Abstract

ERK5 has emerged as a promising therapeutic target in cancer treatment due to its pivotal role in regulating tumor cell proliferation and survival. In this study, we synthesized novel derivatives of 1,4-dialkoxynaphthalene-2-acyl or 2-alkyl-imidazolium salt (NAIMS), assessed their binding affinity with the ERK5 protein through molecular modeling, and evaluated their anti-cancer activity through the ERK5 kinase assay. Based on the MTT assay and qRT-PCR analysis of 21 synthesized NAIMS, the IC50 values for 4c, 4e, and 4k (8.5 μM, 6.8 μM, and 8.9 μM, respectively) and the inhibition rate of the expression of PCNA for 4c, 4e, and 4k (50%, 61.1%, and 70.2% of 5 μM respectively) were chosen for comprehensive biological research. Further analyses including DAPI staining, and flow cytometry confirmed that 4c, 4e, and 4k induced late-stage apoptosis, and triggered cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase of HeLa cells. Moreover, molecular modeling analysis showed that 4e exhibited strong and stable molecular interactions at the ERK5 ATP-binding site. Our results strongly suggest that NAIMS compounds, especially 4e, could serve as novel inhibitors of ERK5, presenting promising lead compound to develop for cancer treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Cancer is a disease in which some of the cells in the body grow uncontrollably and spread to other parts of the body. In recent years, accumulating evidence has underscored the crucial role of ERK5 in the proliferation, tumorigenesis, and survival of multiple types of cancer1,2. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5 (ERK5), encoded by the MAPK7 gene, is a serine/threonine kinase belonging to the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family and plays a significant role in cancer biology3,4. It involves cellular processes such as proliferation, survival, migration, and differentiation5. The involvement of ERK5 in tumor cell proliferation and the regulation of different phases of the cell cycle has been widely researched over the last few years5. Recent studies have reported that ERK5 inhibition increased the proliferation rate and intensified the number of G0/G1 cells in hepatocellular carcinoma via a mechanism involving the upregulation of p27 and p156. Therefore, inhibiting or silencing ERK5 has emerged as a promising target for anticancer therapy.

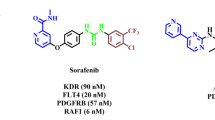

The earliest ERK5 inhibitor, XMD8-92, has been extensively used to investigate the proposed roles of ERK5 kinase activity (Fig. 1)7. XMD8-92 is known for its anticancer properties, particularly against lung and cervical cancers8. However, unexpected paradoxical activation, where ERK5 inhibition paradoxically triggers oncogenic signaling pathways, and off-target effects associated with XMD8-92 have limited its clinical application8,9,10,11,12,13,14. These challenges have driven significant efforts to develop new ERK5 inhibitors with improved selectivity and reduced side effects8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Consequently, new selective ERK5 inhibitors are required to minimize these unwanted effects and to enable further research into the non-catalytic roles of ERK58,9,10,11,12,13,14.

The development of new ERK5 inhibitors holds potential to overcome the limitations of existing compounds and offer novel therapeutic applications in cancer treatment8,9,10,11,12,13,14. This study aims to address these challenges by designing and synthesizing novel ERK5 inhibitors, thereby advancing the therapeutic landscape of ERK5-targeted cancer therapies.

Azole derivatives, such as imidazole and thiazole, are structural components commonly used in marketed drugs, representing important heterocycles that have nitrogen-containing five-membered heterocyclic rings15,16. These distinctive ring structures can readily bind to various enzymes and receptors through a limited number of weak interactions, demonstrating a broad spectrum of biological and pharmacological effects17. Leveraging the characteristics of these azole compounds, we aimed to develop compounds with diverse activities. Hence, we have synthesized new derivatives by connecting a naphthalene ring to the azole derivatives, which could enhance pharmacological activity. In a previous study, naphthalene-2-acyl thiazolium salt derivatives were identified to exhibit activity as advanced glycation end product (AGE) breakers. Additionally, we confirmed the importance of two alkoxy groups at positions 1 and 4 of the naphthalene ring to show effective disruption of the activity AGEs18. Subsequently, we verified the remarkable antifungal activity exhibited by the 1,4-dialkoxynaphthalene-2-acyl imidazolium salt derivatives synthesized through the transformation of thiazole into imidazole19. Furthermore, we developed an improved synthetic method to prepare 1,4-dialkoxynaphthalene-2-alkyl imidazolium salt derivatives and their anticancer activity20.

In our previous report, MHJ-627, a 1,4-diisoamyloxynaphthalene-2-acyl imidazolium salt, exhibited the most potent anti-cancer activity among various derivatives in ERK5 kinase activity screening tests (Fig. 1)21. However, there was a need for new compounds that could increase both ERK5 kinase inhibitory activity and anti-cancer activity. Inspired by the structure of MHJ-627, we synthesized new 1,4-dialkoxynaphthalene-2-acyl or 2-alkyl-imidazolium salt derivatives (NAIMS). Additionally, the structure–activity relationship (SAR) of the synthesized derivatives was investigated by measuring its binding affinity to the ERK5 protein (PDB ID 5O7I). We developed and applied an improved bioactivity evaluation system to assess the anticancer activity through ERK5 inhibition for derivatives that showed good corelated results in SAR analysis. The aim of this study is to provide evidence that NAIMS serves as a potential small molecule for cancer treatment by inhibiting ERK5 kinase activity and to offer insights into the design and synthesis of novel anti-cancer molecules.

Results

Chemistry

Based on the structure of MHJ-627, we synthesized new derivatives with different types of substituents at various positions to identify the essential part of the structure that enhances ERK5 specificity and anticancer activity, namely the pharmacophore. Subsequently, we attempted to synthesize derivatives by introducing substituents at various positions on the imidazole ring of this structure to enhance anticancer activity.

The novel NAIMS derivatives were synthesized through coupling of naphthalene moiety with various imidazole derivatives. Naphthalene moieties, such as 1,4- dialkoxynaphthalene bromide intermediates (1a—1e) were prepared as shown in Fig. 2, which were obtained through a previously reported method19,20. Specifically, the reduction and consecutive acetylation of 1,4-naphthoquinone, followed by the subsequent Fries rearrangement reaction, resulted in the formation of the 4-acetoxy-2-acetyl-1-hydroxynaphthalene intermediate. Subsequently, through the alkylation of this intermediate with alkyl halides and bromination reactions, the 1,4- dialkoxynaphthalen-2-acyl bromides (1a—1d)were synthesized19. Additionally, the 1,4-diisoamylnapthalen-2-alkyl bromide (1e)was synthesized by alkylating 1,4-dihydroxy-2-naphthoic acid to obtain 1,4-diisoamyloxy-2-isoamylnaphthoate, followed by the reduction of this ester intermediate and bromination reaction of the generated alcohol intermediate20.

Synthesis of imidazole derivatives was shown in Fig. 3. N-Alkyl imidazoles (2a—2c) and N-alkyl benzimidazoles (2d—2p)were synthesized from imidazole and benzimidazole, respectively, using a previously reported method16,17. The synthesis involved the reaction of imidazole or benzimidazole derivatives with the corresponding alkyl halides under basic conditions19,20. Meanwhile, new benzimidazole derivatives (2g—2p), with substituents introduced at the position 2 or positions 5 and 6 of benzimidazole, were synthesized using the following method. Initially, benzimidazoles (2g—2 m), with a substituent at position 2, were synthesized by reacting O-phenylenediamine (O-PDA) with corresponding aldehydes or carboxylic acid derivatives. Aldehyde derivatives were most effective when reacted in an open flask under wet DMF conditions22. When using carboxylic acid derivatives, 2-substituted benzimidazoles were synthesized by heating them with O-PDA in a hydrochloric acid solution. 4,5-Dibromobenzene-1,2-diamine and 4,5-diphenylbenzene-1,2-diamine reacted with formic acid by heating under acidic condition to form 5,6-disubstituted benzimidazoles, respectively23. To synthesize N-alkyl-substituted benzimidazoles, each benzimidazole was subjected to an alkylation reaction with 1-bromo-3-methylbutane and KOH in anhydrous DMSO. This process provided 1-isoamyl-2-substituted benzimidazoles (2g—2 m) or 1-isoamyl-5,6-disubstituted benzimidazoles (2n—2p)20.

