Abstract

Amid global climate change, the pursuit of low-carbon development has become a unified international goal. The Qinba Mountain region plays an important role in maintaining China’s ecological security, making spatial zoning tailored for carbon neutrality vital for local sustainable development. Using land use and socioeconomic data from 2000 to 2020 for 81 county-level units, a carbon neutral spatial zoning framework was developed, considering natural, economic, ecological and land resource factors. This study further integrated spatiotemporal dynamics of carbon index and multi-scenario predictions of future carbon emission (CE) for spatial zoning. The results revealed that the region had an overall positive net-carbon emission trend without significant ecological deficits, the central region faced increased CE and the northern region had weak ecological carrying capacity. The predicted future CE continued to decrease under low-carbon scenario and reached 30.55 million t by 2060, with only nine units failing to reach their carbon peaking by 2030. Five different zones were identified: carbon sink functional zone, low-carbon development zone, net-carbon stabilization zone, high-carbon control zone and carbon source optimization zone. Tailored optimization strategies for each zone were proposed to enhance regional ecological environment and contribute to green development. These findings offer insights into achieving carbon neutrality and sustainable development for regions or cities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change is a major global challenge that poses significant risks to human society, with greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from fossil fuel use damaging natural ecosystems1. In response, the Paris Agreement adopted in December 2015, set a global goal to limit the increase in global surface temperature to 2 °C by the end of the 21st century compared to preindustrial levels, with efforts to contain it within 1.5 °C. Given these circumstances, the Chinese government announced in September 2020 its commitment to “reach the peak of CO2 emissions by 2030 and attain carbon neutrality by 2060” (Responding to climate change: China’s policies and actions, accessed 7 February 2023). Land is a key carrier of carbon sources and sinks, serving as a fundamental spatial element for realizing the carbon peaking and carbon neutrality (“dual carbon”) targets2,3. By prioritizing carbon effects in optimizing spatial pattern, low-carbon land se can help realize China’s “dual carbon” targets, with significant implications for sustainable development4,5.

Carbon neutrality refers to the balance between carbon emission (CE) from anthropogenic activities and those offset through mitigation measures, also known as net-carbon emission (NCE)6. In China, achieving carbon neutrality involves decreasing GHG emission to near-zero level through low-carbon industrial practices, advanced urban development and improvements to human settlement quality, while balancing economic growth with environmental preservation7,8. Territorial spatial planning is the guiding principle for various construction and development endeavors in China, which directly impacts land use, ecology and energy distribution9. Of particular importance is the delineation and optimization of land use space, which offers substantial strategic advantages in addressing climate change and achieving carbon neutrality10. Territorial spatial zoning is also widely acknowledged as an effective tool for harmonizing and regulating CE and carbon sequestration (CS).

Land use and carbon cycle are strongly interconnected, with changes in land resource distribution and use often leading to shifts in carbon sources and sinks in ecosystems11,12. In recent years, land use change has contributed 27% of global GHG emissions, attracting extensive scholarly attention to their feedback relationships13. Many studies evaluated carbon baseline14, calculated CE15, analyzed impacting factor16and proposed mitigation measure17based on land use/cover and energy data, with a focus on carbon balance18, carbon offset19, carbon footprint20and low-carbon strategy21. These studies have identified that the main sources of CEare concentrated in industry22, agriculture23and animal husbandry24, and highlighted the importance of energy consumption25, crop production26, economic development27and population growth28 in driving CE. Common methods include field measurement29, remote sensing30and coefficient estimation31. Carbon sink primarily comes from vegetation32, such as forest33, grassland34and cropland35 with double carbon (CE and CS) attributes. Large-scale ecosystem management is considered a key pathway to achieving carbon neutrality in many studies, which have taken into account ecosystem service trade-offs36, eco-efficiency37, habitat quality38and economic-environmental coordination39. Additionally, when integrating land use dynamics, local variations40, spillover effects41and spatial zoning42 can be explored to explain spatial homogeneity and heterogeneity in achieving carbon neutrality.

Future CE prediction directly reflects the realization of “dual carbon” targets and evaluates a region’s carbon emission potential (CEP). Many scholars have studied the various driving factors involved in the prediction process and reveled their positive and negative impacts on CE, such as industrial structure43, population size44, wealth45and urbanization46. Common prediction methods include Regression Analysis47and Gray Correlation48. In recent years, there has been a growing focus on machine learning models, such as Multi-objective Grey Wolf Optimization49, Artificial Neural Networks50and Particle Swarm Optimization-BP neural network model51, which offer high prediction accuracy. However, these models have limitations, including weak interpretability, unclear variable relationships and high data requirements, which restrict their application in multi-scale CE prediction. Furthermore, Cellular Automata models (e.g., CLUE-s, FLUS and PLUS) are frequently used for predicting land use CEunder various scenarios52,53,54. These models primarily focus on spatiotemporal variations in land use patterns that carry carbon sources and sinks, with limited attention to the actual CE or CSprocesses. Notably, the STIRPAT (Stochastic Impacts by Regression on Population, Affluence and Technology) model55 remains the most widely used in future CE prediction studies, particularly at the national and provincial levels. The results of future CE prediction serve as a key quantitative index for evaluating whether a region can achieve its “dual carbon” targets.

Since the 1990s, the role of urban areas in decreasing CE has gradually attracted academic attention. Relevant studies have primarily been conducted within two analytical frameworks: one based on the CEimpact mechanism of “anthropogenic activities”56, and the other focused on the environmental effect evaluation derived from “microclimate observations”57. However, these studies often focused on local CE within urban areas and overlooked the spatial relationship and interaction with surrounding areas. With the proposal of “dual carbon” targets, academic focus has shifted to global carbon consumption trends, which might have overlooked regional evaluation of CEand tailored strategies for realizing the “dual carbon” targets. Moreover, studies on the establishment of regional carbon accounting systems and the implementation of regional spatial zoning for carbon neutrality remain insufficient and require further exploration. It is noteworthy that mountain areas, as typical representatives of multi-level administrative divisions, show significant economic gradients, population changes and homogeneous ecological conditions58. These characteristics provide a unique spatial context for regional land use CE studies. Mountain areas have both internal differences and systematic commonalities that make combining “anthropogenic activities” and “climate observations” in land use CEevaluation theoretically feasible, with carbon neutrality spatial zoning based on it practically valuable. However, the complex nonlinear interaction between climate change and anthropogenic activity causes uncertainty in achieving carbon neutrality56,57. Therefore, targeting mountain areas to analyze the spatiotemporal evolution of carbon index, predict future CE and incorporate carbon neutrality into spatial zoning and optimization strategies can further enrich related studies.

Accordingly, an evaluation system was established based on land use and energy data from 2000 to 2020, incorporating key indices such as CE, CS, economy contributive coefficient (ECC), ecological support coefficient (ESC) and carbon footprint (Cf). The system aimed to evaluate the spatiotemporal variation of land use CE in the Qinba mountain region (a typical ecological conservation area in China). The STIRPAT model was used to predict future CE under various scenarios and evaluate CEP. Moreover, the comprehensive land use index (CLI) was also introduced to set criteria for carbon neutral spatial zoning. Spatial differences and potential challenges of zoning with different carbon contributions and optimization pathways were revealed. It is anticipated to provide scientific insights for carbon neutral spatial governance and low-carbon development strategies.

This article begins with a literature review on land use CE and identifies existing research gaps. It then details the study area, data sources, evaluation indices and selected methods (Fig. 1 shows an overview of analytic methods). Subsequently, the spatiotemporal variation of land use and carbon indices, various scenario predictions of future CE, spatial zoning and optimization strategies for carbon neutrality are presented. Next, the reasons and some extensions that impacted study results, as well as policy recommendations, contributions and limitations are discussed. Finally, the main findings are summarized.

