Abstract

Realization of asymmetric transmission (AT) effect in metamaterial has drawn great interest in the past decade years since it indicates broad applications such as isolators and chiral polarization transistors which are highly demanded in various areas. However, most realization of AT is through the manipulation of electric field in chiral metamaterial, which limits the applications in the regimes requiring magnetic responses. In this article, we propose a metamaterial with chiral structure composed of connected metal loops placed on orthogonal directions, where the response orthogonal to the magnetic field of incident electromagnetic wave can be generated. Such manipulation of magnetic field is quantified with the equivalent permeability tensor of the metamaterial. The presented material exhibits AT characteristics of linear polarized electromagnetic wave sensitive to both polarization directions and propagation directions. Our work provides a new approach for AT, which has potential application of polarization sensitive devices, such as polarization rotators and circular polarizers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metamaterials are artificially engineered periodic structures designed to achieve various of electromagnetic properties such as negative refractive index and anisotropy as well as enabling unprecedented control over electromagnetic waves1,2,3,4,5,6. Thus, metamaterials offer a broad array of potential applications from sensing and imaging to stealth technology7,8,9,10,11,12. Among various types of metamaterials, magnetic-response structures hold a distinctive advantage since they can employ 3D ring-like elements that concentrate magnetic flux within the vertical dimension of the normal directions of the metamaterials13,14,15,16,17. Such designs allow for achieving more compact devices and richer functionalities. Although this approach adds complexity to fabrication, it provides a versatile platform for integrating multiple layers or functionalities in a smaller space, thereby pushing the limits of miniaturization and device performance.

Among the phenomenon of particular interest in the study of metamaterials, asymmetric transmission (AT) is a unique one, known as the asymmetric effect sensitive to the propagation directions or polarization directions of electromagnetic waves18,19,20,21. This effect resembles the Faraday effect22,23,24,25,26 but can be realized in metamaterials without applying a static bias magnetic field. Since such asymmetric responses expand the range of wave control, enabling new device concepts like one-way waveguides, isolators, and novel polarization manipulators, a great number of researches have been conducted on the asymmetry in metamaterials in the past decade years27,28,29,30,31. Various of structures are designed to realize AT, including single layer and multi-layers, planar and 3D structures32,33,34,35,36. Due to the lack of proper structure design to obtain magnetic flux and generate magnetic response to the incident electromagnetic waves, most of the researches achieve AT by the manipulation of electric field without manipulation of magnetic field. Studies are urgently demanded for realizing AT effect on magnetic-response based metamaterial, which will provide a new approach for the next-generation integrated systems.

In this article, we demonstrate a new magnetic-response metamaterial that contains interconnected orthogonal loops. In contrast to the conventional designs with simple loop arrangements, our structure features conductive pathways linking loops oriented along different axes to manipulate magnetic responses in orthogonal directions, a configuration that has not been previously explored. Here, we theoretically analyzed the presented structures and obtain each term of the equivalent permeability tensor to quantify the manipulation of magnetic responses. A prototype is designed and fabricated to experimentally verify the analysis and we systemically study the dimensional influence on the operating frequencies. Then, we demonstrate the realization of AT based on our design. We comprehensively study AT effect with different incident conditions of waves possessing different propagation directions or polarization directions. This advancement not only fills a gap in our understanding of three-dimensional magnetically resonant architectures but also paves the way for integrating these novel features into compact, multifunctional electromagnetic devices. The ability to realize and systematically analyze these non-diagonal terms of the equivalent permeability underscores the importance of our approach, marking a significant step forward in pushing the frontier of magnetic metamaterial research.

Theoretical analysis

The presented metamaterial is composed of periodic structures extending along x and y directions. The periodic unit contains two pairs of connected metal loops, where each pair has two loops placing on the orthogonal directions. Such configuration could generate the orthogonal magnetic response to the excitation magnetic field through the conduction of the induced current. Here we use the equivalent permeability tensor to represent the relation between excitation and response magnetic field, and it can quantify the manipulation of the material to the magnetic field. Considering a structure composed of periodical unit with periodic length \(\:a\), which contains a metal loop with radius of \(\:r\), resistivity per unit length of \(\:\delta\:\). The normal direction of the loop is parallel to x-axis. When \(\:{H}_{x}={H}_{0}\) with the \(\:{e}^{j\omega\:t}\) time dependence is applied on the whole structure, every other unit will have effects on the single unit. According to Pendry’s definition, the equivalent permeability of the periodic structure on x direction can be found as37:

where \(\:{B}_{ave}\) is the average magnetic induction intensity over the entire periodic unit, \(\:{H}_{ave}\) is the average magnetic intensity in the space out of the loop.

