Abstract

Diminished signaling via insulin/insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) axis is associated with longevity in different model organisms. IGF-1 gene is highly conserved across species, with only few evolutionary changes identified in it. Despite its potential role in regulating lifespan, no coding variants in IGF-1 have been reported in human longevity cohorts to date. This study investigated the whole exome sequencing data from 2,108 individuals in a cohort of Ashkenazi Jewish centenarians, their offspring, and controls without familial longevity to identify functional IGF-1 coding variants. We identified two likely functional coding variants IGF-1:p.Ile91Leu and IGF-1:p.Ala118Thr in our longevity cohort. Notably, a centenarian specific novel variant IGF-1:p.Ile91Leu was located at the binding interface of IGF-1–IGF-1R, whereas IGF-1:p.Ala118Thr was significantly associated with lower circulating levels of IGF-1. We performed extended all-atom molecular dynamics simulations to evaluate the impact of Ile91Leu on stability, binding dynamics and energetics of IGF-1 bound to IGF-1R. The IGF-1:p.Ile91Leu formed less stable interactions with IGF-1R’s critical binding pocket residues and demonstrated lower binding affinity at the extracellular binding site compared to wild-type IGF-1. Our findings suggest that IGF-1:p.Ile91Leu and IGF-1:p.Ala118Thr variants attenuate IGF-1R activity by impairing IGF-1 binding and diminishing the circulatory levels of IGF-1, respectively. Consequently, diminished IGF-1 signaling resulting from these variants may contribute to exceptional longevity in humans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diminished signaling via insulin/insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) axis has been associated with increased lifespan in various model organisms1,2,3,4. However, the role of insulin/IGF-1 axis in human aging has not been confirmed. Previously, two rare heterozygous coding variants in IGF-1R, a gene that encodes the IGF-1 receptor (IGF1-R), were found to be enriched among Ashkenazi Jewish individuals with exceptional longevity and were demonstrated to result in diminished activity of the IGF-1R5. However, IGF-1 is a highly conserved gene and the few missense mutations identified in IGF-1 to date have been associated with growth failure and developmental abnormalities6,7,8. To our knowledge, no coding variants in the IGF-1 have been associated with longevity in humans.

IGF-1 mediated downstream signaling is dependent on stable binding of IGF-1 with its receptor IGF-1R. Studies have shown that coding variants located at the interface of IGF-1–IGF-1R attenuated the binding activity of IGF-19,10. The IGF-1R is a functional dimer. Each protomer of IGF-1R includes the L1 (leucine-rich repeat domain 1), CR (cysteine-rich domain), L2 (leucine-rich repeat domain 2), FnIII-1, -2, -3 (fibronectin type III domains), transmembrane (TM), a ∼30 amino acid juxtamembrane region, and kinase domains. Two of these protomers are connected by numerous disulfide bonds, creating a stable, covalent dimer11. For clarity, the domains in protomers 1 and 2 are indicated as L1–FnIII-3, and L1′–FnIII-3′ (indicated by prime), respectively, throughout the manuscript. Ligand binding to the extracellular domains (ECDs) of IGF-1R triggers receptor kinase activation that results in the phosphorylation of numerous substrates and the initiation of distinct signaling pathways12. Members of the insulin receptor (IR) family stand out among receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) by forming dimers composed of αβ subunits, even in the absence of ligands13,14. Each αβ dimer possesses two ligand-binding sites. Each site comprises two distinct partial sites referred to as site 1 and site 2. Site 1 is formed by residues on L1 from one subunit and residues on the αCT′ helix of the other subunit 15,16,17,18. The primary binding site of IGF-1 on the IGF-1R is composed of L1 domain and α-CT 11,19,20,21, while a secondary sub-site (1b), formed by residues at the membrane distal end of FnIII-1′, has recently been observed in the active IGF-1R dimer11. However, there is limited understanding regarding the stability and significance of polar and hydrophobic contacts established between wild-type and mutant IGF-1 and IGF-1R. Furthermore, regulation of IGF-1 signaling involves alternative splicing that results in different IGF-1 precursors which vary in the structure of their carboxy-terminal extension peptides (E-peptides) and the length of their amino-terminal signal peptides22. Different splicing variants and synonymous variants have been shown to alter the expression, function, and processing of mature IGF-123,24,25.

Multiple three-dimensional atomic-level structures of IGF-1 bound to IGF-1R have been successfully elucidated11,20,21. These resolved structures offer profound insights into macromolecular structure and intermolecular interactions. Yet, molecular recognition and binding involve dynamic processes. Molecular dynamic (MD) simulations often serve as a complement to conventional structural studies, allowing for the examination of these processes at atomic-level26,27. These simulations offer insights into the stability of macromolecular complexes, the flexibility of interacting subunits, and the interactions among residues at the binding interface.

In this study, we investigated the impact of longevity-associated IGF-1 coding variants identified in individuals with exceptional longevity. We associated IGF-1 variants with serum IGF-1 levels and determined the effect of interfacial variant IGF-1:p.Ile91Leu on stability, binding dynamics, and energetics of IGF-1 bound to IGF-1R by performing extended MD simulations. The main aim of this study was to uncover both commonalities and disparities in the dynamic interactions between wild-type and longevity-associated mutant IGF-1, as well as pinpoint residues that may play a pivotal role in maintaining the integrity of this interface in the presence of studied variants.

