Abstract

The effect of duration of medication with metformin and sulfonylurea (SUs) on cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and mortality events by duration of type 2 diabetes (DM) is unclear. This study aimed to investigate the effect of duration of treatment with metformin and SUs on CVD and mortality events based on DM duration in newly diagnosed DM patients. Data from three prospective cohorts of Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study (TLGS), Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), and Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) including 4108 newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes individuals (mean age, 59.4 ± 0.66 years) were pooled. Exposure was defined as the duration of metformin alone, SUs alone, and a combination of both since drug initiation. The Cox proportional hazards (CPH) model adjusted for confounders, including statin, aspirin, and anti-hypertensive, was used to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) (95% CI) for the outcomes. Cumulative exposure for metformin, SUs, aspirin, statin, and anti-hypertensive medication was calculated using the same method. The median follow-up was 20.33 ± 0.45 years. Cardiovascular events, all-cause mortality (ACM), and CVD mortality occurred in 767, 913, and 439 newly diagnosed DM patients, respectively. Metformin alone reduced the hazard of cardiovascular events, ACM, and CV-mortality by 7%, 4%, and 6%, respectively, for each year of use, respectively (p < 0.05); the corresponding values for SUs alone were 4%, 3%, and 4%, respectively (p < 0.05). The effect of metformin on reducing cardiovascular events, ACM, and CVD mortality continued until approximately 8, 10, and 5 years after the start of treatment, respectively, and then reached Plato. The effect of SUs on cardiovascular events, ACM, and CVD mortality continued to decline or reach Plato until approximately 6, 5, and 8 years after initiation of therapy and then was ineffective or reversed. The effect of the combination therapy on the reduction of cardiovascular events continued until 11 years after therapy initiation. Among newly diagnosed DM patients, metformin, with and without SUs, was associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular events, ACM, and CVD mortality for up to about one decade. The combined effect of metformin + sulfonylurea was superior to the single effect of metformin or sulfonylurea alone. The combination therapy of Metformin and SUs can still be used with good safety, especially in the first years of diabetes diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetes is one of the most common endocrine diseases, which is considered a major public health challenge worldwide1,2. Type 2 diabetes (DM) is the most common type of diabetes, accounting for more than 90% of cases3,4. The prevalence of diabetes and the disease burden related to it is increasing with the increase in obesity, lifestyle changes, and increased life expectancy in the world, especially in developing countries5,6,7. It is estimated that the prevalence of diabetes will reach 10.2% by 2030 and 10.9% by 20458. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) prediction, DM will be one of the seven main causes of death by 20309. People with diabetes are exposed to fatal complications10,11. Cardiovascular diseases (CVD), stroke, retinal damage and blindness, peripheral neuropathy, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and limb amputation are some of the most serious complications of diabetes. Also, CVD mortality from heart diseases and all-cause in diabetic patients is much higher than in the non-diabetic population11,12,13,14,15.

Control of DM can significantly reduce or delay patient complications16. Metformin, as the only biguanide among oral anti-diabetic (OAD) drugs, is widely used as the first-line OAD in the management of diabetic patients due to long-term evidence of its effectiveness and relatively fewer side effects such as hypoglycemia compared to the sulfonylurea (SUs) class17. However, monotherapy with metformin in patients with HbA1c < 7.5 may lead to a lack of diabetes control and should be prescribed to patients along with SUs drugs18,19. Patients with diabetes who are newly diagnosed and whose condition is relatively stable are often under the care of primary care physicians20. Therefore, for newly diagnosed DM (patients, according to various factors, OAD, such as metformin and SUs20, are prescribed because these antidiabetic drugs can be beneficial for these patients by reducing clinical parameters such as hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c) or reducing complications or mortality from diabetes21,22,23.

The effect of OAD drugs such as metformin and SUs has been proven in various trials to reduce the complications and mortality associated with DM22,23,24. Nevertheless, these studies are conducted in special conditions and on populations with special characteristics, in which usually the time of developing diabetes until the start of treatment is unclear, so the results of these studies cannot represent the effectiveness of a drug in society25,26. In common situations in the communities and the primary care-treatment systems of each country, these drugs are often prescribed to elderly patients who have several other diseases at the same time for a very long time, along with other drugs. The long-term consequences of using these drugs at the same time as other drugs in the community are very different compared to randomized clinical trial studies25,26,27,28,29,30.

The effectiveness of metformin and sulfonylureas in the community may differ from randomized controlled trials conducted under ideal conditions in populations with specific demographic characteristics. Furthermore, the impact of the duration of medication using these antidiabetics as first-line treatment, which is available and inexpensive compared to newer antidiabetic agents, on macrovascular complications over the long-term follow-up of new diabetes mellitus patients remains unclear. Therefore, considering the importance of this issue, in this study, for the first time in this study, we evaluated the effect of medication time of metformin and SUs on cardiovascular events, ACM, and CVD mortality cardiovascular mortality by duration of DM in newly diagnosed DM patients with a pooled analysis of three prospective cohort studies.

Methods

Study design, setting, and population

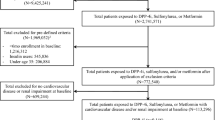

This study was approved by Shahid Beheshti, University of Medical Sciences’s ethics committee. In this observational study, the data of patients with DM who were registered and followed up in one of the three cohorts of Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study (TLGS), Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), and Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) including 34,740 participants were extracted and pooled.

