Abstract

The current study explores the safety of Rasasindura (RS), an Ayurvedic herbo-metallic preparation containing mercury, and its therapeutic potential against oligospermia. Based on global concerns due to the toxicity of mercury, this study was designed to evaluate the toxicology and pharmacology of RS. Wistar rats were administered therapeutic and high doses of RS intragastrically for the in vivo toxicology study. The toxicity tests showed no significant changes in the major functions of organs, hematological and biochemical functions except mild hyperactivity in a few animals in the high dose group. The study’s histopathological and biochemical analyses revealed no significant morphological or functional abnormalities in the brain, liver, kidneys, or testes of rats administered with high doses of RS, indicating normal neuronal and organ function. Additionally, biochemical and hematological evaluations showed no adverse effects, suggesting RS does not impair metabolic activities at the tested doses. A therapeutic study was carried out in oligospermia-induced Swiss Albino mice. RS caused a significant increase in sperm motility and count and reduced sperm abnormalities in mice treated with lead acetate-induced oligospermia. The elevated levels of the genes Catsper and Calpain revealed that the formulation activates the calcium channels which contribute to an increase in sperm count. Further, microarray studies revealed potential anti-inflammatory, anti-obesity, anti-diabetic, anti-cancer, and immunomodulatory activities of RS. However, RS treatment also resulted in gene expression linked to possible toxic effects. Purified mercury-containing Ayurvedic preparations are safe at therapeutic concentrations if administered using a suitable vehicle; this is of great significance in reducing toxicity and enhancing efficacy, though higher concentrations could cause toxic effects mainly neurological, and hence the use of such potent metal-based medications are advised to be prescribed under medical supervision. To conclude, Rasasindura appears to be non-toxic at therapeutic doses and has shown promise the in treatment of oligospermia. Further studies could explore additional therapeutic effects and associated mechanisms for other disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ayurveda, a system of Indian traditional medicine encompasses the knowledge and approach to diagnose and treat illnesses and maintain well-being by the use of plants and mineral sources. It has been the primary source of healthcare for millions for thousands of years. However, there is a growing concern about the safety and efficacy of Ayurvedic formulations due to recent reports of metal contamination as well as the use of metal-based drugs1,2,3. Today, metal-containing medicines are banned in Western countries due to more than the permissible limit of heavy metal content4. Classical Ayurvedic texts describe stringent metal purification techniques, which are believed to nullify metal toxicity and transform them into medicine. The major flaw with traditional medicines is the lack of gold standards in the methods of preparation. The composition and constituents of the drugs may vary between different manufacturers and also within different batches of preparation of the same manufacturer. Traditional medicinal practitioners believe that adverse effects occur when metal-containing drugs are self-prescribed without medical consultation, drug misuse, drug abuse, or polypharmacy. Ayurvedic drugs containing metals are administered specifically with a vehicle like ghee, honey, milk, etc., that aid in drug absorption. This aspect, however, remains to be thoroughly explored in vivo. Although Ayurveda emphasizes stringent purification processes, which are expected to convert the metal into a biocompatible form, dearth of pharmacovigilance data in the traditional systems of medicine further compounds the problem.

Apart from evaluating the toxicological profile of such drugs, it has become necessary to investigate their therapeutic efficacy and mechanism of action. The chemical composition, chemical state, particle size and shape, vehicle, and route of administration are critical to determine the biological and pharmacological effects of such drugs. According to traditional medicinal practitioners, metal-containing medicines are not toxic since the metal is not present in the free form but exists in the form of sulphides5. It has been reported that the adverse effects at therapeutic doses of sulphide drugs like cinnabar are rare and generally reversible and tolerable6.

Mercury-based formulations are commonly used in Ayurveda. Since mercury is a highly toxic element, its use in medicine warrants concern. Rasasindura (RS) is one such mercury-containing drug belonging to the branch of Rasayana therapy that aims at enhancing physical and mental strength7. RS is primarily composed of mercuric sulphide (α-HgS) and other trace elements. It is employed for the treatment of various diseases like syphilis8, pleurisy, dyspepsia, dysuria, anemia, angina pectoris, tuberculosis, inflammation, and ulcers9. It is administered orally specifically with honey. In this work, we aim to investigate the toxicity/safety profile of RS prepared according to procedures described in classical texts. A 28-day sub-acute toxicity study on Wistar rats and a therapeutic study on a mice model of oligospermia were carried out to investigate the therapeutic benefits of RS against oligospermia. Also, the modulation of various gene targets by RS treatment was assessed through microarray analysis to identify other therapeutic benefits for this formulation. As calcium plays a crucial role in mammalian fertilization, the expression of genes encoding catsper 1, catsper 2 and calpain 1 was investigated to predict the plausible mechanism of action of RS (Figure: 1). We hypothesize that RS may play a role in activating CatSper channels causing an increase in the number of motile sperms which was validated in this study.

Materials and methods

Preparation process for RS

RS was prepared as per the procedure described in the classical texts Rasa Sastra and Aushadhi Yoga Sangraham (Singh, 2009). Mercury and sulphur were purified as mentioned in the texts. The term purification used in ancient texts could refer to removal of impurities, and transformation in crystalline phase or size. The purification process involved grinding mercury with calcium carbonate and then with rock salt and garlic. Washing with water separated pure mercury. We have carried out extensive physicochemical characterization of each intermediate during the preparation process (Supplementary Fig. 1). Purified mercury and sulphur were ground in a stone mortar till a black powder formed, to which an aqueous extract of aerial roots of Ficus bengalensis Linn. was added. This mixture was further ground to obtain a dried mass of black powder. A glass bottle was covered with seven layers of clay-smeared cloth and dried completely before filling it with black powder. The bottle was placed in an earthen pot and was filled with sand from the sides. The pot was heated intermittently using firewood for 30 h and then allowed to cool for 48 h. After 48 h of cooling, RS sublimed at the neck of the bottle, which was collected carefully and further ground into fine powder and stored in a tightly closed container.

Physicochemical characterization techniques, including scanning electron microscopy (SEM), selected area electron diffraction (SAED), x-ray diffraction (XRD), and x-ray fluorescence (XRF), were chosen due to their ability to provide complementary insights into particle morphology, crystalline structure, and elemental composition, which are critical for ensuring the consistency and safety of the formulation. Both SEM and XRD, which are industry-standard tools, were used for assessing structural integrity and phase identification of the metallic sulphide Rasasindura, ensuring reproducibility. XRF was employed to confirm elemental consistency and detect trace impurities, critical for the quality control of formulations containing heavy metals. For biological evaluation of the safety and therapeutic efficacy of the prepared RS, in vivo studies were performed in rodents. Repeated dose toxicity was selected to assess the safety profile as this will be similar to the dosage regimens prescribed to individuals. Microarray analysis was employed to evaluate molecular-level changes, providing insights into potential therapeutic mechanisms. The therapeutic study design, including specific doses and time points, was based on preliminary data from traditional usage patterns and prior scientific literature.

Electron microscopy

The surface morphology of the samples was imaged using cold field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, JSM 6701 F, JEOL, Japan). The sample was placed over a brass stub using carbon tape and a thin layer of platinum was sputter-coated over the sample. The images of the samples were acquired at an accelerating voltage of 3 kV. Selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns of the sample dispersed on a carbon-coated copper grid were analyzed using field emission transmission electron microscopy (JEM 2100 F, JEOL, Japan)10.

X-ray diffractometry

The crystallinity of the sample was analyzed using powder x-ray diffraction (D8 Focus, Bruker, Germany). The sample was irradiated with Cu-Kα radiation and the x-ray diffraction pattern was recorded between 2θ values of 10° to 60° at the scan rate of 0.01°/s.

Elemental analysis

The elemental composition of the sample was obtained through X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (XRF, S8 Tiger, Bruker, Germany) using a rhodium anode X-ray tube (4 kW).

In vivo toxicity study

Healthy Wistar rats (male and female) aged between 8 and 12 months of age and male Swiss Albino mice were procured from the central animal facility, SASTRA Deemed University. The experimental room was provided with 12 h of light and 12 h of door lighting condition using an automatic timer. Standard rodent pellet feed supplied by M/s. ATNT laboratories, Mumbai, India and Reverse Osmosis (RO) water were provided to the animals ad libitum. After the study period, all the animals were euthanized using CO2. All experimental procedures compiled with the ARRIVE guidelines and were reviewed & approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (IAEC) (ethics number: 120/SASTRA/IAEC/RPP, 284/SASTRA/IAEC/RPP) SASTRA Deemed University. All animal studies were performed following the CPCSEA guidelines in India (guide for the Care and use of laboratory animals).

