Abstract

Extensive research is being conducted in fabricating flexible dry electrodes for electrocardiogram monitoring, but the electrodes’ efficacy in clinical settings remains underexplored. In transition from research to commercial settings, investigating the electrode’s performance in real-time monitoring and patient’s comfort is very crucial. This study compares the ECG signal quality between flexible silver nanorods embedded in polydimethylsiloxane (AgNRs-PDMS) dry electrodes and commercially available metal electrodes. This study, conducted in a hospital, involves 50 subjects (40 males, 10 females; age range: 20–74) among which 41 were with cardiovascular disease and 9 normal subjects. The fabricated dry electrodes are biocompatible and have a lower skin-to-electrode impedance than the commercial electrodes, resulting in high-fidelity ECG signals. Signal quality was assessed based on parameters such as signal-to-noise ratio, mean amplitude, maximum amplitude, power spectral density, and heart rate comparison. The AgNRs-PDMS electrodes demonstrated superior SNR, confirmed using a paired t-test, with a p-value close to 0, indicating a significant difference in comparison with commercial electrodes. The amplitude of ECG signals captured by AgNRs-PDMS electrodes and the heart rate were observed to be comparable to metal electrodes. For automated arrhythmia classification of the ECG signals, two models were implemented. The first model utilized R-R interval for arrhythmic rhythm classification, while the second model used principal component analysis (PCA) for dimensionality reduction followed by support vector machine (SVM) to classify arrhythmic beats. Large arrhythmia data sets like the MIT-BIH arrhythmia database were used for training and validating the above models. Accuracy results from the MIT-BIH test data set were 97% for the R-R interval method and 93% for the SVM method. The heart beats obtained from an arrhythmic patient using commercial metal electrodes and AgNRs-PDMS electrodes were classified using the classifiers. The AgNRs-PDMS dry electrodes offer superior signal quality, ease of use due to gel-free nature, and reusability, making them a promising alternative to commercial electrodes for clinical ECG monitoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The electrocardiogram (ECG), a vital diagnostic tool for heart monitoring, is used in hospitals with ECG equipment and electrodes. The type of electrode and the interface between the skin and the electrode significantly impact ECG signal quality. Metal electrodes and wet Ag/AgCl electrodes are commonly used in hospitals and clinics to capture ECG data1. Metal electrodes, being dry electrodes, are rigid, prone to motion artefacts, require skin abrasion and gel application. In contrast, Ag/AgCl electrodes, has robust and stable skin-to-electrode contact due to their gel layer. But the presence of gel can cause skin irritation due to prolonged use and gel dehydration can degrade the ECG signal quality. In addition, they are not reusable. Dry electrodes offers several advantages over the wet electrodes, including gel-free application, reduced skin preparation time and suitability for long-term ECG monitoring, without any skin irritation2. Due to their convenience, various dry electrodes are being explored which includes textile, polymer electrodes with conductive fillers like PEDOT: PSS, graphene and silver. In addition to this, electrodes with microstructures that penetrate the stratum corneum to reduce skin-to-electrode impedance are also being investigated3,4,5,6.

Clinical trials for all types of manufactured electrodes are essential as they provide a more variable and reliable environment than laboratory conditions, ensuring that the signal quality is not compromised. These trials help assess the patient’s comfort, ease of usage, and potential difficulties, such as skin irritation. Additionally, it aids in identifying the necessary improvements to enhance electrodes performance and facilitate market readiness7. Although previous studies on dry electrodes have demonstrated their feasibility on ECG monitoring, they lack validation of testing on sufficient number of participants, especially those with cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). In one study, textile electrodes were tested on 66 healthy participants to assess the effects of motion artifacts using signal-to-noise ratio (SNR)8. Another study evaluated non-contact capacitive electrodes on 10 subjects, with atrial fibrillation (AF) monitoring conducted on three healthy individuals and one participant with paroxysmal AF9. Most studies have been conducted in laboratory settings10. As a result, the comprehensive performance evaluation of dry electrodes in real-world hospital settings through extensive patient testing and detailed signal analysis based on SNR, ECG quality, amplitude, power spectral density (PSD), heart rate (HR), and feature comparisons remains insufficient.

CVDs are a significant cause of death worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), CVD accounted for 20.5 million deaths in 2021, contributing to one-third of all deaths globally11. To address the risk posed by CVD, affected patients need continuous monitoring of ECG signals. Automated classification systems provide a quick alerting mechanism, warning the patient well in advance when episodes of irregular cardiac activity are detected. Such systems help reduce the risk of mortality from CVD. Various works describing automated classification systems to detect cardiovascular disorders are available today. Artificial intelligence (AI) technologies and machine learning (ML) have demonstrated potential in automated classification and disease diagnosis12,13. Conventional techniques for diagnosing arrhythmias frequently depend on medical experts’ interpretation of ECGs. However, the incorporation of ML methods in arrhythmia diagnostics has been motivated by the complexities of arrhythmia patterns and the requirement for rapid and accurate detection. Cardiologists can save time and receive objective diagnostic results by applying ML tools to classify arrhythmias automatically. Tools like support vector machine (SVM)14,15, convolutional neural network (CNN)16, combination of CNN and long short memory network (LSTM)17, combination of discrete wavelet transform, and SVM18, and artificial neural network (ANN)19, are widely explored for analyzing ECG signals, classification, and analysis of different types of arrhythmias due to their ability to find patterns in large dataset. By using labelled datasets as a learning tool, these algorithms can accurately differentiate between cardiac rhythms that are normal and pathological. Furthermore, ML models can evolve and improve in response to fresh data, strengthening their diagnostic powers.

This research highlights the potential of dry electrodes for ECG monitoring, aiming to bridge the gap between laboratory testing and real-world clinical applications. The potential of the electrodes was demonstrated through a relatively large-scale study involving 50 subjects, including both CVD and healthy individuals. This study helps to evaluate the electrode’s capability to record signals from subjects with varying skin types and diverse cardiac conditions, thereby validating its performance under different physiological conditions. The study specifically investigates the performance of a flexible dry electrode composed of silver nanorods (AgNRs) embedded in polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) and compares it with commercial metal electrodes. The AgNR-PDMS dry electrodes were tested primarily on subjects with CVD to assess their effectiveness in detecting various heart rhythms across sample size with more CVD subjects. Their performance was analyzed based on key clinical parameters, including SNR, PSD, ECG signal quality (amplitude), and HR accuracy. Conducted in a clinical setting, this study demonstrates the suitability of these dry electrodes for medical applications.

