Abstract

This study explores the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic-induced shift to remote instruction on parental mental health, using data from the American Enterprise Institute’s Return-to-Learn tracker and the U.S. Census Pulse Survey. We exploit within-state variation in the timing of school closures from August 2020 to June 2021, controlling flexibly for demographic and state-level factors. We find that an increase in the proportion of remote instruction districts correlates with an escalation in parental mental health issues, including heightened anxiety, worry, depression, and a loss of interest in activities. These adverse effects are significantly lessened among parents who choose homeschooling. A one percentage point increase in the share of remote instruction in the state is associated with a 2.2 percentage point rise in homeschooling probability. Our paper contributes to understanding the wider impact of pandemic-induced educational changes, highlighting substantial mental health implications for parents. Taking stock of lessons learned over the Covid-19 pandemic, these findings are pivotal for shaping informed educational policies that consider the well-being of the whole family during crises.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

At the start of COVID-19, nearly all of the student population in the United States transitioned to remote instruction for a period of time. A large body of empirical literature, however, suggests that pandemic-induced remote instruction produced worse outcomes for students, especially during early childhood1,2,3,4. These studies provide lower bounds on the adverse effects on student learning due to a sudden, government-mandated shift from in-person learning to fully remote instruction, as full effects will only be visible as more data becomes available. Many parents transitioned their children towards alternative learning arrangements after it became clear that some school districts were going to continue with remote instruction5.

Homeschooling became an increasingly popular option for many parents. The percent of U.S. households with school-aged children who were homeschooled doubled from the end of the 2019–2020 school year to the start of the 2020–2021 school year—from about 5.4% to 11.1%6. The increasing popularity of homeschooling even prompted researchers at the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy to publish a how-to guide entitled “Suddenly Homeschooling? A Parent’s Survival Guide to Schooling During COVID-19”7. However, little empirical evidence exists on how this transition away from in-person instruction may have impacted parental mental health given the new responsibilities in monitoring and managing their children’s education at home, particularly given the declining availability of childcare during these years8.

This paper quantifies how public school closures of in-person learning affected the incidence of homeschooling and the resulting effect on parental mental health. Even if the quality of remote and in-person instruction were the same, the requirement of parental supervision in the household may have created significant disruptions, especially given the decline in the availability of child care due to state quarantines9 and the increase in regulation requiring schooling to be delivered remotely8. While there is some anecdotal and scientific evidence about the unintended effects of these quarantine policies10,11,12 and their effects on parental mental health13,14, there is not yet evidence that has linked school closures and mental health with the role of homeschooling as a substitute learning arrangement for those with children.

Drawing on the Return-to-Learn (R2L) tracker from the American Enterprise Institute, coupled with micro-data from the Census Pulse survey, we estimate the effect of remote instruction on parental mental health between August 2020 to June 2021. Our identification strategy exploits within-state variation in the timing and intensity that school districts transitioned to remote instruction, controlling for a wide array of demographic and state-level factors. We find that a one percentage point (pp) increase in the share of remote districts in a state is associated with a 8.6 pp increase in the probability that a parent was anxious. Estimates are similar for worry (5.9 pp), depression (3.6 pp), and losing general interest in activities (3.4 pp). We conducted several robustness exercises. First, our estimates are invariant to a wide array of controls, such as the inclusion of parental work loss, which addresses the concern that mental health declined due to job loss, and to lagged COVID-19 case and death rates, which addresses the concern that periods of greater pandemic severity drove the declines in mental health. Third, we obtain similar results when we instrument for remote instruction using pre-pandemic union power, suggesting that our results are not driven by omitted time-varying shocks15,16,17. Fourth, we find similar results when we interact our treatment variable with a pre-closure variable in February 2020, which helps normalize for any pre-pandemic trends.

