Abstract

This study aimed to characterize virulence and antibiotic resistance genes in multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from cases of subclinical mastitis (SCM) in buffaloes. A cross-sectional study was conducted on 1540 quarter milk samples collected from 385 buffaloes. Milk samples were screened using the California Mastitis Test and Modified Whiteside Test. Positive samples underwent bacterial culture, biochemical tests, biofilm detection and molecular analysis for pathogen identification and detection of virulence, resistance, and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) genes. The prevalence of SCM was 67.9% (1046/1540) at the quarter level and 80.8% (311/385) at the animal level. E. coli was identified in 9.5% (146/1540) of the samples, while K. pneumoniae was detected in 9.09% (140/1540). Virulence genes, such as stx1 (27.4%), and resistance genes, including aac(3)-iv (77.4%) and tetA (76.7%), exhibited higher prevalence. Additionally, β-lactamase genes, notably blaTEM (67.1%), and ESBL genes, such as blaCTX-M1, were detected. Biofilm formation was detected in 83.6% (122/146) of E. coli isolates and 75.7% (106/140) of K. pneumoniae isolates. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing revealed significant resistance to ampicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, and aminoglycosides. MDR was observed in 31.5% of E. coli and 39.3% of K. pneumoniae isolates, with XDR rates of 8.9% and 12.9%, respectively. These findings underscore the alarming spread of resistant pathogens in SCM-affected buffaloes, emphasizing the urgent need for ongoing surveillance and targeted intervention strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Milk and dairy products are crucial protein sources in lower middleincome ountries (LMICs). Buffaloes are the world’s second-largest producer, accounting for 12% of global milk production, mainly from India (53%) and Pakistan (68%)1,2. In Bangladesh, the buffalo population stands at approximately 1.464 million, managed predominantly through household subsistence systems and extensive free-range (Bathan) grazing practices3. The nation’s total buffalo milk production is estimated at 7.27 million metric tons per year4. However, buffalo milk is more expensive than cow milk because it contains more fat (6.0–8.5%) and nutrition3,4. Although cows produce over 90% of the milk in Bangladesh, persistent shortages have led to the promotion of buffaloes as an additional milk source5,6. However, subclinical mastitis (SCM) remains a major constraint, contributing to the decline in per capita milk production in the dairy sector2. Although SCM is 15–40 times more common than clinical mastitis (CM), it is more difficult to identify because of subtle changes in milk, which results in significant decreases in milk supply7,8. As determined by the CMT, the prevalence of SCM in Bangladesh ranges from 20 to 44% in cows and up to 81.6% in buffaloes9,10. It is highly prevalent in the dairy industry and causes substantial financial losses of $2.11 million USD yearly. It is caused mostly by contagious and environmental pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus spp., Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella spp.9,11,12,13.

In addition, rise of bacterial resistance poses a growing threat as resistance mechanism continue to spread globally14. The rise of multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacterial infections from various sources has been documented in a number of recent studies, which highlights the importance of using antibiotics appropriately. In addition to screening for emerging MDR strains, antimicrobial susceptibility testing should routinely use to identify the preferred antibiotics15.

E. coli is the major cause of mastitis, leading to subclinical and clinical form of mastitis16. Shiga toxin (stx1, stx2) and MDR extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing E. coli is among the most significant virulence factors identified in E. coli strains isolated from mastitic milk in buffaloes17,18,19. STEC virulence factors include Shiga toxins (stx1 and stx2), which drive disease severity, intimin (eae), which aids host cell attachment, and hemolysin (hlyA), which promotes cell lysis and invasion20. Hemolytic uremia and hemorrhagic colitis are the two primary conditions linked to STEC infection in humans. Given that STEC has been implicated in a number of food-borne epidemics, it is of significant public health relevance21. Over the years, MDR E. coli strains have been consistently isolated from cases of SCM in dairy animals, underscoring a persistent issue. These MDR strains represent substantial public health hazards, particularly when raw milk is consumed without pasteurization22.

Klebsiella spp. also play a significant role in mastitis, particularly K. pneumoniae and K. oxytoca, which are prominent species that cause mastitis in both environmental and host contexts, resulting in substantial global economic impacts23,24. Many strains of K. pneumoniae possess virulence factors that increase pathogenicity by promoting infection, increasing bacterial fitness, and facilitating the evasion of host immune responses. In addition, the presence of ESBL-producing MDR Klebsiella spp. in SCM is an emerging concern, and their presence in dairy herds can complicate treatment strategies and has significant implications for animal health, milk safety, and public health because of the potential for transmission of resistant bacteria25. Biofilms are structured communities of bacteria encased in a self-produced extracellular polymeric matrix composed of polysaccharides, proteins, and DNA26. Biofilm formation enables bacteria to withstand harsh conditions and resist antibacterial agents. Both E. coli and K. pneumoniae have the potential to produce biofilms, which enhance their protection against potent antibiotics and contribute to drug resistance. The key genes associated with biofilm formation include lasR, lecA, and pelA in E. coli, while mrkA and mrkD play a crucial role in K. pneumoniae26.

Additionally, antibiotic resistance, often resulting from inconsistent antibiotic use, can reduce treatment efficacy27. Antibiotics are commonly used in dry cow therapy and to treat CM or SCM caused by bacterial pathogens. Given that culling animals to prevent disease spread is economically unfeasible, evaluating the antibiogram profile of bacterial strains is crucial for developing effective treatments2. For example, previous studies employing the disk diffusion method revealed that Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) serogroups isolated from mastitic milk presented the highest resistance to penicillin (100%), followed by tetracycline (57.44–92.2%), streptomycin (48.93–90.4%), nalidixic acid (88.3%), amikacin (86.5%), cephalothin (84.8%), ampicillin (46.80%), and sulfamethoxazole (40.42%). Additionally, 65.8% of the isolates were found to be MDR28,29. On the other hand, Klebsiella spp. presented the highest resistance to ampicillin (90–100%), followed by gentamicin (10–30%), tetracycline (60–80%), and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (30–50%), and the lowest resistance to chloramphenicol (5–15%) and enrofloxacin (5–20%)30,31,32. Notably, most research has predominantly focused on cows and contagious pathogens, with limited studies on SCM in buffaloes caused by environmental pathogens like E. coli and K. pneumoniae which exhibit pathogenic effects similar to those of contagious mastitogens. Based on this background, the study aimed to assess the prevalence of E. coli and K. pneumoniae in milk samples from buffaloes with subclinical mastitis in Bangladesh, also focusing on their antimicrobial resistance patterns especially MDR/XDR pattern and virulence genes.

Methods

Ethical consideration

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Sylhet Agricultural University, Sylhet-3100, Bangladesh, under animal use protocol number #AUP2023001. All experimental procedures were conducted by trained professionals in strict compliance with the university’s ethical guidelines and regulations. The welfare and well-being of all animals involved in the study were prioritized and carefully maintained throughout the research.

Study design, location and sampling strategy

A cross-sectional investigation was conducted in five predominantly buffalo populated Upazilas in Sylhet district of Bangladesh, namely, Jaintapur, Gowainghat, Kanaighat, Balaganj, and Fenchuganj. These regions are situated within geographic coordinates of approximately 24°36’ to 25°11’ North latitude and 91°38’ to 92°30’ East longitude, as depicted in Fig. 1. The study population required to estimate prevalence was calculated via a standard equation33,34.

where n = Desired sample size; Z = 1.96 for the 95% confidence interval; Pexp = 0.5, Expected prevalence (50%); d = 0.05, Desired absolute precision (5%).

On the basis of the calculations, to determine the prevalence of SCM, milk samples from 384 buffaloes (1536 quarter milk samples) were needed. With the goal of ascertaining the prevalence at the quarter and animal levels, 1540 quarter milk samples were collected from 385 swamp buffaloes. A random-cluster sampling technique was employed to accumulate the samples between February 2023 and June 2024.

