Abstract

Pain is a common and complex non-motor symptom in people with Parkinson’s disease (PWP). Little is known about the genetic drivers of pain in PWP, and progress in its study has been challenging. Here, we conducted two genome-wide association studies (GWAS) to identify genetic variants associated with pain experienced during the earliest stages of Parkinson’s disease. The study population consisted of 4,159 PWP of European ancestry who were mapped to five previously-described, longitudinal pain trajectories. In the first GWAS, the extreme pain trajectories (highest burden versus no significant pain over time) were compared, and in the second GWAS, a multinomial approach was undertaken. While no variant reached genome-wide significance, we identified promising associations, such as rs117108018 (ORGWAS−Extreme=8.96, pGWAS−Extreme=2.5 × 10− 7), a brain/nerve eQTL for L3MBTL3 and EPB41L2, and rs61881484 (pGWAS−Multinomial=2 × 10− 7), which intersects a transcription factor peak targeting CREB1, critical in sensory neuron synaptic plasticity and neuropathic pain regulation. Gene-based tests implicated CTNNB1 (pGWAS−Extreme=3.2 × 10− 5), KLK7 (pGWAS−Extreme=7 × 10− 5), and SLITRK3 (pGWAS−Multinomial=3.2 × 10− 5), which have been associated with neurodevelopment. At the pathway-level, there was an enrichment for genes involved in neurotransmitter regulation and opioid dependence. This study implicates neuropathic pain mechanisms as prominent drivers of elevated pain in PWP, suggests potential therapeutic genetic targets for further research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most prevalent neurodegenerative disease, and pain is a common non-motor symptom that may affect 60–80% of people with Parkinson’s disease (PWP)1,2,3,4. Pain has a significant impact on quality of life in PWP, and it has been associated with poorer mental health, and sleep and mood disturbances4,5. While higher levels of pain are commonly indicated among PWP with advanced disease, PWP may also experience pain during the earliest stages of the disease6,7. To add complexity, pain in PWP demonstrates significant heterogeneity3,8, and may encapsulate akathisia, dystonia, musculoskeletal pain, neuropathic pain, and primary/central pain that likely vary in severity and intensity as PD progresses2,4,9,10. The complex etiology, underdiagnosis, and unsystematic treatment of pain among PWP emphasizes the need to better understand the underlying biological mechanisms, with the goal of identifying therapeutic targets for improved pain management11.

Genetic variation plays a prominent role in PD risk, alongside environmental risk factors12. Over the last two decades, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have boosted our understanding of the genetic basis of PD, with the identification of ~ 90 genetic risk variants13 and prioritization of over 200 genes14. There have been three modestly-sized genetic studies (Ns < 1,350) that explored cross-sectional definitions of pain in PWP, and collectively their initial findings suggest that genetic variation influences the manifestation of pain in PD15,16,17. It is difficult to draw robust conclusions from these studies as two focused on candidate genes while one was a GWAS, and their study populations had different continental ancestries (Israel, Taiwan, United Kingdom). But more importantly, their operational definitions of pain were based on different cross-sectional measures. Considering the observed heterogeneity in the severity and accrual of pain in PWP, a genetic investigation of pain should ideally investigate relationships with longitudinal symptom patterns that best reflect an individual’s perception of pain over time. However, such longitudinal data are rare. Patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments of pain, which are based on the person’s self-report of pain severity, have been shown to be reliable and highly correlated with clinical and observational assessments of pain, even among individuals with cognitive impairment18,19,20. Generic health-related quality of life instruments, such as the short European Quality of Life (EuroQol) 5 Dimension 5 Level (EQ-5D-5 L) instrument, include a scale for experiences with pain and discomfort and have the added advantage of feasibility for large-scale epidemiologic collection of longitudinal data from PWP.

Here, we leveraged the EQ-5D-5 L pain and discomfort instrument and genome-wide data available in 4,159 PWP to identify the genetic determinants of longitudinal pain trajectories in PWP who were early in their disease (\(<3\) years). These longitudinal pain trajectories were derived in our previous work21, where we observed five distinct subgroups of PWP that have similar longitudinal patterns (trajectories) of pain (Supplementary Fig. S1). For the current study, we leverage our prior PWP clusters and performed GWAS comparing: (1) PWP with a severe pain trajectory to those with no significant pain over time (comparison of the extreme trajectories), and (2) all four trajectories of increasing pain to those with no significant pain over time. Single variant tests of association, gene-based tests of associations, pathway enrichment analyses, and other downstream analyses identified suggestive associations as well as associations consistent with known neuropathic and pain-related mechanisms supporting a genetic basis for the heterogeneous pain trajectories observed in and reported by PWP.

Results

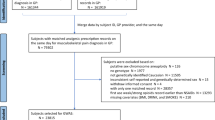

After extensive quality control (QC), the final study population consisted of 4,195 PWP who were within 3 years of onset and assigned to one of five clusters of self-reported pain trajectories, and for whom genetic data were available (Fig. 1). Only 2.3% of PWP were in the severe pain cluster (Class 5) and 22.5% were in the cluster reporting no pain over time (Class 1). The study population was on average 65 years old, male (54%), and were of European descent (Table 1). Increasing proportions of PWP in clusters with greater pain reported OFF episodes, being on PD medications, having arthritis and memory problems, and greater mobility impairments (Table 1).

