Abstract

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is an epithelial bile duct cancer frequently found at an advanced stage, leading to poor response to current therapies. Although gemcitabine (GEM) and cisplatin (CIS) are the current gold-standard for treating unresectable CCA, GEM resistance often occurs. To predict the response to GEM, we evaluated chromosomal aberrations using a chromosome microarray, and their association with GEM response by histoculture drug response assay. Our findings revealed principal component analysis and orthogonal partial-least square discriminant analysis cross validated score plot between response and non-response groups were different. Different signature patterns of chromosomes between response and non-response groups analyzed by heatmap analysis identified 34 regions of 15 chromosomes. An increased signal in responders and a decreased signal in non-responders were found in regions 4q32.1, 5q12.3, 10q21.3, 11p11.2, 11q14.2, 16p11.2, 17q22, 21q21.3 and 22q12.3. In contrast, a high signal in non-responders and low signal in responders were seen in regions 2q37.2, 11q14.1, 16q22.3 and 16q23.3. High signal of CDH13 and TENM4 were demonstrated in GEM non-response, while a high CWC27 signal was noted in GEM response. This signature pattern could provide the knowledge to improve a predictive biomarker for GEM response, benefitting for individual CCA patient management and chemotherapeutic selection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A malignancy of bile duct epithelial cells arising along both intra- and extra-hepatic biliary ducts is referred to as cholangiocarcinoma, or CCA1,2. Global epidemiological studies of CCA have shown a rise in incidence and mortality rates, with CCA being the second most common primary liver cancer3. Most CCA presentations are initially clinically silent, leading to diagnosis at an advanced stage. This results in poor prognosis, poor response to current therapies and high mortality rates4. At present, studies report that combined gemcitabine-cisplatin (GEM-CIS) chemotherapy extends survival in patients with advanced biliary tract cancer (BTC)5. Moreover, previous reports suggest CCA patients who undergo surgery followed by chemotherapy had increased median survival6. Patient survival time with regards to cancer progression varies depending on subtype and cancer stage. The current standard first-line chemotherapy for CCA is a combination of GEM-CIS. This regimen has demonstrated improved survival outcomes compared to gemcitabine (GEM) monotherapy5. However, research is actively exploring treatment options for patients with CCA who have progressed after first-line chemotherapy. Despite the emergence of novel therapeutic strategies for CCA, including immunotherapy with IDH inhibitors7, which has demonstrated efficacy in advanced cases, the optimal treatment paradigm remains under investigation. While attempts to enhance first-line gemcitabine-based therapy with anti-EGFR agents have yielded statistically non-significant improvements in overall survival8, these studies underscore the continued relevance of gemcitabine as a foundational component of CCA treatment. Ongoing research explores the potential of gemcitabine in combination with or in comparison to other agents to improve treatment efficacy and patient survival. These investigations include a growing body of evidence surrounding immunotherapies, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), among other novel approaches9. For instance, a recent study demonstrated that combining GEM-CIS with durvalumab significantly improved overall survival compared to GEM-CIS alone, with concordant improvements in pre-specified secondary endpoints, including progression-free survival and objective response rate10. Given that GEM is a cornerstone of current CCA chemotherapy, predicting its efficacy is crucial for personalized medicine. Identifying patients likely to benefit from GEM monotherapy could potentially reduce unnecessary exposure to other chemotherapeutic agents and their associated toxicities. Conversely, recognizing GEM non-responders would allow for timely consideration of alternative treatment strategies, such as combination therapies or clinical trials. Additionally, individual patients vary in their genomic, proteomic, and metabolomic background, all of which are considered crucial factors. Several studies have identified biomarkers in biliary tract cancer that affect clinical response. Therefore, understanding the molecular alterations associated with GEM unresponsiveness is essential for optimizing treatment strategies and advancing personalized medicine in CCA. For example, the alterations in genes involved in DNA damage repair11 and the expression of mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR) and tumor mutational burden (TMB), which may serve as potential predictive biomarkers for immunotherapy12. Therefore, molecular techniques, especially omics and chromosome microarray, are useful in predicting the patient’s prognosis and response to chemotherapy.

The chromosome microarray (CMA) is a technique used to study structural and numerical variations in the human genome. For a complex disease like cancer, CMA is a valuable tool for understanding the underlying molecular genetics. Correlations between chromosomal loss/gain and tumor DNA ploidy, genotypes and phenotypes using CMA could be used as biomarkers for many cancers. Abnormality of chromosomes in copy number alteration (CNA) and loss of heterozygosity (LOH) is commonly associated with poor prognosis in several cancers including CCA. Array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) analysis in rat tissues showing a specific pattern (+ 2q45, +Xq22, − 12p12), have been identified in early stage CCA, whereas the JAK-STAT signaling pathway was highly correlated to later stages of disease13. In addition, deletion of 1p, 3p and 14q and amplification of 1q, 7p, 7q and 8q exclusively were identified in CCA. Ruben Jansen and co-workers demonstrated that tumors with LNM (N1) had more alterations with gains (3p, 4q, 5p, 13q) and losses (17p and 20p). Interestingly, unsupervised clustering such as PCA (Principal Component Analysis) revealed a poor prognosis subclass with increased alterations significantly associated with tumor differentiation and survival14. Furthermore, the developed genomic model comprised four chromosomal regions that seem to enable the distinction between iCCA and eCCA, with an accuracy of 71.43% (95% CI 43–100%)15. A powerful toolkit for analyzing complex chromosomal aberration data including PCA and OPLS-DA (Orthogonal Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis) offers significant advantages over traditional methods by reducing dimensionality, visualizing data, identifying outliers, selecting features, and building predictive models, these techniques can significantly improve the accuracy, sensitivity, and interpretability of chromosomal aberration analysis. Hence, chromosomal aberration is a key factor in severity of cancer and induced resistant mechanisms. Chromosome microarray and copy number variation could be used to predict the response of a CCA patient to GEM. While associations between chromosomal abnormalities and chemotherapy response have been established, the specific impact of these aberrations on gemcitabine efficacy in CCA remains poorly understood.