Due to the conductive silver layer on their surface, the fabricated electrodes exhibited low skin-to-electrode impedance, enhanced skin conformance for long-term ECG monitoring, and reusability. A comparative analysis of ECG signals obtained from commercial metal electrodes and the fabricated dry electrodes was performed using statistical methods, including paired t-tests. Additionally, an automated arrhythmia classification system utilizing R-R interval features and a SVM model was employed to evaluate whether the ECG signal quality was sufficient for reliable automated classification.

Materials and methods

Silver metal powder (99.9%) was purchased from CDH chemicals. Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) was prepared from silicon elastomer Sylgard 184 and a curing agent obtained from Dow Corning Inc. USA.

Fabrication of flexible AgNRs-PDMS dry electrodes

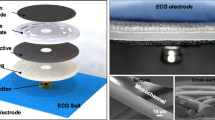

The AgNRs-PDMS electrode used in this study consists of a layer of AgNRs embedded within the PDMS matrix. The fabrication steps of the electrodes involve the following steps. First, AgNRs are grown on a silicon substrate using the glancing angle deposition (GLAD) technique as illustrated in (Fig. 1a). GLAD is a physical vapor deposition method that allows the controlled growth of nanostructures with specific morphologies. In this technique, the material is deposited on the substrate at an oblique angle of 85º, causing the incident atoms to form nucleation centers on the silicon substrate. The angle α represents the angle between the vapor flux and the substrate’s normal. Due to the shadowing effect, taller structures grow while smaller ones are blocked, leading to columnar structures aligned with the vapor flux direction. The angle β denotes the tilt angle of the columns, defined between the columnar axis and the substrate normal, as shown in (Fig. 1b). Next, the flexible PDMS substrate is prepared by mixing silicon elastomer with a hardening agent in a 10:1 ratio. The mixture is poured over AgNRs layer on the silicon substrate and cured in an oven at 80ºC. After curing, the PDMS is carefully peeled off the silicon substrate, resulting in silver nanorods embedded within the PDMS matrix.

Characterizations and clinical evaluation

Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM, Zeiss EVO 50) was used to analyze the surface morphology of the silver nanorods on the silicon substrate. Skin-to-electrode impedance, which measures how skin responds to externally applied electrical currents or voltages, was evaluated for commercial metal electrodes, Ag/AgCl electrodes, and the fabricated AgNRs-PDMS electrodes using an LCR meter (KEYSIGHT E4980A). For testing, two electrodes were placed on the forearm with a 3 cm centre-to-centre distance. A frequency sweep from 20 Hz to 1 kHz was performed at a sinusoidal voltage of 10 mV. Details of electrical, mechanical, long-term usability, and biocompatibility tests for these electrodes are discussed in our previous study20. The fabricated electrode is circular with a diameter of 4 cm.

The fabricated AgNRs-PDMS electrode was used for real-time ECG monitoring in a clinical setting at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) Rishikesh, Uttarakhand, India. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee with registration number AIIMS/IEC/24/365. Informed consent was collected from all the subjects and all steps were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The trial was conducted according to good clinical practice guidelines and was monitored by medical experts. A total of 50 subjects (40 male and 10 female), aged 20–74 years, participated in the study. Among them, 41 were CVD and 9 were normal subjects. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants before their inclusion in the study.

A Philips TC20 ECG machine was used for ECG signal acquisition. Signals were recorded using both AgNRs-PDMS electrodes and commercial metal electrodes. Minor skin pretreatment, such as gently rubbing the area with cotton, was performed before placing the electrodes. The electrodes were then positioned on the four limbs of the subject. To secure the electrodes in place, medical tape was used. The ECG machine settings were configured with a high-pass filter of 0.5 Hz and a low-pass filter of 150 Hz to display and print the ECG signals. Motion artifacts and baseline wander were disabled in the settings.

For the analysis of the ECG signals recorded from both electrodes, raw data were exported from the ECG machine without any built-in filtering. To denoise the signals, a 5th-order high-pass Butterworth filter of 0.5 Hz and a 50 Hz linear digital filter were applied during post-processing. The ECG data used for analysis were the unprocessed raw data exported from the machine. Additionally, the ECG machine used a scaling factor of 10 on the signals for display and printing purposes, which was not reflected in the raw data. As a result, the amplitude of the ECG signals in this study appears to be ten times lower than the values shown in the printed ECG reports. The SNR and PSD of the ECG signals obtained from both electrode types were compared. The electrode’s ability to accurately capture the R-R intervals was assessed by performing arrhythmia classification through both manual and automated methods and assessing the results. Arrhythmic beats detected with the AgNRs-PDMS electrode were classified using SVM with a linear kernel to identity anomalies. The Neurokit2 module was used for signal denoising, R-peak detection, and QRS delineation21. The ECG signal was analyzed for QRS complex and R peaks using the Biopeaks algorithm implemented in Python. Principal components analysis (PCA) was applied to the extracted ECG segments for dimensionality reduction with the Scipy and NumPy Python modules while the Scikit_learn module was used to develop the SVM classifier. Both classification methods were trained using the MIT-BIH arrhythmia database22. Figure 2 outlines the methodology used in this study and Table 1 lists the abbreviations for the different types of arrhythmias classified.

Signal-to-noise ratio evaluation of the electrodes

ECG consists of three main components: P, QRS and T waves. The P wave represents atrial depolarization, the QRS indicates ventricular depolarization and the T wave corresponds to ventricular repolarization. The frequency ranges of these waves are as follows: P wave (5 Hz to 30 Hz), QRS complex (8 Hz to 50 Hz), and T wave (0–10 Hz)23. ECG signals are often affected by noise, including powerline interference (50/60 Hz), motion artefacts, muscle noise, and baseline wander. Powerline interference results from electromagnetic disturbances, improper grounding, nearby electrical devices, or AC field induction in cables24. This potentially distorts the essential ECG features25. Baseline wander, caused by respiration, patient movement, or cable shifts, can alter signal amplitude and hinder peak detection, making ST-segment analysis for myocardial infarction diagnosis challenging. Filtering methods such as discrete wavelet transforms, and Butterworth high pass filters help mitigate the baseline wander26. Motion artefacts, caused by the variations in skin-to-electrode impedance can be reduced with electrodes having better skin conformance27.

