Abstract

Accurate space object pose estimation is crucial for various space tasks, including 3D reconstruction, satellite navigation, rendezvous and docking maneuvers, and collision avoidance. Many previous studies, however, often presuppose the availability of the space object’s computer-aided design model for keypoint matching and model training. This work proposes a generalized pose estimation pipeline that is independent of 3D models and applicable to both instance- and category-level scenarios. The proposed framework consists of three parts based on deep learning approaches to accurately estimate space objects pose. First, a keypoints extractor is proposed to extract sub-pixel-level keypoints from input images. Then a multichannel matching network with triple loss is designed to obtain the matching pairs of keypoints in the body reference system. Finally, a pose graph optimization algorithm with a dynamic keyframes pool is designed to estimate the target pose and reduce long-term drifting pose errors. A space object dataset including nine different types of non-cooperative targets with 11,565 samples is developed for model training and evaluation. Extensive experimental results indicate that the proposed method demonstrates robust performance across various challenging conditions, including different object types, diverse illumination scenarios, varying rotation rates, and different image resolutions. To verify the demonstrated approach, the model is compared with several state-of-the-art approaches and shows superior estimation results. The mAPE and mMS scores of the proposed approach reach 0.63° and 0.767, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A critical aspect for the success of in-space servicing and debris removal operations is the 3D reconstruction of non-cooperative target objects, which relies heavily on minimal equipment. One of the key steps in 3D reconstruction involves precise pose estimation-determining and tracking the relative position and orientation of the target. Accurately establishing the approach trajectory and adapting control systems in real time are fundamentally dependent on performing onboard pose estimation as part of the 3D reconstruction process. Many space missions are already in applied or planned in this field1,2,3. Deep learning-based pose estimation has become a research hotspot in recent years4. Most existing space object pose estimation approaches mainly estimate the relative pose between a space object and a reference frame using the current frame, with an implicit assumption of possessing a CAD model for a given object instance. The availability of specific CAD models for individual satellites poses challenges in extending the generalization of the approach to novel and previously unseen space instances.

To address this issue, some studies employ category-level models to estimate the pose of the space target. They typically train on a multitude of CAD data within that specific category to enhance the model’s generalizability within that category. However, this approach comes with certain limitations. Firstly, these models are influenced by the diversity of categories present in the learning dataset, leading to suboptimal generalization to unknown category targets. Additionally, the construction of the 3D CAD database used for training models often necessitates manual effort and domain knowledge.

An alternative approach involves leveraging SLAM technology for pose estimation, where non-cooperative target objects are reconstructed in real-time, eliminating the necessity for pre-existing 3D models of the objects. Nevertheless, employing SLAM directly for space object pose estimation encounters two challenges. Firstly, in scenarios where non-cooperative targets exhibit rapid rotation, traditional feature point matching methods often yield suboptimal results. Additionally, errors tend to accumulate when integrating observations with inaccurate pose estimates during tracking via reconstruction. These accumulated errors adversely impact subsequent frame-to-frame model tracking.

To address the aforementioned limitations, this study aims to achieve accurate and robust 6D pose estimation without reliance on instance- or category-level 3D models, laying the groundwork for subsequent tasks such as 3D reconstruction and capture of non-cooperative targets. The comparison between the proposed method with other methods are shown in Fig. 1. We propose a model-free estimation pipeline consisting of three parts to accurately estimate the target pose. First, an image segmentation method and hierarchical shape matching is proposed to obtain the initial object location and rotation. Then, a keypoints extractor is proposed to extract sub-pixel-level keypoints from input images. And a multichannel superglue network with triple loss is designed to obtain the matching pairs of keypoints in the body reference system, following by a non-iterative mismatch removal approach to further enhance the matching accuracy. After that, a pose graph optimization algorithm with a dynamic keyframe pool is designed to reduce long-term cumulative pose errors.

Comparison of the proposed method with other methods. (a) keypoint matching method: Requires precise 3D models and can only perform pose estimation for specific targets5. (b) SLAM-based method: Performs poorly in in rapid rotations or other dynamic movements of the nonoperative target6. (c) Proposed method: Utilizes image segmentation and shape prior to obtain initial frame mask, followed by deep feature point matching to achieve pose tracking in scenarios with rapid rotations.

The proposed model offers the following advantages over existing algorithms:

-

1.

An integrated approach for non-cooperative space target pose estimation is proposed, and a SegFormer based segmentation model integrated with a localized-class-region-learning module is proposed to extract the initial target mask.

-

2.

A feature point extraction and matching algorithm based on multi-dimensional subpixel convolution features is proposed, addressing the issue of inaccurate feature point matching caused by the rapid rotation of non-cooperative targets.

-

3.

A graph optimization method based on a dynamic keyframe memory pool is proposed, reducing the cumulative error in long-term pose estimation drift.

-

4.

A new non-cooperative target dataset is created. The dataset contains nine different types of non-cooperative targets, and most of the models are from the catalogue of 3D models from NASA. The targets in space are collected under different illumination conditions, with different rotation rates and different image resolutions, to train and verify the proposed models.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows: related research on object pose estimation is discussed in “Related work” section. The pipeline for pose estimation based on keypoint matching and graph optimization is presented in “Methodology” section. The experimental results and discussions are presented in “Experiment results and discussion” section. The conclusions of the work are presented in “Conclusion” section.

Related work

Depending on whether or not to use predefined 3D models, research on non-cooperative space object pose estimation can be categorized into the following two groups: CAD-known methods and model-free pose estimation methods.

CAD-known methods

When the CAD data of the space object is available, significant progress has been made in non-cooperative target pose estimation7,8. Tae et al.9 first combined the CNN-based architecture to extract the object keypoints from a single image, and a PnP model is designed to calculate the relative pose from the 2D keypoints and the associated 3D model coordinates. Similarly, Huo et al.10 introduced a new one-stage neural network to detect the object and estimate the 2D locations of the projected keypoints from the reconstructed 3D data. Subsequently, the satellite pose is calculated by the 2D-3D correspondences generated by keypoints regression model. Hu et al.11 designed a feature pyramid network (FPN) to extract keypoints at various scales and regress the 2D projections of predefined 3D points following by the PnP solver. Wang et al.12 designed a transformer-based keypoints generation network and constructed the integrated loss function to estimate the correct object keypoints. Then estimate the satellite pose with 3D-2D projection. Besides, Liu et al.13 processed the LIDAR sensor data and estimated the satellite pose in close range.

