Abstract

Postoperative recurrence of pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD) remains a major challenge. This study aims to establish and validate a lipid metabolism-related prognostic model to predict recurrence in PAAD patients. The TCGA-PAAD database was used to establish a training cohort, which was validated using the ICGC database and multiple center cohorts. A prognostic model based on LASSO Cox regression and a nomogram was developed and further validated. Among 196 lipid metabolism-related genes, four were selected for the prognostic model. Patients were stratified into high- and low-risk groups based on the risk score. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses showed that tumor site, T stage, N stage, M stage, and risk score were significantly associated with progression-free interval (PFI). High-risk patients had worse PFI, overall survival (OS), and disease-specific survival (DSS) (all P < 0.05). Time-dependent ROC and decision curve analyses confirmed the superior diagnostic capacity of the nomogram. GSEA revealed enrichment in G2M checkpoint, glycolysis, estrogen response, and hypoxia pathways for the high-risk group. Additionally, high-risk scores correlated with poor immune infiltration, gene mutations, and tumor mutational burden (TMB). Single-cell analysis suggested that risk genes interact with various cell types to promote PAAD progression. A novel lipid metabolism-related prognostic model was developed and validated to predict recurrence and survival in PAAD patients, with strong accuracy and stability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is caused by the abnormal and uncontrolled growth of cells in pancreatic tissue. The 5-year survival rate for pancreatic cancer is 3–4%1. Despite improvements in surgical techniques, treatments and perioperative management, the prognosis of PAAD gains poor due to the high rate of tumor recurrence2. Recurrence of PAAD is usually classified into early recurrence and late recurrence, which is usually defined by a cut-off value of postoperatively one year, and the outcomes are worse for patients with recurrent early than patients with late recurrence3. Therefore, screening the recurrence patients in high risk for treatment strategies in time, is essential to the long-term survival for patients.

Predicting recurrence of pancreatic cancer postoperatively continues to be the main subject of cancer research. Several previous studies have identified features associated with pancreatic cancer recurrence, such as clinicopathological factors, tumor tissue microenvironment, tumor imaging, serum CA19-9 levels, and gene expression levels (TP53, BFGF, CD34, and VEGF), which have been shown to correlate with survival in pancreatic cancer patients4,5,6. In addition to this, KRAS, TP53, CDKN2A and SMAD4, cancer-associated mutated genes, have been taken into account in many studies simultaneously to predict recurrence of pancreatic cancer7.

Lipid metabolism has been increasingly recognized as an important pathway in cancer cells over the last few years8,9. Lipids are nutrients composed of fats and lipids that are widely distributed in cellular organelles and are key components of all membranes10. In addition, lipids are stored by cells in lipid droplets (LDs) when there is an adequate supply of energy, but on the other hand, nutrient scarcity can trigger homeostatic mechanisms in lipids, which can act as second messengers to transduce signals within the cell and serve as an important source of energy10. Dysregulation of lipid metabolism contributes to the onset and progression of various metabolic diseases, including cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and malignant diseases11,12.

In pancreatic malignancies, lipid metabolism genes assume heightened importance due to the organ’s unique metabolic demands and tumor microenvironmental constraints. The pancreas serves dual endocrine and exocrine functions, requiring precise lipid regulation for insulin secretion (via β-cell lipid signaling) and digestive enzyme production13. PAAD rasterized by nutrient-poor, desmoplastic stroma and hypoxia, exploits lipid metabolic reprogramming to fuel growth under these adverse conditions14. Key lipid genes such as FASN and ACSL are frequently overexpressed in PAAD, driving de novo lipogenesis to compensate for erratic extracellular nutrient supply while supporting membrane biosynthesis for rapidly dividing cells15. Moreover, lipid droplets accumulated via upregulated DGAT1 not only serve as energy reservoirs but also protect against oxidative stress a critical survival mechanism in PAAD’s harsh microenvironment16. Hypoxia-inducible lipid metabolism genes (HIF-1α-regulated CPT1A) further enable fatty acid oxidation to sustain ATP production when glycolysis is limited17. Crucially, pancreatic stellate cell-derived lipids in the tumor stroma are scavenged by cancer cells via CD36, creating a parasitic metabolic symbiosis that fuels tumor progression and chemoresistance18. These pancreas-specific adaptations underscore why targeting lipid metabolism genes particularly those interfacing with stromal crosstalk or stress adaptation holds unique therapeutic potential for pancreatic cancers. These metabolic vulnerabilities present promising therapeutic targets, with emerging strategies focusing on FASN inhibitors to disrupt de novo lipogenesis19, CD36 blockade to impair lipid scavenging20, and FAO pathway modulation. Combinatorial approaches integrating lipid metabolism inhibitors with conventional chemotherapy or immunotherapy show particular promise in overcoming therapeutic resistance while addressing the metabolic plasticity of malignant cells21.

Currently, a large body of evidence reveals abnormal lipid metabolism in various cancers, including membrane formation, lipid synthesis and degradation, and lipid-driven cell signaling12,22. Although there are several high-quality reviews discussing lipid metabolism in other cancer types23,24, there are currently no studies of lipid metabolism reprogramming in early recurrence of pancreatic cancer. Therefore, considering the importance of lipid metabolism in malignant tumors, a comprehensive understanding of reprogrammed lipid metabolism has a key role in the search for new markers of early PC recurrence.