In this study, the quality of the ECG signals captured by the AgNRs-PDMS electrodes was assessed by computing the SNR to determine the level of noise present. This was then compared to ECG signals recorded using metal electrodes on the same subject. SNR was calculated using ECG signals acquired from 45 subjects (36 males, 9 females, age range: 20–74 years). To minimize interference, a 0.5 Hz, 5th-order high-pass Butterworth filter was applied to prevent distortion of the P wave, while a 50 Hz linear digital filter was used to eliminate powerline interference28. SNR, defined as the ratio of signal power to background noise power \(\:\left(SNR=\frac{Power\:of\:signal}{Power\:of\:noise}\right)\) was calculated after filtering29.

Power spectral density evaluation of the electrodes

To evaluate whether the distribution of signal power across different frequency bands in ECG signals captured by AgNRs-PDMS electrodes is comparable to that of commercial metal electrodes, PSD was calculated. PSD analysis was performed using ECG signals from the same 45 subjects recruited for SNR calculation. PSD provides insights into the dominant frequency ranges within the ECG signal. Welch’s method, an improved periodogram technique, was used to compute PSD. In this method, the signal is divided into overlapping segments using a window function. Each segment undergoes a discrete Fourier transform, and the resulting periodograms are averaged to obtain the final PSD, ensuring a more reliable spectral estimation30,31. To evaluate the ability of AgNRs-PDMS electrodes to capture high-quality ECG signals across different patients, the maximum and mean amplitudes of the recorded ECG signals were analyzed and compared to those obtained using commercial metal electrodes. This assessment helps determine whether the AgNRs-PDMS electrodes can effectively record ECG signals from individuals with varying heart rhythms, both normal and abnormal, as well as from people with different skin types. A comparative analysis provides insights into whether the AgNRs-PDMS electrodes perform similarly to commercially used metal electrodes in capturing reliable ECG signals.

Heart rate comparison

HR is one of the crucial markers that gives information about the functioning of the heart. HR is defined as the number of beats per minute (bpm) and is calculated by obtaining the R-R interval, i.e. HR = 60,000/R-R interval (in milliseconds)32. Here, the R-R interval is the distance between R peaks of a successive QRS complex33. The relationship between HR and R-R interval is hyperbolic, but over a limited range, it is linear. These two parameters have been used interchangeably in a clinical setting32. R-R interval is crucial in calculating the irregular heartbeats caused by arrhythmias. R-R interval is also vital in calculating the heart rate variability (HRV), a sign of neurocardiac (brain-heart interaction) physiology33. The HR analysis was performed on the same subjects from which SNR was analyzed. The readings per subject were completed within a short interval to avoid any significant fluctuations in the HR. Readings were taken using both commercial metal electrodes and AgNRs-PDMS electrodes from the subject relaxing in a supine position. Readings per subject from both the metal and dry electrodes were selected for further analysis when the ECG signals became stable. The maximum and minimum of the R-R interval and the mean HR in the ECG signals were obtained. Then mean HR obtained from both metal and dry electrodes were compared to check the efficacy of dry electrodes in accurately calculating the HR, which is one of the important parameters for cardiac health.

Detection of tachycardia and bradycardia

The measurement of HR is crucial in detecting various arrhythmias like tachycardia, bradycardia, and ventricular and atrial fibrillation. Tachycardia and bradycardia can be easily detected by observing HR. If the HR is higher than 100 bpm, then it is tachycardia, and when it is less than 60 bpm, it is called bradycardia. A higher value of HR implies that the heart is beating fast as the result of increased electrical impulses passing through the heart. HR changes, depending on the physical condition of the body. Increased HR is observed during stress/exercise, whereas slow HR is when the body is in rest condition34,35. Sixteen patients (15 males, 1 female, age range: 25–74 years, 11 from the original dataset used for ECG parameter analysis and 5 newly added subjects) having bradycardia and tachycardia and a healthy patient (male, age:45) were screened using commercial metal electrodes. Then, AgNRs-PDMS electrodes were used to check whether they can accurately detect them or not. Raw signals of lead II of one tachycardia, bradycardia, and healthy subjects were plotted to check for signal quality. Mean HR was used for classification into tachycardia (HR > 100 bpm) and bradycardia (HR < 60 bpm).

Arrhythmia detection using R-R interval

Various methods for automated arrhythmia detection have been studied and described in journals36,37,38,39. Among them, some methods rely on beat type detection, others rely on heart rhythm detection and some of them use both the information obtained from the ECG signal. A method described by Tsipouras et al. detects and classifies arrhythmias using R-R interval calculated from the ECG signal. This is used in this work for automated classification of arrhythmic episodes40. The step-by-step method followed for the classification is represented in (Fig. 3a). The model was trained using the MIT-BIH database and tested for accuracy using the MIT-BIH arrhythmia database, MIT-BIH long-term ambulatory database, PTB DB, and PTB XL22,41.

Analysis by PCA and SVM

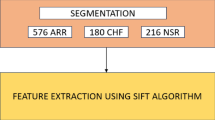

A machine learning model was implemented, as derived from the work Martis RJ et al., to detect and classify arrhythmic beats42,43. The beats were classified as normal, right bundle branch block, left bundle branch block, atrial premature contraction, and ventricular premature contraction.

The MIT-BIH ECG database was used for training, and the database mentioned in the previous section was used to test the model. The heartbeats from the ECG signals were extracted using the Biopeaks algorithm implemented in the Neurokit2 python module, an open-source software. The extracted heartbeats and annotation data were used as the classifier for differentiating the five types of beats. R peak detection and classification of the five types of beats were performed as described below and illustrated in (Fig. 3b).

The ECG signal was filtered using Neurokit2 to remove noise. After filtering, the signal was segmented into individual beats through QRS window detection using the Biopeaks algorithm in Neurokit2. PCA was applied to the extracted heart beats for dimensionality reduction using SciPy and NumPy modules. SVM with a linear kernel was implemented using scikit-learn and trained on the PCA-transformed data. All results were verified using MATLAB.

Evaluation of the results using statistical methods

Statistical analysis was performed to assess the distribution and comparison of ECG signal parameters. The Shapiro-wilk test was used to check the normality of SNR clean signals, SNR powerline interference-excluded signals, and the maximum and mean amplitude of ECG signals, from the metal electrodes and AgNRs-PDMS electrodes, confirming that all data followed a normal distribution (Table S4). Given this, a paired t-test was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics to compare SNR clean signals, SNR powerline interference-excluded signals, PSD values, and ECG amplitude measures. To evaluate agreement between HR datasets from metal and AgNRs-PDMS electrodes, a Bland-Altman plot was generated. Additionally, the Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated to assess the correlation between these two datasets.

