Abstract

Brainstem tumors exert profound effects on cortical organization and functionality across the whole brain. However, the precise implications of changes in cortical thickness (CTh) for patient stratification and prognostic assessment remain unclear. Our study seeks to address these gaps and provide clearer insights into the distant impact of brainstem tumors. This study involved 124 pediatric patients with brainstem tumors and 849 healthy controls. Using CAT12 segmentation on 3D T1-weighted MRI scans and Gaussian process regression modeling, we established a normative CTh model from healthy data. CTh deviations of patients were quantified and clustered, revealing two distinct subtypes: Subtype 1 with extremely positive deviations and Subtype 2 with extremely negative deviations, correlating with better survival. Kaplan-Meier analysis confirmed significant survival differences between these subtypes. Additionally, a greater number of brain regions with positive CTh deviations was found to correlate with larger tumor volumes. These findings suggest that CTh deviation is a non-invasive imaging marker, facilitating patient subtyping and survival prediction. These insights equip clinicians to tailor treatment plans and establishes a valuable precision medical tool for clinical evaluation and monitoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Brainstem tumors are the most lethal and intractable neoplasms within the pediatric central nervous system accounting for 14.03% of all central nervous system tumors in children1. Approximately 20% of brainstem tumors are low-grade neoplasms focused in the midbrain, medulla, or dorsal pontine, while the remaining 80% are characterized by diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG)2,3,4. Previous studies on the heterogeneity of brainstem tumors have primarily focused on imaging characteristics and histological features5. Focal brainstem tumors grow slowly, causing symptoms through local compression, and allowing for good surgical outcomes and prognosis6. However, the DIPG typically leads to a rapid onset of symptoms and results in a poor prognosis due to the difficulties associated with surgical removal with a 5-year survival rate of less than 2%3. The unique anatomical location and diffuse nature of many brainstem tumors pose challenges in treatment, limiting surgical options and reducing the effectiveness of conventional therapies. As a result, reliable prognostic markers are essential for developing personalized clinical treatment strategies. Classifications based on pathology, growth pattern, location, and malignancy remain crucial in guiding treatment decisions and predicting prognosis7,8,9. However, clinical observations found that some DIPG patients had a good prognosis, indicating that the traditional classifications based on the tumor feature still has limitations10. Current research predominantly focuses on localized tumor characteristics, leaving the whole-brain burden induced by brainstem lesions poorly understood11. The brainstem’s unique position in global neural integration lacked.

Addressing this gap requires developing neuroimaging biomarkers capable of decoding heterogeneous whole-brain adaptations. The brainstem serves as a critical relay center facilitating bidirectional communication between supratentorial structures and spinal cord networks12. Pathological infiltration by neoplastic lesions has been observed to induce structural disorganization within this region, consequently compromising the integrity of ascending and descending neural pathways. Disruption of cortical signaling pathways may trigger dysfunction in regulatory circuits, driving neurodegeneration via circuit disconnection13. Furthermore, glioma cells infiltrate the brain along white matter tracts and extend their impact to cortical structures14,15. Neural injury demonstrates topographic specificity, with axonal pathology clustering near peritumoral degenerative and myelin breakdown predominating in remote white matter tracts16. This spatial hierarchy of injury manifests clinically as sensorimotor deficits when critical pathways like the corticospinal tract are compromised17. The brain initiates neuroplastic responses—a double-edged sword enabling either functional compensation via synaptic remodeling18 or maladaptive decompensation evidenced by cortical atrophy19. Cortical thickness (CTh) changes (thinning or thickening) may visually map these opposing outcomes.

Although the bidirectional plasticity paradigm has gained experimental support in stroke models20,21, its direct applicability to glioma-related remodeling remains contentious. Crucially, such structural alterations correlate with domain-specific cognitive decline, particularly in executive functioning22. Recent studies propose metaplasticity—the brain’s ability to modulate future synaptic plasticity based on prior activity—as a key mechanism regulating neuronal adaptation during glioma treatment23. Specifically, preoperative metaplastic states predict post-operative cognitive recovery, highlighting its clinical relevance. These findings underscore the need to investigate how brainstem tumors induce distant cortical disruptions, which should inform multimodal therapeutic strategies24. Building on these insights, clinical trials are now testing whether modulating metaplasticity through prehabilitation protocols can improve surgical outcomes in glioma patients25.

Brainstem tumors are highly prevalent in children, with potential age-dependent variations in biological behavior. Younger children, particularly infants, exhibit distinct symptom expression patterns and poorer overall survival compared to older children26. Traditional case-control studies often overlook age-related dynamic changes in neurodevelopment, as they rely on static group-level comparisons that fail to model nonlinear developmental trajectories. Normative modeling is a statistical or computational approach that aims to identify deviations of individual observations from a modeled normal data distribution within a population. Therefore, this study investigates whole-brain structural alterations in pediatric brainstem tumor patients through CTh analysis. We aim to identify subtype-specific CTh patterns as non-invasive biomarkers for patient stratification and evaluate the prognostic value of CTh deviations in predicting overall survival. An overview of the research workflow is shown in Fig. 1.

