Abstract

Rapid diagnosis of kidney bean leaf spot disease is crucial for ensuring crop health and increasing yield. However, traditional machine learning methods face limitations in feature extraction, while deep learning approaches, despite their advantages, are computationally expensive and do not always yield optimal results. Moreover, reliable datasets for kidney bean leaf spot disease remain scarce. To address these challenges, this study constructs the first-ever kidney bean leaf spot disease (KBLD) dataset, filling a significant gap in the field. Based on this dataset, a novel hybrid deep learning model framework is proposed, which integrates deep learning models (EfficientNet-B7, MobileNetV3, ResNet50, and VGG16) for feature extraction with machine learning algorithms (Logistic Regression, Random Forest, AdaBoost, and Stochastic Gradient Boosting) for classification. By leveraging the Optuna tool for hyperparameter optimization, 16 combined models were evaluated. Experimental results show that the hybrid model combining EfficientNet-B7 and Stochastic Gradient Boosting achieves the highest detection accuracy of 96.26% on the KBLD dataset, with an F1-score of 0.97. The innovations of this study lie in the construction of a high-quality KBLD dataset and the development of a novel framework combining deep learning and machine learning, significantly improving the detection efficiency and accuracy of kidney bean leaf spot disease. This research provides a new approach for intelligent diagnosis and management of crop diseases in precision agriculture, contributing to increased agricultural productivity and ensuring food security.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Kidney bean cultivation has a long history in China. In recent years, China’s kidney bean industry has developed steadily, making the country one of the largest producers of kidney beans globally. Specifically, the planting area in China is approximately 400,000 hectares, with an average annual export volume of about 5000 tons, accounting for roughly 5% of global food exports1,2,3. However, in large-scale kidney bean plantations, if diseases are not detected and controlled promptly, they may significantly impact production4,5. This is especially evident from early spring to early summer, when diseases such as bean mosaic virus can escalate into epidemics, causing substantial losses. The principle of“prevention first, integrated management”is crucial for disease control. Therefore, timely detection and accurate identification of diseases are essential to implement effective prevention and control measures5,6 .

Plant diseases, as a core issue threatening global food security, cause annual crop losses of up to 20–40%7. Traditional manual detection methods are inefficient and highly subjective8. Existing studies predominantly focus on maize9,10 , sugarcane11, and grapes8, leaving a dedicated detection framework for economic crops such as red kidney beans largely undeveloped.

The symptoms of kidney bean leaf spot disease are complex. Traditional disease control techniques primarily rely on manual real-time observation of disease progression, followed by the formulation of control strategies based on identified diseases. However, the accuracy of disease identification can vary due to differences in the expertise of personnel, leading to the improper use of pesticides and other chemicals, which significantly affects the growth and quality of kidney beans. Additionally, identification methods based on biosensors and spectroscopy are hindered by high costs and the need for skilled professionals, making them unsuitable for large-scale applications.

In the agricultural field, machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) have become common approaches for crop disease detection. Many studies have adopted these techniques. For example, Islam et al. combined image segmentation with a support vector machine (SVM) classifier for potato image analysis, achieving an identification rate of over 95%12. Zhang Chunlei et al. extracted 38 features from plant leaves, including color, texture, and shape, forming a feature set13. Using the SVM algorithm for classification, they successfully identified three types of leaf spot diseases in kidney beans: powdery mildew, mosaic virus, and rust, with an identification accuracy exceeding 90%.

In the field of deep learning, CNN models (e.g., ResNet and DenseNet) leverage local feature extraction to achieve over 95% accuracy on the PlantVillage dataset (References 1 and 5), among which DenseNet attains a 99.83% accuracy in corn disease detection10. In comparison, MaxViT9 and MobileViT10 excel in complex backgrounds due to their self-attention mechanisms, achieving 99.24% and 100% accuracy on the corn and CD&S datasets, respectively.

Regarding hybrid strategies, the CNN-ViT fusion framework (MaxViT + DeiT3) proposed in paper10 enhances robustness through soft-voting integration. Meanwhile, Swinv2-Base8 reaches 100% accuracy on grape diseases, confirming the effectiveness of multi-model fusion. In addition, lightweight techniques such as EfficientNetv2-small (93.39% accuracy)11 and MobileViT10 offer valuable insights for mobile deployment in red kidney bean detection.

Similarly, Picon et al. designed a wheat leaf disease detection model using deep learning by combining transfer learning with ResNet50 and a custom dataset of over 8,000 images, achieving an average accuracy of 87%14. Mohanty et al. developed a smartphone-assisted disease diagnosis system by integrating neural network architectures such as AlexNet and GoogleLeNet, effectively identifying 14 different crops and 26 diseases with an accuracy of up to 99.35%15.

Despite significant progress made by researchers at home and abroad in detecting crop diseases using artificial intelligence techniques, challenges remain. These challenges include low accuracy of kidney bean leaf spot disease detection models, large network parameter sizes, and overfitting issues that limit their practical applications.

To overcome these challenges, this study proposes a Hybrid Deep Learning Model (HDLM) framework that integrates the advantages of deep learning and machine learning techniques to improve accuracy and computational efficiency. The primary focus of this study is to detect kidney bean leaf spot diseases using the proposed HDLM framework. The study utilizes the image-based Kidney Bean Leaf Disease (KBLD) dataset collected from the experimental base at Taoyuanbao, Taigu District, Jinzhong City, Shanxi Province.

Deep learning models, including EfficientNet-B7, MobileNetV3, ResNet50, and VGG16, are employed to extract features from the KBLD dataset. Subsequently, four machine learning algorithms-AdaBoost (ADB), Logistic Regression (LR), Random Forest (RF), and Stochastic Gradient Boosting (SGB)-are used to classify the extracted features. The Optuna framework is applied to optimize hyperparameters, enhance model performance, and determine the most effective models and algorithms for detecting kidney bean leaf spot diseases.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows: (1) A comprehensive image dataset containing three types of kidney bean leaf spot diseases was constructed with the assistance of agricultural experts. (2) Several preprocessing and augmentation techniques, including rotation, noise reduction, and segmentation, were applied to the dataset to expand its size and enhance the model’s generalization capability. (3) Multiple hybrid deep learning models (e.g., EfficientNet-B7, MobileNetV3, VGG16, and ResNet50 combined with ADB, RF, LR, and SGB, respectively) were employed to predict kidney bean leaf spot diseases, and their predictive performances were analyzed. The overall performance of the algorithms was significantly improved through hyperparameter optimization using Optuna.

