Abstract

Ips (Curculionidae: Scolytinae) bark beetles (BBs) are ecologically and economically devastating coniferous pests in the Northern Hemisphere. Although the microbial diversity associated with these beetles has been well studied, mechanisms of community assembly and the functional roles of key microbes remain poorly understood. This study investigates the microbial community structures and functions in both intestinal and non-intestinal environments of five Ips BBs using a metagenomic approach. The findings reveal similar microbial community compositions, though the α-diversity of dominant taxa differs between intestinal and non-intestinal environments due to the variability in bark beetle species, host trees, and habitats. Intestinal microbial communities are predominantly shaped homogenizing dispersal (HD) and undominated processes (UP), whereas non-intestinal microbial communities are primarily driven by heterogeneous selection (HS). Functional analysis shows that genes and enzymes associated with steroid biosynthesis and oxidative phosphorylation are primarily found in non-intestinal fungal symbionts Ogataea, Wickerhamomyce, Ophiostoma, and Ceratocystis of Ips species. Genes and enzymes involved in degrading terpenoids, phenolic compounds, and polysaccharides are predominately found in the intestinal Acinetobacter, Erwinia, and Serratia. This study provides valuable and in-depth insights into the symbiotic relationships between Ips BBs and their microbial partners, enhancing our understanding of insect-microbe coevolution and suggesting new strategies for pest management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Symbiotic microorganisms significantly influence the physiology, ecology and evolution of their hosts1,2. These microbes which included fungi, bacteria, viruses, archaea, protists, and helminths inhabit both intestinal and non-intestinal samples1,3,4,5,6. High-throughput sequencing (HTS) has been widely used to analyze these microbiomes, uncovering their distribution characteristics and microbial community diversity7,8,9,10. The intestine, as a specific ecological habitat for food intake, storage and digestion in insects, is inhabited by a rich diversity of microorganisms11,12. Microbial community composition varies across insect species. For example, Snodgrassella alvi Kwong and Moran, Gilliamella apicola Kwong and Moran, Lactobacillus, and Bifidobacterium core intestinal microbes in Apis mellifera Linnaeus13; Enterobacter, Serratia, Acinetobacter, and Micrococcus are common in Curculio chinensis Chevrolat14. In bark beetles, core members of the intestinal microbes include yeasts, ophiostomatoid fungi, Pantoea, Pseudomonas, and Rahnella1,15. These intestinal microbes community structures are linked to host diets (e.g., carnivorous versus herbivorous beetles) and the environment (e.g., in the wild versus indoor breeding)16,17. Intestinal microbes play various roles in maintaining host insect health18, and protecting the host from pathogens13. It can provide nutrients to host by degrading complex compounds such as lignocellulose, cellulose, and pectin19,20. These microbes can also detoxify plant defense compounds (terpenes, alkaloids, and phenols), providing nutrients21,22,23.

Non-intestinal tissues such as the cuticle, oral cavity, antennal segments, and glandular reservoirs serve as important microbial habitats. The cuticle, in particular, is a major structure for inhabiting microorganisms1,3. For example, BBs carry various fungi on their exoskeleton or in specialized structures like mycetangia24. Studies have shown that some common crucial microbial taxa are harbored in the non-intestinal samples25,26. These fungal symbionts synthesize sterols, fatty acids and amino acids critical for the beetle’s growth, development, reproduction, and colonization of BBs27,28,29. Non-intestinal fungal symbionts can also synthesize pheromones to assist bark beetles in accomplishing colonization and population establishment30. Additionally, fungal pathogens harbored in non-intestinal tissues can infect the tunnel31.

Ips (Coleoptera: Scolytinae) BBs primarily feed on the phloem of coniferous trees like Picea, Pinus and Larix, causing catastrophic ecological and economical damage to forestry in the Northern Hemisphere25,32,33. For example, Ips nitidus Eggers damages Picea crassifolia forests on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau32,34. Hauser’s engraver beetle (Ips hauseri Reitter) mainly distributes in mountainous areas of Central Asia and has an important influence on Picea schrenkiana, Picea obovata and Pinus sylvestris35,36. Ips chinensis Kurentzov and Kononov mainly distributes in southern and northern China, which can cause substantial damage to pine forests, such as Pinus koraiensis37. And I. typographus Linnaeus and I. subelongatus Motschulsky have disastrously ecological and economic loss for coniferous forests with the assistance of microbial symbionts38,39,40,41. BBs and microorganisms, serving as a classic symbiosis model, play a pivotal role in augmenting the adaptability to environment, evolutionary strategies and maintaining specific ecological functions24,28. Although microbial composition and diversity are studied in the intestines or non-intestines of multiple BBs, it lacks direct comparison for the microbial community structure in the intestinal and non-intestinal samples of Ips bark beetle species in China.

Additionally, interactions can regulate microbial community structures and multiple functionalities to affect host insects42,43. Bacterial associates can mediate the fungal symbionts Leptographium procerum (W.B. Kendr.) M.J. Wingf. and Ophiostoma minus (Hedgc.) Syd. & P. Syd. to consume D-pinitol before consuming D-glucose in red turpentine beetle larvae44. Studies elucidated that insects can survive in specific environments owing to the driver in microbial community assembly, such as immigration, weak selection, and drift. The community assembly processes are driven by deterministic and stochastic processes45. The former includes environmental and biotic filtering46, the latter includes random birth, death, and dispersal events47. Stochasticity is likely to govern temporal and spatial variation in species richness48. For example, dispersal limitation (DL) and drift governed intestinal microbial community assemblies in flies, beetles, and honeybees42,49. After establishing microbial community, deterministic processes may become important when spatial variation leads to enhanced environmental selection. Microbial community assembly is driven by stochastic to deterministic processes48. However, relative importance of symbiotic microbial community assemblies for BBs are poor, hindering our cognition of symbiosis mechanisms between BBs and their partners. So, exploring the dominant driving forces of microbial community assembly is crucial for understanding the mechanisms underlying biodiversity and maintaining ecological system function48.

In this study, metagenomics was used to investigate the microbial community structure and functional traits in the intestines and non-intestines for five representative Ips BBs in China. The objectives were to: (1) compare fungal and bacterial community composition in the intestines and non-intestines; (2) determine microbial interaction and community assembly mechanism in the intestinal and non-intestinal samples; and (3) explore bacterial and fungal functional genes and enzymes in the intestinal and non-intestinal samples, which are related to sterol synthesis and the degradation of complex compounds. This is the first study to compare intestinal and non-intestinal microbial community structures, revealing distinct driving forces that shape the microbial community assemblies in BBs. Our findings enhance the understanding of insect-microbe coevolution, offering insights into mutualistic mechanisms and novel strategies for pest and disease control.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and processing

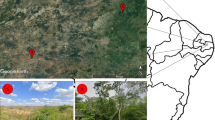

Five Ips BBs were collected from five locations from July 2020 to September 2022 (Fig. 1a; Table 1). Sterile forceps were used to move emerged adults of the second generation from different galleries (Fig. 1b–h), and all samples were stored in 2 mL sterile Eppendorf tubes without surface sterilization. Identification was based on geographical distribution, feeding trees and morphological characteristics38,50. A total of 210 emerged adults of each Ips bark beetle were randomly collected for the same log and divided into three groups. Intestines were extracted according to the methods described by Delalibera et al.51 and Morales-Jiménez et al.52. The remaining tissues were used as non-intestinal samples, resulting in three intestinal and three non-intestinal samples per bark beetle species. A total of 1,050 adults (30 samples) were sampled and stored in a −80 ℃ laboratory ultra-low temperature freezer. The liquid nitrogen quick-freezing method was used to prevent contamination and ensure consistency with the microbial communities in the field environment.