Extreme genome-wide association test results

In this GWAS comparing 97 PWP with a severe pain trajectory to 935 PWP with no pain, there was no evidence of genomic inflation (\(\lambda=0.999\), Fig. 2a). While no variant met genome-wide significance (\(p<5\times{10}^{-8}\)), there were 23 promising associations with \(p<5\times{10}^{-6}\) (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Table S1), and there were 7 SNPs with \(p<2\times{10}^{-6}\) (Table 2; Supplementary Fig. S5). Associations persisted when adjusting for self-reported arthritis or mobility impairment (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). The most significant variant, an intergenic variant rs117108018 on chromosome 6, had an exceptionally strong association (\(OR=8.96\), \(p=2.54\times{10}^{-7}\)). This variant maps to a DNase peak and it is 12 kilobases (kb) upstream of Y_RNA, which encodes a small non-coding RNA molecule that is highly expressed dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and tibial nerve22. It is also an eQTL (\(p<0.005\)) for L3MBTL3 and EPB41L2 in the amygdala and cerebellum brain tissues, respectively (Supplementary Table S4). Suggestive associations also included MAPK8 (rs72794357, \(OR=4.61\), \(p=1.2\times{10}^{-6}\)) and VLDLR (rs4741753, \(OR=2.24\), \(p=1.2\times{10}^{-6}\)) variants, which appear to be eQTLs of their respective genes in brain and tibial nerve tissues. We interrogated LDlink for variants in LD with promising associations (\(p<5\times{10}^{-6}\)), and there was strong LD between a few of these variants and variants significantly associated with other pain-related traits: shoulder impingement syndrome (rs74821598, \({r}^{2}=0.80\)), and sensory perception (rs75941298, \({r}^{2}=0.86\)) (Supplementary Table S5). In addition, these 7 variants associated with severe pain in PWP are eQTLs for several genes in the brain/nerve tissues (\(p<0.05\)) (Supplementary Table S4).

Manhattan and quantile-quantile plots for the GWAS of extreme trajectories (a) and the multinomial GWAS of all five trajectories (b) Manhattan and quantile-quantile (Q–Q) plots of the results from the genome-wide association studies (GWAS) comparing (a) the two most extreme clusters, which correspond to the least and most impaired groups of persons with Parkinson’s disease, and (b) all five clusters identified from the longitudinal trajectories of patient-reported pain. Both sets of association tests adjusted for age, sex, and the first three multidimensional scaling (MDS) components. The Manhattan plots show \(-log10(p-value)\) on the y-axis and the chromosomal position of each genetic variant on the x-axis, with a dashed horizontal line indicating suggestive significance of \(2\times{10}^{-6}\). In the Q–Q plots, the observed versus expected p-values from the corresponding GWAS were plotted on the \(-log10\) scale. The observed genetic inflation factor was (a) \({\lambda}_{GC}=0.999\) for extreme cluster GWAS, and (b) \({\lambda}_{GC}=1.0409\) for the all cluster GWAS.

Multinomial genome-wide association test results

There was no evidence of genomic inflation in the multinomial GWAS for pain (\(\lambda=1.04\), Fig. 2b). Similar to the extreme GWAS, we did not observe genome-wide significant associations but there were 6 promising associations with \(p<2\times{10}^{-6}\) (Table 3; Supplementary Fig. S6; expansive associations [\(p<0.001\)] are in Supplementary Table S6). Results were unchanged when adjusting for self-reported arthritis or mobility impairment (Supplementary Tables S7 and S8). An intergenic variant (rs61881484) on chromosome 11 less than 2.5 kb upstream of LDLRAD3 had the most significant association (\(p=2\times{10}^{-7}\)). It is also a brain tissue eQTL of several genes (\(p<0.05\); Supplementary Table S9), including: LDLRAD3, FJX1, COMMD9, TRAF6, PRR5L, and PAMR1. We also identified suggestive genic associations, such as SLCO2A1 (rs7653639, \(p=1.5\times{10}^{-6}\)) and RYK (rs9839609, \(p<1.7\times{10}^{-6}\); rs9865808, \(p=1.94\times{10}^{-6}\)) (Table 3). Evidence suggests that the two RYK variants are eQTLs for this gene in brain and tibial nerve tissues (Supplementary Table S9).

Gene-bases test results

The gene-based tests involving 18,727 and 18,736 mapped genes for the extreme and multinomial GWAS, respectively, did not reveal associations at a genome-wide significance threshold (defined as p = 0.05/total number of mapped genes). The most significant findings were CTNNB1 (\(p=3.2\times{10}^{-5}\)) and KLK7 (\(p=7\times{10}^{-5}\)) for the extreme GWAS (Supplementary Table S10), and SLITRK3 (\(p=3.2\times{10}^{-5}\)) and LDLRAD3 (\(p=1.5\times{10}^{-4}\)) for the multinomial GWAS (Supplementary Table S11). Several of these most significant gene-based test candidates were also implicated in Parkinson’s disease, neurodevelopment, and migraine, such as MYLK2, which encompasses an intronic variant rs6060983 associated with PD23, and FBN2 that underlies suggestive association for migraine susceptibility24 (Supplementary Tables S10 and S11).