Results

Identification of functional variants in IGF-1 gene

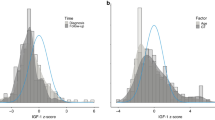

We studied the whole exome sequencing data from 2,108 individuals in a cohort of Ashkenazi Jewish centenarians, offspring of centenarians, and offspring of parents without familial longevity to identify all coding variants in the IGF-1 gene. The characteristics of the longevity cohort are summarized in Supplementary Table S1. Only two coding variants were identified in our cohort and both had minor allele frequency (MAF) ≤ 0.01 (Fig. 1A). The functional nature of the coding variants was defined using combined annotation dependent depletion (CADD) score28. Variants with CADD score ≥ 20 were considered functional. Both identified variants had CADD scores ≥ 20 and were present in a heterozygous state. A novel variant IGF-1:p.Ile91Leu (mature peptide residue number Ile43Leu) was found in two female centenarians, whereas the IGF-1:p.Ala118Thr (mature peptide residue number Ala70Thr) variant was found in two male centenarians as well as in three offspring and three control individuals. Remarkably, the carriers of these variants in our longevity cohorts remained free of diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, and demonstrated good cognitive function (Supplementary Table S1); indicating their role in healthy aging. The IGF-1:p.Ala118Thr was classified by ClinVar as a variant of unknown significance (VUS) that was previously noted in probands with growth delay due to IGF-1 deficiency. IGF-1 gene is conserved among mammals29. To ensure clarity, we will refer to the amino acid numbering of human IGF-1R (including the signal peptide) and propeptide IGF-1 to describe our subsequent structural and biochemical analyses. IGF-1 protein sequences of different mammals obtained from UniProt and ClustalW30 was employed for multiple sequence alignment (MSA) to assess the conservation of Ile91 and Ala118 residues. Both Ile91 and Ala118 are highly conserved (Supplementary Figure S1). The conservation of Ile91 has already been reported31. Thus, substitutions at these positions could potentially have detrimental effects on the protein’s structure and function. In our cohort, carriers of IGF-1:p.Ile91Leu variants had insignificantly lower maximal reported height compared to non-carriers, adjusted for sex, (158.7 ± 1.8 cm vs. 163.4 ± 9.0 cm, respectively, p = 0.36), while the maximal reported height was comparable between IGF-1:p.Ala118Thr carriers and non-carriers (166.1 ± 7.1 cm vs. 166.7 ± 9.9 cm, respectively, p = 0.84). The serum IGF-1 levels of IGF-1:p.Ile91Leu carriers were not measured. Interestingly, the carriers of IGF-1:p.Ala118Thr had significantly lower levels of IGF-1 compared to non-carriers (Fig. 1B).

(A) The structure of IGF-1 gene. Our longevity cohort carries two missense variants in exon 4. Brown, light cyan and blue colors represent the signal peptide (SP), E peptide and protein-coding regions, respectively. A118T variant is located at the boundary of Exon 4 and the N-terminal sequence of the E-peptides, which is a cleavage site for the release of mature IGF-1. (B) Association of IGF-1:p.Ala118Thr with serum IGF-1 levels. Results are plotted as mean ± SD. The statistical model was adjusted with baseline age and sex. **p < 0.01.

Impact of mutants on IGF-1–IGF-1R bound structure

In order to ascertain the role of missense variants in perturbing the IGF-1–IGF-1R architecture and the binding of IGF-1 to IGF-1R, we investigated the impact of IGF-1 gene variants on IGF-1R structure and function. IGF-1:p.Ile91Leu variant was located at the binding interface of IGF-1–IGF-1R (Figs. 2A-2C). IGF-1R is a dimeric protein, with chain A and chain B depicted in gray and light pink, respectively, in Fig. 2A. At the static structure level, neither isoleucine nor leucine established contacts with the adjacent residues of IGF-1R. Ile91Leu was tracked during MD simulations to observe its binding potential with neighboring residues of IGF-1R and IGF-1. In the wild-type runs, IGF-1 Ile91 formed a slightly more stable interaction with the critical binding pocket residue Phe731of IGF-1R when compared to mutant runs (Leu91). In contrast, Leu91 exhibited consistent interactions with Glu94 and Cys95 of IGF-1, unlike the wild-type Ile91 (Figs. 2B-2D). This suggested that Leu91 variant was more engaged in forming interactions with neighboring residues of IGF-1 and was less readily available for forming interaction with IGF-1R compared to wild-type Ile91 residue. IGF-1:p.Ala118Thr, on the other hand, was found at the C-terminal end of the IGF-1 molecule, a region that is not involved in IGF-1R binding. As expected, Ala118Thr did not establish contact with residues of IGF-1R (Figs. 2E and 2F).

Three-dimensional structure of human IGF-1R bound to IGF-1. The red-boxed regions in (A) are magnified in the successive images (B, C, E and F). The IGF-1R dimer is depicted with two chains, displayed in gray and light pink, while IGF-1 is illustrated with a blue cartoon. (A) Structure of IGF-1R bound with IGF-1; (B) Wild-type Ile91; (C) Mutant Leu91; (D) The percentage of simulation time during which Ile91Leu maintained contacts with neighboring residues of IGF-1R and IGF-1.E) Wild-type Ala118; (F) Mutant Thr118. Hydrogen bonds are represented with yellow dotted lines.

MD simulations of wild-type and mutant IGF-1–IGF-1R complexes

Given that the IGF-1.Ile91Leu variant was located at the binding interface of IGF-1 and IGF-1R, we conducted extended MD simulations to gain mechanistic insights into how this variant may affect the binding architecture of IGF-1 with IGF-1R. IGF-1:p.Ala118Thr was excluded from MD simulation because it was situated at the boundary of the mature IGF-1 molecule and was not demonstrated to be important for IGF-1R binding. MD simulations of wild-type and IGF-1.Ile91Leu (referred to as mutant IGF-1 here onwards) complexes of IGF-1–IGF-1R were performed in triplicates, each of 500 ns duration, to avoid bias in results often caused by a single simulation run. Runs of the wild-type and mutant simulations were extended to 500 ns to ensure that simulations remained stable and the interactions were faithfully retained for longer duration. The root mean square deviation (RMSD) results from the three runs per simulated system were averaged, and the mean evolution for each system, along with the standard deviations, are shown in Fig. 3. The individual contributions of the different runs for each system are provided in Supplementary Figure S2. The overall structural integrity of all simulations of wild-type and mutant complexes remained stable with a Cα RMSD from the initial structure that was less than 11 Å (Fig. 3A). Both wild-type and mutant complexes reached equilibrium after a few nanoseconds of simulation and remained stable throughout the course of simulations. IGF-1R is a dimeric macromolecule and is expected to produce slightly higher RMSD than other proteins that exist as monomers. Nevertheless, all the runs eventually reached convergence by the end of the simulations. Simulations of dimeric proteins as well as mutated proteins have shown similarly elevated RMSD values32,33. The impact of variant on the structural integrity of IGF-1 without IGF-1R was also evaluated. Both the wild type and mutant IGF-1 with and without IGF-1R retained structural stability throughout the simulation runs (Supplementary Fig. 4A and B). The secondary structure composition and compactness of the IGF-1R and IGF-1 protein structures, as represented by the radius of gyration, remained preserved throughout the simulations (Supplementary Table S2 and Table S3).

