI at 2.97. The fastest increase was in middle SDI regions, with an upward trend of 6.43. Geographically, the region with the highest ASPR for TCa was Australasia. From 1990 to 2021, Andean Latin America showed the most significant upward trend, at 12.8 (Table 1; Fig. 1B).

As for the ASIR in 2021, at the SDI level, high SDI remained the highest at 5.97, and the highest ASIR was still in Southern Latin America at 10.07. The fastest increase from 1990 to 2021 was in middle SDI regions at 2.13. From 1990 to 2021, the Caribbean had the fastest ASIR increase at 5.62 (Table 1; Fig. 1D).

Regarding the ASMR in 2021, at the SDI level, the highest region became high-middle SDI at 0.32. Geographically, the region with the highest ASMR was Southern Latin America at 1.07. From 1990 to 2021, the middle SDI region had the fastest increase at 0.12. Geographically, the Caribbean had the fastest ASMR increase at 2.53 (Table 1; Fig. 1F).

As for the DALYs for TCa in 2021, at the SDI level, the ASR of DALYs remained highest in high-middle SDI regions at 15.31. Geographically, the ASR of DALYs remained highest in Southern Latin America at 57.05. From 1990 to 2021, globally, at the SDI level, middle SDI had the fastest increasing trend at 0.23. Geographically, the Caribbean showed the most significant increase at 0.54 (Table 1; Fig. 1H).

National and territorial level

PCa

In 2021, the United States had the highest number of prevalent cases with 2,671,779 (Table S1). Bermuda had the highest ASPR at 1,527.67 (Fig. 1A and Table S3). From 1990 to 2021, South Korea had the largest relative increase in ASPR at 4.04 (Table S9).

In 2021, the country with the highest number of incident cases was the United States with 297,836 (Table S1). The country with the highest ASIR was Bermuda at 196.12 (Fig. 1C and Table S3). From 1990 to 2021, South Korea had the largest relative increase in ASIR at 2.4 (Table S9).

In 2021, the top three countries for the number of deaths were led by the United States with (Table S1). The country with the highest ASMR was Grenada at 93.9 (Fig. 1E and Table S3). From 1990 to 2021, Cabo Verde had the highest increase in ASMR at 1.37 (Table S9).

In 2021, the United States still had the highest number of DALYs at 912,428 (Table S1). The country with the highest ASR of DALYs was still Grenada at 1,542.79 (Fig. 1G, Table S3). From 1990 to 2021, Cabo Verde had the largest increase in ASR of DALYs at 1.38 (Table S9).

TCa

In 2021, the United States had the highest number of prevalent cases with 105,137 (Table S2). Monaco had the highest ASPR at 366.98 (Fig. 1B and Table S4). From 1990 to 2021, Ecuador had the largest relative increase in ASPR at 43.84 (Table S10).

In 2021, the country with the highest number of incident cases was the United States with 11,845 (Table S2). The country with the highest ASIR was Monaco at 40.44 (Fig. 1D and Table S4). From 1990 to 2021, Puerto Rico had the largest relative increase in ASIR at 14.64 (Table S10).

In 2021, the top three countries for the number of deaths were led by India with 1,823 (Table S2). The country with the highest ASMR was Georgia at 1.84 (Fig. 1H and Table S4). From 1990 to 2021, Belize had the highest increase in ASMR at 6.94 (Table S10).

In 2021, India had the highest number of DALYs at 94,226 (Table S2). The country with the highest ASR of DALYs was still Monaco at 72.83 (Fig. 1H, Table S4). From 1990 to 2021, Belize had the largest increase in ASR of DALYs at 7.27 (Table S10).

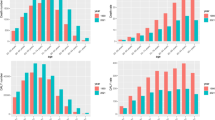

Age and subtype analysis

In 2021, for PCa, the age group of 70–74 years old had the highest numbers in prevalence, incidence, and DALYs, while the highest number of deaths was in the 80–84 age group (Fig. 2). For TCa, the age group of 25–29 years old had the highest numbers in prevalence, incidence, and DALYs, and the age group of 30–34 had the highest number of deaths, but it was essentially on par with the 25–29 age group (Fig. 2). For PCa, the rates of incidence, deaths, and DALYs all increase with age, with the highest rates in the 95 + age group. The rate of Prevalence peaks in the 75–79 age group. For TCa, the rates of Prevalence, incidence, and DALYs all peak in the 25–29 age group. The rate of deaths shows a small peak at 25–29 years old, then declines and begins to rise again after the age of 55, with the highest value in the 95 + age group (Fig. 2). When comparing the burdens of PCa and TCa, before the age of 45, the burden of TCa is greater than that of PCa, and after the age of 45, the burden of PCa is greater than that of TCa (Fig. 2). Subtype analysis in different regions shows that North Africa and the Middle East and Southern Latin America have the highest proportions of TCa in Prevalence and incidence, while South Asia and Central Asia have the highest proportions of TCa in deaths. For DALYs, South Asia has the highest proportion of PCa. Overall, in all four epidemiological indicators, the proportion of PCa is much greater than that of TCa (Figure S2).

age-structured analysis of male cancers disease burden in 2021. (A) The number of prevalence; (B) The rate of prevalence in PCa; (C) The rate of prevalence in TCa; (D) The number of incidence; (E) The rate of incidence in PCa; (F) The rate of incidence in PCa; (G) The number of deaths; (H) The rate of deaths in PCa; (I) The rate of deaths in TCa; (J) The number of DALYs; (K) The rate of DALYs in PCa; (L) The rate of DALYs in TCa. DALYs: disability-adjusted life years, PCa: Prostate cancer, TCa: Testicular cancer.