Materials and methods

Study area

The Qinba Mountain region (103°74″–113°23″ E, 30°48″–34°62″ N) is located in central mainland China (Fig. 2). Its administrative scope includes Gansu, Henan, Hubei, Shaanxi, Sichuan and Chongqing (involving 81 county-level administrative units), covering an area of 22.45 × 104 km2. Its location spans the Yangtze, Yellow, and Huai River Basins, resulting in highly developed water systems and abundant runoff resources. With a forest coverage rate of 53%, it is an important ecological and biodiversity conservation area in China. In 2020, the GDP totaled USD 177.89 billion and the resident population was 30.03 million. However, the overall economy lags behind. Compared with highly industrialized urban agglomerations, the Qinba Mountain region faces more pronounced conflicts between ecological protection and economic development. As local demands for economic and social development grow, anthropogenic activities are expected to increase the consumption of land and energy resources, which may lead to high CE and ecosystem degradation. Therefore, selecting the Qinba Mountain region, which is rich in carbon storage and has urgent development demands, as a case study for carbon neutral spatial zoning provides valuable empirical insights for low-carbon transformation strategies in mountain areas worldwide.

The location of study area (a map of China obtained from http://bzdt.ch.mnr.gov.cn, accessed on 3 March 2023).

Data sources and processing

The fundamental data are described in Table 1, with the coordinate system of geographic element data standardized to WGS 1984 and Gauss-Krüger projection. Special notes: The land use types of raw data were reclassified into cropland, shrubland, forest, grassland, water area, urban land and unused land (L1–L7) to align with the objectives of this study. In certain units, due to the absence of specific data on energy consumption and agricultural plastic film usage, it was necessary to refer to the municipal-level energy balance table, and proportional conversions were performed based on the gross value of energy industry and the sown area of crops to ascertain the numerical values of relevant indices. Residual or biased data in the time series were reassigned using cubic spline interpolation.

Carbon index evaluation

Land is the primary carrier of carbon source and sinks59. The CEprimarily results from agricultural production on cropland and energy consumption on urban land22, while the CSmainly occurs through photosynthesis in cropland, shrubland, forest, grassland and water area23,24. The specific equations are shown in Table 2.

In agricultural production activities, fertilizer, pesticide, agricultural plastic film, irrigation and crop cover all contribute to CEfrom cropland22. The CEfrom livestock in other cropland is primarily due to GHGs emitted through breathing, gastrointestinal fermentation and manure management during their growth23. The CSfrom urban land is generated by fossil energy consumption and human breathing24. Ecosystems, particularly forest, are rich in vegetation that functions as carbon sinks, effectively sequestering CO2from the atmosphere through photosynthesis and storing it as organic matter in plant tissues60. The NCE refers to the difference between CE and CSwithin a specified system or activity61.

The ECC evaluates the disparity in CEacross various economic production levels within different regions, thereby reflecting the use efficiency of carbon62. An ECC greater than 1 indicates that the region’s economic contribution surpasses its CE, reflecting higher energy efficiency and carbon productivity34. Conversely, an ECC less than 1 indicates lower energy efficiency and carbon productivity. The ESC evaluates the equity of carbon ecological capacity distribution, emphasizing its CSpotential63. An ESC greater than 1 indicates that the ecological contribution to CS exceeds CE, demonstrating a robust capacity for carbon offsetting35. Conversely, an ESC less than 1 indicates that local CS is insufficient to balance CE, leading to a lower carbon offsetting rate.

The Cf is commonly regarded as the ecological footprint associated with CE, representing the area of biologically productive land required to offset CEresulting from anthropogenic production activity64. It effectively reflects the ecological carrying capacity (Ec) and ecological deficit (Ed) status of a region59. The net ecosystem production (NEP) quantifies the CS potential of various vegetation types, enabling the calculation of land area needed to offset CEfrom cropland, shrubland, forest and grassland65.

Carbon potential analysis

Theil-Sen median trend and Mann-Kendall test

The Theil-Sen Median, also known as Sen slope estimation, is a robust nonparametric statistical method for trend analysis, particularly well-suited for evaluating long-term temporal datasets69. The Mann-Kendall test evaluates the significance of trends in datasets by examining the correlation among data points70. This study integrated them to quantitatively evaluate temporal trends in carbon indices. A Sen-estimated value greater than 0 indicates an increasing trend, a value of 0 indicates stability and a value less than 0 indicates a decreasing trend (Table 4). The Mann-Kendall test results were obtained at a 5% confidence level and classified into five different trends based on Z-value (test statistic).

STIRPAT model

The STIRPAT model, an extension of the IPAT equation (Environmental Impact = Population × Affluence × Technology), is an improved nonlinear model that can conduct quantitative analyses of anthropogenic impacts on environmental stress55. In this study, population size (P), wealth level (W), industrial structure (IS), technological innovation (TI), urbanization rate (UR) and carbon emission intensity (CEI) identified as independent variables and CE as dependent variable. To address potential multicollinearity among independent variables, ridge regression was used to calculate coefficients and derive prediction equation (Eq. 12). Regression parameter (K-value) was identified based on ridge trace. The model’s validity was verified through an independent sample t-test between ridge regression results and actual CE based on annual data.

Where a is model coefficient; b, c, d, e, f and g are coefficients of corresponding independent variables, respectively; Pi is the number of population in i-th region (person); Wi is per capita GDP in i-th region (CNY 10,000); ISi is value added of secondary industry in i-th region / GDP in i-th region (%); TIi is GDP in i-th region / energy consumption in i-th region (CNY 10,000/coal); URi is urban population in i-th region / total population in i-th region (%); CEIi is total CE in i-th region / secondary industry GDP in i-th region (coal/CNY 10,000); Ui is error term of model.

Scenario setting

The STIRPAT model was used to establish three scenarios: low-carbon, baseline and high-carbon, aimed at predicting CE of 81 units in the Qinba Mountain region from 2020 to 2060 (with 5-year intervals). The growth rate or threshold for independent variable in each scenario was set based on the provincial 14th Five-Year Plan, greenhouse gas control strategies and socio-economic development. To achieve the targets for 2030 (carbon peaking year) and 2060 (carbon neutral year), differentiated independent variable changes were set accordingly.

According to the National Population Development Plan, China’s population is projected to peak in 2030 and then enter a slowly decreasing period. Therefore, the P was set as follows: the minimum, average and maximum annual growth rates from 2000 to 2020 corresponded to low-carbon, baseline and high-carbon scenarios before 203044. After 2030, the growth rates of P were adjusted to positive values across all scenarios (unchanged if originally positive and the same applies below). Specifically, the minimum (a further 20% increase), average and maximum (a further 20% decrease) annual growth rates corresponded to low-carbon, baseline and high-carbon scenarios, respectively. The W and TI typically show decreasing trends and have opposite effects on CE: increased W leads to increased CE, while increased TI leads to decreased CE45. For this reason, the growth rates for W and TI were adjusted to positive values across all scenarios. Different growth rates were used before and after 2030 based on specific scenarios. Given the positive correlation between IS and CE, the minimum, average and maximum annual values from 2000 to 2020 were set as the thresholds for low-carbon, baseline and high-carbon scenarios before 203043. After 2030, the thresholds of IS were adjusted as follows: a 5% decrease for low-carbon scenario, no change for baseline scenario and a 5% increase for high-carbon scenario. The thresholds of UR were set according to the provincial 2030 target in the 14th Five-Year Plan, which was directly used for the baseline scenario and adjusted by ± 5% for other scenarios and time periods46. Given that a low CEI is typically referred to as generating low CE for equal economic input, the increase rates of CEIwere adjusted to positive values across all scenarios43. The minimum, average and maximum annual growth rates from 2000 to 2020 corresponded to low-carbon, baseline and high-carbon scenarios before 2030. After 2030, the growth rates of CEI were adjusted as follows: a 1% decrease for low-carbon scenario, no change for baseline scenario and a 1% increase for high-carbon scenario. As an illustrative example, the scenario settings for independent variables in units within Shaanxi Province are shown in Table 5.

