Abstract

Automatic emotion detection has become crucial in various domains, such as healthcare, neuroscience, smart home technologies, and human-computer interaction (HCI). Speech Emotion Recognition (SER) has attracted considerable attention because of its potential to improve conversational robotics and human-computer interaction (HCI) systems. Despite its promise, SER research faces challenges such as data scarcity, the subjective nature of emotions, and complex feature extraction methods. In this paper, we seek to investigate whether a lightweight deep neural ensemble model (CNN and CNN_Bi-LSTM) using well-known hand-crafted features such as ZCR, RMSE, Chroma STFT, and MFCC would outperform models that use automatic feature extraction techniques (e.g., spectrogram-based methods) on benchmarked datasets. The focus of this paper is on the effectiveness of careful fine-tuning of the neural models with learning rate (LR) schedulers and applying regularization techniques. Our proposed ensemble model is validated using five publicly available datasets: RAVDESS, TESS, SAVEE, CREMA-D, and EmoDB. Accuracy, AUC-ROC, AUC-PRC, and F1-score metrics were used for performance testing, and the LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) technique was used for interpreting the results of our proposed ensemble model. Results indicate that our ensemble model consistently outperforms individual models, as well as several compared models which include spectrogram-based models for the above datasets in terms of the evaluation metrics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Emotions play a crucial role in human social interactions, aiding communication through different channels including facial expressions, speech patterns, and body language1. The significance of automatic emotion detection through computer vision has garnered considerable attention across various fields, such as healthcare2, neuroscience, smart home technologies, and cancer treatment3,4. This growing interest underscores the importance of emotion recognition as an expanding field, owing to its profound impact on human life. SER is increasingly being adopted in human-computer interaction (HCI), where it contributes to improving the intelligence of conversational robots and HCI systems5,6. By interpreting emotions expressed through speech, SER enhances service quality and promotes more natural and personalized interaction experiences7.

In recent years, various algorithms have been proposed for extracting features from audio signals to address challenges such as noise and signal complexities. Among the commonly used algorithms are Zero Crossing Rate (ZCR), Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCC), and Root Mean Square Energy (RMSE)8,9,10. Moreover, advanced neural models like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN)11, Bi- Directional Long time Short Time Memory (Bi-LSTM)12, and CNN + LSTM (CNN-LSTM)13 have proven effective14 for audio signal processing. These models excel in automatically capturing temporal dependencies and extracting meaningful features from audio signals. However, despite its promise, SER research encounters challenges from the scarcity of high-quality data, the subjective nature of emotions, and the complexity of feature extraction methods. While feature extraction methods like spectral and qualitative features offer relatively high accuracy, their extraction requires specialized expertise15.

In this work, we seek to investigate whether a lightweight deep neural ensemble model using well-known hand-crafted features such as ZCR, RMSE, Chroma Short-Time Fourier Transform (Chroma STFT)16, and MFCC17 would outperform models that use automatic feature extraction techniques (e.g., spectrogram-based methods) on benchmarked datasets. Instead of relying on complex and resource-intensive architectures, this study focuses on the effectiveness of careful fine-tuning of deep neural networks (DNN) in achieving improved performance metrics. Fine-tuning methods including regularization techniques and LR schedulers were applied to optimize our proposed ensemble model. Five publicly available datasets were used for experiments: the Ryerson Audiovisual Database of Emotional Speech and Music (RAVDESS)18, the Toronto Emotional Speech Set (TESS)19, the Surrey Audio-Visual Expressed Emotion (SAVEE)20, the Crowdsourced Emotional Multimodal Actors (CREMA-D)21, and the Berlin Database of Emotional Speech (EmoDB)22. These datasets vary in terms of sample sizes and also exhibit imbalances in data distribution. Data augmentation was used as a part of the preprocessing step. Accuracy, AUC-ROC, AUC-PRC, and F1-score were used for performance testing, and the LIME23 technique was used for interpreting the results of our proposed model. This work has shown that our proposed ensemble model surpasses the compared models, including spectrogram-based models, in terms of accuracy across the datasets mentioned.

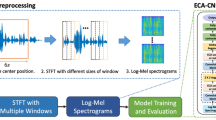

Figure 1 offers a schematic overview of our approach. In Step 1, we begin by preparing the data and applying enhancement through augmentation techniques. In Step 2, features are extracted from audio signals, followed by the normalization of data and the handling of any missing feature values. Step 3 involves training neural network models using these features and obtaining final predictions from our ensemble model. \(P_{1}(t)\) and \(P_{2}(t)\) denote the output probabilities of the 1D Convolutional Neural Network (1DCNN) and CNN_Bi-LSTM models, respectively. The ensemble output probability \(P(t)\) is computed by averaging the corresponding probabilities at each time step \(t\) using an averaging unit.

This paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 provides a comprehensive review of the literature related to SER. Section 3 discusses handcrafted features, including RMSE, ZCR, Chroma STFT, and MFCC. Section 4 gives implementation details that include datasets used in the experiments, data augmentation and feature extraction pipeline, and model configuration and optimization methods. Section 5 details the experimental findings and compares them with existing studies. Section 6 thoroughly discusses the outcomes of the results. Finally, Sect. 7 wraps up the study by discussing its significance and outlining potential directions for future work.

Review of related works

In this section, we provide a detailed discussion of research related to SER starting with a general overview, followed by traditional machine learning methods in SER since early work focused on hand-crafted features and curating datasets. In addition, we discuss recent research on the application of DNNs in SER and conclude with a detailed discussion of papers related to our proposed study.

General Overview Early efforts in SER focused on representing emotions through various feature sets, which encode emotional content into numerical values and their variations. Key feature sets in this area include Interspeech24,25, GeMAPS (or eGeMAPS)26, and openSMILE27. These sets encompass a range of effective speech-based features, particularly GeMAPS. However, due to the inherent complexity of SER, researchers have explored alternative approaches, notably deep learning (DL) techniques. Among these, CNNs have been used to analyze speech by processing time and frequency information, demonstrating promising results28,29. Building on this, transfer learning has been applied in SER, with pre-trained Residual Networks (ResNets) on large emotional speech datasets being adapted for other datasets. Additionally, advancements in deep learning architectures, such as attention mechanisms and sophisticated LSTM models, have significantly contributed to the field. Furthermore, refined feature extraction methods, including phase information30 and mel-frequency magnitude coefficients (MFMC)31, underscore the ongoing progress and innovation in SER research.

