Abstract

The increasing demand for sustainable waste management has driven innovation in the production of activated carbon (AC) from waste. AC’s textural properties, including its surface area (SA), total pore volume (TPV), and micropore volume (MPV), are critical for applications such as gas purification and wastewater treatment. However, the traditional assessment methods are expensive and complex. This study employed machine learning (ML) models to predict AC’s properties and optimize its production process. Random Forest (RF), Decision Tree (DT), Gradient Boosting Regressor (GBR), support vector machines (SVM), and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) were applied along with key input parameters, including raw material type, particle size, and activation conditions. A genetic algorithm (GA) integrated with the GBR model optimizes the synthesis process. The ML models, particularly RF and GBR, accurately predicted SA with R2 values exceeding 0.96. In contrast, the linear regression models were inadequate, with R2 values below 0.6, emphasizing the non-linear relationship between the inputs and outputs. Sensitivity analysis showed that the activation temperature, ratio of the activating agent to carbon, and particle size significantly affected the AC properties. Optimal properties were achieved under activation temperatures between 800 and 900 °C and activating-agent to the carbon ratio 3.8. This approach provides a scalable solution for enhancing AC production sustainability, while addressing critical waste management challenges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global awareness of energy security, environmental conservation, and climate change has prompted nations to prioritize the development and use of renewable energy sources1. Biomass and agricultural waste are the principal renewable sources of carbon-based fuels and chemicals2. Activated carbon (AC), which is known for its porous structure, is widely used for air and gas purification3 and wastewater treatment4. Structurally, AC is a highly porous amorphous carbon material consisting of graphitic layers with sp² hybridization. It possesses a comprehensive pore network, including micropores (< 2 nm), mesopores (2–50 nm), and macropores (> 50 nm), along with a substantial specific surface area of 600–2000 m²/g4. Moreover, AC exhibited significant surface reactivity and superior adsorption capacity. AC is generally produced from lignocellulosic precursors that are abundant in nature, utilizing physical or chemical activation methods. Prevalent raw materials include carbonaceous sources such as coal, wood, and lignite. The substantial surface area and varied pore structure of AC render it a highly efficient adsorbent. AC is extensively employed for pollutant removal, including the adsorption of heavy metals and dyes, owing to its large surface area, abundant functional groups, and adjustable properties. Adjustable surface chemistry further augments its adaptability to particular applications4. Compared to non-renewable petroleum resources, deriving AC from agriculture and forestry waste offers advantages such as environmental sustainability, abundant supply, and cost-effectiveness5. AC is a highly porous adsorbent with substantial adsorption capacity and superior surface reactivity6. Owing to these characteristics, it is widely employed as an adsorbent and catalyst in multiple industries such as manufacturing, pharmaceuticals, water treatment, and agriculture7,8. AC can be produced from various feedstocks including coal, petroleum residues, wood, agricultural by-products, and other carbon-rich materials9. There is increasing interest in utilizing renewable feedstocks, including biomass and agricultural or industrial waste, owing to their potential to diminish the environmental impact and enhance natural resource use efficiency across the product life cycle9. The most common procedure for AC manufacturing consists of two major steps: carbonization and activation. Chemical activation is preferred for producing AC because of its ability to develop various pore sizes, structures, and improved surface areas, which are usually attained with a shorter activation time10. Chemical activation is commonly employed to produce AC11, and the physicochemical properties of the resulting AC are influenced by a range of factors. These factors include feedstock composition, activation parameters (duration, temperature, and heating rate), and ratio of activating agents to carbon source materials12. Producing AC with enhanced textural properties requires an in-depth understanding of how various biomass feedstocks and activation conditions affect these results. Moreover, given the wide range of potential biomass sources, there is a growing need for decision-support tools to aid scientists, engineers, and industry professionals in evaluating different biomass types and refining initial process design strategies tailored to specific feedstocks. The subsequent paragraph provides a concise overview of the pertinent literature regarding the use of machine learning models to predict the textural properties of carbon materials derived from biomass feedstocks.

Scientists have used several approaches to understand the connections between AC sources, processing conditions, and resulting textural properties. However, previous research in this sector has had the following issues: (1) Experimental work requires significant manpower-intensive, time-consuming, and costly experiments13. (2) Although optimization and simple regression analyses have been used to predict the surface area (SA) in previous studies14, the reliability and generalizability of these models are bound by their construction based on a small number of experimental data points. With the advancement of machine learning (ML), several ML systems, such as artificial neural networks (ANN) and random forests (RF), have acquired general acceptance as techniques capable of handling nonlinear issues. Recent research has demonstrated favorable outcomes of ML applications, mainly RF, in producing biochar and activated biochar and utilizing these carbon compounds15. Previous studies have shown that ML models can optimize and guide experimental studies, such as engineering and producing biochar with a higher heating value or carbon storage16. RF and GBR models have been used to forecast and optimize SA, Nitrogen (N) content, and biochar yield17. ML assisted in predicting and designing biochar SA and total pore volume (TPV) using the RF and GBR models18. However, this study focused on biochar rather than on AC. Several studies have attempted to develop predictive models for the AC-derived waste materials. Multilayer feedforward artificial neural network (ANN) models were developed to forecast AC’s total yield and SA of AC from diverse biomass feedstocks via pyrolysis and steam activation19. ML prediction of physical characteristics and N content using three tree-based models of porous carbon from agricultural waste20. Nevertheless, no study has attempted to examine the impact of particle size, activation processing conditions, and N doping on the textural properties of AC derived from waste materials. To the best of our knowledge, no study has developed ML modelling for the prediction and optimization of the texture properties of AC-derived solid waste materials based on particle size, activation processing conditions, and N doping of the resulting texture characteristics (SA, TPV, and micropore volume (MPV)). The subsequent section delves into the significance of this investigation, its objectives, and general methodology.

The textural properties of AC (SA, TPV, and MPV) are crucial for assessing their efficacy in adsorption applications, including water purification, gas storage, and carbon capture. Optimizing and enhancing these textural characteristics is essential for maximizing the adsorption efficiency, selectivity, and overall effectiveness of AC in diverse environmental and industrial applications. It is well known for its porous structure, making it ideal for air and gas purification and wastewater treatment applications. The performance of AC is significantly influenced by its textural properties such as SA, TPV, and MPV.

Traditional experimental approaches for determining the textural properties of activated carbon (AC) are often expensive, time-consuming, and limited in scalability. While previous studies have explored machine learning (ML) techniques for predicting AC properties, they have largely overlooked the combined effects of particle size, activation processing conditions, and nitrogen doping on AC’s textural characteristics. This study introduces a comprehensive ML framework that integrates multiple advanced algorithms—including Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting Regressor (GBR), Decision Tree (DT), Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), and Support Vector Machines (SVM)—to model and optimize AC’s surface area (SA), total pore volume (TPV), and micropore volume (MPV). These models were chosen because they encompass a variety of machine learning techniques, including ensemble learning, decision-based models, kernel methods, and deep learning architectures. These models capture the nonlinear relationships and complex interactions between input parameters, which simpler regression methods fail to address. A Genetic Algorithm (GA) was coupled with the GBR model to optimize the synthesis process, making this study one of the first to systematically integrate ML-based predictive modeling with optimization techniques for AC production. The proposed ML-based approach enhances predictive accuracy and provides a scalable solution for fine-tuning synthesis parameters, thereby minimizing experimental efforts while maximizing AC’s performance for adsorption applications such as carbon capture, water purification, and energy storage.