Zoning criteria

Carbon neutral spatial zoning was conducted in the Qinba Mountain region based on increasing or decreasing trends (Z-value) of carbon indices. Additionally, the CLI was introduced as a key index in evaluating carbon-land interactions, where a low CLIindicates that land resources are minimally disturbed and have robust carbon sink capacities71. The CEP, an expression of future CE prediction, was included in the zoning considerations because it directly indicates the feasibility of realizing the “dual carbon” targets. All carbon indices were classified into four groups. The attributes (positive or negative) of carbon indices were defined and classified as 1 to 5 (dimensionless). Each unit in the Qinba Mountain region was assigned values based on the criteria shown in Table 6, with a high total value indicating a favorable foundation for achieving carbon neutrality. Spatial overlay calculations and natural fracture hierarchies were executed in ArcGIS, and five zones were delineated: carbon sink functional zone, low-carbon development zone, net-carbon stabilization zone, high-carbon control zone and carbon source optimization zone.

Results

Land use evolutionary trajectory

The unique hilly and valley topography of the Qinba Mountain region greatly impacts local land use pattern, thereby determining the distribution and scale of carbon sources and sinks. Land use changes from 2000 to 2020 showed significant spatial differences (Fig. 3). Notably, cropland was decreasing significantly in the northwestern region, which is characterized by steep topography and low soil fertility. Comparatively, urban land and cropland showed significant and synchronized increases in the southeastern region, which is characterized by gentle slopes and sufficient rainfall. Among ecological lands, shrubland and grassland are more vulnerable to anthropogenic activities than forest. From 2000 to 2005, shrubland and grassland were decreasing significantly, while forest was increasing significantly. However, improved ecological awareness and planting policies slowed down the decreasing rate of shrubland and grassland since 2005. Even shrubland increased in the western region after 2005. The standard deviation ellipse width and azimuthal angle of forests were decreasing since 2005, forming an east-west distributed spatial pattern in 2020. Additionally, grassland was decreasing significantly and water area was increasing significantly in the southeastern region after 2005, especially near the Han, Dan and Jialing Rivers. It may be related to regional soil erosion and water project construction. Urban land was increasing significantly in the eastern region after 2005, while it increased slowly in the central and western regions. Unused land, primarily distributed in the southwestern region, changed little from 2000 to 2020, which may be due to low intensity of anthropogenic activities in the region.

Spatiotemporal variation in carbon index

Temporal characteristics

The economic and social demand were increasing from 2000 to 2020 in the Qinba Mountain region. It led to accelerating industrialization and widespread burning of fossil fuels, which significantly increased CE. As shown in Fig. 4, CE was increasing from 41.99 to 540.16 million t, with the lowest in 2002 (34.71 million t) and the highest in 2015 (56.42 million t). However, the Qinba Mountain region with its ecological self-restoration capacity can carry out carbon sequestration through natural processes even in the absence of anthropogenic intervention. Additionally, local measures such as reforestation and planting trees can further increase vegetation cover and enhance carbon sink capacity. Therefore, the CS was increasing from 2000 to 2020. It consistently exceeded 90.09 million t since 2005 and reached 95.16 million t in 2020. The NCE showed stable fluctuations over the 20-year period, ranging from 4.13 to 43.84 million t. Its lowest (20.63 million t) occurred in 2014 due to increased CS and its highest (55.12 million t) occurred in 2018 due to increased CE. These fluctuations indicate that the Qinba Mountain region still possess robust carbon balance capability.

The increased economic output and clean technology application are typically reflected in changes of ECC. It reached the highest value in 2003 (153.2%) and then decreased over the following four years. However, it was increasing since 2008 and reached 138.4% in 2020. The ESC was decreasing from 2000 to 2020, but it consistently remained above 100%. Additionally, it reached the highest value (273.8%) in 2004 and then decreased sharply to the lowest value (156%) in 2007, and finally increased gradually to 179.6% in 2020. The Cfwas increasing since 2008 and reached 145.7 km2 in 2020. The Ecwas fluctuating between 219,400 and 228,200 km2 from 2000 to 2020. The negative impacts of ecological resource consumption beyond ecological self-restoration capacity were not significant because Ec was consistently greater than Cf, resulting in Ed being less than 0 from 2000 to 2020. From the above, it can be inferred that pressure on ecological environment from increasing land use intensity in the Qinba Mountain region still exists, but the carbon offset effect produced by biologically productive land is significant over a long period.

Spatial characteristics

According to the Theil-Sen Median trend and Mann-Kendall test, the CE of 55 units showed increasing trends in the Qinba Mountain region (Figs. 5 and 6). The industrial factories concentrated in Hanbin, Hantai, Pingli, Shiquan, Baihe and Ziyang have high energy consumption, and CE of these units showed marked increasing trends. The CE of 24 units showed decreasing trends, with marked decreases observed in units with abundant carbon sinks, such as Nan Zhao, Lushi, Enyang, Luoning, and Zhenping. The units with decreasing trends in CE were primarily distributed in the western and southern regions. The CS of most units showed increasing trends, except in densely populated units such as Foping, Shiquan, Maowei, Zhangwan, Enyang, Yilong and Wushan. These units may be impacted by overdevelopment and pollution. The NCE of Zhouzhi in the northern region showed an unchanged trend, while NCE of most units in the central region showed decreasing trends.

The ECC of most units showed increasing trends, with Z-values ranging from 0.39 to 4.92. The ECC of 33 units showed marked increasing trends. However, units distributed along the Han and Jialing Rivers have traditional industries and low energy efficiency, and their ECC showed decreasing trends. Among them, the ECC of Hanbin and Chenggu showed marked decreasing trends. The ESC of 45 units showed decreasing trends, while ESC of 36 units showed increasing trends. Moreover, 39 units had Z-values of ECC and ESC greater than 0, indicating trends of high economic yield and CS. 10 units had Z-values of ECC greater than 0 but ESC less than 0, indicating trends of high economic yield and CE. Four units had Z-values of ECC less than 0 but ESC greater than 0, indicating trends of low economic yield and CE. 24 units had Z-values of ECC and ESC less than 0, indicating trends of low economic yield and CS. The Cf of 39 and 15 units showed marked increasing and decreasing trends, respectively. The Ec of four and 59 units showed marked increasing and decreasing trends, respectively. The Ed of 55 units distributed in the central and northern regions showed increasing trends. Among them, the Ed in Hantai and Pingwu showed marked increasing and decreasing trends, which were more pronounced than those in other units.

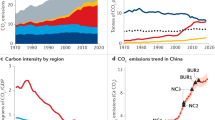

Future carbon emission prediction

The multivariate regression analysis showed that the variance inflation factors (VIFs) for variables, except lnP and lnIS, were greater than 10 (Table 7). Especially, the VIFs for lnW and lnUR were 213.31 and 160.75, respectively, indicating severe multicollinearity among the independent variables. Therefore, ridge regression was used to reanalyze the data. Generally, the smaller K-value, the less information is lost and the higher model accuracy. Based on the trend of ridge trace, coefficients gradually stabilized at K-value of 0.02 (Fig. 7a), the VIFs for variables remained below 10 and R2 reached 0.825, indicating a good model fit. The t-test showed p-value of 0.898, which is greater than the significance level of 0.05, indicating that there is no significant difference between predicted CE and actual data. Therefore, the ridge regression equation with K-value of 0.02 and unstandardized coefficients (Eq. 13) can be used as the linear form of STIRPAT model.