Machine Learning in SER

Support Vector Machine (SVM)32,33, Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM), k-nearest Neighbor (KNN)34 were the most commonly used classifiers for SER. In35, researchers introduced a statistical feature selection method that considers the average of each feature within the feature set. Evaluating emotion recognition performance across multiple datasets, including EmoDB, Extended Natural Task Enacted in Realistic Conditions with Involuntary, Spontaneous, and Induced Emotional Expressions (eNTERFACE05)36, Emotional Voices of Parisiennes (EMOVO)37, and SAVEE, the study employed SVM, Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), and KNN classifiers. The SVM model consistently demonstrated superior classification accuracy across all datasets, except the eNTERFACE05 dataset. Zehra et al.24 introduced an ensemble-based framework for cross-corpus multilingual speech emotion recognition. This framework employs a majority voting approach, resulting in nearly a 13% improvement in classification accuracy. In their work, Noroozi et al.38 presented a novel method for vocal-based emotion identification using random forests. They utilized a variety of features from speech signals and applied this method to the SAVEE dataset, employing leave-one-out cross-validation. In39, researchers achieved a classification accuracy of 93.63% with decision trees and 73% with logistic regression classifiers on a Malayalam emotional speech database with 2800 speech audios from ten speakers for recognizing eight emotions from speech based on vocal tract characteristics.

DNN in SER

Recent research has focused on improving the generalization capabilities of DNNs across various datasets. This has been achieved by using RNNs40 and LSTM networks41, which are adept at learning temporal information crucial for emotion recognition by using contextual dependencies. Nevertheless, RNNs often face challenges related to gradient descent42. Recent advancements in automatic feature selection for SER tasks have been driven by improvements in CNNs43 and DNNs44,45. Seo et al.46 introduced a method that involves pre-training log-mel spectrograms from a source dataset using a Visual Attention Convolutional Neural Network, followed by fine-tuning the target dataset with a Bag of Visual Words approach. Experimental results demonstrate significant performance improvements on benchmark datasets, including RAVDESS, EmoDB, and SAVEE, with accuracy boosts of up to 15.12% compared with existing approaches. Using parallel-based networks, Bautista et al.47 worked with eight different emotions on the RAVDESS dataset. They applied various augmentation techniques and achieved an accuracy of 89.33% with a Parallel CNN-Transformer and 85.67% with a Parallel CNN-Bi-LSTM-Attention Network. Sera et al.48 introduced Bi-LSTM Transformer and 2D CNN models, applying dimensionality reduction algorithms with 10-fold cross-validation on the EmoDB and RAVDESS databases. This approach achieved accuracy rates of 95.65% and 80.19%, respectively. Pan et al.49 proposed an architecture that combines CNN, LSTM, and DNN using MFCC features as input to local feature learning blocks (LFLBs), followed by LSTM layers to effectively capture temporal dynamics in speech signals. Experimental results across RAVDESS, EmoDB, and IEMOCAP demonstrated classification rates of 95.52%, 95.84%, and 96.21%, respectively. In50, spectrogram features extracted from the RAVDESS dataset were input into a DNN with a gated residual network, resulting in an accuracy of 65.97% for emotion recognition on the test data. Issa et al.51 extracted spectral contrast, MFCC, and Mel-Spectrogram features, which were fused and used as input for a DNN model, achieving an accuracy of 71.61% with the RAVDESS dataset. However, their CNN model struggled to effectively capture the spatial features and sequences crucial for speech signals. Zhao et al.29 used CNNs to extract features from raw speech signals and employed RNN models to capture long-term dependency features. Pawar et al.52 trained a CNN model using MFCC features and achieved an accuracy of 93.8% on the EmoDB dataset. Bhangale53 trained a 1D CNN model using a range of acoustic features and achieved accuracies of 93.31% on the EmoDB dataset and 94.18% on the RAVDESS dataset. Badshah et al.54 employed a double CNN model with input generated from spectrograms using the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). Chen et al.55 introduced a comprehensive audio transformer for speech analysis, incorporating a speech-denoising approach to learn general speech representations from the unannotated SUPERB56 dataset.

Discussion on papers related to our proposed model

In this section, we provide a brief overview of research that is directly relevant to our study. Akinpelu et al.57 developed an efficient model by integrating Random Forest and MLP classifiers within the VGGNet framework resulting in accuracies with the following datasets: TESS (100%), EmoDB (96%), and RAVDESS (86.25%) with the MFCC feature. Ottoni et al.58 trained CNN and LSTM models resulting in good accuracies with the following datasets: RAVDESS (97.01%), TESS (100%), CREMA-D (83.28%), and SAVEE (90.62%) with the MFCC, Chroma, ZCR, and RMSE features. Jothimani et al.59 utilized a combination of MFCC, ZCR, and RMSE features, along with data augmentation techniques, to train a CNN model. The model achieved accuracies of 92.60% on RAVDESS, 99.60% on TESS, 89.90% on CREMA-D, and 84.90% on SAVEE. Jiang et al.60 developed a hybrid model that integrates convolutional and recurrent neural network components to combine spectral features with frame-level learning, applied to the EmoDB, SAVEE, CASIA61, and ABC62 datasets. LSTM handles temporal features, while a CNN processes static, delta and delta-delta log Mel-spectrogram features. The model integrates and normalizes these features. Mustaqeem et al.63 introduced a method that employs radial basis function networks to measure similarity by selecting important sequence segments, applied to the IEMOCAP, EmoDB, and RAVDESS datasets. The selected segments are converted into spectrograms using the STFT algorithm, processed by a CNN model for feature extraction, normalized, and then fed into a deep Bi-LSTM model for temporal information learning. In64, researchers proposed a self-labeling method that segments and labels frames with corresponding emotional tags using a time-frequency deep neural network. They enhanced performance with a feature transfer learning model, demonstrating effectiveness on datasets like EmoDB and SAVEE. Guizzo et al.65 proposed RH-emo, a semi-supervised framework for extracting quaternion embeddings from real-valued spectrograms. This method uses a hybrid autoencoder network, which integrates a real-valued encoder, an emotion classification component, and a quaternion-valued decoder. When tested on IEMOCAP, RAVDESS, EmoDB, and TESS datasets, RH-emo demonstrated improved test accuracy and reduced resource demands compared to traditional CNN architectures. In66, the researchers introduced a combination of dilated CNN and residual blocks along with Bi-LSTM including attention mechanisms to improve feature extraction and model performance on the IEMOCAP and EmoDB datasets. Kwon et al.67 proposed a one-dimensional dilated CNN that incorporates residual blocks and sequence learning modules to extract and learn spatial features which resulted in accuracies of 73% (IEMOCAP) and 90%(EmoDB). In their paper, Krishnan et al.68 explore recognizing seven emotional states from speech signals using entropy features based on randomness measures. They decompose speech into Intrinsic Mode Functions and compute entropy measures from different frequency bands. The resulting feature vectors are used to train various classifiers, with Linear Discriminant Analysis resulting in an accuracy of 93.3% with the TESS dataset.