Root mean square deviation (RMSD) and root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) of protein Cα atoms with respect to the initial structure obtained from three independent runs. Results from three simulation runs of each system are plotted as mean ± SD. (A) RMSD of wild-type and mutant IGF-1–IGF-1R complexes; (B) RMSF of Cα atoms of IGF-1R protein in the wild-type and mutant IGF-1–IGF-1R complexes; (C) RMSF of Cα atoms of IGF-1 protein in the wild-type and mutant IGF-1–IGF-1R complexes. Loop and helical regions of each protomer of IGF-1R and IGF-1 binding regions that make contact with IGF-1R are identified with black bars.

Comparison of regional fluctuations in the wild-type and mutant IGF-1– IGF-1R complexes

To observe and compare backbone stability and fluctuations of the two complexes, root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) of backbone Cα atoms were measured and plotted (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Figure S3A and B). IGF-1’s primary binding site is composed of L1 residues Arg40, Glu83, Phe88 and Arg99, CR domain residues Glu294, Glu333 and Ly336, and α-CT residues 727–741 of IGF-1R. The CR domain (residues 276–328), and FnIII domains (residues 739–779 and 836–895) comprised of loop and helical regions of each protomer fluctuated more compared to the rest of the protein structure, while residues 329–734 of both protomers exhibited limited fluctuations (Fig. 3B). However, the mutant exhibited more fluctuation in these regions when compared to wild-type (Fig. 3B). Importantly, regions around the binding site residues also fluctuated more in the mutant (Supplementary Figure S5).

The fluctuations of IGF-1, both its bound and unbound states with IGF-1R dimer structures, were evaluated by assessing the RMSF of backbone Cα atoms of IGF-1. Overall, the IGF-1 backbone exhibited higher fluctuations in the mutant complex system, when compared to wild-type systems (Fig. 3C, Supplementary Fig. 4C and D). Of all the IGF-1 residues, the loop regions spanning residues 54–57 and 76–79 were identified as very flexible, displaying elevated fluctuations across all systems (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, residues at the interfacial region of IGF-1 (81–99 and 104–109) showed less fluctuation in wild-type as compared to mutant (Fig. 3C). Additionally, IGF-1 residues Phe73, Pro87, Ile91, Val92, Asp93, Glu94 and Cys96, which are known to interact with IGF-1R, exhibited reduced fluctuation in wild-type (Supplementary Figure S6). The more fluctuations observed in mutant IGF-1 suggested that IGF-1:p.Ile91Leu likely altered the binding of IGF-1 to IGF-1R compared to the wild-type.

Interfacial residue contact duration differs substantially between wild-type IGF-1 – IGF-1R and mutant IGF-1 – IGF-1R complexes

During the simulations, several intermolecular contacts such as hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds, salt bridges, π–π and cation–π interactions were observed to form, break, and reform. There were some interactions that lasted longer than others. The residues of wild-type and mutant IGF-1 that exhibited consistent interactions with IGF-1R are shown in Fig. 4. The contact duration of intermolecular interactions between wild-type or mutant IGF-1 and IGF-1R interfaces, as well as the dynamics of each interaction throughout the duration of the simulation trajectories, are demonstrated in Supplementary Table S4.

(A) Enlarged view of the binding interface of IGF-1R (grey and pink) bound to IGF-1 (blue); (B) The percentage of simulation time during which intermolecular contacts were retained between IGF-1R and IGF-1 interacting residues. Results from three simulation runs of each system are plotted as mean ± SEM.

In the wild-type simulation runs, IGF-1 residues Pro87 and Val92 formed consistent interactions with α-CT Asn728, while Lys75 and Tyr79 formed weak intermittent interactions with Glu289 and Phe296 residues of IGF-1R. Other essential α-CT residues, Val732 and Arg734, also formed more sustained interaction with wild-type IGF-1 Tyr108 and Glu94, respectively, compared to mutant IGF-1 (Fig. 4B). Additionally, IGF-1 residues Pro87 and Gln88 have been shown previously to form interactions with IGF-1R Phe725 and Ser72920. We, however, observed a stable interaction between Pro87 and Asn728 in wild-type only. Moreover, our findings differed from previous reports in that we did not observe IGF-1 Gln88 binding with Phe725 and Ser729 of the IGF-1R. Instead, Gln88 on IGF-1 consistently interacted with IGF-1R Thr340 in the wild-type, but not in the mutant. In the wild-type, IGF-1 Phe73 side chains underwent a rotameric rearrangement and were found buried in a hydrophobic pockets formed by IGF-1R residues Arg40, Leu63 and Phe731. Such a rearrangement helped IGF-1 Phe73 to form consistent interactions with IGF-1R Arg40. Interestingly, this interaction was observed to be weaker in the mutant compared to the wild-type (Fig. 4B). Notably, Phe71, Tyr72 and Phe73 residues of IGF-1 have been shown to be important for IGF-1R binding34 and the rotameric rearrangement of Phe71 and Phe73 upon binding of IGF-1 to IGF-1R has previously been reported20. Furthermore, Asp93 of IGF-1 has been shown to exist near α-CT Asn724 as indicated in a cryo-EM structural study11. However, we have not observed this interaction in any of our simulation runs. Instead, IGF-1 Asp93 formed the more stable salt bridge and hydrogen bond with IGF-1R Lys336 and Arg518 in the wild-type compared to the mutant. Although, IGF-1 Val92 has been reported to make contacts with α-CT Asn724 and Asn728, our simulations showed that Val92 formed a stable hydrogen bond with Asn728 in the wild-type IGF-1 as compared to mutant (Fig. 4). A mutagenesis study has illustrated the importance of IGF-1 Val92 in binding of IGF-1 to IGF-1R35. Additionally, IGF-1 Glu94 exhibited a stable interaction with IGF-1R residue Arg734 in the wild-type IGF-1 compared to mutant. A mutagenesis study has shown the essential role of IGF-1R Arg734 in the binding of IGF-1 with IGF-1R36.

