Abstract

The widespread distribution of riprap in estuarine mudflats has brought significant challenges to the penetration construction of steel casings. To reveal the effects of casing length, diameter and wall thickness on the stress and deformation, as well as the deformation characteristics and mechanical behaviors of the steel casing during the sinking process, the paper utilizes finite element method to construct a three-dimensional numerical model of the collision between steel casings and riprap in mudflat. The research results indicate that longer steel casing has better crushing effect on the riprap, smoother deflection curve of the casing body and smaller deformation at the casing end under the same casing diameter and wall thickness conditions. Under the same casing length and wall thickness conditions, the steel casing with a larger diameter has a better crushing effect on the riprap and smaller deformation at the casing end. As the casing diameter increases, the stress values of S11 and S33 in the soil at the casing end gradually decrease, and the range of stress concentration gradually increases. This study can provide a theoretical basis for the design and construction of steel casings in the riprap environment of the mudflat near the estuaries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

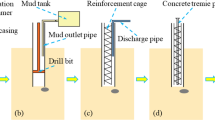

In the early years, to reduce the damage of the bank feet caused by the scouring of the tide and surge at the estuary bank slopes, a large number of stones were often thrown on the nearshore mudflat to form riprap protection. After long-term scouring and silting, most riprap will sink into the mud, forming a relatively continuous riprap layer below the mudflat surface. During the construction process of the steel casings, local deformation may occur when encountering the riprap, and even cause the casings to buckle and fail, resulting in a significant decrease in the quality and efficiency of the pouring casing construction. Since the mechanical behaviors and deformation process of the steel casings when they meet the riprap occur in the sludge, it is difficult to observe through test methods, thus it is of great significance to study the deformation characteristics and mechanical behaviors of the steel casings during the construction of offshore mudflat by constructing a numerical model to improve the engineering quality and construction efficiency.

Scholars have conducted some researches on the physical and mechanical properties of steel casing during the sinking process, accumulating a wealth of useful experience. In terms of theoretical research, Holeyman et al.1 used a simplified one-dimensional wave equation to analyze how the axial force caused by a circular boulder embedded below the tip of a steel casing leads to plastic deformation at the end. They evaluated how axial stress under a symmetrical boulder triggers plastic strain in the casing and explored the effects of boulder size and rock physical and mechanical properties on this phenomenon. Dai et al.2 introduced the Hoek-Brown rock strength failure criterion and established a static equilibrium equation for deriving the minimum rock embedding depth of rock socketed piles. Nicolini and Gargarella3 evaluated the effect of collision between steel casing and spherical flint in soil layers on the buckling of the casing end, and proposed reducing the driving energy to avoid damage to the casing tip. Tomczyk et al.4 proposed a new mathematical mean non asymptotic model and asymptotic model for thin elastic cylindrical shells. The tolerance averaging technique was used to transform the highly oscillatory and discontinuous coefficients in the initial equation into continuous and slowly changing coefficients. The results showed that the tolerance model could not only analyze critical forces independent of individual elements, but also revealed critical forces related to individual elements, providing a new theoretical framework for the stability analysis of shells. Yoshihiro and Atsushi5 studied the buckling behavior of long shell structures under earthquake induced liquefaction support force reduction through theoretical derivation, and proposed a buckling load theoretical equation considering end constraints and soil stiffness distribution.

In terms of experimental research, Ko and Jeong6 conducted on-site vertical load tests on steel casing with diameters of 508.0 mm, 711.2 mm and 914.4 mm, respectively. Their study results showed that the internal frictional resistance of the steel casing was mainly concentrated at the bottom, accounting for 18–34% of the soil plug height, and the ratio of the internal frictional resistance and the annular resistance at the casing end to the total bearing capacity decreased with the increasing diameter. Brown et al.7 conducted reverse cyclic bending tests on reinforced concrete filled steel tubes (RCFST) with different diameter to thickness ratios, and studied the maximum strain value at which local buckling occurred on the tube wall. They found that larger diameter to thickness ratios would lead to premature local buckling of the steel casings. Nietiedt et al.8 conducted experiment on the eccentric collision of thin-walled steel pipes passing through sandy soil layers with large-sized pebbles. The results showed that the collision of thin-walled steel pipes with large-sized pebbles and the large pile tip resistance would cause compression buckling at the pipe bottom. Han et al.9 conducted on-site experimental research on the vertical bearing characteristics of a steel pipe with a length of 114 m and a diameter of 2.4 m, based on offshore wind power engineering. The results showed that the variation curve of the end resistance of the large-diameter and ultra long steel pipe with the top load was generally in an “S” shape. The slope of the variation curve of the end resistance with the top load during the early and late stages of loading was smaller than that of the variation curve of the end resistance with the top load during the middle stage of loading. Lu et al.10 studied the bearing characteristics and deformation behavior of recyclable steel pipe sleeves during excavation of foundation pits through field experiments. The results showed that the maximum strain of the casing occurred at 0.62 H below the surface (H is the sinking depth), and the maximum strain value was at 0.23 H.

In terms of numerical simulation research, Bakroon et al.11 simplified the steel casing as a shell element and simulated its buckling behavior using the Multi Material Lagrange - Euler Method in ABAQUS software. The model was validated through sand tests on steel pipes under vibration loads, and the buckling performance of steel pipes during installation was evaluated under soil heterogeneity and casing defects. The results showed that the initial defects not only accelerated the buckling process of steel pipes, but also changed their buckling modes. Wang et al.12 studied the soil plug effect under different diameters based on the CEL method in ABAQUS, and found that the smaller the diameter, the more obvious the soil plug effect. Tang13 used finite element method to establish a steel pipe - soil model to study the sinking process of steel pipes, and the research results showed that as the sinking depth continued to increase, the maximum stress of Mises also continued to increase. When the sinking depth was constant, the stress value of the casing decreased continuously with the increasing diameter. Liu et al.14 used finite element method to study the influencing factors of the variation of internal friction resistance of micro steel pipes in clay, and analyzed the results of centrifuge experiments. The research results indicated that as the steel pipe diameter increased, the soil pressure inside also increased, and the lateral friction resistance also rose. Shu et al.15 studied the effect of soil plugs on the vertical bearing capacity of large-diameter steel pipe piles through numerical simulations, and their results showed that the frictional resistance inside the soil plug had a certain impact on the vertical bearing capacity of the pile, and the pile’s internal frictional resistance did not exceed 30% of its external frictional resistance. Zhang et al.16 studied the effect of impact velocity on the buckling mode exhibited by thin-walled cylindrical shells. The results showed that the dynamic buckling load of cylindrical shells was negatively correlated with their diameter to thickness ratio and positively correlated with impact velocity. As the impact velocity increased, the buckling mode of the thin shell changed from a diamond like pattern to a distinct circular pattern.