Pathway enrichment analysis

The pathway enrichment analysis was also applied to a total of 314 and 247 genes for the two sets of GWAS, as the union of SNP-based and gene-based annotations (Supplementary Tables S12 and S13). Several pathways relevant to the regulation of the neurotransmitter and opioid dependence were enriched in our results (Tables 4 and 5). For example, in extreme GWAS, multiple significant synapse-related pathways were implicated, including KEGG25,26: serotonergic synapse (\(p=1.17\times{10}^{-5}\)), dopaminergic synapse (\(p=4.54\times{10}^{-5}\)), and glutamatergic synapse (\(p=7.91\times{10}^{-5}\)); opioid signaling, including Reactome: opioid signaling R-HSA-111,885 (\(p=4.71\times{10}^{-4}\)). As for the multinomial GWAS, there was enrichment of synapses regulation and opioid dependence pathways, including KEGG: morphine addiction (\(p=1.70\times{10}^{-5}\)) and retrograde endocannabinoid signaling (\(p=5.16\times{10}^{-4}\)).

Other noteworthy genetic associations

In addition to the single SNP and gene-based discovery efforts described above, we also sought to map previously reported associations to the results of the two GWAS performed here for pain among PWP. To do this, we queried the GWAS Catalog (as of April 2023) for SNPs associated at p-value threshold\({10}^{-5}\) with (1) PD risk (526 variants), (2) neuropathic pain (30 variants), (3) chronic pain (146 variants), and (4) response to opioids (50 variants) for lookup in our results of the extreme and multinomial GWAS. In relation to PD risk, 438 of 526 variants were tested in our GWAS, and 11% had marginal associations in the extreme GWAS, including multiple variants within the alpha-synuclein encoding gene, SCNA (\(p<0.05\); Supplementary Table S14). Interestingly, there was little evidence of overlap between association for 25 of 30 variants associated with neuropathic pain with findings from the currents analyses (Supplementary Table S15), but a handful of associations were evident amongst 118 of 146 variants associated with chronic pain (Supplementary Table S16) including GABRB2-rs1946247 (\(p=5\times{10}^{-8}\), \(\beta=0.019\))27, which was marginally significant in both the extreme (\(p=2.94\times{10}^{-4}\)) and multinomial GWAS (\(p=6.53\times{10}^{-5}\)). In the final comparison, 29 of 50 variants associated with response to opioids and while only 3 variants were associated with extreme pain in PWP (\(p<0.05\); Supplementary Table S17), they implicate putative therapeutic targets. For example, rs61355450C and rs11692586G was associated with higher extreme pain in PWP (\(OR=2.39\) and \(1.43\)) and also with higher opioid analgesic requirements in the treatment of cancer pain28. A variant associated with improved buprenorphine treatment response29, rs7205113T, had a protective association here with extreme pain in PWP (\(\text{OR}=0.52\)).

Discussion

We report here a large genome-wide association of longitudinal patient-reported pain trajectories for 4,159 PWP recruited by Fox Insight30. In this study, we identified several genetic variants with suggestive significance from two GWAS analyses: (1) a GWAS of the severe pain over time to no experiences of pain over time and (2) a multinomial GWAS comparing four trajectories of increasing pain to no experiences of pain over time. In brief, the results implicate multiple neuropathic pain processes, a possible relationship with dystonia, and synaptic dysfunction as prominent drivers of pain in PD.

Pain is a common non-motor symptom among PWP; however, there has only been one prior GWAS targeting pain in PD. The prior GWAS compared 898 PWP reporting high pain compared with 420 PWP reporting no/low pain who were participants in the UK Parkinson’s Pain Study28,29. Participants were classified based on their one-point-in-time response to the McGill Pain Questionnaire and the Visual analog scale regarding pain in the past month, and the GWAS identified two strongly correlated TRPM8 variants (rs11563208 [\(OR=1.8\)] and rs12465950 [\(OR=1.7\)]; \({r}^{2}=0.85\)) associated at genome-wide significance with pain in PD30,31. However, in the present study there was no evidence for any association for either SNP in either GWAS (rs11563208: \({OR}_{\text{GWAS}-\text{Extreme}}=1.14\), \({p}_{\text{GWAS}-\text{Extreme}}=0.44\) and \({p}_{\text{GWAS}-\text{M}ultinomial}=0.52\); rs12465950: \({OR}_{\text{GWAS}-\text{Extreme}}=0.99\), \({p}_{\text{GWAS}-\text{Extreme}}=0.97\) and \({p}_{\text{GWAS}-\text{M}ultinomial}=0.83\)), nor was TRPM8 associated at the gene-level (Supplementary Tables S10 and S11). While both studies examined pain in European-descent PWP, the operational definitions of the pain outcomes were substantially different and this alone may explain the differences in associations.

While neither the extreme nor multinomial pain GWAS revealed genome-wide significant associations, the genetic variants that were marginally associated with pain in PD were independent of arthritis and mobility limitations, and implicate genes that appear to be related to relevant biological mechanisms, and therefore suggest promising processes for further investigation. For example, the most significant finding from the extreme pain GWAS (rs1178108018) with a large magnitude of effect (\(OR=9\)) is intergenic and a brain/nerve tissue eQTL for L3MBTL3, which has been associated with multiple sclerosis risk. This variant regulates Notch, and Notch activation is essential for the development of neuropathic pain31,32. Variant rs1178108018 is also a brain/nerve tissue eQTL for EPB41L2, and in mice loss of the encoded membrane skeletal protein results in myelin abnormalities in the peripheral nervous system33. There were also genic MAPK8 and VLDLR variants with suggestive associations in the extreme GWAS that were brain tissue eQTLs for MAPK8 and VLDLR. Implication of MAP kinases is of interest since they may have a role in increasing pain sensitivity34, and MAPK8 may be associated with opioid dependence (\(p=5\times{10}^{-7}\))35. VLDLR is Reelin receptor, and Reelin plays a critical role in neurodevelopment and synaptic plasticity36,37. There were also strong associations (\(OR>3\); \(p=5\times{10}^{-6}\)) for ANO3 variants in the extreme GWAS (Supplementary Table S1), and this gene has been suggestively associated with altered neohesperidin dihydrochalcone taste sensitivity38 (taste impairment is another common non-motor symptom in PD39), cannabis dependence40, and alcohol use disorder41. ANO3 itself is intriguing as mutations within the gene cause monogenic autosomal dominant dystonia (Dystonia-24)42, and upwards of 30% of PWP may also have dystonia43. Lastly, these ANO3 variants are brain tissue eQTLs for BDNF-AS (Supplementary Table S4), which is up-regulated in a mouse model of PD where is may promote apoptosis and autophagy44.