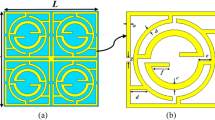

The equivalent permeability tensor of our presented material can be obtained similarly in the following way. Assuming two pairs of connected and orthogonally placed loops are named as loop1 and loop1’ as well as loop2 and loop2’, as shown in Fig. 1. In order to simplify the calculation, we ignore the width and thickness of the loops since its influence is negligible. Thus, we assume two loops with x-normal direction, named as loop1 and loop2, have radius of \(\:{r}_{1}\) and \(\:{r}_{2}\), respectively. The correspondingly connected loop1’ and loop2’ have radius of \(\:{r}_{2}\) and \(\:{r}_{1}\). The corresponding areas of loops are \(\:{S}_{1}=\pi\:{{r}_{1}}^{2}\) and \(\:{S}_{2}=\pi\:{{r}_{2}}^{2}\), and the length of the cube periodic unit is \(\:a\). Without loss of generality, we assume \(\:{H}_{0}\) is applied on x direction, and it generates induced current \(\:{J}_{1}\) on loop1 and \(\:{J}_{2}\) on loop2. This leads to an average induced magnetic intensity \(\:{H}_{in1}\) inside loop1, \(\:{H}_{in2}\) inside loop2 and \(\:{H}_{out}\) outside two loops. \(\:{H}_{in1}\), \(\:{H}_{in2}\) and \(\:{H}_{out}\) are all along the x direction, as shown in Fig. 1c. Meanwhile, the induced current which flows to the connected loop1’ and loop2’ also generates \(\:{H}_{in{1}^{{\prime\:}}}\) on loop1’, \(\:{H}_{in{2}^{{\prime\:}}}\) on loop2’ and \(\:{H}_{ou{t}^{{\prime\:}}}\), which are all along the y direction, as shown in Fig. 1(d).

Dimensions and magnetic field of the structure in different views. Loops with different normal directions are connected orthogonally at the split. (a) Dimensions of the structure in view Z; (b) Dimensions of the structure in view X; (c) Magnetic field on x direction in the periodic unit; (d) Magnetic field on y direction in the periodic unit.

Since the magnetic flux inside and outside each loop (\(\:{\text{l}\text{o}\text{o}\text{p}}_{\text{i}}\)) produced by induced current \(\:{J}_{i}\) are equal and the whole structure is composed of the same periodic units, the magnetic flux inside and outside the loop also equals in a single unit. Then we have the relations of

Applying the boundary condition of magnetic field, the induced current on the loops can be derived as

The total magnetic intensities inside loop1 and loop2 are \(\:{H}_{int1}={H}_{0}+{H}_{in1}\) and \(\:{H}_{int2}={H}_{0}+{H}_{in2}\), respectively. The impedance of the orthogonal connected loops is \(\:Z\). According to the Faraday’s Law of electromagnetic induction, we have

where \(\:{\phi\:}_{1}={\mu\:}_{0}{H}_{int1}\pi\:{r}_{1}^{2}\) and \(\:{\phi\:}_{2}={\mu\:}_{0}{H}_{int2}\pi\:{r}_{2}^{2}\) are the magnetic flux inside loop1 and loop2, respectively, \(\:{E}_{1}\) and \(\:{E}_{2}\) are the corresponding induced electromotive force. Substituting Eq. (2)(3) into Eq. (4) yields

According to the reference37, it’s straightforward to obtain that the average of magnetic induction intensity over the entire periodic unit is \(\:{B}_{avex}={\mu\:}_{0}{H}_{0}\) on x direction and \(\:{B}_{avey}=0\) on y direction, while the average magnetic intensity is \(\:{H}_{avex}={H}_{0}+{H}_{out}\) and \(\:{H}_{avey}={H}_{ou{t}^{{\prime\:}}}\). The response relation of the magnetic field can be shown as

Considering the topology of the double orthogonal connected loops, we have \(\:{\mu\:}_{xx}={\mu\:}_{yy}={\mu\:}_{1}\), \(\:{\mu\:}_{xy}={\mu\:}_{yx}={\mu\:}_{2}\)18. Thus, we are able to calculate the diagonal and off-diagonal terms of the equivalent permeability tensor. In order to simplify the calculation and verification, we assume the orthogonal connected loops having same radius, \(\:{r}_{1}={r}_{2}=r\), and \(\:{S}_{1}={S}_{2}=S\). The average magnetic intensity outside the loops can be solved as

where \(\:T=\frac{\frac{2}{{a}^{2}}}{\frac{Z}{{\mu\:}_{0}S\omega\:}j+\frac{{a}^{2}-S}{{a}^{2}}}\). In considering the matrix relation, \(\:{\mu\:}_{1}\) and \(\:{\mu\:}_{2}\) can be finally solved as

Based on the above theoretical analysis, a prototype with \(\:32\times\:32\) periodic units is designed and fabricated, as shown in Fig. 2. For the fabrication convenience, the circular metal loops in the above analysis have been replaced with rectangular loops. It should be noted that changing circular loops to rectangular loops will not significantly affect the magnetic response characteristics of the material, since it only varies \(\:S\) due to the changes of geometry.

