Abstract

Rockfalls on mountainous roads pose significant safety risks to pedestrians and vehicles, particularly in remote areas with underdeveloped communication infrastructure. To enable efficient detection, this study proposes a rockfall detection system based on embedded technology and an improved Yolov8 algorithm, termed Yolov8-GCB. The algorithm enhances detection performance through the following optimizations: (1) integrating a lightweight DeepLabv3+ road segmentation module at the input stage to generate mask images, which effectively exclude non-road regions from interference; (2) replacing Conv convolution units in the backbone network with Ghost convolution units, significantly reducing model parameters and computational cost while improving inference speed; (3) introducing the CPCA (Channel Priori Convolution Attention) mechanism to strengthen the feature extraction capability for targets with diverse shapes; and (4) incorporating skip connections and weighted fusion in the Neck feature extraction network to enhance multi-scale object detection. Experimental results demonstrate that Yolov8-GCB improves AP@0.5 and AP@0.75 by 1.2% and 1%, respectively, while reducing the number of parameters by 14.1% and the GFLOPs by 16.1% and increasing inference speed by 20.65%. This method provides an effective technological solution for real-time rockfall detection on embedded devices and can be extended to other disaster scenarios, such as landslides and debris flows, in regions with limited infrastructure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rockfall on mountain highways refers to stones that roll onto the road surface, predominantly occurring in mountainous regions with steep slopes, constituting a common natural hazard. Characterized by their small scale and sudden occurrence, rockfalls are more challenging to detect accurately compared to landslides or other geological disasters, making prevention measures difficult to implement. Additionally, once a rockfall occurs, it can readily disrupt traffic, damage vehicles, and pose severe threats to pedestrian safety. Presently, rockfall monitoring largely relies on patrolling highway personnel, which fails to provide real-time detection, incurs high labor costs, and is inefficient. Human subjectivity and uncertainty hinder the prompt mitigation of traffic hazards resulting from rockfalls. Therefore, researching intelligent rockfall detection systems that can promptly identify and alert potential rockfall incidents is of paramount significance to minimize casualties and property losses1,2.

Casagli3 and Schneider4 have conducted monitoring on slopes in areas prone to rockfalls using ground laser scanning, Doppler radars, and LiDAR to assess real-time displacement and deformation of the slope, thereby predicting rockfall occurrences in those zones. Farmakis5 have been able to combine Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) technology with automated change detection and clustering workflows to achieve spatially precise monitoring and inventory of rockfalls. Arosio6 and Ulivieri7 have collected acoustic (seismic and infrasound) characteristics from numerous rockfall events, utilizing icroseismic transducers, high-sensitivity infrasound sensors, and seismic sensors for real-time analysis of vibrations, acoustics, and infrasound signals in the monitored areas. Ullo8 proposed a new landslide detection method that leverages the capabilities of Mask R-CNN by employing pixel-based segmentation to identify object layouts, as well as transfer learning for training the proposed model. By comparing collected acoustic features, they predict rockfall incidents. Such methods are effective for monitoring large-scale rockfall events, but their performance is poor in detecting small-scale rockfall events. Additionally, these methods require the deployment of a large number of sensors, resulting in a high monitoring cost. The research efforts of the aforementioned individuals have primarily concentrated on determining whether landslide-induced rockfalls have occurred on slopes, but they are unable to effectively acquire detailed information regarding the quantity, location, and size of rocks that have accumulated on the road surface. The employment of video monitoring can effectively compensate for these shortcomings.

In practical scenarios, information about the quantity, location, and size of rockfalls is crucial for assessing the risk level of rockfall disasters. Fantini et al.9 and Cheng et al.10 have implemented real-time video acquisition in areas susceptible to rockfalls. By analyzing the motion characteristics of rockfalls in the footage, they compare frames sequentially. Specifically, they rely on optical principles, performing frame differencing between consecutive frames of the video stream to obtain pixel differences at corresponding positions. A threshold is then set to identify distinct positions between adjacent frames, potentially indicating a rockfall. However, these approaches are prone to false alarms and missed detections due to the influence of moving vehicles and pedestrians in the field environment. The aforementioned studies have enhanced the rockfall detection task with the capability to obtain more detailed disaster information. However, the technology is susceptible to false alarms and omissions due to the influence of moving vehicles and pedestrians in the field environment. Consequently, this technology is predominantly applied in areas with fewer external disturbances, such as along railway lines and valley slopes.

