Abstract

In engineering practice, analytical solutions for the bending problem of functionally graded plates are usually available only when the boundary conditions are simple. When using numerical methods like the variational method to solve the problem, trial functions can generally be constructed only for simple-shaped boundaries. In contrast, the R-function method can be effectively used to address problems with complex boundary shapes. This study integrates the R-function theory with the variational method to investigate the bending problem of functionally graded plates with complex boundaries. By employing the R-function theory, complex regions can be represented as implicit functions, which facilitates the construction of trial functions that satisfy complex boundary conditions. The paper elaborates on the variational principle and R-function theory, derives the variational equation for the bending problem of functionally graded plates, and validates the feasibility and accuracy of the method through numerical examples of rectangular, U-shaped, and L-shaped functionally graded plates. The results are compared with those from other literature and the finite element method (FEM) using ANSYS, showing good agreement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Functionally Graded Materials (FGMs) achieve a smooth variation in properties through the spatial distribution control of their components. They can be classified into metal/ceramic and ceramic/ceramic types. By means of microstructure control, FGMs optimize mechanical, thermal and other properties. Due to the continuous variation of their properties, FGMs perform excellently in fields such as aerospace, biomedical engineering and nuclear industry. As a specific application, functionally graded plates are widely used in aerospace, civil and mechanical engineering. Functionally graded plates, as a special kind of linearly elastic plates, are special in that material parameters (such as Young’s modulus) change in a gradient manner in the thickness direction. In view of this, many solution theories applicable to linearly elastic plates can also be applied to functionally graded plates under the condition that certain adaptability adjustments are met1,2,3,4,5,6.

Functionally graded plates, when applied in engineering, typically need to withstand transverse loads, hence many scholars have conducted research on their static mechanical properties7,8.Currently, the methods for solving such problems mainly fall into two categories: numerical methods and analytical methods. These two types of methods are respectively based on specific shear deformation theories, the finite element method, and other specific theories. In various analytical methods, the deflection function needs to be selected in advance, and the selection of these functions has a certain degree of arbitrariness and there is no definite rule to follow. In relevant studies, Tan-Van Vu and other scholars proposed a simple meshfree method based on the first-order shear deformation theory for the analysis of functionally graded plates 9. In another study, a new effective meshfree method based on the refined third-order shear deformation theory was demonstrated, which was used for the analysis of through-thickness functionally graded plates10. There were also studies that applied the enhanced meshfree method with the refined inverse sine shear deformation plate theory and new correlation functions to conduct in-depth investigations on functionally graded plates 11. The refined hyperbolic sine shear deformation theory for sandwich functionally graded plates was constructed through the enhanced meshfree method with new correlation functions 12. A meshfree analysis of functionally graded plates was carried out by utilizing a novel four-unknown arctangent exponential shear deformation theory 13. Based on the refined quasi-three-dimensional logarithmic shear deformation theory, an effective meshfree method for the analysis of functionally graded plates resting on elastic foundations was developed14. The effective meshfree method based on the simple quasi-three-dimensional hyperbolic shear deformation theory was adopted to analyze the mechanical behaviors of functionally graded porous plates resting on elastic foundations15. The buckling of porous sandwich functionally graded plates resting on Pasternak foundations was explored by combining the new refined quasi-three-dimensional hyperbolic shear deformation theory with the Navier solution 16. Researchers analyzed the deflection and natural frequency of functionally graded porous plates embedded in elastic foundations by applying the four-variable hyperbolic quasi-three-dimensional theory17. Researchers studied the natural frequency of functionally graded porous plates supported by Kerr-type foundations by means of the innovative trigonometric shear deformation theory 18.Researchers analyzed the deflection, stress and buckling of porous functionally graded material plates on Kerr-type elastic foundations by adopting a new five-unknown trigonometric shear deformation theory19. The free vibration of functionally graded porous plates with auxetic honeycomb core laid on Kerr-type elastic foundations was analyzed20.

In relevant studies, Liew KM applied the element-free kp-Ritz method to conduct the thermoelastic analysis and free vibration analysis of functionally graded plates respectively. As a numerical method, this approach avoids the limitations of traditional finite element meshing by means of special algorithms and can effectively deal with the complex characteristics and mechanical behaviors of functionally graded plates21,22.Nguyen-Xuan and others adopted the edge smoothed finite element method and the node smoothed finite element method to study functionally graded plates. Both of these are improved forms of the finite element method. They improve the computational accuracy and efficiency by smoothing the strain so as to better cope with the changes in material properties23,24. Loc V. Tran, A.J.M. Ferreira and H. Nguyen-Xuan utilized the isogeometric analysis (IGA) based on the higher-order shear deformation theory to study functionally graded plates. It combines the advantages of computer-aided design and numerical analysis and provides a new approach for the analysis of functionally graded plates25. The bending analysis of FGM plates is a critical aspect of understanding their structural behavior under different loading conditions. A modified Radial Point Interpolation Method (RPIM) based on Higher-Order Shear Deformation Plate Theory was developed for accurately analyzing the nonlinear bending of FGM plates26. Nguyen, Niiranen and other researchers developed a nonlocal continuum damage model for functionally graded plates by applying third—order shear deformation theory and isogeometric analysis (IGA). This model regulates the softening behavior through a nonlocal equivalent strain field. Moreover, it utilizes NURBS basis functions for modeling and approximation, which enables it to effectively capture localized damage27. The Ritz method28, employed for obtaining an approximate solution for FGM beams, assumes a form for the displacements of the plate, specifically when dealing with symmetric problems that have simply supported edges. It also posits that temperature variations are uniform and change only in the direction of thickness.The improved Rayleigh–Ritz method29 is used to study the free vibration characteristics of functionally graded plates of arbitrary shape. It assumes that the material varies exponentially in the thickness direction and employs Mindlin plate theory combined with an improved Fourier series as the displacement admissible function.