The adverse effects of remote instruction on parental mental health were not uniform; we document significant heterogeneity. Effects are larger for Whites and college-educated respondents, but smaller for Blacks, Hispanics, and those who homeschool. In fact, those who homeschooled experienced much less deterioration in mental health as their counterparts over the pandemic, and both Blacks and Hispanics were also more likely to homeschool their children during these years. To understand the potential protective effect of homeschooling, we show that a 1pp rise in the share of remote instruction districts is associated with a 0.018 pp increase in the probability of homeschooling. To put these estimates in perspective, the share of homeschooling was only 5% in April 2020 before jumping up to its peak of 12% in August 2020, so the marginal effect of fully transitioning from in-person to remote instruction is economically significant—it comes to 36% of the pre-pandemic mean. One potential interpretation of these results is that parents who transitioned to homeschooling were able to ensure better learning outcomes for their children, and thus overall family stability, thereby contributing to improved mental health for themselves.

These results have important implications for education policy conversations about the role of remote instruction versus in-person learning, as well as the costs associated with the wave of school closures on not only students, but also their parents. The months that followed school closures were filled with substantial uncertainty in both markets and peoples’ lives, with the bulk of the burden falling on households with dependents since they suddenly had to manage employment and care giving—assuming they were not laid off following the stay-at-home and business closure orders. We also find that the uptake in homeschooling may have served as an important form of partial insurance for many households. However, the welfare effects are not clear since the uptake in homeschooling reflects parents who may have had latent preferences and/or capabilities for it over their counterparts who were forced into it because of school closures. More research is needed to understand what types of families transitioned to homeschooling and whether they continued in those learning arrangements even into 2023. Recent data from Week 60 of the Pulse (July 26–August 7, 2023) suggests that homeschooling rates are still above pre-pandemic trends, about 6.4%, and part of the sustained uptick could stem from the deterioration of instructional quality in the pandemic.

Data and methods

All data comes from publicly available observational sources (and consequently in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations exempt from institutional review board). Statistical analysis is conducted using R.

In-person, hybrid, and remote schooling

We use data from the Return-to-Learn (R2L) Tracker, developed by the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) in partnership with the College Crisis Initiative of Davidson College4. The R2L Tracker monitored the instructional status of over 8500 public school districts on a weekly basis, examining the schools that offered fully in-person, hybrid, and fully remote instruction.

-

In-person: All students can attend school in person five days a week, with optional remote or hybrid learning for families.

-

Hybrid: Some students attend in person while others remain remote, or all students split time between in-person and remote learning for part of the week.

-

Remote: All students (except certain younger grades or subgroups) attend school entirely online with no in-person or hybrid options.

The R2L Tracker synthesized data using natural language processing from district-wide policies that are publicly displayed on district webpages, social media announcements, and/or direct contact with a district representative. Specifically, in September 2020, R2L began scraping data from websites of regular, non-charter, public school districts that had three or more schools. R2L tracked changes by identifying new content posted on district websites in a given week (by subtracting content from a previous week from a given week’s scraped data), and then used machine learning to analyze whether the new content indicated a change in operational status. Researchers from the R2L team updated the weekly time series data by reading web content and calling school districts when necessary to review the predictions of the machine learning models, affirm new changes, and review past weeks’ changes. Districts whose websites yielded no predicted changes in a given week were assumed to retain their previous instructional status. Idiosyncratic closures due to school-specific outbreaks are not reflected in our data unless they closed a grade range for the entire district for at least one week. School district websites (and pages linked to them) are treated as centralized communication hubs for all schools in those districts.

R2L expanded the sample of 2200 districts with other data sources in January 2021 to allow for school districts with three or more schools. The R2L Tracker also incorporated data from MCH Strategic Data’s “COVID-19 IMPACT: School District Status,” which created a pre-pandemic baseline for almost all of the 8400 regular public school districts in the United States with at least three schools. Their data includes up to 18 data points per district through January 2020. R2L also supplemented the MCH data with data drawn from 29 states’ departments of education for corrections and fidelity checks, making it the most comprehensive available. The data was also benchmarked against the the COVID-19 School Data Hub (CSDH) and the U.S. School Closure & Distance Learning Database13, yielding an average estimate that was exactly in the middle of the two until February 2021 and slightly lower subsequently by about 2 to 5 percentage points.