Representative features

In this section, we provide a brief overview of the methods for computing four widely used features in speech and audio signal processing.

Mel frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCC)

MFCCs are derived from the Mel-frequency scale, which is designed to align with human auditory perception. Given a discrete-time audio signal \(s[n]\), let \(s_{\text {pre-emph}}[n]\) denote the signal after applying pre-emphasis, \(h[n]\) be the window function, and \(S(f)\) represents the magnitude spectrum obtained via FFT. The steps to compute MFCCs are as follows, as detailed in Eqs. (1 to 6):

- 1\(^o\):

-

Pre-emphasis: Apply a pre-emphasis filter to enhance high-frequency components of the signal.

$$\begin{aligned} s_{\text {pre-emph}}[n] = s[n] - \text {pre}\_\text {emph}\_\text {coef} \times s[n-1] \end{aligned}$$(1) - 2\(^o\):

-

Framing: Segment the pre-emphasized signal into short frames, typically ranging from 20 to 40 milliseconds, and apply a window function to each frame.

$$\begin{aligned} s_{\text {frame}}[n] = s_{\text {pre-emph}}[n] \times h[n] \end{aligned}$$(2) - 3\(^o\):

-

Fast Fourier Transform (FFT): Transform each frame from the time domain to the frequency domain by calculating its Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT).

$$\begin{aligned} S(f) = \text {DFT}\{s_{\text {frame}}[n]\} \end{aligned}$$(3) - 4\(^o\):

-

Mel-filterbank: Apply a filterbank consisting of triangular filters arranged according to the Mel scale to the magnitude spectrum derived from the FFT. Denote \(m[f]\) as the \(m\)-th frequency on the Mel scale.

$$\begin{aligned} G_m[f] = {\left\{ \begin{array}{ll} 0 & \text {if } f < m[f-1] \\ \frac{f - m[f-1]}{m[f] - m[f-1]} & \text {if } m[f-1] \le f \le m[f] \\ \frac{m[f+1] - f}{m[f+1] - m[f]} & \text {if } m[f] \le f \le m[f+1] \\ 0 & \text {if } f > m[f+1] \end{array}\right. } \end{aligned}$$(4) - 5\(^o\):

-

Logarithm: Compute the natural logarithm of the filterbank energies to approximate the human perception of loudness, where \(N\) is the FFT length.

$$\begin{aligned} E_m = \log \left( \sum _{f=0}^{N-1} |S(f)|^2 G_m[f] \right) \end{aligned}$$(5) - 6\(^o\):

-

Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT): Perform the DCT on the logarithm of the filterbank energies to transform and decorrelate the features, resulting in the MFCC coefficients.

$$\begin{aligned} \text {MFCC}_k = \sum _{i=0}^{F-1} \cos \left[ \frac{\pi }{F} \left( i + 0.5\right) k \right] E_m \end{aligned}$$(6)

where \(\text {MFCC}_k\) represents the resulting MFCC coefficients, and \(F\) denotes the number of Mel filters.

Zero crossing rate (ZCR)

The Zero Crossing Rate (ZCR) measures the rate at which the amplitude of a speech signal crosses the zero level within a given time frame. It is computed by averaging the number of zero-crossings across the length of the signal, as outlined in Eq. 7:

where \(x\) represents a signal of length \(N\), and \(\textbf{1}_{\{x_i x_{i-1} < 0\}}\) is an indicator function that equals 1 when the product \(x_i x_{i-1}\) is negative, indicating a zero-crossing, and 0 otherwise.

Root mean square energy (RMSE)

Root Mean Square Energy (RMSE) is computed for each frame of an audio signal to measure the average amplitude of the signal, independent of its sign. For a signal \(\textbf{a} = (a_1, a_2, \ldots , a_n)\), the Root Mean Square Energy (RMSE) value \(\text {RMSE}_{\textbf{a}}\) is computed as follows using Eq. 8:

Chroma short-time fourier transform

The computation of chroma features involves summarizing the spectral information of an audio signal into 12 bins, each representing a pitch class in the chromatic scale. The process is detailed below:

- 1\(^o\):

-

Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT): Begin by performing the STFT to obtain a time-frequency representation of the audio signal:

$$\begin{aligned} \text {STFT}(t, \xi ) = \sum _{m} \left[ x(m) \cdot g(m - t) \cdot e^{-j2\pi \xi m} \right] \end{aligned}$$(9)where \(x(m)\) denotes the signal value at time \(m\), \(g(m - t)\) represents the window function centered at time \(t\) and \(e^{-j2\pi \xi m}\) is the complex exponential for frequency \(\xi\).

- 2\(^o\):

-

Magnitude Spectrum: Calculate the magnitude spectrum from the STFT as shown in Eqn:10:

$$\begin{aligned} | \text {STFT}(t, \xi ) | = \sqrt{ \text {Re}\{\text {STFT}(t, \xi )\}^2 + \text {Im}\{\text {STFT}(t, \xi )\}^2 } \end{aligned}$$(10)where \(\text {Re}\{\cdot \}\) and \(\text {Im}\{\cdot \}\) represent the real and imaginary parts of the STFT.