To address the interference caused by moving vehicles and pedestrians in video monitoring, our research direction has shifted towards the field of deep learning object detection. Unlike traditional video detection methods that rely solely on optical characteristics to detect moving objects, deep learning object detection can employ artificial intelligence methods to recognize and detect rockfalls, thereby excluding other interfering factors in the video. With the advent of deep learning, the intricate mapping relationships within its deep networks enable identifying rockfalls in video streams based on their inherent characteristics, offering a potential solution to the issues of false positives and false negatives in traditional video processing11. Object detection algorithms in deep learning can be categorized into one-stage and two-stage methods. One-stage detectors like YOLO12, SSD13, OverFea14, and RetinaNet15 simultaneously predict object locations and classify them, consuming fewer computational resources and time, thus operating faster. Two-stage detectors, including R-CNN16 Fast R-CNN17, Faster R-CNN18, and Mask R-CNN19, use two separate network models, requiring two computations for object localization and classification, which are more computationally intensive and slower. Under resource-constrained and real-time detection tasks, one-stage algorithms hold a comparative advantage. Among one-stage detectors, the YOLO algorithm stands out for its speed, simplicity, strong generalization capabilities, and rapid iterative updates. Consequently, this study employs the YOLO algorithm for the task of rockfall detection on highways.

The YOLO series of algorithms transform object detection into a regression problem by dividing images into grids, where each grid predicts bounding boxes and categories of objects, facilitating object detection. It has been widely applied in fields such as smart firefighting, autonomous driving, object counting, and industrial automation. Zheng et al.20 addressed fire smoke detection in intelligent firefighting scenarios by proposing an improved Yolov5 model for effective early warning of smoke occurrences in video frames. Yang et al.21 focused on traffic sign detection in autonomous driving, suggesting an enhanced Yolov5 algorithm for judging traffic signs captured by vehicles to aid subsequent control in autonomous driving. In the domain of rockfall detection, Chen et al.22 modified Yolox for rockfall detection, incorporating deep learning into the task. They employed camera surveillance on-site, transmitted videos to a backend for processing, and fed the results back to the site for alarm purposes, achieving promising results. However, this method necessitates video streaming to remote servers, requiring good communication conditions. In mountainous highways with poor communication, this approach encounters significant limitations.

Therefore, this paper adopts embedded technology to establish a rockfall detection system based on machine vision, installed along roads prone to rockfall hazards. The system performs real-time intelligent detection of rockfalls locally using improved deep learning algorithms. On the hardware side, it employs cameras for data collection, Raspberry Pi for data processing, and DTU for transmitting results. On the software front, to focus the rockfall detection task on the road area, we introduce a lightweight Deeplabv3+23 road segmentation module at the input of Yolov8, generating road area mask images to ensure the algorithm only attends to rockfall occurrences on the road. We propose the Yolov8-GCB rockfall detection algorithm based on the Yolov8 framework. To reduce the model’s parameter count and achieve compactness, GhostConv convolutions24 replace basic convolutions in the feature extraction network, and a lightweight C2F-G module is designed to replace the C2F feature extraction module. Moreover, a CPCA (Channel prior convolutional attention) attention mechanism25 is introduced in the deeper layers of the feature extraction network, enhancing the model’s focus on target regions and its capability to recognize shape-varying targets. Inspired by BIFPN26, we incorporate weighted fusion and skip connections into Yolov8’s multi-scale fusion part, boosting the network’s performance in detecting small and multi-scale targets. Experimental results demonstrate that the improved Yolov8-GCB surpasses Yolov827, Yolov728, Yolov629, and Yolov530 in terms of both parameter count and computational load, while slightly enhancing detection accuracy. This enables more efficient local processing on resource-limited embedded devices, particularly in areas with poor communication conditions, for intelligent rockfall detection.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In “Introduction” Section, the theoretical framework of YOLOv8 i-s discussed in detail. In “Theoretical Framework of YOLOv8” Section, the optimization of the YOLOv8 algorithm is demonstrated, including the use of an improved Deeplabv3+ model for road segmentation, lightweight modifications to the backbone network, integration of attention mechanisms in the backend of the backbone network, and improvements to the feature fusion architecture. In “YOLOv8 Algorithm Optimization” Section, the experimental results and analysis are introduced. “Discussion” Section discusses the aforementioned experimental results. Finally, “Conclusion” Section is the conclusion of our paper.

Theoretical framework of YOLOv8

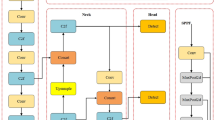

The structure of the Yolov8 algorithm is depicted in Fig. 1, consisting of four main components: Input, Backbone, Neck, and Head. The input stage includes modules for resizing images, image augmentation, and data normalization to preprocess the input image data. The backbone network incorporates residual blocks to facilitate the extraction of deep features from feature maps. The neck component is responsible for effectively fusing the features extracted by the backbone network. The detection head predicts the class and location information of targets. This modular design of Yolov8 enables it to exhibit outstanding performance in object detection tasks.

