Abstract

We theoretically analyze the enhancement and regulation of Goos-Hänchen (GH) shift in hyperbolic metamaterials in the near-infrared band. For a given incident wavelength, photonic crystals composed of graphene and dielectric present hyperbolic dispersion characteristics by modulating the Fermi energy of graphene. The phase of the reflection coefficient changes dramatically near the phase transition from hyperbolic dispersion to elliptic dispersion, and subsequently giant GH shift is achieved at the resonant angle. The largest GH shift is as high as 300λ. Great GH shift can be effectively realized by regulating the layers of graphene and the thickness of the dielectric as well. It is hoped that this research may provide theoretical guidance for the design of high-sensitivity sensors based on the GH shift effect in hyperbolic metamaterials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Goos–Hänchen (GH) shift1,2,3,4 refers to the lateral displacement of the reflected light beam relative to the position predicted by geometric optic when total reflection occurs. With the invention of photonic crystals5,6, researchers have successively carried out studies on the GH shift using photonic crystals7,8. In 2003, Felbacq et al.9 discovered that the GH shift exists in the photonic crystal band gap. In 2012, Soboleva et al.10 studied the GH shift on the surface of photonic crystals. The GH shift based on the modified Otto structure can be actively tuned through the Fermi energy, the relaxation time of the graphene, and the distance between the coupling prism and the graphene layer11. It can be seen that material properties and structural parameters have a significant impact on the GH shift from numerous studies on adjusting the GH shift. Based on this, we can achieve sensing performance by monitoring the GH shift signals. Sensors based on the GH shift possess high precision and sensitivity and can be widely applied in fields such as precision measurement, medicine, and optical sensing12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20.

The hyperbolic dispersion characteristic usually refers to a situation in which in the dielectric constant or permeability tensor of a material, the sign of one principal component is opposite to that of the other two principal components, making the iso-frequency curve of the material hyperbolic and showing extreme anisotropy. Materials with hyperbolic dispersion characteristics are called hyperbolic metamaterials (HMM). The hyperbolic dispersion characteristic has shown many unique electromagnetic properties in fields such as negative refraction, subwavelength imaging, and photonic crystals21,22,23,24,25,26. Graphene is a two-dimensional structure material in a hexagonal honeycomb lattice composed of a single layer of carbon atoms27. The optical response of graphene is represented by surface conductivity. The surface conductivity of graphene can be simply modulated by the gate voltage. Graphene can be used as a practical plasmonic optical material in the terahertz to infrared waveband, applied in aspects such as micro-nano photonics and optical metamaterials, and graphene also has extensive application value in constructing hyperbolic dispersive metamaterials28,29,30. In 2013, Mohanmed A. K. Othman et al. proposed a structure composed of graphene and dielectric and it can exhibit a hyperbolic dispersion relationship in the terahertz and mid-infrared bands31. In the same year, a tunable hyperbolic metamaterial composed of graphene and dielectric is proposed and this structure can be applied in the infrared band and the mid-infrared band to realize the tuning of the chemical potential of graphene32. The iso-hyperbolic dispersion characteristic exhibited by this material allows for a wider range of electromagnetic wave transmission. Sreekanth et al. analyzed numerically the negative refraction phenomenon of metamaterials composed of graphene and dielectric in the terahertz band33. The research shows that the hyperbolic dispersion relationship can be altered by changing the chemical potential of graphene and the thickness of the dielectric layer. If the hyperbolic dispersion characteristics are applied to the study of GH shift, it may further enhance the GH shift and its flexible tunability. The GH shift around the Brewster angle is investigated in the graphene-based hyperbolic metamaterials and it can be tuned by Fermi energy and thickness of dielectric34. The graphene hyperbolic metamaterial and one-dimensional superconductor photonic crystals are combined to observe the GH effect under the TE wave in the THz region35. For a composite system consists of glass, air and a hyperbolic metamaterial, the excitation of the surface polaritons in the terahertz (THz) frequency region results in enhanced GH shift which can be controlled and tuned by changing the slab’s optical axis orientation, graphene’s chemical potential and air gap thickness36. In this work, we analyze the enhancement and regulation of GH shift of hyperbolic metamaterials composed of graphene and dielectrics in near-infrared band. The sharp transition of the reflected phase is realized near the phase transition from hyperbolic dispersion to elliptic dispersion, and giant GH shift is achieved. Meanwhile, we investigate the effects of Fermi energy, the layers of graphene, and the thickness of the dielectric on GH shift. It is hoped that this study can provide a reference for the development of highly sensitive sensors.