Some researchers also estimate object pose in a regression way. Sumant et al.14 used a convolutional neural network (CNN) comprising three heads to estimate the object location, classify its discrete coarse attitude labels, and regress coarse attitude into a finer estimation. Deng et al.15 introduced the YOLOv5 and HRNet models to detect the object and classify its attitude. In order to enhance the pose estimation precision with various illumination conditions in a space environment, Afshar et al.16 devised a transfer learning method incorporating object augmentation to directly classify the satellite class and regress its pose.

Model-free methods

In the case of non-cooperative space targets with unknown three-dimensional structures, several algorithms first reconstruct the space target to generate the 3D model and then estimate the object pose. Lei et al.17 developed an integrated framework to estimate spacecraft pose with three branches. One branch is dedicated to estimating the satellite pose from the current image, and another part simultaneously extracts keyframes. The final branch is responsible for establishing the local 3D map. Li et al.18 designed a point cloud pose graph optimization algorithm to maintain the global satellite structure. Subsequently, an extended Kalman filter is introduced to calculate the object pose and inertia values by the motion sensors. Hai et al.19 proposed a shape-constraint recurrent matching framework for 6D object pose estimation. Zhang et al.20 designed a novel solution by reframing category-level object pose estimation as conditional generative modeling. The algorithms most similar to the proposed method are BundleTrack21 and BundleSDF22. BundleTrack proposes a general framework for 6D pose tracking of novel objects without relying on 3D models, leveraging deep learning for segmentation and feature extraction, along with memory-augmented pose graph optimization for spatiotemporal consistency, achieving state-of-the-art performance in challenging scenarios and real-time processing at 10 Hz. Similarity, BundleSDF is a near real-time 6-DoF tracking method for unknown objects from monocular RGBD video, incorporating neural 3D reconstruction, which handles large pose changes, occlusions, and untextured surfaces without prior information, outperforming existing methods on HO3D, YCBInEOAT, and BEHAVE datasets.

There is limited research on model-free methods for space-object pose estimation. In the domain of everyday object pose estimation, researchers explore pose studies through methods such as 3D reconstruction and pose graph optimization. Specifically, approaches like frame-model Iterative Closest Point (ICP)23,24, 3D likelihood maximization25 and probabilistic data association26 have enhanced the accuracy of 3D model reconstruction. Additionally, methods such as those proposed in27,28 use optimization techniques based on bundle adjustment to correct long-term cumulative errors in the pose estimation process. In general, existing model-free models for daily object pose estimation typically employ dense point features for matching and bundle adjustment. BundleTrack and BundleSDF struggle to adapt to the issue of large-angle matching when both the chaser and the target undergo pose changes in space, and they also do not consider the problem of determining the target’s position and rotation under initial frame conditions. Given the complexities arising from different rotation speeds and varying lighting conditions in the context of non-cooperative space objects, a novel framework is required to achieve robust and accurate pose estimation.

Methodology

To reduce feature matching errors under different rotation speeds of the target and minimize long-term drift estimation error, this work aims to efficiently and accurately estimate the space target pose. We suggest an integrated pose estimation framework to achieve high estimation accuracy. The image input sequence is first processed by object detection model to extract target position and remove the background. To extract the subpixel level keypoints from detecrted image area, a keypoint extraction module and subpixel block are then proposed. The matched pairs of keypoints in the body reference system are obtained using a triple-loss multichannel matching network. The target rotation matrix is then extracted using the keypoints that were successfully matched, and a mismatch removal method is then suggested to further improve the matching accuracy. Finally, a pose graph optimization with dynamic keyframe pool is proposed to obtain the target pose relative to initial frame. The overview of the suggested approach is depicted in Fig. 2.

Initial pose estimation

Consider a rigid space object that lacks both a specific 3D model and a category-level model database for training purposes. The goal in this paper is to track the object’s 6D pose changes from the start of tracking, meaning tracking the relative transformation \(P_0 \rightarrow \tau\) in SE(3), where \(\tau\) is any frame from the initial time \(p = 0\) up to current time \(t\). The algorithm have three inputs, which include: (1) \(I_\tau\): RGB-D data sequence from time 0 to time \(t\). (2) \(B\): A segmentation mask in the initial frame \(I_0\) that defines the region of the target object. (3) \(P^C_0\): The object’s initial pose in the camera’s coordinate frame \(C\).

In order to obtain the segmentation mask \(B\) in the initial frame \(I_0\), we propose a SegFormer based segmentation model to obtain the target mask from the image, as shown in Fig. 2a. Considering the unknown shapes of various non-cooperative targets, the segmentation model is trained by public spacecraft dataset29 to ensure it can effectively detect various types of non-cooperative targets and segment different parts of the targets, including the main body, solar panels, etc.

To enhance the segmentation model’s adaptability to different contexts and varying space lighting conditions, this paper designs a localized-class-region-learning module to improve the segmentation performance. Specifically, given x, we utilize the semantic segmentation network \(\varphi\) to extract the feature maps of the two partially overlapping patches. We denote the overlapping region as \(O_1\) and \(O_2\) from \(Crop_1\) and \(Crop_2\) respectively. We argue that the output features of the overlapping regions should be insensitive to the context. Therefore, we constrain each feature in \(O_1\) to be consistent with the corresponding feature at the same location in \(O_2\), which can be formulated as:

where \(\varphi (O_1)_k\) denotes i-th feature in the overlapping region \(O_1\), r denotes the exponential function of the cosine similarity as the one in pixel contrast.

