Abstract

We propose a detailed approach for modeling the C–V characteristic of complex heterostructure-based devices, investigating the case of UV-C LEDs. The study is based on combined experimental measurements and TCAD simulations, and explores: i) the impact of defects at critical interfaces on the apparent charge profile; ii) the dependence of the C–V characteristic on the efficiency of carrier injection toward the QWs; iii) the impact of a non-ideal partially-rectifying p-contact on the C–V curves. By accounting for these processes and non-idealities, we were able to achieve a good reproduction of the experimental C–V characteristic and of the corresponding apparent charge profile. The result presented in this paper provide relevant information for the investigation of specific device features, based on simple electrical characterizations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Device modelling is an important tool for the design and characterization of electronic and optoelectronic devices. This is particularly relevant for new and emerging technologies (such as those based on compound semiconductors), and for complex structures (such as light-emitting diodes and laser diodes), whose efficiency strongly depends on the design and properties of the complex heterostructures on which they are based. In recent papers1,2,3,4 we demonstrated the importance of modelling for identifying and reproducing the physical processes responsible for the degradation of optoelectronic components based on III-N semiconductors5,6.

A technique that is commonly adopted by the semiconductor industry for the study of device properties is capacitance–voltage (C–V) characterization. This technique is particularly helpful for the determination of the apparent charge in semiconductor layers7,8; it has been developed for measuring the depletion capacitance of an abrupt asymmetrical p–n junction and thus calculating the related doping levels.

Wide bandgap semiconductors (such as III-N materials) are extremely useful for the fabrication of optoelectronic components. However, the C–V characteristics of the devices cannot be easily analysed, due to several factors: (i) the presence of polarization and interface charges9; (ii) the high ionization energy of the dopants, resulting in bilateral depletion of the junction; (iii) the limits of the abrupt depletion approximation10; (iv) the non-uniformity of semiconductor doping11; (v) in the case of LED devices, the presence of heterojunctions and different interfaces also contributes to the complexity of the problem. For these reasons, the capacitance–voltage profiles cannot be directly interpreted (as done for conventional silicon devices12) for a prompt assessment of material/device properties, and a numerical approach needs to be undertaken.

The aim of this paper is to present a methodology to model the capacitance characteristic of a complex heterostructure-based device based on wide-bandgap semiconductor, namely a UV-C LED. By the use of numerical simulations, the electrical properties of the structure are reproduced and the related C–V curves are modelled, with the final aim of extracting the apparent charge profile (ACP) of the device. Furthermore, this analysis provides useful information on the distribution of the carriers in the active region13, on the doping profile, on the presence of charged defects at the interfaces, and on non-idealities at the p-contact.

