Abstract

Based on the data from 30 provinces in China from 2011 to 2021, the article measures the green finance index through the entropy value method and introduces the synergistic emission intensity to measure the synergistic effect of pollution reduction and carbon reduction. Empirically examines the pollution control and emission reduction effects of green finance through the spatial Durbin model and analyzes the results .The study shows that: The discrete degree of development of national green finance level increases and the development tends to be balanced, while the synergistic emission intensity tends to be more concentrated in space. There is an inverted “U” curve relationship between green finance and synergistic emission intensity in terms of direct effect and spatial spillover effect .Heterogeneity analysis shows that green finance has a more significant impact on synergistic emission intensity in central and western China. The results of the study are of great significance to the development of green finance and the realization of low-carbon development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction and literature review

Since the onset of industrialization, humanity has accumulated significant material wealth, but this progress has come at a heavy cost to natural resources, exacerbating urgent environmental challenges. The degradation of air quality and the escalation of global temperatures have intensified the tension between human activities and the environment. As a result, addressing air pollution, mitigating the greenhouse effect, and tackling environmental degradation have become critical global priorities. In response to climate change, nations, including China, have committed to a green transition. The 2015 Paris Agreement, which seeks to limit global warming to well below 2 °C, with a goal of 1.5 °C1, marked a significant milestone in this effort. As the world’s largest emitter of carbon dioxide and a leading energy consumer, China plays a crucial role in the global pursuit of environmental sustainability. Despite its remarkable economic growth, China’s energy structure remains heavily reliant on fossil fuels, leading to severe environmental challenges, particularly in terms of both pollution and carbon emissions. In 2022, coal consumption accounted for 56.2% of China’s total energy consumption, with fossil fuels comprising over 60% of its energy mix (China Energy Data Report, 2023)2. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), China’s carbon dioxide emissions exceeded 10.2 billion tons in 2022, contributing to approximately one-third of global emissions3. This poses significant barriers to China’s sustainable development, underscoring the urgent need to promote synergies between pollution reduction and carbon mitigation efforts4,5.

It is urgent to promote synergies between pollution reduction and carbon reduction efforts6. Encouraging these synergies not only enhances environmental quality but also facilitates the optimization and upgrading of the economic structure. At the 75th United Nations General Assembly, China committed to achieving carbon peaking by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 20607. Achieving this ambitious goal requires optimizing the energy structure and promoting the green transformation of industries through an integrated approach to both pollution reduction and carbon emission reduction. However, the existing literature primarily focuses on national-level strategies and the direct effects of green finance on emissions reduction, with less attention paid to the regional disparities in green finance development and how these disparities affect the synergy between pollution and carbon reduction. Understanding the spatial spillover effects of green finance policies—where one region’s policies can influence neighboring areas—becomes crucial for maximizing the overall impact. The concept of synergistic emission intensity serves as a comprehensive indicator to characterize the interplay between these efforts, allowing for the simultaneous consideration of multiple pollutants and providing a more holistic assessment of both pollutant and carbon emissions8. Moreover, addressing inefficiencies in resource allocation is key to promoting greener and more sustainable economic development. Green finance, which integrates environmental concerns into financial decision-making, is emerging as a powerful tool to achieve these combined benefits of pollution reduction and carbon emission reduction. As traditional financial models often prioritize economic returns over environmental sustainability, green finance focuses on investment strategies and financial practices that prioritize environmental protection and promote long-term sustainable development9. Green finance encompasses a variety of financial instruments designed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and mitigate climate change impacts. It directs capital to environmentally friendly and low-carbon industries, optimizing resource allocation and encouraging the allocation of production factors to support green enterprises. Ultimately, this transformation helps shift industrial structures toward more sustainable models10. China introduced the concept of green finance in its Twelfth Five-Year Plan in 2011 and has since outlined specific strategies for green development in its Thirteenth Five-Year Plan. Despite this progress, the role of green finance in addressing the interconnected impacts of pollution and carbon reduction, particularly through spatial spillover effects, remains underexplored. These effects involve complex interactions between regional economic and environmental policies and are not merely about cross-regional transmission; they involve multifaceted dimensions such as policy, market forces, technology, and capital11,12. Investigating the spatial spillover effects of green finance can provide deeper insights into how policies across different regions can trigger interconnected reactions at multiple levels. This research holds considerable theoretical and practical significance for policymakers, enabling them to optimize the synergistic benefits of pollution and carbon reduction while minimizing the potential negative spillovers arising from disconnected or delayed policies. Furthermore, this study offers valuable lessons not only for China but also for other countries and regions seeking to advance environmental governance and enhance the global response to climate change13,14.