Taken together, this study aims to evaluate the different patterns of chromosomal abnormality in cholangiocarcinoma and their association with GEM response in cholangiocarcinoma, using CMA technique and bioinformatic tools analysis.

Results

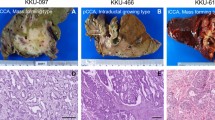

The characteristics of CCA frozen tissues/demographic and clinicopathologic information

All liver tissues were diagnosed with CCA and consisted of 2 types: intrahepatic (n = 6) and perihilar (n = 4). The majority were male (7 of 10 cases). The average age of these patients was 64 years old (50–79 years old). HDRA of CCA tissues showed 4 cases with response to gemcitabine (GEM), and 6 cases without (“non-response”), as seen in Table 1.

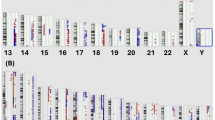

Chromosomal abnormality in CCA patients

Chromosomal aberration was found in CCA patients both responsive and unresponsive to GEM. There was both chromosomal gain and loss in the non-response group, while only gain was observed in the response group. Among the non-response group, loss of chromosomes 1, 2, 6, 9 and 19 and gain of chromosomes 7, 10, 13 and 20 was found (Fig. 1; Table 2). In addition, both gain and loss of chromosomes 8, 14 and 18 were found in this group. Gain of chromosomes 3, 5, 11, 14, 15 and 16 was demonstrated in the response group (Fig. 1; Table 2). This study demonstrated that unresponsive receivers of GEM had more chromosomal abnormalities than those responsive to GEM.

Chromosomal aberration in response and non-response CCA patient groups. The non-response group had both chromosomal gain and loss, while the response group had only chromosomal gain. Within the non-response group there was loss of chromosomes 1, 2, 6, 9 and 19 and gain of chromosomes 7, 10, 13 and 20. In addition, Chromosomes 8, 14 and 18 could be either gained or lost. In the response group there was gain of chromosomes 3, 5, 11, 14, 15 and 16. This study showed that the non-response group had greater degrees of chromosomal abnormality than the response group.

Different patterns of copy number variation between response and non-response groups of CCA patients

Chromosomal aberrations analyzed by MetaboAnalyst, with Log 2 Ratio values (Fig. 2; Table 3, Additional File 1), demonstrated a high Log 2 Ratio for chromosomes 2 (2q37.2), 10 (10q31.32), 11 (11q13.3, 11q14.1), and 16 (16q22.3, 16q23.3) in the non-response group, while these values were lower in the response group. In contrast, a low signal of chromosome 4 (4q32.1), 5 (5q12.3), 10 (10q21.3), 11 (11p11.2, 11q14.2), 16 (16p11.2), 17q (17q22), 21 (21q21.3) and 22 (22q12.3) was detected in the non-response-group, whereas these signals were higher in the response group.

Of the markers analyzed in the Heatmap (Fig. 2) and fold change analysis (Table 4), 10 of 50 were significantly different between the non-response and response groups. In addition, the increased signal of CCA tissues with response to GEM and decreased signal of CCA tissues without response to GEM were clearly recorded at locations 4q32.1, 5q12.3, 10q21.3, 11p11.2, 11q14.2, 16p11.2, 17q22, 21q21.3 and 22q12.3. In contrast, high signals in the non-response group and low signals in the response group was seen in regions 2q37.2, 11q14.1, 16q22.3 and 16q23.3. These regions consisted of several genes including IMMP1L, CWC27, CACNG2, VMP1, ME2-DT, CTNNA3, LINC01137, TENM4, CDH13 and RAB6A.

Moreover, a high log-2 ratio was observed for the CWC27 gene in CCA patients in the non-response group, while a low signal was seen in the response group. In addition, CDH13 and TENM4 exhibited higher signals in patients with no response to GEM compared to those with a response (Fig. 3).

Correlation between genomics of drug sensitivity in cancer (GDSC), cancer therapeutics response portal (CTRP) drug sensitivity and mRNA expression