Results and discussion

Permeability tensor

The results of experiment and simulation of the prototype are shown in Fig. 3a–d. The general trend of the experiment curve agrees with the simulation one, with a frequency deviation as small as 0.1 GHz, which proves that the presented structure has realized the permeability tensor with off-diagonal terms as the analysis expected. The small deviation between the simulated curve and measured curve can be attributed to the geometric difference between the experiment and simulation situation. In the simulation, there is an infinite periodic structure between two wave ports, but there are only finite periodic units of the prototype between two waveguide ports in the experiment. Besides, the fabrication imperfection of the prototype can also contribute to the frequency deviation.

In order to enable the presented material to meet the application requirement of different operating frequencies, we conduct a comprehensive analysis of spatial parameters’ influences on the resonant frequencies of our prototype via simulation to demonstrate the robustness of our design. Based on the prototype above, two models with different dimensional parameters are simulated respectively to investigate the effect of structure dimensions on resonant frequency. Firstly, we double both \(\:t\) and \(\:{t}_{1}\) to obtain a model with loop heights twice that of the prototype. Then, we double \(\:{d}_{1}\) to obtain a model with loop widths twice that of the prototype. The simulation results of permeability of two models are shown in Fig. 3e–h. The materials exhibit different resonant frequencies of the equivalent permeability under different dimensional parameters. Increasing the widths or the heights of the loops can both increase the loop area to achieve the effect of increasing the magnetic flux. Therefore, two models with the increased dimensional parameters possessed the similar resonant frequencies. This means even if the thickness or the periodic length is under limitation, the presented material can still meet the requirements of different operating frequencies by changing the parameters in other dimensions, which proves its flexible designability. Additionally, we further investigate the influences of elements density and dielectric loss on resonant properties of the metamaterial. The effects of elements density on properties of the complete material are evaluated by increasing the periodic unit length to change the distance between adjacent elements. Figure 4(a) shows that there is a slight shift of the resonant frequency as the unit length increases. Contrarily, the amplitude of permeability, which is represented by the normalized peak value of \(\:Re\left({\mu\:}_{1}\right)\), experiences a significant decrease. Without changing of the excitation magnetic field and metal structure, the decrease of permeability can be attributed to the decrease of induced magnetic flux density in the material, which is caused by the decrease of elements density. Another factor we explore is the dielectric loss of the medium. In simulation, the dielectric loss tangent of the medium board is adjusted from 0.002 to 0.02 with step of 0.002 to validate its effect on properties of the metamaterial. As shown in Fig. 4(b), the resonant frequency is barely influenced while amplitude of the permeability decreases as the dielectric loss increases. Based on the above analysis, smaller length between periodic units and medium with lower loss are preferred in the design to achieve better resonance characteristics.

Simulation and experiment results of permeability of prototype under different dimensional parameters. (a) Experiment results of \(\:{\mu\:}_{1}\) of the prototype, black and red curves represent real and imaginary part of \(\:{\mu\:}_{1}\) respectively; (b) Experiment results of \(\:{\mu\:}_{2}\) of the prototype, blue and green curves represent real and imaginary part of \(\:{\mu\:}_{2}\) respectively; (c, d) Simulation results of \(\:{\mu\:}_{1}\) and \(\:{\mu\:}_{2}\) of prototype; (e, f) Simulation results of model with twice the loop height of the prototype; (g, h) Simulation results of model with twice the loop width of the prototype.

Asymmetric transmission

In this section, we will analyze and discuss the asymmetric transmissions of electromagnetic waves in the presented metamaterials. The asymmetry of wave transmissions with different incident conditions are discussed. Specifically, we focus on linear polarized waves with opposite propagating directions and same polarization directions, as well as the linear polarized waves with same propagating directions and orthogonal polarization directions. Besides, the structure is modified to possess bi-anisotropy for further discussion.

The effect of elements density and dielectric loss on properties of the complete material. (a) The red curve represents the variation of resonant frequency with unit length which is corresponding to the left vertical axis. The resonant frequency exhibits slight frequency shift near 11.6 ~ 11.7 GHz. The blue curve represents the variation of normalized peak value of permeability with unit length which is corresponding to the right vertical axis. The amplitude of permeability attenuates as unit length increases; (b) The red curve represents the resonant frequency, which is nearly constant with dielectric loss tangent increasing. The blue curve represents the normalized peak value of permeability, which decreases significantly with dielectric loss tangent increasing.