Current academic research on the macro effects of green finance primarily examines its impact on energy transition, environmental pollution, sustainable development, and high-quality development15. Studies on green finance’s impact on the energy transition have shown that it supports technological advancements and the modernization of industrial structures, facilitating both structural changes and improvements in efficiency. Similarly, research has also explored green finance’s effect on environmental pollution, demonstrating its ability to reduce pollution by optimizing industrial structures, transforming energy systems, and encouraging green technological innovation16,17. Further studies indicate that green finance can significantly alter energy consumption patterns and accelerate the achievement of economic sustainability by efficiently utilizing resources such as labor and land17,18,19,20. Based on data from 19 OECD countries, green finance offers a substantial opportunity for major economies to adopt energy-saving models and reduce energy consumption in pursuit of sustainable development. Additionally, some researchers have investigated the role of green finance in carbon emission reduction, highlighting its positive effects in resource-rich countries through fintech adoption and renewable energy usage, which help lower CO2 emissions21,22. In China, research suggests that green finance has a more significant carbon reduction impact in developed and western regions. However, despite the growing body of literature on the role of green finance in sustainable development, there is limited exploration of its synergistic effects on both pollution reduction and carbon reduction23. The existing studies often focus on individual or sector-specific effects, neglecting how green finance can drive broader, more integrated synergies between these two critical environmental objectives. While studies have explored the impact of green finance on sustainable development across various countries and regions—including Japan, India, Brazil, and Russia20,24,25—there remains a notable gap in the literature regarding the spatial effects of green finance, particularly spillover effects. These spillover effects—where policies in one region influence neighboring regions—have not been thoroughly explored, especially in countries with significant regional disparities, such as China26. Understanding these spatial dynamics is essential for identifying how green finance policies in one region may have positive or negative implications for surrounding regions, ultimately shaping the overall effectiveness of pollution and carbon reduction strategies27.

While some research has explored the impact of green finance on pollution and carbon reduction, much of this literature focuses primarily on the emission of individual pollutants, particularly air pollutants like CO2 and O3. There is less emphasis on other types of pollution, such as particulate matter or sulfur dioxide (SO2)28. Furthermore, although several methods exist to measure the synergistic effects of pollution reduction and carbon reduction, they often consider these effects in isolation or with limited scope. For instance, some studies incorporate resource inputs and energy efficiency as additional indicators to assess the synergistic effects29,30. These studies typically measure the synergistic effects by including CO2 and SO2 emissions as key variables, and some researchers have used the rate of change or intensity of carbon and pollution emissions to evaluate these effects31. Other scholars have examined synergy, path synergy, and effect coordination, employing composite system synergy models to assess the strength of the synergistic effects between pollution and carbon reduction. Additionally, some studies have utilized econometric regression models to quantify how reducing carbon emissions can lead to a decrease in air pollutants, or vice versa, where reductions in air pollutants contribute to carbon emission reductions32. However, these studies tend to focus on individual or partial pollution factors, often overlooking the broader, integrated effects and the complex spatial dynamics that occur across regions.

This paper constructs comprehensive indicators to measure the development of green finance and synergistic emission intensity based on panel data from 30 provincial-level administrative regions in China from 2011 to 2021. It aims to further reveal the spatial and temporal evolution of these two variables, identifying regional differences and the underlying causes for such disparities. Through the construction of spatial econometric models, this study will analyze the direct and indirect effects of green finance, as well as explore the spatial heterogeneity of synergistic emission intensity across regions. The ultimate goal is to provide policy recommendations aimed at promoting inter-regional policy coordination and cooperation, contributing to the broader goal of advancing environmental sustainability and the construction of a “beautiful China.”

The contributions of this paper are threefold: (1) It employs the spatial Durbin model to test the synergistic effects of green finance on pollution and carbon reduction, with a particular focus on spatial spillover effects. This analysis will provide a more comprehensive theoretical framework, enhancing our understanding of how green finance can optimize the effects of pollution and carbon reduction across regions. (2) This paper introduces the concept of synergistic emission intensity, incorporating pollutants such as sulfide, soot, and CO2, to comprehensively measure the level of synergy between pollution reduction and carbon reduction efforts. This broader approach provides a more rigorous assessment of these synergies, compared to studies that focus on a narrower set of emissions. (3) Using standard deviation ellipses and spatial Markov chains, the study illustrates the spatial and temporal characteristics of the synergistic effects of green finance on pollution reduction and carbon reduction, revealing the evolution of these effects over time and identifying the reasons behind their changes.

Theoretical analysis and research hypothesis

In the early stages of development, green finance may encounter regulatory gaps during project implementation due to incomplete regulatory policies, industry standards, and certification systems, which can impact the effectiveness of pollution reduction. At the same time, green finance may prioritize supporting large-scale projects, which do not necessarily lead to significant direct pollution reduction effects. These projects may even drive the expansion of related industries, increasing energy and resource consumption in the short term, thus raising pollution emissions. As green finance develops further, it can promote the flow of funds toward low-carbon, low-pollution, and environmentally friendly enterprises and projects through capital guidance, financial innovation, and information disclosure. This can suppress high carbon emissions and environmental pollution, thereby having a suppressive effect on collaborative emission intensity. Before reaching a certain threshold, the level of green finance has a promoting effect on collaborative emission intensity; after exceeding the threshold, its suppressive effect on collaborative emission intensity gradually emerges, presenting an inverted “U” curve relationship overall. The relationship between green finance and emission reduction follows a non-linear dynamic, characterized by a threshold effect. Initially, green finance may have limited impact on emissions due to insufficient policies and potential support for high-energy industries. However, as green finance policies mature and funding begins to flow toward low-carbon projects, emission reductions become more pronounced16,17. Beyond a certain threshold, the impact of additional green finance investments declines, as resources may be misallocated or emissions may shift to less regulated regions. This decline in emission reduction beyond a certain threshold can be explained by microeconomic mechanisms, where early-stage green finance may lead to suboptimal resource allocation, while later-stage finance fosters structural adjustments in industry and technological innovation aimed at sustainable growth25,26,27.