Initial screening of the SCM

The milk samples were collected aseptically from each quarter of apparently healthy buffaloes, in accordance with the guidelines of National Mastitis Council (NMC)35. The modified Whiteside test (MWST), delineated by Emon et al.36 and the California Mastitis Test (CMT)37 were applied as preliminary screening methods for detecting SCM38. Following aseptic milk collection, the samples were mixed on a CMT paddle with reagent at an established ratio. The mixture was then gently swirled, and the reaction was monitored for changes in consistency. The milk was graded from strong (Grade 3+), which was defined by a fairly thick consistency and pronounced gel formation, to negative (Grade 0), where there was no change in viscosity and the milk remained liquid. Varying levels of thickening and gel formation/coagulation of SCM-positive milk were indicated by intermediate grades, which included a thick consistency with pronounced gel formation (grade 2+), noticeable thickening with slight coagulation (grade 1+), and slight thickening with no gel formation (graded as trace)39. Pre-enrichment of the predominantly positive milk samples was carried out in Trypticase Soy Broth (HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India) at a 1:10 dilution. The cultures were then incubated for approximately 24 h at 37 °C.

Isolation and identification of pathogens

The isolation and identification of E. coli was performed via the use of Eosin Methylene Blue (EMB) agar plates (HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India) following the guidelines and procedures of the NMC, USA. The agar plate was incubated at 37 °C for 18 to 24 h40. Further confirmation was achieved through biochemical assays41, including Gram staining, catalase, coagulase, citrate, motility, indole, gas production, methyl red, urease, and triple sugar iron tests42.

Klebsiella spp. (K. pneumomiae, K. oxytoca) were isolated and identified via McConkey agar medium (HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India). The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 to 48 h26. Confirmation was performed using biochemical tests, including Gram staining, catalase, coagulase, citrate, motility, indole, gas production, methyl red, urease, and triple sugar iron tests43. Following these analyses, positive samples were prepared for genomic DNA extraction and polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Genomic DNA extraction

The well-established boiling method was utilized to extract genomic DNA from E. coli and several Klebsiella spp. as previously described by Aldous et al.44. The purity and concentration of the extracted DNA were evaluated using a NanoDrop 2000c spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The monoplex PCR assays targeted the alr, pehX, stx1, and stx2 genes for detection, along with aac(3)-IV and sul1, which confer resistance to aminoglycosides and sulfonamides, respectively. The multiplex PCR assays focused on the gyrA, rpoB, blaTEM, blaSHV, blaOXA, blaCTX-M-grp1, blaCTX-M-grp2, blaCTX-M-grp9, MulticaseACC, MulticaseMOX, MulticaseDHA, tetA, and strA genes.

Molecular detection of pathogens and resistance genes

The molecular detection of E. coli, Klebsiella spp. and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) was conducted using different PCR techniques. For the detection of E. coli and K. oxytoca, monoplex PCR was used to target the alr and pehX genes, respectively, utilizing reagents from Addbio Inc. (Daejeon, South Korea). Similarly, resistance to gentamicin and sulfonamides was assessed by monoplex PCR amplification of the aac(3)-iv and sul1 genes, respectively. Additionally, multiplex PCR assays were executed to amplify specific genes for the presence of the Klebsiella genus (gyrA), K. pneumoniae (rpoB), Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (stx1 and stx2), and various ESBL genes, including blaTEM, blaSHV, blaOXA, blaCTX-M-grp1, blaCTX-M-grp2, blaCTX-M-grp9, MultiCaseACC, MultiCaseMOX, and MultiCaseDHA, along with the tetA and strA genes for tetracycline and streptomycin resistance, respectively. The composition of the PCR mixture and amplification conditions for these monoplex and multiplex assays are detailed in Supplementary Table S1. All amplified products were verified through gel electrophoresis on a 1.8% or 1.5% low-melting agarose gel, and a 100 bp plus ladder was used for size verification. The primer sequences for all the targeted genes are outlined in Supplementary Table S2.

Qualitative detection of biofilm producer

Congo red agar (CRA) method

Following the procedure outlined by Freeman et al.45, the Congo Red Agar (CRA) method was used to evaluate the bacterial isolates’ capacity to form biofilms. Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) agar was supplemented with 0.8 g/L Congo Red and 36 g/L sucrose to create the CRA media (HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India). After being streaked onto the CRA plates, the bacterial isolates were cultured for 24 to 48 h at 37 °C in an aerobic environment. Colony morphology was used to determine biofilm production: colonies that were crystalline, dry, and black were categorized as strong biofilm producers, whereas those that were smooth or red were categorized as weak or non-biofilm producers.

Crystal violet microtiter plate (CVMP) assay

The biofilm-forming ability of bacterial isolates was assessed using the Crystal Violet Microtiter Plate (CVMP) assay following the protocol of Kouidhi et al.46. Overnight bacterial cultures were adjusted to 0.5 McFarland standard and diluted 1:100 in Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) supplemented with 1% glucose to promote biofilm formation. A 96-well flat-bottom microtiter plate was used, where 200 µL of the diluted bacterial suspension was inoculated into each test well. Negative control wells contained only sterile TSB with 1% glucose. The plate was incubated at 37 °C for 24 h under static conditions. Following incubation, non-adherent cells were removed by gently washing three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2). The adhered biofilm was then stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 15 min at room temperature. Excess stain was removed by washing the wells three times with sterile distilled water, and the bound dye was solubilized using 95% ethanol. Finally, the absorbance was measured at 570 nm (OD570) using a microplate reader, and biofilm production was classified based on OD570 values, with non-biofilm (OD ≤ 0.2), weak (0.2 < OD ≤ 0.4), moderate (0.4 < OD ≤ 0.6), and strong (OD > 0.6) biofilm producers determined accordingly.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

The Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method was used to perform antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) on Mueller‒Hinton agar (HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India) plates in accordance with the guidelines established by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI)47. Thirteen antibiotics, belonging to eight different antimicrobial classes, included the following: penicillin (ampicillin 10 µg, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid 20/10 µg), tetracycline (tetracycline 30 µg), macrolides (azithromycin 15 µg), quinolones (ciprofloxacin 5 µg, nalidixic acid 30 µg), folate pathway antagonists (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 1.25/23.75 µg), phenicol (chloramphenicol 30 µg), cephalosporins (cefoxitin 30 µg, ceftriaxone 30 µg), and aminoglycosides (gentamicin 10 µg, amikacin 30 µg, streptomycin 10 µg). A bacterial suspension was prepared by selecting 3–5 colonies from a fresh overnight culture and suspending them in normal saline to match the 0.5 McFarland turbidity standard (~ 1.5 × 108 CFU/mL). The 0.5 McFarland turbidity standard was prepared using the protocol followed by48. The suspension was then evenly streaked across the entire surface of a Mueller–Hinton agar (MHA) plate using a sterile cotton swab. After allowing the plate to dry for 3–5 min, antibiotic discs were placed, maintaining a minimum center-to-center distance of 24 mm. The plate was then incubated at 37 °C for 16–18 h. Finally, the diameter of the inhibition zone was measured in millimeters using a ruler compared to the CLSI breakpoints. Each assay was conducted in triplicate to ensure accuracy and reproducibility.

Evaluation of MAR index, MDR, and XDR patterns in bacterial isolates

The multiple antibiotic resistance (MAR) index was obtained using the following formula outlined by Naser et al.33. MAR = (number of antibiotics exhibiting resistance by an isolate)/ (total number of antibiotics subjected to testing). The MAR index values ranged from 0 to 1, with values closer to 0 denoting increased sensitivity and those close to 1 denoting strong resistance. A high-risk reservoir of bacterial contamination or a significant degree of resistance was indicated by a MAR value of 0.20 or above. Furthermore, MDR is defined as nonsusceptibility to at least one agent in three antimicrobial categories or three classes of antibiotic whereas nonsusceptibility to at least one agent in all but 2 or fewer antimicrobial categories is termed as XDR49.