Methodology

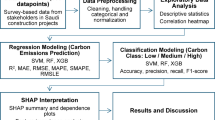

Figure 1 describes the methodology for predicting and optimizing the textural properties of the AC materials. The process begins with data collection, involving a literature review to identify relevant papers on AC derived from various waste materials. Data extraction is then performed to compile useful datasets for analysis. Following this, data preparation is carried out, which includes cleaning, processing, and describing the data using univariate and bivariate statistical analyses. This step ensures the dataset is well-structured and informative for subsequent analysis.

The initial phase of the analysis involved testing linearization techniques to simplify the relationship between variables, employing linear regression, and calculating correlation coefficients to assess the strength of these relationships. This step ensured a clear foundational understanding of the data dynamics before applying more complex models. Subsequently, different ML models were developed and compared. These models were rigorously trained and tested to evaluate their performance in predicting the textural properties of the AC. The hyperparameters were optimized to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of the model, and the model was evaluated using different evaluation matrix parameters, including the coefficient of determination (R2) and average absolute percentage error (AAPE). A sensitivity analysis of the input parameters was conducted using the best-performing ML model. This included Sobol index calculations to quantify each parameter’s effect on the predicted outcomes. The analysis enhanced our understanding of how varying input parameters influence the predicted outcomes, providing valuable insights into the factors affecting the properties of AC. The controlled parameters were optimized in the final stages by integrating the selected ML model with the GA. This combination aimed to refine the synthesis conditions of AC, thereby maximizing desirable textural properties. In addition, the dependency between the two parameters was examined using topography plotting. This graphical analysis helped to visualize the interaction effects between variables and identify the optimal conditions that lead to the best material characteristics, ultimately facilitating the practical application of the findings in industrial settings.

Data collections

The data collected for the models aimed at the prediction and optimization of texture properties, including SA, TPV, and MPV, were analyzed for AC derived from various waste materials, such as petroleum coke21,22,23,24,25, coconut shell26,27,28, date29, rice husk char30, peanut shell char31, pine sawdust32, corn stover33, tea seed shell34, d-glucose35, rotten strawberries36, lotus stalks37,38, spent coffee39, oil residue40, walnut shell41, lemon peel42, bamboo shoot shell43, greasy back shrimp shell44, chitosan45, and banana peel46. AC was prepared via chemical activation using KOH, NaNH2, and K2CO3. Nitrogen (N) - doped and undoped carbon materials are considered. All collected data, along with the corresponding reference and conditions, can be found in the Supplementary file.

Data description

A diverse dataset was compiled from various literature sources, encompassing AC texture properties, including SA, TPV, and MPV, as a function of the activation process and synthesis conditions. A comprehensive data processing procedure was applied to retain only relevant measurements for analysis. Table 1 provides a univariate statistical summary of the input and output parameters from a dataset after processing containing approximately 150 data points. In various studies from which the data were collected, the particle size was defined as a range, as detailed in Table 1. However, in the current study, the mean particle size was used instead of the range. The average particle size (Ps) ranged from 112 to 425 μm, with an average of 168.45 μm, and showed a positively skewed distribution. The ratio of the activating agent to carbon (RAC) varied between 1 and 4, averaging 2.38. (D) is a binary variable with values of either 0 for non-doped materials or 1 for doped materials. The elemental composition showed carbon (C) content (at %) between 48.26% and 96.96%, while hydrogen (H) and N contents varied between 0.17% and 6.01% and 0.17% and 4.27%, respectively. activation temperature (Ta) ranged from 450 °C to 900 °C, averaging around 618.95 °C, with a high positive skew in heating rate (Hr), ranging from 5 to 10 °C/min. The holding time (th) was between 1 and 5 h, with an average value of 1.34 h and high positive skew. The SA varies widely from 502 m²/g to 2532 m²/g, with an average of 1517.29 m²/g, and displays a nearly symmetric distribution. The TPV and MPV also varied significantly, with TPVs ranging from 0.22 to 1.914 cm³/g and MPV from 0.16 to 1.01 cm³/g. The standard deviations for particle size, carbon content, and activation temperature indicated substantial variability, whereas the skewness coefficients revealed that most variables, including particle size, H content, and holding time, showed right-skewed distributions, suggesting long tails. Conversely, SA and MPV exhibited nearly symmetric distributions, indicating a balanced data spread in these measures.

Figure 2 presents a seaborn pair plot that shows cross-plots of the parameters against each other, with the diagonal displaying the individual data distributions. The plots reveal distinct relationships between the input parameters and the output properties. Particle size exhibited a clear negative impact on all three output parameters (SA, TPV, and MPV). Conversely, the ratio of activating agent to carbon positively influences the output. The carbon content and N-doping displayed a positive trend with SA and MPV, but almost no correlation with TPV. N content, on the other hand, revealed an inverse relationship with the MPV. Most input parameters appear to behave independently, showing minimal interdependence. However, both the carbon content and particle size exhibited a positive trend with the activation temperature. The diagonal plots indicate the distribution of each parameter, with SA and MPV displaying nearly symmetrical distributions. In contrast, the other parameters exhibit slightly right-skewed distributions, as reflected by their positive skewness coefficients.

To examine the dependence of the different output parameters on the input parameters, the Pearson correlation coefficient (R) was calculated. The R-values were calculated using Eq. 1.

R = correlation coefficient.

\(\:{x}_{\text{i}}\) = values of the input variables in a sample

\(\:\stackrel{-}{x}\) = mean of values of input variables

\(\:{\text{y}}_{\text{i}}=\) values of the output variable in a sample

\(\:\stackrel{-}{y}\) = mean of the output variable values

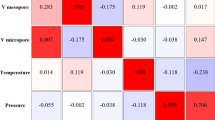

Figure 3a shows a heat map of the correlation coefficients between all parameters, while Fig. 3b summarizes the correlation coefficients between the different output and input parameters. The analysis revealed that certain synthesis parameters have a pronounced impact on the textural properties of the synthesized porous carbon materials, while others exhibited minimal influence. The particle size demonstrated a strong negative correlation with SA (-0.13), TPV (-0.18), and MPV (-0.29), indicating that smaller particle sizes favor the formation of a highly porous structure. This is likely due to the increased surface-to-volume ratio of the smaller particles, which enhances the overall porosity of the material, making it more suitable for applications such as carbon capture. The Ratio of Activating Agent to Carbon is another crucial parameter, showing a positive correlation with SA (0.56), MPV (0.56), and TPV (0.44). This suggests that higher levels of activating agents promote the development of a more interconnected pore network, leading to an enhanced adsorption potential and larger SA, both essential for gas storage and separation efficiency.

N doping also showed a significant positive relationship, particularly with MPV (0.41), and a moderate impact on SA (0.13), which can enhance the formation of stable micropores. Carbon content (C) had a similar effect, positively correlating with SA (0.29) and MPV (0.37). This suggests that increasing the carbon content supports microporosity development without notably affecting the overall pore volume, thereby providing a pathway to optimize material performance, specifically for microporous applications. Conversely, N content showed a negative correlation with MPV (-0.28) and a slight inverse trend with SA (-0.21), implying that higher N levels may reduce microporosity.

Parameters such as the Activation Temperature positively impacted SA (0.25) and MPV (0.24). In contrast, the Heating Rate and Holding Time exhibited almost no correlation with the SA, TPV, or MPV. Their weak influence suggests that these parameters do not significantly alter the pore characteristics of the material within the tested range, indicating that they are less critical for tailoring the porous properties of carbon for specific applications.

