Abstract

The impact of COVID-19 vaccines on real-world transmission remains poorly understood and represents a key public health challenge. This study aimed to investigate natural, vaccine-induced immunity and the probability of experiencing SARS-CoV-2 infection in a cohort of families living in Rio de Janeiro. The participants were categorized into immune groups based on recent infection (within the past 9 months) and vaccination status, considering the type of vaccine received, the number of doses, and the strength of their immune response over time. We estimated the transmission probability within clusters using a multivariate model. From May 2020 to June 2023, we enrolled 669 individuals from 182 households; 272 clusters and 288 index cases were identified. Household transmission occurred in 124 (45.6%) clusters. During the pre-VoC period we did not find any factors associated with transmission. In the Gamma/Delta period, previous infections reduced the probability of transmission (OR = 0.088; 95%CI 0.023–0.341), while in the Omicron period, having a healthcare worker in the household (OR = 0.486; 95%CI 0.256–0.921) and hybrid immunity (OR = 0.095; 95%CI 0.010–0.924) decreased the probability of transmission. Our findings provide strong support for the protective effect of regular vaccination against household transmission in a cohort of families exposed to successive SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

COVID-19 vaccination strategies have primarily focused on mitigating severe illness, hospitalization, and mortality at the global scale, an objective which they have clearly achieved1,2. However, preventing infection has become another critical factor in controlling viral spread3,4. Household studies provide evidence that vaccination reduces susceptibility in contacts and infectiousness in infected individuals (index cases) across all age groups5,6,7,8. Variability characterizes COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness in household transmission, with significant differences observed across SARS-CoV-2 variants, contingent upon vaccine type and circulating strain. A meta-analysis of household studies, assessing complete vaccination without distinguishing vaccine types, estimated effectiveness at 78.6% for Alpha, 56.4% for Delta, and 18.1% for Omicron9. These studies highlight the need for further investigation regarding the waning effectiveness of vaccines over time and the evidence of breakthrough infections due to novel variants.

Nevertheless, these studies also highlight the need for further investigation regarding the waning effectiveness of vaccines over time and the evidence of breakthrough infections due to novel variants.

Brazil has reported the sixth highest absolute number of COVID-19 cases worldwide (37.5 million) with more than 2.9 million cases in the state of Rio de Janeiro alone as of March 2024, leading to an incidence rate of 16,000 cases per 100,000 individuals10,11. Since the beginning of the pandemic, many SARS-CoV-2 lineages have been identified in the country. The first to become predominant, was B.1.1.33 in March 2020, followed by the Zeta (P.2) variant in October 2020, Gamma (P.1) in January 2021, Delta (B.1.617.2/AY.*) in June 2021, and Omicron (BA.*) in December 202112.

Household transmission surveys offered a rapid and strategic approach to understanding key clinical, epidemiological, and virological features of the infection early in the pandemic. Despite households remaining significant transmission sites due to prolonged and repeated exposure among family members13,14, there is a critical gap in our understanding of this process during the dominance of Omicron lineages, which possess intrinsic properties that enhance transmission3,15,16,17,18.

In this study, families were followed by systematically collecting respiratory tract swabs for SARS-CoV-2 infection surveillance, and clinical data for monitoring symptoms and vaccine status from April 2020 to June 2023. This timeframe captured the period prior to the emergence of variants of concern (VoC), as well as the periods of circulation of the Gamma/Delta and Omicron lineages. Therefore, we aimed to investigate natural, vaccine-induced immunity and the probability of experiencing SARS-CoV-2 infection in a cohort of families living in Rio de Janeiro.

Results

As of June 2023, 708 individuals fulfilled the eligibility criteria and were invited to participate in the study. Of these, 669 individuals from 182 households were enrolled, resulting in an average of 3.7 individuals per household. Thirty-nine individuals declined to participate, with reasons ranging from discomfort during swab collection to unspecified reasons for refusal. Sociodemographic and immunological characteristics of the study participants, stratified by distinct epidemic periods defined by the circulation of SARS-CoV-2 variants were showed in Supplementary Table S1 online.