The correlation between GDSC, CTRP drug sensitivity and mRNA expression profile of notable genes including IMMP1L, CWC27, CACNG2, VMP1, ME2-DT, CTNNA3, LINC01137, TENM4, CDH13 and RAB6A, was investigated. The results showed 7 genes were involved and correlated with drug sensitivity. Pearson’s correlation analysis of the GDSC database (Additional File 2) revealed that drug sensitivity to dabrafenib, PLX4720, RDEA119, trametinib, selumetinib, (5Z)-7-oxozeaenol, CI-1040, SB590885 was negatively correlated with TRPV2 and TRPV4 expression, based on IC50 values. Although drug resistance toward afatinib and lapatinib was positively associated with TRPV2 expression, drug sensitivity to TG101348, UNC0638, XMD14-99 I-BET-762, JW-7-24-1, KIN001-260, masitinib, methotrexate, NG-25, PHA-793,887, QL-XI-92, TAK-715, TL-1-85, TPCA-1, XMD13-2, AT-7519, and KIN001-102 was positively correlated with TRPV4 expression (Fig. 4A). In the CTRP database (Additional File 3), drug sensitivity to KPT185, OSI-930, methylstat, KU-60,019, ML311, NSC48300, indisulam, MK-1775, PF-3,758,309, belinostat, linifanib, tivantinib, valdecoxib, PHA-793,887, dinaciclib, and pevonedistat was negatively correlated with the expression of TRPV1 and TRPV2, based on IC50 values. However, drug resistance analysis revealed that most of these drugs were positively associated with TRPV4 expression, based on IC50 values (Fig. 4B).

Drug sensitivity analysis of 7 related genes. (A) The gene set drug sensitivity analysis from Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) IC50 drug data. (B) The gene set drug sensitivity analysis from Cancer Therapeutics Response Portal (CTRP) IC50 drug data. The Pearson’s correlation indicates the correlation between gene expression and drug sensitivity. Blue bubbles represent negative correlations, and red bubbles represent positive correlations; the deeper the color, the higher the correlation. The bubble size was positively correlated with the FDR significance. The black outline indicates an FDR < 0.05. Only the top 30 ranked drugs were included.

Discussion

Cytogenetic techniques have greatly enhanced the cytogenetic analysis of hematopoietic and solid tumors and are rapidly gaining ground in clinical cytogenetic diagnostics. Interestingly, this has inspired an era of new FISH-based technologies for cytogenetic analysis such as multiplex FISH, spectral karyotyping, and comparative genomic hybridization or chromosome microarray (CMA). CMA detects microscopic aberrations with high sensitivity. It has clinical significance for both micro-deletion and amplification. Therefore, CMA is a suitable technique in this study. Representative G-banded karyotypes of CCA cell lines such as KKU-213 A, KKU-213B and KKU-213 C cell lines showed aneuploidy with chromosome abnormalities and marker chromosomes (mar). KKU-213 A karyotype reveals 56,XX, − 2, +3, + 5, +6, + 8, +9, + 15, +17, + 20, −21, +mar, while KKU-213B karyotype demonstrates 92,XX, + 1, +3, + 4, +5, + 6, +7, + 8, +9, + 10, + 12, +13, + 14, +15, + 16, +17, + 18, +19, + 20, +21, + 22, + mar. KKU-213 C karyotype shows 78, +X, + 4, + 5, +6, + 7, +8, + 9, +10, + 11, +17, + 18, +19, + 20, + mar [11]. In addition, array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) analysis on all different TAA-induced phases of rat tissues showed a certain pattern: gains on chromosomes 2q45 and Xq22, and a loss on chromosome 12p12, were identified in early stage, which involves the gene TNNI3K. In addition, 16 genes and 3 loci were associated with rapid tumor progression and the JAK-STAT signaling pathway was highly correlated with late-stage CCA [8]. Importantly, the overall genomic profile of iCCA showed many alterations with higher rates of deletion. Exclusive deletion of genomic areas was seen at 1p, 3p and 14q. Amplification of genomic areas was demonstrated at 1q, 7p, 7q and 8q. A clustering analysis identified three tumor groups: the first group was characterized by a loss of copy number on chromosome 1p and a gain of copy number on chromosome 7p; the second group was characterized by losses of copy number on chromosomes 1p and 3p without a gain of copy number on chromosome 7p; and the last group was characterized predominantly by a low number of copy number alterations (CNAs). In 2018, Ruben Jansen and co-workers identified gains on chromosome 19q as new CNA in 37 tumors and 14 matched LNM, using whole- genome array comparative genomic hybridization. Moreover, tumors with LNM (N1) had more alterations, including gains on chromosomes 3p, 4q, 5p, and 13q, and losses on chromosomes 17p and 20p. LNM shared most alterations with their matched tumors (86%), but 79% developed new isolated gains, including 12q14 (36%) and 1p13, 2p23, 7p22, 7q11, 11q12, 13q13, and 14q12 (> 20%). Interestingly, unsupervised clustering revealed a poor prognosis subclass with significantly increased alterations associated with tumor differentiation and survival. This suggests that a novel subclass with increased CNAs and poor tumor differentiation was significantly correlated with survival15. Furthermore, an array comparative genomic hybridization study of 23 CCA tissues, comprising 10 patients with eCCA and 13 patients with iCCA, demonstrated several common alterations between iCCA and eCCA tumor samples, including a gain on chromosome 2q37.3. In contrast, there was gain of Xp and loss of 3p, 11q11, 14q, 16q, Yp and Yq in iCCA, whereas there was gain of 16p25.3 and loss of 3q26.1, 6p25.3–22.3, 12p13.31, 17p, 18q and Yp in eCCA. A genomic model was developed comprising four chromosomal regions that seemed to enable the distinction between iCCA and eCCA with an accuracy of 71.43% (95% CI 43–100%). Survival analysis revealed that eCCA patients had a shorter average survival (8 months) than iCCA patients14. Therefore, the power of this genomic model should be evaluated in other CCA populations. Understanding chromosomal alterations in CCA may advance personalized medicine, including predicting gemcitabine (GEM) response, a standard chemotherapy for this disease. The limited clinical utility of existing molecular markers for predicting gemcitabine response in CCA highlights the need for novel biomarkers. Our study addresses this gap by identifying a novel chromosomal pattern using a chromosome microarray approach, and used the gene set of a novel chromosome pattern to validate in independent datasets (GDSC and CTRP)16. This focus on stable, easily detectable chromosomal alterations offers a promising avenue for clinical translation. Although further research, including larger cohort validation and functional studies, is needed to fully understand the mechanisms involved and translate these findings into clinical practice, this work represents a significant advance in personalized CCA treatment.