IGF-1 C-terminal residues are known to be critical in maintaining optimal binding to IGF-1R. A replacement of C-terminal region with additional glycine residues have resulted in 30-fold decrease in IGF-1 affinity for IGF-1R37. Here, IGF-1 C-terminal residues Ser99 and Tyr108 formed more consistent interactions with Asn747 and Val732 of IGF-1R in the wild-type compared to the mutant (Fig. 4B).

A small secondary binding site (1b) for IGF-1 within the active IGF-1R dimer has recently been reported11. It is mainly composed of loop regions of the FnIII-1′ domain. Residues 513–518 and Lys560 of FnIII-1′ form this secondary binding subsite. The IGF-1R residue Tyr517 formed interaction with IGF-1 Cys96 and Arg518 with IGF-1 Asp93 and Phe97. These interactions were noted to be more stable in wild-type runs (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Table S4). Interestingly, Lys560 formed a much more stable salt bridge with IGF-1 residue Glu57 in the mutant runs compared to wild-type (Fig. 4B). A previous mutagenesis study reported that residues in a subsite (513–518) of IGF-1R, particularly Tyr517 and Arg518, were important for IGF-1 optimal binding, whereas residues around IGF-1R Lys560 had no effect on IGF-1 dependent IGF-1R activation11. However, the precise role of Lys560 has not been established yet.

Interestingly, mutant variant IGF-1:p.Ile91Leu is located at the binding interface of IGF-1. Structural studies have indicated that Ile91 residue makes contact with IGF-1R residues His727, Asn728 and Phe731. The wild-type IGF-1 protein formed relatively more sustained interactions with IGF-1R Phe731, compared to mutant IGF-1 (Fig. 4B). It is perceivable that this interaction helped nearby residues of IGF-1, particularly Val92, Asp93 and Glu94 to form stable interactions with IGF-1R interfacial residues (Fig. 4). Since we simulated the entire extracellular domain of IGF-1R complexed with IGF-1, this may have affected our analysis. To observe the impact of inherent IGF-1R flexibility on the IGF-1 binding, we simulated only the interacting residues of IGF-1R with IGF-1 for 500 ns in triplicates. Overall, IGF-1 maintained its binding mode and interactions with the key residues of IGF-1R throughout the simulation runs. This suggested that receptor flexibility had a minimal impact, particularly on IGF-1 binding (Supplementary Figure S9).

Wild-type IGF-1 bound more stably to IGF-1R

An analysis of intermolecular interactions demonstrated that IGF-1R complexes formed a greater number of interactions with the wild-type IGF-1 compared to the mutant IGF-1 (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table S4). This finding suggested that compared to the mutant IGF-1, the wild-type IGF-1 may have greater affinity for the IGF-1R. To examine the energetic contributions, the free energy of binding (ΔGbind) was compared between mutant and wild-type IGF-1 bound to IGF-1R, calculated using the molecular mechanics-generalized Born surface area (MM-GBSA) approach based on frames extracted every 2.5 ns from all MD simulations. All wild-type simulations demonstrated substantially higher ΔGbind values than the mutant runs (Table 1). A higher free energy of binding indicated a stronger binding affinity. Hydrophobic contributions to ΔGbind were also lower for mutant simulations compared to wild-type. The complete count of intermolecular hydrogen bonds between the two complexes was also tracked during the simulations. The wild-type complexes exhibited a greater number of hydrogen bonds (mean ± SD for three simulations: 23.88 ± 3.50, 25.85 ± 3.65, 21.88 ± 4.02) compared to the mutant (20.65 ± 4.01, 24.06 ± 4.46, 18.64 ± 3.28) in all simulation runs (Supplementary Figure S7). This would also be expected to enhance the binding affinity between wild-type IGF-1 and IGF-1R. Given the approximations and assumptions inherent in MM-GBSA calculations, ΔGbind values obtained here should be interpreted qualitatively rather than quantitatively.

Mutant alters IGF-1R inter-protomer interactions

We also investigated the impact of mutant IGF-1 on dynamics of IGF-1R inter-protomer interactions. The inter-protomer interactions are shown in Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table S5. Specific residues within L1–FnIII-2′ have been demonstrated to be crucial for IGF-1R dimerization20. In both wild-type and mutant simulations, Glu177 and Glu188 residues of L1 formed similar interactions with Arg671 and Lys665 of FnIII-2′, respectively (Fig. 5A and Supplementary Figure S8). A network of inter-protomer interactions showed similar binding stability throughout the simulation runs of IGF-1R bound with the wild-type and the mutant IGF-1. For instance, in all simulation runs, chain A residues Asp553, Lys720, Asn724, and Arg755 showed similar interactions stability with chain B residues Arg365, Tyr517, Arg518, and Glu563, respectively (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table S5). However, A:Lys389 - B:Glu590, A:Arg391- B:Glu590, A:Arg480 - B:Asp424, A:Asp616 - B:Arg739, A:Lys688 - B:Glu715, A:Glu690 - B:Arg753, A:Glu706 - B:Asp542 and A:Lys709 - B:Asp553 inter-protomer interactions varied substantially between wild-type and mutant runs (Fig. 5). Overall, compared to the mutant, the wild-type simulations resulted in the formation of slightly more stable interactions between two chains of the IGF-1R. This indicated that mutant IGF-1 caused a subtle conformational change in the IGF-1R. This subtle rearrangement of IGF-1R protomers likely changed the configuration of IGF-1 binding pocket and weakened the binding of the mutant IGF-1 to IGF-1R.

Binding interface of chain A and Chain B of IGF-1R. (A) Enlarged binding pose showing the residues that interact in the interface; (B) The percentage of simulation time during which intermolecular contacts were retained between chain A and chain B interacting residues of IGF-1R dimer. Results from three simulation runs of each system are plotted as mean ± SEM. For clarity, the IGF-1R domains are colored differently. The L1, L2, FnIII-1, are FnIII-2 domains of both chains are shown in green, yellow, blue, and grey color, respectively. Hydrogen bonds and salt bridges are represented by yellow and pink dotted lines, respectively. Interacting residues of chain A and chain B are shown in grey and orange sticks, respectively.

