Abstract

Autologous bone marrow concentrate (BMC), platelet-rich plasma (PRP), and platelet lysate (PL) have emerged as promising orthobiologic treatment options for knee osteoarthritis (OA). The present observational study reports minimal clinically important difference (MCID) and substantial clinical benefit (SCB) values for several patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) used to monitor changes in joint pain and function following percutaneous treatment of knee OA with a combination of BMC and platelet products (n = 295 knees). Distribution-based approaches were used to determine 12-month MCID values for the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) subjective, Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS), Numeric Pain Scale (NPS), and modified Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation (SANE) scores. Alternatively, a within-cohort, anchor-based approach, leveraging the modified SANE as a global transition question, was used to determine MCID values of 12.2, 8.4, and − 1.8, and SCB values of 29.5, 22.5, and − 3.0 for IKDC, LEFS, and NPS, respectively. Approximately 87% of treated knees reported change scores that met or exceeded an MCID value while 59% reported change scores that met or exceeded an SBC value for one or more PROMs. In reporting MCID and SCB values for PROMs following the treatment of knee OA with a combination of BMC and platelet products, we sought to provide a foundation for assessing the clinical efficacy of orthobiologic interventions in this developing field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee is a continually advancing, degenerative joint disorder, increasing in prevalence with age and affecting millions of individuals nationwide1. Conventional approaches for the clinical management of knee OA span from conservative treatment to surgical intervention2,3. Lately, the intra-articular injection of several different autologous orthobiologics, including bone marrow concentrate (BMC)4,5,6, platelet-rich plasma (PRP)7,8,9, and platelet lysate (PL)10,11, have shown promise as minimally invasive therapies for improving joint function and pain in those with knee OA. Further, combining bone marrow- and whole blood-derived injections may offer a synergistic approach to mitigating the advancement of knee OA12. Studies utilizing animal models have reported treatment with BMC and PRP together to be significantly better than either treatment alone in the context of wound13, tendon14, and osteochondral15 healing, and the combined use of autologous BMC and PRP has been investigated in both surgical16 and injection-based17 approaches to treating knee OA.

To evaluate the efficacy of different treatment approaches, orthopedic research routinely utilizes psychometric instruments validated to assess joint function and pain. Commonly referred to as patient reported outcome measures (PROMs), these survey-based tools allow for the prospective monitoring of joint condition relative to pre-treatment levels18. However, when evaluating change between a pre-treatment and post-treatment PROM, a distinction should be made between patient reported differences that are statistically significant and those that are clinically meaningful19,20. Common measures of clinically significant difference include the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) and substantial clinical benefit (SCB). An MCID represents the smallest change in a PROM perceived to be of benefit by patients and is considered the lowest threshold for clinically significant improvement19, whereas an SCB represents a greater PROM change and is considered a threshold for substantial improvement and a better definition of clinical success21,22. Both MCID and SCB values are specific to patient population, clinical indication, and treatment modality20,23,24. Consequently, their transfer across different patient groups is not recommended23. Until recently, studies investigating orthobiologic injections for treating knee OA were largely limited to using MCID values established for surgical interventions, which may not accurately represent the clinical changes patients experience25.

The purpose of the present study was to determine measures of clinically significant difference specific to the percutaneous treatment of moderate to severe knee OA with a combination of autologous BMC and platelet products. In establishing these thresholds for several PROMs, we aimed to provide a more accurate representation of the clinically meaningful improvement patients report in response to this growing non-surgical, minimally invasive treatment modality for a prevalent musculoskeletal disorder. Using common distribution-based approaches, 12-month MCIDs were derived for the International Knee Documentation Committee subjective knee form (IKDC), the Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS), the Numeric Pain Scale (NPS), and a modified Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation (SANE). Moreover, 12-month SCB and alternative MCID values were derived for IKDC, LEFS, and NPS by way of a within-cohort, anchor-based approach that utilizes the modified SANE in lieu of a traditional 15-point global transition question (GTQ).

Methods

Study design

Data for this study was collected from a single orthopedic clinic beginning in the fall of 2015 and culminating in the spring of 2021 using an electronic patient registry (ClinCapture Software, Clinovo clinical Data Solutions, Sunnyvale, California, USA; Dacima Software, Quebec, Canada) for prospectively tracking patients receiving autologous orthobiologic-based treatments for musculoskeletal conditions with a series of questionnaires designed to monitor changes in clinical outcomes. Study approval was obtained through the International Cellular Medicine Society Institutional Review Board (OHRP #IRB00002637), all procedures were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, and informed consent was obtained from all individual participants. Patients participating in the registry were asked to complete joint-specific function and pain surveys at baseline, and follow-ups at 1-, 3-, 6-, 12-, 18-, 24-months and yearly thereafter, for up to twenty years. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement guidelines were followed (Supplementary Materials)26.