Theoretical model and method

The optical properties of graphene can be described by optical functions. By using the Kubo formula37, the surface conductivity of graphene can be obtained in the absence of an external magnetic field, which is expressed as

The first term is the intraband conductivity of graphene, and the second term is the interband conductivity of graphene. In the formula, w is the angular frequency of the incident light, e is the electronic charge, \(\:\hslash\:\) is the reduced Planck constant, KB is the Boltzmann constant, EF is the Fermi energy of graphene, τ is the relaxation time, and T is the temperature.

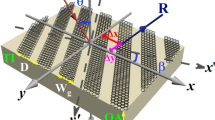

It is assumed that a transverse magnetic (TM) polarized light is incident from the air without considering the influence of the external electric field. The layered periodic stacking structure composed of graphene and dielectric (Polyimide) studied is shown in Fig. 1. θ and S represent the incident angle of the light and the GH shift, respectively. The number of periods is set as N = 6. The effective dielectric constant38 of the graphene can be expressed as

where ε0 represents the vacuum permittivity, and tg represents the single-layer thickness of graphene. The thickness and permittivity of the dielectric are td and εd respectively. Under the subwavelength condition, when the structural period is much smaller than the incident wavelength, that is, tg + td ≤ λ0. The effective medium theory can be used to study the propagation of the incident beam in the HMM layer39,40. The periodic structure composed of graphene and dielectric can be regarded as an effectively uniform uniaxial anisotropic medium. The direction perpendicular to the graphene layer is defined as the Z-axis. The dielectric constant tensor has a diagonalized form and can be expressed as

where εxx = εyy = ε∥, εzz = ε\(\bot\), ε\(\bot\) and ε∥ are the vertical and parallel parts of the permittivity, respectively, and can be written as

The effective thickness of graphene can be neglected compared to the thickness of the dielectric layer. For the propagation of TM waves, its dispersion surface can be expressed as

where kx and kz are the wave vectors of the structure in the X and Z directions respectively, and k0 is the wave vector in free space. If εxx · εzz < 0, the dispersion curve is hyperbolic, then the structure is also called Graphene-based hyperbolic metamaterials (GHMM). Conversely, if εxx · εzz > 0, the dispersion curve is elliptical.

For multilayer structures, The reflection coefficient, reflection coefficient phase and subsequent GH shift are derived from the transfer matrix method41,42,43, in which the matrix elements are functions of the effective dielectric constant. For a given dielectric layer i, when the electromagnetic wave is incident on the structure, the transfer matrix can be expressed as

where,

where \({{\text{n}}_d}=\sqrt {{\varepsilon _{\text{d}}}}\) and \({n_g}=\sqrt {{\varepsilon _g}}\), are the refractive indices of the dielectric and graphene, respectively. λ is the incident wavelength, and θ is the incident angle. ηd and ηg are the effective optical admittances in the dielectric and graphene, respectively. The overall transfer matrix for a multilayer material is derived by sequentially multiplying the transfer matrices of its layers, expressed as

Subsequently, the reflection coefficient of the entire structure can be determined using the relation,

The expression can be further written as r = |r| exp(iΦr), where |r| represents the amplitude and Φr denotes the reflection phase. The reflectivity can be calculated as R = |r|2. According to the stationary-phase approach11, the GH shift is expressed as

Numerical results and discussion

In order to better understand the role of hyperbolic dispersion characteristics in the enhancement and regulation of the GH shift, analyzing the equivalent permittivity of the periodic structure is extremely important.