The majority (80%) of participants were adults. The distribution of ages across different epidemic periods remained consistent, as indicated by a similar interquartile range. The majority of participants were women (55%) and self-reported as white (56%). Over two-thirds (66.4%) of participants had attained a secondary school diploma or a college degree. Healthcare workers made up 13% of the study population.

During the pre-VoC period, 74% of participants reported at least two risk behaviors. In the following periods, this frequency was 79% in the Gamma/Delta and 60.8% in the Omicron periods.

Regarding the immunological status, during the pre-VOC period, none of the participants were vaccinated, nor had evidence of prior COVID-19 infection. In the Gamma/Delta period, 4.4% of participants had achieved vaccine-induced immunity (score 4–5: fully vaccinated and/or received booster dose), while a higher proportion (16%) had evidence of prior infection. Hybrid immunity (both vaccination and prior infection) was rare (0.5%) in this period. In Omicron period, vaccination rates increased substantially such that 83% of participants were fully vaccinated (score 4–5: fully vaccinated and/or received booster dose), prior infections were less frequent (3.3%), and the number of individuals with hybrid immunity increased slightly (3.3%).

Transmission occurred in 280 pairs (33.5%), distributed as follows: 119 transmissions during the pre-VoC period (42.5%), 31 during the Gamma/Delta period (11%), and 65 during the Omicron period (23.2%). Table 1 displays the number of household transmission pairs categorized by their immunological status.

During the pre-VoC period, all household transmissions involved unvaccinated individuals. In the Gamma/Delta period, the majority of transmissions occurred between unvaccinated individuals and those who lacked hybrid immunity.

In contrast, during the Omicron period, transmissions were observed even between vaccinated individuals, particularly those without hybrid immunity. Transmission occurred a median of four months after the contact had been vaccinated (interquartile range: 2–6 months). We investigated a total of 272 household clusters in which 288 index cases were identified. The number of clusters was less than the number of index cases because 14 clusters had more than one index case (co-primary cases). Household transmission occurred in 124 (45.6%) clusters.

Fully 49% of the household transmission events occurred during the pre-VoC period. Another 48% of household transmission took place in the Omicron period. With respect to the characteristics of the households, the average number of rooms per house was 6.5. Concerning household clusters, the size of the clusters was 3 to 4 individuals across the three periods. The percentage of households with children under 12 ranged from 34 to 43%, whereas the percentage of households with adults over 60 ranged from 35 to 39%.

Cluster household characteristics and transmission in the total population of the study are described in Table 2.

The average score of vaccine-induced immunity in households was higher in the Omicron period. Hybrid immunity was five times higher in households in the Omicron period when compared to the Gamma/Delta period.

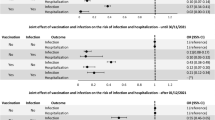

Table 3 details potential risk factors for household SARS-CoV-2 transmission across the epidemic periods (2020–2023). Vaccine-induced immunity was excluded from the pre-VoC and Gamma/Delta models due to low vaccination rates (0 and 4.4%). Conversely, the Omicron model incorporated hybrid immunity due to the high proportion of vaccinated participants (67%).

In the univariate model, the probability of an individual transmitting the virus within the household varied from 13.6 to 17.9%.

In the multivariate model, during the pre-VoC period none of the covariates was significantly associated with transmission. In the Gamma/Delta period, previous infections reduced the probability of transmission (OR = 0.088; 95%CI 0.023–0.341), while in the Omicron period the presence of a healthcare workers in households (OR = 0.486; 95%CI 0.256–0.921) and hybrid immunity (OR = 0.095; 95%CI 0.01–0.924) decreased the probability of transmission.