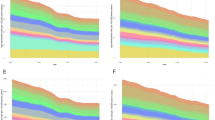

Overall temporal trends

From 1990 to 2021, the number of prevalence, incidence, deaths, and DALYs for PCa consistently showed an upward trend. The ASPR and ASIR for PCa slowed down after 1996, decreased after 2008, and showed no significant changes after 2013. The ASMR and ASR of DALYs for PCa showed a decline after 1994, with a slowdown in the rate of decrease after 2013. The number of prevalence, incidence, deaths, and DALYs for TCa showed an overall increasing trend before 2020, with the numbers remaining relatively stable between 2019 and 2021 (Fig. 3). The ASPR and ASIR for TCa generally showed an increasing trend, with a faster rise in 1995 and 1996. There was a slowdown and fluctuation in the increase from 1997 to 2001, and a downward trend began in 2020 (Fig. 3). The ASMR and ASR of DALYs for TCa showed a declining trend before 2008. They remained relatively stable from 2008 to 2014, then increased, but began to decline again in 2020 (Fig. 3). The detailed trends of PCa and TCa from 1990 to 2021 in the five SDI regions and 21 GBD regions are shown in Figure S3 (with data for PCa on the left and data for TCa on the right).

Overall temporal trends analysis of the male cancers burden, 1990–2021. (A) Prevalence number and age-standardized prevalence rates of PCa; (B) Prevalence number and age-standardized prevalence rates of TCa; (C) Incidence number and age-standardized incidence rates of PCa; (D) Incidence number and age-standardized incidence rates of TCa; (E) Deaths number and age-standardized mortality rates of PCa; (F) Deaths number and age-standardized mortality rates of TCa; (G) DALYs number and age-standardized rates of DALYs in PCa; (H) DALYs number and age-standardized rates of DALYs in TCa. DALYs: Disability-adjusted life years, PCa: Prostate cancer, TCa: testicular cancer.

Association between ASR and SDI

From 1990 to 2021, in the global and 21 regions, the ASPR and ASIR for PCa and TCa were relatively high in High SDI and High-middle SDI (Fig. 4A, C). In 2021, the association between SDI and ASPR and ASIR in 204 countries and territories was similar (Fig. 4E-H). For the ASMR and ASR of DALYs in PCa, the Low SDI, Middle SDI and High-middle SDI were were relatively high (Figure S4 A, C). For TCa, Middle SDI and High-middle SDI were were relatively high (Figure S4 B, D). The association between SDI and ASMR and ASR of DALYs in 204 countries and territories in 2021 was similar (Figure S4 E-H).

The association of the SDI and ASPR and ASIR of male cancers, globe and regions from 1990 to 2021, and countries and territories in 2021. (A) ASPR of PCa in the globe and regions; (B) ASPR of TCa in the globe and regions; (C) ASIR of PCa in the globe and regions; (D) ASIR of TCa in the globe and regions; (E) ASPR of PCa in countries and territories; (F) ASPR of TCa in countries and territories; (G) ASIR of PCa in countries and territories; (H) ASIR of TCa in countries and territories. SDI: Socio-demographic index, ASPR: Age-standardized prevalence rates, ASIR: Age-standardized incidence rates, PCa: Prostate cancer, TCa: Testicular cancer.

Decomposition analysis

From 1990 to 2021, in the case of PCa, aging was the main reason for the changes in global prevalence, incidence, deaths, and DALYs across all SDI levels (except the highest proportion of epidemiological change in Middle SDI for prevalence at 42.77% and Aging at 37.34%). In Low-middle SDI regions, the highest proportions for prevalence and incidence were due to epidemiological change, at 49.3% and 38.71%, respectively. For the remaining Low-middle SDI and Low SDI regions, the largest proportion of the four epidemiological indicators was attributed to population changes (Figure S5 and Table S11). In the case of TCa, for global and SDI regions, the largest proportion of changes in prevalence and incidence was due to epidemiological change (except for incidence in low SDI regions, where the largest proportion was attributed to population changes). For the changes in deaths and DALYs, globally and in all but the High SDI regions, the largest proportion was attributed to population changes. In the High SDI regions, the largest proportion of deaths and DALYs was due to epidemiological change (Figure S5 and Table S11).