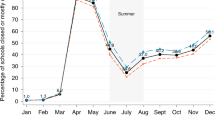

Figure 1 tracks the proportion of school districts that were in-person, hybrid, or fully remote from August 2020 to June 2021. First, we observe incredible cross-sectional variation: even by December 2020, nearly 30% of school districts were remote and 40% were hybrid. Second, we observe equally large intertemporal variation: the share of districts that were fully remote drops from 25% in fall 2020 to nearly 0% by spring 2021. These two sources of variation allow us to add fixed effects and identify the effect of remote learning. For reference, the CSDH data produces an even larger swing from 30 to 5%.

The timing and nature of school closures and subsequent reopenings during the COVID-19 pandemic were deeply influenced by state-level mandates and political factors18,19. Data from Burbio and other sources reveal stark partisan differences, with schools in Republican-leaning states offering in-person instruction at nearly twice the rate of those in Democratic-leaning states20. This disparity translated into an estimated 66 additional days (432 h) of face-to-face instruction for students in Republican states over the 2020–2021 academic year. Republican states, such as Florida, took aggressive steps to reopen schools in the fall of 2020, often implementing minimal mask mandates and other precautions while maintaining virtual options. Conversely, Democratic states, such as Oregon, relied heavily on community transmission rates to guide reopening decisions, ranking among the lowest in in-person instruction. By spring 2021, federal leadership under the Biden administration and growing vaccine availability led to accelerated reopening efforts across the country, narrowing the partisan gap. The divergence in approaches highlights how state leadership and political contexts shaped the educational landscape during the pandemic, influencing both the instructional modes available and family decision-making about homeschooling and remote learning.

Homeschooling and mental health during COVID-19

As COVID-19 began to spread, the U.S. Census Bureau collected and disseminated data on households’ experiences using the Household Pulse Survey (hereinafter, the “Pulse”), which was designed to be nationally representative and to aid policy responses. Our sample includes Phase 1 of the Pulse (deployed in April 2020) through Phase 3.1 (April 2021). While the use of the Pulse data is not ideal since we cannot match at the county or district level, no other data exists to achieve these same purposes. We note, however, that the level of aggregation should attenuate our estimates, if anything.

The Pulse asked a wide variety of questions, but for the purposes of this paper, we restrict our sample to parents of school-age children and focus on two questions regarding (1) their children’s schooling arrangements (public or private, homeschooling, or no school), and (2) their own mental health (feeling anxious, worried, uninterested in life, or depressed). We also include a rich set of controls from the Pulse, including marital status, number of household children, employment status, race, educational attainment, income, home ownership/mortgage or rental dwelling, and health insurance coverage through Medicaid.

Figure 2 shows the evolution of homeschooling during the 2020–2021 school year. The share of households homeschooling was highest in August 2020, spanning nearly 13% of households with school-aged children. Although the homeschooling rate began to decline in fall 2020 as some schools began to reopen, the rate once again climbed up in spring 2021 to over 11%. Anxiety levels among parents were high throughout the school year, with an average of 30% of parents reporting feeling anxious more than half the week. Patterns of worry, loss of interest in life, and feeling depressed follow similar trends, with peaks in the winter months.

As a validation exercise with our district-level data, Table A.8 in the SI uses a question from the Pulse survey about online schooling to regress the share of districts that were remote in a state with the share of parents with children in remote learning arrangements. We find a statistically strong association between the two, robust to the inclusion of various controls, such as demographic and COVID-19 variables. Even though the levels differ, since the R2L Tracker measures the share of districts, whereas the Pulse data measures the share of parents with children in such arrangements, the strong correlation is nonetheless comforting. We nonetheless compare our data with the COVID-19 School Data Hub (CSDH) and find a high correlation.

We also use the Thomas B. Fordham measure of teachers’ union strength at the state level, as well as whether a state has a right-to-work law. Even though the Fordham measure may have less variation than some other approaches, it has the advantage of measuring union strength based on several factors that include union membership in addition to measures of involvement in politics, scope of bargaining, state policies, and perceived influence.