In this study, we selected a CCA tumor from a patient who underwent hepatectomy as the primary treatment. To assess GEM response, we employed HDRA, a technique previously shown to be effective in predicting clinical response in ovarian cancer, with a sensitivity and specificity of 88% and 86%, respectively17. Hence, HDRA is a suitable method for evaluating chemotherapy response in our study. We identified four cases with a response to GEM and six cases with non-response. Notably, one patient exhibited non-responsiveness to both HDRA and clinical data. However, due to the limited sample size, statistical analysis was not feasible and did not reach statistical significance. We found that fresh frozen CCA tissues in each patient have a variation of copy number variant. This is useful for using mathematical tools to help to classify the copy number variant information. Metaboanalyst, the web-based program using coding platform R, was used in this study to classify the log 2 ratio of samples into 2 groups by unsupervised model (e.g. PCA) and supervised model (e.g. OPLS-DA). Metaboanalyst consists of a wide array of commonly used statistical and machine learning methods used for principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal partial least squares-discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA), as well as clustering and heatmap. It is not only useful for metabolomic analysis, but also significance analysis of microarrays18 and other analysis such as protein expression19,20. These findings demonstrated that the log 2 ratio of copy number variants in each sample could be classified into 2 groups by PCA and OPLS-DA. These data were separated using heatmap analysis into 2 sets including response and no response to GEM. Thirteen loci were sorted into these 2 groups, including 4q32.1, 5q12.3, 10q21.3, 11p11.2, 11q14.2, 16p11.2, 17q22, 21q21.3 and 22q12.3 in the response group, and 2q37.2, 11q14.1, 16q22.3 and 16q23.3 in the non-response group.

Additionally, public databases show long intergenic non-protein coding RNA 1173 at location 2q37.2. Near this region, losses at 2q36.3-2q37.1 were associated with relapse in Wilms tumours21. In prostate cancer, some common genomic alterations included loss of 6q15, 8p21.3-8p21.2, 10q23.2-10q23.31, 16q22.3, 16q23.2-16q23.3 and 21q22.2-21q22.3, and gain of 8q24.3. Moreover, loss of HP locus (16q22.1) and CTRB locus (16q22.3-q23.2) in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) were correlated with poor differentiation, while these loci were not detected in the early stage22. In contrast, these findings reported a low log 2 ratio in the non-response group in some locations (e.g. 5q12.3). It has previously been reported that a new susceptibility locus at 5q12.3, consisting of CWC27 (rs2042329), was detected in bladder cancer in a study using GWAS to investigate a Chinese cohort. Moreover, a risk allele of rs2042329 was associated with significantly increased CWC27 expression at both mRNA and protein levels in bladder cancer tissues. Functional analysis of CWC27 also showed it can induce cell proliferation and inhibit apoptosis23. The splicing of pre-mRNA involves the removal of non-coding introns and the joining of exons to create mature mRNA molecules which can be translated into proteins. This process is facilitated by a molecular complex known as the spliceosome24. Mutations in genes encoding spliceosome proteins can lead to the development of various diseases25. Among these genes is CWC27, a spliceosome-associated cyclophilin involved in the formation and function of the spliceosome, which is located on chromosome 5q12.3. The mRNA and protein expression levels of CWC27 were found to be upregulated in bladder tumors, showing a significant association with bladder cancer recurrence23. Moreover, mutation in the CWC27 gene causes retinal degeneration and other developmental defects26. Knockdown experiments targeting CWC27 in immortalized retinal pigment epithelial cells demonstrate a significant impact on up-regulated genes associated with inflammation27. Correspondingly, in this study, we observed a high log-2 ratio in the CWC27 gene in CCA patients responding to GEM, while a low signal was seen in the resistant group. However, direct evidence linking CWC27 to GEM response remains absent. Plausible mechanisms underlying this phenomenon may be influenced by alteration in CWC27 expression, which could induce aberrant splicing of inflammation-related genes. Ultimately, this may affect the cellular response such as cell cycle arrest and DNA repair which lead to increase chemotherapeutic response in CCA patients.

Previously, 16q22.3 composed of the RAB6A gene, which encodes the RAB6A protein, a member of RAS oncogene family. Furthermore, 16q23.3 contains the CDH13 gene, which encodes cadherin 13 protein. In numerous cancer types, CDH13 (cadherin 13), also known as T-cadherin, is frequently silenced due to promoter methylation28,29. Conversely, CDH13 mRNA levels are elevated in breast cancer cells compared to normal cells, and this upregulation is associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer patients30. Furthermore, CDH13 overexpression has been detected in intratumoral endothelial cells and is implicated in the invasion and migration of hepatocellular carcinoma31. Additionally, CDH13 has been reported as a modulator of angiogenesis by potentiating factors such as VEGF32. These findings suggest that CDH13 may play a vital role in angiogenesis, tumor invasion, and metastasis. Correspondingly, our study demonstrates a high signal of CDH13 associated with lack of response to GEM. Collectively, these observations suggest that upregulation of CDH13 may facilitate tumor angiogenesis, cancer cell growth, and metastasis, eventually leading to the development of chemotherapy resistance.