After the segmentation mask is obtained, the object’s initial pose in the camera’s coordinate frame \(C\) is retrieved by two optional methods. One is using the default identity matrix as the initial pose. In this scenario, the part segmentation mask from the model’s initial frame can also provide additional prior information for subsequent capture tasks. Another way is to determine the object’s absolute pose based on the hierarchical shape prior model, proposed by Ren et al.30. As shown in Fig. 2 Firstly, some common predefined non-cooperative target shapes, such as adjacency, reflective symmetry, and rotational symmetry, are predefined. These shapes include various configurations that align with the typical component types and constraints found in space object structures, providing a foundational model for understanding and reconstructing the physical makeup of these objects. The prebuilt hierarchical shape model is established from the structural laws of space objects, which is defined as \(\mathscr {O}\). \(\mathscr {O}\) is a 2-tuple:

where \(V\) represents the types of object components and \(C\) indicates the constraints among object components30. By matching the predefined shapes and initial target mask, the optimal pose \(T^*\) is determined by maximizing a posterior probability that integrates the object’s structural probability, conditional probability of types of constraints given their components, and the match degree between the input image and the projected object’s features30. It is worth noting that the image segmentation method mentioned in this paper for initial pose determination exhibits a certain degree of robustness, which is particularly relevant for damaged satellites-a common scenario in space capture, repair, and other related tasks.

Keypoints extraction method

Inspired by SuperPoint31, This paper propose a CNN based keypoints descriptor to extract the local features from the space target images. The model performs detection and description using a single CNN model that shares a backbone and has multiple heads for keypoints and description maps. By using a homographic matching process, the detector head is trained in a self-supervised manner. By locating keypoints on various distorted versions of the same image and combining them, the true keypoints are created. The model learns to predict the locations of the keypoints by including cross-entropy loss. True correspondences between points in an image and its distorted version can be established through the application of random homographies. The objective of the descriptor head is to minimize the spatial gap between descriptors for each pair of keypoints.

The output of the keypoints extraction network includes a score map with the shape of \(H\times W\), and a description map with the shape of \(H\times W\times 256\). The score map describes the probability that each pixel in the original image is a feature point. The feature points are then extracted based on the score threshold, and the coordinates are pixel-level integer coordinates, which limits the accuracy of keypoints location accuracy and following pose estimation precision. To solve this problem, this paper integrate the keypoint extraction network with a sub-pixel module. Firstly, a feature point coordinate sub-pixelization module is designed, which integrates the neighborhood pixel features with the original feature points to achieve sub-pixel precision for each feature point. The descriptor is then modified to calculate the corresponding sub-pixel descriptions with the modified feature points. A bilinear interpolation approach and an L2 regularization method are built to improve the descriptor precision. The proposed keypoints extraction module with the subpixel module is demonstrated in Fig. 3.

As shown in Fig. 3, the score map S is generated by the feature encoder-decoder backbone. For each non-overlapping \(N \times N\) pixel window, a non-maximum value suppression is designed to obtain the coarse feature map \(S_{NMS}\), the non-maximum value suppression equation is shown in Eq. (2):

where \(s_{\max }=\max (s(i, j)), \quad 0 \leqslant i, j<N\), and s is the pixel window.

After NMS, pixel points that larger than threshold th are extracted as the integer coordinate set p. For each feature point \(\varvec{p}_i=\left( x_0, y_0\right) _i\) in p, its \(5\times 5\) local pixel window reflects the probability of the point as a feature point, and a integral regression is applied on the local window to calculate the keypoint coordinate expectation. Besides, in order to maintain differentiable characteristics, we introduce a Softargmax method for the calculation of the coordinate expectations. The subpixel offset expectations \((\delta x, \delta y)\) in the x and y directions are obtained separately, as shown in the Eq. (3).

where i and j represent the pixel offsets in the x and y directions, respectively. And their values are \({-2, -1, 1, 2}\). \((x_i,y_i)\) means the keypoint coordinates with bias. By obtaining subpixel offset \((\delta x,\delta y)\), the revised subpixel level keypoints coordinates\((x^{\prime }, y^{\prime })\) are expressed as:

Figure 3 also shows the modified descriptor decoder with the sub-pixel module. The bilinear interpolation operation for the generated sub-pixel keypoint is carried out by the descriptor decoder in this paper. Each keypoint has a 256-dimensional vector serving as its descriptor. The L2 normalization method is then used to regularize these vectors to produce the final 256-dimensional descriptor. The equation is shown below:

where \(\mathbf {x_{nor}}\) is the normalized keypoints descriptor.

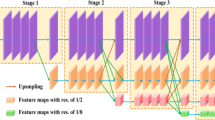

Multi-dimension keypoints matching model

Inspired by Superglue32, this paper proposes a self-attention multi-dimensional keypoints matching model. The core idea of the self-attention keypoints matching is to transform the matching problem into an optimal transportation problem to joint encode the vectors of keypoints and descriptors. The Sinkhorn algorithm33 is applied to iteratively obtain the best matching scores. The proposed matching model is shown in Fig. 4. Due to their repeating location, the keypoints extracted from the input image are first categorized and processed. By a NMS process, the processed keypoints set becomes:

where \(P_{o,d}\) means the keypoints both in RGB and depth feature maps. \(P_o\) and \(P_d\) represent the keypoints from the RGB feature map and depth map, respectively. The camera intrinsics are used to convert keypoints from the image coordinate reference to the body coordinate reference in order to unify the keypoint coordinate system.

The keypoints set is then introduced separately into the matching backbone to extract the matching descriptors by the cross-attention and self-attention modules. A score matrix based on the matching descriptors can be used to compute the assignment map A. We design the multi-dimensional pairwise score as the similarity of matching descriptors; the score map is shown in Eq. (7).

where \(<\cdot>\) means the inner product. \(\lambda 1\) and \(\lambda\) are the super parameters to control the weights between the RGB score map, the depth score map, and the integrated score map. The magnitude of the matching descriptors represents the estimation confidence of the keypoints extractor.