Results and discussion

Surface morphology of electrodes

The FESEM image in (Fig. 4a) depicts the rod-shaped geometry of AgNRs formed on a silicon substrate. A uniform layer of AgNRs, with an average diameter of 150 nm and a length of 1 μm was deposited to form the conductive layer. This layer was transferred onto a PDMS film, which has excellent mechanical properties and biocompatibility. Figure 4b displays the fabricated AgNRs-PDMS electrodes, with the bottom side containing the conductive silver layer, while Fig. 4c shows the PDMS layer embedded with silver. Figure 4d, e illustrate commercially available Ag/AgCl electrodes and metal electrodes, which were used for comparison. Figure 4f shows the acquisition of ECG signals by placing AgNRs-PDMS electrodes on the limbs of a subject. The presence of nanorods on the electrode surface significantly increases the surface area, thereby reducing the interface impedance between the skin and the electrode. This reduction in impedance enhances the overall quality of the ECG signals44,45,46.

Skin-to-electrode impedance measurement

The skin-to-electrode impedance was measured for metal electrodes, Ag/AgCl electrodes, and AgNRs-PDMS electrodes by performing an impedance sweep immediately after electrode placement on the skin. The results are graphically represented in (Fig. 4g). The skin-to-electrode impedance of metal electrode ranges from 316.1 ± 31 kΩ (20 Hz) to 10.9 ± 0.6 kΩ (1 kHz), for the Ag/AgCl electrode, 202.7 ± 15 kΩ (20 Hz) to 7.9 ± 0.3 kΩ (1 kHz) and for AgNRs-PDMS electrodes, 77.3 ± 21 kΩ (20 Hz) to 3.7 ± 0.9 kΩ (1 kHz). This implies that the metal electrode has a higher skin-to-electrode impedance. At the same time, it was less for Ag/AgCl electrodes due to the presence of conductive gel, which stabilized the interface between electrode and skin. The AgNRs-PDMS electrode has the least skin-to-electrode impedance compared to the metal and Ag/AgCl electrodes, signifying its ability to measure good quality ECG signals. Dry electrodes generally tend to have higher skin-to-electrode impedance due to the absence of stabilizing gel. Since contact area is inversely proportional to impedance, increasing the electrode’s contact area with the skin can effectively reduce skin-to-electrode impedance47. The stability of the skin-to-electrode interface is a very important parameter which decides the ECG signal quality. Thus, the effect of stability of the skin-to-electrode interface was checked after keeping the electrodes in the same position for 30 min, represented by (Fig. 4h). It was observed that after a duration of 30 min, skin-to-electrode impedance of the metal electrode ranges from 186.7 ± 5 kΩ (20 Hz) to 7.7 ± 0.2 kΩ (1 kHz), for the Ag/AgCl electrode the range was from 88.5 ± 10 kΩ (20 Hz) to 3.7 ± 0.4 kΩ (1 kHz) and for AgNRs-PDMS electrodes it was 58.8 ± 10 kΩ (20 Hz) to 3.9 ± 0.4 kΩ (1 kHz). The skin-to-electrode impedance was reduced for all three types of electrodes after 30 min. In the case of dry electrodes like metal electrodes and AgNRs-PDMS electrodes, sweat produced on the skin surface reduces the skin-to-electrode impedance44. In case of Ag/AgCl elecrodes, the gel stabilized the interface, improving the conductivity. Skin-to-electrode impedance is also affected by the nature of the skin, which differs from person to person. Figure 4i,j represents the comparison of the skin-to-electrode impedance of the three electrodes at 20 Hz and 1 kHz at a time to (immediately after placing the electrodes on the skin) and at time t (after 30 min), respectively.

Images of (a) FESEM image of silver nanorods deposited on silicon substrate. The fabricated dry AgNRs-PDMS electrode (b) bottom side (c) top side (d) commercially used wet Ag/AgCl electrodes (e) commercially used dry metal electrodes (f) Image of ECG acquisition from limb leads of a subject using AgNRs-PDMS electrodes. Graphical representation of variations in impedance spectroscopy for metal electrode, Ag/AgCl electrode and AgNRs-PDMS electrode (g) at time to (h) at time t. (i) Representation of skin-to-electrode impedance values at 20 Hz at time to and time t (j) at 1 kHz at time to and time t.

Performance in terms of SNR

Lead II of the ECG signals was used for SNR calculation, collected from 45 subjects using metal electrodes and AgNRs-PDMS electrodes. The ecg_clean() method from Neurokit2 was used to extract the noise and filtered clean signal from the ECG samples. Figure 5a compares the SNR values across 45 subjects. A paired t-test revealed a one-tailed p-value close to 0, with a t-statistics 9.60. Since the p-value is less than the significance level of 0.05, it indicates a significant difference between the SNR obtained from the two electrodes, with AgNRs-PDMS electrodes demonstrating better performance.

The AgNRs-PDMS electrodes have a higher surface area, making them more susceptible to powerline noise compared to Ag/AgCl or commercial metal electrodes. This study observed that powerline interference contributed significantly to the noise in AgNRs-PDMS electrodes. To account for this, SNR was recomputed after removing powerline interference from the background noise in both metal and AgNRs-PDMS electrodes. A 50 Hz linear digital filter was applied to eliminate powerline noise. Figure 5b compares the powerline interference-removed SNR for 45 subjects. The filtered signal was processed using the ecg_clean() method in Neurokit2 to extract the noise component for SNR calculation. After removing powerline interference, the improvement in SNR for AgNRs-PDMS electrodes was significantly greater than that for metal electrodes. A paired t-test was performed, yielding a t-statistic of 9.56 and a one-sided p-value close to 0. Since p < 0.05, the result is statistically significant, confirming a notable difference in SNR between the two electrodes. The positive t-statistic indicates that AgNRs-PDMS electrodes outperform metal electrodes in signal quality.