The structure of this paper is organized as follows: Section “Proposed method” introduces essential background knowledge and presents the designed algorithms. Section “Experimental results and analysis” concentrates on the experimental framework and offers a multi-perspective comprehensive analysis of the results. Section “Conclusion” concludes the paper by emphasizing its theoretical contributions and addressing research limitations.

Proposed method

This study constructed the KBLD (Kidney Bean Leaf Disease) dataset, with data collection beginning on July 11, 2023. An inoculation experiment for kidney bean leaf spot disease was conducted at the Taoyuanbao Experimental Base in Taigu District, Jinzhong City, Shanxi Province. After one month of growth, different leaf spot pathogens were inoculated. The experimental plot measured 88 meters in length and 10.6 meters in width, with a planting density of 8,000-9,000 plants per mu. The spacing between planting holes was set at 20–30 cm, with two plants per hole. The sowing depth was 3–5 cm, followed by soil compaction after sowing. The specific steps of the inoculation process are shown in Fig. 1. By August 2023, the plants began to show obvious symptoms of leaf spot disease. Subsequently, high-resolution cameras were used to capture images of kidney bean leaves affected by three different types of leaf spot diseases under varying backgrounds and lighting conditions.

This study represents the first attempt to construct an image dataset of kidney bean leaf spot diseases, including Bacterial Disease, Black Spot Disease, and Gray Mold. A total of 340 images of kidney bean leaves were collected, consisting of 80 images each for bacterial disease, black spot disease, and gray mold, along with 100 images of healthy leaves. To ensure data consistency, all images were resized to a resolution of 224 × 224 pixels. This dataset provides high-quality samples for the development and validation of disease detection and classification models, laying a reliable foundation for research in related fields.

Given the limited size of the original KBLD dataset, various data augmentation techniques were applied to improve the training and generalization of the models. These techniques included brightness adjustment, scaling, cropping, rotation, and flipping (horizontal and vertical) to increase the dataset size and enhance its quality. Image data augmentation is performed by adjusting brightness (brightness factor 0.7–1.3 with a 50% application probability), scaling (80–120% of the original size with a 60% probability while maintaining aspect ratio), shearing (horizontal ±15°/vertical ± 10° with a 30% probability), rotating (± 30° with reflection fill, 60% probability), and flipping (horizontal flip at 50% probability, vertical flip at 20% probability, disabled for direction-sensitive classes). Specific parameter ranges are defined for each augmentation method to control the degree of distortion. For example, scaling may randomly change the width-to-height ratio by 0.8–1.2 times, rotations avoid completely inverting the image, and brightness adjustments simulate variations in lighting conditions. To address class imbalance, a dynamic augmentation strategy is applied to the minority classes: it increases the likelihood (and intensity) of brightness adjustment (70% probability), scaling (applied twice), shearing (± 20°, 50% probability), and rotation (± 45°, 80% probability), while combining horizontal and vertical flips (total 70% probability) to maximize diversity. After augmentation, the data distribution remains balanced (inter-class differences < 10%) and effectively improved.

As a result, the augmented KBLD dataset expanded to 1020 images, with 240 images each for bacterial disease, black spot disease, and gray mold, and 300 images of healthy leaves.

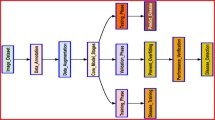

The proposed Hybrid Deep Learning Model (HDLM) framework follows the overall experimental structure illustrated in Fig. 1. According to the experimental workflow, the experiments began with the acquisition of the image dataset. The KBLD dataset, collected from the Taoyuanbao Experimental Base, contains three types of kidney bean leaf spot diseases: bacterial disease, black spot disease, and gray mold.

To enrich the KBLD dataset, image augmentation techniques were applied to expand the dataset. Bilateral filtering was used to remove noise, and K-means clustering (with K = 20) was employed for image segmentation to improve detection accuracy.

To fully prepare the dataset and enhance the model’s recognition performance, this study first applied image augmentation techniques to the KBLD dataset to increase the diversity and quantity of samples. This process involved various augmentation techniques, including rotation, scaling, flipping, and translation, to simulate different real-world conditions and improve the model’s generalization capabilities. After completing image augmentation, the dataset images underwent denoising using bilateral filtering, which effectively reduced random noise while preserving important image details by balancing edge retention and noise reduction. Finally, K-means clustering was applied to segment the denoised images, enhancing the model’s ability to recognize features in different regions. The value of K was set to 20. Through these steps, the dataset was significantly expanded and optimized, providing richer and higher-quality input data for subsequent model training.

The preprocessed KBLD dataset was used for model training and performance evaluation and was split into a training set and a testing set at a ratio of 8:2. In this study, four pre-trained deep learning models-VGG16, ResNet50, MobileNetV3, and EfficientNet-B7-were utilized for feature extraction on the KBLD dataset to improve training efficiency and standardize input image dimensions. Subsequently, the extracted features were classified using four machine learning models: Logistic Regression (LR), Random Forest (RF), Stochastic Gradient Boosting (SGB), and AdaBoost (ADB). The Optuna framework was then employed for hyperparameter tuning to further optimize classification performance. Different machine learning models require specific parameters for optimization, and the possible values for these parameters are shown in Table 1.

The specific parameter settings are as follows: Batch Size: A uniform batch size of 32 was adopted for training deep learning models such as EfficientNet-B7, MobileNetV3, ResNet50, and VGG16, striking a balance between GPU memory usage and convergence speed.

Initial Learning Rate: For most models, the initial learning rate was set to 1e-4 and gradually decayed during training. This configuration was primarily based on the sensitivity assessment of pretrained models and experimental observations.

Number of Epochs: Considering the dataset scale and the models’ actual convergence, the maximum number of training epochs was set to 50. Early stopping was employed when the training curve plateaued and the validation metrics no longer showed significant improvement. Most models reached effective convergence between 30 and 40 epochs.