Patient selection

Inclusion criteria for this analysis comprised being aged 30–85, having moderate to severe knee OA based on physical examination, and having a Kellgren-Lawrence or Park classification grade II or greater based on radiograph or MRI, respectively. Exclusion criteria for this analysis comprised receiving knee injections within three months or undergoing any knee surgery within six months of treatment, having inflammatory or autoimmune joint disease, having bleeding disorders, having medication-induced myopathy or tendinopathy, taking anticoagulants or immunosuppressive medications, involvement in health-related litigation, having an orthopedic condition related to a workers’ compensation case, and/or having a history of chronic opioid use.

Autologous orthobiologic treatment

Two weeks preceding treatment, patients were requested to cease self-administration of steroidal and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. All injections were performed under ultrasound or fluoroscopic guidance to confirm proper needle placement, and any excess synovial fluid in the joint was aspirated prior to treatment, which consisted of a series of injections over a week’s time. An initial pretreatment injection of 4 mL dextrose (12.5%) and ropivacaine (0.125%) in normal saline was performed two to four days prior to BMC treatment to illicit a temporary inflammatory response. On the day of treatment, a total of 60–120 mL of bone marrow aspirate (BMA) was harvested from the posterior superior iliac spine, using a multi-site approach and small aspiration volumes to maximize progenitor cell yields. The BMA was manually processed into 2–6 mL of BMC by trained laboratory personnel following centrifugation and isolation of the nucleated cell containing layer27,28. A small representative volume (< 0.1 mL) of BMC was set aside to quantify nucleated cells with an image-based automated cell counter (TC20, BioRad, Hercules, California, USA). Approximately 60 mL of whole blood was obtained via venipuncture, and 4 mL leukocyte poor PRP was manually processed using a two-step centrifugation method in which platelets were isolated and concentrated within a reduced plasma volume29. Half the volume of PRP was frozen at -80 °C and thawed at room temperature to prepare PL.

Under sterile conditions, all patients received an intra-articular injection of approximately 5 mL containing a mixture of BMC and equal parts PRP and PL (3:1:1) into the affected knee(s). Moreover, significant bone marrow lesions were treated with intra-osseous BMC injection(s) and supporting structures, including ligaments, tendons, and the meniscus were injected with excess platelet products if determined to be damaged or diseased by the treating physician. A post-treatment intra-articular injection containing 4 mL of equal parts PRP and PL was performed two to four days following BMC treatment. Patients were provided braces to unload the affected knee compartment for four to six weeks. Although all were encouraged to participate in a standard stepwise rehabilitation protocol, it was not required. Additional details on the treatment approach have been previously reported17.

PROMs

Outcome measures included IKDC, LEFS, and NPS scores collected at baseline and post-treatment. The IKDC subjective score, ranging from 0 (extreme disability) to 100 (no functional disability), measures knee-specific symptoms, function, and sports activity in patients with a variety of knee conditions30. Similarly, the LEFS, ranging from 0 (extreme disability) to 80 (no functional disability), assesses functional limitations to a person’s lower extremity performing everyday activities31. The NPS is an eleven-point scale designed to assess pain intensity ranging from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst possible pain)32. Change in knee outcomes (ΔPROMs) were determined for IKDC, LEFS, and NPS by taking the difference between scores at baseline and post-treatment follow-up. A Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation (SANE) score was collected at all post-treatment follow-ups. Using the question, “Compared to your condition prior to the procedure, what percent difference have you seen in your condition?”, the SANE was modified to allow for a patient to report a worsening with − 100% representing maximum subjective worsening and 100% representing maximum subjective improvement.

Distribution-based derivation of MCID

Two common distribution-based approaches were used to derive MCID values, including determining the minimal detectable change and using one-half of the standard deviation of a change score. The minimal detectable change at the 95% confidence level (MDC95) was determined by multiplying the SEM of a PROM by 1.96 and the square root of two, MDC95 = SEM × 1.96 × √2, where 1.96 represents the zscore for a 95% confidence interval and the square root of two accounts for the error in repeat measurements. The standard error of measurement (SEM) was calculated by multiplying the standard deviation of patient reported baseline metrics (SDb) by the square root of one minus the test-retest reliability coefficient (r) for a given PROM, SEM = SDb × √ (1-r). Previously reported test-retest reliabilities of 0.95 and 0.94 were used for IKDC/NPS and LEFS, in turn30,31,32. MCIDs for the 12-month IKDC, LEFS, NPS, and SANE scores were also determined by multiplying the standard deviation of change in a PROM (SDΔPROM) by one-half, MCID = 0.5 × SDΔPROM25.