J.Ying has provided exact solutions for FGM beams on elastic foundations, which account for exponential variations in material properties and are applicable to cases with arbitrary material property changes through thickness30. Sahraee.S used Levinson Plate Theory (LPT) for the bending analysis of functionally graded sectorial plates, taking into account transverse shear strains and providing closed-form solutions that have been verified with existing literature data31. Sinusoidal Shear Deformation Theory is a new high-order shear deformation model for static analysis of functionally graded plates. It accounts for quadratic transverse shear strain variation and satisfies zero traction boundary conditions without shear correction factors32.The Analytical Solution for Nonlinear Cylindrical Bending provides a closed-form solution for the nonlinear bending and free vibration of functionally graded microplates, including couple stress effects33. In the theory of Three-Dimensional Elasticity, the analytical solutions using 3D elasticity equations are generally confined to FGM plates with exponential or simple material gradients, providing insights into their mechanical behavior under combined loads34. Yang considers different shear deformation theories to investigate the bending, shear stress, and normal stress distribution in simply supported FGM beams under various shear deformation theories and compares the static bending behaviors of FGM and homogeneous material beams35. Bending analysis with shear deformation theories examines bending, shear stress, and normal stress in simply supported FGM beams using different shear deformation theories and compares their static behavior with homogeneous beams36. In a study conducted in 2006, a static response analysis based on the Generalized Shear Deformation Theory was proposed, which simplifies the enforcement of traction-free boundary conditions without the need for shear correction factors and whose material properties vary according to a simple power-law distribution graded based on the volume fraction.37. A study has provided a closed-form solution for the bending analysis of five-curvature functionally graded sandwich panels in a magnetic field, which involves complex laminated structures and interactions between different material layers38. Research on nonlinear mechanical behavior in the study of functionally graded plates39 has focused on their nonlinear vibration and dynamic response by taking into account the material’s nonlinear properties, offering crucial insights into their performance under extreme conditions. A comparison with radial basis function results demonstrates its efficacy40. Aribas U. N and colleagues studied the limitations of the first-order shear deformation theory for functionally graded plates when cross-sectional warping is significant41.

The existing research results on functionally graded plates present a multi-dimensional situation in terms of bending and shape description. On the one hand, the meshless method based on different shear deformation theories can accurately take into account the complex changes of materials. Improved numerical methods, such as the edge smoothed finite element method, can enhance the calculation accuracy to capture the relationship between geometry and mechanics. Some analytical solutions can deeply analyze the mechanical behaviors under specific material gradients and have been verified to be reliable. On the other hand, the high-order shear deformation theory is complicated in calculation and consumes a large amount of resources.

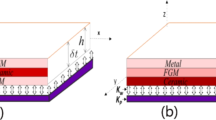

In view of this, this study conducts an in-depth exploration on the bending problem of functionally graded plates. Given the characteristics of Young’s modulus of the functionally graded plates in this study, which allow the adoption of the analysis methods for traditional plates, the first-order shear deformation theory is selected. It has a low computational complexity and is easy to apply, and can effectively simplify the solution process. Meanwhile, the R-function theory is introduced. By constructing equations with its implicit function form, it can accurately formulate the boundary conditions of plates with complex shapes. It can conveniently describe general complex shapes with features such as missing corners, convexities and concavities, and asymmetries, and is superior in terms of the flexibility of shape description, providing a new approach for the analysis of functionally graded plates. Therefore, it is of great practical significance to study the bending behaviors of functionally graded plates with irregular or complex shapes42,43,44,45,46.

Reissner47 and Mindlin48 proposed the first-order shear deformation theory, which introduced the concept of transverse shear deformation into the analysis of plate structures. The theory assumes that although straight lines in the thickness direction of the plate remain straight after deformation, they are no longer perpendicular to the physical midsurface of the plate. Subsequently, Timoshenko49 further proposed a shear correction factor that takes into account the effect of Poisson’s ratio to improve the accuracy of the theory. Based on this, Huffington proposed to divide the transverse displacement into bending and shear components. Thai et al. applied this method to solve many plate problems 50,51, and further developed the Modified First-Order Shear Deformation Theory (MFSDT). They improved the original theory and described the deformation behavior of plates under load more accurately.

The Ritz method52,53,54 is a widely used energy method in mechanical research, favored for its simplicity in the solution process. The R-function theory can describe complex regions in the form of implicit functions, representing the problem boundaries through normalized equations \(\omega { = }0\) and defining the region itself through inequalities \(\omega > 0\)55,56,57. By introducing the R-function theory55,58,59,60, it is convenient to construct the deflection functions \(\omega\) for functionally graded plates with irregular concave-convex shapes, ensuring that these functions meet the boundary conditions. Subsequently, the variational method is used to solve the deflection functions of these irregularly shaped functionally graded plates.

After elucidating the fundamental theories, this paper provides detailed numerical analysis cases for functionally graded plates with rectangular, L-shaped, and U-shaped sections. The variational formulas are solved using MATLAB software, and the results obtained are compared with the data from finite element analysis to verify the reliability of the methods presented in this paper.

Material properties

The research subject of this section is a functionally graded plate with a constant thickness of h. The functionally graded plate is composed of a composite of ceramic and steel, with the upper surface being ceramic and the lower surface being steel. Its elastic modulus \(E(z)\) conforms to a power law function. Therefore, the elastic modulus of the functionally graded plate is represented as the plate’s elastic parameters (including the elastic modulus and density) varying according to a law distribution with thickness, and its value is

The graded index is represented by \(k(k \ge 0)\), with the subscripts "c" and "s" denoting ceramic and steel, respectively.

The variational method for calculating the bending problem of functionally graded plates

The Modified First-Order Shear Deformation Theory (MFSDT) proposed by Thai and others is an extension of the classical first-order shear deformation theory. In the Modified First-Order Shear Deformation Theory, the transverse displacement \(w\) is divided into bending and shear components (denoted as \(w = w_{b} + w_{{\text{s}}}\) ), and it is assumed that \(\varphi_{x} = - w_{b,x}\),\(\varphi_{x} = - w_{b,x}\). (where "\(,x\)" and "\(,y\)" represent the partial derivatives with respect to the shear components \(x\) and \(y\) , respectively), leading to the following displacement field

From the above equations, we obtain

When considering the first-order shear deformation theory, the linear constitutive equations for the functionally graded plate are

Among \(\sigma = \left\{ {\sigma_{x} ,\sigma_{y} ,\tau_{yz} ,\tau_{xz} ,\tau_{xy} } \right\}^{T}\) and \(\varepsilon = \left\{ {\varepsilon_{x} ,\varepsilon_{y} ,\gamma_{yz} ,\gamma_{xz} ,\gamma_{xy} } \right\}^{T}\) are the stress and strain vectors. The stiffness coefficient \(Q_{ij}\) is expressed as

When the research object is a thick plate, let \(Q_{44} = Q_{55} = K\frac{E(z)}{{2(1 + \mu )}}\). Where \(K = \frac{5}{6}\).