Optimizer: The Adam optimizer was used for parameter updates, with default momentum hyperparameters \(\beta _1=0.9, \beta _2=0.999\). This approach maintains a relatively fast convergence speed while reducing unnecessary oscillations.

Learning Rate Scheduling: The ReduceLROnPlateau method was employed for stepwise or adaptive learning rate decay. The decay factor was set to 0.1, with adjustments made every 10–15 epochs to better explore the optimal parameter space in the later stages of training.

The Hybrid Deep Learning Model (MDLM) framework follows the workflow shown in the diagram below. The process includes the following steps: first, image preprocessing is performed using a bilateral filter to remove noise, followed by image segmentation using K-means clustering. Next, four deep learning algorithms (EfficientNet-B7, MobileNetV3, ResNet50, and VGG16) are used to extract image features, which are applied to kidney bean leaf spot disease images. Subsequently, machine learning algorithms are employed to classify the extracted features, enabling the prediction and classification of diseases. The Optuna framework is then utilized for parameter optimization to enhance model performance. Finally, the constructed KBLD dataset and publicly available datasets are used to validate the model.

Figure 2 provides a flowchart of the method, outlining the step-by-step process of this study. Each step is explained in detail below.

Image preprocessing

Joint bilateral filter

The Joint Bilateral Filter (JBF) is a popular nonlinear edge-preserving filter that has recently been widely applied in image fusion due to its effectiveness in stabilizing the weights of bilateral filters and preventing partial reversals near edges16.

JBF is an image filtering technique based on bilateral filtering that simultaneously processes spatial and color information, effectively removing noise while preserving image details. Mathematically, the filter can be expressed as:

where \( I_{JBF} (i) \) represents the output of the Joint Bilateral Filter, \( i \) and \( j \) are spatial coordinates, \( K(i) \) is the normalization factor, \( G \) denotes the guidance image, \( \sigma _S \) represents the spatial filtering intensity, and \( \sigma _r \) represents the intensity filtering strength. \( S \) is the filter window, and \( \Vert i - j\Vert \) is the Euclidean distance between pixel \( i \) and \( j \).

The guidance image \( G \) plays a critical role in guiding and constraining the filtering process, helping to better preserve edges and texture details. By leveraging information from the guidance image \( I \), the filtering algorithm can more accurately comprehend the structure of the image, enabling more precise filtering operations. The decomposition of the image using the Joint Bilateral Filter is represented by the general formula:

Image segmentation using K-means clustering

This study employs image segmentation to enhance image quality and isolate defective leaf regions, as illustrated in Figure 3. During the segmentation process, the image was divided into smaller segments to simplify processing.

K-means is an unsupervised clustering algorithm that begins by selecting \( K \) initial centroids. Each data point is then assigned to the nearest centroid, forming clusters. \( K \) clusters are formed. The cluster centers are recalculated, and the process is repeated until convergence or a predefined number of iterations is reached. The objective is to minimize intra-cluster distances while maximizing inter-cluster separation.

In each iteration, K-means updates the centroid positions: the initial centroids are randomly selected, while subsequent centroids are determined by averaging all points within each cluster from the previous iteration. The mathematical formula for this clustering technique is provided below:

where \( C_k \) represents the centroid of cluster \( k \), \( S_k \) is the set of points belonging to cluster \( k \), and \( x_i \) denotes a data point.

here, \( |s_m - t_n| \) represents the Euclidean distance between the point \( s_m \) and the centroid \( t_n \). During all \( k \) iterations, these points belong to the \( m \)-th cluster of all clusters \( l \).

In red kidney bean leaf disease detection, selecting K=20 as the K-means clustering parameter offers several advantages. First, disease features (such as rust spots with diameters of 0.5–3 mm) require balancing detail retention and noise suppression, allowing the algorithm to capture tiny lesions while avoiding background interference (validated by the background segmentation algorithm in Reference 3). Second, color space analysis indicates a significant color difference between the green channel (G: 80–180) of healthy leaves and the yellow-brown characteristics (R/G > 1.2) in diseased areas; 20 cluster centers can effectively separate these color ranges. Finally, experiments show that when K > 25, over-segmentation occurs (leaf veins are mistakenly identified as independent clusters). In contrast, K = 20 not only covers the seven main color levels of leaves (including three types of disease-related colors) but also keeps the number of clusters within the optimal range for feature extraction (Reference 5 shows the within-cluster variance coefficient of variation CV < 15%), thereby enhancing the robustness of subsequent classification models.

In this study, we conducted experiments on collected red kidney bean leaves. We gathered 400 leaf images-covering healthy leaves and three types of diseased leaves-and applied a segmentation algorithm to remove disturbances such as soil and weeds, focusing on the main leaf area. The experimental parameter settings are shown in the Table 2 below.

Based on the parameters above, we conducted leaf segmentation experiments. The segmentation accuracy is shown in the Table 3 below:

The experimental results show that selecting K = 20 as the clustering parameter for red kidney bean disease detection offers significant advantages. In terms of lesion detection sensitivity, K = 20 increases the detection rate for IOU > 80% by 8.3 percentage points (p < 0.01) compared to K = 15, with a 92% retention of high-frequency lesion contour components-better than K = 15 (85%) and K = 25 (88%). In terms of computational efficiency, compared to K = 25 it saves 21% of processing time (0.67simage), which meets field requirements. Meanwhile, LAB color space analysis shows that K = 20 achieves a 95% completeness in segmenting regions with a color difference \(\Delta \textrm{E}>5\), effectively preventing healthy tissue from being misclassified. This parameter strikes an optimal balance between detail preservation (leaf spot diameter 0.5–3 mm) and computational load, confirming its applicability in specific scenarios and enhancing segmentation accuracy.

Image feature extraction

To improve the accuracy of the algorithm, this study utilized four commonly used deep learning models: EfficientNet-B7, MobileNetV3, ResNet50, and VGG16.

EfficientNet-B7

EfficientNet (EfNet) is an advanced pre-trained convolutional neural network (CNN) that achieves an accuracy of 84.49% on the ImageNet dataset with 66 million parameters. As shown in Fig. 4, the EfficientNet-B7 model was selected for this study due to its strong performance on ImageNet. The feature maps extracted from this model were further utilized to train plant disease prediction models using traditional machine learning classifiers, as detailed in the next section.