The maximum and mean amplitude of lead II ECG signals from 45 subjects were computed for both commercial metal electrodes and AgNRs-PDMS electrodes, as shown in (Fig. 5c, d). A paired t-test was conducted to assess whether the ECG signal quality obtained using AgNRs-PDMS electrodes was comparable to that of metal electrodes. For maximum amplitude, the t-statistic was 3.03, with a two-sided p-value of 0.004. As p < 0.05, the null hypothesis is rejected, confirming that the maximum amplitude of ECG signals from AgNRs-PDMS electrodes is comparable or better than that from metal electrodes. For mean amplitude, the t-statistic was 3.37, with a two-sided p-value of 0.002. Since p <0.05, the null hypothesis is rejected, indicating a significant difference. The positive t-statistic suggests that the signal quality of AgNRs-PDMS electrodes is comparable or better to that of metal electrodes.

The mean amplitude, maximum amplitude, and SNR values of ECG signals before and after applying a linear digital filter for all 45 subjects using both electrodes are provided in Table S1 in the Supplementary Information.

Performance in terms of power spectral density (PSD)

Figure 5e, f illustrates the PSD across different frequency domains for both metal electrodes and AgNRs-PDMS electrodes from a single subject. The signal power in the 49–51 Hz range was noticeably higher for AgNRs-PDMS electrodes compared to metal electrodes, due to increased powerline interference noise resulting from their larger surface area. However, a comparison of the PSD of ECG signals from both electrodes shows that signal power is similarly distributed across all frequency ranges, as depicted in (Fig. 5g, h) for the same subject. A paired t-test was performed to statistically validate these findings. Across all frequency ranges, the two-sided p-value was found to be greater than 0.05, indicating no significant difference in the power components of ECG signals acquired using both electrodes. This confirms that AgNRs-PDMS electrodes capture all relevant ECG features that metal electrodes do, ensuring that signal quality is not compromised despite the absence of gel.

The t-statistics and p-values for the PSD analysis are provided in (Table S5).

Graphical representation of the comparison between metal electrodes and AgNRs-PDMS electrode for 45 subjects for the (a) SNR clean signals (b) SNR signals after removing powerline interference noise (c) maximum amplitude of the acquired ECG signals (d) mean amplitude of the acquired ECG signals. (e) Distribution of power spectral density over various frequency domains in AgNRs-PDMS electrode (f) in metal electrode (g) the power distribution for AgNRs-PDMS electrode (h) for metal electrode for a single subject.

Heart rate comparison

Bland-Altman plot

A Bland-Altman plot, which is widely used in evaluating the performance of two measurements of the same parameter by calculating the mean differences, was represented in (Fig. 6b). The mean difference between the metal electrode and the AgNRs-PDMS electrode was only 0.422 bpm with almost all the data points lying inside limits of agreement i.e. 95% confidence level (± 1.96 SD of difference in measurements between both types of electrodes), which was 3.855 bpm and −3.011 bpm, indicating that the AgNRs-PDMS electrode can detect HR effectively. Since the age range for this study was 20–74, these results indicate that the dry electrodes can be used on adults as well as on elderly patients with high efficacy.

Paired T-test

The t-statistics obtained was 1.617 with a two-sided p-value of 0.113. Since, the obtained p-value was greater than the significance level of 0.05, suggesting that there is no significant difference between HR data sets of metal and AgNRs-PDMS electrodes.

Correlation coefficient

A correlation of 0.99592 (99.592%) was obtained, indicating a strong correlation between data sets of metal and AgNRs-PDMS electrodes, which further concludes that the measurements have high consistency.

Since, the readings were taken when patients were in resting positions in a quiet environment, therefore, large fluctuations of ECG can be avoided. It was observed there were differences in some bpm for a few patients, which can be due to changes in the patient’s cardiac condition (natural variation) or electrode efficacy. Because measuring HR simultaneously using metal and AgNRs-PDMS electrodes is practically impossible, hence HR in the same heart condition was not captured. However, for over 45 subjects, the results of the t-test, Bland-Altman tests, and correlation coefficient for HR comparison indicate that the AgNRs-PDMS detect HR efficiently. The minimum of the R-R interval of metal and AgNRs-PDMS electrodes are represented in (Fig. 6a). The maximum R-R interval is represented in (Fig. 6c). It can be observed that there is no significant difference between the plots, indicating that AgNRs-PDMS can detect various parameters associated with R-R interval and HR. The HR values obtained from 45 subjects are provided in Table S2 in supplementary information.

Detection of tachycardia and bradycardia

Figure 6d compares the ECG signals of subjects with tachycardia, normal ECG, and bradycardia, recorded using AgNRs-PDMS electrodes. The successful detection of tachycardia and bradycardia confirms that the designed electrode can accurately measure HR and effectively identify these conditions, as further illustrated in (Fig. 6e). In subject 9 (tachycardia), when the HR was nearer to 100, some values were less than 100. However, when the graph was plotted as mean ± SD, it did cross 100 bpm. The classification of 16 subjects for tachycardia and bradycardia is provided in Table S3 in the Supplementary Information.

A comparison of ECG waveforms recorded using metal electrodes and AgNRs-PDMS electrodes has been illustrated for two subjects one with a normal and another with an abnormal ECG waveform. The corresponding waveforms are presented in (Fig. 7a, b). The time axis in the graph represents signal with respect to R peak. The ECG template representing the waveform of ECG signals obtained from 45 subjects has been given in the Supplementary Information, section S6. Table 2 shows a comparison of the electrodes used in this study with other dry electrodes.

(a) Plot representing minimum R-R interval in metal electrode and AgNRs-PDMS electrode (b) Bland Altman plot for metal electrode and AgNRs-PDMS electrode. (c) Plot representing maximum R-R interval in metal electrode and AgNRs-PDMS electrode (d) Comparison of ECG signals of tachycardia, normal and bradycardia (e) Representation of mean HR acquired from the ECG signals of various subjects obtained using AgNRs-PDMS electrodes and classification into tachycardia and bradycardia.

Automated arrhythmia detection

The signals obtained using AgNRs-PDMS electrodes were used for automated arrhythmia classification to verify the signal quality. Automated arrhythmia detection algorithms are sensitive to even small deterioration in the quality of the obtained ECG signal. In this paper, the works described by Tsipouras et al.,40 and Martis, RJ et al.42,43 are used to implement the automated classification systems. The models and results are described as follows.