Statistical analysis

Excel spreadsheets were used for meticulous compilation, organization, and structuring of the accumulated data. A chi-square test was conducted to investigate associations among diverse explanatory variables through univariate analysis. Using the binomial exact test, confidence intervals were computed, with a significance threshold set at p < 0.05. SPSS version 26 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) was used to perform all the statistical analyses.

Geospatial mapping and plotting

ArcMap 10.8 (ArcMap 10.8, Esri, USA), with a shapefile sourced from www.diva-gis.org, was used to map the study area. The creation of a dot map effectively visualizes the sample cluster of buffalo habitat in Sylhet, Bangladesh. We generated the plot using GraphPad Prism 8.4.

Results

Phenotypic characteristics of the recovered pathogens

The recovered E. coli isolates exhibited circular, opaque colonies with a characteristic green metallic sheen on EMB agar. In Gram staining, they appeared as Gram-negative, rod-shaped (bacilli) bacteria, displaying a pink coloration. Biochemically, E. coli was catalase-positive, coagulase-negative, citrate-negative, indole-positive, methyl red-positive, urease-negative, and demonstrated positive fermentation for both glucose and lactose in the TSI test.

For Klebsiella spp., the colonies appeared as mucoid, sticky, pink colonies on MacConkey agar. Biochemically, they were Gram-negative, catalase-positive, coagulase-negative, citrate-positive, indole-negative, gas production-positive, methyl red-negative, and urease-positive.

Animal and quarter-level prevalence of SCM

At the animal and quarter levels, there was significant geographical variation in the occurrence of SCM (Fig. 2). The high pathogen burden and regional variation within the study area were highlighted by the quarter-level prevalence, which was 67.9% (95% CI 65.5–70.3%), and the overall animal-level prevalence across all areas, which was 80.8% (95% CI 76.5–84.6%).

Prevalence patterns of E. coli and K. pneumoniae

A bacteriological examination of 1,540 quarter milk samples collected from buffaloes revealed an overall E. coli prevalence of 9.5% (n = 146) and Klebsiella spp. of 21.5% (n = 332) based on molecular tests (Table 1). The prevalence of E. coli and Klebsiella spp. was assessed using culture-biochemical assays and PCR across five distinct habitats in Sylhet (Fig. 3a, b). Gowainghat had the highest prevalence of E. coli (35% by culture/biochemical methods), indicating a significant bacterial presence in this area, while other regions displayed relatively lower prevalence levels (6.3%–8.3%). Conversely, the prevalence of Klebsiella spp. was highest in Kanaighat (45.7% culture), followed by Gowainghat (35%) and Jaintapur (32.5%), suggesting favorable local conditions. Gowainghat was detected as a pathogen hotspot, with a molecular prevalence of 25% for E. coli and a 20% for K. pneumoniae (Fig. 3c). Kanaighat presented a significant K. pneumoniae prevalence (17.9%), whereas Balaganj and Fenchuganj presented minimal pathogen presence (3.3% each), suggesting lower bacterial pressure. An aggregate view of both pathogens was shown, with E. coli being slightly more prevalent (9.48%) than K. pneumoniae (9.09%), as illustrated in Fig. 3d. This study did not find any K. oxytoca in SCM-positive milk samples.

The prevalence of mastitogens causing subclinical mastitis in buffalo across various geographical locations in Sylhet district, Bangladesh. (a) The prevalence (%) of E. coli in different locations, (b) The prevalence (%) of Klebsiella spp. in these areas; (c) Comparison of the prevalence between E. coli and K. pneumoniae across the locations; (d) The overall prevalence (%) of E. coli and K. pneumoniae combined.

Prevalence based on tests and individual quarters

The results of initial screening and PCR testing across four quarters (e.g., left front; LF, left rear; LR, right front; RF, and right rear; RR) for the prevalence of E. coli and Klebsiella spp. are detailed in Table 1. The average positive rates for the MWST and CMT tests were 68.1% and 67.9%, respectively. Both the primary isolation (culture/biochemical) and PCR assays revealed that Klebsiella spp. were more common than E. coli, accounting for 33.1% of the total samples. K. pneumoniae was identified in 42.2% of the Klebsiella spp. positive samples, with the LF quarter showing the highest percentage at 60.4%. E. coli detection was lower at 9.5%, with the RF quarter having the highest PCR positivity at 14.0%. A total of 7.9% of the samples had mixed infections, with LF having the highest rate at 9.4%.

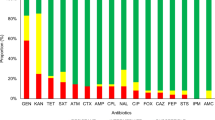

Prevalence of virulence, antimicrobial resistance and ESBL-encoding genes

The prevalence of virulence and AMR genes was notably high in E. coli and Klebsiella spp. isolates obtained from various geographic locations, including Jaintapur, Gowainghat, Kanaighat, Balaganj, and Fenchuganj (Fig. 4). The stx1 gene was detected in 27.4% of the E. coli isolates (Fig. 4a). Surprisingly, stx2 was not identified, indicating that stx1-mediated virulence dominated in these isolates. Among the AMR genes, the aminoglycoside resistance gene aac(3)-iv was the most prevalent, found in 77.4% of the isolates. This was closely followed by the tetracycline resistance gene tetA, which occurred in 76.7% of the isolates. The sulfonamide resistance gene sul1 was present in 57.5% of the isolates, while the streptomycin resistance gene strA was detected in 20.5%. Molecular screening of β-lactamase genes showed a high prevalence of blaTEM (67.1%), but blaOXA and blaSHV were not detected. The ESBL genes, including blaCTX-M-grp1, blaCTX-M-grp2, and blaCTX-M-grp9 showed moderate detection rates, ranging from 8.2 to 52.7%. A similar concerning pattern was observed in Klebsiella spp. isolates (Fig. 4b). Specifically, the AMR genes aac(3)-iv and tetA were identified in 50.0% and 48.6% of the isolates, respectively, while sul1 and strA had detection rates of 37.9% and 25.0%, respectively. The β-lactamase gene blaTEM was the most common, found in 75.7% of the isolates, while blaOXA and blaSHV were not detected. The ESBL genes were also widespread, with blaCTX-M-grp1 in 39.3%, blaCTX-M-grp2 in 47.1%, and blaCTX-M-grp9 in 22.9%. Additionally, the AmpC β-lactamase gene MulticaseDHA was found in 55.5% of E. coli and 51.4% of Klebsiella isolates, indicating its important role in resistance to cephalosporins.

The percent of different genes in between E. coli and K. pneumoniae positive isolates. (a) Combined heatmap and bar diagram illustrating the percentages of virulence, antibiotic resistance, and ESBL-encoding genes in E. coli positive isolates; (b) The percentages of antibiotic resistance and ESBL-encoding genes in K. pneumoniae positive isolates.

The phenotype-genotype correlation was varied in both pathogens. In most cases these antibiotics showed moderate to strong co-resistance patterns (Fig. 6a, b). The correlation analysis of E. coli isolates revealed that certain antibiotics, such as tetracycline, azithromycin, and nalidixic acid, exhibit moderate to strong positive correlations with other antibiotics, including chloramphenicol and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Fig. 6a). Similarly, in K. pneumoniae, a moderate to strong significant phenotypic correlation was observed between streptomycin and tetracycline, chloramphenicol, and nalidixic acid. In most cases, significant genotypic correlations were also evident (Fig. 6b). Additionally, antimicrobial resistance genes, particularly blaCTX-M-grp1, blaCTX-M-grp2, blaTEM, and sul1, show a significant association with resistance phenotypes in E. coli. Some of these correlations are statistically significant (p < 0.05 to p < 0.001).