Anchor-based derivation of MCID and SCB

An anchor-based, within cohort approach was also used to derive MCID and SCB values for IKDC, LEFS, and NPS. In place of a traditional 15-point GTQ, the modified SANE was utilized as an anchor question. Minimal improvement, described as those responding, ‘A Little Better’ or ‘Somewhat Better’ on a 15-point GTQ, was defined as the patient cohort reporting SANE scores of 15–45%. A score range of 15% on the SANE is roughly one part in seven, which has been suggested to be the limit of human discrimination33 and is used to guide MCID calculations by others34. Similarly, substantial improvement, or those responding, ‘A Good Deal Better’, ‘A Great Deal Better’, or ‘A Very Great Deal Better’, was defined as the those reporting SANE scores equal to or greater than 60%. Patients reporting SANE score of 0–15% were considered not to have experienced clinical change (Fig. 1). MCID and SCB values were determined using the mean of 12-month ΔPROM scores from those within the minimal improvement (SANE 15-45%) and substantial improvement (SANE ≥ 60%) cohorts, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Summary statistics are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Differences in PROMs over time were evaluated using a mixed-effects analysis for repeated measures with Geisser-Greenhouse correction. Multiple comparisons were corrected for using the Tukey post hoc test, and multiplicity adjusted P values were reported with the family-wise alpha threshold set to 0.05. Strength of associations between 12-month SANE scores and the other ΔPROMs were measured using Pearson correlations. Results were considered significant at P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism Version 10.3.1 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, California, USA, www.graphpad.com).

Results

Patient demographics

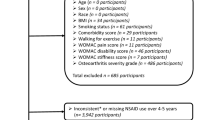

Three-hundred eighty-one patients (453 knees) with moderate to severe knee OA met the study criteria and were enrolled and PROMs were prospectively tracked following treatment with autologous BMC and PRP. Despite their initial inclusion within the study, some patients were ultimately excluded from the analysis for having additional knee injections or a surgical intervention post-treatment, for missing baseline or 12-month follow-up questionnaires, and/or for self-reporting little to no pain (NPS ≤ 1) at baseline. Measures of clinically significant difference were determined from the remaining 252 patients (295 knees) (Fig. 2). Of 108 females (43%) and 144 males (57%), aged 61 ± 9.3 years (BMI 27.5 ± 5), 43 patients (17%) underwent simultaneous BMC treatment on both knees and provided PROMs for each knee. The severity of OA measured with image-based classifications ranged from moderate (20% with grade II) to severe (48% with grade IV), with patients receiving an average of 777 ± 441 nucleated cells in 3.2 ± 1.6 mL of BMC (Table 1). Laboratory characterization was not performed for the leukocyte poor PRP injectates provided to study patients, although, representative leukocyte poor PRP (n = 70) prepared using the same methodology contained an average of 2,150 ± 566 × 103 platelets per µL and 0.9 ± 1.3 × 106 leukocytes per mL.

A summary of excluded knees. Alpha-2-Macroglobulin (A2M), Bone Marrow Concentrate (BMC), Corticosteroid (CS), Hyaluronic Acid (HA), Minimal Clinically Important Difference (MCID), NPS (Numeric Pain Scale), Osteoarthritis (OA), Patient Reported Outcome Metrics (PROMs), Substantial Clinical Benefit (SCB).

PROMs and distribution-based MCIDs

Knee PROMs improved significantly compared to baseline levels and persisted throughout the study follow-up period (P < 0.001). In the time between baseline and the 12-month follow-up, functional scores increased from 42.7 ± 14.9 to 63.6 ± 17.9 for IKDC and from 42.8 ± 14.5 to 58.7 ± 14.2 for LEFS, while pain scores decreased from 4.5 ± 1.9 to 2.1 ± 1.9. Meanwhile, SANE scores increased from 39.0 ± 31.6 at the 1-month follow-up (no pre-treatment SANE score) to 56.0 ± 33.3 at the 12-month follow-up. Using the standard deviation of baseline PROMs, distribution-based MDC95 values were 9.2, 9.8, and − 1.2 for IKDC, LEFS, and NPS, respectively. An MDC95 value was not calculated for SANE, as it is not collected at baseline (Table 2). Values for MCIDs can also be determined using the standard deviation of change in outcome scores, or ΔPROMs (Fig. 3). Mean ΔPROM scores at the 12-month follow-up and corresponding distribution-based MCIDs using the half standard deviation approach, were 20.9 ± 17.9 and 8.9 for IKDC (Fig. 3a), 15.8 ± 15.1 and 8.5 for LEFS (Fig. 3b), -2.4 ± 2.3 and − 1.1 for NPS (Fig. 3c), and 56.0 ± 33.3 and 16.7 for SANE (Fig. 3d).