In this study, we screened the expression of genes related to lipid metabolism in pancreatic cancer and normal pancreatic tissue samples from the TCGA database to develop an innovative model for predicting the prognosis of PAADs. The model can be used to predict postoperative recurrence and survival of pancreatic cancer patients. In addition, the model also has good performance on other queues. Bioinformatics analysis was used to reveal the relationship between the prognosis of PAAD and lipid metabolism.

Materials and methods

Data collection and preprocessing

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA, https://www.tcga.org/) and the ICGC databases were used to gather transcriptome profiles and clinical data for patients with PAAD. The TCGA database was queried for 174 patients with PAAD. As a validation set, 262 patients were gathered from the ICGC databases and 99 patients’ data samples Specifically, the samples used in this study came from surgically removed PAAD tissue from patients who underwent surgery. Pancreatic cancer tissue samples included in this study were all from patients who underwent radical surgery in the Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, PLA General Hospital from January 2020 to December 2023. In order to ensure the reliability of the biological characteristics of the samples, all operations strictly followed the Guidelines for the construction of Tumor Sample Bank by the Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology (CSCO) and the Standardized Procedures for Tumor Tissue Collection by WHO. Tissue samples are processed immediately after removal and stored in liquid nitrogen to minimize degradation and ensure their quality. Transfer to -80 °C refrigerator or liquid nitrogen tank for long-term storage.

Data standardization and acquisition

Download data from the TCGA, ICGC and normalize it to fragments per kilobase per million (FPKM) values. Pancreatic cancer prognosis related genes were downloaded from online bioinformatics tools (GEPIA2) (p < 0.05). Genes with |log2FC|>0.58 and adjP < 0.05 were defined as statistically significant differential genes. 1035 lipid metabolism related genes (LMRGs) were obtained from published literature (PMID: 37469520).

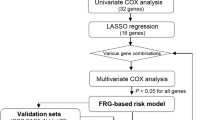

Formulation and verification of prognostic models for LMGs

To investigate the prognostic significance of LMGs in PAAD, Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) penalized Cox proportional risk regression analyses were used to reduce overfitting. LASSO penalized Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was performed to reduce overfitting. The optimal value of the penalty parameter (λ) was selected using 10-fold cross-validation based on the minimum criterion Then, univariate and multivariate analyses were performed on the 16 genes screened to identify Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) significantly associated with progression-free interval (PFI) in TCGA -GTEx database within pancreatic cancer tumor and normal tissue samples. The R package “glmnet” and the minimum criterion to calculate the penalty parameter were used to analyze the above process25. In addition, three prognostic indicators, progression-free interval (PFI), overall survival (OS), and disease-specific survival (DSS), were demonstrated using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. Pancreatic cancer patients in the training and validation cohorts were categorized into low-risk and high-risk score subgroups based on the median value of the risk score. Risk scores were used to predict recurrence in patients with PAAD. Kaplan-Meier survival curves and receiver operating characteristic curves (ROC) were used to determine their accuracy, and Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) was used to validate the sensitivity of the models. The survival package was used to fit the prognostic model, and the stdca.R file was used for DCA analysis. We calculated the risk score using the following formula: Risk score = Σ (A_i × Y_i) (A_i represents the coefficient for gene i from the Cox mode; Y_i is the expression level of gene). Risk characteristics were correlated with clinical characteristics using stratified analysis. In addition, univariate Cox analysis was used to identify clinical characteristics with prognostic value and a nomogram was drawn based on the risk score. ROC curves were used to assess the efficacy of the nomogram at 1, 2, and 3 years.

qRT-PCR detection

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. cDNA was generated by reverse transcription of RNA samples using the RevertAid RT kit (Transgene, AT341-01). qPCR was carried out using PowerUp™ SYBR™ Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A25742) for qPCR Detection. Gene amplification levels were detected using the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The relative expression of mRNA was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Supplementary Table S1 describes the primers for RT-qPCR (It has been uploaded as supplementary material, Supplementary Table [S1).

Analysis in functional enrichment of DEGs in high and low risk groups

Differential genes between high and low risk groups in TCGA-PAADs were annotated by Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of the Genome (KEGG) (|log2FC|>0.58; adjusted p-value (adjP) < 0.05), which accomplished by the R package “ClusterProfiler”26.

Analysis of tumor infiltrating immune cells

The proportional number of immune infiltrating cells in all tumor samples was calculated based on the transcriptional profile of PAAD in TCGA. Cell type identification analysis was done using “CIBERSORT” in the R software package27. The immune infiltration of the two groups were compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. In order to identify significant differences in the data, statistical analyses were performed with one-way ANOVA or Student’s t-test. This study was conducted using R software (4.2.1). Survival analysis of Kaplan-Meier was performed using the log-rank test. One-way multifactorial COX analysis gave hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A significant difference between the two groups existed when the P value < 0.05. Spearman correlation analysis evaluated the relationship between high and low risk group within TMB, MSI, and immunity. Differences with P-values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Expression of DEGs between normal tissues and tumor tissues

We screened 6725 genes related to pancreatic cancer prognosis from GEPIA2 (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn) database and collected 1035 genes related to lipid metabolism in pancreatic cancer from the literature (Fig. 1A). Ultimately, 196 intersection genes were generated in the two databases (Fig. 1A) (|log2FC|>0.58; P Value < 0.05). Then, LASSO regression analysis and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis were used to screen 16 characteristic prognostic genes identified (Fig. 1B) (P < 0.05), which were MLYCD, PTGES, AGPAT1, ST3GAL2, HSD17B1, PLAAT4, MIGA2, PLAAT3, ARSG. TSPOAP1, PRKACA, CAV1, PIP5K1B, SLCO1B3, FIG4, SPTLC3. The minimum parameter determined the penalty parameter (Fig. 1B,C). Seven intersection genes were found to be differentially expressed between pancreatic tumor tissues and normal tissues (Fig. 1D, E, P < 0.05). The heatmap shows the distribution of screened genes across all samples, indicating relatively stable gene expression across samples (Fig. 1F). Pearson correlation analysis shows the intersection of the correlation between gene (Fig. 1G).