We start with the discussion of the polarization variation of the incident waves during its propagation through the material. Since there are phase differences between the induced currents and the excitation magnetic fields according to the Faraday’s Law of electromagnetic induction, the magnetic fields generated by the induced current also have phase differences with the excitation magnetic fields. In the presented metamaterial, the induced currents generate magnetic responses orthogonal to the incident excitation magnetic fields, which make the magnetic fields of the outgoing waves through the material contain two orthogonal components with phase differences. Therefore, the linear polarized incident waves will turn into elliptical outgoing polarized waves after propagating through the presented material.

A model of the presented material is simulated of its transmission characteristics of linear polarized waves as shown in Fig. 5. We visualize the magnetic field at two chosen reference planes which are above and beneath the material respectively. Firstly, we plot the magnetic field in a complete period when an incident wave propagates through the material along -z direction. As shown in Fig. 5a, the black and red curves represent the x and y magnetic field components of the incident waves before reaching the material. The blue and green dotted curves are corresponding to the x and y magnetic field components of the outgoing waves after propagating through the material. The total magnetic field vector in a period from \(\:0\sim2\pi\:\) is shown in Fig. 5b, where the “upper” columns indicate the incident waves and the “lower” columns indicate the outgoing waves. Four specific moments are selected starting from \(\:\pi\:/4\:\)at a step of \(\:\pi\:/2\) to visually demonstrate the changes of the magnetic fields. It can be observed that the magnetic field has only x-direction component before the incident waves reaching the material, while it exhibits both x and y components after propagating through the material. In addition, the magnetic field direction beneath the material continuously rotates within a complete period. These results prove the conversion of linear polarized incident waves to the elliptical polarized outgoing waves through the material. Since the quantification and visualization of the magnetic field in the continuous period is rather difficult and inaccessible to our current measurement system, the analysis in this section only contains the simulation results.

To examine the transmission characteristics of linear polarized waves with opposite incident directions, we simulate incident waves in -z and + z directions where -z is the forward direction and + z is the backward direction. Both incident waves have the magnetic fields in x-direction and the same phases, which ensure the consistency of their incident conditions except only the propagating directions. Then, we obtain the magnetic field of the outgoing waves at a symmetrical position relative to the material. Rotation angle of the magnetic field, which is represented by \(\:{H}_{y}/{H}_{x}\), is measured correspondingly for these two waves in opposite directions, as shown in Fig. 5c. We can clearly identify that, for same incident conditions comparing, the rotation angles evolute in the exactly same way although these two waves have the opposite transmission directions. In other words, the polarization rotation of a wave propagating through the material will be reversed when the wave is in the opposite propagate direction. Therefore, the presented material is proved to exhibit AT effect with respect to the direction of wave propagation. Such effect can be mainly attributed to the interaction between the magnetic field of the incident waves and the chiral structure of the metamaterial. The manipulation of magnetic field in the material is mainly through the orthogonal metal loops with normal directions of x and y directions. Although the structure of the presented material is 3D, the chirality is mainly in x and y directions. For the observation from normal directions, the chiral structures possess senses of twist that are reversed when they are observed from the opposite sides. Based on the above observations, the presented material is proved to possess reversed polarization rotation effects for opposite propagating waves in normal incidence.

Variation of the magnetic field at different positions and conditions within a complete period. (a) Magnetic field components at positions above and beneath the material respectively. Black and red curves represent the x and y components of magnetic field above the material. Blue and green curves represent the x and y components of magnetic field beneath the material. (b) Magnetic field vector above and beneath the material at four moments within a period. (c) Comparison of the magnetic field rotation of two waves incident in opposite directions.

The presented materials show the characteristics of turning linear polarized waves into elliptical polarized waves. The polarization rotations of waves with different propagation directions have been proved to exhibit asymmetry. The following contents will discuss the asymmetry of transmissions of linear polarized waves with the same propagation directions but orthogonal polarization directions.

In the above analysis, two connected loops in the structures are assumed to have the same dimensions. When the incident magnetic field is set up, the magnitude of the induced current in the material is mainly determined by the areas where the magnetic flux is generated. In addition, the magnitude of the induced magnetic field is proportional to the areas and the induced current. Therefore, the presented materials possess the symmetry and reciprocity of magnetic response relations in x and y directions when the loops in the structures all have the same dimensions. Quantitively, this can be expressed as the permeability tensor which has the form \(\:{\mu\:}_{xx}={\mu\:}_{yy}\) and \(\:{\mu\:}_{xy}={\mu\:}_{yx}\).

In order to generate the asymmetric responses, we need to break the symmetry of the chiral structures, which is achieved by modifying the symmetric structures of the presented material. As shown in Fig. 6, the new loop1 has the same dimensions as loop2, while the loop1’ has the same dimensions as loop2’. The area of new loop1 and 2 is different to the area of loop1’ and loop2’ such that \(\:{S}_{1}\ne\:{S}_{2}\). Considering the length of the periodic unit is \(\:a\) and the thickness of the material is \(\:t\), this change results in the distinct magnetic flux in the orthogonal directions, and thus the magnetic response relations in x and y directions will exhibit the asymmetry. In this case, we achieve a bi-anisotropic metamaterial containing chiral properties. The equivalent permeability tensor of the modified asymmetric material is analyzed below.