Discussion

This study provided insights into two IGF-1 gene coding variants discovered in individuals with exceptional longevity. We described the structural and functional impact of IGF-1:p.Ile91Leu by characterizing the stability of interactions that define the IGF-1R–IGF-1 interface. Utilization of extended MD simulations demonstrated that compared to the wild-type IGF-1, the IGF-1:p.Ile91Leu variant resulted in weaker interactions between IGF-1 and its receptor, likely attenuating IGF-1R activation. Additionally, we identified the IGF-1:p.Ala118Thr variant, which was significantly associated with lower levels of IGF-1 in our longevity cohort. The latter variant may result in lower circulating IGF-1 level due to its location near an IGF-1 gene E-peptide region, which is typically removed during the post-translational processing of the IGF-1 precursor protein. Overall, our results suggest that compared to wild-type IGF-1, the activation of IGF-1R and subsequent downstream signaling mediated by mutant IGF-1s would be expected to produce attenuated effects. Given the previously identified role of reduced insulin/IGF-1 signaling in models of longevity, our findings provide additional evidence for the potential role of these gene variants and reduced IGF-1 signaling in human longevity. However, further experimental studies are required to confirm their molecular mechanisms.

Previous longevity-focused GWAS studies have not identified genetic variants in the IGF-1 gene, despite the conserved roles of insulin/IGF-1 system in longevity. This is likely due to the inherent limitations of GWAS, which primarily investigate common genetic variants with a minor allele frequency (MAF) > 5% in the general population, whereas exceptional longevity is a rare phenotype observed in < 1% of individuals. As a result, these studies were underpowered to detect rare genetic variants that may contribute to exceptional longevity38. In this study, we attempted to find all coding variants in the IGF-1 gene in our longevity cohort. Interestingly, we found only two rare coding variants (MAF ≤ 0.01), supporting the idea that IGF-1 is highly conserved across species. Moreover, rare variants association studies to date have generally been underpowered to detect their effects on phenotype39. One approach to overcome this challenge is to perform GWAS in very large longevity cohorts, which are currently unavailable. Alternatively, one can focus on rare variants that may be more represented among individuals with longevity. Studies have demonstrated the functional impacts of longevity specific rare coding variants at the single gene level, in genes such as IGF-1R5, SIRT640, APOC341, as well as others. For instance, a previous study identified the IGF-1R.p.Ala67Thr variant in only two centenarians5. This variant was shown to cause decreased IGF-1R activation, possibly by weakening its binding to IGF-1. Similarly, a recent study found two rare coding variants (rs183444295 and rs201141490) in SIRT6 among centenarians40. Interestingly, the SIRT6 variants were found to strongly suppress LINE1 retrotransposons, boost DNA double-strand break repair, and more effectively eradicate cancer cells compared to the wild-type. These studies indicate the importance of identifying and establishing the molecular mechanisms of longevity associated rare coding variants. Understanding the mechanisms of rare longevity-associated variants found in individuals with exceptional longevity is of paramount importance in advancing our knowledge of how genes that carry these variants regulate downstream signaling of pro-longevity pathways and could serve as promising gerotherapeutic drug targets.

The IGF-1 gene significantly impacts growth and development. A genetic variant located in the promotor region of the IGF-1 gene has been shown to be associated with small size in dogs42. In mice, a synonymous mutation in IGF-1 significantly affected both the expression and biological functions of IGF-143. Short stature and reduced binding affinity of IGF-1 to IGF-1R have also been reported in families with coding variants in the IGF-1 gene6,9. However, to the best of our knowledge, IGF-1 coding variants have not been previously identified in humans with longevity. We identified two likely functional coding variants, Ile91Leu and Ala118Thr, in IGF-1 in a heterozygous state that were not associated with adult maximal height, likely because they result in partial reduction of IGF-1 function. Similarly, centenarian specific variants that induced only partial loss of function have been identified in IGF-1R5. Interestingly, we found the IGF-1:p.Ile91Leu variant in two centenarians, located at the binding interface of IGF-1R–IGF-1. Although, from a physiochemical perspective the substitution of isoleucine to leucine is not expected to be functionally significant, this change has previously been shown to alter protein–protein interactions and enzyme activity in other genes44,45,46. Potential functional effects of missense substitutions are illustrated by a prior study, in which the assessment of various IGF-1 analogs revealed that [His95]-IGF-1 and [Gln95]-IGF-1 exhibited significantly reduced binding affinities for IGF-1R that resulted in diminished activation of IGF-1R compared to wild-type47. A similar pattern was also noted in another study wherein IGF-1 analogs that exhibited weaker binding affinity demonstrated reduced activation of IGF-1R10. This implies that a higher binding affinity of IGF-1 does lead to a more robust activation of IGF-1R. Moreover, a specific conformational change at the cytoplasmic end of IGF-1R upon IGF-1 binding is crucial to generate optimal downstream signaling. In this study, IGF-1:p.Ile91Leu was observed to bind less stably with IGF-1R at the extracellular binding site compared to wild-type. Consistent with earlier studies, it is likely that this variant will induce a change in the conformation of IGF-1R at the cytoplasmic end, potentially reducing its activation. However, further experimental studies are required to confirm its molecular mechanism. Diminished IGF-1R signaling has consistently been shown to extend lifespan in multiple model organisms1,20,48, including humans49, where individuals with exceptional longevity and IGF-1R coding variants exhibited reduced activity of IGF-1R and IGF-1 induced AKT phosphorylation5.