Change in outcomes (ΔPROMs) after receiving autologous BMC and PRP treatment for knee OA. Patient reported changes in IKDC (a), LEFS (b), NPS (c), and SANE (d) scores at the 12-month follow-up (n = 295). Dashed lines indicate no change. Solid lines and overhead values represent mean ± standard deviation. The standard deviation of a ΔPROM (bold) multiplied by one-half represents a common approach for deriving a distribution-based MCID.

Anchor-based MCIDs and SCBs

Suitable relationships between SANE scores and the other ΔPROMs at the 12-month follow-up were confirmed (Fig. 4). Moderate positive correlations were observed between SANE and ΔIKDC, r = 0.627 (Fig. 4a), and between SANE and ΔLEFS, r = 0.582 (Fig. 4b), while a negative correlation was observed between SANE and ΔNPS, r = -0.370 (Fig. 4C), supporting use of the SANE as a GTQ for anchor-based derivations of the MCID and SCB (Fig. 5). The ‘minimal improvement’ (SANE 15-45%) cohort consisted of fewer than one-fifth of the patient population (45 of 299), while over half (170 of 299) fell within the ‘substantial improvement’ (SANE ≥ 60%) cohort (Fig. 5a). Using the within cohort mean change score, anchor-based MCID values of 12.2 for IKDC (Fig. 5b), 8.4 for LEFS (Fig. 5c), and − 1.8 for NPS (Fig. 5d) were determined for the 12-month follow-up. The percentage of patient knees meeting or exceeding 12-month anchor-based MCIDs was 68.5% for IKDC, 70.8% for LEFS, and 66.4% for NPS, with 87.1% meeting or exceeding the MCID one or more PROMs (Table 3). Anchor-based SCB values were 29.5 for IKDC, 22.5 for LEFS, and − 3.0 for NPS (Fig. 5b-d). The percentage of patient knees meeting or exceeding 12-month anchor-based SCBs was 32.5% for IKDC, 31.2% for LEFS, and 46.4% for NPS, with 58.6% meeting or exceeding the SCB for at least one PROM (Table 3).

Change in outcomes (ΔPROMs) for the ‘minimal improvement’ and ‘substantial improvement’ cohorts after receiving BMC and PRP treatment for knee OA. Patient reported SANE scores at 6- and 12-month follow-ups (a). Change in function (b-c) and pain (d) for those reporting minimal improvement (SANE = 15-45%, n = 45) and substantial improvement (SANE ≥ 60%, n = 166). Dotted lines specify SANE thresholds for improvement, dashed lines indicate no change, and solid lines represent means. Mean ΔPROMs of the minimal and substantial improvement cohorts (bold) represent a common, within cohort, approach for deriving an anchor-based MCID.

Discussion

The present study reports 12-month MCID and SCB values for evaluating change in IKDC, LEFS, and NPS scores reported by those receiving treatment with a combination of autologous BMC and platelet products for moderate to severe knee OA. An MCID represents the minimal amount of change within a PROM that a patient perceives as beneficial and is typically determined using one of two broad approaches, either distribution-based or anchor-based23. Distribution-based approaches rely upon the statistical characteristics of the studied patient population and are rooted in the variability of the dataset. Although the methodologies used to determine distribution-based MCIDs make use of all available data, they do not necessarily reflect any patient-perceived change, as any patient feedback on clinical success is omitted. Several distribution-based methods have been proposed, including the ‘one-half standard deviation’ and ‘MDC95’ approaches used here. Interestingly, our MCID value for IKDC was comparable (8.9 vs. 8.6) to that first reported for PRP treatment in a recent study including over two-hundred knee OA patients using the same ‘one-half standard deviation’ approach25. Though unexpectedly, distribution-based MCID values using this approach fell below the MDC95 for nearly every PROM evaluated, and values falling below the MDC95 cannot be reliably distinguished from measurement error or statistical noise35. A diverse patient population, ranging from high functioning athletes to the elderly, likely plays an important factor, as wide reported variability in baseline PROMs increases the magnitude of change score required to overcome the associated measurement error20.