Apart from the high levels of CDH13 expression detected in CCA patients resistant to GEM, elevated levels of TENM4 located at 11q14.1 were also noted. TENM4, a member of the teneurin protein family, plays a key role in neuronal differentiation through focal adhesion kinase (FAK) signaling33. Importantly, TENM4 plays crucial roles for cancer-related regulatory networks, and potentially participates in drug resistance34. Much like the present study, gains to chromosome 11 at q14.1 were demonstrated in previous reports and showed a significant difference between early and advanced gastric cancers, with a higher likelihood in advanced gastric cancer35. Moreover, an association between higher USP35 (located in 11q14.1) expression and poor survival was observed in ER + breast cancer36. Overexpression of TENM4 has been found to be correlated with poor prognosis in different types of cancers, including endometrial, liver, renal and stomach cancers37. Furthermore, inhibiting TENM4 in mammary cancer cells significantly impairs tumorsphere-forming ability, migratory capacity and FAK phosphorylation38. Elevated expression of FAK has been reported to be an important feature of cells with a stem-like phenotype39. Interestingly, upregulation of FAK in GEM resistant CCA cell lines has been shown to contribute to CCA progression40. These findings collectively suggest that overexpression of TENM4 might contribute to the development of chemoresistance in CCA by inducing cancer stem cell properties in tumor initiating cells. In addition, the study of STRING and GEPIA suggests that CDH13 and TENM4 may contribute to GEM resistance in CCA. STRING analysis revealed interactions between these genes and key drug resistance pathways, such as Akt and mTOR. GEPIA database analysis further supported these findings, showing a positive correlation between CDH13 and both Akt and DCK (a marker of GEM resistance) (Additional file 4). Future studies are needed to validate these findings and elucidate the specific mechanisms underlying the role of CDH13 and TENM4 in GEM resistance. Similar to previous studies in eCCA, our findings indicate a gain of chromosome 16q14. Moreover, our results align with those from non-small-cell lung cancer, identifying chromosome 11p15.5 as a potential target for GEM resistance due to its role in ribonucleotide reductase gene expression41. Previous research on urothelial carcinoma of the bladder has revealed associations between specific chromosomal alterations and tumor behavior. These alterations include losses on chromosomes 10q, 16q, and 22q, as well as gains on chromosomes 10p, 11q, 12p, 19p, and 19q. Additionally, copy number alterations on various chromosomes, including 16p, 2q, 4q, 11p, 10q, 13q, 14q, 16q, and 19p, have been associated with TP53 mutations42. While our study aligns with some of these previous findings, further research is needed to fully elucidate the specific genetic mechanisms underlying GEM resistance in CCA and to identify potential therapeutic targets such as those on chromosome 16q.

Chromosome microarray analysis of CCA tissues may serve as a predictive biomarker panel for GEM therapy response. The non-response group had more chromosomal abnormalities than the response group. Interestingly, the signature patterns of chromosomes analyzed by heatmap analysis is shown mostly in three related genes, including CWC27, TENM4 and CDH13. Our findings suggest that a panel of three genes, CDH13, TENM4, and CWC27, can be used to predict GEM response in patients with CCA. Specifically, the log2 ratio of these genes differs between responders and non-responders to GEM. Responders tend to have a higher log2 ratio for CWC27, while non-responders tend to have higher log2 ratios for CDH13 and TENM4. Consistent with public data analysis, our results suggest that chromosomal patterns, specifically those involving CDH13, TENM4, VMP1, and RAB6A, can be used as predictive biomarkers to guide personalized treatment strategies for CCA patients. These findings of genetics alteration affect GEM response in CCA. These alterations may not only predict drug response but also help guide the selection of more suitable therapy. This personalized approach may improve survival outcomes for CCA patients.