Future CE prediction under different scenarios. (a is the ridge trace about relationship between K-value and standardized coefficient of independent variable; b is the distribution of total CE under different scenarios from 2000 to 2060; c is the temporal variation in total CE under different scenarios from 2000 to 2060).

By comparing the coefficients of variables in STIRPAT model, it can be inferred that UR had the most significant impact on CE. A 1% increase in UR resulted in a 0.377% increase in CE. Expanding infrastructure, increasing energy consumption and escalating transport demand during the urbanization process may lead to high CEduring urbanization process72. A 1% increase in CEI resulted in a 0.304% increase in CE. The CEI reflects the CE per unit of economic yield. A high CEI indicates that economic growth is heavily dependent on carbon-intensive energy and technologies, which can lead to an increase in CE73. Additionally, the TI had negative impact on CE. Typically, the driving force behind TIis competitive pressure driven by market demand and population growth74. However, the actual impact of TI on decreasing CEmay experience time lags due to constraints in funding and time, as well as barriers in market and policies75.

The predicted future CE of 81 units in the Qinba Mountain region were analyzed under three scenarios: low-carbon, baseline, and high-carbon (Fig. 7b, c). Under low-carbon scenario, a total of 9 units, primarily distributed around Hankan and Hanzhong, were projected not to reach their carbon peaking before 2030. Under baseline scenario, 30 units, including Luoyang, Zhenba, and Xixiang, were projected to reach their carbon peaking before 2030. However, 15 of these units were projected not to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. Under high-carbon scenario, 22 units were projected not to reach their carbon peaking before 2030. Comprehensive predictions for three scenarios showed CEP of these units. They were classified into highly significant, moderately significant, stable, slightly insignificant and insignificant in terms of realizing the “dual carbon” targets. 20 units would reach their carbon peaking before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. 23 units would reach their carbon peaking before 2030, with a significant downward trend in subsequent CE, but would not achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. 11 units would reach their carbon peaking before 2030 under both baseline and low-carbon scenarios but still would not achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. Four units, despite moderate increasing trends in CE, would not reach their carbon peaking or achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. Furthermore, the CE of 13 units, particularly those of Shiquan, Foping, and Pinchang, would continue to increase significantly.

Carbon neutral control zoning and optimization

-

(i)

Carbon sink functional zone, primarily distributed in the eastern region, shows superior habitat quality and robust capacities for CS when compared to other zones (Fig. 8). Key units such as Nanzhao, Xichuan, Zhenping and Lushi have high proportions of cropland, forest and water area, which are characterized by efficient energy utilization. This efficiency is important for sequestering local CE, increasing local biodiversity and fostering economic development. To maintain this sustainability, it is necessary to implement strict controls on urban land expansion rate. Units such as Luanchuan, Fangxian, Baokang, Wanyuan, Pingwu, and Chengkou, which are distributed across the eastern, southeastern, southern and western regions, are primarily forested and possess robust capabilities for CS and ESC management. These units contribute to decreasing local NCE and increasing CS for the entire Qinba Mountain region. To broaden the impact of CS, carbon sink functional zone should prioritize enhancing endogenous dynamics and improving quality.

-

(ii)

Low-carbon development zone, with superior ecological resources and ECC, has successfully achieved a harmonious balance between habitat quality and economic benefits. This zone is primarily distributed in the eastern and western regions. The eastern segment, comprising 16 units, is predominantly covered by cropland and forest, showing robust coordination in CE and CS. These units have higher ECC compared to others, thereby establishing solid foundations for the development of eco-agricultural zones. In the future, it is important to improve agricultural production capacity and safeguard cropland, thereby promoting the development of integrated cropland and forest. Conversely, the western segment, comprising 17 units, is characterized by a greater area of forest than cropland. These units possess low Cf but offer substantial biologically productive land for CS both locally and across the Qinba Mountain region. Moving forward, it is important to effectively manage conflicts in production and ecological spaces.

-

(iii)

Net-carbon stabilization zone shows balanced interactions between CE and CS, despite it being slow economic growth. This zone is dispersed in its overall distribution but is significantly concentrated in the northwestern region. Notably, units such as Maoyuan, Zhangwan, Shangzhou, Bazhou and Zhaohua can properly control CE and efficiently use land resources, despite them having low ESC. These units should accelerate urbanization, increase economic benefits and improve development quality of secondary industries. Additionally, other units that maintain balanced ecological and agricultural development despite low CE and slow economic growth should focus on spatial pattern of carbon balance. They should leverage their ecological advantages to improve the conversion of land resources into economic benefits in the future.

-

(iv)

High-carbon control zone, characterized by higher CE than the average level in the Qinba Mountain region, is primarily distributed in the southwestern (4 units) and central (10 units) regions. These units are widely covered by cropland and urban land, with concentrations of energy-intensive industries. The southwestern zone contains numerous carbon sources and low Ec, resulting in limited level of CS. Therefore, future measures should prioritize expanding ecological land and decreasing Cf of neighboring economic and industrial clusters to optimize cropland allocation and enhance carbon sink capacity. Conversely, the central region, adjacent to carbon source optimization zone, faces significant ecological risks caused by own high CE and external carbon overflow. Therefore, future development should focus on the implementation of carbon offset practices and the full exploitation of local carbon sinks to alleviate both internal and external ecological impacts.

-

(v)

Carbon source optimization zone consists of four units distributed in the north-central region and one unit distributed in the northeastern region. These units are highly susceptible to anthropogenic intervention due to their low Ec and land use efficiency. Specifically, CLI in the north-central units of Hantai, Hanbin, Shiquan and Foping are lower than the average level. They show increasing trends in Ed, which seriously impacts the local ecological and environmental quality. It is necessary to prioritize developing low-carbon economy and decreasing carbon emissions from energy-intensive industries in the future. Additionally, the northeast units all over 10% of urban land in 2020 and they have low ECC and Ec. The current carbon sink capacity is insufficient to counterbalance increasing CE from various carbon sources. Therefore, increasing forest and enhancing carbon cycling within cropland are urgently necessary to balance CE and CS.

Discussion and policy recommendations

Dynamic relationship between land use and CE

Between 2000 and 2020, the Qinba Mountain region experienced continuous decreases in the areas of cropland, shrubland, grassland and unused land, while the areas of forest, water area and urban land showed increasing trends. These changes in land use pattern significantly impact the region’s carbon source and sink capacities, thereby reflecting the progress toward achieving carbon neutrality. Notably, cropland, as a land use type with double carbon attributes, plays an important role in regulating soil carbon storage through various agricultural practices. Many studies have demonstrated that enhancements in cropland management, such as decreasing fertilizer application76and incorporating manure recycling77, can substantially decrease CE. Importantly, in mountainous area like the Qinba Mountain region, characterized by low population density and complex topography, the effects of planting structure and crop types on carbon neutrality may differ from those observed in plain and coastal areas78,79. In mountainous area, where significant elevation changes result in fragmented and dispersed cropland, the implementation of large-scale mechanized operations is challenging and traditional intensive farming practices remain predominant80.