As shown in Fig. 4, 3a - 3h and 4a - 4c were successfully obtained by refluxing the naphthalene bromide intermediates (1a—1e) and N-alkyl imidazoles (2a—2c) or N-alkyl benzimidazoles (2d—2f.)in acetonitrile (ACN)16,17. Due to the easier synthesis of 2-alkyl NAIMS (4a—4c) compared to 2-acyl NAIMS (3a—3 h), we aimed to synthesize a structure with higher activity that shares the same functional group as MHJ-627 but with an alkylen linker instead of an acyl linker. Therefore, 4d—4 m were successfully obtained by refluxing naphthalene bromide intermediate 1e and benzimidazole derivatives (2g—2p) in ACN, respectively17.

Tables 1 and 2 show the IC50viability and PCNA inhibition rate for 21 synthesized NAIMS. We chose XMD8-92 as a standard reference to compare its activity with our compounds10,13. Determination of IC50 is essential for understanding the pharmacological and biological characteristics of the compounds. The MTT assay is currently the most extensively used method for IC50 measurements. Here, the 21 synthesized NAIMS were assessed via the MTT assay (expressed as IC50values), the optimized cell viability assay, to validate cytotoxicity. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) serves as a marker of cell proliferation and plays a role in cell survival and tumorigenesis24. The downregulation of PCNA expression is observed upon the inhibition or ablation of ERK521. Hence, PCNA emerges as a potential anticancer target. mRNA PCNA expression was determined by quantitative RT-PCR of the Hela cells. The PCNA inhibition rate was calculated by comparing the untreated control group with the group treated with a 10 μM NAIMS. The inhibition of PCNA expression of XMD8-92 and MHJ-627 as the control, with values of 51.4% and 51.6%, respectively21. Inhibition rates were determined using the (100% of DMSO-treated control—% of NAIMS-treated) formula based on the 2−∆∆Cq method. The mRNA levels of the housekeeping gene GAPDH were utilized for normalization, and the relative expression level was analyzed using the 2−∆∆Cq method.

Table 1 presented imidazolium or benzimidazolium salt derivatives with an acyl linker at position 2 of the naphthalene ring. The NAIMS 3a—3h, which possess an acyl linker, exhibited strong inhibitory potential against the Hela cell line, with IC50 values ranging from 10.1 μM to 17.0 μM. NAIMS with relatively longer isoamyloxy or n-octoxy groups at positions 1 and 4 of the naphthalene ring showed a tendency to better suppress overall PCNA mRNA expression compared to those substituted with methoxy or isopropoxy groups, and imidazolium salts exhibited a more stable PCNA inhibition rate than benzimidazolium salts.

In particular, the imidazolium salt 3c with isoamyloxy and benzyl groups exhibited a highly impressive PCNA inhibition rate of 71.7%, whereas the benzimidazolium salt 3e with the same isoamyloxy and benzyl groups showed no PCNA inhibition.

Table 2 presents benzimidazolium salt derivatives with isoamyloxy groups at positions 1 and 4 of the naphthalene ring and an alkylene linker at position 2. Among these, 4j, which contains a methoxyethyl group on the benzimidazole ring, exhibited the most potent IC50 value of 5.7 μM and demonstrated a moderate PCNA inhibition rate of 57.4%. Additionally, 4k, bearing two methyl groups on the benzimidazole ring, showed a high PCNA inhibition rate of 70.2%, comparable to 3c in Table 1, while also exhibiting an IC50 value of 8.9 μM, which was superior to that of 3c.

While substitutions at positions 5 and 6 of the benzimidazole ring appear to influence IC50 values and PCNA inhibition rates, the trend is not strictly dependent on substituent size. For instance, 4k (X = Me) showed the highest PCNA inhibition rate (70.2%), while 4c (X = H) exhibited a moderate inhibition rate of 50.0%. Interestingly, 4m (X = Br), despite having a larger substituent, displayed a PCNA inhibition rate of 57.0%, suggesting that steric factors alone may not fully explain variations in activity.

These observations indicate that beyond steric factors, electronic properties and specific interactions within the ERK5 binding site may contribute significantly to inhibitory activity. Notably, smaller substituents such as methyl (4k) and methoxyethyl (4j) were associated with relatively higher inhibition rates, which may be attributed to a favorable interaction within the binding pocket. However, the presence of larger substituents such as bromine (4m) did not always result in lower inhibition rates, implying that additional factors, such as hydrophobic interactions and substituent-induced conformational effects, may play a role.

Furthermore, when alkyl groups such as methyl, isopropyl, and methoxyethyl were introduced at position 2 of the benzimidazole ring, relatively higher PCNA inhibition rates were observed compared to aryl groups like phenyl, 4-methoxyphenyl, and 4-fluorophenyl. This suggests that the electronic and steric effects of substituents at this position influence the biological activity, potentially affecting the optimal alignment within the ERK5 binding pocket.

Table 3 presents the docking results and various energy components for 21 NAIMS compounds bound to ERK5 (PDB ID 5O7I). These energy components include Potential Energy, RMS Gradient, Bond Energy, Angle Energy, Dihedral Energy, van der Waals Energy, and Electrostatic Energy, all measured in kcal/mol. These values provide insights into the interactions and affinities between the ligands and receptors.

Potential Energy reflects the overall stability of the ligand-receptor complex, with lower values indicating greater stability. The RMS Gradient represents the energy gradient of the system, where lower values suggest successful energy minimization and stable conformation. Bond Energy, Angle Energy, and Dihedral Energy indicate the strength and stability of the bonds, angles, and torsions within the molecule. Van der Waals Energy and Electrostatic Energy measure non-covalent and electrostatic interactions between the ligand and the receptor, with more negative values signifying stronger interactions.

Based on the docking results, compounds with docking scores in the top 30% for ERK5 were identified, and further biological experiments were conducted on three selected compounds (4c, 4e, and 4k). These compounds exhibited favorable energy profiles, with compound 4e standing out due to its high LibDock score of 143.537, indicating excellent stereochemical and shape complementarity with ERK5. Its RMS Gradient was low at 0.00993, suggesting a stable minimized energy state. Potential Energy and van der Waals Energy of 4e were also favorable, reflecting strong binding affinities. Additionally, the compound’s Bond Energy, Angle Energy, and Dihedral Energy values indicated robust molecular stability. Overall, 4c, 4e, and 4k emerged as the most promising candidates due to their combination of high docking scores, stable energy profiles, and strong ligand-receptor interactions. Among these, compound 4e particularly stood out.

Based on MTT assay and qRT-PCR analysis, three compounds (4c, 4e, and 4k) showed the most promising results. These compounds contain distinct structural features: 4c has a benzimidazole ring, 4e incorporates a benzimidazole ring with an isopropyl group, and 4k includes a benzimidazole ring with dimethyl groups. All three compounds exhibited superior IC50 values and PCNA inhibition rates compared to other synthesized NAIMS derivatives (Table 1 and Table 2). The three selected compounds were subjected to comprehensive biological experiments.