Sampling locations, typical habitats, and selected life stage for Ips BBs. (a) Sampling sites in five locations of China, and the map using QGIS 3.34.13 (https://qgis.org/). (b–d) Symptoms and galleries on spruce infested by I. typographus; (e–h). Frass, eggs, larvae, pupae, and adults of I. hauseri in spruce galleries.

DNA extraction, sequencing, assembly, and annotation

Samples were mixed before DNA extraction, with 500 mg per sample used for total DNA extraction following the CTAB method. DNA quality was evaluated using the Qubit™ dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Invitrogen, Qubit 3.0) and 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. DNA libraries were constructed using the VAHTSR Universal Plus DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina. Sequencing was performed by Beijing Biomarker Biotechnological Company using Illumina NovaSeq6000 (San Diego: NovaSeq 6000 S4 Reagent Kit). Fastp software was used for quality control and filtering of raw reads to acquire high-quality sequencing data53. Bowtie 254 was used to eliminate reads originating from the host, and the aligned reference genomes were Ips nitidus (GenBank accession number: GCA_018691245.2) and I. typographus (GenBank accession number: GCA_016097725.1). Metagenomes were assembled using MEGAHIT55 version 1.1.2 software (https://github.com/voutcn/megahit) after filtering contigs less than 300 bp. Assembly results were evaluated using QUAST56 and genomic coded regions were identified in MetaGeneMark version 3.26 software57. Gene prediction was performed with default parameters, and gene redundancy with 95% similarity and 90% coverage thresholds were determined using MMseq2 version 11- e1a1c58. Finally, 30 metagenomic datasets were uploaded to NCBI to obtain bioproject ID, biosample accessions and Sequence Read Archive (SRA) (Supplementary Table S1).

A non-redundant protein sequence database (NR) was used to annotate the taxonomic identification of the symbiotic microbial communities for five Ips BBs. Subsequently, functional genes and enzymes were annotated using the KEGG database59 (with default parameters e value ≤ 1e − 5) and Carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZy) database. The highest similarity and annotation information of genes were matched to the corresponding KEGG orthologs (KO).

Community composition, alpha- and beta- diversity analysis

Rarefaction curves were used to show the sequencing depth of species and genes for all samples before analyzing microbial community structure. The microbial community compositions of intestinal (ISC, ICC, ITC, IHC and INC) and non-intestinal (IS, IC, IT, IH and IN) samples were analyzed at the phylum, order and genus levels. The relative abundances of the dominant microbes were compared across Ips BBs at different host trees (larch, pine, and spruce). Alpha-diversity (α-diversity) at the genus level were performed using student’s t-test. Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) was calculated with Bray-Curtis’ dissimilarities based on the PERMANOVA test to determine the difference between species and samples. The analyses were performed online using BMKCloud (https://www.biocloud.net/) platforms.

Co-occurrence network analysis

Co-occurrence networks were construct in R version 4.2.2 with “igraph”, “Hmisc”, “ggplot2”, “ggpubr”, and “ggsignif” packages to confirm important interrelationships between intestinal and non-intestinal microbial communities for five Ips BBs. Microbes with an incidence rate below 50% were filtered to obtain clear network interrelationships. Correlations were regarded as statistically significant with r > 0.7 and p < 0.05. Spearman correlation index and Benjamini-Hochberg (FDR-BH) method were applied for statistical testing. The network was exhibited in Gephi version 0.10.1 software60 and microbial interactions were assessed using parameters such as average clustering coefficient, average degree, average path length, network diameter, map density, and average weighted degree.

Community assembly analysis of core taxa

All gene sequences for core taxa were aligned with ClustalW1.661, and ML trees were constructed with 5000 bootstrap replicates using IQ-tree in PhyloSuite version 1.2.362. Core taxa included ophiostomatoid fungi (Ophiostoma, Leptographium, Grosmannia, Esteya, Sporothrix, Ophiostomataceae unclassified, Endoconidiophora, Ceratocystis, Thielaviopsis, and Ceratocystidaceae unclassified), yeast (Schizosaccharomycetales and Saccharomycetales), Enterobacter, Acinetobacter, Serratia, Erwinia, Mycobacterium, and Mycolicibacterium). These microbes play crucial roles in community composition, nutritional provision, and complex compounds degradation63,64. Weighted β-nearest taxon index (βNTI) and β-Raup-Crick metric (RC) dissimilarity were calculated using the “picante” package in “R” to evaluate microbial community assembly processes. The βNTI value > 2 represented heterogeneous selection (HS), while βNTI < -2 indicated homogeneous selection (HOS), both representing deterministic processes. |βNTI| was less than 2, the stochasticity was deemed the main driving force. The RC value greater than 0.95 suggested that community assembly was dominated by dispersal limitation (DL). RC value smaller than − 0.95 indicated that homogenizing dispersal (HD) was the primary driving force. Additionally, |RC| ≤ 0.95 indicated that undominated processes (UP) (drift, diversification, weak selection and weak dispersal) governed the community assembly45,65.

Functional genes and enzymes analysis for microbial communities

The number of fungal and bacterial unigenes was compared in the KEGG enrichment (level 2) analysis. The difference of gene relative abundance was compared among all samples using the complete hierarchical clustering method and Euclidean distance calculation in the KEGG pathway (level 3). Genes and enzymes linked to steroid biosynthesis, polysaccharides, terpenoids and phenolic compounds degradation were annotated. Phenolic-related products were annotated in the KEGG and CAZy databases. These analyses were mainly performed online on GenesCloud (https://www.genescloud.cn) or OmicStudio Cloud (https://www.omicstudio.cn) platforms.

Results

Sequencing of intestinal and non-intestinal samples

Rarefaction curves based on species and genes were close to asymptote in all samples, indicating sufficient sequencing depth for both intestinal and non-intestinal samples (Supplementary Fig. S1a–d). Following filtration, the number of assembled contigs per species ranged from 155,572 to 342,753, with the base largest length of contigs between 9,314 and 52,264. The N50 ranged from 596 to 1,558 bp, the GC content from 32.54 to 35.90%, and the proportion of mapped contigs (assembled contigs / sequenced reads) from 81.94% to 99.65%. The number of predicted functional genes ranged from 48,044 to 138,187, with maximum base length between 3,444 and 9,900 bp (Table 2). In total, 1,106,180 non-redundant genes were obtained, with an average base length of 252 bp and a maximum largest length of 9,900 bp. A total of 113,332 metagenes were assigned to 6,116 KOs, representing 996 fungi and 5,351 bacteria.

Comparison of intestinal and non-intestinal microbial community composition

Results showed a higher relative abundance of Microsporidia in the intestinal samples compared to non-intestinal samples. Non-intestinal samples exhibited slightly higher relative abundances of Ascomycota, Mucoromycota, unclassified group, and Basidiomycota were slightly higher than those of the intestinal samples (Fig. 2a). At the order level, Erysiphales, Mucorales, Saccharomycetales and Pucciniales were more abundant in non-intestinal samples than in the intestinal samples (Fig. 2b). At the genus level, non-intestinal Erysiphe and Puccinia showed slightly higher relative abundances than those in the intestinal samples (Fig. 2c). The relative abundances of Saccharomycetales and Ophiostomatoid fungi were slightly lower in the intestines than those of non-intestines for I. subelongatus and I. chinensis. Conversely, these two groups associated with spruce-feeding beetles were slightly more abundant in the intestinal samples. Additionally, I. nitidus non-intestinal samples showed the higher relative abundance of Saccharomycetales associated with non-intestinal samples from other Ips BBs (Supplementary Table S2).