Although the existing researches have played a positive role in the engineering application and technical promotion of steel casings, most of the studies focus on homogeneous soil layers, lacking in-depth researches on the mechanics and deformation behavior of steel casings during sinking in heterogeneous soil layers, especially in the environment with riprap layers in estuarine mudflats. The stress distribution and deformation mechanism of the sinking process of the steel casings in the riprap layer are not fully understood. The paper takes the construction process of steel casings in Shaoxing Seawall Project and Longgang Seawall Project of Zhejiang Province in China as case studies, the finite element software ABAQUS was used to conduct three-dimensional numerical simulation of the sinking process of steel casings in heterogeneous soil layers containing riprap. The effects of different casing lengths, diameters, wall thicknesses and other factors on the stress and deformation of steel casings were studied, and the wall thickness of steel casings was optimized and analyzed. This study can provide theoretical basis for the design and construction of steel casings in similar construction environments.

Overview of the projects

The seawall in Keqiao District, Shaoxing City is located on the south bank of Jianshan River Bay on the Qiantang River and on the left bank of Cao’e River estuary. It starts from the Dongjiang Sluice at the junction of Xiaoshan and Shaoxing, and ends at the left bank approach embankment of Cao’e River estuary, with a total length of 5.85 km. It is an important part of the seawall on the south bank of Qiantang River. The seawall was first built between 2010 and 2011, with an original fortification standard of once every 100 years. However, due to severe erosion of the beach and riprap protection, damage and cracks to the apron, and partial detachment of the protective layer of the wave wall, the upgrading project has been launched recently. After the completion of the project, its flood control level will be raised to once every 300 years, and 14 spur dikes will be set up to prevent erosion. The Longgang Seawall Project is located on the south bank of the Ao River estuary, with the main task of moisture prevention and drainage, while also improving and enhancing the coastal urban landscape. When these seawall projects are reinforced, pile foundations need to be used to treat the foundation. In soft soil and water rich environments, using steel casings to stabilize the hole walls, prevent collapse, isolate groundwater, etc. has become an effective engineering measure. The location and steel casing construction site of the Qiantang River estuary and Ao River estuary project areas are shown in Fig. 1.

Typical construction locations of river estuary steel casings (The satellite imagery was obtained from 91 Map Free Version, Version (19.4.0), available at https://mydown.yesky.com/pcsoft/37063219.html). (a) Map of China; (b) Map of Zhejiang Province; (c) Ao River estuary; (d) Qiantang River estuary; (e) Construction site of the steel casing for the Longgang seawall project; (d) Construction site of the steel casing for the Shaoxing seawall project.

Materials and methods

Numerical model

The steel casings will cause significant plastic deformation to the soil during penetration, resulting in soil squeezing effect17,18,19,20,21. In traditional Lagrangian analysis, nodes are fixed inside the material, and the deformation of the material is described by the deformation of the element. The material boundary is consistent with the element boundary, and the material is attached to the grid. When the object undergoes large deformation, the grid needs to be regenerated, which requires a large amount of computation. In the Euler method, the mesh is fixed, and object deformation can cause distortion and distortion of the mesh, requiring repair of the mesh22,23,24. The Lagrange–Euler method (CEL) divides objects into two parts, namely Eulerian grids and Lagrangian grids. Eulerian grids are used to describe fluid media, while Lagrangian grids are used to describe solid media, which can effectively handle large deformation problems of grids25,26,27. In the application of CEL method to simulate the sinking process of steel casings, the soil is regarded as a fluid that can flow freely, and Eulerian mesh is used for simulation. This processing method is suitable for describing the large deformation and flow characteristics of soil, avoiding the problem of grid distortion caused by large deformation. Therefore, this paper intends to use the Lagrange - Euler method and dynamic display analysis steps in the finite element analysis software (Abaqus Unified FEA, Version 6.20-1, Dassault Systèmes, 2020, and its details can be accessed at https://www.3ds.com/products-services/simulia/products/abaqus/) for modeling and calculation. Steel casings and riprap are considered solid materials and simulated using Lagrangian mesh. The deformation of the Euler mesh on the soil surface is shown in Fig. 2.

Soil constitutive model

The muddy soil below the sea surface has characteristics of high porosity, high water content and low permeability due to its special sedimentary environment28,29,30. During rapid construction, it is often believed that this type of foundation soil is in a saturated and undrained state31. The Mohr - Coulomb model is used to describe the soil in this state, and its yield surface function is as follows32,33,34,35,36:

where \(q\) is Mises equivalent stress, kPa; \(p\) is the hydrostatic pressure, kPa; \(\phi\) is the internal friction angle, the inclination angle on the Mohr - Coulomb yield surface on the \(q-p\) stress plane, °; \(c\) is the cohesion, kPa; \(\:{R}_{mc}({\Theta\:},\phi\:)\:\)is the correction factor for generalized shear stress used to control the shape of the yield surface in the plane, expressed as:

where \(\varTheta\:\) is the extreme deviation angle, °, \(\text{cos}\left(3\varTheta\:\right)=\frac{{r}^{3}}{{q}^{3}}\), wherein, \(r\) is the third deviatoric stress invariant, kPa.

The Mohr-Coulomb yield surface has sharp corners, and when both the plastic potential surface and the yield surface occur at the sharp corners, the plastic flow direction is not the only phenomenon, resulting in tedious numerical calculations and slow convergence. To avoid this phenomenon, the following elliptic function is used as the plastic potential surface, expressed as:

where \(\:\psi\:\) is the shear dilation angle, °; \(\:c{|}_{0}\) is the initial cohesive force, kPa; \(\:\epsilon\:\) is the eccentricity on the meridian plane, usually taken as 0.1; \(\:{R}_{mw}\) is the improved correction coefficient, expressed as:

where\(\:\:e\) is the eccentricity on the \(\:{\uppi\:}\) plane, used to control the shape of the plastic potential surface with \(\:\varTheta\:\)=0 - \(\:{\uppi\:}\)/3 on the surface, with a value range of 0.5–1.0, calculated by the following equation:

Constitutive model of riprap

The material for riprap is mostly granite, which has high strength. Therefore, when the steel casing penetrates the stone, it not only deforms itself, but also often causes penetration damage to the rock. To simulate the shear stress of the steel casing acting on rock to reach the yield strength of the rock and cause shear failure, the linear Drucker–Prager yield criterion is used to describe the yield behavior of rock in the calculation process. The expression of the yield surface is as follows37,38:

where \(\:{\uptau\:}\) is the shear strength of the material as deviatoric stress, MPa, \(\:{\uptau\:}=\frac{\text{q}}{2}\left[1+\frac{1}{\text{k}}-(1-\frac{1}{\text{k}}){\left(\frac{\text{r}}{\text{q}}\right)}^{3}\right]\), among them, \(\:\text{k}\) is the ratio of triaxial tensile strength to triaxial compressive strength used to control the shape of the yield surface on the \(\:{\uppi\:}\) plane, and in the calculation, \(\:\text{k}\) is assumed to be 1.0.