Prognosis of lipid metabolism related genes screening and expression. (A) Venn diagram of prognosis of lipid metabolism related genes. (B,C) Cross-validation for tuning parameter screening in the LASSO regression model. (D,E) Box plot of between the normal and the tumor tissues (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ***P < 0.0001). (F) heat map of prognostic gene. (G) Pearson correlation analysis.

Development of prognostic gene model in the training set and testing set

The data of 178 pancreatic cancer patients were screened from the TCGA database, and the genes with prognostic features were screened by LASSO regression analysis and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. We then screened the characteristic prognostic genes using LASSO regression analysis and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis (P < 0.05), and the seven genes identified, PTGES, ST3GAL2, PLAAT3, PRKACA, PIP5K1B, SLCO1B3 and FIG4, were included in the subsequent univariate and multivariate COX analysis (Fig. 2A, B), and a four- gene prognostic model was developed. In addition, the KM survival curves of PFI, OS and DSS were plotted for these potential genes (Figure 2C–N), and the results showed that these candidate genes had an impact on pancreatic cancer recurrence (P < 0.05). Figure 3 also depicts the risk score distribution, patient survival, and expression heat map for the four prognostic genes. The univariate and multivariate COX analysis of the genes revealed that SLCO1B3, PRKACA, ST3GAL2and PTGES had the ability to operate as independent prognostic variables, with SLCO1B3 being beneficial for survival and PRKACA, ST3GAL2and PTGES being detrimental for survival. The 178 patients were classified into low- and high-risk groups (Fig. 3A) using the risk score formula’s median score. To evaluate the sensitivity and accuracy of the prognostic model, Kaplan-Meier curves (Fig. 3D) and time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves (Fig. 3G) as well as DCA curves (Fig. 3J–M) were plotted. The results showed that there was a significant difference in the recurrence curve between the high-risk group and the low-risk group (P < 0.001). The AUC values of 1 and 2 years were 0.789 and 0.846, respectively. DCA curves at 1 and 2 years showed that the model had good sensitivity. In addition, we validated the model in external databases (Fig. 3B, E,H, K,N). We also validated our model by testing the expression of risk-associated genes in samples obtained from patients who underwent pancreatectomy at multiple centers (Fig. 3C, F,I, L,O).

Risk-score model based on differential expression of LMRGs in patients with PAAD. Risk score and survival time distributions, and heatmaps of gene-expression levels of the LMRGs signature in the TCGA (A), ICGC (B), Multicenter (C)cohorts. KM curves of the risk score model for predicting PFI in the TCGA (D), ICGC (E), Multicenter (F) cohorts. ROC curves and AUC values of the risk score model for predicting the 1 and 2 year PFI times in the TCGA (G), ICGC (H), Multicenter (I) cohorts. DCA curves of the risk score model of 1 and 2 year in the TCGA (J,M), ICGC (K,N), Multicenter (L,O) cohorts.

Clinical evaluation of prognostic risk models based on the training set

To examine the clinical utility of prognostic assessment, we investigated the association between risk scores and clinical variables using univariate and multivariate COX methods. In univariate COX analysis, we found that tumor location, tumor size (T), tumor invasion (N), tumor metastasis (M), and risk score were all significantly associated with PFI (Figure 4A) (P < 0.05). Interestingly, there are only the risk score associated with PFI in the multivariate COX (Fig. 4B) (P < 0.001). Therefore, lipid metabolism-related genes are closely related to the prognosis of low pancreatic cancer, especially early recurrence. We also found variations in tumor location and T, N and M stage distribution between patients in the low-risk group and those in the high-risk group (Fig. 4C–H). Combined with multivariate Cox regression analysis, the risk score could be used as an independent predictor of PAAD in all patients. In addition, when the risk score was paired with other clinicopathological parameters, the ROC curve showed a rose AUC, suggesting that the risk score was an independent predictor (Fig. 4I–K).

Univariate and Multivariate analysis for hazard ratio values of risk score and clinical characters in the training set. Confidence interval (A,B). The relationship between prognostic gene expression and clinical factors (C–H). ROC analysis of clinical factors to predict the prognosis of TCGA-PAADs patients (I–K).

Developing and validating a nomogram that incorporates clinical features

In the TCGA cohort, we constructed a Nomogram diagram combined with clinical information. A total score was calculated for each patient by summing the results for each prognostic criterion. Overall score higher in patients with poor clinical outcome (Fig. 5A), with the predicted and actual recurrence rates agreeing perfectly in calibration chart (Fig. 5B–D).

Functional analysis based on risk model

We used the “limma” R tool to extract DEGs to further investigate the subclass-related pathways defined by the risk model. A total of 26 DEGs were found between the low-risk and high-risk categories in the TCGA cohort (Fig. 6A). Among them, 14 genes were up-regulated, and 12 genes were down-regulated. GO enrichment and KEGG pathway analyses were performed on the basis of differences between the high-risk and low-risk groups (Fig. 6B, C). The enriched pathways were found to be T cell regulation and cytokine regulation related pathways. GSEA enrichment analysis revealed that 12 gene sets were up-regulated, and 4 gene sets were down-regulated in the high-risk group (Fig. 6D–N).