Model development

The highlighted part in Fig. 1 illustrates the step-by-step procedure for developing ML models. The process begins with preparing, collecting, and processing relevant data to ensure high-quality inputs for model building. The min–max normalization approach was used to ensure consistency across all features, where the normalized values of each feature varied from 0 to 1. The data were randomly split into training and testing sets using ratios ranging from 60/40 to 80/20 to evaluate the performance of the model under different conditions. During the training stage, the hyperparameters were optimized to enhance accuracy. The split ratio was then adjusted during the testing phase to further refine the model’s performance and ensure optimal generalization. After testing, a sensitivity analysis was performed to examine the influence of each input parameter on the output predictions, providing insights into parameter importance. Finally, the process includes an optimization step, in which the developed model is integrated with a GA to optimize the input parameters for improved output performance. This comprehensive workflow ensured that the model was robust, accurate, and applicable to various input scenarios.

The model evaluation matrix consisted of the coefficient of determination (R2) and average absolute percentage error (AAPE). The R2 and AAPE were calculated using Eqs. 2–547.

Where SSE is the summation of residual squares, n is the number of data points, \(\:{y}_{i}\) is the actual data value, \(\:{\widehat{y}}_{i}\) is the predicted data value, and \(\:{S}_{YY}\) is the summation of squares of data variation to the data mean value.

To accurately predict each target parameter (SA, TPV, and MPV) in the study of AC derived from waste materials, this study implemented a multifaceted approach using various ML models. The necessity for precision in predicting the textural properties of AC underscores the need for comprehensive application of advanced analytical models that can handle the complexities of the dataset and provide reliable predictions. Multiple machine learning algorithms were assessed for their efficacy in predicting specific target parameters. Random Forest (RF), Decision Tree (DT), Gradient Boosting Regressor (GBR), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) were selected as they represent a diverse range of machine learning techniques, covering ensemble learning, decision-based models, kernel methods, and deep learning architectures. These models were chosen based on their established effectiveness in similar predictive tasks and their ability to balance interpretability, computational efficiency, and predictive accuracy. These algorithms were selected based on their proven capabilities for various ML challenges, particularly those involving complex and high-dimensional data. Following are more details about each ML model and its capabilities.

A decision Tree (DT) model was employed for straightforward interpretability. A DT clearly visualizes the decision-making process from the root to the leaves, showing how input features affect outputs. This transparency is invaluable in scientific studies where understanding the influence of each parameter is as crucial as the accuracy of the predictions. DT models are particularly useful in scenarios where stakeholders require clear explanations of decisions, thus supporting the interpretability of complex machine learning models in real-world applications48. The splitting criterion is based on impurity measures, such as Entropy or Gini Index, which assess how well a feature divides the dataset. The tree grows by selecting the attribute that maximizes information gain, ensuring the most informative splits at each level. Entropy (H) measures the impurity or unpredictability in a dataset, whereas The Gini Index measures how often a randomly chosen element is incorrectly classified if labeled randomly48.

Information Gain (IG) can be calculated as follows

Where:

-

\(\:{p}_{i}\) denotes the probability of class i in a given node.

-

H is the entropy of the dataset,

-

C is the number of classes,

-

IG is the improvement in information content due to a split,

-

\(\:Sv\) is the subset of data where attribute A takes value \(\:v\),

-

\(\:\frac{\left|Sv\right|}{\left|S\right|}\) is the proportion of data belonging to subset \(\:Sv\).

The Random Forest (RF) algorithm was predominantly utilized for its ensemble method, enhancing prediction accuracy. RF improves the model performance by integrating multiple decision trees, which reduces the risk of overfitting by averaging the predictions from various trees. This method is particularly effective in managing the high-dimensional data characteristics of textural properties in materials science. RF’s ability of RF to handle large datasets with multiple input variables makes it ideal for predicting properties such as SA, TPV, and MPV, where interactions between variables can be highly nonlinear and complex49. Random Forest is an ensemble learning algorithm that constructs multiple decision trees and combines their outputs to improve the prediction accuracy and reduce overfitting. Each tree was trained on a randomly sampled subset of the data, and the final prediction was obtained by averaging the outputs of all trees in regression tasks or majority voting in classification tasks50.

Where:

-

\(\:\widehat{y}\) denotes the predicted output.

-

NNN is the number of decision trees,

-

\(\:{T}_{i}\left(x\right)\) represents the prediction from the ith tree.

The Gradient Boosting Regressor (GBR) was selected for its proficiency in handling complex non-linear interactions between variables. The GBR builds an ensemble of weak prediction models, typically decision trees, sequentially, in which each subsequent model attempts to correct the errors of its predecessors. This technique gradually improves the prediction accuracy and is highly effective in reducing bias and variance, making it suitable for intricate datasets involved in predicting the textural properties of AC derived from waste materials51. Gradient Boosting is an iterative ensemble method that builds a sequence of weak learners, typically decision trees, where each new model corrects the residual errors of the previous model. This approach minimizes the loss function using gradient descent, resulting in an optimized predictive model52.

Where:

-

\(\:{\text{F}}_{m}\text{}\left(\text{x}\right)\) is the model at iteration mmm,

-

\(\:{\text{F}}_{m-1}\text{}\left(\text{x}\right)\) is the previous iteration model,

-

\(\:{\text{h}}_{m}\text{}\left(\text{x}\right)\) is the weak learner (decision tree),

-

\(\:{{\upgamma\:}}_{m}\)is the learning rate.

Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) were included in this study because of their exceptional capability to model the complex non-linear relationships between inputs and outputs. With their deep-learning capabilities, ANNs can learn high-level features from data using architectures that mimic human neural networks. This makes them exceedingly effective for tasks in which the relationship between the input parameters and the desired output is intricate and not easily discernible by simpler ML models. ANNs have shown great promise for accurately predicting material properties that depend on subtle interactions among multiple factors53. An ANN consists of layers of neurons with activation functions. The network learns by adjusting the weights using a backpropagation algorithm to minimize errors.

Where:

-

Z is the weighted sum of inputs,

-

W is the weight matrix,

-

X is the input feature vector,

-

b is the bias,

-

σ(Z) is the activation function (e.g., ReLU, Sigmoid, Tanh).

The support vector machine (SVM) model was also explored in this study owing to its renowned capability for regression and classification tasks. The SVM finds a hyperplane that best divides a dataset into classes or predicts values with a maximum margin, thus ensuring greater model generalization. For regression tasks, SVM uses a similar approach to fit the error within a certain threshold, making it particularly useful for datasets in which the prediction must be accurate and robust against potential outliers. Support Vector Machines (SVMs) are supervised learning models that determine the optimal hyperplane that maximizes the margin between different classes in a dataset. The fundamental idea is to map the input data into a higher-dimensional feature space, where a linear decision boundary can be established. The optimal hyperplane is defined by support vectors, which are the closest data points to the boundary54. The optimal hyperplane is given by:

Where:

-

w is the weight vector that defines the hyperplane,

-

x is the input feature vector,

-

b is the bias term,

-

The decision boundary is given by \(\:f\left(x\right)=0\).

SVM for regression tasks, the objective is to minimize the prediction error while maintaining a margin \(\:\in\:\):

C is the regularization parameter that controls the trade-off between maximizing the margin and minimizing misclassification, \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{i},\:and\:{\epsilon\:}_{i}^{*}\:\)are slack variables for violations.

