Abstract

Candidiasis poses a significant threat to human health, especially in immunocompromised patients. However, there is a paucity of epidemiological data concerning the prevalence of candidiasis in developing regions of China. We conducted a retrospective study on patients positive for Candida infections in a tertiary care hospital in Shantou, China, to identify the clinical characteristics and risk factors for candidiasis. Of 5,095 cases of candidiasis, 489 (9.59%) were candidemia infections. Candida albicans (n = 230, 47.0%) was the predominant species identified among all patients. Non-albicans Candida (NAC) was more prevalent in adult patients, while Candida glabrata was slightly more frequent in pediatric patients (n = 10, 14.7%). Pulmonary diseases (n = 200, 47.8%) were the most common underlying comorbidities in adult patients (n = 25, 35.2%). Thrombocytopenia was the only laboratory finding higher in adult patients than in pediatric patients. Respiratory dysfunction, the presence of a central venous catheter, septic shock, and thrombocytopenia were independent risk factors for candidemia-related 30-day mortality. Amphotericin B exhibited high efficacy (100%), and itraconazole exhibited the lowest efficacy against all tested Candida isolates. C. glabrata had a lower susceptibility to azole, although this was not statistically significant. The epidemiological data on candidiasis, specifically candidemia in pediatric and adult patients, varied regarding the prevalence of Candida species and associated risk factors. This study provides guidance for prescribing the appropriate therapy and yields insights into the susceptibility patterns of different Candida isolates to antifungal drugs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Candida is an opportunistic fungal pathogen that causes superficial or invasive infections in immunocompromised individuals1,2. Invasive candidiasis (IC), which presents in severe forms such as bloodstream Candida infections (candidemia) and deep-seated infections, most often occurs in hospitalized patients1,2. Candidemia is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates3. However, the global incidence of candidemia varies according to the local epidemiology, geographic location, patient gender, age, and other factors. Based on single and multicenter investigations, estimates of candidemia rates range from 0.21 to 5 per 1,000 admitted patients4,5,6,7. The onset of candidemia leads to difficulties in treatment and often extends hospital stays, thereby imposing a significant burden on patients and healthcare systems8,9.

More than 40 species of Candida are known to cause candidemia. C. albicans is the most prevalent species identified in epidemiological studies10. However, the prevalence of non-albicans Candida (NAC) candidemia has been increasing across different age groups11,12,13,14,15,16. C. tropicalis, C. glabrata, C. parapsilosis, and C. krusei are the predominant species associated with NAC. Each Candida species has a unique invasive ability, virulence, tissue tropism, and antifungal sensitivity profile17,18. The risk factors for candidemia include cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal pathology, diabetes mellitus, hematologic malignancies, respiratory dysfunction, respiratory diseases, solid-organ tumors, low birth weight in neonates and preterm infants, broad-spectrum antimicrobial agent use, total parenteral nutrition, central venous catheterization (CVC), hemodialysis, surgery, and thrombocytopenia4,19,20,21. Studies in different regions of China have shown that the prevalence of Candida species (both C. albicans and NAC) and infection risk factors vary geographically and among age groups. Therefore, local epidemiological and surveillance studies are required for the prevention and treatment of candidemia.

The susceptibility of Candida pathogens to antifungal agents is a matter of concern owing to the limited availability of antifungal drugs and the emergence of multi-drug resistant strains18,22. Early and appropriate treatment is crucial for improving overall outcomes in individuals with candidemia23,24,25, requiring prompt administration of specific antifungal therapy. Comprehensive local epidemiological data and knowledge of antifungal susceptibility profiles and trends are crucial for selecting the initial antifungal treatment26,27,28. A recent systematic study in China reported the susceptibility profiles of various Candida species to antifungal agents and compared the results to other regions worldwide29. The study also reported that susceptibility profiles varied among regions of China. Therefore, studying the susceptibility profiles of antifungal agents is necessary for proper antifungal treatments. It is also important to collect epidemiological data on both pediatric and adult patients in local regions.

Azoles are the most commonly used antifungal therapy against candidiasis, followed by echinocandins, while polyenes are rarely prescribed due to their toxicity. Switching antifungal therapy may be necessary in cases of drug resistance, treatment failure, or patient intolerance30. The therapeutic efficacy of antifungal drugs against candidiasis depends on the strain type, severity of the infection, and underlying morbidities. The emergence of antifungal resistance, poor drug absorption in some patients, and drug-drug interactions also affect the efficacy of antifungal agents. Therefore, the microbiological, clinical, and pathological conditions of patients need to be closely monitored for the appropriate adjustment of treatment dosage31.

The current study investigated the incidence, risk factors, and antifungal drug susceptibility associated with candidiasis over 11 years at the Second Affiliated Hospital in Shantou, Guangdong, China. The study provides crucial clinical data on the distribution, risk factors, and antifungal susceptibility profiles of various Candida pathogens associated with candidiasis, specifically those causing candidemia in pediatric and adult patients. Our findings will provide relevant information for healthcare officials and prescribers, thereby aiding in the formulation of strategies to control candidemia in the region.