Furthermore, forest serves as the primary contributor of CS. The finding is robustly supported by this study and is consistent with other related studies that emphasize the important role of forest ecosystem in the global carbon cycle81. We found that CS in the Qinba Mountain region showed an increasing trend and consistently surpassed CE from 2000 to 2020, resulting in a negative NCE. The forest ecosystem, characterized by substantial and diverse biomass, sequesters CO2 through photosynthesis, thereby significantly increasing its CS82. Additionally, we found that shrubland, grassland and water area, despite their low spatial aggregation, contribute significantly to enhancing local carbon sink capacity. It is different some studies that have concluded that carbon sink capacities of shrubland and grassland are limited83,84. The distinctive geographic and climatic conditions of mountainous area may be contributing factors to these findings85. The Qinba Mountain region is in transitional zone between subtropical and warm temperate zones, where significant humid climate and vertical climatic variations offer a variety of ecological niches that are beneficial for increasing shrubland and grassland86. They are the dominant vegetation especially at high elevation areas with poor soil87. The vegetation plays an important role in stabilizing soil carbon stocks and absorbing CO2through its extensive root system during the growing season60. Meanwhile, the transport and deposition of water currents across widely dispersed water area contribute to carbon storage by aquatic plants, thereby enhancing carbon sink capacity88.

This study identified significant correlations between urban land expansion and increased CEin the Qinba Mountain region, which is consistent with the general trends in global urbanization46. Based on the actual context, we concluded that the extensive development model characterized by infrastructure and real estate construction during urbanization may contribute to increased CLI, which directly weakens carbon sink capacity. However, most units showed downward trends in CLI, indicating that their carbon sink potentials remain significant. The prediction and analysis of future CE under low-carbon, baseline and high-carbon scenarios showed that 30 units are projected to reach their carbon peaking, followed by decreases in CE. These trends may be attributed to local policy guidance that typically emphasize the modernization of industrial structures and the gradual elimination of energy-intensive industries to decrease CE17. Many studies have demonstrated the positive impact of industrial restructuring on decreasing CE22,25. However, the CE of 13 units continues to increase, especially in units with concentrated secondary industries, such as Shiquan, Foping and Pinchang. It highlights the significant challenges faced by areas reliant on energy-intensive industries in decreasing CE, especially given the delays in the promotion and adoption of clean energy technologies45.

Under low-carbon scenario, only 9 units are projected not to reach their carbon peaking before 2030, but their CEgrowth rates slow down significantly. Therefore, the implementation of low-carbon development model is beneficial for achieving carbon neutrality. Under baseline scenario, 30 units are projected to reach their carbon peaking before 2030, with 15 of these units are projected not to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. This regional disparity may be attributed to differences in economic development levels and industrial structures27. The CEP is significantly higher in areas experiencing rapid industrialization and characterized by energy-intensive industries compared to regions where agriculture or services predominate. Under high-carbon scenario, 22 units are projected not to reach their carbon peaking before 2030. It may be attributed to the challenge of fully offsetting increased CEfrom long term reliance on traditional energy sources, despite local governments’ efforts to promote low-carbon development strategies21. Furthermore, the time lag effects related to adoption and utilization of clean energy technologies exacerbate this challenge89. Therefore, the synergy between technological transformation and policy implementation is important for achieving carbon neutrality.

Diverse land use types and their CE differences

Land serves as a crucial platform for ecosystems, and its diverse utilization patterns contribute to complex and dynamic interactions between carbon sources and sinks11,12. Different land use types show significant variations in ecological functions, anthropogenic activities and material cycling, leading to diverse characteristics of CEP and impact factors. For example, forest generally possesses robust carbon sink capacity, while urbanization and agricultural practices tend to increase carbon sources. These differences become more pronounced when land use classifications are examined in greater detail.

Taking terrace field as an example, this unique land use type is prevalent in mountainous area. Beyond traditional practices such as fertilizer application, farm machinery operations and irrigation, the maintenance and management of terrace field impact significantly CE90. The stability of terrace field is directly related to soil moisture retention and runoff control91. Damaged terrace field can easily result in soil erosion and accelerated decomposition of soil organic matter, thereby leading to increased CE92. According to an empirical study93, terrace field that is not maintained promptly may experience 10–15% increases in carbon loss from surrounding soils during a single heavy rainfall event. Furthermore, terrace field show distinct local microclimates due to topographic variations. Terrace field on sunny slopes with ample sunlight and high temperatures experiences active fertilizer decomposition, frequent microbial activity and rapid crop growth, all of which contribute to increased CE94.

Additionally, the CEof primary forest, which is stable ecosystem with minimal anthropogenic intervention, primarily result from the decomposition of senescent trees and soil microbial activities in the understory24. Trees within primary forest generally show robust carbon sink capacities due to their slow growth rates and large biomass65. Compared to artificial forest, primary forest shows more robust carbon sink capacity, with CSper unit area potentially being 30–50% higher95. As suggested by an study96, preserving the integrity of primary forest and alleviating the effects of edge disturbances are important for maintaining stable carbon sink capacity and ensuring regional carbon balance. The high integrity of ecosystem also results in large biomass few disturbances from pests and diseases97.

Besides energy-intensive industrial and mining areas, commercial area shows extremely diverse carbon sources due to the high concentration of economic activities98. Large commercial buildings consume substantial amounts of electricity to operate lighting, air conditioning and other equipment over extended periods to satisfy indoor environmental requirements99. The daily traffic flow on commercial streets is considerable, especially during peak hours, when frequent vehicle idling significantly increases exhaust emissions100. Moreover, the substantial volume of packaging waste generated by commercial operations releases CO2during its disposal process101. According to several studies102,103, the CEI per unit area in commercial area is two to three times that of residential area. It highlights the significant differences in CE across different functional areas within urban land, which are closely related to land use intensity and anthropogenic activities.

Study contributions and policy recommendations

This study aimed to develop a spatial zoning framework to effectively address land use CE challenges and contribute to achieving carbon neutrality, taking the Qinba mountain region as a case. In the process, carbon indices related to natural background, economic condition, ecological environment and resource structure were comprehensively evaluated. These indices are interwoven and collectively impact the pattern and trend of land use CE. Importantly, the CEP, a key index directly related to realizing the “dual carbon” targets, was integrated into zoning framework. It leads to more dynamic and predictive zoning results and overcomes the limitations of traditional frameworks that rely solely on historical data. Ultimately, we identified five zones that offer detailed and differentiated spatial guidance for achieving carbon neutrality.

Furthermore, numerous countries worldwide are investigating carbon neutrality pathways tailored to their specific contexts as part of the global response to climate change. By implementing the carbon neutral spatial zoning framework, zones that should prioritize CE decrease measures and those that should focus on enhancing carbon sink capacities can be identified. This zoning results not only aids in the development of targeted and operational policies for local governments but also provides the public with clear guidelines for carbon management, thereby raising social awareness and concern regarding carbon neutrality.

Based on the findings of this study, the following policy recommendations are proposed:

-

(i)

Future CE predictions for the Qinba Mountain region suggest that a long-term low-carbon development plan can realize the “dual-carbon” targets in most units, with key factors including IS and CEI. Given their cyclical nature, it is important to gradually phase out energy-intensive industries and guide enterprises toward low-carbon transformation through policy measures and regulation. Additionally, establishing industrial funds for financial support and tax incentives, along with land and electricity subsidies, can attract clean energy investments. Moreover, collaborative efforts between academia, research, and industry should focus on deploying zero-carbon technologies, with the aim of completely decarbonizing low CE industries. Technology transfer platforms should be developed to accelerate the conversion of scientific research outcomes into practical productivity.

-

(ii)

Priority should be given to protecting areas with high ecological value through strict management and restoration of ecosystems such as shrubland, forest, grassland and water area. Urban expansion should be prohibited in areas with significant ecological degradation. Ecological protection areas should be clearly defined and penalties for illegal land occupation should be increased. Additionally, carbon sink compensation mechanisms should be established to address increases in carbon sources or decreases in carbon sinks, using measures such as afforestation funded by compensation payments. Moreover, urban growth boundary, permanent basic farmland and ecological protection redline should be used to regulate and balance urban, agricultural and ecological land areas, ensuring a balanced spatial relationship between carbon sources and sinks.

