Abstract

To address the issue of spatiotemporal illusion in short-term traffic flow prediction and deeply explore the underlying short-term traffic flow network characteristics, a traffic flow prediction model that combines long-term spatiotemporal heterogeneity with short-term spatiotemporal features is proposed. In the long-term spatiotemporal branch, the Transformer structure is employed, and a self-supervised masking mechanism is utilized to pretrain the heterogeneity in long-term temporal and spatial dimensions separately. Additionally, a spatiotemporal adaptive module is designed, which adapts to and guides short-term traffic flow prediction across time series and traffic flow networks. In the short-term spatiotemporal branch, a recurrent neural ordinary differential equation (ODE) module is devised. This module is capable of continuously and dynamically adjusting short-term spatiotemporal features, better capturing and exploring potential short-term spatiotemporal characteristics. Through multiple cycles, this module gradually and accurately extracts and compresses road network features, integrates the adapted spatiotemporal heterogeneity, and reconstructs future short-term traffic flows in the decoder. Experiments are conducted on four traffic flow and two traffic speed datasets, showing that compared to traditional time series models, the proposed model’s prediction accuracy indicators have relatively improved by 45.09%, 39.14%, and 0.47% on average; compared to recurrent neural network (RNN) series models, the improvements are 18.91%, 15.77%, and 0.18% on average; compared to graph convolution series models, the improvements are 21.31%, 16.65%, and 0.21% on average; and compared to Transformer series models, the improvements are 6.57%, 6.23%, and 0.05% on average. The model’s general applicability and good performance in transportation speed scenarios were verified through a multi-step experiment conducted on the transportation speed dataset.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the process of urbanization accelerates continuously and the demand for transportation increases rapidly, urban road traffic has witnessed social problems such as traffic congestion, environmental pollution, and energy waste, which urgently need to be addressed. The Intelligent Transportation System (ITS) is an effective means to alleviate traffic congestion1, and traffic flow prediction is a crucial technology for realizing intelligent transportation.

In the early stages, traffic flow prediction was primarily based on methods such as dynamic modeling, like the Auto-Regressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA)2, and machine learning methods, such as Support Vector Regression (SVR)3. Recently, residual networks have resolved issues like gradient explosion and vanishing in traditional neural networks. Convolution Neural Networks (CNNs) can better extract the inter-node correlations in the spatial dimension of traffic flow networks, as seen in models like STResNet4 and RSTS5. The key to traffic flow prediction lies in capturing time-series features. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN) are capable of extracting temporally progressive features in traffic flow networks, with examples including LSTM6, DMVSTNet7, DCRNN8, DSAN9, and AGCRN10 for predicting traffic flows across road networks.

With the introduction of Graph Convolutional Neural Networks (GNNs), it was found that mining spatial information yielded better results for traffic flow prediction. Methods based on GCNs were widely applied in traffic prediction, such as STGCN11, GWNet12, and STGNCDE13. As the Transformer14 emerged, the self-attention mechanism enabled the establishment of relationships between each element in a sequence and other elements, helping the model understand contextual information within the sequence and better construct spatiotemporal dependencies along the spatiotemporal axis in traffic scenarios, as seen in models like PDFormer15 and STAEformer16. Recently, the inherent issue of spatiotemporal hallucination in short-term spatiotemporal traffic flow prediction was raised. STDMAE17 addressed this by employing self-supervision to construct and eliminate spatiotemporal heterogeneity, but it lacked refinement of traffic flow features specifically in the temporal and spatial dimensions.

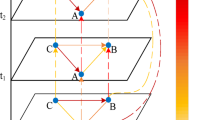

Spatiotemporal hallucination refers to situations where similar short-term historical traffic flows exhibit significant fluctuations in the future, or where dissimilar short-term historical traffic flows show similar trends in the future. The essence of spatiotemporal hallucination arises from the excessively short input and output time series of short-term traffic flows, while traffic flow data is typically collected over several months, with daily time steps potentially containing spatiotemporal heterogeneity. Spatiotemporal heterogeneity encompasses both temporal and spatial heterogeneity, manifesting as differences in traffic volume between weekdays and weekends in the temporal dimension, and as disparities in traffic between urban centers and suburbs in the spatial dimension. Currently, spatiotemporal hallucination represents a novel research area in traffic flow prediction. The challenge lies in accurately and comprehensively extracting spatiotemporal heterogeneity from long spatiotemporal sequences, utilizing these long-term sequence features to guide short-term traffic flow prediction with greater precision, capturing the spatiotemporal dynamic characteristics of short-term sequences more meticulously, and integrating these aspects to improve the accuracy of short-term traffic flow prediction.

In this context, the present study constructed a traffic flow prediction model named ODEFormer, which is based on Ordinary Differential Equations (ODE) and a Spatiotemporal Adaptive Transformer network. The model’s prediction performance, system robustness, and generalization capability were tested on six datasets. The main contributions of the ODEFormer model are as follows:

-

(1)

A traffic flow prediction model employing a self-supervised auxiliary training approach for long-term spatiotemporal encoding and a fully supervised training method for the entire network was introduced to address traffic phenomena characterized by complex scenarios, severe nonlinearity, and spatiotemporal hallucination. This design overcomes the limitations of traditional models, which can only capture short-term sequential spatiotemporal features of hourly traffic flow, at most distinguishing between peak and off-peak periods on a daily basis, but lack the ability to capture long-term sequential features including traffic characteristics of weekends and weekdays. It achieves this by implementing a long-term spatiotemporal encoder to capture spatiotemporal heterogeneity. Through auxiliary task training using spatial and temporal masks during the self-supervised phase, pretrained weights for the traffic flow network that account for spatiotemporal heterogeneity are obtained. These weights are then loaded into the pretrained long-term spatiotemporal branch during the fully supervised phase, and the method is further trained specifically for spatiotemporal prediction tasks.