In the initial data of three cohorts in the initial examination, 3601 (10.4%) people with known diabetes were excluded. FBS ≥ 126 or using any anti-diabetic medication in the first exam of each cohort was defined as known diabetes. Finally, 4108 newly diagnosed DM patients were diagnosed in three cohorts during the follow-up period. (Fig. 1)

This study was approved by the Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences ethics committee (ethical code: IR.REC.PHNS.SBMU.1402.008). The ethics committee waived the need for informed consent to participate. All methods were carried out by the Declaration of Helsinki and current ethics guidelines.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

During follow-up, patients with FBS > 126 mg/dL or taking metformin, SUs, or a combination of both were defined as newly diagnosed DM.

Inclusion criteria included patients with a definite diagnosis of type 2 diabetes based on FBS ≥ 126, age > 18 years, knowing the time of diagnosis of diabetes and the time of starting and ending the use of metformin and SUs. Receiving other anti-diabetic medications (other OAD such as SGLT2 inhibitors or insulin) at the same time, suffering from any cardiac disorders or CVD before starting to take the OAD, known diabetes in the first exam of each cohort, missing duration of metformin and SUs separately for each stage in each cohort, and the incomplete medical profile of the patients was defined as the exclusion criterion.

Data management and extraction

First, a group of epidemiology and endocrinology specialists designed a checklist to extract the desired variables from the cohorts. The desired variables for extraction were determined based on the literature review and the study’s objectives. The definition and classification of each variable were checked in different cohorts. The same definition was extracted if the cohorts used a common definition to record a variable. Due to the different definitions for each variable in the cohorts, all variables were defined and extracted with a common definition.

The extracted variables in each cohort Includes baselin data (age, sex, cohort start time, start time of each exam, end time of each exam, number of exams, sex, education level, smoking, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, marital status and physical activity (minutes per week)), FBS, Triglyceride, cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), systolic and diastolic blood pressure, creatinine, aspirin, statin and anti-hypertensive), cumulative exposure (duration of use of metformin, SUs and combination of both (Year)) and outcome (incident cardiovascular events, ACM, CVD mortality).

The time to enter each exam in a given cohort and the interval between the two exams were calculated. The calculated times for each phase were: DM duration (time from diabetes onset to the onset of outcomes) and medication time (antidiabetics, aspirin, antihypertensive, and statins).

First, the duration of diabetes was calculated. During each phase where the individual was taking antidiabetic medication, the duration of the medication was equal to half the length of the previous phase and half the length of the following phase. Similarly, if the individual was not taking medication, the duration of that phase also equaled half of the previous phase and half of the following phase.For example, if a person’s FBS in exam 3 was > 126, the diabetes duration was equal to 1/2 the time of exam 2 until the occurrence of the outcome or the end of the cohort. Second: Time interval until the occurrence of the outcome: To calculate the duration of diabetes diagnosis until the occurrence of outcomes, the occurrence of outcomes was subtracted from the time of diabetes diagnosis. Third: The time from the start of taking the medications to the time of changing or stopping the medications was defined as the medication time (Cumulative exposure). For example, if a person was taking metformin in the current exam (For example, exam 2) but was taking SUs in the next exam, the metformin duration was equal to the total duration of exam 2 + 1/2 the duration of exam 3, with the assumption that the person will be half of the next exam has also taken metformin.

The cumulative exposure calculation method and its assumptions were defined the same in all three cohorts and for all medications (metformin, SUs, combination of both, statin, anti-hypertensive, and aspirin).

All time-dependent variables were extracted for all exams, and their mean from the time of diagnosis of diabetes to the occurrence of the outcome was adjusted. The mean of age, BMI, lipid profile (HDL, LDL, triglycerides, and cholesterol), FBS, waist circumference, physical activity, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and creatinine from the time of diabetes diagnosis until the occurrence of any outcome or the last follow-up period were calculated. Cumulative exposure to statin, anti-hypertensive, and aspirin was calculated.

Exposure and outcomes

In this study, the duration of OAD, including metformin alone, SUs alone, and SU’s use of both combinations, was defined as exposure in patients during the cohorts. The duration of each medication was calculated separately. To estimate the interaction between metformin and SUs was calculated separately. ACM and CVD Mortality and incident cardiovascular events were defined as study outcomes. Incident cardiovascular events included coronary heart disease, CVD sudden death, cerebrovascular disease, and stroke.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Stata version 17 statistical software. The relationship between exposure variables and outcome considering confounders was drawn with the DAGitty tool (https://www.dagitty.net/dags.html). Descriptive statistics (% and number) were used to report qualitative variables. Quantitative variables (medication time (years), FBS, age, BMI, waist, lipid profile, blood pressure, disease duration, and creatinine level) were reported with mean, quartiles, and standard deviation.

First, Cox proportional hazards (CPH) model analysis with multivariable fractional polynomial (MFP) evaluated the assumption of linearity with the relationship between exposure and outcomes. Due to the non-establishment of a linear relationship between exposure and outcomes, the multivariable modeling with Cubic regression splines (MVRS) package was used in the CPH analysis. Then, according to the method of P Royston et al.31 with the fracpplot command, The trend of changes in the hazard of occurrence of each outcome was plotted against the duration of medications.

To estimate the net effect of metformin and SUs, the individual effects of each drug and the combined effect of both were calculated using the Lincom command. The effect size of exposure on each outcome was evaluated in three models. Model 1 was defined as a crude model (duration of metformin, SUs, and A combination of both). The second model included the crude model adjusted for the mean age and the mean FBS from the time of DM diagnosis to the occurrence of each outcome. The third model included model 2, adjusted for the variables of sex, smoke, waist, marital status, HDL, LDL, TG, education level, physical activity, cumulative exposure to other treatments (aspirin, statin, and anti-hypertensive), creatinine, and blood pressure. Adjusted hazard ratio (HR) with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was used to report the effect of metformin and SUs medication time on outcomes. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered a statistical significance level.