In the Cartesian coordinate system \(oxyz\), the total potential energy of the elastic body is

Given that the first-order shear deformation theory is a two-dimensional shear deformation theory, when considering the two-dimensional shear deformation theory, \(\varepsilon_{z} { = }0\), that is to say

For the calculation of strain energy in functionally graded plates, the thickness direction needs to be discretized. First, the thickness range of the plate \(\left[ { - h/2,h/2} \right]\) is discretized into multiple small thickness intervals. The thickness is discretized into n small intervals, with each interval’s thickness increment being \(\Delta z = h/n\). Define the discrete points in thickness as \(z_{i} = - h/2 + i \times \Delta z\), where i = 0, 1, 2,…, n. Next, calculate the strain energy contribution of each thickness interval. For each thickness interval \(\left[ {z_{i} ,z_{i + 1} } \right]\), calculate the \(E(z)\) value at the midpoint \(z_{mid} = \left( {z_{i} + z_{i + 1} } \right)/2\) of that interval, using the formula for the elastic modulus \(E(z) = \left( {E_{c} - E_{s} } \right)\left( {z/h + 1/2} \right)^{k} + E_{s}\), which varies with thickness according to the given formula \(E(z)\).

At this thickness, calculate the strain energy contribution within the plate plane corresponding to this thickness interval

Within this thickness interval, it can be approximated as, where \(dz\) is approximated as \(\Delta z\) within this interval. The total strain energy is obtained by summation

Summing up the strain energy contributions from all thickness intervals yields the approximate total strain energy

Substituting Eq. (4) into Eq. (19) yields

Now set the expressions for \(u\),\(v\),\(w\) as

Among them, \(w_{m} = w_{bm} + w_{sm}\).

When the subject of study is a functionally graded thin plate without considering the stretching effect of the thickness and only considering the bending term in the transverse displacement, it is assumed that \(w_{m} = w_{bm}\).

The \(C_{m}\) are m independent undetermined coefficients; \(w_{m}\) is the prescribed function that satisfies the plate displacement boundary conditions. In this way, regardless of the values taken by \(C_{m}\), the deflection \(w\) shown in the formula above can always meet the displacement boundary conditions. Note that the variation of the deflection \(w\) is achieved only by the variation of the coefficients \(C_{m}\); as for the prescribed function \(w_{m}\), it varies only with the coordinates and is completely unrelated to the above variation.

To determine the coefficients \(C_{m}\), the following formula must be applied

In the bending problem of a thin plate, both body forces and surface forces are attributed to the load q.

Based on this, you can derive m linear equations for \(C_{m}\) to determine \(C_{m}\), and thus obtain the deflection \(w\) from Eq. (23), which allows for the calculation of the plate’s internal forces.

According to the principle of minimum potential energy, the condition for the total potential energy to be at an extremum is

where m = 1,2,3,…

The equation can also be written as

where

The theory of R-functions

Based on the R-function theory, describing a complex region \(\omega_{0}\) involves using Boolean operations \(\vee_{\alpha }\) and \(\wedge_{\alpha }\) to represent the union and intersection of its subdomains. If the function \(\omega_{l}\) that describes each subdomain satisfies a first-order normalization equation, then \(\omega_{0}\) will also satisfy a first-order normalization equation.

The definition of a first-order normalization equation is.

Assuming that X and Y satisfy the definition of a first-order normalization equation, then the following Boolean operations \(X \vee_{\alpha } Y\) and \(X \wedge_{\alpha } Y\) also constitute a first-order normalization equation

where \(- 1 \le \alpha \le 1\).

Derivation of the variational equation

The expression for deflection is taken as

In the bending problem, the R-function is incorporated into Eq. (23). In this paper, the case of a clamped edge is discussed. For a clamped edge, the deflection is zero and the rotation angle is also zero. By referring to the properties of the R-function, the obtained \(\omega_{0}\) is squared to meet the boundary conditions of the fixed support edges. Thereby, the boundary conditions are represented within \(\omega_{0}\).

In the bending problem, the R-function is incorporated into Eq. (23). This paper discusses the case of clamped edges, and by referring to the properties of the R-function, the obtained \(\omega_{0}\) is squared to meet the boundary conditions of the clamped.

Substituting Eq. (32) into Eq. (23) yields

Further, taking the derivative with respect to \(C_{i}\) for i = 1,2,3,…,m-1,m, we obtain

Substituting Eqs. (33)–(42) into Eq. (27) and simplifying, we get

For details on \(\sigma_{1} \sim \sigma_{14} { }\), please refer to Appendix 1.

After derivation, the coefficient equation set can be obtained.

where \(A = \left( {a_{ij} } \right)_{m \times m}\)

For details on \(\sigma_{1} \sim \sigma_{14} { }\), please refer to Appendix 1.

Among them, i = 1, 2,…, m; and j = 1, 2,…, n. \(\Omega\) represents the region contained by the cross-section (x–y) in the Cartesian coordinate system, from which \(C_{m}\) can be obtained according to Eq. (17). Substituting into the deflection expression (32), the deflection expression is obtained.

Numerical Example.

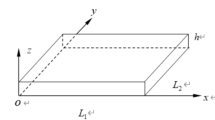

Example 1 rectangular functionally graded plate

A rectangular functionally graded plate with side lengths of \(2a\) and \(2b\), where a = b = 0.5, Poisson’s ratio is 0.3, the plate thickness \(h\) is 0.05 m, and the uniformly distributed load \(q\) of \(10^{6} pa\), as shown in Figs. 1 and 2. The upper surface of the rectangular functionally graded plate is ceramic, and the lower surface is steel. Its elastic modulus conforms to a power law function, so the elastic modulus \(E(z)\) of the functionally graded plate is expressed as the elastic parameters (including the elastic modulus and density) of the plate varying according to a law distribution with thickness, and its value is

The elastic modulus of ceramic, denoted as \(E_{c}\), is taken as 210 GPa, and that of steel, denoted as \(E_{s}\), is taken as 390 GPa. Once the constituent materials of the functionally graded material are determined, the plate’s elastic modulus depends on the graded index. As the graded index increases, the proportion of ceramic in the material of the plate gradually decreases while the proportion of steel gradually increases. When the graded index increases to infinity, the material of the plate converges to a pure steel plate, and thus the maximum deflection also converges to the maximum deflection of the steel plate.

In this example, we take k = 0, k = 1, k = 10 and k = + ∞ respectively.

For different values of \(k\), substitute \(k\) into Eq. (13) to obtain \(E(z) = E_{c}\). Let n = 20 and discretize the thickness range \(\left[ { - h/2,h/2} \right]\) into many small thickness intervals.Discretize the thickness into n small intervals, with each interval’s thickness increment being \(\Delta z = h/n\). Define the discrete thickness points as \(z_{i} = - h/2 + i \times \Delta z\),where \(i = 0,1,2,...,n\). Calculate the strain energy contribution of each thickness interval. For each thickness interval \(\left[ {z_{i} ,z_{i + 1} } \right]\), calculate the value of \(E(z)\) at the midpoint \(z_{mid} = \left( {z_{i} + z_{i + 1} } \right)/2\).