-

(2)

A long-term spatiotemporal adaptation module was designed to better map long-term spatiotemporal heterogeneity in traffic scenarios to short-term spatiotemporal features, assisting in short-term traffic flow prediction and enhancing prediction accuracy. This design compensated for the limitation of the state-of-the-art model STDMAE. Although STDMAE proposed self-supervision to construct spatiotemporal heterogeneity for eliminating spatiotemporal artifacts, it lacked refinement of traffic flow features in both temporal and spatial dimensions. Long-term spatiotemporal heterogeneity was adapted in temporal and spatial dimensions by using temporal and spatial adaptation modules, respectively. These modules guided the differences in time series information and the changes in traffic network characteristics. This approach achieved the goal of better integrating spatiotemporal heterogeneity with short-term spatiotemporal features to reconstruct the future short-term traffic flow network.

-

(3)

A short spatiotemporal recurrent ODE module was designed to effectively extract short-term spatiotemporal features. Compared with traditional models, the derivative nature of the recurrent neural ordinary differential equation (ODE) module allows for the construction of deeper networks. Through iterative and bidirectional propagation, it dynamically captures and mines significant features of short-term traffic flow. Relying on initial values, it enhances feature memory. Multiple cycles allow for repeated extraction of invisible short-term spatiotemporal characteristics and adaptive dynamic mining of hidden information in the road network, fitting the spatiotemporal characteristics of short-term traffic flow. This module extracts unique short-term historical spatiotemporal features that aggregate road network characteristics, obtaining more precise short-term spatiotemporal features than traditional models. This is used in conjunction with long-term spatiotemporal heterogeneity for short-term traffic flow prediction, improving prediction performance.

Related work

Traffic flow prediction

In the past, during short-term traffic flow prediction, each time step presented a spatial flow map of the traffic network, denoted as \({\varvec{G}}=({\varvec{V}},{\varvec{E}},{\varvec{A}})\). Here, \({\varvec{G}}\) represents the graph, where \({\varvec{V}}\) signifies road nodes, \({\varvec{V}}|=N\) indicates the number of sensor nodes, and \({\varvec{E}}\) is the set storing connections between road network nodes. \({\varvec{A}} \in {{\mathbf{R}}^{N \times N}}\) denotes the connectivity of two traffic sensors which is measured by the distance or similarity of two traffic sensors, which are stored using an adjacency matrix. For any two nodes \({v_i},{v_j} \in {\varvec{V}}\) and \(({v_i},{v_j}) \in {\varvec{E}}\), if they were connected, the corresponding element \({a_{ij}}\) in the adjacency matrix value is 1; otherwise, it is 0.

At each time step t, each sensor at the intersection simultaneously collects the traffic flow data of passing vehicles, constructing a feature matrix \({\varvec{X}}{_{(t)}}={({\varvec{X}}_{t}^{1},{\varvec{X}}_{t}^{2}, \cdots ,{\varvec{X}}_{t}^{N})^T} \in {{\mathbf{R}}^{N \times C}}\). Where \({{\varvec{X}}_{(t)}}\) represents the traffic flow at all nodes in the traffic flow network at time t, Cdenotes the types of information collected by the sensor nodes, here referring to traffic flow data, and T represents the historical sequence of continuous time steps. Based on the data collected from the traffic network spatial graph Gand the historical sequence of T continuous time steps, predict the state of the traffic network for the future \(\hat {T}\) continuous time steps as follows.

Self-supervised masking transformer

In the field of traffic flow, sequences with daily time steps exhibited spatiotemporal heterogeneity. In the past, by randomly masking time segments in the temporal dimension or sensors in the spatial dimension, spatiotemporal representations could be learned, facilitating the performance of downstream tasks. The formulas for temporal and spatial masking in the self-supervised stage are as follows.

where\({\varvec{X}} \in {{\varvec{R}}^{L \times N \times C}}\) represents the long-term spatiotemporal matrix, L denotes the long-term sequence, N signifies the sensor nodes, C stands for traffic flow, and r is the random masking rate with a value of 0.25. For the temporal masking, by randomly masking \(T \times r\) time steps, the output in the temporal dimension is \({\hat {{\varvec{X}}}^{(T)}} \in {{\varvec{R}}^{L(1 - r) \times N \times C}}\). For the spatial masking, by randomly masking \(N \times r\)sensors, the long-term output in the spatial dimension is \({\hat {{\varvec{X}}}^{(S)}} \in {{\varvec{R}}^{L \times N(1 - r) \times C}}\).

The Transformer employs self-attention and multi-head self-attention, along with block embedding techniques and positional encoding. Block embedding techniques can mitigate issues such as excessive memory usage and high computational complexity associated with individual traffic flow networks. Positional encoding provides the input sequence with positional information; in this paper, we adopt sinusoidal positional encoding, which can effectively handle sequences of arbitrary lengths.

