Abstract

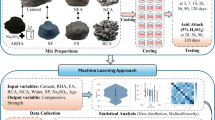

The environmental issues in the construction industry have garnered considerable attention in numerous studies. Ecologically sustainable green concrete addresses environmental challenges in the construction industry. This study investigates the impact of multi-walled carbon nanotubes (0–0.20%) in rice husk ash (15%) concrete to replace Portland cement. The mechanical and durability properties of four concrete mixtures were analysed. Adding 0.1% multi-walled carbon nanotubes and 15% rice husk ash yielded satisfactory results, significantly improving durability compared to concrete without multi-walled carbon nanotubes. With the addition of 0.1–0.2% multi-walled carbon nanotubes, the density and elastic modulus increased, the 28-d sorptivity decreased by 4.64–28.76%. The resistance ability of 111-d mass loss and compressive strength loss increased by 50.93–61.71% and 25.28–48.47% under sulphate attack, respectively. The resistance ability of mass loss increased by 3.7–35.97% under acid attack. And 120-d drying shrinkage resistance improved by 3.08–9.23%. The predicted and experimental results were compared using the Sakata, GL 2000, B3, ACI 209, and CEB-FIP models. Sakata and B3 provided the most accurate early-stage and long-term drying shrinkages with variation coefficients of 0.13–0.33 and 0–0.05, respectively. Moreover, the sustainability of rice husk ash concrete containing multi-walled carbon nanotubes was evaluated, and its environmental friendliness was confirmed. Thus, the viability of multi-walled carbon nanotubes in rice husk ash sustainable concrete significantly contributes to sustainable construction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

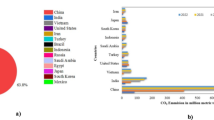

Cement is an extensively used raw material in the construction industry. In 2022, cement emitted approximately 2.42 Gt of CO2, accounting for approximately 8% of global CO2 emissions1. Thus, cement has emerged as a significant contributor to environmental challenges faced by the construction sector. Researchers have attempted solutions to environmental problems using alternatives, such as lightweight concrete, recycled aggregate concrete, geopolymer concrete, and waste-utilized concrete2,3,4,5,6. Among them, waste-utilised concrete not only alleviates environmental problems caused by the construction industry but also addresses environmental issues due to unreasonable waste treatment, such as dumping, incineration, or direct release into waterways, thereby achieving a win-win effect. Globally, scholars are focused on using industrial and agricultural wastes including ceramic waste powder, olive waste ash, rice husk ash (RHA), bagasse ash, and corncob ash as supplementary cementitious materials4,7,8,9,10. Using agricultural waste minimises negative impacts on the environment and helps address issues within the construction industry.

RHA, a typical supplementary cementitious material, has been extensively investigated owing to its high amorphous silica content and exceptional pozzolanic characteristics. The pozzolanic characteristics of RHA are intricately linked to temperature, environment, and combustion duration. The optimal temperature range for burning RHA is 500–700°C11. When the combustion temperature is extremely high, exceeding 700 °C, the amorphous silica in RHA begins to crystallise12. Additionally, the duration and technique of grinding RHA significantly affect its fineness, thereby influencing its pozzolanic activity13. The addition of RHA to concrete can improve concrete durability14. Ambedkar et al.15 reported a significant decrease in water absorption property of concrete containing 20% RHA compared to that without RHA. Rodríguez de Further, the incorporation of RHA improves concrete durability by increasing its chloride and acid resistances. Owing to the combined influence of calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel and filler effects of RHA, concrete becomes more compact and blocks the pathway for chloride ions and acid solutions to seep into it16,17.

Owing to their excellent properties, nanoparticles (NPs) such as nano-SiO2, nano-Al2O3, nano-Fe2O3, nano-TiO2, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), carbon nanofibers, and graphene oxide (GO) have been used to enhance the mechanical properties and durability of concrete6,18,19,20,21,22,23. The effects of nanomaterials on the mechanical and durability properties of cementitious materials can be attributed to the following aspects: (1) nucleation effect: nanomaterials form nucleation sites that promote pozzolanic reactions; (2) filler effects: small nanomaterials effectively fill matrix pores of cementitious composites; (3) bridging effect: nanomaterials with high aspect ratios such as CNTs effectively bridge microgaps in the cement matrix, thereby inhibiting microcrack generation and development; (4) pozzolanic reactions: nanomaterials such as nano SiO2 exhibit pozzolanic properties, which on reaction with hydration product Ca(OH)2, generate high-strength C-S-H gels24,25,26,27,28. Studies on NP applications in conjunction with RHA to form cementitious composites have focused on nano-SiO2, GO, nano-Al2O3, and nano-TiO229,30,31,32. Avudaiappan et al.33 reported that adding 1% nano-SiO2 and 10% RHA resulted in an increase in the 28-d compressive strength from 24.5 to 31.3 MPa. 28-d flexural strength from 3.71 to 4.2 MPa, and 28-d splitting tensile strength from 2.56 to 3.28 MPa when compared to the strengths of control specimens without RHA and nano-SiO2. The addition of RHA and widely distributed nano-SiO2 reduced concrete porosity from 0.1784 to 0.0693% and average pore radius from 18.8447 μm to 17.0092 μm. Priya et al.34 observed the synergistic interaction of GO and RHA while generating supplementary C-S-H gel inside cement matrix, which, along with the filler effect of GO, densified the concrete microstructure. The addition of 0.075% GO to concrete, with RHA substituting 10% of cement, optimised its mechanical properties and durability. In comparison to the control specimen without GO and RHA, the 28-d compressive strength, 28-d splitting tensile strength, and 28-d flexural strength increased by 17.7%, 34.21%, and 26.8%, respectively, while water absorption property and sorptivity decreased by 41.7% and 23.3%, respectively. Meddah et al.35 stated that the incorporation of 3% nano-Al2O3 and 10% RHA resulted in a dense internal structure of concrete, achieving optimal performance. Compared to the control specimen without RHA and nano-Al2O3, the 28-d compressive strength and chloride penetration resistance of the synthesised concrete improved by 35% and 19%, respectively. Praveenkumar et al.36 deduced that an incorporation of 3% nano-TiO2 was optimal for concrete containing 10% RHA, resulting in significant mechanical property and durability enhancement. The improvement was attributed to the synergistic effects of nucleation and filler properties of nano-TiO2, along with the pozzolanic reaction of RHA, which collectively reduced porosity and densified the internal structure of concrete.

Microcrack formation is the primary cause of concrete failure. Compared to other nanomaterials, the incorporation of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) significantly delays microcrack formation and progression in cementitious materials37. Adding CNTs enhances the internal structure of cementitious composites, consequently improving their mechanical properties and durability38. CNTs have been widely investigated owing to their excellent mechanical, electrical, and thermal properties39. Discovered in 1991, CNTs are seamless cylinders formed by carbon allotropes of lengths ranging from micrometres to centimetres, exhibiting a high aspect ratio40,41. CNTs are classified into two categories according to the number of graphene layers: single-walled CNTs (SWCNTs) of diameters less than 2 nm, and multi-walled CNTs (MWCNTs) of diameters between 5 and 100 nm42. CNTs exhibit remarkable physical properties, with tensile strength reaching 150 GPa and elastic modulus of approximately 1.47 TPa43,44. Improvements in the mechanical properties and durability of cement-based binders by CNTs is primarily because of nucleation, filler, and bridging effects3,45,46. Danoglidis et al.47 reported that the flexural strength and Young’s modulus of mortar with 0.1% MWCNTs improved by approximately two-fold. Konsta-Gdoutos et al.48 stated that small quantities of efficiently dispersed MWCNTs effectively increased the stiffness of cementitious materials, with the increased strength being evident when longer MWCNTs were used. According to Carriço et al.49 MWCNTs enhanced the strength and long-term performance of concrete, exhibiting a significant decrease in chloride penetration compared to that in concrete without MWCNTs. A maximum reduction of 12% in the proliferation coefficient of chlorides was observed. Alafogianni et al.50 observed reduction in capillary pore size on adding CNTs, resulting in a more compact internal structure of concrete with enhanced resistance to freezing51. Combining CNTs with other materials in cementitious composites significantly enhances their performance. According to Jongvivatsakul et al.52, CNT-reinforced epoxy significantly improved the interfacial fracture energy between a carbon fibre-reinforced polymer and concrete. The synergistic utilisation of CNTs and steel fibres significantly enhance the mechanical properties of concrete23. Furthermore, the simultaneous use of MWCNTs and polypropylene fibres enhance the fire resistance property of mortar53.

To date, no research has focused on the use of CNTs in RHA concrete. The synergistic effect of RHA (exhibiting significant pozzolanic reactivity) and CNTs (known for their superior physical properties in concrete) has not been investigated. This study aims to utilise RHA and CNTs as alternatives to Portland cement by thoroughly analysing the impact of MWCNTs on the mechanical properties and long-term durability of RHA concrete when blended together. A comparative study is presented considering the density, slump, sorptivity, sulphate and acid resistance, drying shrinkage, sustainability, and morphology of the synthesised concrete and a control group of RHA concrete without MWCNTs. Additionally, the RHA concrete incorporated with CNTs is evaluated for its impact on the sustainability. Finally, a mixed-proportion scheme beneficial to the environment and efficient in increasing the durability of RHA concrete is proposed. This study contributes to sustainable construction by promoting the application of sustainable high-performance RHA concrete.