The enriched item in GO, KEGG, GSEA analysis. (A) Different genes Between the low and high-risk categories in the TCGA cohort. (B) The enriched item in gene ontology analysis. (C) The enriched item in Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes analysis form Kanehisa laboratories authorization including JAK-STAT signaling pathway-hsa04630, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway -hsa04151, Chemokine signaling pathway-hsa04062 (Ref: 250532). (D-N) The Gene Set Enrichment Analysis in HALL marker.

Risk scores for immune cell infiltration, tumor somatic mutations, and tumor microenvironment characteristics in the TCGA-PAADs cohort

Using R package “maftools” shows the high-risk and low-risk groups between somatic mutation distribution difference (Fig. 7A). High-risk and low-risk groups of TP53 and Kras gene mutation rate were 72.5% and 60.7%, respectively. Correlation analysis showed a positive correlation between risk scores and tumor mutational burden (Fig. 7B), with a higher tumor burden in the higher-risk group (Fig. 7C). The cellular stromal cell score, immune cell score, and composite score were calculated using the ESTIMATE method (Fig. 8), and the CIBERSORT algorithm was used to calculate the relative number of 22 immune cell types in each PAAD patient (Fig. 8A, B). Correlation studies of risk ratings and immune-cell infiltration showed significant differences in the infiltration of most immune-cells in the two subtypes (Fig. 8C, D,E). The high-risk group of activation Th2 type auxiliary fine is significantly higher than the high-risk group (P < 0.05). In addition, in order to better understand the characteristics of immune cells and its connection with DEGs, we use the TIMER database analysis of the immune cells abundance and five genetic correlations between prognosis and outcome as supplementary material upload added (Supplementary figure S1).

Immune features of risk score. (A,B) Boxplot indicating the levels of immune cell infiltration in high-risk and low-risk PAAD patient. (C) The difference of stromal risk score, immune score and estimate score. (D) The Immune checkpoints expression in high-risk and low-risk group. (E) TIDE score in high-risk and low-risk group.

Identification of lipid metabolism related DEGs based on the single cell RNA sequencing

We also downloaded and analyzed pancreatic cancer single-cell data from the GEO database. Seven cell types were obtained by dimensionality reduction clustering of all cells, namely mast cells, B cells, myeloid cells, epithelial cells, T lymphocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells (Fig. 9A). Furthermore, these cell subclasses were validated with 26 recognized cell markers, as shown in (Fig. 9B). Additionally, the expression of five DE-LMRGs in each cell type was analyzed. STCGAL2, SLCO1B3, PTGES, and PRKACA were widely distributed in various cell clusters (Fig. 9C–F). STCGAL2 and PRKACA mainly expressed in immune cells, SLCO1B3, PTGES and FIG4 main expression in the epithelial cells, these genes may be synergies between different cell types, and jointly promote the occurrence of pancreatic cancer. AUCell R package was used to analyze the expression of DE-LMGRs in all single cell. In general, DE-LMRGs high expression of cell has higher AUC values. When the AUC value was set to 0.58, the AUC value (LMRG score) of 1886 cells was above the threshold (Fig. 9G). GO and KEGG analyses were performed on DEGs in cell populations with high LMRG scores. GO, according to the results of DE- LMRGs mainly involved in WBC migration, myeloid WBC migration, phagocytosis, positive adjustment response to external stimuli, leukocyte chemotaxis, cell chemotaxis, the adjustment of the leukocyte migration, white blood cell-cell adhesion, the adjustment of the peptide enzyme activity, white blood cells positive regulates cell adhesion, The function of cell-cell adhesion of (Fig. 9H). KEGG results showed that DE-LMRGs were mainly related to leishmaniasis, tuberculosis, Rheumatoid arthritis, Osteoclast differentiation, Proteoglycan in cancer, Amebiasis, Malaria, NF-kappa B signaling pathway, Natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity, Staphylococcus aureus infections, Leukocyte transendothelial migration, Lipids and atherosclerosis, IL-17 signaling pathways (Fig. 9H).

Discussion

In this study, we established a prognostic model for pancreatic cancer using five genes and were able to classify all patients into high-risk and low-risk groups. Progression-free interval (PFI) was lower in high-risk patients than in low-risk patients. The area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to evaluate and confirm the ability to predict. The DCA curve was used to detect the sensitivity of the model. In the training cohort, the nomogram showed a high ability to predict pancreatic cancer recurrence in PAAD patients. GSEA analysis showed that the high-risk group was enriched in tumor-related pathways and pathological processes such as G2m checkpoint, glycolysis, estrogen response and hypoxia.

Previous studies have shown that genes involved in lipid metabolism are independent prognostic markers for many cancer types. In this work, we screened 196 genes related to lipid metabolism prognosis. After performing Lasso and COX regression analyses, a predictive model comprised of four genes (SLCO1B3, PRKACA, ST3GAL2 and PTGES) was utilized to categorize LGGs into high-risk and low-risk categories. Subsequent KM curve, ROC curve, and risk factor plot analyses showed that this risk signature performed well for risk grouping of major PAADs in both TCGA and CGGA datasets. In addition, a Nomogram model for predicting PFI recurrence in PAAD patients was constructed based on genes related to lipid metabolism, and the risk score defined by WHO was incorporated into the Nomogram model. Nomogram and ROC curve analysis demonstrate that the nomogram could accurately predict PFI in TCGA training cohort, ICGC external validation cohort 1 and external validation cohort 2. Therefore, the model can be used to assist in determining the subsequent treatment plan for patients.