Ordinary differential equation (ODE)

The neural ordinary differential equations (ODEs)18 were utilized to assist neural networks in establishing continuous dynamical systems, where the neural networks parameterized the derivatives of hidden states rather than specifying a discrete sequence of hidden layers. Presently, CGNN19 has, for the first time, extended this approach to graph-structured data by defining the derivatives as a combination of the initial and current nodes, achieving a continuous message-passing layer with a smoothly transitioning restart distribution. The neural ODE is formulated as follows.

where \(f\left( {{\text{x}}(\tau ),\tau } \right)\)represents the parameterization of the neural network to model the hidden dynamics. The backpropagation through the ODE layer does not require any internal operations and is constructed as a module of the neural network. Consequently, Fang20 et al. propose a tensor-based ordinary differential equation (ODE) to capture spatiotemporal dynamics, thereby constructing deeper networks and simultaneously utilizing spatiotemporal features. The tensor-based ODE is formulated as follows.

where t is a non-integer, \({ \times _{i(i=1,2,3)}}\) represents matrix multiplication at the i-th index, \(H_0\) is the initial value, \(\hat {{\varvec{A}}}\) is the normalized adjacency matrix, \({\varvec{W}}\) is a learnable feature transformation matrix, \({\varvec{U}}\) is the time transformation matrix, I represents \({\text{ln}}{\varvec{A}}\) undergoing Taylor series expansion to obtain the \(\hat {{\varvec{A}}}-I\)sub-term, and \(\frac{{dH(t)}}{{dt}}\) is the tensor-based ODE.

Construction of a traffic flow prediction model based on neural ordinary differential equations and Spatiotemporal adaptive networks

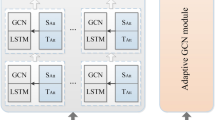

The overall architecture of the network based on neural Ordinary Differential Equations and spatiotemporal adaptive transformer, as depicted in Fig. 1, employed a self-supervised masking mechanism during training to capture spatiotemporal heterogeneity in the long-term spatiotemporal branch. The spatiotemporal adaptive module adapted to matching differences in short-term time series information and changes in transportation network characteristics along both temporal and spatial dimensions, effectively guiding short-term predictions. Meanwhile, in the short-term spatiotemporal branch, spatiotemporal features were fitted, and hidden short-term traffic flow spatiotemporal features were dynamically mined through ODE. After multiple cycles, unique short-term spatiotemporal representations were gradually extracted in a dense and precise manner. Combined with the adapted long-term spatiotemporal heterogeneity, the future short-term spatiotemporal context was reconstructed.

Long-term spatiotemporal branch

The long-term spatiotemporal branch was trained using a self-supervised masking framework to obtain spatiotemporal heterogeneity, preparing it for downstream adaptation to spatiotemporal heterogeneity and guiding short-term spatiotemporal prediction. The TransFormer structure, which is adopted in the long-term spatiotemporal branch, is capable of establishing global dependencies and effectively mining spatiotemporal heterogeneity from daily spatiotemporal sequences. Currently, the reconstruction of spatiotemporal heterogeneity in the long-term temporal and spatial branches is achieved through patch embedding, position encoding, and TransFormer encoding21. The TransFormer encoding consists of six TransFormer encoder layers, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The key components of the TransFormer encoder layer are the multi-head self-attention and feedforward network structure. This structure utilizes self-attention to locally capture spatiotemporal features and concatenates global spatiotemporal features through multi-head self-attention. The feedforward network performs a 4-fold linear transformation to enhance feature capture. The long-term spatiotemporal input \({\varvec{X}}{\text{long}} \in {{\varvec{R}}^{B \times L \times N \times C}}\) was processed to reconstruct the long-term temporal heterogeneity \({{\varvec{Q}}_T} \in {{\varvec{R}}^{B \times N \times T{\text{patch}} \times D{\text{em}}}}\) and the long-term spatial heterogeneity \({{\varvec{Q}}_S} \in {{\varvec{R}}^{B \times N \times T{\text{patch}} \times D{\text{em}}}}\). In this process, within \(T{\text{patch }}=T{\text{long}}/P{\text{size}}\), \(T{\text{long}}\) represented multiple linear transformations in the L-dimensional space, while \(P{\text{size}}\) denoted the block window size with a value of 12, and the embedding dimension \(D{\text{em}}\) was set to 96.

Long-term Spatiotemporal adaptation module

Spatiotemporal heterogeneity was obtained through self-supervised training to capture the latent temporal and spatial heterogeneities of traffic flow networks. This heterogeneity, when fine-tuned in the fully supervised stage, could initially adapt to short-term spatiotemporal networks. However, the direct integration of long-term spatiotemporal heterogeneity with short-term spatiotemporal features does not fully leverage the characteristics of both. Therefore, the Long-term spatiotemporal adaptation module is used to gradually adapt long-term spatiotemporal heterogeneity to short-term features in both temporal and spatial dimensions, guiding the short-term features and achieving higher accuracy. This module is illustrated in Fig. 3.

The long-term spatiotemporal heterogeneous input \({\varvec{X}}{_{\text{Ist}}}\) is expressed as follows.

where \([{Q_S},{Q_T}] \in {{\varvec{R}}^{B \times N \times T{\text{patch}} \times 2D{\text{em}}}}\) represents the concatenation of spatial and temporal reconstruction, while \({\text{CS}}\) represents truncation and cropping.