Dimensions and magnetic field of the modified asymmetric metamaterial structure in different views. (a) Periodic unit of the asymmetric metamaterial. Loop1 and loop2 has the same area of \(\:{S}_{1}\), loop1’ and loop2’ has the same area of \(\:{S}_{2}\); (b) The structure in view Z. (c) Magnetic field on x direction in the periodic unit; (d) Magnetic field on y direction in the periodic unit.

Firstly, we assume \(\:{H}_{0}\) is applied on x direction, and it generates an induced current \(\:J\), with same amplitude on the loop1 and loop2. The averaged induced magnetic intensity is \(\:{H}_{in}\) inside loop1 and loop2, and \(\:{H}_{out}\) outside two loops, which are all in x direction. The induced current generates \(\:{H}_{i{n}^{{\prime\:}}}\) inside loop1’and loop2’ and \(\:{H}_{ou{t}^{{\prime\:}}}\) outside, which are all along y direction. Permeability tensor of the modified asymmetric metamaterial can be expressed as:

Similar to the analysis process of the original metamaterial, we eventually had

where \(\:{T}_{1}=\frac{\frac{2}{at}}{\frac{Z}{{\mu\:}_{0}{S}_{1}\omega\:}j+\frac{at-{S}_{1}}{at}}\), \(\:Z\) is the impedance of the structure. Then, we assume \(\:{H}_{0}\) is applied on y direction. Similarly, we can obtain the equations as

where \(\:{T}_{2}=\frac{\frac{2}{at}}{\frac{Z}{{\mu\:}_{0}{S}_{2}\omega\:}j+\frac{at-{S}_{2}}{at}}\). Concluding the Eq. (10), each term of the permeability tensor can be derived as

Apparently, the off-diagonal terms \(\:{\mu\:}_{xy}\) and \(\:{\mu\:}_{yx}\) are distinct from each other. This inequality will lead to the asymmetric effects of the materials to the transmissions of linear polarized waves with magnetic field in x and y directions.

Comparison of magnetic field rotation of the original symmetric metamaterial and the modified asymmetric metamaterial. (a, d) Diagram of the magnetic field rotation of original symmetric metamaterial and modified asymmetric metamaterial. Directions of all arrows are in x-y plane; (b, e) Rotation angle of \(\:{H}_{rx}\) and \(\:{H}_{ry}\) relative to their rotation directions in a period; (c, f) Magnetic field vector of \(\:{H}_{0x}\), \(\:{H}_{0y}\), \(\:{H}_{rx}\) and \(\:{H}_{ry}\) at four moments within a period in view Z. The circular arrows represent the rotation direction of \(\:{H}_{rx}\) and \(\:{H}_{ry}\).

In order to verify the above analysis, the symmetric and asymmetric structures of the presented metamaterials are simulated under the conditions of linear polarized incident waves propagating in -z direction with magnetic field in x and y directions respectively. As shown in Fig. 7a and d, the incident magnetic field is represented by \(\:{H}_{0x}\) and \(\:{H}_{0y}\), and the rotated magnetic field after propagating through the material is represented by \(\:{H}_{rx}\) and \(\:{H}_{ry}\), where \(\:{\theta\:}_{x}\) and \(\:{\theta\:}_{y}\) are the rotation angles of \(\:{H}_{rx}\) and \(\:{H}_{ry}\) relative to their rotation directions. Two reference planes are chosen above and beneath the metamaterial to examine the rotation angles and directions of the magnetic field. The results are shown in Fig. 7b–f.

From Fig. 7a–c, it can be found that the rotation of \(\:{H}_{rx}\) and \(\:{H}_{ry}\) in symmetric metamaterial have the opposite rotation directions and the identical rotation angles. By comparison, as shown in Fig. 7d–f, \(\:{H}_{rx}\) and \(\:{H}_{ry}\) in asymmetric metamaterial exhibit same rotation directions but different variations of the rotation angles. The results indicate that for the linear polarized incident waves with propagation directions in the normal vector directions of the materials, the original symmetric materials have the symmetric effects on the transmissions of waves with orthogonal polarization directions, on which the modified asymmetric materials have the asymmetric effects. Due to the fact that modifying the structural dimensions will not disrupt the direction of chirality of the structures, the asymmetric materials have the similar effects on waves with opposite incident directions as the symmetric materials. In this case, wave transmissions in the asymmetric structures exhibit the characteristics that the rotation of polarization directions is only in a single specific direction regardless of the propagation directions or the polarization directions. This characteristic resembles the Faraday effect but can be realized in metamaterials without a static bias magnetic field.