Steel casing simulation element

To simulate the buckling form of the casing more accurately, this paper establishes a benchmark model to evaluate the influence of different element types on the calculation results of the critical stress of the thin-walled steel casing buckling under uniform axial load compression. A thin-walled steel casing model with a length of 0.25 m was established using shell (S4R) elements and solid elements. The material used for the casing is Q235 steel, with its physical and mechanical parameters shown in Table 1. At the same time, constraints are set on the displacement and rotation in the horizontal and vertical directions at the bottom, as well as the displacement and rotation in the horizontal direction at the top. A distributed axial compression load of 100 kN is applied vertically downwards at the top, as shown in Fig. 3.

In theory, the critical uniform axial stress value which causes buckling of the steel casing is as follows39:

where \(\:E\) is the elastic modulus, GPa; \(\:t\) is the shell thickness, m; \(\:R\) is the radius of the shell, m; \(\:v\) is Poisson’s ratio.

According to Eq. (7), the equation for solving the buckling bearing capacity line load of cylindrical thin shells is as follows:

In the nonlinear buckling “Buckle” analysis step of ABAQUS software, the characteristic value, namely the buckling load coefficient, can be directly obtained through calculation. This coefficient represents the proportional factor of the given load. Therefore, the buckling load of a cylindrical thin shell can be solved by the following equation:

where \(\:\lambda\:\) is the eigenvalue; \(\:P\) represents the applied external load, kN.

Using the minimum eigenvalue as the benchmark for comparative analysis, the corresponding critical buckling stress can be deduced based on Eqs. (7), (8) and (9), and compared with the classical solution. The buckling modes generated by two types of elements are shown in Fig. 4, and their corresponding characteristic values and critical buckling stresses are shown in Table 2.

As shown in Fig. 4, increasing the number of grids can improve the accuracy of solid element calculation results and bending shapes. The eigenvalues gradually approach the classical solution as the number of grids in the thickness direction increases. However, an increase in the number of grids will greatly increase the time required for computation. The number of grids for the shell element casing and the solid element casing of the one-layer grid are 6300 and 6550, respectively. Although the number of grids is similar, the accuracy of the calculation results for the solid element of the one-layer grid is much lower than that of the shell element. The number of solid element cylindrical grids in the five-layer grid is 32,250 to achieve calculation accuracy similar to that of shell elements. Therefore, in addition to accurately capturing the bending phenomenon of materials, shell elements can also reduce the number of mesh and degrees of freedom in the model, thereby improving computational efficiency.

Circumferential critical stress of steel casings

When the stress acting on the casing end is greater than its critical stress, the casing end may undergo curling deformation. The critical stress of the steel casing is divided into axial critical stress and circumferential critical stress, but extensive construction practice has shown that the deformation of the steel casings is determined by circumferential critical stress. According to the “Guidelines for Stability Design of Steel Structures”40, the circumferential critical stress value of steel casings is calculated using the following equation:

where \(\:d\) is the diameter, m; \(\:{f}_{y}\) is the yield strength of the material, MPa;.

Construction of finite element model

The geometric model of the soil around the casing is set as a cylinder, with a diameter and height of 20 m. A large-sized model is used to simulate a semi-infinite space body, ignoring the influence of boundary effects. A 2.0 m high void layer is established on the upper layer of the soil, without setting strength and mass, to facilitate the flow of soil material into the area after the sinking of the casing begins. The surrounding and distant soils of the steel casing are divided into grids, and the area near the steel casing is densified. In the vertical direction, the area penetrated by the casing is divided into a uniform grid of 0.2 m, and a uniform grid of 0.8 m is divided away from the casing. The soil behavior is described using the Mohr-Coulomb constitutive equation. The initial stress of the entire model is defined as gravity, and a predefined field is used in the LOAD module to balance the soil stress. The static lateral pressure coefficient \(\:{k}_{0}\) in the predefined field is calculated to be 0.817, and its expression is as follows41:

The displacement and rotation of the lateral boundary of the soil in the horizontal direction, as well as the displacement and rotation of the bottom boundary in the horizontal and vertical directions, are constrained. The steel casing adopts shell (S4R) elements, with a grid divided into uniform grids of 0.1 m and a depth of 7.5 m. The dynamic display analysis step is used, and the penetration process time is set to 5 s and the penetration speed is set to 1.5 m/s. The contact between tube soil and rock soil is defined as a penalty contact with a tangential friction coefficient of 0.3. The stone of an ellipsoid (C3D8R) with a long axis of 2 m and a short axis of 1 m is set, and its grid is divided into a uniform grid of 0.1 m. The hourglass stiffness control method is selected as Relax stiffness, and the burial depth is 6 m. To reduce computational costs and improve computational efficiency, this paper only simulates the situation where the steel casing collides with the riprap on one side at 1/2 of the long axis during the sinking process, resulting in buckling of the casing end or rock fragmentation. The numerical model is shown in Fig. 5 (The dimensions in the figure are in meters).

The numerical simulation assumes that: (1) The steel casing, soil, and rock fill are homogeneous and isotropic materials; (2) The steel casing is tightly attached to the soil, and the riprap is tightly attached to the soil; (3) The influence of seepage and water migration in the soil during the calculation process is ignored.

Physical and mechanical parameters

The physical and mechanical parameters of the main rock and soil layers obtained from the engineering site investigation and indoor test data are shown in Table 3.

The physical and mechanical parameters of the steel casing are shown in Table 4.

The physical and mechanical parameters of the riprap are shown in Table 5.

Calculation scheme

To analyze the influence of wall thickness, length and diameter of the steel casings on its mechanical and deformation characteristics, a calculation scheme was developed as shown in Table 6.