Long-term spatial heterogeneity adaptation dynamically resizes the input tensor to a specified output size, calculates the maximum and average values, enhances its spatial characteristics through linear mapping, further performs residual connection, activation function, and \(2{\text{D}}\) convolution to transform the output channels, using spatial heterogeneity adaptation to guide short-term spatiotemporal processes. \({\varvec{X}}{_{\text{sa}}}\) represents long-term spatial heterogeneity adaptation. They can be expressed as follows.

where \({\varvec{X}}{_{\text{Ist}0}}\) represents spatial reconstruction, \({\text{Ampool}}\) represents adaptive max pooling, \({\text{Aapool}}\) represents adaptive average pooling, \({\text{C}}{_{\text{2d}}}\) represents \(2{\text{D}}\) convolution with kernel size of 1 and stride of 1, where the first output channel is \({{\text{C}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {C {16}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {16}}\) and the second output channel is C. \(\sigma {_{\text{R }}}\) represents the Relu activation function, + represents matrix addition, and \(\sigma {_{\text{s}}}\) represents the Sigmoid activation function.

Long-term temporal heterogeneity was studied to better adapt to short-term spatiotemporal processes. Maximum and average feature calculations were performed in the temporal dimension, temporal correlations were built through convolution, temporal heterogeneity was adjusted in the residual structure, and output channels were transformed through activation functions and convolution to adapt in the temporal dimension, and \({\varvec{X}}{_{\text{ta}}}\) represents long-term temporal heterogeneity adaptation. They can be expressed as follows.

where \({\varvec{X}}{_{\text{Ist1}}}\)represents temporal reconstruction, \({\text{AL}}\)represents averaging over the L dimension, \({\text{ML}}\)represents taking the maximum over the L dimension, \(\oplus\)represents channel concatenation, and \({\text{C}}{_{\text{2d}}}\) represents \(2{\text{D}}\)convolution, where the former has an input channel of 2 and an output channel of 1, while the latter has an input channel of 96 and an output channel of 256.

Recurrent neural ordinary differential equation (ODE) module

The recurrent neural Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) passively captured the spatiotemporal features in each cycle. Through multiple cycles, the short-term spatiotemporal traffic flow network was gradually compressed onto a single road network. This road network, as illustrated in Fig. 4, represents the unique characteristics of the current short-term historical spatiotemporal context.

The processing of short-term spatiotemporal features in short-time cycles is denoted as process \({\varvec{X}}{_{\text{ci}}}\) as follows.

where \({\varvec{X}}{_{\text{sh}}} \in {{\varvec{R}}^{B \times L \times N \times C}}\)is the input, \({({\varvec{X}}{_{\text{sh}}})^{\text{T}}}\) is the transpose of the input, and \({\text{C}}{_{\text{2d}}}\) represents a \(2{\text{D}}\) convolution where the output channels are 32 and the kernel size is 1. For \({\varvec{X}}{_{\text{ci}}} \in {{\varvec{R}}^{B \times L \times N \times C}}\), the variable L is 13 and the variable C is 32.

The initial short-term spatiotemporal fitting process gradually reduces the number of channels in the traffic flow dimensions through parity convolution. Nonlinear transformations are then applied using sigmoid and tanh activation functions, followed by matrix multiplication to complete the fitting. The initial short-term spatiotemporal fitting process is represented by \({\varvec{X}}{_{\text{o1}}}\) as follows.

Here \({\text{PC}}{_{\text{2d}}}\) represents an odd-even convolution with a kernel size of \(1 \times 2\), a stride of 1, and both input and output channels being 32. During odd cycles, it converts to a regular \(2{\text{D}}\) convolution, while during even cycles, it converts to a dilated \(2{\text{D}}\) convolution with a dilation rate of 2. \(\sigma{_{\text{T}}}\) denotes the Tanh activation function, and * represents the dot product operation.

The jump output for the eighth iteration of the loop is represented by \({\varvec{X}}{_{\text{skip}}}\) as follows.

where \({\text{C}}{_{\text{2d}}}\) has an input channel of 32 and an output channel of 256 with a convolution kernel size of 1. \({\varvec{X}}{_{\text{lskip}}}\) represents the saved jump output from the previous round, initially set to 0.

Then, the input of an adjacency matrix and a trainable parameter matrix is represented by \({\varvec{X}}{_{\text{o2}}}\) as follows.

where \({\varvec{N}}{_{\text{OD1 }}}\)represents the trainable parameters of \(307 \times 10\), \({\varvec{N}}{_{\text{OD2 }}}\)represents the trainable parameters of \(10 \times 307\), \({\varvec{A}}{_{\text{gjs}}}\) represents the adjacency matrix, and \(\oplus\) represents the weighted sum in the first dimension.

The process of ODE continuously and dynamically mining potential short-term spatiotemporal information is represented by \({\varvec{X}}{_{\text{ode}}}\) as follows.

The representation of \({\varvec{X}}{_{\text{lo}}}\) for generalization and adaptation is as follows.

where ODE stands for neural Ordinary Differential Equations, and BN stands for batch normalization.

Neural ordinary differential equation (ODE) module

ODE dynamic equation \(f{_{\text{ODE}}}\), gradually uncovers the hidden information of the road network and fits the spatiotemporal characteristics of short-term sequences, as shown in Fig. 5.

Create dynamic weights \({\varvec{W}}{_{\text{alpha}}}\) for all sensor nodes as follows.

where \({{\varvec{W}}^{{\text{(al)}}}}\) represents the number of trainable parameters for the sensor nodes, \(\sigma{_{\text{s}}}\) represents the Sigmoid activation function, and \({\text{R}}{_{\text{S}}}\) represents the dimension expansion operation.

Obtain the weights \({\varvec{X}}{_{\text{xa}}}\) for the sensor nodes in the road network as follows.

where \({\varvec{A}}\) is the adjacency matrix of the road network nodes, \({{\varvec{A}}^{\text{T}}}\) is the matrix transpose, \(\times\) is the matrix multiplication, and \({\varvec{X}}{_{\text{in}}}\) is the input to the ODE dynamic function. The traffic flow dimensions are successively looped in decreasing order: 13, 12, 10, 9, 7, 6, 4, 3, and 1.