Arrhythmia detection using RR interval

Arrhythmic beat classification and arrhythmia episode detection based on R-R interval calculated from the acquired ECG signals. The method relies on accurate peak detection performed on the signal. In the implementation used here, R peak detection was achieved by using Biopeaks algorithm instead of the Hamilton and Tompkins algorithm proposed in the work by Tsipouras et al.40 Arrhythmic episodes such as premature ventricular contraction, ventricular flutter/fibrillation and 2º heart block were classified using the R-R interval. The classification of arrhythmia is carried out in four main steps. ECG signal was preprocessed to remove baseline wander and powerline interference. Biopeaks algorithm was used to determine R peaks. R-R interval was calculated by measuring the time interval between adjacent R peaks. Arrhythmia classification was performed by applying the set of rules as described in the work. Using a 3-interval sliding window, beat classification was done for premature ventricular contraction, ventricular flutter/fibrillation and 2º heart block. The beat is classified as normal if it does not belong to any of the above categories. Using the results obtained from arrhythmia beat classification, six types of arrhythmic episodes were identified. Ventricular bigeminy, ventricular trigeminy, ventricular couplets, ventricular tachycardia, ventricular flutter/fibrillation, and 2º heart block are the arrhythmic episodes detected by this implementation. Automated classification was performed by using multiple test datasets (MIT-BIH, MIT-BIH long-term ambulatory data, PTB DB and PTB XL). The accuracy obtained using these test data is represented in (Fig. 7c).

Support vector machine (SVM) classifier for arrhythmic beats

SVM was modeled using the MIT-BIH arrhythmia database for classifying 5 types of heartbeats. The heartbeat data was extracted from the ECG signal obtained from the dataset and was used as training data for the SVM. The dimensionality of the data was reduced using PCA. For each QRS complex detected, 200 points were extracted and then reduced to 12 samples using PCA. The steps used for the classifier are described below.

Preprocessing

Signal noise can interfere with the classification of heartbeats. A high pass Butterworth filter of order 5 and pass band frequency of 0.5 Hz and a linear digital filter to remove powerline noise at 50 Hz was used. The ecg_clean() method implemented in the Python module Neurokit2 was used to remove the noise from the ECG signal.

QRS complex detection and R peak identification

The ecg_delineate() and ecg_peaks methods implemented in neurokit2 were used to identify R peaks and QRS intervals. We used the Biopeaks algorithm as implemented in neurokit2 for this purpose. Lead II was used for QRS complex detection60.

Extraction

After detection of the QRS complex using the Biopeaks algorithm, individual’s heartbeats were extracted. After finding the midpoint of the QRS complex, 99 samples were taken before the midpoint, and 100 samples were collected after the midpoint. A total of 200 sample points, including the midpoint of the QRS complex, were extracted per heartbeat and performed beat extraction.

Principal component analysis

PCA is a statistical method for dimensionality reduction. It is particularly useful for high-dimensional data sets which contain a large number of variables. PCA gives the projection of the data in the direction of the highest variance44. PCA involves the following steps (i) covariance matrix calculation of the extracted beats from the ECG signal, (ii) computation of eigenvectors and eigenvalues of the covariance matrix where eigenvectors represent the direction of maximum variance, and the eigenvalues represent the magnitude of variance. The first principal component represents the eigenvector with the highest variance and the maximum eigenvalue, followed by the second and third principal components in descending order. Each eigenvalue is projected in space orthogonally. This model chooses 12 principal components from the first component to include the maximum variability in the data for pattern classification, as represented in (Fig. 7d).

Linear kernel support vector machine

SVM is a machine learning model generally used to solve complex nonlinear classification problems with better accuracy. It classifies the data into different classes by choosing an optimal hyperplane in an N-dimensional space. A maximum margin from the data points in the different classes around the separating hyperplane is obtained. By applying kernel transformations, we can turn a low-dimensional space into a high-dimensional space where classification is carried out, and features are presumed to be linearly separable. Here, linear kernel SVM is used to identify the beats. Automated classification was performed by using multiple test datasets (MIT-BIH, MIT-BIH long-term ambulatory data, PTB DB and PTB XL). The accuracy obtained using these test data is represented in (Fig. 7e).

The beat classification method used is highly dependent on the reliability and accuracy of the acquired ECG signal. We tested the model implemented against the signals collected using metal and AgNRs-PDMS electrodes. Since, the sampling frequency (fs) of the training dataset was 360 Hz and the acquired ECG signal samples had a sampling frequency of 500 Hz, the acquired ECG signal was down-sampled to 360 Hz using Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). The signal amplitude was normalized, and segments were extracted as described. The sample data was annotated by clinicians and compared with the SVM model’s classification. The data of an arrhythmic patient with atrial premature contraction was used for testing in the model with the metal and AgNRs-PDMS electrodes. The specificity obtained for metal electrodes was 98.2%, and for AgNRs-PDMS electrodes was 98.7%.

(a) Illustration of an ECG template comparing metal electrode and AgNRs-PDMS electrode for a normal ECG waveform (b) Illustration of an ECG template comparing metal electrode and AgNRs-PDMS electrode for an abnormal ECG waveform (c) the accuracy obtained using different test datasets for automated classification with R-R interval (d) Representation of the increase in the accuracy of beat classification with an increase in the principal components (e) the accuracy obtained using different test datasets for automated classification with SVM.

Conclusion

In this study, the performance of AgNRs-PDMS flexible dry electrodes was evaluated and compared with commercially available metal electrodes in terms of signal quality and clinical applicability. The study was conducted on a cohort of 50 subjects, including both CVD and healthy individuals. Conducting measurements on a relatively large sample size helps to assess the electrode’s effectiveness across diverse skin types and health conditions, providing a broader understanding of its potential for real-world clinical use. Additionally, the study provides insights into the electrode’s robustness across different skin types and health conditions, emphasizing their practical applicability in routine healthcare monitoring. The AgNRs-PDMS electrodes exhibited a better SNR than metal electrodes in clinical settings for continuous monitoring. PSD analysis confirmed that both electrodes captured all ECG signal components, though powerline noise affected AgNRs-PDMS electrodes due to their larger surface area, highlighting the need for improved electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding. Statistical comparisons of SNR, PSD, HR, and ECG amplitude parameters demonstrate the better efficiency of AgNRs-PDMS electrodes in clinical settings. Unlike commercial wet Ag/AgCl electrodes, these dry electrodes do not require a gel layer, which could have led to higher skin-to-electrode impedance and lower signal quality. However, the high conductivity and large surface area of silver nanorods effectively mitigate this issue. Nevertheless, certain limitations persist, such as low adhesiveness, which can affect signal stability. Sometimes, a medical tape or strap is necessary to ensure stable ECG signals. Automated classification models based on existing works were developed for arrhythmia detection and tested on an arrhythmic patient. Given the high accuracy of the developed classification models, they can be utilized for future arrhythmia detection using AgNRs-PDMS electrodes.