Results and discussion

Model validation

To verify the correctness of the model and calculation method, this paper first establishes a numerical model based on the steel casing with the number G0, and contrastively analyzes the deformation shape of the casing end with the deformation shape of the steel casing end pulled out on site. Considering the randomness of the collision point between the steel casing and the stone during the sinking process, numerical models were established for the collision of the casing at 1/4 and 3/4 of the long axis of the stone. To increase the reliability of the verification results, a numerical model was established for the collision of a protective casing with a thickness of 20 mm and a length of 60 cm clamps installed at 1/2 of the long axis of the stone. The calculation results of the collision of the steel casing end at 3/4 of the long axis of the stone are shown in Fig. 6a. The buckling deformation of the steel casing in actual engineering is shown in Fig. 6b. The calculation results of the collision of the casing end at 1/4 of the long axis of the stone are shown in Fig. 6c. The installation of the steel casing with clamps at the end is shown in Fig. 6d and e. The calculation results of the collision of the steel casing with clamps at 1/2 of the long axis of the stone are shown in Fig. 6f.

Comparison between the deformation shape of the steel casing end pulled out on site and the deformation shape of the numerical model. (a) The deformation shape of the steel casing after collision at 3/4 of the long axis of the stone; (b) The deformed shape of the steel casing end pulled out on site; (c) Deformation shape of steel casing after collision at 1/4 of the long axis of the stone; (d) Side view of the casing end with clamps installed; (e) Front view of the casing end with clamps installed; (f) Deformation characteristics of steel casing with installation thickness of 20 mm and length of 60 cm clamp after collision at 1/2 of the long axis of the riprap.

When the steel casing collides at 3/4 of the long axis of the stone, the numerical simulation shows that the collision point at the casing end is recessed 0.17 m (14.2% \(D\)) outward from the center of the circle, which is only 0.02 m different from the actual measured value of 0.15 m (12.5% \(D\)) on site; When the steel casing collides at 1/4 of the long axis of the stone, the numerical simulation results show a depression of 0.13 m (10.8% \(D\)) towards the center of the circle at the collision point, which is only 0.01 m different from the actual measured value of 0.12 m (10.0% \(D\)) on site. The numerical simulation shows that there is also a situation where the casing end is concave towards the center of the circle (as shown in Fig. 6c), which is consistent with the deformation of the casing end on site in Fig. 6b. The numerical simulation shows that the deformation of the steel casing end with clamps (as shown in Fig. 6f) is basically consistent with the deformation characteristics of the casing end on the engineering site (as shown in Fig. 6e). Therefore, the numerical model established is reasonable for simulating the collision between the steel casing and stone in a muddy environment.

Influence of the steel casing length

Three different lengths of the steel casings were set according to the penetration depth to investigate the effect of their lengths on the stress and deformation at the casing ends. The same diameter and wall thickness were maintained, and only the lengths of the steel casings were changed to analyze the effect of the lengths on the internal force and deformation at the casing ends. The steel casings numbered G2, G5 and G8 (with a diameter of 2.0 m and a wall thickness of 22 mm, corresponding to lengths of 11 m, 15 m and 19 m, respectively) were selected for comparative analyses.

Stress and deformation of the steel casings

After calculation, the stress distribution at the casing ends numbered G2, G5 and G8 is shown in Fig. 7.

As shown in Fig. 7, the collision reaction force of the stone on the steel casing is transmitted from the end to the casing body. In different casing lengths, stress concentration mainly occurs in the casing end, especially in the area in direct contact with the stone. This stress concentration is caused by high stress gradients and stress concentration effects due to local contact, which can cause curling deformation at the casing end. As the casing length increases, the maximum stress area also expands from 0.42\(D\) to 0.89\(D\). For the steel casing with lengths of 11 m and 15 m, the collision did not penetrate the stone, but only caused its rotation and displacement. As the length increased, the rotation angle of the stone increased from 49.3° to 55.6°. For a steel casing with a length of 19 m, the collision of the stone not only caused rock fragmentation, but also resulted in the casing end being embedded in the stone, and the rotation angle of the stone reached 66.5 °. This result indicates that increasing the length of the steel casing will increase its own weight and the impact force on the stone during the sinking process, thereby significantly improving its penetration ability.

The distribution curves of the shear stress along the direction of S11 (On the horizontal axis, the positive values are tensile stress, and the negative values are compressive stress) of the steel casing numbered G2, G5 and G8 with respect to α (α is the ratio of the distance from the selected node to the casing top to the casing length) are shown in Fig. 8.

As shown in Fig. 8, when the α value is between 0.8 and 1.0, the shear stress values of different casing lengths show a trend of increasing tensile stress first and then decreasing to compressive stress. Due to the casing (19 m) end being embedded in the riprap, the shear stress exerted by the stone support is significantly lower than that of the non embedded casing.

The deflection distribution characteristic curves of the casing bodies numbered G2, G5 and G8 along the concave direction of the casing ends from the casing tops are shown in Fig. 9.

As shown in Fig. 9, the deflection curve of the 11 m long casing is relatively steep, and the deformation is mainly concentrated at the casing end. The deflection curve shapes of the 15 m and 19 m long casings gradually become smoother when the casing length increases, and the casing deformation is no longer limited to the casing end, but distributed in the section where the casing body enters the soil, indicating that the elastic deformation ability of the casing has been significantly improved. At the same time, the maximum deflection value decreased from 371.63 mm to 313.75 mm and 291.12 mm. The above results indicate that the flexibility of the casing body continues to increase as the casing length increases, and its deformation range also increases accordingly, which can better absorb and disperse the energy caused by collision forces, thereby effectively reducing the deformation degree at the casing end.

Casing end resistance

The variation of the end resistance of the steel casings numbered G2, G5 and G8 over time is shown in Fig. 10.

From Fig. 10, it can be seen that the variation of the casing end resistance of the steel casing with different lengths under the same working conditions is basically consistent with time. When the casing end is not in contact with the stone, the resistance at the casing end gradually increases with the depth of the steel casing entering the soil. The dashed interval in Fig. 9 represents the time period during which the casing collides with the stone and the resistance at the casing end decreases significantly. This phenomenon is likely due to the local buckling of the steel casing after colliding with the stone, resulting in a reduction in the effective contact area with the surrounding soil, which in turn leads to a decrease in the casing end resistance. In addition, the stones undergo rotation and displacement after being impacted, resulting in the formation of a cavity at the casing bottom in a short period of time. This cavity causes the steel casing to lack sufficient silt support when further sinking, leading to a decrease in resistance at the casing end. With the increasing length, the peak resistance at the casing end increases from 3000.30 to 3271.91 kN, increased by 8.30%.