The final optimization process integrated a GA with a developed model to refine the prediction of the AC properties by optimizing the input parameters. This process involves initializing a diverse population, where each individual represents a unique set of input parameters55,56. These individuals are assessed for fitness and quantified based on how well the output properties satisfy the desired performance criteria. A high fitness score indicates better performance and guides the selection process. In the GA, selection is based on a tournament style, where the best among a randomly chosen subset of the population is selected for reproduction. This selection process ensures that traits from higher-performing individuals are carried to the next generation while maintaining genetic diversity. Crossover, the next step, blends traits from two-parent individuals to produce new offspring, allowing the algorithm to explore new parameter combinations that may yield better results. Mutation introduces random, small-scale changes to the offspring’s traits, preventing the algorithm from becoming stuck in local optima and encouraging solution space exploration. This is particularly useful for navigating complex landscapes of model responses where the optimal conditions are not immediately apparent. As generations progress, the population theoretically evolves towards an optimal set of input parameters, with the GA iterating through cycles of selection, crossover, and mutation until a stopping criterion is met, such as the maximum number of generations or a plateau in fitness improvement.

Results and discussion

Testing linearization

A linear regression (LR) model was applied to assess the linear relationship between the input and output variables SA, TPV, and MPV. Figure 4 shows the cross plots of the predicted versus actual values for each output variable using both the training and testing datasets. The results demonstrated a significant discrepancy between the predicted and actual values, indicating that the LR model failed to capture the relationships within the data accurately. This misalignment suggests that the relationship between the inputs and outputs is likely non-linear and complex, underscoring the limitations of a simple linear model for predicting these properties. Consequently, more sophisticated ML models are necessary to effectively model underlying interactions for accurate predictions.

model for both training and testing datasets.

Machine learning models results

Several ML models, including RF, GBR, DT, SVM, and ANN, have been developed to predict the SA, TPV, and MPV. Figure 5 highlights the evaluation matrix, including R2 and AAPE, for the different models for predicting SA values at different splitting ratios. The optimal training/testing split ratio was determined to be 70/30, offering the best balance between model learning and validation performance. This ratio ensures the model is trained on sufficient data while preserving an adequate testing set for robust evaluation. At this split, RF achieves its highest testing R2 accuracy (0.957) while maintaining strong training performance (0.994), but with an AAPE of 10 on the test set, indicating some variance in prediction accuracy. Similarly, GBR reaches its peak testing accuracy (0.964) with minimal overfitting (training R2: 0.997), while its AAPE for testing remains at 6, making it a strong contender for reliable predictions. DT exhibits notable improvement at the 70/30 split, with a testing R² of 0.95 and a substantial drop in AAPE from 8.9 (60/40) to 5, demonstrating improved generalization. ANN and SVM also maintain high testing R2 values (0.963 and 0.96, respectively), while their AAPE values remain at 7 and 5, respectively, reflecting stable prediction accuracy. Overall, the 70/30 split provides the best trade-off between R2 accuracy and AAPE, minimizing overfitting while ensuring strong predictive capability across all models, making it the most balanced choice for robust AC texture property prediction. A similar performance was observed in the case of TPA and MPV prediction models.

Each model underwent hyperparameter tuning to maximize the predictive performance, and the optimal hyperparameters are summarized in Table 2. For the RF model, the best results were achieved using “sqrt” for maximum feature selection, a maximum depth of 25, and 125 estimators. For the GBR model, an optimal learning rate of 0.21, 50 estimators, and a subsample rate of 0.5. The DT model performed the best, with a maximum depth of 9 and “sqrt” as the feature selection method. For ANN, the optimal configuration included a sequential network architecture with 4 nets, 64 neurons per layer, and a combination of ‘relu’ and ‘tanh’ activation functions. Similarly, A grid search was utilized to optimize the SVM hyperparameters, and the best performance was achieved using an RBF kernel with C set to 5000 and gamma set to ‘scale. ’ These optimized settings are crucial for improving the predictive accuracy of each model and ensuring robust predictions tailored to each output parameter of the synthesized porous carbon materials.

Figure 6 presents cross-plots of the actual versus predicted SA values for the developed ML models evaluated on the training and testing datasets. All models demonstrated high performance, with R2 values exceeding 0.95 and AAPE values remaining below 10% across both datasets. Most data points in these cross-plots align closely along the 45-degree line, indicating accurate predictions of SA as a function of element composition and synthesis parameters.

Among the models, GBR and ANN exhibited the best performance, with R² values of 0.997 (Fig. 6c) and 0.980 (Fig. 6g) for the training set and 0.964 (Fig. 6d) and 0.963 (Fig. 6h) for the testing set, respectively. This balance suggests that both the GBR and ANN models generalize well to new data without significant overfitting. The SVM demonstrated comparable results to GBR and RF, achieving R2 scores of 0.993 (Fig. 6i) in training and 0.96 (Fig. 6j) in testing, with slightly lower errors of 1% AAPE in training and 5% in testing. In contrast, the Decision Tree (DT) and Random Forest (RF) models displayed slightly more overfitting, with R2 values dropping from 0.988 (Fig. 6e) to 0.959 (Fig. 6f) for DT and from 0.994 (Fig. 6a) to 0.957 (Fig. 6b) for RF. This slight discrepancy in DT and RF indicates that, while they capture trends effectively during training, their predictive accuracy slightly decreases on unseen data. Table 3 summarizes the performance indicators of the R2 and AAPE values for the predicted surface areas from the different ML models.

To assess the effectiveness and reliability of the predictive model for estimating the SA of AC materials, a 10-fold cross-validation method was applied, which represents a substantial improvement over the previously used random-subsampling approach. This method involved segmenting the dataset into ten separate parts or folds, where each segment was alternately used as a validation set, while the others were employed for training. This procedure was repeated until each fold was used exactly once for validation, providing a thorough assessment of model performance across the entire dataset. The outcomes of this meticulous validation process are illustrated in Fig. 7a, which shows a cross-plot of the predicted values against the actual values from the validation sets using the GBR model. The plot reveals a precise alignment of the data points along the 45-degree reference line, indicating excellent accuracy and consistency of the model across different data segments. This precise alignment underscores the robust generalization ability of the model. Figure 7b shows the R2 statistics for each fold, where the values fluctuated between 0.91 and 0.99, with an average of 0.96, and a low standard deviation of 0.03. These results confirm the high performance of the model and demonstrate its ability to generalize effectively without overfitting, thereby underscoring its reliability under diverse conditions.

Figure 8 presents crossplots of actual versus predicted TPV values from various ML models, revealing the effectiveness of each model in capturing the relationship between the input parameters and TPV across the training and testing datasets. Table 4 shows that all models performed well, achieving R2 values above 0.93 and an AAPE below 10% for both datasets, demonstrating effective predictive capability with some variation among models. The GBR achieved outstanding results, with an R2 of 0.997 (Fig. 8c) for training and 0.96 (Fig. 8d) for testing, and low AAPE values (3% for training and 7% for testing). Its close alignment with the diagonal in both datasets indicates strong predictive accuracy and balanced generalization, positioning the GBR as a top performer. The ANN also performed accurately, particularly on the testing data, with an R² of 0.966 (Fig. 8h) and an AAPE of 8%.

RF showed strong performance on the training set (Fig. 8a) (R2 = 0.994 and AAPE = 3%), but a slight drop in accuracy on the testing set (Fig. 8b) (R2 = 0.949, AAPE = 9%). This deviation, along with points that stray further from the diagonal in the testing data, suggests mild overfitting, because the RF appears to have adapted too closely to the training data. DT exhibited a more pronounced overfitting, with a nearly perfect R2 of 0.999 (Fig. 8e) on training but a reduced R² of 0.935 (Fig. 8f) during testing. Its AAPE increased from 1% during training to 6% during testing, indicating limited generalization because of its tendency to fit too closely with training nuances. SVM displayed marginally lower performance than RF, ANN, and GBR in predicting TPV, with R2 scores of 0.96 (Fig. 8i) in training and 0.94 (Fig. 8j) in testing, and AAPE values of 12% and 11%, respectively. However, it maintained a consistent balance between the training and testing results, indicating no overfitting issues, unlike the DT model in which the training performance significantly exceeded the testing performance. This consistent behavior of the SVM could be attributed to its ability to generalize better, avoiding the common pitfall of overfitting observed in more complex models.