To find the correct matching pairs from the matching score, the optimization problem is treated as the optimal transport problem related with the two discrete distributions a and b with scores S. Its entropy-regularized representation inherently yields the desired soft allocation, and the Sinkhorn algorithm can solve it quickly34. While our multi-dimensional matching approach introduces additional computation in the preprocessing stage, this overhead is limited to a one-time cost matrix generation before the Sinkhorn algorithm begins.

The proposed matching model is trained in a supervised way from true matches M. The matching pairs are generated from ground truth poses. Specifically, the image keypoints are firstly extracted from both RGB and depth images, and transformed into body coordinate with camera intrinsic. The groundtruth rotation matrix is applied to project the keypoints into another image. And the reverse transformation process is applied to generate image coordinate keypoints. The L2 distance formula is utilized to find the best matching pair between the two keypoints set. To help the model learn the correct matching scores, we design an integration loss function that combines the triple loss and negative log-likelihood (nll) loss. The loss is shown in Eq. (8):

where A represents the assignment matrix. The \(D_{ap}\) and \(D_{an}\) mean the matching score with positive distance and negative distance. In other words, \(D_{ap}\) is the sum of matching scores for true matching pairs, and \(D_{an}\) is the matching scores for the mismatching pairs with the highest scores margin is the non-negative factor. The loss function is applied to increase the \(D_{ap}\) and decrease the \(D_{an}\).

By applying the keypoints extractor and matching module, the matching keypoints are prepared to estimate the target pose. However, due to the pixel error and mismatched points, the pose accuracy usually cannot meet the requirement. This work proposed non-iterative approaches to accelerate the estimation process and enhance the pose precision. The details of the algorithm are illustrated in Algorithm 1:

Algorithm 1.

As shown in Algorithm 1, the matched pairs \((M_i,M_j)\) are the outputs from the proposed matching model. And the generated matched keypoints \((Mkpts_i, Mkpts_j)\) are sampled by the farthest point sampling algorithm (FPS). The farthest point sampling algorithm is first proposed by PointNet35. It samples the farthest point for each sample and performs distance updating to enhance the pose estimation accuracy. The adjusted FPS approach36 is introduced to reduce the processing time while keeping its performance. After that, a Hessian matrix H is produced by the two pairs of matched keypoints, and the rotation matrix R is generated by the singular value decomposition algorithm. Then the pose value P is generated from the rotation matrix R by Rodrigues’ rotation formula37 and the translation T from the object detection results. To remove the mismatching points, we predict the \(Mkpts_j^{'}\) of image j from image i by the retrieved rotation matrix. The keypoints distance between \(Mkpts_j^{'}\) and \(Mkpts_j\) are sorted, and the mismatched keypoints are removed from \(Mkpts_i\) and \(Mkpts_j\). The pose are then estimated by the selected keypoint pair. After removing the mismatching keypoints, a preliminary pose is computed by \({\textbf{P}}_t = \textbf{P}_{t-1} P_t^{t-1}\) where \(P_t^{t-1}\) is the best estimated pose between the two match pairs.

Pose graph optimization (GO) with dynamic keyframe pool

A pose graph optimization step is subsequently proposed to refined \({\textbf{P}}_t\) and reduce the long-term drifting pose error. The pose graph can be represented as \(G=\{V, E\},|V|=k+1\), where each node means the target pose at the current frame and k selected frames \(\tau \in \left\{ t, t-t_1, t-t_2, \ldots , t-t_k\right\}\). Each pose can then be indicated as \(\textbf{T}_i, i \in |V|\), where V includes current pose and previous k poses. Spatiotemporal coherence is established by minimizing the overall energy of the graph E. The equation is as follows:

where The energy \(\textbf{E}_f\) represents the errors computed from feature matching results. The equation of the \(\textbf{E}_f\) is:

where \(C_{i, j}\) is the corresponding keypoint between frames i and j. \(\textbf{T}_i\) is the preliminary pose. p represents the unprojected 3D points in the camera reference, and \(\rho\) means the M-estimator. \(\omega _i\) is the corresponding keypoint confidence weights. The goal of the graph optimization is to find the optimal poses, such that:

where \(\xi _i=\log \left( \textbf{T}_i\right) \in\) is the pose expressed in Lie Algebra, comprising three parameters for translation and three parameters for rotation. A typical Gauss-Newton algorithm with the Preconditioned Conjugate Gradient solver38 is introduced to solve the nonlinear least squares optimization process.

\(T_0\) is chosen as the base pose since the initial frame remains unaffected by tracking drift. During the dynamic keyframe updating process, this paper set the frame number of the dynamic keyframe pool as k. When the frame number is less than k, we process the current frame and add it to the keyframes. When the num reaches k, the criterion for updating keyframes is based on the minimum rotation angle error compared to the current frame. Specifically, the rotation angle error is calculated between the current frame and each historical frame, and the k frames with the smallest errors are selected as keyframes. The updated keyframes are then incorporated as nodes in the pose graph optimization. The optimized results simultaneously update the poses of both the current frame and the keyframes. Taking into account the scenario of loop closure detection, the initial frame is consistently placed within the dynamic keyframe pool. When the rotation angle meets the conditions for loop closure, employing direct matching with the initial frame proves effective in eliminating accumulated pose estimation error. Compared to the traditional matching methods, the proposed dynamic keyframe pool enables discontinuous matching, allowing the current frame to be associated with multiple historical frames, which is crucial for handling abrupt occlusions and target reappearances, which are common in space operations.

The rotation matrix of the non-cooperative targets is retrieved in the chaser’s camera frames, implying that the observed change in pose is a combination of the target’s and the chaser’s rotations. Considering that the pose of the chaser serves as prior knowledge and is already known, it is possible to establish the true target pose through in-orbit measurement of its relative motion, as perceived by the chaser. According to the description in39, the target rotation matrix is shown in Eq. (12):

where \(\mathfrak {R}_{chaser}\) is the relative rotation of the chaser, and the \(\hat{\mathfrak {R}}\) is the retrieved rotation matrix from the proposed pose estimation model.