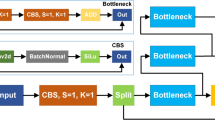

YOLOv8’s network architecture is built upon the Darknet-53 foundation, which consists of key modules such as Cross-Stage Partial Network (CBS), CSPDarknet53 to 2-Stage FPN (C2F), and Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fast (SPPF). CBS serves as the fundamental convolution unit, comprised of 2D Convolution (Conv2D), Batch Normalization (BatchNorm2d), and an Sigmoid Linear Unit (SiLU). As shown in Fig. 2a, the CBS module sequentially applies 2D convolution, batchNorm2d, and Sigmoid Linear Unit to the input data.C2F, depicted in Fig. 2b, is a principal module for feature extraction in deep learning networks. It incorporates residual connections, allowing YOLOv8 to maintain its lightweight nature while enhancing gradient flow information and mitigating the issue of vanishing gradients in deep neural networks. As illustrated in Fig. 2c, SPPF is an adaptation of Spatial Pyramid Pooling that addresses distortions and redundant image features caused by image cropping and scaling. It improves the speed at which these issues can be resolved, ensuring better preservation of image information.

Yolov8 retains the bidirectional pyramid structure of PAN (Path Aggregation Network) from Yolov5, Yolov6, and Yolov7 in its feature fusion section. It employs Upsample to propagate strong semantic features from deeper to shallower layers, followed by CBS to convey localization features from shallower to deeper layers. As shown in Fig. 3, Concatenation is then used to integrate shallow-level localization features with deep-level semantic features. In addition, Yolov8 eliminates the 1*1 convolution blocks previously used, thereby reducing the parameter count and computational load during the feature fusion process. This architectural modification enhances efficiency while maintaining detection performance.

YOLOv8 adopts the decoupled head structure introduced by YOLOX. As depicted in Fig. 4, this design separates the classification and regression tasks for separate handling. Initially, a 1 × 1 convolution is employed to downscale the output. Subsequently, in the classification and regression branches, two separate 3 × 3 convolutions are utilized. By replacing the original detection head with the decoupled head, the prediction accuracy is improved, and the convergence speed of the network becomes faster. This architectural change optimizes the model’s performance and training efficiency.

YOLOv8 algorithm optimization

Road segmentation using improved Deeplabv3+ model

In the road video images captured by the camera, there are both road areas and non-road areas. Stones present in the non-road regions can interfere with the rockfall monitoring task. To address this issue, we incorporate a lightweight Deeplabv3+ road segmentation module at the input of the YOLOv8 network. This module generates a road area mask image, ensuring that the algorithm focuses solely on rockfall occurrences within the road area. The framework of the lightweight Deeplabv3+ road segmentation module, as shown in Fig. 5, initially involves the fact that the original Deeplabv3+ model’s backbone network has a large number of parameters, making it unsuitable for resource-constrained embedded devices. We substitute the Deeplabv3+ backbone with MobileNetV2 to reduce the model’s parameter count. However, the lightweight Deeplabv3+ model, after modification, may still generate masks with misclassification and holes when segmenting the road area, due to factors like lighting and occlusions. To address these issues, we perform morphological operations on the mask. Specifically, a closing operation is conducted, which first dilates and then erodes the mask, filling in any holes present. Region selection is then carried out, selecting the largest area in the mask to eliminate falsely detected regions. After all the processes in Fig. 5a, the final road area mask is obtained, effectively assisting the YOLOv8 network in precisely focusing on rockfall detection within the road region.

Lightweight modifications of the backbone network

Rockfalls typically occur on mountainous highways with poor communication conditions, leading to difficulties in video stream transmission and significant latency issues. Utilizing embedded devices to process video data on-site is a viable solution to overcome these network transmission challenges. Embedded devices offer advantages such as low power consumption, compact size, and high mobility, but they have limited computing power compared to desktops, servers, and other larger devices. To ensure smooth operation of the YOLOv8 algorithm on such devices, lightweight modifications are crucial. Therefore, in this study, we have redesigned the backbone of YOLOv8 (as shown in Fig. 6).Firstly, we substitute all CBS (Channel Separation Convolution) units in the network with GCBS (Ghost Convolutional Basic Units). Secondly, we propose a lightweight feature extraction structure called C2F-G to replace the C2F module in the YOLOv8 network.

Improvements to the CBS convolutional block

GCBS, as shown in Fig. 7a, replaces Conv2D in CBS with GhostConv to create a convolutional unit that generates more feature maps at a lower computational cost. Figure 7b illustrates that traditional Conv2D has a high parameter count. To achieve lightweight design, we employ the Ghost Convolution depicted in Fig. 7c. The feature maps produced by Ghost Convolution consist of two parts: one generated by a standard Conv2D operation on the input feature maps, and the other derived through a linear transformation of the output from the first part.