The multinomial pain GWAS also highlighted several other genes that merit further investigation. For example, the most significant finding (rs61881484) intersects a transcription factor peak that targets CREB145, a gene critical in synaptic plasticity in sensory neurons46 and is involved in the regulation of neuropathic pain47. Variant rs61881484 is also a brain tissue eQTL of several genes with varied but relevant functions (e.g. FJX1 which regulates dendritic extensions48, COMMD9 has a critical role in endosomal sorting of Notch family members49 and Notch signaling activation is a key driver of neuropathic pain32, TRAF6 is involved in maintaining neuropathic pain50 and chronic visceral pain51, and PAMR1 is associated with muscular dystrophy and predicted to be associated with migraine pain52,53), further supporting its role as a likely driver of pain in PD. Other suggestive genic (RYK, HDAC7, GFRA1) associations (\(p<5\times{10}^{-6}\)) further implicate a prominent role for neuropathic pain processes in PD. For example RYK-rs9839609 is a brain/nerve tissue eQTL for this gene, which encodes a receptor that actively participates in Wnt signaling pathway known to be essential for neurite outgrowth along with many other neuronal development activities54. In rats, blocking Wnt/Ryk signaling inhibits induction of neuropathic pain without affecting normal pain sensitivity55. HDAC7 and other histone deacetylases may merit closer investigation as HDAC inhibitors were shown to attenuate hypersensitivity in a neuropathic pain rat model56. Lastly, there is evidence that GFRA1, which encodes a GDNF receptor, may play a key role in thermal hyperalgesia in a neuropathic pain rat model57,58.

The gene-based tests and pathway enrichment analyses further highlight likely biological processes relevant for understanding PD pain. In general, genes involved in neurodevelopment and opioid signaling were enriched in these pain GWAS. For example, CTNNB1 is among the most significant gene-based result for both GWAS (\({p}_{\text{GWAS}-\text{Extreme}}=3.2\times{10}^{-5}\); \({p}_{\text{GWAS}-\text{M}ultinomial}=2.7\times{10}^{-4}\)), and its key function includes promoting neurogenesis59. CTNNB1 de novo mutations have been associated with polyneuropathy in lower limbs60. KLK7, a gene with marginal significance in the extreme GWAS (\(p=7\times{10}^{-5}\)) encodes an astrocyte-derived amyloid-β degrading enzyme important for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease61. We also observed genes (e.g. SLITRK3 and LDLRAD3) in the multinomial GWAS involved in neurite outgrowth and modulating amyloid precursor protein function62,63. Moreover, gene-based tests for the extreme GWAS prioritized genes (e.g. MYLK2 and PTK2B) that have been associated with neurodegenerative disorders in prior studies23,64. Noteworthy, the extreme pain GWAS was enriched for pathways relevant to serotonergic, dopaminergic, and glutamatergic synapse signaling. Among the most significantly enriched pathways in the multinomial pain GWAS was morphine addiction, which is intriguing as morphine is an opioid analgesic for managing chronic pain, the long-term use of which could lead to tolerance and severe side effects, including addiction65,66. The “retrograde endocannabinoid signaling” pathway is also of interest as it plays an essential role in modulating the function of both the excitatory and inhibitory synapses67. When comparing the current associations with prior GWAS for general pain or PD risk, none of the genome-wide significant findings in prior GWAS27 for several PD-related outcomes were amongst the most significant findings in the two GWAS reported here. Still, lookups of these prior associations suggest consistent findings with the current results, e.g., GABRB2-rs1946247 is associated with multisite chronic pain65 and it was suggestively associated with PD pain in both GWAS conducted here. Our results also suggest that SCNA, a well-established PD risk locus, may also play a role in PD pain13,68. To recap, these gene-based and enrichment results, and relationships with other phenotypes suggest that future research on the role of synaptic processes in PD and PD pain may lead to promising therapeutic targets for PWP.