- 3\(^o\):

-

Mapping Frequencies to Chroma Bins: Map the frequency bins to 12 pitch classes. Each pitch class corresponds to one of the 12 chroma bins (e.g., C, C#, D, D#, E, F, F#, G, G#, A, A#, B). For each chroma bin \(\gamma\), the chroma feature \(\text {Chroma}(t, \gamma )\) is obtained by summing the magnitudes of the STFT bins that fall into pitch class \(\gamma\) as shown in Eqn:11:

$$\begin{aligned} \text {Chroma}(t, \gamma ) = \sum _{\xi \in B_\gamma } | \text {STFT}(t, \xi ) | \end{aligned}$$(11)where \(B_\gamma\) denotes the set of frequency bins corresponding to pitch class \(\gamma\). The chroma feature \(\text {Chroma}(t)\) for a specific time \(t\) is a 12-dimensional vector, where each element indicates the intensity of one of the 12 pitch classes.

Implementation

Dataset

In this section, we briefly describe the distribution of samples across different emotion categories of the five datasets used in this work (see Table 1). The audio files for these multimodal datasets: SAVEE, RAVDESS, CREMA-D, TESS, and EmoDB are all publicly available.

The RAVDESS (Ryerson Audiovisual Database of Emotional Speech and Music): The RAVDESS is a prominent database frequently used in SER research. It features recordings from 24 professional actors, equally divided between 12 women and 12 men, each providing two types of utterances-one in speech and one in song. The audio clips are 3 seconds long and are labeled with various emotions, including happy, sad, angry, fear, surprise, neutral, and disgust. Each emotion is expressed in two intensity levels: normal and strong, resulting in a comprehensive collection of 2,076 audios.

The Toronto Emotional Speech Set (TESS): The Toronto Emotional Speech Set (TESS) is a dataset comprising audio recordings of two English-speaking actresses, aged 26 and 64. Each recording is two seconds in length and is categorized into one of seven emotions: anger, disgust, fear, happy, neutral, surprise, and sad. The dataset consists of 2,800 audio files, with 400 files allocated to each emotional category.

The SAVEE (Surrey Audio-Visual Expressed Emotion): The SAVEE dataset includes 480 spoken audio recordings performed by four English-speaking actors, who are between 27 and 31 years old. Each clip is approximately 3 seconds long and is labeled with one of seven emotions: anger, happy, neutral, disgust, sad, surprise, and fear.

The Crowdsourced Emotional Multimodal Actors (CREMA-D): The dataset comprises 7,442 unique audio samples recorded by 91 actors from a range of cultural and demographic backgrounds. The group includes 48 male and 43 female actors, each of whom recorded 12 sentences. The audio clips, averaging 2 seconds in length, convey six distinct emotions: angry, happy, disgust, sad, neutral, and fear.

Berlin Database of Emotional Speech (EmoDB): EmoDB, also referred to as the Berlin Emotion Dataset, is one of the most extensively used collections in SER. It consists of 535 voice utterances, each conveying one of six distinct emotions. The dataset includes recordings from five male and five female professional actors, who recited scripted phrases to express various emotions. Recorded at a sampling rate of 16 kHz, each recording lasts between 2 to 3 seconds. All utterances are standardized to fit within the same temporal window, ensuring consistent duration across the dataset.

Among the five datasets, most are relatively balanced, except for the EmoDB dataset, which is not balanced. In this study, with the RAVDESS dataset, the focus was on the speech segments disregarding the audio clips containing songs. As a result, instead of analyzing the entire set of 2076 audio files from the original dataset, only 1440 audio files that contain speech segments were used. Moreover, to ensure consistency across experiments with different datasets, we converted the sampling rate of all audio files to 22,050 Hz. To train the deep learning models, the datasets were split into three parts: 80% allocated for training, 10% for testing, and 10% for validation.

Experimental setup

This work was conducted within a Docker environment, utilizing an NVIDIA RTX 2080 GPU on a Windows 10 Education 64-bit system. The system was equipped with 32 GB of RAM and an Intel Core i7-9700k 3.60 GHz CPU. The models were developed and executed using the Keras python library (https://keras.io/api/ (accessed on March 23, 2024)). Visualizations of the results were generated using the Matplotlib library (https://matplotlib.org/ (accessed on March 23, 2024)) and the Seaborn library (https://seaborn.pydata.org/ (accessed on March 23, 2024)). Additionally, the SciKit-learn library (https://scikit-learn.org/stable/about.html (accessed on March 23, 2024)) was used to create evaluation metrics. Additionally, the Librosa library (https://librosa.org/ accessed on June 3, 2024) was used to load the audio data and adjust the sampling rate. Moreover, the Numpy library (https://numpy.org/ accessed on 29 December 2024) was used to generate Gaussian noise and handle the arrays.

Data augmentation and feature extraction process

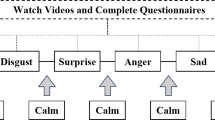

Fortunately, these datasets provide audio files containing only speech, eliminating the need for additional pre-processing steps to extract speech segments. Figure 2 describes the process of data augmentation and feature extraction.

Process (i) outlines the procedure for creating noise-augmented data (N.A.), (ii) details the process for pitch-shifted augmented audio data (P.A.), (iii) includes both noise-augmented and pitch-shifted audio data (N.A.+P.A.), and (iv) uses only non-augmented data (O.A.). Subsequently, all these data were processed for feature extraction and then concatenated to form the final feature set.

In the first method, noise from a normal (Gaussian) distribution was multiplied by a noise amplitude \(\alpha\) and added to the input data. The value for \(\alpha =0.035\) was experimentally determined to control the intensity of the added noise. The augmented noise was scaled to a maximum value before adding the noise to the input data. In the second method, the pitch-shifted audio was obtained by first applying a sampling rate SR and then altering the pitch by specified pitch factor (\(\beta\) =0.7) to achieve the desired modification. In the third method, a combined noise and pitch-shifted audio was used to generate the audio features.

For the feature extraction process, a frame length of 2,048 samples and a hop length of 512 samples were used. The length of the audio clip for the five selected datasets was typically between 2 to 3 seconds. As a result, we used 2.5 seconds for the feature extraction process. In addition, the offset parameter was set to 0.6 to ensure that sufficient features were available for extraction, especially considering that the beginning of the audio files often contained insufficient information for feature extraction.