Discussion

Effective COVID-19 vaccination strategies require a clear understanding of how vaccination and prior infection influence the spread of new SARS-CoV-2 variants within households. Our study contributes to this understanding by demonstrating that hybrid immunity offered consistent protection against household transmission during the Omicron period.

This study builds upon previous research15,16 which demonstrated reduced transmission among close contacts with prior infection or hybrid immunity. While they provided valuable insights, these earlier studies had shorter follow-up periods and did not account for the time since vaccination or prior infection, which can influence the level of immune protection. A novel contribution of the present study is that we assessed the extent to which the time elapsed since vaccination or prior infection served as a predictor of immune protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection.

While it is well established that vaccination prevents severe illness, in this population vaccinated individuals remained susceptible to infection. In this cohort, the effectiveness of vaccines at preventing infection decreased significantly during the Omicron period. Studies suggest this attenuation may be attributable to the variant’s immune evasion capabilities3,15,16,17,18. Omicron exhibits substantial resistance to neutralization by sera from vaccinated and boosted individuals, with multiple mutations contributing to antibody evasion. Consequently, Omicron and its sublineages appear antigenically distinct from wild-type SARS-CoV-2, potentially threatening current vaccine efficacy to a similar extent.

This underscores the importance of conducting epidemiological surveillance of new SARS-CoV-2 variants. Such surveillance can provide decision-makers with valuable information to inform policies about adjusting vaccine formulations and updating the intervals between boosters.

In households during the Omicron period, the presence of healthcare workers was associated with reduced transmission compared to other periods. Several factors might explain this association. Firstly, healthcare workers were likely prioritized for vaccination, placing them at a lower risk of infection compared to the general population who received vaccinations later. Secondly, their profession may have made them more likely to seek testing upon experiencing even mild symptoms, potentially leading to earlier diagnoses and adoption of measures to reduce transmission.

In the present analysis, a high proportion of the participants (60.8–79%) reported engaging in behaviors believed to increase the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, we did not observe a significant association between such behaviors and transmission. Similarly, neither household density nor participant age were correlated with SARS-CoV-2 transmission. This contrasts with some prior investigations, which concluded that behaviors such as increased contact time between infected individuals and household members contribute to household transmission of SARS-CoV-219,20. Some of these results may reflect cultural differences. We can conjecture that in this population, there was less concern about social distancing from one’s own family members. Furthermore, individual behaviors such as masking at home and the duration of exposure to the index case in the household were not measured in our study.

As noted above, we carried out two analyses: a multivariate model of transmission risk within clusters and a pairwise transmission analysis. With respect to the latter, we found that infections primarily occurred between unvaccinated individuals during the Gamma/Delta period. Notably, there were no instances of transmission from unvaccinated cases to vaccinated contacts, suggesting that vaccination conferred protection against infection during the Gamma/Delta period. However, the Omicron period presented a shift, with most transmissions occurring between vaccinated individuals. Importantly, in our study, we did not observe transmission to contacts with hybrid immunity, which supports recent findings that prior infection offers a degree of protection against Omicron reinfection21. Moreover, the pairwise analysis was consistent with the multivariate results of cluster transmission.

Our study followed participants prospectively, meaning they were systematically monitored throughout the study period. In a previous study of this cohort, we found that retention rates, measured by the collection of at least one biological sample, ranged from 54% during the Gamma/Delta period to 68.2% during the Omicron period22. During the Delta/Gamma period, retention decreased mainly after the relaxation of social distancing measures and the vaccine rollout. However, with the emergence of the Omicron variant and the significant increase in COVID-19 cases, there was an increase in recruitment and recovery of participants with delayed follow-up.