Risk factors analysis

Globally, in the specific risk analysis of the GBD, smoking is positively correlated with the occurrence of PCa, with 3% of deaths and 3.5% of DALYs of PCa attributable to smoking in 2021. In terms of the SDI regions, the high-middle SDI regions had the largest proportion, and among the 21 GBD regions, Central Asia, East Asia, and Eastern Europe had the largest proportions (Fig. 7A). The risk factors of a diet low in milk and a diet low in calcium showed a negative correlation with deaths and DALYs from PCa. In the SDI regions, both risk factors had the largest negative correlation proportions in the low SDI regions. A diet low in milk had the largest negative correlation proportions in Central Sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and Western Sub-Saharan Africa. A diet low in calcium had the largest negative correlation proportions in Central Sub-Saharan Africa, Eastern Sub-Saharan Africa, Oceania, Southeast Asia, Southern Sub-Saharan Africa, and Western Sub-Saharan Africa (Fig. 5A). The overall situation in 1990 was similar to that in 2021, but the proportion attributable to smoking had increased significantly. The negative correlation proportions for a diet low in milk and a diet low in calcium also rose slightly (Fig. 5B).

Predictions at global levels

Based on the ARIMA forecasting model, we made predictions for the period from 2022 to 2040. For PCa, the ASPR is forecasted to be 266.23 by 2040. The ASIR is forecasted to reach 35.21 by 2040. The ASMR is forecasted to be 9.11 by 2040. The ASR of DALYs is forecasted to be 176.16 by 2040. For TCa, the ASPR is forecasted to be 20.63 by 2040. The ASIR is forecasted to reach 2.7 by 2040. The ASMR is forecasted to be 0.26 by 2040. The ASR of DALYs is forecasted to be 12.73 by 2040 (Figure S5, Table S12).

Discussion

Male cancers pose a substantial public health challenge worldwide, drawing significant research interest and attention due to its considerable disease burden. This study offers a thorough estimation of the prevalence, incidence, mortality, and DALYs associated with male cancers across 21 global regions, 204 countries and territories, various age groups, and risk factors. It provides a comprehensive analysis of the patterns and trends in global male cancers from 1990 to 2021, thereby elucidating the disease burden of male cancers. The key findings are as follows:

Overall overview

Firstly, in 2021, the global prevalence of PCa was estimated at 10,387,521 cases, with an incidence of 1,324,383 cases, 432,463 deaths. 8,141,561 DALYs. For TCa, the prevalence was 679,103 cases, with an incidence of 91,507 cases, 11,388 deaths, and 560,921 DALYs.

Regarding PCa, the United States topped the list for all four epidemiological indicators (Table 1). For TCa, United States also had the highest number of prevalence and incidence, but India had the highest deaths and DALYs (Table 1).

In 2021, the ASPR for global PCa was 260.05, the ASIR was 34.05, the ASMR was 12.63, and the ASR of DALYs was 217.83 (Table 1). From 1990 to 2021, the ASPR for PCa rose by 0.19, the ASIR increased by 0.04, the ASMR decreased − 0.23, and the ASR of DALYs declined by -0.21.

For TCa, the ASPR was 16.59, the ASIR was 2.24, the ASMR was 0.29, and the ASR of DALYs was 13.83 (Table 2). Over the period from 1990 to 2021, the ASPR for TCa increased by 0.66, the ASIR increased by 0.5, the ASMR slightly decreased by -0.14, and the ASR of DALYs decreased by -0.08.

The regions and countries with the highest ASPR and ASIR for PCa were High-income North America and the United States; ASMR and ASR of DALYs were Southern Sub-Saharan Africa and Grenada (Table 1; Fig. 1, Table S3). For TCa, the regions and countries with the highest ASPR, ASIR, and ASR of DALYs were Southern Latin America and the Monaco; ASMR were Southern Latin America and the Georgia (Table 1; Fig. 1). The regions and countries with the most significant increases in ASPR and ASIR were East Asia and China, and in ASMR and ASR of DALYs for PCa were Southern Sub-Saharan Africa and Grenada. In addition, Western Sub-Saharan Africa, the Caribbean, and Central Sub-Saharan Africa also grew faster, reflecting the rapid growth of PCa burdens in relatively less developed regions. For TCa, the regions and countries with the highest increases in ASPR and ASIR were Andean Latin America and China, and in ASMR and ASR of DALYs for TCa were Andean Latin America and Belize.

Age analysis

Secondly, in PCa, the burden is heavier in old age, with the highest peaks in the number of prevalence, incidence, deaths, and DALYs all after the age of 70 years, and the rate of prevalence, incidence, deaths, and DALYs all show an increase with age (Fig. 2). This result may be related to increasing age, prolonged exposure to pollutants, accumulation of errors during cell division and DNA replication, all of which lead to an increased likelihood of genetic mutations. These mutations affect the normal growth and differentiation of cells, thus increasing the risk of cancer21. And the immune system of the elderly is weakened, which makes the body less able to fight against abnormal cells. The aging immune system stimulates tumour growth by triggering harmful inflammation, making it one of the biggest risk factors for promoting PCa22. Meanwhile, changes in the levels of androgens, testosterone, and other hormones in the elderly may similarly influence PCa: one report suggests that excess androgens secreted in the body of the elderly can drive PCa growth, providing a rationale for the use of androgen deprivation as a first-line treatment for PCa. And the progression of PCa can be slowed after treatment with supraphysiologic levels of testosterone23. Thus, unstable levels of hormone production in the elderly may likewise add to their burden of PCa.