Substituting into Eq. (43) will yield the coefficient equation set for calculating the results.

According to the R-function theory, simply take

where \(\omega_{1} = \frac{{a^{2} - x^{2} }}{2a} \ge 0\) and \(\omega_{2} = \frac{{b^{2} - y^{2} }}{2b} \ge 0\).

Substituting into Eq. (31) and taking \(\alpha { = }0\), we get

When the research object is a functionally graded thin plate, without considering the thickness stretching effect and only considering the bending term in the transverse displacement, it is assumed, so take \(w_{m} = w_{bm} ,w_{s} = 0\). The shape of the plate here is a symmetrical figure. The function of the deflection w should be set as an even function of x and y, therefore \(w_{m}\) is taken as 1, \(x^{2}\), \(y^{2}\), \(x^{4}\), \(y^{4}\), \(x^{2} y^{2}\), \(x^{6}\), \(y^{6}\), \(x^{2} y^{4}\) and \(x^{4} y^{2}\)。

In finite element modeling, select the static structural analysis module. During meshing, set the side length of each element of the plate to be 0.028 m. The rectangular thin plate is divided into 1,225square meshes in total.The combination of R-functions with trial functions in the variational method may lead to a situation where the denominator of the integrand becomes zero at the boundaries of the integral during the integration process. In such cases, it is impossible to calculate the integral of the integrand. Therefore, a mesh division method is used here, dividing the rectangular area into \(N \times N\) grids.

When \(k = 0\), the number of trial functions m = 10, and the grid numbers are taken as \(15 \times 15\),\(20 \times 20\),\(25 \times 25\),\(30 \times 30\),\(35 \times 35\),\(40 \times 40\) respectively, the deflection results of the plate’s center point are listed in Table 1.When the grid size is set to \(40 \times 40\) and m takes different values, the results are listed in Table 2. When \(k = + \infty\), with the number of trial functions m = 10, and the grid numbers are taken as \(15 \times 15\),\(20 \times 20\),\(25 \times 25\), \(30 \times 30\),\(35 \times 35\),\(40 \times 40\) respectively, the deflection results of the plate’s center point are listed in Table 3.

When the grid size is set to \(40 \times 40\) and m takes different values, the results are listed in Table 2. When \(k = + \infty\), with the number of trial functions m = 10, and the grid sizes are taken as \(15 \times 15\),\(20 \times 20\),\(25 \times 25\),\(30 \times 30\),\(35 \times 35\),\(40 \times 40\) respectively, the deflection results of the plate’s center point are listed in Table 3.When the grid size is set to 40 × 40 and m takes different values, the results are listed in Table 4. From Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4, it can be seen that the deflections of functionally graded plates calculated by the method in this paper are effective and are in good agreement with the analytical solutions61 and finite element solutions. This proves the feasibility and correctness of the method presented in this paper.When k = 0, with a grid size of 40 × 40 and m taking different values, the deflection curve of the functionally graded plate’s center point at y = 0 is shown in Fig. 3; when \(k = + \infty\), with the same grid size and m taking different values (Fig. 4), the deflection curve at y = 0 is shown in Fig. 5. When k = 0 and m = 10, the comparison between ANSYS finite element results and the method presented in this paper is shown in Fig. 4; when k = + ∞ and m = 10, the comparison between ANSYS finite element results and the method presented in this paper is shown in Fig. 6. The results when k takes values of 0, 1, 10, and \(+ \infty\) with the number of trial functions m = 10 and a grid size of 40 × 40 are shown in Fig. 7.

Example 2 L-shaped functionally graded plate

L-shaped functionally graded plate with Poisson’s ratio taken as 0.3, plate thickness h taken as 0.005 m, and uniform load size q as \(5 \times 10^{2}\) pa, where \(a = b = 0.5\),\(c = d = 0.125\) as shown in Figs. 8 and 9. The upper surface is ceramic, and the lower surface is steel, with the elastic modulus conforming to a power law function. The elastic modulus of the functionally graded plate, denoted as \(E(z)\), represents the variation of the plate’s elastic parameters (including elastic modulus and density) according to a law distribution along the thickness, and its value is

The elastic modulus of ceramic, denoted as \(E_{s}\), is taken as 210 GPa, and that of steel, denoted as \(E_{s}\), is taken as 390 GPa. Once the constituent materials of the functionally graded material are determined, the plate’s elastic modulus depends on the graded index. As the graded index increases, the proportion of ceramic in the material of the plate gradually decreases while the proportion of steel gradually increases. When the graded index increases to infinity, the material of the plate converges to a pure steel plate, and thus the maximum deflection also converges to the maximum deflection of the steel plate.

In this example, we take k = 0, k = 1, k = 10 and k = + ∞ respectively.

For different values of \(k\), substitute \(k\) into Eq. (13) to obtain \(E(z) = E_{c}\).Let n = 20 and discretize the thickness range \(\left[ { - h/2,h/2} \right]\) into many small thickness intervals. Discretize the thickness into n small intervals, with each interval’s thickness increment being \(\Delta z = h/n\). Define the discrete thickness points as \(z_{i} = - h/2 + i \times \Delta z\),where \(i = 0,1,2,...,n\). Calculate the strain energy contribution of each thickness interval. For each thickness interval \(\left[ {z_{i} ,z_{i + 1} } \right]\), calculate the value of \(E(z)\) at the midpoint \(z_{mid} = \left( {z_{i} + z_{i + 1} } \right)/2\).

Substituting into Eq. (43) will yield the coefficient equation set for calculating the results.

According to the R-function theory, the expression for \(\omega_{0}\) of the L-shaped functionally graded plate is as follows

where \(\omega_{1} = \frac{{a^{2} - x^{2} }}{2a} \ge 0\),\(\omega_{2} = \frac{{b^{2} - y^{2} }}{2b} \ge 0\),\(\omega_{3} = \left( {c - x} \right) \ge 0\) and \(\omega_{4} = (d - y) \ge 0\).

When the research object is a functionally graded thin plate, without considering the thickness stretching effect and only considering the bending term in the transverse displacement, it is assumed, so take \(w_{m} = w_{bm} ,w_{s} = 0\).The shape of the plate here is an asymmetrical figure. The function of the deflection w should be set as both an even function and an odd function of x and y, therefore \(w_{m}\) is taken as \(1\), \(x\), \(y\), \(x^{2}\), \(xy\), \(y^{2}\), \(x^{3}\), \(x^{2} y\), \(xy^{2}\) and \(y^{3}\)。

In finite element modeling, select the static structural analysis module. During meshing, set the side length of each element of the plate to be 0.028 m. The rectangular thin plate is divided into 1,205 square meshes in total.In MATLAB, the L-shaped plate is divided into two rectangles. The first rectangular plate is meshed with a grid of \(7n \times n\), and the second rectangular plate is meshed with a grid of \(8n \times 7n\). When k = 0, and m = 1, the results for different values of n are shown in Table 5; when n = 5, and m takes on different values, the results are shown in Table 6. The deflection curve of the plate center point when y = 0 is plotted in Fig. 10. When k = 0, n = 5 and m = 10, a comparison with the finite element calculation results from ANSYS is made and shown in Fig. 11.

