Abstract

With a population nearing 15 million, the metropolitan area of Tehran faces numerous environmental challenges due to inadequate urban strategies and hasty, ineffective planning. The primary objective of this research is to investigate the Urban Heat Island (UHI) climatology in the metropolis of Tehran. To achieve this, daily Land Surface Temperature (LST) data from the MODIS-Aqua, with a spatial resolution of 1 km, was utilized over a 19-year period (2003–2021). This study delves into various climatic characteristics, including the urban-rural temperature difference, urban heat hotspots, the structure of the Surface Urban Heat Island (SUHI), trends in LST changes, and the roles of elevation and vegetation cover in the spatial distribution of LST, at both monthly and annual scales. Findings reveal that, compared to daytime Aqua-MODIS LST data, nighttime data provides a more reliable means of detecting and studying the SUHI in Tehran throughout the year. Additionally, the employment of nighttime data significantly reduces seasonal variations and month-to-month fluctuations in the temperature difference between the urban warm core and surrounding areas in Tehran. A climatological analysis of nighttime LST revealed a mean annual temperature difference of 6.17 °C between Tehran and its surrounding suburbs. This difference fluctuated monthly, ranging from a minimum of 5.73 °C in November to a maximum of 6.49 °C in September. Overall, the smallest temperature differences occurred during autumn and spring, while the largest differences were observed in summer. However, autumn and summer exhibited the greatest and least interannual variability, respectively. Furthermore, over the 19-year period, the annual temperature difference between the urban and suburban areas ranged from a minimum of 5.09 °C (2020) to a maximum of 6.70 °C (2008). The SUHI analysis suggests that Tehran, due to its surrounding mountainous terrain and numerous suburban developments, does not exhibit a classic UHI with a pronounced temperature difference. Moreover, the results indicate a rising temperature trend in the city. Specifically, the second decade of the study period witnessed a notable increase in positive LST anomalies within Tehran. The analysis reveals a significant increase in Tehran’s surface temperature, with a rate of 0.74 °C per decade, amounting to a total increase of 1.48 °C. Concurrently, a discernible upward trend in the temperature differential between the urban and suburban areas has been observed over the last two decades. A comparative study of the roles of elevation and vegetation cover in LST distribution indicates that the temperature difference between the urban and suburban areas of Tehran is more closely related to elevation changes than to vegetation distribution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cities are considered the primary locus of environmental challenges on Earth in the 21st century. Increasing frequency of extreme weather events, high concentrations of air, water, and soil pollution, urban waste management issues, and acute resource scarcity have turned cities, particularly those in developing countries, into epicenters of environmental crises. The rapid growth of urban populations and ecological challenges due to global warming have made the study of urban climate crucial in recent years1. In 21st-century mega-cities, the expansion of built-up areas and reduction in vegetation cover have led to temperature increases and the development and spread of Urban Heat islands (UHI), presenting a persistent environmental challenge in urban climates2,3.

The Surface Urban Heat Island (SUHI) is a symbolic phenomenon in urban climates characterized by a dome of stagnant warm air4,5 or an island6 effect in urban areas, displaying temperature variances from adjacent rural regions7. Urban areas retain more heat during the day than rural surfaces. At night, energy absorbed by the ground is re-radiated into space as long-wave radiation and then trapped by urban canyons. The vertical walls of buildings act as deep and narrow canyons that trap shortwave radiation during the day, hindering the release of infrared energy at night due to a reduced Sky View Factor (SVF). Consequently, Passive Radiative Cooling in buildings at night is significantly limited in urban areas8. In contrast, rural environments cool much faster than urban areas from afternoon to night due to a continuous decrease in shortwave radiation since their capacity to retain absorbed energy is lower. Essentially, the UHI peaks mainly at night when the temperature contrast between urban and rural areas is most significant9. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced in arid urban environments, where diurnal temperature differentials are exacerbated by low humidity, limited moisture availability, and intense solar radiation10.

Tehran, one of the largest metropolises in Western Asia11 and the first major city in Iran12, has undergone significant spatial expansion and population growth over the past two to three decades13,14. As the nation’s capital and primary cultural hub, Tehran attracts significant economic and commercial investment, positioning it as a key national investment destination. The financial foundation of Tehran’s municipality rests upon revenue generated from housing sales to its residents. This mechanism has not only resulted in the significant appreciation of land and housing values, thereby establishing them as critical capital commodities. It has also rendered this economic approach the primary factor for the city’s physical growth, contributing to Tehran’s status as one of the most dynamic and unstable cities in the Middle East in recent years15,16.

Tehran metropolis has a population of over 15.98 million people, with 54.4% residing in the city and the remainder scattered in surrounding areas, particularly in new towns and small satellite cities14. The spatial expansion and population growth of Tehran without adhering to regulations and without considering long-term planning has led to the development of an unsuitable urban system with numerous negative impacts and environmental challenges. In addition to air and soil pollution, waste, water, and energy resource shortages, the SUHI expansion and temperature increase are significant issues. Over the past four decades, Tehran’s surface temperature has notably increased in both summer and winter. Continuing this trend may lead to the elimination of the cold season in Tehran in the future17.

Due to inadequate urban design, a noticeable decrease in vegetation coverage18, and increased built-up areas, Tehran’s UHI size and intensity have significantly increased in recent years17. Consequently, the UHI Intensity (UHII) in Tehran has risen by an average of about 2.02 °C over the past three decades19. Additionally, from 1985 to 2019, built-up areas within Tehran expanded by 88%, with this trend expected to continue due to prevailing economic conditions20. These factors have led to the formation of hotspots in western and southwestern regions and cold spots in northern Tehran in recent years21. These changes have resulted in an increase in extreme events due to climate change22, heightened water and energy consumption23, increased air pollution24, and a decline in human health levels25 within the city of Tehran. Additionally, the population density in Tehran reflects the impact of human activities on energy consumption and the exacerbation of UHI. The proximity of densely populated residential areas to UHI-affected regions heightens the risk of respiratory and heart diseases among residents, making daily living conditions more challenging for the elderly and children26. Consequently, in response to escalating environmental and ecological concerns in Tehran’s expansion, several studies have examined UHI using satellite data17,27. Some studies revealed that the intensity of UHI in Tehran exceeded the average (approximately 0.067) due to the dominance of climate change and air pollution in recent years28.

With physical expansion and rapid population growth in recent decades, Tehran’s urban climate has undergone significant changes but has been less addressed by urban management and policymakers. Urban climate change and spatial patterns of UHI distribution in the metropolitan area of Tehran are among the aspects that lack sufficient understanding despite numerous past studies. For instance, while extensive studies have been conducted on average UHII at night between cities and suburbs in various geographical regions worldwide29,30,31, a comprehensive study accurately depicting temperature differences between the city center and suburbs within the Tehran metropolitan area has not been completed yet.

Questions such as the true spatial pattern of Tehran’s UHI, the extent of temperature differences between the city center and suburbs across various seasons and months, and the spatial patterns and frequencies of hotspots within Tehran throughout the year remain unanswered. The evolution of heat island and surface temperatures in Tehran over recent decades requires scrutiny. Therefore, a comprehensive climatological study on Tehran’s heat island is essential, utilizing MODIS Aqua data spanning an extended period with fine horizontal resolution to address these inquiries effectively. This research leverages MODIS Aqua data due to its suitable satellite passing times, fine horizontal resolution, and appropriate temporal intervals for research purposes32,33. The MODIS Land Surface Temperature (LST) data, which offers a 1-kilometer horizontal resolution, facilitates the examination of SUHI on a daily, monthly, and seasonal basis34,35,36,37,38,39,40.

Despite numerous studies conducted on the city of Tehran using various approaches—such as remote sensing40, modeling41, and statistical analysis on station data42—there has yet to be a comprehensive long-term investigation of the structure and characteristics of the UHI from a climatic perspective. Addressing the gap in comprehensive, long-term climatic studies of Tehran’s UHI, this research introduces a novel analysis of MODIS satellite data, providing insights into UHI dynamics. It uniquely offers an extended temporal analysis of LST and UHI, precise quantification of UHI intensity across varying time scales, and an exploration of factors influencing temperature disparities between urban and suburban areas. Furthermore, it provides a detailed spatial analysis of LST, UHI, and hotspot distribution across Tehran’s districts and assesses two-decade temperature trends, informing urban planning and UHI mitigation strategies with evidence-based data.