The short-term traffic flow spatiotemporal network mines hidden information in the traffic flow dimension, represented by \({\varvec{X}}{_{\text{XW}}}\) as follows.

where \({{\varvec{W}}^{{\text{(w)}}}}\)is the \(32 \times 32\) trainable parameter matrix for traffic flow, which more finely extracts hidden information from the traffic flow. Each forward propagation adjusts the short-term traffic flow features, while the backward propagation dynamically updates the traffic flow matrix. \({{\varvec{W}}^{{\text{(d)}}}}\)represents trainable parameters with a value of 32, \(|{{\varvec{W}}^{{\text{(d)}}}}|\)denotes adjusting values to within the range of 0 to 1, and * represents the matrix dot product operation.

The short-term traffic flow spatiotemporal network mines hidden information in the time dimension, represented by \({\varvec{X}}{_{\text{XW2}}}\) as follows.

where \({{\varvec{W}}^{{\text{(w2)}}}}\)is a \(12 \times 12\) trainable parameter matrix for the time series, which more precisely fits the short-term sequence difference information and mitigates the issue of similar short-term historical patterns in spatiotemporal illusions. \({{\varvec{W}}^{{\text{(d2)}}}}\) represents a trainable parameter with a value of 12, and \(|{{\varvec{W}}^{{\text{(d2)}}}}|\) denotes adjusting values to within the range of 0 to 1.

The overall calculation formula is presented as follows.

where – represents the matrix subtraction operation.

Experiment design and result analysis

Benchmark datasets

To evaluate the ODEFormer model, experiments were conducted on six standard and open-source real-world spatiotemporal datasets. The dataset includes four traffic flow datasets (PEMS03, PEMS04, PEMS07, PEMS08) from the California Department of Transportation’s Performance Measurement System (PEMS), as well as two traffic speed datasets (METR-LA and PEMS-BAY).

PEMS03: Contains real-time traffic flow data for highways between major cities in California, including multi-lane traffic conditions.

PEMS04: Collects data from highway networks between other major cities or longer distances within cities, different from the collection areas of the above datasets, reflecting the diversity of traffic backgrounds.

PEMS07: Focuses on traffic flow data in the Los Angeles area of California. It may include data from urban roads, facilitating researchers’ analysis of urban traffic characteristics and trends.

PEMS08: Covers a broader geographical area and road network. This subset may help explore traffic flow prediction more comprehensively and validate algorithm performance on a larger scale.

METR-LA: Data is collected by loop detector systems installed at multiple detection sites on the highway network in Los Angeles County.

PEMS-BAY: The dataset originates from the Performance Measurement System of the California Department of Transportation, providing a comprehensive database of real-time traffic data from individual detectors (such as inductive loop sensors, magnetic sensors, or microwave radar sensors) on California highways, primarily targeting the San Francisco Bay Area.

The original data for the above six datasets were continuously sampled every 5 min by a large number of sensors. The spatial adjacency network for each dataset is constructed based on the actual road network and distances, comprehensively covering real-time traffic data for highways and urban roads, with specific information shown in Table 1. During the data preprocessing stage, Z-score normalization was applied to the input raw data. Z-score standardization was used to unify the dimensions of multivariate time series data by transforming each feature into a standard normal distribution with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. This achieves dimension unification, reduces the excessive interference effect that certain features may have on model training, accelerates model convergence, and enhances model efficiency. The reason why this method can promote faster convergence of the optimization algorithm is that the standardized data follows a uniform distribution, which facilitates more efficient gradient descent. At the same time, by weakening the dependency on each feature in the model, it promotes effective learning of relationships between features, further improving prediction accuracy. The public datasets used in this study have been preprocessed strictly according to standard procedures, and there are no outliers in the data.

Experimental setting

Translating previous work22,23,24,25, the datasets PEMS03, PEMS04, PEMS07, and PEMS08 are trained, validated, and tested in a 6:2:2 ratio according to the benchmark model. On METR-LA and PEMS-BAY, 70% of the data is used for training, 20% for testing, and the remaining 10% for validation. Self-supervised spatiotemporal masking is employed for auxiliary task training, which will capture the underlying data correlation patterns over long-term temporal and spatial scales. Except for PEMS08, which has a long-term time step input of 2016, the long-term time step input for other datasets is 864. The core work of this paper focuses on short-term traffic flow prediction, which involves using traffic data from the past hour to predict the spatiotemporal trends of traffic in the next hour. Therefore, the input and output time steps are set to 12, the long-term spatiotemporal embedding dimension is 96, and the encoder consists of 6 Transformer layers with 4 heads for multi-head attention and a patch size of 12, consistent with the prediction input. The Adam optimizer is used with an initial learning rate of 0.001. The loss function evaluation metric adopted is the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) loss.

All experiments were conducted on a cloud computing platform equipped with an RTX 3090 GPU, a 14 vCPU Intel(R) Xeon(R) Platinum 8362 CPU, 45GB of RAM, and a 50GB data storage disk. The operating system used was Ubuntu 20.04.4. The software environment consisted of Python version 3.9 and PyTorch version 1.13.0.