Methods

Materials

Cement

Ordinary Portland cement (OPC) type 42.5 was used as the binder. The OPC complied with Chinese cement standard GB 175-200754. The physical properties of the cement are listed in Table 1.

Aggregates

The coarse aggregate comprised 5–20 mm crushed limestone particles. The fine aggregate used was locally sourced river sand (Henan, China), which had a fineness modulus of 2.9 and a maximum nominal size of 4.75 mm. According to the Chinese standard for crushed and pebbled stones used in construction (GB/T 14685)55, the physical properties of the aggregates are listed in Table 2.

RHA

Rice husks were obtained from Xuzhou, China. RHA was produced by burning rice husks in a furnace for 60 min at 800 °C. The chemical properties of RHA are shown in Table 3. And Fig. 1 shows the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of RHA. As can be seen from Fig. 1, RHA exhibits porosity and irregular particle morphology.

CNTs

MWCNTs produced by Tanxi Technology Co., Ltd. (Shenzhen, China) were > 97.5% pure. Figure 2 shows the SEM images of MWCNTs. Figure 2 distinctly illustrates that the surface of MWCNTs exhibits a pronounced tubular form and is interwoven with one another. The average diameter, length, and specific surface area of the MWCNTs were 7–15 nm, 5–15 μm, and 286.3 m2/g, respectively.

Superplasticizer

Polycarboxylate ether superplasticiser (PCE) is a high-efficiency water reducer and acts as a surfactant, playing a positive role in CNTs dispersion56. The PCE used in this study had a water reduction rate of 28% and was used in all mixtures.

Methodology of work

Adjustment of superplasticizer dosages

According to GB 50010-2010, the design strength of Grade 50 concrete was considered to investigate the effect of MWCNTs on RHA concrete57. To ensure optimal workability of concrete in real-world applications, the slump used was no less than 180 mm. Subsequently, in accordance with the specifications for the mix proportion design of conventional concrete (JGJ 55-2011)58, the water–cement ratio was established at 0.32, with a cement dose of 528.2 kg/m3. The concrete was trial-mixed with 1.5%, 2.0%, and 2.5% PCE relative to the cement weight, and the slump test was conducted in accordance with GB/T 50,080–201659. The test results are shown in Fig. 3. Finally, a PCE incorporation of 2.5% was confirmed, and the compressive strength of the 100 mm cubic specimen was tested according to GB/T 50,081–201960. The results are summarised in Table 4.

Preparation of CNTs solution

Owing to the presence of van der Waals forces, CNTs exhibited a propensity to aggregate into clusters61. Agglomerated CNTs negatively affected cementitious composites, leading to a reduction in their mechanical and durability properties62,63. Several methods exist to overcome CNT agglomeration. However, no unified method or standard is available. Ultrasonication, ball milling, and surfactants are commonly used27,64,65,66. Ball milling uses a planetary ball mill to generate a substantial shear stress through the impact of tiny balls, resulting in a dispersive effect on the CNTs. The efficacy of CNTs dispersion is closely related to the ball diameter, rotational velocity, and grinding67. The ball-milling method is relatively simple; however, its disadvantages are evident. Ball milling reduces the length of CNTs, affects their bridging effect, and reduces the gain effect of CNTs on cementitious composites68. In the ultrasonic dispersion method, when ultrasonic waves propagate in the solution, their cavitation effect can cause the cavitation bubbles attached to MWCNTs in the solution to collapse, generating strong local energy shock waves and high temperatures to disperse the MWCNTs, thereby achieving dispersion of the MWCNTs69. The dispersion effect of ultrasonication is related to numerous factors such as duration and energy. Too long a duration and too high an energy weaken the tube length of CNTs and affect the dispersion effect66. When the ultrasonication treatment is stopped, the CNTs re-agglomerate owing to the existence of van der Waals forces. The combined use of the surfactant unzipping mechanism and ultrasonic treatment ensures the stability of the dispersed solution70. Therefore, the combined use of ultrasonication and surfactants is preferred. Table 5 summarises the dispersion methods of CNTs used in recent studies.

In this study, a dispersion method combining ultrasound and surfactants (PCE) was used. Figure 4 shows the dispersion process of MWCNTs. The Scientz-750 F ultrasonic disperser model (shown in the Fig. 4) was used to enhance the dispersion effectiveness of the MWCNTs and had a power output of 750 W. Water and PCE were first mixed, and 5 g of MWCNTs powder was added to a beaker containing 400 mL of dispersant to prepare an MWCNTs suspension with a concentration of 12.5 g/L. The aqueous solution of the MWCNTs and PCE was subjected to ultrasonication for 30 min, with a 3-s on and 3-s off cycle. The cold water was replenished at 10-min intervals to maintain it at room temperature. In the preparation of the test specimens, the necessary water content was calculated by subtracting the volumes of the MWCNTs and PCE solution water from the total water requirement.

Mix proportions

In this study, RHA and CNTs were used as partial replacements for cement. Tables 5 and 6 summarise the literature published over the past five years based on the synthesis method of CNTs, types of CNTs, physical properties of CNTs, dispersion method of CNTs, combustion duration and temperature of RHA, and chemical properties of RHA. From Table 6, the optimal replacement rate of RHA for cement is directly related to its combustion duration and temperature. The chemical composition of RHA obtained by different combustion methods is different, but all are above 70%, belonging to pozzolanic materials, and the optimal replacement rate is mostly within the range of 10–20%. From Table 5, the diameter and length of MWCNTs used in most experiments are within the range of 6–30 nm and 3–30 μm, and the optimal doping amount in most studies is within 0.08–0.2%.

The physical and chemical properties of the CNTs and RHA used in this study were based on the values reported in previous research. Considering that this study used nanomaterials to improve the comprehensive performance of RHA sustainable concrete and reduce the environmental impact of concrete in the construction industry, when choosing the replacement rate of RHA to cement, a larger value was selected. Consequently, the mixing ratio of RHA was set to 15%. The addition amount of CNTs was selected as 0.1–0.2%. Four trial mix proportions, R15C0, R15C10, R15C15, and R15C20, were prepared by adding 0.00%, 0.10%, 0.15%, and 0.20% (by cement weight) MWCNTs, respectively. The mix proportions used in this study are listed in Table 7.

Mixing method

To ensure uniform gelation of the nanomaterials with RHA, a mixing procedure was followed, as reported by Miyandehi et al.86. Uniform mixing of the cement particles and RHA was ensured. Then, the nanomaterials were introduced. The mixing step ensured a uniform distribution of nanomaterials in the cementitious composites. In this study, the aggregates were introduced into the mixer and blended for 2 min. The mixture was mixed with cement and RHA, followed by dry mixing. Subsequently, the MWCNTs solution containing the PCE and remaining water was introduced into the mixer and blended for 5 min before performing a slump test to assess the workability of the concrete.

Test method

Fresh and mechanical properties test

Once the concrete samples were removed from the moulds, they were subjected to conventional curing conditions at 20 ± 2 °C and a relative humidity exceeding 95% until they reached a specified age. Twelve rectangular prisms with dimensions of 150 × 150 × 300 mm were created to measure the elastic modulus. The concrete slump and elastic modulus tests were based on GB/T 50080-2016 and GB/T 50081-2019, respectively59,60.

Sorptivity test

A sorptivity test was conducted to test the absorption property of concrete under the influence of capillary action. The sorptivity test complied with ASTM C-1585, and the specimens were cylindrical with a diameter of 100 mm and height of 50 mm. To ensure dry specimens, the specimens were placed in an oven at ± 105 °C for 24 h. The specimens were immersed in water and placed on a steel rod up to a depth of 5 mm. Mass was measured at specified time intervals (5, 60, 120, and 240 min). The equation used for the sorptivity test is as follows:

where I is the cumulative water absorption per unit surface area (mm), S is the sorptivity (mm/min0.5), and t is the time of water absorption (min).

Sulphate resistance test

Twelve cubes of concrete samples measuring 100 mm were evaluated for sulphate resistance. The samples were cured in water for 28 d. The samples were then submerged in a solution containing 5% MgSO4 for 30 d. Subsequently, they were air-dried for an additional 7 d. This cycle was repeated thrice, and the weight loss and compressive strength were assessed after each cycle.

Acid resistance test

The acid resistance test was performed by subjecting a 100 mm cube to water curing for 28 d. The sample was submerged in a 3% HCl solution at pH 2 for 75 d. Subsequently, the specimens were air dried for 7 d. To maintain a pH of approximately 2, the solution was checked every two weeks; when necessary, the solution was added. Mass and compressive strength were assessed after 75 d. The concrete corrosion resistance coefficient K was used as an indicator to determine the corrosion resistance of the concrete. The calculation equation is as follows:

where \({f}_{n}\) (MPa) is the cube compressive strength of the concrete when the corrosion age is n days, \({f}_{o}\) (MPa) is the cube compressive strength of the concrete before corrosion.