The developed nomogram demonstrates significant potential for clinical translation by bridging multidimensional data into actionable prognostic insights. Its ability to integrate traditional clinicopathological variables (TNM staging, treatment modalities) with emerging molecular features (lipid metabolism genes such as ST3GAL2, SLCOAB3, PTGES, PRKACA) enables precise risk stratification, particularly in malignancies like pancreatic cancer where metabolic reprogramming drives therapeutic resistance. Clinically, this tool may guide personalized decision-making for instance, identifying high-risk patients (total points > 100) who could benefit from aggressive therapies or targeted metabolic interventions, while sparing low-risk subgroups from overtreatment. Additionally, the nomogram’s dynamic adaptability allows real-time updates based on treatment response or disease progression, enhancing its utility in longitudinal care. Beyond oncology, such models could optimize surgical risk assessment, chronic disease management, and resource allocation in resource-constrained settings. By visualizing survival probabilities and comparative outcomes under different therapeutic scenarios, the nomogram also serves as a shared decision-making tool, aligning clinical recommendations with patient preferences. These applications underscore its role not only as a prognostic calculator but as a platform for translating mechanistic discoveries into clinically actionable strategies, ultimately addressing the heterogeneity and complexity of modern precision medicine.

Studies have shown that FIG4 forms a protein complex with PIKfyve and Vac14, which plays an important role in the regulation of phosphatidylinositol PI (3,5) p2 and PI (5) P. lack of the complexes may lead human nervous system related diseases28. As a core regulator of PI (3,5) P2 metabolism, FIG4 is essential for neuronal survival, axonal homeostasis, and bone development by maintaining endosom-lysosome system and autophagy flux29. Its loss of function leads to a continuum of phenotypes ranging from peripheral neuropathy (CMT4J) to systemic developmental disorders (YVS) and is associated with the risk of neurodegenerative diseases such as ALS30. The dose-sensitive and tissue-specific regulatory mechanisms of this gene are the key to understanding its multieffect pathogenesis31.

SLCO1B3 is used as an androgen transporter gene for the treatment of prostate cancer, and its deletion may be a genomic determinant of resistance to androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) in prostate cancer32. In addition to this, SLCO1B3 has been associated with poor prognosis of ICC, enhancing HOXC8 expression to enhance ICC proliferation and metastasis, while antagonising PD-L1 degradation to induce immune evasion, thereby promoting ICC progression33. SLCO1B3 serves as a key organic anion transporter in the liver and some tumors. By mediating liver uptake of binding bilirubin, drugs and metabolites, SLCO1B3 maintains bilirubin homeostasis and influences drug efficacy and toxicity34. Its specific high expression in digestive tract tumors provides a potential strategy for targeted chemotherapy, and the effect of its gene polymorphism on drug transport efficiency needs to be considered in individual therapy35.

PRKACA was found to be mutated in the sporadic adrenocortical adenoma (ACA) gene, which drives an increase in catalytic protein kinase A (PKA) function and induces the expression of genes associated with tumor growth and adrenal steroidogenesis36. While ST3GAL2 was found to be highly expressed in pancreatic cancer and significantly associated with low overall survival37. PRKACA is a key molecule of PKA signaling pathway, and its normal function depends on the dynamic binding of regulatory subunits and cAMP regulation38,39. Constitutive activation or increased sensitivity due to mutations, through abnormal phosphorylation of downstream targets (e.g., steroid synthetase, Hedgehog pathway components), triggering either adrenal cortisol overproduction (Cushing’s syndrome) or embryonic developmental defects40. The mutant spectrum ranges from somatic hotspot mutations (tumors) to germ cell variants (systemic diseases), highlighting the importance of dose sensitivity and tissue-specific effects41.

FUBP1 can activate the arachidonic acid (AA) metabolic pathway by regulating prostaglandin E synthase (PTGES) expression, leading to lobaplatin resistance in osteosarcoma42. PTGES is a rate-limiting enzyme in prostaglandin E2 synthesis. Its membrane-binding properties and glutathione dependent catalytic mechanism make it play a central role in inflammation and tumor microenvironment. Although no significant genetic association has been shown in breast cancer, its high expression and pro-inflammatory regulation in cancer cells suggest a potential function in tumor progression (e.g. immune escape, angiogenesis)43. Targeting PTGES may provide a therapeutic strategy for cancer or inflammatory diseases by inhibiting PGE2 production, but its dynamic regulatory mechanisms in specific cancer types need to be further investigated44.

PAAD is one of the most aggressive and refractory tumors. Postoperative adjuvant therapy and regular follow-up of patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma have been widely accepted. However, whether neoadjuvant therapy can further improve the prognosis of patients with resectable PAAD remains controversial45. A growing number of studies have shown that early identification of high-risk patients with poor prognosis and timely intervention can improve their prognosis46. In this study, we developed a prognostic model based on preoperative status and tumor biomarkers to predict postoperative recurrence and survival in patients with resectable PAAD. The model effectively identified high-risk patients with poor prognosis, demonstrating robust performance and discrimination. Univariate and multifactorial COX regression analysis showed that tumor location, tumor size, tumor invasion, tumor metastasis were independent prognostic factors affecting postoperative recurrence in patients with PAAD. It is well known that there are significant prognostic differences between patients with pancreatic head and pancreatic body-tail cancers, and in addition to the differences between anatomical locations, differences at the genetic-molecular level have been identified and studied in both. Pancreatic body tail cancer is related to the squamous subtype of pancreatic cancer and is enriched with genetic programmers associated with inflammation, EMT and potential immune evasion mechanisms47. This promotes research work to use novel approaches to better define early recurrence through molecular markers. Meanwhile, splenic vascular invasion is also associated with a high recurrence rate and low overall survival after surgery for pancreatic coccygeal carcinoma, suggesting the need for neoadjuvant therapy48.