Flow chart of CTh heterogeneity analysis and subtype identification. (a) Acquisition and preprocessing of structural MRI (sMRI) data, including CTh segmentation, volume extraction of Regions of Interest (ROI), and data harmonization. (b) Establishment of a normative model using the Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) method, followed by the calculation of individualized CTh deviations for patients. (c) Application of individualized CTh deviations data to identify subtypes using spectral clustering, and the subsequent analysis of clinical differences among these subtypes.

Materials and methods

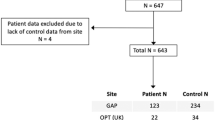

Participants

A cohort of 145 pediatric patients with brainstem tumors was studied at Beijing Tiantan Hospital from April 2020 to December 2023. The main inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) diagnosed with brainstem tumor without prior treatment; (ii) tumors confined to the brainstem; (iii) all patients have no psycho-neurological disorders and developmental disorders; (iv) all patients have no other systemic diseases. All participants underwent 3DT1 MRI. The primary endpoint was overall survival (OS), which was defined as the number of days from the initial pathological diagnosis to death (censored = 1) or the last date that they were known to be alive (censored = 0). Longitudinal follow-up assessments with sufficient duration for overall survival analysis were ultimately completed in a subset of 57 patients. The tumor features, including tumor locations and growth patterns are collected through the MRI.

To create a normative model, data from 849 healthy children were sourced from four databases: (i) 61 were locally recruited in Beijing; (ii) 69 from the fcon_1000 projects dataset; (iii) 450 from the Child Connectome Project (devCCNP)27; (iv) 269 from the Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center. After excluding those with severe cerebellar compression or poor image quality, the final analysis included 145 patients and 849 healthy children. The phenotype of all participants is summarized. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University (Approval No. KY 2019-124-02) and conducted in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

MRI acquisition and processing

All participants underwent a structural MRI using a 3.0 T Ingenia CX scanner (Philips Healthcare, Best, Netherlands) with a 32-channel head coil. The scan included a whole-brain 3D T1-weighted anatomical sequence with 196 contiguous sagittal slices, each with a voxel size of 1.0 mm x 1.0 mm x 1.0 mm. The parameters for the 3D-T1 sequence were: repetition time (TR) = 6.572ms; echo time (TE) = 3.025 ms; flip angle (FA) = 8°; slice thickness = 1 mm; in-plane resolution = 1*1 mm.

For each individual, CTh was calculated using the CAT12 toolbox (version 12.7). The procedure involved segmenting MRI data to distinguish gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid. Then, the pial surface and gray matter/white matter boundary were reconstructed, and CTh was measured as the distance between the corresponding vertices28. The cortex was parcellated into 210 distinct regions using the Human Brainnetome Atlas, and the mean CTh for each region was calculated29.

In this study, the author manually delineated the brainstem tumor regions using MRIcronGL software, which was subsequently reviewed for accuracy by two neurosurgical experts. The marked NIFTI images were then processed using the Nibabel tool in Python. Tumor volume was determined by quantifying the number of voxels within the marked regions and factoring in voxel dimensions.

Normative modeling

Combat was used to harmonize MRI data across three datasets and address inter-scanner variability. The combat method effectively reduces non-biological variance from site differences while preserving biological variability30. This approach ensured uniformity across datasets, accounting for age, gender, and total intracranial volume (TIV) as covariates without diagnostic labels.

We developed normative models for CTh across 210 distinct cerebral regions. We used Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), a Bayesian technique implemented in Python 3.9 and PCNToolkit 0.22, to create region-specific models. We incorporate age, gender and TIV as covariates. GPR accounts for prediction uncertainty and provides probability distributions for predicted volumes31. We validated the models through 10-fold cross-validation on the healthy control dataset before finalizing the normative models. After that, these models were used to predict CTh for each participant and assess any deviations.

We evaluated CTh deviations for patients using percentile charts derived from healthy controls. We quantified these deviations by comparing the observed CTh with the predictions from the normative model. The deviation for each region was determined using a specific Eq. (1):

where yij is the CTh, ŷij is the expected CTh estimated from the GPR, σij is the predictive uncertainty, and σnj is the variance learned from the normative distribution \(\:n\). Zij refers to the CTh deviation of one brain region.

Subtype classification using spectral clustering method

To identify biotypes of patients with brainstem tumors, we performed spectral clustering analysis on the cortical deviation maps of 145 patients using the Scikit-learn library. Specifically, spectral clustering was applied to these maps to cluster the participants into distinct subgroups. The optimal number of clusters was determined based on the Calinski-Harabasz Scores.

Outlier definition and calculation

Outliers indicating significant CTh deviations were identified using the absolute value of Z-scores. Regions with \(\left| Z \right|>1.96\) were classified as extreme deviations, representing the 2.5th percentiles at both ends of the normative distribution. For each brain region, the proportion of individuals with extreme positive deviations was defined as the extreme positive deviation rate. In contrast, the proportion of individuals with extreme negative deviations was defined as the extreme negative deviation rate.