Pharmacology

NAIMS inhibited ERK5 kinase activity but not ERK1/2 kinase activity.In recent years, conventional members of the MAPK family, such as MEK1/2 inhibitors, have undergone clinical trials, showing the potential to reduce tumor burden and enhance progression-free survival in advanced-stage cancers9,25,26. Among these, ERK5 stands out due to its unique structural and functional characteristics compared to other MAPKs, making it an appealing target for future therapies. In this study, Hela cells were used to test ERK5 inhibition, considering the correlation between ERK5 inhibition and Hela cell growth9,26. Similar to most kinases, including other MAPK members, the function of ERK5 is presumed to be driven by its kinase activity. Synthesized compounds (4c, 4e, and 4k) were evaluated for their ERK5 kinase inhibitory activity in vitro by Z’-LYTE™ Kinase Assay kit with a Ser/Thr 4 peptide. In this assay, the Z´-LYTE biochemical assay employs a fluorescence-based and coupled-enzyme format which can be used for kinase screening in an antibody-free format. 4c, 4e, and 4k exhibited a similar inhibitory effect on ERK5 kinase activity as XMD8-92 (Fig. 5, upper). Additionally, since ERK1/2 shares a similar kinase domain with ERK5, we tested whether NAIMS affected ERK1/2 kinase activity using a Z’-LYTE™ Kinase Assay kit with a Ser/Thr 3 peptide. The treatment with 4c, 4e, and 4k did not inhibit ERK1/2 kinase activity (Fig. 5, lower), similar to XMD8-92 in the previous report10,13. In a previous report, ERK1/2 suggested a bypass pathway to maintain cell growth and proliferation by providing a compensatory pathway in the absence or inhibition of ERK5 signaling1,13. The compensatory mechanism of ERK5 to ERK1/2 may be the key reason why the existing ERK5 inhibitors are difficult to exert efficacy in preclinical and clinical trials13. However, 4c, 4e, and 4k treatment had a negligible impact on ERK1/2 kinase activity. The IC50 values of 4c, 4e, and 4k were measured in a standard Z’-LYTE™ kinase assay against ERK5, yielding values of 8.8 μM, 5.1 μM, and 9.0 μM, respectively. These results indicate that 4c, 4e, and 4k have the potential to inhibit ERK5 by suppressing its kinase activity.

NAIMS inhibited the kinase activity of ERK5 but not ERK1/2. The Z’-LYTE™ Kinase Assay Kit–Ser/Thr 4 Peptide, and –Ser/Thr 3 Peptide were used to evaluate the effects of 4c, 4e, and 4k (1.25, 2.5, 5, and 10 µM) on ERK5 kinase activity (upper) and ERK1/2 kinase activity (lower). Data show the mean expression ± SD from three independent experiments.

NAIMS suppressed the expression of AP-1 reporter which is used as a marker of ERK5 kinase activity.ERK5 regulates the expression of a variety of genes by directly targeting transcription factors, such as MEF2 and Activator Protein 1 (AP1)27. Therefore, we employed an ERK5-driven AP-1 reporter assay to evaluate the inhibition of ERK5 activity by an ERK5 inhibitor within the cells. Hela cells were transfected with the pGL4.44[luc2P/AP1 RE/Hygro] plasmid, and AP-1 expression was assessed following treatment with 4c, 4e, and 4k. The expression of AP-1 in Hela cells significantly decreased upon treatment with 5 µM 4c, 4e, and 4k (Fig. 6). Consequently, it is evident that 4c, 4e, and 4k effectively suppressed ERK5 kinase activity.

AP-1 expression was reduced by NAIMS treatment. AP-1-luc reporter was transiently transfected in HeLa cells, which were then treated with 5 µM of 4c, 4e, and 4k, or XMD8-92. mRNA expression of AP-1 was checked using RT-PCR analysis with GAPDH serving as the control. Data show the mean expression ± SD of three independent experiments, calculated using the 2-ΔΔCq relative quantitation method. ##p < 0.01 vs. Control, *p < 0.05 vs. XMD8-92.

Inhibition of ERK5 by NAIMS promoted apoptotic cell death of Hela cells. Apoptosis, also known as programmed cell death, is a gene-controlled process essential for maintaining internal stability and is crucial in cancer therapy as it prevents tumor growth28. To assess the possibility of NAIMS on apoptosis induction in Hela cells, the DAPI staining assay and Annexin V staining assay were employed. DAPI is a DNA-sensitive fluorochrome and thus can check the differences in the cellular DNA of the cells. Fluorescent conjugates of annexin V are commonly used to identify apoptotic cells which determine the translocation of phosphatidylserine. DAPI staining results showed that treatment with 5 µM of 4c, 4e, and 4k triggered apoptosis in Hela cells compared to DMSO (Fig. 7A). Additionally, late apoptotic events were observed in Hela cells, increasing by 6.3%, 10.8%, and 14% after 24 h treatment with 5 µM of 4c, 4e, and 4k, respectively, similar to XMD8-92, which exhibited a 4.6% increase, compared with DMSO (Fig. 7B). Consequently, 4c, 4e, and 4 k demonstrated a pronounced apoptotic effect, with an increased ratio of late apoptotic cells in Hela cells after 4c, 4e, and 4k treatment.

NAIMS increased apoptosis in Hela cells. (A) HeLa cells were treated with 5 µM 4c, 4e, and 4k for 24 h, and morphologic changes were observed under a fluorescent microscope after DAPI staining. (B) The percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by flow cytometry (Annexin V/Propidium iodide staining) at 24 h treatment with 5 µM 4c, 4e, and 4k. Representative flow cytometry plots of cells and quantitative data are shown. The plots are divided into four quadrants: lower left quadrant, living cells; lower right quadrant, early apoptotic cells; upper left quadrant, necrotic cells; upper right quadrant, late apoptotic cells. Data represent the mean expression ± SD of three independent experiments.

NAIMS influenced the cell cycle progression. Cell cycle checkpoints at the G1/S and G2/M phases play a critical role in maintaining DNA integrity and regulating the passage of cells by the cell cycle29. Imidazole-based compounds have been shown to induce cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase30,31. The G2-M checkpoint is a mechanism that ensures the cell has repaired any DNA damage before proceeding to mitosis31. If the damage is too severe, the cell may undergo apoptosis. To further investigate the role of NAIMS in regulating cell proliferation, flow cytometry analysis was used to check the cell cycle progression. Treatment of 4c, 4e, and 4k slightly reduced cell cycle arrest at the G0/G1 phase, and induced arrest at the G2/M phase, with the proportion of cells at the G2/M phase of 6.7%, 8.1%, and 9.3% respectively, compared with DMSO (Fig. 8). Therefore, 4c, 4e, and 4k induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in Hela cells.

NAIMS induced cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase in HeLa cells. Cell cycle distributions were determined after treatment with 5 µM of 4c, 4e, and 4k, XMD8-92 or DMSO for 24 h. The cell cycle stages was analyzed using flow cytometry with PI staining after treatment. Data show the mean expression ± SD of three independent experiments.

In silico studies

Molecular modeling for 4c, 4e and 4 k. Figure 9 presented a molecular model depicting the interactions of each derivative at the ERK5 ATP-binding site, based on the crystal structure of the ERK5-compounds complex resolved at a 2.38 Å resolution. All three compounds shared a common hydrogen bond between the oxygen of the isoamyloxy group and Lys84. Notably, 4e possessed a unique structural feature with an isopropyl group in the benzimidazole ring, which engaged in alkyl-π interactions with Leu189 and aromatic alkyl-π interactions with Tyr166 (Fig. 9B). Furthermore, the molecule demonstrated structural stability through π interactions between the isopropyl group and naphthalene ring. These structural attributes were considered strong contributors to stable interactions within the ERK5 ATP-binding site. 4c had a benzimidazole ring that did not include an isopropyl group. The benzimidazole ring exhibited a π-π stacking interaction with Try66, while the 1-isoamyl of benzimidazole formed alkyl-π interactions with Leu189 (Fig. 9A). Interestingly, in 4e, the 1-isoamyl of benzimidazole showed different interactions, forming alkyl-π interactions with Try66. Conversely, 4k, featuring a benzimidazole ring with dimethyl groups at positions 5 and 6, exhibited π interactions between the benzimidazole and dimethyl moiety at Ile61 (Fig. 9C). The relatively low scores are presumed to be attributed to the restricted size of the binding site imposed by the dimethyl groups at positions 5 and 6, indicating interactions with limited spatial arrangements. These factors, including the potential destabilization of interactions within the ERK5 ATP binding site, may arise from the small size of the site, causing steric hindrance and acting as a factor that hinders effective interactions. Based on these results, we elucidated the potential for a stable and potent molecular interaction of 4e within the ERK5 ATP-binding site.