H1:

There is an inverted “U” shaped relationship between the level of green finance and collaborative emission intensity.

The development of green finance not only affects the collaborative emission intensity of the region but also influences the collaborative emission intensity of neighboring regions through economic links, technological exchanges, and policy interactions. For example, the rapid development of green finance in a particular region may attract green industry investment from surrounding areas, promote green technological innovation and diffusion between regions, and thereby reduce the collaborative emission intensity of nearby regions. Furthermore, while green finance products lower the financing costs for environmentally friendly enterprises, they increase the financing costs for polluting enterprises. This may lead polluting enterprises to relocate to neighboring regions with lower levels of green finance. However, as the level of green finance increases, this shifting effect will gradually weaken, and the collaborative emission reduction effect between regions will gradually strengthen. In regions with a high level of green finance, the collaborative emission intensity of neighboring regions will decrease due to the spatial spillover effects of green finance. This spatial spillover effect will gradually strengthen as the level of green finance increases, also presenting an inverted “U” shape.

H2:

Green finance has a significant spatial spillover effect on collaborative emission intensity.

There are significant differences in the economic development level, industrial structure, resource endowments, and policy environment between different regions in China, and these factors all affect the mechanism and effectiveness of green finance on collaborative emission intensity. The eastern region has a high level of economic development, a prominent industrial structure optimization effect, and has already made considerable progress in green technological innovation and application. Therefore, the impact of green finance on collaborative emission intensity may be relatively small. The central and western regions possess abundant clean energy resources, and the development of green finance can better promote regional industrial upgrading and green technological innovation, which may have a more significant effect on suppressing collaborative emission intensity. In the central and western regions, the inverted “U” effect of green finance on collaborative emission intensity is more evident, meaning that once the level of green finance reaches a certain threshold, its suppressive effect on collaborative emission intensity becomes stronger. In contrast, in the eastern region, the impact of green finance on collaborative emission intensity may be insignificant or smaller.

H3:

The impact of green finance on collaborative emission intensity exhibits heterogeneity across different regions.

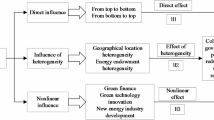

Figure 1 is the theoretical framework of this study.

Research methodology, selection of variables and data sources

Research methodology

Standard deviation elliptic analysis

Standard deviation ellipse analysis (SDE) combined with GIS techniques can depict visualized standard deviation ellipses33, based on the parameters of area, long axis, short axis and center of gravity provided by it, it can identify the central migration routes and spatial distribution patterns of green finance and synergistic emission intensities in China’s provincial-level administrative regions. Its expression is:

n denotes the number of provinces, (xi,yi) denotes the geographic coordinates of province i in latitude and longitude, wi denotes the corresponding green finance or synergistic emission intensity index of province I, (\(\overline {X}\), \(\overline {Y}\)) denotes the weighted average center of gravity coordinates; (\({\tilde {x}_i}\), \({\tilde {y}_i}\)) denotes the coordinate deviation of province i to the mean center of gravity, tanθ denotes the direction angle of the spatial distribution and σx,σy denote the ellipse long and short axis standard deviation, respectively.

Standard deviation ellipse analysis is used to analyze the spatial distribution of green finance impacts on pollution and carbon reduction. This method allows us to visualize how these effects evolve over time and space, providing insight into the regional disparities in the effectiveness of green finance policies.

Spatial Markov chain

The spatial Markov Chain introduces the concept of “spatial lag” on the basis of the traditional Markov Chain, which makes up for the shortcomings of the traditional Markov Chain that ignores the spatial spillover effect and can better reveal the spatial interaction with neighboring regions during the process of change of a certain attribute of a region34. The spatial Markov chain conditioned on the spatial lag type (k types) of the region a in the initial year decomposes the k×k traditional Markov chain transfer probability matrix into k×k conditional transfer probability matrices.

The specific formulas are as follows:

xi denotes the value of an attribute of a region; wij denotes the spatial lag weight, in this paper, we adopt the neighboring criterion, i.e., region I and region j are adjacent to each other and its value is 1, otherwise, it is 0. When i = j, wij = 0.