The present study has several strengths and limitations. This study is the first GWAS of longitudinal pain trajectories in PWP, and one of the few studies of a longitudinal pain phenotype. In addition to the large sample size, we used two complimentary approaches, a multinomial GWAS and a traditional GWAS of a binary outcome, alongside a comprehensive strategy for investigating pain in PD. While this study was large, statistical power was limited (i.e. there were only 97 PWP in the severe pain trajectory) as we did not identify genome-wide significant associations. This underscores challenges in collecting sufficient data for the subjective and evolving outcome of pain in PWP. Further, the PWP involved in this study were limited to those early in their disease duration (\(<3\) years), which we perceive as a key strength, but pain among PWP increases with disease duration68 and therefore, we may have increased power by examining pain in PWP with longer disease durations (this is an active future direction). The study was also limited to PWP of European ancestry, limiting the generalizability to non-European populations. Also, our longitudinal definitions of pain were based on a readily implemented generic PRO that will allow for comparisons to non-PD population, a perceived strength, and while the findings do implicate relevant biological processes, more granular insights may be gained by using more sensitivity tools that capture various pain sensations. While the study population represents one of the largest patient-driven PD registries, a key limitation is the that it is a convenience sample of volunteers reporting a diagnosis of PD, though a diagnosis of PD was confirmed by clinicians in validation study of 165 participants69. Overall, the framework presented in this study serves as a blueprint for forthcoming research examining the intersection of PROs and genotypic variation, providing a versatile approach with great potential to tackle a broad spectrum of neurological conditions and other complex phenotypes, and demonstrate the potential of PROs for elucidating biological insights.

To summarize, our findings also shed light on likely drivers of pain experienced by PWP, who are early in their disease, through the two GWAS, by leveraging a person-centered approach to modelling a pain PRO and coupling these outcomes with comprehensive genetic data. We identified genetic variants with suggestive significance implicated in pain sensitivity47,55 and regulating neuropathic pain8,69, along with multiple eQTLs associated with neuropathic pain and other pain mechanisms (i.e. synapse signaling), including a potential role for a genetic driver of dystonia. The findings, however, emphasize the significance of processes related to neuropathic pain contributing to pain severity in PWP8,70. Previous research suggests that the pain treatment for PWP mainly comprises nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs70, but the evidence that GABRB2 may also contribute to pain in PWP suggests that possible targets for future research might include anti-convulsants (i.e. gabapentine)71. We also observed tentative relationships for opioid and endocannabinoid related pathways, which suggests other potential therapeutic targets. In general, our findings further fuel a broader discourse on the significance of pain management within the realm of PD and warrants interdisciplinary collaborations from a variety of disciplines to enable a holistic treatment paradigm that addresses both the underlying condition and the intricate pain profiles it gives rise to.

Methods

Study population

This study of de-identified data was deemed non-human subject research by the institutional review boards at Case Western Reserve University and The MetroHealth System, Cleveland, Ohio. These data were provided by participants in Fox Insight (https://foxinsight.michaeljfox.org), an ongoing, virtual, longitudinal study of people aged 18 years and older focused on empowering discovery, validation, and reproducibility in PD PRO research30. We accessed these data through the Fox Insight Data Exploration Network (Fox DEN) on 10/14/2021 (for up-to-date information visit https://foxinsight-info.michaeljfox.org/insight/explore/insight.jsp). Fox Insight includes routine assessment of PRO measures, other health-related data, and environmental exposures, and participants are invited to provide biological samples to be used for generating genome-wide genetic data by 23andMe. Launched in 2015, Fox Insight has enrolled \(>\,54{,}000\) participants, including ~38,000 PWP who are on average 66 years of age, of European descent (96%), and 65% male.

Fox Insight participants are invited to complete routine PD-related self-assessments via an online portal every three months. A telehealth pilot study of a subset of participants confirmed a diagnosis in 95.1% of 167 individuals72. As previously described, we applied latent class growth analysis71, a data-driven mixture model approach, to longitudinal data for EQ-5D-5 L pain/discomfort item (5 level Likert scale where 0 = no pain or discomfort and 4 = extreme pain or discomfort) available in 8,612 PWP early in their disease course (\(<3\) years)72. We identified five distinct clusters of PWP will similar pain trajectories over time (Supplementary Fig. S1)73. The five clusters were used in the subsequent genetic analyses as our outcomes of interest. Detailed genetic data were generated from saliva samples of PWP participating in genetic sub-study, which underwent detailed quality control assessment and genetic imputation (Supplementary Methods).

Two sets of association tests

We performed GWAS to compare the clusters identified from the longitudinal trajectories of patient-reported pain (Fig. 1): (1) a logistic GWAS that compared the two most extreme clusters (Supplementary Fig. S1), Class 1 (no pain) and Class 5 (severe pain) using PLINK1.9, which correspond to the least and most impaired groups of PWP, respectively, and aimed to identify genetic variations associated with extreme pain among PWP, and (2) a multinomial GWAS that individually compared Classes 2–5 to Class 1 using the frequentist multinomial logistic regression approach implemented in Trinculo74. All analyses were adjusted for age, sex, the first three MDS components, and the genotyping arrays. To characterize the associations identified in our GWAS, we utilized the NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog75, a comprehensive database of published GWAS findings, along with RegulomeDB76, FIVEx77, LDlink78, and Bgee79, the web-based tools to explore the functional potential, expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL), and linkage disequilibrium (LD) patterns.

We also performed several gene-related analyses for protein-coding genes using MAGMA v1.680 embedded in FUMA 1.5.381. In brief, the summary statistics from each GWAS were used to perform the gene-based test, gene-set analyses, and tissue expression analysis. A Bonferroni correction was used to determine genome-wide significance for these gene-based analyses.

Enrichment analysis

For each GWAS, we annotated SNPs using SeattleSeq Annotation 13882,83. Unique genes were selected using the p-value threshold of 10− 4, resulting in 142 and 110 genes for the extreme and multinomial GWAS, respectively. We also generated additional gene annotation subsets based on the MAGMA gene-based tests described above. The genes were selected using a gene-based test p-value threshold of 0.01, resulting in 192 and 154 genes for the two analyses. Per GWAS, gene sets were combined to create the final gene list, resulting in 314 and 247 genes for the extreme and multinomial GWAS, respectively. We employed Enrichr80,81, an efficient gene set enrichment analysis tool with the interactive web server, to perform the pathway enrichment analysis.