These thresholds focus on identifying substantial CTh deviations. For each participant, we computed the total outlier count of negative deviation in CTh (tOCN-CT) and the total outlier count of positive deviation in CTh (tOCP-CT) across all 26 regions. This method allows for a comprehensive evaluation of significant decreases and increases in CTh associated with the disease.

Statistical analysis

In SPSS (version 26.0) statistical analysis, we compared two subtypes across multiple factors. Since age is a well - known confound factor for overall survival (OS) and cerebellar thickness (CTh) deviations, it was adjusted in all analyses, including intergroup comparisons, survival analysis, and Cox regression. For continuous variables (total CTh deviation rate, tOCN - CT, tOCP - CT, KPS, duration, tumor volume, and OS), Mann - Whitney U tests were used based on data normality. Nonparametric Kruskal - Wallis tests were employed for multi - group differences, followed by Dunn’s post hoc tests for pairwise comparisons. Categorical variables (e.g., gender, tumor growth patterns) were analyzed using ANCOVA. Two - way ANCOVA evaluated the interaction of tumor growth patterns and subtypes on clinical factors. Kaplan - Meier survival analysis and Cox proportional hazards models estimated subtype survival risks, with log - rank tests for statistical differences. Statistical significance was set at a two - tailed p < 0.05.

Preprint

A previous version of this manuscript was published as a preprint on bioRxiv32. However, the current submission has undergone substantial revisions and improvements compared to the preprint. Specifically, we have revised the title, updated the figures, and expanded the content to include new results.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of pediatric brainstem tumor patients

The study enrolled 145 pediatric patients with brainstem tumors with median age about 8.0 years (interquartile range [IQR]:6.0-11.0). All patients exhibited balanced sex distribution (72 boys, 49%; 73 girls, 51%). Diffuse tumor growth patterns predominated (114 patients, 78.6%), and tumor locations included the pons (89 patients, 61.4%), multifocal regions (31, 21.4%), midbrain (11, 7.6%), and medulla (14, 9.7%). Key clinical characteristics included a median illness duration of 2.0 months (IQR: 1.0–3.0), median Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) score of 80 (IQR: 70–80), and median tumor volume of 25.9 mm³ (IQR: 17.7–34.4). Cortical thickness measures showed median tOCN_CT of 2.0 (IQR: 1.0–3.0) and tOCP_CT of 3.0(IQR: 2.0–4.0) (see Table 1).

Specifically, we performed age-based differential analyses on key variables including symptoms, H3K27M mutation status, tumor growth pattern, tumor volume, and cerebral cortical thickness deviation. Results indicated that the occurrence of symptoms such as nausea (U = 1693, p = 0.04) and dysarthria (U = 1343, p = 0.005), as well as the quantity of tOCP_CT (partial r = -0.36, p < 0.005), were significantly correlated with age (see Supplementary Table 1).

CTh heterogeneous alterations in patients with brainstem tumor

Our findings demonstrated the schematic diagrams of Gaussian process regression trajectory curves for the deviations in cortical thickness of two brain regions, which were related to age (Fig. 2a). Notably, over 25% of patients had extreme deviations in at least five brain regions. As the number of deviated regions exceeded ten, the proportion of patients with increased cerebellar thickness (CTh) declined. Meanwhile, 13% of patients constantly had reduced CTh, a pattern absent in healthy children. Additionally, about 1% of patients still had significant deviations when there were more than 25 deviated regions (Fig. 2b), indicating substantial CTh heterogeneity among brainstem tumor patients. Mapping the deviations revealed cortical thickening in the prefrontal lobe, precentral gyrus, postcentral gyrus, parietal lobe, and temporal pole. In contrast, extensive cortical atrophy was seen in the inferior temporal gyrus, orbitofrontal gyrus, and occipital lobe (Fig. 2c). A comparative analysis verified significant differences in these regions between patients and healthy children (Fig. 2d).

Heterogeneity analysis of cerebral CTh in patients with brainstem tumors. (a) Schematic diagram illustrating the curve fitting process for the Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) normative model. Line graphs display the cortical thickness (CTh) trajectory with age. Blue line represents the modeled trend. Brain maps below represent one patient’ spatial overlap maps of deviations. Color scale indicates z-score with warm colors for positive deviations and cool colors for negative deviations. (b) Butterfly diagram depicting the extreme deviation rate across different brain regions. X-axis refers to number of extremely deviated regions. Y-axis refers to percentage of cases, showing the distribution of extreme deviation counts across groups. (c) Spatial overlap map showing areas of positive deviation and negative deviation of CTh in patients and healthy children (HCs). (d) Comparative analysis highlighting differences in CTh deviations between patients and healthy children. The red areas refers to significant brain regions.