Statistical models

We test how the shift to remote instruction affects parental mental health using homeschooling as a moderating factor, estimating regressions that relate mental health outcomes among parents with the share of school districts in their state that are remote within a given month, controlling for demographics, COVID-19 infections and deaths, and both state and year fixed effects:

where \(m_{ist}\) now denotes our mental health outcome of interest, h denotes whether or not a household is homeschooling, r denotes the share of remote schooling districts, X denotes our main controls, and \(\phi\) and \(\lambda\) are fixed effects on state and year. Demographic controls include marriage, number of children, work loss, race, and income. We also control for COVID factors by including lagged monthly state cases and deaths. In particular, our outcome variables for mental health are defined as a binary indicator for whether an individual experienced a negative mental health outcome “more than half the days” or “nearly every day” in the past week. The marginal effect for our main variable of interest, \(\gamma\), will be interpreted as 100 \(\times\) \(\gamma\) as percentage points. We cluster standard errors at the state-level to allow for autocorrelation in the same location over time.

The greatest concern with naive regressions of parental mental health on remote instruction is of unobserved heterogeneity across states. This could be a special concern when interpreting the interaction between remote instruction and homeschooling given that there is selection into homeschooling that potentially varies in unobserved ways over time. To address these possibilities, we implement several strategies. First, we control for state and time fixed effects, exploiting within-state variation. Second, we control for demographics and income to address changes in parental composition and/or labor market shocks that jointly affect mental health. In addition, we control for monthly state COVID-19 infections and deaths, and unemployment rate. Third, we mitigate pre-pandemic trends by interacting a state share of homeschooling in February 2020 with our variable of interest, capturing the change relative to the onset of the pandemic. Nonetheless, we recognize the potential for other unobserved time-varying factors, particularly with selection into homeschooling, preventing a fully causal interpretation.

To understand whether homeschooling is a potential mechanism behind the protective effect, we examine whether remote instruction led to an uptick in homeschooling, comparing individuals who homeschool versus those who do not in states that vary in their duration of remote instruction:

where \(h_{ist}\) denotes an indicator for whether the individual i is in a homeschooling arrangement in state s and month t, r denotes the share of remote learning school districts, X denotes a vector of individual demographic characteristics (e.g., number of children), Z denotes a vector of state-level variables (e.g., lagged COVID-19 case rates), and \(\phi\) and \(\lambda\) denote state and time (year) fixed effects, respectively. We cluster standard errors at the state-level.

The primary concern with raw correlations between the share of remote learning districts and homeschooling is that selection effects will cause significant downwards bias on \(\gamma\). On one hand, higher income families are less likely to homeschool since their opportunity cost of time is higher, causing them to allocate more time towards labor supply (i.e., \(Corr(z,\varepsilon )<0\) for an arbitrary omitted variable, z). On the other hand, higher income families are more likely to be located in areas that take overly cautious measures and/or have greater capabilities to go remote, causing them to experience higher rates of remote learning (i.e., \(Corr(z,r)>0\)). For these reasons, the raw correlation will produce misleading results that are either upwards or downwards biased. To address this concern, Eq. (2) controls for individual demographic characteristics, denoted X, as well as lagged state COVID-19 infections and deaths and union strength to proxy for the pressure that state governors and legislatures may had to enact restrictions in response to the severity of the threat (Z). Moreover, to address time-invariant heterogeneity across locations that cannot be purged through our observable controls, we introduce state and year fixed effects. For example, some states might attract fundamentally different types of parents who have a taste for homeschooling. Similarly, other states may have been adversely affected much more than others. In both cases, failing to control for these sources of heterogeneity could bias our estimate of \(\gamma\). We also control for the February 2020 share for pre-pandemic trends.

Results

Parental mental health

We begin by reporting the main results associated with Eq. (1), linking parental mental health with local school closures in Table 1. Starting in column 1 and 5, we see that a 1 pp rise in the share of remote districts in a state is associated with a 8.6 pp and 5.9 pp increase in the probability that parents experienced frequent anxiety and worry, respectively. Recognizing the potential for selection effects—for example, parents that are more likely to worry could be concentrated in states with higher shares of school closures—we now control for demographic characteristics in columns 2 and 6, producing slightly larger coefficients on remote instruction. The coefficients decline slightly in economic magnitude as we saturate the model with COVID-19 controls and fixed effects, remaining economically and statistically meaningful in columns 4 and 8: a 1pp rise in the share of remote districts is associated with a 10.5 pp and 7.4 pp increase in the probability parents experienced frequent anxiety and worry, respectively. Table A.1 in the SI replicates these results using an ordinal measure of the outcome variable, producing qualitatively similar results. Tables A.2 and A.3 in the SI report these results at the state-level, producing analogous estimates. Because the state-level estimates aggregate across people, the robustness between these two types of aggregation is noteworthy since it suggests that unobserved shocks to composition are unlikely to generate significant bias.