Data availability

The Fox Insight Study data are available to others through the Fox DEN (https://foxden.michaeljfox.org/). The data used in this study is available from the authors to qualified researchers with Fox Insight Data Use approval (https: //foxden.michaeljfox.org/insight/register/). The data produced by this study are avaiable from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The Fox Insight Study data are available to others through the Fox DEN (https://foxden.michaeljfox.org/). The data used in this study is available from the authors to qualified researchers with Fox Insight Data Use approval (https://foxden.michaeljfox.org/insight/register/). The data produced by this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Nègre-Pagès, L. et al. Chronic pain in Parkinson’s disease: The cross-sectional French DoPaMiP survey. Mov. Disord.. 23, 1361–1369 (2008).

Beiske, A. G., Loge, J. H., Rønningen, A. & Svensson, E. Pain in Parkinson’s disease: Prevalence and characteristics. Pain141, 173–177 (2009).

Ford, B. Pain in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord.. 25 (Suppl 1), S98–103 (2010).

Rana, A. Q., Kabir, A., Jesudasan, M., Siddiqui, I. & Khondker, S. Pain in Parkinson’s disease: Analysis and literature review. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg.115, 2313–2317 (2013).

Roh, J. H. et al. The relationship of pain and health-related quality of life in Korean patients with Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neurol. Scand.119, 397–403 (2009).

Politis, M. et al. Parkinson’s disease symptoms: The patient’s perspective. Mov. Disord.. 25, 1646–1651 (2010).

Tai, Y. C. & Lin, C. H. An overview of pain in Parkinson’s disease. Clin. Park Relat. Disord.. 2, 1–8 (2020).

Wasner, G. & Deuschl, G. Pains in Parkinson disease–many syndromes under one umbrella. Nat. Rev. Neurol.8, 284–294 (2012).

Storch, A. et al. Nonmotor fluctuations in Parkinson disease: Severity and correlation with motor complications. Neurology80, 800–809 (2013).

Skogar, O. & Lokk, J. Pain management in patients with Parkinson’s disease: Challenges and solutions. J. Multidiscip. Healthc.9, 469–479 (2016).

Antonini, A. et al. Pain in Parkinson’s disease: Facts and uncertainties. Eur. J. Neurol.25, 917–e69 (2018).

Lesage, S. & Brice, A. Parkinson’s disease: From monogenic forms to genetic susceptibility factors. Hum. Mol. Genet.18, R48–59 (2009).

Nalls, M. A. et al. Identification of novel risk loci, causal insights, and heritable risk for Parkinson’s disease: A meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Lancet Neurol.18, 1091–1102 (2019).

Buniello, A. et al. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS catalog of published genome-wide association studies, targeted arrays and summary statistics 2019. Nucl. Acids Res.47, D1005–D1012 (2019).

Williams, N. M. et al. Genome-wide association study of pain in Parkinson’s disease implicates TRPM8 as a risk factor. Mov. Disord.. 35, 705–707 (2020).

Lin, C. H. et al. Depression and Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) genetic variants are associated with pain in Parkinson’s disease. Sci. Rep.7, 6306 (2017).

Greenbaum, L. et al. Contribution of genetic variants to pain susceptibility in Parkinson disease. Eur. J. Pain. 16, 1243–1250 (2012).

Pautex, S., Herrmann, F. R., Michon, A., Giannakopoulos, P. & Gold, G. Psychometric properties of the Doloplus-2 observational pain assessment scale and comparison to self-assessment in hospitalized elderly. Clin. J. Pain. 23, 774–779 (2007).

Pautex, S. et al. Pain in severe dementia: Self-assessment or observational scales? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc.54, 1040–1045 (2006).

Stolee, P. et al. Instruments for the assessment of pain in older persons with cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc.53, 319–326 (2005).

Gunzler, D. D., Gunzler, S. A. & Briggs, F. B. Heterogeneous pain trajectories in persons with Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord.. 102, 42–50 (2022).

Seminowicz, D. A. & Moayedi, M. The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in acute and chronic pain. J. Pain. 18, 1027–1035 (2017).

Smeland, O. B. et al. Genome-wide association analysis of Parkinson’s disease and schizophrenia reveals shared genetic architecture and identifies novel risk loci. Biol. Psychiatry. 89, 227–235 (2021).

Anttila, V. et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies new susceptibility loci for migraine. Nat. Genet.45, 912–917 (2013).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucl. Acids Res.28, 27–30 (2000).

Kanehisa, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M., Furumichi, M. & Tanabe, M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucl. Acids Res.44, D457–D462 (2016).

Johnston, K. J. A. et al. Genome-wide association study of multisite chronic pain in UK Biobank. PLoS Genet.15, e1008164 (2019).

Nishizawa, D. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies candidate loci associated with opioid analgesic requirements in the treatment of cancer pain. Cancers (Basel). 14(19), 4692. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14194692 (2022). PMID: 36230616; PMCID: PMC9564079.

Crist, R. C. et al. Analysis of genetic and clinical factors associated with buprenorphine response. Drug Alcohol. Depend.227, 109013 (2021).

