Abstract

In renal cell carcinoma (RCC), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP) 3 expression is lost, suggesting that the TIMP3 gene may function as a tumor suppressor gene. Cadmium (Cd) and arsenic (As) exposure may affect the expression of TIMP3. Here we investigate the association of clear cell RCC with TIMP3 polymorphisms, and explore whether TIMP3 polymorphisms modify the relationship between blood Cd or total urinary As levels and clear cell RCC respectively. We recruited 281 clear cell RCC patients and 689 sex- and age-matched controls. The clear cell RCC was diagnosed by pathological evaluation after image-guided biopsy or surgical resection of the renal tumor. Concentrations of blood Cd and lead, and also total urinary As, were measured. We determined TIMP3 polymorphisms using the Agena Bioscience MassARRAY system. Odds ratio (OR) of clear cell RCC was significantly inversely correlated with TIMP3 rs9609643 GA/AA genotype, with OR = 0.63 (95% confidence interval, CI, 0.44–0.91). For TIMP3 rs715572 AA compared to the GG/GA genotype, the OR of clear cell RCC was 1.60 with 95% CI of 1.01–2.56. Individuals with high blood Cd concentrations and the TIMP3 rs9609643 GG genotype exhibited a higher OR of clear cell RCC than reference groups (OR = 4.48, 95% CI 2.09–9.60). This study presents a novel finding that the GA/AA genotype of TIMP3 rs9609643 significantly decreased the clear cell RCC risk, and AA genotype of TIMP3 rs715572 significantly increased the clear cell RCC risk. Furthermore, this study first identified that the TIMP3 rs9609643 risk genotypes appear to interact with high blood Cd levels to increase the OR of clear cell RCC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) originates from renal tubular epithelial cells—it is the most prevalent form of kidney cancer. Clear cell histology accounts for approximately 70–80% of RCC cases, and other histological types include papillary and chromophobe cells1. In 2020, there were an estimated 431,288 new renal cancer cases worldwide, with epidemiological data showing that RCC accounts for the majority (90%) histologically2. Globally, RCC represents around 2% of cancer incidence and mortality rates, with future increases projected2. The age-standardized incidence rate of RCC rose from 3.39/106 in 2002 to 5.09/106 in 2012 in Taiwan3. Potential risk factors for RCC include comorbidities like urolithiasis, hypertension, and diabetes, lifestyle factors such as smoking and obesity, as well as environmental factors4. Environmental factors lead (Pb) and cadmium (Cd) in the blood, were found to be significantly higher in RCC cases than controls5. Our previous study also revealed an association of high total urinary arsenic (As) and high blood Cd levels with the RCC odds ratio (OR)6. However, determining the molecular mechanisms that comprise the relationship between RCC and these metals require further investigation.

Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP) 3 is a member of the TIMP family and serves as an endogenous regulator of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs)—it is vital to maintaining the surrounding extracellular matrix (ECM). Its broad inhibitory spectrum against MMP activity makes TIMP3 a key player in ECM regulation7. Studies examining methylation-associated silencing of TIMP3 have suggested its role as a tumor suppressor in various cancers. Loss of TIMP3 expression has been linked to the development of tumorigenesis8,9. Notably, nearly all cases of clear cell RCC exhibit loss of TIMP3 expression10. Recent research revealed that FK506-binding protein 51 binds to TIMP3, facilitating its connection to the Beclin1 complex. This interaction enhances the autophagic degradation of TIMP3 and significantly promotes the invasion and migration of RCC11. These findings underscore the important role of TIMP3 in RCC progression.

Inorganic As has been shown to enhance the expression of MMP genes, which play a role in degrading the ECM12, thereby influencing As-related cancers. In rat hepatocytes, Cd was found to decrease expressions of TIMP2 and TIMP3, which are positively regulated by ten-eleven translocation methylcytosine dioxygenase 1 (TET1), which participates in DNA demethylation13. Moreover, urinary levels of As and Cd exhibited a positive and significant correlation with TIMP1, a marker associated with renal damage14. Cell experiments have revealed that cells exposed to As developed pathological fibrosis features, potentially attributed to the upregulation of fibrosis-associated signaling molecules such as TIMP3 and MMP215. However, these studies provide inconsistent results concerning the relationship between As and Cd exposure and TIMP3.