Relationship between CTh devaitions and clinical characteristics in patients with brainstem tumor

Given the clinical relevance of age in neurodevelopmental trajectories, we conducted an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with age as a covariate to examine relationships between CTh deviations and clinical characteristics. ANCOVA analysis revealed significant differences in tOCN_CT values across tumor growth patterns (Fig. 3a). Specifically, patients with focal tumors exhibited significantly more brain regions with tOCN_CT than those with diffuse tumors (F (1,143) = 12.63, p = 0.0005), indicating that focal tumors are associated with reduced CTh. Kruskal-Wallis test results revealed significant differences in tOCN_CT values across tumor locations (H = 8.83, p = 0.032). Post-hoc Dunn’s test with Bonferroni correction identified the midbrain subgroup as having significantly higher tOCN_CT levels compared to other regions (p = 0.02) (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, partial correlation analysis revealed a positive correlation between tumor volume and tOCP_CT (partial r = 0.17, p = 0.047) (Figure. 3c), as well as between tOCN-CT and OS (r = 0.44, p = 0.001) (Figure. 3d). These results underscore the influence of clinical characteristics on CTh in brainstem tumor patients. However, there was no significant difference in tOCN_CT and tOCP_CT between different H3K27M genotype statuses (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Clinical effects on CTh deviation. (a) Mann-Whitney U test compared tOCP_CT and tOCN_CT in focal and diffuse tumors. F = 12.6, p = 0.0005 showed significant group differences. (b) Kruskal-Wallis H test examined tOCP_CT and tOCN_CT across tumor locations, with Dunn’s post-hoc test. Dunn’s test p = 0.0018 indicated tOCN_CT difference between midbrain and pons tumors. Box represents IQR of tOCN_CT, whiskers cover 1.5×IQR, and scattered points are outliers. (c) Partial correlation between tumor volume and tOCP_CT. (d) Pearson correlations between PFS and tOCN_CT. Pearson correlation between PFS and tOCN_CT. Dots are data points, regression line shows trend, shaded area is 95% CI. Partial r and p-value show correlation strength and significance. OS overall survival, tOCN_CT total outliers count of negative deviation of cortical thickness, tOCP_CT total outliers count of positive deviation of cortical thickness.

CTh deviations reveal significant differences between brainstem tumor subtypes

The spectral clustering analysis identified two distinct subtypes, providing an optimal classification of the patient cohort (Supplementary Fig. 2). Specifically, 100 patients were categorized into Subtype 1, while 45 were assigned to Subtype 2. Specifically, Subtype 1 exhibited widespread positive deviations, predominantly in the postcentral gyrus, temporal pole, middle frontal gyrus, and superior parietal lobule (Fig. 4a). In contrast, Subtype 2 demonstrated extensive negative deviations, primarily in the temporoparietal junction, inferior frontal gyrus, and inferior temporal gyrus (Fig. 4b). Further, two-sample t-tests identified the prefrontal lobe, superior frontal gyrus, superior temporal gyrus, middle temporal gyrus, supramarginal gyrus, and parietal lobe as regions with the most significant differences between the two subtypes, particularly in the precentral gyrus and parietal lobe (PFDR < 0.05) (Fig. 4c). These findings highlight the substantial heterogeneity in CTh deviation patterns among brainstem tumor subtypes.

Spatial overlap map of CTh deviations in subtypes. (a) The mean, positive and negative CTh deviations map for Subtype 1 (b) The mean positive and negative CTh deviations map for and Subtype 2 The deviations were represented as a z score, with red indicating positive deviations and blue indicating negative deviations. Darker color means higher deviation. (c) Differences between the two subtypes. The red areas represent significant brain regions.

Clinical differences between two subtypes

Univariate analysis demonstrated no significant differences between the two subtypes in gender distribution, clinical symptoms (headache, nausea, diplopia), tumor growth patterns (focal/diffuse), KPS, or tumor volumes (all p > 0.05) (see Supplementary Table 2). However, Subtype 1 patients exhibited a younger median age compared to Subtype (U = 1755.5, p = 0.034) (see Table 2). This suggests that younger age is associated with higher cortical plasticity.

Two-way ANCOVA analysis indicated a marginally significant main effect of subtype on duration (F (1,141) = 2.78, p = 0.09), as well as a significant main effect of tumor growth pattern on duration (F (1,141) = 10.28, p = 0.002). Notably, the interaction effect between subtype and tumor growth pattern on duration was significant (F (1, 141) = 4.20, p = 0.04) (Fig. 5). These findings suggest that tumor growth pattern dependently influence duration. However, the interaction between tumor growth pattern and subtype does significantly impact this outcome measure.

Interaction effects of subtype and tumor growth pattern on duration. This interaction plot depicts the joint influence of subtypes and tumor growth pattern on duration. Two-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was conducted to assess the interaction between tumor subtype and growth pattern. Blue solid line refers to focal tumor. Orange dashed line refers to diffuse tumor. An F-value of 4.2 and a p-value of 0.04 suggest a statistically significant interaction between tumor subtype and growth pattern.