While associations between chromosomal abnormalities and chemotherapy response have been observed across a range of cancers, the precise mechanisms by which these aberrations influence gemcitabine efficacy in Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) remain largely unclear. This knowledge gap is significant, as it hinders our ability to predict patient responses and tailor treatment strategies. Specifically, the interplay between specific chromosomal alterations and the pathways involved in gemcitabine metabolism and drug resistance in CCA requires further investigation. Understanding these interactions is crucial for identifying potential biomarkers that could predict gemcitabine response and ultimately improve clinical outcomes for CCA patients. Our study suggests that patterns of chromosomal abnormalities and gene mutations may influence gemcitabine response. However, limitations including sample size and tumor specimen inclusion criteria necessitate further investigation. To address these limitations, we conducted validation analyses using publicly available datasets. Analyzing chromosomal abnormalities in tumor tissue from CCA patients may aid in selecting the most appropriate treatment. A limitation of this study is the small sample size (n = 5 per group), which resulted from our strict inclusion criterion of tumors ≥ 10 cm. This criterion was implemented to minimize the influence of tumor size on treatment response with HDRA. While this exploratory pilot study uncovered a significant association between a chromosomal pattern and gemcitabine response, further validation in larger, more diverse cohorts, including tumors of all sizes, is crucial. Further validation in larger sample sizes and prospective clinical trials is necessary to fully assess the translational potential and clinical utility of these biomarkers. Therefore, further consideration of the different log 2 ratios and other techniques to validate the multivariate analysis would be useful in predicting GEM response in individual cases of CCA patients in the future. Furthermore, the inherent heterogeneity of CCA subtypes may confound chromosomal abnormality analysis; increasing sample size and performing subtype-specific analyses could elucidate specific genetic patterns. The limitations of chromosomal microarray (CMA) in detecting insertions and translocations warrant the integration of conventional cytogenetics, such as G-banding, using paired samples to provide a more comprehensive characterization of chromosomal aberrations. Prospectively, CCA research, especially regarding chromosome alterations, holds significant promise for improved diagnostics and therapies. Our work will prioritize validating our identified chromosomal pattern in larger studies and developing a clinically applicable assay. Subsequent clinical trials will evaluate the impact of biomarker-guided treatment decisions on patient outcomes. Investigating the functional roles of these alterations may uncover novel therapeutic targets. In the long term, we expect that high-resolution genetic testing will further refine personalized chemotherapy selection, leading to more effective and personalized CCA treatments. This vision aligns perfectly with our anticipation that in the next five years, we will see a significant transformation in the clinical management of cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) driven by the development and implementation of our findings. We envision a paradigm shift towards personalized medicine, where the identification of specific chromosomal alterations and candidate gene expression levels will become a standard practice for predicting gemcitabine response.

Conclusion

Based on our results, the signal of candidate genes may serve as predictors of gemcitabine response in CCA patients. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying these expression changes and gemcitabine response need to be further investigated in depth. We propose that our findings may contribute to the development of biomarkers for predicting gemcitabine response in personalized CCA medicine and inform the identification of novel targeted therapies.

Methods

CCA frozen tissues

Liver tissue from ten patients with diagnosed Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) was collected as frozen tissue from the Pathology Laboratory in Srinagarind Hospital, Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine and Cholangiocarcinoma research institute (CARI), Khon Kaen University. Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Ethics Committee for Human Research, Khon Kaen University (HE641237).

Histoculture drug response assay (HDRA)

CCA tissues (10 mg) were cultured in RPMI-1640 media, both with and without 1000 µg/ml gemcitabine. After a 4-day incubation on sponge gel, cell viability was assessed using an MTT assay. Chemotherapy efficacy was evaluated by calculating the percentage inhibition rate (% IR) based on MTT assay absorbance. A previous study determined a cut-off value of 38.46% inhibition rate to differentiate between gemcitabine-responsive and non-responsive CCA tumor tissues43. Samples were categorized accordingly into two groups: response and non-response.

Genomic DNA extraction

CCA tissues (≤ 25 mg) were cut into small pieces and placed into a 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube. 180 µl of Buffer ATL and 20 µl of Proteinase K were added, then mixed by vortexing and incubated at 56 °C until completely lysed (1–3 h). Then, 200 µl of Buffer was added, with incubation at 70 °C for 10 min and subsequent addition of 200 µl of ethanol (96–100%). After this, the mixture was pipetted into a Mini spin column and centrifuged at 6000 x g (8000 rpm) for 1 min. Discard the flow-through and collection tube. The Mini spin column was placed in a new collection tube with 500 µl of Buffer, then centrifuged at 6000 x g (8000 rpm) for 1 min. Following this, the flow-through and collection tube were again discarded. The Mini spin column was placed in a new 2 ml collection tube with 500 µl of Buffer again. The centrifuge was run at full speed (20,000 x g; 14,000 rpm) for 3 min before flow-through and collection tube discardment. The Mini spin column was then placed in a new 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube with distilled water and incubated at room temperature for 1 min, before centrifugation at 6000 x g (8000 rpm) for 1 min to elute the genomic DNA.

Chromosome microarray and analysis

Chromosome microarray using 750 K CytoScan Assay obtains the whole genome copy number and SNP information with 750,000 markers for copy number analysis, including 200,000 SNP and 550,000 non-polymorphic probes. In summary, for each sample tissue DNA 8 steps were performed, including digestion, ligation, PCR amplification of DNA fragment, purification, quantitation, fragmentation, labeling and hybridization on a microarray chip. After that, the microarray chip in each sample was washed, stained, and scanned. The samples were labeled with fluorescent probe and hybridized on the microarray chips. The array slides were washed and subsequently scanned using the Microarray Scanner. The generated data from the scanned images were extracted with CytoScan. CytoScan® Array CEL files were processed and analyzed in the Affymetrix Chromosome Analysis Suite Software (ChAS), which enables to detect and analyze relevant chromosomal aberrations when used with high resolution CytoScan® 750 K Arrays. Chromosome data was analyzed using the ChAS program. Chromosome abnormalities were identified in regions exhibiting a copy number gain or loss of at least 100 kilobase pairs (kbp) and involving 50 or more markers. Log2 ratio values represent the level of copy number variation. A log2 ratio below 0 indicates a loss, while above 0 indicates a gain. Designed with input from leading cytogenetics experts, the highly intuitive, state-of-the-art ChAS Software is tailored for data visualization, customized cytogenetic research analysis, and genotype reporting.