Data and methods

Study area

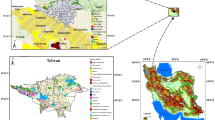

Tehran, the most populous metropolis in Iran43, spans an area of 730 square kilometers44. Figure 1 illustrates the geographical features and Land Use (LU) of Tehran.

Furthermore, the majority of land use in the northern and eastern outskirts is related to mountains and barren lands. Tehran is situated between two mountain valleys and a desert45, terminating in mountainous regions in the north, east, and southeast, and desert areas in the south. To the north, it is surrounded by the Alborz mountain range; to the east and southeast by the heights of Qasr-e Firuzeh and Bibi Shahr Banu; and to the south and southwest by the flat plains of Varamin and Shahriar. The southern and western parts have developed on vast flat plains, although urban growth in the northern and eastern mountains has been limited44. The elevation of Tehran above sea level varies from 1800 m in the north to 1200 m in the center and 1050 m in the south46,47,48. In the southern urban regions (15–20) and surrounding areas (west, southwest, south, and southeast), the elevation ranges from 860 to 1183 m. In the city center (regions 2–14, 21, and 22), it ranges from 1183 to 1506 m, while in the northern part of the city (region 1 and north of regions 1–5), it ranges from 1506 to 1830 m.

The city’s south and north exhibit distinct climates. The north is cold and dry, while the south is warm and dry. Tehran generally experiences a semi-arid, cold climate with continental traits, characterized by hot summers and cold, dry winters. The average maximum temperature is 43 °C, and the average minimum temperature is -15 °C (Fig. 1a)49,50.

(a) Topography of Tehran derived from 30-second resolution data. (b) Land use map of Greater Tehran based on 10-meter Sentinel-2 satellite data. (c) Longitudinal and latitudinal profiles from south to north and west to east, delineating central area boundaries and surrounding suburbs. The data presented in Fig. 1a were prepared using a Digital Elevation Model (DEM). URL link: https://data.nextgis.com/en/region/IR/dem. The map was generated using ArcGIS Desktop, specifically ArcMap and ArcScene (ESRI ArcGIS Desktop, Release 10). Redlands, CA: Environmental Systems Research Institute. Version number: ArcGIS Desktop 10.8.0 (ArcMap 10.8.0 and ArcScene 10.8.0). URL link: https://www.esri.com (2020). The data in Fig. 1b were prepared using the Esri Sentinel-2 Land Cover Explorer. URL link: https://livingatlas.arcgis.com/landcover. The map was generated in ArcGIS Desktop using ArcMap (ESRI ArcGIS Desktop, Release 10). Redlands, CA: Environmental Systems Research Institute. Version number: ArcGIS Desktop 10.8 (ArcMap 10.8). URL link: https://www.esri.com (2020). The data presented in Fig. 1c were prepared using Earth data. Cite: AppEEARS Team. Application for Extracting and Exploring Analysis Ready Samples (AppEEARS). Version X.X. NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center (LP DAAC), USGS/Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center, Sioux Falls, South Dakota, USA. URL link: https://appeears.earthdatacloud.nasa.gov. Subsequently, the data were modified using Climate Data Operators (CDO). Version number: 2.0.4. URL link: https://code.mpimet.mpg.de (2022). The map was generated using the Grid Analysis and Display System (GrADS). Version number: 2.2.1.oga.1. URL link: http://cola.gmu.edu (2019). Both CDO and GrADS were utilized on Ubuntu Desktop Linux. Version number: 22.04 LTS. URL link: https://ubuntu.com (2022). Finally, Fig. 1 was enhanced using Adobe Photoshop Desktop. Version number: 24.0. URL link: https://www.adobe.com (2022), and Paint.NET. Version number: 5.0.13. URL link: https://www.getpaint.net (2024).

In the mountainous areas of Tehran, high elevation and legal restrictions limit construction and habitation. Consequently, the physical development of Tehran has primarily occurred in the foothill region and plains along the southern slopes of the Alborz Mountains. The southern parts of the city have expanded across a vast, flat plain. In contrast, the northern and eastern elevations impose limitations on urban development in those areas, while specific geographical conditions in the arid south and high groundwater levels further restrict growth in that region. For this reason, the western part of the city is considered the most suitable area for development due to its relatively favorable geographical conditions. New towns and cities have mainly been established and developed in this direction. Moving from south to north, significant changes occur in both natural environmental conditions and social factors such as spatial value, access to services, and specific amenities. It can be said that there is a geographical gradient that aligns with social gradients in Tehran; in other words, the city’s topography reflects its economic and social landscape to some extent46.

Tehran is divided into 22 urban districts51. Based on the land use map of Tehran and its suburbs, the built-up regions in Tehran are growing and expanding hastily. Moreover, crops and bare lands occupy the most significant area in these mentioned suburbs. Significantly, the study area demonstrates a markedly low proportion of green cover and water bodies (Fig. 1b).

Data

The present study aligns with the findings of previous research conducted by Zargari et al.40. Specifically, this study confirms that the MODIS Aqua satellite is more suitable than the Sentinel-3 and Landsat 8 satellites for investigating the UHI effect in Tehran. Consequently, the current research utilized long-term MODIS data to conduct a comprehensive climatic study of Tehran’s heat island from various perspectives.

In a previous study by Zargari et al.40, the UHI effect in Tehran was analyzed using three satellites: MODIS Aqua, Sentinel-3, and Landsat 8. The objective was to identify the most suitable satellite for studying Tehran’s heat island, considering factors such as appropriate overpass times, a long-term period, and suitable temporal (day and night) and spatial resolutions.

The findings indicate that while Landsat 8 offers superior spatial resolution compared to Sentinel-3 and MODIS Aqua and Terra and provides a longer time series than the other satellites, its unsuitable imaging time, unsuitable temporal resolution, and lack of nighttime data render it impractical for studying the climatology of UHI. Notably, satellite imagery captured every 16 days reduces the temporal value of this data. Additionally, Landsat 8’s imaging window does not provide complete coverage for studying UHI in Tehran and its surroundings40. Additionally, although Sentinel-3 provides both day and night data, its inappropriate imaging times and short time series also make it unsuitable for climatic studies in Tehran. Therefore, given the importance of climatology and spatial analysis across the entire area, MODIS Aqua emerges as the only satellite that meets these climatic needs.

Currently, MODIS Aqua is considered the most appropriate option based on thorough examination in previous research to show a better UHI at night40. It was determined that due to its suitable overpass time from south to north (1:30 am), adequate temporal resolution (twice daily), appropriate spatial resolution (1 km), relatively long data coverage duration (since 2002), effective Split-Window (SW) algorithm for arid regions40 such as Tehran, significant enhancement of data resolution capabilities, and access to corrected data ready for research on various servers in suitable formats, the use of MODIS Aqua data for UHI research has significantly increased in recent years40. Furthermore, utilizing the nighttime LST data of MODIS for studying UHI is particularly valuable for countries like Iran that experience a severe lack of climatic data in urban areas.

In this study, we investigated the SUHI of Tehran using MODIS Aqua LST data. This choice was made due to the suitable characteristics of MODIS in determining changes in LST and vegetation cover in both the city and suburban52,53 areas over a 19-year period (2003–2021) to calculate the SUHI effect in the Tehran metropolitan area. Recent studies have clarified that the MODIS Aqua products are more suitable than the other remote-sensed products, such as LANDSAT and Sentinel-3, for studying the Tehran UHI40. This data also successfully depicted spatial and temporal variations of nighttime LST over Iran in daily and monthly scales with minimum underestimation54.

The study utilized MODIS Aqua LST data (MYD11A1) for each grid with a spatial resolution of 1 km and a temporal resolution twice daily during daytime (1:30 PM) and nighttime (1:30 AM), employing the SW algorithm for MODIS Aqua version 6.1, which features an improved algorithm for detecting LST55 (Table 1). The SW algorithm effectively removes atmospheric influences by utilizing the brightness temperature (BT) from two neighboring TIR channels at the top of the atmosphere, making it a commonly used method56. In arid regions, data errors tend to be minimal57.