In TCa, the burden is heavier in middle-aged and young adults, with the highest peaks in the number of prevalence, incidence, deaths, and DALYs between the ages of 25–34 years. the rate of prevalence, incidence, and DALYs also all peaked between the ages of 25–34 years, with only the rate of deaths peaked at 95+ (Fig. 2). Current research has shown that TCa occurs primarily in the germ cells, i.e. sperm cells5. Young men between the ages of 25–34 years have more active germ cells, which are accompanied by more divisions occurring in the germ cells, and have a higher likelihood of cancerous transformation5,24. At the same time, sex hormones such as testosterone and androgens are at higher levels in young people, and these hormones all promote hyperfunctioning of the testes, which makes the germ cells more prone to divisions and cancer25,26. In addition, undescended testes (cryptorchidism) is a known risk factor for TCa5,26. This condition is more common in children and young adults (18–30 years old), where the patient’s testicles do not descend normally from the abdomen to the scrotum. This same condition can lead to abnormal testicular growth and cancer. Therefore, for young individuals, the Incidence, Prevalence, and DALYs of TCa impose a greater burden than in the elderly. However, considering the relatively low global incidence and better prognosis of TCa27, we recommend prioritizing and addressing factors related to cryptorchidism, promoting preventive screening, and early treatment to reduce the incidence of TCa in young people, thereby potentially decreasing its disease burden. For PCa, which is more prevalent in the elderly population, effective global control requires addressing the burden of an aging population: current research has identified aging as one of the largest risk factors for PCa28. Enhancing early screening, prevention, health promotion, and rational allocation of medical resources for male cancers in the elderly may offer a solution to this issue. Furthermore, given the potential of androgen deprivation therapy to slow the progression of PCa, this method might also be applicable in mitigating PCa-related deaths and the rate of DALYs.

Overall and future trends analysis

From 1990 to 2021, according to the development of the four epidemiologic indicators, in PCa, 1995 and 2013 and nearby years are the years with the most inflection points (Fig. 3). Around 1995, the worldwide popularization of PSA (prostate-specific antigen) testing began, and the diagnosis and treatment of PCa entered the ‘PSA era’, of which the popularization of PSA screening in Europe and the United States was the most widespread29. With the popularization of the test, a large number of PCa patients around the world were able to know their physical condition and take medical or health care measures, and the world’s health care expenditure for PCa increased significantly during this period30, which may have led to a continuous increase but slowdown of the prevalence and incidence data, and a decrease in the data of deaths and DALYs worldwide. DALYs data turned down. Meanwhile, the establishment of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995 has promoted the liberalization of global trade, the gradual improvement of people’s quality of life at the world level, the gradual increase in high-calorie diets, and the increase in the rate of obesity globally, and obesity is a known risk factor for PCa. Changes in dietary habits and lifestyle may also have contributed to the increased prevalence and incidence of PCa31. Finally, in the 1990s, international organizations such as the American Urological Association (AUA) and the European Association of Urology (EAU) have begun to develop and publish guidelines for the treatment of PCa. These guidelines provide recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of PCa. Some drugs such as anti-androgen drugs (e.g., bicalutamide or flutamide) have been used to treat PCa. Unsurprisingly, a variety of tools have been put into the treatment of PCa during that time period, and the deaths and DALYs of PCa have gone from up to down worldwide.

Around 2013, in response to the long-standing controversy over PSA screening guidelines, the AUA updated its guidelines for PSA screening, providing more precise screening recommendations, limiting the screening population, and reducing false positives and overdiagnosis32. At the same time, between 2010 and 2013, some new drugs for PCa were developed and put into use, such as Abiraterone and Enzalutamide, which can prolong the survival and improve the quality of life of PCa patients33. With the socio-economic development and lifestyle changes, the health awareness of the masses has gradually increased and improved, and the WHO has begun to carry out several global public health campaigns related to specific health issues or diseases throughout the year in 2013. More and more countries and regions have responded to the WHO’s call for health promotion campaigns to reduce the prevalence and incidence of cancer worldwide. Deaths and DALYs of PCa have continued to decline during this period, but both declines have slowed down due to the large size of the world’s population base.