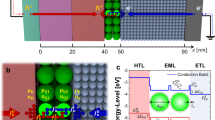

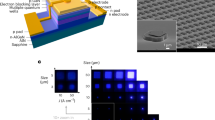

Experimental details

For the study we considered an AlGaN-based LED on-wafer emitting in the UV-C range. Consistently with previous reports14,15,16, the device has three quantum wells (QWs); for investigating the impact of alloy composition and polarization charges, quantum wells with different Al content are used, two emitting at 233 nm and one emitting at 250 nm \(.\) The device is grown by metalorganic vapor phase epitaxy (MOVPE) on (0001) oriented high temperature annealed (HTA) epitaxially laterally grown (ELO) AlN/sapphire substrates17. Above the AlN/sapphire template, the epitaxial stack continues with a 25 nm thick Al0.87Ga0.13N transition layer, over which a 100 nm thick Si-doped Al0.87Ga0.13N buffer is grown. This layer is followed by a 2.2 µm thick Si-doped Al0.87Ga0.13N contact layer featuring a doping density \({N}_{D}=4 \cdot {10}^{18} c{m}^{-3}\). On top of the contact layer, a 40 nm thick Si-doped Al0.87Ga0.13N “first barrier” is grown (\({N}_{D}=6 \cdot {10}^{18} c{m}^{-3}\)), followed by a first 1.4 nm thick Al0.57Ga0.43N quantum well, emitting at 250 nm. The structure proceeds with a series of two 5 nm thick Si-doped Al0.835Ga0.165N quantum barriers with a dopant concentration equal to \(3 \cdot {10}^{18} c{m}^{-3}\) followed by a 1.4 nm thick Al0.72Ga0.28N quantum well, emitting at 233 nm, and an undoped 5 nm thick Al0.835Ga0.165N “last barrier”. A 6 nm thick undoped AlN electron blocking layer (EBL) separates the p-region from the active regions. The p-side consists of two series of over-doped super lattice layers (SLSP) consisting of 14 pairs of 0.9/0.9 nm Al0.7Ga0.3N/Al0.8Ga0.2N layers and 15 pairs of 1.4/1.4 nm Al0.37Ga0.63N/Al0.2Ga0.8N layers. Both the SLSPs are heavily p-doped with a nominal Mg concentration of \(2 \cdot {10}^{19} c{m}^{-3}.\) The purpose of the SLSP is to lower the activation energy of magnesium favoring the hole injection toward the active region and at the same time to maximize the effective barrier height for the electrons, thus reducing current leakage through the structure18. The structure ends with a p-doped 50 nm thick GaN layer featuring a nominal Mg concentration of \(7.5 \cdot {10}^{19} c{m}^{-3}\). Finally, the LEDs were processed by standard micro-fabrication techniques using palladium p-contacts and V/Al based n-contacts19. Figure 1 shows the simplified device structure, as well as the band diagram at equilibrium, calculated through the numerical simulations discussed in the following paragraph, in which the different device layers can be seen.

A preliminary C–V measurement was performed by means of a Keysight E4980A LCR meter. During this measurement, an AC voltage perturbation of amplitude \({V}_{ac}\) and frequency \({f}_{ac}\) is superimposed to the DC bias voltage provided to the sample. The time-dependent device current response is then measured in order to obtain the complex value of the device impedance. This information can be used to estimate the junction (and diffusion) capacitance of the LED as a function of the DC bias. In this case, the amplitude of the AC signal was set to 50 mV, whereas the frequency was set to 1 MHz: this value is sufficiently high to probe the response to \({V}_{ac}\) only of the shallower traps and of the free carriers9,20, while avoiding interferences from the large electrical noise sources active at lower frequencies, i.e. below some hundreds Hz. In the ideal case, assuming a unilateral Schottky-like depletion, the local charge density at the edge of the depletion region \({N}_{A}\left(w\right)\) at a specific DC bias voltage can be calculated with the following formula:

where w is width of the depletion region, which depends on the bias level, A is the junction area, \({\varepsilon }_{r}\) is the semiconductor relative permittivity, \({\varepsilon }_{0}\) the absolute dielectric permittivity of vacuum, q is the electron charge and C the measured capacitance. In a unilateral junction, the dominant capacitance response originates from the movement of the edge of the depletion region as a consequence of the small AC signal applied. Since the doping concentration of the p-side of the devices under test (DUTs) is greater than the free charge within the active region, at least at moderate voltages, one can assume an asymmetric depletion, extending from the SLSP/EBL interface toward the active region. This can be clearly observed in Fig. 1b, which shows the band bending of the p–n junction: the presence of a high electric field affects the semiconductor layers extending from the EBL to the first barrier.

Figure 2 reports the apparent charge profile as function of LED voltage obtained by the experimental measurement (black line). One can notice three different peaks in the charge profile. The first between 0 and 2 V, the second between 2 and 3 V and the third between 3 and 3.5 V. As reported in the literature13,21,22,23,24,25,26 these peaks can be associated to the three QWs, where the majority of carriers accumulates, whereas the “valleys” can be associated to the quantum barriers, which are depleted of free carriers. At equilibrium, it is possible to observe that the edge of the space charge region (SCR) lies within the first barrier and that the value of the extrapolated apparent charge profile almost matches the nominal doping within this device layer.