This study benefits from the use of both day and night data. To determine the optimal time for studying the UHI effect in Tehran, it was necessary to compare heat island conditions and surface temperature variations during both day and nighttime. This comparison is crucial because urban heat islands exhibit significant differences throughout the day across various regions of the world and in different climatic zones, including tropical58, subtropical40, desert, and oceanic regions59. In some locations, midday hours are ideal for studying the heat island effect60, while in others, nighttime is more appropriate. Moreover, to accurately assess temperature differences between the city and its surroundings on a daily, monthly, and yearly basis, it is essential to first identify when the maximum difference occurs. Therefore, this study initially calculated temperature differences between the city and its surroundings separately for day and nighttime hours. Based on the results, greater emphasis was placed on nighttime hours. The comparative analysis of temperatures between the day and night revealed that in a city with a dry climate in a subtropical region, the maximum temperature difference between the city and its surroundings occurs at night40.

One of the key improvements in the LST product Collection 6 is the optimization of the day/night algorithm for enhanced performance in desert regions. This optimized algorithm demonstrates superior validation compared to Collections 5 and 4.161. The accuracy of LST MODIS version 6 has significantly increased from approximately 4.5 K to 1 K at various validation sites, surpassing LST MODIS version 562,63. The latest product, LST MODIS version 6, has been available since 2016, with version 6.1 launched in 2020. It is advisable to utilize LST MODIS Collection 6.1 due to its superior quality over Collection 4.1 and Collection 5 products64. The advantages of the MODIS day/night LST algorithm include optimized atmospheric temperature and water vapor half-angle parameters for precise LST retrieval, eliminating the need for complete inversion of surface variables and atmospheric half-angles65,66,67. Additionally, monthly NDVI data version 6.1 (MYD13A3) with a spatial resolution of 1 km was employed alongside gridded surface data level-3 and two-minute topographic data for this study.

The C6.1 product is identical in format to the C6 product. Reprocessing of the C6.1 does not involve any changes to the scientific algorithm used in its production. Any enhancements or alterations in the C6.1 product, compared to the previous major collection reprocessing (C6), stem from modifications and improvements made to the calibration approach used in generating Aqua MODIS L1B products and adjustments to the polarization correction employed in this reprocessing collection68.

Methods

To examine the SUHI in Tehran, several preprocessing steps were conducted on the MODIS Aqua long-term data. These steps involved converting from Kelvin to Celsius and determining monthly and annual long-term averages over 19 years (2003–2021). Following this, calculations were performed according to the subsequent procedures.

Day and nighttime LST

Monthly day and night maps were created to interpret and identify the highest and lowest temperatures in urban areas and their surroundings. This section of the study illustrates the variations in the highest and lowest temperatures across cities and their outskirts during both day and night.

Longitudinal and latitudinal LST profiles for the Tehran metropolitan area were plotted for different seasons based on annual temperature variations during the day and night. A central box was defined over the central districts of Tehran for comparison with the outskirts aligned along meridional and diurnal axes, considering the occurrence of the highest temperatures in the central region. The temperature differences between the central box and other areas aligned latitudinally from south to north and longitudinally from west to east over the city and its outskirts were calculated during both day and night (see Fig. 1c). The geographical coordinates of the central box and surrounding outskirts are detailed in Table 2.

The temperature difference starts from the southernmost and westernmost outskirts, extending to the northernmost and easternmost outskirts. This research section aims to offer a comprehensive perspective on daily and nightly LST in the Tehran metropolitan area and their surroundings, facilitating effective utilization of LST data for studying UHI effects in metropolitan districts based on existing mechanisms.

Trend changes in day and nighttime LST

Changes in surface temperature trends over a 19-year period for a major city were analyzed using Sen’s slope test in R and RStudio software. The study examined monthly and yearly mean minimum/maximum temperatures to determine if these changes were increasing or decreasing during the observed months and years. The non-parametric Sen’s slope method, as proposed by Theil (1950)69 and further developed by Sen (1968)70, was employed to estimate the actual slopes of time series trends. This approach involves analyzing differences between time series observations and is suitable when the trend is linear, as the Teil-Sen approach represented in Eq. 1.

where xt and xt∗ are data values at time t and t*, respectively. In Eq. 1, t > t*, the median of these n values of Ti is represented by Sen’s slope of estimation (true slope) in Eq. 1.

Sen’s estimator Qmed was calculated using Eq. 3 depending upon whether n was odd or even. Then, Qmed was computed using a 100% (1 − α) confidence interval using a non-parametric test depending upon a normal distribution. A positive value of Qi indicates an upward trend, while a negative value characterizes a downward trend of time series data71. Sen’s slope estimator is a non-parametric method used to assess trends in time series data, particularly useful when the data exhibits variability or outliers. In environmental and atmospheric sciences, it can be applied to analyze trends in various environmental parameters like temperature, precipitation, air quality, and pollutant levels72. It has some features as described below:

Robustness to Outliers: Environmental and atmospheric data can be noisy and subject to outliers, such as extreme weather events or anomalous pollution spikes. Sen’s slope provides a way to estimate trends without being unduly influenced by these outliers.

Non-parametric Nature: Unlike methods like linear regression, Sen’s slope doesn’t assume any specific distribution or linearity in the data, making it versatile for complex environmental data that might not follow simple patterns.

Simplicity and Interpretability: The method provides a clear, straightforward estimate of the trend slope, making it easy to interpret in the context of environmental and atmospheric research.

In summary, Sen’s slope is a valuable tool in environmental and atmospheric sciences for analyzing trends in time series data, especially when robustness and non-parametric flexibility are required to deal with the complexities of real-world environmental data72. This method is then employed to calculate and analyze temporal changes in LST trends for the major city.

Nighttime SUHI

To evaluate the intensity and extent of the UHI in the Tehran metropolitan area over 19 years, we first analyze UHI maps using Eq. 4. This equation essentially calculates urban heat islands based on the temperature variance between the city and its environs40.

Here, LSTi represents the same LST for each pixel in a specific image. LSTmax is the maximum value of LST, and LSTmin is the minimum value of LST from that same LSTi image. The use of this index enables the normalization of the LST values between 0 and 1 for each pixel in an image. To determine SUHI, an efficient method is required that enhances understanding effectively.

Temperature difference between Tehran and its surrounding suburbs

To calculate the temperature difference between the city and its outskirts, initially, daily and nightly surface temperature data were examined using Standard Deviation (SD) to determine whether the data distribution is scattered or clustered during the day and night. Subsequently, the optimal data (either day or night) should be selected to investigate the temperature difference between the city and its outskirts.

The SD is the most frequently utilized metric for variability since it takes into account all the scores in the dataset during its calculation and is expressed in the original measurement units. The SD is a statistical measure of dispersion that quantifies how spread out a dataset is in relation to its mean. It is computed as the square root of the variance by assessing how much each point deviates from the mean. A low SD suggests that data points are closely clustered around the mean, whereas a high SD indicates more significant data dispersion. Essentially, an SD near zero implies that data points are very near the mean, while a larger SD suggests that data points are more widely distributed from the mean. Equation 5 is used to calculate the SD.

In this context, σ represents the standard deviation, xi stands for each value in the dataset, \(\:\overline{x}\) denotes the mean, and n signifies the number of data points.

In this section, the monthly, seasonal, and annual temperature variances between the Tehran metropolis and its surrounding suburbs were computed. The geographical coordinates of the central area of Tehran and its suburbs will be detailed in Table 3; Fig. 1b. Notably, the northern suburbs of Tehran have a cold climate with year-round snow cover due to the Alborz Mountains. To ensure temperature accuracy, the analysis of UHI nighttime temperature differences excluded these northern suburbs, focusing solely on the eastern, western, and southern suburbs. The UHII was employed to determine the city-suburb temperature variation (Eq. 6). Subsequently, temperature difference graphs were created and analyzed.

where Tu represents city temperature and Tr represents suburb temperature.

Nighttime hotspots

The frequency of hotspots was calculated in Table 4 to determine where the maximum hotspots occur in Tehran. Nightly temperature thresholds for each month and year were defined as a 19-year average. “When temperatures exceed these thresholds, they are identified as hotspots”.