Intestinal samples showed higher relative abundances of Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Aquificae and Acidobacteria compared to non-intestinal samples (Fig. 2d). At the order level, Enterobacterales, Sphingobacteriales, Rickettsiales, Pseudomonadales, and Bacillales were more prevalent in the intestinal samples than in non-intestinal ones (Fig. 2e). Enterobacter had a higher relative abundance in the intestines of I. subelongatus, I. typographus, I. hauseri and I. nitidus. Piscirickettsia and Wolbachia were more abundant in the intestines of I. chinensis and I. nitidus (Fig. 2f). Acinetobacter and Escherichia were more abundant in the intestines than in the non-intestines of I. hauseri and I. nitidus. Serratia and Erwinia had higher abundance in the intestinal samples of I. chinensis, I. typographus and I. nitidus. Klebsiella, Microbacterium, Rickettsia and Pseudomonas exhibited higher relative abundances in the intestinal tracts of I. chinensis, I. hauseri and I. nitidus compared to the non-intestinal tissues (Supplementary Table S2).

The microbial community diversity was compared between the intestinal and non-intestinal samples of five Ips BBs (Fig. 2g–j). The Shannon index showed highest species diversity in the intestines of I. typographus and I. hauseri for both fungi (ITC: 3.77, IHC: 3.65) and bacteria (ITC: 3.55, IHC:3.62) (Fig. 2g). In non-intestinal samples, the highest diversity was observed in I. nitidus and I. typographus for fungi (IN: 4.24, IT: 3.81) and bacteria (IN: 3.67, IT: 3.52) compared to other three Ips BBs (Fig. 2h, j). Chao1 index indicated greater species richness of associated fungi (IHC: 331.59, ICC: 324.33) and bacteria (IHC: 472.89 and ICC: 513.38) in the intestinal tissues of I. hauseri and I. chinensis (Fig. 2g, i). It had significantly greater species richness for fungal (IS: 354.67, IT: 331.26) and bacterial (IS: 585.39, IT: 490.30) communities in the non-intestinal samples of I. subelongatus and I. typographus than in those of other three Ips BBs (Fig. 2h, j). While fungal diversity associated with I. nitidus non-intestines showed no clear differences among the other four Ips BBs, intestinal fungal and bacterial diversity were notably different from those of I. subelongatus, I. hauseri, and I. chinensis. Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) showed remarkable differences (PERMANOVA R2 = 0.8, p = 0.001) in the fungal (Supplementary Fig. S1e) and bacterial communities (Supplementary Fig. S1f) associated with intestinal and non-intestinal samples of five Ips BBs.

In all cases, although there was similar community composition of symbiotic fungi and bacteria in the intestinal and non-intestinal samples, the relative abundances varied with different taxa from two type samples of Ips BBs. The relative abundances of intestinal fungi were slightly lower than those of non-intestinal samples. In contrast, the relative abundances of intestinal bacteria were slightly higher than those of the non-intestine. Saccharomycetales and Enterobacterales exhibited the higher diversity and relative abundances in the intestines and non-intestines of different Ips BBs. And intestinal and non-intestinal fungi and bacteria with I. typographus had greater species richness and diversity. Microbial community structures were linked to different dietary trees (larch, spruce and pine), host beetles, specific habitats and sampling sites.

Microbial community structure in the intestines and non-intestines of five Ips BBs at different taxonomic levels. (a–c) Fungal community composition and (d–f) bacterial community composition at the phylum, order and genus. (g) α-diversity (Shannon index and Chao1 index) in the intestinal fungal symbionts of every Ips bark beetle based on student’s t-test (*p < 0.05, **0.01 < p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01) at the genus level; (h) α-diversity in the non-intestinal fungal symbionts; (i) α-diversity in the intestinal bacterial associates; (j) α-diversity in the non-intestinal bacterial associates.

Microbial interaction and community assembly processes

Network analysis showed 100% positive connections among the intestinal (fungi: 45.49%, bacteria: 54.51%) (Fig. 3a) and non-intestinal microbes (fungi: 46.48%, bacteria: 53.52%) (Fig. 3b), suggesting the mutualistic interactions between fungi and bacteria associated with five Ips BBs. The results showed that the connectivity of intestinal microbes was tighter than non-intestinal ones. The average degree of intestinal microbes (135.166) was significantly more than twice as large as non-intestinal ones (65.202). Moreover, the number of connections for intestinal microbes (83,938) was remarkably higher than non-intestines (43,066) (Table 3). Additionally, there were significant differences between the intestinal and non-intestinal samples (p = 2.22e-16 < 0.01) (Fig. 3c). In the intestinal microbial network analysis, dominant genera with high interactions included unclassified bacteria (1.69%), Aspergillus (1.29%), Bacillus (1.05%), unclassified Gammaproteobacteria (0.97%), unclassified Bacteroidetes (0.81%), Enterobacter (0.72%), Paenibacillus (0.72%), Pseudomonas (0.64%), unclassified Alphaproteobacteria (0.56%), unclassified Deltaproteobacteria (0.40%), Streptomyces (0.32%), Acinetobacter (0.24%), Pantoea (0.24%), Clostridium (0.24%), Chryseobacterium (0.16%), Microbacterium (0.16%), Serratia (0.08%), Mycolicibacterium (0.08%) and others (89.61%). These dominant genera were harbored in the non-intestines, except for Pantoea and Serratia, which may be notably more significant in the intestinal environment.

Co-occurrence networks and microbial assembly processes of intestinal and non-intestinal fungi and bacteria associated with different Ips BBs. Co-occurrence network analysis of intestinal (a) and non-intestinal (b) fungal and bacterial communities with statistically significant Spearman correlations (r > 0.7, p < 0.05), and the node size representing relative abundances of different species. The higher the average degree, the higher the network complexity. (c) Significant difference of network in the intestinal and non-intestinal tissues for five Ips BBs. (d–g) Community assemblies of crucial microbiomes. “+” representing |βNTI| > 2, deterministic process; “-” representing |βNTI| < 2, stochastic process; “HS” and “HOS” representing heterogeneous and homogeneous selection of deterministic process; “HD” and “DL” representing homogenizing dispersal and dispersal limitation of stochastic process; βNTI > 2 representing HS, βNTI < −2 representing HOS; RC < -0.95 representing HD, RC > 0.95 representing DL, |RC| ≤ 0.95 meaning UD.

The results showed that HD was the primary driving force of all core microbial community assemblies except Mycobacterium in the intestines of I. subelongatus. However, the non-intestinal microbial community assembly of I. subelongatus was more inclined to be driven by HS. Stochastic process (HD, DL and UD) drove the core microbial community assemblies in the intestinal and non-intestinal samples of I. chinensis. HD and UD emerged as dominant drivers governing intestinal microbial community assemblies of I. typographus and I. nitidus. HOS and HS in the non-intestines of I. typographus and HS in the non-intestines of I. nitidus had more relatively greater contributions to the microbial assemblies. HD was the main governing force in the intestinal and non-intestinal samples of I. hauseri (Fig. 3d–g; Table 4; Supplementary Table S3). In sum, stochastic processes (HD and UD) appeared to be entirely dominant driving forces in the intestinal microbial community assemblies of five Ips BBs. However, non-intestinal core microbial community assemblies may be preferentially governed by deterministic processes (HS).