Results

Demographic, laboratory, clinical characteristics, and mean duration of medication

Based on the pooled estimation of data from three cohorts (4271 newly diagnosed DM patients), the mean age at the time of diabetes diagnosis and during the study was 49.6 ± 1.2 and 59.4 ± 0.66 years, respectively. 53.3% of patients were women. The mean of FBS at the time of diabetes diagnosis and during the survey was 158.22 ± 1.69 (range of 126.5 to 488) and 149.49 ± 2.21 (range of 89 to 477) mg/dl, respectively. The metformin, SUs, and combination medication time were 6.27 ± 0.4, 5.88 ± 0.6, and 4.92 ± 0.8, respectively. The aspirin, anti-hypertensive, and statin medication times were 10.9 ± 2.5, 11.33 ± 2.1, and 10.8 ± 2.8, respectively. Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients were reported by type of medication used (Additional file 1-Table 1).

The mean physical activity was 77.2 ± 0.33 m/w. The mean of the majority of laboratory indicators decreased during the period of drug use compared to the time of diagnosis. The median follow-up of the patients was 20.33 ± 0.45 years. Demographics, laboratory, clinical characteristics, and duration of medication use are reported in Table 1.

Outcomes

Incident cardiovascular events

During the follow-up period, 767 CVD events occurred. The mean time from diagnosis of DM to incident cardiovascular events was 19.8 ± 0.13 years. In models 1 and 2, metformin and its combination with SUs significantly reduced the hazard of incident cardiovascular events in newly diagnosed DM. While using SUs alone was associated with a decrease in the hazard of CVD events, this difference was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). In model 3, the duration of using metformin alone, SUs alone, and combining both significantly reduced the hazard of CVD events in newly diagnosed DM. Also, the estimated effect of exposure to the outcome in the Fine-Gray model (competing risk) and the CPH model were almost similar. (Table 2)

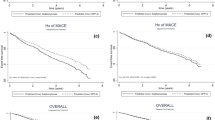

The MVRS analysis adjusted for all variables showed that although the duration of use of all three treatment groups was significantly related to the reduction in the hazard of CVD events, but this relationship was not linear, and its reduction effect was different depending on the duration of use of the drugs. The effect of reducing the duration of metformin use remained Plato after 10.11 years (Fig. 2-Fracplot A). SUs use reduced CVD events for approximately five years, and the effect remained Plato for up to 6 years. Its effect increased after almost six years for the hazard of hard CVD events (Fig. 2-Fracplot B). The reducing effect of the combination of metformin and SUs on reducing the hazard of CVD events with different coefficients remained for up to 11 years. Then, its effect on hard CVD events in newly diagnosed DM remained at Plato (Fig. 2-Fracplot C).

To estimate the net effect of metformin and SUs, the effect size of their individual use was combined with the effect of their simultaneous combination with the Lincom package. Assuming a linear relationship between exposure and outcome, adjusted for all variables, the use of metformin with SUs reduced the hazard of hard CVD events by an average of 10% during follow-up (HRAdj 0.90, 95% CI 0.85, 0.96, P 0.001). Duration of use of SUs with metformin reduced the hazard of hard CVD events by an average of 6% during the follow-up period (HRAdj 0.94, 95% CI 0.90, 0.99, P 0.009).

CVD mortality

The total CVD mortality in the population was 439, including almost half of the ACM. The mean time from diagnosis of DM to CVD mortality was 19.01 ± 0.15 years. The mean duration of use of all three treatment regimens was significantly associated with reducing CVD mortality hazard in the crude model. In model 2, the metformin with and without SUs significantly reduced the hazard of CVD mortality in newly diagnosed DM (p < 0.005). In model 3, metformin with and without SUs and SUs with and without metformin significantly reduced the hazard of developing CVD mortality in newly diagnosed DM. The estimated effect of exposure to the outcome in the Fine-Gray (competing risk) and the CPH model was almost similar (Table 2).

The results of MVRS based on CPH analysis adjusted for all variables showed that although the duration of use of all three drug combinations was significantly related to the reduction of the hazard of CVD mortality, but this relationship was not linear, and its reducing effect was different in the time intervals of drugs use. The reducing effect of the duration of metformin use remained Plato after 4.89 years (Fig. 3-Fracplot A). SUs consumption decreased CVD mortality until almost 5 years, and its effect remained Plato until 8 years which this effect became ineffective or reversed after 8 years (Fig. 3-Fracplot B). The reducing effect of the combination of metformin with SUs on reducing the hazard of ACM with different coefficients remained for 5 years. Then, its effect on CVD mortality in newly diagnosed DM patients remained Plato (Fig. 3-Fracplot C).

A pooled estimate of the effect of metformin use alone with its concomitant use with SUs, assuming a linear relationship between exposure and outcome, adjusted for all variables, reduced the hazard of CVD mortality by an average of 12% during the follow-up (HRAdj 0.88, 95% CI 0.84, 0.93, P 0.001). SUs combined with metformin reduced the hazard of CVD mortality by an average of 8% during the follow-up period (HRAdj 0.92, 95% CI 0.87, 0.98, P 0.006).

All-cause mortality

During the follow-up period, 913 ACM had occurred. The mean time from diagnosis of DM to ACM was 19.8 ± 0.13 years. In the crude model, all three treatment regimens significantly reduced ACM. In model 2, the use of metformin with and without SUs was significantly associated with a reduction in the hazard of ACM. While the use of SU alone was associated with decrease in the hazard of ACM, but this difference was not statistically significant (p 0.066). In model 3, the duration of using metformin alone, SUs alone, and their combination significantly reduced the hazard of ACM (Table 3).