The epidemiological studies that focused on assessing the association of circulating IGF-1 levels with life-span and health-span have shown mixed results49. Studies in longevity cohorts have reported positive associations between higher IGF-1 with all-cause mortality and age-related diseases50,51,52. Conversely, other studies, mostly involving younger populations, have indicated the reverse: elevated IGF-1 levels were linked to a decreased risk of disease and mortality53,54. However, a recent large-scale study involving nearly 450,000 UK biobank participants showed that older adults with higher IGF-1 levels had greater risk of mortality and age-related diseases, indicating that lower IGF-1 levels were beneficial for their survival55. In our longevity cohort, carriers of IGF-1:p.Ala118Thr had significantly lower levels of IGF-1, compared to non-carriers (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, a synonymous variant in exon 4 of the IGF-1 gene has previously been shown to reduce the expression, secretion, stability, and half-life of IGF-1 in mice. In our study, IGF-1:p.Ala118Thr was located at the intersection of Exon 4 and the N-terminal sequence of the E-peptides (pro-peptides) of IGF-1 (Fig. 1A). Moreover, this variant falls within a unique pentabasic motif (Lys113-Arg125) where post-translational cleavage of pro-IGF-1 polypeptides generally occurs. This cleavage has been shown to regulate the expression, stability, release and bioavailability of IGF-122,56,57. Thus, this variant may potentially modify the binding motif involved in the cleavage of the carboxyl-terminal E domain from the pro-IGF-1, resulting in lower IGF-1 level. Lower IGF-1 levels may in turn lead to reduced IGF-1R signaling6,55, which may be beneficial for longevity. However, the IGF-1:p.Ala118Thr variant dependent effect on the expression, stability, release, and bioavailability of IGF-1 molecule is also possible.

In summary, this study identified two rare functional coding variants IGF-1:p.Ile91Leu and IGF-1:p.Ala118Thr which likely impact the IGF-1 induced downstream signaling of IGF-1R. Our findings suggest that IGF-1:p.Ile91Leu and IGF-1:p.Ala118Thr variants attenuate IGF-1R activity, potentially via reduced binding of IGF-1 to IGF-1R and by diminishing the circulatory levels of IGF-1, respectively. These results provide evidence that the rare IGF-1 variants identified in cohorts with exceptional longevity may contribute to extended lifespan via attenuation of IGF-1 signaling.

Methods

Recruitment of study participants

The participants in this study were Ashkenazi Jews from two well-characterized longevity cohorts, the Longevity Genes Project (LGP) and the LonGenity study, which have been recruited and characterized at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. The longevity cohorts consisted of individuals with exceptional longevity (centenarians) age ≥ 95 years, offspring of individuals with exceptional longevity (offspring), defined as having at least one parent who lived to 95 years or older, and individuals without parental history of exceptional longevity (controls), defined as not having a parent that survived beyond 95 years of age. Both LGP and LonGenity studies were approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of Albert Einstein College of Medicine58,59,60 (approval numbers 1998–125 and 2007–272, respectively) and were performed in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. All experimental protocols were approved by IRB of Albert Einstein College of Medicine (approval numbers 1998–125 and 2007–272, respectively).

Whole exome sequencing and functional variant identification

Whole exome sequencing (WES) of 2,332 subjects was carried out at the Regeneron Genetics Center (RGC). The pipeline adopted for sample preparation and WES has been previously described61. GRCh38 human genome assembly was used for variant calling. Individuals with low sequencing coverage (less than 80% of bases with coverage ≥ 20x), call rate < 0.9, and discordant sex were excluded. SNPs were removed if they had the read depth (DP) < 7 (DP < 10 for insertions/deletions (INDEL)), alternative Allele Balance less than a cutoff (≤ 15% for SNP, ≤ 20% for INDEL), and Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium deviated from an χ2-test P < 1 × 10–6. Variants with missing rates < 0.01 in the study cohort were used for further analysis. In this study, we focused on rare variants with minor allele frequencies < 1% in our cohort. The functional nature of the variants was predicted using combined annotation dependent depletion (CADD) score28. It is a widely used method to predict the variant’s deleteriousness. Variants with CADD score ≥ 20 were considered functional. Overall, 2,108 subjects and 2 variants in the IGF-1 gene passed all the thresholds.

Protein modeling and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations

The three dimensional (3D) dimeric crystal structure of human IGF-1R was retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 6JK8). The protein structure was visualized and prepared for docking by using Schrödinger Maestro 2023–2 (Schrödinger, LLC, NY). The structure was first pre-processed using the Protein Preparation Wizard (Schrödinger, LLC, NY). The protein preparation stage included proper assignment of bond order, adjustment of ionization states, orientation of disorientated groups, creation of disulphide bonds, removal of unwanted water molecules, metal and co-factors, capping of the termini, assignment of partial charges, and addition of missing atoms and side chains using default protein preparation wizard tasks. Loops refinement and further structural verification was carried out using the protein refinement module of Schrödinger Prime using default settings. The missing hydrogen atoms were added, and standard protonation state at pH7 was used. The human wild-type and the mutant IGF-1 was docked in the binding site 1 of the IGF-1R using protein–protein docking suite (BioLuminate, Schrödinger, LLC, NY). IGF-1 protein was used as ligand and was docked starting from multiple random conformations. Ten representative docked protein–protein complexes were chosen following the clustering of the generated conformers. The binding poses of IGF-1 with IGF-1R were compared with the already reported structures. The best binding pose of wild-type and mutant IGF-1 with IGF-1R based on free energy of binding, was subjected to MD simulations. Mutant IGF-1:p.Ile91Leu was generated by employing computational point mutations using the residue mutation panel of Schrodinger Maestro. Structures of wild-type and mutant IGF-1, either bound to full length IGF-1R, and unbound to IGF-1R or bound to only interacting residues of IGF-1R were placed in large orthorhombic boxes of size 160 Å × 160 Å × 230 Å and 60 Å × 60 Å × 60 Å, respectively. All the prepared systems were solvated with single point charge (SPC) water molecules using the Desmond System Builder (Schrödinger, LLC, NY). An appropriate number of counterions were added to neutralize the simulation systems and salt concentration of 0.15 M NaCl was maintained. All-atom MD simulations were carried out using Desmond62. All calculations were performed using the OPLS forcefield. Prior to the start of the production run, all prepared simulation systems were subjected to Desmond’s default eight stage relaxation protocol. Both the wild-type and mutant IGF-1 bound to IGF-1R were simulated for 500 ns in triplicates using different sets of initial seed velocities. To maintain the pressure at 1 atm and temperature at 300 K during the simulation runs, the isotropic Martyna–Tobias–Klein barostat63 and the Nose–Hoover thermostat64 were used, respectively. A 9.0 Å cutoff was set for short-range interactions and the smooth particle mesh Ewald method (PME)65 was used to measure the long-range coulombic interactions. A time-reversible reference system propagator algorithm (RESPA) integrator was used with an inner time step of 2.0 fs and an outer time step 6.0 fs. Molecular Mechanics-Generalized Born Surface Area (MM-GBSA) method was employed to determine the free energy of binding of wild-type and mutant IGF-1 protein to IGF-1R using frames obtained from MD simulation trajectories. Frames were retrieved every 2.5 ns from each of the simulation runs and MM-GBSA based binding free energy was computed using Schrödinger Prime employing the VSGB 2.0 solvation model66. Simulation data was analyzed using packaged and in-house scripts. Graphs were plotted using R version 3.6.3 (https://www.r-project.org) and images of structures were generated using Schrödinger Maestro 2023–2 (Schrödinger, LLC, NY).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Holzenberger, M. et al. IGF-1 receptor regulates lifespan and resistance to oxidative stress in mice. Nature 421, 182–187 (2003).