Functional genes annotation for fungal and bacterial communities

In total, 20,459, 25,886 fungal unigenes were annotated in the intestinal and non-intestinal samples (Fig. 4a, b). For bacteria unigenes, 25,550 and 30,677 were annotated in the intestinal and non-intestinal samples (Fig. 4c, d). These genes were subjected to KEGG enrichment analysis and categorized into 22 KEGG pathway level 2, including cellular processes (4 pathways), environmental information processing (2 pathways), genetic information processing (4 pathways) and metabolism (12 pathways). The results revealed that the number of fungal unigenes was significantly higher than bacterial genes in both intestinal and non-intestinal samples for the cell growth and death process (Cell cycle - yeast and Meiosis - yeast). However, intestinal and non-intestinal bacterial unigenes related to xenobiotics biodegradation and metabolism process were more abundant than fungal unigenes in both intestinal and non-intestinal samples. The study revealed 15 pathways involved in this process (Supplementary Table S4), encompassing 45, 44 fungal unigenes in the intestinal and non-intestinal samples, and 245, 487 bacterial unigenes in the intestinal and non-intestinal samples (Fig. 4a–d). These unigenes were primarily distributed in Acinetobacter, Erwinia, Serratia, Mycolicibacterium, Mycobacterium (Supplementary Table S4). Additionally, differential pathways were compared between intestinal and non-intestinal samples of five Ips BBs. No significant differences were observed between intestinal and non-intestinal samples for microbes of I. chinensis. However, significant variations were existed in multiple pathways for symbiotic microbes in the intestinal and non-intestinal samples of the other four Ips BBs. In particular, I. subelongatus and I. hauseri, distinct discrepancies were found in glutathione metabolism (ko00480), basal transcription factors (ko03022), and purine metabolism (ko00230) pathways. The Glycolysis / Gluconeogenesis) pathway (ko00010) also showed significant differences between intestinal and non-intestinal samples for microbes associated with I. nitidus and I. hauseri (Fig. 4e, f).

Fungi and bacteria exhibited the highest gene abundances in the intestinal and non-intestinal samples for energy metabolism, particularly oxidative phosphorylation in the non-intestinal samples with higher gene relative abundance compared to that of intestines (Fig. 5a, b). A total of 1,209 unigenes were annotated as being related to this process, including 300 and 395 fungal unigenes in the intestinal and non-intestinal samples. These fungal unigenes were annotated in Ogataea and Wickerhamomyces (yeasts), Ophiostoma and Ceratocystis (ophiostomatoid fungi), fungi unclassified, Ascomycota unclassified, and other groups (Supplementary Table S5). The most abundant fungal unigenes were found in non-intestines of I. subelongatus (ISC: 58, ICC: 73, ITC: 81, IHC: 85, INC: 89; IS: 150, IC: 74, IT: 110, IH: 83, IN: 85). There were 448 bacterial unigenes in the intestinal samples and 517 bacterial unigenes in the non-intestinal samples. These bacterial unigenes distributed in Microbacterium and Paenarthrobacter (Micrococcales), Macrococcus and Staphylococcus (Bacillales), Erwinia, Erwiniaceae spp., Serratia, Citrobacter, Enterobacter, and Escherichia (Enterobacterales), Acinetobacter and Pseudomonas (Pseudomonadales) and Pseudoxanthomonas (Xanthomonadales). Similarly, the most abundant genes were also found in the non-intestinal samples of I. subelongatus (ISC: 115, ICC: 132, ITC: 131, IHC: 93, INC: 133; IS: 247, IC: 85, IT: 144, IH: 81, IN: 93). It was found that gene relative abundance of dominant fungal (Saccharomycetales and Ophiostomatoid fungi) and bacterial (Enterobacterales and Micrococcales) groups involved in oxidative phosphorylation varied with intestinal and non-intestinal in different Ips BBs (Fig. 5c, d). These taxa may be crucial microbes for energy metabolism.

KEGG enrichment of fungal and bacterial unigenes at KEGG pathway level 2, along with differential pathways in the intestinal and non-intestinal samples of Ips BBs. (a,b) The number of fungal unigenes in the intestinal and non-intestinal samples and (c,d) bacterial unigenes in the intestinal and non-intestinal samples across different KEGG pathways. (e,f) Stamp analysis representing the relative abundances of microbial unigenes at differential pathways in the intestinal and non-intestinal samples of I. subelongatus, I. typographus, I. nitidus and I. hauseri.

Gene relative abundances in different intestinal and non-intestinal symbiotic microbial functional pathways of five Ips BBs. (a) Clustering bar plot of gene relative abundance across KEGG pathways (level 2) in the intestinal and non-intestinal samples of each Ips bark beetle. (b) Gene relative abundance exceeding 0.003% (genes less than 0.003% are not shown) across KEGG pathway (level 3) in the intestinal and non-intestinal samples of every Ips bark beetle. (c,d) Proportion (gene relative abundance of every dominant taxon occupying the abundance all taxa) of dominant fungi and bacteria involved in oxidative phosphorylation in the intestinal and non-intestinal samples of each Ips bark beetle.

Candidate enzymes and unigenes of steroid biosynthesis

Nine enzymes were identified, including four reductases (Delta24-sterol reductase, Delta24 (24(1))-sterol reductase, 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase, and Delta14-sterol reductase), two monooxygenases (calcidiol 1-monooxygenase and methylsterol monooxygenase), one transferase (sterol O-acyltransferase), one lipase (lysosomal acid lipase/cholesteryl ester hydrolase), and one desaturase (sterol 22-desaturase) (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Table S6). There were 55 functional genes involved in the steroid biosynthesis pathway (Ko00100) for this study with 32 fungal unigenes in the intestinal samples and 40 in non-intestinal samples. It exhibited the highest number of fungal unigene in the non-intestinal samples of I. subelongatus (ISC: F: 11, B: 2; ICC: F: 8, B: 2; ITC: F: 14, B: 4; IHC: F: 8, B: 2; INC: F: 4, B: 1; IS: F: 19, B: 3; IC: F: 10, B: 2; IT: F: 15, B: 5; IH: F: 8, B: 2; IN: F: 4, B: 0). These unigenes mainly assigned to Saccharomycetales (unclassified Saccharomycetales, Wickerhamomyces, Candida, Ogataea, Wickerhamiella and Schizosaccharomyces), unclassified fungi, Mucorales and Methylococcales. Additionally, it was found 9 bacterial unigenes in the intestinal samples and 10 in the non-intestinal samples, which mainly distributed in Methylomicrobium, Enhygromyxa, Nannocystis (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Table S6).

Candidate enzymes and genes of terpene and phenolic compounds degradation

Four enzymes were found to degrade limonene (ko00907) (Fig. 6b). A total of 97 related unigenes were found, including 13 fungal and 49 bacterial unigenes in the intestinal samples, 12 fungal and 64 bacterial unigenes in non-intestinal samples. Notably, the non-intestinal samples of I. subelongatus exhibited the most abundant unigenes (ISC: F: 5, B: 6; ICC: F: 4, B: 13; ITC: F: 3, B: 9; IHC: F: 5, B: 3; INC: F: 1, B: 20; IS: F:4, B: 31; IC: F: 4, B: 11; IT: F: 3, B: 9; IH: F: 4, B: 3; IN: F: 1, B: 12) (Supplementary Table S6). These unigenes were primarily associated with Acinetobacter, Erwinia, Serratia for this pathway (Supplementary Table S6).

It was found six enzymes and 14 unigenes related to phenolic compounds degradation (Fig. 6c). These related genes belonged to Acinetobacter (10 genes), Serratia (one gene), Hafnia (one gene), and Mycobacterium (one gene) in the non-intestinal samples of I. subelongatus, and fungal Kuraishia (Saccharomycetales) (one gene) in the intestinal samples of I. nitidus (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Table S6).