MVRS results based on CPH analysis adjusted for all variables showed that the duration of metformin alone, SUs alone, and their combination significantly reduced ACM hazard. Still, this relationship was not linear, and its reducing effect differed in different periods. The effect of metformin remained with Plato after 8 years (Fig. 4-Fracplot A). The effect of SU consumption on ACM was 0.4 years after taking the and after 5 years of using its effect. This effect became ineffective or reversed after 5 years (Fig. 4-Fracplot B). The combination of metformin and SUs to reduce the hazard of ACM continued with different coefficients until 10.085. The effect of the combination use of metformin and SUs on ACM remained Plato after 10.085 years (Fig. 4- Fracplot C).

Assuming a linear association between exposure and outcome, adjusted for all variables, metformin use pooled with their combined effect reduced the hazard of ACM by 11% during the follow-up period (HRAdj 0.89, 95% CI 0.85, 0.94, P 0.001 SUs pooled with their combined effect reduced the hazard of ACM by an average of 7% (HRAdj 0.93, 95% CI 0.89, 0.98, P 0.001).

In addition, multivariate analysis showed that increasing mean of age, FBS, LDL, waist circumference, creatinine, and smoking were significantly related to increased hazard of incident CV event, CV Mortality, and ACM. At the same time, physical activity, use of Statins, anti-hypertensive medication, and aspirin had a protective role (data not shown).

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the effect of medication time metformin and SUs on the hazard of incident hard CVD events, ACM, and CVD mortality in 4108 newly diagnosed DM patients using data from 3 Prospective cohorts for the first time. Evaluating the effect of the duration of metformin alone, SUs alone, and the simultaneous combination of both on these three outcomes in a large sample of newly diagnosed DM patients which the time of disease diagnosis, initiation of treatment, the duration of the use of OAD compounds and the time when the outcomes occurred from the onset of the disease was known in them distinguishes the results of this study from the results of other studies.

Our study showed that, adjusted for other variables, all three medication regimens significantly reduced the hazard of incident CVD events, ACM, and CVD mortality. Metformin with and without SUs reduced the hazard of all three outcomes more than SUs alone. Cumulative estimation of the effect of metformin and SUs showed only with the combination of both, assuming a linear relationship between the Medication time and outcomes. Metformin and SUs reduced the hazard of ACM rate by approximately 11% and 7% on average, respectively. Taking metformin combined with SUs reduced the hazard of CVD mortality and hard CVD event rates on average by approximately 12% and 10% during follow-up. Using SUs combined with metformin reduced the hazard of CVD mortality and hard CVD events rates on average by approximately 8% and 6%, respectively, during follow-up.

The effect of metformin on reducing cardiovascular events and ACM continued until the first ten years of treatment and then remained at the plateau. In contrast, the effect of metformin on reducing CVD mortality continued until the first five years of treatment and then remained Plato. The effect of combining metformin with SUs had almost the same results as metformin alone. The effect of SUs on reducing cardiovascular events and ACM continued until the first 5 years of treatment and then became ineffective or reversed. The effect of SUs on reducing CVD mortality continued until the first eight years of treatment and then became ineffective or reversed. The results of this study showed that the combined effect of metformin + SUs was superior to the individual effect of metformin or sulfonylurea alone.

Several studies have shown that using metformin alone or combined with SUs was significantly associated with the reduction risk of hard CVD events, ACM, and CVD mortality. Also, SUs alone have been associated with decreased risk of hard CVD events, ACM, and CVD mortality, although their effect is less than metformin alone32,33,34,35. However, these results still need to be debated and are not conclusive. In line with the results of our study, Y Han et al.36showed that metformin was significantly associated with a reduction in CV events, ACM, and CVD mortality in coronary artery disease (CAD) patients. They also reported that metformin was more effective than SUs in reducing the incidence of CV events. In another meta-analysis, Li et al.,37showed that metformin significantly reduced the risk of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, coronary artery disease, and heart failure in patients with CVD. At the same time, there was no significant relationship with reducing the incidence of myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, or stroke. Monami et al.38 showed that metformin reduces the risk of ACM and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) by nearly 20% and 40%, respectively, compared to other OADs, which was consistent with the results of our study. The difference in the reduction of MACEs in the two studies can be justified by the difference in the follow-up period of the patients and the characteristics of the studied populations. This meta-analysis included RCT studies, usually with a short follow-up period with special conditions. They examined the efficacy, while in our study, we evaluated the effectiveness and effect of drugs at the community level in newly diagnosed DM patients.

An umbrella review showed that metformin use reduced the risk of CVD events, ACM, and CVD mortality by 17%, 20%, and 23%, respectively39. Zhou et al.,40 showed that the reduction in the risk of AF, stroke, CVD mortality and ACM was significantly higher in metformin users compared to SUs. Azoulay et al.,34 reported that metformin combined with SUs can reduce the risk of ACM and CVD mortality more than their alone effect. Thein et al.41 showed that adding metformin to other OADs may synergistically reduce ACM, CVD Mortality, and CVD events, reducing the risk of outcomes more than their alone effect. In a prospective cohort study, Comoglio et al.,42 showed that metformin reduced the risk of ACM mortality and MACE more than other AODs, especially SUs. Zhang et al.,22 showed that metformin treatment significantly reduced the risk of cardiovascular outcomes (both death and incidence) in DM patients. Bain et al.,43 showed that SUs treatment was associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease-related events compared with other glucose-lowering drugs. The results of this study and literature review show that treatment with SUs in the first years of the disease can be significantly associated with a reduction in CVD events and ACM. The effect of treatment with SUs alone on long-term cardiovascular outcomes may be reversed.