In the calculation, the temperature is T = 300 K, the relaxation time is τ = 0.5 ps, the thicknesses of the graphene and dielectric are taken as tg = 0.5 nm and td = 50 nm, respectively, and the permittivity of the dielectric is εd = 2.88. It is assumed that a TM-polarized light with an incident angle θ = 0° enters from air. Figure 2(a) represents the real part εxx for different Fermi energies (EF = 0.6 eV, 0.7 eV, 0.8 eV, 0.9 eV, and 1.0 eV). The horizontal axis represents the incident wavelength. It can be seen that the real part of εxx gradually decreases and the value is always positive with the incident wavelength increasing.

Figure 2(b) shows the real part of εzz for different Fermi energies (EF = 0.6 eV, 0.7 eV, 0.8 eV, 0.9 eV, and 1.0 eV). With the increase of the Fermi energy, the incident wavelength corresponding to the transformation of the real part of εzz from positive to negative gradually decreases, exhibiting a blue shift. The real part of εzz undergoes a drastic change, jumping from a negative value to a positive one when the wavelength is around 1300 nm. With a small range of incident wavelength to the left side of λ = 1299.4 nm, the real part of εzz is negative. For EF = 0.6 eV, and the wavelength λ = 1299.4 nm, εxx ∙ εzz < 0, the dispersion curve is hyperbolic. We chose λ = 1299.4 nm as the incident wavelength.

The conductivity of graphene is an important factor affecting the GH shift of the periodic structure composed of graphene and dielectric. And the conductivity of graphene can be flexibly regulated by the Fermi energy. Therefore, we can achieve flexible regulation of the GH shift by changing the Fermi energy.

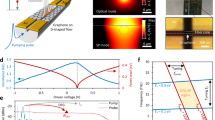

Figure 3a shows the curves of the reflectivity varying with the incident angle under the different Fermi energies. It can be seen that obvious troughs appear in the reflectivity with the change of the incident angle. Figure 3b is a partially enlarged view of the reflectivity (the yellow rectangular frame in Fig. 3a) in the range of the incident angle from 51° to 61°. Here, close-up views of the reflectivity are presented respectively for EF = 0.6 eV, 0.7 eV, 0.8 eV, 0.9 eV, and 1.0 eV. It can be observed that the incident angle corresponding to the extreme value of the reflectivity is affected by the Fermi energy.

For the five given values of EF = 0.6 eV, 0.7 eV, 0.8 eV, 0.9 eV, and 1.0 eV, Fig. 3c gives the curves of the phase of reflection coefficient varying with the incident angle. Each curve of the reflection coefficient phase exists a phase jumping at the resonant angle. It is worth noting that, according to Eq. (12), in order to obtain a larger GH shift, a larger slope of the reflection phase is required. For EF = 0.6 eV, the curve of the reflection phase is the steepest, which will result in a large GH shift. The slope of the curve in the figure is always positive, which will result in a negative GH shift.

The curves of the GH shift varying with the incident angle under the different Fermi energies are demonstrated in Fig. 3d. The negative GH shift varies with the Fermi energy increasing. For EF = 0.6 eV, the negative GH shift at the resonant angle can reach 300 λ, which is at the phase transition from hyperbolic dispersion to elliptic dispersion with a fixed incident wavelength. Therefore, the GH shift can be flexibly regulated by changing the Fermi energy.

The thickness of the dielectric is also an important parameter affecting the GH shift. The optical loss of the medium can not be ignored when the thickness of the dielectric gradually increases, and it can not be estimated by the equivalent medium theory when the thickness is too small. Therefore, we only consider the influence of the thickness change from 50 nm to 65 nm on the GH shift and set EF = 0.6 eV.