Drying shrinkage test

Malaysia—in the tropical region—has an average temperature of 30 °C. Kuala Lumpur, the capital city, has daytime surface temperatures over 40 °C in the dry season87,88. Therefore, investigating the drying shrinkage of RHA concrete in severe circumstances (at 60 °C) was necessary. Twelve prism concrete samples with dimensions of 100 × 100 × 300 mm were used for the drying shrinkage test, following the ASTM C531-85 standard. The concrete prism samples were subjected to standard curing for 7 d. After 7 d of curing, the prism sample was dried in an oven (at 60 °C). All concrete samples were treated similarly. The length of the concrete prism sample was measured at regular intervals for 120 d. Drying shrinkage was calculated using the following equation:

where \({\varepsilon}_{st}\) is the drying shrinkage rate of the specimen, t is the time since the initial length measurement, \({L}_{b}\) is the measurement gauge length of the specimen (mm), \({L}_{0}\) is the initial specimen length (mm), and \({L}_{t}\) is the length measured at t (mm).

Five prediction models were applied to the drying shrinkage (ACI 209, CEB-FIP, B3, GL 2000, and Sakata (SAK)) in this study. Coefficient of variation (CV) was used to evaluate the accuracy of the prediction models.

Environment evaluation test

CO2 emissions (CE) and embodied CO2 index (CI) were calculated to evaluate the environmental impact of incorporating MWCNTs into RHA concrete. CE is calculated by multiplying the CE intensity (\({\text{E}\text{C}}_{i})\) by the mass of components \({(m}_{i})\). CI was used to evaluate the relationship between mechanical properties and environmental impact. The experimental values of the mechanical properties (compressive, flexural, and splitting tensile strengths) of RHA concrete blended with MWCNTs were obtained from Jing et al.89 The equation used is as follows:

where σ represents the mechanical properties (compressive, splitting tensile, and flexural strengths).

Cost efficiency evaluation test

CEF was used to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of RHA concrete with MWCNTs. The prices of various raw materials were derived from local prices in China. The unit price was in US dollar. The price of cement was $0.1 per kg, the price of coarse aggregate and fine aggregate was $0.01 per kg, and the price of PCE was $0.66 per kg. As CNTs were mainly supplied to manufacturers, the cost was high when purchased separately by the laboratory. Considering the large-scale use of high-performance RHA concrete in the future, the price of CNTs in this experiment was determined based on the sales unit price of CNTs presented in the 2023 annual report of Jiangsu Cnano Technology Co., Ltd., a Chinese CNTs manufacturer, which was $14.89 per kg90. The calculation equation for CEF is as follows:

where σ represents the mechanical property (i.e. compressive strength, splitting tensile strength, and flexural strength), and C is the cost of RHA concrete blended with MWCNTs.

Results and discussion

Slump

Figure 5 shows the slump values of various RHA concrete mixtures containing different percentages of MWCNTs. The maximum slump value of RHA concrete without MWCNTs (R15C0) was 220 mm. The value decreased with increase in MWCNT concentration. Higher concentrations of MWCNTs decreased the workability of the mixture compared to that of R15C0, with a maximum reduction of 29.5%. For RHA concrete mixtures containing 0.10 c-wt%, 0.15 c-wt%, and 0.20 c-wt% MWCNTs, the slump value reduced by 9.1%, 20.5%, and 29.5%, respectively. When the quantity of MWCNTs was greater than 0.10%, the slump value decreased. However, all mixtures were workable owing to the large specific surface area of MWCNTs and the porous structure of RHA, which increased the friction between particles by absorbing water that would otherwise have functioned as a lubricant13,41.

Density

Figure 6 illustrates the density values of the RHA concrete mixtures in different conditions: demoulded, air-dried at 28 d, saturated at 28 d and oven-dried at 28 d. The densities exhibited an initial increase followed by a subsequent decrease when a small quantity of MWCNTs was incorporated into the RHA concrete. Regarding the oven-dried density at 28 d, the MWCNTs proportion in the RHA concrete was increased from 0.10 to 0.20%, and the density initially increased and reached its maximum value at 0.10%. The increase in oven-dried density was attributed to the MWCNTs serving as fillers in the RHA concrete. The increase was attributed to MWCNTs serving as fillers in RHA concrete. Similar results have been reported in the literature, the density of fly ash mortar containing CNTs was considerably higher at 28 d91. According to Nowak and Rakoczy, normal-weight concrete densities range between 2240 and 2400 kg/m3. Therefore, RHA concrete with MWCNTs can be considered normal-weight concrete92.

However, as the percentage of MWCNTs exceeded 0.10%, the density of the RHA concrete decreased, possibly because of the agglomeration caused by the high MWCNT concentration. Furthermore, the density of the concrete with 0.20% MWCNTs was higher than that of R15C0. Thus, incorporating MWCNTs contributed positively to increasing the RHA concrete density.

Elastic modulus

Figure 7 illustrates the values of elastic modulus for RHA concrete mixtures containing various percentages of MWCNTs. The elastic moduli of R15C0, R15C10, R15C15, and R15C20 were measured as 38.4, 38.8, 36.8, and 35.6 GPa, respectively. From Fig. 7, the value of elastic modulus decreased after peaking when 0.1% MWCNT was added to the concrete. The addition of 0.15% and 0.20% MWCNTs reduced the elastic moduli by approximately 4.2% and 7.3%, respectively, compared to those of R15C0. The decrease in elastic modulus was attributed to the reaggregation of CNTs in the cement matrix owing to van der Waals forces. This process increased porosity and initiated internal defects, ultimately decreasing the mechanical properties of concrete64. Normal-weight concrete exhibits an elastic modulus of 14–41 GPa93. Therefore, the elastic moduli of all RHA concrete mixtures with MWCNTs were within the range of elastic modulus of normal-weight concrete.

Table 8 presents the predicted and experimental values of 28-d elastic modulus for comparative analysis. The 28-d compressive strengths of R15C0, R15C10, R15C15, and R15C20 were 71.9, 77.7, 59.6, and 59.2 MPa, respectively, as recorded by Jing et al.89 For RHA concrete without MWCNTs, all prediction models underestimated the elastic modulus. With the addition of 0.1% MWCNTs, the estimation of elastic modulus improved. However, as the concentration of MWCNTs increased, the accuracy of the prediction model decreased, and the elastic modulus was generally underestimated. Excessive incorporation of MWCNTs may have this outcome. The agglomeration of MWCNTs created internal void defects in the concrete, significantly reducing compressive strength94. However, the nucleation and bridging effects of unagglomerated MWCNTs accelerated the formation of high-stiffness C-S-H, which results in the decrease rate of elastic modulus being lower than the decrease rate of compressive strength95. With 0.2% MWCNTs, the 28-d compressive strength and elastic modulus values of RHA concrete decreased by 17.66% and 7.29%, respectively. Predictions from BS8110 aligned well with experimental results, showing errors below 5%. The prediction accuracy for R15C15 was approximately 100%. Conversely, the prediction errors of ACI 318 were within the acceptable range (< 7%), while other models showed high errors, a maximum of 31%, making them unsuitable for predicting the elastic modulus of RHA concrete with MWCNTs.

where \(E\) is the elastic modulus (GPa), \(w\) is the air-dry density (kg/m3), and \({f}_{cu}\) and \({f}_{cy}\) are the compressive strengths of cubic and cylindrical MWCNTs (MPa), respectively.

Sorptivity

Sorptivity is a crucial metric for assessing the durability of concrete by measuring the degree of water absorption in concrete specimens through capillary action100. Figure 8 shows the sorptivity values of all mixtures on day 28. With the increase in MWCNTs concentration, the sorptivity of RHA concrete exhibited a downward trend. The sorptivity of RHA concrete mixtures with 0.1%, 0.15%, and 0.2% MWNCTs decreased by 28.76%, 18.87%, and 4.64%, respectively, compared to that of the control mixture without MWCNTs. The decreasing trend was attributed to the synergistic filling effect of CNTs and the pozzolanic reaction in RHA concrete, forming C-S-H gel, which effectively reduced pore structure inside the concrete, refined pore size, reduced interconnection between capillaries, and densified concrete microstructure, thereby decreasing its sorptivity18,101. Similar results have been reported by an existing study50, where the addition of a small amount of CNTs significantly affected the pore structure of cement-based materials, thereby affecting water transport. From Fig. 8, the capacity to enhance the resistance ability of sorptivity of RHA concrete progressively reduced with increase in MWCNTs concentration owing to the van der Waals force between the MWCNT particles. During cement hydration, high concentrations of MWCNTs re-agglomerated, and the agglomerated MWCNTs wrapped cement particles, inhibiting hydration reaction and forming pores inside the concrete64,102.