The ZCR and RMSE features were computed, followed by a squeezing operation to remove singleton dimensions. MFCCS and Chroma features were also extracted and then converted into one-dimensional arrays. The extracted features were horizontally concatenated to form a single feature vector. We have extracted the features from both the augmented and non-augmented audio samples to create the final concatenated feature set consisting four components: N.A ., P.A., {(N.A.) + (P.A.)} and O.A..

Null values were replaced with zeroes to maintain data integrity. Also, data normalization was done to standardize each feature independently with the StandardScaler. The librosa library was used for pitch shifting and for extracting the four features. After augmentation, the RAVDESS training set had almost 4608 samples, each with 3672 features and 7 labels. The augmentation process increased the dataset size by almost three times the original dataset.

Model configuration and learning strategy

Table 2 gives the architectural configurations of our proposed CNN_Bi-LSTM model. Each convolutional block comprises 1D convolutional layers, BatchNormalization, and MaxPooling layers. After processing through the convolutional and LSTM layers, a Flattening layer is applied to the output. The flattened output is then passed through a Dense layer, activated by ReLU, followed by BatchNormalization and a Softmax classifier for emotion classification. Convolutional Blocks 1 and 3 do not incorporate dropout layers. However, for both the CNN and CNN_Bi-LSTM models, dropout layers were introduced in Blocks 2, 4, and 5 after the MaxPooling layers. The CNN model shares a similar structure but does not include the Bi-directional LSTM layer before the convolutional layers.

An ensemble method combining the CNN and CNN_Bi-LSTM models was employed to improve generalization and reduce individual model biases. Both models share an input layer, and their predictions are combined through an Average layer. The Adam optimizer and categorical cross-entropy loss function were employed for training, and the class labels were encoded using one-hot encoding.

Table 3 summarizes the parameter settings used for training the model. The first three convolutional layers use a kernel size of 5, followed by layers with a kernel size of 3, all with a stride of 1. The ReLU activation function introduces non-linearity, and a dropout rate of 20% helps prevent overfitting. Padding is consistently set to ”same” across convolutional and max-pooling layers to maintain the dimensions of the output feature map. The first four MaxPooling layers employ a pool size of ”2x2”, while the last MaxPooling layer uses a pool size of ”2x1”.

To prevent overfitting, early stopping was implemented by monitoring validation accuracy over five consecutive epochs. Additionally, an LR scheduler was used to optimize the training process by reducing the LR by 50% if validation accuracy failed to improve for three consecutive epochs. To prevent excessive reduction, a minimum LR of 0.00001 was set. The models were trained using a batch size of 64 for 100 epochs.

Results

In this section, Table 4 gives the results of our experiments and the best results highlighted in bold.

It is noteworthy that our proposed Ensemble model performed notably well by averaging the outputs of two base models (CNN and CNN_Bi-LSTM) with all five datasets, and consistently demonstrated a higher F1-score than the individual base models. With the EmoDB dataset, the ensemble model was performing slightly lower than the CNN model in terms of the accuracy metric and matched the performance of CNN_Bi-LSTM model for the RAVDESS dataset. While LSTM models are known for their effectiveness in analyzing time series data, our results show that the 1D CNN mostly outperformed the Bi-LSTM models.

Since the EmoDB dataset is the only dataset with class imbalance, it is worthwhile reviewing the class-wise performance of our proposed model to gain some insights into its generalization capabilities. Table 5 shows the breakdown of the metrics for each class. Our proposed ensemble model demonstrated exceptional performance with a precision of 100%, a recall of 94%, and an F1-score of 97% for the disgust emotion class, despite being based on just 17 samples. These results show the model’s effectiveness in handling classes with limited instances.

In optimizing a model’s performance, the choice of optimizer and LR is crucial. Analysis of the loss trends depicted in Fig. 3 revealed that during the initial 10 epochs, the model exhibited high validation loss while the training loss was considerably low. This discrepancy highlighted that the model is struggling with generalization to unseen data. To address this issue, a LR scheduler was introduced, which adjusted the LR from 0.01 to 0.005 in the 11th epoch. This adjustment led to significant improvements in both accuracy and loss reduction. Consequently, by the end of the training process, the model attained a training loss of 0.0095 and a validation loss of 0.0643.

A key consideration is whether all the features are essential for our experiments. Additionally, we need to verify if the model is making correct decisions, especially given its high accuracy. For this reason, the interpretability of the models is also crucial. DNNs are often regarded as ”black boxes,” making it challenging to understand their decision-making processes. To address this, we have used LIME which is lightweight and effective, providing valuable insights into how individual predictions are made. It allows us to identify which features contribute most to the model’s decisions, thereby enhancing our understanding and trust in the model’s outputs. Figure 4 shows LIME explanations for our proposed ensemble model’s predictions across different datasets, highlighting the impact of various features. By examining random test instances, we can identify significant features influencing the model’s decisions. The figure indicates that all features contribute, with some having positive influences and others negative. A more detailed explanation is given in sect. 6.

Table 6 provides a detailed comparison between our work and existing studies, highlighting accuracies, methodologies, and feature extraction techniques. Our method closely aligns with the approaches of Akinpelu et al.57, Ottoni et al.58, and Jothimani et al.59, which also utilize MFCC, RMSE, and ZCR features in training DNN models (also discussed in sect. 2). From Table 6, it can be observed that the models discussed in the two papers (Ottoni et al. and Akinpelu et al.) achieve 100% accuracy with the TESS datasets, though the methods and features used are different. What sets our work apart is the addition of the Chroma STFT features and refined model training strategies. Our proposed ensemble model outperforms Ottoni et al. with the SAVEE and CREMA-D datasets, surpassing their benchmark results with 98.43% and 98.66% accuracy, respectively. Similarly, while Jothimani et al. achieved 89.90% with the CREMA-D dataset, our proposed ensemble model significantly outperforms their model with 98.66% accuracy. Other researchers used temporal, entropy, and frame-level features but did not achieve strong performance across various datasets.

Discussion

In our approach, we employed both CNN-Bi-directional LSTM and 1D CNN models, which yielded promising results. Bi-directional LSTMs are particularly effective at capturing temporal dependencies present in audio data, allowing them to understand the context of previous and future audio frames. Concurrently, 1D CNNs are proficient at capturing patterns within frequency bands over time from sequential audio features, such as those derived from spectrograms. Unlike images where 2D CNNs excel at capturing spatial patterns, in the context of sequential audio data, 1D CNNs effectively capture local patterns along the temporal axis. Averaging the predictions from these complementary models potentially mitigates individual model biases and enhances overall robustness and performance in audio data analysis tasks. As a result, the averaging ensemble model excelled in this study across various datasets, as shown in Table 4.