Table 2 reports the effect of remote instruction on additional parental mental health outcomes, namely feeling depressed and losing interest in life. While the coefficients are slightly smaller than in the previous table—which is intuitive since depression and losing interest are more extreme outcomes—the overall pattern and consistent statistical significance remains unchanged. In columns 4 and 8, a 1 pp rise in the share of remote districts is associated with a 5.3 pp and 5.8 pp rise in probability parents report feeling depressed and losing interest, respectively. Put together, the rise of remote instruction within a state over the duration of the pandemic is strongly associated with parental declines in mental health.

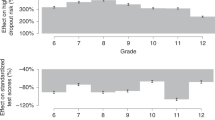

Table 3 conducts a heterogeneity analysis. First, we find that parents who homeschooled their children were much less likely to report being anxious in response to increases in the share of remote instruction (11 pp vs. 4.4 pp). Of note, the interaction with the baseline homeschooling rate in column 2 is statistically significant, albeit larger, which is comforting since it suggests that individual homeschooling—not unobserved correlates with where homeschooling was historically more common—is driving the moderate effect. Second, we find that Blacks and Hispanics were less likely to become anxious, whereas White respondents were more likely (5.9 pp vs. 12.2 pp). Third, college-educated respondents were less likely to be adversely impacted (9.3 pp vs. 5 pp), which could reflect college-educated workers residing within more digitally-intensive jobs that were less impacted by the pandemic21. This is particularly noteworthy for two reasons. First, recent evidence has highlighted the regressive effects of remote instruction, which generated larger gaps in achievement scores for lower income areas4,13. Second, Blacks and Whites are both more likely to homeschool over our sample period (Table A.9 in the SI), which we will discuss in the next section as it relates to homeschooling providing a potential protective effect. Tables A.5, A.6, and A.7 in the SI provide analogous results to these above on anxiety using our other three outcomes: worry, losing interest, and depression. The differences are qualitatively minor: the interaction with the baseline homeschooling rate is less precise and the interaction with college-educated changes when losing interest is the outcome variable.

Motivated by recent studies linking union power with remote instruction15,16,17, we examine the robustness of these results by using use the state-level ranking of pre-pandemic union power by the Fordham Institute as an instrument for the share of remote instruction (see Table A.4 in the SI). We obtain qualitatively similar coefficients on the direct effect of remote instruction (0.036 vs. 0.11) and quantitatively similar coefficients on the interaction (− 0.066 vs. − 0.109), although less statistically significant. Nonetheless, we recognize potential violations to the exclusion restriction, particularly given that we exploited cross-sectional variation among states that could be correlated with parental mental health outcomes.

Protective effects of homeschooling

Our results thus far show that the sudden and sharp surge in remote instruction led to a decline in parental mental health, but these effects were much smaller among individuals who homeschool their children and certain demographic brackets that are also more likely to homeschool. We now explore how homeschooling may have provided a protective effect over the pandemic. Table 4 documents these results. While there is little association between the share of remote school districts and the probability a parent is homeschooling their children in the cross-section (column 1), we find a 0.5 pp increase in the probability of homeschooling after controlling for demographics in column 2. As we add COVID-19 controls, the term loses magnitude and significance (column 3). However, column 4 controls for state and year fixed effects as well as additional state characteristics related to union power that are correlated with re-opening16. Our effect grows to a 2.2pp increase in the probability of homeschooling given a rise in remote districts, consistent with our concern that omitted variables produce downwards bias. These coefficients are economically significant: when considering the move towards full remote instruction (a 100% increase), the marginal effect of an increase in remote instruction comes to 44% of the pre-pandemic mean (2.2/0.05).