Drug sensitivity analysis of candidate gene panel in pan-cancer

The public database of mRNA expression in Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) and Cancer Therapeutics Response Portal (CTRP) drug sensitivity was used to evaluate the correlation of candidate gene panel expression (IMMP1L, CWC27, CACNG2, VMP1, ME2-DT, CTNNA3, LINC01137, TENM4, CDH13 and RAB6A) and drug sensitivity16. (https://guolab.wchscu.cn/GSCA/#/).

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as a graph and analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 19.0 software. The Fisher Exact test was used to evaluate the association of each region of chromosome and clinico-pathological data of the CCA patients. The chromosome data for each probe marker was analyzed using multivariate statistical analysis techniques, including principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal partial least squares discrimination analysis (OPLS-DA), to differentiate the signal of log2 ratios. Hierarchical clustering heatmap analysis was performed using MetaboAnalyst 5.0 to visualize the correlation between chromosome data. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

All data analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files are available in the additional files.

Abbreviations

- aCGH:

-

Array comparative genomic hybridization

- CCA:

-

Cholangiocarcinoma

- CDH13:

-

Cadherin 13

- CIS:

-

Cisplatin

- CMA:

-

Chromosome microarray

- CNA:

-

Copy number alteration

- CTRP:

-

Cancer therapeutics response portal

- eCCA:

-

Extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

- FISH:

-

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

- GDSC:

-

Genomics of drug sensitivity in cancer

- GEM:

-

Gemcitabine

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- iCCA:

-

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

- LOH:

-

Loss of heterozygosity

- OPLS-DA:

-

Orthogonal partial least squares-discriminant analysis

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

References

Blechacz, B. & Gores, G. J. Cholangiocarcinoma: Advances in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Hepatology 48, 308–321. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.22310 (2008).

Nakeeb, A. et al. Cholangiocarcinoma. A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors. Ann. Surg. 224, 463–473. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-199610000-00005 (1996). discussion 473 – 465.

Khan, S. A., Miras, A., Pelling, M. & Taylor-Robinson, S. D. Cholangiocarcinoma and its management. Gut 56, 1755–1756. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2007.138859 (2007).

Vatanasapt, V., Sriamporn, S. & Vatanasapt, P. Cancer control in Thailand. Jpn J. Clin. Oncol. 32 Suppl, 82–91. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hye134 (2002).

Valle, J. et al. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl. J. Med. 362, 1273–1281. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0908721 (2010).

Wirasorn, K. et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy in resectable cholangiocarcinoma patients. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 28, 1885–1891. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.12321 (2013).

Brandi, G. & Rizzo, A. I. D. H. Inhibitors and immunotherapy for biliary tract cancer: A marriage of convenience? 23, 10869 (2022).

Rizzo, A. et al. Anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies in advanced biliary tract cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vivo 34, 479–488. https://doi.org/10.21873/invivo.11798 (2020).

Rizzo, A. et al. Second-line treatment in advanced biliary tract cancer: Today and tomorrow. Anticancer Res. 40, 3013–3030. https://doi.org/10.21873/anticanres.14282 (2020).

Oh, D. Y. et al. Durvalumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin in advanced biliary tract cancer. NEJM Evid. 1, EVIDoa2200015. https://doi.org/10.1056/EVIDoa2200015 (2022).

Ricci, A. D., Rizzo, A. & Brandi, G. The DNA damage repair (DDR) pathway in biliary tract cancer (BTC): A new Pandora’s box? ESMO Open 5, e001042. https://doi.org/10.1136/esmoopen-2020-001042 (2020).

Jakubowski, C. D. & Azad, N. S. Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in biliary tract cancer (cholangiocarcinoma). Chin. Clin. Oncol. 9. https://doi.org/10.21037/cco.2019.12.10 (2020).

Yeh, C. N. et al. Over-expression of TNNI3K is associated with early-stage carcinogenesis of cholangiocarcinoma. Mol. Carcinog. 58, 270–278. https://doi.org/10.1002/mc.22925 (2019).

Jansen, R. et al. ACGH detects distinct genomic alterations of primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas and matched lymph node metastases and identifies a poor prognosis subclass. Sci. Rep. 8, 10637. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-28941-6 (2018).

Tavares, I. et al. Development of a genomic predictive model for cholangiocarcinoma using copy number alteration data. J. Clin. Pathol. https://doi.org/10.1136/jclinpath-2020-207346 (2021).

Liu, C. J. et al. GSCALite: a web server for gene set cancer analysis. Bioinformatics 34, 3771–3772. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty411%J (2018).

Hoffman, R. M., Jung, P. S., Kim, M. B. & Nam, J. H. Prospective clinical correlation of the histoculture drug response assay for ovarian cancer. Methods Mol. Biol. 1760, 73–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-7745-1_8 (2018).

Xia, J., Psychogios, N., Young, N. & Wishart, D. S. MetaboAnalyst: A web server for metabolomic data analysis and interpretation. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, W652–660. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkp356 (2009).

Padthaisong, S. et al. A panel of protein kinase high expression is associated with postoperative recurrence in cholangiocarcinoma. BMC Cancer 20, 154. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-6655-4 (2020).

Padthaisong, S. et al. Integration of global metabolomics and lipidomics approaches reveals the molecular mechanisms and the potential biomarkers for postoperative recurrence in early-stage cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Metab. 9, 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40170-021-00266-5 (2021).