Candidate CAZy enzymes and unigenes of polysaccharides degradation

Fifty-five enzymes belonging to 64 families, were identified to be involve in polysaccharides hydrolysis or degradation (Fig. 6d). A total of 8,107 functional genes were identified with 2,578 fungal unigenes in the intestinal samples and 3,111 fungal unigenes in the non-intestinal samples. Bacterial unigenes totaled 2,943 in the intestinal samples and 3,404 in non-intestinal samples (Supplementary Table S7). These unigenes were predominantly associated with unclassified fungi, unclassified Ascomycota, Erwinia, Acinetobacter, Enterobacter, Serratia, etc. The most unigenes were harbored in the non-intestines of I. subelongatus and intestines of I. typographus (Table 5).

Candidate functional enzymes and genes related to steroid biosynthesis, aromatic and phenolic compounds degradation, and polysaccharides degradation annotating in the intestinal and non-intestinal samples of Ips BBs-associated microbes. Gene abundance and related enzymes of steroid biosynthesis (a) and limonene and pinene degradation (b) in the intestinal and non-intestinal samples for Ips BBs. (c) Key chemical reactions and enzymes involved in phenolic compounds degradation. (d) Enzymes involved in the degradation of complex compounds (cellulose, chitin, galactomannan, lignin, pectin, xylan, xyloglucan, starch and sucrose) in the intestinal and non-intestinal samples.

Discussion

This study investigated microbial community structures, interactions, and assembly processes in the intestines and non-intestines of five Ips BBs. The results revealed the abundance of different microbial taxa varied with hosts, dietary trees and specific habitats, despite a general similarity in community composition between intestinal and non-intestinal samples. Mutualistic interactions among intestinal microbes appeared stronger than those of non-intestinal ones. Functional genes and enzymes involved in the steroid biosynthesis and oxidative phosphorylation were predominantly presented in the non-intestinal fungal samples (Saccharomycetales and ophiostomatoid fungi). In contrast, genes and enzymes related to terpenoids, phenol, and polysaccharides degradation were primarily associated with intestinal bacterial samples (Acinetobacter, Erwinia, Enterobacter, and Serratia, etc.). The non-intestinal samples of I. subelongatus exhibited the most abundant unigenes for above processes. Understanding the roles of these microbial communities in nutritional provision and complex compound degradation provides deeper insights into the cooperative mechanisms underlying Ips BBs growth, development, colonization, and metabolism. This study offers valuable insights into the symbiotic relationships between Ips species and their microbial partners.

Comparison of intestinal and non-intestinal microbial community structures

Microbial diversity analysis revealed similar fungal and bacterial community compositions in the intestinal and non-intestinal samples, with variations in the relative abundances of different microbial taxa (Fig. 2a–c). These differences were likely influenced by host species, sampling sites, environmental conditions (season, habitats, climate change), development stage and diets7,8,10,15,51,66. Ascomycota was most abundant fungal community in both habitats, aligning with previous studies on Ips species and Polygraphus poligraphus Linnaeus9, galleries of Megaplatypus mutatus Bright & Skidmore67 as well as other BBs26. Fungal taxa such as Erysiphales, Glomerales, Mucorales, Saccharomycetales and ophiostomatoid fungi9,15 were found frequently in this study, though with some regional variations compared to studies on Ips BBs in the Czech Republic9, Dendroctonus armandi Tsai & Li galleries68 in China, and Platypodinae species in Argentina67. Yeasts were particularly abundant in the intestinal and non-intestinal samples of spruce-feeding BBs compared to other dietary BBs. This was inconsistent with findings by Chakraborty3, who noted that this taxon had higher abundances in pine-feeding beetle (Ips acuminatus Wood & Bright). For α-diversity, it showed that fungal-symbionts were more abundant in the intestinal samples than in the non-intestinal ones. The bacterial communities of BBs were dominated by Pseudomonadota, Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, and Bacteroidetes, consistent with the results of previous studies on the components of symbiotic bacteria for beetles7,9,69,70. Within these communities, Enterobacterales, Pseudomonadales, and Bacillales exhibited higher diversity and relative abundances in the intestinal samples for this study. The results have been proved in the intestines of I. typographus15 and Samia ricini Anderson20. Enterobacter showed higher abundance in the intestinal and non-intestinal samples of I. chinensis (pine-feeding bark beetle) than that of other dietary beetles. Serratia, Erwinia had higher relative abundance in the intestinal than in the non-intestinal samples of I. chinensis (pine-feeding bark beetle), I. hauseri and I. nitidus (spruce-feeding BBs). It has been confirmed that Serratia, Erwinia and Enterobacter were more abundant in intestinal samples of Ips sexdentatus, Ips acuminatus, Ips duplicatus and Curculio chinensis8,71. Pseudomonas and Staphylococcus showed higher relative abundances in the intestinal samples of different dietary Ips BBs compared to those in the non-intestinal samples. These microbes were common taxa in the intestinal samples of BBs8,9. Additionally, interaction among the microbes affected microbial community structures and functionality36,40. In our study, mutualistic interrelationship in the intestinal microbes may be more complex than in the non-intestinal samples. Pantoea and Serratia only presented in the intestinal network interaction, indicating that these two genera may exhibit significant effects on the intestinal function. Pantoea, previously isolated from wood-boring beetle intestines, was known to fix nitrogen10,70.

Comparison of intestinal and non-intestinal microbial assemblies

Despite ongoing debates about the driving mechanisms of deterministic versus stochastic processes, our findings revealed distinct disparities between intestinal and non-intestinal environments. Intestinal tracts, enriched with abundant bacterial symbionts, are crucial for host digestion, detoxification, and transmission across generations for host adaptation5,6. Non-intestinal samples primarily carry or transmit symbionts for nutrition provision to host beetles3. In our work, HD and UP of the stochastic process may be the main driving force in the intestinal core microbial community assemblies. However, in the non-intestinal microbial assembly was governed by HS of the deterministic process, which may play more a critical role in maintaining the similarity and stability of the non-intestinal microbial communities. This finding aligned with previous research on Dicranocephalus wallichii bowringi Pascoe, honeybee Apis cerana Fabricius and A. mellifera, which highlighted that DL and drift influenced intestinal microbial community assemblies. However, HOS contributed to Apis mellifera intestinal microbial assembly due to unconsidered host species and geographical sites. Microbial community assemblies varied with surroundings, dietary trees, and host species42,49.

Nutritional provision deriving from non-intestinal fungi symbionts

Non-intestinal fungi have played pivotal roles in the survival and development of BBs3,24,72,73,74. In this study, gene abundance of oxidative phosphorylation process was the highest, particularly in the non-intestines of I. subelongatus. These fungal unigenes were found in Ogataea and Wickerhamomyces (Saccharomycetales) and Ophiostoma and Ceratocystis (ophiostomatoid fungi). Previous investigation of I. nitidus chromosome-level assembled genome confirmed that unigenes were enriched in energy metabolism32. It may be speculated that microbes and insect hosts were conjointly likely to involve in energy metabolism to overcome inhospitable environment, benefiting insects alone or both. However, detailed symbiotic mechanisms between Ips BBs and symbionts remained poorly understood. Fungal symbionts are keystone elements for steroid biosynthesis in BBs, with 40 fungal unigenes and seven enzymes in non-intestinal samples in this study. These genes were mainly classified into Candida, Ogataea, and Wickerhamiella. Previous studies have found that yeasts and other fungi serving as nitrogen sources have significant effects on hosts colonization and reproduction24,26,44,73,74,75. Additionally, the number of fungal unigenes was clearly higher than bacterial unigenes in the cell growth and death pathways (Cell cycle-yeast and Meiosis-yeast), suggesting that yeast symbionts have profoundly influence on biochemical signals sense, DNA damage and repair. I. nitidus genome analysis revealed that gene expression involved in DNA replication and repair was also greater, implying a cooperative role may exist between BBs and yeast symbionts. Ophiostomatoid fungi contain abundant ergosterol (sterol), which is essential for the development of eggs, larvae and pupae in BBs73,76. Ophiostoma and Ceratocystis exhibited higher gene abundance in the non-intestinal samples. Ophiostomataceae is regarded as an essential nitrogen source for the growth and development of Scolytinae beetles73. The fungi from this family Ceratocystidaceae, are able to detoxify defensive compounds warding off attacks from beetles or fungi to adapt and survive on a wide array of host trees, especially, this genus Ceratocytosis77,78. These symbionts in both two families and their associated insects can build novel destructive interrelations, posing hazards to health of forest agriculture in the long-term development79. Generally, yeasts and ophiostomatoid fungi may be closely related to nutrient metabolism for BBs. Nutrition provided by non-intestinal fungal symbionts may complement the metabolic capacities, fostering co-evolution within the symbiotic system.