28-day repeated dose toxicity study

An acute oral toxicity study for a period of 14-days was carried out initially at a high dose of 2000 mg/kg, wherein all animals survived with no toxic symptoms based on OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Sect. 4: Health Effects Test No. 425 (OECD TG 425, 2022)11. Sixty Wistar rats were used for the 28-day repeated dose toxicity study based on Test No. 407: Repeated Dose 28-day Oral Toxicity Study in Rodents, OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Sect. 4, OECD Publishing, Paris (OECD TG 407, 2008)12. The body weight of the animals ranged from 193 to 247 g for males and 139–183 g for females. The animals were randomly divided into four groups (control, low, medium, and high dose) and an additional two groups were kept as recovery (recovery control and high dose recovery) groups. The animals were housed in polypropylene cages and acclimatized for 5 days before dosing. They were kept in a 12 h light/dark cycle with 21 ± 2 °C temperature and fed with a standard rat feed pellet diet and deionised water ad libitum. RS was uniformly suspended in a vehicle (Honey and deionised water in a ratio of 2:3) and administered orally every day for 28 days. The therapeutic dose of RS in humans is 125 mg7. This human dose was converted to animal dose as mentioned elsewhere13 and was calculated to be 12.5 mg/kg. Keeping 12.5 mg/kg as the normal dose and making 4-fold increases, the medium and high doses were fixed as 50 mg/kg and 200 mg/kg, respectively. After 28 days of dosing, the animals in all groups were sacrificed, except the two groups of animals kept for recovery. The recovery control and the high dose recovery group animals were monitored without any further dosing for an additional 14 days and later sacrificed.

Experimental assessments

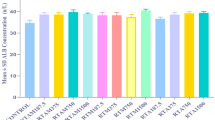

Body weight for all animals and feed consumption was measured daily. Blood was collected for analyzing hematological parameters. The animal tissues were processed for histopathological examination and all hematological parameters were determined using Mythic 22 Hematology Analyzer (Orphee SA, Switzerland). Albumin (ALB), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), total bilirubin (BIL), cholesterol (CHO), creatinine (CRE), glucose (GLU), total protein (TP) and urea were quantified using A15 Biochemistry full auto analyzer (Biosystems, Spain).

Histopathology

All the animals were euthanized using CO2 followed by blood collection and the gross necropsy of the major organs were carried out. The excised organs were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and dehydrated in progressively decreasing concentrations of ethanol followed by embedding in paraffin. The tissues were sectioned using a microtome, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and examined by optical microscopy. The H&E-stained slides were visually observed by three independent veterinary pathologists and scored independently using an ordinal grading system to exclude bias14.

Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) analysis

Mercury was quantified using LA-ICP-MS (XSeries 2, Thermo Scientific, Germany) after pressurized digestion of the tissue and fecal samples in a combination of ultra-pure nitric acid and 50% purified hydrogen peroxide in the ratio (4:1) using microwave digestor (Anton-Paar, Austria). Tissues from the liver, kidney, brain, spleen, and intestine from the 14-day study were analyzed.

Locomotor activity

The actophotometer test is an indicator of locomotor activity and alertness in rodents. The actophotometer (Khera Instruments, India) consisted of a rectangular box (30 × 30 × 30 cm) with a wire grid floor. Parallel infra-red beams were projected from one end to the other. The animals were individually placed in the box. The movement of the animal interrupted the beam of light incident on the photocell and a count was recorded digitally. The number of counts was directly correlated with the movement of animals15.

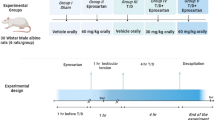

In vivo therapeutic study

A total of 25 male Swiss Albino mice with a body weight ranging from 40 to 50 g were selected and divided into five groups (n = 5). The first group of mice (vehicle control) received honey and deionised water in a ratio of 2:3 orally. The second group was treated with 75 mg/kg i.p of lead acetate (LA) once. The third group received 75 mg/kg i.p LA + 25.5 mg/kg p.o RS and the fourth group received 75 mg/kg i.p LA + 40 mg/kg p.o vitamin C as positive control. RS and vitamin C administration was carried out for 21 consecutive days after a single dose intraperitoneal administration of lead acetate on day 1. All the animals were sacrificed after 21 days. Testes were dissected and cleaned of accessory organs in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). For sperm count and abnormality studies, a suspension of the sperm in PBS was prepared from epididymis.

Sperm abnormality and sperm count

The caput and the cauda epididymis were excised in 1 mL PBS and then minced to release the spermatozoa. The tissue fragments were separated and 1% Eosin Y solution (10:1) was added and incubated for 30 min. Smears were prepared on clean, grease-free slides and air dried. 400 sperm cells per mouse were assessed and the sperm morphology was captured with a photomicroscope at 40X magnification. The same suspension without Eosin Y was employed for sperm counting using a haemocytometer and also to determine sperm motility.

Gene expression studies

Primers specific for mouse catsper1, catsper2, calpain-1, and β-actin were designed (Supplementary Table 1). Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, CA, USA) from testes and then extracted using RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Germany). RT-PCR was carried out using a SYBR®Green PCR kit (Qiagen, Germany) with the specific primers using Master cycler Realplex (Eppendorf, USA).

Microarray analysis

Microarray was performed as per manufacturer’s instruction (Affymetrix, USA) and outlined elsewhere16,17. Quality of the final cDNA was assessed using Bioanalyzer (Agilent technologies, USA) with internal controls. Expression analysis was performed using oligonucleotide microarrays (Affymetrix, USA) that can detect the expression of over 15,000 genes. Expression profiles were derived using GeneSpring GX Version 12.6 (Agilent technologies, USA) including percentile shift normalization. Spot intensity locations in an array were adjusted. This normalization adjusts intensities across the entire array to ensure comparability between arrays in the experiment. The percentile is calculated for the distribution of all probe intensities in the array. The effect of RS on gene expression in the liver was performed using the scaled control-treated expression levels as baseline values in the first instance and then using honey-treated expression levels as the baseline in the second instance. Genes not significantly detected above background signals in the comparison analysis were excluded. Fold values greater than 1.0 were taken as up-regulated and fold values less than 1.0 were taken as fold-reduction.

Statistical analysis

Differences between groups were evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnet’s post hoc. The significance level was set at 5% (p < 0.05).

Results & discussion

Figure 2A and B depict the scanning electron micrographs of RS. Particles were found to be in the range of 2–100 nm. The majority of the particles were uniform in shape and were arranged in regular arrays which may be attributed to the mechanical grinding used to bring about the formation of mercuric sulphide through mechanochemical activation. The SAED pattern of RS indicated the typical hexagonal arrangement of atoms for α-HgS (Fig. 2C). X-ray diffraction is another technique that can reveal the crystalline phases present in a sample10. The SAED data obtained for RS in the present study was substantiated further by powder X-ray diffraction, which indicated peaks with Miller indices of 100, 101, 003, 012, 103, 110, 111, 104, 021, 113, 015, and 006 which are characteristic of α-mercuric sulphide (ICDD PDF:89 − 048) (Fig. 2D).

In vivo toxicity study

The elemental analysis (Fig. 2E) shows that the major elements present in RS were mercury and sulphur which accounted for almost 99% of the sample. Manganese, iron, and calcium were present in trace amounts. The thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and Raman spectroscopy of RS are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2.

28-day repeated dose toxicity study

In both male and female animals, there was no significant difference in body weight from the controls in any dose group during the study period (Supplementary Fig. 3). This observation is in contrast to reports in the literature on toxicity of mercuric salts18,19. Chun-Fa Huang investigated the effect of cinnabar and other mercurial compounds on the active avoidance response, Na+/K+-ATPase activity and tissue mercury content in rodents 20 21 where it was reported that 1 g/kg cinnabar caused a prominent and irreversible decrease in body weight of rats. Our results indicate that RS, which is similar in chemical composition to cinnabar, does not affect the normal body weight gain in rats. It is correlated with an earlier study by Jie Liu et al.6 which found that cinnabar (containing alpha mercuric sulfide) is less toxic than other forms of mercury. Food intake in each dose group for both sexes was comparable to that of the control and no significant differences were recorded. No significant differences were found in the organ weights between the control and the RS-treated groups. All the animals in the recovery group survived and no adverse observations were recorded.