Higher TMB is generally associated with the production of more mutations and neoantigens, which may affect the immune response and increase the risk of immune escape. In high-risk patients, higher TMB may lead to changes in immune cell infiltration patterns and is associated with lipid metabolism disturbances. In addition to this, our results showed that tumor burden mutations were significantly higher in the high-risk group than in the low-risk group (p = 0.00011), which is consistent with changes in immune cell infiltration. High TMB may increase tumor microenvironment infiltration of immune cells, but immune escape mechanisms may lead to inadequate immune response, and this process may be regulated by lipid metabolism. More importantly, elevated TMB in high-risk tumors and changes in the immune microenvironment may lead to disturbances in lipid metabolism, thus affecting the activity of immune cells and anti-tumor immune response49. Therefore, the reprogramming of lipid metabolism may be an important mechanism for immune escape in high-risk tumors.

Over the past decades, the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) has established a well-defined cancer staging system based on 3 key components: local tumor extent (T stage), dissemination to regional lymph nodes (N stage), and metastatic spread to distant sites (M stage) (TNM staging)50. The AJCC TNM staging system attempts to use anatomical and reproducible parameters to distinguish between groups with different survival outcomes. Reliable prediction of survival estimates is critical in cancer treatment. An accurate prognosis helps clinicians guide treatment decisions and provides researchers with a tool to adjust cancer staging when assessing treatment outcomes51.

Although our study identified ST3GAL2, SLCO1B3, PTGES, and PRKACA as key genes associated with lipid metabolism in PAAD, the lack of experimental validation is a notable limitation. Functional analyses, such as gene knockdown, overexpression, or pathway analysis, are essential to confirm their biological relevance in PAAD progression. Additionally, exploring their interactions with key signaling pathways and correlating their expression with clinical outcomes in real-world cohorts will provide valuable insights. We acknowledge that experimental validation will strengthen the robustness of our model, offering direct evidence for these genes’ roles in lipid metabolism and their potential as therapeutic targets. Future research, including in vitro studies and clinical sample validation, is necessary to further elucidate the functional implications of these genes in PAAD. Future research may include the following. The LMGRs target gene in pancreatic cancer cell lines was knocked down by CRISPR/Cas9 and other techniques to evaluate proliferation, invasion, and lipid metabolism changes. In vivo, xenograft models were used to compare the growth and risk of tumor growth/metastasis in normal-expression and low-expression groups. Immunohistochemistry of protein expression in pancreatic cancer tissue microarray was used to verify the correlation of recurrence survival. Finally, RNA sequencing after interfering genes was performed to identify downstream pathways (e.g., lipid biosynthesis, EMT).

However, the exploration of these genes as biomarkers in plasma is also of scientific importance. Studies have shown that the level of SLCO1B3 in plasma exosomes of Prostate cancer patients is positively correlated with oxaliplatin resistance32, suggesting that it may dynamically monitor chemotherapy resistance in pancreatic cancer. A study suggests that ST3GAL2 may be involved in abnormal urine glycosylation in Parkinson’s disease (PD) by regulating sialylation modification. This finding provides a new direction for the development of non-invasive diagnosis of PD (urine test) based on markers of glycosylation52.PGE2/EP4 signaling regulates stem cell homeostasis through exosomes, and PTGES, as a key enzyme in PGE2 synthesis, is a necessary prerequisite for its signaling pathway. Although the abstract does not directly address the function of PTGES, studies can further complement the molecular details of this mechanism by examining PTGES expression or activity and resolving its specific role in PGE2 generation and signaling in stem cells53. Although these studies do not indicate the expression of LMGRs in plasma, these studies provide a theoretical basis for the value of LMGRs in plasma.

In contrast, few studies have been conducted on the relevance of lipid metabolism-related genes to early recurrence of pancreatic cancer. Our study provides new directions for further research. In conclusion, we created and validated a risk scoring system for prognosis and risk stratification using lipid metabolism-related genes from the TCGA and CGGA datasets and a multicenter pancreatic cancer cohort. The prognostic model showed high predictive accuracy. Our exploratory work provides a theoretical basis for further research on the role of lipid metabolism-related genes in pancreatic cancer. Since this study is a gene-based bioinformatics study, some problems remain. Multi-omics combined with artificial intelligence is the future direction of bioinformatics. Therefore, learning new features from multi-omics datas that facilitate prediction of prognosis is an important step for machine learning models to predict survival and relapse.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the TCGA , ICGC, GEO repository, [TCGA: https://www.cancer.gov/, ICGC: https://dcc.icgc.org/, GEO: GSE205013]. The validation cohort datasets used analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Siegel, R. L., Giaquinto, A. N., & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74 (1), 12–49. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21820 (2024).

Zhang, X. P. et al. Early and late recurrence patterns of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a multicenter study. Int. J. Surg. 109 (4), 785–793. https://doi.org/10.1097/js9.0000000000000296 (2023).

Kim, N. et al. Predictive nomogram for early recurrence after pancreatectomy in resectable pancreatic cancer: risk classification using preoperative clinicopathologic factors. Cancers (Basel). 12 (1). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12010137 (2020).