Methods

Patient data collection

The current retrospective analysis spanned 11 years from 2011 to 2021 and was conducted at a 1500-bed tertiary facility (Hospital A) under the administration of the Shantou Second Affiliated Hospital. This facility provides health services to 4.5 million people in Shantou City, China. Candida infections were diagnosed according to the guidelines for candidiasis management established by the China Medical Association and the Infectious Diseases Society of America32,33. The demographic data and clinical characteristics of patients with candidiasis were collected from the hospital’s electronic medical records. The study examined the mortality rate from one week to one month based on patient age, gender, admission ward, underlying comorbidities, and previous invasive procedures performed over the previous month.

Microbiological methods and susceptibility testing

Candida species were isolated from biological specimens obtained from patients using appropriate protocols, followed by direct microscopy with potassium hydroxide. Blood was inoculated in BacT/AlerT 3D (bioMérieux, France) and cultured aerobically and anaerobically on CHROMagar-Candida medium. All Candida isolates were identified by Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS) using the MALDI Biotyper RTC 4.0 package (Bruker Diagnostics, Inc., USA). Antifungal susceptibility testing of five drugs, amphotericin B (AMB), flucytosine (FC), fluconazole (FCA), itraconazole (ITR), and voriconazole (VRC), was conducted for the isolated strains using the ATB FUNGUS 3 kit (bioMérieux, France) that is commonly used in China34. The strain C. krusei ATCC (6258) and C. parapsilosis ATCC (22019) were used for quality control18. The interpretation of susceptibility testing results followed the guidelines established by the Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institutes (CLSI)35,36.

Interpretation of MIC results

MIC data were analyzed using the CLSI protocol M27-S4, and interpretation of susceptibility was performed by using CLSI clinical breakpoints (CBPs)35,37, or epidemiological cutoff values (ECVs) were applied, where CBPs were not available38,39 (Table S1). In case CBPs absent data, isolates were distributed as a wild-type (WT) or a non-WT (NWT) drug susceptibility phenotype according to the ECVs as determined by the CLSI broth microdilution method35,37.

Definitions

Candidemia was defined as the detection of a species of Candida in the first blood culture of a patient, along with associated clinical signs and symptoms. Regarding age categorization, individuals aged from one day to 17 years were considered pediatric patients, and those 18 to 98 years of age were considered adult patients. Candida infections associated with candidemia were examined, along with the demographic and clinical characteristics of pediatric and adult patients. Laboratory test results were collected at the onset of candidemia. Renal failure was defined as a serum creatinine level above 62 µmol/l for pediatric patients and 104 µmol/l for adult patients. Anemia was defined as a hemoglobin level below 105 g/l. Thrombocytopenia was defined as a platelet count level < 150 × 109/l for pediatric and < 100 × 109/l for adult patients. Hyponatremia was defined as having a serum sodium level < 135 mmol/l and hypernatremia as a serum sodium level > 145 mmol/l. Treatment with antifungal agents was considered empirical when it was initiated before obtaining susceptibility test results. Results were recorded 30 days following the onset of candidemia.

Statistical analysis

The clinical data from the electronic medical records of Shantou Second Affiliated Hospital were extracted into an Excel file (2021) by two independent researchers (SK and LC). The files were cross-checked and compared to remove any possible biases. The outcome variables were presented as relative percentages and absolute values, and quantitative variables were calculated as medians and interquartile ranges. A chi-square test was performed for the univariate analysis of baseline characteristics to test the associations between infections and patients. All statistical analyses and graphical visualization were performed using GraphPad Prism v.8.0.2.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was provided by the Second Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College, Human Research Ethics Committee (Ref. 2022 − 167) following the Declaration of Helsinki criteria. The ethics committee waived patient consent, as all the clinical samples were obtained from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College laboratory for routine work and not for this study.

Results

The distribution of Candida species

A total of 5,095 cases of Candida infection were documented over the 11-year study period, with a significant preponderance of C. albicans isolates (n = 2,863, 56.19%), followed by C. tropicalis (n = 1007, 19.76%), C. glabrata (n = 611, 11.99%), C. parapsilosis (n = 343, 6.73%), and C. krusei (n = 167, 3.27%). The prevalence of Candida species is shown in Table 1. The patients’ median age was 63.5 years (range, one day–98 years). Among the age groups, Candida infections more commonly occurred in adult patients (n = 3,915, 76.8%) than in pediatric patients (n = 1,180, 33.1%). Higher proportions of Candida infections were reported in males (n = 3,026, 59.3%) than in females (n = 2,070, 40.6%). The incidence of Candida species increased over time (Table 1). The incidence of C. albicans increased from 2.1 per 1,000 patients in 2011 to 3.2 in 2021. The medical wards reported the majority of Candida infections (n = 1,306, 25.62%), followed by intensive care units (ICUs; n = 2651, 52.02%), pediatric wards (n = 913, 17.91%), and surgical wards (n = 225, 4.41%).