The investigation of elevation and NDVI in relation to LST

In addition, temperature is examined concerning geographical components (elevation and vegetation cover) in longitudinal and latitudinal directions to determine their effects on Tehran, particularly in terms of experiencing the SUHI phenomenon. The analysis of the relation between NDVI and elevation indicated that NDVI rises as elevation increases73. Additionally, there was a negative correlation observed between NDVI and LST74, as well as between elevation and LST75.

The intensity of plant reflection used in calculating NDVI depends on leaf area, chlorophyll content, and plant moisture. As vegetation cover becomes denser and of higher quality, NDVI values increase and approach unity. In very dense vegetation cover, with increasing plant coverage, the reflection in the red wavelength does not change, while the near-infrared reflection increases. This causes NDVI saturation, where its value remains constant. Different NDVI values represent various types of coverage; for instance, NDVI values vary from − 1 to 1. Negative values usually signify clouds and water, while values near zero indicate bare soil. Higher positive NDVI values, from 0.1 to 0.5 for sparse vegetation to 0.6 and above for dense green vegetation, reflect greater vegetation levels76,77. NDVI is calculated using differences in the red and near-infrared parts of the electromagnetic spectrum and is formulated as:

where Red and NIR stand for the spectral reflectance measurements in the visible red and near-infrared regions, respectively.

Results

The climatology of daytime LST

The LST is a crucial parameter for studying energy balance, climate changes, various physical and chemical processes on the surface, and the UHI effect78,79. Figure 2 displays the spatial distribution of the 19-year average daily LST monthly for the Tehran metropolis and its suburbs. In January and December, temperatures in the suburbs rise compared to Tehran, with these conditions becoming more pronounced in subsequent months. In November, February, and March, LST values in suburbs other than the north are higher than those in the city. Between April and October, temperature increases in Tehran and its surrounding suburbs follow a similar trend. Consequently, in April and October, temperature values are nearly equal between the city and its suburbs, although some parts of the eastern, southeastern, southern, and southwestern suburbs exhibit scattered higher values compared to the city. In May and September, temperatures in other suburbs are generally higher than those in the northern suburbs and northern parts of the city. From June to August, temperatures in the suburbs increase significantly to the extent that it can be stated that the entire area (city and suburbs) experiences elevated temperatures regardless of Tehran’s urban boundaries.

Spatial distribution of 19-year monthly average of daytime LST in Tehran and its suburbs, highlighting the city’s 22 administrative districts. The data presented in this Figure were prepared using Earth data. Cite: AppEEARS Team. Application for Extracting and Exploring Analysis Ready Samples (AppEEARS). Version X.X. NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center (LP DAAC), USGS/Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center, Sioux Falls, South Dakota, USA. URL link: https://appeears.earthdatacloud.nasa.gov. Subsequently, the data were modified using Climate Data Operators (CDO). Version number: 2.0.4. URL link: https://code.mpimet.mpg.de (2022). The map was generated using the Grid Analysis and Display System (GrADS). Version number: 2.2.1.oga.1. URL link: http://cola.gmu.edu (2019). Both CDO and GrADS were utilized on Ubuntu Desktop Linux. Version number: 22.04 LTS. URL link: https://ubuntu.com (2022). Finally, Fig. 2 was enhanced using Adobe Photoshop Desktop. Version number: 24.0. URL link: https://www.adobe.com (2022), and Paint.NET. Version number: 5.0.13. URL link: https://www.getpaint.net (2024).

The daytime spatial distribution of LST reveals that the coldest temperatures are found in the northern outskirts of Tehran, followed by the northern areas. Conversely, the eastern, western, and southern surrounding regions experience the highest temperatures. LST values vary across seasons: in winter, temperatures are lowest in January (18 °C), February (24 °C), and December (21 °C). Spring temperatures peak at 35, 40, and 50 °C in March, April, and May, respectively. Summer records a consistent 56 °C throughout. Autumn sees temperatures of 50 °C in September, 42 °C in October, and 27 °C in November. The summer has the highest average temperature at 56 °C compared to other seasons. Spring and autumn have average LSTs of 41.66 °C and 39.66 °C, respectively, while winter has the lowest average at 21 °C. Generally, daily LST values peak during warm seasons (summer, spring, and autumn).

During the day, temperatures are generally higher in the suburbs compared to the city. A notable observation is the increase in LST in the suburbs compared to the city, with higher values during warm months than cold months.

The climatology of nighttime LST

The spatial analysis of the 19-year average of nighttime LST on a monthly basis for the metropolitan area of Tehran and its suburbs is shown in Fig. 3. In January, February, and December, temperatures in Tehran rise notably compared to the northern and eastern suburbs during the night. However, temperature values vary across the western, southeastern, southern, and southwestern suburbs but are largely similar to those in the city. This trend intensifies in subsequent months. By March, LST values in Tehran, particularly in the central district, show an increase from previous months. This pattern escalates further with urban and suburban temperatures peaking in April. As June approaches, Tehran experiences its highest summer temperatures with a significant rise in city temperatures. The peak occurs in July, notably in 22 districts with a focus on central districts. This upward trend continues through August before declining in September. By October, temperatures decrease compared to previous months, with conditions resembling those of March by November. A significant observation is the rise in surface temperature during warmer months compared to colder ones. The maximum nighttime LST is recorded from May to September, with a peak in July within urban districts (10–12, 14–17), encompassing parts of districts 6–9 and 13.

Spatial distribution of 19-year monthly average of nighttime LST in Tehran and its suburbs, highlighting the city’s 22 administrative districts. The data presented in this Figure were prepared using Earth data. Cite: AppEEARS Team. Application for Extracting and Exploring Analysis Ready Samples (AppEEARS). Version X.X. NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center (LP DAAC), USGS/Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center, Sioux Falls, South Dakota, USA. URL link: https://appeears.earthdatacloud.nasa.gov. Subsequently, the data were modified using Climate Data Operators (CDO). Version number: 2.0.4. URL link: https://code.mpimet.mpg.de (2022). The map was generated using the Grid Analysis and Display System (GrADS). Version number: 2.2.1.oga.1. URL link: http://cola.gmu.edu (2019). Both CDO and GrADS were utilized on Ubuntu Desktop Linux. Version number: 22.04 LTS. URL link: https://ubuntu.com (2022). Finally, Fig. 3 was enhanced using Adobe Photoshop Desktop. Version number: 24.0. URL link: https://www.adobe.com (2022), and Paint.NET. Version number: 5.0.13. URL link: https://www.getpaint.net (2024).

Furthermore, it is evident that along with the rise in temperature within the city, similar temperature increases are also observed in the southeastern suburbs. Hence, it can be inferred that the temperatures in the city and these suburbs are nearly equivalent. Nighttime temperatures have risen in the outskirts to the southeast, south, southwest, east, and west, as well as within the city, although this increase is more pronounced in the urban districts of Tehran. Typically, the coldest temperatures are noted in the northern peripheries of Tehran. Moving towards lower latitudes results in a gradual temperature increase within both the city and its outskirts, with peak temperatures seen first in the city and then extending to the outskirts situated in the southeast, south, and southwest.

An interesting observation is that nighttime temperatures in the city are higher than in the suburbs, with the highest temperatures observed in the urban districts of Tehran compared to the outskirts. The highest LST values at night are found in central city districts (10–12, 14–17, 20, and parts of districts 6–9 and 13), which vary across different seasons. In winter, LST values for January, February, and December in central city districts are 3 °C, 6 °C, and 4 °C, respectively. Spring temperatures peak at 9 °C in March, 14 °C in April, and 20 °C in May. Summer sees temperatures at 24 °C in June and 26 °C in July/August. Autumn temperatures reach 22 °C in September, 16 °C in October, and 10 °C in November. Consequently, summer has the highest average temperature at 25.33 °C compared to other seasons. Autumn follows with an average of 16 °C and spring with an average of 14.33 °C. Winter records the lowest values at an average of 4.33 °C. Generally, the nightly and monthly pattern of LST is almost similar. The highest temperatures are observed at night in the city, reaching their peak in the central districts during summer, while the lowest temperatures are seen in the outskirts.