For the four given values of td = 50 nm, 55 nm, 60 nm, and 65 nm, Fig. 4a gives the curves of the reflectivity. There are obvious troughs appear in the reflectivity with the incident angle changing. Figure 4b presents a partially enlarged view of the reflectivity (within the yellow rectangular frame shown in Fig. 4a) in the range of the incident angle from 51° to 56°. The troughs of the reflectivity curve gradually shift to the right with td increasing. For the incident light, the optimal incident angle region for the absorption of the structure is affected by the thickness of the dielectric.

Figure 4c shows the curves of the reflection phase varying with the incident angle under the different thicknesses of dielectric. There is also a phase jumping near the resonant angle in the corresponding phase curve, which may produce a significant GH shift. Moreover, the slope of the curve corresponding to the reflection phase is always positive, which will result in a negative GH shift.

Figure 4d gives the curves of the GH shift varying with the incident angle for different td values. The negative GH shift decreases with td increasing. The large negative GH shift reaches 300 λ when td = 50 nm. Hence, the thickness of the dielectric played a key role for the GH shift.

For different values of Ng = 1, 2, 3, 4, Fig. 5a presents the curves of the reflectivity varying with the incident angle. Obvious troughs appear in the reflectivity with the incident angle increasing. Figure 5b is a partially enlarged view of the reflectivity (the yellow rectangular frame in Fig. 5a) in the range of the incident angle from 35° to 55°. The troughs of the reflectivity curves gradually shift to the left with Ng increasing. For the incident light, the optimal incident angle region for the absorption is affected by layers of graphene.

For different layers of graphene, the corresponding reflection coefficient phase abruptly jumps with the incident angle increasing as shown in Fig. 5c. The slope of the curve corresponding to the reflection phase is always positive, which will result in a negative GH shift. As shown in Fig. 5d, the maximum negative GH shift of 300 λ can be obtained when the layer of graphene is 1, which is at the phase transition point from elliptical dispersion to hyperbolic dispersion. It can be seen that the GH shift is always negative and decreases with layers of graphene increasing. This lateral shift can be regulated by the layers of graphene.

In Fig. 6a, the electric field distribution of the TM-polarized wave in the structure is simulated using the FDTD method with the COMSOL software. In Fig. 6b, the electric field distribution in the structure is simulated by the transfer matrix method with the MATLAB software. The layer of graphene is set to 1, and other parameters are the same as those in Fig. 5. The horizontal direction represents the arrangement direction of the graphene and dielectric sheets. The ordinate represents the intensity of the horizontal component of the electric field, which is normalized. It can be seen that the electric field distributions simulated by the two methods are identical. The intensity of electric field is localized on both terminals of this structure, which induces a sharp change in the reflection coefficient phase and consequently a great GH shift is resulted as well.

Conclusions

The enhancement and regulation of GH shift of hyperbolic metamaterials consisting of graphene and dielectric in the near-infrared band are investigated theoretically. By adjusting the Fermi energy of graphene, the structure exhibits hyperbolic dispersion characteristics. Near the phase transition from hyperbolic to elliptic dispersion, the phase of the reflection coefficient changes dramatically, resulting in a large GH shift. The GH shift can be adjusted through the Fermi energy, the thickness of the dielectric, and the layers of graphene. The large GH shift can reach 300 λ. It is hoped that this research can provide a theoretical basis for the development of high-sensitivity sensors based on the GH shift and hyperbolic dispersion characteristics.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Goos, F. & Hänchen, H. A new and fundamental experiment on total reflection. Ann. Phys. 436, 333–346 (1947).

Aiello, A. & Woerdman, J. P. Role of beam propagation in Goos–Hänchen and Imbert–Fedorov shifts. Opt. Lett. 33, 1437 (2008).

Aiello, A., Merano, M. & Woerdman, J. P. Brewster cross polarization. Opt. Lett. 34, 1207 (2009).

Araújo, M. P., Carvalho, S. A. & Leo, S. D. The asymmetric Goos–Hänchen effect. J. Opt. 16, 015702 (2014).