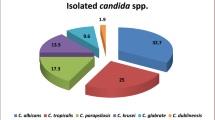

Candidemia

A total of 489 candidemia cases were reported during the study period. C. albicans was predominant (n = 230, 47.0%), followed by C. tropicalis (n = 95, 19.4%), C. glabrata (n = 69, 14.1%), C. parapsilosis (n = 46, 9.40%), and C. krusei (n = 27, 5.52%). The distribution of Candida species is shown in Table 2. Among pediatric patients, a high proportion of infections were caused by C. albicans (n = 37, 54.4%). The proportion of C. glabrata (n = 10, 14.7%) was slightly higher in pediatric than in adult patients, while other NAC species were found more frequently in adult patients. The proportions of other Candida species in different age groups are shown in Fig. 1a. The majority of patients were male (n = 280, 57.2%). Candida species were more frequent in male patients than in female patients, except for C. parapsilosis and C. krusei, with respective ratios of 0.53:1 and 0.68:1. Among hospital departments, the medical wards (n = 207, 42.3%) recorded the highest number of cases, followed by ICUs (n = 151, 30.8%), surgical wards (n = 97, 19.8%), and pediatric wards (n = 34, 6.95%). C. albicans (n = 91, 60.2%) was identified in high proportions in the ICU/pediatric (PICU)/neonatal (NICU) department. Among NAC species, C. tropicalis (n = 58, 28.0%), and C. glabrata (n = 29, 29.8%) were dominant in medical wards and surgical wards, respectively (Fig. 1b).

One or more comorbidities were identified in most patients. Comorbidities in adult patients were significantly more frequent than in pediatric patients (P < 0.05). Thrombocytopenia was more frequent in older patients than in pediatric patients (P < 0.05). The all-cause mortality rates for candidemia were 27 (5.52%), 97 (19.8%), and 125 (25.5%) at 7 days, 30 days, and overall, respectively. The mortality at 30 days was 6 (5.63%) in pediatric patients and 91 (21.7%) in adult patients (P < 0.05; Table 3).

The univariate predictors associated with outcomes of candidemia are listed in Table 4. For pediatric patients with candidemia, the factors of respiratory dysfunction, UTIs, and renal failure were linked with 30-day mortality. For adult patients with candidemia, cardiovascular disease, respiratory dysfunction, pulmonary diseases, central venous catheter, urinary tract catheter, septic shock, mechanical ventilation, and thrombocytopenia were linked with 30-day mortality. The results of an odds ratio analysis for independent risk factors are listed in Table 5. Respiratory dysfunction was an independent risk factor for 30-day mortality in adults and all patients. A central venous catheter, mechanical ventilation, septic shock, and thrombocytopenia were significant factors for 30-day mortality in adults and all patients. The odds ratio for pediatric patients was not analyzed due to the small number of deaths (6/71).

Antifungal susceptibility

The antifungal susceptibility profiles of all Candida species are summarized in Table 6. Among total isolates, itraconazole had relatively high MIC values ranging from 0.12 to 1 for MIC50 and 0.5 to 4 for MIC90. C. parapsilosis had the highest percentage of itraconzole NWT isolates (43/141, 30.4%), followed by C. albicans (524/1880, 27.8%), C. glabrata (55/391 ,14.0%), C. krusei (10/94, 10.6%) and C. tropicalis (4/256, 1.12%). Similarly, fluconazole showed high susceptibility against C. parapsilosis (21.8%), followed by C. albicans (11.9%), C. glabrata (6.31%), and C. tropicalis (3.67%).

The susceptibility profiles of Candida isolates obtained from bloodstream Candida infections (BSCI) were compared with those of non-bloodstream Candida infections (non-BSCI); see Fig. 2. For C. albicans and C. parapsilosis, VRC exhibited higher efficacy in the BSCI group compared to the non-BSCI group (P < 0.05). For C. tropicalis, FCA exhibited higher efficacy in the BSCI than in the non-BSCI group (P > 0.05). Similarly, C. glabrata demonstrated lower susceptibility to ITR and VRC in the BSCI compared to the non-BSCI group (P < 0.05). For C. krusei, FC demonstrated higher efficacy in the BSCI group than in the non-BSCI group. C. krusei showed lower susceptibility to VRC and ITR in the BSCI than in the non-BSCI group (P > 0.05).

Differences in the antifungal susceptibility of isolates obtained from cases of candidemia and non-candidemia. The blue bars represent BSCI isolates, while the green bars represent non-BSCI. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. AmB, amphotericin B; FC, 5-flucytosine; FCA, fluconazole; ITR, itraconazole; VRC, voriconazole; NYS, nystatin.