Bartke, A. Minireview: Role of the growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor system in mammalian aging. Endocrinology 146, 3718–3723 (2005).

Coschigano, K. T. et al. Deletion, but not antagonism, of the mouse growth hormone receptor results in severely decreased body weights, insulin, and insulin-like growth factor I levels and increased life span. Endocrinology 144, 3799–3810 (2003).

Russell, S. J. & Kahn, C. R. Endocrine regulation of ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 681–691 (2007).

Suh, Y. et al. Functionally significant insulin-like growth factor I receptor mutations in centenarians. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 3438–3442 (2008).

Giacomozzi, C. et al. Novel insulin-like growth factor 1 gene mutation: Broadening of the phenotype and implications for insulin resistance. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 108, 1355–1369 (2023).

Netchine, I. et al. Partial primary deficiency of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I activity associated with IGF1 mutation demonstrates its critical role in growth and brain development. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 94, 3913–3921 (2009).

Bonapace, G., Concolino, D., Formicola, S. & Strisciuglio, P. A novel mutation in a patient with insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) deficiency. J. Med. Genet. 40, 913–917 (2003).

Walenkamp, M. J. et al. Homozygous and heterozygous expression of a novel insulin-like growth factor-I mutation. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 90, 2855–2864 (2005).

Machácková, K. et al. Insulin-like growth factor 1 analogs clicked in the C domain: Chemical synthesis and biological activities. J. Med. Chem. 60, 10105–10117 (2017).

Li, J., Choi, E., Yu, H. T. & Bai, X. C. Structural basis of the activation of type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor. Nat. Commun. 10, 1 (2019).

Siddle, K. Molecular basis of signaling specificity of insulin and IGF receptors: Neglected corners and recent advances. Front. Endocrinol. 3, 34 (2012).

Choi, E. & Bai, X. C. The activation mechanism of the insulin receptor: A structural perspective. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 92, 247–272 (2023).

Forbes, B. E. The three-dimensional structure of insulin and its receptor. Vitam. Horm. 123, 151–185 (2023).

Smith, B. J. et al. Structural resolution of a tandem hormone-binding element in the insulin receptor and its implications for design of peptide agonists. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 6771–6776 (2010).

Whittaker, J. et al. Alanine scanning mutagenesis of a type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor ligand binding site. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 43980–43986 (2001).

Whittaker, L., Hao, C., Fu, W. & Whittaker, J. High-affinity insulin binding: Insulin interacts with two receptor ligand binding sites. Biochemistry 47, 12900–12909 (2008).

Mynarcik, D. C., Yu, G. Q. & Whittaker, J. Alanine-scanning mutagenesis of a C-terminal ligand binding domain of the insulin receptor alpha subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 2439–2442 (1996).

Kavran, J. M. et al. How IGF-1 Activates its Receptor. Elife 3, 3772 (2014).

Xu, Y. B. et al. How ligand binds to the type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor. Nat. Commun. 9, 1 (2018).

Zhang, X. et al. Visualization of ligand-bound ectodomain assembly in the full-length human IGF-1 receptor by Cryo-EM single-particle analysis. Structure 28, 555-561.e4 (2020).

Philippou, A., Maridaki, M., Pneumaticos, S. & Koutsilieris, M. The complexity of the IGF1 gene splicing, posttranslational modification and bioactivity. Mol. Med. 20, 202–214 (2014).

Wang, S. Y. et al. A synonymous mutation in IGF-1 impacts the transcription and translation process of gene expression. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 26, 1446–1465 (2021).

Song, X. T. et al. Molecular cloning, expression, and functional features of IGF1 splice variants in sheep. Endocr. Connect. 10, 980–994 (2021).

Freitas, E. D. S. et al. Lower muscle protein synthesis in humans with obesity concurrent with lower expression of muscle IGF1 splice variants. Obesity 31, 2689–2698 (2023).

De Vivo, M., Masetti, M., Bottegoni, G. & Cavalli, A. Role of Molecular dynamics and related methods in drug discovery. J. Med. Chem. 59, 4035–4061 (2016).

Wingler, L. M., McMahon, C., Staus, D. P., Lefkowitz, R. J. & Kruse, A. C. Distinctive activation mechanism for angiotensin receptor revealed by a synthetic nanobody. Cell 176, 479 (2019).

Kircher, M. et al. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat. Genet. 46, 310–315 (2014).

Rotwein, P. Diversification of the insulin-like growth factor 1 gene in mammals. PLoS ONE 12, e0189642 (2017).

Thompson, J. D., Higgins, D. G. & Gibson, T. J. Clustal-W—Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 4673–4680 (1994).

Irwin, D. M. Evolution of the mammalian insulin (Ins) gene; Changes in proteolytic processing. Peptides 135, 170435 (2021).

Savva, L. & Platts, J. A. Computational investigation of copper-mediated conformational changes in alpha-synuclein dimer. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 26, 2926–2935 (2024).

Shinwari, K. et al. In-silico assessment of high-risk non-synonymous SNPs in ADAMTS3 gene associated with Hennekam syndrome and their impact on protein stability and function. BMC Bioinform. 24, 1 (2023).