Data availability

MIT BIH arrhythmia database used for training the model are available at https://doi.org/10.13026/C2F305. ECG data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Due to the restrictions on sharing clinical data, the dataset cannot be shared publicly.

References

Button, V. L. & D. S. N. Electrodes for biopotential recording and tissue stimulation. in Principles of Measurement and Transduction of Biomedical Variables 25–76 https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-800774-7.00002-7 (Elsevier, 2015).

Baek, J. Y., An, J. H., Choi, J. M., Park, K. S. & Lee, S. H. Flexible polymeric dry electrodes for the long-term monitoring of ECG. Sens. Actuat. Phys. 143, 423–429 (2008).

Vidhya, C. M., Maithani, Y. & Singh, J. P. Recent advances and challenges in textile electrodes for wearable biopotential signal monitoring: A comprehensive review. Biosensors. 3 https://doi.org/10.3390/bios13070679 (2023).

Xiao, Y. et al. High-adhesive flexible electrodes and their manufacture: A review. Micromachines 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/mi12121505 (2021).

Krieger, K. J. et al. Development and evaluation of 3D-printed dry microneedle electrodes for surface electromyography. Adv. Mater. Technol. 5, (2020).

Vidhya, C. M., Maithani, Y., Kapoor, S. & Singh, J. P. Laser-induced graphene-coated wearable smart textile electrodes for biopotentials signal monitoring. Front. Mater. Sci. 18, (2024).

Hinrichs, H. et al. Comparison between a wireless dry electrode EEG system with a conventional wired wet electrode EEG system for clinical applications. Sci. Rep. 10, (2020).

Tsukada, Y. T. et al. Validation of wearable textile electrodes for ECG monitoring. Heart Vessels 34, 1203–1211 (2019).

Xiao, Z. et al. Atrial fibrillation monitoring based on noncontact capacitive ECG using an integrated microhumidity fabric electrode-sheet sensing scheme. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 72, (2023).

Kumar, G., Duggal, B., Singh, J. P. & Shrivastava, Y. Efficacy of various dry electrode-based ECG sensors: A review. J. Biomedical Mater. Res. Part. A 113 https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.a.37845 (2025).

World-Heart-Report- Confronting the World’s Number One Killer. Geneva, Switzerland. World Heart Federation. (2023).

Feeny, A. K. et al. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in arrhythmias and cardiac electrophysiology. Circ. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 13, E007952 https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCEP.119.007952 (2020).

Trayanova, N. A., Popescu, D. M. & Shade, J. K. Machine learning in arrhythmia and electrophysiology. Circul. Res. 128, 544–566. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317872 (2021).

Shen, C. P. et al. Detection of cardiac arrhythmia in electrocardiograms using adaptive feature extraction and modified support vector machines. Expert Syst. Appl. 39, 7845–7852 (2012).

Yang, W., Si, Y., Wang, D. & Guo, B. Automatic recognition of arrhythmia based on principal component analysis network and linear support vector machine. Comput. Biol. Med. 101, 22–32 (2018).

Yıldırım, Ö., Pławiak, P., Tan, R. S. & Acharya, U. R. Arrhythmia detection using deep convolutional neural network with long duration ECG signals. Comput. Biol. Med. 102, 411–420 (2018).

Chen, C., Hua, Z., Zhang, R., Liu, G. & Wen, W. Automated arrhythmia classification based on a combination network of CNN and LSTM. Biomed. Signal. Process. Control 57, (2020).

Dhyani, S., Kumar, A. & Choudhury, S. Analysis of ECG-based arrhythmia detection system using machine learning. MethodsX 10, (2023).

Murawwat, S., Asif, H. M., Ijaz, S., Imran Malik, M. & Raahemifar, K. Denoising and classification of arrhythmia using MEMD and ANN. Alex. Eng. J. 61, 2807–2823 (2022).

Maithani, Y., Choudhuri, B., Mehta, B. R. & Singh, J. P. Self-adhesive, stretchable, and dry silver nanorods embedded polydimethylsiloxane biopotential electrodes for electrocardiography. Sens. Actuat. Phys. 332, (2021).

Makowski, D. et al. NeuroKit2: A python toolbox for neurophysiological signal processing. Behav. Res. Methods 53, 1689–1696 (2021).

Goldberger, A. L. et al. PhysioBank, physioToolkit, and physioNet components of a new research resource for complex physiologic signals. http://www.physionet.org (2000).

Tereshchenko, L. G. & Josephson, M. E. Frequency content and characteristics of ventricular conduction. J. Electrocardiol. 48 , 933–937 (2015).

Mateo, J., Sánchez-Morla, E. M. & Santos, J. L. A new method for removal of powerline interference in ECG and EEG recordings. Comput. Electr. Eng. 45, 235–248 (2015).

Chatterjee, S., Thakur, R. S., Yadav, R. N., Gupta, L. & Raghuvanshi, D. K. Review of noise removal techniques in ECG signals. IET Signal Proc. 14, 569–590. https://doi.org/10.1049/iet-spr.2020.0104 (2020).

Lenis, G., Pilia, N., Loewe, A., Schulze, W. H. W. & Dössel, O. Comparison of baseline wander removal techniques considering the preservation of ST changes in the ischemic ECG: A simulation study. Comput. Math. Methods Med. (2017).

Singh, B., Singh, P. & Budhiraja, S. Various approaches to minimise noises in ECG signal: A survey. in International Conference on Advanced Computing and Communication Technologies, ACCT 131–137 (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2015).

Kumngern, M., Aupithak, N., Khateb, F. & Kulej, T. 0.5 V fifth-order Butterworth low-pass filter using multiple-input OTA for ECG applications. Sens. (Switzerland) 20, 1–16 (2020).

Thomas, G. & Isaacs, R. Processing, storage and display of physiological measurements. Anaesth. Intensive Care Med. 10 65–69 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mpaic.2008.11.014 (2009).

Colak, O. H. Preprocessing effects in time-frequency distributions and spectral analysis of heart rate variability. Digit. Signal. Process. Rev. J. 19, 731–739 (2009).

Welch, P. D. The Use of Fast Fourier Transform for the Estimation of Power Spectra: A Method Based on time Aver 15 (Aging Over Short, 1967).

