Abstract

Mitochondria are required for protecting host against pathogenic bacteria by activating mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt). Chlorogenic acid (CGA), a phenolic acid compound of green coffee extracts and tea has been shown to exhibit activities such as antioxidant, antibacterial, hepatoprotective, cardioprotective, anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, anti-obesity. However, whether CGA regulates innate immunity and the underlying molecular mechanisms remain unknown. In this study, we found that CGA increased resistance to Gram-negative pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 in dose dependent manner. Meanwhile, CGA enhanced innate immunity in Caenorhabditis elegans by reducing intestinal bacterial burden. CGA also inhibited the proliferation of pathogenic bacteria. Importantly, CGA inhibited the production of Pseudomonas toxin pyocyanin (PYO) to protect C. elegans from P. aeruginosa PA14 infection. Furthermore, CGA activated the UPRmt and expression of antibacterial peptide genes to promote innate immunity in C. elegans via transcription factor ATFS-1(activating transcription factor associated with stress-1). Unexpectedly, CGA enhanced innate immunity independently of other known innate immune pathways. Intriguingly, CGA also protected mice from P. aeruginosa PA14 infection and activated UPRmt. Our work revealed a conserved mechanism by which CGA promoted innate immunity and boosted its therapeutic application in the treatment of pathogen infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the growing concern regarding the drug resistance of using antibiotic, the attention towards natural and herbal substances that enhancing immune defenses against pathogens by strengthening host innate immunity has been increasing every day. Chlorogenic acid (CGA) is one of the most available acids among phenolic acid compounds, which widely distributes in plants and utilizes in traditional Chinese medicines1. CGA possesses a wide range of pharmacological effects such as antioxidant activity, antibacterial, hepatoprotective, cardioprotective, anti-inflammatory, antipyretic, neuroprotective, anti-obesity, antiviral, anti-microbial, anti-hypertension2. Meanwhile, CGA improves efficacy in the cancer immunotherapy via T cell regulation1. Recent study has shown that CGA extends lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans3,4. Furthermore, CGA influences lipid metabolism via liver PPAR-α (Peroxisome Proliferator-activated Receptor α)5. However, whether CGA regulates innate immunity and the underlying molecular mechanisms are largely unknown.

Innate immunity is at the front line of our defense system against invading pathogenic microorganisms, which is evolutionarily conserved from nematodes to mammals6,7. During pathogens infection, the innate immunity is activated, and aroused antimicrobial response to invading pathogenic microorganisms6,8,9,10,11. Caenorhabditis elegans has been developed as a valuable genetic model for research on the animal immune response. In contrast, pathogenic bacteria produce different metabolites that are involved in growth and virulence12,13. P. aeruginosa is a common opportunistic pathogen in clinical practice. P. aeruginosa causes infection in patients by secreting a wide array of virulence factors, such as pyocyanin14, phenazine-1-carboxamide15, hydrogen cyanide16 and iron chelating siderophores16.

UPRmt refers to the stress response of mitochondria to activate the transcriptional activation program of mitochondrial heat shock proteins and proteases, which plays important role in antibacterial immunity16,17. In general, UPRmt sends signals to the nucleus through the mitochondrial peptide exporter HAF-1 and up-regulates transcription factor ATFS-1(activating transcription factor associated with stress-1)18. In addition, UPRmt also induces transcription of ubiquitin-like protein 5 (UBL-5), which binds to DVE-1 (defective proventriculus protein 1) to form a complex that promotes the expression of mitochondrial HSP6019. During P. aeruginosa infection, ATFS-1-dependent UPRmt is activated, which is followed by the increased expression of mitochondrial protective genes and antibacterial peptide genes16. ATF5 (activating transcription factor 5), homologous gene of ATFS-1 in C. elegans, also regulates mitochondrial stress response in mammalian cells20.

Our study investigated the role of CGA in the host defenses against pathogen infection. CGA inhibited Pseudomonas toxin pyocyanin to protect host from P. aeruginosa PA14 infection. Furthermore, CGA activated ATFS-1-dependent UPRmt, which is followed by the increased expression of mitochondrial protective and antibacterial peptide genes. CGA also increased resistance to P. aeruginosa PA14 infection and activated UPRmt in mice. These findings revealed that the CGA properties related to innate immunity might significantly boost its application to infectious diseases.