Metrics

To better assess the performance of the algorithm designed in this paper for short-term traffic flow prediction, three commonly used metrics are employed: Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Rooted Mean Square Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), which can be expressed as:

-

(1)

Mean absolute error (MAE):

-

(2)

Rooted mean square error (RMSE):

-

(3)

Mean absolute percentage error (MAPE):

In Eqs. (23–25): the variable s represents the number of predicted values, \({\hat {y}_s}\) is the s-th predicted value, and \({y_s}\) is its corresponding true value.

At the same time, we define the comparison parameter \(\Delta {E_{\text{i}}}\) between evaluation metrics and the relative improvement indicator \(\Delta {P_{\text{i}}}\) of prediction performance. The formulas are as follows:

In Eqs. (26–28): \({E_i}\) represents the evaluation metric of the ith comparison model, E represents the evaluation metric of ODEFormer, n is the number of comparison models, N is the number of evaluation metrics, and j is the number of standard datasets.

Baseline model

The model presented in this paper belongs to the Transformer series. The comparison models include: ARIMA2 and SVR3 based on traditional time series, LSTM6, DCRNN8, ST-WA26, and EnhanceNet27 based on the RNN series, AGCRN10, STGCN11, GWNet12, TCN28, ASTGCN29, STSGCN23, STGODE20, DSTAGNN30, ASTGNN31, Z-GCNETs32, and STFGNN33 based on graph convolution, as well as STNorm34 based on the Transformer series. The research work was conducted in the past, whereas the research conclusions presented here are current.

Experimental results and analysis

Comparison of prediction accuracy

The ODEFormer model was compared with other advanced models in experimental tests, as shown in Table 2. Compared to traditional time series models, the ODEFormer achieved an average reduction of 14.08, 18.20, and 10.21% in MAE, RMSE, and MAPE, respectively, with a relative average improvement of 45.09%, 39.14%, and 0.47% in performance. See Table 3 for details. Compared to RNN-based models, the ODEFormer achieved an average reduction of 4.22, 5.52, and 2.99% in MAE, RMSE, and MAPE, respectively, with a relative average improvement of 18.91%, 15.77%, and 0.18% in prediction accuracy. See Table 4 for details. This indicates that our model is better at integrating long-term and short-term temporal information. Graph convolution-based models can better capture the adjacency relationships between sensors. Compared to advanced models in this series, the ODEFormer achieved an average reduction of 3.76, 4.62, and 2.27% in MAE, RMSE, and MAPE, respectively, with a relative average improvement of 21.31%, 16.65%, and 0.21% in prediction accuracy. See Table 5 for details. Demonstrating that the ODEFormer model can better capture spatial information between nodes in the spatial dimension. Compared to Transformer-based models, the ODEFormer achieved an average reduction of 3.14, 4.54, and 2.00% in MAE, RMSE, and MAPE, respectively, with a relative average improvement of 6.57%, 6.23%, and 0.05% in prediction accuracy. See Table 6 for details. Indicating that the proposed model outperforms previous networks in constructing long-range spatiotemporal dependencies and highlights the value of combining long-term and short-term spatiotemporal information in traffic flow prediction.

Comparison of different time series prediction methods on traffic flow datasets

The ODEFormer model was tested on the PEMS04 and PEMS08 datasets using different time steps to evaluate its stability across various time horizons. Training and prediction were conducted with time steps of 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12. For comparison, the selected models included SVR, LSTM, DCRNN, STGCN, GWNET, ASTGNN, and STNorm. The results are shown in Figs. 6 and 7. It can be observed that on the two datasets, the ODEFormer model exhibits lower prediction performance evaluation metric values across different time steps compared to the seven advanced models used for comparison. Especially when compared to the STNorm model, which also belongs to the Transformer series, the ODEFormer model demonstrates superior prediction performance, indicating its high prediction accuracy in the same field at present. Meanwhile, the graph of the model’s curve shows that it has the lowest slope, meaning that the model’s evaluation metric results on the same dataset vary little across the six time steps, indicating the model’s good stability.

Comparison of different time series prediction methods on traffic speed datasets

The ODEFormer model proposed in this paper was trained and tested for traffic speed prediction scenarios, with experiments conducted on the METR-LA and PEMS-BAY datasets using different time steps (3, 6, and 12) to evaluate the model’s stability in short-term traffic speed prediction. The results were compared with SVR, DCRNN, STGCN, GWNET, ASTGNN, and STSGCN, as shown in Figs. 8 and 9. It can be observed that on the two datasets, the ODEFormer model outperforms seven advanced models in terms of prediction performance at time steps of 3, 6, and 12, with all three evaluation metrics showing lower values. In particular, its performance is significantly better than that of the STNorm model, which also belongs to the Transformer series. These comparison results not only indicate that the ODEFormer model has good prediction performance but also demonstrate its strong generalization capability, as it exhibits excellent prediction performance on the traffic speed dataset as well.

Ablation study

Ablation experiments are conducted to assess the impact of core components on prediction results.

-

1.

Base: Baseline, removing the short-term spatiotemporal cyclic ODE and long-term spatiotemporal adaptation modules.

-

2.

STDODE: Short-term spatiotemporal cyclic ODE, adding the short-term spatiotemporal cyclic ODE module to the position of the baseline network.

-

3.

LSTRM: Long-term spatiotemporal adaptation module, adding the long-term spatiotemporal adaptation module to the position of the baseline network.

-

4.

ODEFormer: Spatiotemporal adaptation transformer network based on neural ordinary differential equations, adding both the short-term spatiotemporal cyclic ODE module and the long-term spatiotemporal adaptation module to the baseline position.