Urban-suburban LST differences: a meridional perspective

To examine temperature variations between the city and its outskirts, the temperature difference from the central box temperature to temperatures along the south-north direction in Fig. 4 was calculated. Accordingly, temperatures in the central city box with the geographical latitude and longitude mentioned in Table 2 were compared seasonally and annually to temperatures at points ranging from latitude 35°51´ in the south to latitude 35°89´ in the north. These comparisons were then made between seasonal values and annual temperatures.

Monthly temperature differences between urban districts (Orange box) and suburbs for daytime and nighttime regarding the season. For comparison, the annual mean (thick black line) is added to all panels. The average 19-year LST values for winter (a-b), spring (c-d), summer (e-f), and autumn (g-h), taking into account the temperature difference (°C) between the central box and the southern and northern suburbs as depicted in Fig. 1c. The data presented in this Figure were prepared using Earth data. Cite: AppEEARS Team. Application for Extracting and Exploring Analysis Ready Samples (AppEEARS). Version X.X. NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center (LP DAAC), USGS/Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center, Sioux Falls, South Dakota, USA. URL link: https://appeears.earthdatacloud.nasa.gov. Subsequently, the data were modified using Climate Data Operators (CDO). Version number: 2.0.4. URL link: https://code.mpimet.mpg.de (2022). The profile was generated using the Grid Analysis and Display System (GrADS). Version number: 2.2.1.oga.1. URL link: http://cola.gmu.edu (2019). Both CDO and GrADS were utilized on Ubuntu Desktop Linux. Version number: 22.04 LTS. URL link: https://ubuntu.com (2022). Finally, Fig. 4 was enhanced using Adobe Photoshop Desktop. Version number: 24.0. URL link: https://www.adobe.com (2022), and Paint.NET. Version number: 5.0.13. URL link: https://www.getpaint.net (2024).

Daily temperature variations in Tehran and its suburbs vary across seasons, particularly at night. The temperature contrast between the central area and the southern suburbs at latitude 35°57´ is minimal and often below zero, although it surpasses zero in spring. Around latitude 35°60´, temperatures move around 4 °C but decrease as one moves toward the northern regions of Tehran, eventually exceeding 20 °C in the northern suburbs at latitudes above 35°83´.

During the day, the temperature difference between the city and its outskirts shows that the northern outskirts have a much higher temperature difference compared to both the city and the southern outskirts. The southern outskirts exhibit a lower temperature difference compared to the city, suggesting an increase in temperature on the southern outskirts relative to the northern outskirts. In summer, cities and suburbs are notably consistent with an annual pattern. In autumn and winter, only the southern suburbs demonstrate a high level of annual pattern consistency. However, in spring, there is a significant difference in annual pattern consistency between the northern and southern suburbs, indicating a decrease in temperature in the city compared to its suburbs. Additionally, the northern districts of the city experience lower temperatures than the southern districts (b, d, f, and h).

Analysis of nighttime charts in different seasons reveals that the temperature difference between the central area and the southern periphery, starting at latitude 35°50´, is about 6 °C, decreasing to under 4 °C near latitude 35°57´. In the city center, this variance approaches zero or less. These conditions persist up to Tehran’s northern urban districts. However, these values rise to over 20 °C at latitudes above 35°83´ in the northern outskirts, indicating a significantly higher temperature difference compared to annual temperatures in the northern suburbs relative to those in the southern periphery and central regions.

Annual temperature variations compared to seasonal temperatures indicate that the northern outskirts exhibit a greater temperature difference compared to the southern outskirts and central districts. Comparing nighttime temperature profiles shows that during summer, the temperature difference between the central region and the southern-northern outskirts increases, aligning closely with the annual trend. Essentially, at night, there is a more consistent pattern annually in terms of temperature contrast between the city and its outskirts, signifying a rise in city temperatures relative to its outskirts.

At night, the northern outskirts experience notably lower temperatures than their southern counterparts concerning the central region. Furthermore, seasonal temperature differences decrease during autumn and spring compared to yearly averages but intensify in winter, particularly in the northern outskirts (a, c, e, and g).

During the day, the temperature difference between the central area and the southern suburbs is negative in summer, autumn, and winter, indicating that the southern suburbs are warmer than the city. However, in the spring, the southern suburbs experience lower temperatures than the city. In contrast, the temperature difference with the northern suburbs is positive, indicating that the northern suburbs are cooler than the city. At night, the temperature difference between the central area and both northern and southern suburbs is positive in all seasons, reflecting higher temperatures in the city compared to the suburbs.

Urban-suburban LST differences: a zonal perspective

To examine temperature variations between the city and its outskirts, the temperature difference between the city central area (orange box) and the suburbs examined by using a west-east longitude profile in Fig. 5. Accordingly, temperatures in the central city box with the geographical latitude and longitude specified in Table 2 were compared seasonally and annually to temperatures at points ranging from a longitude of 51°15´ in the west to a longitude of 51°65´ in the east. These comparisons were then made between seasonal values and annual temperatures.

Monthly temperature differences between urban districts (orange box) and suburbs for daytime and nighttime regarding the season. For comparison, the annual mean (thick black line) is added to all panels. The average 19-year LST values for winter (a-b), spring (c-d), summer (e-f), and autumn (g-h), taking into account the temperature difference (°C) between the central box and the western and eastern suburbs as depicted in Fig. 1c. The data presented in this Figure were prepared using Earth data. Cite: AppEEARS Team. Application for Extracting and Exploring Analysis Ready Samples (AppEEARS). Version X.X. NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center (LP DAAC), USGS/Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center, Sioux Falls, South Dakota, USA. URL link: https://appeears.earthdatacloud.nasa.gov. Subsequently, the data were modified using Climate Data Operators (CDO). Version number: 2.0.4. URL link: https://code.mpimet.mpg.de (2022). The profile was generated using the Grid Analysis and Display System (GrADS). Version number: 2.2.1.oga.1. URL link: http://cola.gmu.edu (2019). Both CDO and GrADS were utilized on Ubuntu Desktop Linux. Version number: 22.04 LTS. URL link: https://ubuntu.com (2022). Finally, Fig. 5 was enhanced using Adobe Photoshop Desktop. Version number: 24.0. URL link: https://www.adobe.com (2022), and Paint.NET. Version number: 5.0.13. URL link: https://www.getpaint.net (2024).

Temperature differences between the city center and its outskirts are observed in a west-east direction. Throughout the daytime longitudinal profile, this temperature difference ranges from − 4 °C to 8 °C, approaching zero towards the western and central districts of Tehran and dropping below zero as one moves eastward. In the eastern outskirts, this difference exceeds 4 °C. Daytime temperature patterns differ significantly from nighttime conditions, highlighting a temperature difference between the central and western-eastern regions. Urban districts and the city center generally experience lower temperatures compared to the western and eastern suburbs, where temperatures peak. The central region indicates lower temperatures than the outskirts, reflecting the lowest annual temperatures across various seasons. During summer and autumn, suburban temperatures dip below the annual average, rendering them warmer than the city. Conversely, in spring and winter, suburban temperatures surpass the annual average, resulting in cooler eastern suburbs and warmer western suburbs compared to the city. Essentially, eastern suburbs are colder than the city while western suburbs are warmer, with a more pronounced temperature contrast between the center and east than with west.

During the night in the longitudinal profile, the temperature difference between the center and the western outskirts reaches approximately 6 °C at a geographical longitude of 51°15´. This difference gradually decreases from 51°20´ towards the central area of Tehran, eventually dropping below zero. As one moves away from urban districts and approaches the eastern outskirts, this temperature difference increases compared to the west, reaching over 8 °C at longitude 51°70´.

At night, a significant temperature contrast emerges between the central region and the eastern and western suburbs. These suburbs experience lower temperatures than the center, with a more pronounced drop in temperature in the east than in the west. Seasonal temperatures closely mirror annual temperatures, which is especially noticeable in summer and autumn.

In spring and winter, this temperature disparity among suburbs grows annually, with a more pronounced increase experienced in the eastern suburbs compared to their western counterparts. This trend intensifies during winter as differences between seasonal and annual temperatures expand within suburban areas during spring and winter.

Generally, the longitudinal and latitudinal profiles indicate that LST reaches a minimum over the central area of Tehran’s metropolitan region during the day and a maximum during the night. This suggests that the central districts of the city are cold during the day and warm at night when compared with the suburbs.