Sulphate attack

Table 9 lists the loss in weight of all RHA concrete mixtures after being exposed to 5% MgSO4 solution thrice. A consistent decrease in specimen weight over time was observed. MWCNTs significantly enhanced the resistance of RHA concrete against weight loss. After three cycles of sulphate attack (111 d), the RHA concrete specimens comprising 0.1–0.2% MWCNTs recorded weight loss decreased by 50.93–61.71% compared to that of specimen without MWCNTs.

Figure 9 illustrates the values of loss in compressive strength of RHA concrete with MWCNTs when exposed to 5% MgSO4 solution. With the addition of MWCNTs, the resistance to sulphate significantly improved. The losses in compressive strength of R15C0, R15C10, R15C15, and R15C20 were 24.71%, 12.73%, 15.44%, and 18.47%, respectively, at the end of three cycles of sulphate attack (111 d). The value of loss in compressive strength of concrete initially decreased and subsequently increased. Nevertheless, even with an increase in MWCNTs concentration to 0.2%, the loss in compressive strength of R15C20 was less than that of R15C0. After three cycles of sulphate attack, the loss in compressive strength of concrete with 0.1–0.2% MWCNTs decreased from 25.28 to 48.47% compared to that of the control specimen. Furthermore, R15C10 exhibited the least compressive strength loss, which decreased by 50.86%, 51.46%, and 48.47% when attacked with sulphate at 37, 74, and 111 d, respectively, compared to that in R15C0.

R15C10 exhibited the optimal sulphate resistance. Reduction of loss in weight and compressive strength was attributed to the effective filling of pores within the specimen by a certain quantity of MWCNTs. Filling effect of CNTs reduced the number of pores, increased density, and hindered the intrusion of MgSO4 solution103. Nevertheless, the loss in weight and strength of the specimens increased with the MWCNTs concentration. The observed values were lesser than those of R15C0. Sarvandani et al.27 reported that the addition of MWCNTs improved the resistance of concrete to sulphate attack. MWCNTs effectively delayed surface spalling in concrete. The addition of 0.2% MWCNTs reduced the loss in compressive strength of concrete when exposed to the sulphate solution by 13.37%. Varisha et al.104 studied changes in length and losses in weight of cement mortar doped with MWCNTs and nanosilica when exposed to MgSO4 solution. With the addition of MWCNTs and nano silica to the cement mortar, the value of length expansion significantly reduced, while the 120-d loss in weight reduced by 29% when compared to the control group. The reduction was attributed to the addition of MWCNTs and nanosilica, which densified the cement matrix and prevented the invasion of \({{\text{S}\text{O}}_{4}}^{2-}\).

Acid attack

Figure 10 shows the value of loss in mass of all mixtures after exposure to 3% HCl solution at pH 2. The loss in mass of the RHA concrete specimens decreased significantly with the addition of MWCNTs. Particularly, with the addition of 0.10% MWNCTs, the resistance of RHA concrete to loss in mass increased by 35.97% compared to that of the control specimens. However, the improvement was weakened with increasing MWCNTs concentration. The addition of 0.15% and 0.20% MWCNTs increased the resistance of the specimens to loss in mass by 26.46% and 3.7%, respectively, compared to that of the control specimens.

Figure 11 shows the plot of corrosion acid resistance factor for all mixtures after exposure to 3% HCl solution at pH 2. After 75 d of immersion, the HCl resistance coefficient was recorded as 0.57. With the addition of MWCNTs, the resistance factor significantly improved. Adding 0.1% and 0.15% MWCNTs increased the HCl resistance factor of the specimens by 14.72% and 5.44%, respectively, compared to that of the control specimen.

The addition of MWCNTs improved the resistance of RHA concrete to HCl owing to the filling effect of MWCNTs, which effectively reduced internal pores in RHA concrete and diminished invasion channels of HCl95. The results from sorptivity test verified this hypothesis. However, the effect of MWCNTs on improving the resistance of RHA concrete to HCl erosion depended on the degree of MWCNT dispersion. Furthermore, agglomerated MWCNTs reduced the resistance of RHA concrete to HCl erosion.

Drying shrinkage

Experimental results

Figure 12 depicts the development of drying shrinkage in RHA concrete with varying MWCNT concentration for up to 120 d. In a dry environment at 60 °C, the drying shrinkage in RHA concrete developed rapidly. A predominant drying shrinkage in RHA concrete without MWCNTs occurred within the initial 7 d, accounting for 88.46% of the total shrinkage observed at 120 d. After the seventh day, the drying shrinkage slope reached a steady state, attributable to the elevated temperatures expediting the cement hydration process and the pozzolanic reaction of RHA, resulting in the formation of more hydration products during the initial hydration phase and hastening of drying shrinkage105,106. However, the drying conditions at 60 °C increased the possibility of microcrack and macrocrack formation, resulting in increased porosity107. Simultaneously, as the temperature raised, the evaporation and expulsion of water from the pores was expedited, resulting in a rapid rise in pore pressure. As water vapor escapes, pore pressure diminished, and the shrinkage of cementitious materials accelerated108,109.

Figure 13 illustrates the initial stage of drying shrinkage in RHA concrete with various MWCNT concentrations before 28 d. Adding 0.1% MWCNTs considerably enhanced the drying shrinkage resistance of RHA concrete. Drying shrinkage in R15C10 decreased by 63.51%, 36.7%, 25.22%, and 16.8% at 1, 3, 7, and 28 d, respectively, compared to that in R15C0. With increasing MWCNTs concentration, the improvement of drying shrinkage in RHA concrete weakened. However, drying shrinkage in R15C15 and R15C20 was lower than that in R15C0. Drying shrinkage in RHA concrete with 0.15% and 0.2% MWCNTs reduced by 5.88% and 5.04%, respectively, at 28 d compared to that in R15C0. From Fig. 12, MWCNTs improved long-term drying shrinkage in RHA concrete. Adding 0.1%, 0.15%, and 0.2% MWCNTs to RHA concrete resulted in drying shrinkage reductions of 9.23%, 6.92%, and 3.08%, respectively, at 120 d compared to that of the control specimen. The addition of 0.1% MWCNTs resulted in the most significant improvement in drying shrinkage resistance of RHA concrete, followed by improvements owing to 0.15% and 0.2% MWCNTs. The effect of MWCNTs on improving the early resistance to drying shrinkage in RHA concrete was stronger than its effect on improving the long-term resistance to drying shrinkage.

The enhanced shrinkage resistance in RHA concrete with MWCNTs was attributable to the following reasons: (1) from a microscopic perspective, a structural network formed in the RHA concrete owing to the bridging effect of MWCNTs, which effectively reduced the pore size and number of macropores, delaying the development of microcracks110,111; (2) the filling effect of MWCNTs significantly decreased the number of nanopores and capillaries, resulting in reduced porosity and capillary stress112,113; (3) the nucleation effect of MWCNTs promoted C-S-H gel formation on the surfaces, which delayed the covering of cement and RHA particles that had not yet undergone hydration and pozzolanic reactions, respectively. Consequently, cement particle hydration and the pozzolanic reaction of RHA made the microstructure compact114,115.

Comparison of typical models

The trend of long-term drying shrinkage development was investigated to avoid excessive shrinkage. Various established prediction models were considered and verified using large volumes of test data. Typical prediction models include ACI 209, CEB-FIP, B3, GL 2000, and Sakata. The corresponding equations for the models are listed in Table 10.

Figure 14 shows the results from drying shrinkage experiment and five prediction models for RHA concrete with varying MWCNT concentrations. The outcomes of the prediction models at an early stage were considerably lower than the experimental results because most prediction models operated under normal temperature (below 40 °C). However, the experimental environment (60 °C) was harsh and dry. The discrepancies between the predictions of B3 and GL 2000 and the experimental findings for RHA concrete decreased as drying progressed. However, the long-term shrinkage of RHA concrete was overestimated by SAK, ACI 209, and GL2000.

Table 11 lists the CV values for the mixtures at 7 d. With CV values of 0.13–1.13, the overall accuracy of all prediction models was undesirable. Additionally, early stage drying shrinkage was best predicted by SAK, resulting in CV values of 0.13–0.33. The decreasing order of prediction accuracy for the remaining models was GL2000, ACI209, CEP-FIP, and B3. Table 12 lists the CV values for the mixtures at 100 d. With CV values of 0–0.57, all prediction models exhibited considerably higher accuracies in predicting long-term RHA concrete cracking. B3 offered the highest prediction accuracy, with CV values of 0–0.05. The decreasing order of prediction accuracy for the remaining models was GL2000, CEP-FIP, ACI209, and SAK. From the perspective of the entire drying shrinkage life cycle of RHA concrete, MWCNTs improved the difference between the early drying shrinkage test results and the results of each prediction model, excluding CEP-FIP. However, no evident improvement was observed in the difference between the results of long-term drying shrinkage tests and those predicted. When 0.1% MWCNTs were added, the prediction accuracies of ACI209, B3, GL2000, and SAK increased by 16.67%, 7.96%, 8.82%, and 27.3%, respectively.