Ablation experiments were conducted on the PEMS04 and PEMS08 datasets, as shown in Figs. 10 and 11. The baseline (Base) achieved average MAE, RMSE, and MAPE of 25.71, 44.04, and 0.1785% on both datasets. When the Short-Term Dynamic ODE (STDODE) module was added to the Base, the average MAE, RMSE, and MAPE decreased by 8.77, 16.66, and 6.6%, respectively, indicating that STDODE can dynamically adjust short-term historical features in a continuous and cyclic manner, which is beneficial for the decoder to reconstruct short-term future predictions. When the Long-Term Spatiotemporal Adaptation Module (LSTRM) was added to the Base, the average MAE, RMSE, and MAPE decreased by 9.07, 17.27, and 5.6%, respectively, demonstrating the effectiveness of the module in adapting spatiotemporal heterogeneity across both time and space dimensions. Compared to the STDODE module alone, the entire ODEFormer network reduced MAE, RMSE, and MAPE by 0.87, 1.11, and 0.47%, respectively. Compared to the LSTRM module alone, ODEFormer reduced MAE, RMSE, and MAPE by 0.57, 0.92, and 1.45%, respectively. These results fully validate the effectiveness of the ODEFormer model in combining adapted long-term spatiotemporal heterogeneity with cyclic and continuous dynamic adjustment of past features.

Conclusion

Short-term traffic flow prediction is affected by the limitations of short-time series data information, leading to spatiotemporal illusions and requiring the excavation of deep-layered spatiotemporal features. In this paper, we propose a model based on Neural Ordinary Differential Equations and a Spatiotemporal Adaptation Transformer Network, which is validated on four datasets. The main conclusions are as follows.

-

1.

Based on the Transformer structure, a self-supervised masking mechanism is employed to assist in training long-term spatiotemporal encoding by randomly masking time segments of long-term time steps or traffic flow network sensors. Fully supervised training of the entire network adapts and orderly guides the integration of both short- and long-term spatiotemporal depth features for precise short-term traffic flow prediction. The long-term spatiotemporal adaptation module appropriately matches long-term spatiotemporal heterogeneity with corresponding short-term spatiotemporal features. The recurrent Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) module captures short-term spatiotemporal latent characteristics, which are then combined with long-term spatiotemporal heterogeneities for short-term traffic flow prediction, thereby enhancing prediction performance.

-

2.

Comparisons with various advanced models from different series demonstrate that the ODEFormer model proposed in this paper achieves improvements in Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), with enhancement ranges of 45.09–6.57%, 39.14–6.23%, and 0.47–0.05%, respectively. These results indicate that our model offers higher prediction accuracy. Furthermore, the advantages of the ODEFormer model in predicting short-term traffic flow become more evident in more complex traffic scenarios.

-

3.

Experiments were conducted on four traffic flow datasets with distinct characteristics, namely PEMS03, PEMS04, PEMS07, and PEMS08, as well as two traffic speed datasets, METR-LA and PEMS-BAY. The results show that the ODEFormer model exhibits higher prediction accuracy than other models in the series, demonstrating stronger generalization capabilities. Furthermore, the model possesses better robustness and stability in predicting traffic flows across different traffic scenarios and at various time steps.

Data availability

All the programs used in the experiments in this paper have been made open-source on the internet for discussion and exchange among all interested researchers. The open-source website is: https://github.com/marylovemali/ODEFormer.

References

Tedjopurnomo, D. A., Bao, Z. F., Zheng, B. H., Choudhury, F., Qin, M. A. K. A survey on modern deep neural network for traffic prediction: trends, methods and challenges. J. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 34 (4), 1544–1561 (2020).

Kumar, S., Vanajakshi, L. & V. & Short-term traffic flow prediction using seasonal ARIMA model with limited input data. J. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 7, 1–9 (2015).

Castro-Neto, M., Jeong, Y., Jeong, S., Han, L. & M., K. & Online-SVR for short-term traffic flow prediction under typical and atypical traffic conditions. J. Expert Syst. Appl. 36 (3), 6164–6173 (2009).

Zhang, J., Zheng, Y. & Qi, D. Deep spatio-temporal residual networks for citywide crowd flows prediction. C. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell.. 31(1) (2017).

Yao, H., Tang, X., Wei, X. F., Zheng, H. & Li, Z. G., J. H. Revisiting spatial-temporal similarity: A deep learning framework for traffic prediction. C. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell.. 33(01), 5668–5675 (2019).

Shi, X. et al. Convolutional LSTM network: a machine learning approach for precipitation nowcasting. J. Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst. 28, (2015).

Yao, H. et al. Deep multi-view spatial-temporal network for taxi demand prediction. C. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 32(1), (2018).

Li, Y., Yu, G., Shahabi, R. & Liu, Y. C. Diffusion convolutional recurrent neural network: data-driven traffic forecasting. C. https://arxiv.org/1707.01926 (2018).

Lin, H., Bai, X., Jia, R. F., Yang, W. J. & You, Y. X., Yu. J. Preserving dynamic attention for long-term spatial-temporal prediction. C. Proceedings Of The 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference On Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining.36–46 (2020).

Bai, L., Yao, L., Li, N., Wang, C., Wang & X., Z., & Can. Adaptive graph convolutional recurrent network for traffic forecasting. J. Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst. 33, 17804–17815 (2020).

Yu, B., Yin, H. & Zhu, Z. T. X. Spatio-temporal graph convolutional networks: a deep learning framework for traffic forecasting. In C. Proceedings of the 27th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence. 3634–3640 (2018).