Histopathology

Though systematic reports on the influence of RS on the brain using histopathological observations are not available in the literature, the effects of mercury and its salts on the brain have been well documented. Mercury was found to be non-homogenously distributed in the brain of adult Wistar rats exposed to drinking water containing mercuric chloride (20 mg HgCl2/L) for an 8-month22. The highest deposition of mercury was found in the cerebral cortex. HgCl2 at a low dose of 0.375 mg/kg for a long-term induced hippocampal dysfunction which resulted in long-term and short-term memory impairment, oxidative stress, and apoptosis23. Many reports have suggested that mercury localizes in neurons and cytoplasm of glial cells24. In the present study, the brain sections of the control group showed normal neurons with prominent nucleoli, dispersed chromatin, cytoplasmic processes, and glial cells (Figs. 3A & B). No significant morphological changes were observed in the control and high-dose groups. Since the 200 mg/kg administered dose represents an 8-fold increase compared to the therapeutic dose, RS can be considered to be safe and relatively non-toxic at therapeutic dose levels.

Heavy metal toxicity has been known to damage hepatocytes resulting in metabolic dysfunction20. The rat hepatocytes exhibit radial organization of branched hepatic lobules with a prominent central vein20. It has been reported in the literature that, the HgCl2-administered rats suffered from the damage of liver tissue, with qualitative degenerative and necrotic changes20. Further reports indicate that the administration of HgCl2 to rats causes histopathological lesions such as central vein dilation, sinusoidal congestion, and cell necrosis in the liver25. In the present study, the liver sections of the control group revealed normal hepatocytes, terminal hepatic venule, and sinusoids (Fig. 3C and D). The rats administered with a high dose of RS did not exhibit any pathological changes in the liver compared to the control unlike other mercury compounds reported in the literature.

Elemental mercury is known to form a complex with albumin that enters the proximal tubules26. Hence in mercury-affected rats, deposits of mercury are normally observed in the proximal tubules. Rats injected with a concentration of 5 mg/kg HgCl2 displayed typical pathological features like Bowman’s capsule dilation, tubular degeneration, and glomeruli atrophy27. In the present study, the kidney section of the control group showed normal glomerulus and tubules containing low cuboidal and columnar epithelial cells with no discernible pathological lesions (Figs. 3E & F). No cell death or toxicity was observed in the high-dose group. The glomerulus and tubules appeared normal (without any deposits) in rats administered with a high dose of RS (Fig. 3F).

It has been reported that HgCl2 treatment results in intracellular accumulation of mercury in the interstitial cells of seminiferous tubules 28 29. Also, administration of methylmercury chloride and mercuric chloride in male rats at doses of 5, 10 mg/kg methylmercury or 50, 100 mg/kg and 50, 100 ppm HgCl2 for 90 days induced cellular disintegration of Leydig cells along with decreased sperm count, and accumulation of mercury in testes29,30. The histological study of mercury-affected rats reported elsewhere had shown that mercury produces extensive degeneration of the testes. Spermatocyte disintegration, necrosis, inhibition of spermatogenesis, apart from interstitial oedema are other typical signs of mercury-induced toxicity in rats31. Interestingly, in the present study, the histopathological investigation of the testes of RS-administered rats did not show any pathological changes compared to that of the control (Fig. 3G and H).

Representative histopathology images of brain (A) Control, (B) high dose of RS C: Cytoplasmic processes; G: Glial cells; N: Neurons; liver (C) Control (D) High dose of RS, H: Hepatocytes; S: Sinusoids; V: Central vein; Kidney (E) Control (F) High dose of RS, G: Glomerulus; T: Tubules; testes [G] Control [H] High dose of RS, dark arrows: seminiferous tubules; S; sperms.

It has been reported in earlier studies that the administration of HgCl2 to animals resulted in disturbances in the estrous cycle with deposition of mercury in the follicles32. The ovaries of mercury-treated animals have been reported to exhibit reduced follicular development and persistent corpora lutea33. However, no such pathological changes were observed in RS-administered rats in our study.

Altogether, histopathological and biochemical analyses revealed no significant morphological or functional abnormalities in the brain, liver, kidneys, or testes of rats administered with high doses of RS, indicating normal neuronal and organ function. The inflammatory scores were in the range of Grade 0 (minimal) to Grade 1 (mild) indicating there weren’t any inflammatory changes due to drug administration. Additionally, biochemical and hematological evaluations showed no adverse effects, suggesting RS does not impair metabolic activities at the tested doses.

ICP-MS analysis

The accumulation of mercury in various organs has been implicated as a possible reason for its toxic effects. Hence, ICP-MS was used to determine the concentrations of mercury in various organs 14 days after administration of a single dose of 2000 mg/kg body weight of the animal. The study was carried out using both mice (Albino Swiss) and rats (Wistar) and the results are shown in Fig. 4A and B.

Concentration of mercury up to 7 ppb was detected in rat kidneys, whereas less than 0.5 ppb Hg was detected in all the organs of the mice (Fig. 4A). Kidneys have been reported to be the primary target organ for the accumulation of inorganic mercury leading to toxic manifestations34. It has been reported by earlier researchers that after the initial hours of exposure to inorganic mercury, there is a rapid decrease in the plasma levels of mercury and an increase in the rate of uptake of inorganic mercury in kidney35. This is consistent with our findings where mercury accumulation is seen in kidney. It has also been reported that administration of mercuric sulphide in mice at a dose 10 times higher than that consumed by humans for 4–10 days did not show any significant change in glutathione activity as compared to control36,37. Such studies are consistent with our findings wherein histopathological findings reveal no toxic manifestations in the kidney. Yeoh et al.38 have reported that when cinnabar-containing diet was administered to mice for 5 days, only 0.02% of the dose was detected in the kidney. It has also been suggested that inorganic mercuric salts accumulated in the kidney are excreted in feces and urine with a half-life of about 2 months35. Chuu et al., have reported accumulation of 3 ppm mercury in mice kidneys after administration of 1000 mg/kg/day of mercuric sulphide for 7 consecutive days20 whereas our studies reveal 7 ppb of mercury in the kidney after 14 days of administering a single dose of 2000 mg/kg mercuric sulphide. Even though mercury was detected in the rat kidney after administration of a high dose (2000 mg/kg) of RS in the 14-day single-dose study, no histopathological changes were observed in the rat kidney treated with 200 mg/kg of RS in the 28-day repeated dosing study. This suggests the absence of free mercury or mercury ions in vivo post-administration of RS. This could be a major reason for the absence of significant toxicity to various organs in animals administered with RS.

(A). Concentration of mercury in organs of rodents (14-day toxicity study). The values have been expressed as Mean ± SD with n = 6 in each group. The concentration in kidney was found to be significantly (p < 0.05) greater than other organs, and is indicated by an asterisk (*). (B). Concentration of mercury in rodent feces (14-day toxicity study). Values have been expressed as Mean ± SEM with n = 6 in each group.

Figure 4B shows the elimination profile of RS through the fecal route and it is seen that it gets completely eliminated within 4 days of administration. Hence the detection of mercury in the kidney can be correlated to the presence of traces of mercuric sulphide and the absence of free mercury. The process of acid digestion of the samples during ICP-MS analysis results in the lysis of the mercury-sulphur bonds and hence direct confirmation of the presence of mercury as mercuric sulphide in the organs is not possible through ICP-MS.

The elimination of xenobiotics in mice has been reported to be generally faster when compared to a rat model. However, deviations from this trend have been observed based on the nature of the xenobiotic under investigation. It was observed in the present study that the concentration of mercury eliminated from mice was higher compared to rat (Fig. 4B). Concentrations higher than 300 µg/L are considered as the renal toxicity threshold level for mercury and toxic symptoms may occur in the kidney only after mercury excretion rises to these levels39. Also, it has been reported that the gut microflora converts methylmercury into inorganic mercuric mercury (Hg2+), which is poorly absorbed from the gut thus preventing it from entering enterohepatic circulation and causing an increase in mercury excretion through the fecal route40. Such an occurrence has been reported to be a beneficial toxicological consequence to the host. It has also been suggested that the demethylation of methylmercury to inorganic form by the gut flora prevents neurotoxic manifestations of methylmercury40. The absence of high levels of mercury in feces together with the histopathological observations that indicated no abnormal lesions in the brain tissue sections of rats treated with RS in the present work implies the absence of any form of organic mercury in the formulation.

Locomotor activity

During the observation period in the sub-acute toxicity study, four animals exhibited hyperactivity and hence an actophotometer test was performed to quantify the locomotor activity of the treated animals. Such studies have not been previously carried out for RS preparations. The count of animals administered with different treatments and those that served as the control was recorded for a period of 10 min (Supplementary Table 2).