The second noteworthy point is why the pipeline performed well on the imbalanced EmoDB dataset. The EmoDB dataset includes audio recordings of varying lengths, which could introduce feature space imbalances. For example, a 300-second audio clip generates significantly more features than a 3-second clip, potentially skewing the data. To mitigate this, we extracted uniform-length audio segments across different files, ensuring balanced feature representation and preventing potential data imbalances.

In the SAVEE dataset, we observed an interesting behavior in the CNN model (see Fig. 3). Initially, the model’s validation loss showed little improvement during the first ten epochs. However, as we decreased the LR, the accuracy began to increase steadily. This occurred because the dataset was small, providing the model with fewer examples to learn from. With a large LR, the model made significant changes to its weights during training, often overshooting and performing poorly. Conversely, with a smaller LR, the model made more gradual and careful adjustments to its weights, leading to better performance even with limited data.

Another aspect of this work is model optimization. We worked with datasets ranging from 7442 to 480 samples. CNNs, which are effective for large datasets, can overfit when the dataset is small. To address this, we fine-tuned the kernel sizes and filter sizes of the layers. Large models can overfit small datasets, while small models may underfit large datasets. Thus, we adjusted the model to find a balance that enhances performance across various datasets. Additionally, early stopping and regularization techniques were also beneficial in this experiment, as they prevented excessive training and helped avoid overfitting.

Moreover, the importance of chroma features across different datasets should be noted. Traditionally, chroma features have been used more for music analysis than for speech, with early research focusing mainly on MFCC and ZCR (see Table 6). However, as shown in Fig. 4, chroma features contribute significantly to predictions across almost all datasets. Chroma features capture harmonic and pitch information, which are crucial for recognizing emotions in speech. They effectively represent variations in pitch and harmonic content, complementing features like MFCC and ZCR by adding harmonic details. This creates a more comprehensive feature set, helping the model better distinguish between emotional states and improving performance across various datasets, highlighting the robustness and relevance of chroma features in SER.

From Fig. 4, it is evident that CREMA-D, RMSE, MFCC, and ZCR features are significant contributors, with RMSE having the highest impact. In the SAVEE dataset, ZCR shows both positive and negative influences, indicating its complex role. TESS relies heavily on Chroma features, suggesting the importance of tonal information. RAVDESS also emphasizes Chroma and MFCC, with ZCR having a notable negative influence. EmoDB presents an interplay of Chroma, MFCC, RMSE, and ZCR, with contributions varying across different value ranges. Overall, RMSE, MFCC, ZCR, and Chroma are consistently important, though their relative importance varies by dataset.

Additionally, the lack of data poses another challenge; the models struggle with generalization due to insufficient training data. Models trained on one dataset may not perform well on another because of the limited data, diverse emotion classes, and a lack of variety in the speeches. For example, in the Crema-D dataset, the same sentence is expressed in different ways to represent various emotion classes. On the other hand, datasets like EmoDB and SAVEE contain a limited number of samples.

Conclusion

In this paper, we thoroughly explored data augmentation techniques and employed classical audio feature extraction methods such as ZCR, RMSE, Chroma STFT, and MFCC, with five well-known multimodal datasets illustrating their significance in SER. Additionally, we conducted extensive experiments with learning schedulers and regularization techniques to construct an effective ensemble model. This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of feature extraction methods, including RMSE, ZCR, MFCC, and Chroma STFT, and to examine how regularization techniques and learning rate schedulers impact the performance of models built using simpler CNN variants, as opposed to more complex and resource-demanding architectures. This work has shown that our proposed ensemble model surpasses the performance of the spectrogram-based model, as indicated in Table 4.

However, this study has its limitations. Hand-crafted feature extraction techniques proved to be time-consuming and resource-intensive. Using raw audio directly with 1D CNN and LSTM models could save time, but it may impact the emotion recognition rate for this study. Therefore, a trade-off must be considered between processing time and accuracy in emotion detection. In our future work, we will explore advanced models for automated extraction of audio speech features, coupled with the implementation of a robust classification method to accurately discern speech emotions. Model optimization techniques, diverse data augmentation methods, feature extraction, and cross-dataset validation could improve efficiency and generalization. Additionally, enhancing model interpretability and conducting user-centric evaluations would refine the system and assess its practical impact.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available at: 1. TESS: Toronto emotional speech set (TESS) https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/ejlok1/toronto-emotional-speech-data 2. CREMAD: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/ejlok1/cremad/data 3. RAVDESS: RAVDESS Emotional speech audio https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/uwrfkaggler/ravdess-emotional-4. SAVEE: Surrey Audio-Visual Expressed Emotion (SAVEE) https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/ejlok1/ surrey-audiovisual-expressed-emotion-savee 5. EmoDB: EmoDB Dataset https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/piyushagni5/berlin-database-of-emotional-data

References

Ekman, P. Cross-cultural studies of facial expression. In Darwin and Facial Expression: A Century of Research in Review (ed. Ekman, P.) 169–222 (Academic Press, New York, 1973).

Ragsdale, J. W., Van Deusen, R., Rubio, D. & Spagnoletti, C. Recognizing patients’ emotions: teaching health care providers to interpret facial expressions. Acad. Med. 91, 1270–1275 (2016).

Suhaimi, N. S. et al. EEG-based emotion recognition: A state-of-the-art review of current trends and opportunities. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2020, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8875426 (2020).

Baek, J.-Y. & Lee, S.-P. Enhanced speech emotion recognition using DCGAN-based data augmentation. Electronics 12, 3966 (2023).

Zavarez, M. V., Berriel, R. F. & Oliveira-Santos, T. Cross-database facial expression recognition based on fine-tuned deep convolutional network. In 2017 30th SIBGRAPI conference on graphics, patterns and images (SIBGRAPI), 405–412, https://doi.org/10.1109/SIBGRAPI.2017.60 (2017).