Cox regression of prognosis and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis

To identify prognostic factors for overall survival (OS), univariate Cox regression analysis was first performed on clinical and radiographic variables. Significant variables such as symptoms, duration, tumor growth pattern, and tOCN_CT (p > 0.05) were selected for multivariate analysis (see Supplementary Table 2). Multivariable analysis identified longer symptom duration as an independent protective factor (coef = -0.08, 95% CI: -0.02–0.87, p = 0.01), while diffuse tumor growth trended toward worse prognosis (coef = 0.66, 95% CI: -0.02–0.87, p = 0.05). CTh deviations and neurological symptoms (diplopia, dysphagia) did not independently predict survival outcome. However, tOCN_CT suggested no significant association with reduced risk (coef = -0.02, 95% CI: 0.04–0.92, p = 0.46) (see Table 3). This suggests that the association between tOCN_CT and prognosis was attenuated by stronger prognostic factors such as disease duration and tumor growth pattern.

Furthermore, the Kaplan-Meier survival curves for Subtype 1 and Subtype 2 illustrate a significant difference in survival probabilities over time (p = 0.02). The effect size, calculated as Cohen’s d = 0.61, indicates a moderate effect according to Cohen’s guidelines (Fig. 6). Specifically, Subtype 2 demonstrates a higher survival probability compared to Subtype 1 throughout the observed period. The shaded areas around the curves represent the 95% confidence intervals, indicating the reliability of the survival estimates for each subtype. This significant difference in survival probabilities suggests that Subtype 1 has a better prognosis than Subtype 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis between subtypes. Kaplan-Meier survival curves showing overall survival differences between subtypes. Blue line illustrates the survival probability trend for Subtype 1 patients. Orange line illustrates the survival probability trend for Subtype 2 patients. p = 0.02 denotes a statistically significant survival difference between subtypes, assessed via the log-rank test. The shaded areas typically represent the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the survival probability.

Discussion

Prompted by the unclear mechanisms underlying brainstem tumors’ impact on the whole brain, our study construed normative growth models of CTh to uncover heterogeneous patterns of cerebral structural alteration in patients with brainstem tumors. The study found that cortical thickening predominantly occurs in the postcentral and precentral gyri, while thinning is most prominent in the superior temporal and orbitofrontal gyri. Notably, the pattern of CTh changes was significantly associated with tumor growth patterns. Specifically, focal tumors were associated with cortical thinning, whereas diffuse tumors were linked to cortical thickening. Additionally, tumor volume emerged as an essential factor influencing CTh changes, with larger tumors generally corresponding to more thickening regions. Furthermore, based on the CTh deviation patterns of each patient, we classified them into two biological subtypes: subtype 1, characterized by cortical thickening, and subtype 2, characterized by cortical thinning. Prognostic analysis showed that patients in subtype 2 had better outcomes. These findings highlight the global impact of brainstem tumors on cortical structures and uncover potential neuropathological mechanisms. Moreover, preoperative CTh evaluation could serve as a prognostic biomarker, supporting the development of personalized and precise treatment strategies.

The mechanism behind extensive structural alterations induced by brain tumors remains complex. For example, patients with insula gliomas exhibit an increase in the gray matter volume of the contralateral insula33, while patients with frontal lobe gliomas show CTh reorganization in the contralateral superior parietal lobule34. Typically, structural changes in the cortex induced by brain gliomas are primarily characterized by infiltration and compression of cortical regions. For instance, cerebral gliomas frequently lead to cortical thinning in the contralateral hemisphere35, which may be attributed to the infiltrative edema compression induced by the tumor36. Another potential explanation is that gliomas may trigger plasticity mechanisms in the brain37. This plasticity could partially explain why most glioma patients exhibit neurologically intact or only mildly impaired during standard neurological assessments38. Notably, cortical thickening is frequently observed in the precentral and postcentral gyri, aligning with the typical motor and sensory deficits observed in patients with brainstem tumors. These results suggest that cortical reorganization resulting from tumors should be regarded as a primary change. Particularly when the lesion has not yet expanded sufficiently to affect distant regions of ipsilateral or contralateral hemispheres, this reorganization persists37. Additionally, midline and non-midline tumors influence brain structure through distinct mechanisms due to significant differences in progression, location, and pathological characteristics39. This finding may explain the coexistence of cortical thickening and thinning phenomena in patients with brainstem tumors.

We further found that tumor growth patterns significantly influenced CTh changes in patients with brainstem tumors. Focal tumors primarily resulted in cortical thinning. These tumors include low-grade astrocytomas, hemangioblastomas, oligodendrogliomas, pilocytic astrocytomas, and ependymomas. They are characterized by slow growth, localized proliferation, and limited infiltration, with a relatively prolonged disease course6,40. Notably, the disease duration in patients with focal tumors was significantly longer than those with diffuse tumors. This progression aligns with the dynamic process of structural brain decompensation induced by glioma41. Additionally, focal tumor patients often present with symptoms of intracranial hypertension, such as headaches and nausea, with a subset developing hydrocephalus. These factors may contribute to cortical thinning42. Cortical thinning may also result from pathophysiological changes, including neuronal loss, synaptic pruning, reactive gliosis, and alterations in blood flow or interstitial fluid43. Increased white matter volume may also contribute to cortical thinning.