During the day, the temperature difference between the central area and the western suburbs becomes negative in summer and autumn, with the suburbs being warmer than the city. In spring, the western suburbs from longitude 51°15´ to 51°20´ are cooler than the city, while from longitude 51°26´ to the beginning of the central box, they are warmer than the city. Additionally, the eastern suburbs are also colder than the city.

In winter, the eastern suburbs remain colder than the city, while temperatures in the western suburbs align with those of the city, showing a noticeable drop in January. The temperature difference in the eastern suburbs is negative during summer and remains negative throughout autumn, except for November. In winter and spring, this difference becomes positive, indicating that temperatures in the eastern suburbs are lower than those in the city. At night, there is a positive difference, meaning that temperatures in the central area increase compared to those in the suburbs.

Interannual and intra-annual variability and trends in day and nighttime LST

The results of the annual temperature trend change in Fig. 6 show that the average maximum temperature was 29.15 °C in 2020 and increased to 31.69 °C in 2021, representing the lowest and highest values observed during these years, respectively. The annual average minimum temperature has fluctuated from 8.30 °C in 2003 to 10.32 °C in 2021. The minimum temperature trend in Tehran has been on the rise for over 19 years, although the daytime temperature trend in Tehran has also increased, albeit to a lesser extent than nighttime temperatures (a). The standard score during the day indicates that the years 2006, 2010, 2013 to 2018, as well as 2021, have positive values. At night, the years 2010 and 2013 to 2021 also show positive values (b).

Analysis of LST in the Tehran metropolitan area, depicting (a) interannual variability, (b) standardized anomaly, (c) monthly mean LST (day and night), and (d) Sen’s trend slope. The data presented in this Figure were prepared using Earth data. Cite: AppEEARS Team. Application for Extracting and Exploring Analysis Ready Samples (AppEEARS). Version X.X. NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center (LP DAAC), USGS/Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center, Sioux Falls, South Dakota, USA. URL link: https://appeears.earthdatacloud.nasa.gov. Subsequently, the data were modified using Climate Data Operators (CDO). Version number: 2.0.4. URL link: https://code.mpimet.mpg.de (2022). The data were analyzed in Microsoft Excel. Version number: 2021, from Microsoft Corporation. URL link: https://office.microsoft.com (2021). Additionally, R. Version number: 4.3.1 was used for analysis; URL link: https://www.r-project.org (2023), along with R Studio. Version number: 2023.06.1. URL link: https://posit.co (2023). Finally, the chart was generated using the Grid Analysis and Display System (GrADS). Version number: 2.2.1.oga.1. URL link: http://cola.gmu.edu (2019). Both CDO and GrADS were utilized on Ubuntu Desktop Linux. Version number: 22.04 LTS. URL link: https://ubuntu.com (2022).

The average maximum temperature in Tehran ranges from 11.21 °C in January to 46.89 °C in July, with a similar variation seen in the average minimum temperature based on MODIS LST data—from 3.49 °C in January to 21.37 °C in July—making January the coldest and July the hottest month in Tehran (c).

To identify monthly temperature trend changes per decade in Tehran, the average slope of the temperature trend for minimum and maximum temperatures was calculated. In this context, the steepest slope of the trend for average daily and nightly temperatures is observed in January at 1.90 °C and in May at 1.64 °C per decade, respectively. March and October record the lowest values for maximum (-1.50 °C) and minimum (-0.30 °C) average temperatures. The average range of maximum and minimum temperatures in all months, except for October, exhibits an increasing trend. Analysis of changes in daily and nightly temperature trends reveals significant variations. The average daily temperature across Tehran’s entire geographical area has risen by 0.28 °C per decade, while the average nightly temperature has increased by 0.74 °C per decade. The trend slope for the average nighttime temperature in Tehran’s geographical area displays noticeable fluctuations across different months (d).

The LST difference between the City center and suburbs

In this section, as illustrated in Fig. 7, the central area of Tehran, with a geographical latitude ranging from 35°66´ to 35°71´ and a geographical longitude ranging from 51°35´ to 51°48´, was compared with three suburbs in the east, west, and south that exhibited the lowest temperatures among all suburbs. Despite the northern suburbs having the lowest temperatures compared to other suburbs, it was excluded due to the presence of mountainous terrain and potential calculation errors (Fig. 2c).

The temperature difference between Tehran and its suburbs over a 19-year period (2003–2021) by using the dominant defined in Fig. 1c. and Table 3. Comparison of the SD of day and night temperatures (a-b) and the difference in nighttime UHI effect across different months (c), as well as winter (d), spring (e), summer (f), autumn (g), and annually (h) in Tehran’s metropolis, including its eastern, western, and southern suburbs as depicted in Fig. 1c. and come in Table 3. The data presented in this Figure were prepared using Earth data. Cite: AppEEARS Team. Application for Extracting and Exploring Analysis Ready Samples (AppEEARS). Version X.X. NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center (LP DAAC), USGS/Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center, Sioux Falls, South Dakota, USA. URL link: https://appeears.earthdatacloud.nasa.gov. Subsequently, the data were modified using Climate Data Operators (CDO). Version number: 2.0.4. URL link: https://code.mpimet.mpg.de (2022), and the Grid Analysis and Display System (GrADS). Version number: 2.2.1.oga.1. URL link: http://cola.gmu.edu (2019). Both CDO and GrADS were utilized on Ubuntu Desktop Linux. Version number: 22.04 LTS. URL link: https://ubuntu.com (2022). The charts were generated using Microsoft Excel. Version number: 2021. from Microsoft Corporation. URL link: https://office.microsoft.com (2021), as well as Origin 2024 from OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA. Version number: Origin 2024 (10.1). URL link: https://www.originlab.com (2023). Finally, Fig. 7 was enhanced using Paint.NET. Version number: 5.0.13. URL link: https://www.getpaint.net (2024).

The SD is a measure of data dispersion from the average. The figure below illustrates the range between the minimum (0.58 °C) and maximum (2.34 °C ) daily standard deviations in October and January, which is 1.75 °C, with an average monthly SD of 1.22 °C. This suggests higher data dispersion during the day. Conversely, in September (0.34 °C) and November (0.95 °C), the difference in SD at night is 0.61, with a monthly average of 0.64 °C, indicating lower dispersion closer to zero and data clustering around the mean.

Comparing the standard deviations during the day and at night shows that nighttime measurements more accurately depict UHI effects in Tehran’s metropolitan area compared to daytime readings. The subtle differences in SD values emphasize the significance of studying UHI effects during nighttime. Therefore, considering the occurrence of the UHI at night, monthly, seasonal, and annual charts will be examined to compare the nighttime UHI difference between the urban area of Tehran and its surrounding suburbs.

The monthly temperature difference in Tehran compared to its surrounding suburbs is very small, ranging from 5.73 to 6.49 °C, with a variation of 0.76 °C. The highest values occur in September, June, and August, while the lowest values happen in November, December, and February. In winter, the temperature difference between the city and the suburbs ranges from 4.68 to 7.06 °C, with the smallest difference in 2020 and the largest in 2008. Spring 2020 has the smallest difference (5.11 °C) compared to 2008, with the largest difference (6.78 °C). In summer and autumn, 2020 shows the smallest differences between city and suburbs at 4.92 and 5.67 °C, respectively. For summer and autumn, 2006 at 7.08 °C and 2016 at 6.93 °C show the largest differences. Annually, 2020 has the smallest difference (5.09 °C), while 2008 has the highest difference (6.70 °C). Therefore, based on the investigations conducted on the day and night LST outputs, and considering that nighttime surface temperatures more prominently reflect temperatures over Tehran, as indicated in Sects. 3–6, a more pronounced UHI effect is observed in Tehran at night. Hence, subsequent analyses will focus solely on nighttime conditions.