The gene TIMP3 is found on chromosome 22q12.1-q13.216, and is considered a putative tumor suppressor gene. It belongs to a family of four members known as TIMPs, with TIMP3 a 24-kDa secreted glycoprotein inhibiting proteolytic activity of MMPs, and exhibiting anti-metastatic and anti-tumorigenic properties17. The functional significance of most reported TIMP3 variants remains unclear, although these single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) can be related to the clinical outcome of cancer. For instance, one study found a significant association between the TIMP3 rs9619311 TC/CC genotype and muscle-invasive urothelial cell carcinoma in non-smokers, whereas TIMP3 rs11547635 was not linked to this cancer18. One study indicated that the TIMP3 rs715572 AG/AA genotype was significantly associated with colorectal cancer relative to the GG genotype19. In terms of breast cancer, women of TIMP3 rs9609643 AA genotype exhibited a significantly lower risk compared to the GG genotype, while women with the TIMP3 rs8136803 TT genotype showed a significantly greater likelihood of breast cancer compared to the GG genotype20. Furthermore, the TIMP3 rs2234921 G allele showed an increased skin cancer risk when combined with high levels of As exposure, compared to the TIMP3 rs2234921 A allele combined with low As exposure levels21. However, there has been no investigation of the role of TIMP3 polymorphism in RCC. Therefore, we aimed to examine the association of TIMP3 polymorphism with clear cell RCC. Additionally, we explored whether TIMP3 polymorphism could modify the respective relationships of blood Cd and total urinary As concentration with clear cell RCC.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

The study was a case–control. The inclusion criteria for participants were those with pathological diagnosis of RCC or clinical imaging consistent with RCC, and those aged 20–80 years old. People without RCC or other cancers served as controls. Exclusion conditions included those with incomplete specimens and data or those who refused to sign the consent form. This study recruited 380 patients who were diagnosed with RCC through pathological confirmation. The control group consisted of 689 individuals who were matched with the age and sex of RCC patients, and they did not have RCC or any other malignancy6. Around 70% of the RCC patients had grade II or III tumors. Specifically, there were 281 cases of clear cell carcinoma, 27 of papillary carcinoma, 29 of chromophobe carcinoma, 6 of sarcoma, and 7 classified as “other.” Information regarding the cell type of 33 cases was not available. Because TIMP3 is related to angiogenesis mediated by vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and VEGFR-2, it is also a key marker of clear cell renal cancer10,22. Therefore, this study mainly used 281 people with clear cell RCC as cases. Prior to their participation, all study participants provided informed consent in writing, including questionnaire interviews and specimen collection. The Research Ethics Committee of National Taiwan University Hospital approved the research protocol (approval no. 201705091RINC, date 2021-07-02), and it was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki by the World Medical Association.

Questionnaire interview and biospecimen collection

The methodology for questionnaire interviews and information collection was previously detailed6. Blood samples were collected using an EDTA vacuum syringe in a volume of 5–8 mL and then processed with the separation of blood cells to measure Pb and Cd levels. Buffy coats were isolated for DNA extraction and subsequent TIMP3 genotyping. Additionally, spot urine samples were collected and kept at − 20 °C prior to analyzing As species.

Measurements of blood Cd and Pb and urinary As levels

Quantification of blood Cd and Pb levels was conducted using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA)23. The separation of arsenite, arsenate, monomethylarsinic acid, and dimethylarsinic acid was achieved through high-performance liquid chromatography (Merck Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan), followed by hydride generation coupled with an atomic absorption spectrometer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) to measure the concentration of the four substances24. The summed concentrations of these four urinary As species was termed total urinary As concentration, and this was then divided by urine creatinine concentration, thus adjusting for hydration status25. This analytical method is not affected by arsenobetaine, arsenocholine or arsenosugar found in seafood. Our previous study showed that the frequency of fish, shellfish, and seaweed consumption was not significantly associated with the concentration of inorganic arsenic and its methylated species26. For measurement methods, standard reference materials, recovery rate, detection limits, and reliability for metal measurements, see Supplementary Table S1.