Results

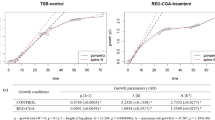

Chlorogenic acid promotes innate immunity in C. Elegans

To investigate whether Chlorogenic acid (CGA) promoted innate immunity, animals were exposed to P. aeruginosa PA14. We found that wild-type worms treated with CGA (0 µM, 1 µM, 10 µM, 100 µM) exhibited increased resistance to P. aeruginosa PA14 in dose dependent manner (Fig. 1A; Table S1). These results suggested that CGA enhanced innate immunity in C. elegans. Meanwhile, we observed that CGA (1 µM, 10 µM, 100 µM) also extended lifespan of wild-type animals that were fed heat-killed P. aeruginosa PA14 in dose dependent manner (Fig. 1B; Table S1). After CGA treatment, worms exposed to Staphylococcus aureus, and Listeria monocytogenes exhibited a higher survival rate (Figure S1A and S1B). These results suggested that CGA exhibited a broad spectrum of pathogen resistance. Furthermore, we performed the bacterial growth assay and found that 100 µM Chlorogenic acid significantly inhibited the proliferation of P. aeruginosa PA14 (*P < 0.05) (Fig. 1C). Because clearance of the intestinal pathogenic bacteria loads is part of host defense against pathogens infection21. Subsequently, we detected bacteria accumulation in the intestine after CGA treatment, and found that CGA significantly decreased the number of bacterial cells in the intestine compared to control animals (*P < 0.05) (Fig. 1D). These results indicated that CGA enhanced the resistance to pathogen infection.

Chlorogenic acid promotes innate immunity in C. elegans. (A) CGA promoted innate immunity in dose-dependent manner. (*P < 0.05, log-rank test). See Table S1 for survival data. (B) Survival of N2 animals exposed to heat-killed P. aeruginosa PA14 after CGA treatment. (*P < 0.05; log-rank test). See Table S1 for survival data. (C) 100 µM CGA significantly inhibited the proliferation of P. aeruginosa PA14. (*P < 0.05, log-rank test). Error bars represent mean ± SEM of three independent biological replicates. (D) 100 µM CGA decreased the intestinal bacteria burden in WT worms after P. aeruginosa PA14 infection 48 h. (n ≥ 20). These results are mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. (*P < 0.05, unpaired t-test).

Chlorogenic acid inhibits Pseudomonas toxin pyocyanin to protect C. Elegans from pathogen infection

Pseudomonas toxin pyocyanin (PYO) is an important virulence factor in P. aeruginosa PA1422, which is synthesized from phenazine-1-carboxylic acid, a process that is mediated by phenazine-specific methytransferase, PhzM23. We found that CGA significantly inhibited the production of PYO (*P < 0.05) (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, worms infected with the ΔphzM mutant increased the survival, compared with those infected with the wild-type (WT) PA14 strain (Fig. 2B). However, PYO (25 µg/ml)15 supplement rescued the long-live phenotype in animals infected with the ΔphzM mutant (Fig. 2B). Meanwhile, CGA increased the survival in worms infected with the wild-type PA14 strain and animals infected with the ΔphzM mutant + PYO (25 µg/ml) (Fig. 2B). CGA partially prolonged the survival rate of worms infected with the ΔphzM mutant (Fig. 2B). In addition, CGA reduced the intestinal bacteria loads in worms infected with the wild-type PA14 strain, or animals infected with the ΔphzM mutant, and animals infected with the ΔphzM mutant + PYO (25 µg/ml) (Fig. 2C). These results indicated that CGA enhanced the resistance to P. aeruginosa PA14 infection by inhibiting the production of PYO.

Chlorogenic acid inhibits the prodction of Pseudomonas toxin pyocyanin to protect C. elegans from pathogen infection. (A) 100 µM CGA inhibited the production of PYO. (B) Survival of N2 worms exposed to wild type P. aeruginosa PA14, ΔphzM mutant, and ΔphzM mutant + PYO (25 µg/ml) after CGA treatment. (*P < 0.05; log-rank test). See Table S1 for survival data. (C) The CFUs of N2 worms exposed to wild type P. aeruginosa PA14, ΔphzM mutant, and ΔphzM mutant + PYO (25 µg/ml) after CGA treatment. These results are mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. (*P < 0.05, unpaired t-test).