Wong et al.44 showed that using metformin compared to SGLT2 inhibitors significantly reduced the risk of ACM and CVD mortality in DM patients with CVD. Also, in addition to reducing the risk of ACM, metformin use was associated with increased life expectancy in DM patients without CVD. In a cohort study, Chun et al.45 (45) (49), evaluating 1309 diabetic patients, showed that metformin use significantly reduced the risk of one-year ACM in DM patients who were hospitalized due to acute heart failure (HF).

Contrary to our results, Gnesin et al.,46 by reviewing 18 RCTs, did not report a significant relationship between metformin monotherapy compared to no intervention or other glucose-lowering drugs with reducing the risk of ACM and CVD events in diabetic patients. Griffin et al.,47 did not report a clear drug-meaning relationship between metformin monotherapy as the first-line drug and reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease in diabetic patients. Lamanna et al.,48 did not report a clear association between metformin use and reduced risk of CVD outcomes, especially in combination with SUS. However, in all reported meta-analyses, the heterogeneity between studies was significant.

Our study showed that using SUs in the first years significantly reduced the hazard of hard CVD events and ACM and CVD mortality. The effect of SUs on reducing cardiovascular events and ACM continued to the first 5 years of treatment. This effect was to reduce CVD mortality, which continued for the first eight years and then became ineffective or reversed. Meanwhile, the process of reducing the hazard of all three continued for almost 11 years with different slopes using the combination of metformin with SUs, and after that, it remained Plato. This shows that to achieve better efficiency and prevent the increased hazard of side effects, it is better to use metformin continuously at the same time as SUs, and the patient’s diet should not be directed towards SUs alone.

This change of effect in monotherapy with SUs can be explained by the chronicity of the disease and failure of beta cells. The main mechanism of the reverse effect or ineffective of SUS in long-term use and chronic diabetes is beta-cell failure49. Remedi et al.49, demonstrated that chronic treatment of SUS with hyper-excitability of beta cells leads to decreased insulin secretion capacity and thus to a decrease in DM control in vivo. The secretory function of insulin in people with type 2 diabetes gradually decreases50,51. Several studies have shown that, in patients with diabetes, SUs can significantly control blood sugar in the early stages of the disease. Still, evidence shows that SU treatments often fail to control blood sugar in the long term, but in the long term (months to years), they often fail52,53,54. Studies have shown that long-term SUs treatment leads to impaired glucose tolerance and glucose-induced insulin secretion (GSIS)55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62.

Li et al.,63 showed that long-term use of SUs was associated with an increased risk of CVD events among women with DM, which indicates that long-term use and, in parallel, increasing the dose of SUs in the long term can be associated with an increased risk of hard CVD events rate. Li et al.,64 showed that the long-term use of SUs alone compared with metformin alone for the initial diabetes treatment was associated with an increased risk of ACM and CVD events. Roumie et al.,64 showed that although treatment with each round of OADs SUs and metformin is generally associated with a reduction in ACM and CVD mortality. However, the reduction in risk of ischemic stroke, CVD, and ACM mortality in diabetic patients who received metformin alone was significantly greater than that of SUs alone.

There are several potential mechanisms to explain these results. First, this change in the effect on the risk of CVD events, ACM, and CVD mortality can be explained by increasing the drug dose with the progression of the disease and the duration of the chronic disease. Several studies have reported that increasing doses of SUs are associated with an increased risk of CVD events, ACM, and CVD mortality. At the same time, such a relationship was not observed for other OADs63,65. Others have suggested that the presence of SUs receptors on vascular cells and cardiomyocytes leads to impaired ischemic preconditioning that increases CVD mortality and CVD events risk of SUs66,67,68. However, some others showed that the probability of this assumption is weak. Another hypothesized mechanism of possible disorder in the expansion of coronary arteries and increase in myocardial damage is the result of the possible effect of SUs on ATP-dependent potassium channels on the cells of the heart and coronary arteries66. In addition, several other studies have shown that by inhibiting ATP-dependent potassium channels, SUs may increase the risk of CVD events and sudden death by increasing cardiac arrhythmias and prolonging QT intervals69,70,71.

Patients who do not receive antidiabetic treatment may not receive appropriate medical care, which significantly increases the incidence of death and CVD outcomes in these patients. These results indicate the protective role of blood sugar control, and patients should be aware of the complications of DM and its lack of treatment and control. Therefore, in addition to therapeutic interventions, educational interventions such as holding educational workshops and patient care can also increase patient awareness and, as a result, increase the desire to control the disease and reduce its associated complications.

Our study had strengths and weaknesses that should be noted. Firstly, due to the design of the study, we did not have access to several key variables, such as the dose of the drug consumed in different time intervals, so we could not evaluate the effect of drug dose on the outcomes, which may have a negative effect on the results of the study. The lack of access and adjustment for HbA1c was our most important limitation. Due to the high missing in HbA1c, we could not estimate HbA1c, and the definition of DM was based on FBS. However, given that the aim was to evaluate the effect of treatment duration on the outcome and FBS was also measured and recorded during the follow-up period in all phases, its negative effect on the results may be very limited and clinically negligible. Although we analyzed the results of the studies separately based on the populations covered by the groups and the results were the same in all three cohorts, despite the differences in the quality of drugs in different countries, the income level, and also the different lifestyles in the countries may affect the results of the study. In cohort studies, medication adherence is recorded by patient self-report, although this trend is assumed to be the same in the populations covered by the different cohorts.

The most important strength of this study was evaluating the effect of metformin and SUs’ medication time on CVD events, ACM, and CVD mortality in a large sample size with a long follow-up period in conditions adjusted for confounders in newly diagnosed DM patients.