Internal forces of the steel casings

The shear forces and bending moments of the steel casings numbered G2, G5 and G8 are shown in Fig. 11.

According to Fig. 11a, it can be seen that in the free section above the silt, the shear force distribution of the casings with lengths of 11 m and 15 m is relatively uniform, and their values remain basically stable. However, in the buried section below the silt, the shear forces gradually decrease due to the supporting effect of the silt. When the α value is between 0.8 and 1.0 in the casing section, the shear force shows a characteristic of first increasing and then decreasing. The peak shear force of the 11 m long casing in this area reaches 507.64 kN, while that of the 15 m long casing is 371.11 kN. In contrast, the peak shear force of the former is 36.8% higher than that of the latter. The casing with a length of 19 m is significantly less affected by the support effect of the stone due to its crushing and embedding, and the shear force is significantly smaller than that of the casing with a length of 11 m and 15 m, and the shear force variation amplitudes are also more gentle. The maximum shear force of the 19 m long casing is 267.21 kN, which is 47.3% lower than that of the 11 m long casing. According to Fig. 11b, when the collision does not embed the casing into the stone, and it is not supported by the stone, the increase in casing length will raise the bending moment on the casing. The casing lengths increase from 11 m to 15 m, and the maximum bending moments on the casing bodies increase from 678.68 kN∙m to 1453.36 kN∙m, an increase of 114.1%. The casing with a length of 19 m is subjected to significantly less bending moment than the rest of the casing foundations due to the support effect of the stone. This result indicates that the increase in casing length and the support effect of the stone significantly alter the stress condition of the steel casings.

Influence of the casing diameters

Maintaining the same length and wall thickness of the steel casings, the casings numbered G13, G14 and G15 were selected for comparative analysis to study the influence of the casing diameter changes on the casing end deformation and internal forces.

Soil stress and soil core height

The stress nephograms in the X-axis direction (S11) and Z-axis direction (S33) of the soil near the steel casings numbered G13, G14 and G15 at a penetration depth of 7.5 m are shown in Figs. 12 and 13.

From Figs. 12 and 13, it can be seen that stress concentration exists in the soil under various casing diameter conditions, and the stress concentration areas are located near the casing end. As the casing diameter increases, the range of stress concentration areas significantly rises, but the stress values of soil S11 and S33 gradually decrease. This is because the steel casing will exert lateral and vertical pressure on the surrounding soil during the sinking process. Due to the rigidity of the steel casing itself, this pressure will compress the soil near the casing end and wall, resulting in a tightening effect. With the increasing casing diameter, it will cause a larger range of soil deformation and displacement during the sinking process, leading to a greater dispersion of soil pressure and weakening the clamping effect, thereby reducing the S11 and S33 stress values of the soil at the casing end.

EVF (Elastic Viscoelastic Fraction) represents the volume fraction of a component in a specific element, which is a dimensionless value between 0 and 1, indicating the proportion of that component in the total volume of the element. The soil flow EVF visualization nephograms is shown in Fig. 14.

According to Fig. 14, as the diameter of the casing increases from 1.6 m to 2.0 m and 2.4 m, the height of the soil core inside the steel casing increases from 6.25 m to 7.03 m and 7.5 m. This is because the S11 and S33 values of the soil at the end of the steel casing with a smaller diameter are higher. This higher stress may result in a higher degree of compaction of the soil near the casing wall, making it denser and less likely to form a higher soil core.

Stress and deformation of the steel casings

The stress distribution at the ends of the steel casings numbered G13, G14 and G15 is shown in Fig. 15.

From Fig. 15, it can be seen that the steel casings have a crushing and rotating effect on the stone. When the casing diameter increases from 1.6 m to 2.4 m, the crushing effect of the stone becomes more significant, but the rotation angle gradually decreases (from 69.7 ° to 16.1 °). When the casing diameter increases to 2.4 m, the steel casing can not only cross the stone, but also does not produce significant bending deformation at the casing end. As the casing diameter increases, the stress concentration area at the casing end significantly decreases, shrinking from 0.89\(D\) (The casing G13) to 0.13\(D\) (The casing G15), reducing the stress concentration area by about 85%. This change may be related to the cross-sectional moment of inertia of the casing, with larger diameter steel casing having a larger cross-sectional moment of inertia, which is a key factor affecting the material’s bending resistance42. Therefore, it can maintain the integrity of the structure under impact, thereby exerting its ability to resist bending deformation.

The stress distribution curves of the shear stress along the S11 direction of the steel casings numbered G13, G14 and G15 as a function of the casing length are shown in Fig. 16.

From Fig. 16, it can be seen that the stress difference on the casings numbered G13 and G14 is not significant when the casing ends are not fully embedded in the stone. After entering the silt soil 2 m below, the tensile stress on the casings gradually increases, and the tensile stress at a distance of 1 m from the casing ends rapidly decreases before turning into compressive stress. Compared with other control groups, the stress values of the casing numbered G15 significantly decrease, and the magnitude of the change is relatively small. This is because the casing end is completely embedded in the stone, which can provide additional support and reduce the stress on the casing body.

The deflection distribution characteristic curves of the casings numbered G13, G14 and G15 along the concave direction of the casing ends from the tops are shown in Fig. 17.

As shown in Fig. 17, the increase in casing diameter has a significant impact on the deflection of the casings. The deflection curve of a casing with a diameter of 2.4 m is steep and the deformation of the casing is very small, with a maximum deflection value of only 3.07 mm. In contrast, the deflection curves of the casings with diameters of 2.0 m and 1.6 m have significantly slowed down, and the maximum deflection value at the end of the steel casing with a diameter of 2.0 m has decreased compared to that with a diameter of 1.6 m, decreasing from 286.74 mm to 215.23 mm. The above phenomenon indicates that an increase in casing diameter is beneficial for reducing deformation at the casing end.

Casing end resistance

The variation of the end resistance of the casings numbered G13, G14 and G15 over time is shown in Fig. 18.