Based on the above analysis, we further investigate the transmission coefficients of the presented metamaterial. The transmission matrix \(\:\left[T\right]\) connecting the complex amplitudes of the incident and transmitted magnetic field is shown as

where \(\:{H}_{tx}\) and \(\:{H}_{ty}\) is the transmitted magnetic field in \(\:x\) and \(\:y\) direction and \(\:{H}_{ix}\) and \(\:{H}_{iy}\) is the incident magnetic field in \(\:x\) and \(\:y\) direction. Each term of the transmission matrix is shown in Fig. 8. The symmetric metamaterial possesses the transmission coefficients that \(\:{t}_{xx}={t}_{yy}\) and \(\:{t}_{xy}={t}_{yx}\) ,while the asymmetric metamaterial possesses the transmission coefficients that \(\:{t}_{xx}\ne\:{t}_{yy}\) and \(\:{t}_{xy}\ne\:{t}_{yx}\). The results further prove the asymmetric transmission effect on linear polarized waves of the presented metamaterial.

The asymmetric metamaterial also exhibits asymmetric transmission characteristics for circularly polarized waves. The transmission matrix for circularly polarized waves \(\:\left[{T}_{circ}\right]\) is given by18,38

and the transmission matrix of backward linear polarized waves is

then we can obtain the transmission coefficient of circularly polarized waves incident in the metamaterial in forward and backward directions, which is shown in Fig. 9. The results demonstrate that for circularly polarized waves incident on the asymmetric metamaterial, the left-handed and right-handed waves exhibit asymmetric characteristics, and this asymmetry varies with changes in the incident direction.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have presented a novel magnetic-response metamaterial composed of orthogonally connected loops that exhibit non-diagonal terms of the equivalent permeability tensor, enabling an advanced magnetic response compared to conventional planar or non-connected 3D designs. Such structure offers key advantages such that it preserves strong magnetic flux concentration and delivers versatile functionalities while miniaturizing device spaces in compact integrated systems. Through theoretical modeling and simulation validation, we prove that our structure gives rise to asymmetric transmission (AT) for linear polarized waves in the absence of an external bias magnetic field. This observation underlines the distinctive capability of our metamaterial to manipulate wave propagation in direction-sensitive and polarization-sensitive manners, creating promising avenues for designing chiral components such as one-way waveguides and isolators. Furthermore, our detailed study of dimensional effects has established clear guidelines for tuning the operating frequencies, offering engineering flexibility in future device development. Our findings highlight the potential to unprecedentedly control electromagnetics, particularly for applications where compactness and multifunctionality are of paramount importance. By systematically analyzing and utilizing the non-diagonal permeability tensor, this work expands the frontier of magnetic metamaterial research, laying the groundwork for innovative designs in wave manipulation and polarization control.

Methods

Prototype fabrication

The rectangular loop is composed of two copper strips on the upper and lower surfaces of the FR4 board and copper cylinders along the through-holes in Z direction. Different loops on orthogonal directions are connected by copper strips in the interlayer at depth of \(\:{t}_{1}\) from the surfaces of the material. The medium board of FR4 material has the relative permittivity of 3.6 and relative permeability of 1. The prototype has the resonant frequency of nearly 11.7 GHz, and the detailed spatial dimensions are shown in Fig. 2.

Equivalent permeability calculation

In the simulation and the experiment, the permeability tensor cannot be measured directly. Instead, we measure the S-parameter and calculate the diagonal and off-diagonal terms of permeability respectively. The diagonal term \(\:{\mu\:}_{1}\) of the equivalent permeability can be derived from the S-parameter according to the relation of39,40

where \(\:k\) is the wave number and \(\:d\) is the thickness of the material. Due to the fact that the off-diagonal term \(\:{\mu\:}_{2}\) represents the response relation between magnetic fields in the orthogonal directions, it cannot be derived directly from Eq. (15). In this case, an indirect method is used to obtain \(\:{\mu\:}_{2}\)41. By rotating \(\:{H}_{0}\) by 45 degrees to \(\:{H}_{045}\) and decomposing \(\:{H}_{045}\) to two orthogonal components \(\:{H}_{0x}\) and \(\:{H}_{0y}\), we get

The magnetic induction in the 45° direction can be solved as

From Eq. (17), it can be found that \(\:{\mu\:}_{1}+{\mu\:}_{2}={\mu\:}_{45}\). With \(\:{\mu\:}_{1}\) and \(\:{\mu\:}_{45}\) calculated directly from the S-parameters, the off-diagonal term \(\:{\mu\:}_{2}\) can be obtained from \(\:{\mu\:}_{2}={\mu\:}_{45}-{\mu\:}_{1}\).