Spatial autocorrelation analysis

In this paper, the Moran index is chosen to measure the spatial correlation between green finance and synergistic emission intensity35. If the value is greater than 0, it proves positive spatial correlation; if the value is less than 0, it indicates negative spatial correlation; if the value is 0. it indicates spatial randomness. The specific formula is:

n denotes the number of provinces, wij denotes the weight matrix and xi denotes the green finance or synergistic emission intensity index of province i.

Spatial Durbin model and decomposition of Spatial effects

This paper employs a spatial panel Durbin model to assess the spatial spillover impact of green finance on the intensity of coordinated emissions. In light of the potential nonlinear association between the two variables, a quadratic term for green finance is incorporated36. The resulting model is presented below:

The variable lnSCpgit represents the comprehensive index of collaborative emissions intensity in province i during year t. The symbol ρ denotes the spatial lag coefficient, while wij refers to the weight matrix. Gfit and Gfit 2 represent the green finance index and its squared term for province i in year t, respectively. The variable Zit encompasses a set of control variables. The coefficients β1 and β2 indicate the elasticities of the core explanatory variables and their squared terms, respectively. Similarly, γ1 and γ2 represent the spatial autoregressive coefficients of the core explanatory variables and their squared terms. The term µi indicates the regional effect, δi reflects the time effect and εi represents the random disturbance term, which follows an independent distribution. In addition, when applying the spatial panel Tobit model, the traditional point estimation cannot capture the spatial spillover effects, which leads to bias in the parameter estimation, so it is necessary to use partial differential methods to decompose the spatial effects to compensate. The general spatial panel Tobit model is transformed into a matrix model and decomposed as follows:

In Formula (8), I represents the identity matrix, ln represents the N × 1 unit vector, ε is a specific effect in time and space and (I − ρW)−1 = I + ρW + ρ²W² + ρ³W³ + …. Equation (9) represents the partial differential matrix of the kth variable in the explanatory variable X of the first to nth region with respect to Y. The direct effect signifies the impact of the explanatory variable on the explained variable within this region and is quantified by the mean of all elements The direct effect is measured by the diagonal of the matrix, while the indirect effect (spillover effect) is measured by the average of all elements in the row or column of the non-diagonal line, as illustrated in Eq. (10). The total effect is the sum of the two.

The Spatial Durbin Model is employed to examine the spatial spillover effects of green finance policies. Unlike traditional models that treat regions independently, this model allows us to account for interdependencies between neighboring regions, providing a more accurate understanding of how green finance impacts both local and adjacent areas.

Spatial weight matrix setting

The spatial spillover effect of green finance on the intensity of coordinated emissions is influenced by two key factors: the level of economic development in different provinces and geographical distance. To account for these variables, a spatial econometric model has been developed, incorporating a spatial economic distance matrix and a geographical adjacency matrix. To enhance the reliability of the findings, an economic geography nesting matrix has been incorporated into the study.

Geographical adjacency matrix:

Economic distance matrix:

Economic geography nested matrix:

Variable selection

Core explanatory variable: green finance index measurement

A green finance index system is constructed based on five dimensions: green credit, green securities, green investment, green insurance and environmental protection support (Table 1) and the entropy weighting method is used to measure the level of green finance in each province. Green credit is expressed as the ratio of interest expenses of high-energy-consuming industries to the total interest expenses of industries. High-energy-consuming industries mainly include electric power and heat generation and supply, non-metallic mineral products, ferrous metal smelting and rolling, non-ferrous metal smelting and rolling, chemical raw materials and chemical products manufacturing, petroleum refining, coking and nuclear fuel processing; green securities are expressed as the ratio of the total market value of high-energy-consuming industries to the total market value of A shares; Green investment is expressed as the ratio of total investment in environmental protection to the regional gross domestic product; green insurance is expressed as the ratio of agricultural insurance income to the total value of agricultural output; and environmental protection support is expressed as the ratio of fiscal expenditure on environmental protection to general budget expenditure. Among them, green credit and green securities are negative indicators. Since the values of the two indicators are between 0 and 1, they are processed in a positive way by subtracting 1 from each indicator.

The green finance index is constructed using five dimensions: capital investment, green credit, government policy support, green bonds, and green industry investments. These dimensions were chosen based on the existing literature and green finance theory, as they collectively reflect the key components of green finance that influence environmental outcomes. Studies have shown that these factors are strongly correlated with both pollution reduction and carbon reduction efforts.

Dependent variable: collaborative emission intensity

Drawing on the concept of “emission intensity”37,38, a comprehensive indicator of synergy emission intensity, SCpg (the Synergy of Co-control of Air Pollutants and GHGs, covering SO, PM and CO2, is constructed to normalize urban air pollutant emissions and CO2 emissions.