Simulation approach

In order to reproduce the capacitance–voltage characteristics of the device, the structure was implemented and simulated by means of the TCAD Sentaurus suite, from Synopsys Inc.27. The doping of the different layers was modeled by placing donor or acceptor traps, respectively Si and Mg, at their typical thermal activation energies and with the nominal chemical concentrations set during device growth. Specifically, silicon was placed at \({E}_{C}-24 meV\) for n-doped AlGaN layers, whereas magnesium was placed at \({E}_{V}+150 meV\) and \({E}_{V}+250 meV\) for the p-GaN layer and the SLSPs, respectively28,29,30. All the main recombination processes were activated: the radiative recombination coefficient was set to \(5\times {10}^{-11}{cm}^{3}{s}^{-1}\)31, whereas an Auger–Meitner coefficient of \(5\times {10}^{-31}{cm}^{6}{s}^{-1}\) was selected, according to the values reported in32,33. SRH recombination, instead, was implemented by including midgap levels within the active region with a density of \(1\times {10}^{16}{cm}^{-3}\), according to the experimental results derived from similar samples2. Carrier distributions were computed by adopting the density gradient quantization model34,35. Finally, in order to favor the injection of carriers toward the QWs, direct tunneling was implemented in the first barrier region adjacent to the first QW as indicated by the magenta arrow in Fig. 1b and through the barriers of the SPSLs, adopting the model based on the WKB approximation6,36.

The C–V simulations were carried out adopting the very same stimulus parameters used for the experimental measurements: a voltage sweep was performed between -6 V and 5 V in quasi-stationary conditions, and an AC signal at 1 MHz was applied. Figure 2 reports the apparent charge profile (red curve) computed starting from the simulated C–V. It can be noticed that above 4 V the simulated profile already shows a good matching with the experimental one, whereas at lower voltages the profile appears shifted with respect to the measured data. In fact, this simulation was performed by setting only the nominal doping densities targeted by the growth recipe. Potential deviation from the target value by compensation or deactivation (e.g. passivation by H) is not considered.

In the next paragraphs we analyze and model the different non-idealities and mechanisms that impact on the C–V characteristic of the DUTs. In particular, we evaluate the effect of (i) a non-ideal p-contact, which features a voltage-dependent capacitance contribution in series to the junction capacitance; (ii) the presence of charged defects at specific heterointerfaces within the active region; and iii), the role of the intraband tunneling within the QWs, which strongly influences the density of free carriers injected in the active region and thus the apparent charge profile.

Modeling of the p-contact capacitance

As previously mentioned, a critical aspect that needs to be taken in account is the influence of the Schottky nature of the contact on p-GaN on the overall capacitance of the device37,38. If we considered that the measured capacitance is only associated to the p–n junction, thus assuming an ideal p-contact with a negligible voltage drop, the C–V characteristic of the device would reflect the sole junction capacitance. In this case, the simulated curve would be very different from the experimental one, showing values almost one order of magnitude higher at high forward voltages. This is evidenced by Fig. 3a, which reports the comparison between the simulated C–V characteristic including a fully ohmic p-contact (black continuous curve) and the experimental characteristic (black dashed curve): it is clear that the real device is far from this ideality condition. Therefore, it is evident that another bias-dependent series capacitance component impacts on the overall capacitance, causing its reduction. As formerly stated, this kind of contribution can be due to a non-ideal contact at the p-side. For instance, if the effective doping level in the p-GaN layer was the nominal chemical concentration incorporated during device growth (in this case \(7.5\times {10}^{19}\) \({cm}^{-3}\)), the depletion region at the contact would be very thin, thus contributing with a very high series capacitance to the overall device impedance, which would then closely resemble the junction capacitance. However, it is well known that Mg dopants are not completely activated and ionized in GaN39. This generates a widening of the depletion region located at the p-contact, which decreases the related space-charge capacitance value, ultimately becoming comparable with the junction capacitance. To account for this phenomenon, the p-contact in the simulations was modelled as a Schottky contact consisting of a metal with the work-function of Pd (5.1 eV) and of a heavily p-doped GaN region adjacent to the contact. This region forms a potential barrier through which the holes are injected in the device by direct tunneling (WKB approximation)6,36. Figure 3b shows the band diagram at the p-contact. For simplicity, the GaN layer has been divided into two regions, a 10 nm wide region adjacent to the p-contact, approximately corresponding to the width of the potential barrier in which the doping density was kept high, and a second one 40 nm wide, where the doping concentration was varied from \(5\times {10}^{18}\) \({cm}^{-3}\) to \(5\times {10}^{17}\) cm-3, to emulate the incomplete dopant activation and ionization. It can be noticed that if the active doping density is reduced, down to a certain extent (about \(5\times {10}^{17}\) \({cm}^{-3}\)), the depletion region at the p-contact extends until the SLSP. Figure 3a reports also the simulated C–V curves as a function of the doping density in the second GaN region, which well match the experimental data for active doping levels close to \(5\times {10}^{17}\) \({cm}^{-3}\) in the p-GaN layer. Besides, it is possible to observe that the variations in the C–V characteristics are comparable with the extension of the space charge region in the p-doped GaN layer. Once the depletion region reaches the SLSP region, its extension saturates and, as a consequence, also the effects of this SCR on the overall capacitance.