Microstructure and constituents

Figures 15 and 16 show the energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) analysis of R15C0 and R15C10, and Table 13 demonstrates the elements analysis of EDS. The spectrum for R15C0 revealed oxygen (O) and silicon (Si) as the predominant elements, with a pronounced peak for oxygen (O) suggesting a substantial presence of oxides, demonstrating a similarity in the chemical composition of RHA and the cement matrix. The silicon peak indicates the composition of RHA, wherein amorphous silicon dioxide serves a reactive function in the cement hydration process. The presence of calcium (Ca) signifies the initiation of cement hydration products, such as C-S-H gel, which further augment the strength and stability of concrete. Following the introduction of carbon nanotubes, the EDS spectrum of R15C10 indicates that the peak intensity of the carbon (C) element markedly increases with the rising proportion of MWCNTs. The presence of carbon (C) indicates the entrance of MWCNTs, and as the quantity grows, the intensity of the carbon peak progressively rises. Additionally, the calcium (Ca) content rose, suggesting that the interaction between carbon nanotubes and cement hydration products augmented the hydration process of the cement matrix, resulting in the formation of additional hydrated silicates.

Figure 17 shows the SEM images of the RHA concrete with varying MWCNTs concentration. Figure 17a, it can be seen that R15C0 exhibits a relatively uniform structure of cement hydration products, and the interface between RHA particles and cement hydration products is relatively clear. This structure represents the normal hydration reaction process of the cement matrix, and the RHA particles play a filling role and improve the microscopic pore structure of concrete. Its chemical composition showed a high amount of SiO2, reflecting the pozzolanic reaction of rice husk ash to produce C-S-H gel. Figure 17b shows that by adding 0.1% MWCNTs, the microstructure of the cement matrix changes. The low-dosage of MWCNTs is evenly distributed in the cement matrix, the pores in the cement matrix become less, and the bridging and filling effects of the carbon nanotubes are obvious. The high specific surface area and excellent mechanical properties of carbon nanotubes not only fill the micropores formed during the cement hydration process, but also play a role in connecting the hydration products in the cement matrix to form a denser structure. This could explain the improvement of the durability of RHA sustainable concrete by well-dispersed MWCNTs. The uniformly distributed MWCNTs efficiently fill the micro-cracks in the RHA concrete, thereby diminishing the quantity of macropores and inhibiting microcrack formation, eventually enhancing the RHA concrete’s resistance to drying shrinkage121.

However, from Fig. 17c, d, it can be clearly seen that as the amount of MWCNTs increases, the dispersion of MWCNTs shows significant problems. It can be observed that with a higher dosage of MWCNTs, aggregation occurs, and the carbon nanotubes begin to intertwine and form agglomerates. Figure 17c shows that while most of the MWCNTs still serve as bridges, some agglomerate because of van der Waals force. Figure 17c shows that while most of the MWCNTs still serve as bridges, some agglomerate because of van der Waals force. Figure 17d shows that numerous MWCNTs agglomerate to form more pores in the RHA concrete, increasing the porosity and reducing the interfacial adhesion between CNTs and cement matrix, thereby increasing the defects in the matrix. This is the reason for the RHA concrete’s decreasing resistance to water, acid, and sulphate penetration. Sarvandani et al.27 also came to similar results by investigating the SEM images of cement mortar containing MWCNTs. When the MWCNTs dosage in cement mortar was 0.4%, the MWCNTs aggregated into bundles and formed virtual defect sites in the C-S-H. Zhang et al.56 investigated the SEM images of cement paste with inadequately dispersed MWNTs and found that the agglomeration of MWCNTs tended to the clustering among cement particles, creating new pores and thus reducing the compactness of the cement matrix.

Sustainable evaluation

Environmental evaluation

Table 14 presents the environmental evaluation results for RHA with varying MWCNTs concentrations based on a 1 m3 specimen. The compressive, splitting tensile, and flexural strength test results were taken from Jing et al.89. The CO2 emissions of coarse aggregate and fine aggregate took into account the factors of excavation, cutting, grinding, screening, and transportation. The CO2 emissions of cement took into account the production process and transportation of cement. The CO2 emission intensity factors (t-CO2-eq/ton) of the OPC, coarse aggregate, and fine aggregate were 0.82, 0.0459, and 0.0139, respectively122,123. Furthermore, According to the study of Hu et al.124, taking into account factors such as agricultural growth stage, transportation and combustion, the amount of CO2 emitted (t-CO2-eq/tonne) by RHA was 0.157. Greenhouse gas emissions are highly sensitive to different CNT synthesis methods. As CNT production transitions from laboratory to industry, manufacturers improve the efficiency of material and energy utilisation to reduce costs125.

This study considered the greenhouse gas emissions generated during large-scale industrial production of CNTs. According to Teah et al.126, the emission factor (kg CO2-e/g) of CNTs is < 0.029 for large-scale industrial production. Evidently, adding MWCNTs gradually increased CO2 emissions of RHA concrete.

From Table 14, with the addition of 0.1% MWCNTs, the CI value of the RHA concrete exhibited a declining trend compared to that of R15C0. Additionally, the CI splitting tensile strength of RHA concrete with 0.1% MWCNTs exhibited the largest decrease (16.47%), because MWCNT addition exerted a substantial effect on improving the splitting tensile strength of the RHA concrete. Furthermore, the CI compressive and flexural strengths of RHA concrete containing 0.1% MWCNTs decreased by 4.31% and 11.99%, respectively. Xiao et al.127 reported the CI compressive strength of OPC 42.5 as 18.1. All CI compressive strength values of RHA concrete with varying MWCNTs concentrations were below those reported for OPC 42.5. Sustainability evaluation confirmed the environmental friendliness of RHA concrete containing MWCNTs.

Cost efficiency

Tables 15 and 16 list the cost and cost efficiency factor (CEF) of all mixtures. From Table 15, the cost of the specimens increased with the MWCNTs concentration, but the overall cost was controlled between $17.14 and $19.23 per specimen. The cost of RHA concrete with 0.1%, 0.15%, and 0.2% MWCNTs increased by 6.18%, 9.21%, and 12.25%, respectively, compared to that without MWCNTs, because the current cost of MWCNTs is higher than that of cement. However, with industrialisation of MWCNTs production, the unit price of materials is expected to decline. According to the 2022 and 2023 annual reports of Jiangsu Cnano Technology Co., Ltd., the material price of CNTs dropped from $24.52 in 2022 to $14.89 in 2023, a decrease of 39.27%90,128.

As presented in Table 16, with the addition of 0.1% MWCNTs, the CEF compressive strength, CEF splitting tensile strength, and CEF flexural strength increased by 1.78%, 16.6%, and 10.66%, respectively. However, with increasing MWCNTs concentration, CEF showed a downward trend owing to the re-agglomeration of MWCNTs in the cement matrix, resulting in decreasing mechanical properties of RHA concrete129. Small doses of well-dispersed MWCNTs resulted in an overall improvement in CEF of RHA concrete, with improvements in the cost efficiency of splitting tensile strength and flexural strength. Thus, MWCNTs provided a greater cost advantage in building flexural members. Furthermore, the effect of MWCNTs in RHA concrete and the unit price of MWCNTs materials were key factors affecting CEF. Therefore, factors influencing the effect of MWCNTs in RHA concrete, such as the type of MWCNTs material and the dispersion effect of MWCNTs, were particularly important.

Conclusion

This study investigated the mechanical properties, durability, and sustainability of RHA concrete containing MWCNTs concentrations ranging from 0 to 0.20%. The experimental results for the RHA concrete with and without MWNCTs were compared. The following conclusions were drawn.

-

Slump tests revealed satisfactory workability despite the decreasing fluidity of RHA concrete with increasing MWCNTs concentration. The density of the mixture increased, even with minimal additions of MWCNTs owing to the high specific surface area of MWCNTs, which absorbed more water.

-

On adding 0.10% MWCNTs to RHA concrete, the elastic modulus increased slightly by 0.10% and decreased with an increasing proportion of MWCNTs.

-

By adding 0.10% MWCNTs to RHA concrete, sorptivity decreased by 28.76%, weight and compressive strength losses under 111-d sulphate attack decreased by 50.93% and 48.47%, respectively, and the mass loss under acid attack decreased by 35.97% when compared to the control specimen.

-

MWCNTs improved the drying shrinkage resistance in RHA concrete at 60 °C, especially the early-age drying shrinkage. Compared to the control specimens, the 3-d and 7-d shrinkage decreased by 36.7% and 25.22%, respectively.

-

All prediction models underestimated early-age drying shrinkage in RHA concrete. B3 was the most reliable predictor of long-term drying shrinkage in RHA concrete, with a maximum accuracy of 99.6%.

-

Through SEM and EDS, the enhancement effect of MWCNTs on the mechanics and durability of RHA concrete was observed. The synergistic effect of the filling and bridging by MWCNTs and the RHA pozzolanic reaction reduced the internal pores of RHA and densified its internal structure.