The climatology of the nighttime SUHI

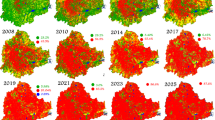

In Fig. 8, the expansion of the UHI in Tehran and its suburbs is depicted monthly and annually. The UHI is more pronounced over the 22 urban districts of Tehran than in the suburbs during both cold and warm months. While high values are observed in the southeast, south, and southwest suburbs, Tehran and other suburbs exhibit higher heat island values compared to the northern suburbs. The primary heat island cores are situated in central Tehran (10-11-12 and 14 districts), where insufficient vegetation cover, urban surface conversion, improper urban design, and construction contribute to temperature rises. The westward and southwestward expansion of Tehran’s heat island may be attributed to reduced vegetation cover.

Spatial distribution of 19-year monthly and annual average of SUHI in Tehran and its suburbs, as depicted in Fig. 1b. The city’s 22 administrative districts are highlighted. The data used in this study were prepared using Earth data. Cite: AppEEARS Team. Application for Extracting and Exploring Analysis Ready Samples (AppEEARS). Version X.X. NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center (LP DAAC), USGS/Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center, Sioux Falls, South Dakota, USA. URL link: https://appeears.earthdatacloud.nasa.gov. Subsequently, the data were modified using Climate Data Operators (CDO). Version number: 2.0.4. URL link: https://code.mpimet.mpg.de (2022). The maps were generated with the Grid Analysis and Display System (GrADS). Version number: 2.2.1.oga.1. URL link: http://cola.gmu.edu (2019). Both CDO and GrADS were utilized on Ubuntu Desktop Linux. Version number: 22.04 LTS. URL link: https://ubuntu.com (2022). Finally, Fig. 8 was enhanced using Adobe Photoshop Desktop. Version number: 24.0. URL link: https://www.adobe.com (2022), and Paint.NET. Version number: 5.0.13. URL link: https://www.getpaint.net (2024).

Paying attention to Tehran’s urban geometry is crucial for identifying the UHI. The urban canyon, a key factor, traps longwave radiation and intensifies UHI in Tehran’s urban districts. The ratio of building height (h) to distance between them (w) impacts the absorption and reflection of shortwave radiation from surfaces. Compact spaces with high W/H ratios are notably affected by longwave radiation due to their enclosed nature, contributing to the rising trend of the urban heat island. Much of central Tehran is encircled by compact buildings. The use of dark materials on urban surfaces and within urban canyons formed by buildings of varying heights results in the absorption and retention of solar energy, consequently elevating the city’s temperature. In central Tehran, where buildings are tall compared to street width, the UHI effect is more pronounced. This occurs because reduced solar energy balance due to narrow streets results in higher urban temperatures. Greater irregularities in urban layout further amplify the UHI effect. Therefore, as the disparity between street height and width grows, so does the intensity of the UHI.

The climatology of the hotspots

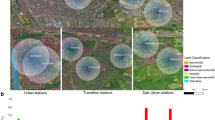

As depicted in Fig. 9, the spatial distribution of monthly and annual hotspots is shown. Central cores of hotspots form in central districts (10-11-12 and 14). Population density can have dual effects on heat production: a direct effect through higher population leading to increased metabolism and an indirect effect through the number of buildings, vehicles, and factories that increase with population growth.

The average monthly and annual frequencies of nighttime hotspots in Tehran and its suburbs, including the city’s 22 districts. The maps display the 19-year long-term mean abundance of LST exceeding specified monthly thresholds (see Table 4), calculated from daily data. The data used in this study were prepared using Earth data. Cite: AppEEARS Team. Application for Extracting and Exploring Analysis Ready Samples (AppEEARS). Version X.X. NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center (LP DAAC), USGS/Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center, Sioux Falls, South Dakota, USA. URL link: https://appeears.earthdatacloud.nasa.gov. Subsequently, the data were modified using Climate Data Operators (CDO). Version number: 2.0.4. URL link: https://code.mpimet.mpg.de (2022). The maps were generated with the Grid Analysis and Display System (GrADS). Version number: 2.2.1.oga.1. URL link: http://cola.gmu.edu (2019). Both CDO and GrADS were utilized on Ubuntu Desktop Linux. Version number: 22.04 LTS. URL link: https://ubuntu.com (2022). Finally, Fig. 9 was enhanced using Adobe Photoshop Desktop. Version number: 24.0. URL link: https://www.adobe.com (2022), and Paint.NET. Version number: 5.0.13. URL link: https://www.getpaint.net (2024).

Regions 10, 11, and 12 rank 11th, 13th, and 19th in terms of population density among regions, respectively; however, population density alongside other climatic factors remains significant. Urban structure is also crucial. A city valley, especially the height of buildings concerning street width, provides more potential for trapping radiation within the urban valley. This phenomenon occurs when sunlight is reflected by a surface and encounters other surfaces in the city, partly absorbed and partly reflected. In fact, urban surfaces absorb more radiation than solar radiation compared to what is expected from surface reflection. The trapping of long-wave radiation is attributed to the sky view factor. Tall buildings predominantly obstruct a major portion of the sky, resulting in limited long-wave radiation reaching the ground in city valleys. Dense buildings have significantly encroached upon central districts of Tehran (10-11-12 and 14), covering over half of the city’s districts. These central districts serve as vital hubs for production, residence, commerce, distribution, and transportation. Furthermore, the southeast outskirts exhibit hot spots during warm months, with peak levels in July and lowest levels in January.

Relation between urban and suburban LST and the elevation

The annual nighttime LST chart analysis with the height of Tehran in Fig. 10 reveals a slight temperature decrease in the southern outskirts at a geographical latitude of 35°50´, with very low altitude values near 1000 m. Moving towards the southern areas at a latitude of 35°57´, this temperature increase persists towards the city center. Progressing from latitude 35°57´ towards northern latitudes increases altitude values, exceeding 2000 m at latitude 35°83´ in the city’s north. Approaching the northern outskirts further decreases the temperature and raises altitude values. Consequently, an ascending slope for altitude is observed from the southern outskirts to the northern outskirts, reaching its minimum in the city center and southern outskirts.

Average nighttime LST of Tehran metropolis and its suburbs at different elevations over 19 years. Comparison of UHI in 22 urban districts and suburbs from south to north and west to east. The geographical coordinates of the central box of Tehran are provided in Table 2. The LST data presented in this Figure were prepared using Earth data. Cite: AppEEARS Team. Application for Extracting and Exploring Analysis Ready Samples (AppEEARS). Version X.X. NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center (LP DAAC), USGS/Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center, Sioux Falls, South Dakota, USA. URL link: https://appeears.earthdatacloud.nasa.gov. Additionally, the elevation data were obtained from NOAA. URL link: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov. Subsequently, the data were modified using Climate Data Operators (CDO). Version number: 2.0.4. URL link: https://code.mpimet.mpg.de (2022). The maps were generated using the Grid Analysis and Display System (GrADS). Version number: 2.2.1.oga.1. URL link: http://cola.gmu.edu (2019). Both CDO and GrADS were utilized on Ubuntu Desktop Linux. Version number: 22.04 LTS. URL link: https://ubuntu.com (2022). Finally, Fig. 10 was enhanced using Adobe Photoshop Desktop. Version number: 24.0. URL link: https://www.adobe.com (2022), and Paint.NET. Version number: 5.0.13. URL link: https://www.getpaint.net (2024).

Additionally, the longitudinal profile of the annual LST shows a decrease with increasing altitude in the Tehran metropolis. At a longitude of 51°15´, temperatures reach their minimum as elevations in this region exceed 1000 m. Approaching the city, temperatures notably rise, especially in central districts. In the west-east chart, the city center’s elevation is the same to the west and decreases compared to the east. Exiting the city towards a longitude of 51°64´ in the eastern outskirts, temperatures decrease due to higher altitudes, with an ascending slope from west to east in terms of elevation.

The relation between urban and suburban LST and NDVI

The annual nighttime LST chart analysis with NDVI for Tehran’s metropolitan area in Fig. 11 indicates a decreasing temperature trend in the southern outskirts at a latitude of 35°50´ compared to the city. Areas at this latitude exhibit high NDVI values, nearing 0.50. Moving towards the southern regions at a latitude of 35°57´, temperatures rise towards the city center, where NDVI values drop significantly due to natural coverage giving way to human-made surfaces (exceeding 0.1), particularly in central urban districts. At a latitude of 35°83´, temperature decline coincides with increased vegetation cover (around 0.2). Progressing towards the northern outskirts lowers temperatures and diminishes NDVI values, with central districts showing lower NDVI values than the outskirts.