Determining TIMP3 gene polymorphisms

To extract genomic DNA, the samples were subjected to digestion with proteinase K, followed by phenol–chloroform extraction. We selected six common TIMP3 SNPs from the Han Chinese population using Beijing HapMap data. The allelic exchange, global mutant allele frequency (MAF), and the gene’s polymorphism location of TIMP3 are shown in Table 1. The somatic mutation was performed by Agena MassARRAY platform with iPLEX reagent chemistry (Agena, San Diego, CA, USA). The specific PCR primer and extension primer sequences of TIMP3 rs715572, TIMP3 rs2234921, TIMP3 rs8136803, TIMP3 rs9609643, TIMP3 rs9619311, and TIMP3 rs11547635 were designed with Assay Designer software package (v.4.0) (Supplementary Table S2). Of genomic DNA sample (10 ng/µl), 1 µl was applied to mutiplex PCR reaction in 5-µl volumes containing 1 unit of Taq polymerase, 500 nmol of each PCR primer mix, and 2.5 mM of each dNTP (Agena, PCR accessory and Enzyme kit). Thermocycling was at 94 °C for 4 min followed by 45 cycles of 94 °C for 20 s, 56 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 1 min, then 72 °C for 3 min. Unincorporated dNTPs were deactivated using 0.3 U of shrimp alkaline phosphatase. The single base extension reaction was using iPLEX Pro enzyme, terminator mix, and extension primer mix, followed by 94 °C for 30 s followed by 40 cycles of 94 °C for 5 s, and five inner cycles of 56 °C for 5 s and 80 °C for 5 s, then 72 °C for 3 min (Agena, iPLEX Pro reagent kit). After the addition of a cation exchange resin to remove residual salt from the reactions, 7 nl of the purified primer extension reaction was loaded onto a matrix pad of a SpectroCHIP (Agena). SpectroCHIPs were analyzed using a MassARRAY Analyzer 4, with the calling by clustering analysis with TYPER 4.0 software. The distribution of all control genotypes obeyed Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium.

Statistical analysis

The Wilcoxon rank sum test was implemented for between-groups comparison of continuous variables. The distribution of categorical variables between the groups and whether the control group TIMP3 genotypes fitted Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium were determined using Chi-square test. In the control group, continuous independent variables were categorized into three groups, with the first tertile serving as the reference category. Multivariate logistic regression models were used for calculation of OR and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and so assess the relationship between clear cell RCC and the categorical independent variables. To examine linear trends in ORs across the strata of categorical independent variables, the categorical variables were treated as continuous variables. Haploview 4.1 software was employed to assess the strength of linkage disequilibrium (LD) by calculating D′ and r2 of Lewontin 127. Interactions between metal concentrations and TIMP3 polymorphisms in relation to clear cell RCC were evaluated using the median of metal concentration in the control group as the cutoff point. A logistic regression model with a product term was used to test for multiplicative interactions between the two variables. Additive interactions were evaluated using several measures, including attributable proportion (AP), synergy index, and relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI)28. Data analysis was conducted using SAS software (version 9.4; Cary, NC, USA), with two-tailed significance of p < 0.05, and marginally significant 0.05 < p < 0.1.

Results

Comparison of sociodemographic and lifestyle factors between clear cell RCC cases and controls

Table 2 displays a comparison of disease history, sociodemographics, and lifestyle factors between clear cell RCC patients and the non-RCC (controls). Between the groups, there were no significant differences in distributions of age and sex. The clear cell RCC patients exhibited a higher proportion of individuals with illiteracy and primary education level compared to the controls. In contrast to clear cell RCC cases, the control group reported significantly higher rates of occasional or frequent consumption of alcohol, tea, and coffee, but had a lower cumulative pack-year of smoking. The clear cell RCC patients had significantly higher rates of diabetes and hypertension than the controls.