-

The addition of 0.1% MWCNTs significantly reduced the CI value of the RHA concrete, with a 16.51% decrease in CI-splitting tensile strength. Simultaneously, the addition of 0.01% MWCNTs effectively improved the cost-effectiveness of RHA concrete, with a 16.67% increase in CEF-splitting tensile strength, verifying the sustainability of RHA concrete containing MWCNTs.

This study demonstrated that the addition of MWCNTs enhanced the overall performance of RHA concrete, particularly its resistance to drying shrinkage at high temperatures. This improvement supported the use of RHA concrete in tropical areas, broadening its application, and reducing environmental pollution from agricultural waste treatment, thereby advancing sustainable construction.

Limitations and future scope

The effects of RHA production conditions on the performance of RHA concrete containing MWCNTs have not been considered. Examples include RHA produced in different regions and under different combustion conditions. The influence of the various forms of CNTs on the performance of RHA concrete containing MWCNTs has not been considered. Examples include single-walled nanotubes, MWNCTs, functional MWCNTs, and non-functional MWCNTs. When considering cost efficiency, only the impact of raw material prices in China was considered in this study.

Future research should comprehensively study the performance of RHA concrete containing diverse MWCNTs in extreme environments, such as at high temperatures. As the reinforcing effect of MWCNTs on RHA concrete mainly depends on their dispersion, the effect of MWCNTs on concrete with RHA and different physical properties under different dispersion methods should be analysed. Further, the durability of RHA concrete containing MWCNTs and its application in actual building components should be investigated.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

IEA & Industry—Energy System. IEA (2023). https://www.iea.org/energy-system/industry

Abdellatief, M. et al. Evaluating enhanced predictive modeling of foam concrete compressive strength using artificial intelligence algorithms. Mater. Today Commun. 40, 110022 (2024).

Hong, S. H., Choi, J. S., Yoo, S. J. & Yoon, Y. S. Structural benefits of using carbon nanotube reinforced high-strength lightweight concrete beams. Dev. Built Environ. 16, 100234 (2023).

Saloni et al. Performance of rice husk Ash-based sustainable geopolymer concrete with Ultra-fine slag and corn cob ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 279, 122526 (2021).

Fernando, S. et al. Engineering properties of waste-based alkali activated concrete brick containing low calcium fly ash and rice husk ash: a comparison with traditional Portland cement concrete brick. J. Build. Eng. 46, 103810 (2022).

Amin, M. et al. Influence of recycled aggregates and carbon nanofibres on properties of ultra-high-performance concrete under elevated temperatures. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 16, e01063 (2022).

Hakeem, I. Y., Agwa, I. S., Tayeh, B. A. & Abd-Elrahman, M. H. Effect of using a combination of rice husk and olive waste ashes on high-strength concrete properties. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 17, e01486 (2022).

Tahwia, A. M., Elmansy, A., Abdellatief, M. & Elrahman, M. A. Durability and ecological assessment of low-carbon high-strength concrete with short AR-glass fibers: effects of high-volume of solid waste materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 429, 136422 (2024).

Abolhasani, A., Samali, B., Dehestani, M. & Libre, N. A. Effect of rice husk ash on mechanical properties, fracture energy, brittleness and aging of calcium aluminate cement concrete. Structures 36, 140–152 (2022).

Pandey, A. & Kumar, B. Utilization of agricultural and industrial waste as replacement of cement in pavement quality concrete: a review. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 29, 24504–24546 (2022).

Zain, M. F. M., Islam, M. N., Mahmud, F. & Jamil, M. Production of rice husk ash for use in concrete as a supplementary cementitious material. Constr. Build. Mater. 25, 798–805 (2011).

Chen, R., Congress, S. S. C., Cai, G., Duan, W. & Liu, S. Sustainable utilization of biomass waste-rice husk ash as a new solidified material of soil in geotechnical engineering: a review. Constr. Build. Mater. 292, 123219 (2021).

Endale, S. A., Taffese, W. Z., Vo, D. H. & Yehualaw, M. D. Rice husk ash in concrete. Sustainability 15, 137 (2023).

Anto, G. et al. Mechanical properties and durability of ternary blended cement paste containing rice husk ash and nano silica. Constr. Build. Mater. 342, 127732 (2022).

Balraj, A., Jayaraman, D., Krishnan, J. & Alex, J. Experimental investigation on water absorption capacity of RHA-added cement concrete. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 63623–63628 (2021).

Vieira, A. P., Filho, T., Tavares, R. D., Cordeiro, G. C. & L. M. & Effect of particle size, porous structure and content of rice husk ash on the hydration process and compressive strength evolution of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 236, 117553 (2020).

Zhang, P., Wei, S., Cui, G., Zhu, Y. & Wang, J. Properties of fresh and hardened self-compacting concrete incorporating rice husk ash: a review. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 61, 563–575 (2022).

Meddah, M. S., Praveenkumar, T. R., Vijayalakshmi, M. M., Manigandan, S. & Arunachalam, R. Mechanical and microstructural characterization of rice husk ash and Al2O3 nanoparticles modified cement concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 255, 119358 (2020).

Anwar, A., Liu, X. & Zhang, L. Nano-cementitious composites modified with graphene oxide—a review. Thin-Walled Struct. 183, 110326 (2023).

Raheem, A. A., Abdulwahab, R. & Kareem, M. A. Incorporation of metakaolin and nanosilica in blended cement mortar and concrete—A review. J. Clean Prod. 290, 125852 (2021).

Li, S. et al. The performance and functionalization of modified cementitious materials via nano titanium-dioxide: a review. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 19, e02414 (2023).

Abdalla, J. A. et al. Influence of nano-TiO2, nano-Fe2O3, nanoclay and nano-CaCO3 on the properties of cement/geopolymer concrete. Clean Mater. 4, 100061 (2022).

Xing, G. et al. Research on the mechanical properties of steel fibers reinforced carbon nanotubes concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 392, 131880 (2023).

Wang, Z., Bai, E., Xu, J., Du, Y. & Zhu, J. Effect of nano-SiO2 and nano-CaCO3 on the static and dynamic properties of concrete. Sci. Rep. 12, 907 (2022).

Zhang, P., Sun, Y., Wei, J. & Zhang, T. Research progress on properties of cement-based composites incorporating graphene oxide. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 62 (2023).

Han, G. et al. Carbon nanotubes assisted fly ash for cement reduction on the premise of ensuring the stability of the grouting materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 368, 130476 (2023).

Mansouri Sarvandani, M., Mahdikhani, M., Aghabarati, H. & Haghparast Fatmehsari, M. Effect of functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes on mechanical properties and durability of cement mortars. J. Build. Eng. 41, 102407 (2021).

Akarsh, P. K., Marathe, S. & Bhat, A. K. Influence of graphene oxide on properties of concrete in the presence of silica fumes and M-sand. Constr. Build. Mater. 268, 121093 (2021).

Nuaklong, P., Jongvivatsakul, P., Pothisiri, T., Sata, V. & Chindaprasirt, P. Influence of rice husk ash on mechanical properties and fire resistance of recycled aggregate high-calcium fly ash geopolymer concrete. J. Clean Prod. 252, 119797 (2020).

Atrian, M. A., Hosseini, K., Mirvalad, S. & Habibnejad Korayem, A. Effect of rice husk ash on dispersion of graphene oxide in alkaline cementitious environment. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 36, 04023600 (2024).

Praveenkumar, T. R., Vijayalakshmi, M. M. & Manigandan, S. Thermal conductivity of concrete reinforced using TiO2 nanoparticles and rice husk ash. Int. J. Ambient Energy 43, 1127–1133 (2022).

Alex, A. G., Kemal, Z., Gebrehiwet, T. & Getahun, S. Effect of α: Phase nano Al2O3 and rice husk ash in cement mortar. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2022, 4335736 (2022).

Avudaiappan, S. et al. Experimental investigation and image processing to predict the properties of concrete with the addition of nano silica and rice husk ash. Crystals 11, 1230 (2021).

Shanmuga Priya, T., Mehra, A., Jain, S. & Kakria, K. Effect of graphene oxide on high-strength concrete induced with rice husk ash: mechanical and durability performance. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 6, 5 (2020).

Meddah, M. S., Praveenkumar, T. R., Vijayalakshmi, M. M., Manigandan, S. & Arunachalam, R. Mechanical and microstructural characterization of rice husk ash and Al2O3 nanoparticles modified cement concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 255, 119358 (2020).

Praveenkumar, T. R., Vijayalakshmi, M. M. & Meddah, M. S. Strengths and durability performances of blended cement concrete with TiO2 nanoparticles and rice husk ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 217, 343–351 (2019).

Assi, L. et al. Multiwall carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) dispersion & mechanical effects in OPC mortar & paste: a review. J. Build. Eng. 43, 102512 (2021).

Son, D. H. et al. Mechanical properties of mortar and concrete incorporated with concentrated graphene oxide, functionalized carbon nanotube, nano silica hybrid aqueous solution. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 18, e01603 (2023).