Collectively, molecular modeling analysis revealed that 4e forms strong and stable molecular interactions within the ERK5 ATP-binding site. Specifically, π interactions between the isopropyl group and the naphthalene ring enhanced the structural stability of the compound. These interactions likely contribute to 4e’s potent ERK5 inhibitory activity. Therefore, 4e holds promise as a lead candidate for ERK5-targeted cancer therapy.

Computational Off-Target Profiling of Compound 4e. To evaluate the off-target potential of compound 4e, computational analysis was conducted using SwissTargetPrediction32,33. This tool predicts the likelihood of interactions between 4e and various kinases based on structural and physicochemical similarities. The analysis revealed that major non-ERK5 kinases, including MAPK11, ERK2, and BRAF, exhibited no significant interaction probabilities, all recorded as 0%. These findings suggest that compound 4e has high selectivity for ERK5. While these computational results strongly support the potential of 4e as a selective ERK5 inhibitor, experimental validation, such as kinase profiling, remains necessary. Detailed results from the SwissTargetPrediction analysis are summarized in Table S1 in the supplementary information.

Computational Estimation of Binding Affinity and Dissociation Constants. As summarized in Table 4, the dissociation constants (Kd) and inhibition constants (Ki) for the key compounds 4e, 4c, and 4k were evaluated based on docking energy calculations34,35. Compound 4e exhibited a Kd value of 158.8 mM, which is lower than 4k (701.5 mM) and comparable to 4c (151.0 mM). The ΔG values ranged from −0.21 to −1.12 kcal/mol, with 4c showing the most favorable free energy of binding (− 1.12 kcal/mol). However, based on the docking scores (LibDock), 4e recorded a score of 143.537, demonstrating the most favorable interaction profile among the tested compounds. These results highlight compound 4e as the most promising ERK5 inhibitor candidate due to its balanced binding affinity and interaction profile, which align well with its observed biological activity.

Conclusion

In conclusion, inspired by the structure of the existing compound MHJ-627, which exhibited ERK5 inhibitory effects, we successfully synthesized 21 novel NAIMS compounds by combining 1,4-dialkoxy naphthalene with various imidazole or benzimidazole derivatives. Among them, 4c, 4e, and 4k showed predicted binding interactions with ERK5 in molecular modeling analysis, exhibited inhibitory effects on cell viability in the MTT assay, and significantly suppressed PCNA expression in qRT-PCR analysis, thus emerging as the most promising candidates. Notably, compound 4e reduced ERK5 kinase activity and was confirmed to induce late-stage apoptosis through DAPI staining and flow cytometry. Molecular modeling studies further supported these findings, highlighting that 4e forms stable molecular interactions within the ERK5 ATP-binding site.

Additionally, the computational estimation of binding parameters, including the dissociation constant (Kd) and the inhibition constant (Ki), provided preliminary insights into the potential interaction of 4e with ERK5. These findings align with observed biological activities, suggesting that 4e may have potential as an ERK5 inhibitor. This underscores the need for further exploration of 4e’s selectivity and efficacy.

Overall, this study highlights NAIMS compounds, particularly 4e, as promising lead candidates for selective ERK5 inhibition and the treatment of resistant cancers, laying an important foundation for further investigation into their therapeutic potential.

Materials and method

Chemical

Materials. All glassware was thoroughly dried in a convection oven. Reactions were monitored using thin-layer chromatography (TLC). Commercial TLC plates (silica gel 60 F254, Merck KGaA, Germany) were used, and spots were visualized under UV light at 254 or 365 nm. Some products were purified by flash column chromatography using 230–400 mesh ASTM silica gel (Merck KGaA, Germany) or by recrystallization with combinations of various solvents. Extra pure-grade solvents for column chromatography were purchased from Samchun Chemicals (Korea) and Duksan Chemicals (Korea). 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a JEOL JNM-ECZ400S (at 400 MHz for 1H NMR and 100 MHz for 13C NMR). In the 1H NMR spectra chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (ppm) relative to tetramethylsilane (TMS), and coupling constants are given in Hertz (Hz). Splitting patterns are indicated as follows: s, singlet; d, doublet; t, triplet; and m, multiplet. 13C NMR spectra are reported in ppm, referenced to chloroform-d and DMSO-d6. Melting points (m.p.) were determined on a Barnstead Electrothermal 9100 instrument and are uncorrected. High-resolution mass spectra were obtained with a JEOL JMS-700 mass spectrometer. All chemical reagents were acquired (Acros Organics, USA; Sigma-Aldrich, USA; and TCI, Japan) and were used as received. The 1-methylimidazole, 2-methylbenzimidazole and 5,6-dimethylbenzimidazole (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) used in this work are commercially available.

Synthesis of NAIMS derivatives (3a—3 h, 4a—4 m).The method for synthesizing NAIMS by reacting bromide intermediates (1.0 equiv.) with imidazole or benzimidazole derivatives (1.1—2.0 equiv.) in ACN (0.1 M) has been described in detail in previously reported publications14,15. Compounds 3a, 3c and 4a—4c were also previous reported14,15.

3-(2-(1,4-Bis(isoamyloxy)naphthalen-2-yl)−2-oxoethyl)−1-isoamyl-1H-imidazol-3-ium bromide (3b).

White solid (80%). m.p. : 93.0—93.7 ℃; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 0.95 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 6H), 0.98 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 6H), 1.00(d, J = 5.6 Hz, 6H), 1.49—1.64 (m, 1H), 1.73—1.80 (m, 4H), 1.87—1.97 (m, 4H), 4.17 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 4.21 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 4.33 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 5.97 (s, 2H), 7.22 (s, 1H), 7.75—7.78 (m, 3H), 7.90—7.91 (m, 1H), 8.15—8.19 (m, 1H), 8.22—8.26 (m, 1H), 9.23 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 22.09, 22.47, 22.64, 24.62, 24.82, 37.28, 38.24, 38.48, 47.34, 58.08, 66.53, 75.61, 101.98, 121.86, 122.33, 123.42, 123.61, 124.19, 127.93, 128.23, 129.07, 137.41, 150.64, 151.42, 191.16; HRMS (FAB) m/z Calcd. for C30H43N2O3Br [M—Br]+ 479.3274, found 479.3274.

3-(2-(1,4-Bis(isoamyloxy)naphthalen-2-yl)−2-oxoethyl)−1-methyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-3-ium bromide (3d).

White solid (79%). m.p. : 206.5 – 207.3 ℃. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 0.96 – 0.98 (m, 12H), 1.74 – 1.79 (m, 2H), 1.87 – 1.95 (m, 4H), 4.18 – 4.25 (m, 7H), 6.27 (s, 2H), 7.23 (s, 1H), 7.66 – 7.79 (m, 4H), 8.05 – 8.10 (m, 2H), 8.18 – 8.21 (m, 1H), 8.23 – 8.26 (m, 1H), 9.73 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 22.46, 22.64, 24.64, 24.82, 33.47, 37.26, 38.52, 55.80, 66.55, 75.51, 102.04, 113.63, 114.00, 122.34, 123.49, 123.71, 126.48, 126.67, 127.91, 128.29, 129.09, 131.52, 131.83, 146.88, 150.62, 151.47, 190.95; HRMS (FAB) m/z Calcd. for C30H37N2O3Br [M—Br]+ 473.2804, found 473.2803.