To evaluate the effectiveness and reliability of the predictive model for estimating the TPV of AC materials, 10-fold cross-validation was implemented using the GBR model. The results in Fig. 9a show a cross-plot of the predicted versus actual values, revealing a precise alignment along the 45-degree reference line. This alignment indicated excellent accuracy and consistency across the data segments, highlighting the robustness of the generalization ability of the model. Figure 9b summarizes the R2 statistics for each fold, which ranged between 0.91 and 0.99, with an average of 0.968 and a low standard deviation of 0.03. These results confirmed the high performance and effective generalization of the model, demonstrating its reliability under diverse conditions.

Different ML models were similarly applied to predict MPV based on the input parameters. Figure 10 presents cross plots for the actual versus predicted MPV values, highlighting each model’s predictive capabilities across the training and testing datasets. Table 5 summarizes the R2 and AAPE values of the different ML models for the actual versus predicted MPVs. GBR and ANN emerged as the top-performing models for predicting MPV, with GBR demonstrating balanced performance across both datasets and ANN achieving the highest testing accuracy. Specifically, the GBR achieved R2 values of 0.995 (Fig. 10c) for training and 0.951 (Fig. 10d) for testing, with low AAPE values of 3% for training and 7% for testing. Conversely, ANN outperformed the other models on the testing dataset, achieving the highest R2 value of 0.987 (Fig. 10h) and a minimal AAPE of 3%. RF and DT performed well during training, with R2 values of 0.992 (Fig. 10a) and 0.999 (Fig. 10e), respectively, and AAPE values of 5% and 0.1% for RF and DT, respectively. However, they exhibited a decline in accuracy during testing, which was indicative of mild overfitting. RF showed an R2 of 0.930 (Fig. 10b) with an AAPE of 9%, whereas DT had an R2 of 0.913 (Fig. 10f) and an AAPE of 5% for the testing dataset. This decline suggests that while RF and DT captured the training data well, they struggled to generalize effectively to new data compared to GBR and ANN. Similar to the TPV predictions, the SVM model demonstrated consistent but slightly lower performance in predicting MPV, achieving R2 scores of 0.94 (Fig. 10i) for training and 0.93 (Fig. 10j) for testing and an Average Absolute Percentage Error (AAPE) of 13% for both the training and testing phases.

To evaluate the accuracy of the predictive model in estimating the MPV of AC materials, 10-fold cross-validation was performed using the GBR model. The results are shown in detail in Fig. 11a, which displays a cross plot of the predicted versus actual values. The data points align closely with the 45-degree reference line, demonstrating the excellent accuracy and consistency of the model across different data segments and highlighting its robust generalization capabilities. Figure 11b provides an overview of the R2 statistics for each fold, showing values ranging from 0.89 to 0.99, with an average of 0.958 and a low standard deviation of 0.039. These figures confirm the high performance and effective generalization of the model, attesting to its reliability under diverse conditions.

The results of the different ML models showed that RF, GBR, and ANN demonstrated superior performance over DT and SVM because of their inherent characteristics that mitigate common issues such as overfitting and underperformance. In particular, the GBR model presented a higher performance without overfitting problems, as highlighted by the 10-fold cross-validation process using different models to predict all AC texture properties.

RF and GBR, both ensemble learning methods, leverage multiple learning algorithms to obtain better predictive performance, thus reducing the overfitting commonly observed in DT. By aggregating the results of numerous decision trees, RF improves accuracy and stability without substantially increasing the risk of overfitting50. Similarly, GBR systematically combines weak predictive models to form a strong learner, thereby iteratively enhancing the performance52. ANNs excel in capturing complex patterns in large datasets owing to their deep learning capabilities and multiple layers of non-linear processing units. This makes them particularly adept at handling nonlinear relationships that SVMs, which typically excel in high-dimensional space, might struggle with when the data lacks a clear margin of separation57. Although influential in classification tasks and high-dimensional spaces, SVMs often exhibit a slightly lower performance in regression or complex nonlinear prediction scenarios than RF, GBR, and ANN. This is partly because of their reliance on defining a decision boundary that is not always optimal for every dataset, particularly those with overlapping classes or intricate patterns54. Different strategies can be implemented in future studies to enhance model robustness and ensure consistent performance across the training and testing phases. These include increasing the diversity and size of the training dataset to better capture the variability inherent in real-world applications and employing regularization techniques to penalize excessive model complexity. Additionally, integrating 10-fold cross-validation during model development helps assess the model’s ability to generalize beyond the training data by repeatedly validating the model’s performance across ten subsets. This method reduced the likelihood of overfitting and ensured reliable performance metrics. Moreover, the continuous monitoring of model performance and iterative tuning of hyperparameters based on new data can improve the reliability of the models in practical applications.

Sensitivity analysis

As the GBR model showed the best performance, it was used to conduct a sensitivity analysis of the input parameters on the texture property (SA, TPV, and MPV) values. In this analysis, the GBR model is employed to predict the output parameters based on random values of the input parameters within the range of the data listed in Table 1. A Sobol sensitivity analysis was used to assess the relative influence of each parameter on the predicted parameters. Sobol’s method is beneficial for quantifying both the first-order and total-order sensitivities. First-order indices (S1) indicate the direct effect of a single parameter on the output, whereas total-order indices (ST) measure the combined effect of a parameter, including its interactions with other parameters. This sensitivity analysis helps to identify which input factors significantly affect the prediction of porous carbon material properties, guiding future experimental and modeling efforts.

Figure 12 shows the S1 and ST bar charts used to predict texture properties. For SA predictions, the analysis underscored carbon content (C) as the most influential factor, with a significant first-order S1 of 0.366 and ST of 0.408, indicating a predominant influence on variability. Similarly, the activating agent-to-carbon ratio markedly affected the SA, as highlighted by an S1 of 0.187 and an ST of 0.284. The activation temperature also demonstrated considerable influence, with an ST of 0.150. In the case of TPV, the activation temperature emerged as the most critical parameter, with S1 of 0.416 and ST of 0.424, reflecting its substantial effect on the output variance. The hydrogen content (H) and ratio of activating agent to carbon also showed significant first-order effects, with S1 values of 0.193 and 0.121, respectively. MPV, the carbon content again proved highly impactful, with an S1 of 0.271 and an ST of 0.313, whereas the particle size and activation temperature also showed notable effects on the model predictions. This underscores the critical role of these parameters in governing the properties of porous materials, especially in carbon capture and hydrogen storage applications.

The correlation coefficient shown in Fig. 13 illustrates the linear relationship between the AC material properties and input parameters. The correlation coefficients elucidate these relationships, revealing positive correlations between carbon content and activation temperature with all output parameters, suggesting their pivotal role in enhancing AC’s textural properties of AC. Conversely, negative correlations between particle size and N content across different models indicated a reduction in pore volume, highlighting the complex interactions within the synthesis parameters.