Fujioka, S. et al. Angiogenesis in pancreatic carcinoma: thymidine phosphorylase expression in stromal cells and intratumoral microvessel density as independent predictors of overall and relapse-free survival. Cancer 92 (7), 1788–1797 (2001).

Oshima, M. et al. P53 Immunolabeling in EUS-FNA biopsy can predict low resection rate and early recurrence in resectable or borderline resectable pancreatic cancer treated with neoadjuvant therapy. J. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Sci. 30 (6), 802–814. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhbp.1286 (2023).

Masugi, Y. et al. Post-operative mortality and recurrence patterns in pancreatic cancer according to KRAS mutation and CDKN2A, p53, and SMAD4 expression. J. Pathol. Clin. Res. 9 (5), 339–353. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjp2.323 (2023).

Waddell, N. et al. Whole genomes redefine the mutational landscape of pancreatic cancer. Nature 518 (7540), 495–501. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14169 (2015).

Cui, M. Y., Yi, X., Cao, Z. Z., Zhu, D. X. & Wu, J. Targeting strategies for aberrant lipid metabolism reprogramming and the immune microenvironment in esophageal cancer: A review. J. Oncol. 2022, 4257359. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/4257359 (2022).

Cheng, C., Geng, F., Cheng, X. & Guo, D. Lipid metabolism reprogramming and its potential targets in cancer. Cancer Commun. (Lond). 38 (1), 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40880-018-0301-4 (2018).

Luo, X. et al. Emerging roles of lipid metabolism in cancer metastasis. Mol. Cancer. 16 (1), 76. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-017-0646-3 (2017).

Goldstein, J. L. & Brown, M. S. A century of cholesterol and coronaries: from plaques to genes to Statins. Cell 161 (1), 161–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.036 (2015).

Poggiogalle, E., Jamshed, H. & Peterson, C. M. Circadian regulation of glucose, lipid, and energy metabolism in humans. Metabolism 84, 11–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2017.11.017 (2018).

Huang, Z., Ma, Y., Sun, Z., Cheng, L. & Wang, G. Ferroptosis: potential targets and emerging roles in pancreatic diseases. Arch. Toxicol. 98 (1), 75–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-023-03625-x (2024).

Yin, X. et al. Lipid metabolism in pancreatic cancer: emerging roles and potential targets. Cancer Commun. (Lond). 42 (12), 1234–1256. https://doi.org/10.1002/cac2.12360 (2022).

Lai, Y. et al. Dietary Elaidic acid boosts tumoral antigen presentation and cancer immunity via ACSL5. Cell. Metab. 36 (4), 822–838e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2024.01.012 (2024).

Cheng, X. et al. Targeting DGAT1 ameliorates glioblastoma by increasing fat catabolism and oxidative stress. Cell. Metab. 32 (2), 229–242e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2020.06.002 (2020).

An, K., Shi, B., Lv, X., Liu, Y. & Xia, Z. T-2 toxin triggers lipid metabolism disorder and oxidative stress in liver of ducks. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 286, 117169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2024.117169 (2024).

Zhao, T. et al. ESE3-positive PSCs drive pancreatic cancer fibrosis, chemoresistance and poor prognosis via tumour-stromal IL-1β/NF-κB/ESE3 signalling axis. Br. J. Cancer. 127 (8), 1461–1472. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-022-01927-y (2022).

Schultz, K. et al. Snapshots of acyl carrier protein shuttling in human fatty acid synthase. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08587-x (2025).

Xu, S. et al. Uptake of oxidized lipids by the scavenger receptor CD36 promotes lipid peroxidation and dysfunction in CD8(+) T cells in tumors. Immunity 54 (7), 1561–1577e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2021.05.003 (2021).

Oh, M. et al. The lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 inhibitor Darapladib sensitises cancer cells to ferroptosis by remodelling lipid metabolism. Nat. Commun. 14 (1), 5728. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-41462-9 (2023).

Byrne, A. et al. Tissue-resident memory T cells in breast cancer control and immunotherapy responses. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 17 (6), 341–348. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-020-0333-y (2020).

Filali-Mouncef, Y. et al. The ménage à Trois of autophagy, lipid droplets and liver disease. Autophagy 18 (1), 50–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2021.1895658 (2022).

Garcia-Estevez, L. & Moreno-Bueno, G. Updating the role of obesity and cholesterol in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 21 (1), 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-019-1124-1 (2019).

Molinaro, A. M., Taylor, J. W., Wiencke, J. K. & Wrensch, M. R. Genetic and molecular epidemiology of adult diffuse glioma. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 15 (7), 405–417. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-019-0220-2 (2019).

Liu, J., Lan, Y., Tian, G. & Yang, J. A systematic framework for identifying prognostic genes in the tumor microenvironment of colon cancer. Front. Oncol. 12, 899156. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.899156 (2022).

Roychowdhury, S., McMullen, M. R., Pisano, S. G., Liu, X. & Nagy, L. E. Absence of receptor interacting protein kinase 3 prevents ethanol-induced liver injury. Hepatology 57 (5), 1773–1783. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.26200 (2013).

Rivero-Ríos, P. & Weisman, L. S. Roles of PIKfyve in multiple cellular pathways. Curr. Opin. Cell. Biol. 76, 102086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceb.2022.102086 (2022).

Chow, C. Y. et al. Mutation of FIG4 causes neurodegeneration in the pale tremor mouse and patients with CMT4J. Nature 448 (7149), 68–72. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05876 (2007).