When \(k = + \infty\), and m = 10, the results for different values of n are shown in Table 7; when n = 5, and m takes different values, the results are shown in Table 8. The deflection curve of the plate center point when y = 0 is plotted in Fig. 12. When n = 5 and m = 10, a comparison with the finite element calculation results from ANSYS is made and shown in Fig. 13.The above results confirm that the method presented in this paper is convergent and correct. When taking \(k = 0\), \(k = 1\), \(k = 10\), and \(k = + \infty\), with the number of test functions m = 10, and the grid number n = 5, the results are shown in Fig. 14. The trend indicates that, under the same conditions, the larger the value of k, the smaller the deflection at the center point. This phenomenon also verifies the correctness of the method presented in this paper.

Example 3 U-shaped functionally graded plate

The L-shaped functionally graded plate has a Poisson’s ratio of 0.3, a thickness h of 0.01 m, and a uniform load q of \(5 \times 10^{2} pa\), where \(a = b = 0.5\), \(c = d = 0.25\) as shown in Figs. 15 and 16.The upper surface is ceramic, and the lower surface is steel, with the elastic modulus conforming to a power law function. The elastic modulus of the functionally graded plate, denoted as \(E(z)\), represents the variation of the plate’s elastic parameters (including elastic modulus and density) according to a law distribution along the thickness, and its value is

The elastic modulus of ceramic, denoted as \(E_{c}\), is taken as 210 GPa, and that of steel, denoted as \(E_{s}\), is taken as 390 GPa. Once the constituent materials of the functionally graded material are determined, the plate’s elastic modulus depends on the graded index. As the graded index increases, the proportion of ceramic in the material of the plate gradually decreases while the proportion of steel gradually increases. When the graded index increases to infinity, the material of the plate converges to a pure steel plate, and thus the maximum deflection also converges to the maximum deflection of the steel plate.

In this example, we take \(k = 0\), \(k = 1\), \(k = 10\), and \(k = + \infty\) respectively.

For different values of \(k\), substitute \(k\) into Eq. (13) to obtain \(E(z) = E_{c}\). Let n = 20 and discretize the thickness range \(\left[ { - h/2,h/2} \right]\) into many small thickness intervals. Discretize the thickness into n small intervals, with each interval’s thickness increment being \(\Delta z = h/n\). Define the discrete thickness points as \(z_{i} = - h/2 + i \times \Delta z\),where \(i = 0,1,2,...,n\). Calculate the strain energy contribution of each thickness interval. For each thickness interval \(\left[ {z_{i} ,z_{i + 1} } \right]\), calculate the value of \(E(z)\) at the midpoint \(z_{mid} = \left( {z_{i} + z_{i + 1} } \right)/2\).

Substituting into Eq. (43) will yield the coefficient equation set for calculating the results.

According to the R-function theory, the expression for \(\omega_{0}\) of the U-shaped functionally graded plate is as follows

where \(\omega_{1} = \frac{{a^{2} - x^{2} }}{2a} \ge 0\),\(\omega_{2} = \frac{{b^{2} - y^{2} }}{2b} \ge 0\),\(\omega_{3} = \left( {c - x} \right) \ge 0\) and \(\omega_{4} = \frac{{y^{2} - d^{2} }}{2d} \ge 0\).

When the research object is a functionally graded thin plate, without considering the thickness stretching effect and only considering the bending term in the transverse displacement, it is assumed, so take \(w_{m} = w_{bm}\), \(w_{s} = 0\). The shape of the plate here is symmetrical about the y-axis. The function of the deflection w should be set as an odd function of x and an even function of y, therefore \(w_{m}\) is taken as \(1\), \(x\), \(y^{2}\), \(x^{3}\), \(y^{4}\), \(x^{5}\), \(y^{6}\), \(y^{8}\), \(xy^{4}\) and \(x^{3} y^{2}\)。

In finite element modeling, select the static structural analysis module. During meshing, set the side length of each element of the plate to be 0.028 m. The rectangular thin plate is divided into 1,145 square meshes in total. In MATLAB, the U-shaped functionally graded plate is divided into three rectangles. The first rectangle is meshed with a grid of \(4n \times n\), the second rectangle is meshed with \(3n \times 2n\), and the third rectangle is meshed with a grid of \(4n \times n\). When k = 0, and m = 10, the results for different values of n are shown in Table 9; when n = 12, and m takes different values, the results are shown in Table 10. When k = 0, the deflection curve of the functionally graded plate center point when y = 0 is plotted in Fig. 17.When k = 0, n = 5, and m = 10, a comparison with the finite element calculation results from ANSYS is made and shown in Fig. 18. When \(k = + \infty\), and m = 10, the results for different values of n are shown in Table 11; when n = 12, and m takes different values, the results are shown in Table 12. The deflection curve of the plate center point when y = 0 is plotted in Fig. 19. When n = 12 and m = 10, a comparison with the finite element calculation results from ANSYS is made and shown in Fig. 20. This proves that the method presented in this paper is convergent and correct. When taking k = 0, k = 1, k = 10 and k = + ∞, with the number of test functions m = 10, and the grid number n = 12, the results are shown in Fig. 21. The trend shows that, under the same conditions, the larger the value of k , the smaller the deflection at the center point. This phenomenon also verifies the correctness of the method presented in this paper.

Example 4 functionally graded thick plates with other shapes

A rectangular functionally graded plate with side lengths of 2a and 2b respectively has a small semi-circular arc with a radius of r removed from its right edge. And a = b = 0.5, c = 0.375, d = 0.0625, r = 0.0625. The Poisson’s ratio is taken as 0.3, the thickness of the plate is set to 0.16 m, and the magnitude of the uniformly distributed load q is \(2 \times 10^{7} pa\), as shown in Fig. 22. The upper surface of the rectangular functionally graded plate is ceramic, and the lower surface is steel. Its elastic modulus conforms to a power law function, so the elastic modulus \(E(z)\) of the functionally graded plate is expressed as the elastic parameters (including the elastic modulus and density) of the plate varying according to a law distribution with thickness, and its value is

The elastic modulus of ceramic, denoted as \(E_{c}\), is taken as 210 GPa, and that of steel, denoted as \(E_{s}\), is taken as 390 GPa. Once the constituent materials of the functionally graded material are determined, the plate’s elastic modulus depends on the graded index. As the graded index increases, the proportion of ceramic in the material of the plate gradually decreases while the proportion of steel gradually increases. When the graded index increases to infinity, the material of the plate converges to a pure steel plate, and thus the maximum deflection also converges to the maximum deflection of the steel plate.