Alternatively, anchor-based approaches to the MCID use an external question or ‘anchor’, traditionally a 15-point GTQ, to relate changes in a PROM to patient perspective on clinical improvement19,35. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) advises the application of anchor-based, within cohort approaches to discern meaningful clinical changes and to reserve distribution-based approaches for providing additional corroboration if needed36,37. Presently, the choice of GTQ is not standardized, nor is there consensus on the various levels of response needed to define a minimal improvement cohort, therefore, variability between studies can be significant20. While the patient registry utilized for the current study did not include a 15-point GTQ, the modified SANE score was obtained by way of similar language. Although a key difference between a traditional GTQ and the SANE score is the use of ordinal versus continuous change scales, one core criterion of a credible anchor is the existence of a satisfactory correlation with the PROM of interest38. A recent systematic review on anchor-based methods for determining MCID values concluded that most studies (> 70%) use a single, subjective anchor, and nearly half failed to evaluate a correlation between the anchor and selected research indicator, potentially leading to unreliable results39. The strength of correlations between SANE scores and ΔPROMs for the present study were greater than the recommended value of 0.3 and were comparable, if not superior, to those between more traditionally used GTQs and PROMs reported elsewhere35,40. Here, anchor-based MCIDs were largely greater than MCIDs determined using distribution-based approaches and are remarkably consistent with those originally proposed for the PROMs investigated31,41,42.

Some consider the MCID to be too low of a threshold, failing to adequately address patient satisfaction or whether substantial benefit was derived from the treatment in question and therefore, recommend additional measures of clinically significant difference beyond ‘minimal’ be reported43. In contrast to MCID, the SCB represents a change that is reflective of considerable clinical improvement22,44. Our 12-month SCB for IKDC following combined autologous BMC and PRP treatment of 29.5 falls between the SCB values of 26.9 and 34.4, reported for the surgical approaches of osteochondral allograft transplantation and autologous chondrocyte implantation, respectively21,45. Currently, there do not appear to be any reported SCB values for LEFS or NPS scores in the literature pertaining to treatments for knee OA, and to our knowledge, an SCB value of 22.5 is the first proposed for the LEFS for any indication. Meanwhile, an SCB value of -2.5 for NPS was determined for back and leg pain following lumbar spinal fusion, comparable to the SCB value of -3 reported here22.

In reporting measures of clinically significant difference for the treatment of knee OA with a combination of autologous orthobiologics, we sought to address a potentially problematic issue whereby measures derived from surgical procedures are used to evaluate the clinical success of an injection-based treatment. Adopting an MCID or SCB from a different clinical context could result in misinterpretation of patient outcomes, as a low metric could lead to an overestimation of success, while a high metric could mischaracterize some patients as failing a beneficial treatment23. For example, a randomized controlled trial investigating the treatment of knee OA with autologous PRP used a 12-month MCID value of 16.7 for the IKDC score based on surgical approaches to treating patients with articular cartilage lesions46,47. By the study endpoint, the PRP cohort reported a mean change in IKDC of 14.2, which was lower than the chosen MCID. However, had the originally proposed MCID value of 11.5 for the IKDC been used, conclusions on the clinical significance of PRP for improving knee function may have been reported differently42. On the other hand, some PRP studies have used MCID values for the IKDC almost half of that, potentially overestimating the magnitude of clinical success48,49. Therefore, it is important to utilize metrics that are appropriate for the patient population and treatment modality investigated, and it has been recommended that future studies reporting measures of clinically significant difference would derive them from their own study population20.

There are several limitations to consider for the present study. As reported by others, multiple methods are available for deriving a measure of clinically significant difference, resulting in a wide range of values for any given PROM50. For the present analysis, three different approaches to deriving an MCID were used to provide an overview. However, the anchor-based, within cohort approach is favored as it both incorporated patient perspective on change in condition post-treatment and largely yielded the greatest, and therefore most conservative, thresholds for clinically relevant change. Yet, to our knowledge, utilizing the SANE as a GTQ for determining an anchor-based MCID and/or SCB has not been reported to date, further contributing to the lack of standardization amongst anchor questions. Moreover, SANE score ranges representing ‘minimal’ and ‘substantial’ improvement were subjective, similar to selected response ranges from other commonly used anchor questions. Study PROMs were collected with an electronic patient registry, which can be subject to selection bias and missing data owing to loss of follow-up51. Further, the studied patient population varied significantly with respect to baseline pain and functional status, and measures of clinically significant difference could change for patient subpopulations depending on baseline severity23,52. Additionally, treatment was tailored to an individual patient’s knee(s) with different joint structures injected depending on clinical presentation, and the biologic contents themselves varied compositionally. Future studies will utilize registry data to determine measures of clinically significant difference for additional PROMs and/or indications following treatment with autologous orthobiologics.