Interface defects

The preliminary simulation presented in Fig. 2 does not consider a fundamental parameter to which the charge profile is very sensitive, i.e. the presence of interface defects. Due to the many heterointerfaces present within the DUTs, charged defects may be incorporated, leading to possible worsening of device performance and to variations in the estimated apparent charge profile40,41. If such defects exhibit a donor-like behavior42,43, they increase the voltage required to displace the edge of the SCR towards the n-side, effectively shifting the apparent charge profile at lower voltages.

Figure 4 evidences the impact of interface defects, placed in correspondence of different interfaces of the active region, on free charge distribution. This is achieved by performing a parametric simulation as a function of trap density, by varying the net charge from \(-1\times {10}^{12}\) \({cm}^{-2}\) to \(1\times {10}^{12}\) \({cm}^{-2}\). The simulation with the density of \(1\times {10}^{10}\) \({cm}^{-2}\) is equivalent the curve without defects, since this very low concentration has no significant effects in the profile. In Fig. 4c one can observe the behavior of the charge profile placement at the QW3/LB interface at an increasing density of defects. This variation leaves unchanged the apparent charge profile until the last barrier (i.e. above 4 V) and generates a leftward-shift of the ACP corresponding to the layers located below this interface. Thus, the peaks corresponding to the QWs become detectable at lower measuring voltages. Furthermore, the increase in the positive fixed charge at the QW3/LB interface causes an increase in the carrier density within QW3. As a consequence, a higher voltage variation is required to sweep through this region, as clearly observable between 3 and 4 V in the Fig. 4c. A similar reasoning can be followed for fixed density placement at other interfaces. For example, Fig. 4d considers the scenario involving the QW2/QB2 interface: in this case it is worth noticing that all the layers above this interface, i.e. toward the p-side, are not affected by this variation, instead the shift concerns only QW1 and QW2. Finally, in Fig. 4e and f we analyze the interfaces related to QW1. Considering the QW1/QB1 interface, it is possible to notice that the variation in the trap density generates a slight shift in the charge peak of the first QW and a more evident shift of the “valley” corresponding to the LB/QW1 interface. Instead, defects placed at the FB/QW1 interface generate a marked shift of the same interface and an increase in the electron density within the QW, without altering the “position” in the apparent profile of the QW1 peak.

Band diagram at equilibrium with the investigated interfaces highlighted by a dashed green line (a); Comparison between the experimental apparent charge profile and the simulated ones with and without interface defects (b); variations in the apparent charge profile extracted from the simulated C–V as a function of the defect densities placed at the interface between the last barrier and QW3 (c), between QW2/QB2 (d), between QW1/QB1 (e) and between the first barrier and QW1 (f).

Looking now at Fig. 4b, which reports the simulated profile without additional interface charges (red curve), it is clear that, to match the experimental data, the three QW peaks have to shift toward lower voltages. This effect can be achieved by including positively charged defects at the heterointerfaces. In particular, by placing positive charge at QW3/LB interface with a density of \(1\times {10}^{12}\) \({cm}^{-2}\), the profile remains unchanged above 4 V, where there is already a good matching, while shifts toward lower voltages for the underlying layers, as shown by the blue curve. This variation is sufficient to achieve a good matching for the QW3 peak, but the peaks corresponding to QW1 and QW2 are not aligned with the experimental data. In this case, a further correction was applied by placing a similar defect population at the QW2/QB2 interface, which yields the reported green curve. At this point we successfully achieved a good matching with the experimental data, with only a slightly overestimated density of the free carriers in the QWs, with values for defect interface densities typically associated with AlGaN interfaces40.