In this example, we take k = 0, k = 1, k = 10 and k = + ∞ respectively.

For different values of \(k\), substitute \(k\) into Eq. (13) to obtain \(E(z) = E_{c}\).Let.

n = 20 and discretize the thickness range \(\left[ { - h/2,h/2} \right]\) into many small thickness intervals.Discretize the thickness into n small intervals, with each interval’s thickness increment being \(\Delta z = h/n\). Define the discrete thickness points as \(z_{i} = - h/2 + i \times \Delta z\),where \(i = 0,1,2,...,n\). Calculate the strain energy contribution of each thickness interval. For each thickness interval \(\left[ {z_{i} ,z_{i + 1} } \right]\), calculate the value of \(E(z)\) at the midpoint \(z_{mid} = \left( {z_{i} + z_{i + 1} } \right)/2\).

Substituting into Eq. (43) will yield the coefficient equation set for calculating the results.

According to the R-function theory, the expression for \(\omega_{0}\) of the U-shaped functionally graded plate is as follows

where \(\omega_{1} = \frac{{a^{2} - x^{2} }}{2a} \ge 0\omega_{2} = \frac{{b^{2} - y^{2} }}{2b} \ge 0\omega_{3} = \frac{{\left( {\left( {x - a} \right)^{2} + y^{2} - r^{2} } \right)}}{2r} \ge 0\omega_{4} = \frac{{y^{2} - d^{2} }}{2d} \ge 0\) and \(\omega_{5} = c + x \ge 0\).

When the research object is a functionally graded thick plate, it is assumed that \(w_{m} = w_{bm} + w_{sm}\). The shape of the plate here is an asymmetric figure. The trial function for setting the deflection should be an even function and an odd function of x and y. Therefore \(w_{bm}\) and \(w_{sm}\) are taken as: \(1\), \(x^{2}\), \(y^{2}\), \(x\), \(y^{4}\), \({\text{x}}^{3}\), \(y^{6}\), \(xy^{2}\), \(x^{2} y^{2}\) and \(x^{2} y^{4}\)。

In finite element modeling, select the static structural analysis module. During meshing, set the side length of each element of the plate to be 0.028 m. The rectangular thin plate is divided into 1,196 square meshes in total. In MATLAB, the functionally graded plate is divided into \(n \times n\) rectangles. After obtaining all the coordinates, the coordinates included by the small rectangles and semi-circular shapes are removed. When k = 0, and m = 10, the results for different values of n are shown in Table 13; when n = \(35 \times 35\), and m takes different values, the results are shown in Table 14. When k = 0, the deflection curve of the functionally graded plate center point when y = 0 is plotted in Fig. 23.When k = 0, n = \(35 \times 35\), and m = 10, a comparison with the finite element calculation results from ANSYS is made and shown in Fig. 24. When , and m = 10, the results for different values of n are shown in Table 15; when n = \(35 \times 35\), and m takes different values, the results are shown in Table 16. The deflection curve of the plate center point when y = 0 is plotted in Fig. 25. When n = \(35 \times 35\) and m = 10, a comparison with the finite element calculation results from ANSYS is made and shown in Fig. 26. This proves that the method presented in this paper is convergent and correct. When taking k = 0, k = 1, k = 10 and k = + ∞, with the number of test functions m = 10, and the grid number n = \(35 \times 35\) the results are shown in Fig. 27. The trend shows that, under the same conditions, the larger the value of k , the smaller the deflection at the center point. This phenomenon also verifies the correctness of the method presented in this paper.

By combining the R-function with the variational method, the R-function can accurately describe the boundaries of complex geometric shapes and transform irregular shapes into mathematical expressions, which greatly simplifies the numerical calculation process and ensures the accuracy of geometric information. Meanwhile, the variational method, based on the principle of energy minimization, converts the deflection problem into the problem of finding the minimum value of the energy functional. This combined approach can not only properly handle complex geometric boundaries but also ensure that the calculation results have high accuracy, demonstrating good effectiveness in dealing with the deflection calculations of functionally graded plates with different shapes such as rectangular, U-shaped, and L-shaped, as well as those with varying thicknesses. In terms of the number of trial functions and the fineness of mesh division, they have an important impact on the calculation results. As for the trial functions, they are used in this method to describe the possible deformation modes of functionally graded plates. When the number of trial functions increases, it can fit the actual deformation situation more precisely. For example, when considering the shear deformation of functionally graded plates, adding trial functions that contain terms related to shear deformation can describe the actual deformation of the plates under load more accurately. This is consistent with the plate theory physical model that takes shear deformation into account, thereby improving the accuracy of the calculation results. Similarly, the finer the mesh division is, the closer the calculation results will be to the finite element solutions. The consistency with the finite element results further confirms the value of this method in engineering applications.

However, in specific computational examples (such as Example 1, Example 2, Example 3, and Example 4), if discrepancies are observed compared to the results calculated by ANSYS software, these discrepancies may be caused by the following factors.

Firstly, the trial functions selected in this paper may inadvertently satisfy some boundary conditions that do not actually exist in the non-boundary areas, which could interfere with our computational results. Taking \(x^{2}\) as an example, this function is always zero on the line \(x = 0\), which is clearly contrary to the situation we are considering.

Secondly, in the discussion of this paper, there may be a limitation, which is that an insufficient number of trial functions may not have been included when selecting them. In the analysis of Example 2, it can be observed that when the value of m is low, meaning that the number of trial functions is small, there is a deviation between the final calculated results and those provided by ANSYS software. This finding points out that in order to obtain a more accurate solution through the variational method, we must increase the number of trial functions as much as possible to ensure the reliability and accuracy of the results.

Thirdly, when performing integral operations on R-functions, you may encounter the special case where the denominator is zero at the boundary. Therefore, it is necessary to adopt a method similar to finite element analysis, which involves dividing the area into a mesh and solving the integral of each mesh element one by one, then accumulating to obtain the overall solution. This process emphasizes the importance of the fineness of the mesh division for the accuracy of the final result. When applying a numerical solution strategy that combines R-functions with the variational principle, to improve the accuracy of the solution, a denser mesh division should be used in the calculation process.