δ is the combined emission equivalent of SO2, smoke and dust and CO2; GDP is the annual average GDP of each provincial-level autonomous region; Q(X) is the emission equivalent of SO2, smoke and dust and CO2; τ, φ and ω are the conversion coefficients for SO2, smoke and dust and CO2, respectively, where, reference is made to the tax item tax schedule of China’s environmental protection tax to determine the values, which are 1/0.95 and 1/2.18, respectively. Since CO2 is the only greenhouse gas considered in this study, the value is taken as 1; λ1 and λ2 are the relative weight factors of air pollutants and greenhouse gas emissions, respectively, which are used to reveal the relative importance of the two in terms of monetary value. Based on the tax rate range of air pollutants in China’s environmental protection tax, which is 1.2–12 yuan per pollution equivalent, and 6.0 yuan per air pollution equivalent is selected as the price of air pollutants, making λ1 1; the average price of carbon trading in key environmental protection cities from 2011 to 2021 is 22 yuan/t (calculated in terms of CO2 equivalent emissions), which means that the value of the weight factor λ2 for greenhouse gas emissions relative to air pollutants is 0.0037.

Control variables

Drawing on relevant research, the following indicators are selected as control variables: (1) Environmental regulation: the proportion of the frequency of occurrence of words related to “environment” in local government work reports to the total frequency of occurrence of words in the full text of the report (Der) is used to reflect. (2) Investment openness (Fdi): measured by the proportion of foreign direct investment in GDP. (3) Industrialization level (Il): expressed as the proportion of industrial added value to GDP. (4) Technological progress (Atp): reflected by the logarithm of the number of patent applications authorized in each province and city. (5) Industrial structure (Is): expressed as the proportion of the added value of the tertiary industry to GDP. (6) Level of economic development (LnGDP): measured by taking the logarithm of GDP.

Data sources

The availability and validity of the data are considered comprehensively. This paper selects 30 provinces in China from 2011 to 2021 as the research object. Due to the availability of relevant data and the consistency of statistical standards, Tibet Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan are not included in the scope of the study. At the same time, for individual missing data, a linear interpolation method is used to supplement the data and finally, a balanced panel observation set containing 300 data is formed. The sample data comes from the China Statistical Yearbook, China Energy Statistical Yearbook, China Environmental Statistical Yearbook, China Population and Employment Statistical Yearbook, China Industrial Statistical Yearbook, China Economic Census Yearbook, statistical yearbooks of various provinces (municipalities, districts) and the Wind database.

Descriptive statistics

The data selected in this paper are panel data from 30 provinces in mainland China from 2011 to 2021 (excluding Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan due to data availability and the Tibet Autonomous Region is excluded due to the large amount of missing data). There are a total of 330 observations and the descriptive statistics table for each variable is omitted. There are significant differences in the level of green finance development in each province, with the highest level of green finance development reaching 0.371 and the lowest only 0.100. Judging from the average value of 0.187, the development of green finance in most regions is at a relatively low level. Similarly, the intensity of coordinated emissions also shows significant regional differences.

The temporal and spatial evolution characteristics and dynamic evolution trends of green finance and coordinated emission intensity

Temporal evolution characteristics

This paper examines the time-evolutionary trend of green finance. From a national perspective, the level of green finance exhibited slight fluctuations from 2011 to 2021, yet demonstrated an overall upward trajectory, with an average annual growth rate of 5.39% (Fig. 2). In terms of regional analysis, the eastern region exhibited a notable increase in green finance levels, rising from 0.206 to 0.371, with an average annual growth rate of 5.52%. Similarly, the central region demonstrated a considerable rise in green finance levels, increasing from 0.107 to The green finance level in the eastern region increased from 0.206 to 0.371, with an average annual growth rate of 5.52%. In the central region, the green finance level increased from 0.107 to 0.192, with an average annual growth rate of 5.41%. In the western region, the green finance level increased from 0.100 to 0.172, with an average annual growth rate of 5.05%. In general, the eastern region exhibits the highest level of green finance and the most rapid growth, followed by the central region. In contrast, the western region displays the lowest level of green finance and the slowest growth. This can be attributed to the fact that the eastern region has a relatively high level of economic development, with a more comprehensive infrastructure and a more established traditional financial market. Furthermore, the green economy has emerged first in the East, creating greater demand and a market for green finance. These circumstances have fostered favorable conditions for the development of green finance in the eastern region. However, the central and western regions have a greater concentration of “three high and one low” industries. Despite the ongoing improvement in the level of green finance, the total amount remains low, indicating a significant potential for future growth.

The temporal trend of collaborative emission intensity. From the national perspective, the collaborative emission intensity maintained an upward trend from 2011 to 2021, with an average annual growth rate of 11.11%. Regionally, the emission intensity in the eastern region increased from 0.063 to 0.198, with an average annual growth rate of 11.05%; the collaborative emission intensity in the central region increased from 0.058 to 0.200, with an average annual growth rate of 11.95%; and the collaborative emission intensity in the western region increased from 0.058 to 0.170, with an average annual growth rate of 10.36%. Overall, before 2015, the total coordinated emissions intensity in the eastern region was the highest, after 2015, the central region overtook the eastern region and the coordinated emissions intensity in the western region was the lowest in most years. The probable reason for this is that the Environmental Protection Law promulgated in 2015 strengthened the restrictions on pollutant emissions imposed by environmental regulations and with the transformation and upgrading of the industrial structure and the increase in total economic output, the growth rate of collaborative emission intensity in the eastern region was slower than that in the central region. In the western region, pollutant emissions are low because the second industry and population density are relatively underdeveloped compared to the eastern and central regions, so the coordinated emission intensity has remained at a relatively low level39.