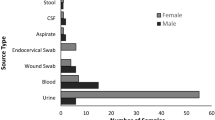

Antimicrobial susceptibility profiling

The AST profiles of 140 K. pneumoniae isolates and 146 E. coli isolates are presented in Fig. 5a-d. E. coli showed the highest susceptibility to cefoxitin (79.45%), streptomycin (78.77%), ciprofloxacin (78.0%), tetracycline (75.34%), chloramphenicol (71.23%), and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (67.81%). In contrast, significant resistance was observed against ampicillin (82.88%), amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (70.55%), gentamicin (56.85%), and amikacin (56.16%) (Fig. 5a, c). An identical situation was observed with K. pneumoniae, which showed strong sensitivity to cefoxitin (80.0%), ciprofloxacin (77.14%), chloramphenicol (69.29%), tetracycline (68.57%), and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (66.43%). However, significant resistance was noted to ampicillin (84.29%), amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (72.14%), gentamicin (56.43%), and amikacin (57.14%) (Fig. 5b, d).

Polar heatmap and bar diagram representing the antibiogram profiles of E. coli and K. pneumoniae isolates from subclinical mastitis-positive milk samples of buffalo. (a) The sensitive, intermediate, and resistant patterns of E. coli isolates; (b) The sensitive, intermediate, and resistant patterns of K. pneumoniae isolates; (c) The bar diagram showing the percentages (%) of sensitivity, resistance, and intermediate responses to different antimicrobials for E. coli isolates; (d) The bar diagram showing the percentages (%) of sensitivity, resistance, and intermediate responses to different antimicrobials for K. pneumoniae isolates.

Biofilm detection

Biofilm formation was detected using the CRA method and the CVMP assay. The presence of biofilm contributes to antibiotic resistance in both pathogens, potentially leading to the development of MDR, XDR, or PDR strains.

In E. coli-positive isolates, biofilm formation was detected in 69.9% (102/146; 95% CI 61.7–77.2) using the CRA plate method, whereas the CVMP assay identified biofilm formation in 83.6% (122/146; 95% CI 76.5–89.2). Among biofilm-producing isolates detected by the CVMP method, 37.67% were strong producers, followed by 30.14% weak and 15.78% moderate producers. In K. pneumoniae-positive isolates, biofilm formation was detected in 62.1% (87/140; 95% CI 53.6–70.2) using the CRA plate method, whereas the CVMP assay detected biofilm in 75.7% (106/140; 95% CI 67.8–82.6). Among biofilm-producing isolates identified via CVMP, 42.14% were strong producers, followed by 27.86% moderate and 5.71% weak producers (Fig. 6c).

The overall phenotype-genotype correlation of E. coli (a) and K. pneumoniae (b) positive isolates. Biofilm production was represented as a percentage (%) using a radar map (c). The figures (a, b) were created using RStudio (R 4.3.3) with the Metan package, while the radar map was generated using Origin 2024b.

MAR index, MDR and XDR patterns of the screened bacterial isolates

A total of 140 K. pneumoniae isolates and 146 E. coli isolates were analyzed for MDR and multiple antimicrobial resistance index (MARI) (Table 2). Among E. coli isolates, 31.5% (46/146) were classified as MDR, with 8.9% (13/146) potentially showing XDR characteristics, and the average MARI was 0.62. In Klebsiella spp., 39.3% (55/140) of the strains were MDR, with 12.86% (18/140) possibly exhibiting XDR, and the average MARI was 0.66. The highest MARI for Klebsiella spp. was 0.92, indicating resistance to 12 of the 13 antibiotics tested, while E. coli showed a MARI of 0.85. The dominant resistance genes in both species included aac(3)-iv, tetA, and sul1 (Table 2).

Discussion

Subclinical mastitis (SCM) in swamp buffaloes is a significant concern in dairy farming, as it reduces milk production and quality without visible symptoms, leading to economic losses. It also serves as a reservoir for antimicrobial-resistant pathogens, such as E. coli and Klebsiella spp., complicating treatment. Effective detection and management are essential for improving dairy productivity and ensuring food safety. This study therefore thoroughly examined SCM in buffaloes in the Sylhet district of Bangladesh, concentrating primarily on the isolation and identification of bacterial pathogens, namely, E. coli and Klebsiella spp., and their prevalence. The study also revealed that the prevalence of SCM was significantly higher at the animal than quarter level. The findings of this research on the prevalence of SCM at the animal level (80.8%) closely correspond with those of earlier investigations in Bangladesh and Pakistan (81.6% and 62.2% respectively)10,50. However, these rates are significantly higher than those reported in other studies from Bangladesh (51.5%), India (26.20%) and the Philippines (42.76%)13,51,52. The findings of this research on the prevalence of SCM at the animal level (80.8%) closely correspond with those of earlier investigations in Bangladesh and Pakistan (81.6% and 62.2% respectively). Additionally, they exceed the 64.92% prevalence reported in another investigation of bovine SCM in the Sylhet district of Bangladesh36. The quarter-level prevalence of SCM in this investigation closely aligns with the findings reported in studies from India (45.8–61.6%) and Pakistan (68.63%)52,53. The prevalence is markedly higher than study noted (19.3%) in Chitwan, Nepal, underscoring the regional variability in SCM prevalence51,54. The higher animal-level prevalence of SCM compared to quarter-level prevalence is due to a single SCM-positive quarter designating the entire buffalo as SCM positive51. SCM incidence varies by country and is influenced by factors such as hygiene practices, milking techniques, lactation stage, and genetics55,56.

Among the different upazilas in Sylhet district, the highest prevalence of E. coli and Klebsiella was detected in Gowainghat. The prevalence of Klebsiella spp. was the highest (80%) in another study in this region57 which indicates the overall burden of Klebsiella in this region comparatively higher than other region of Sylhet. This may be attributed to environmental factors such as frequent flooding, wetland conditions, and high moisture content, which can facilitate bacterial persistence and transmission. K. pneumoniae thrives in moist environments, and the waterlogged soil, stagnant water, and frequent human-animal interactions in these areas may create conditions favorable for its survival and spread57,58.

Conversely, the low prevalence of K. pneumoniae in Balaganj and Fenchuganj suggests a lower bacterial load or reduced environmental reservoirs for its transmission. Tanni et al.57 also found comparatively lower prevalence of Klebsiella on this region. These regions may have better drainage systems, lower humidity, or reduced contamination sources, which limit bacterial survival and dissemination.

The prevalence of E. coli and K. pneumoniae varied across seasons by the pathogen fluctuations over different quarters likely influenced by climatic changes, rainfall patterns, and human activities. Due to increased waterborne transmission, monsoon seasons may contribute to higher bacterial spread, while drier months limit bacterial persistence in the environment. Hence, environmental dynamics play a key role in bacterial prevalence across different timeframes.

The prevalence of E. coli was noticeably greater than that reported in previous study in Nepal59. The variability in SCM prevalence may result from differences in geography, climate, housing systems, milking practices, udder cleanliness, hygiene protocols, and biosecurity awareness among livestock owners60. In this study, the prevalence of E. coli was slightly greater than that of Klebsiella spp., which is consistent with the findings of another study from a health perspective61.

The prevalence of E. coli observed aligns closely with previous findings from studies in western Chitwan and Egypt, where 14% and 15.4% of buffaloes were reported to be affected by E. coli59,62. However, these results contrast significantly with studies from Nineveh Governorate, Iraq (42%) and coastal regions of Bangladesh (25%)17,18. For Klebsiella spp., the prevalence in the current study notably higher than those reported in an Indian study, which reported a prevalence of 9.1%63. These discrepancies highlight the variability in bacterial prevalence across different geographical regions. In addition, the LF quarter presented the highest prevalence of SCM caused by K. pneumoniae, which contradicts the findings of other studies in Nepal, where the LF quarter presented the highest prevalence of SCM caused by E. coli. However, the findings of these studies are consistent with the findings of our study in the case of mixed infections (E. coli and Klebsiella spp.) 59,64. The high prevalence in the forequarters (e.g., LF and RF) could be due to the spread of infection via the milker’s hand. Usually, milking is performed by hand, and since the LF quarter is milked first in most instances, that forequarter has greater chances of becoming infected. This might have led to the higher prevalence of CMT in the left forequarter59. Another study conducted in the Doaba region of Punjab, India, found that the LH quarters were more affected, which contrasts with the findings of our study64.