Conclusion

This present study establishes measures of clinical significance in knee OA patients treated with a combination of autologous BMC and platelet products for several PROMs, using an FDA recommended within-cohort, anchor-based approach to incorporate patient perspective. MCID and SCB values were 12.2 and 29.5 for IKDC, 8.4 and 22.3 for LEFS, and − 1.8 and − 3.0 for NPS, respectively. Ultimately, our goal is to foster accurate clinical decision-making and enhance understanding of patient responses to orthobiologic treatment through representative clinical metrics.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed for the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Lawrence, R. C. et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the united States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 58, 26–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.23176 (2008).

Palmer, J. S. et al. Surgical interventions for symptomatic mild to moderate knee osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 7, CD012128. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012128.pub2 (2019).

Lim, W. B. & Al-Dadah, O. Conservative treatment of knee osteoarthritis: A review of the literature. World J. Orthop. 13, 212–229. https://doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v13.i3.212 (2022).

Belk, J. W. et al. Patients with knee osteoarthritis who receive Platelet-Rich plasma or bone marrow aspirate concentrate injections have better outcomes than patients who receive hyaluronic acid: systematic review and Meta-analysis. Arthroscopy 39, 1714–1734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2023.03.001 (2023).

Pabinger, C., Lothaller, H. & Kobinia, G. S. Intra-articular injection of bone marrow aspirate concentrate (mesenchymal stem cells) in KL grade III and IV knee osteoarthritis: 4 year results of 37 knees. Sci. Rep. 14, 2665. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51410-2 (2024).

Keeling, L. E. et al. Bone marrow aspirate concentrate for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review. Am. J. Sports Med. https://doi.org/10.1177/03635465211018837 (2021).

Belk, J. W. et al. Platelet-Rich plasma versus hyaluronic acid for knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Sports Med. 49, 249–260. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546520909397 (2021).

Bansal, H. et al. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) in osteoarthritis (OA) knee: correct dose critical for long term clinical efficacy. Sci. Rep. 11, 3971. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-83025-2 (2021).

Dai, W. L., Zhou, A. G., Zhang, H. & Zhang, J. Efficacy of Platelet-Rich plasma in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: A Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthroscopy 33 (e651), 659–670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2016.09.024 (2017).

Gupta, A. & Maffulli, N. Platelet lysate and osteoarthritis of the knee: A review of current clinical evidence. Pain Ther. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-024-00661-y (2024).

Valtetsiotis, K. et al. Platelet lysate for the treatment of osteoarthritis: a systematic review of preclinical and clinical studies. Musculoskelet. Surg. 108, 275–288. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12306-024-00827-z (2024).

Balusani, P. Jr., Shrivastava, S., Pundkar, A. & Kale, P. Navigating the therapeutic landscape: A comprehensive review of Platelet-Rich plasma and bone marrow aspirate concentrate in knee osteoarthritis. Cureus 16, e54747. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.54747 (2024).

Mohammed, R. N., Sadat, A., Hassan, S. A., Mohammed, S. M. A., Ramzi, D. O. & H. F. & Combinatorial influence of bone marrow aspirate concentrate (BMAC) and Platelet-Rich plasma (PRP) treatment on cutaneous wound healing in BALB/c mice. J. Burn Care Res. 45, 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1093/jbcr/irad080 (2024).

Liu, X. N. et al. Enhanced Tendon-to-Bone healing of chronic rotator cuff tears by bone marrow aspirate concentrate in a rabbit model. Clin. Orthop. Surg. 10, 99–110. https://doi.org/10.4055/cios.2018.10.1.99 (2018).

Betsch, M. et al. Bone marrow aspiration concentrate and platelet rich plasma for osteochondral repair in a Porcine osteochondral defect model. PLoS One. 8, e71602. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0071602 (2013).

Hede, K., Christensen, B. B., Jensen, J., Foldager, C. B. & Lind, M. Combined bone marrow aspirate and Platelet-Rich plasma for cartilage repair: Two-year clinical results. Cartilage https://doi.org/10.1177/1947603519876329 (2019).