Finally, we need to stress that the solution obtained is not unique. As a matter of fact, if a lower density of defects is placed at both the interfaces of a QW to shift the related profile, a similar effect can be obtained by placing all the charge at the interface toward the p-side. Thus, the proposed methodology allows to identify that the issue is a charge accumulation process and the layer affected by it, but not the precise interface to which the defects belong. Despite this consideration, the simulations still provide a significant grade of accuracy for non-invasive electrical device investigation.

Effect of intraband tunneling within the active region

As previously mentioned in the “Simulation approach” section, in order to reasonably simulate the injection of electrons towards the active region, direct tunneling through the last 10 nm of the first barrier adjacent to the QW1 (see magenta arrow in the band diagram in Fig. 1) was implemented, by adopting the WKB tunneling probability approximation6,36. The main parameter of this model is represented by the relative tunneling mass (\({m}_{t})\), that can be considered as a fitting parameter. This procedure is necessary to reach a good matching with the experimental data. In fact, Fig. 5a reports a parametric simulation of the apparent charge profile as a function of \({m}_{t,FB}\). It is possible to notice that a lower tunneling mass corresponds to a higher carrier density injected in the QW, as expected. In absence of this process, the profile would be completely different from the measured data, since it would not feature the “valley” due to the FB/QW1 interface. Also looking at the C–V characteristics simulated in Fig. 5b it is clear that the first “wave” that corresponds to the first QW would not be reproduced. Tuning the relative mass tunneling through this barrier, a good matching was reached setting it at 0.3, close to the values reported in literature for GaN and AlGaN44. Similar effects could be obtained with slight variations in the doping density of the first barrier, in particular an increase in the doping concentration leads to an enhancement in the injection of majority carriers and vice-versa.

Matching of the C–V characteristic

Based on the considerations derived in the previous paragraphs and on a careful tuning of the simulation parameters, it was possible to reproduce the experimental C–V, as show in Fig. 6. By using the parameters reported in Table 1, a quite good matching was achieved across all the relevant voltage ranges, i.e. voltage ranges for which the measured small-signal capacitance is not affected by measurement artifacts due to hardware limitations.

Figure 7a reports a comparison between the apparent charge profile computed from the simulated C–V and the experimental data, which shows a very good agreement, in particular in terms of carrier density peaks, except for a slightly over-estimated carrier density in QW3. Figure 7b reports the simulated electron density at different voltages (hole concentration was not reported since the related density is negligible, with concentrations under \(1\times {10}^{10}\) \({cm}^{-3}\)) below the turn-on voltage Following the carrier trend as a function of the voltage, it is possible to assess the correct association of the peaks of the charge profile to the QWs. Specifically, if we consider the curve at 1.5 V, one can observe that QW1 is already full of charge, whereas QW2 is relatively empty. This means that in this bias condition the depletion region is extended until the first QW, and that the peak in the charge profile at 1.5 V corresponds to this QW. A similar reasoning can be followed by looking at the curve at 2.5 V, which exhibits high electron densities until QW2, and at 3.5 V, where the depletion region extends until QW3. Above 4 V, the carriers accumulate at the interface between the EBL and the last barrier, thus the last peak observable at 5 V corresponds to this interface. Although the apparent charge profile provides only an estimation of the charge distribution at different voltages, it is possible to exploit it to extrapolate qualitative information about the carrier distribution within the QWs. In this specific case, as confirmed by the band diagram in Fig. 7b, the first QW shows a higher carrier accumulation with respect the other QWs, also due to its lower energy gap and higher carrier confinement. On the other hand, the second QW exhibits the lowest electron density, making it difficult to discriminate from the experimental profile data; finally, the last QW shows a greater carrier accumulation with respect to QW2, which allows to make it identifiable also from the measurement data.