VGG16 model

The VGG16 model uses max-pooling layers as nodes to divide the convolutional layers into five sections. The input image information for each section is outlined as follows:

-

In the first section, the input size is 224 × 224 × 64 representing the initial image resolution with 64 channels, typically corresponding to the output of the early convolutional layers responsible for extracting basic features.

-

In the second section, the input size is reduced to 112 × 112 × 128, indicating that the height and width are halved while the number of channels doubles to 128, capturing more complex features.

-

Further, the third section operates on an input size of 56 × 56 × 256, where the spatial dimensions are halved again, and the number of channels increases to 256, reflecting deeper feature extraction.

-

The fourth section processes input with a size of 28 × 28 × 512, continuing the pattern of reducing spatial size while increasing depth to 512 channels, enabling a more refined understanding of the input data.

-

Finally, the fifth section handles input with a size of 14 × 14 × 512, representing a compact representation of the image, with high-level abstract features distributed across 512 channels.

To overcome the learning difficulties caused by differences in defective feature representations, Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) was integrated after the convolutional layers in the initial sections. Additionally, Inception network structures were introduced after the convolutional layers in the second and third sections to enhance the network’s width and nonlinear learning capacity, improving the extraction of defective information. Batch Normalization (BN) layers were applied after each convolutional layer to prevent gradient issues, accelerate training, and enhance generalization capabilities. The overall network structure of VGG16 is shown in Table 4. According to Table 4:

-

Receptive Field Size: Refers to the size of the image region perceived by each convolutional kernel. For example, a size of 3 × 3 indicates that the convolutional kernel covers a 3 × 3 pixel area. The receptive field determines the range of local information the network can perceive.

-

Padding: Controls how the image boundaries are processed during convolution operations. A value of 1 means adding 1 pixel of zero padding to the input image’s boundaries to maintain the same output size after convolution.

-

Stride: Indicates the step size of the convolutional kernel as it slides over the image. A stride of 1 means the kernel moves 1 pixel at a time, while a stride of 2 moves 2 pixels per step. Larger strides reduce the output size and computational load.

-

Number of Channels: Represents the number of feature maps produced by the convolutional layer. Each convolutional layer generates multiple feature maps, with each map representing different feature dimensions. The number of channels typically increases as the network depth increases.

-

Conv1 + BN × 2: The first convolution and batch normalization layer, using two 3 × 3 convolutional kernels to generate 64 channels.

-

CBAM: The Convolutional Block Attention Module processes the 64 channels from the previous layer.

-

Maxpooling: A pooling layer using 2 × 2 pooling operations with a stride of 2, which reduces the size of the feature maps while retaining important information.

-

Inception1/Inception2: Inception network structures use combinations of multiple convolutional kernels (e.g., 1 × 1, 3 × 3, 5 × 5) to extract multi-scale features, enhancing the model’s nonlinear learning capabilities.

-

Fc1, Fc2, Fc3: Fully connected layers. After multiple convolutional layers, the feature maps are flattened and passed through fully connected layers for classification. Fc1, Fc2, and Fc3 represent three fully connected layers with 4096, 4096, and 1000 output nodes, respectively.

This study designed a network architecture combining VGG16, CBAM, and Inception modules for feature extraction and classification of defect images. First, the dataset images were downsampled to a standard input size of 224 × 224 pixels to ensure uniformity and compatibility with the VGG16 network. Subsequently, the ImageDataGenerator function in the Keras library was used for data augmentation, including operations such as rotation, shearing, scaling, and flipping, to enhance dataset diversity, improve the model’s generalization ability, and reduce overfitting. During the feature extraction phase, the network employed the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) to focus on critical regions of the image and incorporated Inception network structures to extract deep features at multiple scales. These designs allowed the network to better capture complex defect information and enhanced the representation capacity of features. For the classification component, the pre-trained VGG16 model was used in conjunction with machine learning classifiers for final classification and recognition. VGG16 effectively learned high-level features of the images through multiple convolutional, pooling, and fully connected layers, while the classifiers further processed these features to achieve precise defect classification. In summary, the network design in this study, combining deep convolutional networks and attention mechanisms, achieved superior performance in feature extraction and classification tasks for defect images, significantly improving defect recognition accuracy and network robustness.

ResNet50 network structure

As shown in Fig. 5, the ResNet50 architecture progresses from the input stage through stages 0 to 4 and finally reaches the output stage. In stage 0, an input of size 3 × 224 × 224 is processed by 64 convolutional filters, each measuring 7 × 7, with a stride of 2, producing 64 output channels. This is followed by Batch Normalization (BN) to improve training speed and stabilize gradients, a Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function, and a max-pooling layer with a filter size of 3 × 3 and a stride of 2. The output size is reduced to (64,56,56), representing the transformation from the initial input.

BINK1 and BINK2 structures

BINK2: This block has two parameters: C (input channels) and W (input size). The input passes through three convolutional blocks, each comprising Batch Normalization (BN) and ReLU activation, to produce an output. This output is then added to the input, and the combined result undergoes ReLU activation to generate the final output of BINK2.

BINK1: This block has four parameters: C (input channels), W (input size), C1 (output feature maps), and“S”(stride).

-

When S = 1, the input and output sizes remain unchanged, indicating no down-sampling.

-

If C = C1, a1\(\times \)1 convolution on the left side maintains the number of channels.

-

In later stages, C = 2 \(\times \) C1, indicating that the channels are reduced by a1\(\times \)1 convolution layer.

Due to the inconsistency between the input and output channels in BINK1, the right side first adjusts the output channels through a convolution layer, represented as G(x). This adjustment ensures compatibility between F(x) and G(x).

MobileNetV3

The MobileNetV3 Large algorithm, developed by Google, is a lightweight and portable model that combines depthwise separable convolutions, linear bottlenecks, inverted residual structures, and the SE attention mechanism, as shown in Table 5.

In the table:“NL”indicates the nonlinear activation function,“HS” represents the Hard Swish activation function,“RE”stands for the ReLU function,“s”denotes the stride,“\(\surd \)”indicates that the SE attention mechanism is included in the corresponding Bneck layer.