In contrast, diffuse tumors predominantly led to cortical thickening, consistent with the characteristics of diffuse midline glioma (DMG) patients. DMG causes extensive myelinated axon destruction, leading to cortical thickening in sensorimotor areas, salience networks, and the default mode network11. Cortical thickening in diffuse tumor patients may be due to the infiltration of myelinated axons by high-grade glioma cells, causing compensatory cortical thickening due to myelin loss44. Glioma cells can infiltrate large portions of the brain, possibly triggering disinhibition of nearby neural networks45,46. Additionally, structural plasticity may introduce cortical thickening due to various factors, including increased cell size, elevated density of columnar structures, the formation of new neuroglial cells, and modifications such as myelin remodeling, axonal growth, and angiogenesis47. Our findings further verify this phenomenon, revealing that as tumor volume increases, the regions of cortical thickening also expand correspondingly. Furthermore, white matter tracts are known to be disrupted in glioma patients and diffusion metrics suggest early infiltration by diffuse gliomas48. Previous studies have reported white matter microstructural damage near the tumor, with degeneration extending to the contralateral hemisphere. These findings suggest that gliomas may have chronic effects, potentially leading to distal tract deterioration49.

These findings not only reveal the differential impact of brainstem tumors on global brain alterations at the individual level but are also crucial for assessing disease severity and predicting prognosis. Patients with significant cortical thinning may face a higher risk of neurological damage, while those with larger tumors may require more aggressive interventions23. Based on CTh deviation patterns, patients were categorized into two subtypes. The favorable prognosis in Subtype 2 may be associated with distinct patterns of cortical thinning, indicating slower tumor progression or more effective neural reorganization. These mechanisms could potentially mitigate the tumor’s overall impact on brain function50. Intraoperative neuroprotection is essential for cognitive recovery. It depends on understanding the brain’s plasticity and network dynamics caused by the tumor38,51. Classifying patients based on CTh deviations enhances our understanding of tumor heterogeneity. Integrating CTh changes into imaging assessments deepens our comprehension of brainstem tumor pathophysiology and supports personalized treatments. This approach has the potential to facilitate more targeted therapies, minimize side effects, and enhance the accuracy of prognostic assessments. Additionally, this study offers new insights into the brainstem tumor burden effect, providing a foundation for further exploration of its mechanisms and progression52.

As brainstem tumors clinical trials face challenges, identifying reliable imaging biomarkers to guide precision treatment has become a novel strategy4. Although quantifying heterogeneity is more complex and computationally demanding than calculating mean intensity, it is critical for developing preoperative imaging biomarkers to guide treatment decisions53. Some imaging biomarkers, including tumor-induced deformation and connectivity changes, have shown good predictive performance18,54. Cortical thickness, as a simple and accessible metric, has potential as a neuroimaging marker, with thinning possibly indicating a better prognosis52. Normative comparisons can help address the limitations of CTh in clinical practice55,56.

However, this study has several limitations that warrant further investigation. First, these findings need validation in more extensive, multi-center cohorts to ensure their generalizability across different populations and healthcare settings. The current sample size may not fully capture the variability in CTh deviations among different demographic groups, including age, sex, and ethnicity. Second, while this study focuses on CTh deviations, it does not account for genomic alteration or proteomic signature, which are critical drivers of tumor aggressiveness and treatment resistance. Future research should integrate multi-omics data (genomics, epigenomics, proteomics) with neuroimaging to dissect how molecular heterogeneity contributes to CTh remodeling and prognostic disparities. Additionally, combining CTh with multimodal imaging biomarkers—such as DTI for white matter tract integrity, perfusion MRI for hemodynamic mapping, and PET for metabolic profiling—could provide a holistic view of tumor-brain interactions. Such integrative approaches may uncover synergistic biomarkers that better predict treatment response and survival, ultimately bridging the gap between molecular mechanisms and clinical phenotypes Third, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causal relationships between CTh deviations and clinical outcomes. Longitudinal studies are needed to assess the dynamic changes in CTh over time and their associations with disease progression, treatment response, and long-term survival. Fourth, while we adjusted for age as a covariate, the impact of treatment modalities (e.g., surgical resection extent, chemotherapy regimens) on disease duration and OS was not systematically analyzed, potentially confounding prognostic interpretations. This approach could refine patient stratification and inform personalized treatment strategies. Addressing these limitations in future research will enhance our understanding of the role of CTh deviations in brainstem tumor pathology and prognosis, ultimately improving clinical decision-making and patient outcomes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study reveals the impact and specific patterns of brainstem tumor heterogeneity on cortical thickness alterations. Cortical thickness decompensation is closely associated with better survival outcomes. Furthermore, the study demonstrates a significant correlation between changes in cortical thickness, tumor volume, and growth patterns. These findings highlight the critical role of cortical thickness deviations as a non-invasive imaging marker for the subtyping and survival prediction of brainstem tumor patients, potentially offering new tools and strategies for personalized treatment.

Data availability

Data and analysis codes are available upon reasonable request. For access, please contact the corresponding author, Liwei Zhang, at zhangliweittyy@163.com.

References

Xiao, D. et al. National brain tumour registry of China (NBTRC) statistical report of primary brain tumours diagnosed in China in years 2019–2020. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 34, 100715 (2023).