From Fig. 18, it can be seen that the resistance at the casing ends gradually increases with the depth increase of penetration into the soil during the time period of 0 to 3.9 s when the casing end does not collide with the throwing stone. Due to the increase in casing diameter, the actual contact area between the casing end and the sludge increases, and the resistance experienced by the casing end of a 2.4 m diameter casing is significantly higher than that of 1.6 m and 2.0 m diameter casings. As the casing diameter increases, the peak resistance at the casing end will appear earlier. This may be due to the larger mass and stiffness of the large-diameter steel casing, which causes less deformation when it collides with the stone, allowing it to effectively collide with the stone earlier and cause it to break.

Internal forces of the casings

The shear forces and bending moments of the steel casings numbered G13, G14 and G15 are shown in Fig. 19.

Due to the damage caused by the steel casings numbered G13, G14 and G15 to the stone, the shear force distribution of the casing exhibits certain fluctuations. According to the variation law of the shear forces of the casings numbered G13 and G14, it can be seen that the shear force acting on each section of the casings increases with the increasing diameter, and the position of the maximum shear force acting on the casing decreases with the increasing diameter. The shear forces are mainly concentrated within a range of 2 m from the casing ends. Similar to the distribution of shear forces, the steel casings without embedded stones experience an increase in bending moment on each section of the casings as their diameters increase. The steel casing numbered G15 completely crosses the stone and experiences significantly lower shear and bending moments than the casings numbered G13 and G14. The above results indicate that the increase in casing diameter and the support effect of stones significantly improve the stress condition of the steel casings.

Influence of steel casing wall thicknesses.

According to the actual construction requirements, the steel casings with lengths of 11 m, 15 m and 19 m and a diameter of 2.0 m were selected for research by setting 5 wall thicknesses (22 mm, 27 mm, 31 mm, 34 mm and 36 mm).

Stress and deformation of casing bodies

After conducting construction simulation calculations on the casings with different wall thicknesses, the Mises stress distribution of each casing is shown in Fig. 20.

As shown in Fig. 20a, b and c, the numerical values of Mises stress and the range of the stress concentration phenomenon at the casing ends gradually decrease with the increasing wall thickness. The increase in casing wall thickness also increases its sectional moment of inertia, enhancing its bending strength and significantly improving its ability to penetrate stones.

The deflection curves of steel casings with different wall thicknesses are shown in Fig. 21.

From Fig. 21, it can be seen that the deflection curves of the casings gradually increase in slope with the increasing wall thicknesses, while the maximum deformations at the casing ends also gradually decrease. When the casing wall thicknesses increased from 22 to 36 mm, the maximum horizontal deformations at the end of the 11 m long casing decreased from 372.90 to 2.08 mm, decreased by 99.4%. The maximum horizontal deformation at the end of the casing with a length of 15 m decreased from 313.71 to 0.14 mm, decreased by 99.9%. The maximum horizontal deformation displacement at the end of the casing with a length of 19 m decreased from 291.07 to 2.19 mm, decreased by 99.2%. The above phenomenon also indicates that increasing the casing wall thicknesses can significantly reduce the maximum horizontal deformation at the casing ends when their lengths are different. However, the decrease in the maximum horizontal deformations at the casing ends show a trend of first increasing and then decreasing with the increase of casing lengths.

Selection of casing wall thicknesses

Based on the calculation results under different wall thicknesses, it can be found that as the casing wall thickness increases, the deformation at the collision point between the casing end and the stone is significantly reduced, and the depth of embedding in the stone increases. However, the internal force of the steel casing does not change significantly, and the deformation is within the allowable range of construction. Therefore, it is unreasonable to choose the wall thickness solely based on the deformation of the casing end. The thicker the steel casing wall, the better the stability of the sinking casing, but the engineering cost will also significantly increase. Therefore, reasonable selection of the wall thickness should be made while ensuring safety and stability requirements.

Using Eq. (9), the maximum circumferential stress values at the end of steel casing with different wall thicknesses were calculated, and their variation curves over time were plotted, as shown in Fig. 22.

Time history curves of maximum circumferential stresses on the ends of the sinking casings during construction. (a) Time history curves of maximum circumferential stresses at the ends of the casings with a length of 11 m under different wall thicknesses; (b) Time history curves of maximum circumferential stresses at the ends of the casings with a length of 15 m under different wall thicknesses; (c) Time history curves of maximum circumferential stresses at the ends of the casings with a length of 19 m under different wall thicknesses.

As shown in Fig. 22, the maximum circumferential stresses of the casings gradually decrease with the increasing wall thicknesses. According to Eq. (10), the critical stress value is calculated, and the safety factor is taken as 1.5 to determine the allowable stress. According to the above model, after calculation, for steel casings with lengths of 11 m, 15 m and 19 m and a diameter of 2.0 m, the circumferential stress results and allowable stresses under five different wall thickness conditions are shown in Tables 7, 8 and 9, respectively.

From the above analysis results, it can be concluded that the wall thicknesses of the steel casings with lengths of 11 m and 15 m should not be less than 36 mm to ensure the safety and stability during the sinking process. A steel casing with a length of 19 m should be selected with a thicker wall thickness to avoid end buckling during the construction period. Due to the buckling deformation and stress concentration of the casing, as well as the fact that the maximum stress generally occurs at the casing end, and the stress and deformation levels are relatively low at a distance of more than 1 m from the end, a reinforced steel ring with a height of 1–2 m can be installed at the casing end to ensure that the wall thickness at the end is not less than 36 mm, to ensure that the steel casing meets the strength and stiffness requirements during the sinking process. The specific thicknesses of the casing walls also depend on the specific engineering geological environment. Further research will be conducted on the optimization of the casing sinking process and wall thicknesses under different combinations of casing body and casing end wall thicknesses.

Conclusions

In this paper, the stress and deformation laws of the casings are studied by using the finite element method, and the wall thickness is selected according to the distribution law of the stress and deformation of the casings. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

Under the same wall thickness and casing diameter conditions, an increase in casing length can enhance the penetration ability of the casing for stone. The shear forces and bending moments experienced by the steel casing after being embedded with the stone are significantly lower than those of the non embedded casing, indicating that the support effect of the stone can effectively improve the stress situation of the casings. The casing flexibility gradually increases with the increasing length. The deformation range of the casing with a length of 19 m is significantly larger than that of the casing with a length of 11 m, and the maximum deflection value of the casing end decreases from 291.1 mm to 371.63 mm. The stress on the casing body is mainly concentrated at the collision point between the casing end and the stone, and the stress concentration area gradually increases with the increasing length. As the casing increases from 11 m to 19 m, the stress concentration area at the casing end expands from 0.42\(D\) to 0.89\(D\).