When humans observe objects, they selectively focus on important information after holistic observation while ignoring less significant details. The attention mechanism in computer vision follows a similar approach, enhancing information processing efficiency and accuracy by assigning higher weights to critical information. Zhang et al. employed a dual attention mechanism combining feature grouping with spatial attention mechanisms and bottleneck attention modules. This mechanism introduces feature grouping and channel permutation based on spatial and channel attention17.

Image classification

This study adopts four classifiers-Logistic Regression (LR), Random Forest (RF), AdaBoost (ADB), and Stochastic Gradient Boosting (SGB)-to detect plant leaf diseases. A detailed introduction to each model is provided below.

Logistic regression (LR)

Logistic Regression (LR) is a classification algorithm utilizing regression analysis. Unlike linear regression, which handles numerical prediction, LR applies the sigmoid function to convert outputs into probability values. It is a simple yet effective model, particularly suitable for datasets with linearly separable boundaries. The mathematical expression for LR is as follows:

To map the output value to the probability range [0, 1], the sigmoid function is applied, enabling its interpretation as the posterior probability of the output class. This function is defined as:

The model parameters can be determined by minimizing the negative log-likelihood function, expressed as:

The parameters \(\theta \) are then computed using the gradient descent method.

Random forest (RF)

Random Forest (RF) is a versatile machine learning algorithm developed by Leo Breiman in 2001. It is based on the bagging method, which combines several weak classifiers into an ensemble. The CART (Classification and Regression Trees) decision tree algorithm used in RF employs the Gini Index to select splitting attributes. The Gini value measures the purity of dataset DD, where a smaller Gini Index indicates higher purity of the dataset.

The Gini Index (D) represents the probability of randomly selecting two samples from different classes; the smaller the Gini Index (D), the higher the purity of the dataset. The Gini Index is used for feature selection by measuring the impurity of features. For example, if a specific value a of a feature divides the dataset into subsets, the Gini Index is calculated as follows:

The reduction in data impurity after splitting by feature A is given by:

The core of the Random Forest algorithm lies in its decision trees; different decision trees are constructed and trained based on the original data. This approach ensures the generalization and applicability of the data, making it particularly effective when handling large datasets. Additionally, during the construction of each decision tree, the features used are randomly selected from all features in the training samples. This method enhances the classification capability of the decision trees and helps prevent overfitting.

AdaBoost (ADB)

AdaBoost is one of the most widely used Boosting algorithms, consisting of two parts: the ensemble part and the iterative part. In the ensemble part, multiple weak learners are linearly combined to form a strong learner, which can be expressed by the following formula:

In the formula, \(h_t(x)\) represents the weak learner, \(\alpha _t\) denotes the weight matrix of the weak learner, \( H(x) \) is the strong learner obtained by the linear combination of weak learners, and \( T \) is the maximum number of iterations.

In the iterative step, the strong learner generated in the previous iteration is used to generate a new strong learner in the subsequent iteration. The formula is as follows:

In the formula, \( H_{t-1}(x) \) represents the strong learner obtained from the \( (t-1) \)-th iteration, and \( H_t(x) \) represents the strong learner obtained from the \( t \)-th iteration. Therefore, in each iteration, a new weak learner \( h_t(x) \) and its corresponding weight matrix \( \alpha _t \) need to be solved.

During the iteration process, the training error \( \epsilon _t \) of the weak learner is defined as follows:

When the weak learner is a classification model, Eq. (12) provides the error calculation formula, while when the weak learner is a regression model, Eq. (13) gives the error calculation expression. During the iteration process, the weight matrix of the weak learner is updated as follows:

In the equation, \( I \) is the identity matrix.

The weight matrix of the training samples is continuously adjusted during the iteration process according to the following formula:

In Equations (15) and (16), \( C_t \) is the normalization constant. Equations (15) and (16) are the iterative formulas for the weight matrix of classification and regression models, respectively. The final strong learner is as follows:

In Equation (17), \( \Gamma (h_t(x_i) = k) \) represents the probability that the classifier assigns the \( i \)-th sample to the \( k \)-th class. This function selects the class with the highest probability as the output of the strong learner. Equations (17) and (18) describe the ensemble strategies for sub-learners in classification and regression models, respectively.

Stochastic gradient boosting (SGB)

Stochastic Gradient Boosting (SGB) is an extension of the original gradient boosting method, retaining the overall idea of the original method15.

If the model undergoes \( m \) iterations, the loss function is represented as \( \Phi \). Optimization is performed using the stochastic gradient boosting method, and the process is as follows:

In the original gradient boosting algorithm, the error between the predicted value and the actual value, called the“pseudo-residual,” is approximated by the negative value of the gradient of the loss function at the current ensemble output. By fitting the next base learner to the pseudo-residuals of all training samples, the performance of the ensemble model can be iteratively improved. Assume the pseudo-residual for the \( m \)-th iteration is:

Since the original gradient boosting method fits the pseudo-residuals of all samples in the initial training set to the next weak learner in each training iteration, it significantly increases the complexity of training time and the risk of overfitting. To address this issue, Friedman introduced randomness into the successive iterations of the gradient boosting algorithm, thereby developing the Stochastic Gradient Boosting (SGB) algorithm18.

Specifically, in each iteration, only a randomly sampled subset is used to fit the next weak learner. Let the initial training set be \( S = \{(x, y)\} \), and let \( \{\pi (i)\} \) be a random permutation from 1 to \( n \), where \( n' \) is the size of the random subset with \( n' < n \). Then, the randomly sampled subset can be represented as \( \{(x_{\pi (i)}, y_{\pi (i)})\}_{i=1}^{n'} \).

After obtaining the random subset, the pseudo-residuals of the randomly sampled subset in the \( m \)-th iteration can be expressed as:

After calculating the pseudo-residuals, the main goal of the newly introduced weak base learner is to fit these pseudo-residuals, thereby reducing the loss function in the steepest direction. Specifically, this process involves using the original samples as input and the pseudo-residuals as the target attribute.