Discussion

Invasive candidiasis and deep-seated infections largely occur in hospitalized patients. In addition, superficial, oral, and vaginal candidiasis cases have been reported29. In this 11-year retrospective study, we analyzed the distribution, clinical characteristics, underlying comorbidities, risk factors, and antifungal susceptibility profiles of pathogenic Candida. Moreover, we conducted epidemiological comparisons between pediatric and adult patients using data from a tertiary care hospital in Shantou, China. To our knowledge, this is the first epidemiological study comparing the occurrence of candidiasis between pediatric and adult patients in Southern China. The findings provide in-depth information for healthcare workers, thereby contributing to a better understanding and control of candidiasis, especially candidemia.

There was a high prevalence of C. albicans causing candidiasis across all patient age groups. This finding aligns with a recent report that describes a high percentage of C. albicans among patients in South China hospitals18. However, some studies have also reported a high proportion of NCA40. In pediatric patients, C. tropicalis was dominant among NCA, followed by C. glabrata and C. parapsilosis. The epidemiology of Candida species depends on various factors, including region, patient type, and diagnostic center. Notably, a high proportion of C. tropicalis compared to C. glabrata has been reported in studies from India, Canada, China, and Italy4,20,21,41,42. C. tropicalis is also highly prevalent, causing candidemia in pediatric and adult patients. In pediatric patients (0–28 days), C. glabrata was identified in a relatively high proportion of patients, as previously reported in Southwest China. In patients < 65–98 years old, there was a high proportion of C. parapsilosis, followed by C. glabrata and C. tropicalis.

In cases of candidemia, a high prevalence of C. albicans has been reported in different regions of China and other Asian countries such as Iran, Kuwait, Japan and Saudia arabia. Among NCA in candidemia patients, a significant prevalence of C. tropicalis has similarly been reported in regions of China at similar latitudes as in our study18,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51. Reports from countries and regions such Iran, Korea, Indonesia, North America, Southern Europe, eastern China, southwestern China, northeastern China, and northern Taiwan, have consistently reported a significant prevalence of C. tropicalis among candidemia patients20,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62. The regional variation in Candida species prevalence in candidemia may be due to differences in climate, healthcare practices, antifungal use, patient demographics, diagnostic capabilities, hygiene practices, or globalization. These factors collectively influence species distributions and resistance patterns.

Candida infections were slightly more common in males than in females. Similar population distributions have been reported in other studies in China63. Conversely, studies from Ethiopia have reported a higher number of Candida infections in women than in men18,64. Although the variation in the frequency of candidiasis between men and women may be attributed to anatomical and physiological differences specific to each sex18,65, the reasons for the high percentage of Candida infections in men in China remain unclear. The medical wards documented the highest number of candidemia cases, consistent with a previously published study20. However, most studies have reported the highest case numbers in ICUs66,67,68,69. One possible reason concerns the demographic characteristics of the inpatients in our hospital, most of whom had more than two underlying diseases and were hospitalized in medical wards. However, the incidence of candidemia in ICUs is high in most studies.

According to our data, sex ratio, hematologic malignancies, liver disease (acute or chronic), malnutrition, mechanical ventilation, skin barriers, surgery, tuberculosis, neurological diseases, UTIs, central venous catheters, anemia, renal failure, hyponatremia, hypernatremia, and seven-day and total mortality rate were not significantly different between pediatric and adult patients. Oral cavities were the only underlying comorbidity more frequent in pediatric than in adult patients. Underlying comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, gastrointestinal pathology, respiratory dysfunction, and pulmonary diseases, were more frequent in adult patients than pediatric patients. Several other studies from China have also reported candidemia patients with comorbidities20,21,70.

A central venous catheter, septic shock, and ICU admission were more common risk factors in adult patients than in pediatric patients (Table 3). The prevalence of Candida species on the skin of the hands and the ability to transfer to catheters are widely recognized71,72. The present findings suggest that healthcare personnel may contribute to the prevalence of various forms of invasive candidiasis through horizontal transmission of Candida species. Laboratory findings showed that only thrombocytopenia was in a higher proportion in adult patients compared to pediatric patients. Previous studies have identified thrombocytopenia as an independent risk factor for death in patients with candidemia28.

The 30-day mortality rate between pediatric and adult patients was dissimilar to the values from previous reports in China18. The univariate predictors of outcomes indicated pediatric patients had only three significant predictors. The adult patients had eight significant predictors, including respiratory dysfunction and septic shock, similar to a previous study from southwest China. The predictors for outcome included a central venous catheter, mechanical ventilation, thrombocytopenia, and a urinary tract catheter (Table 4). However, further epidemiological research is needed for confirmation, as other studies have not reached firm conclusions.