The years 1995, 2020 and their vicinity are the years with the most inflection points of epidemiological indicators of TCa. Since 1995, with the rapid development of the world’s economic, social and cultural society, the trend of globalization has accelerated, the population’s awareness of their own health has gradually increased, and the health care industry has risen. During this period, the advancement and popularization of medical imaging technology, such as ultrasonography34, led to an increase in the detection rate of TCa5, and the prevalence and incidence of the TCa has increased year by year in the time since then. And because the difficulty of TCa treatment is usually not high, the cure rate and prognosis of patients are better, often in the early stage of cancer can be detected and prevalence and incidence rise at the same time26, TCa the deaths and DALYs are also gradually declining. 2020, the EAU updated and released the TCa guidelines, which provides the most up-to-date information for the diagnosis and treatment of TCa patients. During this 25-year period, the application of high-frequency ultrasound technology, the promotion of PET/CT examinations, and the globalization of serum tumor marker testing methods have led to more accurate detection of TCa which aids in early detection and treatment. Improvements in TCa guidelines and advances in diagnostic techniques have gradually led to a continued decline in all four epidemiologic indicators of TCa globally.

Moreover, the projections of ASPR, ASIR, ASMR and ASR of DALYs for 2022–2040 based on the ARIMA model. The continued increase in future prevalence and incidence especially in TCa proves that the disease burden faced by male cancers remains severe.

Regional variability analysis

Thirdly, the overall ASPR, ASIR for global as well as regional PCa and TCa for 1990–2021 shows a significant elevation in high-middle SDI regions (Fig. 4A-D). The graphs for countries and regions in 2021 are similar overall, but do not show a decrease in the high SDI region (Fig. 4E-H). ASMR and ASR of DALYs for global as well as regional PCa from 1990 to 2021 exhibit a double peak between the Low-Middle and Middle SDI regions and the High- Middle regions exhibit bimodal peaks. It rises with decreasing SDI in the Low SDI regions and falls with increasing SDI in the High SDI regions. In TCa it shows a peak between the Middle SDI and High-middle SDI regions. the Low SDI region does not change much but rises with SDI in the Low-middle and Middle SDI regions. the High-middle SDI and High SDI regions fall as SDI rises (Figure S4 A-D). 2021 graphs for states and regions are similar overall, but instead of rising as the SDI declines in the Low SDI region, they show a slight increase as the SDI rises, and the slight upward trend continues in the Low-middle SDI region (Figure S4E-H).

As for inequality, the study shows that over the period 1990–2021, a positive SII for PCa indicates that prevalence, incidence, deaths, and DALYs bear a greater burden in countries and regions with higher SDI, and that the values increase, with absolute inequality rising. In contrast, the CI of the four epidemiological indicators are positive, indicating that the indicators are more concentrated in high SDI regions; the CI as a whole all show a decrease, indicating that relative inequality has declined overall, but is still at a high level (Fig. 5 and Figure S5). Positive SII for all four of TCa epidemiological indicators also indicate that countries and regions with higher SDI bear a greater burden, with increasing values for prevalence and incidence, which indicate greater absolute inequality for these two indicators, but decreasing values for deaths and DALYs, which indicate lower absolute inequality for this indicator. Meanwhile, while the CI for Prevalence and incidence are positive, indicating that the indicators are more concentrated in high SDI areas, the values show a decrease, indicating a decrease in relative inequality, but inequality is still high. While deaths and DALYs changed from positive to negative, indicating that relative inequality shifted from high SDI areas to low SDI areas. However, the value is very small and the apparent relative inequality is very low.

For the regional analysis, prevalence and incidence were higher in High-middle SDI and High SDI regions, the first reason may be: in these higher SDI regions, total GDP and GDP per capita are higher, and there are usually better healthcare resources and higher health awareness, which may lead to more cases of prostate and TCa being detected and diagnosed. In terms of lifestyle habits people in high SDI areas may have more access to and consumption of high-fat, high-protein foods, leading to higher rates of obesity with the possibility of hypercholesterolemia, which has been associated with an increased incidence of PCa31. Finally high SDI areas may be accompanied by higher levels of industrialization, and residents may be exposed to more environmental pollutants and occupational carcinogens, which may likewise lead to increased incidence of male cancers in high SDI areas35. Concurrently, we observed that Deaths and DALYs appear to be higher in regions with low SDI, medium SDI, and high-medium SDI. This finding aligns with previous research conclusions, and our study further expands the scope of regions and disease types globally, offering new insights into the emergence of this phenomenon. Firstly, in regions with low SDI, medical resources are limited: these areas often have relatively underdeveloped economies. Current research indicates that the more constrained medical resources in these regions may lead to a lack of public health awareness and an inability to correctly recognize male cancers36, ultimately resulting in insufficient early detection, diagnosis, and treatment of male cancers, thereby increasing mortality and DALYs4,37. Secondly, these regions may lack effective PSA screening, TCa screening, and preventive promotion efforts for male cancers. Previous research has identified that cancer prevention and screening efforts are relatively weak in low SDI regions, such as sub-Saharan Africa and the Caribbean38. This may lead to male cancers being detected at later stages in these regions, with poorer prognoses, and diseases that could have been timely detected and cured, due to delayed treatment, result in higher mortality and DALYs. Lastly, on the socioeconomic level, the socioeconomic conditions in low SDI regions may lead to residents being more exposed to carcinogenic factors, or adopting unhealthy lifestyle habits, as well as a lack of adequate health education and preventive measures39. Limited medical resources, insufficient preventive screening efforts, and weak public health awareness, coupled with unhealthy diets and lifestyle habits, may contribute to this outcome.