Tao, J., Wang, J. & Zeng, Q. A comparative study on the influences of CNT and GNP on the piezoresistivity of cement composites. Mater. Lett. 259, 126858 (2020).

Iijima, S. Helical microtubules of graphitic carbon. Nature 354, 56–58 (1991).

Ramezani, M., Dehghani, A. & Sherif, M. M. Carbon Nanotube reinforced cementitious composites: a comprehensive review. Constr. Build. Mater. 315, 125100 (2022).

Abbas, A. M. et al. Purification techniques for cheap multi-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1660, 012022 (2020).

Yu, M. F., Files, B. S., Arepalli, S. & Ruoff, R. S. Tensile loading of ropes of single wall carbon nanotubes and their mechanical properties. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 5552–5555 (2000).

Demczyk, B. G. et al. Direct mechanical measurement of the tensile strength and elastic modulus of multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 334, 173–178 (2002).

Hong, S. H., Choi, J. S., Yoo, S. J., Yoo, D. Y. & Yoon, Y. S. Reinforcing effect of CNT on the microstructure and creep properties of high-strength lightweight concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 428, 136294 (2024).

Chen, J. & Akono, A. T. Influence of multi-walled carbon nanotubes on the hydration products of ordinary Portland cement paste. Cem. Concr. Res. 137, 106197 (2020).

Danoglidis, P. A., Konsta-Gdoutos, M. S., Gdoutos, E. E. & Shah, S. P. Strength, energy absorption capability and self-sensing properties of multifunctional carbon nanotube reinforced mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 120, 265–274 (2016).

Konsta-Gdoutos, M. S., Danoglidis, P. A. & Shah, S. P. High modulus concrete: effects of low carbon nanotube and nanofiber additions. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 103, 102295 (2019).

Carriço, A., Bogas, J. A., Hawreen, A. & Guedes, M. Durability of multi-walled carbon nanotube reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 164, 121–133 (2018).

Alafogianni, P., Dassios, K., Tsakiroglou, C. D., Matikas, T. E. & Barkoula, N. M. Effect of CNT addition and dispersive agents on the transport properties and microstructure of cement mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 197, 251–261 (2019).

Yakovlev, G. et al. Modification of construction materials with multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Procedia Eng. 57, 407–413 (2013).

Jongvivatsakul, P. et al. Enhancing bonding behavior between carbon fiber-reinforced polymer plates and concrete using carbon nanotube reinforced epoxy composites. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 17, e01407 (2022).

Nuaklong, P., Boonchoo, N., Jongvivatsakul, P., Charinpanitkul, T. & Sukontasukkul, P. Hybrid effect of carbon nanotubes and polypropylene fibers on mechanical properties and fire resistance of cement mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 275, 122189 (2021).

Aqsiq, S. A. C. Common Portland Cement (2007).

Aqsiq, S. A. C. Pebble and crushed stone for construction (2011).

Zhang, J., Ke, Y., Zhang, J., Han, Q. & Dong, B. Cement paste with well-dispersed multi-walled carbon nanotubes: mechanism and performance. Constr. Build. Mater. 262, 120746 (2020).

Bu, C. Z. Fang he Cheng Xiang Jian she & Ju, C. G. jia Zhi Liang Jian Du Jian Yan Jian Yi Zong. Code for Design of Concrete Structures (China Architecture & Building Press, 2010).

JGJ 55-2011. Specification for mix proportion design of ordinary concrete (2011).

GB/T 50080-2016. Standard for test method of performance on ordinary fresh concrete (2016).

GB/T 50080-2019. Standard for test Methods of Concrete Physical and Mechanical Properties (China Archit. Build. Press, 2019).

Choudhary, M. et al. Contemporary review on carbon nanotube (CNT) composites and their impact on multifarious applications. Nanotechnol. Rev. 11, 2632–2660 (2022).

Du, Y., Pundienė, I., Pranckevičienė, J., Zujevs, A. & Korjakins, A. Study on the pore structure of lightweight mortar with nano-additives. Nanomaterials 13, 2942 (2023).

Du, Y. & Korjakins, A. Synergic effects of nano additives on mechanical performance and microstructure of lightweight cement mortar. Appl. Sci. 13, 5130 (2023).

O’Rear, E. A., Onthong, S. & Pongprayoon, T. Mechanical strength and conductivity of cementitious composites with multiwalled carbon nanotubes: to functionalize or not? Nanomaterials 14, 80 (2024).

Eisa, M. S., Mohamady, A., Basiouny, M. E., Abdulhamid, A. & Kim, J. R. Mechanical properties of asphalt concrete modified with carbon nanotubes (CNTs). SCI-3Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 16, e00930 (2022).

Gao, Y., Jing, H., Zhao, Z., Shi, X. & Li, L. Influence of ultrasonication energy on reinforcing-roles of CNTs to strengthen ITZ and corresponding anti-permeability properties of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 303, 124451 (2021).

Soni, S. K., Thomas, B. & Kar, V. R. A comprehensive review on CNTs and CNT-reinforced composites: syntheses, characteristics and applications. Mater. Today Commun. 25, 101546 (2020).

Qin, Y., Tang, Y., RUAN, P., WANG, W. & CHEN, B. Progress in multi-scale study on piezoresistive effect of carbon nanotube cement-based composite. Chem. Ind. Eng. Prog. 40, 4278–4289 (2021).

Rennhofer, H. & Zanghellini, B. Dispersion state and damage of carbon nanotubes and carbon nanofibers by ultrasonic dispersion: a review. Nanomaterials 11, 1469 (2021).

Silvestro, L., Jean, P. & Gleize, P. Effect of carbon nanotubes on compressive, flexural and tensile strengths of Portland cement-based materials: a systematic literature review. Constr. Build. Mater. 264, 120237 (2020).

Du, Y., Korjakins, A., Sinka, M. & Pundienė, I. Lifecycle assessment and multi-parameter optimization of lightweight cement mortar with nano additives. Materials 17, 4434 (2024).

Adhikary, S. K., Rudžionis, Ž., Tučkutė, S. & Ashish, D. K. Effects of carbon nanotubes on expanded glass and silica aerogel based lightweight concrete. Sci. Rep. 11, 2104 (2021).

Cerro-Prada, E., Pacheco-Torres, R. & Varela, F. Effect of multi-walled carbon nanotubes on strength and electrical properties of cement mortar. Materials 14, 79 (2021).

Gao, F., Tian, W., Wang, Z. & Wang, F. Effect of diameter of multi-walled carbon nanotubes on mechanical properties and microstructure of the cement-based materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 260, 120452 (2020).

Narasimman, K., Jassam, T. M., Velayutham, T. S., Yaseer, M. M. M. & Ruzaimah, R. The synergic influence of carbon nanotube and nanosilica on the compressive strength of lightweight concrete. J. Build. Eng. 32, 101719 (2020).

Allujami, H. M. et al. Mechanical properties of concrete containing recycle concrete aggregates and multi-walled carbon nanotubes under static and dynamic stresses. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 17, e01651 (2022).

Yao, Y. & Lu, H. Mechanical properties and failure mechanism of carbon nanotube concrete at high temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 297, 123782 (2021).

Jung, M., Lee, Y., Hong, S. G. & Moon, J. Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) in ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC): dispersion, mechanical properties, and electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding effectiveness (SE). Cem. Concr. Res. 131, 106017 (2020).

Safdar Raza, S., Ali, B., Noman, M., Fahad, M. & Mohamed Elhadi, K. Mechanical properties, flexural behavior, and chloride permeability of high-performance steel fiber-reinforced concrete (SFRC) modified with rice husk ash and micro-silica. Constr. Build. Mater. 359, 129520 (2022).

Liu, C. et al. Recycled aggregate concrete with the incorporation of rice husk ash: mechanical properties and microstructure. Constr. Build. Mater. 351, 128934 (2022).

Mostafa, A. S., Tayeh, S. A., Tawfik, T. A. & B. A. & Mechanical and durability properties of ultra-high performance concrete incorporated with various nano waste materials under different curing conditions. J. Build. Eng. 43, 102569 (2021).

Wu, K., Han, H., Rößler, C., Xu, L. & Ludwig, H. M. Rice hush ash as supplementary cementitious material for calcium aluminate cement—effects on strength and hydration. Constr. Build. Mater. 302, 124198 (2021).

Sathurshan, M. et al. Untreated rice husk ash incorporated high strength self-compacting concrete: Properties and environmental impact assessments. Environ. Chall. 2, 100015 (2021).

Althoey, F. et al. Impact of sulfate activation of rice husk ash on the performance of high strength steel fiber reinforced recycled aggregate concrete. J. Build. Eng. 54, 104610 (2022).

Ali, T., Saand, A., Bangwar, D. K., Buller, A. S. & Ahmed, Z. Mechanical and durability properties of aerated concrete incorporating rice husk ash (RHA) as partial replacement of cement. Crystals 11, 604 (2021).