Chiarelli, P. A., Chu, J. K. & Krieger, M. D. Brainstem tumors in Textbook of Pediatric Neurosurgery (ed. Di Rocco, C.), 1957–1983 (Springer, 2020).

Chou, S. C. et al. Contemporary management of pediatric brainstem tumors. Adv. Tech. Stand. Neurosurg. 49, 231–254 (2024).

Dellaretti, M. et al. Diffuse brainstem glioma: prognostic factors. J. Neurosurg. 117, 810–814 (2012).

Boukaka, R. G. et al. Brainstem tumors in children: a monocentric series in the light of genetic and bio-molecular progress in pediatric neuro-oncology. Front. Pead. 11 (2023).

Klimo, P. Jr et al. Management and outcome of focal low-grade brainstem tumors in pediatric patients: the St. Jude experience. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 11, 274–281 (2013).

Gagliardi, F. et al. Gamma knife radiosurgery as primary treatment of low-grade brainstem gliomas: A systematic review and metanalysis of current evidence and predictive factors. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 168, 103508 (2021).

Jallo, G. I., Biser-Rohrbaugh, A. & Freed, D. Brainstem gliomas. Childs Nerv. Syst. 20, 143–153 (2004).

Louis, D. N. et al. The 2016 world health organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 131, 803–820 (2016).

Hoffman, L. M. et al. Clinical, radiologic, pathologic, and molecular characteristics of Long-Term survivors of diffuse intrinsic Pontine glioma (DIPG): A collaborative report from the international and European society for pediatric oncology DIPG registries. J. Clin. Oncol. 36, 1963–1972 (2018).

Zhang, S. et al. Cortical Myelin and thickness mapping provide insights into whole-brain tumor burden in diffuse midline glioma. Cereb. Cortex 34 (2024).

Smith, L. H. & DeMyer, W. E. Anatomy of the brainstem. Semin Pediatr. Neurol. 10, 235–240 (2003).

Acharya, A., Ren, P., Yi, L., Tian, W. & Liang, X. Structural atrophy and functional dysconnectivity patterns in the cerebellum relate to cerebral networks in SvMCI. Front. Neurosci. 16, 1006231 (2022).

Duffau, H. Diffuse low-grade gliomas and neuroplasticity. Diagn. Interv Imaging. 95, 945–955 (2014).

Wang, X., Zhou, C., Wang, Y. & Wang, L. Microstructural changes of white matter fiber tracts induced by insular glioma revealed by tract-based Spatial statistics and automatic fiber quantification. Sci. Rep. 12, 2685 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Glioma invasion along white matter tracts: A dilemma for neurosurgeons. Cancer Lett. 526, 103–111 (2022).

Newman, D. B. Anatomy and neurotransmitters of brainstem motor systems. Adv. Neurol. 67, 219–244 (1995).

Wittenberg, G. F. Experience, cortical remapping, and recovery in brain disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 37, 252–258 (2010).

Pistoia, F. et al. Disembodied Mind: cortical changes following brainstem injury in patients with Locked-in syndrome. Open. Neuroimag J. 10, 32–40 (2016).

Cirillo, C. et al. Post-stroke remodeling processes in animal models and humans. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 40, 3–22 (2019).

Alia, C. et al. Neuroplastic changes following brain ischemia and their contribution to stroke recovery: novel approaches in neurorehabilitation. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 11 (2017).

Osswald, M. et al. Brain tumour cells interconnect to a functional and resistant network. Nature 528, 93–98 (2015).

Duffau, H. Introducing the concept of brain metaplasticity in glioma: how to reorient the pattern of neural reconfiguration to optimize the therapeutic strategy. J. Neurosurg. 136, 613–617 (2021).

Chieffo, D. P. R. et al. Brain tumor at diagnosis: from cognition and behavior to quality of life. Diagnostics (Basel) 13 (2023).

Boccuni, L. et al. Neuromodulation-induced prehabilitation to leverage neuroplasticity before brain tumor surgery: a single-cohort feasibility trial protocol. Front. Neurol. 14, 1243857 (2023).

Vanan, M. I. & Eisenstat, D. D. DIPG in children – What can we learn from the past? Front. Oncol. 5 (2015).

Zuo, X. N. et al. An open science resource for Establishing reliability and reproducibility in functional connectomics. Sci. Data 1, 140049 (2014).

Keller, S. S. & Roberts, N. Voxel-Based morphometry of Temporal lobe epilepsy: an introduction and review of the literature. Epilepsia 49, 741–757 (2008).

Fan, L. et al. The human brainnetome atlas: A new brain atlas based on connectional architecture. Cereb. Cortex 26, 3508–3526 (2016).

Fortin, J. P. et al. Harmonization of cortical thickness measurements across scanners and sites. Neuroimage 167, 104–120 (2018).

Marquand, A. F., Rezek, I., Buitelaar, J. & Beckmann, C. F. Understanding heterogeneity in clinical cohorts using normative models: beyond case-control studies. Biol. Psychiatry 80, 552–561 (2016).

Jia, H. Normative growth modeling of cortical thickness identify neuroanatomical variability and distinct subtypes in brainstem tumor patients. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.08.01.606270 (2024).