We compared the susceptibility profiles of Candida isolates obtained from BSCI and non-BSCI (Fig. 2). For C. albicans, the obtained isolates from BSCI were relatively more susceptible to all drugs than non-BSCI except for ITR. However, for C. albicans, the susceptibility profile to azole was similar to that in previous reports from China18. C. parapsilosis and C. tropicalis exhibited high susceptibility to the drugs VRC and FCA in BSCI compared to non-BSCI. Similarly, C. glabrata and C. krusei demonstrated lower susceptibility to azole in BSCI compared to non-BSCI. The continued recommendation of empirical prophylactic treatments by prescribers may be the cause of the lowered susceptibilities of the NCA-causing candidemia isolates.

The study has several limitations. The results may not apply to all patients with invasive candidiasis or to other institutions, as this was a retrospective study conducted at a single hospital. The distribution and prevalence of candidiasis or candidemia can vary widely depending on the institution. Unfortunately, our hospital did not have any data on echinocandins because of the clinical microbiology laboratory’s technical limitations and the impact of hospital policies. However, the study’s epidemiological findings can help develop strategies for improving the hospital’s management of invasive candidiasis.

Conclusion

This study identified the epidemiological patterns and incidence of candidiasis, especially candidemia, in a developing region of China. In this study, we reported the distribution, risk factors, and susceptibility to antifungal agents of Candida infections. C. tropicalis was more prevalent than C. glabrata in patients with candidemia. Respiratory dysfunction, pulmonary diseases, septic shock, and thrombocytopenia were independent risk factors for 30-day mortality. Regarding bloodstream infections compared with non-bloodstream infections (non-BSCI), AMB was effective (100%) against all tested isolates. The epidemiological findings of the study are valuable for developing strategies to improve hospital management and control of candidiasis.

Data availability

All the data are presented in the manuscript; any raw data can be available by request to the first author (email; sabir_khan182@yahoo.com).

Abbreviations

- NAC:

-

Non-albicans Candida

- IC:

-

Invasive candidiasis

- CVC:

-

Central Venous Catheterization

- MALDI-TOF-MS:

-

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry

- AMB:

-

amphotericin B

- FC:

-

flucytosine

- FCA:

-

fluconazole

- ITR:

-

itraconazole

- VRC:

-

voriconazole

- ICU:

-

intensive care unit

- PICU:

-

pediatric intensive care unit

- NICU:

-

neonatal intensive care unit

References

Fly, J. H., Kapoor, S., Bobo, K. & Stultz, J. S. Updates in the Pharmacologic prophylaxis and treatment of invasive candidiasis in the pediatric and neonatal intensive care units: Updates in the Pharmacologic prophylaxis. Curr. Treat. Options Infect. Dis. 14, 15–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40506-022-00258-z (2022).

Pana, Z. D., Roilides, E., Warris, A., Groll, A. H. & Zaoutis, T. Epidemiology of invasive fungal disease in children. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 6, S3–s11. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpids/pix046 (2017).

Lortholary, O. et al. The risk and clinical outcome of candidemia depending on underlying malignancy. Intensive Care Med. 43, 652–662. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-017-4743-y (2017).

Liu, S. H., Mitchell, H. & Nasser Al-Rawahi, G. Epidemiology and associated risk factors for candidemia in a Canadian tertiary paediatric hospital: An 11-year review. J. Association Med. Microbiol. Infect. Disease Can. = J. Officiel De l’Association Pour La. Microbiologie Medicale Et L’infectiologie Can. 8, 29–39. https://doi.org/10.3138/jammi-2022-0021 (2023).

Kaur, H. & Chakrabarti, A. Strategies to reduce mortality in adult and neonatal candidemia in developing countries. J. fungi (Basel Switzerland). https://doi.org/10.3390/jof3030041 (2017).

Nucci, M. et al. Epidemiology of candidemia in Latin America: A laboratory-based survey. PloS One. 8, e59373. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0059373 (2013).

Gjylameti¹, N., Kraja, D., Koraqi¹, A., Basholli¹, B. & Sula, H. The Incidence of Invasive Candidiasis and the Risk Factors at the Patients of ICU at University Hospital Center Mother Teresa Tirana, Albania.

Sobel, J. D. & Candidiasis Diagnosis Treat. Fungal Infections, 101–117 (2015).

Pfaller, M. A. & Diekema, D. J. Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis: A persistent public health problem. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 20, 133–163. https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.00029-06 (2007).

McCarty, T. P., White, C. M. & Pappas, P. G. Candidemia and invasive candidiasis. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 35, 389–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idc.2021.03.007 (2021).

Alhadidi, A. et al. Risk factors and epidemiological features of Candida septicemia in neonatal unites at King Hussein medical center. JRMS 25, 37–45 (2018).

Seyoum, E. Species of yeasts identified from different clinical samples addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Archives Epidemiol. Public. Health Res. 1, 73–79 (2022).