Degradation of complex compounds by intestinal bacteria associates

Terpenoids and phenolics serve as defensive compounds by resisting bark beetles’ attacks and inhibit host colonization21,69,80,81. In this study, four enzymes were found to be involved in terpene degradation, which belonged to intestinal bacteria associated with five Ips BBs. These enzymes are capable of transforming α-pinene into 3-isopropylbut-3-enoic acid or converting geraniol to 5-Methyl-3-oxo-4-hexenoyl-CoA and take (-)-(s) limonene into perillic acid. The results are similar to previous enzymatic annotations of microbes associated with Dendroctonus ponderosae Hopkins, but there are slight variations in the distribution of genes related to this pathway, which belong to Pseudomonas, Rahnella, Serratia, and Stenotrophomonas69. Catechol, which consists of a benzene ring with adjacent hydroxyl groups, is regarded as fundamental structural unit of phenolic compounds. Enzymes (e.g. catechol dioxygenases) associated with it can effectively catalyze phenolics as carbon sources to enhance adaptability for host colonization82. These enzymes (Catechol 1,2- dioxygenase and Catechol 2,3- dioxygenase) were also found in our study.

Carbohydrases, including GH1, GH5, GH9, GH28, GH32, GH45, GH48, CE8, and PL4, play crucial roles in degrading complex compounds32,83. GHs have been annotated in Grosmannia clavigera (Rob.-Jeffr. & R.W. Davidson) Zipfel, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf. associated with D. ponderosae and microbes associated with Anoplophora glabripennis Motschulsky, which degrade polysaccharides19,84. In this study, 26 GHs, including 18 enzymes and 1,563 unigenes in the intestinal bacterial symbionts associated with Ips BBs, were found to be involved in degrading cellulose, xylan, xyloglucan, pectin and chitin (Supplementary Table S7). GH1 possessed 231 genes, which was the most abundant in polysaccharide metabolism. It was also found in the intestine of A. glabripennis, assisting to hydrolyze cellobiose19. We found GH9 may degrade cellulose, xyloglucan, starch and sucrose in this study. However, it was almost rare in BBs, such as I. nitidus, I. typographus, D. ponderosae and Hypothenemus hampei Ferrari32. Additionally, GH32 could convert sucrose into glucose and fructose85, which was only in D. ponderosae32. In our study, CE8, GT4, GT5 and GT26 may involve in degrading pectin, galactomannan, starch, and cellulose. Previous studies detected that these enzymes played an important role in regulating functionality of insects86. In addition, GH4, GH31, GH13, GH63, GH76, PL1, PL3 and PL9 were also found in bacterial symbionts associated with Ips BBs. It was speculated that microbes may help BBs degrade complex compounds.

These unigenes related to complex compounds were principally categorized into intestinal unclassified bacteria, Erwinia, Acinetobacter, Enterobacter, and Serratia (Supplementary Table S7), which are essential microbial taxa for BBs. Previous studies have been confirmed that most Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas, and Rahnella can promote host insect to degrade complex compounds20,63,71. In our study, bacterial unigenes in the intestinal samples were found to be far superior to non-intestinal fungal unigenes for every pathway of xenobiotics biodegradation and metabolism, indicating intestinal bacteria may make significant contributions to degrading complex substances. For example, unigenes involved in xenobiotics biodegradation and metabolism were greatly abundant in microbes associated with I. acuminatus8. Particularly, the benzoate degradation pathway, which possessed the highest number of unigenes in the xenobiotic detoxification, was crucial for detoxifying a variety of toxic compounds including phenols and benzaldehyde, which are common secondary metabolites in plants that hinder the attacks of bark-feeding pests. In sum, intestinal bacteria collaborated with BBs overcome toxic complex compounds from coniferous trees, facilitating colonization successfully.

Conclusions

The microbial community assembly mechanisms and functional structures were studied in the intestinal and non-intestinal samples of five Ips BBs using a metagenomic approach. Our findings demonstrated that hosts beetles, dietary trees, and specific habitats (intestines vs. non-intestines) significantly influenced microbial community compositions. Network analysis showed a tighter mutualistic symbiosis in the intestinal microbial communities compared to the non-intestinal ones. The core microbial community assemblies in the intestines were primarily driven by HD and UP, whereas HS was primary driver in the non-intestinal microbial community assemblies. This analysis provides fundamental insights into the spatial patterns of microbial communities in BBs. Additionally, Saccharomycetales and Ophiostomatoid fungi may serve as dominant core non-intestinal fungal communities to cope with nutritional deficiencies. Erwinia, Acinetobacter, Enterobacter, Serratia, and others may be served as crucial intestinal bacterial taxa by degrading or detoxifying defensive compounds, helping BBs survive in hostile environments.

Data availability

The raw data of metagenomic sequencing with SRAs (Ips subelongatus (SRR30159481-SRR30159486), Ips chinensis (SRR30172494-SRR30172499), Ips typographus (SRR30172520-SRR30172525), Ips hauseri (SRR30186660-SRR30186665), and Ips niditus (SRR24210634-SRR24210639) are available under NCBI.

References

Douglas, A. E. Multiorganismal insects: diversity and function of resident microorganisms. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 60, 17–34 (2015).

Henry, L. P., Bruijning, M., Forsberg, S. K. & Ayroles, J. F. The Microbiome extends host evolutionary potential. Nat. Commun. 12, 5141 (2021).

Kostovcik, M. et al. The ambrosia symbiosis is specific in some species and promiscuous in others: evidence from community pyrosequencing. ISME J. 9, 126–138 (2015).

Stappenbeck, T. S. & Virgin, H. W. Accounting for reciprocal host–microbiome interactions in experimental science. Nature 534, 191–199 (2016).

Gupta, A. & Nair, S. Dynamics of insect–microbiome interaction influence host and microbial symbiont. Front. Microbiol. 11, 1357 (2020).

Jing, T. Z., Qi, F. H. & Wang, Z. Y. Most dominant roles of insect gut bacteria: digestion, detoxification, or essential nutrient provision? Microbiome 8, 1–20 (2020).

Hernández-García, J. A., Briones-Roblero, C. I., Rivera-Orduña, F. N. & Zúñiga, G. Revealing the gut bacteriome of Dendroctonus bark beetles (Curculionidae: Scolytinae): diversity, core members and co-evolutionary patterns. Sci. Rep. 7, 13864 (2017).

Chakraborty, A. et al. Unravelling the gut bacteriome of Ips (Coleoptera: curculionidae: Scolytinae): identifying core bacterial assemblage and their ecological relevance. Sci. Rep. 10, 18572 (2020a).