One concern with these results is that other time-varying shocks affect homeschooling. While we cannot rule out all possible stories of omitted variables bias, the coefficient estimate on COVID-19 deaths and infections is informative. In particular, we find a robust negative relationship: a 10% rise in deaths (infections) is associated with a 6 pp (16 pp) decline in the probability of homeschooling. In this sense, other omitted variables over the pandemic related to the rise in infections and deaths could be negatively correlated with homeschooling, thereby leading us to underestimate the effect on school districts going remote. We nonetheless recognize that there could be other substantial heterogeneity within states and across school districts. However, we cannot distinguish between public and private school districts in our data for the bulk of the sample. Fortunately, many of the mandates and guidance on reopening were made at a state-level, meaning these will be reflected in our measure.

Our results contrast with findings from some prior literature22. There are at least three possible reasons. First, they focus only on Michigan, so there could be systematic differences between homeschooling and remote schooling across states. For example, whereas 67% of students in grades K-12 are White and 18% are Black in their study, 82% are White and 7.9% are Black in our sample (and 83% and 10.3% when we restrict to Michigan). Second, they focus on data on students between Fall 2014 to Fall 2020. While they have the advantage of controlling for pre-pandemic trends, they do not capture changes that emerged following Fall 2020. For example, as we show in Section 2, the variation in learning arrangements across schools was even greater after Fall 2020. Figure A.1 in the SI plots the share of remote and hybrid school districts in Michigan with those from across the country. While the two series are correlated, there are differences, particularly with hybrid districts.

Third, to delve deeper into the potential role of the time series differences, notice that Goodman et al. measure the change in homeschooling rates from Feb. 2020 rates to Sept/Oct. 2020 and the reopening status of schools in fall 2020. However, we draw on individual-level data on homeschooling and reopening status throughout the full 2020–2021 school year. Figure A.2 in the SI replicates the results from Goodman et al. by restricting our sample of in-person and hybrid districts to September 2020. We find a positive correlation between the share of in-person and hybrid districts and the share of households homeschooling in the restricted sample. However, it is only when when considering the full breadth of the pandemic schooling experience for students and their parents—February 2020 through June 2021—that we find the relationship becomes negative.

Fourth, there could be composition effects. Motivated by the vast heterogeneity across race and income22, we control for these characteristics when estimating the elasticity across the country. The pandemic was a time of significant mobility in and out of certain states23, so such composition effects could be correlated with the pressure some schools may have been under to remain closed or re-open. For example, if wealthy households leave an area, then the schools in the area may have a greater incentive to go remote because they need to extract greater rents to stay afloat. In particular, if anything, the districts that went remote are the ones that had greater funding per student in 202015. Because we control for demographic factors, as well as various policy-level characteristics and the COVID-19 infection and death rate, we mitigate these composition effects.

Discussion

Using new data on the share of remote learning school districts in a state, coupled with the Census Pulse Survey, we begin by documenting the patterns in remote, hybrid, in-person, and homeschooling instruction during the 2020–2021 school year, as well as parental mental health during this time. These are, to our knowledge, the first time that such patterns have been documented on a large, ongoing, and nationally representative data-set. Next, we estimate how increases in the share of remote learning districts in a state influenced the probability that a parent homeschooled their child, and homeschooling may potentially offset the mental health effects of the switch to remote instruction. Exploiting within-state variation and controlling for both demographics and COVID-19 case/death rates, we find statistically and economically significant declines in multiple measures of parental mental health, as well as evidence that homeschooling behaved as a partial shield to mental health declines during these years. While we cannot fully isolate the causal mechanism, we nonetheless offer preliminary evidence that some parents may have had latent preferences or capabilities to homeschool more effectively even after schools began opening back up.

Our findings point to not only widespread challenges faced by families during the pandemic, but also the uneven effects of remote instruction across districts. Districts serving lower-income or marginalized communities likely faced greater difficulties in transitioning to remote instruction due to pre-existing inequities in access to technology and internet connectivity. Research has documented that students in such districts often lacked the resources necessary to engage effectively with online learning platforms, further exacerbating educational disparities2,4,13. The additional burden placed on parents in these communities—who may have had less flexibility in their work arrangements or fewer resources to support remote learning (e.g., child care availability8)—likely compounded the mental health effects we observed. Conversely, districts with more robust infrastructures and greater fiscal resources may have been better equipped to adapt to the sudden shift24. Our results show how these differences, including the capabilities of families to homeschool, shaped the resilience of educational systems during the crisis, affecting both student outcomes and parental well-being. Policymakers must consider these disparities when designing interventions, ensuring that districts serving disadvantaged populations receive targeted support to mitigate future disruptions.