The reasons for the decline in Deaths and DALYs in high SDI regions are numerous, primarily including advancements in medical standards in these areas: during the survey period, they had higher quality of care40, a greater number of specialized medical personnel, and more extensive universal health coverage, as well as a greater health awareness among the population. Additionally, these regions possess more effective health promotion and preventive measures that can reduce the incidence of male cancers, thereby indirectly reducing Deaths and DALYs. These factors work in concert to improve the efficiency of early diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of diseases, reducing the burden of disease41. Therefore, to address the regional disparities in Deaths and DALYs for male cancers, we recommend extensive health advocacy and early screening in low SDI regions, and providing more medical support and financial assistance to patients in these areas.

Risk factors analysis

Fifthly, the analysis of risk factors smokers showed a positive correlation with the occurrence of PCa, with the largest proportions in High-middle SDI, Central Asia, East Asia, and Eastern Europe. diet low in milk and diet low in calcium showed a negative correlation. Low SDI, Central Sub-Saharan Africa, Eastern Sub-Saharan Africa, Oceania, Southeast Asia, Southern Sub-Saharan Africa, and Western Sub-Saharan Africa showed a negative correlation between diet low in milk and diet low in calcium. The proportion is relatively large.

For smoking, it may increase the risk of PCa through several mechanisms. A variety of carcinogens contained in cigarettes may affect the DNA of cells, leading to genetic mutations and increasing the risk of cancer42. In addition, smoking may affect hormone levels, such as decreasing circulating testosterone levels23. This hormonal change may also be associated with increased aggressiveness of PCa23,31. In some medium to high SDI regions such as Central Asia, East Asia, and Eastern Europe, tobacco products may be relatively inexpensive, making it affordable for more people to start smoking as a result43. Also, smoking is considered a social habit or rite of passage in the socio-cultural context of these regions, such as China and Kazakhstan44, and the level of tobacco consumption in these countries is correspondingly high.

The reasons why low-calcium and low-dairy diets may reduce the risk of PCA are multiple. Some studies have noted that high calcium intake is associated with an increased risk of PCa, possibly because calcium affects hormone balance in the body, which in turn affects the growth and differentiation of prostate cells45. In addition, high intake of calcium, dairy products (which are rich in calcium) and vitamin D may lead to elevated blood levels of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), a hormone that promotes cell proliferation and inhibits apoptosis, which may increase the risk of prostate cell cancer46. It has also been shown that dairy intake is associated with an increase in inflammatory markers that may be linked to an increased risk of PCa47. In addition to calcium and vitamin D, dairy products may contain other components that affect PCa risk, such as saturated fatty acids. In Low SDI regions, such as Central Sub-Saharan Africa, Eastern Sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, etc., the limitations of local economy, culture, social customs, and many other habits lead to a lower intake of natural dairy products and calcium in the daily diet in these regions48, thus to some extent, the population in this region has a dietary advantage in avoiding PCa. Overall, a low-calcium and low-dairy diet may reduce the risk of PCa by decreasing IGF-1 levels, lowering inflammatory responses, reducing hormone exposure, and avoiding excessive intake of nutrients that may promote prostate cell proliferation. Previous studies have reported that risk factors associated with PCa and TCa include overeating, engaging in specific sports, long-term ionizing radiation, and environmental pollutants such as acrylamide and polyvinyl chloride49,50. In our study, we reviewed past research and, based on GBD data, refined the current risk factors for male cancers and observed the impact of smoking and specific dietary patterns. Here, we recommend avoiding smoking and adjusting the dietary structure high in calcium: appropriately reducing the consumption of dairy products and calcium intake in daily diets. Additionally, studies have shown that low-carbohydrate diets and ketogenic diets have significant effects in clinical trials for prostate cancer and may be more favored in the future51. Therefore, a comprehensive adoption of these measures may be beneficial in preventing the occurrence of male cancers. However, further research is needed to confirm these findings, and the combined impact of individual differences and lifestyle factors must be considered.

Limitations

The study also has limitations. First, the relevant male cancers also include the less common penile cancers, seminomas, etc., which are not included in the GBD database. Secondly, the GBD database primarily compiles data from national and regional reports and publications rather than direct national reports, which may lead to data completeness, timeliness, and quality issues, especially in low-income areas where there may be a lack of access to primary data, which may prevent GBD researchers from making estimates. In addition, furthermore, differences in disease management, including diagnosis, recording, and reporting, across countries and regions may affect results. And changes in diagnosis and testing protocols over time may affect the comparability of results may also affect the accuracy and comparability of data. With regard to the epidemiological change panel of the decomposition analysis, further analysis of specific indicators could not be carried out due to too many factors, lack of quantitative indicators and other factors. In addition, TCa of risk factors not included in the GBD database. Finally, our projections to 2040, although based on rigorous statistical modeling, may be affected by external factors.