Chlorogenic acid activates mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt) to enhance innate immunity through ATFS-1

Mitochondria play key roles in antibacterial innate immunity by regulating UPRmt16,24. Next, we asked if CGA treatment induced mitochondrial stress capable of activating the UPRmt. We found that CGA significantly increased mitochondrial chaperone reporter hsp-6::gfp activation in the intestine (*P < 0.05) (Fig. 3A). In general, UPRmt induces transcription of atfs-1, ubl-5, and dve-1. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis demonstrated that 100 µM CGA significantly increased the mRNA levels of atfs-1rather than ubl-5, and dve-1 compared with the control (*P < 0.05) (Fig. 3B). To further confirm whether CGA activated the transcription factor ATFS-1, we detected the cellular translocation of ATFS-1 using transgenic worms that express a functional ATFS-1::GFP fusion protein. We found that 100 µM CGA significantly induced ATFS-1 nuclear localization in the intestine (*P < 0.05) (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, we tested the expression of ATFS-1-targeted immune response genes such as abf-2, lys-2, clec-4, and clec-65 and mitochondrial protective genes such as hsp-6 and hsp-60. We found that ATFS-1-targeted immune response genes and mitochondrial protective genes were up-regulated in 100 µM CGA-treated worms, compared with the control (Fig. 3D). However, 100 µM CGA failed to increase these genes expression in atfs-1(gk3094) mutant worms (Fig. 3D). In addition, we found that 100 µM CGA failed to enhance the resistance to P. aeruginosa PA14 infection in atfs-1(gk3094) mutant worms (Fig. 3E). These results suggested that CGA activated UPRmt to enhance innate immunity by ATFS-1.

Chlorogenic acid activates mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt) to enhance innate immunity through ATFS-1. (A) 100 µM CGA increased the expression of hsp-6::GFP. The right panel shows quantification of hsp-6::GFP. (n ≥ 30). Scale bars: 100 μm. These results are mean ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. (*P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA). (B) The mRNA levels of atfs-1, dve-1 and ubl-5 in worms exposed to 100 µM CGA. These results are mean ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. (*P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA). NS, no significance. (C) 100 µM CGA significantly induced ATFS-1 nuclear localization. The right panel shows the quantification of ATFS-1::GFP (n ≥ 30). Scale bars: 50 μm. These results are mean ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. (*P < 0.05, unpaired t-test). (D) The mRNA levels of ATFS-1-targeted immune response genes such as abf-2, lys-2, clec-4, and clec-65 and mitochondrial protective genes such as hsp-6 and hsp-60 in worms expose to 100 µM CGA. These results are mean ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. (*P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA). (E) 100 µM CGA failed to enhance resistance to P. aeruginosa PA14 infection in atfs-1(gk3094) mutant animals. (log-rank test). See Table S1 for survival data.

Chlorogenic acid extends survival independently of other known innate immune pathways

Next, we investigated if CGA interacted with established C. elegans innate immunity pathways, which included PMK-1/p38 MAPK25, MPK-1/ERK MAPK26, the MLK-1/MEK-1/KGB-1 c-Jun kinase pathway27,28, transcription factor ZIP-229,30, and endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response XBP-131. We found that 100 µM CGA increased the survival rates of N2, pmk-1(km25), mpk-1(n2521), mlk-1(ok2471), zip-2(ok3730), and xbp-1(zc12) mutant worms, after P. aeruginosa PA14 infection (Fig. 4A–F; Table S1). These results suggested that CGA promoted innate immunity in C. elegans independently of other known innate immune pathways.

Chlorogenic acid extends survival independently of other known innate immune pathways. (A–F) Survival of (N2) (A), pmk-1(km25) (B), mpk-1(n2521) (C), mlk-1(ok2471) (D), zip-2(ok3730) (E), and xbp-1(zc12) (F) mutant worms exposed to P. aeruginosa PA14 after 100 µM CGA treatment. (*P < 0.05, log-rank test). See Table S1 for survival data.