This study had some limitations. Among them was the restricted sample size, which may have reduced our statistical power. Furthermore, since we recruited symptomatic participants, there were few asymptomatic individuals in the cohort and despite testing all contacts regardless of symptom presentation, the potential for asymptomatic infection suggests that some primary cases may have gone undiagnosed during the study. As such, we could not carry out a detailed assessment of asymptomatic transmissions. Moreover, in this cohort, although the infection induced immunity score was higher during Omicron than Gamma/Delta, the confidence intervals were overlapping. However, since Omicron had a higher transmissibility than Gamma, one might expect that the infection-induced immunity rate would have been significantly higher during Omicron. Perhaps the overlapping confidence intervals are attributable in part to differences in the detectability of cases during the two periods. According to epidemiological models, when a surveillance system has a low probability of detecting viral infections, the attack rate is likely to be underestimated23. According to a comprehensive review, the Omicron lineage had lower pathogenicity than Gamma variant24. We can conjecture that due to decreased pathogenicity we were less likely to detect Omicron infections, possibly contributing to an underestimate of the proportion of participants with prior infection during Omicron.

This study had several strengths. Firstly, our findings are robust because the results remained consistent when we performed a sensitivity analysis of the effect of months since vaccination and time since prior infection. Another strength of the study was the prospective design. This design allows for more precise conclusions about transmission and immunity because it minimizes recall bias, a common issue in retrospective studies that rely on existing data. Compared to registry-based studies, a prospective design actively follows participants over time, gathering data as events unfold. A further strength of the analysis is that the same methodology was applied consistently for telemonitoring and testing, which increased our confidence in the accuracy of diagnosis. Due to this high level of confidence, we were comfortable offering recommendations about case management including isolating cases. Moreover, the study benefited this population insofar as we encouraged the participants to be vaccinated and to follow measures to reduce transmission.

In conclusion, our findings provide strong support for the protective effect of regular vaccination against household transmission in a cohort of families in Rio de Janeiro exposed to successive SARS-CoV-2 variants. These results highlight the importance of effective global immunization strategies with updated vaccines to ensure timely vaccination to maximize protection, which remains a challenge to current vaccination policies.

Methods

Study design

This prospective study comprised an open cohort of individuals with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection and their household contacts from May 2020 to June 2023. The inclusion criteria encompassed individuals with SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by an RT-PCR test25,26 within ten days from symptom onset, referred to as the index case, and their household contacts.

Clinical and epidemiological data were collected in accordance with WHO protocol27. During the initial 42 days, follow-up occurred every 7 to 14 days with collections of clinical information, nasopharyngeal secretions, and blood samples. These shorter intervals in the acute phase allowed for observation of symptom persistence, the duration of positive PCR test results, and the timing of transmission. Subsequently, follow-up intervals were extended to every 90 days for 24 months, including collection of clinical data and blood samples for IgG level measurement. Moreover, additional sample collections or clinical appointments were scheduled whenever the participant reported persistence of symptoms (> 7 days), new onset of symptoms, or contact with a suspected/confirmed case of COVID-19.

Baseline data and follow-up assessments of signs and symptoms, hospitalizations, vaccination status, and health behavior were conducted through systematic telemonitoring via telephone calls by a trained team following the study schedule. Home visits were conducted for all participants to facilitate the collection of biological specimens, including blood, nasopharyngeal swabs, and saliva. During these visits, all household members were tested for SARS-CoV-2, regardless of symptoms. Home visits were also conducted per the study evaluation schedule to collect nasopharyngeal swabs stored in a viral transport medium (CDC, 2021b). The detailed follow-up procedures are described elsewhere22.

Study population and definitions

The index cases of COVID-19 were identified from patients attending the outpatient clinic of the Instituto Nacional de Infectologia Evandro Chagas, Fiocruz, Rio de Janeiro, a reference center for infectious diseases.

Household contacts were defined as individuals living within the same household, including domestic staff such as housekeepers, nannies, and caregivers. We defined secondary cases as household contacts who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR. Household density was determined by dividing the total number of residents by the number of rooms. Each enclosed area of the house, defined by a roof and walls, including spaces like bathrooms and kitchens solely used by the household’s residents, counted as a room28.