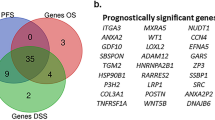

Polymorphisms and haplotypes of TIMP3 and clear cell RCC risk

Associations between polymorphisms and haplotypes of TIMP3 and RCC are given in Table 3. In multivariable adjusted models, clear cell RCC cases had significantly higher odds of having the TIMP3 rs715572 AA compared to the GG/GA genotype (OR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.01–2.56). Conversely, clear cell RCC cases had significantly lower odds of having the TIMP3 rs9609643 GA/AA genotype (OR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.44–0.91) compared to the GG genotype. There were no significant associations for other TIMP3 polymorphisms. Haplotype analyses identified two haplotype blocks within the TIMP3 gene (Supplementary Figure S1): block 1 (TIMP3 rs9619311 and TIMP3 rs2234921), and block 2 (TIMP3 rs9609643 and TIMP3 rs11547635). Among these, only block 2 exhibited high LD, with a D′ value of 0.97 (Figure S1A), and r2 values (Figure S1B) indicated the strength of the LD between these two polymorphisms. The A-C and A-T haplotypes in block 2 showed a significant inverse association with clear cell RCC compared to the G-C and G-T haplotypes, with an OR of 0.64 (95% CI, 0.46–0.89).

Metals and clear cell RCC risk

The clear cell RCC cases exhibited significantly higher levels of blood Cd, blood Pb, and total urinary As than controls (Table 4). Following multivariate adjustment, clear cell RCC cases with total urinary As levels > 25.04 µg/L had 1.87-fold (95% CI, 1.11–3.16) significantly higher odds of clear cell RCC than those with total urinary As levels ≤ 11.89 µg/L. Similarly, clear cell RCC cases demonstrated 5.41-fold (95% CI, 3.06–9.55) increased odds of blood Cd levels of > 1.64 µg/L compared to ≤ 0.92 µg/L after adjusting for multiple variables. However, blood Pb levels and clear cell RCC showed no significant association.

Interaction of metals and genotype or haplotype of TIMP3 on clear cell RCC risk

Table 5 presents the combined effects on clear cell RCC of TIMP3 polymorphisms and total urinary As levels, or blood Cd concentrations. After adjusting for multivariable, clear cell RCC cases showed 2.27-fold (95% CI, 1.23–4.18) increased odds of having total urinary As levels > 11.22 µg/L and possessing TIMP3 rs9609643 GG genotype compared to urinary total As levels ≤ 11.22 µg/L and TIMP3 rs9609643 GA/AA genotype. Furthermore, ORs progressively increased from having no risk factors (i.e., low total urinary As levels and TIMP3 rs9609643 GA/AA genotype) to having one risk factor (i.e., high total urinary As levels or TIMP3 rs9609643 GG genotype), and to having two risk factors (i.e., high total urinary As levels and TIMP3 rs9609643 GG genotype). There were similar associations when assessing the combination of blood Cd levels and TIMP3 rs9609643 genotype, and that of blood Cd or total urinary As levels and TIMP3 rs715572 genotype on clear cell RCC. The TIMP3 rs9609643 GG genotype tended to interact multiplicatively with high blood Cd level to increase the OR of clear cell RCC. However, all additive interactions were nonsignificant. The effects of the combination of TIMP3 haplotype and total urinary As, as well as blood Pb concentrations, on clear cell RCC, are presented in Supplementary Table S3. When examining the combined effects of blood Cd or total urinary As concentrations with the risky TIMP3 haplotype in block 2, the clear cell RCC OR significantly rose with dose as the number of risk factors increased, i.e., high blood Cd levels, high total urinary As concentrations, or presence of TIMP3 haplotype block 2 (G-C and G-T). However, all additive and multiplicative interactions were nonsignificant.