Chlorogenic acid protects mice from P. aeruginosa PA14 infection

Next, we asked if CGA promoted innate immunity in mice. CGA treatment mice (50 mg/kg body weight) and control mice were infected with P. aeruginosa PA14 (1.0 × 106 CFUs/mouse). We found that CGA enhanced resistance to P. aeruginosa PA14 infection in wild-type mice (Fig. 5A). Meanwhile, we tested bacterial loads in lung tissue by quantifying colony-forming units (CFUs) of live bacterial cells. We found that CGA reduced the CFUs of P. aeruginosa PA14 than control mice (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, we found that CGA increased the mRNA levels of mouse UPRmt genes HSPD1, HSPA9, LONP1, and YME1L1 in lung tissue (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, consistent with the role in C. elegans, CGA also significantly increased the protein levels of ATF5 (homologous gene of ATFS-1 in C. elegans) in lung tissue (*P < 0.05) (Fig. 5D). These results suggested that CGA promoted innate immunity and activated UPRmt in mice.

Chlorogenic acid protects mice from P. aeruginosa PA14 infection. (A) CGA treatment (50 mg/kg body weight) enhanced resistance to P. aeruginosa PA14 infection in wild-type mice. (*P < 0.05, log-rank test). (B) The CFUs of P. aeruginosa from lung homogenates plated on LB agar plates after CGA treatment. (C)

CGA increased the mRNA levels of mouse UPRmt genes HSPD1, HSPA9, LONP1, and YME1L1 in lung tissue. These results are mean ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. (*P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA). (D) CGA increased the protein levels of ATF5 in lung tissue. The right panel shows quantification of ATF5. These results are mean ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. (*P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA).

Discussion

Chlorogenic acid (CGA) is one of the most available acids among phenolic acid compounds1, which exhibits a wide range of pharmacological activities, such as antioxidant activity, antibacterial, hepatoprotective, cardioprotective, anti-inflammatory, antipyretic, neuroprotective, anti-obesity, antiviral, and, anti-hypertension2. However, the molecular mechanisms by which it promotes innate immunity remain unknown. Here, we demonstrated that preventive application of CGA protected C. elegans from Gram-negative pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 and Gram-positive pathogens Staphylococcus aureus and Listeria monocytogenes infection. Through innate immune pathways screening, this effect appeared to involve a conserved mechanism that influenced innate immunity in host, including ATFS-1 dependent UPRmt. Importantly, Our findings provided an evidence that CGA inhibited PYO, which was an important virulence factor in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA1412,13. It should be noted that CGA partially prolonged the survival rate of worms infected with the ΔphzM mutant. In addition, CGA reduced the intestinal bacteria loads in worms infected with the wild-type PA14 strain, or animals infected with the ΔphzM mutant, and animals infected with the ΔphzM mutant + PYO (25 µg/ml), suggesting that PYO is not the only factor that is inhibited by CGA. Furthermore, our results indicated that the enhancement of immune responses by CGA required the activation of immune response genes such as abf-2, lys-2, clec-4, and clec-65 and mitochondrial protective genes such as hsp-6 and hsp-60. Thus, our findings provided an alternative mechanism by which antibiotic action like CGA defended host against pathogen infection.

Accumulating evidence indicates that mitochondria play key roles in the resistance of host against pathogen infection by activation UPRmt. For example, mitochondrial aconitase ACO-2 inhibits innate immunity against pathogenic bacteria in C. elegans32. Mitochondrial chaperone HSP-60/HSPD1 enhances antibacterial immunity in C. elegans and human cells by targeting p38 MAPK pathway24. UPRmt also increases the expression of antimicrobial genes in C. elegans in an ATFS-1-dependent manner and contributes to antibacterial innate immunity16. Furthermore, the increased expression of HSP60 in intestinal epithelial cells of colitis model animals and inflammatory bowel disease patients also indicates that UPRmt response may be a key response for intestinal mucosal cells to detect pathogenic infection and improve the innate immunity of cells33. In this study, we found that CGA enhanced resistance to P. aeruginosa PA14 infection in mice by clearance bacteria loads of lung tissue. Importantly, ATF5/ATFS-1 not only induced UPRmt in nematodes, but also induced high expression of mitochondrial heat shock protein HSP60/HSPD1, HSP70/HSPA9, and mitochondrial protease LONP1 and antimicrobial peptide HD-5 (human defensin 5) in mammalian cells20. Intriguingly, we found that CGA increased the mRNA levels of mouse UPRmt genes HSPD1, HSPA9, LONP1, and YME1L1 in lung tissue. Furthermore, consistent with the role in C. elegans, CGA also increased the protein levels of ATF5 in lung tissue, suggesting that CGA might activate UPRmt to protect mice from pathogen infection. Based on the observations that CGA can promote antibacterial immunity in worms and mice, our findings suggest that CGA may exhibit significant benefits by improving infectious diseases in mammals.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Chlorogenic acid was obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO) and dissolved in Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as a stock solution at a 100 mM concentration and stored in aliquots at – 20 °C.