To delve deeper into the computational complexity and parameter count of traditional Conv2D convolutions compared to Ghost Convolution, consider an input feature map F ∈ R^(C × H × W) that, after convolution, produces an output F′ ∈ R^(C′ × H′ × W'). Assuming we neglect nonlinearity from batch normalization (bn) and the activation function relu, the ratio of parameters and computations between traditional Conv2D and Ghost Convolution can be calculated using Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively:

Let \(r_{s}\) represent the computation ratio, and \(r_{c}\) denote the parameter ratio. Here, C and C′ are the numbers of input and output channels, H and H′ are the heights of input and output data, W and W′ are the widths of input and output data, k is the size of the conventional convolution kernel, d is the size of the linear transformation convolution kernel, and S is the number of linear transformations. In this context, C′/S represents the number of output channels from the first transformation, and S-1 accounts for the omitted identity mapping that doesn’t require computation.

Through algebraic derivations, we find that both \(r_{s}\) and \(r_{c}\) are equal to S. Since S is an integer greater than 1, increasing the value of S leads to a smaller computation and parameter count for Ghost Convolution compared to traditional Conv2D.

Improvements to the C2F convolutional block

In the C2F module, multiple Bottleneck structures are included. To reduce the number of parameters and computational load, all Bottlenecks in the C2F have been replaced with GhostBottleneck structures, and the resulting C2F is denoted as the C2F-G module. The Bottleneck, as shown in Fig. 8a, consists of two CBS stacked together; the GhostBottleneck, as depicted in Fig. 8b, is divided into two scenarios: when the stride is 1, it is composed of two GhostConvs stacked together, and when the stride is 2, an additional DWConv (depthwise separable convolution) is included. Since GhostConv has a smaller computational load and parameter count compared to CBS, and DWConv is only used to achieve the feature map size adjustment function that GhostConv does not possess, it also has a minimal computational load and parameter count. Therefore, the GhostBottleneck has a lower parameter and computational load, and the C2F-G module can lightweight the YOLOv8 model.

Integration of attention mechanisms in the backbone network’s backend

To enable intelligent rockfall detection on resource-limited embedded devices, it is crucial to not only lighten the model but also enhance detection accuracy. Rockfalls exhibit diverse shapes, requiring an attention mechanism that focuses on the varying shapes to direct attention to the relevant local regions. The Channel prior convolutional attention (CPCA) convolutional attention mechanism effectively captures shape variations, making it well-suited for detecting shape-changing rockfalls. As a result, we incorporate the CPCA attention mechanism into the backend of the backbone network (as depicted in Fig. 9a).

CPCA is an efficient channel-prior convolutional attention method derived from CBAM. It improves the SA (Spatial Attention) mechanism of the CBAM (Convolutional Block Attention Module) by proposing a dynamically distributed spatial attention mechanism. This shifts the CBAM’s strategy of uniformly weighting spatial attention across all feature maps to a strategy of dynamically distributing spatial attention weights across all feature maps, thereby capturing richer spatial information. We believe that the shape information of objects in an image is closely related to the spatial information of feature maps, and the acquisition of abundant spatial information will enhance the detection performance of targets with complex shape information, such as rockfalls. As illustrated in Fig. 9b, the CPCA channel-prior convolutional attention module sequentially performs channel attention (CA) and spatial attention (SA).

The Channel Attention (CA) module aims to explore the relationships among channels in the feature map. In this module, the feature map F is first processed using MaxPool and AvgPool operations to aggregate spatial information from the image. The resulting two spatially distinct context descriptors are then fed into a shared Multilayer Perceptron (MLP). The outputs from the MLP are summed element-wise and passed through a Sigmoid non-linearity (\(\sigma\)) to generate the Channel Attention Map. Finally, the channel attention map is applied to the feature map F to produce the channel-aware feature map \(F_{C}\), as shown in Eqs. (3) and (4):

The Spatial Attention (SA) module explores the spatial relationships within the feature map. In contrast to the SA part in CBAM, the CPCA’s SA part avoids enforcing uniformity across the spatial attention maps in each channel by adopting a dynamic distribution across both the channel and spatial dimensions. In this module, multi-scale depth convolutions are applied to \(F_{C}\) to capture the spatial relationships between features while preserving the channel attention effects. The feature maps resulting from these multi-scale depth convolutions are then summed element-wise to generate the Spatial Attention Map. Afterward, a 1 × 1 convolution is applied to the spatial attention map, followed by element-wise fusion with the channel-aware feature map \(F_{C}\) to produce a more refined attention map, denoted as \(\hat{F}\). This process can be mathematically represented by Eqs. (5) and (6):

DwConv represents deep convolution and Branchi represents the ith branch.