Experiment results and discussion

Data setup

In this research, nine different types of non-cooperative targets are designed to generate the non-cooperative target datasets. The targets are shown in Fig. 5. The 8 types of targets include Aura, Cubesat, Dawn, Hubble, Jason, Deep Impact, Cloudsat, and Acrimat. Most of the models are taken from NASA’s catalogue of 3D models, and other models are obtained from the public CAD model library. In these targets, Cloudsat, Jason and Cubesat have simple geometries with fewer strong features, while Aura, Acrimat and Dawn have more intricate geometry but more strong image features. Finally, the Deep Impact and Hubble model include difficult contours and curved surfaces, which are relatively difficult for keypoints matching. The mission satellite (chaser) is assumed to orbit the target in a circular trajectory, as shown in Fig. 6. The camera configuration from the chaser, the orbit lighting condition, and the target rotation rate are adjusted and tested to verify the robustness of the proposed method.

To train and evaluate the deep learning-based pose estimation algorithms, seven of the nine targets are sampled with different rotations at an interval of 1°. For each image, we randomly select another five different images with same target as image matching pairs. The random rotation difference between the two images in one image pair is within 30°. The dataset is randomly separated into a training set and a test set. The training set contains 9252 image pairs, while the test set contains 2313 image pairs. To further verify the generalization ability of the proposed model, the other two targets (including CloudSat and Acrimsat, not used in the training set) are sampled to generate the unsupervised test dataset, which contains 660 image pairs. The original RGB and Depth images from all data sets are with the size of \(1920 \times 1080\).

This paper employs Blender with Python scripts to simulate the perception images. The proposed deep learning based models are implemented using the Pytorch framework, and the graph optimization algorithm is achieved based on Ceres Solver. All experiments are conducted using a GeForce RTX 3090 GPU and 24GB of RAM, as well as an i7 CPU with 16GB of RAM. The learning rate is initialized as \(1 \times 10^4\). Some important superparameters, such as the keypoint extraction threshold and criteria for filtering outlier keypoints, are obtained by employing the grid search method to find their optimal values.

Evaluation metrics

This work introduces the area under curve (AUC)40, recall, the Mean pose error, and the matching scores31 to analyze the performance of the proposed pose estimation methods.

The definition of the area under curve is as follows:

where \(c_i\) is the point of the box that hits the curve, \(f\left( c_i\right)\) is the function value at that point, and \(\Delta x\) is the width of the base of each rectangle. In the matching task, recall is the fraction of the correct matching points that were retrieved. And the Matching Score (MS) is the average ratio of correct matches to the total detected keypoints. The definition is:

where \(D_i\) and \(C_i\) is the detection number points and the correct matches related to image i, respectively. N is the total number of images.

The average mean pose error is defined by the mean square error between the predicted pose and the true pose. The definition is shown below:

where \(P_i\) is the true groundtruth, and \(\tilde{P}_i\) is the predicted pose by the proposed model.

Image segmentation results

To obtain the initial segmentation mask, the proposed segmentation method is trained via the public dataset29 consists of 3117 images with uniform resolutions of 1280 \(\times\) 720 pixels. It includes masks of 10350 parts of 3667 spacecrafts. The SegFormer MiT-B5 network is introduced as the backbone, which pretrained on ImageNet-1k dataset. The method is trained with the batch size of 3, and the training takes 40k iterations. After training, the model performs inference on the proposed dataset, obtaining the initial mask for each target. Samples of some inference results are shown in Fig. 7. It can be observed that the model demonstrates satisfactory segmentation results under various types of targets, different contextual conditions, and different lighting conditions.

To further verify the advanced nature of the proposed method, this paper compares it with other state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods on the public spacecraft dataset29. The segmentation results are shown in Table 1. The comparison mIOU results29 in Table 1 shows that the proposed localized-class-region-learning module can effectively improve the mIOU scores of object part segmentation. Compared to the currently best methods, improvements of \(0.2\%\), \(0.5\%\), and \(8.7\%\) were achieved in the ’body,’ ’solar panel,’ and ’antenna’ categories, respectively.

Pose estimation results with different matching condition

Different matching models

Figure 8 shows the different ROC curves and AP scores by different image matching backbones. Seven SOTA keypoints extractor + image matching architectures, including the SIFT41, Superglue32, HardNet42, KeyNet43, LoFTR44. Figure 8a–c illustrate the matching results with different target rotation rate. As shown in Fig. 8a, the HardNet+Superglue model achieve the highest AUC score, while the proposed model obtain the second place AUC score, which is 0.85. Actually, most of comparison models achieves acceptable performance with the target rotation rate of 0–10°/s. As for the target rotation rate from 10 to 20°/s, and from 20 to 30°/s. Figure 8b and c have illustrated that the proposed method achieves the best performance from 10 to 30°/s. The AUC score of the proposed method achieve 0.70 when the target rotation rate ranges from 20 to 30°/s.

The AUC and APE scores in Table 2 have verified that the proposed method achieves competitive performance, especially with the large target rotation rate. The mAPE and mMS of the proposed method obtain \(0.63^{\circ }\) and 0.767, respectively. Compared with the proposed method, the HardNet-superglue and the LoFTR approaches obtain the second-best performance. When the rotation rate less than \(10 ^{\circ }\). The HardNet-superglue and LoFTR approaches show their efficiency in extracting the local features from RGB images. When the rotation rate is higher, the proposed approach has advantages in extracting keypoints from both RGB images and depth images.

Large rotation rate

To further verify the effectiveness of the proposed method, the image pairs with rotation difference from \(30^{\circ }\) to \(45^{\circ }\) is tested. The results in Fig. 9 and Table 3 verifies that the proposed remains the best performance when the target rotation rate ranging from \(30^{\circ }\) to \(45^{\circ }\). The mUAC and mMS scores of the proposed method achieve 0.636 and 0.418, respectively, which outperform the compared models with substantial advantages.