Almairac, F., Duffau, H. & Herbet, G. Contralesional macrostructural plasticity of the insular cortex in patients with glioma: A VBM study. Neurology 91, e1902–e1908 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Structural and functional reorganization within cognitive control network associated with protection of executive function in patients with unilateral frontal gliomas. Front. Oncol. 10, 794 (2020).

Kinno, R. et al. Differential effects of a left frontal glioma on the cortical thickness and complexity of both hemispheres. Cereb. Cortex Commun. 1, tgaa027 (2020).

Miller, P., Coope, D., Thompson, G., Jackson, A. & Herholz, K. Quantitative evaluation of white matter tract DTI parameter changes in gliomas using nonlinear registration. Neuroimage 60, 2309–2315 (2012).

Desmurget, M., Bonnetblanc, F. & Duffau, H. Contrasting acute and slow-growing lesions: a new door to brain plasticity. Brain 130, 898–914 (2007).

Duffau, H. Lessons from brain mapping in surgery for low-grade glioma: insights into associations between tumour and brain plasticity. Lancet Neurol. 4, 476–486 (2005).

Waqar, M. et al. Diagnostic challenges, management and outcomes of midline low-grade gliomas. J. Neurooncol. 120, 389–398 (2014).

D’aes, T. & Mariën, P. Cognitive and affective disturbances following focal brainstem lesions: A review and report of three cases. Cerebellum 14, 317–340 (2014).

Lv, K. et al. Contralesional macrostructural plasticity in patients with frontal low-grade glioma: a voxel-based morphometry study. Neuroradiology 65, 297–305 (2023).

Boes, A. D. et al. Network localization of neurological symptoms from focal brain lesions. Brain 138, 3061–3075 (2015).

Altmann, A. et al. A systems-level analysis highlights microglial activation as a modifying factor in common epilepsies. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 48 (2021).

Douw, L. A. O., Breedt, L. C. & Zimmermann, M. L. M. Cancer Meets neuroscience: the association between glioma occurrence and intrinsic brain features. Brain 146, 803–805 (2023).

Sahm, F. et al. Addressing diffuse glioma as a systemic brain disease with single-cell analysis. Arch. Neurol. 69, 523–526 (2012).

Yang, Y. et al. Brain tumor networks in diffuse glioma. Neurotherapeutics 19, 1832–1843 (2022).

Xin, W. & Chan, J. R. Myelin plasticity: sculpting circuits in learning and memory. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 21, 682–694 (2020).

Jutten, K. et al. Diffusion tensor imaging reveals microstructural heterogeneity of Normal-Appearing white matter and related cognitive dysfunction in glioma patients. Front. Oncol. 9, 536 (2019).

Zhang, S. et al. Multiparametric mapping of white matter reorganizations in patients with frontal glioma-related epilepsy. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 29, 2366–2376 (2023).

Szulc-Lerch, K. U. et al. Repairing the brain with physical exercise: cortical thickness and brain volume increases in long-term pediatric brain tumor survivors in response to a structured exercise intervention. Neuroimage Clin. 18, 972–985 (2018).

Duffau, H. & New Philosophy Clinical pearls, and methods for intraoperative cognition mapping and monitoring a La Carte in brain tumor patients. Neurosurgery 88, 919–930 (2021).

Lamichhane, B. et al. Structural Gray matter alterations in glioblastoma and high-grade glioma-A potential biomarker of survival. Neurooncol Adv. 5, vdad034 (2023).

Alic, L., Niessen, W. J. & Veenland, J. F. Quantification of heterogeneity as a biomarker in tumor imaging: a systematic review. PLoS One 9, e110300 (2014).

Wei, Y. et al. Structural connectome quantifies tumour invasion and predicts survival in glioblastoma patients. Brain 146, 1714–1727 (2023).

Nagtegaal, S. H. J. et al. Effect of radiation therapy on cerebral cortical thickness in glioma patients: Treatment-induced thinning of the healthy cortex. Neurooncol Adv. 2, vdaa060 (2020).

Tahedl, M. Towards individualized cortical thickness assessment for clinical routine. J. Transl Med. 18, 151 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the patients and their families for their cooperation and participation in this study. Their support has been invaluable to the success of our research.

Funding

This study was supported by the STI2030-Major Projects 2021ZD0200201 and Beijing Municipal Public Welfare Development and Reform Pilot Project for Medical Research Institutes (grant ID: JYY202X-X).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Liwei Zhang and Lingzhong Fan designed the task. Heyuan Jia analyzed all data and edited the manuscript. Kaikai Wang prompted the method. Peng Zhang revised the manuscript. Congying Chu checked the research method. Mingxin Zhang and Yiying Mai helped to collect the data. Xuntao Yin helped to collect data of healthy children.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

Consent obtained directly from patients’ parents. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All participants’ parents gave their written informed consent prior to study enrolment. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jia, H., Wang, K., Zhang, P. et al. Cortical thickness deviations as biomarker for subtyping and prognosis in pediatric brainstem tumors. Sci Rep 15, 13132 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95017-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95017-7