Sensitivity analysis showed that the ratio of activating agent to carbon significantly influenced SA. The etching effect of the activation agent acts as an oxidizing agent, resulting in the formation of pores in the carbon skeleton58. Choosing the right impregnation ratio is crucial because it affects the porosity and prevents carbon skeleton collapse from over-activating agents59. Generally, a porous carbon structure is formed by improved chemical etching during activation. The activation temperature is critical for determining the surface area and porosity of the samples; however, higher temperatures can cause the carbon skeleton to collapse, thereby reducing the carbon texture properties. It has been reported that increasing the activation temperature increases SA and TPV32. According to the sensitivity analysis illustrated in Fig. 12, the activation temperature was the most relevant factor for the three target attributes and had a greater influence on SA and TPV. The significance of the activation temperature has been previously investigated20. As the activation temperature increased, the holes formed expanded further, increasing the SA, TPV, and the average pore size. An unusually high activation temperature causes the pore structure to collapse or shrink, decreasing the porosity, SA, and micropores59,60. Thus, the activation temperature considerably affects the morphological structure of the carbon. Furthermore, increasing the activation temperature and amount of activator resulted in a more intense reaction, causing severe etching, greater microporous pore size, and the production of additional mesopores. It has also been reported that increasing the chemical-to-carbon ratio increases the proportion of micropores22. It has also been found that increasing the activation temperature and chemical-to-carbon ratio increases SA, TPV, and MPV21. The particle size substantially affects the SA, TPV, and MPV of AC61. Smaller particles have a larger SA owing to their higher surface-area-to-volume ratio61. Decreasing the particle size also enhances access to internal pores, frequently increasing TPV. Furthermore, smaller particles may expose more micropores, thereby producing a larger MPV61. Thus, regulating the particle size is critical for maximizing the textural properties of the AC. The carbon content affected the textural properties of AC. For instance, higher impurities and ash yield lower carbon content in less-developed porous structures and lower SA10. During activation, the biomass feedstock ash content had a greater impact on SA. This could be because the amount of ash in the biomass feedstock directly affects pore formation during the activation process10. The N content influenced AC’s textural properties of the AC (SA and MPV) (Fig. 12). N-containing materials can act as catalysts during activation, affecting the pore formation kinetics and processes62.

Optimizing the synthesis parameters

The textural properties of AC (SA, TPV, and MPV) are important in determining its performance in adsorption applications such as water purification, gas storage, and carbon capture63. Therefore, balancing and improving these textural properties is critical for maximizing AC’s adsorption efficiency, selectivity, and overall efficacy of AC for various environmental and industrial applications. A large SA allows more active sites for adsorbate molecules to adhere to, boosting the adsorption capacity of the carbon64. TPV indicates the amount of space within the carbon structure that can be used to store or trap molecules, allowing AC to contain more adsorbates65. In particular, the MPV is critical for trapping tiny molecules because micropores provide a larger interior surface in a limited volume66. To produce AC with improved textural properties, it is necessary to understand how various biomass feedstocks and activation conditions affect these properties. Therefore, it is essential to optimize the AC synthesis process to improve textural properties.

The GA was integrated with the developed Gradient Boosting Regressor (GBR) models to optimize the AC synthesis process of AC to enhance SA, TPV, and MPV. The genetic operations utilized included tournament selection for reproducing the best candidates, blend crossover with a 50% mixing rate for combining genetic materials, and a customized mutation function designed to toggle discrete parameters and apply bounded Gaussian mutations to continuous parameters. The fitness function is directly linked to the output of the ML model, which the GA strives to maximize. The process involves the iterative selection of the top-performing individuals from the population, application of genetic operations, and evaluation of new generations to refine the solutions over a designated number of generations. Figure 14 shows the progression of this GA, showing the increase in maximum fitness over 40 generations. The rapid improvement in fitness from generations 0 to 15 indicates an effective exploration of the solution space, where various potential solutions are assessed, and the most promising ones are replicated. Beyond generation 15, the increase in fitness levels was off, suggesting a plateau that began around generation 20 and continued until generation 40. This plateau indicated that the algorithm may have attained a near-optimal or optimal solution. Table 6 presents the optimized input parameters and their corresponding outputs for AC properties.

In the optimization process, controlling parameters such as the particle size, ratio of activating agent to carbon, activation temperature, heating rate, and holding time were optimized for a specific AC material with a defined carbon composition. The values for the composition parameters (C, H, and N) were set to medians of 80, 2, and 1 wt%, respectively, while the controlled parameters varied within the minimum and maximum ranges specified in Table 1. This optimization resulted in a SA of 1775 m²/g, a TPV of 1.4 cm³/g, and a MPV of 0.88 cm³/g.

Two-factor partial dependence plots were used to demonstrate the impact of the combination of these two factors on the properties of the porous materials. This analysis aimed to examine the most significant parameters identified from the sensitivity analysis, including the activation temperature, ratio of the activating agent to carbon, particle size, and holding time. During each evaluation, these two parameters were varied within the ranges provided in Table 1, whereas the other parameters were assumed to be at their optimum values, as outlined in Table 6.

Figure 15 illustrates the influence of the activation temperature and ratio of activating agents on various material properties. The data show noticeable improvements in material properties as the activation temperature increases up to 850 °C, specifically within the optimal range of 800 to 900 °C. The SA increased from approximately 1200 to 1700, TPV rises from 0.4 to about 1.4, and MPV improved from 0.55 0.83. A pronounced increase was observed with increasing activation temperature, whereas the trend related to the ratio of the activating agent was more gradual.

Similarly, Fig. 16 depicts the variations in material properties as a function of particle size and holding time. A negative trend was noted for particle size, where smaller sizes correlated with higher property values, particularly between particle sizes of 74 and 150 μm. The holding time significantly affected the SA and MPV, with optimal properties observed between 3 h and 4 h.

These optimum conditions were based on the GBR model developed using a range of input parameters, as listed in Table 1. Hence, future studies should examine the performance at lower particle sizes (outside the current study ranges).

Conclusions

Different advanced ML models were developed in this study to predict and optimize the AC texture properties as a function of the raw material type, particle size, and activation processing conditions. Sensitivity analysis was performed using the developed ML model to evaluate the impact of the input parameters. The key findings of this study are as follows.

-

The Gradient Boosting Regressor (GBR), artificial neural network (ANN), and Random Forest (RF) models demonstrated high predictive accuracies, with R2 values exceeding 0.96.

-

Support Vector Machines (SVM) exhibited consistent but slightly lower performance, particularly in predicting TPV and MPV.

-

The Decision Tree model revealed a tendency to overfit, particularly for TPV and MPV predictions, indicating the need for careful model selection and parameter tuning to balance the accuracy and generalizability.

-

Sensitivity analysis identified carbon content, activation temperature, and particle size as the most influential parameters affecting the textural properties of the activated carbon.

-

The integration of GA with GBR optimizes the synthesis processes for activated carbon, achieving ideal textural properties at activation temperatures of 800–900 °C, and C and ratio of activating agent to carbon of 3.8. This optimization is based on the parameter ranges used in this study, and the optimal results may vary if the input values extend beyond these limits.

-

Future research should consider collecting additional data related to different routes for chemical activation, considering feedstock with low particle sizes, and validating the developed ML models with experimental data.

Machine learning streamlines the development of AC with enhanced textural properties, and promises to revolutionize waste management practices by transforming waste into valuable adsorbents. In addition, Combining ML models with GA offers substantial benefits for industrial scalability. It reduces the experimental burden by predicting outcomes before physical trials and identifying optimal conditions faster and more accurately.

Data availability

All collected data, along with the corresponding references and conditions, can be found in the Supplementary file.