Moreover, AMR in K. pneumoniae and E. coli from mastitic milk is mediated by the production of β-lactamases (ESBLs and carbapenemases), efflux pumps, and target site changes, leading to MDR and XDR strains65,66. Plasmid-mediated genes (tetA, aac(3)-iv, blaCTX-M, mcr-1) facilitate horizontal gene transfer, imparting resistance to tetracyclines, aminoglycosides, β-lactams, and colistin67,68. Geographical variations in resistance are due to genetic mobility, antibiotic selective pressure, and environmental determinants, highlighting the global spread of AMR69. However, stx1 was detected in 27.4% of the E. coli isolates, whereas stx2 was noticeably absent. This finding is consistent with the results of another study in Iraq, where only one isolate of E. coli possessed the stx1 gene (4.8%), and none of the isolates had the stx2 gene17. However, the findings of the present study are much greater than those of another study in the coastal area of Bangladesh, where the stx1 and stx2 genes were 2.6% and 1.3%, respectively18. The results of this study sharply contrast with those of a previous investigation conducted in migratory and captive wild birds in Bangladesh, where stx2 was found in 12% of E. coli isolates, while stx1 was not detected at all70. The differences in the prevalence of stx1 and stx2 across regions may be attributed to variations in their ecological niches, genetic diversity, and the mobility of stx-encoding prophages. Additionally, factors like host reservoirs and environmental conditions could help explain these discrepancies. For instance, while stx1 is more commonly linked to specific animal reservoirs, stx2 is often associated with more severe human disease due to its higher toxicity and broader host range, influencing its distribution patterns in different regions71,72. The most prevalent AMR genes, tetA and aac(3)-iv, were identified in several other studies, supporting the findings of the present study. In this study, tetA and aac(3)-iv were the most frequently detected AMR genes in E. coli (76.7% and 77.4%, respectively) and Klebsiella spp. (48.6% and 50%, respectively)73,74,75,76. The genes tetA and aac(3)-iv are most frequently identified in E. coli and Klebsiella spp. because of their strong association with mobile genetic elements such as plasmids, facilitating their horizontal transfer, and their role in resistance to commonly used antibiotics such as tetracyclines and aminoglycosides76,77,78. The genes sul1 and strA are less commonly detected than tetA and aac(3)-iv are, likely due to their association with resistance to sulfonamides and streptomycin, antibiotics with reduced usage in contemporary clinical and agricultural settings, leading to decreased selective pressure and lower prevalence. In contrast, β-lactamase genes, particularly blaTEM, presented high prevalence rates in this study, with 67.1% in E. coli and 75.7% in Klebsiella spp., which aligns partially with findings from Barcelona (71.93%) and Mexico (96%) in Klebsiella spp. and from Bangladesh (60.7%)36, Iraq (81%) and Indonesia (77.78%) in E. coli, reflecting regional and antibiotic usage variations42,76,78,79. The prevalence of Klebsiella spp. in this study is slightly higher than that reported in another study conducted in Bangladesh, which found a prevalence of 42.5%36. Furthermore, the prevalence of blaCTX-M-grp2 was noticeably high in both E. coli (52.7%) and Klebsiella spp. (47.1%) among the blaCTX-M gene variants (blaCTX-M-grp1, blaCTX-M-grp2, and blaCTX-M-grp9) examined in this study. This contrasts sharply with findings from Pakistan, where blaCTX-M-grp1 was the most prevalent gene, detected in 56.1% of E. coli and 41.2% of Klebsiella spp., whereas blaCTX-M-grp2 and blaCTX-M-grp9 showed minimal occurrence (0–2.9%)80. However, the detection of blaCTX-M-grp2 in 65.22% of E. coli isolates in the Philippines and 44.8% of Klebsiella spp. isolates in Brazil aligns closely with the results of this study81,82. In addition, the prevalence of blaCTX-M-grp1, and blaCTX-M-grp2 in another SCM study in Bangladesh is somewhat lower than the present study findings36. The variation in the distribution of blaCTX-M-grp1, blaCTX-M-grp2, and blaCTX-M-grp9 across geographic regions may stem from differences in genetic mobility, plasmid associations, host and geographic dissemination, selective pressures exerted by antibiotic use, and regional variations in CTX-M variants 80,81. Additionally, the AmpC β-lactamase gene MulticaseDHA was detected in both E. coli (55.5%) and Klebsiella spp. (51.4%), whereas MulticaseACC and MulticaseMOX variants were entirely absent, a finding that is consistent with previous research on bovine subclinical mastitis (SCM) in Banglades36. These observations underscore the complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors shaping the distribution of resistance genes in diverse settings.

Moreover, cefoxitin exhibited the highest sensitivity to the isolates of both E. coli and Klebsiella spp. in this study, a finding that sharply contrasts with previous reports from Canada and Bangladesh, where cefoxitin demonstrated 100% resistance to E. coli and 68.6% resistance to K. pneumoniae83. Ciprofloxacin was highly effective, with susceptibility rates of 78% in E. coli and 77.14% in Klebsiella spp., which aligns with some SCM-related studies in Bangladesh36 and Nepal59. Similarly, tetracycline also demonstrated noticeable sensitivity against E. coli (75.34%) and Klebsiella spp. (68.57%), which is consistent with findings from Nepal84, where tetracycline was 100% effective against E. coli and exhibited minimal resistance (19.9%) to K. pneumoniae in the United States85. Tetracycline also found completely (100%) resistant to E. coli and Klebsiella spp. in Bangladesh which is fully contradictory to the present study findings36. Streptomycin resulted in 78.77% susceptibility in E. coli, which is close to the 85% susceptibility reported in Ethiopia86. Sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim exhibited moderate effectiveness against E. coli (67.81%) and Klebsiella spp. (66.43%), closely aligning with a study in Bangladesh reporting 87.5% susceptibility70. Furthermore, chloramphenicol displayed high sensitivity to E. coli (83%) and Klebsiella spp. (51%) in Jaipur, India, which is consistent with the results of this study87. In contrast, E. coli and Klebsiella spp. presented high resistance rates to ampicillin and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and moderate resistance rates to gentamicin and amikacin in this study. These results are in agreement with studies conducted in Egypt, where E. coli presented 80%, 60%, and 50% resistance rates to amikacin, ampicillin, and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, respectively 88. Similarly, Klebsiella spp. isolates were found to be completely resistant to ampicillin and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (100%), whereas gentamicin resistance was observed in 50% of the isolates89. These findings revealed an alarming trend of resistance to commonly used antibiotics, with increasing challenges for infection therapy involving these pathogens.

The MDR 46 (31.5%), and possibly XDR 13 (8.9%) of the E. coli isolates detected in this study are closely aligned to a previous study reporting 79 (30.3%) MDR and 22 (8.4%) XDR E. coli isolates90, but much lower than another study in Bangladesh that found 98% MDR and 16% XDR91. Among 140 K. pneumoniae isolates, 55 (39.3%) were MDR, and 18 (12.86%) were possibly XDR, aligning with another study reporting 75 (37.5%) MDR and 25 (12.5%) XDR isolates90. However, this study’s results were notably lower than other studies in Bangladesh that reported 87% MDR and 22.73% XDR92,93. The MDR prevalence in E. coli here contrasts with a study in Nepal, where 78% were MDR, but the XDR prevalence of 7% is similar to our findings94. Likewise, the MDR prevalence in K. pneumoniae differed from a study conducted in Iran, although the XDR prevalence of 13% was similar95. The MAR index (MARI) for E. coli (0.62) aligns with findings from Bangladesh, where 96% of isolates had a MAR index > 0.3, and 64% exceeded 0.591. The MARI for K. pneumoniae (0.66) is also consistent with a Nigerian study reporting a MARI value of 0.7996.