1-Benzyl-3-(2-(1,4-bis(isoamyloxy)naphthalen-2-yl)−2-oxoethyl)−1H-benzo[d]imidazol-3-ium bromide (3e).

White solid (83%). m.p. : 122.8 – 124.2 ℃. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) 0.95 – 0.99 (m, 12H), 1.73 – 1.78 (m, 2H), 1.86 – 1.95 (m, 4H), 4.19 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 4.23 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 5.92 (s, 2H), 6.28 (s, 2H), 7.22 (s, 1H), 7.38 – 7.47 (m, 3H), 7.52 – 7.54 (m, 2H), 7.66 – 7.69 (m, 2H), 7.76 – 7.78 (m, 2H), 8.04 – 8.06 (m, 1H), 8.08 – 8.10 (m, 1H), 8.18 – 8.21 (m, 1H), 8.23 – 8.25 (m, 1H), 9.89 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 22.45, 22.65, 24.64, 24.82, 37.27, 38.50, 49.91, 56.07, 66.54, 75.56, 102.03, 113.86, 114.30, 122.34, 123.48, 123.69, 126.71, 126.84, 127.91, 128.27, 128.86, 129.12, 130.56, 132.17, 133.98, 143.74, 150.62, 151.57, 190.91; HRMS (FAB) m/z Calcd. for C36H41N2O3Br [M—Br]+ 549.3117, found 549.3120.

3-(2-(1,4-Dimethoxynaphthalen-2-yl)−2-oxoethyl)−1-isoamyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-3-ium bromide (3f.).

White solid (75%). m.p. : 155.4 – 156.2 ℃. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) : 0.98 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 6H), 1.61 – 1.67 (m, 1H), 1.82 – 1.90 (m, 2H), 3.98 (s, 3H), 4.17 (s, 3H), 4.64 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 6.28 (s, 2H), 7.19 (s, 1H), 7.66 – 7.80 (m, 4H), 8.08 – 8.10 (m, 1H), 8.15 – 8.17 (m, 1H), 8.23 – 8.30 (m, 2H), 9.81 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) : 22.10, 24.96, 37.14, 45.23, 55.85, 56.16, 64.11, 101.21, 113.64, 114.25, 122.28, 123.30, 123.86, 126.53, 126.71, 127.89, 127.96, 129.03, 129.14, 130.65, 131.98, 143.38, 151.38, 153.04, 190.82; HRMS (FAB) m/z Calcd. for C26H29N2O3Br [M—Br]+ 417.2178, found 417.2176.

3-(2-(1,4-Diisopropoxynaphthalen-2-yl)−2-oxoethyl)−1-isoamyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-3-ium bromide (3g).

White solid (65%). m.p. : 193.8 – 195.6 ℃. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) ; 0.98 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 6H), 1.37 – 1.40 (m, 12H), 1.62 – 1.69 (m, 1H), 1.83 – 1.88 (m, 2H), 4.48 – 4.54 (m, 1H), 4.64 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 4.78 – 4.84 (m, 1H), 6.27 (s, 2H), 7.11 (s, 1H), 7.66 – 7.74 (m, 4H), 7.94 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 8.15 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 8.18 – 8.25 (m, 2H), 9.93 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) : 21.72, 21.88, 22.11, 25.03, 37.22, 45.29, 55.77, 70.48, 79.09, 103.82, 113.73, 113.92, 122.40, 123.96, 125.47, 126.57, 126.80, 127.44, 128.60, 128.97, 129.52, 130.61, 131.72, 143.57, 148.71, 149.16, 192.91; HRMS (FAB) m/z Calcd. for C30H37N2O3Br [M—Br]+ 473.2804, found 473.2803.

3-(2-(1,4-Bis(octyloxy)naphthalen-2-yl)−2-oxoethyl)−1-isoamyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-3-ium bromide (3h).

White solid (90%). m.p. : 94.8 – 96.1 ℃. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) : 0.83 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 6H), 0.98 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 6H), 1.23 – 1.41 (m, 16H), 1.46 – 1.60 (m, 4H), 1.62 – 1.69 (m, 1H), 1.81 – 1.88 (m, 4H), 1.97 – 2.04 (m, 2H), 4.15 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 4.21 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 4.64 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 6.26 (s, 2H), 7.19 (s, 1H), 7.65 – 7.78 (m, 4H), 8.07 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.16 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.18 – 8.21 (m, 1H), 8.22 – 8.26 (m, 1H), 9.85 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) : 13.88, 13.91, 22.03, 22.10, 24.99, 25.42, 25.63, 28.49, 28.61, 28.65, 28.90, 29.74, 31.19, 31.22, 37.15, 45.24, 55.88, 68.11, 76.85, 102.05, 113.67, 114.15, 122.27, 123.50, 123.68, 126.53, 126.67, 127.81, 128.23, 128.98, 129.11, 130.65, 131.95, 143.41, 150.61, 151.47, 190.91; HRMS (FAB) m/z Calcd. for C40H57N2O3Br [M—Br]+ 613.4369, found 613.4366.

3-((1,4-Bis(isoamyloxy)naphthalen-2-yl)methyl)−1-isoamyl-2-methyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-3-ium bromide (4d).

White solid (74%). m.p. : 185.3 – 187.1 ℃. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) : 0.88 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 6H), 0.95 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 6H), 0.97 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 6H), 1.58 – 1.84 (m, 9H), 2.98 (s, 3H), 3.96 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 4.00 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 4.51 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 5.88 (s, 2H), 6.62 (s, 1H), 7.55 – 7.66 (m, 4H), 7.96 – 8.05 (m, 3H), 8.12 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 10.92, 22.19, 22.37, 22.60, 24.65, 24.72, 25.27, 37.10, 38.42, 43.73, 44.30, 66.38, 74.12, 104.29, 113.06, 121.88, 122.04, 126.11, 126.25, 126.43, 127.37, 127.97, 130.64, 131.24, 146.00, 150.84, 151.91; HRMS (FAB) m/z Calcd. for C34H47N2O2Br [M—Br]+ 515.3637, found 515.3636.

3-((1,4-bis(isopentyloxy)naphthalen-2-yl)methyl)−1-isoamyl-2-isopropyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-3-ium bromide (4e).

White solid (74%). m.p. : 158.8 – 160.1 ℃. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) ; 0.85 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 6H), 0.96 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 6H), 1.00 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 6H), 1.43 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 1.60 – 1.55 (m, 2H), 1.67 – 1.76 (m, 5H), 1.80 – 1.87 (m, 2H), 3.93 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 3.97 – 4.03 (m, 3H), 4.57 (t, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 5.96 (s, 2H), 6.43 (s, 1H), 7.55 – 7.59 (m, 1H), 7.64 – 7.69 (m, 3H), 7.97 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.02 – 8.06 (m, 2H), 8.11 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 18.66, 22.28, 22.38, 22.67, 24.68, 24.77, 25.13, 25.62, 37.00, 37.82, 38.48, 44.45, 44.60, 66.41, 74.08, 103.38, 113.41, 113.55, 121.95, 122.11, 122.46, 125.99, 126.53, 126.69, 127.57, 128.09, 131.03, 131.83, 145.65, 150.93, 156.22; HRMS (FAB) m/z Calcd. for C36H51N2O2Br [M—Br]+ 543.3950, found 543.3951.

3-((1,4-Bis(isoamyloxy)naphthalen-2-yl)methyl)−1-isoamyl-2-phenyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-3-ium bromide (4f.).