Centeno, C. et al. A specific protocol of autologous bone marrow concentrate and platelet products versus exercise therapy for symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial with 2 year follow-up. J. Transl Med. 16, 355. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-018-1736-8 (2018).

Wang, D., Jones, M. H., Khair, M. M. & Miniaci, A. Patient-reported outcome measures for the knee. J. Knee Surg. 23, 137–151. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1268691 (2010).

Jaeschke, R., Singer, J. & Guyatt, G. H. Measurement of health status. Ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Control Clin. Trials. 10, 407–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-2456(89)90005-6 (1989).

Bloom, D. A. et al. The minimal clinically important difference: A review of clinical significance. Am. J. Sports Med. 51, 520–524. https://doi.org/10.1177/03635465211053869 (2023).

Ogura, T., Ackermann, J., Barbieri Mestriner, A., Merkely, G. & Gomoll, A. H. Minimal clinically important differences and substantial clinical benefit in Patient-Reported outcome measures after autologous chondrocyte implantation. Cartilage 11, 412–422. https://doi.org/10.1177/1947603518799839 (2020).

Glassman, S. D. et al. Defining substantial clinical benefit following lumbar spine arthrodesis. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 90, 1839–1847. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.G.01095 (2008).

Wright, A., Hannon, J., Hegedus, E. J. & Kavchak, A. E. Clinimetrics corner: A closer look at the minimal clinically important difference (MCID). J. Man. Manip Ther. 20, 160–166. https://doi.org/10.1179/2042618612Y.0000000001 (2012).

Wellington, I. J. et al. Substantial clinical benefit values demonstrate a high degree of variability when stratified by time and geographic region. JSES Int. 7, 153–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jseint.2022.10.003 (2023).

Boffa, A. et al. Minimal clinically important difference and patient acceptable symptom state in patients with knee osteoarthritis treated with PRP injection. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 9, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/23259671211026242 (2021).

von Elm, E. et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 370, 1453–1457. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X (2007).

Centeno, C., Pitts, J., Al-Sayegh, H. & Freeman, M. Efficacy of autologous bone marrow concentrate for knee osteoarthritis with and without adipose graft. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 370621. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/370621 (2014).

Berger, D. R., Aune, E. T., Centeno, C. J. & Steinmetz, N. J. Cryopreserved bone marrow aspirate concentrate as a cell source for the colony-forming unit fibroblast assay. Cytotherapy 22, 486–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcyt.2020.04.091 (2020).

Williams, C. et al. Regenerative injection treatments utilizing platelet products and prolotherapy for cervical spine pain: A functional spinal unit approach. Cureus 13, e18608. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.18608 (2021).

Irrgang, J. J. et al. Development and validation of the international knee Documentation committee subjective knee form. Am. J. Sports Med. 29, 600–613. https://doi.org/10.1177/03635465010290051301 (2001).

Binkley, J. M., Stratford, P. W., Lott, S. A. & Riddle, D. L. The lower extremity functional scale (LEFS): scale development, measurement properties, and clinical application. North American orthopaedic rehabilitation research network. Phys. Ther. 79, 371–383 (1999).

Alghadir, A. H., Anwer, S., Iqbal, A. & Iqbal, Z. A. Test-retest reliability, validity, and minimum detectable change of visual analog, numerical rating, and verbal rating scales for measurement of Osteoarthritic knee pain. J. Pain Res. 11, 851–856. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S158847 (2018).

Miller, G. A. The magical number seven plus or minus two: some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychol. Rev. 63, 81–97 (1956).

Norman, G. R., Sloan, J. A. & Wyrwich, K. W. The truly remarkable universality of half a standard deviation: confirmation through another look. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 4, 581–585. https://doi.org/10.1586/14737167.4.5.581 (2004).

Revicki, D., Hays, R. D., Cella, D. & Sloan, J. Recommended methods for determining responsiveness and minimally important differences for patient-reported outcomes. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 61, 102–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.03.012 (2008).

Patient-focused drug development guidance 3 discussion document: select, develop or modify fit-for-purpose clinical outcome assessments. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/NewsEvents/UCM620708.pdf (2018).

McLeod, L. D., Coon, C. D., Martin, S. A., Fehnel, S. E. & Hays, R. D. Interpreting patient-reported outcome results: US FDA guidance and emerging methods. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 11, 163–169. https://doi.org/10.1586/erp.11.12 (2011).