Model parameter optimization

The Optuna framework is used for hyperparameter optimization, aiming to develop machine learning classification models with broad application potential. Optuna is a new open-source framework specifically designed for hyperparameter optimization, initially proposed by Akiba et al. in 2019 [14]. Optuna provides an efficient and flexible optimizer that can adaptively optimize different machine learning models and tasks. Unlike traditional optimization processes defined by configuration files, Optuna adopts a “define-by-run”approach, allowing users to dynamically define the search space and optimization process, making it suitable for complex optimization tasks.

Optuna’s unique structure and optimization methods give it significant advantages in parameter tuning. The framework also supports distributed computing, improving efficiency by allowing the optimization process to run on multiple nodes.

The architecture of the Optuna framework is shown in Fig. 6. During the hyperparameter optimization process, the Optuna API provides an interface for executing the objective function, enabling access to and utilization of historical study data stored in shared storage. The objective function can run independently, and the learning progress during optimization is updated to shared storage, achieving efficient data sharing and collaborative optimization. This design not only ensures the independence of optimization tasks but also enhances the overall efficiency and coordination of the optimization process through the shared storage mechanism.

Experimental results and analysis

Experimental environment

This chapter introduces a novel MDLM (Multi-Deep Learning Model) method for detecting red kidney bean leaf spot disease using image-based datasets. The experimental setup is configured as follows: Python version 3.9 is used as the programming language, and the GPU employed is the NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090, paired with a 12th Gen Intel Core i7-12700K CPU and 32GB DDR4 RAM. The experiments are conducted on the Windows 11 operating system, utilizing the PyTorch 1.10 deep learning framework.

Experimental setup

This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed MDLM method for prediction of red kidney bean diseases based on images. To achieve this goal, a dataset was collected from the Taoyuanbao planting base, as described in the previous section. Various image preprocessing and segmentation techniques were applied to enhance the quality of the dataset. The MDLM method was then employed for experimentation, which combines feature extraction from four deep learning models with machine learning (ML) classifiers (LR, RF, ADB, and SGB) to obtain the final results.

Experiments on the KBLD dataset

This study aims to develop a computer model for automatically predicting red kidney bean leaf spot disease using images. The KBLD dataset was collected under actual agricultural conditions, featuring images with diverse backgrounds and lighting. Image preprocessing and segmentation techniques were applied to improve data quality and size. The proposed MDLM method was then implemented on this enhanced dataset, combining four deep learning models with ML classifiers for disease prediction. Table 4 presents the parameter optimization results for various ML classifiers using the Optuna framework, while Table 6 demonstrates the performance of the method in terms of accuracy and F1 score.

Acc curve comparative analysis

To demonstrate the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed method, this study conducted a comparative analysis by combining VGG16, ResNet50, MobileNetV3, and EfficientNet-B7 with ADB, SGB, RF, and LR, respectively, based on the kidney bean leaf spot segmentation dataset. The Acc curves of these combinations are shown in the Figs. 7, 8, 910.

In the instance segmentation experiments, the ACC value is commonly used to evaluate the overall accuracy of the model. As shown in Figs. 7, 8, 9 and 10, the Acc value of EfNet-B7-SGB in the proposed model is higher than that of other models, demonstrating that the global accuracy of EfNet-B7-SGB in the kidney bean leaf spot prediction model is superior to other models.

LOSS curve

To better observe the loss reduction of each model, this study compared the classification loss curves of multiple models, as shown in Figs. 11, 12, 13 and 14.

Figures 11, 12, 13 and 14 shows the variation in loss values for different models. It can be observed that in the SGB model, the loss decreases faster than in the other three models. After the curves stabilize, the SGB model achieves a lower loss value. Notably, the EfNet-B7-SGB model proposed in this study has a lower loss value compared to other models, demonstrating that its classification accuracy is higher than the others.

Analysis of different average accuracy

It is explicitly stated that the original training set is divided using 5-fold cross-validation. After each fold is trained, the model’s performance is evaluated on the retained validation set, thereby making the most of the limited data and reducing the model’s dependence on any specific data distribution.

Moreover, in the results analysis section, we provide comparisons of various metrics-such as average accuracy and F1-score-across the folds, illustrating the role cross-validation plays in reliably assessing model performance.

To further validate the experiments, this study implements both 5-fold and 10-fold cross-validation. In 5-fold cross-validation, the training set is divided into 5 subsets; one subset serves as the validation set, while the remaining 4 subsets are used for training. In 10-fold cross-validation, the training set is split into 10 subsets following the same process. After each fold’s training is completed, the reserved validation set is used to evaluate the model. The average value and standard deviation of each metric (e.g., accuracy, F1-score) across the folds are then taken as the model’s overall performance under that particular fold partitioning.

Among these, the results of the 5-fold cross-validation are shown in Table 7, including each model’s average accuracy and average F1-score (presented in percentages or decimal form) along with the corresponding standard deviations.

Overall, EfficientNet-B7 achieves an average accuracy of around 92.5% and an average F1 score of 0.93, ranking as the best-performing model among all. ResNet50 follows closely, with an average accuracy exceeding 87% and an F1 score of approximately 0.86. VGG16 lags slightly behind ResNet50 but still maintains an accuracy above 85%. MobileNetV3 performs relatively weaker at 84.6% accuracy.

From the perspective of standard deviation, the fluctuation range for all models (± 1.2% to ± 2.0%) remains within a normal range, indicating stable performance under 5-fold cross-validation. When the dataset is further divided into 10 folds for cross-validation, the final average performance of each model is shown in the following Table 8.

Under 10-fold cross-validation, the average accuracy of EfficientNet-B7 increases to about 93.2%, while its F1 score remains at 0.93, further confirming its leading position among the models. ResNet50 also shows a slight improvement; its accuracy and F1 score are generally consistent with the previous 5-fold results, indicating stable performance even with a finer fold partition. VGG16 and MobileNetV3 demonstrate a marginal improvement compared to the 5-fold results, but the overall gap remains evident, falling short of ResNet50 and EfficientNet-B7. All models exhibit standard deviations between ±1% and ±1.3%, demonstrating that 10-fold cross-validation provides an even more stable assessment of model consistency across different data subsets. By comparing multi-fold average metrics , it is possible to obtain a more stable and objective performance evaluation on limited data. Relying on a single partition may lead to fluctuations caused by uneven data distribution or sample bias, while multi-fold validation effectively mitigates this issue.