Abbreviations

- AC:

-

Activated carbon

- ANN:

-

Artificial neural networks

- C:

-

Carbon content (at%)

- D:

-

Nitrogen doping

- DT:

-

Decision tree

- GA:

-

Genetic algorithms

- GBR:

-

Gradient boosting regressor

- H:

-

Hydrogen content (at.%)

- Hr :

-

Heating rate (°C/min)

- ML:

-

Machine learning models

- MPV:

-

Micropore volume (cm3/g)

- N:

-

Nitrogen content (at.%)

- n:

-

Number of data points

- Ps:

-

Particle size (µm)

- R:

-

Correlation coefficient

- RAC :

-

Ratio of the activating agent to carbon

- RF:

-

Random forest

- S1:

-

Sobol’s first-order index

- SA:

-

Surface area (m2/g)

- SSE :

-

Summation of residuals squares

- ST:

-

Sobol’s total-order indices

- SYY :

-

Summation of squares of data variation to the data mean value

- Ta :

-

Activation temperature (°C)

- th :

-

Holding time (hours)

- TPV:

-

Total pore volume (cm3/g)

- xi :

-

Values of the input variables in a sample

- \(\:\stackrel{-}{x}\) :

-

Mean of the values of the input variable

- \(\:\stackrel{-}{y}\) :

-

Mean of the values of the output variable

- \(\:{\widehat{y}}_{i}\) :

-

Predicted data values

- yi :

-

values of the output variable in a sample

References

Wareing, T. C., Gentile, P. & Phan, A. N. Biomass-based carbon dots: current development and future perspectives. ACS Nano. 15, 15471–15501 (2021).

Ramalingam, Gomathi, A. K., Priya, L., Gnanasekaran, S., Rajendran & Tuan, K. A. H. Biomass and waste derived silica, activated carbon and ammonia-based materials for energy-related applications–A review. Fuel 355, 129490 (2024).

Boulanger, N., Talyzin, A. V., Xiong, S., Hultberg, M. & Grimm, A. High surface area activated carbon prepared from wood-based spent mushroom substrate for supercapacitors and water treatment. Colloids Surf., A. 680, 132684 (2024).

Neolaka, Yantus, A. B. et al. Handoko Darmokoesoemo, and heri septya Kusuma. Potential of activated carbon from various sources as a low-cost adsorbent to remove heavy metals and synthetic dyes. Results Chem. 5, 100711 (2023).

Kumar, P. et al. Hesam Kamyab, Vijai Kumar Gupta, and Yasser Vasseghian. Exploring the role of activated charcoal from lignocellulosic biomass wastes for environmental pollution control. J. Energy Inst. 101626. (2024).

Mohammad-Khah, A. & Ansari, R. Activated charcoal:preparation, characterization and applications: A review Article. Int. J. Chemtech Res. 1 (4), 859–864 (2009).

Dias, J. M., Alvim-Ferraz, M. C. M., Almeida, M. F., Rivera-Utrilla, J. & Sánchez-Polo, M. Waste materials for activated carbon Preparation and its use in aqueous-phase treatment: A review. J. Environ. Manage. 85 (4), 833–846 (2007).

Tan, X. et al. Biochar as potential sustainable precursors for activated carbon production: multiple applications in environmental protection and energy storage. Bioresour Technol. 227, 359–372 (2017).

Arena, N., Lee, J. & Clift, R. Life cycle assessment of activated carbon production from coconut shells. J. Clean. Prod. 125, 68–77 (2016).

Zou, R. et al. Machine learning application for predicting key properties of activated carbon produced from lignocellulosic biomass waste with chemical activation. Bioresour. Technol. 399, 130624 (2024).

Ullah, S. et al. Aziz Ur Rehman, Tayyaba Najam, and Muhammad Altaf nazir. Activated carbon derived from biomass for wastewater treatment: synthesis, application and future challenges. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 106480. (2024).

Ruhaimi, A. H. & Muhammad Arif Ab Aziz. and. Tailoring tea residue-derived nitrogen-doped activated carbon for CO2 adsorption: influence of activation temperature and activating agents. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 1–25. (2024).

Gayathiri, M., Pulingam, T. & Lee, K. T. K. Sudesh activated carbon from biomass waste precursors: factors affecting production and adsorption mechanism chemosphere, 294 133764 (2022).

Almahbashi, N. M. Y. et al. Ghaleb. Optimization of Preparation conditions of sewage sludge based activated carbon. Ain Shams Eng. J. 12 (2), 1175–1182 (2021).

Li, H. et al. Leng Machine-learning-aided thermochemical treatment of biomass: a review. Biofuel Res. J. 10, 1786–1809 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Multi-task prediction and optimization of hydrochar properties from high-moisture municipal solid waste: application of machine learning on waste-to-resource, J. Clean. Prod 278, 123928 (2021).

Leng, L. et al. Machine learning predicting wastewater properties of the aqueous phase derived from hydrothermal treatment of biomass bioresour. Technol 358, 127348 (2022).

Li, H. et al. Machine learning assisted predicting and engineering surface area and total pore volume of Biochar. Bioresour. Technol. 369, 128417 (2023).

Liao, M., Kelley, S. S. & Yao, Y. Artificial neural network based modeling for the prediction of yield and surface area of activated carbon from biomass. Biofuels, Bioprod. Biorefin. 13 (4), 1015–1027 (2019).

Li, X., Huang, Z., Shao, S. & Yixi Cai. and. Machine learning prediction of physical properties and nitrogen content of porous carbon from agricultural wastes: Effects of activation and doping process. Fuel 356 129623. (2024).

Bai, R. et al. A new nanoporous nitrogen-doped highly-efficient carbonaceous CO2 sorbent synthesized with inexpensive Urea and petroleum coke. Carbon 81, 465–473 (2015).

Jang, E., Choi, S. W. & Hong, S. M. Sangcheol Shin, and Ki Bong Lee. Development of a cost-effective CO2 adsorbent from petroleum coke via KOH activation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 429, 62–71 (2018).

Yang, M. et al. Adsorption of CO2 by petroleum coke nitrogen-doped porous carbons synthesized by combining ammoxidation with KOH activation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 55 (3), 757–765 (2016).

Yang, J. et al. Herbert DaCosta, and Xin Hu. CO2 adsorption of nitrogen-doped carbons prepared from nitric acid preoxidized petroleum coke. Energy Fuels. 31 (10), 11060–11068 (2017).

Rao, L. et al. Single-step synthesis of nitrogen-doped porous carbons for CO2 capture by low-temperature sodium amide activation of petroleum coke. Energy Fuels. 32 (12), 12787–12794 (2018).

Chen, J. et al. Maciej Radosz, and Maohong fan. Enhanced CO2 capture capacity of nitrogen-doped biomass-derived porous carbons. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 4 (3), 1439–1445 (2016).

Liu, S., Ma, R., Xin, H., Wang, L. W. X., Fan, M. & Maciej Radosz, and CO2 adsorption on hazelnut-shell-derived nitrogen-doped porous carbons synthesized by single-step sodium amide activation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59 (15), 7046–7053 (2019).

Yue, L. et al. CO2 adsorption at nitrogen-doped carbons prepared by K2CO3 activation of urea-modified coconut shell. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 511, 259–267 (2018).

Li, J. et al. Ewa Mijowska, and Tao Tang. Selective Preparation of biomass-derived porous carbon with controllable pore sizes toward highly efficient CO2 capture. Chem. Eng. J. 360, 250–259 (2019).