Vaccination against COVID-19 began in January 2021 in Brazil, and it was first made available to priority groups such as healthcare workers, the elderly, and individuals with chronic illnesses29. The Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (Anvisa) has approved vaccines including CoronaVac (Butantan/Sinovac Biotech), ChAdOx1-S/nCoV-19 (Oxford/Biomanguinhos), Ad26.COV2.S (Janssen), and BNT162b2 (Pfizer/BioNTech). In addition, since February 2023, a bivalent formulation of BNT162b2 with the ancestral and Omicron BA.4/5 lineages has been freely available in the public healthcare system.

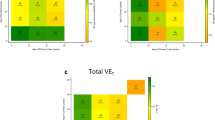

In the present study, the participants were categorized based on their immune status according to two factors: (i) vaccination status that was determined by a vaccine-induced immunity score, described in Table 4, and (ii) prior infection status that was categorized as: (0) no prior infection; (1) infected at least 9 months ago; and (2) infected less than 9 months ago.

We classified participants as having hybrid immunity, defined as combined immunity from both, vaccination, and prior infection, if they had a vaccine-induced immunity score between 4 and 5 and an infection-induced immunity score of 2.

The vaccine-induced immunity score was based on evidence from literature3,5 which indicates that the duration and intensity of the humoral anti-Spike response decrease over time depending on the vaccine platform and the number of doses.

To investigate behaviors that influence the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission within households, we developed a risk behavior score based on key factors identified in reviews and prospective studies about household transmission20,30.

Each participant received a score from one to four. Each of the following activities earned one point: (i) sharing a bedroom, (ii) bathroom, (iii) sharing utensils, or (iv) failing to self-isolate (for example, continuing routine daily activities in the home such as watching TV with others in the living room or having meals together).

Data collection

Using telemonitoring, we collected information on the participants’ sociodemographic traits, health conditions (comorbidities, signs, and symptoms), health behaviors (self-isolation and contact with positive cases), and vaccination status as well as characteristics of the household (size and number of rooms).

The aforementioned information was stored in a Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)31,32 database. A comprehensive dataset encompassing 602 variables was assembled that included sociodemographic data, behavioral patterns, clinical information, immunization records, and laboratory data.

For the management and querying of this database, MySQL Workbench 8.0 was employed. To ensure data quality, regular weekly data quality control checks were conducted. Data security was maintained by securely sharing it through the ownCloud platform, which is equipped with a RNP ICPEdu OV SSL CA 2019 security certificate.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out in two phases. First, we identified the index cases for each household and period according to the date of onset of symptoms or the date of the first positive RT-PCR test for SARS-CoV-2. Second, we identified all contacts tested within five weeks after the onset of symptoms of the index case. This timeframe was chosen based on both our study design and the estimated window for transmission among household contacts.

Whenever there was at least one contact in the same household as the index case, we designated the group of affected individuals as a “cluster”. If one of the contacts tested positive by PCR, then this household was classified as having potentially experienced household transmission. Notably, a single household could experience one or more cluster transmissions during distinct epidemic periods or during the circulation of a given variant.

Three epidemic periods were considered for statistical analysis: the pre-VoC period during which the Zeta variant circulated in addition to the original strain (May 2020 - January 2021), the Delta/Gamma VoC (February 2021 – November 2021), and the Omicron VoC (December 2021 – June 2023).

In the statistical analysis, the outcome of interest was the occurrence of transmission within a cluster. To investigate the probability of this outcome, we modeled the number of infected contacts within a cluster as a random variable from the binomial distribution. The binomial random variable was defined by two parameters: the number of individuals in the cluster and the probability of transmission within the cluster. In turn, the probability of transmission within the cluster was defined by a logit link function that consisted of an intercept, fixed effects, and random effects leading to a binomial generalized linear mixed model. Since a household could have more than one cluster, household random effects were included to induce the household dependence and to represent a variability at the scale of the cluster that could not be explained by the fixed effects. The average household transmission probability was estimated using an intercept-only Binomial random effects model. The fixed effects were variables that have been hypothesized to influence household transmission according to the literature33. In the present analysis, the fixed effects were household density, the number of children under 12 or adults 60 or older in the household, and categorical variable representing whether any member of the household was a healthcare worker. The parameters of the model were estimated via Bayesian inference using a nested Laplace approximation34. We report the median parameter estimate and the 95% credible interval.