Improved of feature fusion architecture

During rockfall detection on highways, rocks that are distant from the camera appear as small objects in the images, making them difficult to identify. To address this issue, we adopt the idea of skip connections and weighted fusion from BiFPN to enhance the feature fusion in YOLOv8. As depicted in Fig. 10, During the process of deep feature extraction, information about small targets is prone to be lost. We have added an additional edge between the original input and output nodes at the same level, reducing the loss of small target information due to deep feature extraction and enhancing the model’s detection capability for small targets. Weighted fusion refers to the addition of an extra learnable weight based on the contribution of each input feature, effectively integrating features of different scales, allowing the model to dynamically allocate feature fusion according to the size distribution of targets in the dataset. In the rockfall detection problem, most of the targets in the rockfall dataset we established are small. Weighted fusion can dynamically increase the weight of shallow feature fusion, enabling this feature fusion structure to capture more details and subtle information contained in the shallow layers, thereby improving the detection capability for small rockfalls. In the context of YOLOv8, we define different scale features as \(P_{i}^{in}\) (i = 1,2,3,4), the intermediate layer feature as \(P_{3}^{td}\), and the output features after multi-scale fusion as \(P_{i}^{out}\) (i = 1,2,3,4). We assign weights W to these features, with a small constant \(\varepsilon\) = 0.0001 to ensure numerical stability. Let’s analyze the most complex P3 layer, as illustrated by Eqs. (7–8). The output from the P3 layer to the detection head is the result of the weighted fusion process, which contains more refined feature information.

Experimental results and analysis

Experimental setup

The experimental setup in this study consists of a desktop computer equipped with a Windows 11 operating system, an i9-13900KF CPU, an RTX A6000 GPU with 48GB of video memory, and 64GB of RAM. All models utilized are based on PyTorch version 1.9.1, with CUDA version 11.7 and cuDNN version 7.6.5.

Data collection and label

For the road segmentation component, our dataset is collect from various sources, including data collected by the highway department, images taken by ourselves, and others. The dataset consists of a total of 6,348 images, featuring different weather conditions such as daytime, rainy days, snowy days, and so on,. The photo resolution is 640 * 360, and label is used for single-category annotation related to the road surface, as depicted in Fig. 11. This comprehensive collection of images ensures the model is exposed to a wide range of scenarios, enhancing its ability to generalize and accurately segment roads under various conditions31.

For the object detection component, our image data was sourced from multiple channels, such as online collections, highway department records, and self-shot photographs. After screening, these data retain their original image resolution and use labelimg for single-category annotation of rockfalls, as shown in Fig. 12. The images were annotated using the labelimg software. Following annotation, data augmentation techniques were applied, including adding noise, rotation, and cutout operations, resulting in a total of 2173 samples. Each sample consists of an image and its corresponding XML file, which serve as the training dataset. The dataset was then randomly split into a training set, a validation set, and a test set following an 8:1:1 ratio. The training set contains 1738 samples, the validation set has 217 samples, and the test set consists of 218 samples. The labeling process for the dataset is illustrated in Fig. 12. This comprehensive and balanced dataset ensures effective training and evaluation of the object detection model under various conditions.

Model training parameters configuration

In this experiment, the input image resolution is set to 640 × 640 pixels. Using higher-resolution images as inputs enhances the network’s ability to learn finer details. The model training is initialized and fine-tuned to adapt to the specific task at hand, aiming to find the optimal parameter combination for this task. During the training process, the batch size is set to 16, and the Adam optimizer is employed to update the model parameters. Each experiment is configured for 1000 epochs, with training terminated if there is no change in performance across 100 consecutive epochs. This strategy ensures efficient learning while preventing overfitting.

Evaluation metrics

In this paper, we evaluate the performance of the improved Yolov8 algorithm using three metrics: Average Precision (AP), parameter count, and GFLOPs.

Average Precision (AP) is a measure of the average classification performance for a single class. It represents the area under the Precision-Recall (P-R) curve in the first quadrant. The calculation formula for Average Precision is as follows:

Indeed, a higher Average Precision (AP) value signifies higher detection accuracy for a specific class. AP measures the model’s ability to correctly detect and locate objects in the image. When evaluating the overlap between predicted bounding boxes and ground truth boxes, two commonly used thresholds are 0.5 and 0.75.

Model parameter count refers to the aggregate of trainable parameters within all layers, encompassing weights and biases in neural networks. The magnitude of parameters often impacts a model’s performance and training time. A higher number of parameters suggests a more complex model, which might necessitate larger amounts of data and extended training periods. However, this complexity could also enhance the model’s expressive capacity.

GFLOPs is a common metric used in deep learning and neural network training to gauge computational complexity and efficiency. It quantifies the number of floating-point operations performed during a forward pass. A higher GFLOPs value indicates that the model requires more floating-point operations, implying a need for increased computational resources and time for inference or training tasks. When selecting models, especially in resource-constrained environments like embedded devices, considering both GFLOPs and parameter count is crucial to ensure efficient execution within the given hardware constraints.

Result analysis

Selection of base networks in the YOLO series

To determine which among Yolov5, Yolov6, Yolov7, and Yolov8 is best suited for the task of road rockfall detection, we trained models using a self-built dataset and performed a comparative analysis of various metrics on the test set, including AP@0.5, AP@0.5-0.75, model parameter count, and model computational load. The results for all four frameworks in the road rockfall detection task are presented in Table 1. From the table, it is evident that Yolov8 stands out due to its significant reductions in model parameter count, computational load, and model file size, as well as its superior performance in the AP@0.5 and AP@0.75 metrics. As a result, this paper builds upon the Yolov8 framework to further enhance and optimize the road rockfall detection task.