Most biofilm-producing isolates exhibited a high likelihood of developing MDR or XDR. In both pathogens, strong to moderate biofilm producers were predominantly associated with MDR and XDR profiles. Furthermore, Biofilm in E. coli is controlled by lasR, lecA, and pelA, affecting quorum sensing, lectin adhesion, and extracellular matrix production, respectively, for the promotion of bacterial persistence and antibiotic resistance97. In K. pneumoniae, mrkA and mrkD are essential for type 3 fimbriae-mediated adhesion and biofilm maturation, where they promote the colonization of host surfaces and medical devices by bacteria98. These biofilm-related genes are responsible for immune evasion and enhanced antimicrobial tolerance, thereby making infections more difficult to eradicate.

These results highlight regional differences in resistance patterns while reflecting global trends. The variation in MDR and XDR prevalence among different organisms may result from factors such as intrinsic resistance mechanisms, acquired resistance, antibiotic exposure, gene mobility, environmental influences, virulence, biofilm formation, and potential diagnostic or surveillance biases99,100,101. Limitations of this study include the reliance on conventional techniques like PCR, rather than more advanced methods such as whole-genome sequencing.

Conclusion

The study highlights a high prevalence of SCM, with significant proportions of E. coli and K. pneumoniae exhibiting MDR and XDR, along with an alarming levels of virulence genes (stx1) and AMR genes (aac(3)-iv, tetA, and β-lactamase genes such as blaTEM and blaCTX-M-grp1). The detection of resistance to critical antimicrobials, including aminoglycosides and β-lactams, and the prevalence of MDR/XDR strains draw attention to the growing threat posed by AMR in dairy production systems. Therefore, improved surveillance, sensible antibiotic use, and robust biosecurity measures should be considered to mitigate the spread of resistant pathogens and safeguard animal and public health.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study can be obtained from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Change history

23 June 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02374-4

References

Arora, S., Sindhu, J. S. & Khetra, Y. Buffalo milk. Encyclopedia of Dairy Sciences: Third edition 5, 784–796 (2021).

Preethirani, P. L. et al. Isolation, biochemical and molecular identification, and in-vitro antimicrobial resistance patterns of bacteria isolated from bubaline subclinical mastitis in South India. PLoS One 10, e0142717 (2015).

Hamid, M., Siddiky, M., Rahman, M. & Hossain, K. Scopes and opportunities of buffalo farming in Bangladesh: A review. SAARC J. Agric. 14, 63–77 (2017).

Uddin, M., Mintoo, A., Awal, T., Kondo, M. & Kabir, A. Characterization of buffalo milk production system in Bangladesh. Bangladesh J. Anim. Sci. 45, 69–77 (2016).

Khan, S. et al. Effect of pregnancy on lactation milk value in dairy buffaloes. Asian-Australas J. Anim. Sci. 21, 523–531 (2008).

Habib, M. R. et al. Dairy buffalo production scenario in Bangladesh: a review. Asian J. Med. Biol. Res. 3, 305–316 (2017).

Krishnamoorthy, P., Goudar, A. L., Suresh, K. P. & Roy, P. Global and countrywide prevalence of subclinical and clinical mastitis in dairy cattle and buffaloes by systematic review and meta-analysis. Res. Vet. Sci. 136, 561–586 (2021).

Sarker, S. C., Parvin, M. S., Rahman, A. K. M. A. & Islam, M. T. Prevalence and risk factors of subclinical mastitis in lactating dairy cows in north and south regions of Bangladesh. Trop. Anim. Health. Prod. 45, 1171–1176 (2013).

Hoque, M. N. et al. Antibiogram and virulence profiling reveals multidrug resistant Staphylococcus aureus as the predominant aetiology of subclinical mastitis in riverine buffaloes. Vet. Med. Sci. 8, 2631–2645 (2022).

Singha, S. et al. Incidence, etiology, and risk factors of clinical mastitis in dairy cows under semi-tropical circumstances in Chattogram, Bangladesh. Animals 11, 2255 (2021).

Bennedsgaard, T. W., Enevoldsen, C., Thamsborg, S. M. & Vaarst, M. Effect of mastitis treatment and somatic cell counts on milk yield in Danish organic dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 86, 3174–3183 (2003).

Kader, M., Samad, M. & Saha, S. Influence of host level factors on prevalence and economics of subclinical mastitis in dairy milch cows in Bangladesh. Indian J. Dairy Sci. 56, 235-240 (2003).

Salvador, R. T., Beltran, J. M. C., Abes, N. S., Gutierrez, C. A. & Mingala, C. N. Short communication: Prevalence and risk factors of subclinical mastitis as determined by the California Mastitis Test in water buffaloes (Bubalis bubalis) in Nueva Ecija, Philippines. J. Dairy Sci. 95, 1363–1366 (2012).

Shafiq, M. et al. Coexistence of bla NDM-5 and tet(X4) in international high-risk Escherichia coli clone ST648 of human origin in China. Front. Microbiol. 13, 1031688 (2022).

Algammal, A. M. et al. Resistance profiles, virulence and antimicrobial resistance genes of XDR S Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium. AMB Express 13, 110 (2023).

Zaatout, N. An overview on mastitis-associated Escherichia coli: Pathogenicity, host immunity and the use of alternative therapies. Microbiol. Res. 256, 126960 (2022).

Abdlla, Y. A., Sheet, O. H., Alsanjary, R. A., Plötz, M. & Abdulmawjood, A. A. Isolation and Identification of Escherichia coli from Buffalo’s Milk using PCR Technique in Nineveh Governorate. Egypt. J. Vet. Sci. 55, 1881–1887 (2024).

Mannan, M. S. et al. Prevalence of shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in buffaloes on smallholdings in coastal area in Bangladesh. Thai J. Vet. Med. 51, 691–696 (2021).

Yadav, S. et al. Prevalence, extended-spectrum β-lactamase and biofilm production ability of Escherichia coli isolated from buffalo mastitis. Indian J. Anim. Sci. 93, 1145–1149 (2023).

Algammal, A. M. et al. Virulence determinant and antimicrobial resistance traits of emerging MDR Shiga toxigenic E. coli in diarrheic dogs. AMB Express 12, 1–12 (2022).

Algammal, A. M. et al. Genes encoding the virulence and the antimicrobial resistance in enterotoxigenic and Shiga-Toxigenic E. coli isolated from diarrheic calves. Toxins (Basel) 12, 383 (2020).

Ombarak, R. A., Zayda, M. G., Awasthi, S. P., Hinenoya, A. & Yamasaki, S. Serotypes, pathogenic potential, and antimicrobial resistance of Escherichia coli Isolated from subclinical bovine mastitis milk samples in Egypt. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 72, 337–339 (2019).

Massé, J., Dufour, S. & Archambault, M. Characterization of Klebsiella isolates obtained from clinical mastitis cases in dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 103, 3392–3400 (2020).

Taniguchi, T. et al. A 1-year investigation of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from bovine mastitis at a large-scale dairy farm in Japan. Microb. Drug Resist. 27, 1450–1454 (2021).

Gelalcha, B. D. & Kerro Dego, O. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases producing enterobacteriaceae in the USA dairy cattle farms and implications for public health. Antibiotics (Basel) 11, 1313 (2022).

Elashkar, E. et al. Novel silver nanoparticle-based biomaterials for combating Klebsiella pneumoniae biofilms. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1507274 (2024).

Pieterse, R. & Todorov, S. D. Bacteriocins—exploring alternatives to antibiotics in mastitis treatment. Braz. J. Microbiol. 41, 542–562 (2010).

Momtaz, H., Safarpoor Dehkordi, F., Taktaz, T., Rezvani, A. & Yarali, S. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from bovine mastitic milk: Serogroups, virulence factors, and antibiotic resistance properties. Sci. World J. 2012, 618709 (2012).