The role of state-level policies and local governance also warrants closer attention. Districts in states with strong teachers’ unions or stricter public health mandates were more likely to remain remote for longer periods15,17, which contributed to the politicization of re-opening in Republican versus Democrat states18,19,20. For instance, districts in Democratic-leaning states may have had greater reliance on hybrid and fully-remote models, which provided less and lower quality instructional time than fully in-person schooling and required parents to shoulder a larger share of educational responsibilities. While these decisions may have been driven by legitimate health concerns, they disproportionately affected families in these areas who had to navigate extended periods of remote learning. Our analysis shows that the mental health toll was not evenly distributed: parents in such districts experienced more sustained declines in well-being with limited opportunities to transition their children to alternative arrangements like homeschooling, particularly given the reduced availability of child care from increased regulation8,9.

While there has been substantial focus on COVID-induced learning disruptions on students3,25,26, there has been less focus on parental outcomes. Prior literature shows that these disparities impact learner outcomes, which have been widely documented27,28. Lower-income districts experienced larger learning losses, widening achievement gaps that were already present before the pandemic2,4. Our findings suggest that these educational disruptions also affected parents, creating feedback loops that could exacerbate inequities in human capital formation. When parents in resource-constrained districts experience declines in mental health, their ability to support their children’s learning may diminish, further entrenching disparities. Addressing these interconnected challenges requires a holistic approach that supports both students and families.

Future research should examine the characteristics of districts that managed to adapt more effectively to the pandemic. Understanding the policies and practices that enabled certain districts to mitigate the negative effects of remote instruction could inform the design of more resilient education systems. For instance, districts that implemented robust hybrid learning models or provided comprehensive support for parents may offer valuable lessons for handling future disruptions. Moreover, the long-term consequences of the pandemic for district-level funding and policy priorities remain an open question. As families increasingly explore alternative education models, public schools may need to re-evaluate their offerings to retain enrollment and ensure quality. Such analyses should be conducted as much as possible at the individual-level to allow for more precise estimates and allow for greater degrees of heterogeneity. Nonetheless, this study contributes to a broader understanding of the pandemic’s impact on families and the moderating role that homeschooling played. These insights are crucial for policymakers and educators seeking to build more equitable and adaptable systems in the face of ongoing and future challenges.

The Share of U.S. School Districts with In-Person, Hybrid, and Remote Instruction. Source: Return to Learn Tracker, 2020–2021 SY. In-person: All grade levels can attend school in buildings five days per week. Hybrid: Either students in some grades can return to buildings in person while other grades only return in a hybrid or remote model or all students can return to buildings for four days or less each week (or five partial days) while learning remotely from home in the remainder. Remote: All grade levels above first grade participate in virtual instruction five days per week, with no option for in-person or hybrid learning. Districts that only allowed in-person or hybrid instruction for prekindergarten, kindergarten, first grade, or select subgroups of students are included in this category..

Data availability

These data will be provided upon request. Please contact cmakridi@stanford.edu for the data files. All data comes from publicly available sources.

References

Azevedo, J. P., Hasan, A., Goldemberg, D., Geven, K. & Iqbal, S. A. Simulating the potential impacts of covid-19 school closures on schooling and learning outcomes: A set of global estimates. World Bank Res. Observ. 36, 1–40 (2021).

Engzell, P., Frey, A. & Verhagen, M. D. Learning loss due to school closures during the covid-19 pandemic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118 (2021).

Duckworth, A. et al. Students attending school remotely suffer socially, emotionally, and academically. Educ. Res. 50, 479–482 (2021).

Goldhaber, D. et al. The educational consequences of remote and hybrid instruction during the pandemic. Am. Econ. Rev. Insights 5, 377–392 (2023).

Beals, M. Student test scores fall for first time in national test’s history. The Hill (2021).

Eggleston, C. & Fields, J. Homeschooling on the rise during covid-19 pandemic (2021).