Negative and positive predictors for clear cell RCC

Finally, positive and negative predictors for clear cell RCC were determined using stepwise logistic regression analysis (Table 6). Age, sex, frequent and occasional consumption of alcohol and tea were identified as significant negative predictors for clear cell RCC. However, elevated blood Cd levels, a history of diabetes and hypertension, and the presence of the TIMP3 rs715572 AA genotype were significant positive predictors for clear cell RCC.

Discussion

There was a significant negative association between the TIMP3 rs9609643 GA/AA compared to the GG genotype, and the haplotype of TIMP3 (rs9609643 and rs11547635) A-C and A-T compared to G-C and G-T, with clear cell RCC. We also found a significant positive association between TIMP3 rs715572 (AA vs. GG/GA genotype) and clear cell RCC. Furthermore, high blood Cd levels showed a tendency to interact multiplicatively with TIMP3 rs9609643 (GG vs. GA/AA) increasing the OR for clear cell RCC.

There have been few investigations of TIMP3 rs9609643. A study found a 60% lower likelihood of breast cancer for women with the TIMP3 rs9609643 AA than the GG genotype (OR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.2–1.0)20. There have also been few studies on the relationship between TIMP3 rs715572 and cancer. Compared to the GG genotype, TIMP3 rs715572 AG/AA was associated with increased risk of colorectal cancer19. TIMP3 rs715572 (CC vs. CT/TT) was associated with survival of adenocarcinomas of the gastroesophageal junction29. In this study, we discovered a significant association between the TIMP3 rs9609643 GA/AA genotype and a reduced risk of clear cell RCC. In addition, TIMP3 rs715572 AA was significantly related with increased OR of clear cell RCC. To our knowledge, these findings are relatively novel in the clear cell RCC field.

Functional polymorphisms in TIMP3 genes have been implicated in the modulation of activity, thereby influencing the clinical characteristics of prostate cancer30. Patients carrying the TIMP3 rs9619311 TC + CC polymorphism showed an increased risk of prostate cancer recurrence, but TIMP3 rs11547635 was not associated with this cancer30. A study suggested that the TIMP3 rs2234921 GG genotype was marginally associated with a higher risk of skin cancer than AA/AG genotype21. The TIMP3 rs8136803 TT genotype showed a significantly greater risk of breast cancer compared to the GG genotype20. However, in our study, there was no association of TIMP3 rs2234921, TIMP3 rs8136803, TIMP3 rs11547635, or TIMP3 rs9619311 with clear cell RCC. These findings indicated inconsistent results from current studies concerning the relationship of TIMP3 rs2234921, TIMP3 rs8136803, TIMP3 rs11547635, and TIMP3 rs9619311 with cancer.

However, TIMP3 rs9609643 appeared to alter the association between blood Cd concentration and clear cell RCC. Individuals carrying TIMP3 rs9609643 GG genotypes had an increased risk of clear cell RCC associated with high blood Cd concentrations compared to those with TIMP3 rs9609643 GA/AA genotypes and low blood Cd concentrations in this study. This is likely the first study to examine the interaction of TIMP3 genetic polymorphisms with environmental pollutants, specifically Cd. These findings suggest that genetic variation in the TIMP3 promoter region may contribute to the development of Cd-induced clear cell RCC. It is possible that Cd induces oxidative stress, leading to the production of oxidative stress-sensitive metallothionein 2A, which in turn triggers the activity of TET1 (DNA demethylation) along with apolipoprotein E. Moreover, Cd has been shown to decrease the expression of TIMP2 and TIMP3, which are positively regulated by TET113, while TIMP3 expression can be reduced in cancer tissues in comparison with normal controls31. Additionally, the TIMP3 rs9609643 GG genotype may potentially alter protein expression by affecting transcription factor binding sites, thus disrupting the balance between TIMP3 and MMPs, impacting ECM remodeling32 and increasing the risk of clear cell RCC. However, experimental confirmation of these findings is warranted in future studies. To our knowledge, no other studies have examined the association of this polymorphism with clear cell RCC, and it is not known whether this SNP is functional. Therefore, it would be valuable to study TIMP3 function, which would further understand of the mechanisms of TIMP3 genotypes in clear cell RCC.