Conclusions

To summarize, in this work we developed a simulation framework to model the capacitance–voltage characteristics of complex heterostructure devices, namely AlGaN-based UV-C LEDs. The main issues and non-idealities were considered. The simulations showed that: (i) a non-ideal p-contact influences the overall C–V characteristic of the device, especially for high forward voltages; (ii) the C–V curves are sensitive to the presence of shallow or charged interface defects; such defects can affect the apparent charge profile in different ways, depending on their physical location, varying the voltage required to sweep through the different layers of the active region; (iii) we showed that the injection of electrons toward the active region, favored by the presence of tunneling through the first barrier, has detectable impact on the C–V characteristics;

Based on these findings, we were able to reproduce with good accuracy the C–V characteristics of the devices under investigation, as well as the related apparent charge profile. The proposed procedure ultimately allowed to verify the correct interpretation of the experimental C–V profiles, to discriminate the device layers that are being probed by the electrical characterization, and to evaluate the possible presence of non-idealities at specific locations, such as hetero-interfaces or contacts. The approach proposed in this work ultimately provides a useful tool for the characterization of specific non-idealities present in electronic and optoelectronic devices, based on easy-to-attain C–V measurement data.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Roccato, N. et al. Modeling the electrical characteristics of InGaN/GaN LED structures based on experimentally-measured defect characteristics. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 54(42), 425105. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6463/AC16FD (2021).

Roccato, N. et al. Modeling the electrical degradation of AlGaN-based UV-C LEDs by combined deep-level optical spectroscopy and TCAD simulations. Appl. Phys. Lett. 122(16), 161105. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0144721/2884739 (2023).

Mandurrino, M. et al. Physics-based modeling and experimental implications of trap-assisted tunneling in InGaN/GaN light-emitting diodes. Phys. Status Solidi 212(5), 947–953. https://doi.org/10.1002/pssa.201431743 (2015).

Nicoletto, M. et al. TCAD modeling and simulation of dark current-voltage characteristics in high-periodicity InGaN/GaN multiple-quantum-wells (MQWs) solar cells. IEEE J. Photovolt. 14(3), 450–458. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPHOTOV.2024.3366710 (2024).

Roccato, N. et al. Modeling the electrical characteristic of InGaN/GaN blue-violet LED structure under electrical stress. Microelectron. Reliab. 138, 114724. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MICROREL.2022.114724 (2022).

Roccato, N. et al. Modeling of the electrical characteristics and degradation mechanisms of UV-C LEDs. IEEE Photon. J. 16(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPHOT.2024.3355553 (2024).

Sozzi, G. et al. A numerical study of the use of C–V characteristics to extract the doping density of CIGS absorbers. Conf. Rec. IEEE Photovolt. Spec. Conf. 2016, 2283–2288. https://doi.org/10.1109/PVSC.2016.7750043 (2016).

Schroder, D. K. Semiconductor Material and Device Characterization 3rd edn, 1–779 (Wiley, 2005). https://doi.org/10.1002/0471749095.

Cwil, M., Igalson, M., Zabierowski, P. & Siebentritt, S. Charge and doping distributions by capacitance profiling in Cu(In, Ga)Se2 solar cells. J. Appl. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2884708/284423 (2008).

Johnson, W. C., Johnson, W. C. & Panousis, P. T. The influence of debye length on the C–V measurement of doping profiles. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 18(10), 965–973. https://doi.org/10.1109/T-ED.1971.17311 (1971).

Wu, C. P., Douglas, E. C. & Mueller, C. W. Limitations of the CV technique for lon-implanted profiles. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 22(6), 319–329. https://doi.org/10.1109/T-ED.1975.18130 (1975).

Peiner, E., Schlachetzki, A. & Krüger, D. Doping profile analysis in Si by electrochemical capacitance-voltage measurements. J. Electrochem. Soc. 142(2), 576–580. https://doi.org/10.1149/1.2044101/XML (1995).