Conclusion

Among newly diagnosed DM patients, metformin, with and without SUs, was associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular events, ACM, and CVD mortality for up to about one decade. Also, Metformin with and without SUs was associated with a reduced hazard of cardiovascular events, ACM, and CVD mortality for up to 10 years, and then it remained at Plato. The combined effect of metformin + sulfonylurea was superior to the single effect of metformin or sulfonylurea alone. The effect of metformin was greater than that of SUs alone, and their combination effect may be Synergistic. The relationship between the use of SUs alone and cardiovascular events, ACM, and CVD mortality was different by type 2 diabetes duration and the duration of SU use. Monotherapy with SU in the first years significantly reduces the hazard of CVD events, ACM, and CVD mortality, while, in the case of combination with metformin, its reducing effect on all three outcomes remains Plato in the long term. The effect of SUs on reducing cardiovascular events and ACM continued to the first five years of treatment. This effect was to reduce CVD mortality, which continued for the first eight years and then became ineffective or reversed. The combination therapy of Metformin and SUs can still be used with good safety, especially in the first years of diabetes diagnosis.

Data availability

The datasets generated or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- OAD:

-

Oral anti-diabetic

- SUs:

-

Sulfonylurea

- TLGS:

-

Tehran lipid and glucose study

- MESA:

-

Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis

- ARIC:

-

Atherosclerosis risk in communities

- CPH:

-

Cox proportional hazards

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- ACM:

-

All-cause mortality

- CV-mortality:

-

Cardiovascular mortality

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- HbA1c:

-

Hemoglobin A1C

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- FBS:

-

Fasting blood glucose

- MFP:

-

Multivariable fractional polynomial

References

Afsar, B. The impact of different anthropometric measures on sustained normotension, white coat hypertension, masked hypertension, and sustained hypertension in patients with type 2 diabetes. Endocrinol. Metab.. 28 (3), 199–206 (2013).

Association, A. D. 1. Improving care and promoting health in populations: standards of medical care in diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care. 43 (Suppl 1), S7–S13 (2020).

Chatterjee, S., Khunti, K. & Davies, M. J. Type 2 diabetes. Lancet 389 (10085), 2239–2251 (2017).

Ahmad, E., Lim, S., Lamptey, R., Webb, D. R. & Davies, M. J. Type 2 diabetes. Lancet 400 (10365), 1803–1820 (2022).

Abdul Basith Khan, M. et al. Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes—global burden of disease and forecasted trends. J. Epidemiol. Glob.Health. 10 (1), 107–111 (2020).

Luo, J., Hodge, A., Hendryx, M. & Byles, J. E. Age of obesity onset, cumulative obesity exposure over early adulthood and risk of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 63, 519–527 (2020).

Yang, Y. S., Han, B-D., Han, K., Jung, J-H. & Son, J. W. Obesity fact sheet in Korea, 2021: trends in obesity prevalence and obesity-related comorbidity incidence stratified by age from 2009 to 2019. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr.. 31 (2), 169 (2022).

Saeedi, P. et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 157, 107843 (2019).

Mathers, C. D. & Loncar, D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 3 (11), e442 (2006).

Mann, D. M., Ponieman, D., Leventhal, H. & Halm, E. A. Misconceptions about diabetes and its management among low-income minorities with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 32 (4), 591–593 (2009).

Cichosz, S. L., Johansen, M. D. & Hejlesen, O. Toward big data analytics: review of predictive models in management of diabetes and its complications. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 10 (1), 27–34 (2016).

Lamri, L., Gripiotis, E. & Ferrario, A. Diabetes in Algeria and challenges for health policy: a literature review of prevalence, cost, management and outcomes of diabetes and its complications. Glob. Health. 10 (1), 1–14 (2014).

Lee, C., Joseph, L., Colosimo, A. & Dasgupta, K. Mortality in diabetes compared with previous cardiovascular disease: a gender-specific meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab. 38 (5), 420–427 (2012).

Xu, X-H. et al. Diabetic retinopathy predicts cardiovascular mortality in diabetes: a meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 20, 1–8 (2020).

Chen, L. et al. A systematic review of trends in all-cause mortality among people with diabetes. Diabetologia 63, 1718–1735 (2020).

Fung, C. S. C., Wan, E. Y. F., Wong, C. K. H., Jiao, F. & Chan, A. K. C. Effect of metformin monotherapy on cardiovascular diseases and mortality: a retrospective cohort study on Chinese type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 14 (1), 137 (2015).

Setter, S. M., Iltz, J. L., Thams, J. & Campbell, R. K. Metformin hydrochloride in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a clinical review with a focus on dual therapy. Clin. Ther. 25 (12), 2991–3026 (2003).

Wong, M., Sin, C. & Lee, J. The reference framework for diabetes care in primary care settings. Hong Kong Med. J. 18 (3), 238–246 (2012).

Association, A. D. American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes–2017. Diabetes care. 40 (Suppl. 1), S1 (2017).

Qaseem, A., Barry, M. J., Humphrey, L. L., Forciea, M. A. & Physicians, C. G. C. A. C. Oral pharmacologic treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians. Ann. Intern. Med. 166 (4), 279–290 (2017).

Sherifali, D., Nerenberg, K., Pullenayegum, E., Cheng, J. E. & Gerstein, H. C. The effect of oral antidiabetic agents on A1C levels: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 33 (8), 1859–1864 (2010).

Zhang, K., Yang, W., Dai, H. & Deng, Z. Cardiovascular risk following metformin treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: results from meta-analysis. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 160, 108001 (2020).

Bahardoust, M. et al. Effect of metformin (vs. placebo or sulfonylurea) on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality and incident cardiovascular events in patients with diabetes: an umbrella review of systematic reviews with meta-analysis. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. (2023).