Devji, T. et al. Evaluating the credibility of anchor based estimates of minimal important differences for patient reported outcomes: instrument development and reliability study. BMJ 369, m1714. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1714 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Xi, X. & Huang, Y. The anchor design of anchor-based method to determine the minimal clinically important difference: a systematic review. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 21, 74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-023-02157-3 (2023).

Ward, M. M., Guthrie, L. C. & Alba, M. Domain-specific transition questions demonstrated higher validity than global transition questions as anchors for clinically important improvement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 68, 655–661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.01.028 (2015).

Farrar, J. T., Young, J. P. Jr., LaMoreaux, L., Werth, J. L. & Poole, M. R. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain 94, 149–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00349-9 (2001).

Irrgang, J. J. et al. Responsiveness of the international knee Documentation committee subjective knee form. Am. J. Sports Med. 34, 1567–1573. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546506288855 (2006).

Rossi, M. J., Brand, J. C. & Lubowitz, J. H. Minimally clinically important difference (MCID) is a low bar. Arthroscopy 39, 139–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2022.11.001 (2023).

Harris, J. D., Brand, J. C., Cote, M., Waterman, B. & Dhawan, A. Guidelines for proper reporting of clinical significance, including minimal clinically important difference, patient acceptable symptomatic State, substantial clinical benefit, and maximal outcome improvement. Arthroscopy 39, 145–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2022.08.020 (2023).

Ogura, T., Ackermann, J., Mestriner, A. B., Merkely, G. & Gomoll, A. H. The minimal clinically important difference and substantial clinical benefit in the patient-reported outcome measures of patients undergoing osteochondral allograft transplantation in the knee. Cartilage 12, 42–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1947603518812552 (2021).

Lin, K. Y., Yang, C. C., Hsu, C. J., Yeh, M. L. & Renn, J. H. Intra-articular injection of Platelet-Rich plasma is superior to hyaluronic acid or saline solution in the treatment of mild to moderate knee osteoarthritis: A randomized, Double-Blind, Triple-Parallel, Placebo-Controlled clinical trial. Arthroscopy 35, 106–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2018.06.035 (2019).

Greco, N. J. et al. Responsiveness of the international knee Documentation committee subjective knee form in comparison to the Western Ontario and McMaster universities osteoarthritis index, modified Cincinnati knee rating system, and short form 36 in patients with focal articular cartilage defects. Am. J. Sports Med. 38, 891–902. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546509354163 (2010).

Kim, J. H., Park, Y. B., Ha, C. W., Roh, Y. J. & Park, J. G. Adverse reactions and clinical outcomes for Leukocyte-Poor versus Leukocyte-Rich Platelet-Rich plasma in knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 9, 23259671211011948. https://doi.org/10.1177/23259671211011948 (2021).

Park, Y. B., Kim, J. H., Ha, C. W. & Lee, D. H. Clinical efficacy of Platelet-Rich plasma injection and its association with growth factors in the treatment of mild to moderate knee osteoarthritis: A randomized Double-Blind controlled clinical trial as compared with hyaluronic acid. Am. J. Sports Med. 49, 487–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546520986867 (2021).

Franceschini, M. et al. The minimal clinically important difference changes greatly based on the different calculation methods. Am. J. Sports Med. 51, 1067–1073. https://doi.org/10.1177/03635465231152484 (2023).

Psoter, K. J. & Rosenfeld, M. Opportunities and pitfalls of registry data for clinical research. Paediatr. Respir Rev. 14, 141–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prrv.2013.04.004 (2013).

Alma, H. et al. Baseline health status and setting impacted minimal clinically important differences in COPD: an exploratory study. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 116, 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.07.015 (2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.C. and N.S. were involved in study conception. N.S. and E.D. contributed to data acquisition. D.B., E.D., and M.M. contributed to the data analysis and material presentation. Manuscript preparations written by D.B., J.G., E.D., and M.M. All authors commented on previous versions and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

This study was self-funded by the Centeno-Schultz Clinic and Regenexx. One or more of the authors has declared a potential conflict of interest. D.B., E.D., M.M., and N.S. are or were employed by Regenexx during the study period but have no further disclosures. C.C. is a shareholder, patent holder, and Chief Medical Officer of Regenexx and an owner of the Centeno-Schultz Clinic. J.G. is a Regenexx provider.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Centeno, C.J., Ghattas, J.R., Dodson, E. et al. Establishing metrics of clinically meaningful change for treating knee osteoarthritis with a combination of autologous orthobiologics. Sci Rep 15, 7244 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91972-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91972-3