White solid (80%). m.p. : 158.8 – 160.3 ℃. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) ; 0.67(d, J = 6.4 Hz, 6H), 0.91 – 0.94 (m, 12H), 1.44 – 1.51 (m, 1H), 4.56 – 1.66 (m, 6H), 1.74 – 1.85 (m, 2H), 3.82 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 3.87 (t, J = 6.74 Hz, 2H), 4.31 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 5.70 (s, 2H), 6.22 (s, 1H), 7.51 – 7.55 (m, 1H), 7.58 – 7.62 (m, 1H), 7.70 – 7.82 (m, 5H), 7.92 – 7.94 (m, 3H), 8.04 – 8.06 (m, 1H), 8.13 – 8.15 (m, 1H), 8.22 – 8.24 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 21.78, 22.45, 22.62, 24.62, 24.70, 24.84, 37.16, 37.20, 38.42, 44.39, 44.85, 66.27, 73.97, 104.36, 113.60, 113.95, 121.47, 121.80, 121.93, 122.03, 125.96, 126.42, 126.89, 126.97, 127.29, 127.76, 129.62, 130.48, 130.85, 131.53, 133.00, 145.88, 150.22, 150.51; HRMS (FAB) m/z Calcd. for C39H49N2O2Br [M—Br]+ 577.3793, found 577.3793.

3-((1,4-Bis(isoamyloxy)naphthalen-2-yl)methyl)−1-isoamyl-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)−1H-benzo[d]imidazol-3-ium bromide (4g).

White solid (45%). m.p. : 137.9 – 138.5 ℃. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) ; 0.70 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 6H), 0.90 – 0.93 (m, 12H), 1.45 – 1.51 (m, 1H), 1.56 – 1.66 (m, 6H), 1.73 – 1.84 (m, 2H), 3.82 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.86 – 8.89 (m, 5H), 4.32 (t, J = 7.6. Hz, 2H), 5.68 (s, 2H), 6.22 (s, 1H), 7.25 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.51 – 7.55 (m, 1H), 7.58 – 7.62 (m, 1H), 7.70 – 7.75 (m, 2H), 7.84 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.93 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.06 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.09 – 8.13 (m, 1H), 8.18 – 8.21 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) : 21.89, 22.47, 22.63, 24.65, 24.77, 24.87, 37.22, 38.43, 44.38, 44.85, 55.73, 66.29, 73.96, 104.40, 112.94, 113.58, 113.86, 115.15, 121.97, 122.06, 125.98, 126.43, 126.78, 126.86, 127.31, 127.80, 130.81, 131.52, 132.31, 145.88, 150.53, 162.49; HRMS (FAB) m/z Calcd. for C40H51N2O3Br [M—Br]+ 607.3899, found 607.3896.

3-((1,4-Bis(isoamyloxy)naphthalen-2-yl)methyl)−2-(4-fluorophenyl)−1-isoamyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-3-ium bromide (4h).

White solid (72%). m.p. : 182.2 – 183.6 ℃. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) ; 0.69 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 6H), 0.91 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 6H), 0.93 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 6H), 1.47 – 1.52 (m, 1H), 1.55 – 1.67 (m, 6H), 1.71 – 1.86 (m, 2H), 3.80 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 3.89 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 4.29 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 5.70 (s, 2H), 6.26 (s, 1H), 7.51 – 7.62 (m, 4H), 7.74 – 7.78 (m, 2H), 7.91 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.94 – 7.98 (m, 2H), 8.06 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.18 – 8.20 (m, 1H), 8.21 – 8.23 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) : 21.74, 22.39, 22.54, 24.55, 24.69, 24.80, 37.16, 38.36, 44.34, 44.92, 66.27, 73.85, 104.54, 113.64, 113.85, 116.83, 117.05, 117.82, 121.77, 121.84, 122.00, 125.97, 126.37, 126.87, 126.96, 127.21, 127.70, 130.78, 131.63, 133.37, 133.47, 145.95, 149.47, 150.45, 163.24, 165.75; HRMS (FAB) m/z Calcd. for C39H48FN2O2Br [M—Br]+ 595.3699, found 595.3699.

3-((1,4-Bis(isoamyloxy)naphthalen-2-yl)methyl)−2-(hydroxymethyl)−1-isoamyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-3-ium bromide (4i).

White solid (27%). m.p. : 139.8 – 141.1 ℃. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) ; 0.85 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 6H), 0.97 – 0.99 (m, 12H), 1.55 – 1.60 (m, 2H), 1.71 – 1.92 (m, 7H), 3.93 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 4.04 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 4.65 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 5.23 (s, 2H), 5.97 (s, 2H), 6.72 (s, 1H), 7.54 – 7.68 (m, 4H), 7.85 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.04 – 8.10 (m, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 22.22, 22.36, 22.64, 24.70, 24.74, 25.44, 37.05, 37.89, 38.51, 44.17, 44.28, 51.61, 66.34, 74.43, 103.93, 113.34, 113.71, 122.04, 126.06, 126.49, 126.89, 127.03, 127.40, 127.97, 130.67, 130.88, 145.87, 150.85, 151.47; HRMS (FAB) m/z Calcd. for C34H47N2O3Br [M—Br]+ 531.3586, found 531.3589.

3-((1,4-Bis(isoamyloxy)naphthalen-2-yl)methyl)−1-isoamyl-2-(1-methoxyethyl)−1H-benzo[d]imidazol-3-ium bromide (4j).

White solid (74%). m.p. : 143.8 – 145.2 ℃. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) : 0.85 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 6H), 0.96 – 1.00 (m, 12H), 1.54 – 1.61 (m, 5H), 1.67 – 1.92 (m, 7H), 3.33 (s, 3H), 3.93 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 4.00 – 4.04 (m, 2H), 4.60 – 4.70 (m, 2H), 5.49 (q, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H), 5.97 – 6.06 (m, 2H), 6.51 (s, 1H), 7.55 – 7.59 (m, 1H), 7.64 – 7.73 (m, 3H), 8.02 – 8.05 (m, 2H), 8.11 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 19.12, 22.10, 22.32, 22.38, 22.66, 24.68, 24.77, 25.68, 37.03, 37.65, 38.48, 44.51, 44.78, 58.09, 66.39, 70.24, 74.21, 103.68, 113.71, 113.91, 121.99, 122.12, 122.26, 126.05, 126.61, 126.96, 127.11, 127.59, 128.04, 131.25, 131.98, 145.76, 150.92, 151.25; HRMS (FAB) m/z Calcd. for C36H51N2O3Br [M—Br]+ 559.3899, found 559.3898.

3-((1,4-Bis(isoamyloxy)naphthalen-2-yl)methyl)−1-isoamyl-5,6-dimethyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-3-ium bromide (4k).

White solid (62%). m.p. : 183.6 – 185.2 ℃. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) ; 0.90 – 0.95 (m, 18H), 1.53 – 1.58 (m, 1H), 1.68 – 1.88 (m, 8H), 2.37 (s, 3H), 2.40 (s, 3H), 3.99 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 4.11 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 4.45 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 5.76 (s, 2H), 7.04 (s, 1H), 7.57 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.64 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.88 (s, 2H), 8.01 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.16 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 9.71 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 19.96, 20.16, 22.11, 22.43, 22.59, 24.68, 24.83, 25.00, 37.18, 37.31, 38.59, 45.12, 45.68, 66.59, 74.10, 105.64, 113.27, 113.31, 121.68, 122.03, 122.13, 126.37, 126.56, 127.32, 128.04, 129.54, 129.69, 136.28, 136.49, 140.89, 146.74, 150.93; HRMS (FAB) m/z Calcd. for C35H49N2O2Br [M—Br]+ 529.3793, found 529.3794.

3-((1,4-Bis(isoamyloxy)naphthalen-2-yl)methyl)−1-isoamyl-5,6-diphenyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-3-ium bromide (4l).