Chakraborty, A. et al. Core mycobiome and their ecological relevance in the gut of five Ips bark beetles (Coleoptera: curculionidae: Scolytinae). Front. Microbiol. 11, 568853 (2020b).

Vasanthakumar, A. et al. Characterization of gut-associated bacteria in larvae and adults of the Southern pine beetle. Dendroctonus frontalis Zimmermann Environ. Entomol. 35, 1710–1717 (2006).

Engel, P. & Moran, N. A. The gut microbiota of insects-diversity in structure and function. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 37, 699–735 (2013).

Stefanini, I. Yeast-insect associations: it takes guts. Yeast 35, 315–330 (2018).

Raymann, K. & Moran, N. A. The role of the gut Microbiome in health and disease of adult honey bee workers. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 26, 97–104 (2018).

Zhang, S. et al. The gut microbiota in camellia weevils are influenced by plant secondary metabolites and contribute to saponin degradation. Msystems 5, e00692-19 (2020).

Veselská, T. et al. Proportions of taxa belonging to the gut core Microbiome change throughout the life cycle and season of the bark beetle Ips typographus. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 99, fiad072 (2023).

Colman, D. R. & Toolson, E. C. Takacs–Vesbach, C. D. Do diet and taxonomy influence insect gut bacterial communities? Mol. Ecol. 21, 5124–5137 (2012).

Silver, A. et al. Persistence of the ground beetle (Coleoptera: Carabidae) Microbiome to diet manipulation. PLoS One 16, e0241529 (2021).

Ryu, J. H., Ha, E. M. & Lee, W. J. Innate immunity and gut–microbe mutualism in Drosophila. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 34, 369–376 (2010).

Scully, E. D., Hoover, K., Carlson, J. E., Tien, M. & Geib, S. M. Midgut transcriptome profiling of Anoplophora glabripennis, a lignocellulose degrading cerambycid beetle. BMC Genom. 14, 1–26 (2013).

MsangoSoko, K. et al. Composition and diversity of gut bacteria associated with the Eri silk moth, Samia ricini, (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae) as revealed by culture-dependent and metagenomics analysis. J. Microbiol. Biotech. 30, 1367 (2020).

Xu, L., Lou, Q., Cheng, C., Lu, M. & Sun, J. Gut-associated bacteria of Dendroctonus valens and their involvement in verbenone production. Microb. Ecol. 70, 1012–1023 (2015).

Ceja-Navarro, J. A. et al. Gut microbiota mediate caffeine detoxification in the primary insect pest of coffee. Nat. Commun. 6, 7618 (2015).

Cao, S. et al. Gut microbiota metagenomics and mediation of phenol degradation in Bactrocera minax (Diptera, Tephritidae). Pest. Manag. Sci. 80, 3935–3944 (2024). Diptera.

Six, D. L. Ecological and evolutionary determinants of bark beetle—Fungus symbioses. Insects 339–366 (2012).

Wang, Z. et al. Ophiostomatoid fungi associated with Ips subelongatus, including eight new species from Northeastern China. IMA Fungus 11, 1–29 (2020).

Baños-Quintana, A. P., Gershenzon, J. & Kaltenpoth, M. The Eurasian Spruce bark beetle Ips typographus shapes the microbial communities of its offspring and the gallery environment. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1367127 (2024).

Barras, S. J. & Perry, T. J. Fungal symbionts in the prothoracic mycangium of Dendroctonus frontalis (Coleoptera: Scolytidae). Z. Angew. Entomol. 71, 95–104 (1972).

Vega, F. E. & Biedermann, P. H. W. On interactions, associations, mycetangia, mutualists and symbiotes in insect-fungus symbioses. Fungal Ecol. 44, 100909 (2020).

Vazquez-Ortiz, K. et al. Metabarcoding of mycetangia from the Dendroctonus frontalis species complex (Curculionidae: Scolytinae) reveals diverse and functionally redundant fungal assemblages. Front. Microbiol. 13, 969230 (2022).

Zhao, T., Axelsson, K., Krokene, P. & Borg-Karlson, A. K. Fungal symbionts of the Spruce bark beetle synthesize the beetle aggregation pheromone 2-methyl-3-buten-2-ol. J. Chem. Ecol. 41, 848–852 (2015).

Santini, A. & Faccoli, M. Dutch elm disease and elm bark beetles: a century of association. Iforest 8 (2), 126 (2015).

Wang, Z. et al. Genome and transcriptome of Ips nitidus provide insights into high-altitude hypoxia adaptation and symbiosis. Iscience 26, 107793 (2023).

Chang, R. et al. Ophiostomatoid fungi including a new species associated with Asian larch bark beetle Ips subelongatus, in Heilongjiang (Northeast China). Fungal Syst. Evol. 8, 155–161 (2021).

Jakuš, R. et al. Outbreak of Ips nitidus and Ips shangrila in northeastern margin of the Tibetan Plateau. In 10th IUFRO Workshop of WP 7, 20–23 (2010).

EPPO. Bulletin OEPP EPPO bulletin. Ips Hauseri 35, 450–452 (2005).

Fang, J. X. et al. Monoterpenoid signals and their transcriptional responses to feeding and juvenile hormone regulation in bark beetle Ips hauseri. J. Exp. Biol. 224 (9), jeb238030 (2021).

Knížek, M. & Cognato, A. I. Validity of Ips chinensis Kurentzov & Kononov confirmed with DNA data. Zool. Syst. 42, 229–235 (2017).

Wang, Z. et al. Identification of Ips species (Coleoptera: Scolytinae) in China. Scientia Silvae Sinicae. 5, 79–91 (2021).

Bentz, B. J. et al. Ips typographus and Dendroctonus ponderosae models project thermal suitability for intra- and inter-continental establishment in a changing climate. Front. Glob. 2, 1 (2019).

Netherer, S. et al. Interactions among Norway spruce, the bark beetle Lps typographus and its fungal symbionts in times of drought. J. Pest. Sci. 94, 591–614 (2021).

Yang, J., Lin, Q. & Chen, G. Risk analysis of Ips subelongatus Motschulsky. J. Northeast Forest. Univ. 35, 60–63 (2007).

Zhu, Y. X. et al. Gut microbiota composition in the sympatric and diet-sharing Drosophila simulans and Dicranocephalus wallichii bowringi shaped largely by community assembly processes rather than regional species pool. iMeta 1, e57 (2022).

Gould, A. L. et al. Microbiome interactions shape host fitness. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 115, E11951–E11960 (2018).

Zhou, F. et al. Altered carbohydrates allocation by associated bacteria-fungi interactions in a bark beetle-microbe symbiosis. Sci. Rep. 6, 20135 (2016).

Stegen, J. C. et al. Quantifying community assembly processes and identifying features that impose them. ISME J. 7, 2069–2079 (2013).

Chase, J. M. & Myers, J. A. Disentangling the importance of ecological niches from stochastic processes across scales. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 366, 2351–2363 (2011).

Chase, J. M. Drought mediates the importance of stochastic community assembly. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 104, 17430–17434 (2007).

Dini-Andreote, F., Stegen, J. C., Van Elsas, J. D. & Salles, J. F. Disentangling mechanisms that mediate the balance between stochastic and deterministic processes in microbial succession. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 112, E1326–E1332 (2015).

Ge, Y., Jing, Z., Diao, Q., He, J. Z. & Liu, Y. J. Host species and geography differentiate honeybee gut bacterial communities by changing the relative contribution of community assembly processes. MBio 12, e0075–e0021 (2021).