This study has several limitations. First, it is should be noted that this is a case–control study, and so the temporal relationship of environmental factors with clear cell RCC is difficult to clarify. Secondly, the assessment of total urinary As and blood Cd concentrations was based on a single sample. The reliability of these measurements relies on the assumption of a stable lifestyle and metabolism for all patients during the sample collection period. Thirdly, the study had a small sample size, which potentially limits generalizability of the results. Therefore, further validation using an increased sample size is necessary to ensure more robust and meaningful interpretations of the results. Despite these limitations, the study’s findings offer valuable insights into factors that may affect Cd-related clear cell RCC.

Conclusions

This study represents the first investigation to identify significant associations between the TIMP3 rs9609643 GA/AA and TIMP3 rs715572 AA genotype and clear cell RCC. Additionally, our observational study provides novel evidence indicating that the risk genotype of TIMP3 rs9609643 appears to modify the relationship between environmental factors (specifically blood Cd) and clear cell RCC.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Roberto, M. et al. Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Management: From Molecular Mechanism to Clinical Practice. Front. Oncol. 11, 657639 (2021).

Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71 (3), 209–249 (2021).

Chiang, C. J. et al. Incidence and survival of adult cancer patients in Taiwan, 2002–2012. JFormosMedAssoc 115 (12), 1076–1088 (2016).

Capitanio, U. et al. Epidemiol. Ren. Cell. Carcinoma Eur. Urol. ;75(1):74–84. (2019).

Panaiyadiyan, S. et al. Association of heavy metals and trace elements in renal cell carcinoma: A case-controlled study. UrolOncol 40 (3), 111 (2022).

Hsueh, Y. M. et al. Effect of plasma selenium, red blood cell cadmium, total urinary arsenic levels, and eGFR on renal cell carcinoma. SciTotal Environ. 750, 141547 (2021).

Brew, K. & Nagase, H. The tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs): an ancient family with structural and functional diversity. BiochimBiophysActa 1803 (1), 55–71 (2010).

Huang, H. L. et al. TIMP3 expression associates with prognosis in colorectal cancer and its novel arylsulfonamide inducer, MPT0B390, inhibits tumor growth, metastasis and angiogenesis. Theranostics 9 (22), 6676–6689 (2019).

Su, C. W. et al. Loss of TIMP3 by promoter methylation of Sp1 binding site promotes oral cancer metastasis. Cell. Death Dis. 10 (11), 793 (2019).

Masson, D. et al. Loss of expression of TIMP3 in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Eur. J. Cancer. 46 (8), 1430–1437 (2010).

Mao, S. et al. FKBP51 promotes invasion and migration by increasing the autophagic degradation of TIMP3 in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cell. DeathDis. 12 (10), 899 (2021).

Zhang, R. et al. Constructing interactive networks of functional genes and metabolites to uncover the cellular events related to colorectal cancer cell migration induced by arsenite. Environ. Int. 174, 107860 (2023).

Hirao-Suzuki, M. et al. Cadmium-stimulated invasion of rat liver cells during malignant transformation: Evidence of the involvement of oxidative stress/TET1-sensitive machinery. Toxicology 447, 152631 (2021).

Mahmoodi, M. et al. Urinary levels of potentially toxic elements (PTEs) in female beauticians and their association with urinary biomarkers of oxidative stress/inflammation and kidney injury. Sci. Total Environ. 878, 163099 (2023).

Chang, Y. W. & Singh, K. P. Arsenic induces fibrogenic changes in human kidney epithelial cells potentially through epigenetic alterations in DNA methylation. JCell Physiol. 234 (4), 4713–4725 (2019).

Apte, S. S., Mattei, M. G. & Olsen, B. R. Cloning of the cDNA encoding human tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-3 (TIMP-3) and mapping of the TIMP3 gene to chromosome 22. Genomics 19 (1), 86–90 (1994).