Ottoni, L. T. C. & Cerqueira, J. d. J. F. A review of emotions in human-robot interaction. In 2021 Latin American robotics symposium (LARS), 2021 Brazilian symposium on robotics (SBR), and 2021 workshop on robotics in education (WRE), 7–12 (organizationIEEE, 2021).

Martins, P. S., Faria, G. & Cerqueira, J. d. J. F. I2E: A cognitive architecture based on emotions for assistive robotics applications. Electronics9, 1590 (2020).

Abdul, Z. K. & Al-Talabani, A. K. Mel frequency cepstral coefficient and its applications: a review. IEEE Access 10, 122136–122158 (2022).

Gouyon, F., Pachet, F., Delerue, O. et al. On the use of zero-crossing rate for an application of classification of percussive sounds. In Proceedings of the COST G-6 conference on digital audio effects (DAFX-00), Verona, Italy, vol. 5, 16 (2000).

Ganchev, T., Mporas, I. & Fakotakis, N. Audio features selection for automatic height estimation from speech. In Artificial intelligence: theories, models and applications: 6th hellenic conference on AI, SETN 2010, Athens, Greece, May 4-7, 2010. Proceedings 6, 81–90 (organizationSpringer, 2010).

Gu, J. et al. Recent advances in convolutional neural networks. Pattern Recogn. 77, 354–377 (2018).

Senthilkumar, N., Karpakam, S., Devi, M. G., Balakumaresan, R. & Dhilipkumar, P. Speech emotion recognition based on Bi-directional LSTM architecture and deep belief networks. Mater. Today Proc. 57, 2180–2184 (2022).

Rehman, A. U., Malik, A. K., Raza, B. & Ali, W. A hybrid CNN-LSTM model for improving accuracy of movie reviews sentiment analysis. Multimed. Tools Appl. 78, 26597–26613 (2019).

Shahid, F., Zameer, A. & Muneeb, M. Predictions for COVID-19 with deep learning models of LSTM, GRU and Bi-LSTM. Chaos, Solitons Fract. 140, 110212 (2020).

Dey, A. et al. A hybrid meta-heuristic feature selection method using golden ratio and equilibrium optimization algorithms for speech emotion recognition. IEEE Access 8, 200953–200970 (2020).

Gold, B., Morgan, N. & Ellis, D. Speech and Audio Signal Processing: Processing and Perception of Speech and Music Wiley, London 2011).

Mermelstein, P. Distance measures for speech recognition, psychological and instrumental. Pattern Recognit. Artif. Intell. 116, 374–388 (1976).

Livingstone, S. R. & Russo, F. A. The Ryerson audio-visual database of emotional speech and song (RAVDESS): a dynamic, multimodal set of facial and vocal expressions in north American English. PLoS ONE 13, e0196391 (2018).

Dupuis, K. & Pichora-Fuller, M. K. Toronto emotional speech set TESS (University of Toronto, Psychology Department, 2010).

Jackson, P. & Haq, S. Surrey Audio-visual Expressed Emotion (SAVEE) Database (University of Surrey, Guildford, UK, 2014).

Cao, H. et al. CREMA-D: crowd-sourced emotional multimodal actors dataset. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 5, 377–390 (2014).

Burkhardt, F. et al. A database of German emotional speech. Interspeech 5, 1517–1520 (2005).

Ribeiro, M. T., Singh, S. & Guestrin, C. ” why should i trust you?” explaining the predictions of any classifier. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining, 1135–1144 (2016).

Zehra, W., Javed, A. R., Jalil, Z., Khan, H. U. & Gadekallu, T. R. Cross corpus multi-lingual speech emotion recognition using ensemble learning. Complex Intell. Syst. 7, 1845–1854 (2021).

Eyben, F. Real-Time Speech and Music Classification by Large Audio Feature Space Extraction Springer, 2015.

Eyben, F. et al. The Geneva minimalistic acoustic parameter set (GeMAPS) for voice research and affective computing. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 7, 190–202 (2015).

Eyben, F., Wöllmer, M. & Schuller, B. Opensmile: the Munich versatile and fast open-source audio feature extractor. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM international conference on Multimedia, 1459–1462 (2010).

Mustaqeem & Kwon, S. A CNN-Assisted Enhanced Audio Signal Processing for Speech Emotion Recognition. Sensors20, 183 (2019).

Zhao, J., Mao, X. & Chen, L. Speech emotion recognition using deep 1D & 2D CNN LSTM networks. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 47, 312–323 (2019).

Guo, L. et al. Speech emotion recognition by combining amplitude and phase information using convolutional neural network. In INTERSPEECH, 1611–1615 (2018).

Ancilin, J. & Milton, A. Improved speech emotion recognition with Mel frequency magnitude coefficient. Appl. Acoust. 179, 108046 (2021).

Al Dujaili, M. J., Ebrahimi-Moghadam, A. & Fatlawi, A. Speech emotion recognition based on SVM and KNN classifications fusion. Int. J. Electric. Comput. Eng. 11, 1259 (2021).

Sheikhan, M., Bejani, M. & Gharavian, D. Modular neural-SVM scheme for speech emotion recognition using ANOVA feature selection method. Neural Comput. Appl. 23, 215–227 (2013).

Lanjewar, R. B., Mathurkar, S. & Patel, N. Implementation and comparison of speech emotion recognition system using Gaussian mixture model (GMM) and K-nearest neighbor (K-NN) techniques. Proc. Comput. Sci. 49, 50–57 (2015).

Özseven, T. A novel feature selection method for speech emotion recognition. Appl. Acoust. 146, 320–326 (2019).

Martin, O., Kotsia, I., Macq, B. & Pitas, I. The eNTERFACE’05 audio-visual emotion database. In 22nd international conference on data engineering workshops (ICDEW’06), 8–8 (organizationIEEE, 2006).

Costantini, G., Iaderola, I., Paoloni, A., Todisco, M. et al. EMOVO corpus: An Italian emotional speech database. In Proceedings of the ninth international conference on language resources and evaluation (LREC’14), 3501–3504 (organizationEuropean Language Resources Association (ELRA), 2014).

Noroozi, F., Sapiński, T., Kamińska, D. & Anbarjafari, G. Vocal-based emotion recognition using random forests and decision tree. Int. J. Speech Technol. 20, 239–246 (2017).

Jacob, A. Modelling speech emotion recognition using logistic regression and decision trees. Int. J. Speech Technol. 20, 897–905 (2017).