Mantadakis, E., Pana, Z. D. & Zaoutis, T. Candidemia in children: Epidemiology, prevention and management. Mycoses 61, 614–622. https://doi.org/10.1111/myc.12792 (2018).

Blyth, C. C. et al. Not just little adults: candidemia epidemiology, molecular characterization, and antifungal susceptibility in neonatal and pediatric patients. Pediatrics 123, 1360–1368. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-2055 (2009).

Fakhim, H. et al. Candida Africana vulvovaginitis: Prevalence and geographical distribution. J. Mycol. Med. 30, 100966. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mycmed.2020.100966 (2020).

Fakhim, H. et al. Comparative virulence of Candida auris with Candida haemulonii, Candida glabrata and Candida albicans in a murine model. Mycoses 61, 377–382. https://doi.org/10.1111/myc.12754 (2018).

Gonzalez-Lara, M. F. & Ostrosky-Zeichner, L. Invasive candidiasis. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 41, 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1701215 (2020).

Bilal, H. et al. Six-Year retrospective analysis of epidemiology, risk factors, and antifungal susceptibilities of candidiasis from a tertiary care hospital in South China. Microbiol. Spectr. 11, e0070823. https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.00708-23 (2023).

Lai, M. Y. et al. Risk factors and outcomes of recurrent candidemia in children: Relapse or Re-Infection? J. Clin. Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8010099 (2019).

Zeng, Z. et al. A seven-year surveillance study of the epidemiology, antifungal susceptibility, risk factors and mortality of candidaemia among paediatric and adult inpatients in a tertiary teaching hospital in China. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 9, 133. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-020-00798-3 (2020).

Zheng, Y. J. et al. Epidemiology, species distribution, and outcome of nosocomial Candida spp. Bloodstream infection in Shanghai: An 11-year retrospective analysis in a tertiary care hospital. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 20, 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-021-00441-y (2021).

Revie, N. M., Iyer, K. R., Robbins, N. & Cowen, L. E. Antifungal drug resistance: Evolution, mechanisms and impact. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 45, 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mib.2018.02.005 (2018).

Pfaller, M. et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of candidemia in 3648 patients: Data from the prospective antifungal therapy (PATH Alliance®) registry, 2004–2008. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 74, 323–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.10.003 (2012).

Puig-Asensio, M. et al. Impact of therapeutic strategies on the prognosis of candidemia in the ICU. Crit. Care Med. 42, 1423–1432. https://doi.org/10.1097/ccm.0000000000000221 (2014).

Grim, S. A. et al. Timing of susceptibility-based antifungal drug administration in patients with Candida bloodstream infection: correlation with outcomes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67, 707–714. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkr511 (2012).

Arendrup, M. C., Patterson, T. F. & Multidrug-Resistant Candida Epidemiology, molecular mechanisms, and treatment. J. Infect. Dis. 216, S445–s451. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jix131 (2017).

Castanheira, M., Messer, S. A., Rhomberg, P. R. & Pfaller, M. A. Antifungal susceptibility patterns of a global collection of fungal isolates: results of the SENTRY Antifungal Surveillance Program Diagnos. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 85, 200–204, (2013).

Jia, X., Li, C., Cao, J., Wu, X. & Zhang, L. Clinical characteristics and predictors of mortality in patients with candidemia: A six-year retrospective study. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Diseases: Official Publication Eur. Soc. Clin. Microbiol. 37, 1717–1724. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-018-3304-9 (2018).

Bilal, H. et al. Distribution and antifungal susceptibility pattern of Candida species from Mainland China: A systematic analysis. Virulence 13, 1573–1589 (2022).

Bassetti, M., Peghin, M. & Timsit, J. F. The current treatment landscape: candidiasis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 71, ii13–ii22 (2016).

Rüping, M. J., Vehreschild, J. J. & Cornely, O. A. Antifungal treatment strategies in high risk patients. Mycoses 51, 46–51 (2008).

Pappas, P. G. et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 update by the infectious diseases society of America. Clin. Infect. Diseases: Official Publication Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 62, e1–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ933 (2016).

Keighley, C. et al. Consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of invasive candidiasis in haematology, oncology and intensive care settings, 2021. Intern. Med. J. 51 Suppl 7, 89–117. https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.15589 (2021).

Li, F. et al. Surveillance of the prevalence, antibiotic susceptibility, and genotypic characterization of invasive candidiasis in a teaching hospital in China between 2006 to 2011. BMC Infect. Dis. 13, 353. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-13-353 (2013).

Wayne, P. Performance standards for antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. CLSI Supplement CLSI Supplement, M60 (2017).

Espinel-Ingroff, A. & Turnidge, J. The role of epidemiological cutoff values (ECVs/ECOFFs) in antifungal susceptibility testing and interpretation for uncommon yeasts and moulds. Revista Iberoamericana De Micologia. 33, 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riam.2016.04.001 (2016).