Experiment method

In the experiment, a pair of standard rectangular waveguides with dimensions of \(24 \, mm \times 6 \, mm\) are used to measure the prototype. The operating frequency range of the waveguide is 8 ~ 14 GHz. Two waveguides are connected to two ports of the vector network analyzer respectively through coaxial lines. First, we place the metamaterial prototype board vertically. Two waveguides are faced oppositely and closely attached on contrary sides of the prototype, which enables us to measure \(\:{\mu\:}_{1}\). Then, the metamaterial board is rotated 45 degrees around its normal direction, while the waveguides remain unmoved, to measure \(\:{\mu\:}_{45}\). We then can obtain \(\:{\mu\:}_{2}\) as \(\:{\mu\:}_{2}={\mu\:}_{45}-{\mu\:}_{1}\).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Change history

23 June 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07155-7

References

Kurter, C., Lan, T., Sarytchev, L. & Anlage, S. M. Tunable negative permeability in a Three-Dimensional superconducting metamaterial. Phys. Rev. Appl. 3, 054010. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.3.054010 (2015).

Pendry, J. B., Holden, A. J., Stewart, W. J. & Youngs, I. Extremely low frequency plasmons in metallic mesostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 4773–4776. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.76.4773 (1996).

Shelby, R. A., Smith, D. R. & Schultz, S. Experimental verification of a negative index of refraction. Science 292, 77–79. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1058847 (2001).

Smith, D. R., Pendry, J. B. & Wiltshire, M. C. K. Metamaterials and negative refractive index. Science 305, 788–792. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1096796 (2004).

Veselago & Viktor, G. The electrodynamics of substances with simultaneously negative values of ε and Μ. Phys. Usp. 10, 509–514 (1968).

Huidobro, P. A., Silveirinha, M. G., Galiffi, E. & Pendry, J. B. Homogenization theory of Space-Time metamaterials. Phys. Rev. Appl. 16, 014044. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.16.014044 (2021).

Cui, T. J., Qi, M. Q., Wan, X., Zhao, J. & Cheng, Q. Coding metamaterials, digital metamaterials and programmable metamaterials. Light Sci. Appl. 3, e218–e218. https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2014.99 (2014).

Wang, B. X., Xu, C., Zhou, H. & Duan, G. Realization of broadband Terahertz metamaterial absorber using an anti-symmetric resonator consisting of two mutually perpendicular metallic strips. APL Mater. 10, 050701. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0092958 (2022).

Ye, Y. et al. Reconfigurable ultra-sparse ventilated metamaterial absorber. APL Mater. 11, 121117. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0173504 (2023).

Zadeh, A. K. & Karlsson, A. Capacitive circuit method for fast and efficient design of wideband radar absorbers. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 57, 2307–2314. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAP.2009.2024490 (2009).

Chen, J. et al. High sensing properties of magnetic plasmon resonance by strong coupling in Three-Dimensional metamaterials. J. Lightwave Technol. 39, 562–565. https://doi.org/10.1109/JLT.2020.3033971 (2021).

Wang, G. Z. & Wang, B. X. Five-Band Terahertz metamaterial absorber based on a Four-Gap comb resonator. J. Lightwave Technol. 33, 5151–5156. https://doi.org/10.1109/JLT.2015.2497740 (2015).

Hand, T. H. & Cummer, S. A. Controllable magnetic metamaterial using digitally addressable Split-Ring resonators. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 8, 262–265. https://doi.org/10.1109/LAWP.2009.2012879 (2009).

Mejía-Cortés, C. & Molina, M. I. A two-dimensional disordered magnetic metamaterial. Phys. Lett. A. 409, 127517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physleta.2021.127517 (2021). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/

Yan, J., Radkovskaya, A., Solymar, L., Stevens, C. & Shamonina, E. Switchable unidirectional waves on mono- and diatomic metamaterials. Sci. Rep. 12, 16845. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-20972-4 (2022).

Yang, W. et al. Observation of optical gyromagnetic properties in a magneto-plasmonic metamaterial. Nat. Commun. 13, 1719. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29452-9 (2022).

Zhang, Q., Cherkasov, A. V., Arora, N., Hu, G. & Rudykh, S. Magnetic field-induced asymmetric mechanical metamaterials. Extreme Mech. Lett. 59, 101957. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eml.2023.101957 (2023).

Menzel, C., Rockstuhl, C. & Lederer, F. Advanced Jones calculus for the classification of periodic metamaterials. Phys. Rev. A. 82, 053811. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.82.053811 (2010).

Plum, E., Fedotov, V. A. & Zheludev, N. I. Planar metamaterial with transmission and reflection that depend on the direction of incidence. Appl. Phys. Lett. 94, 131901. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3109780 (2009).

Schwanecke, A. S. et al. Nanostructured metal film with asymmetric optical transmission. Nano Lett. 8, 2940–2943. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl801794d (2008).