Yablonovitch, E. Inhibited spontaneous emission in solid-state physics and electronics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 58, 2059–2062 (1987).

John, S. Strong localization of photons in certain disordered dielectric superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 58, 2486–2489 (1987).

Ni, H. et al. Goos-Hänchen shifts around Fano resonances in superconducting photonic crystals embedded with graphene. Opt. Laser Technol. 182, 112186 (2024).

Ni, H., Zhou, G. P., Chen, X. L., Zhao, D. & Wang, Y. Non-reciprocal Spatial and quasi-reciprocal angular Goos–Hänchen shifts around double CPA-LPs in PT-symmetric Thue–Morse photonic crystals. Opt. Express. 31, 1234–1248 (2023).

Felbacq, D., Smaâli, R. & Moreau, A. Goos–Hänchen effect in the gaps of photonic crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 28, 1633–1635 (2003).

Soboleva, I. V., Moskalenko, V. V. & Moskalenko, A. A. Giant Goos-Hänchen effect and Fano resonance at photonic crystal surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 123901 (2012).

Zheng, Z. et al. Enhanced and controllable Goos–Hänchen shift with graphene surface plasmon in the Terahertz regime. Opt. Commun. 452, 227–232 (2019).

Santana, O. J. S., Carvalho, S. A. & Leo, S. D. Weak measurement of the composite Goos-Hänchen shift in the critical region. Opt. Lett. 41, 3884 (2016).

Wang, L. G., Chen, H. & Zhu, S. Y. Large negative Goos-Hänchen shift from a weakly absorbing dielectric slab. Opt. Lett. 30, 2936 (2005).

Liu, F. M. et al. Goos-Hänchen shift in cryogenic defect photonic crystals composed of superconductor HgBa2Ca2Cu3O8+δ. PLoS One. 0302142 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Experimental observation of a giant Goos-Hänchen shift in graphene using a beam splitter scanning method. Opt. Lett. 39, 5574 (2014).

Zhao, B. & Gao, L. Temperature-dependent Goos-Hänchen shift on the interface of metal /dielectric composites. Opt. Express. 17, 21433–21441 (2009).

Wang, Y. et al. Oscillating wave sensor based on the Goos-Hänchen effect. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 901 (2008).

Chen, C. W. et al. Optical temperature sensing based on the Goos–Hänchen effect. Appl. Opt. 46, 5347–5351 (2007).

Yu, T. Y. et al. Oscillating wave displacement sensor using the enhanced Goos–Hänchen effect in a symmetrical metal cladding optical waveguide. Opt. Lett. 33, 1001–1003 (2008).

Yin, X. B. & Hesselink, L. Goos–Hänchen shift surface plasmon resonance sensor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 261108 (2006).

Zhao, Y. T., Bian, W. U., Bei, J. H. & Qiang, C. Switchable broadband Terahertz absorber/reflector enabled by hybrid graphene-gold metasurface. Opt. Express. 25, 7161 (2017).

Neira, A. D., Wurtz, G. A. & Zayats, A. V. Superluminal and stopped light due to mode coupling in confined hyperbolic metamaterial waveguides. Sci. Rep. 5, 17678 (2015).

Pedrelli, D. C., Alexandre, B. & Peres, N. Excitation of SPP’s in graphene by a waveguide mode. Europhys. Lett. 126, 27001 (2019).

Bao, Q. et al. Broadband graphene polarizer. Nat. Photon. 5, 411–415 (2011).

Biehs, S. A., Tschikin, M. & Abdallah, P. B. Hyperbolic metamaterials as an analog of a blackbody in the near field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 104301 (2012).

Shi, Z., Jin, C. & Yang, W. Gate-dependent Pseudospin mixing in graphene/boron nitride moire superlattices. Nat. Phys. 10, 743–747 (2014).

Yen, T. J. et al. Terahertz magnetic response from artificial materials. Science 303, 1494–1496 (2004).