Smolensky, L. et al. Fox Insight collects online, longitudinal patient-reported outcomes and genetic data on Parkinson’s disease. Sci. Data. 7, 67 (2020).

Alcina, A. et al. Identification of the genetic mechanism that associates L3MBTL3 to multiple sclerosis. Hum. Mol. Genet.31, 2155–2163 (2022).

Xie, K. et al. Notch signaling activation is critical to the development of neuropathic pain. BMC Anesthesiol. 15, 41 (2015).

Saitoh, Y. et al. Deficiency of a membrane skeletal protein, 4.1G, results in myelin abnormalities in the peripheral nervous system. Histochem. Cell. Biol.148, 597–606 (2017).

Ji, R.-R., et al. MAP kinase and pain. Brain Res. Rev.60, 135–148 (2009).

Sherva, R. et al. Genome-wide association study of phenotypes measuring progression from first cocaine or opioid use to dependence reveals novel risk genes. Explor. Med.2, 60–73 (2021).

Bock, H. H. & May, P. Canonical and non-canonical reelin signaling. Front. Cell. Neurosci.10, 166 (2016).

Jossin, Y. Reelin functions, mechanisms of action and signaling pathways during brain development and maturation. Biomolecules 10(6), a009175. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a009175 (2020). PMID: 24370848; PMCID: PMC3941236.

Hwang, L. D. et al. New insight into human sweet taste: a genome-wide association study of the perception and intake of sweet substances. Am. J. Clin. Nutr.109, 1724–1737 (2019).

Shah, M. et al. Abnormality of taste and smell in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 15, 232–237 (2009).

Agrawal, A. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a novel locus for cannabis dependence. Mol. Psychiatry. 23, 1293–1302 (2018).

Dao, C. et al. The impact of removing former drinkers from genome-wide association studies of AUDIT-C. Addiction116, 3044–3054 (2021).

Stamelou, M. et al. The phenotypic spectrum of DYT24 due to ANO3 mutations. Mov. Disord.. 29, 928–934 (2014).

Shetty, A. S., Bhatia, K. P. & Lang, A. E. Dystonia and Parkinson’s disease: What is the relationship? Neurobiol. Dis.132, 104462 (2019).

Fan, Y., Zhao, X., Lu, K. & Cheng, G. LncRNA BDNF-AS promotes autophagy and apoptosis in MPTP-induced Parkinson’s disease via ablating microRNA-125b-5p. Brain Res. Bull.157, 119–127 (2020).

ENCODE Project Consortium. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature489, 57–74 (2012).

Bartsch, D., Casadio, A., Karl, K. A., Serodio, P. & Kandel, E. R. CREB1 encodes a nuclear activator, a repressor, and a cytoplasmic modulator that form a regulatory unit critical for long-term facilitation. Cell95, 211–223 (1998).

Tao, T. et al. Modulating cAMP responsive element binding protein 1 attenuates functional and behavioural deficits in rat model of neuropathic pain. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci.23, 2602–2611 (2019).

Probst, B., Rock, R., Gessler, M., Vortkamp, A. & Püschel, A. W. The rodent four-jointed ortholog Fjx1 regulates dendrite extension. Dev. Biol.312, 461–470 (2007).

Li, H. et al. Endosomal sorting of notch receptors through COMMD9-dependent pathways modulates notch signaling. J. Cell. Biol.211, 605–617 (2015).

Lu, Y. et al. TRAF6 upregulation in spinal astrocytes maintains neuropathic pain by integrating TNF-α and IL-1β signaling. Pain155, 2618–2629 (2014).

Weng, R. X. et al. Targeting spinal TRAF6 expression attenuates chronic visceral pain in adult rats with neonatal colonic inflammation. Mol. Pain. 16, 1744806920918059 (2020).

Jeon, M., Jagodnik, K. M., Kropiwnicki, E. & Stein, D. J. Ma’ayan, A. Prioritizing Pain-Associated targets with machine learning. Biochemistry60, 1430–1446 (2021).

Nakayama, Y. et al. Cloning of cDNA encoding a regeneration-associated muscle protease whose expression is attenuated in cell lines derived from Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients. Am. J. Pathol.164, 1773–1782 (2004).

Green, J., Nusse, R. & van Amerongen, R. The role of Ryk and Ror receptor tyrosine kinases in wnt signal transduction. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol. 6(2), a009175. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a009175 (2014). PMID: 24370848; PMCID: PMC3941236.

Liu, S. et al. Wnt/Ryk signaling contributes to neuropathic pain by regulating sensory neuron excitability and spinal synaptic plasticity in rats. Pain156, 2572–2584 (2015).

Denk, F. et al. HDAC inhibitors attenuate the development of hypersensitivity in models of neuropathic pain. Pain154, 1668–1679 (2013).

Dong, Z. Q., Ma, F., Xie, H., Wang, Y. Q. & Wu, G. C. Down-regulation of GFRalpha-1 expression by antisense oligodeoxynucleotide attenuates electroacupuncture analgesia on heat hyperalgesia in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Brain Res. Bull.69, 30–36 (2006).

Dong, Z. Q., Wang, Y. Q., Ma, F., Xie, H. & Wu, G. C. Down-regulation of GFRalpha-1 expression by antisense oligodeoxynucleotide aggravates thermal hyperalgesia in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Neuropharmacology50, 393–403 (2006).

Kuwabara, T. et al. Wnt-mediated activation of NeuroD1 and retro-elements during adult neurogenesis. Nat. Neurosci.12, 1097–1105 (2009).