Wu, Z., Pan, H., Long, S. R., Jiang, G. D. & Zhang, C. J. Q. Graph WaveNet for deep spatial-temporal graph modeling. In C. International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI), 1907–1913 (2019).

Choi, J., Choi, H., Hwang, J. & Park, N. Graph neural controlled differential equations for traffic forecasting. C. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 36(6), 6367–6374 (2022).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. J. Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst. 30 (2017).

Jiang, J. W., Han, C. K., Zhao, W. & Wang, J. X. Y. Jingyuan Pdformer: Propagation delay-aware dynamic long-range transformer for traffic flow prediction. C. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 37(4), 4365–4373 (2023).

Liu, H. C., et al. Spatio-temporal adaptive embedding makes vanilla transformer sota for traffic forecasting. In C. Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, 4125–4129 (2023).

Gao, H., Jiang, T., Dong, R. H., Deng, Z. & Song J.L.X. Spatio-temporal-decoupled masked pre-training for traffic forecasting. J. License: arXiv Preprint arXiv:2312.00516 (2023).

Chen, R., Rubanova, T., Bettencourt, Y. & Duvenaud, D. J., Neural ordinary differential equations. J. Comput. Sci.. https://arxiv.org/1806.07366 (2018).

Xhonneux, L., Qu, P. & Tang, J. M. Continuous graph neural networks. In C. In International Conference On Machine Learning. 10432–10441 (PMLR, 2020).

Fang, Z., Long, Q., Song, Q. & Xie, K. G., J. Q. Spatial-temporal graph ode networks for traffic flow forecasting. In C. Proceedings Of The 27th ACM SIGKDD Conference On Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining. 364–373 (2021).

Nie, Y., Nguyen, N., Sinthong, H. & Kalagnanam, J. P. A time series is worth 64 words: long-term forecasting with transformers. C. The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations.. https://arxiv.org/2211.14730 (2023).

Wang, Z. & Liu, J. Translating math formula images to latex sequences using deep neural networks with sequence-level training. J. Int. J. Doc. Anal. Recognit. (IJDAR). 24 (1), 63–75 (2021).

Song, C., Lin, Y., Guo, F. & Wan, H. S. N.Y. Spatial-temporal synchronous graph convolutional networks: A new framework for spatial-temporal network data forecasting. C. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 34(01), 914–921 (2020).

Li, M. & Zhu, Z. Z. X. Spatial-temporal fusion graph neural networks for traffic flow forecasting. C. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 35(5), 4189–4196 (2021).

Jiang, J., Han, W., Zhao, C. K., Wang, J. & Pdformer, Y. W., X., Propagation delay-aware dynamic long-range transformer for traffic flow prediction. C. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell.. 37(4), 4365–4373 (2023).

Cirstea, R., Yang, G., Guo, B., Kieu, C. J. & Pan, S. T. Towards spatio-temporal aware traffic time series forecasting. In C. 2022 IEEE 38th International Conference On Data Engineering (ICDE)., 2900–2913 (IEEE, 2022).

Cirstea, R. et al. B., Plugin neural networks for enhancing correlated time series forecasting. In C. 2021 IEEE 37th International Conference On Data Engineering (ICDE), 1739–1750 (IEEE, 2021).

Shaojie, B., Zico Kolter, J. & Vladlen K. An Empirical Evaluation of Generic Convolutional and Recurrent Networks for Sequence Modeling. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/1803.01271 (2018).

Guo, S., Lin, N., Feng, Y. F., Song, N. & Wan, H. C. Attention based spatial-temporal graph convolutional networks for traffic flow forecasting. C. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell.. 33(01), 922–929 (2019).

Lan, S. et al. H., Y. Dynamic spatial-temporal aware graph neural network for traffic flow forecasting. In C. International Conference on Machine Learning. 11906–11917 (PMLR, 2022).

Guo, S., Lin, N., Wan, Y. F., Li, H. Y., Cong, G. X. C. Learning dynamics and heterogeneity of spatial-temporal graph data for traffic forecasting. J. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 34 (11), 5415–5428 (2021).

Chen, Y., Segovia, Z. & Gel, Y. I. R. Z-GCNETs: Time zigzags at graph convolutional networks for time series forecasting. In C. International Conference on Machine Learning. 1684–1694 (PMLR, 2021).

Li, M. & Zhu, Z. Z. X. Spatial-temporal fusion graph neural networks for traffic flow forecasting. C. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell.. 35, 4189–4196 (2021).

Deng, J., Chen, L., Jiang, X. S., Song, R. H. & Tsang, I. W. X. St-norm: Spatial and temporal normalization for multi-variate time series forecasting. In C. Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, 269–278 (2021).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (6136606) and the Innovation Fund Project for University Teachers of Gansu Provincial Education Department of China (2023B-294), the financial assistance provided by these projects enabled us to complete our experiments. Additionally, we express our deep gratitude to the editors and reviewers for their attention and assistance throughout the article. We are truly thankful for their contributions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.M. and Y.W. wrote the main manuscript text, L.M. prepared the references, L.M. and X.L. completed all the programming and debugging, L.M. prepared Figs. 1, 2 and 3 and Y.W. prepared Figs. 4 and 5 and X.L. prepared Tables 1 and 2; Figs. 6 and 7 and L.G. prepared Figs. 8, 9, 10 and 11. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, L., Wang, Y., Lv, X. et al. Construction of a traffic flow prediction model based on neural ordinary differential equations and Spatiotemporal adaptive networks. Sci Rep 15, 9787 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92859-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92859-z