Nematode strains

N2 Bristol wild-type, VC3056 zip-2(ok3730), RB1908 mlk-1(ok2471), KU25 pmk-1(km25), SJ17 xbp-1(zc12), VC3201 atfs-1(gk3094), SD184 mpk-1(n2521), OP675 atfs-1::GFP, and SJ4100 hsp-6p::GFP were obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC).

Slow-killing assay

P. aeruginosa PA14 was grown in LB (Lauria Bertani) broth at 37 °C and 180 rpm overnight, and 100 µL of the bacterial solution was spread to the NGM plates supplemented with or without Chlorogenic acid (0, 1, 10, 100 µM) and PYO (25 µg/ml). When the bacteria liquid was dried, the plates were incubated at 37 °C in a constant temperature incubator for 16–18 h and subsequently moved to a 25 °C constant temperature incubator for 3 h. The synchronized worms were cultivated on NGM plates containing E. coli OP50 until the young adult stage and 40–80 worms were transferred to the plates containing P. aeruginosa PA14. The samples were observed at 12 h intervals, and touch with picker no response worms were recorded as dead34. Each set of experiments were conducted on three plates, and all experiments were repeated three times independently.

Bacterial proliferation assay

Bacterial colonies were inoculated into LB broth, and equal volumes of the bacterial suspension was added to LB broth (with or without 100 µM Chlorogenic acid) and maintained at 37 °C and 180 rpm. The optical density (OD 600 nm) was measured every 3 h. Three replicates were tested in each group, and all experiments were repeated three times independently.

Quantification of intestinal bacterial loads

The synchronized worms were cultivated on E.coli OP50 at 20 °C until the young adult stage. Next, animals were transferred to NGM agar plates (supplemented with or without 100 µM Chlorogenic acid) and PYO (25 µg/ml) containing P. aeruginosa/GFP for two days at 25 °C7,35. Twenty worms were transferred into 100 uL Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS) containing 0.1% Triton and ground. After 24 h of incubation at 37 °C, the colonies of P. aeruginosa /GFP were counted. Three plates were detected per assay and all experiments were repeated three times independently.

Fluorescence microscopy

The synchronized worms were cultivated on E. coli OP50 at 20 °C until the young adult stage supplemented with or without 100 µM Chlorogenic acid. The images were obtained by using Zeiss Axioskop 2 plus fluorescence microscope. Fluorescence intensity quantification was analyzed by using Image J software. Three plates were used for each group of experiments, and three independent replications were performed for each experiment.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from worms or lung tissue with TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen) as previously described7. cDNA was synthesized with reverse transcription kits (Invitrogen) and qPCR analysis was carried out using SYBR Premix-Ex TagTM (Takara, Dalian, China). For quantification, C. elegans transcripts were normalized to pmp-336, and transcripts from lung tissue were normalized to ACTB. Primer sequences for qPCR were listed in Table S2.

Western blotting

Lung tissue were homogenized in liquid nitrogen, and added to protein lysate and placed on ice for 30 min. Samples were separated on a 10% SDS polyacrylamide gel and transferred to PVDF membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Primary antibodies against ATF5 (Abcam, ab184923, 1:1000 dilution), and ACTB (Abcam, ab227387, 1:1000 dilution) were used. Membranes were developed with Supersignal chemiluminescence substrate (Pierce). The band intensity was measured by Image J software.

Animal study and colony counting of lung in mice

C57BL/6 mice were inoculated with P. aeruginosa PA14-laden agarose beads contained 1.0 × 106 CFUs/mouse, as previously described7,37. Some of animals received daily doses of 50 mg/kg body weight CGA through intraperitoneal injection for 6 d. Lung tissue homogenates were taken from the mice, and the number of colonies of P. aeruginosa PA14 was determined by serial dilution.