Classification results for different types of kidney bean leaf spot diseases

This study focuses on the automatic recognition and classification of three types of kidney bean leaf spot diseases: bacterial disease, black spot disease, and gray mold. We compared the performance of deep learning models (VGG16, ResNet50) and ensemble learning methods (Random Forest—RF, AdaBoost—ADB, and Stochastic Gradient Boosting—SGB).

The experimental results are shown in Table 9, which presents the accuracy and F1-score of different machine learning models (Logistic Regression—LR, Random Forest—RF, AdaBoost—ADB, and Stochastic Gradient Boosting—SGB) when combined with various deep learning models (VGG16, ResNet50, MobileNetV3, and EfficientNet-B7) for the classification of three plant diseases: bacterial disease, black spot disease, and gray mold.

To comprehensively evaluate the recognition performance of four convolutional neural networks (VGG16, ResNet50, MobileNetV3, EfficientNet-B7) and four classifiers (LR, RF, ADB, SGB) on bean leaf diseases (bacterial disease, black spot disease, and gray mold), this study recorded each model-classifier combination’s accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-Score. As shown in Table 9:

VGG16: In the classification tasks for the three diseases, the accuracy of VGG16 mostly ranges from 80% to 88%, and the F1-Score remains around 0.80 to 0.88. Taking the LR classifier as an example, the accuracy for bacterial disease is about 80.14%, with an F1-Score of 0.80; the accuracy and F1-Score for black spot disease and gray mold also stay around 80%. Overall, VGG16 shows moderately stable performance, but its recognition accuracy is somewhat lower compared to other deeper or more optimized networks.

ResNet50: Compared to VGG16, ResNet50 achieves accuracy typically between 81% and 88% across different diseases, with F1-Scores also reaching 0.80-0.88. For instance, using the LR classifier, the accuracy for bacterial disease is about 81.89% and the F1-Score is 0.80; accuracy for black spot disease and gray mold remains around 82-83%, with the highest F1-Score reaching 0.86. Since ResNet50 adopts a deeper network structure and residual learning mechanism, it demonstrates better feature extraction and is more effective at identifying the three types of lesions on bean leaves.

MobileNetV3: Overall accuracy and F1-Scores for MobileNetV3 are slightly lower than those of VGG16 and ResNet50. Although it can reach 85-86% accuracy under certain classifiers (e.g., SGB), its average performance still lags behind the other two networks. For instance, using the LR classifier, the accuracy for bacterial disease is around 78.60% with an F1-Score of 0.78, whereas black spot disease and gray mold perform only slightly better, remaining in the 79-80% range. MobileNetV3 places emphasis on lightweight design and speed, so its relatively shallow depth and limited network capacity might restrict the ability to capture fine-grained lesion features.

EfficientNet-B7 (EfNet-B7): Among all experimental combinations, EfficientNet-B7 consistently delivers the best results, with accuracy often exceeding 90% and F1-Scores reaching 0.92-0.97. Taking the LR classifier as an example, the accuracy for bacterial disease is around 91.98%, with an F1-Score of 0.93; the accuracy for the other two diseases remains in the 92-93% range. When using RF, ADB, or SGB classifiers, EfNet-B7 can reach accuracy levels of 94-96%, and its F1-Score can further rise to 0.95-0.97, which significantly outperforms the other networks.

Explanations for EfficientNet-B7’s Advantages Compound Scaling Strategy: By proportionally expanding network depth, width, and input resolution, the model effectively balances capacity and generalization performance. Unlike simply increasing depth or width alone, compound scaling mitigates overfitting while maintaining computational efficiency.

Efficient Feature Extraction (MBConv Module): Drawing from the MobileNet series, the network incorporates depthwise separable convolution units (MBConv), which reduce parameter counts while enhancing feature extraction accuracy. This significantly improves the ability to recognize subtle lesions on bean leaves.

High-Resolution Input: EfficientNet-B7 supports higher-resolution inputs, thereby retaining more fine-grained details. This facilitates mapping subtle color and morphological differences within the same disease category into the feature space, helping the model better distinguish visually similar lesions.

Pretraining and Transfer Learning: Weights pretrained on large-scale datasets (e.g., ImageNet) were fine-tuned on the KBLD dataset, endowing the model with rich generalizable feature representations. Compared with training from scratch, transfer learning can still achieve stable high accuracy and recall rates on a relatively small dataset, reducing the risk of overfitting.

Activation Function and Regularization: The Swish activation function ensures smoother gradient propagation, aiding in model convergence. Properly applied dropout and other regularization measures further boost the model’s generalization capacity, even when scaling up.

The experimental results show that EfficientNet-B7 is the top performer in recognizing bean leaf diseases (bacterial disease, black spot disease, and gray mold), typically exceeding 90% accuracy and achieving F1-Scores of up to 0.92-0.97, outperforming VGG16, ResNet50, and MobileNetV3. ResNet50 follows closely as another deep network framework, showing relatively high recognition rates in some tasks. VGG16 maintains mid-level performance, though its architecture is comparatively outdated. MobileNetV3, while lightweight and efficient, is somewhat less effective for high-precision requirements in fine-grained lesion classification.

Drawing on multiple aspects-including network structure, feature extraction capacity, input resolution, and transfer learning strategies-it is evident that the combination of compound scaling and efficient convolution modules yields clear benefits for identifying subtle lesions. In conclusion, EfficientNet-B7 proves to be the best model in this study, fully demonstrating its efficiency and generalization capabilities in plant disease classification tasks, and providing a valuable technical reference for future disease diagnosis research.

Compared to some publicly available, large-scale plant disease datasets, the KBLD dataset constructed in this study is relatively small in size and was collected under more limited conditions. Although techniques such as data augmentation and segmentation were employed, it remains difficult to fully capture the variations in lesion features caused by different growth stages, lighting conditions, and leaf varietal differences.

Model Specificity and Generalization Capability: Some studies have utilized larger-scale or cross-species pretrained models, which, after fine-tuning on a substantial quantity of images, can learn not only general image features but also converge quickly for specific disease tasks. This approach may offer slightly better accuracy and robustness.