Stephan, R. et al. Prevalence and characteristics of Shiga Toxin-producing Escherichia coli in Swiss raw milk cheeses collected at producer level. J. Dairy Sci. 91, 2561–2565 (2008).

Oliver, S. P., Murinda, S. E. & Jayarao, B. M. Impact of antibiotic use in adult dairy cows on antimicrobial resistance of veterinary and human pathogens: a comprehensive review. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 8, 337–355 (2011).

Pitkälä, A., Salmikivi, L., Bredbacka, P., Myllyniemi, A. L. & Koskinen, M. T. Comparison of tests for detection of beta-lactamase-producing staphylococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45, 2031–2033 (2007).

Erskine, R. J., Walker, R. D., Bolin, C. A., Bartlett, P. C. & White, D. G. Trends in antibacterial susceptibility of mastitis pathogens during a seven-year period. J. Dairy Sci. 85, 1111–1118 (2002).

Naser, J. Al et al. Exploring of spectrum beta lactamase producing multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serovars in goat meat markets of Bangladesh. Vet. Anim. Sci. 25, 100367 (2024).

Thrusfield, M. et al. Veterinary epidemiology: Fourth edition. Veterinary Epidemiology: Fourth Edition 1–861 (2017) https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118280249.

NMC. National Mastitis Council Procedures for Collecting Milk Samples. National Mastitis Council (NMC) (2004).

Emon, A. Al et al. Prevalence, antimicrobial susceptibility profiles and resistant gene identification of bovine subclinical mastitis pathogens in Bangladesh. Heliyon 10, e34567 (2024).

Hoque, M. N., Das, Z. C., Talukder, A. K., Alam, M. S. & Rahman, A. N. M. A. Different screening tests and milk somatic cell count for the prevalence of subclinical bovine mastitis in Bangladesh. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 47, 79–86 (2015).

Farabi, A. Al et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species isolated from subclinical bovine mastitis. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. (2024) https://doi.org/10.1089/FPD.2024.0097.

Mia, M. P. et al. Prevalence and consequences of bovine subclinical mastitis in hill tract areas of the Chattogram division, Bangladesh. J. Adv. Biotechnol. Exp. Therap. 8, 163–181 (2025).

Basavaraju, M., Gunashree, B. S., Basavaraju, M. & Gunashree, B. S. Escherichia coli: An overview of main characteristics. Escherichia coli - Old New Insights https://doi.org/10.5772/INTECHOPEN.105508 (2022).

Smith, I. Veterinary microbiology and microbial disease. Vet. J. 165, 333 (2003).

Widodo, A. et al. Antimicrobial resistance characteristics of multidrug resistance and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing Escherichia coli from several dairy farms in Probolinggo, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 24, 215–221 (2023).

Sathyavathy, K. & Madhusudhan, B. K. Isolation, identification, speciation and antibiotic susceptibility pattern of Klebsiella species among various clinical samples at Tertiary Care Hospital. J. Pharm. Res. Int. 33, 78–87 (2021).

Aldous, W. K., Pounder, J. I., Cloud, J. L. & Woods, G. L. Comparison of six methods of extracting mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA from processed sputum for testing by quantitative real-time PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43, 2471 (2005).

Freeman, D. J., Falkiner, F. R. & Keane, C. T. New method for detecting slime production by coagulase negative staphylococci. J. Clin. Pathol. 42, 872 (1989).

Kouidhi, B., Zmantar, T., Hentati, H. & Bakhrouf, A. Cell surface hydrophobicity, biofilm formation, adhesives properties and molecular detection of adhesins genes in Staphylococcus aureus associated to dental caries. Microb. Pathog. 49, 14–22 (2010).

CLSI. CLSI M100-ED33: 2023 Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 33rd Edition. Clsi 402 (2023).

Hoque, M. F. et al. Prevalence and antibiotic susceptibility profile of Staphylococcus aureus in clinical and subclinical mastitis milk samples. Bangladesh J. Vet. Med. 21, 27-37 (2023).

Magiorakos, A. P. et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: An international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18, 268–281 (2012).

Shahzad, M. A. et al. Virulence and resistance profiling of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from subclinical bovine mastitis in the Pakistani Pothohar region. Sci. Rep. 14, 1–10 (2024).

Singha, S. et al. The prevalence and risk factors of subclinical mastitis in water buffalo (Bubalis bubalis) in Bangladesh. Res. Vet. Sci. 158, 17–25 (2023).

Srinivasan, P. et al. Prevalence and etiology of subclinical mastitis among buffaloes (Bubalus bubalus) in Namakkal, India. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 16, 1776–1780 (2013).

Javed, S. et al. Epidemiology and molecular characterization of Staphylococcus aureus causing bovine mastitis in water buffaloes from the Hazara division of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. PLoS One 17, e0268152 (2022).

Tiwari, B. B. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of staphylococcal subclinical mastitis in dairy animals of Chitwan, Nepal. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 16, 1392–1403 (2022).

Khasanah, H., Setyawan, H. B., Yulianto, R. & Widianingrum, D. C. Subclinical mastitis: Prevalence and risk factors in dairy cows in East Java, Indonesia. Vet. World 14, 2102–2108 (2021).

Ranasinghe, R. M. S. B. K., Deshapriya, R. M. C., Abeygunawardana, D. I., Rahularaj, R. & Dematawewa, C. M. B. Subclinical mastitis in dairy cows in major milk-producing areas of Sri Lanka: Prevalence, associated risk factors, and effects on reproduction. J. Dairy Sci. 104, 12900–12911 (2021).

Tanni, F. Y. et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing Klebsiella spp. in poultry meat. Heliyon 11, e41748 (2025).

Liza, N. A. et al. Molecular epidemiology and antimicrobial resistance of extended‐spectrum β ‐lactamase (ESBL)‐producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Retail Cattle Meat. Vet. Med. Int. 2024, 3952504. (2024).

Bhandari, S. et al. Prevalence and risk factors for multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli isolated from subclinical mastitis in the western Chitwan region of Nepal. J. Dairy Sci. 104, 12765–12772 (2021).

Bushra, A. et al. Biosecurity, health and disease management practices among the dairy farms in five districts of Bangladesh. Prev. Vet. Med. 225, 106142 (2024).

Ramatla, T. et al. “One Health” perspective on prevalence of co-existing extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 22, 1–17 (2023).

Ahmed, W. et al. Characterization of enterococci- and ESBL-producing Escherichia coli Isolated from milk of bovides with mastitis in Egypt. Pathogens 10, 1–15 (2021).

Keshamoni Ramesh1, L. K. A. G. and S. B. Diagnosis of sub clinical mastitis in buffaloes. Acta Sci. Vet. Sci. 4, 22–26 (2022).

Khanal, T. & Pandit, A. Assessment of sub-clinical mastitis and its associated risk factors in dairy livestock of Lamjung, Nepal. Int. J. Infect. Microbiol. 2, 49–54 (2013).

Sharahi, J. Y., Hashemi, A., Ardebili, A. & Davoudabadi, S. Molecular characteristics of antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae strains isolated from hospitalized patients in Tehran, Iran. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 20, 1–14 (2021).

Nery Garcia, B. L. et al. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and other antimicrobial-resistant gram-negative pathogens isolated from bovine mastitis: A one health perspective. Antibiotics 13, 391 (2024).

Rozwandowicz, M. et al. Plasmids carrying antimicrobial resistance genes in Enterobacteriaceae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 73, 1121–1137 (2018).

Jian, Z. et al. Antibiotic resistance genes in bacteria: Occurrence, spread, and control. J. Basic Microbiol. 61, 1049–1070 (2021).

Larsson, D. G. J. & Flach, C. F. Antibiotic resistance in the environment. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 257 (2021).

Rahman, A. et al. Identification of virulence genes and multidrug resistance in Shiga-toxin producing Escherichia coli (STEC) from migratory and captive wild birds. Pak. Vet. J. 44, 1120-1130 (2024).