Spagnoli, C. et al. Novel CTNNB1 variant leading to neurodevelopmental disorder with spastic diplegia and visual defects plus peripheral neuropathy: A case report. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 188, 3118–3120 (2022).

Kidana, K. et al. Loss of kallikrein-related peptidase 7 exacerbates amyloid pathology in Alzheimer’s disease model mice. EMBO Mol. Med.10(3), e8184. https://doi.org/10.15252/emmm.201708184 (2018). PMID: 29311134; PMCID: PMC5840542.

Aruga, J. & Mikoshiba, K. Identification and characterization of Slitrk, a novel neuronal transmembrane protein family controlling neurite outgrowth. Mol. Cell. Neurosci.24, 117–129 (2003).

Ranganathan, S. et al. LRAD3, a novel low-density lipoprotein receptor family member that modulates amyloid precursor protein trafficking. J. Neurosci.31, 10836–10846 (2011).

Bellenguez, C. et al. New insights into the genetic etiology of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Nat. Genet.54, 412–436 (2022).

Mercadante, S. Problems of long-term spinal opioid treatment in advanced cancer patients. Pain79, 1–13 (1999).

Ballantyne, J. C. & LaForge, S. K. Opioid dependence and addiction during opioid treatment of chronic pain. Pain129, 235–255 (2007).

Castillo, P. E., Younts, T. J., Chávez, A. E. & Hashimotodani, Y. Endocannabinoid signaling and synaptic function. Neuron76, 70–81 (2012).

Chang, D. et al. A meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies 17 new Parkinson’s disease risk loci. Nat. Genet.49, 1511–1516 (2017).

Myers, T. L. et al. Video-based Parkinson’s disease assessments in a nationwide cohort of Fox Insight participants. Clin. Park Relat. Disord. 4, 100094 (2021).

Buhmann, C. et al. Pain in Parkinson disease: A cross-sectional survey of its prevalence, specifics, and therapy. J. Neurol.264, 758–769 (2017).

Quintero, J. E., Dooley, D. J., Pomerleau, F., Huettl, P. & Gerhardt, G. A. Amperometric measurement of glutamate release modulation by gabapentin and pregabalin in rat neocortical slices: Role of voltage-sensitive Ca2 + α2δ-1 subunit. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther.338, 240–245 (2011).

Jung, T. & Wickrama, K. A. An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass. 2, 302–317 (2008).

Jostins, L., & McVean, G. Trinculo: Bayesian and frequentist multinomial logistic regression for genome-wide association studies of multi-category phenotypes. Bioinformatics32, 1898–1900 (2016).

Sollis, E. et al. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS catalog: Knowledgebase and deposition resource. Nucl. Acids Res.51, D977–D985 (2023).

Boyle, A. P. et al. Annotation of functional variation in personal genomes using RegulomeDB. Genome Res.22, 1790–1797 (2012).

Kwong, A. et al. FIVEx: An interactive eQTL browser across public datasets. Bioinformatics38, 559–561 (2022).

Machiela, M. J. & Chanock, S. J. LDlink: A web-based application for exploring population-specific haplotype structure and linking correlated alleles of possible functional variants. Bioinformatics31, 3555–3557 (2015).

Bastian, F. B. et al. The Bgee suite: Integrated curated expression atlas and comparative transcriptomics in animals. Nucl. Acids Res.49, D831–D847 (2021).

de Leeuw, C. A., Mooij, J. M., Heskes, T. & Posthuma, D. MAGMA: generalized gene-set analysis of GWAS data. PLoS Comput. Biol.11, e1004219 (2015).

Watanabe, K., Taskesen, E., van Bochoven, A. & Posthuma, D. Functional mapping and annotation of genetic associations with FUMA. Nat. Commun.8, 1826 (2017).

Ng, S. B. et al. Targeted capture and massively parallel sequencing of 12 human exomes. Nature461, 272–276 (2009).

Chen, E. Y. et al. Enrichr: interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinform.14, 128 (2013).

Xie, Z. et al. Gene Set Knowledge Discovery with Enrichr. Curr. Protoc.1, e90 (2021).

Acknowledgements

All authors contributed to study conception and review of the manuscript. SL, DCC, and FBSB designed, interpreted results, and drafted the manuscript. SL led all analyses. SL, DDG, SAG, and FBSB were supported by funding from The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research MJFF-020155. DCC was supported by institutional funds from the CWRU Cleveland Institute for Computational Biology and by the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland UL1TR000439 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The funding agreement ensured the authors’ independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report. The Fox Insight Study (FI) is funded by The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. We would like to thank the Parkinson’s community and 23andMe research participants and employees for making this research possible.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: SL, DCC, FBSB; Methodology: SL, DCC, DDG, SAG, FBSB; Formal Analysis: SL; Writing – Original Draft Preparation: SL, DCC, FBSB; Writing – Review and Editing: SAG, DDG; Visualization – SL. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent

Participants in the Fox Insight provided informed consent and the study protocol was reviewed by the New England Institutional Review Board (IRB# 120160179, Legacy IRB# 14–236, Sponsor Protocol Number: 1, Study Title: Fox Insight)28. The current secondary data analysis was deemed non-human subjects by the IRB at Case Western Reserve University (#STUDY20210700). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, S., Gunzler, D.D., Gunzler, S.A. et al. Exploring the early drivers of pain in Parkinson’s disease. Sci Rep 15, 6212 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90678-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90678-w