Wang, Y., Liu, Y. & Wang, B. Tunable electron wave filter and Goos–Hänchen shift in asymmetric graphene double magnetic barrier structures. Superlatt Microstruct. 60, 240–247 (2014).

Wang, L., Wang, L. G. & Zubairy, M. S. Tunable positive and negative group delays of light reflection from layer structures with a graphene layer. J. Appl. Phys. 122, 115301 (2017).

Jiang, L., Guo, J., Wang, Q., Dai, X. & Xiang, Y. Perfect Terahertz absorption with graphene surface plasmons in the modified Otto configuration. Plasmonics 12, 1825–1831 (2017).

Othman, M. A., Guclu, C. & Capolino, F. Graphene-based tunable hyperbolic metamaterials and enhanced near-field absorption. Opt. Express. 21, 7614–7632 (2013).

Othman, M. A., Guclu, C. & Guclu, F. Graphene-based hyperbolic metamaterial at Terahertz frequencies. CLEO. (2013).

Sreekanth, K. V., De Luca, A. & Strangi, G. Negative refraction in graphene-based hyperbolic metamaterials. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 509 (2013).

Kang, Y. Q., Xiang, Y. J. & Luo, C. Y. Tunable enhanced Goos-Hänchen shift of light beam reflected from graphene-based hyperbolic metamaterials. Appl. Phys. B. 124, 115 (2018).

Zhang, T., Mao, M. Y., Ma, Y., Zhang, D. & Zhang, H. F. Effect of Goos–Hänchen shift of the light transmitted through a mixture of the graphene hyperbolic metamaterial and 1D superconducting photonic crystals. Optik 223, 165636 (2020).

Shaabani, N., Madani, A., Shiri, M. & Abdi-Ghaleh, R. Goos–Hänchen effect on a graphene-based hyperbolic metamaterial slab. Appl. Phys. A. 126, 775 (2020).

Yu, Y., Kats, M. A., Genevet, P., Yu, N. & Capasso, F. Broad electrical tuning of graphene-loaded plasmonic antennas. Nano Lett. 13, 1257 (2013).

Jiang, L., Wang, Q., Xiang, Y., Dai, X. & Wen, S. Electrically tunable Goos–Hänchen shift of light beam reflected from a graphene-ondielectric surface. IEEE Photon J. 5, 6500108–6500108 (2013).

Ferrari, L., Wu, C., Wu, D., Wu, X. & Liu, Z. W. Hyperbolic metamaterials and their applications. Prog Quant. Electron. 40, 1–40 (2015).

Biehs, S. A., Tschikin, M. & Tschikin, P. B. Hyperbolic metamaterials as an analog of a blackbody in the near field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 104301 (2012).

Kumar, N., Kaliramna, S. & Singh, M. Design of cold plasma based ternary photonic crystal for microwave applications. Silicon 14, 6933–6944 (2022).

Wei, H. S. et al. Temperature sensing based on defect mode of one-dimensional superconductor-semiconductor photonic crystals. Crystals 13, 302 (2023).

Zhao, M. M. et al. Optical fractal in cryogenic environments based on distributed feedback Bragg photonic crystals. PLoS One. 18, e0291863 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (12274157), the Hubei Province Natural Science Foundation of China (2022CFB179), the Scientific Research Project of Hubei University of Science and Technology (BK202323) and the Young Talent Project of Scientific and Technological Research Plan of Hubei Provincial Department of Education (Q20232808).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Y.: Writing-original draft. Z.X.: Supervision. H.N.: Supervision. Z.Q.: Supervision. X.C.: Supervision. M.Z.: Writing-review and editing, supervision, funding acquisition. D.Z.: Supervision, funding acquisition, visualization.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, J., Xie, Z., Ni, H. et al. Tunable GH shift based on hyperbolic metamaterials composed of graphene and dielectric. Sci Rep 15, 7276 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91691-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91691-9