Li, D., Ma, T., Zhang, R., Tian, Y. & Qiao, Y. Preparation of porous carbons with high low-pressure CO2 uptake by KOH activation of rice husk char. Fuel 139 68–70. (2015).

Li, D., Tian, Y., Li, L., Li, J. & Zhang, H. Production of highly microporous carbons with large CO 2 uptakes at atmospheric pressure by KOH activation of peanut shell Char. J. Porous Mater. 22, 1581–1588 (2015).

Quan, C., Su, R. & Gao, N. Preparation of activated biomass carbon from pine sawdust for supercapacitor and CO2 capture. Int. J. Energy Res. 44 (6), 4335–4351 (2020).

Shen, F. et al. Porous carbonaceous materials from hydrothermal carbonization and KOH activation of corn stover for highly efficient CO2 capture. Chem. Eng. Commun. 205 (4), 423–431 (2018).

Quan, C., Jia, X. & Gao, N. Nitrogen-doping activated biomass carbon from tea seed shell for CO2 capture and supercapacitor. Int. J. Energy Res. 44 (2), 1218–1232 (2020).

Rao, L. et al. Nitrogen enriched porous carbons from d-glucose with excellent CO2 capture performance. Chem. Eng. J. 362, 794–801 (2019).

Yue, L. et al. Efficient CO2 capture by nitrogen-doped biocarbons derived from rotten strawberries. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 56 (47), 14115–14122 (2017).

Liu, S. et al. Nitrogen-doped porous carbons from Lotus leaf for CO2 capture and supercapacitor electrodes. Energy Fuels. 33 (7), 6568–6576 (2019).

Rao, L. et al. Low-temperature and single-step synthesis of N-doped porous carbons with a high CO2 adsorption performance by sodium amide activation. Energy Fuels. 32 (10), 10830–10837 (2018).

Kim, M. J., Choi, S. W., Kim, H. & Mun, S. Simple synthesis of spent coffee ground-based microporous carbons using K2CO3 as an activation agent and their application to CO2 capture. Chem. Eng. J. 397, 125404 (2020).

Yang, Z., Guo, X., Zhang, G. & Xu, Y. One-pot synthesis of high N‐doped porous carbons derived from a N‐rich oil palm biomass residue in low temperature for CO2 capture. Int. J. Energy Res. 44 (6), 4875–4887 (2020).

Yang, Z., Zhang, G., Xu, Y. & Zhao, P. One step N-doping and activation of biomass carbon at low temperature through NaNH2: an effective approach to CO2 adsorbents. J. CO2 Utilization. 33, 320–329 (2019).

Weldekidan, H., Patel, H., Mohanty, A. & Manjusri Misra. Synthesis of porous and activated carbon from lemon peel waste for CO2 adsorption. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 10, 100149 (2024).

Wu, W. et al. Nitrogen-doped porous carbon through K2CO3-activated bamboo shoot shell for an efficient CO2 adsorption. Fuel 363 130937. (2024).

Shao, S., Wang, Y., Ma, L., Huang, Z. & Li, X. Sustainable preparation of hierarchical porous carbon from discarded shells of crustaceans for efficient CO2 capture. Fuel 355, 129287 (2024).

Shao, J. et al. Unlocking the potential of N-doped porous carbon: facile synthesis and superior CO2 adsorption performance. Sep. Purif. Technol. 333, 125891 (2024).

Sreńscek-Nazzal, J., Kamińska, A., Serafin, J. & Michalkiewicz, B. Chemical activation of banana peel waste-derived biochar using KOH and Urea for CO2 capture. Materials 17 (4), 872 (2024).

Ayub, Y., Hu, Y. & Ren, J. Estimation of Syngas yield in hydrothermal gasification process by application of artificial intelligence models. Renew. Energy. 45, 118953 (2023).

Quinlan, J. R. Induction of decision trees. Mach. Learn. 1, 81–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00116251 (1986).

Grömping, U. Variable importance assessment in regression: linear regression versus random forest. Am. Stat. 63 (4), 308–319 (2009).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. Vol. 45, 5–32. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010933404324 (2001).

Otchere, D. A. Tarek Omar Arbi Ganat, Jude oghenerurie Ojero, Bennet Nii Tackie-Otoo, and Mohamed Yassir Taki. Application of gradient boosting regression model for the evaluation of feature selection techniques in improving reservoir characterisation predictions. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 208, 109244 (2022).

Friedman, J. H. Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine. Annals Stat. Vol. 29, 1189–1232 (Oct., 2001).

Abrahart, R. J. & See, L. M. Neural network modelling of non-linear hydrological relationships. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11 (5), 1563–1579 (2007).

Cortes, C. & Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 20, 273–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00994018 (1995).

Sivanandam, S. N., Deepa, S. N. & Sivanandam, S. N. and S. N. Deepa Genetic Algorithm Optim. Probl. Introduction Genetic Algorithms : 165–209. (2008).

Wright, A. H. Genetic algorithms for real parameter optimization. In foundations of genetic algorithms, vol. 1, 205–218. Elsevier, (1991).

Goodfellow, I., Yoshua, B. & Aaron, C. Regularization deep learn. deep learn. : 216–261. (2016).

Eichler, J., Ehren, J. N., Burrow, Y., Wang, D. C. & Calabro Buddie mullins. Unraveling porogenesis in nitrogen rich K+-activated carbons. Carbon 186, 711–723 (2022).

Sevilla, M. & Mokaya, R. Energy storage applications of activated carbons: supercapacitors and hydrogen storage. Energ. Environ. Sci. 7 (4), 1250–1280 (2014).

Li, S. et al. Investigation on pore structure regulation of activated carbon derived from sargassum and its application in supercapacitor. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 10106 (2022).

Musthofa, A. M., Hadi, M., Syafila & Helmy, Q. Effect of activated carbon particle size on methylene blue adsorption process in textile wastewater. Indonesian J. Chem. 23 (2), 461–474 (2023).

Hulicova-Jurcakova, D., Seredych, M., Lu, G. Q. & Teresa, J. Bandosz. Combined effect of nitrogen‐and oxygen‐containing functional groups of microporous activated carbon on its electrochemical performance in supercapacitors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 19 (3), 438–447 (2009).

Devi, R. et al. Recent advancement in biomass-derived activated carbon for waste water treatment, energy storage, and gas purification: a review. J. Mater. Sci. 58 (30), 12119–12142 (2023).

Wang, B., Lan, J., Bo, C., Gong, B. & Junjie Ou. Adsorption of heavy metal onto biomass-derived activated carbon. RSC Adv. 13 (7), 4275–4302 (2023).

Ferdous, A. et al. Munetaka Oyama, and Md Abdul Aziz. Advancements in biomass-derived activated carbon for sustainable hydrogen storage: A comprehensive review. Chemistry–An Asian J. 19 (16), 202300780 (2024).

Chin, K. et al. and. Refining micropore capacity of activated carbon derived from coconut shell via deashing post-treatment. BioResources 15, 4 7749. (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Interdisciplinary Research Center for Advanced Materials and King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals for their support through Grant # INAM2401.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.F. I. Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editingM.A.H. Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Project administration, contribute in Writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ibrahim, A.F., Hussein, M.A. Leveraging machine learning for prediction and optimization of texture properties of sustainable activated carbon derived from waste materials. Sci Rep 15, 11313 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95061-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95061-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Using acoustic emission signal analysis and machine learning algorithms for predicting mechanical hardness in laser directed energy deposition parts

The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology (2025)

-

Unlocking the Potential Applications of Bamboo, as an Energy Resource and Bamboo-Based Activated Carbon: A Comprehensive Review

BioEnergy Research (2025)