Fourthly, in the discussion of this paper, the calculation of the deflection of thick plates relies highly on the shear correction factor. Specifically, for those plate components that are relatively thin in thickness but still classified as thick plates, using the same shear correction factor may introduce errors, because the mechanical behaviors of such plate components are different from those of thicker thick plates. To solve this problem, corresponding shear correction factors can be determined through experiments and simulation analyses for thick plates with different thicknesses, so as to improve the accuracy of deflection calculation. Therefore, one of the future research directions is to establish a shear correction factor model based on the thickness differences of thick plates, thereby predicting the deflection behaviors of thick plates of various thicknesses more accurately.

Conclusions

The variational method is widely applied to solve engineering and physical problems, especially in calculating the deformation and stress distribution of functionally graded materials. However, when dealing with functionally graded plates of complex shapes, the traditional variational method may encounter some challenges. At this point, introducing the concept of the R-function can serve as a supplementary method to handle the complexity of boundary conditions.

The R-function can describe complex geometric shapes through implicit functions without directly defining the boundaries. Combining the R-function with the variational method can effectively simplify the bending problem of functionally graded plates under complex boundary conditions. This paper combines the R-function and the variational principle through theoretical derivation, thereby providing a new method for solving deflection variations. This method not only improves the efficiency of the solution process but also enhances the applicability and flexibility of the model. The paper demonstrates the effectiveness of this combined method by combining specific engineering examples. Through comparative analysis, the consistency between the calculated results using the R-function and the variational method and the actual measured values is observed, verifying the accuracy and reliability of the method.

Furthermore, this paper also explores the relationship between the calculation results and factors such as the selection of test functions in the variational method and the division of integration grids. This analysis helps to optimize the calculation process, improve the accuracy of the results, and also provides theoretical support and practical guidance for the application of the R-function in the bending problem of functionally graded plates.

In summary, the combination of the R-function and the variational method provides a new perspective and method for solving the bending problem of functionally graded plates with complex boundaries. This combination can improve computational efficiency.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to restrictions e.g. privacy but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Vasile, M. S. N. Displacement calculus of the functionally graded plates by finite element method. Alex. Eng. J. 61(12), 12075–12090 (2022).

Minoo Naebe, K. S. Functionally graded materials: A review of fabrication and properties. Appl. Mater. Today 5, 223–245 (2016).

Kishore, V. K. Elastoplastic behaviour of multidirectional porous functionally graded panels: A nonlinear FEM approach. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Mech. Eng. 48(1), 307–329 (2023).

Zhuang, W. et al. Free vibration analysis of functionally graded porous plates based on a new generalized single-variable shear deformation plate theory. Arch. Appl. Mech. 93(6), 2549–2564 (2023).

Markworth, A. J., Ramesh, K. S. & Parks, W. P. Modelling studies applied to functionally graded materials. J. Mater. Sci. 30(9), 2183–2193 (1995).

Mobtasem, M. et al. Implementation of a new approach based on the functionally graded materials concept to improve the strength of laminated composites containing open-hole. Polymer Compos. 45, 12132–12146 (2024).

Pathan, F., Singh, S., Natarajan, S. & Watts, G. An analytical solution for the static bending of smart laminated composite and functionally graded plates with and without porosity. Arch. Appl. Mech. 92(3), 903–931 (2022).

Mohammadi, M. et al. Bending, buckling and free vibration analysis of incompressible functionally graded plates using higher order shear and normal deformable plate theory. Appl. Math. Model. 69, 47–62 (2019).

Vu, T. V. N. et al. A simple FSDT-based meshfree method for analysis of functionally graded plates. Eng. Anal. Bound. Elem. 79, 1–12 (2017).

Vu, T. V. K. et al. A new refined simple TSDT-based effective meshfree method for analysis of through-thickness FG plates. Appl. Math. Model. 57, 514–534 (2018).

Vu, T. V. K. et al. Enhanced meshfree method with new correlation functions for functionally graded plates using a refined inverse sin shear deformation plate theory. Eur. J. Mech.-A/Solids 74, 160–175 (2019).

Vu, T.V.C.-S. et al. A refined sin hyperbolic shear deformation theory for sandwich FG plates by enhanced meshfree with new correlation function. Int. J. Mech. Mater. Des. 15, 647–669 (2019).

Vu, T.V.N.-V. et al. Meshfree analysis of functionally graded plates with a novel four-unknown arctangent exponential shear deformation theory. Mech. Based Des. Struct. Mach. 51(2), 1082–1114 (2023).

Vu, T. V. N. et al. A refined quasi-3D logarithmic shear deformation theory-based effective meshfree method for analysis of functionally graded plates resting on the elastic foundation. Eng. Anal. Bound. Elem. 131, 174–193 (2021).

Vu, T. Mechanical behavior analysis of functionally graded porous plates resting on elastic foundations using a simple quasi-3D hyperbolic shear deformation theory-based effective meshfree method. Acta Mech. 233(7), 2851–2889 (2022).

Vu, T.V.N.-V. et al. Buckling analysis of the porous sandwich functionally graded plates resting on Pasternak foundations by Navier solution combined with a new refined quasi-3D hyperbolic shear deformation theory. Mech. Based Des. Struct. Mach. 4, 1–27 (2022).

Cao, H.-L. & Tan-Van, V. Natural frequencies analysis of functionally graded porous plates supported by Kerr-type foundations via an innovative trigonometric shear deformation theory. Int. J. Struct. Stabil. Dyn. (2024)

Vu, T.-V. et al. Deflection, stresses and buckling analysis of porous FGM plates with Kerr-type elastic foundations using a new five-unknown trigonometric shear deformation theory. Int. J. Comput. Methods (2024).

Cao, H.-L. & Vu, T.-V. Free vibration analysis of the functionally graded porous plates with auxetic honeycomb core laid on Kerr-type elastic foundation. CIGOS 2024, 425–433 (2024).

Anupam, C. et al. Bending analysis of functionally graded sandwich plates using HOZT including transverse displacement effects. Mech. Based Des. Struct. Mach. 50(10), 3563–3577 (2022).

Vu, T. V. et al. Buckling of shear-deformable plates. AIAA J. 25(9), 1268–1271 (1987).

Lee, Y. Y. Z. et al. Thermoelastic analysis of functionally graded plates using the element-free kp-Ritz method. Smart Mater. Struct. 18, 035007 (2009).

Nguyen-Xuan, H. Analysis of functionally graded plates using an edge-based smoothed finite element method. Compos. Struct. 93, 3019–3039 (2011).

Nguyen-Xuan, H. Analysis of functionally graded plates by an efficient finite element method with node-based strain smoothing. Thin-Walled Struct. 54, 1–18 (2012).

Tran, L. V. F. et al. Isogeometric analysis of functionally graded plates using higher-order shear deformation theory. Compos. B 51, 368–383 (2013).