Carvalhaes, C. G., Klauer, A. L., Rhomberg, P. R., Pfaller, M. A. & Castanheira, M. Evaluation of Rezafungin provisional CLSI clinical breakpoints and epidemiological cutoff values tested against a worldwide collection of contemporaneous invasive fungal isolates (2019 to 2020). J. Clin. Microbiol. 60, e02449–e02421 (2022).

Wayne, P. Performance standards for antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. CLSI Supplement CLSI Supplement, M59 (2018).

Cantón, E. et al. Comparison of three statistical methods for Establishing tentative wild-type population and epidemiological cutoff values for echinocandins, amphotericin B, Flucytosine, and six Candida species as determined by the colorimetric sensititre YeastOne method. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50, 3921–3926. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.01730-12 (2012).

Deorukhkar, S. C., Saini, S. & Mathew, S. Non-albicans Candida infection: An emerging threat. Interdisciplinary Perspect. Infect. Dis.. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/615958 (2014).

Yesudhason, B. L. & Mohanram, K. Candida tropicalis as a predominant isolate from clinical specimens and its antifungal susceptibility pattern in a tertiary care hospital in Southern India. J. Clin. Diagn. Research: JCDR. https://doi.org/10.7860/jcdr/2015/13460.6208 (2015).

Bedini, A. et al. Epidemiology of candidaemia and antifungal susceptibility patterns in an Italian tertiary-care hospital. Clin. Microbiol. Infection: Official Publication Eur. Soc. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 12, 75–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01310.x (2006).

Wu, J. Q. et al. Epidemiology and risk factors for non-Candida albicans candidemia in non-neutropenic patients at a Chinese teaching hospital. Med. Mycol. 49, 552–555. https://doi.org/10.3109/13693786.2010.541948 (2011).

Zhang, X. B. et al. Retrospective analysis of epidemiology and prognostic factors for candidemia at a hospital in China, 2000–2009. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 65, 510–515 (2012).

Ma, C. F. et al. Surveillance study of species distribution, antifungal susceptibility and mortality of nosocomial candidemia in a tertiary care hospital in China. BMC Infect. Dis. 13, 337. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-13-337 (2013).

Wang, H. et al. Antibiotics exposure, risk factors, and outcomes with Candida albicans and non-Candida albicans candidemia. Results from a multi-center study. Saudi Med. J. 35, 153–158 (2014).

Xiao, M. et al. Five-Year National surveillance of invasive candidiasis: species distribution and Azole susceptibility from the China hospital invasive fungal surveillance net (CHIF-NET) study. J. Clin. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.00577-18 (2018).

Khan, Z. et al. Changing trends in epidemiology and antifungal susceptibility patterns of six bloodstream Candida species isolates over a 12-year period in Kuwait. PLoS One. 14, e0216250. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216250 (2019).

Guo, L. N. et al. Epidemiology and antifungal susceptibilities of yeast isolates causing invasive infections across urban Beijing, China. Future Microbiol. 12, 1075–1086. https://doi.org/10.2217/fmb-2017-0036 (2017).

Arastehfar, A. et al. Epidemiology of candidemia in Shiraz, Southern Iran: A prospective multicenter study (2016–2018). Med. Mycol. 59, 422–430. https://doi.org/10.1093/mmy/myaa059 (2021).

Morii, D. et al. Distribution of Candida species isolated from blood cultures in hospitals in Osaka, Japan. J. Infect. Chemother. 20, 558–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiac.2014.05.009 (2014).

Almirante, B. et al. Epidemiology and predictors of mortality in cases of Candida bloodstream infection: results from population-based surveillance, Barcelona, Spain, from 2002 to 2003. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43, 1829–1835. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.43.4.1829-1835.2005 (2005).

Asmundsdóttir, L. R., Erlendsdóttir, H. & Gottfredsson, M. Increasing incidence of candidemia: results from a 20-year nationwide study in Iceland. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40, 3489–3492. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.40.9.3489-3492.2002 (2002).

Garbino, J. et al. Secular trends of candidemia over 12 years in adult patients at a tertiary care hospital. Medicine 81, 425–433. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005792-200211000-00003 (2002).

Fernández-Ruiz, M. et al. Candida tropicalis bloodstream infection: incidence, risk factors and outcome in a population-based surveillance. J. Infect. 71, 385–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2015.05.009 (2015).

Muñoz, P. et al. Candida tropicalis fungaemia: incidence, risk factors and mortality in a general hospital. Clin. Microbiol. Infection: Official Publication Eur. Soc. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 17, 1538–1545. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03338.x (2011).

Vaezi, A. et al. Epidemiological and mycological characteristics of candidemia in Iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Mycol. Med. 27, 146–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mycmed.2017.02.007 (2017).