-

(2)

Under the same wall thickness and casing length conditions, an increase in casing diameter can enhance the ability of the steel casing to resist bending deformation, thereby improving its penetration ability for stone. Compared to the 1.6 m diameter steel casing, the deflection curve of the 2.4 m diameter steel casing is significantly steeper, and the maximum deflection at the casing end decreases from 286.74 mm to 3.07 mm. The stress concentration area gradually decreases with the increasing casing diameter, and as the casing body increases from 1.6 m to 2.4 m, the stress concentration area at the casing end decreases from 0.89\(D\) to 0.13\(D\). The concentration range of horizontal stress (S11) and vertical stress (S33) in the soil near the casing end gradually increases with increasing diameters, but their values gradually decrease. The height of the soil core inside the steel casing increases with the increasing casing diameters.

-

(3)

Under the same casing length and diameter conditions, as the wall thickness increases, the Mises stress and stress concentration range at the casing end gradually decrease. The deflection curve of the steel casing gradually becomes steeper with the increasing wall thickness, and the maximum deformation at the casing end also gradually decreases. After calculation and analysis, it was determined that the wall thickness of the steel casing with lengths of 11 m and 15 m should not be less than 36 mm, while the steel casing with a length of 19 m requires a larger wall thickness. This can be achieved by installing reinforcement rings at the casing end to increase its stiffness.

Limitations

This study explores the stress and deformation behaviors of steel casings in the collision with the riprap layer of muddy soil, and draws conclusions that have guiding significance for practical engineering. However, there are still some limitations in this article that need to be addressed.

-

(1)

The size of riprap in the numerical model is single and the number is small, which is different from the mudflat environment in the actual project, which may limit the reflection of the model on the diversity of riprap size and distribution in the actual project.

-

(2)

The driving force of the steel casing sinking tube in this study is forced displacement. In the future, other driving methods (such as vibration sinking tube) can be studied to improve the applicability of the model and expand its engineering application scope.

In response to the above limitations, future studies can further construct complex numerical models that are consistent with actual engineering, optimize model parameters and conduct more in-depth research based on actual engineering needs and characteristics.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Holeyman, A., Peralta, P. & Charue, N. Boulder soil pile dynamic interaction. Front. Offshore Geotechnics III Boca Raton: CRC Press. 563–568 (2015).

Dai, G. L. et al. Method for rock-socketed depth of highway Bridge piles in mountain areas. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 40, 225–229. (in Chinese). https://doi.org/10.11779/CJGE2018S2045 (2018).

Nicolini, E. & Gargarella, P. Numerical study of Flint/Boulder behavior during pile driving: Energy and Geotechnics. Presents the proceedings of the 1st Vietnam Symposium on Advances in Offshore Engineering 183–189 (2018).

Tomczyk, B., Golabczak, M., Kubacka, E. & Bagdasaryan, V. Mathematical modelling of stability problems for thin transversally graded cylindrical shells. Continuum Mech. Thermodyn. 36, 1661–1684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00161-024-01322-3 (2024).

Yoshihiro, K. & Atsushi, S. Flexural buckling load of steel pipe piles with rotational end restraints in liquefied soil. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 190, 109217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2025.109217 (2025).

Ko, J. Y. & Jeong, S. S. Plugging effect of open-ended piles Insandy soil. Can. Geotech. J. 52, 664–667. https://doi.org/10.1139/cgj-2014-0041 (2015).

Brown, N., Kowalsky, M. & Nau, J. Impact of D/t on seismic behavior of reinforced concrete filled steel tubes. J. Constr. Steel Res. 107, 111–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcsr.2015.01.013 (2015).

Nietiedt, J. A., Mark, F., Randolph, C. G. & James, P. Preliminary assessment of potential pile tip damage and extrusion buckling. Ocean Eng. 275, 114071. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2023.114071 (2023).

Han, R., Qiao, X. & Li, M. Field tests on vertical bearing characteristics of large-diameterextra-long steel pipe piles in offshore wind power projects. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 46, 180–185. (in Chinese). https://doi.org/10.11779/CJGE2024S10026 (2024).

Lu, J., Li, Y. & Yao, A. Bearing characteristics and ground deformation computationof recyclable Steel-Pipe piles during pit excavation. Appl. Sci. 14, 5727. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14135727 (2024).

Bakroon, M., Daryaei, R., Aubram, D. & Rackwitz, F. Numerical evaluation of buckling insteel pipe piles during vibratory installation. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 122, 327–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2018.08.003 (2019).

Wang, T., Zhang, Y., Bao, X. X. & Wu, X. N. Mechanisms of soil plug formation of open-ended jacked pipe pile in clay. Comput. Geotech. 118, 103334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2019.103334 (2020).

Tang, X. J. Study on the mechanical mechanism of pile sinking in steel trestle ultra-long pile foundation. Transp. Sci. Technol. Western China. 3, 97–99. (in Chinese) https://doi.org/10.13282/j.cnki.wccst.2023.03.027 (2023).

Liu, R., Yi, R. L., Liang, C. & Chen, G. S. Study on the inner friction resistance of super-large diameter steel pipe in clay. Rock and Soil Mechanics 44, 232–240. (in Chinese) https://doi.org/10.16285/j.rsm.2022.0275 (2023).

Shu, J. et al. Influence of the internal friction resistance on the vertical compressive bearing capacity of Large-Diameter steel pipe piles. Buildings 14 (3481). https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14113481 (2024).

Zhang, Q. H. et al. Dynamic buckling behaviour of aluminum alloy thin cylindrical shell under axial impact load: Experimental study. Thin-Walled Struct. 209, 112889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tws.2024.112889 (2025).

Wei, L. M., Li, S. L. & Du, M. Numerical analysis of soil squeezing effect of hydrostatictube based on CEL method. J. South. China Univ. Technol. 49, 28–38. (in Chinese) https://doi.org/10.12141/j.issn.1000-565X.200411 (2021).

Sumin, S., Ruslan, K. & Sangseom, J. Interface friction behavior between soil and steel considering offshore pile driving process by ring shear tests. Transp. Geotechnics. 50, 101481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trgeo.2024.101481 (2025).

Stein, P. Stress effects due to different installation methods for pipe piles in sand. Proc. Institution Civil Engineers:Geotechnical Eng. 177, 533–545. https://doi.org/10.1680/jgeen.23.00105 (2024).

Osthoff, D. & Grabe, J. Deformational behaviour of steel sheet piles during jacking. Comput. Geotech. 101, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2018.04.014 (2018).