Arias, J. et al. Carrier profile for In 0.35 Ga 0.65 As/GaAs multiquantum well lasers from capacitance-voltage measurements. Appl. Phys. Lett 68, 1138–1140. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.115738 (1996).

Schilling, M. et al. Light extraction and external quantum efficiency of 235 nm far–ultraviolet-C light-emitting diodes on single-crystal AlN substrates. Phys. Status Solidi https://doi.org/10.1002/PSSA.202400812 (2024).

Hopfner, J. et al. Unraveling carrier distribution in far-UVC LEDs by temperature-dependent electroluminescence measurements. Appl. Phys. Lett. 125(7), 71109. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0223284/3308123 (2024).

Romer, F. et al. Carrier transport in a deep ultraviolet mixed quantum well light emitting diode. IEEE Photon. J. 16(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPHOT.2024.3351965 (2024).

Susilo, N. et al. Improved performance of UVC-LEDs by combination of high-temperature annealing and epitaxially laterally overgrown AlN/sapphire. Photon. Res. https://doi.org/10.1364/PRJ.385275 (2020).

Muhin, A., Guttmann, M., Wernicke, T. & Kneissl, M. AlGaN multi-quantum barriers for electron blocking in group III-nitride devices. Proc Int. Conf. Numer. Simul. Optoelectron. Devices NUSOD 2018, 21–22. https://doi.org/10.1109/NUSOD.2018.8570261 (2018).

Sulmoni, L. et al. Electrical properties and microstructure formation of V/Al-based n-contacts on high Al mole fraction n-AlGaN layers. Photonics Res. 8(8), 1381–1387. https://doi.org/10.1364/PRJ.391075 (2020).

Cristea, M. J. Capacitance-voltage Profiling Techniques for Characterization of Semiconductor Materials and Devices. SSRN Electron. J. https://doi.org/10.2139/SSRN.3433675 (2019).

Armstrong, A., Henry, T. A., Koleske, D. D., Crawford, M. H. & Lee, S. R. Quantitative and depth-resolved deep level defect distributions in InGaN/GaN light emitting diodes. Opt. Express 20(S6), A812. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.20.00a812 (2012).

Moon, C. R., Choe, B. D., Kwon, S. D. & Lim, H. Spatial resolution of capacitance-voltage profiles in quantum well structures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 72(10), 1196–1198. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.121011 (1998).

Moon, C. R. & Lim, H. Influence of quantum-well structural parameters on capacitance–voltage characteristics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 74(20), 2987–2989. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.123988 (1999).

Petrovskaya, A. N. & Zubkov, V. I. Investigating the charge relaxation in semiconductor heterostructures with quantum wells by means of admittance spectroscopy. Bull. Russ. Acad. Sci. Phys. 75(10), 1416–1422. https://doi.org/10.3103/S1062873811100273/METRICS (2011).

Moon, C. R., Choe, B. D., Kwon, S. D. & Lim, H. Electron distribution and capacitance-voltage profiles of multiple quantum well structure from self-consistent simulations. Appl. Phys. Lett. 70(22), 2987–2989. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.118765 (1997).

Tschirner, B. M., Morier-Genoud, F., Martin, D. & Reinhart, F. K. Capacitance-voltage profiling of quantum well structures. J. Appl. Phys. 79(9), 7005–7013. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.361466 (1996).

Synopsys and Inc. SentaurusTM Device User Guide. http://www.synopsys.com/Company/Pages/Trademarks.aspx (2021).

Zhao, C. Z., Wei, T., Chen, L. Y., Wang, S. S. & Wang, J. The activation energy for Mg acceptor in AlxGa1-xN alloys in the whole composition range. Superlattices Microstruct. 109, 758–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spmi.2017.06.006 (2017).

Nakano, Y. & Jimbo, T. Electrical properties of acceptor levels in Mg-Doped GaN. Phys. Status Solidi https://doi.org/10.1002/pssc.200390082 (2003).

Silvestri, L., Dunn, K., Prawer, S. & Ladouceur, F. Hybrid functional study of Si and O donors in wurtzite AlN. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99(12), 122109. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3641861 (2011).

Qian, Z. et al. Analysis of the efficiency improvement of 273 nm AlGaN UV-C micro-LEDs. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 55(19), 195104. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6463/AC4E33 (2022).