Zhang, W., Song, X., Wu, H. & Zheng, R. Epidemiology, species distribution, and predictive factors for mortality of candidemia in adult surgical patients. BMC Infect. Dis. 20, 506. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05238-6 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. Epidemiology, antifungal susceptibility, risk factors, and mortality of persistent candidemia in adult patients in China: A 6-year multicenter retrospective study. BMC Infect. Dis. 23, 369. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-023-08241-9 (2023).

Won, E. J., Sung, H. & Kim, M. N. Clinical characteristics of candidemia due to Candida parapsilosis with serial episodes: insights from 5-Year data collection at a tertiary hospital in Korea. J. Fungi (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/jof10090624 (2024).

Wu, Y. M. et al. Risk factors and outcomes of candidemia caused by Candida parapsilosis complex in a medical center in Northern Taiwan. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 90, 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2017.10.002 (2018).

Veronica, W., Neneng, S., & Nicolaski, L. Changing pattern of non & albicans candidemia: Occurence and susceptibility profile in an indonesian secondary teaching hospital. Afr. J. Infect. Dis. 18, 5–9, doi:https://doi.org/10.21010/Ajidv18n2S.2 (2024).

Bilal, H. et al. Antifungal susceptibility pattern of Candida isolated from cutaneous candidiasis patients in Eastern Guangdong region: A retrospective study of the past 10 years. Front. Microbiol. 13, 981181. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.981181 (2022).

Moges, B., Bitew, A. & Shewaamare, A. Spectrum and the in vitro antifungal susceptibility pattern of yeast isolates in Ethiopian HIV patients with oropharyngeal candidiasis. Int. J. Microbiol. . https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/3037817 (2016).

Hsu, J. F. et al. Comparison of the incidence, clinical features and outcomes of invasive candidiasis in children and neonates. BMC Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3100-2 (2018).

Filioti, J., Spiroglou, K. & Roilides, E. Invasive candidiasis in pediatric intensive care patients: Epidemiology, risk factors, management, and outcome. Intensive Care Med. 33, 1272–1283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-007-0672-5 (2007).

Singhi, S., Rao, D. S. & Chakrabarti, A. Candida colonization and candidemia in a pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr. Crit. Care Medicine: J. Soc. Crit. Care Med. World Federation Pediatr. Intensive Crit. Care Soc. 9, 91–95. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pcc.0000298643.48547.83 (2008).

Dorofaeff, T. & Mohseni-Bod, H. & Cox, P. N. Infections in the PICU. Textbook Clin. Pediatr., 2537 (2012).

Miranda, L. N. et al. Candida colonisation as a source for candidaemia. J. Hosp. Infect. 72, 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2009.02.009 (2009).

Silva, J. J. D. et al. Candida species biotypes in the oral cavity of infants and children with orofacial clefts under surgical rehabilitation. Microb. Pathog. 124, 203–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2018.08.042 (2018).

Mavor, A. L., Thewes, S. & Hube, B. Systemic fungal infections caused by Candida species: Epidemiology, infection process and virulence attributes. Curr. Drug Targets. 6, 863–874. https://doi.org/10.2174/138945005774912735 (2005).

Seddiki, S. M. et al. Assessment of the types of catheter infectivity caused by Candida species and their biofilm formation. First study in an intensive care unit in Algeria. Int. J. Gen. Med. 6, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijgm.s38065 (2013).

Acknowledgements

All the Authors are thankful to the Second Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College for supporting this study.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study is funded by the Second Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College to S.K and his mentor Y.Z.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z; and S.K; methodology, S.K; L.C; and Y.Z; software, S.K; and H.B; validation, M.N.K; B.H; and W.F; formal analysis, Q.W; and B.H; investigation, H.B; and D.Z; resources, Y.Z; and L.C; data curation, F.Y; X.W; and L.C; writing—original draft preparation, S.K.; writing—review and editing, S.K., and M.N.K; visualization, J.W; C.M; and L.L; supervision, Y.Z; project administration, L.C; and Y.Z; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was provided by the Second Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College, Shantou, Human Research Ethics Committee (Ref; 2022 − 167) following the Declaration of Helsinki criteria. The ethical committee waived consent forms from the patients as all the clinical samples were obtained from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College, hospital laboratory as routine work and not for this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

Statement.

Patient consent was waived as we get data from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College, Shantou, surveillance system as a secondary source; no patient image or figure is involved.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, S., Cai, L., Bilal, H. et al. An 11-Year retrospective analysis of candidiasis epidemiology, risk factors, and antifungal susceptibility in a tertiary care hospital in China. Sci Rep 15, 7240 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92100-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92100-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Evaluation of an Antifungal Agent Against Nakaseomyces Glabratus in the in Vivo Model Galleria Mellonella

Current Microbiology (2026)

-

High co-infection burden and ICU-specific pathogen profiles in pediatric Candida albicans respiratory infections: a large-scale tNGS analysis

European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases (2025)