-

(iii)

In spatial zoning, areas with high CE are often surrounded by carbon sinks. To manage these areas, limiting the growth of energy-intensive industries and focusing on balancing economic benefits with decreasing CE are essential. Additionally, improving energy efficiency by optimizing industrial clusters and centralizing energy facilities can be effective strategies. Areas with carbon sinks should absorb a proportion of carbon overflow from neighboring areas. Joint management strategies can be implemented, such as creating large forest belts at boundaries and decreasing land use intensity on the outskirts. Moreover, local governments should set clear development standards, promote compact cities and protect ecological land, thereby ensuring sustainable development.

Limitations

In this study, carbon emission predictions for 2030 and 2060 are used to evaluate CEP and serve as variables within carbon neutral spatial zoning framework. It enhances the applicability and specificity of zoning results by integrating future temporal considerations. Nevertheless, land use changes frequently have time lag effects on CE. For example, deforestation results in immediate CE, whereas it requires time for newly planted trees to grow and sequester an equivalent amount of carbon. Capturing these dynamic changes remains challenging, even with extended observation periods and meticulous record-keeping. This study faced limitations in this context as well. Future studies can incorporate spatial and temporal fixed effects to refine the conversion mechanism between land use and CE, thereby decreeing errors related to time lag effects. It may offer clearer insights into the distributional disparities and driving factors of spatial zoning.

Conclusion

This study analyzed the spatiotemporal dynamics of carbon indices resulting from land use pattern changes in the Qinba Mountain region, provided a spatial zoning framework for carbon neutrality and proposed optimization strategies. From 2000 to 2020, CE showed a slow increasing trend, while CS rapidly increased. NCE remained consistently negative, and both ECC and ESC exceeded 100% throughout this period. Although Ed was consistently greater than 0, Ec was still slightly damaged, especially in the central-northern region where Cf showed an increasing trend. Under both baseline and high-carbon scenarios, predicted CE initially decreased and then increased, with high-carbon scenario showing a more significant increasing trend. Under low-carbon scenario, predicted CE consistently decreased, with only nine units failing to reach their carbon peaking by 2030 and total CE projected to be 30.55 million t by 2060. The region was classified into five zones: carbon sink functional zone, low-carbon development zone, net-carbon stabilization zone, high-carbon control zone and carbon source optimization zone, encompassing 10, 33, 19, 14 and 5 units, respectively. Targeted regulatory and optimization strategies were proposed from the perspectives of upgrading agricultural carbon cycling systems, rationally planning ecological spaces, and configuring carbon sources and sinks. These strategies are expected to promote regional carbon neutrality and sustainable development.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wang, M. et al. Responses of soil organic carbon to climate extremes under warming across global biomes. Nat. Clim. Chang. 14, 98–105 (2024).

Gallagher, K. S., Zhang, F., Orvis, R., Rissman, J. & Liu, Q. Assessing the policy gaps for achieving China’s climate targets in the Paris agreement. Nat. Commun. 10, 1256 (2019).

Li, L., Huang, X. & Yang, H. Optimizing land use patterns to improve the contribution of land use planning to carbon neutrality target. Land. Use Policy. 135, 106959 (2023).

Zhao, R. et al. Key issues in natural resource management under carbon emission peak and carbon neutrality targets. J. Nat. Resour. 37 (5), 1123–1136 (2022).

Gao, S. & Zhang, H. Urban planning for low-carbon sustainable development. Sustainable Comput. Inf. Syst. 28, 100398 (2020).

Tan, F., Yang, J. & Zhou, C. Historical review and synthesis of global carbon neutrality research: A bibliometric analysis based on R-tool. J. Clean. Prod. 449, 141574 (2024).

Liu, Z. et al. Challenges and opportunities for carbon neutrality in China. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 141–155 (2022).

Pan, H. et al. Contribution of prioritized urban nature-based solutions allocation to carbon neutrality. Nat. Clim. Change. 13, 862–870 (2023).

Xu, Z. Towards carbon neutrality in China: A systematic identification of China’s sustainable land-use pathways across multiple scales. Sustainable Prod. Consum. 44, 167–178 (2024).

Li, L., Li, J., Peng, L., Wang, X. & Sun, S. Optimal pathway to urban carbon neutrality based on scenario simulation: A case study of Shanghai, China. J. Clean. Prod. 416, 137901 (2023).

Searchinger, T. D., Wirsenius, S., Beringer, T. & Dumas, P. Assessing the efficiency of changes in land use for mitigating climate change. Nature 564, 249–253 (2018).

Liu, G., Cui, F. & Wang, Y. Spatial effects of urbanization, ecological construction and their interaction on land use carbon emissions/absorption: evidence from China. Ecol. Indic. 160, 111817 (2024).

Arneth, A. et al. Historical carbon dioxide emissions caused by land-use changes are possibly larger than assumed. Nat. Geosci. 10, 79–84 (2017).

Luo, H. et al. Real-time characterization model of carbon emissions based on land-use status: A case study of Xi’an City, China. J. Clean. Prod. 434, 140069 (2024).

Lai, L. et al. Carbon emissions from land-use change and management in China between 1990 and 2010. Sci. Adv. 2(11), e1601063 (2016).

Yang, X. et al. Spatial-temporal differentiation and influencing factors of carbon emission trajectory in Chinese cities-A case study of 247 prefecture-level cities. Sci. Total Environ. 928, 172325 (2024).

Li, X. & Xing, H. Better cities better lives: how low-carbon City pilots should lower residents’ carbon emissions. J. Environ. Manage. 351, 119889 (2024).

Zhang, D., Zhao, Y. & Wu, J. Assessment of carbon balance attribution and carbon storage potential in China’s terrestrial ecosystem. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 189, 106748 (2023).

Cullenward, D., Badgley, G. & Chay, F. Carbon offsets are incompatible with the Paris agreement. One Earth. 6 (9), 1085–1088 (2023).

Hawes, J. K. et al. Comparing the carbon footprints of urban and conventional agriculture. Nat. Cities. 1, 164–173 (2024).

Kennedy, C., Ibrahim, N. & Hoornweg, D. Low-carbon infrastructure strategies for cities. Nat. Clim. Change. 4, 343–346 (2014).

Wang, L. & You, J. An integrated perspective on the spatial–temporal characteristics of China’s manufacturing carbon emissions at the regional and industry levels. Energy Rep. 10, 1688–1701 (2023).

Cao, J. et al. Agricultural soil plastic as a hidden carbon source stimulates microbial activity and increases carbon dioxide emissions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 198, 107151 (2023).

Ren, S. et al. Historical impacts of grazing on carbon stocks and climate mitigation opportunities. Nat. Clim. Change. 14, 380–386 (2024).

Kartal, M. T. The role of consumption of energy, fossil sources, nuclear energy, and renewable energy on environmental degradation in top-five carbon producing countries. Renew. Energ. 184, 871–880 (2022).

Li, Y., Yi, F. & Yuan, C. Influences of large-scale farming on carbon emissions from cropping: evidence from China. J. Integr. Agric. 22 (10), 3209–3219 (2023).

Huang, C., Ren, W., Fatima, N. & Zhu, J. Carbon intensity constraint, economic growth pressure and China’s low-carbon development. J. Environ. Manage. 348, 119282 (2023).

Hong, S., Hui, E. C. M. & Lin, Y. Relationships between carbon emissions and urban population size and density, based on geo-urban scaling analysis: A multi–carbon source empirical study. Urban Clim. 46, 101337 (2022).