Brown oil (100%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) ; 0.88 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 6H), 0.93 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 6H), 0.95 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 6H), 1.60 – 1.63 (m, 1H), 1.71 – 1.88 (m, 8H), 4.01 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 4.14 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 4.57 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 5.86 (s, 2H), 7.08 – 7.11 (m, 2H), 7.14 – 7.17 (m, 3H), 7.27 – 7.28 (m, 6H), 7.58 – 7.66 (m, 2H), 8.00 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 8.15 (s, 1H), 8.16 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.24 (s, 1H), 9.92 (s, 1H ); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 22.10, 22.43, 22.50, 24.57, 24.84, 25.01, 37.34, 38.60, 40.41, 45.32, 45.92, 66.65, 74.14, 105.85, 115.12, 115.18, 121.69, 121.97, 122.14, 126.44, 126.62, 127.29, 127.35, 128.04, 128.12, 129.65, 129.87, 130.57, 130.69, 139.35, 139.50, 139.82, 139.86, 142.76, 146.83, 151.01; HRMS (FAB) m/z Calcd. for C45H53N2O2Br [M—Br]+ 653.4106, found 653.4101.

3-((1,4-Bis(isoamyloxy)naphthalen-2-yl)methyl)−5,6-dibromo-1-isoamyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-3-ium bromide (4m).

White solid (77%). m.p. : 208.8 – 210.1 ℃. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) ; 0.89 – 0.96 (m, 18H), 1.53 – 1.60 (m, 1H), 1.70 – 1.90 (m, 8H), 3.99 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 4.12 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 4.46 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 5.77 (s, 2H), 7.08 (s, 1H), 7.57 – 7.67 (m, 2H), 8.00 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.16 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 8.71 (s, 1H), 8.72 (s, 1H), 9.85 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 22.11, 22.48, 22.63, 24.68, 24.86, 25.02, 37.11, 37.35, 38.60, 45.71, 46.13, 66.65, 74.24, 105.82, 118.68, 118.86, 121.34, 121.87, 121.91, 122.04, 122.18, 126.49, 126.69, 127.38, 128.02, 131.39, 131.58, 143.87, 146.81, 151.02; HRMS (FAB) m/z Calcd. for C33H43Br3N2O2 [M—Br] + 657.1691, found 657.1685.

In silico docking study

Molecular Docking and Ligand Preparation. The molecular modelling, including the docking procedure, was performed using Discovery Studio 2019 (Accelrys, San Diego, CA, USA). The crystal structure of the ERK5 ATP-binding site was obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB code 5O7I). Proteins were prepared using the Macromolecules protocol, including key steps such as energy minimization and adjustment of protonation states. Ligand preparation and optimization were conducted via the ‘Prepare Ligands’ module in Discovery Studio. The docking site was identified based on the active site information from the PDB entry, and the docking process employed the simulation-based LibDock protocol, which utilizes a CHARMm-based force field. LibDock, a high-throughput docking algorithm, was used to position compounds in the active site(s) of a receptor molecule. The docked poses were evaluated by scoring, ranking, and analysing binding affinities through receptor-ligand complex interactions. Binding energy, representing the interaction strength between a ligand and its receptor, was calculated using the free energy perturbation (FEP) method.

Computational Estimation of Dissociation Constants and Binding Affinity. Dissociation constants (Kd) were calculated based on Gibbs free energy (ΔG) values obtained from molecular docking simulations. The Kd values were derived using the relationship between free energy and temperature. Inhibition constants (Ki) were assumed to be approximately equal to the Kd values, as the ligand concentration in the system was considered negligible. This approach was employed to quantitatively evaluate the binding affinity of the compounds and to assess their correlation with docking scores and observed biological activity.

Pharmacology

Cell culture. Hela cells (KCLB #10002) were purchased from the Korean Cell Line Bank (Seoul, Korea). Hela cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM, WelGene, Korea) supplemented with 10% Fetal bovine serum (FBS, Thermo Fisher Scientific Solution LLC, Canada) and 1% Penicillin–streptomycin solution (Global Life Sciences Solutions USA LLC, USA) at 37 ℃ in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% humidity.

ERK5 and ERK1/2 kinase assay. Hela cell lysates (10—100 µg per well of a 96-well plate) were prepared to determine ERK5 and ERK1/2 kinase activity using Z’-LYTE Kinase assay Kit – Ser/Thr 4 peptide kit, – Ser/Thr 3 peptide kit (Invitrogen, USA). ERK5 and ERK1/2 kinase activity was measured by the Coumarin (Ex.400 nm, Em. 445 nm) and Fluorescein (Ex. 400 nm, Em. 520 nm) emission signals on a fluorescence plate reader.

Cells transfection. Hela cells (2 × 105 per well in a 6-well) were prepared for transfection. The pGL4.44[luc2P/AP1 RE/Hygro] vector, which contains six copies of an AP-1 response element (AP-1 RE), was purchased (Promega, USA). Hela cells were transfected with pGL4.44[luc2P/AP1 RE/Hygro] using Lipofectamine® 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Cells were collected 48 h after transfection or used for subsequent treatment.

RNA isolation and quantitative RT-PCR. Hela cells (5 × 105 per well in a 6-well) were seeded to adhere for 24 h, then starved for 20 h and treated with 1, 2.5, and 5 µM XMD8-92 or 4c, 4e, and 4k for 24 h. TRIzol reagent (Life Technology, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) was used to extract total RNA. cDNA was synthesized from RNA purified using reverse transcriptase (NanoHelix, Korea) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All RT-PCR reactions were performed in duplicates of a CFX96TM Real-time PCR (Bio-Rad, USA) with 2 × real-time PCR master mix (BIOFACT, Korea). The mRNA levels of the housekeeping gene GAPDH were used for normalization and the relative expression level was analyzed using the 2−∆∆Cq method. The primer sequences used for qRT-PCR in Table 5.

Cell proliferation. Hela cells (1 × 105) were seeded in 96-well culture plates for 24 h at 37 ℃, 5% CO2. The cells were then treated with 1, 2.5, and 5 µM XMD8-92 or 4c, 4e, and 4k for 24 h, DMSO was used as a control. All experiments were performed in duplicate. Cell viability was determined with an MTT (Invitrogen, USA) assay at 570 nm using a microplate reader (Bio-Tek Instruments, USA)36,37. The IC50 (the half-maximal inhibitory concentration) values were determined using linear regression.

DAPI staining assay. Hela cells (5 × 103) were seeded in 24-well plates for 24 h, then treated with 1, 2.5, and 5 µM XMD8-92 or compounds 4c, 4e, and 4k for 24 h. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min. After washing, a 300 nM DAPI stain solution (AnaSpec, USA) was added to the cells and incubated for 15 min in the dark. Stained cells were examined by fluorescence microscopy to identify apoptotic cells.

Cell apoptosis and cell cycle analysis. Hela cells (5 × 105) were seeded in 6-well plates for 24 h and then starved for 20 h before treatment with 1, 2.5, and 5 µM XMD8-92 or compounds 4c, 4e, and 4k for 24 h. Cell apoptosis was analyzed using an annexin V-FITC/PI detection kit (BD Biosciences, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Flow cytometry (BD Accuri C6, BD Biosciences, USA) was used to detect cell apoptosis.

For cell cycle analysis, DNA was stained with 50 µg/ml propidium iodide (PI) (BD Biosciences, USA) containing 20 units/ml RNase A (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) at 37℃ for 40 min in the dark. BD Accuri C6 flow cytometry (BD Biosciences, USA) was then employed to perform cell cycle analysis.