Cognato, A. I. Chapter 9. Biology, systematics, and evolution of Ips. In Bark Beetles ( eds Vega, F. E., Hofstetter, R. W.). 351–370 (Academic Press, 2015).

Delalibera, I., Handelsman, J. O. & Raffa, K. F. Contrasts in cellulolytic activities of gut microorganisms between the wood borer, Saperda vestita (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae), and the bark beetles, Ips pini and Dendroctonus frontalis (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Environ. Entomol. 34, 541–547 (2005).

Morales-Jiménez, J., Zúñiga, G., Ramírez-Saad, H. C. & Hernández-Rodríguez, C. Gut-associated bacteria throughout the life cycle of the bark beetle Dendroctonus rhizophagus Thomas and bright (Curculionidae: Scolytinae) and their cellulolytic activities. Microb. Ecol. 64, 268–278 (2012).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. Fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890 (2018).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012).

Li, D., Liu, C. M., Luo, R., Sadakane, K. & Lam, T. W. MEGAHIT: an ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics 31 (10), 1674–1676 (2015).

Gurevich, A., Saveliev, V., Vyahhi, N. & Tesler, G. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 29 (8), 1072–1075 (2013).

Zhu, W., Lomsadze, A. & Borodovsky, M. Ab initio gene identification in metagenomic sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 38 (12), e132–e132 (2010).

Steinegger, M. & Söding, J. MMseqs2 enables sensitive protein sequence searching for the analysis of massive data sets. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 1026–1028 (2017).

Kanehisa, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M., Furumichi, M. & Tanabe, M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D457–D462 (2016).

Bastian, M., Heymann, S. & Jacomy, M. Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. Proc. Int. AAAI Conf. Web Soc. Media 3 (1), 361–362 (2009).

Kumar, S., Stecher, G. & Tamura, K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7. 0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874 (2016).

Zhang, D. et al. PhyloSuite: an integrated and scalable desktop platform for streamlined molecular sequence data management and evolutionary phylogenetics studies. Mol. Ecol. Res. 20, 348–355 (2020a).

Morales-Jiménez, J., Zúñiga, G., Villa-Tanaca, L. & Hernández-Rodríguez, C. Bacterial community and nitrogen fixation in the red turpentine beetle, Dendroctonus valens leconte (Coleoptera: curculionidae: Scolytinae). Microb. Ecol. 58, 879–891 (2009).

Briones-Roblero, C. I., Rodríguez-Díaz, R., Santiago-Cruz, J. A. & Zúñiga, G. Rivera-Orduña, F. N. Degradation capacities of bacteria and yeasts isolated from the gut of Dendroctonus rhizophagus (Curculionidae: Scolytinae). Folia Microbiol. 62, 1–9 (2017).

Tripathi, B. M. et al. Soil pH mediates the balance between stochastic and deterministic assembly of bacteria. ISME J. 12, 1072–1083 (2018).

Khara, A., Chakraborty, A., Modlinger, R., Synek, J. & Roy, A. Comparativemetagenomic study unveils new insights on bacterial communities in two pine-feeding Ips beetles (Coleoptera: curculionidae: Scolytinae). Front. Microbiol. 15, 1400894 (2024).

Ceriani-Nakamurakare, E. et al. Metagenomic approach of associated fungi with Megaplatypus mutatus (Coleoptera: Platypodinae). Silva Fenn. 52, 9940 (2018).

Hu, X., Li, M. & Chen, H. Community structure of gut fungi during different developmental stages of the Chinese white pine beetle (Dendroctonus armandi). Sci. Rep. 5, 8411 (2015).

Adams, A. S. et al. Mountain pine beetles colonizing historical and Naive host trees are associated with a bacterial community highly enriched in genes contributing to terpene metabolism. Appl. Environ. Microb. 79, 3468–3475 (2013).

Hu, X., Wang, C., Chen, H. & Ma, J. Differences in the structure of the gut bacteria communities in development stages of the Chinese white pine beetle (Dendroctonus armandi). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 21006–21020 (2013).

Zhang, S. et al. Soil-derived bacteria endow Camellia weevil with more ability to resist plant chemical defense. Microbiome 10, 97 (2022).

Morales-Ramos, J. A., Rojas, M. G., Sittertz-Bhatkar, H. & Saldaña, G. Symbiotic relationship between Hypothenemus hampei (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) and Fusarium Solani (Moniliales: Tuberculariaceae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 93, 541–547 (2000).

Ayres, M. P., Wilkens, R. T., Ruel, J. J., Lombardero, M. J. & Vallery, E. Nitrogen budgets of phloem-feeding bark beetles with and without symbiotic fungi. Ecology 81, 2198–2210 (2000).

Guevara-Rozo, S. et al. Nitrogen and ergosterol concentrations varied in live Jack pine phloem following inoculations with fungal associates of mountain pine beetle. Front. Microbiol. 11, 1703 (2020).

Ranger, C. M. et al. Symbiont selection via alcohol benefits fungus farming by ambrosia beetles. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 115, 4447–4452 (2018).

Bentz, B. J. & Six, D. L. Ergosterol content of fungi associated with Dendroctonus ponderosae and Dendroctonus rufipennis (Coleoptera: curculionidae, Scolytinae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 99, 189–194 (2006).

Juzwik, J., Harrington, T. C., MacDonald, W. L. & Appel, D. N. The origin of Ceratocystis fagacearum, the oak wilt fungus. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 46, 13–26 (2008).

Hammerbacher, A. et al. A common fungal associate of the Spruce bark beetle metabolizes the Stilbene defenses of Norway Spruce. Plant. Physiol. 162, 1324–1336 (2013).

Wingfield, M. J. et al. Novel associations between ophiostomatoid fungi, insects and tree hosts: current status—Future prospects. Biol. Invasions 19, 3215–3228 (2017).

Dykes, L. & Rooney, L. W. Phenolic compounds in cereal grains and their health benefits. Cereal Food World 52, 105–111 (2007).

Hung, P. V. Phenolic compounds of cereals and their antioxidant capacity. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 56, 25–35 (2015).

Wadke, N. et al. The bark-beetle-associated fungus, Endoconidiophora polonica, utilizes the phenolic defense compounds of its host as a carbon source. Plant. Physiol. 171 (2), 914–931 (2016).

McKenna, D. D. et al. The evolution and genomic basis of beetle diversity. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 116, 24729–24737 (2019).

DiGuistini, S. et al. Genome and transcriptome analyses of the mountain pine beetle-fungal symbiont Grosmannia clavigera, a lodgepole pine pathogen. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 108, 2504–2509 (2011).

Ni, D. et al. Comprehensive utilization of sucrose resources via chemical and biotechnological processes: A review. Biotechnol. Adv. 60, 107990 (2022).

Nagare, M., Ayachit, M., Agnihotri, A., Schwab, W. & Joshi, R. Glycosyltransferases: the multifaceted enzymatic regulator in insects. Insect Mol. Biol. 30, 123–137 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We appreciated Meili Zhang, Chengli Wang, Lihua Ma and Fuzhong Han for providing the assistance in the field for the materials collection.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No. 32230071 and 32071769).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Caixia Liu: Investigation; data curation; formal analysis; software; writing—original draft. Huimin Wang: Methodology, writing—review and editing. Zheng Wang: Investigation; methodology; writing—review and editing. Lingyu Liang and Duan Liu: Investigation. Yaning Li: Writing—review and editing. Quan Lu: Data curation; funding acquisition; methodology; project administration; resources; supervision; validation; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. All authors reviewed this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, C., Wang, H., Wang, Z. et al. Distinct assembly processes of intestinal and non-intestinal microbes of bark beetles from clues of metagenomic insights. Sci Rep 15, 7910 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91621-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91621-9