Goldberger, J. J., Johnson, N. P., Subacius, H., Ng, J. & Greenland, P. Comparison of the physiologic and prognostic implications of the heart rate versus the RR interval. Heart Rhythm 11, 1925–1933 (2014).

Pike, H. et al. Heart rate detection properties of dry-electrode ECG compared to conventional 3-lead gel-electrode ECG in newborns. BMC Res. Notes 14, (2021).

Qananwah, Q., Ababneh, M. & Dagamseh, A. Cardiac arrhythmias classification using photoplethysmography database. Sci. Rep. 14, (2024).

Chang, W. T. et al. Design of smart clothing with automatic cardiovascular diseases detection. IEEE Trans. Hum. Mach. Syst. 53, 905–914 (2023).

Thakor, N. V., Member, S., Natarajan, A. & Tomaselli, G. F. Multiway sequential hypothesis testing for tachyarrhythmia discrimination. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 41 (1994).

Mray Dokur, Z. ECG beat classification by a novel hybrid neural network. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 66 www.elsevier.com/locate/cmpb (2001).

Hu, Y. H., Palreddy, S. & Tompkins, W. J. A patient-adaptable ECG beat classifier using a mixture of experts approach. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 44 (1997).

Osowski, S. & Linh, T. H. ECG beat recognition using fuzzy hybrid neural network. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 48 (2001).

Tsipouras, M. G., Fotiadis, D. I. & Sideris, D. An arrhythmia classification system based on the RR-interval signal. Artif. Intell. Med. 33, 237–250 (2005).

Wagner, P. et al. PTB-XL, a large publicly available electrocardiography dataset. Sci. Data 7, (2020).

Martis, R. J., Acharya, U. R., Mandana, K. M., Ray, A. K. & Chakraborty, C. Application of principal component analysis to ECG signals for automated diagnosis of cardiac health. Expert Syst. Appl. 39, 11792–11800 (2012).

Martis, R. J., Acharya, U. R. & Min, L. C. ECG beat classification using PCA, LDA, ICA and discrete wavelet transform. Biomed. Signal. Process. Control 8, 437–448 (2013).

Goyal, K., Borkholder, D. A. & Day, S. W. Dependence of skin-electrode contact impedance on material and skin hydration. Sensors 22, (2022).

Niu, X. et al. Fructus xanthii-inspired low dynamic noise dry bioelectrodes for surface monitoring of ECG. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 6028–6038 (2022).

Yun, I. et al. Stable bioelectric signal acquisition using an enlarged surface-area flexible skin electrode. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 3, 1842–1851 (2021).

Li, G., Wang, S. & Duan, Y. Y. Towards gel-free electrodes: A systematic study of electrode-skin impedance. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 241, 1244–1255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2016.10.005 (2017).

Öner, H. & Yüce, H. Align MWCNT/GNPs/PDMS based nanocomposite dry ECG electrodes for ECG recordings. J. Mechatron. Artif. Intell. Eng. 4, 18–26 (2023).

Kim, D. Y. et al. Hybrid 1D/2D nanocarbon-based conducting polymer nanocomposites for high-performance wearable electrodes. Nanoscale Adv. 4, 4570–4578 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc. A pilot study on long-term physiological signal monitoring using anhydrous viscoplastic electrodes. in Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, EMBC 6767–6770. https://doi.org/10.1109/EMBC46164.2021.9630730 (2021).

Lo, L. W. et al. An inkjet-printed PEDOT:PSS-based stretchable conductor for wearable health monitoring device applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 21693–21702 (2021).

Maithani, Y., Mehta, B. R. & Singh, J. P. Implementation of hybrid ag nanorods embedded RGO-PDMS conductive material for flexible and dry electrocardiography sensor. Mater. Lett. X 15, (2022).

Baloda, S., Sriram, S. K., Singh, S. & Gupta, N. Reduced graphene oxide-polydimethylsiloxane based flexible dry electrodes for electrophysiological signal monitoring. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNANO.2024.3459931 (2024).

Garcia-Garcia, L. A. et al. Biocompatible gel-free coconut oil and carbon black electrodes for ECG and respiration measurements. IEEE Sens. J. 23, 23980–23987 (2023).

Maithani, Y., Singh, A., Mehta, B. R. & Singh, J. P. PEDOT: PSS treated cotton-based textile dry electrode for ECG sensing. Mater. Today Proc.62, 4052–4057 (2022).

Gao, X. et al. A moldable PEDOT:PSS dry electrode with excellent epidermal compliance for wearable electrocardiogram monitoring. J. Mater. Chem. C Mater. 11, 13387–13394 (2023).

Masihi, S. et al. Development of a flexible wireless Ecg monitoring device with dry fabric electrodes for wearable applications. IEEE Sens. J. 22, 11223–11232 (2022).

Momota, M. M. R., Morshed, B. I., Ferdous, T. & Fujiwara, T. Fabrication and characterization of inkjet printed flexible dry ECG electrodes. IEEE Sens. J. 23, 7917–7928 (2023).

Ferri, J. et al. A new method for manufacturing dry electrodes on textiles. Validation for wearable ECG monitoring. Electrochem. Commun. 136, (2022).

Brammer, J. Biopeaks: a graphical user interface for feature extraction from heart- and breathing biosignals. J. Open Sour. Softw. 5, 2621 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful and acknowledges Biotechnology Industry Research Assistance Council (BIRAC), Department of Biotechnology, Government of India (Ref. No. BT/AIR01217/PACE-FF) for funding this work. The authors acknowledges All India Institute of Medical Science (AIIMS) Rishikesh for giving the facility for real-time data collection. The author also acknowledges the Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD), India, for providing a junior research fellowship (JRF). The authors thank the Nanoscale Research Facility (NRF) and Central Research Facility (CRF), IIT Delhi, India for providing the characterization facilities and also thank Indian Institute of Technology Delhi for the research facilities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.M. Vidhya: study conception and design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, manuscript preparation. Ghanshyam Kumar: data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, manuscript preparation, Yogita Maithani: review and editing, Bhanu Duggal: study conception, supervision, review and writing, J. P. Singh: study conception, supervision, review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vidhya, C.M., Kumar, G., Maithani, Y. et al. A performance evaluation of silver nanorods PDMS flexible dry electrodes for electrocardiogram monitoring. Sci Rep 15, 15799 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95057-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95057-z