Conclusion

Overall, male cancers continue to pose a significant global health challenge, imposing a heavy burden on healthcare systems. From 1990 to 2021, the ASPR and ASIR of male cancers have been on an upward trend. The rise in ASPR and ASIR for testicular cancer is particularly evident in the projections to 2040. Notably, the patterns and trends of this burden vary widely across different regions of the world. High SDI countries and regions exhibit higher ASPR and ASIR, while Low SDI countries and regions show higher ASMR and ASR of DALYs. Given the poor prognosis of male cancers in advanced stages, early diagnosis and intervention are crucial. Furthermore, considering the peak age of onset and various risk factors, research and policy formulation should focus on age- and region-specific interventions to address this issue effectively.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet, 390(10100), 1211–1259. (2017).

Sekhoacha, M. et al. Prostate Cancer Review: Genetics, diagnosis, Treatment options, and alternative approaches. Molecules 27(17). (2022).

Leslie, S. W., Soon-Sutton, T. L. & Skelton, W. P. Prostate Cancer, in StatPearls StatPearls Publishing (2024).

Xu, Y. et al. Time trends in the mortality of testicular cancer across the BRICS: An age-period-cohort analysis for the GBD 2019. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 12740 (2024).

Hayes-Lattin, B. & Nichols, C. R. Testicular cancer: A prototypic tumor of young adults. Semin Oncol. 36(5), 432–438 (2009).

Huang, J. et al. Worldwide distribution, risk factors, and temporal trends of testicular cancer incidence and mortality: A global analysis. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 5(5), 566–576 (2022).

Jankowska, M. Sexual functioning of testicular cancer survivors and their partners - a review of literature. Rep. Pract. Oncol. Radiother. 17(1), 54–62 (2011).

McHugh, D. J., Gleeson, J. P. & Feldman, D. R. Testicular cancer in 2023: Current status and recent progress. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74(2), 167–186 (2024).

Wang, Y. & Feng, W. Cancer-related psychosocial challenges. Gen. Psychiatr. 35(5), e100871 (2022).

Vynckier, P. et al. Systematic Review on the Cost Effectiveness of Prostate Cancer Screening in Europe (Eur Urol, 2024).

Sun, P. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of female cancers in women of child-bearing age, 1990–2021: Analysis of data from the global burden of disease study 2021. EClinicalMedicine 74, 102713 (2024).

Liang, Y. et al. Global burden and trends in pre- and post-menopausal gynecological cancer from 1990 to 2019, with projections to 2040: a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Surg., (2024).

Wang, L. et al. Prostate Cancer incidence and mortality: Global status and temporal trends in 89 countries from 2000 to 2019. Front. Public. Health. 10, 811044 (2022).

Bizuayehu, H. M. et al. Burden of 30 cancers among men: Global statistics in 2022 and projections for 2050 using population-based estimates. Cancer 130 (21), 3708–3723 (2024).

Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet, 403(10440), 2133–2161. (2024).

Global burden of 288 causes of death and life expectancy decomposition in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet, 403(10440), 2100–2132. (2024).

Tuo, Y. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of Thalassemia, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. EClinicalMedicine 72, 102619 (2024).

Yang, K. et al. Global burden of type 1 diabetes in adults aged 65 years and older, 1990–2019: Population based study. Bmj 385, e078432 (2024).

Das Gupta, P. A general method of decomposing a difference between two rates into several components. Demography 15(1), 99–112 (1978).

Foreman, K. J. et al. Forecasting life expectancy, years of life lost, and all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 250 causes of death: Reference and alternative scenarios for 2016-40 for 195 countries and territories. Lancet 392(10159), 2052–2090 (2018).

Li, M. et al. Trends in Cancer incidence and potential Associated factors in China. JAMA Netw. Open. 7(10), e2440381 (2024).

Hiam-Galvez, K. J., Allen, B. M. & Spitzer, M. H. Systemic immunity in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 21(6), 345–359 (2021).

Kumar, R. et al. The testosterone paradox of advanced prostate cancer: Mechanistic insights and clinical implications. Nat. Rev. Urol. 20(5), 265–278 (2023).

Li, W. et al. Global cancer statistics for adolescents and young adults: Population based study. J. Hematol. Oncol. 17(1), 99 (2024).

De Toni, L. et al. Testicular cancer: Genes, environment, hormones. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 10, 408 (2019).

Cheng, L. et al. Testicular cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 4(1), 29 (2018).

Znaor, A. et al. International variations and trends in testicular cancer incidence and mortality. Eur. Urol. 65(6), 1095–1106 (2014).

Freeland, J. et al. Aging of the progenitor cells that initiate prostate cancer. Cancer Lett. 515, 28–35 (2021).

Ilic, D. et al. Prostate cancer screening with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj 362, k3519 (2018).