Ni, R. et al. Light extraction and auger recombination in AlGaN-based ultraviolet light-emitting diodes. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 32(16), 971–974. https://doi.org/10.1109/LPT.2020.3006863 (2020).

Pant, N. et al. Carrier confinement and alloy disorder exacerbate Auger-Meitner recombination in AlGaN ultraviolet light-emitting diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 125(2), 21109. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0208840/3303112 (2024).

Wettstein, A., Schenk, A. & Fichtner, W. Quantum device-simulation with the density-gradient model on unstructured grids. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 48(2), 279–284. https://doi.org/10.1109/16.902727 (2001).

Ancona, M. G. & Iafrate, G. J. Quantum correction to the equation of state of an electron gas in a semiconductor. Phys. Rev. B 39(13), 9536. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.39.9536 (1989).

Piva, F. et al. Investigation of degradation dynamics of 265 nm LEDs assisted by EL measurements and numerical simulations. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 39(7), 075025. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6641/AD54E9 (2024).

Wahid, S., Chowdhury, N., Alam, M. K. & Palacios, T. Barrier heights and Fermi level pinning in metal contacts on p-type GaN. Appl. Phys. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0010699/38147 (2020).

Roccaforte, F. et al. Critical issues for interfaces to p-type SiC and GaN in power devices. Appl. Surf. Sci. 258(21), 8324–8333. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.APSUSC.2012.03.165 (2012).

Smorchkova, I. P. et al. Mg doping of GaN layers grown by plasma-assisted molecular-beam epitaxy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 76(6), 718–720. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.125872 (2000).

Gao, Y., Sun, D., Jiang, X. & Zhao, J. Ab initio analytic calculation of point defects in AlGaN/GaN heterointerfaces. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 33(3), 035002. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-648X/ABBDBB (2020).

Roccato, N. et al. Investigation and modeling of the role of interface defects in the optical degradation of InGaN/GaN LEDs. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6463/AD7039 (2024).

Meneghini, M. et al. Degradation of AlGaN/GaN Schottky diodes on silicon: Role of defects at the AlGaN/GaN interface. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102(16), 163501. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4802011/311540 (2013).

Matys, M., Stoklas, R., Blaho, M. & Adamowicz, B. Origin of positive fixed charge at insulator/AlGaN interfaces and its control by AlGaN composition. Appl. Phys. Lett. 110(24), 6. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4986482/235882 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. Calculating the effect of AlGaN dielectric layers in a polarization tunnel junction on the performance of AlGaN-based deep-ultraviolet light-emitting diodes. Nanomaterials 11(12), 3328. https://doi.org/10.3390/NANO11123328 (2021).

Acknowledgements

Project funded under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4, Component C2, Investment 1.1, by the European Union – NextGenerationEU. PRIN Project 20225YYLEP, CUP: C53D23000350006, "Empowering UV Led technologies for high-efficiency disinfection: from semiconductor-level research to SARs-Cov-2 inactivation" (D.D. 104—02/02/2022 Ministero dell’Università e della Ricerca). This manuscript reflects only the authors’ views and opinions and the Ministry cannot be considered responsible for them.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Nicola Roccato, Francesco Piva, Matteo Buffolo, Carlo De Santi, Nicola Trivellin, Gaudenzio Meneghesso, Enrico Zanoni and Matteo Meneghini wrote the manuscript text, prepared the figures, collaborated for the experimental analysis and followed the methodology. Nicola Roccato also implemented the simulation and sofware part supported by Matteo Buffolo, Francesco Piva, Carlo De Santi, Nicola Trivellin, Gaudenzio Meneghesso, Enrico Zanoni and Matteo Meneghini. Marcel Schilling, Anton Muhin, Jakob Höpfner, Martin Guttmann, Tim Wernicke and Michael Kneissl designed and grew the device and supported the experimetal analysis. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Roccato, N., Piva, F., Buffolo, M. et al. Modeling the capacitance–voltage characteristics of AlGaN-based UV-C LEDs. Sci Rep 15, 13483 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95015-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95015-9