Spatial distribution characteristics

The regional differences and spatial-temporal evolution characteristics of the green finance development level and synergistic emission intensity in 2011, 2016 and 2021 were plotted using ArcGIS (Figs. 3 and 4) and the spatial standard deviation ellipse and center of gravity change trajectory of the two were plotted.

Characterizing the spatial evolution of green finance.

The level of green financial development is characterized by significant spatial heterogeneity, presenting a distribution pattern in which the eastern region is superior to the central and western regions. 2011, the level of green finance in the central and western regions was low and only Beijing in the eastern region had a level of green finance greater than 0.4; in 2016, the number of provinces and regions with a low level of green finance decreased significantly and the level of green finance in the country generally rose and the situation of green finance was significantly improved. Improved, the eastern coastal region has the most rapid growth rate, Shandong Province, Jiangsu Province, Zhejiang Province, Fujian Province, the green financial level of more than 0.2, spatially the eastern better than the central and western trend is more and more obvious; 2021, the national green financial level to further increase, especially in the central region of the green financial level of the upward trend of accelerated, but the central and western regions and the eastern region of the green financial level is still a large gap.

Overall, the level of green finance increased steadily from 2011 to 2021, especially from 2016 to 2021, when it showed a high rate of development, with a spatial distribution dominated by the east-west direction; the overall spatial evolution is characterized by the gradient of “from west to east and from north to south”.

Characterization of the spatial evolution of synergistic emission intensities.

The synergistic emission intensity shows a decreasing distribution pattern from east to west. 2011, the synergistic emission intensity level in the western region was low and only Shandong Province, Liaoning Province, Hebei Province and Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region had a synergistic emission level of 0.1; in 2016, the synergistic emission intensity of the whole country was generally increasing, with the fastest growth rate in the eastern region and the synergistic emission intensity of some provinces reached 0.2 or more; in 2021, the synergistic emission intensity of the whole country will further increase and the growth rate of the synergistic emission intensity of central region provinces will increase, with Henan Province, Anhui Province and Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region reaching 0.3 or more. In 2021, the synergistic emission intensity of the whole country will further increase and the growth rate of synergistic emission intensity of the central region provinces will increase, with the synergistic emission intensity of Henan Province, Anhui Province and Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region reaching above 0.3.

Overall, the synergistic emission intensity steadily increased from 2011 to 2021 and the provincial administrative regions with developed heavy industries generally have higher emission intensities. in 2021, although Beijing and Tianjin are surrounded by regions with high levels of emissions, their emission levels are controlled to be below 0.1, which may be related to the higher level of green finance in the region.

Spatial standard deviation ellipses and center of gravity migration trajectories for green finance and synergistic emission intensity

The location of the center of gravity can reflect the spatial distribution of provincial green finance level and coordinated emission intensity, while the standard deviation ellipse can portray the spatial dispersion of green finance and coordinated emission intensity. Based on ArcGIS, the migration and dispersion trends of the center of gravity of provincial green finance and coordinated emission intensity are analyzed from 2011 to 2021 (Fig. 5).

The change of the center of gravity of green finance from 2011 to 2021 ranges from (113.518°E, 33.733°N) to (113.718°E, 33.565°N), with a slight shift to the southeast but with a small amplitude, indicating that the spatial pattern of green finance development in China is relatively stable. From the ellipse data, the long half-axis of the ellipse increases by 58.417 km, the short half-axis decreases by 41.198 km and the area increases by 89.408 km², which indicates that in 2021, the discrete degree of China’s green financial development increases and the development of green financial level is more balanced.

From 2011 to 2021, the center of gravity of synergistic emission intensity shifts to the southeast from (112.762°E, 34.869°N) to (113.035°E, 34.823°N), indicating that the hotspot area of synergistic emission intensity tends to expand to the southeast. This is due to the faster economic development in the east and the high degree of industrialization leading to the increase of synergistic emission intensity. From the ellipse parameters, from 2011 to 2021, the long axis of the ellipse decreased by 68.524 km, the short axis decreased by 87.046 km and the area decreased by 510.459 km² and the changes of each parameter are relatively small and the spatial pattern of carbon emission is stable. It indicates that the intensity of synergistic emissions in China in 2021 is more spatially clustered.

Trends in dynamic evolution

This paper further adopts the spatial Markov chain to visualize the dynamic evolution of green finance and collaborative emission intensity in different provinces and the spatial effect under time accumulation, to explore the internal mobility and stability status of green finance and collaborative emission intensity in the whole country and the results are shown in Table 2. In this paper, following the principle of a similar number of provinces of each type, the level of green finance and synergistic emission intensity is divided into four types low level, lower level, higher level and high level according to the quartiles (0.25/0.5/0.75), corresponding to k = 1, 2, 3 and 4, respectively. if the type in the initial year is the same as the type in the next period, it indicates that the type of regional transfer is, the regional shift is “smooth”; if the regional type increases in the next period, the regional shift is “upward” and vice versa, the regional shift is “downward”.