Singh, R. et al. Terahertz metamaterial with asymmetric transmission. Phys. Rev. B. 80, 153104. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.80.153104 (2009).

Gao, S., Ota, Y., Liu, T., Tian, F. & Iwamoto, S. Faraday rotator based on a silicon photonic crystal slab on a bismuth-substituted yttrium iron Garnet thin film. Appl. Phys. Express. 16, 072003. https://doi.org/10.35848/1882-0786/acdc81 (2023).

Hogan, C. L. The ferromagnetic Faraday effect at microwave frequencies and its applications: the microwave gyrator. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 31, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1538-7305.1952.tb01374.x (1952).

Kodera, T., Sounas, D. L. & Caloz, C. Artificial Faraday rotation using a ring metamaterial structure without static magnetic field. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 031114. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3615688 (2011).

Lax, B., Button, K. J. & Hagger, H. J. Microwave ferrites and ferrimagnetics. Phys. Today. 16, 57–58. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3051073 (1963).

Sounas, D. L., Kodera, T. & Caloz, C. Electromagnetic modeling of a magnetless nonreciprocal gyrotropic metasurface. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 61, 221–231. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAP.2012.2214997 (2013).

Prudêncio, F. R. & Silveirinha, M. G. Optical isolation of circularly polarized light with a spontaneous magnetoelectric effect. Phys. Rev. A. 93, 043846. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.93.043846 (2016).

Katsantonis, I. et al. Giant enhancement of nonreciprocity in gyrotropic heterostructures. Sci. Rep. 13, 21986. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48503-9 (2023).

Tóth, E. et al. Layered babinet complementary patterns acting as asymmetric negative index metamaterial. Sci. Rep. 14, 29568. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79629-z (2024).

Pfeiffer, C., Zhang, C., Ray, V., Guo, L. J. & Grbic, A. High performance bianisotropic metasurfaces: asymmetric transmission of light. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 023902. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.113.023902 (2014).

Kenanakis, G., Economou, E. N., Soukoulis, C. M. & Kafesaki, M. Controlling THz and far-IR waves with chiral and bianisotropic metamaterials. EPJ Appl. Metamater. 2, 15 (2015).

Fan, W., Wang, Y., Zheng, R., Liu, D. & Shi, J. Broadband high efficiency asymmetric transmission of achiral metamaterials. Opt. Express. 23, 19535–19541. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.23.019535 (2015).

Fedotov, V. A. et al. Asymmetric propagation of electromagnetic waves through a planar chiral structure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 167401. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.167401 (2006).

Shi, J. et al. Dual-band asymmetric transmission of linear polarization in bilayered chiral metamaterial. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 191905. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4805075 (2013).

Wu, L. et al. Giant asymmetric transmission of circular polarization in layer-by-layer chiral metamaterials. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 021903. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4813487 (2013).

Xu, K., Xiao, Z., Tang, J., Liu, D. & Wang, Z. Ultra-broad band and dual-band highly efficient polarization conversion based on the three-layered chiral structure. Phys. E. 81, 169–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physe.2016.03.015 (2016).

Pendry, J. B., Holden, A. J., Robbins, D. J. & Stewart, W. J. Magnetism from conductors and enhanced nonlinear phenomena. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 47, 2075–2084. https://doi.org/10.1109/22.798002 (1999).

Albooyeh, M. et al. Classification of bianisotropic metasurfaces from reflectance and transmittance measurements. ACS Photonics. 10, 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.2c00940 (2023).

Smith, D. R., Schultz, S., Markoš, P. & Soukoulis, C. M. Determination of effective permittivity and permeability of metamaterials from reflection and transmission coefficients. Phys. Rev. B. 65, 195104. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.65.195104 (2002).

Smith, D. R., Vier, D. C., Koschny, T. & Soukoulis, C. M. Electromagnetic parameter retrieval from inhomogeneous metamaterials. Phys. Rev. E. 71, 036617. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.71.036617 (2005).

Suzuki, E., Furukawa, H. & Arai, K. I. A new Thin-Film permeameter for measuring all components of a permeability tensor. IEEE Trans. Magn. 43, 3359–3362. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMAG.2007.900038 (2007).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62201541).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C. and Q.Z. conceived the research. J.C. contributed to primary idea, theoretical analysis, simulation, experiment and manuscript writing. Q.Z. led the research, contributed the original idea, supervised the project and revised the manuscript. H.Y. and X.H. contributed to the investigation and manuscript writing. Y.L. contributed to software simulation and graph visualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of the Article, Figure 6 was a duplication of Figure 2.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cui, J., Yan, H., Lou, Y. et al. Metamaterials with asymmetric transmission effect based on magnetic field manipulation. Sci Rep 15, 12183 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96589-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96589-0