Wang, G. et al. Visiting green spaces should reduce considerable carbon emissions during summer: evidence from Chongqing, China. Energy Build. 301, 113686 (2023).

Dahy, B., Issa, S. & Saleous, N. Geo-spatial modelling of carbon stock assessment of date palm at different age stages: an integrated approach of fieldwork, remote sensing and GIS. Ecol. Modell. 481, 110377 (2023).

Cellura, M., Cusenza, M. A. & Longo, S. Energy-related GHG emissions balances: IPCC versus LCA. Sci. Total Environ. 628–629, 1328–1339 (2018).

Chen, J. M. et al. Vegetation structural change since 1981 signifishouldtly enhanced the terrestrial carbon sink. Nat. Commun. 10, 4259 (2019).

Yu, Z. et al. Maximizing carbon sequestration potential in Chinese forests through optimal management. Nat. Commun. 15, 3154 (2024).

Bai, Y. & Cotrufo, M. F. Grassland soil carbon sequestration: current understanding, challenges, and solutions. Science 377, 603–608 (2022).

Leifeld, J. Carbon farming: climate change mitigation via non-permanent carbon sinks. J. Environ. Manage. 339, 117893 (2023).

Mirici, M. E. & Berberoglu, S. Terrestrial carbon dynamics and economic valuation of ecosystem service for land use management in the mediterranean region. Ecol. Inf. 81, 102570 (2024).

Li, Q., Wei, J. & Gao, W. Spatial differentiation and influencing factors of land eco-efficiency based on low carbon perspective: A case of 287 prefecture-level cities in China. Environ. Challenges. 10, 100681 (2023).

Bastos, J. R., Capellesso, E. S., Vibrans, A. C. & Marques, M. C. M. Human impacts, habitat quantity and quality affect the dimensions of diversity and carbon stocks in subtropical forests: A landscape-based approach. J. Nat. Conserv. 73, 126383 (2023).

Kaiser, A., Gold, S. & Bringezu, S. Environmental and economic assessment of CO2-based value chains for a circular carbon use in consumer products. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 184, 106422 (2022).

Li, X. & Xing, H. Regional carbon emission pathways under central-local coordination: objective constraints and collaborative incentives. Sustainable Prod. Consum. 47, 156–165 (2024).

Xu, Y., Liu, Z., Walker, T. R., Adams, M. & Dong, H. Spatio-temporal patterns and spillover effects of synergy on carbon dioxide emission and pollution reductions in the Yangtze river delta region in China. Sustainable Cities Soc. 107, 105419 (2024).

Sovacool, B. K., Rio, D., Zhang, W. & D. F. & The political economy of net-zero transitions: policy drivers, barriers, and justice benefits to decarbonization in eight carbon-neutral countries. J. Environ. Manage. 347, 119154 (2023).

Yin, H., Guo, B., Huang, X., Huo, Z. & Zhao, L. Scenario-based analysis for industrial project planning in the context of carbon peaking: case study City, China. Clean. Environ. Syst. 10, 100134 (2023).

Shi, K., Liu, G., Cui, Y. & Wu, Y. What urban Spatial structure is more conducive to reducing carbon emissions? A conditional effect of population size. Appl. Energy. 151, 102855 (2022).

Wei, T. & What STIRPAT tells about effects of population and affluence on the environment? Ecol. Econ. 72, 70–74 (2011).

Waleed, M., Sajjad, M. & Shazil, M. S. Urbanization-led land cover change impacts terrestrial carbon storage capacity: A high-resolution remote sensing-based nation-wide assessment in Pakistan (1990–2020). Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 105, 107396 (2024).

Chang, L., Mohsin, M., Hasnaoui, A. & Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. Exploring carbon dioxide emissions forecasting in China: A policy-oriented perspective using projection pursuit regression and machine learning models. Technol. Forecast. Social Change. 197, 122872 (2023).

Wang, H. & Zhang, Z. Forecasting Chinese provincial carbon emissions using a novel grey prediction model considering Spatial correlation. Expert Syst. Appl. 209, 118261 (2022).

Cao, X. et al. Heterogeneity and connection in the spatial–temporal evolution trend of China’s energy consumption at provincial level. Appl. Energy. 336, 120842 (2023).

Ala, A., Mahmoudi, A., Mirjalili, S., Simic, V. & Pamucar, D. Evaluating the performance of various algorithms for wind energy optimization: A hybrid decision-making model. Expert Syst. Appl. 221, 119731 (2023).

Luo, H. et al. Carbon emission prediction model of prefecture-level administrative region: A land-use-based case study of Xi’an City, China. Appl. Energy. 348, 121488 (2023).

Jiang, W., Deng, Y., Tang, Z., Lei, X. & Chen, Z. Modelling the potential impacts of urban ecosystem changes on carbon storage under different scenarios by linking the CLUE-S and the invest models. Ecol. Modell. 345, 30–40 (2017).

Ma, S., Huang, J., Wang, X. & Fu, Y. Multi-scenario simulation of low-carbon land use based on the SD-FLUS model in Changsha, China. Land. Use Policy. 148, 107418 (2025).

Wu, Q., Wang, L., Wang, T., Ruan, Z. & Du, P. Spatial-temporal evolution analysis of multi-scenario land use and carbon storage based on PLUS-InVEST model: A case study in Dalian, China. Ecol. Indic. 166, 112448 (2024).

Su, K. & Lee, C. M. When will China achieve its carbon emission peak? A scenario analysis based on optimal control and the STIRPAT model. Ecol. Indic. 112, 106138 (2020).

Ke, S., Zhang, Z. & Wang, Y. China’s forest carbon sinks and mitigation potential from carbon sequestration trading perspective. Ecol. Indic. 148, 110054 (2023).

Wang, A. et al. Investigating drivers impacting vegetation carbon sequestration capacity on the terrestrial environment in 127 Chinese cities. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 16, 100213 (2022).

Tao, F. et al. Microbial carbon use efficiency promotes global soil carbon storage. Nature 618, 981–985 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Carbon and water relationships change nonlinearly along elevation gradient in the Qinghai Tibet plateau. J. Hydrol. 628, 130529 (2024).

Mo, L. et al. Integrated global assessment of the natural forest carbon potential. Nature 624, 92–101 (2023).

Abudu, H., Wesseh, P. K. & Lin, B. Climate bonds toward achieving net zero emissions and carbon neutrality: evidence from machine learning technique. J. Manage. Sci. Eng. 9 (1), 1–15 (2024).

Qin, J. et al. Synergizing economic growth and carbon emission reduction in China: A path to coupling the MFLP and PLUS models for optimizing the territorial Spatial functional pattern. Sci. Total Environ. 929, 171926 (2024).

Li, Y., Wei, W., Zhou, J., Hao, R. & Chen, D. Changes in land use carbon emissions and coordinated zoning in China. Environ. Sci. 44 (3), 1267–1276 (2023).

Chen, Y., Qiao, F., Lu, H. & Xia, J. Water-carbon-ecological footprint change characteristics and its balance analysis in the triangle of central China. Acta Ecol. Sinica. 42 (4), 1368–1380 (2022).

Zhu, W., Li, S. & Zhu, L. Ecosystem service footprint flow and the influencing factors within provinces, China. Geogr. Res. 38 (2), 337–347 (2019).

Cai, X., Xiang, H. & Zheng, H. Impact of energy consumption patterns on peak emissions in China’s carbon neutralisation process. Energy Strategy Rev. 55, 101501 (2024).

Liu, H., Liu, Q., He, R., Li, F. & Lu, L. Decomposition analysis and decoupling effects of factors driving carbon emissions produced by electricity generation. Energy Rep. 11, 2692–2703 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. A review on carbon emission accounting approaches for the electricity power industry. Appl. Energy. 359, 122681 (2024).