ARRIVE guidelines Compliance: All methods are reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines. All mouse studies were carried out under standard conditions and in accordance with Zunyi Medical University Animal Care Committee (ZMU21-2305-003) guidelines. All animals were obtained from Zunyi Medical University.

After the experiment, the animals were killed by cervical dislocation after anesthesia. The anesthetic was administered with pentobarbital sodium with a concentration of 2% and a dose of 50 mg/kg, which was injected into the abdomen.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 7.0. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses for all data were carried out using Student’s t-test (unpaired, two-tailed) or ANOVA after testing for equal distribution of the data and equal variances within the data set. Survival data were analyzed by using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. *P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Data availability

The data that support the fingings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Zhang, Y. et al. Construction of chlorogenic acid-containing liposomes with prolonged antitumor immunity based on T cell regulation. Sci. China Life Sci. 64 (7), 1097–1115 (2021).

Naveed, M. et al. Chlorogenic acid (CGA): a pharmacological review and call for further research. Biomed. Pharmacother. 97, 67–74 (2018).

Zheng, S. Q. et al. Chlorogenic acid extends the Lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans via Insulin/IGF-1 signaling pathway. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 72 (4), 464–472 (2017).

Siswanto, F. M. et al. Chlorogenic acid activates Nrf2/SKN-1 and prolongs the Lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans via the Akt-FOXO3/DAF16a-DDB1 pathway and activation of DAF16f. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 77 (8), 1503–1516 (2022).

Kumar, R. et al. Therapeutic promises of chlorogenic acid with special emphasis on its Anti-obesity Property. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 13 (1), 7–16 (2020).

Aballay, A. & Ausubel, F. M. Caenorhabditis elegans as a host for the study of host-pathogen interactions. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 5 (1), 97–101 (2002).

Xiao, Y. et al. Metformin promotes innate immunity through a conserved PMK-1/p38 MAPK pathway. Virulence 11 (1), 39–48 (2020).

Xiao, Y. et al. PKA/KIN-1 mediates innate immune responses to bacterial pathogens in Caenorhabditis elegans. Innate Immun. 23 (8), 656–666 (2017).

Irazoqui, J. E., Urbach, J. M. & Ausubel, F. M. Evolution of host innate defence: insights from Caenorhabditis elegans and primitive invertebrates. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10 (1), 47–58 (2010).

Kim, D. Studying host-pathogen interactions and innate immunity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dis. Model. Mech. 1 (4–5), 205–208 (2008).

Kurz, C. L. & Ewbank, J. J. Caenorhabditis elegans: an emerging genetic model for the study of innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Genet. 4 (5), 380–390 (2003).

Dorrestein, P. C., Mazmanian, S. K. & Knight, R. Finding the missing links among metabolites, microbes, and the host. Immunity 40 (6), 824–832 (2014).

Saunders, S. H. et al. Extracellular DNA promotes efficient Extracellular Electron transfer by Pyocyanin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms. Cell 182 (4), 919–932e19 (2020).

Yang, Z. S. et al. Pseudomonas toxin pyocyanin triggers autophagy: implications for pathoadaptive mutations. Autophagy 12 (6), 1015–1028 (2016).

Peterson, N. D. et al. Non-canonical pattern recognition of a pathogen-derived metabolite by a nuclear hormone receptor identifies virulent bacteria in C. Elegans. Immunity 56 (4), 768–782e9 (2023).

Pellegrino, M. W. et al. Mitochondrial UPR-regulated innate immunity provides resistance to pathogen infection. Nature 516 (7531), 414–417 (2014).

Haynes, C. M., Fiorese, C. J. & Lin, Y. F. Evaluating and responding to mitochondrial dysfunction: the mitochondrial unfolded-protein response and beyond. Trends Cell. Biol. 23 (7), 311–318 (2013).

Haynes, C. M. et al. The matrix peptide exporter HAF-1 signals a mitochondrial UPR by activating the transcription factor ZC376.7 in C. Elegans. Mol. Cell. 37 (4), 529–540 (2010).