Miyandehi, B. M. et al. Performance and properties of mortar mixed with nano-CuO and rice husk ash. Cem. Concr. Compos. 74, 225–235 (2016).

Muhammad, N., Baharom, S., Amirah, N., Ghazali, M. & Alias, N. Effect of heat curing temperatures on fly ash-based geopolymer concrete. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 8, 15–19 (2019).

Nayan, N., Saleh, Y., Henry, M., Hashim, M. & Mahat, H. Urban land surface temperature variability in Kuala Lumpur City, Malaysia. Test. Eng. Manag. 83, 24120–24137 (2020).

Jing, Y. et al. Mechanical properties, permeability and microstructural characterisation of rice husk ash sustainable concrete with the addition of carbon nanotubes. Heliyon 10, e32780 (2024).

Jiangsu Cnano Technology Co.,Ltd. 2023 Annual Report (2024).

Chaipanich, A., Nochaiya, T., Wongkeo, W. & Torkittikul, P. Compressive strength and microstructure of carbon nanotubes–fly ash cement composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 527, 1063–1067 (2010).

Nowak, A. & Rakoczy, A. Statistical model for compressive strength of lightweight concrete. Archit. Civ. Eng. Environ. 4, 73–80 (2011).

Kosmatka, S. & Wilson, M. Design and Control of Concrete Mixtures (2011).

Ahmad, J. & Zhou, Z. Properties of concrete with addition carbon nanotubes: a review. Constr. Build. Mater. 393, 132066 (2023).

Zhang, P., Su, J., Guo, J. & Hu, S. Influence of carbon nanotube on properties of concrete: a review. Constr. Build. Mater. 369, 130388 (2023).

Institution, B. S. Structural Use of Concrete (British Standards Institution, 1985).

Valluvan, R., Kreger, M. E. & Jirsa, J. O. Evaluation of ACI 318-95 shear-friction provisions. Struct. J. 96, 473–481 (1999).

Tasnimi, A. A. Mathematical model for complete stress–strain curve prediction of normal, light-weight and high-strength concretes. Mag. Concr. Res. 56, 23–34 (2004).

Slate, F., Nilson, A. H. & Martinez, S. Mechanical properties of high-strength lightweight concrete. J. Proc. 83, 606–613 (1986).

Sahoo, S., Parhi, P. K. & Chandra Panda, B. Durability properties of concrete with silica fume and rice husk ash. Clean Eng. Technol. 2, 100067 (2021).

Gao, Y. et al. Particle size distribution of aggregate effects on the reinforcing roles of carbon nanotubes in enhancing concrete ITZ. Constr. Build. Mater. 327, 126964 (2022).

Kim, G. M. et al. Carbon nanotube (CNT) incorporated cementitious composites for functional construction materials: the state of the art. Compos. Struct. 227, 111244 (2019).

Liu, P., Chen, Y., Wang, W. & Yu, Z. Effect of physical and chemical sulfate attack on performance degradation of concrete under different conditions. Chem. Phys. Lett. 745, 137254 (2020).

Varisha, V., Zaheer, M. M. & Hasan, S. D. Mechanical and durability performance of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and nanosilica (NS) admixed cement mortar. Mater. Today Proc. 42, 1422–1431 (2021).

Yang, Y. Z., Li, M. G., Deng, H. W. & Liu, Q. Effects of temperature on drying shrinkage of concrete. Appl. Mech. Mater. 584–586, 1176–1181 (2014).

Siddika, A., Mamun, M. A. A., Alyousef, R. & Mohammadhosseini, H. State-of-the-art-review on rice husk ash: a supplementary cementitious material in concrete. J. King Saud Univ. Eng. Sci. 33, 294–307 (2021).

Bouziadi, F., Boulekbache, B. & Hamrat, M. The effects of fibres on the shrinkage of high-strength concrete under various curing temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 114, 40–48 (2016).

Ziari, H., Fazaeli, H., Kang Olyaei, V., Ziari, M. A. & S. J. & Evaluation of effects of temperature, relative humidity, and wind speed on practical characteristics of plastic shrinkage cracking distress in concrete pavement using a digital monitoring approach. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 15, 138–158 (2022).

Memon, S. A., Shah, S. F. A., Khushnood, R. A. & Baloch, W. L. Durability of sustainable concrete subjected to elevated temperature—a review. Constr. Build. Mater. 199, 435–455 (2019).

Tran, N. P. et al. A critical review on drying shrinkage mitigation strategies in cement-based materials. J. Build. Eng. 38, 102210 (2021).

Dong, S., Wang, D., Ashour, A., Han, B. & Ou, J. Nickel plated carbon nanotubes reinforcing concrete composites: from nano/micro structures to macro mechanical properties. Compos. Part Appl. Sci. Manuf. 141, 106228 (2021).

Li, L. et al. Carbon nanotube (CNT) reinforced cementitious composites for structural self-sensing purpose: a review. Constr. Build. Mater. 392, 131384 (2023).

Hawreen, A., Bogas, J. A. & Dias, A. P. S. On the mechanical and shrinkage behavior of cement mortars reinforced with carbon nanotubes. Constr. Build. Mater. 168, 459–470 (2018).

Guan, X., Bai, S., Li, H. & Ou, J. Mechanical properties and microstructure of multi-walled carbon nanotube-reinforced cementitious composites under the early-age freezing conditions. Constr. Build. Mater. 233, 117317 (2020).

Makar, J. M. & Chan, G. W. Growth of cement hydration products on single-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 92, 1303–1310 (2009).

209R-92. Prediction of Creep, Shrinkage, and temperature effects in concrete structures (Reapproved 2008). https://www.concrete.org/publications/internationalconcreteabstractsportal/m/details/id/5089

Beton, C. E. I. D. & CEB-FIP Model Code 1990. Des. Code 54–58 (1991).

Creep and shrinkage prediction model for analysis and design of concrete structures—model B3. Mater. Struct. 28, 357–365 (1995).

Gardner, N. J. & Lockman, M. J. Design provisions for drying shrinkage and creep of normal-strength concrete. Mater. J. 98, 159–167 (2001).

Sakata, K., Tsubaki, T., Inoue, S. & Ayano, T. Prediction equations of creep and drying shrinkage strain for wide-ranged strength concrete. Proc. Sixth Int. Conf. 2001, 1–19 (2001).

Wang, B. & Pang, B. Properties improvement of multiwall carbon nanotubes-reinforced cement-based composites. J. Compos. Mater. 54, 2379–2387 (2020).

Collins, F. Inclusion of carbonation during the life cycle of built and recycled concrete: influence on their carbon footprint. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 15, 549–556 (2010).

Flower, D. J. M. & Sanjayan, J. G. Green house gas emissions due to concrete manufacture. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 12, 282–288 (2007).

Hu, L., He, Z. & Zhang, S. Sustainable use of rice husk ash in cement-based materials: environmental evaluation and performance improvement. J. Clean Prod. 264, 121744 (2020).

Licht, S. et al. Amplified CO2 reduction of greenhouse gas emissions with C2CNT carbon nanotube composites. Mater. Today Sustain. 6, 100023 (2019).

Teah, H. Y. et al. Life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of long and pure carbon nanotubes synthesized via on-substrate and fluidized-bed chemical vapor deposition. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 8, 1730–1740 (2020).

Xiao, R. et al. Strength, microstructure, efflorescence behavior and environmental impacts of waste glass geopolymers cured at ambient temperature. J. Clean Prod. 252, 119610 (2020).

Jiangsu Cnano Technology Co., Ltd. 2022 Annual Report (2023).

Yesudhas Jayakumari, B., Nattanmai Swaminathan, E. & Partheeban, P. A review on characteristics studies on carbon nanotubes-based cement concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 367, 130344 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by a UCSI University Research Excellence & Innovation Grant (REIG) (REIG-FETBE-2022/017), which also provided the research facilities and materials. The Malaysian Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE) for supporting this work through the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS), under project code FRGS/1/2024/TK06/UCSI/02/1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.J. and J.C.L.; Acquired funding, J.C.L. and W.C.M. ;methodology, Y.J. and J.C.L.; formal analysis, Y.J. and J.C.L.; investigation, Y.J. and J.C.L.; resources, Y.J. and J.C.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.J. and J.C.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.J. and J.C.L.; visualization, Y.J. and J.C.L.; supervision, J.C.L., W.C.M., J.L.N., M.K.Y. and Y.J. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jing, Y., Lee, J.C., Moon, W.C. et al. Durability and environmental evaluation of rice husk ash sustainable concrete containing carbon nanotubes. Sci Rep 15, 4352 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88927-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88927-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Multi-parameter Experimental and Statistical Investigation on the Strength and Durability of High-performance Concrete Containing Nano-cellulose Fibrils

Iranian Journal of Science and Technology, Transactions of Civil Engineering (2025)

-

Experimental Investigation of Concrete Performance Incorporating Deccan Basalt Manufactured Sand and Rice Husk Ash

National Academy Science Letters (2025)