Lin, S. et al. Disease burden of prostate cancer from 2014 to 2019 in the United States: Estimation from the global burden of Disease Study 2019 and Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Epidemiol. Health. 45, e2023038 (2023).

Coughlin, S. S. A review of social determinants of prostate cancer risk, stage, and survival. Prostate Int. 8(2), 49–54 (2020).

Georgiou, L. A. & Scarbrough, B. E. PSA screening for prostate cancer in the United States: 30 years of controversy. J. Public. Health Policy. 45(3), 552–561 (2024).

Bergengren, O. et al. 2022 update on prostate Cancer epidemiology and risk Factors-A systematic review. Eur. Urol. 84(2), 191–206 (2023).

Hayes, C. et al. Ultrasound in Global Health Radiology, in Radiology in Global Health: Strategies, Implementation, and Applications, D.J. Mollura, M.P. Culp, and M.P. Lungren, Editors. Springer International Publishing: Cham. pp. 127–140. (2019).

Bräuner, E. V. et al. Endocrine disrupting chemicals and risk of Testicular Cancer: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 106(12), e4834–e4860 (2021).

Kamaraju, S. et al. Cancer Prevention in Low-Resource countries: An overview of the opportunity. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book. 40, 1–12 (2020).

Zhou, X. et al. Trends in the global, regional, and national burden of testicular cancer from 1990 to 2019: An observational study with 30-year global data. Int. J. Surg. 110(8), 4633–4647 (2024).

Shastri, A. & Shastri, S. S. Cancer screening and prevention in low-resource settings. Nat. Rev. Cancer 14(12), 822–829 (2014).

Zhang, W. et al. Global Burden of Prostate Cancer and Association with Socioeconomic Status, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis from the global burden of disease study. J. Epidemiol. Glob Health 13(3), 407–421 (2023).

Nowroozi, A. et al. Global and regional quality of care index for prostate cancer: An analysis from the Global Burden of Disease study 1990–2019. Arch. Public. Health 81(1), 70 (2023).

Seibert, T. M. et al. Genetic risk prediction for prostate Cancer: Implications for early detection and prevention. Eur. Urol. 83(3), 241–248 (2023).

Gan, H. et al. Smoking: a leading factor for the death of chronic respiratory diseases derived from global burden of Disease Study 2019. BMC Pulm Med. 22(1), 149 (2022).

Nazar, G. P. et al. Impact of tobacco price and taxation on affordability and consumption of tobacco products in the South-East Asia Region: A systematic review. Tob. Induc. Dis. 19, 97 (2021).

Robb, J. H. Smoking as an anticipatory rite of passage: Some sociological hypotheses on health-related behaviour. Soc. Sci. Med. 23(6), 621–627 (1986).

Capiod, T. et al. Do dietary calcium and vitamin D matter in men with prostate cancer? Nat. Rev. Urol. 15(7), 453–461 (2018).

López-Plaza, B. et al. Milk and dairy product consumption and prostate Cancer risk and mortality: An overview of systematic reviews and Meta-analyses. Adv. Nutr. 10(suppl_2), S212–s223 (2019).

Silvestri, R. et al. Calcium signalling pathways in prostate cancer initiation and progression. Nat. Rev. Urol. 20(9), 524–543 (2023).

Bassetti, E. et al. Nutrient profiles of commercially produced complementary foods available in Cambodia, Indonesia and the Philippines. Public. Health Nutr. 25(10), 1–11 (2022).

Boyle, P. & Zaridze, D. G. Risk factors for prostate and testicular cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 29a(7), 1048–1055 (1993).

McGlynn, K. A. & Trabert, B. Adolescent and adult risk factors for testicular cancer. Nat. Rev. Urol. 9(6), 339–349 (2012).

Kaiser, A. et al. The evolving role of diet in prostate cancer risk and progression. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 31(3), 222–229 (2019).

Funding

This work was supported by Special Fund Project for Science and Technology Innovation Strategy of Guangdong Province (Grant number pdjh2023b0107), National College Students Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program (Grant number 202212121008), Shenzhen Fundamental Research Project (Grant number JCYJ20220530165014033), Medical Key Discipline of Longhua, Shenzhen (No. MKD202007090201), Medical Research Project of Shenzhen Longhua Medical Association (2023LHMA10), and Special Fund for Science and Technology Innovation in Longhua District, Shenzhen (11501A20240704D87ABF8).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z. Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing, Reviewing and Editing. P.W. Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing, Reviewing, and Editing.Z.J. Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing, Reviewing, and Editing. Z.Z. Writing and Editing. J.W. Conceptualization, Reviewing, and Editing.H.L. Conceptualization, Reviewing, and Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Wang, P., Jia, Z. et al. Global burden and risk factors of male cancers from 1990 to 2021, with forecasts to 2040. Sci Rep 15, 5123 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88392-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88392-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Predicting high-grade clinically significant prostate cancer

Abdominal Radiology (2026)

-

Global, regional, and national burden and trends of prostate cancer in elderly from 1990 to 2021: results from global burden of disease 2021

World Journal of Surgical Oncology (2025)