Rai, G. P. & Baird, S. K. Tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-3 has both anti-metastatic and anti-tumourigenic properties. Clin. Exp. Metastasis. 37 (1), 69–76 (2020).

Weng, W. C. et al. Impact of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-3 genetic variants on clinicopathological characteristics of urothelial cell carcinoma. J. Cancer. 14 (3), 360–366 (2023).

Wang, N. et al. MMP-2, -3 and TIMP-2, -3 polymorphisms in colorectal cancer in a Chinese Han population: A case-control study. Gene 730, 144320 (2020).

Peterson, N. B. et al. Polymorphisms in tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases-2 and – 3 and breast cancer susceptibility and survival. Int. J. Cancer. 125 (4), 844–850 (2009).

Wu, M. M. et al. TIMP3 Gene Polymorphisms of -1296 T > C and – 915 A > G Increase the Susceptibility to Arsenic-Induced Skin Cancer: A Cohort Study and In Silico Analysis of Mutation Impacts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. ;23(23). (2022).

Qi, J. H. et al. A novel function for tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-3 (TIMP3): inhibition of angiogenesis by blockage of VEGF binding to VEGF receptor-2. Nat. Med. 9 (4), 407–415 (2003).

Hsueh, Y. M. et al. Association of blood heavy metals with developmental delays and health status in children. SciRep 7, 43608 (2017).

Hsueh, Y. M. et al. Urinary levels of inorganic and organic arsenic metabolites among residents in an arseniasis-hyperendemic area in Taiwan. JToxicolEnvironHealth A. 54 (6), 431–444 (1998).

Barr, D. B. et al. Urinary creatinine concentrations in the U.S. population: implications for urinary biologic monitoring measurements. Environ. Health Perspect. 113 (2), 192–200 (2005).

Hsueh, Y. M. et al. Urinary arsenic speciation in subjects with or without restriction from seafood dietary intake. ToxicolLett 133 (1), 83–91 (2002).

Barrett, J. C., Fry, B., Maller, J. & Daly, M. J. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics 21 (2), 263–265 (2005).

VanderWeele, T. J. & Knol, M. J. A Tutorial on Interaction. Epidemiol. Methods. 3 (1), 33–72 (2014).

Bashash, M. et al. Genetic polymorphisms at TIMP3 are associated with survival of adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction. PLoSOne 8 (3), e59157 (2013).

Hsieh, C. Y. et al. Impact of Clinicopathological Characteristics and Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase-3 Polymorphism Rs9619311 on Biochemical Recurrence in Taiwanese Patients with Prostate Cancer. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health ;20(1). (2022).

Su, C. W. et al. Plasma levels of the tissue inhibitor matrix metalloproteinase-3 as a potential biomarker in oral cancer progression. Int. J. Med. Sci. 14 (1), 37–44 (2017).

Fan, D. & Kassiri, Z. Biology of Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase 3 (TIMP3), and Its Therapeutic Implications in Cardiovascular Pathology. Front. Physiol. 11, 661 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (MOST 106-2314-B-038-066, MOST 106-2314-B-002-235-MY3, MOST 107-2314-B-038-073, MOST 108-2314-B-038 -089, MOST 109-2314-B-038-081, MOST 109-2314-B-038-067, MOST 110-2314-B-038-054, MOST 111-2314-B-002-240-MY3, MOST 111-2314-B-038-052), and the National Science and Technology Council of Taiwan (NSTC 112-2314-B-038-094).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization and study design, YMH and CYH; writing—original draft, CYH; writing—review and editing, YMH; statistical analysis, YLH; material preparation, data collection, and analysis, MCC, CYW, HSS, YCL, and YSP; supervision, YMH.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, CY., Chen, MC., Wu, CY. et al. Interaction of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 3 gene polymorphism, blood cadmium and total urinary arsenic levels on clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Sci Rep 15, 10267 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94807-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94807-3