Natrajan, R. et al. Array CGH profiling of favourable histology Wilms tumours reveals novel gains and losses associated with relapse. J. Pathol. 210, 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.2021 (2006).

Tsuda, H. et al. Allele loss on chromosome 16 associated with progression of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 87, 6791–6794. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.87.17.6791 (1990).

Wang, M. et al. Genome-wide association study of bladder cancer in a Chinese cohort reveals a new susceptibility locus at 5q12.3. Cancer Res. 76, 3277–3284. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2564 (2016).

Bertrand, R. E. et al. Cwc27, associated with retinal degeneration, functions as a splicing factor in vivo. Hum. Mol. Genet. 31, 1278–1292. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddab319 (2022).

Griffin, C. & Saint-Jeannet, J. P. Spliceosomopathies diseases and mechanisms. Dev. Dyn. 249, 1038–1046. https://doi.org/10.1002/dvdy.214 (2020).

Xu, M. et al. Mutations in the spliceosome component CWC27 cause retinal degeneration with or without additional developmental anomalies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 100, 592–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.02.008 (2017).

Busetto, V. et al. Structural and functional insights into CWC27/CWC22 heterodimer linking the exon junction complex to spliceosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 5670–5683. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa267 (2020).

Berx, G. & van Roy, F. Involvement of members of the Cadherin superfamily in cancer. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 1, a003129. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a003129 (2009).

Zheng, W. et al. Multi-omics analysis of tumor angiogenesis characteristics and potential epigenetic regulation mechanisms in renal clear cell carcinoma. Cell. Commun. Signal. 19, 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12964-021-00728-9 (2021).

Ku, S. C. et al. Comprehensive analysis of prognostic significance of Cadherin (CDH) gene family in breast cancer. Aging (Albany NY) 14, 8498–8567. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.204357 (2022).

Riou, P. et al. Expression of T-cadherin in tumor cells influences invasive potential of human hepatocellular carcinoma. FASEB J. 20, 2291–2301. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.06-6085com (2006).

Philippova, M. et al. Atypical GPI-anchored T-cadherin stimulates angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc Biol. 26, 2222–2230. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.ATV.0000238356.20565.92 (2006).

Peppino, G. et al. Teneurins: Role in cancer and potential role as diagnostic biomarkers and targets for therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22052321 (2021).

Ziegler, A., Corvalan, A., Roa, I., Branes, J. A. & Wollscheid, B. Teneurin protein family: An emerging role in human tumorigenesis and drug resistance. Cancer Lett. 326, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2012.07.021 (2012).

Arakawa, N. et al. Genome-wide analysis of DNA copy number alterations in early and advanced gastric cancers. Mol. Carcinog. 56, 527–537. https://doi.org/10.1002/mc.22514 (2017).

Cao, J. et al. USP35, regulated by Estrogen and AKT, promotes breast tumorigenesis by stabilizing and enhancing transcriptional activity of Estrogen receptor alpha. Cell. Death Dis. 12, 619. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-021-03904-4 (2021).

Rebolledo-Jaramillo, B. & Ziegler, A. Teneurins: An integrative molecular, functional, and biomedical overview of their role in cancer. Front. Neurosci. 12, 937. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2018.00937 (2018).

Ruiu, R. et al. Identification of TENM4 as a novel cancer stem cell-associated molecule and potential target in triple negative breast cancer. Cancers (Basel) 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13040894 (2021).

Sulzmaier, F. J., Jean, C. & Schlaepfer, D. D. FAK in cancer: mechanistic findings and clinical applications. Nat. Rev. Cancer 14, 598–610. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3792 (2014).

Wattanawongdon, W. et al. Establishment and characterization of gemcitabine-resistant human cholangiocarcinoma cell lines with multidrug resistance and enhanced invasiveness. Int. J. Oncol. 47, 398–410. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2015.3019 (2015).

Rosell, R. et al. Novel approaches in the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncol. (Williston Park) 15, 52–60 (2001).

Hurst, C. D., Platt, F. M., Taylor, C. F. & Knowles, M. A. Novel tumor subgroups of urothelial carcinoma of the bladder defined by integrated genomic analysis. Clin. Cancer Res. 18, 5865–5877. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1807 (2012).

Suksawat, M. et al. In vitro and molecular chemosensitivity in human cholangiocarcinoma tissues. PLoS One 14, e0222140. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222140 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NSRF under the Basic Research Fund of Khon Kaen University through Cholangiocarcinoma Research Institute. We would like to acknowledge Cholangiocarcinoma Research Institute (CARI), Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand to support the patient information and tissue samples. We would like to acknowledge Cytogenetics Laboratory at Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand to support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, MT and SW; formal analysis, ST, SW, MT, YC and PK; funding acquisition, MT; investigation, ST, SW, RD, MS, AT, NA, PS, CP and MT; supervision, WL and MT; writing—original draft, MT, SW and ST; writing—review and editing, RD, SW, PK, AT, NA, TC, HS and MT. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The methods used in this study follow the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and ICH Good Clinical Practice (ICH GCP) guidelines. This study was approved by The Ethics Committee for Human Research, Khon Kaen University, Thailand and signed informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Techa-ay, S., Watcharadetwittaya, S., Deenonpoe, R. et al. Identifying a unique chromosomal pattern to predict the gemcitabine response in patients with cholangiocarcinoma. Sci Rep 15, 11984 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96442-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96442-4