Although an increase in locomotor activity was observed with an increasing dose of RS, the difference was not statistically significant. Behavioral abnormalities were recorded for 4 rats of which one belonged to the median dose (50 mg/kg) and three belonged to the high dose (200 mg/kg) group. Interestingly, no hyperactivity was observed in animals administered with the therapeutic equivalent dose of RS. Collectively, these results indicated that RS is safe at therapeutic doses but could cause CNS-related disturbances at doses four and eight-fold higher than the prescribed dose in a few cases. Measurements of spontaneous locomotor activity and active avoidance responses were used to evaluate neurotoxicity. The neurobehavioral toxicities of methylmercury (MeHg), mercuric sulfide (HgS), and cinnabar (naturally occurring HgS) in rats were examined by Chuu J et al.20. HgS and cinnabar were administered orally at 1.0 g/kg, whereas MeHg was administered intraperitoneally at 2 mg/kg for 13 days. Both MeHg and cinnabar resulted in notable and permanent weight loss, longer escape times from electric shocks, decreased conditioned avoidance response, impaired spontaneous movement, and decreased cerebral cortex Na+/K+-ATPase activity20. In contrast, HgS showed a reversible suppression of Na+/K+-ATPase activity and spontaneous locomotion. These results reported for HgS are consistent with our findings that therapeutic dose of RS did not cause behavioral abnormalities, including hyperactivity in certain rats. According to the study, the reversible nature of HgS influence on locomotor activity suggests that although HgS can alter CNS function, these effects might not be long-lasting and could vary depending on the dosage and length of exposure.

Microarray analysis

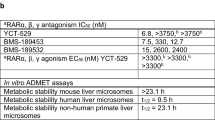

The main focus of this work is on evaluating the therapeutic effect of RS in treating oligospermia which is discussed in the in vivo therapeutic and gene expression sections. Additionally, microarray analysis was conducted to understand the effect of RS treatment on various gene targets and identify potential health risks and additional therapeutic benefits for future studies. The microarray analysis was performed on samples isolated from the liver of animals treated with therapeutic dose of RS. Traditionally, RS is administered in honey medium41. As honey also possesses several pharmacological activities, it becomes necessary to understand the effect of RS alone on the gene expression levels. Hence the study groups involved two sets of controls – untreated mice as well as honey-administered mice. The differential expression of genes in RS-treated mice were first compared with those of honey-administered animals. The heat map was generated by comparing the control and treatment groups and it is shown in Fig. 5A. Analysis of differentially expressed genes indicated that RS modulated genes are involved in a multitude of physiological processes such as oncogenic activity, adaptogen, immunity, glucose homeostasis, diabetes mellitus, metal transporters, inflammation, hypoxia/osmotic stress, liver fibrosis, schizophrenia, olfactory, hyperlipidemia, and sperm capacitation.

Figure 5B shows the expression changes leading to the up-regulation of genes exhibiting possible therapeutic aspects of RS.

Microarray profile of therapeutic dose of RS. (A) Heap map generated by comparing RS with control group. (B) Up-regulation of genes exhibiting possible therapeutic aspects of RS. IgJ, Defensin Beta 1, Gadd45g, Nbl1, Dusp14, Slpi, Tff3, Olfrl347, Lipin 1 was significantly upregulated compared to control with P < 0.05. *denotes P < 0.05.

Potential antibacterial and immunomodulatory role

RS administration resulted in the up-regulation of genes that encode for immune response and adaptogen activity. Induction of immunoglobulin J (IgJ or J-chain) indicates possible recruitment of IgA and IgM antibodies by RS administration. RS induced the expression of beta defensin-1 with a fold change > 2, which was statistically significant with respect to the untreated controls (p < 0.05). Beta defensin-1 is a small peptide having a broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity42. It recruits immune cells and acts as an immunomodulatory43. Also, beta-defensin acts as a therapeutic target for enhancing natural immunity and reducing the pathogenic burden42. RS belongs to the class of Rasayana therapy, wherein drugs are prescribed for longevity and immunity against diseases. Dwivedi et al.. (2012) studied the effect of RS supplementation on thermo-tolerance in Drosophila melanogaster and found that RS supplementation improved their tolerance levels7. Our findings corroborate with the Ayurvedic literature, as well as studies conducted thus far on RS by other researchers. RS had also been prescribed for the treatment of syphilis, a sexually transmitted disease caused by Treponema pallidum. In addition, RS has been routinely prescribed by traditional medicine practitioners to treat urinary tract infections44. The induction of the anti-microbial beta -defensin gene expression by RS suggests that this is a probable mechanism responsible for the anti-microbial activity of RS.

Potential anti-diabetic effects

RS was observed to induce the expression of B-cell translocation gene 2 (Btg2) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PPARGC-1α). Apart from its antiproliferative properties, Btg2 has been mainly implicated in diabetes treatment45. It has been also demonstrated that Btg2 interacts with Nur77 and mediates gluconeogenic genes in the liver. RS also up-regulated PPARGC-1α, a transcriptional coactivator of mitochondrial genes whose expression is decreased in type 2 diabetes46. PPARGC-1α is also believed to activate other metabolic pathways like ketogenesis and fatty acid oxidation47. Traditionally, RS has been also employed to treat Madhumeha or diabetes and the activation of PPARGC-1α suggests that it may be part of the liver metabolic gene network facilitating the anti-diabetic activity of RS.

PPARGC-1α is also considered to be a major target for treating obesity. Obesity is characterized by an excess of white adipose tissue, which contains triacylglycerols. On the other hand, brown adipose tissue is essential for dissipating the fat in the form of thermogenic energy and thus fat reduction48. PPARγ is required for brown fat formation and differentiation49. Activation of PPARGC-1α by RS indicates the formulation can be used to treat diabetes mellitus and also obesity. Indeed, the literature mentions that RS formulations have been also employed as anti-obesity agents50. Interestingly, RS administration was found to up-regulate the expression of the Lipin1 gene by more than 2.5 folds. Lipin1 and PPARGC-1α are closely associated with hyperlipidemic conditions. Fold-reduction is observed in both genes involved in hypertriglyceridemia and drugs which prevent this suppression can be used to treat hyperlipidemia51. Lipin1 is also known to induce PPARγ gene expression and forms a complex with PPARGC-1α leading to fatty acid oxidation49. Our study reveals that RS displays a tendency to up-regulate the expression levels of PPARGC-1α and Lipin1, indicating it could possibly play a role in controlling hyperlipidemia and may have implications on its ability to counter both diabetes as well as obesity-related disorders, which could be explored in future studies. Fold-reduction was observed in WNT1 inducible signaling pathway protein 2 (WISP2) expression by RS. It is found that accumulation of ectopic fat, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome can be prevented by WISP2 inhibition52. Thus, WISP2 may be a novel target for anti-obesity drugs.

Anti-cancer potential and liver regeneration

RS was found to significantly up-regulate the expression of Gadd45g (Growth arrest and DNA damage inducible, gamma), a gene that is involved in cell growth arrest during DNA damage53. The enhancement of Gadd45g levels by RS suggests that RS may possess anti-cancer potential – a facet that needs to be explored further. Gadd45 family of genes has been shown to exhibit different functions in normal and diseased cells. While its pro-apoptotic nature has been documented in several forms of cancer54 in normal liver cells, Gadd45 has been linked with the promotion of cell survival, growth, and proliferation thus promoting liver regeneration55. The augmentation of Gadd45g expression in the liver by RS may, therefore, also have implications on its widespread use as a rejuvenating formulation in Ayurveda. The expression of NBL1 (neuroblastoma, suppression of tumorigenicity 1) gene exhibited a 1.38 positive fold change when compared to the control in RS administered group. Recently, it has been found that up-regulation of BMP antagonists contributes to liver regeneration by promoting hepatocyte proliferation56. Thus, the up-regulation of NBL1 as in the case of Gadd45g may contribute to the rejuvenation property of RS. RS also resulted in the up-regulation of dual specificity phosphatase 14 (DUSP14), an inhibitor of TNF and IL-1 that are responsible for the activation of the NF-κB pathway. DUSP14 binds to transforming growth factor β activated kinase-1 (TAK1) and leads to its dephosphorylation, which inhibits TNF and IL-1-induced NF-κB activation thus acting as an anti-inflammatory target57. Due to the inhibition of TNF through DUSP14, RS also has a role in anti-inflammatory activity58. DUSP14 also regulates the activity of MAP kinases (MAPKs), which control cell growth and survival in cancer59. Collectively, these data suggest that RS could help in the recovery of liver from stress and may also exhibit anti-cancer property. Though unreferenced reports have suggested that RS may be used as an adjuvant in cancer therapy, the general therapeutic benefits of RS have been mainly anti-infection, improvement of immune system, and rejuvenation. Additional experiments may be required to confirm possible anti-cancer effects observed in the present study.