The vaccine-induced immunity score was not analyzed in any model because during the pre-VoC and Gamma/Delta periods, very few individuals were vaccinated. Therefore, we investigated immunological status using the variable prior infections. On the other hand, during the Omicron period, a high proportion of the participants were vaccinated. In light of this, we analyzed immunological status using the variable hybrid immunity. To account for waning immunity, we conducted additional analyses considering a timeframe of up to six months after exposure to vaccination or infection (see Supplementary Tables S2 to S4 online).

In addition to analyzing the overall probability of transmission within the household, we also conducted a finer scale analysis of transmission between pairs of individuals. Each such pair, in which an index case transmitted the virus to a secondary case within the same household cluster, was referred to as a “transmission pair”. To determine how long after vaccination transmission occurred, we identified the date of vaccination of each contact infected by an index case. Next, we calculated the number of months between the transmission event and the vaccination of the contact. We performed this calculation for all infected contacts and report the median number of months between vaccination and transmission and interquartile range.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study will be available on reasonable request from corresponding author.

References

Tenforde, M. W. et al. Sustained effectiveness of Pfizer-BioNTech and moderna vaccines against COVID-19 associated hospitalizations among Adults — United States, March–July 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 70, 1156–1162 (2021).

Steele, M. K. et al. Estimated number of COVID-19 infections, hospitalizations, and deaths prevented among vaccinated persons in the US, December 2020 to September 2021. JAMA Netw. Open. 5, e2220385 (2022).

Espíndola, O. M. et al. Reduced ability to neutralize the Omicron variant among adults after infection and complete vaccination with BNT162b2, ChAdOx1, or coronavac and heterologous boosting. Sci. Rep. 13, 7437 (2023).

Wang, L., Møhlenberg, M., Wang, P. & Zhou, H. Immune evasion of neutralizing antibodies by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 70, 13–25 (2023).

Prunas, O. et al. Vaccination with BNT162b2 reduces transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to household contacts in Israel. Science 375, 1151–1154 (2022).

Martínez-Baz, I. et al. Effect of COVID-19 vaccination on the SARS-CoV-2 transmission among social and household close contacts: A cohort study. J. Infect. Public. Health. 16, 410–417 (2023).

Clifford, S. et al. Effectiveness of BNT162b2 and ChAdOx1 against SARS- CoV-2 household transmission: a prospective cohort study in England [version 2; peer review: 2 approved]. Wellcome Open. Res. (2023).

Muhsen, K. et al. Association between COVID-19 vaccination and SARS-CoV-2 infection among household contacts of infected individuals: A prospective household study in England. Vaccines 12, 113 (2024).

Madewell, Z. J., Yang, Y., Longini, I. M., Halloran, M. E. & Dean, N. E. Household secondary attack rates of SARS-CoV-2 by variant and vaccination status: an updated systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open. 5, e229317 (2022).

Ministério da Saúde. Painel Coronavírus (2023). https://covid.saude.gov.br/

World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. World Health Organization (2023). https://www.who.int/

Fundação Oswaldo Cruz. Dashboard Rede genômica. Vigilância genômica.do SARS-CoV‐2 no Brasil. Dados Gerados Pela Rede genômica Fiocruz E/ou depositados Na Plataforma Gisaid Por outras instituições a partir de Amostras Brasileiras. Rede Genômica Fiocruz (2023). https://www.genomahcov.fiocruz.br/dashboard-pt/

Leclerc, Q. J. et al. What settings have been linked to SARS-CoV-2 transmission clusters? Wellcome Open. Res. 5, 83 (2020).