Figure 10a and b show the APE and AUC scores of the proposed method corresponding to the true rotation degree. According to Fig. 10a, the APE is less than 0.02 rad when the target true rotation rate is less than \(25^{\circ }\). When the rotation rate is larger than \(25^{\circ }\), the APE is slower increasing with the rotation rate. And the peak APE achieve 0.05 rad When the rotation rate is \(44 ^{\circ }\). The results is expected because with rotation become larger, the overlap area between the two image pairs are decreased, resulting in the less correct keypoints pairs between the two samples, and leading to the increase of the pose error. The AUC scores in Fig. 10b demonstrate a similar situation.

Different lighting condition

The lighting condition is the crucial factor in the space environment that affects the image-based matching model. Four different lighting conditions are verified in this work, as shown in Fig. 6. In Fig. 6, lighting condition 1 and 4 is the case where the sun angle is at \(90^{\circ }\) and \(0^{\circ }\) to the camera view orbit, while lighting condition 2 and 3 is the case where the sun angle is at \(60^{\circ }\) and \(30^{\circ }\) to the camera view orbit. The pose estimation results are illustrated in Table 4. The results are expected, and the proposed model achieves the best scores under lighting condition 3. The APE scores of lighting conditions 1 and 4 are slightly reduced due to the shadows and occlusions under the lighting conditions.

Figure 11a and b shows some image matching results corresponding to Aura that affected by the lighting. Figure 11a demonstrates that the proposed method is verified its effectiveness under back-light condition. Figure 11b demonstrate the blurring condition of the non-cooperative target under certain angle between the sun and the chaser camera. The matching results in Fig. 11a,b and Table 4 prove that the proposed approach shows stable matching performance under various lighting conditions

Different image resolution

In the approaching process of the chaser, the distance between the chaser and the target is varied due to different control strategies. And due to different camera configurations and divergent target sizes, the target’s image resolution is different in the captured images for different tasks. This work tested the matching performance of the proposed model with the different image resolutions of the target. Table 5 shows the matching results from the proposed dataset with different resolutions. According to Table 5, the matching performance is slightly decreased with the lower image resolution. The mAUC and the APE achieve 0.703 and 0.024, respectively, when the target size is \(115 \times 115\) pix. In our opinion, the major reason for the APE score decreasing with the image resolution is the lack of keypoint pairs when the rotation rate is greater than \(10^{\circ }\). In practice, by equipping higher resolution cameras and integrating multi-band sensor information, this problem will be alleviated. The low-resolution matching results in Fig. 11c have revealed that, despite the lack of matching keypoints, the proposed model finds the matching keypoints with acceptable precision.

Graph optimization (GO) results

Figure 12a and b show the pose estimation results with the proposed graph optimization results. The figure illustrates the cumulative pose estimation results for the test target rotating 720° at different rotation rates. As indicated by the dashed line in the figures, the estimated pose errors undergo accumulation through computation, leading to cumulative errors in the relative pose with respect to the initial frame. After applying the proposed pose GO algorithm, the pose estimation results undergo joint optimization, ensuring that the maximum error during a full rotation is within 1° in the second revolution. In detail, since the initial frame remains in the dynamic keyframe pool throughout the optimization, when the rotation angle exceeds 330°, there is feature overlap between the current frame and the initial. Consequently, direct matching with the initial frame is utilized to eliminate cumulative errors, preventing their accumulation into the next rotation cycle. The solid curves in the graph also indicate that cumulative errors gradually accumulate in the first stages, followed by a rapid decrease through direct matching with the initial frame by the proposed GO method.

The GO algorithm also performs a unified optimization on historical keyframes, improving the estimation accuracy for each keyframe. In the second revolution, pose information is directly obtained through the GO algorithm between the current frame and keyframes instead of cumulative acquisition (as in visual odometry), preventing subsequent errors from accumulating. The visualization of pose estimation results with 3D bounding boxes is presented in Fig. 12c. There is no feature overlap in the object when the cumulative pose changes from \(T_{0} + 90^{\circ }\) to \(T_{0} + 300^{\circ }\) in the first revolution; the pose errors are continuously accumulating. When the pose reaches around \(T_{0} + 330^{\circ }\), there is feature overlap between the current frame and the initial frame. By applying the proposed GO algorithm, the joint pose optimization is achieved for the current frame, the initial frame, along with the intermediate keyframes. Then The current pose and the keyframes pose are both corrected after the first revolution. Figure 12d illustrates the visualized estimation results of the Aura satellite in the second revolution process. Due to the optimization process using multiple keyframes by the proposed model, each relative pose is optimized in a sequential order and the accumulated pose error remains within 1°. Through a similar process, it can be inferred that the pose error does not accumulate during the subsequent revolution process.

Ablation experiments

Table 6 is designed to express the quantitative results of different modules on the test dataset. In Table 6, with subpixel extractor and multi-dimension matching, the proposed matching model achieves 0.034 and 0.012 scores, respectively. As for the mMS score, multi-dimension matching and postprocessing contributed to the improvement of scores of 0.206 and 0.003, respectively, which further verified the advantages of the proposed multi-dimension matching module. Above all, by integrating the subpixel extractor, the multi-dimension matching, and the non-iterative postprocessing modules, the designed method achieves the APE score of 0.011 rad, and the mAUC score of 0.767.

We also test the different matching performances of different targets, as shown in Fig. 13. According to Fig. 13, Jason achieves the best APE score due to its obvious context feature and geometry structure. The highest APE score corresponds to Deep Impact, which is 0.029. As shown in Fig. 5, the soft material of the Deep Impact surface makes generating correct keypoints and descriptors difficult, resulting in relatively large pose estimation errors.

We also illustrate the generalization ability of the proposed model in Table 7. The Acrimsat and Cloudsat which not utilized in the matching training set are introduced to verify the pretrained model. In Table 7, the APE scores of the The Acrimsat and Cloudsat achieve 0.009 and 0.001, respectively. And their mMS scores are 0.971 and 0.912, respectively. Fig. 11d and e have shown that the object keypoints are correctly matching under front light and back light, respectively. In conclusion, the matching performance of the proposed model on the unseen targets verifies its generalization ability on multiple non-cooperative targets.