Fold-reduction was observed in the expression of the cysteine-rich protein 61 (Cyr61), which is a heparin-binding protein belonging to the CCN family and is associated with the extracellular matrix. In addition to imparting resistance to cancer cells, Cyr61 has been implicated in promoting angiogenesis and migration60. RS may exhibit anti-cancer effects through fold-reduction of Cyr61 expression, a facet that needs to be explored further in the future. RS significantly reduced T-box3 expression, which has been reported to be aberrantly increased in various cancers and is also involved in metastasis and cell invasion61. RS administration resulted in fold-reduction of oxidative stress induced growth inhibitor 1 (OSGIN1). OSGIN1 expression has been reported to be significantly up-regulated during DNA damage and enhance mitochondria permeability and induce cell apoptosis61. Overexpression of OSGIN1 has been shown to increase intracellular levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Thus, OSGIN1 is implicated as a therapeutic target for both cancer treatment and inflammation62. RS also resulted in fold-reduction of another cancer marker, paired domain transcription factor (PAX2). PAX2 expression has been reported in breast tumors and contributes to proliferation, cell survival, differentiation and apoptosis63. Suppression of PAX2 by RS could possibly lead to anticancer efficacy. Fold-reduction of Glutathione peroxidase 2 (GPX2) expression was observed. GPX2 expression has been shown to be induced in intestinal mucosa during bacterial infection64 and has also been implicated in several cancers65. However, this facet needs to be further explored in future for better clarity.

Potential anti-inflammatory effects

Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI) was up-regulated by RS. SLPI is known to inhibit neutrophil elastase and cathepsin G. Both neutrophil elastase and cathepsin G are up-regulated in inflammation and participate in destroying host tissue as well as pathogens66. SLP1 gene is therefore a possible molecular target through which RS may exert anti-inflammatory and anti-bacterial properties. Trefoil factor 3, intestinal (Tff3) gene was also found to be up-regulated in RS-administered animals. Tff3 plays a role in the protection of the gastrointestinal tract67. Tff3 overexpression has been experimentally demonstrated to promote mucosal defense and heal colitis68. RS has been usually prescribed to treat colicky abdominal pain and as an anti-inflammatory agent, the mechanism of which may involve SLPI.

Supplementary Fig. 4 shows the expression changes leading to fold-reduction of genes exhibiting possible therapeutic aspects of RS. RS was found to affect several inflammatory markers, which could possibly be responsible for its therapeutic effects. RS administration resulted in fold-reduction of IFN-γ-inducible protein 10 (IP-10/CXCL10). This chemokine is up-regulated in acute and chronic liver injury and recruits leukocytes to the liver parenchyma69. Recently, it was demonstrated using CXCL10 knockout mice that suppression of this gene prevents liver inflammation during ischemia and reperfusion injury, thereby highlighting the importance of this gene as a target for anti-inflammatory effects. RS administration resulted in significant fold-reduction of Microsomal glutathione S-Transferase 2 (MGST2). MGST2 is known to synthesize leukotriene C4 (LTC4) during inflammation70. Suppression of MGST2 by RS could possibly prevent LTC4 synthesis and inhibit the inflammatory process. Fold-reduction was also observed in glycolipid transfer protein domain-containing protein 1 (GLTPD1) which is involved in the mediation of ceramide-1-phosphate transfer between cell membranes intracellularly thereby regulating phospholipase PLA2G4A activity and release of pro-inflammatory arachidonic acid71. RS decreased the expression levels of the gene encoding for Z-DNA-binding protein 1 (ZBP1). ZBP1 overexpression has been reported during bacterial infection along with IFNβ induction72. Taken together, these data suggest that RS possesses strong anti-inflammatory properties that could contribute to its reported therapeutic activity in traditional medicine.

Potential reproductive effects

RS suppressed the expression of seminal vesicle autoantigen (SVA). SVA is the major protein of seminal plasma and is secreted from the luminal epithelium present in the primary and secondary folds of the seminal vesicle. It is reported to bind to sperm membrane phospholipids and suppress sperm motility. Fold-reduction of SVA suggests that RS may have a role in promoting sperm motility and this effect is also believed to facilitate sperm capacitation. The capacity of spermatozoa to fertilize an egg depends upon its ability to remain fertile in the female uterine tract73. SVA molecules adhere to the spermatozoan surface by phospholipid interaction. When spermatozoa are propelled by the contraction of the female uterine tract to reach the site of fertilization, the inhibition of the SVA effect is essential to maintain sperm motility74. The possibility of RS modulating sperm motility may be useful in the treatment of oligospermia, which has been chosen for further validation in the present study.

Potential toxic effects

The microarray analysis also reveals alterations in the expression levels of a few genes by RS that may lead to toxic manifestations. Expression changes leading to up-regulation of genes exhibiting negative aspects of RS are depicted in Supplementary Fig. 5A. It was observed that RS induced up-regulation of mesothelin, a glycoprotein of 40 kDa expressed in normal cells and overexpressed in certain types of tumors such as liver carcinoma75, pancreatic carcinoma by binding to MUC16 (CA125)76. In addition it has a role in cancer cell proliferation and invasion by interacting with PI3K-NFκB pathway77. RS administration resulted in a 1.5-fold change in mesothelin expression.

Among the genes in which fold-reduction was observed, there were a few genes whose expression levels could result in undesirable effects of RS. Expression changes leading to fold-reduction of genes exhibiting possible toxicity aspects of RS are shown in Supplementary Fig. 5B. Fold-reduction was observed in the arrestin family member ARRDC3 by RS. ARRDC3 has been shown to negatively regulate tumor growth by affecting integrin beta 4 (ITGβ4) levels78. ARRDC3 is also involved in oxidative stress and redox signaling via interacting with TXNIP, a downstream protein79. As a result, RS-induced ARRDC3 fold reduction may have a function in tumor growth, but it also plays a role in redox signaling. Fold-reduction in the levels of the Hamp gene which encodes hepcidin was noted. Hepcidin regulates iron homeostasis and hepcidin expression has been found to be inhibited or absent in iron overload conditions80. On the contrary, even excess hepcidin levels cause disorders like chronic kidney disease and iron-refractory iron deficiency anemia80. Thus, RS by fold-reduction of hepcidin may result in iron-imbalance in the body. Toxicity from the iron dyshomeostasis resulted in neurological, inflammatory disorder81. RS resulted in the repression of gamma interferon-inducible GTP-binding protein (IGTP). It is a member of the gamma interferon (IFN-γ)-induced GTPase family and plays an important role in host immune response82. IGTP deficient mice are be prone to infection, though it is known to be pathogen specific83. For example, IGTP -deficient mice are resistant to Listeria monocytogenes but develop infection against Toxoplasma gondii83. Thus RS, could result in immune compromise by repressing IGTP.

Significant fold-reduction in the expression of G0/G1 switch gene 2 (G0S2) was observed, which also inhibits lipolytic enzyme adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) apart from regulation of the cell cycle84. It remains to be explored whether fold-reduction in G0S2 contributes to increased lipolysis associated with obesity. Additionally, G0S2 can interact with the BCL2 domain and inhibit its antiapoptotic action in cancer cells; as a result, RS-mediated G0S2 repression promotes invasion and cell proliferation85. Significant fold-reduction in the expression levels of the phosphoserine aminotransferase (PSAT1) was found. Fold-reduction in PSAT1 is associated with schizophrenia through serine metabolism86. However the PSAT1 inhibited the cell proliferation, migration in non-small cell lung cancer87, epithelial ovarian cancer88 and it’s a candidate target for pulmonary fibrosis through p38 and ERK1/2 89. Further studies need to be carried out to establish the molecular implications of RS through fold-reduction of PSAT.

The above data clearly reveal that few genes downregulated by RS resulted in inflammatory, neurological diseases, and cancer, but those detrimental effects were offset by the fold reduction of other genes by RS, which resulted in reduced inflammation and cancer cell proliferation.

Metal-detoxification potential

RS induced the expression of metallothionein-2, a cysteine-rich low molecular weight protein which has been implicated in mercury detoxification (Supplementary Fig. 5A)90. Up-regulation of MT in the cells has been shown to protect against toxicity of heavy metals91. Since RS contains mercury in the form of sulphide, the possibility of the release of free mercuric ions in vivo is minimal. In such a scenario, the alternative explanation for the induction of MT2 by RS could be due to osmotic stress. RS induced the expression of DNA damage-inducible transcript 4 (Ddit4), which is a stress response gene involved in the regulation of the mTOR pathway92. It is induced in hypoxia, glucocorticoid treatment, and oxidative stress and the expression of Ddit4 was 2 fold higher than MT2 expression and statistically significant compared to the control (p < 0.05)93,94.