Cascieri, M. A. et al. Mutants of human insulin-like growth factor-I with reduced affinity for the type-1 insulin-like growth-factor receptor. Biochemistry 27, 3229–3233 (1988).

Denley, A. et al. Structural and functional characteristics of the Val44Met insulin-like growth factor I missense mutation: Correlation with effects on growth and development. Mol. Endocrinol. 19, 711–721 (2005).

Kertisová, A. et al. Insulin receptor Arg717 and IGF-1 receptor Arg704 play a key role in ligand binding and in receptor activation. Open Biol. 13, 230142 (2023).

Bayne, M. L. et al. The C-region of human insulin-like growth-factor (Igf)-I is required for high-affinity binding to the type-1 Igf receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 11004–11008 (1989).

Milman, S. & Barzilai, N. Discovering biological mechanisms of exceptional human health span and life span. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 13, a041204 (2023).

Barton, A. R., Sherman, M. A., Mukamel, R. E. & Loh, P. R. Whole-exome imputation within UK Biobank powers rare coding variant association and fine-mapping analyses. Nat. Genet. 53, 1260 (2021).

Simon, M. et al. A rare human centenarian variant of SIRT6 enhances genome stability and interaction with Lamin A. EMBO J. 42, e113326 (2023).

Atzmon, G. et al. Lipoprotein genotype and conserved pathway for exceptional longevity in humans. PLoS Biol. 4, e113 (2006).

Sutter, N. B. A single allele is a major determinant of small size in dogs. Science 316, 1284–1284 (2007).

Wang, S. Y. et al. A synonymous mutation in impacts the transcription and translation process of gene expression. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 26, 1446–1465 (2021).

Wu, E. et al. A conservative isoleucine to leucine mutation causes major rearrangements and cold-sensitivity in KlenTaq1 DNA polymerase. FASEB J. 28, 1 (2014).

Sitbon, M. et al. Substitution of leucine for isoleucine in a sequence highly conserved among retroviral envelope surface glycoproteins attenuates the lytic effect of the friend murine leukemia-virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88, 5932–5936 (1991).

He, L. et al. Single methyl groups can act as toggle switches to specify transmembrane Protein-protein interactions. Elife 6, 27701 (2017).

Machácková, K. et al. Converting insulin-like growth factors 1 and 2 into high-affinity ligands for insulin receptor isoform a by the introduction of an evolutionarily divergent mutation. Biochemistry 57, 2373–2382 (2018).

Kenyon, C., Chang, J., Gensch, E., Rudner, A. & Tabtiang, R. A C-elegans mutant that lives twice as long as wild-type. Nature 366, 461–464 (1993).

Milman, S., Huffman, D. M. & Barzilai, N. The somatotropic axis in human aging: Framework for the current state of knowledge and future research. Cell Metab. 23, 980–989 (2016).

Milman, S. et al. Low insulin-like growth factor-1 level predicts survival in humans with exceptional longevity. Aging Cell 13, 769–771 (2014).

van der Spoel, E. et al. Association analysis of insulin-like growth factor-1 axis parameters with survival and functional status in nonagenarians of the Leiden Longevity Study. Aging 7, 956–963 (2015).

Zhang, W. B. et al. Insulin-like growth factor-1 and igf binding proteins predict all-cause mortality and morbidity in older adults. Cells 9, 1368 (2020).

Bourron, O. et al. Impact of age-adjusted insulin-like growth factor 1 on major cardiovascular events after acute myocardial infarction: Results from the fast-MI registry. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 100, 1879–1886 (2015).

Friedrich, N. et al. Mortality and serum insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I and IGF binding protein 3 concentrations. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 94, 1732–1739 (2009).

Zhang, W. B., Ye, K., Barzilai, N. & Milman, S. The antagonistic pleiotropy of insulin-like growth factor 1. Aging Cell 20, e13443 (2021).

Hede, M. S. et al. E-peptides control bioavailability of IGF-1. PLoS ONE 7, e51152 (2012).

Annibalini, G. et al. The intrinsically disordered E-domains regulate the IGF-1 prohormones stability, subcellular localisation and secretion. Sci. Rep. 8, 8919 (2018).

Barzilai, N. et al. Unique lipoprotein phenotype and genotype associated with exceptional longevity. JAMA 290, 2030–2040 (2003).

Ismail, K. et al. Compression of morbidity is observed across cohorts with exceptional longevity. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 64, 1583–1591 (2016).

Gubbi, S. et al. Effect of exceptional parental longevity and lifestyle factors on prevalence of cardiovascular disease in offspring. Am. J. Cardiol. 120, 2170–2175 (2017).

Lin, J. R. et al. Rare genetic coding variants associated with human longevity and protection against age-related diseases. Nat. Aging 1, 783–794 (2021).

Bowers, K.J. et al. Scalable algorithms for molecular dynamics simulations on commodity clusters. In Proceedings of the 2006 ACM/IEEE Conference on Supercomputing 84-es (2006).

Martyna, G. J., Tobias, D. J. & Klein, M. L. Constant pressure molecular dynamics algorithms. J. Chem. Phys. 101, 4177–4189 (1994).

Martyna, G. J., Klein, M. L. & Tuckerman, M. Nosé-Hoover chains: The canonical ensemble via continuous dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 97, 2635–2643 (1992).

Essmann, U. et al. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 103, 8577–8593 (1995).

Li, J. et al. The VSGB 2.0 model: A next generation energy model for high resolution protein structure modeling. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 79, 2794–2812 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by R01AG061155 to SM and the American Federation for Aging Research/Glenn Foundation for Medical Research Postdoctoral Fellow grant to AA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AA and SM conceived the idea. SM, NR, TG and SA enrolled the study participants and performed clinical examinations. AA performed the experiments. AA, SM, ZZ, EG, and NB performed the analysis. AA and SM wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ali, A., Zhang, Z.D., Gao, T. et al. Identification of functional rare coding variants in IGF-1 gene in humans with exceptional longevity. Sci Rep 15, 10199 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94094-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94094-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

ARMH4 accelerates aging by maintaining a positive-feedback growth signaling circuit

Nature Communications (2025)