Xu, Y. et al. Identification of ecologically sensitive zones affected by climate change and anthropogenic activities in Southwest China through a NDVI-based spatial-temporal model. Ecol. Indic. 158, 111482 (2024).

Haldar, S., Choudhury, M., Choudhury, S. & Samanta, P. Trend analysis of long-term meteorological data of a growing metropolitan City in the era of global climate change. Total Environ. Res. 7, 100056 (2023).

Li, S., Li, Y., Wang, M. & Luo, G. The evolution of land use structure in karst Valley area based on micro-space unit. J. Nat. Resour. 35 (4), 908–924 (2020).

Chen, Q., Gong, Z., Wu, J. & Wang, T. Does digital transformation affect carbon performance through talent? The moderating role of employee structure. J. Clean. Prod. 435, 140581 (2024).

Yasmeen, R., Padda, I. U. H. & Shah, W. U. H. Untangling the forces behind carbon emissions in China’s industrial sector-A pre and post 12th energy climate plan analysis. Urban Clim. 55, 101895 (2024).

Yang, J., Ma, R. & Yang, L. Spatio-temporal evolution and its policy influencing factors of agricultural land-use efficiency under carbon emission constraint in Mainland China. Heliyon 10(4), e25816 (2024).

Roberts, S. H., Foran, B. D., Axon, C. J. & Stamp, A. V. Is the service industry really low-carbon? Energy, jobs and realistic country GHG emissions reductions. Appl. Energy. 292, 116878 (2021).

McManamay, R. A. et al. Dynamic urban land extensification is projected to lead to imbalances in the global land-carbon equilibrium. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 70 (2024).

Shi, K., Chen, Y., Li, L. & Huang, C. Spatiotemporal variations of urban CO2 emissions in China: A multiscale perspective. Appl. Energy. 211, 218–229 (2018).

Harper, A. B. et al. Land-use emissions play a critical role in land-based mitigation for Paris climate targets. Nat. Commun. 9, 2938 (2018).

He, T. et al. Meta-analysis shows the impacts of ecological restoration on greenhouse gas emissions. Nat. Commun. 15, 2668 (2024).

Feng, X., Fu, B., Lu, N., Zeng, Y. & Wu, B. How ecological restoration alters ecosystem services: an analysis of carbon sequestration in China’s loess plateau. Sci. Rep. 3, 2846 (2013).

Chen, Z. et al. Evaluating emission reduction potential at the 30–60 dual carbon targets over China from a view of wind power under climate change. Sci. Total Environ. 900, 165782 (2023).

Han, C., Wang, G. & Yang, Y. An assessment of sustainable wellbeing and coordination of mountain areas: A case study of Qinba mountain area in China. Ecol. Indic. 154, 110674 (2023).

Hinojo-Hinojo, C. et al. Native shrubland and managed Buffelgrass savanna in drylands: implications for ecosystem carbon and water fluxes. Agric. Meteorol. 268, 269–278 (2019).

Liu, Z. et al. Precipitation consistently promotes, but temperature oppositely drives carbon fluxes in temperate and alpine grasslands in China. Agric. Meteorol. 344, 109811 (2024).

Wang, C., Li, B., Li, J., Bai, J. & Zhang, Y. Adaptive management of mountain ecosystems based on carbon sequestration: based on the state-flow-utility framework. Ecol. Indic. 168, 112703 (2024).

Chabuz, W. et al. Impact of the type of use of permanent grasslands areas in mountainous regions on the floristic diversity of habitats and animal welfare. Global Ecol. Conserv. 19, e00629 (2019).

Duan, J. et al. Environment and management jointly shape the Spatial patterns of plant species diversity of moist grasslands in the mountains of Northeastern Yunnan. Plant. Divers. 46 (6), 744–754 (2024).

Huang, D. Coupling coordination analysis between urban park wetland water ecological construction and carbon emissions. Desalin. Water Treat. 313, 290–299 (2023).

Leitão, J., Ferreira, J. & Santibanez-González, E. New insights into decoupling economic growth, technological progress and carbon dioxide emissions: evidence from 40 countries. Technol. Forecast. Social Change. 174, 121250 (2022).

Ye, C. et al. Lateral CO2 emission from eroded scarps and terrace sidewalls: A non-negligible but long-ignored carbon source. CATENA 245, 108272 (2024).

He, Z. et al. Change in soil organic carbon after slope cropland changed into terrace in Southwest China. CATENA 248, 108580 (2025).

Driscoll, B. A., Krzic, M., Comeau, L. P., Eskelson, B. N. I. & Li, S. Short-term response of soil aggregate stability and labile carbon to contour tillage, diversion terrace, grassed waterway, and tile drainage implementation. Can. J. Soil. Sci. 103 (3), 394–405 (2023).

Zhao, J. et al. Greenhouse gas emissions from the growing season are regulated by precipitation events in conservation tillage farmland ecosystems of Northeast China. Sci. Total Environ. 948, 174716 (2024).

Hu, Y., Wang, Z., Wang, R., Yao, L. & Guo, S. Slope sensitivity: A coefficient to represent the dependency of soil CO2 emissions to slope gradients. CATENA 193, 104659 (2020).

Li, Y., Peng, Y., Cheng, W. & Peng, H. Spatial-temporal evolution and multi-scenario prediction of carbon emissions from land use in the adjacent areas of nature reserves. Ecol. Indic. 170, 113047 (2025).

Tien, N. D. et al. Toward high-integrity forest carbon market of ethnic minority groups in Dak Lak province, Vietnam. Heliyon 10(22), e39998 (2024).

Maure, L. A. et al. Biodiversity and carbon conservation under the ecosystem stability of tropical forests. J. Environ. Manage. 345, 118929 (2023).

Yang, Y. et al. Optimizing urban functional land towards dual carbon target: A coupling structural and Spatial scales approach. Cities 148, 104860 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Evaluation of the impact of urban morphology on commercial Building carbon emissions at the block scale-A study of commercial Buildings in Beijing. J. Clean. Prod. 408, 137191 (2023).

Wang, W. & Su, W. Impacts of urban block form on carbon and pollutant emissions from urban life in China from the perspective of regional differences. Sustainable Cities Soc. 115, 105849 (2024).

Yang, Y. & Takase, T. Spatial characteristics of carbon dioxide emission intensity of urban road traffic and driving factors: road network and land use. Sustainable Cities Soc. 113, 105700 (2024).

Huo, T., Du, Q., Qiao, Y., Cai, W. & Cai, Y. Exploring the dynamic evolutionary trajectories for urban residential Building carbon emissions toward 2060: evidence from the HSCW zone in China. J. Clean. Prod. 457, 142310 (2024).

Liu, H. et al. A coupled STIRPAT-SD model method for land-use carbon emission prediction and scenario simulation at the County level. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 108, 107595 (2024).

Funding

This study was supported by the Youth Project of Henan Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Grant number 232300420433) and the Young Scientists Fund of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number 42201110).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H. and Z.S.; methodology, J.H.; software, J.H.; validation, J.H., Z.S. and H.X; formal analysis, J.H. and W.Z.; investigation, J.H. and Y.Y.; resources, J.H., Z.S. and W.Z.; data curation, J.H.; writing—original draft preparation, J.H. and W.Z.; writing—review and editing, J.H.; visualization, J.H.; supervision, Z.S.; project administration, Z.S.; funding acquisition, Z.S. and W.Z. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huo, J., Shi, Z., Zhu, W. et al. Carbon neutral spatial zoning and optimization based on land use carbon emission in the qinba mountain region, China. Sci Rep 15, 10326 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95156-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95156-x