Sui, X. et al. Characteristics of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli circulating in asymptomatic food handlers. Toxins (Basel) 15, 640 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. A comprehensive review on Shiga toxin subtypes and their niche-related distribution characteristics in Shiga-Toxin-producing E. coli and other bacterial hosts. Microorganisms 12, 687 (2024).

Karim, M. R., Zakaria, Z., Hassan, L., Mohd Faiz, N. & Ahmad, N. I. Antimicrobial resistance profiles and co-existence of multiple antimicrobial resistance Genes in mcr-harbouring colistin-resistant enterobacteriaceae isolates recovered from poultry and poultry meats in Malaysia. Antibiotics (Basel) 12, 1060 (2023).

Plattner, M., Gysin, M., Haldimann, K., Becker, K. & Hobbie, S. N. Epidemiologic, phenotypic, and structural characterization of aminoglycoside-resistance gene aac(3)-IV. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 1–11 (2020).

Altayb, H. N. et al. Co-occurrence of β-lactam and aminoglycoside resistance determinants among clinical and environmental isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli: A genomic approach. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 15, 1011 (2022).

Paniagua-Contreras, G. L. et al. Extensive expression of the virulome related to antibiotic genotyping in nosocomial strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 14754 (2023).

Haley, B. J., Kim, S. W., Salaheen, S., Hovingh, E. & Van Kessel, J. A. S. Virulome and genome analyses identify associations between antimicrobial resistance genes and virulence factors in highly drug-resistant Escherichia coli isolated from veal calves. PLoS One 17, e0265445 (2022).

Ballén, V. et al. Antibiotic resistance and virulence profiles of Klebsiella pneumoniae strains isolated from different clinical sources. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 11, 738223 (2021).

Pishtiwan, A. H. & Khadija, K. M. Prevalence of blaTEM, blaSHV, and blaCTX-M genes among ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli isolated from thalassemia patients in erbil, Iraq. Mediterr. J. Hematol. Infect. Dis. 11, e2019041 (2019).

Ejaz, H. et al. Molecular analysis of blaSHV, blaTEM, and blaCTX-M in extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae recovered from fecal specimens of animals. PLoS One 16, e0245126 (2021).

Gundran, R. S. et al. Prevalence and distribution of blaCTX-M, blaSHV, blaTEM genes in extended- spectrum β-lactamase- producing E. coli isolates from broiler farms in the Philippines. BMC Vet. Res. 15, 227 (2019).

Do Carmo Filho, J. R. et al. Prevalence and genetic characterization of blaCTX-M among Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates collected in an intensive care unit in Brazil. J. Chemother. 20, 600–603 (2008).

Mataseje, L. F. et al. Characterization of cefoxitin-resistant Escherichia coli isolates from recreational beaches and private drinking water in Canada between 2004 and 2006. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53, 3126–3130 (2009).

Aavash, K., Sajita, G., Narayan, G. C. & Kumar, S. A. Prevalence of subclinical mastitis and antibiogram of Escherichia coli in cow milk of Western Chitwan. J. Vet. Med. Res. 10, 1–7 (2023).

Sanchez, G. V. et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae antimicrobial drug resistance, United States, 1998–2010. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 19, 133–136 (2013).

Sarba, E. J. et al. Identification and antimicrobial susceptibility profile of Escherichia coli isolated from backyard chicken in and around ambo, Central Ethiopia. BMC Vet. Res. 15, 1–8 (2019).

Sood, S. Chloramphenicol: A potent armament against multi-drug resistant (MDR) gram negative bacilli? J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 10, DC01 (2016).

Youssif Ismail Badr, N. H., Hafiz, N. M., Halawa, M. A. & Aziz, H. M. Genes conferring antimicrobial resistance in cattle with subclinical mastitis. Bulg. J. Vet. Med. 24, 67–85 (2021).

Youssif, N. H., Hafiz, N. M., Halawa, M. A. & Saad, M. Potential risk of antimicrobial resistance related to less common bacteria causing subclinical mastitis in cows. J. Adv. Vet. Res. 13, 222–229 (2023).

Basak, S., Singh, P. & Rajurkar, M. Multidrug resistant and extensively drug resistant bacteria: A study. J. Pathog. 2016, 1–5 (2016).

Jain, P. et al. High prevalence of multiple antibiotic resistance in clinical E. coli isolates from Bangladesh and prediction of molecular resistance determinants using WGS of an XDR isolate. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–13 (2021).

Chakraborty, S. et al. Prevalence, antibiotic susceptibility profiles and ESBL production in Klebsiella pneumoniae and Klebsiella oxytoca among hospitalized patients. Period. Biol. 118, 53-58 (2016).

Kawser, Z. & Shamsuzzaman, S. M. Association of Virulence with Antimicrobial Resistance among Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolated from Hospital Settings in Bangladesh. Int. J. Appl. Basic Med. Res. 12, 123 (2022).

Ansari, S. et al. Community acquired multi-drug resistant clinical isolates of Escherichia coli in a tertiary care center of Nepal. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 4, 15 (2015).

Farhadi, M., Ahanjan, M., Goli, H. R., Haghshenas, M. R. & Gholami, M. High frequency of multidrug-resistant (MDR) Klebsiella pneumoniae harboring several β-lactamase and integron genes collected from several hospitals in the north of Iran. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 20, 70 (2021).

Ogefere, H. & Idoko, M. Multiple antibiotic resistance index of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from clinical specimens in a tertiary hospital in Benin City, Nigeria. J. Med. Biomed. Res. 23, 5–11 (2024).

Sionov, R. V. & Steinberg, D. Targeting the holy triangle of quorum sensing, biofilm formation, and antibiotic resistance in pathogenic bacteria. Microorganisms 10, 1239 (2022).

Li, Y. & Ni, M. Regulation of biofilm formation in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1238482 (2023).

Effah, C. Y., Sun, T., Liu, S. & Wu, Y. Klebsiella pneumoniae: An increasing threat to public health. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 19, 1–9 (2020).

Murray, C. J. et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet 399, 629–655 (2022).

Walker, M. M., Roberts, J. A., Rogers, B. A., Harris, P. N. A. & Sime, F. B. Current and emerging treatment options for multidrug resistant Escherichia coli urosepsis: A review. Antibiotics (Basel) 11, 1821 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely acknowledge the University Grant Commission (UGC) of Bangladesh for providing partial funding for this study (Project Code: UGC-2021-22), which was awarded to Md. Mahfujur Rahman. The authors also acknowledge the Sylhet Agricultural University Research System (SAURES) for facilitating part of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S.R.C.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Investigation, Writing-original draft, Writing- reviewing & editing; H.H.: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Software, Writing-original draft, Writing- reviewing & editing; M.N.R., A.R. & P.K.G.: Methodology, Investigation, Writing-original draft; M.B.U.: Validation, Visualization, Writing- reviewing & editing. M.N.H. & M.M.H.: Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing- reviewing & editing; M.M.R.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Formal analysis, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing-original draft, Writing- reviewing & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained errors in Figure 4, where panel (b) was a duplication of panel (a).

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chowdhury, M.S.R., Hossain, H., Rahman, M.N. et al. Emergence of highly virulent multidrug and extensively drug resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in buffalo subclinical mastitis cases. Sci Rep 15, 11704 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95914-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95914-x

This article is cited by

-

Water buffalo farming, udder health and its dairy production status in Bangladesh: Practices, challenges, and potentialities

Veterinary Research Communications (2025)

-

Antimicrobial resistance profiles and genomic insights of phenotypically extended spectrum β-lactamase-positive Klebsiella pneumoniae from cattle farms

Current Genetics (2025)

-

Prevalence and Antimicrobial Resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolated from Subclinical Mastitis in Selected Pure Dairy Cattle Breeds in Pakistan

Current Microbiology (2025)