The traditional Markov chain only considers the development of green finance level and the transfer of synergistic emission intensity in each province independently, ignoring the influence of neighboring provinces. However, through the Moran index, it is known that there is spatial autocorrelation between green finance level and synergistic emission intensity in China, so this paper introduces the spatial Markov chain to consider the dynamic transfer characteristics of green finance level and synergistic emission intensity under the condition of spatial lag. First, green finance and synergistic emission intensity as a whole exhibit spatial spillover effects and high-level provinces will have significant positive spillover effects on their neighboring provinces. Specifically, the probability of upward transfer of low-level types under green finance when they are neighbors with low-level types (11.8%) is smaller than the probability of upward transfer of low-level types in the traditional case (17.3%) and the probability of upward transfer when they are neighbors with high-level types is 50%. The probability of upward transfer of the low-level type under synergistic emission intensity (28.6%) is greater than the probability of upward transfer of the low-level type in the traditional case (18.7%) when the low-level type is neighboring the low-level type, the probability of upward transfer when the high-level type is neighboring the high-level type is 15.4% and there is a 2% probability of upgrading to the higher level, which shows the leapfrog development of low-lower-higher. Next, the most stable is the high-level type, with the probability of the high-level type of green finance and synergistic emissions intensity remaining unchanged from its original state throughout the period reaching essentially 100%.

Spatial econometric analysis of green finance on synergistic emission intensity

Spatial benchmark regression

To incorporate the “spatial” factor into the analytical framework, the spatial correlation of synergistic emission intensity is examined in this paper before the causal identification. As shown in Tables 3 and 4, the global Moran’s I index of synergistic emission intensity from 2010 to 2021 passed the significance test in the spatial economic distance matrix, spatial geographic distance matrix and geographic adjacency matrix and all of them are positive, indicating that there is a significant spatial clustering of synergistic emission intensity. On the whole, the value of Moran’s I index of synergistic emission intensity shows a fluctuating upward trend, indicating that the spatial agglomeration of the two is gradually increasing.

This paper examines various forms of spatial panel econometric models (refer to Table 5). Firstly, the LM test confirms that the spatial economic distance matrix, the spatial geographic distance matrix and the geographic neighborhood matrix are all appropriate for investigating the causal relationship between green finance and synergistic emission intensities. Secondly, the results from the Wald and LR tests indicate that all three types of spatial weight matrices pass the significance test, demonstrating that the spatial panel Durbin model (SPDM) cannot be simplified into either the spatial panel error model (SPEM) or the spatial panel lag model (SPLM). Lastly, the Hausman test reveals that the fixed effects model is superior to the random effects model, with the joint significance of both spatial and time fixed effects being significant at least at the 5% level. As a result, this paper employs the time-space dual fixed effects SPDM model for parameter estimation.

According to the first test results in Table 6, column (1) of Table 6 shows that the coefficient of the quadratic term of green finance is negative and passes the significance test of 1%, which indicates that there is an inverted “U”-shaped curve relationship between green finance and synergistic emission intensity, plus the “U-test” test passes the significance test of 1%. The “U-test” test passed the 1% significance test, that is, the inflection point of the inverted “U” curve is within the range of values of the effective samples of green finance, which once again confirms the non-linear relationship between green finance and synergistic emission intensity. Secondly, columns (2) to (4), which take into account the spatial effect, show that green finance and synergistic emission intensity still present a significant inverted “U” curve relationship and the coefficients of the quadratic terms of green finance and its spatial spillover term have passed the significance test. Thirdly, the spatial autoregressive coefficient of synergistic emission intensity, Spatial rho, is significantly positive at the 5% level, indicating that the spatial correlation characteristic of synergistic emission intensity is significantly positive in the spatial dimension.

Analysis of spatial effects

In order to better reflect the spatial spillover effect of green finance on synergistic emission intensity, the effect of green finance on synergistic emission intensity in the spatial Durbin model is decomposed into direct and indirect effects with the help of the partial differentiation method (Table 7). Based on the estimation results of the spatial economic distance matrix model, the direct effect shows that the coefficient of the quadratic term of green finance is −0.499 and passes the test at 1% significance level, indicating that the green finance has an inverted “U”-shaped nonlinear effect on synergistic emission intensity, i.e., the green finance exceeds a certain threshold, the effect of green finance on synergistic emission intensity increases from promoting to increase and the effect on synergistic emission intensity decreases from promoting to increasing to increasing. That is, after green finance exceeds a certain threshold, the influence on synergistic emission intensity changes from an increasing effect to an inhibiting effect. The reasons for this are, firstly, in the early stage of green finance development, regulatory policies, industry standards and certification systems may still be gradually established and perfected, which may lead to regulatory loopholes in the implementation of some projects, thus affecting the actual effect of pollution reduction; secondly, green finance in the early stage may prioritize the support of large-scale projects that are easy to obtain financial and policy support and these projects may not be the most direct effect of pollution reduction; secondly, green finance may prioritize the support of large-scale projects that are easy to obtain financial and policy support and these projects may not be the most direct effect of pollution reduction. the most direct effect of pollution reduction; finally, the initial development of green finance may lead to the expansion of related industries, which may increase the consumption of energy and resources in the short term, thus increasing pollution emissions to a certain extent.