The matching results of samples from SPEED++ dataset45. (a) Matching results at different scales; (b) Matching results under extreme lighting conditions and significant background variations.

The depth information of the object is typically provided by stereo cameras or depth cameras, often accompanied by some level of error. Errors in depth information can directly impact pose estimation. Table 8 assesses the influence of random Gaussian errors in depth on pose estimation under different depth conditions. The graph illustrates that the errors in pose estimation for different target poses increase with the growth of relative depth errors. When the relative error is no greater than 20%, the maximum relative error is within 2°. The results indicate that the pose estimation algorithm proposed in this paper demonstrates robustness to depth errors within a certain range. When the depth information was missing, the algorithm defaults to assuming that all points are at the same depth, leading to larger errors compared to scenarios with available depth information.

To further validate our method’s generalization capability, we conducted additional experiments using the SPEED++ dataset45. While SPEED++ offers limited target types and lacks depth information compared to our original dataset, it provides greater diversity in target structures and background variations, making it an ideal choice for testing our algorithm’s generalization ability. Figure 14 illustrates the experimental results on the SPEED++ dataset. Specifically, Fig. 14a demonstrates the algorithm’s capability to match objects at different scales, which is crucial for space applications where target distances can vary significantly. Figure 14b showcases the algorithm’s robustness under extreme lighting conditions and background variations, which is vital for space operations with dynamically changing illumination and backgrounds. These results not only prove our method’s adaptability to diverse space scenarios but also lay a solid foundation for subsequent pose estimation and bundle adjustment procedures, thereby enhancing the credibility and applicability of our research in real-world space applications.

While the primary focus of this paper is on algorithmic innovation and performance evaluation across various space scenarios, we have conducted preliminary embedded validation tests on common platforms like Jetson NX and RKNN 3588, achieving inference speeds of 4.76 FPS and 2.5 FPS respectively. These initial results not only suggest the feasibility of embedded deployment but also highlight the algorithm’s adaptability to resource-constrained environments, paving the way for future optimizations tailored to space-specific hardware and environmental conditions.

Conclusion

In this paper, we present a deep learning model for predicting the pose change of unknown space targets. The segFormer based segmentation method is first designed to extract the initial target mask. The developed model then utilizes subpixel-based feature-extracting techniques to detect and extract keypoints features from RGB and depth images. And a multi-dimension matching based keypoints matching algorithm is proposed to achieve correct matching pairs. To further enhance the estimation accuracy, a non-iterative approach is designed to remove the outliers and generate the rotation matrix. Finally, the pose graph optimization method with dynamic keyframe pool is proposed to reduce the cumulative error in long-term pose estimation drift.

The model is compared with multiple SOTA approaches, showing outperforming estimation results. The mAPE and mMS scores of the proposed approach are 0.011 and 0.767, respectively. After pose graph optimization, the estimation error of the relative pose with respect to the initial frame has been reduced to within 2°. Multiple experiments have been applied, and the proposed algorithms have been tested under different lighting conditions, different rotation rates, different image resolutions, and with out-of-domain targets. The matching results from various experiments have shown its robustness and transferring ability. Depth information with various random errors are introduced to validate the performance of pose estimation under practice situation. In addition to our contributions to space object pose estimation, we believe that the methods proposed in our paper could also be beneficial for pose estimation of aerial targets, such as drones and airplanes, representing a promising direction for our future work.

There remain some further avenues to investigate. More work is needed to enhance the pose estimation’s accuracy and robustness. Also, algorithmic optimizations, parallel processing, and hardware acceleration are potential research topics to achieve faster optimization computation without compromising accuracy.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Opromolla, R., Fasano, G., Rufino, G. & Grassi, M. Pose estimation for spacecraft relative navigation using model-based algorithms. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 53, 431–447 (2017).

Reed, B. B., Smith, R. C., Naasz, B. J., Pellegrino, J. F. & Bacon, C. E. The restore-l servicing mission. AIAA Space 2016, 5478 (2016).

Sullivan, B. et al. Darpa phoenix payload orbital delivery system (pods):“fedex to geo”. In AIAA SPACE 2013 Conference and Exposition, 5484 (2013).

Kisantal, M. et al. Satellite pose estimation challenge: Dataset, competition design, and results. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 56, 4083–4098 (2020).

Bechini, M., Gu, G., Lunghi, P. & Lavagna, M. Robust spacecraft relative pose estimation via CNN-aided line segments detection in monocular images. Acta Astronaut. 215, 20–43 (2024).

Lei, T., Liu, X.-F., Cai, G.-P., Liu, Y.-M. & Liu, P. Pose estimation of a noncooperative target based on monocular visual slam. Int. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2019, 1–14 (2019).

Mu, J., Hao, X., Zhu, W. & Li, S. Review and prospect of intelligent perception for non-cooperative targets. Chin. Space Sci. Technol. 41, 1 (2021).

Song, J., Rondao, D. & Aouf, N. Deep learning-based spacecraft relative navigation methods: A survey. Acta Astronaut. 191, 22–40 (2022).

Park, T. H., Sharma, S. & D’Amico, S. Towards robust learning-based pose estimation of noncooperative spacecraft. arXiv:1909.00392 (2019).

Huo, Y., Li, Z. & Zhang, F. Fast and accurate spacecraft pose estimation from single shot space imagery using box reliability and keypoints existence judgments. IEEE Access 8, 216283–216297 (2020).

Hu, Y., Speierer, S., Jakob, W., Fua, P. & Salzmann, M. Wide-depth-range 6d object pose estimation in space. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 15870–15879 (2021).

Wang, Z., Zhang, Z., Sun, X., Li, Z. & Yu, Q. Revisiting monocular satellite pose estimation with transformer. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 58, 4279–4294 (2022).

Liu, L., Zhao, G. & Bo, Y. Point cloud based relative pose estimation of a satellite in close range. Sensors 16, 824 (2016).

Sharma, S. & D’Amico, S. Neural network-based pose estimation for noncooperative spacecraft rendezvous. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 56, 4638–4658 (2020).