Do, V. N. V. & Lee, C.-H. Nonlinear analyses of FGM plates in bending by using a modified radial point interpolation mesh-free method. Appl. Math. Model. 57, 1–20 (2018).

Nguyen, T. H. A. Nonlocal continuum damage modeling for functionally graded plates of third-order shear deformation theory. Thin-Walled Struct. 164, 107876 (2021).

Zhang, D.-G. Nonlinear bending analysis of FGM beams based on physical neutral surface and high order shear deformation theory. Compos. Struct. 100, 121–126 (2013).

Yu, Y., Zhu, X., Li, T. & Guo, W. Free vibration analysis of functional gradient Mindlin plate of arbitrary shape. Open J. Acoust. Vib. 07(01), 1–13 (2019).

Chen, W. Q. et al. Two-dimensional elasticity solutions for functionally graded beams resting on elastic foundations. Compos. Struct. 84(3), 209–219 (2008).

Sahraee, S. Bending analysis of functionally graded sectorial plates using Levinson plate theory. Compos. Struct. 88(4), 548–557 (2009).

Hadji, L. et al. Bending analysis of FGM plates using a sinusoidal shear deformation theory. Wind Struct. Int. J. 23, 543–558 (2016).

He, J. L. L. Closed-form solutions for nonlinear bending and free vibration of functionally graded microplates based on the modified couple stress theory. Compos. Struct. 131, 810–820 (2015).

Carrera, K. et al. Stress, vibration and buckling analyses of FGM plates—A state-of-the-art review. Compos. Struct. 120, 10–31 (2015).

Yang, B. et al. Elasticity solutions for functionally graded plates in cylindrical bending. Appl. Math. Mech. 29(8), 999–1004 (2008).

Zhao, F. W. Bending analysis of functionally graded materials beam considering different shear deformation theory. J. Mech. Eng. 50(1), 104–110 (2014).

Zenkour, A. M. Generalized shear deformation theory for bending analysis of functionally graded plates. Appl. Math. Model. 30(1), 67–84 (2006).

Mazaheri, M. S. H. Bending analysis of five-layer curved functionally graded sandwich panel in magnetic field: closed-form solution. Appl. Math. Mech. 42(2), 251–274 (2021).

Liu, W. & Zhong, Z. Three-dimensional bending analysis of simply supported functionally graded plates with arbitrary gradient distributions. J. Compos. Mater. 26(2), 195–199 (2009).

Sklepus, S. M. Numerical-and-analytical method for solving geometrically nonlinear bending problems of complex-shaped plates from functionally graded materials. Strength Mater. 55(5), 927–936 (2023).

Al, N. U. et al. Cross-sectional warping and precision of the first-order shear deformation theory for vibrations of transversely functionally graded curved beams. Appl. Math. Mech. 44(12), 2109–2138 (2023).

Al, T. L. et al. Variable cross sections functionally grad beams on Pasternak foundations: An enhanced interaction theory for construction applications. Arch. Appl. Mech. 94(4), 1005–1020 (2024).

Al, V. S. et al. Electrohydrodynamic-jetting (EHD-jet) 3D-printed functionally graded scaffolds for tissue engineering applications. J. Mater. Res. 33(14), 1999–2011 (2018).

Rizov, I. V. On the application of non-linear rheological models in longitudinal fracture analysis of beams made of functionally graded materials. Strength Mater. 56(1), 105–111 (2024).

Jha, D. K., Kant, T. & Singh, R. K. A critical review of recent research on functionally graded plates. Compos. Struct. 96, 833–849 (2013).

Shao, W. & Wu, X. Fourier differential quadrature method for irregular thin plate bending problems on Winkler foundation. Eng. Anal. Boundary Elem. 35(3), 389–394 (2011).

Reissner, E. The effect of transverse shear deformation on the bending of elastic plates. ASME J. Appl. Mech. 12, 68–77 (1945).

Mindlin, R. Influence of rotary inertia and shear on flexural motions of isotropic elastic plates. J. Appl. Mech. 18(1), 31–38 (1951).

Timoshenko, S. On the transverse vibrations of bars of uniform cross section. Phil. Mag. 43(253), 125–131 (1922).

Thai, H. T. & Choi, D. H. A simple first-order shear deformation theory for the bending and free vibration analysis of functionally graded plates. Compos. Struct. 101, 332–340 (2013).

Thai, H.-T. et al. Analysis of functionally graded sandwich plates using a new first-order shear deformation theory. Eur. J. Mech. A/Solids 45, 211–225 (2014).

Vendhan, C. P. D. et al. Application of Rayleigh-Ritz and Galerkin methods to non-linear vibration of plates. J. Sound Vib. 39(2), 147–157 (1975).

Zhu, F. Rayleigh-Ritz method in coupled fluid-structure interacting systems and its applications. J. Sound Vib. 186(4), 543–550 (1995).

Al-Obeid, A. & Cooper, J. E. A Rayleigh-Ritz approach for the estimation of the dynamic properties of symmetric composite plates with general boundary conditions. Compos. Sci. Technol. 53(3), 289–299 (1995).

Kurpa, L. V. M. et al. Method of R-function for investigation of parametric vibrations of orthotropic plates of complex shape. J. Math. Sci. 174(3), 269–282 (2011).

Butler, K. T., Sai Gautam, G. & Canepa, P. Designing interfaces in energy materials applications with first-principles calculations. npj Comput. Mater. 5(1), 990–1001 (2019).

Sagar, T. V., Potluri, P. & Hearle, J. W. S. Mesoscale modelling of interlaced fibre assemblies using energy method. Comput. Mater. Sci. 28(1), 49–62 (2003).

Kurpa, L. S. T. & Awrejcewicz, J. Vibration analysis of laminated functionally graded shallow shells with clamped cutout of the complex form by the Ritz method and the R-functions theory. Latin Am. J. Solids Struct. 16(1), 1–16 (2019).

Awrejcewicz, J. K. & Osetrov, A. Investigation of the stress-strain state of the laminated shallow shells by R-functions method combined with spline-approximation. Z. Angew. Math. Mech. 91(6), 458–467 (2011).

Kurpa, L. V. S. & Timchenko, G. Free vibration analysis of laminated shallow shells with complex shape using the R-functions method. Compos. Struct. 93, 225–233 (2010).

Xia, F. & Li, S. R-Function and variation method for bending problem of clamped thin plate with complex shape. Adv. Mech. Eng. 13(7), 1–13 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Software and writing-original draft preparation, Kexin Su; Resources, Investigation and writing-review and editing, Shanqing Li.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Su, K., Li, S. R-function method and variational method for the bending problem of functionally graded plates with fixed supports and complex shapes. Sci Rep 15, 13226 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97325-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97325-4