Statistics. The results shown are representative of at least two independent experiments. Each independent experiment contained two or more biological replicates (n ≥ 2), and data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed with Microsoft Excel and Adobe Illustrator. Comparisons between two groups were analyzed using Student’s t‐test and P value. Differences were considered significant at P value < 0.05 or 0.01.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Abbreviations

- ACN:

-

Acetonitrile

- AP1:

-

Activator protein 1

- BMK1:

-

Big MAP kinase 1

- DMEM:

-

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium

- DMF:

-

N,N-Dimethylformamide

- DMSO:

-

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- ERK1/2:

-

Extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2

- ERK5:

-

Extracellular signal-regulated kinases 5

- FBS:

-

Fetal bovine serum

- FEP:

-

Free energy perturbation

- FITC:

-

Fluorescein isothiocyanate

- JNK:

-

C-Jun N-terminal kinase

- MAPK:

-

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MEF2:

-

Myocyte Enhancer Factor 2

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PCNA:

-

Proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- PD-L1:

-

Programmed death-ligand 1

- PI:

-

Propidium iodide

- SAR:

-

Structure–activity relationship

References

Cook, S. J. & Lochhead, P. A. ERK5 signalling and resistance to ERK1/2 pathway therapeutics: The path less travelled?. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 10, 839997 (2022).

Stecca, B. & Rovida, E. Impact of ERK5 on the Hallmarks of Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 1426 (2019).

Nithianandarajah-Jones, G. N., Wilm, B., Goldring, C. E. P., Müller, J. & Cross, M. J. ERK5: Structure, regulation and function. Cell. Signal. 24, 2187–2196 (2012).

Ippolito, F. et al. Extracellular signal-Regulated Kinase 5 (ERK5) is required for the Yes-associated protein (YAP) co-transcriptional activity. Cell Death Dis. 14, 32 (2023).

Monti, M. et al. Clinical significance and regulation of ERK5 expression and function in cancer. Cancers (Basel). 14, 348 (2022).

Rovida, E. et al. The mitogen-activated protein kinase ERK5 regulates the development and growth of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut 64, 1454–1465 (2015).

Yang, Q. et al. Pharmacological inhibition of BMK1 suppresses tumor growth through promyelocytic leukemia protein. Cancer Cell 18, 258–267 (2010).

Lochhead, P. A. et al. Paradoxical activation of the protein kinase-transcription factor ERK5 by ERK5 kinase inhibitors. Nat. Commun. 11, 1383 (2020).

Lin, E. C. K. et al. ERK5 kinase activity is dispensable for cellular immune response and proliferation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 11865–11870 (2016).

Cook, S. J., Tucker, J. A. & Lochhead, P. A. Small molecule ERK5 kinase inhibitors paradoxically activate ERK5 signalling: Be careful what you wish for…. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 48, 1859–1875 (2020).

Chen, H. et al. Discovery of a novel allosteric inhibitor-binding site in ERK5: Comparison with the canonical kinase hinge ATP-binding site. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Struct Biol. 72, 682–693 (2016).

Deng, X. et al. Discovery of a benzo[e]pyrimido-[5,4-b][1,4]diazepin-6(11H)-one as a potent and selective inhibitor of big MAP kinase 1. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2, 195–200 (2011).

Pan, X. et al. Development of small molecule extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) inhibitors for cancer therapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 12, 2171–2192 (2022).

Gomez, N., Erazo, T. & Lizcano, J. M. ERK5 and cell proliferation: Nuclear localization Is what matters. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 4, 105 (2016).

Sharma, P., LaRosa, C., Antwi, J., Govindarajan, R. & Werbovetz, K. A. Imidazoles as potential anticancer agents: An update on recent studies. Molecules 26, 4213 (2021).

Gangavaram, V. M. S. et al. Imidazole derivatives show anticancer potential by inducing apoptosis and cellular senescence. Med. Chem. Commun. 5, 1751–1760 (2014).

Gujjarappa, R. et al. Overview on biological activities of imidazole derivatives in imidazole-based compounds: Recent advances and applications 135–227 (Springer, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-8399-2_6.

Samsuzzaman, M. et al. Identification of a potent NAFLD drug candidate for controlling T2DM-mediated inflammation and secondary damage in vitro and in vivo. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 943879 (2022).

Lee, J. et al. Antifungal activity of 1,4-dialkoxynaphthalen-2-acyl imidazolium salts by inducing apoptosis of pathogenic candida spp. Pharmaceutics. 13, 312 (2021).

Lee, H. et al. Synthesis of 1,4-Dialkoxynaphthalene-based imidazolium salts and their cytotoxicity in cancer cell lines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 2713 (2023).

Hwang, J., Moon, H., Kim, H. & Kim, K. Y. Identification of a novel ERK5 (MAPK7) inhibitor, MHJ-627, and verification of its potent anticancer efficacy in cervical cancer HeLa cells. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 45, 6154–6169 (2023).

Lee, Y. S. et al. Significant facilitation of metal-free aerobic oxidative cyclization of imines with water in synthesis of benzimidazoles. Tetrahedron 71, 532–538 (2015).

Ma, Z. et al. Discovery of benzimidazole derivatives as potent and selective aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A1 (ALDH1A1) inhibitors with glucose consumption improving activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 46, 116352 (2021).

Cardano, M., Tribioli, C. & Prosperi, E. Targeting proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) as an effective strategy to inhibit tumor cell proliferation. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 20, 240–252 (2020).

Hoang, V. T. et al. Oncogenic signaling of MEK5-ERK5. Cancer Lett. 392, 51–59 (2017).

Miller, D. C. et al. Modulation of ERK5 activity as a therapeutic anti-cancer strategy. J. Med. Chem. 66, 4491–4502 (2023).

Lavoie, H., Gagnon, J. & Therrien, M. ERK signalling: A master regulator of cell behaviour, life and fate. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 607–632 (2020).

Nonnenmacher, L. et al. Cell death induction in cancer therapy - Past, present, and future. Crit. Rev. Oncog. 21, 253–267 (2016).

Gámez-García, A. et al. ERK5 Inhibition induces autophagy-mediated cancer cell death by activating ER stress. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9, 742049 (2021).

Kang, C., Kim, J. S., Kim, C. Y., Kim, E. Y. & Chung, H. M. The Pharmacological inhibition of ERK5 enhances apoptosis in acute myeloid leukemia cells. Int. J. Stem Cells 11, 227–234 (2018).

Barnaba, N. & LaRocque, J. R. Targeting cell cycle regulation via the G2-M checkpoint for synthetic lethality in melanoma. Cell Cycle 20, 1041–1051 (2021).

Daina, A., Michielin, O. & Zoete, V. SwissTargetPrediction: updated data and new features for efficient prediction of protein targets of small molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W357–W364 (2019).

Gfeller, D. et al. SwissTargetPrediction: a web server for target prediction of bioactive small molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, W32–W38 (2014).

Morris, G. M. et al. Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and an empirical binding free energy function. J. Comput. Chem. 19, 1639–1662 (1998).

Trott, O. & Olson, A. J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 31, 455–461 (2010).

Kim, M., Kim, J. G. & Kim, K. Y. Trichosanthes kirilowii extract promotes wound healing through the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in keratinocytes. Biomimetics 7, 154 (2022).

Nguyen, A. T. et al. MSF enhances human antimicrobial peptide β-defensin (HBD2 and HBD3) expression and attenuates inflammation via the NF-κB and p38 signaling pathways. Molecules 28, 2744 (2023).

Funding

This work was supported by the GRRC program (GRRC-KyungHee 2023(B01) of Gyeonggi province, Republic of Korea.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.L. synthesized the compounds and conducted in silico molecular docking studies; A.-T.N. conducted biological screenings, established cell models, and implemented experiments; H.L. and A.-T.N. prepared the original draft, collected data, and plotted the graphs; H.C., K.-Y.K., and H.K. conceptualized, supervised, and revised the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, H., Nguyen, AT., Choi, H. et al. Anti-cancer Effects of 1,4-Dialkoxynaphthalene-Imidazolium Salt Derivatives through ERK5 kinase activity inhibition. Sci Rep 15, 13648 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96306-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96306-x