Wong, N. S., Lee, S. S., Kwan, T. H. & Yeoh, E. K. Settings of virus exposure and their implications in the propagation of transmission networks in a COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Reg. Health - West. Pac. 4, 100052 (2020).

Lind, M. L. et al. Evidence of leaky protection following COVID-19 vaccination and SARS-CoV-2 infection in an incarcerated population. Nat. Commun. 14, 5055 (2023).

Tan, S. T. et al. Infectiousness of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections and reinfections during the Omicron wave. Nat. Med. 29, 358–365 (2023).

Iketani, S. et al. Antibody evasion properties of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron sublineages. Nature 604, 553–556 (2022).

Wang, Q. et al. Antibody evasion by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants BA.2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5. Nature 608, 603–608 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Risk factors associated with indoor transmission during home quarantine of COVID-19 patients. Front. Public. Health. 11, 1170085 (2023).

Namageyo-Funa, A. et al. Behaviors associated with household transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in California and Colorado, January 2021–April 2021. AJPM Focus. 1, 100004 (2022).

Arabi, M. et al. Role of previous infection with SARS-CoV-2 in protecting against Omicron reinfections and severe complications of COVID-19 compared to pre-omicron variants: a systematic review. BMC Infect. Dis. 23, 432 (2023).

Da Silva, M. F. B. et al. Cohort profile: follow-up of a household cohort throughout five epidemic waves of SARS-CoV-2 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Cad. Saúde Pública (2024). (in press).

Blumberg, S. & Lloyd-Smith, J. O. Inference of R(0) and transmission heterogeneity from the size distribution of stuttering chains. PLoS Comput. Biol. 9, e1002993 (2013).

Jacobs, J. L., Haidar, G. & Mellors, J. W. COVID-19: challenges of viral variants. Annu. Rev. Med. 74, 31–53 (2023).

de Instituto Tecnologia em Imunobiológicos—Bio-Manguinhos, FIOCRUZ. KIT MOLECULAR SARS-CoV2 (E)—Bio-Manguinhos. Rio de janeiro. (2020).

Corman, V. M. et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Eurosurveillance 25, (2020).

World Health Organization. Household transmission investigation protocol for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), 23 March 2020. (2020).

Principles and Recommendations for Population and Housing Censuses: 2020 Round. (United Nations, New York, (2017).

Brasil NOTA TÉCNICA No 467/2021-CGPNI/DEIDT/SVS/MS. (2021).

Musa, S. et al. Household transmission of SARS-CoV-2: a prospective observational study in Bosnia and Herzegovina, August–December 2020. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 112, 352–361 (2021).

Harris, P. A. et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J. Biomed. Inf. 95, 103208 (2019).

Harris, P. A. et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inf. 42, 377–381 (2009).

Gelmanew, A. & HillJennifer, J. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Rue, H., Martino, S. & Chopin, N. Approximate bayesian inference for latent Gaussian models by using integrated nested Laplace approximations. J. R Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 71, 319–392 (2009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MFBS, PB, LG, LSB, MSC conceived and designed the analyses. MFBS, APC, HFPS, ICVM, SLSP collected the data. LSB, HFPS performed the statistical analyses. MMS, PCR conducted the laboratory analyses. MFBS, LSB, HFPS, PB, LG, TLF, OMS wrote the paper. All the authors have reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The Brazilian National Research Ethics Committee (CONEP) approved the study under the number 30639420.0.0000.5262, and all participants provided written informed consent. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

da Silva, M.F.B., Guaraldo, L., Bastos, L.S. et al. Natural, vaccine-induced immunity and the probability of experiencing SARS-CoV-2 infection in a household cohort in Rio de Janeiro. Sci Rep 15, 17211 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97289-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97289-5