Liu, Z. T. & Zhang, Y. H. Effect of drainage conditions on monopile soil-pile interaction in sandy seabed. Ocean Eng. 315, 119826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2024.119826 (2025).

Fabrizio, G., Domenico, A., Paolo, L. & Arturo, P. Simulation of dynamic fracture inquasi-brittle material using a finite element modeling approach enhanced by moving mesh technique and interaction integral method. Procedia Struct. Integr. 41, 576–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prostr.2022.05.066 (2022).

Cheng, J. & Zhang, F. A two-dimensional multi material ALE method for compressible flows using coupled volume of fluid and level set interface reconstruction. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids. 95, 1870–1887. https://doi.org/10.1002/fld.5230 (2023).

Seyedabadi, E., Khojastehpour, M. & Abbaspour-Fard, M. Convective drying simulation of banana slabs considering non-isotropic shrinkage using FEM with the arbitrary Lagrangian-Eulerian method. Int. J. Food Prop. 20, 36–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/10942912.2017.1288134 (2017).

Shoeb, M., Evan, M., Anas, M. & Kamal, M. A. Blast loading resistance of metro tunnel in shale Rock: A Coupled-Eulerian-Lagrangian (CEL) approach. Am. J. Civil Eng. Archit. 10, 106–115. https://doi.org/10.12691/ajcea-10-3-1 (2022).

Dohyun, K. Large deformation finite element analyses in TBM tunnel excavation: CEL and auto-remeshing approach. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 116, 104081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2021.104081 (2021).

Sherburn, A., Hammons, M. & Roth, M. Modeling finite thickness slab perforation usinga coupled Eulerian-Lagrangian approach. Int. J. Solids Struct. 51, 4406–4413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2014.09.007 (2014).

Toll, D. Soil-atmosphere interactions for analysing slopes in tropical soils in Singapore. Enviro Nmental Geotechnics. 6, 361–372. https://doi.org/10.1680/jenge.15.00071 (2018).

Li, D., Wang, L., Cao, Z. & Qi, X. Reliability analysis of unsaturated slope stabilityconsidering SWCC model selection and parameter uncertainties. Eng. Geol. 78, 5727–5743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2019.105207 (2019).

Loulou, C., Andrea, R., Cassandra, R. & Chris, R. Slope stability of streambanks at saturated riparian buffer sites. J. Environ. Qual. 50, 1430–1439. https://doi.org/10.1002/jeq2.20281 (2021).

Qin, Z. P., Lai, Y. M. & Tian, Y. Study on failure mechanism of a plain irrigation reservoir soil bank slope under wind wave erosion. Nat. Hazards. 109, 567–592. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-021-04849-9 (2021).

Qin, Z. P., Lai, Y. M. & Tian, Y. Stability behavior of a reservoir soil bank slope under freeze-thaw cycles in cold regions. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 181, 103181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2020.103181 (2020).

Li, Y., Cheng, L., Wang, M. N. & Xu, T. Y. Three-dimensional upper bound limit analysisof adeep soil-tunnel subjected to pore pressure based on the nonlinear Mohr-Coulomb criterion. Comput. Geotech. 41, 1023–1030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2019.04.025 (2019).

Li, S. Q., Xia, J. H. & Zhang, P. Y. Modified Mohr-Coulom criterion for initial stress linesand undisturbed soils. Eng. Mech. 33, 116–122. (in Chinese) https://doi.org/10.6052/j.issn.1000-4750.2014.06.0521 (2016).

Robert, D. J. A modified Mohr-Coulomb model to simulate the behavior of pipelines in unsaturated soils. Comput. Geotech. 91, 146–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2017.07.004 (2017).

Tang, J. B., Chen, X., Cui, L. S. & Liu, Z. Q. Strain localization of Mohr-Coulomb soils withnon-associated plasticity based on micropolar continuum theory. J. Rock. Mechanicsand Geotech. Eng. 15, 3316–3327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2023.02.029 (2023).

Silva, R., Costa, C. & Arede, A. Numerical methodologies for the analysis of stone Archbridges with damage under railway loading. Structures 39, 573–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2022.03.063 (2022).

Liu, B., Liu, Z. G. & Yang, L. S. Accelerating fracture simulation with phase field methods based on Drucker-Prager criterion. Front. Phys. 11, 1159566. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2023.1159566 (2023).

Ashmarin, Y. Theory of elastic stability of a cylindrical shell weakened by a circular hole. Soviet Appl. Mech. 8, 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00885908 (1972).

Chen, S. F. Formula of referencing in Steel Structure Stability Design Guide (ed. Chen, J.) 124–212 (in Chinese) (China Architecture and Building Press, 2013).

Mesri, G. & Hayat, T. M. The coefficient of Earth pressure at rest. Can. Geotech. J. 30, 647–666. https://doi.org/10.1139/t93-056 (1993).

Ashuri, T. & Zhang, J. Cross sectional modeling of geometrical complex and inhomogeneous slender structures. SoftwareX 6, 155–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SOFTX.2017.04.003 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by Longgang City Water Resources Management Department, Shaoxing Keqiao District Water Resources Management Department, and related engineering participating enterprises. The authors thank the funding and supporting agencies for providing the necessary guidance, financial support and basic data.

Funding

This research was supported by the Nanxun Scholars Program of ZJWEU (RC2024011063) and the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LTGG24E090002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology was contributed by Zipeng Qin, Weishun Zhao and Liangbin Zhang; Formal analysis, investigation and data collection were contributed by Jia Lin, Guoxun Chen, Lefeng Chen, Zhongzhu Lin, Ping Shen, Jingquan Gao, Shixing Liu, Ne Yang, Zhilong Jin, Guangyin Wei and Yan Tian; Writing—original draft preparation, was contributed by Zipeng Qin and Weishun Zhao; Writing —review and editing, was contributed by all the authors; Funding acquisition was contributed by Weishun Zhao, Zipeng Qin, Liangbin Zhang, Zhongzhu Lin, Jia Lin, Ping Shen and Jingquan Gao; Resources were contributed by Guoxun Chen, Lefeng Chen, Shixing Liu, Ne Yang, Zhilong Jin and Guangyin Wei; Supervision was contributed by Liangbin Zhang, Zhongzhu Lin, Ping Shen, Jingquan Gao and Yan Tian.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, W., Qin, Z., Zhang, L. et al. Numerical investigation on the penetration process of steel casings in riprap environment of estuarine mudflats. Sci Rep 15, 7921 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92668-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92668-4