Campeau, P. M. et al. Yunis-Varón syndrome is caused by mutations in FIG4, encoding a phosphoinositide phosphatase. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 92 (5), 781–791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.03.020 (2013).

Osmanovic, A. et al. FIG4 variants in central European patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a whole-exome and targeted sequencing study. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 25 (3), 324–331. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2016.186 (2017).

Yang, M. et al. SLCO2B1 and SLCO1B3 May determine time to progression for patients receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 29 (18), 2565–2573. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2010.31.2405 (2011).

Li, J. et al. N6-methyladenosine-modified circSLCO1B3 promotes intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma progression via regulating HOXC8 and PD-L1. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 43 (1), 119. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-024-03006-x (2024).

van de Steeg, E. et al. Complete OATP1B1 and OATP1B3 deficiency causes human rotor syndrome by interrupting conjugated bilirubin reuptake into the liver. J. Clin. Invest. 122 (2), 519–528. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci59526 (2012).

Abe, T. et al. LST-2, a human liver-specific organic anion transporter, determines methotrexate sensitivity in Gastrointestinal cancers. Gastroenterology 120 (7), 1689–1699. https://doi.org/10.1053/gast.2001.24804 (2001).

Cao, Y. et al. Activating hotspot L205R mutation in PRKACA and adrenal Cushing’s syndrome. Science 344 (6186), 913–917. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1249480 (2014).

Lin, C. W. et al. Homogeneous antibody and CAR-T cells with improved effector functions targeting SSEA-4 glycan on pancreatic cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 118 (50). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2114774118 (2021).

Palencia-Campos, A. et al. Germline and mosaic variants in PRKACA and PRKACB cause a multiple congenital malformation syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 107 (5), 977–988. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.09.005 (2020).

Beuschlein, F. et al. Constitutive activation of PKA catalytic subunit in adrenal Cushing’s syndrome. N Engl. J. Med. 370 (11), 1019–1028. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1310359 (2014).

Sato, Y. et al. Recurrent somatic mutations underlie corticotropin-independent Cushing’s syndrome. Science 344 (6186), 917–920. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1252328 (2014).

Goh, G. et al. Recurrent activating mutation in PRKACA in cortisol-producing adrenal tumors. Nat. Genet. 46 (6), 613–617. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2956 (2014).

Ma, Q. et al. Far upstream element-binding protein 1 confers lobaplatin resistance by transcriptionally activating PTGES and facilitating the arachidonic acid metabolic pathway in osteosarcoma. MedComm (2020). 4 (3), e257. https://doi.org/10.1002/mco2.257 (2023).

Jakobsson, P. J., Thorén, S., Morgenstern, R. & Samuelsson, B. Identification of human prostaglandin E synthase: a microsomal, glutathione-dependent, inducible enzyme, constituting a potential novel drug target. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 96 (13), 7220–7225. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.96.13.7220 (1999).

Abraham, J. E. et al. Common polymorphisms in the prostaglandin pathway genes and their association with breast cancer susceptibility and survival. Clin. Cancer Res. 15 (6), 2181–2191. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-08-0716 (2009).

Versteijne, E. et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy versus immediate surgery for resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: results of the Dutch randomized phase III PREOPANC trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 38 (16), 1763–1773. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.19.02274 (2020).

Pereira, S. P. et al. Early detection of pancreatic cancer. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 5 (7), 698–710. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-1253(19)30416-9 (2020).

Dreyer, S. B. et al. Defining the molecular pathology of pancreatic body and tail adenocarcinoma. Br. J. Surg. 105 (2), e183–e191. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.10772 (2018).

Kang, J. S. et al. Radiological tumour invasion of Splenic artery or vein in patients with pancreatic body or tail adenocarcinoma and effect on recurrence and survival. Br. J. Surg. 109 (1), 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjs/znab357 (2021).

Montesion, M. et al. Somatic HLA class I loss is a widespread mechanism of immune evasion which refines the use of tumor mutational burden as a biomarker of checkpoint inhibitor response. Cancer Discov. 11 (2), 282–292. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-20-0672 (2021).

Amin, M. B. et al. The eighth edition AJCC cancer staging manual: continuing to build a Bridge from a population-based to a more personalized approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J. Clin. 67 (2), 93–99. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21388 (2017).

van Roessel, S. et al. International validation of the eighth edition of the American joint committee on cancer (AJCC) TNM staging system in patients with resected pancreatic cancer. JAMA Surg. 153 (12), e183617. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2018.3617 (2018).

Xu, M. et al. Mass spectrometric analysis of urinary N-Glycosylation changes in patients with Parkinson’s disease. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 14 (18), 3507–3517. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.3c00404 (2023).

Lin, M. C. et al. PGE(2) /EP(4) signaling controls the transfer of the mammary stem cell state by lipid rafts in extracellular vesicles. Stem Cells. 35 (2), 425–444. https://doi.org/10.1002/stem.2476 (2017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhaoda Deng wrote the main manuscript text and performed data analysis.Zitong, Yang performed RT-q-PCR experiments of the tumor sampleslincheng Li revised data analysis.Guineng Zeng and Zihe Meng prepared experimental related materials.Rong Liu reviewed and revised manuscript.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved and supported by the Ethics Committee of the PLA General Hospital (S2023-252-09) and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All informed consent was obtained from patients to participate in this study.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Deng, Z., Yang, Z., Li, L. et al. A lipid metabolism related gene signature predicts postoperative recurrence in pancreatic cancer through multicenter cohort validation. Sci Rep 15, 11683 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96855-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96855-1