In future work, we plan to collect diseased leaf images from more real-world field environments and diverse planting regions, and to integrate them with other publicly available data resources. This will further expand the training set’s size and diversity, thereby enhancing the model’s generalization performance.

Conclusion

This study addresses the challenges of data scarcity and inadequate quality in the field by constructing a new red kidney bean leaf spot disease dataset, supplemented with techniques such as data augmentation, denoising filtering, and K-means clustering. Compared to existing public datasets, this dataset not only features greater diversity and clarity but also provides a solid training foundation for integrating deep learning models with traditional machine learning algorithms. Experimental results indicate that the EfficientNet-B7 model excels in feature extraction, while the SGB algorithm achieves optimal results at the classification stage, demonstrating high practicality and generalization capability. Although the classification accuracy achieved in this study has not yet fully surpassed existing methods, its value lies in the fact that it has been tested on a new dataset and within a novel framework, offering significant reference value.

Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of this study in the following aspects: First, the dataset remains relatively small, which may constrain the model’s generalization and adaptability. Second, the current data augmentation strategies are still not diverse enough to fully capture the variation in lesions with respect to morphology, illumination, and viewing angles. To further enhance model performance and robustness, future research should focus on expanding the dataset size and refining data augmentation methods. Additionally, the introduction of more advanced feature extraction and classification approaches would be worth considering, to develop a more efficient and accurate detection technique for red kidney bean leaf spot disease.

In real-world field applications, hardware resources, model size, real-time needs, and environmental adaptability must be comprehensively considered. Even on high-performance GPU platforms, while inference speed may meet typical real-time monitoring requirements, large-scale field inspections or latency-sensitive scenarios make lightweight models and inference efficiency particularly critical. By employing model pruning, quantization, and deployment on hardware platforms capable of withstanding outdoor conditions, inference time can be further reduced without compromising accuracy, and device adaptability can be enhanced. Furthermore, edge computing or distributed inference solutions could be explored to tackle issues such as unstable network connections, augmented by image preprocessing and multi-sensor fusion, in order to handle varying lighting and environmental conditions.

In summary, this study has made preliminary progress in data construction and model design, providing a viable technical means for agricultural disease monitoring. Future work should continue to expand data size and diversity, refine strategies for integrating deep learning with traditional algorithms, and explore emerging methods such as Neural Architecture Search (NAS), hierarchical inference, and multimodal information fusion. These efforts aim to better fulfill the requirements of field monitoring and disease diagnosis. By further balancing and innovating around speed, accuracy, and robustness, it is hoped that more efficient and stable intelligent support can be provided for agricultural production.

Data availability

Data is provided within supplementary information files

References

Sharma, V., Tripathi, A. K. & Mittal, H. Dlmc-net: Deeper lightweight multi-class classification model for plant leaf disease detection. Eco. Inform. 75, 102025 (2023).

Daniya, T. & Vigneshwari, S. Rice plant leaf disease detection and classification using optimization enabled deep learning. J. Environ. Inf. 42, 25 (2023).

Khan, F. et al. A mobile-based system for maize plant leaf disease detection and classification using deep learning. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1079366 (2023).

Badiger, M. & Mathew, J. A. Tomato plant leaf disease segmentation and multiclass disease detection using hybrid optimization enabled deep learning. J. Biotechnol. 374, 101–113 (2023).

Demilie, W. B. Plant disease detection and classification techniques: A comparative study of the performances. J. Big Data 11, 5 (2024).

Bischl, B. et al. Hyperparameter optimization: Foundations, algorithms, best practices, and open challenges. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 13, e1484 (2023).

Pacal, I. et al. A systematic review of deep learning techniques for plant diseases. Artif. Intell. Rev. 57, 304 (2024).

Kunduracioglu, I. & Pacal, I. Advancements in deep learning for accurate classification of grape leaves and diagnosis of grape diseases. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 131, 1061–1080 (2024).

Pacal, I. Enhancing crop productivity and sustainability through disease identification in maize leaves: Exploiting a large dataset with an advanced vision transformer model. Expert Syst. Appl. 238, 122099 (2024).

Pacal, I. & Işık, G. Utilizing convolutional neural networks and vision transformers for precise corn leaf disease identification. Neural Comput. Appl. 37, 2479–2496 (2024).

Kunduracıoğlu, İ & Paçal, İ. Deep learning-based disease detection in sugarcane leaves: Evaluating efficient net models. J. Oper. Intell. 2, 321–235 (2024).

Ahmed, K., Shahidi, T. R., Alam, S. M. I. & Momen, S. Rice leaf disease detection using machine learning techniques. In 2019 International Conference on Sustainable Technologies for Industry 4.0 (STI), 1–5 (IEEE, 2019).

Thangaraj, R., Anandamurugan, S., Pandiyan, P. & Kaliappan, V. K. Artificial intelligence in tomato leaf disease detection: A comprehensive review and discussion. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 129, 469–488 (2022).

Kaur, N. & Devendran, V. A novel framework for semi-automated system for grape leaf disease detection. Multimed. Tools Appl. 83, 50733–50755 (2024).

Shoaib, M. et al. An advanced deep learning models-based plant disease detection: A review of recent research. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1158933 (2023).

Sunil, C., Jaidhar, C. & Patil, N. Cardamom plant disease detection approach using efficientnetv2. IEEE Access 10, 789–804 (2021).

Zhang, Y., Zhao, P., Ma, Y. & Fan, X. Multi-focus image fusion with joint guided image filtering. Signal Process. Image Commun. 92, 116128 (2021).

Zhao, Y. et al. Plant disease detection using generated leaves based on doublegan. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinf. 19, 1817–1826 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFD1600603-02, 2021YFD1600603-03); the Major Special Science and Technology Projects in Shanxi Province (202301140601016); and the Shanxi Modern Agricultural Industry Technology System (coarse cereals) (2024CYJSTX03-03).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Writing-original draft; Q.W.: Methodology (optimization), Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing-review & editing; Y.S.: Literature review, Resources, Validation, Discussion B.J.: Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing-editing & proofreading; M.F.*: Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing-review & editing, Correspondence.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Wang, Q., Su, Y. et al. Detection of kidney bean leaf spot disease based on a hybrid deep learning model. Sci Rep 15, 11185 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93742-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93742-7