Campbell, J. M., Bellman, S. M., Stephenson, M. D. & Lisy, K. Metformin reduces all-cause mortality and diseases of ageing independent of its effect on diabetes control: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 40, 31–44 (2017).

Grapow, M. T., von Wattenwyl, R., Guller, U., Beyersdorf, F. & Zerkowski, H-R. Randomized controlled trials do not reflect reality: real-world analyses are critical for treatment guidelines! J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 132 (1), 5–7 (2006).

Tunis, S. R., Stryer, D. B. & Clancy, C. M. Practical clinical trials: increasing the value of clinical research for decision making in clinical and health policy. JAMA 290 (12), 1624–1632 (2003).

Schneeweiss, S. & Avorn, J. A review of uses of health care utilization databases for epidemiologic research on therapeutics. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 58 (4), 323–337 (2005).

Tricco, A. C. & Rawson, N. S. Manitoba and Saskatchewan administrative health care utilization databases are used differently to answer epidemiologic research questions. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 61 (2), 192–197.e112 (2008).

Fralick, M., Kesselheim, A. S., Avorn, J. & Schneeweiss, S. Use of health care databases to support supplemental indications of approved medications. JAMA Intern. Med. 178 (1), 55–63 (2018).

Larsen, M. D., Cars, T. & Hallas, J. A minireview of the use of hospital-based databases in observational inpatient studies of drugs. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 112 (1), 13–18 (2013).

Royston, P. & Sauerbrei, W. Multivariable modeling with cubic regression splines: a principled approach. Stata J. 7 (1), 45–70 (2007).

Roumie, C. L. et al. Association of treatment with metformin vs sulfonylurea with major adverse cardiovascular events among patients with diabetes and reduced kidney function. JAMA 322 (12), 1167–1177 (2019).

Rao, A. D., Kuhadiya, N., Reynolds, K. & Fonseca, V. A. Is the combination of sulfonylureas and metformin associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease or all-cause mortality? A meta-analysis of observational studies. Diabetes Care. 31 (8), 1672–1678 (2008).

Azoulay, L., Schneider-Lindner, V., Dell’Aniello, S., Schiffrin, A. & Suissa, S. Combination therapy with sulfonylureas and metformin and the prevention of death in type 2 diabetes: a nested case‐control study. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 19 (4), 335–342 (2010).

Herrera Comoglio, R. & Vidal Guitart, X. Cardiovascular events and mortality among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients newly prescribed first-line blood glucose-lowering drugs monotherapies: a population-based cohort study in the Catalan electronic medical record database, SIDIAP, 2010–2015. Prim. Care Diabetes. 15 (2), 323–331 (2021).

Han, Y. et al. Effect of metformin on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with coronary artery diseases: a systematic review and an updated meta-analysis. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 18, 1–16 (2019).

Li, T. et al. Association of metformin with the mortality and incidence of cardiovascular events in patients with pre-existing cardiovascular diseases. Drugs 82 (3), 311–322 (2022).

Monami, M. et al. Effect of metformin on all-cause mortality and major adverse cardiovascular events: an updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 31 (3), 699–704 (2021).

Bahardoust, M. et al. Effect of metformin (vs. placebo or sulfonylurea) on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality and incident cardiovascular events in patients with diabetes: an umbrella review of systematic reviews with meta-analysis. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2023, 1–12 .

Zhou, J. et al. Metformin versus sulphonylureas for new onset atrial fibrillation and stroke in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a population-based study. Acta Diabetol. 59 (5), 697–709 (2022).

Thein, D. et al. Add-on therapy in metformin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes at moderate cardiovascular risk: a nationwide study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 19, 1–11 (2020).

Comoglio, R. H. & Guitart, X. V. Cardiovascular events and mortality among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients newly prescribed first-line blood glucose-lowering drugs monotherapies: a population-based cohort study in the Catalan electronic medical record database, SIDIAP, 2010–2015. Prim. Care Diabetes. 15 (2), 323–331 (2021).

Bain, S. et al. Cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality associated with sulphonylureas compared with other antihyperglycaemic drugs: AB ayesian meta‐analysis of survival data. Diabetes Obes. Metab.. 19 (3), 329–335 (2017).

Wong, H. J. et al. Evaluation of the Lifetime benefits of Metformin and SGLT2 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes Mellitus patients with Cardiovascular Disease: a systematic review and two-stage meta-analysis. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs 2024, 1–13 .

Chun, K-H. et al. Impact of metformin on the all-cause mortality of diabetic patients hospitalized with acute heart failure: an observational study using acute heart failure registry data. (2023).

Gnesin, F., Thuesen, A. C. B., Kähler, L. K. A., Madsbad, S. & Hemmingsen, B. Metformin monotherapy for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020(6).

Griffin, S. J., Leaver, J. K. & Irving, G. J. Impact of metformin on cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of randomised trials among people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 60, 1620–1629 (2017).

Lamanna, C., Monami, M., Marchionni, N. & Mannucci, E. Effect of metformin on cardiovascular events and mortality: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Diabetes Obes. Metab.. 13 (3), 221–228 (2011).

Remedi, M. S. & Nichols, C. G. Chronic antidiabetic sulfonylureas in vivo: reversible effects on mouse pancreatic β-cells. PLoS Med. 5 (10), e206 (2008).

Wright, A. et al. Sulfonylurea inadequacy: efficacy of addition of insulin over 6 years in patients with type 2 diabetes in the UK prospective diabetes study (UKPDS 57). Diabetes Care. 25 (2), 330–336 (2002).