Average nighttime LST of Tehran metropolis and its suburbs with NDVI over 19 years. Comparison of UHI in 22 urban districts and suburbs from south to north and west to east. The geographical coordinates of the central box of Tehran are provided in Table 2. The data presented in this Figure were prepared using Earth data. Cite: AppEEARS Team. Application for Extracting and Exploring Analysis Ready Samples (AppEEARS). Version X.X. NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center (LP DAAC), USGS/Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center, Sioux Falls, South Dakota, USA. URL link: https://appeears.earthdatacloud.nasa.gov. Subsequently, the data were modified using Climate Data Operators (CDO). Version number: 2.0.4. URL link: https://code.mpimet.mpg.de (2022). The maps were generated using the Grid Analysis and Display System (GrADS). Version number: 2.2.1.oga.1. URL link: http://cola.gmu.edu (2019). Both CDO and GrADS were utilized on Ubuntu Desktop Linux. Version number: 22.04 LTS. URL link: https://ubuntu.com (2022). Finally, Fig. 11 was enhanced using Adobe Photoshop Desktop. Version number: 24.0. URL link: https://www.adobe.com (2022), and Paint.NET. Version number: 5.0.13. URL link: https://www.getpaint.net (2024).

Furthermore, the longitudinal profile of LST with NDVI in Tehran shows that at a longitude of 51°15´, the temperature reaches its minimum, while NDVI values in this region are high (above 0.3). As one approaches the city, it is observed that the temperature, especially in central districts, increases and vegetation cover across the west-east longitudinal profile decreases. Upon leaving the city at a longitude of 51°64´ in the eastern suburbs, temperatures decrease. Vegetation cover in Tehran is very minimal compared to that in the western and eastern suburbs.

Discussion

Evaluating the effects of urban expansion on LST: a focus on nighttime SUHI

The LST parameter plays a crucial role in understanding climate change, land warming, and urban land use80. In Tehran and its suburbs, the highest LST values are predominantly found in built-up areas. This trend indicates that LST values are on the rise in urban regions, particularly within central districts and the western, southwestern, southern, and southeastern suburbs. Notably, the average LST across all land uses is increasing, with significant contributions from built-up zones such as heavy industry and compact buildings. This escalation is largely attributed to rapid urbanization occurring both within Tehran and its surrounding areas81,82.

As population movement intensifies from the outskirts into the urban centers of Tehran, urbanization accelerates further. However, this growth has not been without challenges; inappropriate construction practices, unplanned urban development, and neglect of the city’s existing texture have collectively led to a marked increase in LST—especially during summer months—from 1984 to 202017. Consequently, both daily and nightly LST values peak during hot months like summer and remain elevated in other seasons such as autumn and spring when compared to winter40.

In terms of seasonal variations, January emerges as the coldest month, while July stands out as the hottest month for Tehran—both during the day and night. Furthermore, there is a discernible upward trend in average daily and nightly temperatures across Tehran’s geographical expanse on both monthly and yearly scales; this increase is particularly pronounced at night.

The rising temperature trend in the Tehran metropolitan area is compounded by escalating air pollutants, fossil fuel consumption, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and an increase in heatwave occurrences. The temperature differential between the city center and its suburbs illustrates this phenomenon clearly: a day-night chart (Fig. 1a) reveals an increasing temperature gradient from central regions towards northern and eastern suburbs—largely due to highlands and snow-covered areas—while showing a decreasing gradient towards western and southern outskirts where temperatures are warmer.

Tehran’s climate has undergone significant changes driven by extensive urbanization coupled with population growth, primarily in the eastern and southern districts. Increased traffic congestion in northern and eastern parts of the city further exacerbates these issues alongside higher fossil fuel consumption across construction, transportation, and industrial sectors. The formation of UHI has also been a critical factor contributing to these climatic shifts.

Interestingly, there exists a negative temperature variance between urban centers and their outskirts during daytime hours; however, this reverses at night, where positive variances indicate higher temperatures within urban areas. This phenomenon highlights how nighttime LST significantly increases within urban areas—a key aspect for studying UHI effects specific to Tehran40.

In urban climatology literature, particular attention is given to nighttime UHI formation83. One major contributor to this phenomenon is urban texture itself; studies show that over 50 cities worldwide exhibit strong correlations between nighttime UHI effects and their respective urban textures84. In Tehran’s metropolitan area specifically, UHI impacts are more pronounced at night due to substantial thermal inertia present in materials used for construction. The heat retained by these materials, combined with their limited cooling capacity, leads to elevated nighttime temperatures85.

Nighttime land surface cooling is intricately linked to net longwave radiation loss. As urban valleys expand, a notable decrease in the amount of longwave radiation emitted from the land surface occurs. This reduction is primarily due to the presence of walls that replace open skies, thereby obstructing some of the emitted radiation86.

Research indicates that the most intense UHI effects are observed in districts with medium-density buildings, while tall, open structures tend to exhibit the lowest intensity of UHI87. This suggests that urban valleys play a more significant role in exacerbating nighttime UHI effects88.

Furthermore, nighttime lighting resulting from human activities also contributes to the formation of nighttime SUHI89. As a result, cities like Tehran and its southeastern, southern, southwestern, and western outskirts experience some of the highest levels of UHI during nighttime hours90. This interplay between urban structure and human activity underscores the complex dynamics influencing urban heat patterns.

Key factors influencing SUHI in Tehran

Nighttime temperature differences

Therefore, considering the factors mentioned, it is expected that nighttime UHI values inside the city of Tehran will increase more rapidly compared to the surrounding areas. Additionally, the UHI in central city districts will be higher than in suburban areas31. During the night, the temperature difference between the city and the village increases significantly compared to the daytime due to variations in land use. Urban districts feature impermeable surfaces like buildings, asphalt, and streets that enhance heat retention. Conversely, rural regions consist of open spaces with permeable surfaces, such as vegetation and soil, allowing for rapid heat dissipation and lower temperatures. Consequently, the most significant temperature difference between urban and rural areas, or the highest UHII, typically arises during calm nights with clear skies three to five hours after sunset in the late evening. The average UHII at night varies among different cities29,30. In arid and semi-arid regions, temperatures in urban centers can increase more compared to their surrounding areas91,92. This difference may be attributed to various factors such as climate, topography, and urban patterns93. Furthermore, UHII not only varies across different seasons but also escalates with the size of the urban area94.

Soil moisture reaches its minimum in the summer, which reduces the temperature difference between the city and its suburbs. In contrast, the concentration of urban pollutants peaks during the cold season (autumn and winter) compared to other times of the year95. As pollutant concentrations increase in the boundary layer within cities, the greenhouse effect caused by high pollutant levels leads to higher temperatures in urban districts. Conversely, in the suburbs, energy loss from longwave radiation during extended winter nights (and generally throughout the cold season) results in significantly lower temperatures. This creates a greater temperature difference between the city and its suburbs during this time of year.

Impacts and implications of COVID-19 in Tehran’s SUHI and urban planning

One notable point regarding the temperature difference between Tehran and its suburbs is that in 2020, Tehran recorded significantly lower temperatures across all seasons. One reason for this may be the COVID-19 pandemic, which contributed to a noticeable drop in temperatures that year42.

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly contributed to urban cooling in Tehran in 2020 due to a nationwide lockdown that reduced both human and industrial activities. A key factor in diminishing the intensity and spread of the UHI effect was the decrease in traffic within the city. This approach contributes to reducing air pollutants and GHG emissions within the city, leading to a more balanced urban temperature. This experience highlights that UHI can be managed relatively swiftly, leading to immediate climatic benefits42.

Moving forward, transitioning to environmental sustainability in the post-pandemic era is crucial for enhancing the climate of the Tehran metropolitan area. Achieving sustainable development—by minimizing environmental harm and fostering socio-technological resilience—requires a comprehensive strategy aimed at instilling sustainable practices among citizens and city officials alike, ensuring a sustainable future for everyone. While air pollution levels dropped during the COVID-19 outbreak, it is essential to maintain this momentum in the post-pandemic period to foster a greener and more sustainable urban environment96.

Geographical considerations in Tehran’s SUHI

Elevation and wind direction