In vivo therapeutic study

The in vivo toxicity studies have demonstrated that RS is non-toxic at therapeutic doses. The microarray analysis suggests that RS may possess potential benefits in oligospermia. Hence, experiments were designed to evaluate its therapeutic efficacy against oligospermia using animal models. The present work focused on evaluating the therapeutic efficacy of RS in treating oligospermia, a condition of reduced sperm count which leads to infertility issues and also conditions of decreased sperm motility. The experiments were designed to induce oligospermia in mice through administration of lead acetate followed by treatment with RS. Vitamin C treatment was used for comparison. (Table 1) shows the sperm count in different groups after 21 days of treatment. Lead acetate treated mice showed a 77.6% decrease in sperm count compared to control. After oral dosing of RS, a significant increase in sperm count was observed which was comparatively higher than the Vitamin C treated group. Further, the number of sperm abnormalities was recorded in each group. The number of motile and non-motile sperms was counted in each group (Table 1).

It is evident from Table 1 that a significant decrease in sperm abnormalities and an increase in motility was observed in animals treated with RS compared to the lead acetate treated group. Although the values were still lower than the normal levels in the RS-treated group, the improved sperm number, motility and morphology observed in the animals treated with RS suggests that an increased duration of treatment could possibly restore the sperm count closer to normal values. The results of this study indicate that RS exhibits therapeutic efficacy in treating sperm abnormalities.

Figure 6 shows the representative images of sperm morphology observed in different groups. It was observed that the normal mice sperm consists of two parts – a head with a characteristic hook and a tail95. Treatment with lead acetate causes significant changes in the morphology of the sperm. Figure 6 reveals the presence of abnormal sperm morphologies such as coiled tail, tail-less heads and amorphous heads in lead acetate treated animals. Treatment with RS results in a reduction in these abnormalities with a significant number of populations with normal morphologies discernible in the micrographs. The vitamin C treated group however revealed a considerable number of sperms with abnormal morphology and only a small population with normal morphology. This difference in the therapeutic efficacy of RS and vitamin C suggests that they possess different mechanisms of action. Earlier studies have suggested that the anti-oxidant property of vitamin C is responsible for its therapeutic effect in sperm disorders96. Our data implies that anti-oxidant properties might not be the reason for the observed therapeutic effect of RS in oligospermia.

Representative images of sperm morphology of (A) Control; (B) Lead acetate; (C) Lead acetate + Rasasindura; (D) Lead acetate + Vitamin C. The arrows indicated in (A) represent normal sperm architecture, the dotted arrow in (B) indicates coiled sperms, in (D) the circled image indicates a broken head and the arrow indicates a sperm with amorphous head. (E–F) are magnifications from (A–D) respectively.

The species (rats for the 28-day repeated-dose toxicity study and mice for the therapeutic study) was chosen based on specific experimental and scientific rationales relating to study objectives, species-specific sensitivity, and practicality. Rats are the standard model for toxicity studies under OECD criteria (Test No. 407). They provide robust data on systemic toxicology, including organ function, hematological and biochemical parameters. Rats provide adequate sample volumes for blood and biochemical analyses, enabling detailed assessments. They are more frequently used in toxicological research, and there is an extensive database for interpreting results97. They are often considered more sensitive to chronic exposures. While rats are a standard model for OECD 407 studies, their use in this study has certain limitations in predicting long-term toxicity, human metabolism, and specific organ system effects. Hence, long-term studies are required to substantiate the toxicological findings in a short-term study.

Mice are often utilized in fertility and reproductive studies. Their well-characterized reproductive physiology is suitable to assess sperm function and motility98,99,100. Further, mice require less chemical for dosing and are easier to maintain for RT-PCR and microarray analysis. However, there are also limitations of using Swiss albino mice in such studies because the response of mice to certain drugs may not accurately reflect human responses. This study involved short-term drug exposure and its effect on sperm parameters which may not capture potential long-term effects.

Gene expression studies

The possible mechanism of action for RS in oligospermia was investigated using gene expression levels in the testes of the animals in different treatment groups. Catsper gene is expressed exclusively in testes and it is localized in the sperm tail, functioning to open Ca2+ channels and influx leading to increased motility92. The expression levels of catsper1 mRNA in the lead acetate (LA) + RS group showed a 40-fold increase compared to the control (normal animals), whereas the LA + Vitamin C group showed only a 2-fold increase in expression compared to the control (Fig. 7A). This may be the reason for the superior sperm motility observed in animals treated with RS when compared with those treated with vitamin C.

Similarly, the amount of catsper2 mRNA in LA + RS group showed 2.6-fold increase in expression compared to control (normal) animals, whereas the LA + Vitamin C group exhibited only a 0.5-fold increase in expression levels (Fig. 7B), indicating that RS increased sperm motility through elevation of Catsper genes.

(A) The relative mRNA expression of catsper1 in mice testes. (B) The relative mRNA expression of catsper2 in mice testes. (C) The relative mRNA expression of calpain1 in mice testes. The gene expression of all three markers was normalized against β-actin. Results are expressed as Mean ± SD. *Significant difference than the at p < 0.05.

Calpain1 expression levels in the LA + RS group was 40-fold higher than that of the control similar to catpser1 levels, whereas the LA + Vitamin C group exhibited a 5.5-fold increase compared to the lead acetate control (Fig. 7C). Calpain1 is an intracellular calcium dependent cysteine protease which is localized in the sperm head and plays an active role in mammalian fertilization101. The elevated levels of the genes Catsper and Calpain revealed that the formulation activates the calcium channels which contribute to reduced sperm abnormalities as well as improved motility and count. The increased expression levels of catsper1, catsper2, and calpain1 by RS indicate that it increases sperm motility probably through the Ca2+/Calmodulin pathway.

However, this research work has some limitations which can be addressed in future studies involving comprehensive pre-clinical and clinical trials. While no significant changes in biochemical, hematological, or major organ functions were observed, the study primarily noted minor hyperactivity at high doses. A more comprehensive investigation into long-term toxicity, especially on neurological and reproductive systems, would strengthen conclusions. The study identifies potential benefits at therapeutic doses, however, a detailed exploration of the dose-response relationship and safe upper limits for human application needs to be explored for clinical translation. While the study provides promising insights into Rasasindura’s therapeutic potential and safety at therapeutic doses, it requires further comprehensive research, including detailed mechanistic studies, and long-term toxicity assessments, to confirm its findings and address the outlined limitations.

While we acknowledge the gap in scientific validation using modern methodologies, the historical context offers evidence of safety when RS is prepared and administered correctly. Mercuric sulfide (also known as Parada bhasma in Ayurveda or Zhu Sha in Traditional Chinese Medicine) has been used for centuries. The preparation involves sophisticated and well-documented detoxification (e.g., Shodhana) and calcination (Marana) procedures that transform elemental mercury into its inert and insoluble form. This process has been shown to reduce potential toxicity significantly. The use of these preparations in India and China is not anecdotal but supported by millennia of clinical experience. Mercuric sulphide prepared through traditional methods has unique physicochemical properties that distinguish it from free mercury or methylmercury: Mercuric sulphide is highly insoluble in water and other biological solvents, which reduces systemic absorption and free mercury release. We agree that mercury in its free form is toxic. However, the preparation process results in formation of the inert mercuric sulphide form. Scientific studies have begun to support this claim, with research demonstrating that traditionally prepared mercuric sulphide does not behave like free or organic mercury in biological systems. Our findings are based on controlled experimental data in animal models. The authors do not claim universal safety or efficacy of RS but present observations within the scope of the study. We recognize the need for further studies to clarify the metabolic fate of mercuric sulphide, but our data strongly indicate its safety when prepared as per Ayurvedic protocols. We acknowledge the broader issue of scientific validation in traditional medicine. This is indeed a challenge due to differences in philosophical and methodological paradigms between traditional systems and modern regulatory frameworks (e.g., WHO, FDA). Our work represents an attempt to bridge this gap by subjecting traditional formulations to modern experimental scrutiny. The lack of scientific validation does not negate the safety and efficacy of these formulations; it highlights the need for more rigorous studies to translate traditional knowledge into a format compatible with modern standards.

The merging of traditional and modern medicine has become more of a debate, due to differences in fundamental principles, mechanism of action, and validation methods. Traditional medicine, such as Ayurveda, applies a holistic approach, emphasizing personal treatment based on an individual’s constitution (Prakriti) and balance of the three doshas (Vata, Pitta, and Kapha). Modern medicine, on the other hand, relies on standardized treatment protocols formulated on the logical basis of rigorous clinical trials with evidence-based and molecular mechanisms of action.