Matthews, D. R. & Wallace, T. M. Sulphonylureas and the rise and fall of beta-cell function. Br. J. Diabetes Vasc. Dis.. 5 (4), 192–196 (2005).

Davis, T. M. et al. Islet autoantibodies in clinically diagnosed type 2 diabetes: prevalence and relationship with metabolic control (UKPDS 70). Diabetologia 48, 695–702 (2005).

Wysham, C. & Shubrook, J. Beta-cell failure in type 2 diabetes: mechanisms, markers, and clinical implications. Postgrad. Med. 132 (8), 676–686 (2020).

Alvarsson, M. et al. Effects of insulin versus sulphonylurea on beta-cell secretion in recently diagnosed type 2 diabetes patients: a 6-year follow-up study. Rev. Diabet. Studies: RDS. 7 (3), 225 (2010).

Nichols, C. G., Koster, J. & Remedi, M. β-cell hyperexcitability: from hyperinsulinism to diabetes. Diabetes Obes. Metab.. 9, 81–88 (2007).

Ohyama, S. et al. -i: a small-molecule glucokinase activator lowers blood glucose in the sulfonylurea-desensitized rat. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 640 (1–3), 250–256 (2010).

van Raalte, D. H. & Diamant, M. Glucolipotoxicity and beta cells in type 2 diabetes mellitus: target for durable therapy? Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 93, S37–S46 (2011).

Mukai, E., Fujimoto, S. & Inagaki, N. Role of reactive oxygen species in glucose metabolism disorder in diabetic pancreatic β-cells. Biomolecules 12 (9), 1228 (2022).

Karbalaei, N., Noorafshan, A. & Hoshmandi, E. Impaired glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and reduced β‐cell mass in pancreatic islets of hyperthyroid rats. Exp. Physiol. 101 (8), 1114–1127 (2016).

Lundquist, I., Mohammed Al-Amily, I., Meidute Abaraviciene, S. & Salehi, A. Metformin ameliorates dysfunctional traits of glibenclamide-and glucose-induced insulin secretion by suppression of imposed overactivity of the islet nitric oxide synthase-NO system. PLoS One. 11 (11), e0165668 (2016).

Takahashi, A. et al. Sulfonylurea and Glinide reduce insulin content, functional expression of KATP channels, and accelerate apoptotic β-cell death in the chronic phase. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 77 (3), 343–350 (2007).

Nybäck-Nakell, Å., Bergström, J., Adamson, U., Lins, P. & Landstedt-Hallin, L. Decreasing postprandial C-peptide levels over time are not associated with long-term use of sulphonylurea: an observational study. Diabetes Metab. 36 (5), 375–380 (2010).

Li, Y., Hu, Y., Ley, S. H., Rajpathak, S. & Hu, F. B. Sulfonylurea use and incident cardiovascular disease among patients with type 2 diabetes: prospective cohort study among women. Diabetes Care. 37 (11), 3106–3113 (2014).

Roumie, C. L. et al. Comparative effectiveness of sulfonylurea and metformin monotherapy on cardiovascular events in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med. 157 (9), 601–610 (2012).

Abdelmoneim, A. S., Eurich, D. T., Senthilselvan, A., Qiu, W. & Simpson, S. H. Dose-response relationship between sulfonylureas and major adverse cardiovascular events in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 25 (10), 1186–1195 (2016).

Sola, D. et al. State of the art paper Sulfonylureas and their use in clinical practice. Arch. Med. Sci. 11 (4), 840–848 (2015).

Gross, G. J. & Auchampach, J. A. Blockade of ATP-sensitive potassium channels prevents myocardial preconditioning in dogs. Circul. Res. 70 (2), 223–233 (1992).

Maslov, L. N. et al. KATP channels are regulators of programmed cell death and targets for the creation of novel drugs against ischemia/reperfusion cardiac injury. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 37 (6), 1020–1049 (2023).

Najeed, S. A., Khan, I. A., Molnar, J. & Somberg, J. C. Differential effect of glyburide (glibenclamide) and metformin on QT dispersion: a potential adenosine triphosphate sensitive K + channel effect. Am. J. Cardiol. 90 (10), 1103–1106 (2002).

Wang, H. et al. Metformin shortens prolonged QT interval in diabetic mice by inhibiting L-type calcium current: a possible therapeutic approach. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 614 (2020).

Nantsupawat, T., Wongcharoen, W., Chattipakorn, S. C. & Chattipakorn, N. Effects of metformin on atrial and ventricular arrhythmias: evidence from cell to patient. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 19, 1–14 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The present study is a part of PhD thesis written by Mansour Bahardoust under the supervision of prof. Ali Delpisheh; Prof. Davood Khalili, Prof. Farzad Hadaegh and Prof. Yadollah Mehrabi.

Funding

The present study was financially supported by Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.B., F.H., D.K., F.A. and A.D. designed the study. M.B., D.K. and Y.M. finished statistical analysis. M.B., F.H., and A.D. wrote the first draft. D.K. and F.H. reviewed and checked the manuscript. A.D., D.K., M.B. and F.H. modified the English. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by Shahid Beheshti, University of Medical Sciences’s ethics committee (ethical code: IR. REC.PHNS.SBMU.1402.008), and The data was requested from NHLBI BiologicSpecimen and Data Repository Information CoordinatinCenter (BioLINCC), with the RRBB providing it.All methods were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and current ethics guidelines. Shahid Beheshti, University of Medical Sciences ethics committee, waived the need for informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bahardoust, M., Hadaegh, F., Mehrabi, Y. et al. Medication time of metformin and sulfonylureas and incidence of cardiovascular diseases and mortality in type 2 diabetes: a pooled cohort analysis. Sci Rep 15, 8401 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89721-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89721-7