Road segmentation with the Deeplabv3+ model

After refining the DeepLabv3+ model, we integrated it into the input of YOLOV8, ultimately achieving automatic road segmentation. The experimental results of our lightweight modification to DeepLabv3+ are shown in Table 2. Under identical experimental conditions, our improved DeepLabv3+ mv2 model outperforms the original DeepLabv3+ in terms of higher AP values, while having fewer parameters and computational requirements. These experimental findings validate the effectiveness of our modifications to the DeepLabv3+ model.

In Fig. 13, we showcase the experimental results of applying the improved DeepLabv3+ mv2 model for road segmentation. The first row presents the original roads. The second row the results from the original DeepLabv3+ model, while the third row the results from the lightweight DeepLabv3+ mv2 model. The fourth row the results form optimized output of the DeepLabv3+ mv2 model.Upon comparing DeepLabv3+ with DeepLabv3+ mv2, we observe that the lightweight version, DeepLabv3+ mv2, performs better in road segmentation. However, there are still instances of false detections (as seen in the third column) and center hole segmentation issues (as seen in the fourth column). To tackle these problems, we optimize the output of the DeepLabv3+ mv2 model, as demonstrated in the fourth row, successfully achieving efficient road segmentation.

Ablation study on the improved YOLOv8 network

After implementing the lightweight modifications on Yolov8, we refer to the updated version as Yolov8-G. To validate the effectiveness of the lightweight improvements, we compared Yolov8-G with the original Yolov8 on the same dataset, as shown in Table 3. Following the reconfiguration of YOLOV8’s backbone, the Yolov8-G network exhibits a significant reduction of 19.8% in GFLOPs and a 20.4% decrease in parameter count. Meanwhile, there is only a slight decline in the AP@0.5 and AP@0.75 metrics. From the four indicators in Table 3, it is evident that replacing a substantial number of Conv2D convolutions in the backbone with Ghost convolutions notably reduces the hardware requirements, making it more suitable for deployment on resource-constrained embedded devices.

Attention mechanisms can improve the accuracy of object detection with a minimal increase in computational load. In this paper, Setnet, CBAM, and CPCA attention mechanisms are respectively added to the backend of the YOLOv8 backbone network and applied to the same dataset, with the results shown in Table 4. The improved spatial attention mechanism, CPCA, introduced in this paper, outperforms both Setnet and CBAM attention mechanisms in terms of average accuracy metrics. It has been found through research that the single CA (Setnet) improves the precision of the rockfall detection task, while the combination of CA and conventional SA (CBAM) is inferior to the YOLOv8 algorithm. The combination of CA and improved SA (CPCA) achieves the highest precision in rockfall detection tasks. In summary, the improved SA component significantly contributes to the accuracy improvement of rockfall detection tasks, and CPCA is more suitable for feature extraction of rockfall targets with variable shapes. Indeed, the placement of the CPCA attention mechanism at different points within the Yolov8 backbone network influences the model’s overall performance. Consequently, we trained the model with CPCA integrated into the shallow, middle, and deep layers of feature extraction, as shown in Table 5. By comparing the results, it is clear that incorporating CPCA into the deeper layers of the Yolov8 backbone leads to superior performance enhancements. In summary, for the rockfall detection task, adding the CPCA attention mechanism to the deeper layers of the Yolov8 backbone network proves to be more effective in enhancing the performance of the rockfall detection task. Concurrently, we conducted heatmap analysis after the backbone network. By comparing the heatmaps, we analyzed the effects of the original model and the model with the CPCA attention mechanism added to the backend. Figure 14a shows the heatmap of the original model, while Fig. 14b displays the heatmap of the model with the CPCA attention mechanism added to the backend. As can be seen from the figures, adding the CPCA attention mechanism to the backend can effectively enhance the model’s focus on the target of falling rocks during feature extraction.

After improving Yolov8 with the feature fusion enhancement, we refer to it as Yolov8-B. To validate the effectiveness of our feature fusion improvements, we apply both Yolov8-B and the original Yolov8 on the same dataset, as shown in Table 6. The results demonstrate that with a slight increase in parameter count and computational load, Yolov8-B shows improvements in the AP@0.5 and AP@0.75 metrics. Consequently, it can be concluded that Yolov8-B effectively enhances the accuracy of rockfall detection.

Finally, we made improvements to the Yolov8 network in three aspects: lightweight optimization, CPCA attention mechanism, and feature fusion, resulting in the Yolov8-GCB model. We applied both Yolov8 and Yolov8-GCB on the same dataset, and the results are presented in Table 7. Not only a significant reduction in parameter count and computational load, the Yolov8-GCB model exhibits notable improvements in detection accuracy, validating the effectiveness of our proposed algorithm.