Deng, L., Suo, H., Jia, Y. & Huang, C. Pose estimation method for non-cooperative target based on deep learning. Aerospace 9, 770 (2022).

Afshar, R. & Lu, S. Classification and recognition of space debris and its pose estimation based on deep learning of cnns. In HCI International 2020-Posters: 22nd International Conference, HCII 2020, Copenhagen, Denmark, July 19–24, 2020, Proceedings, Part I 22, 605–613 (Springer, 2020).

Lei, T., Liu, X.-F., Cai, G.-P., Liu, Y.-M. & Liu, P. Pose estimation of a noncooperative target based on monocular visual slam. Int. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2019, 1–14 (2019).

Li, Y., Wang, Y. & Xie, Y. Using consecutive point clouds for pose and motion estimation of tumbling non-cooperative target. Adv. Space Res. 63, 1576–1587 (2019).

Hai, Y., Song, R., Li, J. & Hu, Y. Shape-constraint recurrent flow for 6d object pose estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 4831–4840 (2023).

Zhang, J., Wu, M. & Dong, H. Generative category-level object pose estimation via diffusion models. Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst.36 (2024).

Wen, B. & Bekris, K. Bundletrack: 6d pose tracking for novel objects without instance or category-level 3d models. In 2021 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 8067–8074 (IEEE, 2021).

Wen, B. et al. Bundlesdf: Neural 6-dof tracking and 3d reconstruction of unknown objects. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 606–617 (2023).

Xu, B. et al. Mid-fusion: Octree-based object-level multi-instance dynamic slam. In 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 5231–5237 (IEEE, 2019).

Runz, M., Buffier, M. & Agapito, L. Maskfusion: Real-time recognition, tracking and reconstruction of multiple moving objects. In 2018 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR), 10–20 (IEEE, 2018).

Ren, C. Y., Prisacariu, V., Murray, D. & Reid, I. Star3d: Simultaneous tracking and reconstruction of 3d objects using rgb-d data. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, 1561–1568 (2013).

Strecke, M. & Stuckler, J. Em-fusion: Dynamic object-level slam with probabilistic data association. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 5865–5874 (2019).

Slavcheva, M., Kehl, W., Navab, N. & Ilic, S. Sdf-2-sdf: Highly accurate 3d object reconstruction. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 11–14, 2016, Proceedings, Part I 14, 680–696 (Springer, 2016).

Wen, B. & Bekris, K. Bundletrack: 6d pose tracking for novel objects without instance or category-level 3d models. In 2021 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 8067–8074 (IEEE, 2021).

Dung, H. A., Chen, B. & Chin, T.-J. A spacecraft dataset for detection, segmentation and parts recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2012–2019 (2021).

Ren, X., Jiang, L. & Wang, Z. Pose estimation of uncooperative unknown space objects from a single image. Int. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2020, 1–9 (2020).

DeTone, D., Malisiewicz, T. & Rabinovich, A. Superpoint: Self-supervised interest point detection and description. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision And Pattern Recognition Workshops, 224–236 (2018).

Sarlin, P.-E., DeTone, D., Malisiewicz, T. & Rabinovich, A. Superglue: Learning feature matching with graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 4938–4947 (2020).

Knight, P. A. The Sinkhorn–Knopp algorithm: Convergence and applications. SIAM J. Matrix Anal. Appl. 30, 261–275 (2008).

Sinkhorn, R. & Knopp, P. Concerning nonnegative matrices and doubly stochastic matrices. Pac. J. Math. 21, 343–348 (1967).

Qi, C. R., Su, H., Mo, K. & Guibas, L. J. Pointnet: Deep learning on point sets for 3d classification and segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 652–660 (2017).

Li, J., Zhou, J., Xiong, Y., Chen, X. & Chakrabarti, C. An adjustable farthest point sampling method for approximately-sorted point cloud data. In 2022 IEEE Workshop on Signal Processing Systems (SiPS), 1–6 (IEEE, 2022).

Sorgi, L. Two-view geometry estimation using the rodrigues rotation formula. In 2011 18th IEEE International Conference on Image Processing, 1009–1012 (IEEE, 2011).

Hildebrand, F. B. Introduction to Numerical Analysis (Courier Corporation, 1987).

Guthrie, B., Kim, M., Urrutxua, H. & Hare, J. Image-based attitude determination of co-orbiting satellites using deep learning technologies. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 120, 107232 (2022).

Kumar, R. et al. American radium society (ARS) appropriate use criteria (AUC) for locoregional gastric adenocarcinoma: Systematic review and guidelines. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 45, 391–402 (2022).

Ng, P. C. & Henikoff, S. Sift: Predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3812–3814 (2003).

Mishchuk, A., Mishkin, D., Radenovic, F. & Matas, J. Working hard to know your neighbor’s margins: Local descriptor learning loss. Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst.30 (2017).

Barroso-Laguna, A., Riba, E., Ponsa, D. & Mikolajczyk, K. Key. net: Keypoint detection by handcrafted and learned CNN filters. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 5836–5844 (2019).

Sun, J., Shen, Z., Wang, Y., Bao, H. & Zhou, X. Loftr: Detector-free local feature matching with transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 8922–8931 (2021).

Park, T. H., Märtens, M., Lecuyer, G., Izzo, D. & D’Amico, S. Speed+: Next-generation dataset for spacecraft pose estimation across domain gap. In 2022 IEEE Aerospace Conference (AERO), 1–15 (IEEE, 2022).

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52302506) and the Open Fund of the State Key Laboratory of Spatial Datum (Grant No. SKLGIE2024-Z-2-1). This work is also supported by the National Key Laboratory of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Technology and the Integrated Research and Development Platform of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhaoxiang Zhang was responsible for the experimental design and writing of the manuscript. Yuelei Xu provided the experimental equipment and funding support. Jianing Song contributed the idea for the paper and provided the data. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Z., Xu, Y. & Song, J. Robust pose estimation for non-cooperative space objects based on multichannel matching method. Sci Rep 15, 4940 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89544-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89544-6