Haynes, C. M. et al. ClpP mediates activation of a mitochondrial unfolded protein response in C. Elegans. Dev. Cell. 13 (4), 467–480 (2007).

Fiorese, C. J. et al. The transcription factor ATF5 mediates a mammalian mitochondrial UPR. Curr. Biol. 26 (15), 2037–2043 (2016).

Liu, F. et al. The homeodomain transcription factor CEH-37 regulates PMK-1/p38 MAPK pathway to protect against intestinal infection via the phosphatase VHP-1. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 80 (11), 312 (2023).

Sadikot, R. T. et al. Pathogen-host interactions in Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 171 (11), 1209–1223 (2005).

Rada, B. & Leto, T. L. Pyocyanin effects on respiratory epithelium: relevance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa airway infections. Trends Microbiol. 21 (2), 73–81 (2013).

Jeong, D. E. et al. Mitochondrial chaperone HSP-60 regulates anti-bacterial immunity via p38 MAP kinase signaling. EMBO J. 36 (8), 1046–1065 (2017).

Kim, D. H. et al. A conserved p38 MAP kinase pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans innate immunity. Science 297 (5581), 623–626 (2002).

Zou, C. G. et al. Autophagy protects C. Elegans against necrosis during Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 111 (34), 12480–12485 (2014).

Twumasi-Boateng, K. et al. An age-dependent reversal in the protective capacities of JNK signaling shortens Caenorhabditis elegans lifespan. Aging Cell. 11 (4), 659–667 (2012).

Kim, D. H. et al. Integration of Caenorhabditis elegans MAPK pathways mediating immunity and stress resistance by MEK-1 MAPK kinase and VHP-1 MAPK phosphatase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 101 (30), 10990–10994 (2004).

McEwan, D. L., Kirienko, N. V. & Ausubel, F. M. Host translational inhibition by Pseudomonas aeruginosa Exotoxin A triggers an immune response in Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell. Host Microbe. 11 (4), 364–374 (2012).

Estes, K. A. et al. bZIP transcription factor zip-2 mediates an early response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 107 (5), 2153–2158 (2010).

Richardson, C. E., Kooistra, T. & Kim, D. H. An essential role for XBP-1 in host protection against immune activation in C. Elegans. Nature 463 (7284), 1092–1095 (2010).

Kim, E. et al. Mitochondrial aconitase suppresses immunity by modulating oxaloacetate and the mitochondrial unfolded protein response. Nat. Commun. 14 (1), 3716 (2023).

Rath, E. & Haller, D. Unfolded protein responses in the intestinal epithelium: sensors for the microbial and metabolic environment. J Clin Gastroenterol, 46 Suppl: pp. S3-5. (2012).

Liu, F. et al. Sanguinarine promotes healthspan and innate immunity through a conserved mechanism of ROS-mediated PMK-1/SKN-1 activation. iScience 25 (3), 103874 (2022).

Sun, J. et al. Neuronal GPCR controls innate immunity by regulating noncanonical unfolded protein response genes. Science 332 (6030), 729–732 (2011).

Xiao, Y. et al. Dioscin Activates Endoplasmic Reticulum UPR for Defense against Pathogen bacteria in Caenorhabditis elegans via IRE-1/XBP-1 Pathway (J Infect Dis, 2023).

Xiao, Y. et al. Schisandrin a enhances pathogens resistance by targeting a conserved p38 MAPK pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 128, 111472 (2024).

Funding

This study is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (32160037, 32060033). The Science and Technology Plan Project of Guizhou (QKHJC-ZK[2024]ZD071).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.X. , Q.X. and F.L. designed the study. Y.X. wrote the paper. L.L., C.H., T.H. S.R. and X.W. participated in experiments.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical approval

All mouse studies were carried out under standard conditions and in accordance with Zunyi Medical University Animal Care Committee (ZMU21-2305-003) guidelines. This study protocol was approved by Zunyi Medical University Animal Care Committee.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, Y., Li, L., Han, C. et al. Chlorogenic acid inhibits Pseudomonas toxin pyocyanin and activates mitochondrial UPR to protect host against pathogen infection. Sci Rep 15, 5508 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90255-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90255-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Ginkgolide a enhances the resistance to pathogen infection through mitochondrial unfolded protein response

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2025)