Additionally, we compared the inference speed of YOLOv8-GCB with that of YOLOv8, with the detection results shown in Fig. 15. Figure 15a is the detection effect diagram of YOLOv8, and Fig. 15b is the detection effect diagram of YOLOv8-GCB. The red number in the upper left corner of each figure represents the average time required to repeatedly infer the image 100 times. By comparison, it can be observed that the inference speed of YOLOv8-GCB is significantly better than that of the YOLOv8 model, with an improvement of 20.65% in inference speed.

Rockfall detection system implementation and application

The rockfall detection system constructed in this paper is illustrated in Fig. 16. It employs Hikvision DS-2DE4423IW-D/GLT/XM(XM)(E) cameras for video capture, Raspberry Pi 4B with 8GB RAM as the data processing unit, and a DTU (Data Transfer Unit) for wireless communication. The system is powered by solar energy. Upon the occurrence of a rockfall event, the system sends the detected information, including the number, location, and time of the event, to the server.

The operational workflow of the system constructed in this paper is outlined in Fig. 17, comprising two main processes. The first process deals with the video stream returned by the camera, promptly decoding the video and clearing the decoded images to prevent memory overflow issues. The second process is responsible for detection, warning, and information transmission. It employs the improved Yolov8 object detection algorithm to analyze the images. If no rockfall is detected, the Yolo algorithm is repeatedly called for continuous monitoring. Upon detecting a rockfall, the system activates the audible and visual alarm. Concurrently, it obtains the location and the number of bounding boxes marking the rocks. Ultimately, the system relays the rockfall count, position, and timestamp data to the server via DTU.

We have implemented the rockfall detection system in three sections of G210 in Chang’an District, Xi’an City, Shaanxi Province, namely G210 + 1309, G210 + 1318, and G210 + 1319, which are known to be prone to rockfall hazards, as shown in Fig. 18. These deployments aim to monitor and prevent potential rockfall incidents, ensuring safer road conditions for travelers and mitigating risks associated with such natural disasters.

Discussion

This study presents a rockfall detection system (YOLOv8-GCB) based on embedded technology and an improved YOLOv8 algorithm, aimed at addressing the technical challenges in detecting rockfall hazards on mountainous roads. The research focuses on four key improvements to the YOLOv8-GCB algorithm, each targeting critical technical issues in existing rockfall detection systems. These improvements offer effective solutions, significantly enhancing the system’s detection performance and adaptability.

(1) The integration of the Deeplabv3+ road segmentation module can prioritize related road areas, thereby enabling the detection of only road areas that affects road safety. (2) Replacing standard convolutional units with Ghost convolutions can reduce computational load, making the algorithm more suitable for embedded devices with limited processing capabilities. (3) The CPCA attention mechanism is integrated into the backend of the YOLOv8 backbone network to enhance its feature extraction capability for targets with diverse shapes, thereby significantly improving the accuracy of rockfall detection. (4) Finally, the skip connections and weighted fusion strategies in the feature fusion network enhance the multi-scale flexible detection capabilities, enabling the algorithm to more effectively detect small rockfall targets.

Despite these advancements, certain challenges remain. The limited size and diversity of the dataset used for model training constrain the system’s performance under extreme weather conditions, such as heavy rain or fog. Furthermore, while the current deployment has proven successful on the G210 mountainous road, it requires further validation across diverse geographic and environmental settings to ensure its generalizability. Addressing these limitations will not only enhance the system’s robustness but also broaden its potential applications.

Conclusion

This study proposes an innovative rockfall detection system designed to overcome the unique challenges of mountainous highway environments. By leveraging an embedded framework and introducing a series of lightweight yet effective enhancements to the Yolov8 algorithm, the system achieves notable improvements in detection accuracy, inference speed, and practical applicability. The successful deployment on the G210 National Highway underscores its potential for real-world implementation, offering a reliable solution for intelligent rockfall monitoring. However, the current system is constrained by the limited scale and diversity of its training dataset, which impacts performance under extreme weather conditions. Future research will focus on incorporating large-scale, all-weather datasets from real-world engineering scenarios to refine and optimize the detection algorithm. These efforts aim to further enhance the system’s reliability and adaptability, ensuring its practical value in various environmental contexts and contributing to safer and more intelligent highway management solutions.

Data availability

Research data can be obtained by contacting us at pengpeng@sust.edu.cn.

References

Wang, X., Liu, H., Wang, R., Wang, Y. & Tu, X. The approach of rock collapse (rockfall) identification and prediction for power transmission and transforma-tion project in mountain area. J. Eng. Geol. 26(1), 172–178 (2018).

Dong, W. et al. Analysis of three-dimensional movement characteristics of rockfall: A case study at a railway tunnel entrance in the southwestern mountainous area, China. J. Geomechan. 27(1), 96–104 (2021).