One major strength of traditional medicine lies in its historical continuity and centuries-gathered empirical knowledge. Many of the traditional formulations comprising of herbs and minerals have shown a beneficial therapeutic effect on the long-term management of diseases, improvement of immunity, and general well-being. But one of the most factors that weaken traditional systems of medicine is its lack of uniform standardization and quality control, with the added effect of limited scientific studies on efficacy and safety as per modern regulatory standards. This is compounded by a lack of rigorous pharmacovigilance and the varying methodologies of preparation by different manufacturers. On the contrary, modern medicine is derived from clearly defined methodologies for reproducibility and objective validation of drug safety and efficacy. The stringent regulatory framework brings about uniformity and minimizes the risk of toxicity. However, modern pharmacology focuses on symptoms rather than holistic healing, a limitation to its efficacy in chronic and multifactorial diseases. Modern pharmaceuticals frequently generate side effects requiring complementary approaches to mitigate risk.

This study is an attempt to evaluate both pharmacological and toxicological profiles of RS through modern scientific methodology to bridge the gap between the two medical paradigms. The findings indicate that RS when administered at therapeutic doses, does not exhibit significant toxicity in laboratory animals. Despite these promising findings, challenges do remain in integrating traditional and modern systems of medicine. Regulatory harmonization is required to develop standardized protocols for the preparation and evaluation of traditional formulations. Interdisciplinary research should focus on understanding molecular mechanisms underlying traditional remedies, thereby facilitating their transition into modern medical practice.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrates that Rasasindura does not exhibit any toxic effects on laboratory animals at therapeutic doses. No toxic manifestations were observed in the histopathology of major organs even at very high doses, which is 8-fold higher than the therapeutic dose. Although clinical signs of hyperactivity and abnormal behavior were observed in few animals at high doses that are 4-fold and 8-fold higher than the therapeutic dose, no abnormality was observed at therapeutic doses indicating that RS could cause CNS disturbances only at higher doses. Mercury was detected in the kidney of rats treated with 2000 mg/kg of the drug in the 14-day single dose study. A study of literature reveals that in most of the studies conducted thus far using inorganic mercury, a very high dose of mercury has been administered and also the duration of treatment was longer, invariably resulting in toxic manifestations of mercury. The present study is the first of its kind to attempt to unravel the mechanism of action of RS against sperm disorders. RS exhibited therapeutic efficacy in treating lead acetate induced reproductive toxicity. The mechanism of increase in motility by RS can be attributed to activation of Ca2+ channels. Microarray analysis has revealed the anti-inflammatory, anti-obesity, anti-diabetic, anti-cancer, and immunomodulatory effects of RS, that need to be established through systematic studies using appropriate in vitro and in vivo models. Thus, our study highlights the importance of RS in traditional medicine and its potential roles in contemporary era. Even though this study highlights the safety and efficacy of RS, further research should focus on long-term toxicity and mechanistic studies to further validate its therapeutic applications. Investigating its molecular interactions and metabolic fate will be essential for translating these findings into clinical practice. To conclude, our study underscores the significance of RS in traditional medicine and attempts to bridge the gap between ancient wisdom and modern scientific validation. This research paves the way for further exploration of metal-based Ayurvedic formulations in evidence-based medicine.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- RS:

-

Rasasindura

- SAED:

-

Selected area electron diffraction

- HgCl2 :

-

Mercuric chloride

- LA:

-

Lead acetate

- LA-ICP-MS:

-

Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry

- Btg2:

-

B-cell translocation gene 2

- PPARGC-1α:

-

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha

- Gadd45g:

-

Growth arrest and DNA damage inducible gamma

- NBL1:

-

Neuroblastoma, suppression of tumorigenicity 1

- TNF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor

- IL 1:

-

Interleukin 1

- NF-κB:

-

Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- MAPKs:

-

Mitogen activated protein kinases

- SLPI:

-

Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor

- IP10:

-

IFN-alpha-inducible protein 10

- MGST2:

-

Microsomal glutathione S-Transferase 2

- ATGL:

-

Adipose triglyceride lipase

- ARRDC3:

-

Arrestin Domain Containing 3

- mTOR:

-

Mechanistic Target Of Rapamycin Kinase

References

Saper, R. B. et al. Heavy metal content of ayurvedic herbal medicine products. JAMA 292, 2868–2873 (2004).

Mikulski, M. A. et al. Toxic metals in ayurvedic preparations from a public health lead poisoning cluster investigation. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health. 23, 187–192 (2017).

Saper, R. B. et al. Lead, Mercury, and arsenic in US- and Indian-Manufactured ayurvedic medicines sold via the internet. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 300, 915–923 (2008).

Sahoo, N., Manchikanti, P. & Dey, S. Herbal drugs: Standards and regulation. Fitoterapia 81, 462–471 (2010).

Liu, J. et al. A review of cinnabar (HgS) and/or Realgar (As4S4)-containing traditional medicines. J. Ethnopharmacol. 210, 340–350 (2018).

Liu, J., Shi, J. Z., Yu, L. M., Goyer, R. A. & Waalkes, M. P. Mercury in traditional medicines: Is cinnabar toxicologically similar to common mercurials? Exp. Biol. Med. Maywood NJ 233, 810–817 (2008).

Dwivedi, V. et al. In vivo effects of traditional ayurvedic formulations in drosophila melanogaster model relate with therapeutic applications. PLoS ONE. 7, e37113 (2012).

Singh, S. K., Chaudhary, A., Rai, D. & Rai, S. Preparation and characterization of a mercury based Indian traditional drug. 8, (2009).

Ruknuddin, G., Gokarn, R., BJ, P. & Prajapati, P. Review on Rasa sindhura - A mercurial preparation of Indian system of medicine. Int. J. Pharm. Biol. Achieves. 3, 1360–1367 (2012).

Karunakar, K., Cheriyan, K., B, A. & B. V., R, K., M, G. & Therapeutic advancements in nanomedicine: the multifaceted roles of silver nanoparticles. Biotechnol. Notes 5, 64–79 (2024).

OECD. Test No. 425: Acute Oral Toxicity: Up-and-Down Procedure (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2022).

OECD. Test No. 407: Repeated Dose 28-Day Oral Toxicity Study in Rodents. OECD, (2008). https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264070684-en

Reagan-Shaw, S., Nihal, M. & Ahmad, N. Dose translation from animal to human studies revisited. FASEB J. Off Publ Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 22, 659–661 (2008).

Schafer, K. A. et al. Use of severity grades to characterize histopathologic changes. Toxicol. Pathol. 46, 256–265 (2018).

Raj, P. V., Nayak, N. M. R., Rao, S. & R. P. & N. A study on anxiolytic activity and locomotor behavior of curcuma Amada rhizomes using Wistar albino rats. Int. J. Basic. Clin. Pharmacol. 7, 1557–1560 (2018).

Lockhart, D. J. et al. Expression monitoring by hybridization to high-density oligonucleotide arrays. Nat. Biotechnol. 14, 1675–1680 (1996).

Wodicka, L., Dong, H., Mittmann, M., Ho, M. H. & Lockhart, D. J. Genome-wide expression monitoring in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat. Biotechnol. 15, 1359–1367 (1997).

Khan, A. T., Atkinson, A., Graham, T. C. & Shireen, K. F. Uptake and distribution of mercury in rats after repeated administration of mercuric chloride. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part. Tox Hazard. Subst. Environ. Eng. 36, 2039–2045 (2001).

Al-Madani, W. A., Siddiqi, N. J. & Alhomida, A. S. Renal toxicity of mercuric chloride at different time intervals in rats. Biochem. Insights 2, (2009). BCI.S2928.

Chuu, J. J., Liu, S. H. & Lin-Shiau, S. Y. Effects of Methyl Mercury, mercuric sulfide and cinnabar on active avoidance responses, Na+/K+-ATPase activities and tissue mercury contents in rats. Proc. Natl. Sci. Counc. Repub. China B. 25, 128–136 (2001).

Huang, C. F., Hsu, C. J., Liu, S. H. & Lin-Shiau, S. Y. Exposure to low dose of cinnabar (a naturally occurring mercuric sulfide (HgS)) caused neurotoxicological effects in offspring mice. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 254582(2012). (2012).

Møller-Madsen, B. & Danscher, G. Localization of mercury in CNS of the rat. I. Mercuric chloride (HgCl2) per Os. Environ. Res. 41, 29–43 (1986).

Aragão, W. A. B. et al. Hippocampal Dysfunction Provoked by Mercury Chloride Exposure: Evaluation of Cognitive Impairment, Oxidative Stress, Tissue Injury and Nature of Cell Death. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 7878050 (2018). (2018).

Pamphlett, R. & Bishop, D. P. Mercury is present in neurons and oligodendrocytes in regions of the brain affected by Parkinson’s disease and co-localises with lewy bodies. PloS One 17, e0262464 (2022).