Bjorklund-Young, A. & Watson, A. Suddenly homeschooling? A parent’s survival guide to schooling during covid-19 (2020).

Ali, U., Herbst, C. & Makridis, C. A. Minimum quality regulations and the demand for child care labor. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 43, 660–695 (2024).

Ali, U., Herbst, C. & Makridis, C. A. The impact of covid-19 on the u.s. child care market: Evidence from stay-at-home orders. Econ. Educ. Rev. 82 (2021).

Patrick, S. W. et al. Well-being of parents and children during the covid-19 pandemic: A national survey. Pediatrics 146 (2020).

Feinberg, M. E. et al. Impact of the covid-19 pandemic on parent, child, and family functioning. Family Process (Early View) (2021).

Jace, C. & Makridis, C. A. Does marriage protect mental health? Evidence from the covid-19 pandemic. Soc. Sci. Quart. (Early View) (2021).

Parolin, Z. & Lee, E. K. Large socio-economic, geographic and demographic disparities exist in exposure to school closures. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 522–528. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01087-8 (2021).

Lassi, N. Remote learning and parent depression during the covid-19 pandemic. Educ. Res. Quart. 46, 40–70 (2022).

DeAngelis, C. & Makridis, C. A. Are school reopening decisions related to funding? evidence from over 12,000 districts during the covid-19 pandemic. J. School Choice 16(3), 454–476 (2022).

DeAngelis, C. & Makridis, C. A. Are school reopening decisions related to union influence?. Soc. Sci. Quart. 102, 2266–2284 (2021).

Hartney, M. T. & Finger, L. K. Politics, markets, and pandemics: Public education’s response to covid-19. Perspect. Polit. 20, 1–17 (2021).

Grossmann, M., Reckhow, S., Strunk, K. O. & Turner, M. All states close but red districts reopen: The politics of in-person schooling during the covid-19 pandemic. Educ. Res. 50, 637–648 (2021).

Canes-Wrone, B., Rothwell, J. & Makridis, C. A. When can individual partisanship be tempered? Mass behavior and attitudes across the covid-19 pandemic. SSRN Working Paper (2024).

Lehrer-Small, A. One fate, two fates. red states, blue states: New data reveal a 432-hour in-person learning gap produced by the politics of pandemic schooling. The74 (2021).

Gallipoli, G. & Makridis, C. A. Sectoral digital intensity and gdp growth after a large employment shock: A simple extrapolation exercise. Can. J. Econ. 55, 446–479 (2022).

Musaddiq, T., Stange, K. M., Bacher-Hicks, A. & Goodman, J. The pandemic’s effect on demand for public schools, homeschooling, and private schools. J. Public Econ. 212 (2022).

Coven, J., Gupta, A. & Yao, I. Urban flight seeded the covid-19 pandemic across the United States. J. Urban Econ. Insights (2020).

Golden, A. R., Srisarajivakul, E. N., Hasselle, A. J., Pfund, R. A. & Knox, J. What was a gap is now a chasm: Remote schooling, the digital divide, and educational inequities resulting from the covid-19 pandemic. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 52, 101632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2023.101632 (2023).

Verlenden, J. V. et al. Instruction with Child and Parent Experiences and Well-Being During the Covid-19 Pandemic-Covid Experiences Survey, United States. (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020).

Halloran, C., Jack, R., Okun, J. C. & Oster, E. Pandemic schooling mode and student test scores: Evidence from us school districts. Am. Econ. Rev. Insights 5, 173–90 (2023).

Guryan, J., Hurst, E. & Kearney, M. Parental education and parental time with children. J. Econ. Perspect. 22, 23–46 (2008).

Cunha, F., Heckman, J. J. & Schennach, S. M. Estimating the technology of cognitive and noncognitive skill formation. Econometrica 78, 883–931 (2010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Christos Makridis initiated the study, wrote the paper, conducted some analysis, and reviewed the analysis. Clara Piano contributed to the paper and conducted all the statistical analysis. Corey DeAngelis reviewed the analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Makridis, C.A., Piano, C. & DeAngelis, C. Remote instruction adversely impacts parental mental health, less among homeschoolers. Sci Rep 15, 5351 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89804-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89804-5