Casagli, N. et al. Landslide detection, monitoring and prediction with remote-sensing techniques. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4(1), 51–64 (2023).

Schneider, M. et al. Rockfall monitoring with a Doppler radar on an active rockslide complex in Brienz/Brinzauls (Switzerland). Nat. Hazard. 23(11), 3337–3354 (2023).

Farmakis, I. et al. Rockfall detection using LiDAR and deep learning. Eng. Geol. 309, 106836 (2022).

Arosio, D. et al. Towards rockfall forecasting through observing deformations and listening to microseismic emissions. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 9(4), 1119–1131 (2009).

Ulivieri, G. et al. On the use of acoustic records for the automatic detection and early warning of rockfalls. Austr. Centre Geomecha.: Perth, Austr. 7, 45–56 (2020).

Ullo, S. L. et al. A new mask R-CNN-based method for improved landslide detection. IEEE J. Select. Topics Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 14, 3799–3810 (2021).

Fantini, A., Fiorucci, M. & Martino, S. Rock falls impacting railway tracks: detection analysis through an artificial intelligence camera prototype. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 11, 1–10 (2017).

Cheng, L. et al. Real-time discriminative background subtraction. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 20(5), 1401–1414 (2010).

Mohan, A. et al. Review on remote sensing methods for landslide detection using machine and deep learning. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 32(7), e3998 (2021).

Redmon, J., Divvala, S. & Girshick, R. et al. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 779–788 (2016).

Liu, W., Anguelov, D. & Erhan, D., et al. Ssd: Single shot multibox detector. in Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 11–14, 2016, Proceedings, Part I 14 21–37 (Springer International Publishing, 2016)

Rolet, P., Sebag, M. & Teytaud, O. Integrated recognition, localization and detection using convolutional networks. in Proceedings of the ECML Conference 1255–1263 (2012).

Ale, L., Zhang, N. & Li, L. Road damage detection using RetinaNet. in 2018 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data) 5197–5200 (IEEE, 2018).

Girshick, R., Donahue, J. & Darrell, T., et al. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 580–587 (2014).

Girshick R. Fast r-cnn. in Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision 1440–1448 (2015).

Ren, S. et al. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans. Patt. Anal. Mach. Intell. 39(6), 1137–1149 (2016).

He, K., Gkioxari, G. & Dollár, P., et al. Mask r-cnn. in Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision 2961–2969 (2017).

Zheng Yuanpan, Xu. & Boyang, W. Z. Improved YOLOv5 smoke detection model. Comput. Eng. Appl. 59(7), 214–221 (2023).

Xiang, Y., Huabin, W. & Minggang, D. Improved YOLOv5’s traffic sign detection algorithm. Comput. Eng. Appl. 59(13), 194–204 (2023).

Ken, C. et al. Rockfall detection method based on improved YOLOX. Comput. Measurement Control 31(11), 13–59 (2023).

Baheti, B. et al. Semantic scene segmentation in unstructured environment with modified DeepLabV3+. Patt. Recognit. Lett. 138, 223–229 (2020).

Han, K., Wang, Y. & Tian, Q., et al. Ghostnet: More features from cheap operations. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 1580–1589 (2020).

Niu, Z., Zhong, G. & Yu, H. A review on the attention mechanism of deep learning. Neurocomputing 452, 48–62 (2021).

Tan, M., Pang, R. & Le, Q. V. Efficientdet: Scalable and efficient object detection. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 10781–10790 (2020).

Xiao, B., Nguyen, M. & Yan, W. Q. Fruit ripeness identification using YOLOv8 model. Multimed. Tools Appl. 83(9), 28039–28056 (2023).

Wang, C. Y., Bochkovskiy, A. & Liao, H. Y. M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 7464–7475 (2023).

Bist, R. B. et al. A novel YOLOv6 object detector for monitoring piling behavior of cage-free laying hens. AgriEngineering 5(2), 905–923 (2023).

Wu, T. H., Wang, T. W. & Liu, Y. Q. Real-time vehicle and distance detection based on improved yolo v5 network. in 2021 3rd World Symposium on Artificial Intelligence (WSAI) 24–28 (IEEE, 2021)

Zhang, Y. et al. Road segmentation for all-day outdoor robot navigation. Neurocomputing 314, 316–325 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by [National Key Research and Development Program of China] grant number [2022YFD2100600], [Natural Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province] grant number [2024JC-YBQN-0400].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Peng Peng designed the study; LangChao Gao conceived the simulation and conducted the experiment; JiaChun Li analyzed the simulation results; HongZhen Zhang. drafted the paper; Peng Peng organized the manuscript; all authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, P., Gao, L., Li, J. et al. Optimized YOLOv8 framework for intelligent rockfall detection on mountain roads. Sci Rep 15, 14007 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94910-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94910-5