Joshi, D., Srivastav, S. K., Belemkar, S. & Dixit, V. A. Zingiber officinale and 6-gingerol alleviate liver and kidney dysfunctions and oxidative stress induced by mercuric chloride in male rats: A protective approach. Biomed. Pharmacother Biomedecine Pharmacother. 91, 645–655 (2017).

Zalups, R. K. Molecular interactions with mercury in the kidney. Pharmacol. Rev. 52, 113–143 (2000).

Oliveira, V. A. et al. Mercury toxicity in pregnant and lactating rats: Zinc and N-acetylcysteine as alternative of prevention. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. Int. 27, 40563–40572 (2020).

Ernst, E., Møller-Madsen, B. & Danscher, G. Ultrastructural demonstration of mercury in Sertoli and Leydig cells of the rat following Methyl mercuric chloride or mercuric chloride treatment. Reprod. Toxicol. Elmsford N. 5, 205–209 (1991).

Boujbiha, M. A. et al. Testicular toxicity in mercuric chloride treated rats: Association with oxidative stress. Reprod. Toxicol. Elmsford N 28, 81–89 (2009).

Vachhrajani, K. D. & Chowdhury, A. R. Distribution of mercury and evaluation of testicular steroidogenesis in mercuric chloride and Methylmercury administered rats. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 28, 746–751 (1990).

Kandemir, F. M. et al. Protective effect of Rutin on mercuric chloride-induced reproductive damage in male rats. Andrologia 52, e13524 (2020).

Stadnicka, A. Localization of mercury in the rat ovary after oral administration of mercuric chloride. Acta Histochem. 67, 227–233 (1980).

Zhu, X., Kusaka, Y., Sato, K. & Zhang, Q. The endocrine disruptive effects of mercury. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 4, 174–183 (2000).

M, B. M., Mr, K. N. Z. T. & M, S. K. Toxic mechanisms of five heavy metals: Mercury, lead, chromium, cadmium, and arsenic. Front. Pharmacol. 12, (2021).

Ye, B. J. et al. Evaluation of mercury exposure level, clinical diagnosis and treatment for mercury intoxication. Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 28, 5 (2016).

Tan, T. M., Sin, Y. M. & Wong, K. P. Mercury-induced UDP-glucuronyltransferase (UDPGT) activity in mouse kidney. Toxicology 64, 81–87 (1990).

Ryan, D. M., Sin, Y. M. & Wong, M. K. Uptake, distribution and immunotoxicological effects of mercury in mice. Environ. Monit. Assess. 19, 507–517 (1991).

Yeoh, T. S., Lee, A. S. & Lee, H. S. Absorption of mercuric sulphide following oral administration in mice. Toxicology 41, 107–111 (1986).

Boyd, A. S. et al. Mercury exposure and cutaneous disease. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 43, 81–90 (2000).

Rowland, I. R. Interactions of the gut microflora and the host in toxicology. Toxicol. Pathol. 16, 147–153 (1988).

Handbook of Metallonutraceuticals. (CRC, Boca Raton, (2014). https://doi.org/10.1201/b16880

Meade, K. G. & O’Farrelly, C. β-Defensins: Farming the microbiome for homeostasis and health. Front. Immunol. 9, 3072 (2019).

Koeninger, L. et al. Human β-Defensin 2 mediated immune modulation as treatment for experimental colitis. Front. Immunol. 11, 93 (2020).

Gokarn, R. A., Rajput, D. S. & Patgiri, B. Pharmaceutical standardization of samaguna Bali Jarita Rasasindura prepared by conventional and modified method. Anc. Sci. Life 31, 123–128 (2012).

Yd, K. et al. B-cell translocation gene 2 regulates hepatic glucose homeostasis via induction of orphan nuclear receptor Nur77 in diabetic mouse model. Diabetes 63, (2014).

Mootha, V. K. et al. PGC-1α-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat. Genet. 34, 267–273 (2003).

Kersten, S. Integrated physiology and systems biology of PPARα. Mol. Metab. 3, 354–371 (2014).

Maliszewska, K. & Kretowski, A. Brown adipose tissue and its role in insulin and glucose homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 1530 (2021).

Lasar, D. et al. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma controls mature brown adipocyte inducibility through glycerol kinase. Cell. Rep. 22, 760–773 (2018).

Dileep, K., TripathiJ, S., Sanjay, G. A. & Comparative Clinical Evaluation of Sarpagandha Churna Yoga and Sattvavajaya Chikitsa (Ayu rvedic Psychotherapy) in the Management of Yoshaapasmara Vis-A-Vis Hysterical Neurosis. (2012). https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/A-Comparative-Clinical-Evaluation-of-Sarpagandha-in-Dileep-TripathiJ./358c96df633bc152d9480de9819a56d3905171e0

Finck, B. N. et al. Lipin 1 is an inducible amplifier of the hepatic PGC-1α/PPARα regulatory pathway. Cell. Metab. 4, 199–210 (2006).

Hammarstedt, A. et al. WISP2 regulates preadipocyte commitment and PPARγ activation by BMP4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 2563–2568 (2013).

Ying, J. et al. The stress-responsive gene GADD45G is a functional tumor suppressor, with its response to environmental stresses frequently disrupted epigenetically in multiple tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. Off J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 11, 6442–6449 (2005).

Wang, X. et al. Secretory clusterin mediates oxaliplatin resistance via the Gadd45a/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Cancer 9, 1403–1413 (2018).

Papa, S. et al. Gadd45beta promotes hepatocyte survival during liver regeneration in mice by modulating JNK signaling. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 1911–1923 (2008).

Do, N. et al. BMP4 is a novel paracrine inhibitor of liver regeneration. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 303, G1220–1227 (2012).

Zheng, H. et al. The dual-specificity phosphatase DUSP14 negatively regulates tumor necrosis factor- and interleukin-1-induced nuclear factor-κB activation by dephosphorylating the protein kinase TAK1. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 819–825 (2013).

Karunakar, K. K., Thanikachalam, P. V., Dhanalakshmi, S. M., Kesharwani, P. & Cheriyan, B. V. Hinokitiol attenuates gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity by reversing oxidative stress and inflammation. Pharmacol. Res. - Mod. Chin. Med. 10, 100410 (2024).

Lawan, A. et al. Deletion of the dual specific phosphatase-4 (DUSP-4) gene reveals an essential non-redundant role for MAP kinase phosphatase-2 (MKP-2) in proliferation and cell survival. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 12933–12943 (2011).

Jeong, D. et al. Cyr61 expression is associated with prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer 14, 164 (2014).

Boyd, S. C. et al. Oncogenic B-RAF(V600E) signaling induces the T-Box3 transcriptional repressor to repress E-cadherin and enhance melanoma cell invasion. J. Invest. Dermatol. 133, 1269–1277 (2013).

Xie, X. et al. OSGIN1 is a novel TUBB3 regulator that promotes tumor progression and gefitinib resistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 80, 272 (2023).

Beauchemin, D., Lacombe, C. & Van Themsche, C. PAX2 is activated by estradiol in breast cancer cells of the luminal subgroup selectively, to confer a low invasive phenotype. Mol. Cancer 10, 148 (2011).

Chu, F. F. et al. Bacteria-induced intestinal cancer in mice with disrupted Gpx1 and Gpx2 genes. Cancer Res. 64, 962–968 (2004).

Liu, K., Jin, M., Xiao, L., Liu, H. & Wei, S. Distinct prognostic values of mRNA expression of glutathione peroxidases in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 10, 2997–3005 (2018).

Nugteren, S. & Samsom, J. N. Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI) in mucosal tissues: Protects against inflammation, but promotes cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 59, 22–35 (2021).

Braga Emidio, N., Brierley, S. M., Schroeder, C. I., Muttenthaler, M. & Structure Function, and therapeutic potential of the trefoil factor family in the Gastrointestinal tract. ACS Pharmacol. Transl Sci. 3, 583–597 (2020).

Belle, N. M. et al. TFF3 interacts with LINGO2 to regulate EGFR activation for protection against colitis and Gastrointestinal helminths. Nat. Commun. 10, 4408 (2019).

Saiman, Y. & Friedman, S. L. The role of chemokines in acute liver injury. Front. Physiol. 3, 213 (2012).

Ahmad, S. et al. Catalytic characterization of human microsomal glutathione S-transferase 2: Identification of rate-limiting steps. Biochemistry 52, 1755–1764 (2013).

Simanshu, D. K. et al. Non-vesicular trafficking by a ceramide-1-phosphate transfer protein regulates eicosanoids. Nature 500, 463–467 (2013).