Basu, S., Chakraborty, J. & Aftabuddin, M. Emotion recognition from speech using convolutional neural network with recurrent neural network architecture. In 2017 2nd international conference on communication and electronics systems (ICCES), 333–336 (organizationIEEE, 2017).

Xie, Y. et al. Speech emotion classification using attention-based LSTM. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Language Process 27, 1675–1685 (2019).

Diao, H., Hao, Y., Xu, S. & Li, G. Implementation of lightweight convolutional neural networks via layer-wise differentiable compression. Sensors 21, 3464 (2021).

Manohar, K. & Logashanmugam, E. Hybrid deep learning with optimal feature selection for speech emotion recognition using improved meta-heuristic algorithm. Knowl. Based Syst. 246, 108659 (2022).

Fahad, M. S., Deepak, A., Pradhan, G. & Yadav, J. DNN-HMM-based speaker-adaptive emotion recognition using MFCC and epoch-based features. Circ. Syst. Signal Process. 40, 466–489 (2021).

Singh, P., Sahidullah, M. & Saha, G. Modulation spectral features for speech emotion recognition using deep neural networks. Speech Commun. 146, 53–69 (2023).

Seo, M. & Kim, M. Fusing visual attention CNN and bag of visual words for cross-corpus speech emotion recognition. Sensors https://doi.org/10.3390/s20195559 (2020).

Bautista, J. L., Lee, Y. K. & Shin, H. S. Speech emotion recognition based on parallel CNN-attention networks with multi-fold data augmentation. Electronics https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics11233935 (2022).

Kim, S. & Lee, S.-P. A BiLSTMTransformer and 2D CNN architecture for emotion recognition from speech. Electronics https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics12194034 (2023).

Pan, S.-T. & Wu, H.-J. Performance improvement of speech emotion recognition systems by combining 1D CNN and LSTM with data augmentation. Electronics 12, 2436 (2023).

Zeng, Y., Mao, H., Peng, D. & Yi, Z. Spectrogram based multi-task audio classification. Multimed. Tools Appl. 78, 3705–3722 (2019).

Issa, D., Demirci, M. F. & Yazici, A. Speech emotion recognition with deep convolutional neural networks. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 59, 101894 (2020).

Pawar, M. D. & Kokate, R. D. Convolution neural network based automatic speech emotion recognition using mel-frequency cepstrum coefficients. Multimed. Tools Appl. 80, 15563–15587 (2021).

Bhangale, K. & Kothandaraman, M. Speech emotion recognition based on multiple acoustic features and deep convolutional neural network. Electronics 12, 839 (2023).

Badshah, A. M. et al. Deep features-based speech emotion recognition for smart affective services. Multimed. Tools Appl. 78, 5571–5589 (2019).

Chen, S. et al. Wavlm: large-scale self-supervised pre-training for full stack speech processing. IEEE J. Selected Topics Signal Process. 16, 1505–1518 (2022).

wen Yang, S. et al. SUPERB: Speech processing Universal Performance Benchmark (2021). 2105.01051.

Akinpelu, S., Viriri, S. & Adegun, A. Lightweight deep learning framework for speech emotion recognition. IEEE Access (2023).

Ottoni, L. T. C., Ottoni, A. L. C. & Cerqueira, J. D. J. F. A deep learning approach for speech emotion recognition optimization using meta-learning. Electronics 12, 4859 (2023).

Jothimani, S. & Premalatha, K. MFF-SAug: Multi feature fusion with spectrogram augmentation of speech emotion recognition using convolution neural network. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 162, 112512 (2022).

Jiang, P., Fu, H., Tao, H., Lei, P. & Zhao, L. Parallelized convolutional recurrent neural network with spectral features for speech emotion recognition. IEEE Access 7, 90368–90377. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2927384 (2019).

Li, Y., Tao, J., Chao, L., Bao, W. & Liu, Y. CHEAVD: A Chinese natural emotional audio-visual database. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 8, 913–924 (2017).

Schuller, B., Arsic, D., Rigoll, G., Wimmer, M. & Radig, B. Audiovisual behavior modeling by combined feature spaces. In 2007 IEEE international conference on acoustics, speech and signal processing-ICASSP’07, vol. 2, II–733 (organizationIEEE, 2007).

Mustaqeem & Kwon, S. A CNN-assisted enhanced audio signal processing for speech emotion recognition. Sensors, https://doi.org/10.3390/s20010183 (2020).

Wen, G. et al. Self-labeling with feature transfer for speech emotion recognition. Knowl. Based Syst. 254, 109589 (2022).

Guizzo, E., Weyde, T., Scardapane, S. & Comminiello, D. Learning speech emotion representations in the quaternion domain. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Language Process. 31, 1200–1212 (2023).

Meng, H., Yan, T., Yuan, F. & Wei, H. Speech emotion recognition from 3D log-mel spectrograms with deep learning network. IEEE Access 7, 125868–125881. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2938007 (2019).

Kwon, S. et al. MLT-DNet: speech emotion recognition using 1D dilated CNN based on multi-learning trick approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 167, 114177 (2021).

Speech emotion recognition. Krishnan, P. T., Joseph Raj, A. N. & Rajangam, V. Emotion classification from speech signal based on empirical mode decomposition and non-linear features. Complex & Intelligent Systems 7, 1919–1934 (2021).

Mustaqeem, Sajjad, M. & Kwon, S. Clustering-based speech emotion recognition by incorporating learned features and deep BiLSTM. IEEE Access8, 79861–79875, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2990405 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by Shastri Indo-Canadian Institute under the Shastri Scholar Travel Subsidy Grant (SSTSG) 2023-24 & and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant #194376.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The conceptualization and methodology were developed by JC, SR, and KK. JC handled data curation, software development, and validation, as well as taking the lead preparing the original draft for writing. SR and KK conducted the review and editing, supervision of the writing. Funding for the resources utilized in the experiments were provided by SR and KK. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chowdhury, J.H., Ramanna, S. & Kotecha, K. Speech emotion recognition with light weight deep neural ensemble model using hand crafted features. Sci Rep 15, 11824 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95734-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95734-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

SBT-Net: a tri-cue guided multimodal fusion framework for depression recognition

BioData Mining (2025)