The development of green finance, can guide the flow of funds to low-carbon, low-pollution and environmentally friendly enterprises and projects through green credit and green securities and increase the financing cost of the “two surplus and one high” industries, thus reducing high carbon emissions and environmental pollution and helping to promote projects in the fields of clean energy, energy efficiency improvement, recycling economy and sustainable development; secondly, green finance can improve the corporate information disclosure mechanism and provide data on the environmental benefits and carbon emissions of green projects and enterprises, thus helping investors and financial institutions to better assess the risks and returns of green investment. Secondly, green finance can improve the enterprise information disclosure mechanism and provide data on the environmental benefits and carbon emissions of green projects and enterprises, which can help investors and financial institutions better assess the risks and returns of green investment, thus promoting the financing and development of low-carbon projects. In summary, as green finance develops in-depth, it can curb synergistic emission intensity and promote synergistic effects of pollution reduction and carbon reduction through financial guidance, financial innovation and information disclosure. This synergy can help realize the dual goals of environmental protection and sustainable economic development. Green finance changes from promotion to suppression of synergistic emission intensity. However, during the sample study period, green finance had a mainly positive impact on synergistic emission intensity and the level of green finance in the vast majority of provinces and regions has not yet crossed the inflection point and is still on the left side of the inverted “U” curve23.

The spatial spillover effect shows that the coefficient of the quadratic term of green finance is −0.711 and passes the significance test of 1%, indicating that the spillover effect of green finance on synergistic emission intensity is also characterized by an inverted “U” shape. The reason is that at the early stage of green finance development, to achieve the performance related to pollution reduction and carbon reduction, if the green finance of a province is more developed, it will have a “siphon” effect on the green industry of neighboring provinces, thus stimulating the neighboring provinces to increase the level of coordinated emissions. On the other hand, green financial products reduce the financing costs of environmentally friendly enterprises while increasing the financing costs of polluting enterprises. In anticipation of the negative impacts of relevant policies, polluting enterprises will move from provinces with higher levels of green financial development to neighboring provinces with lower levels of green financial development, increasing pollutant and carbon emissions in neighboring provinces, thus further stimulating the synergistic emission intensity of neighboring provinces. emissions intensity. However, when the level of green finance reaches the threshold, continuing to increase the level of green finance will suppress the level of synergistic emissions. With the increase of green finance level, the provinces with higher economic development levels and stronger government support for the synergistic effect of pollution reduction and carbon reduction can create a good economic and policy environment for neighboring regions to suppress the synergistic emission intensity and can provide advanced experience and demonstration samples for the neighboring provinces through the inter-regional exchanges and references, so as to effectively drive the neighboring provinces to suppress the synergistic emission intensity and improve the synergistic effect of pollution reduction and carbon reduction. Synergizing Efficiency.

Analysis of spatial heterogeneity

By analyzing the characteristics of the spatial and temporal evolution of green finance and synergistic emission intensity, it can be found that both the level of green finance and synergistic emission intensity in China’s regions show obvious spatial heterogeneity. In order to further explore the relationship between green finance and synergistic emission intensity in different regions, this paper constructs a regression model for the three major regions of East, Central and West for analysis. From the results of the spatial heterogeneity test in Table 8, it can be concluded that the direct and indirect effects of green finance on synergistic emission intensity in the western and central regions show an inverted “U”-shaped change and the quadratic coefficients of the coefficients are negative and pass the significance test of 1%, while in the eastern region, the significance of the coefficients does not pass the significance test. The possible reasons are, on the one hand, the optimization effect of industrial structure in the eastern region is more prominent, effectively curbing the scale expansion of high-energy-consuming industries and continuously promoting the development of clean and low-carbon industries; on the other hand, the eastern region has already made great progress in the innovation and application of green technology, which can reduce the impact of green finance on the synergistic emission intensity; while the central and western regions are rich in solar energy, hydroelectricity, wind and other clean energy sources, which can be used for the green finance and green emission intensity40. The central and western regions are rich in clean energy such as solar energy, water energy and wind energy, which can provide better natural conditions for green finance and green technology innovation promote the upgrading of regional industrial structure and significantly inhibit the synergistic emission intensity when the level of green finance develops to a certain extent. Therefore, the inverted “U” shape effect of green finance on synergistic emission intensity is more obvious in the central and western regions.

Endogeneity test

In this paper, the instrumental variable method (IV) and dynamic spatial panel Durbin model (DSPDM) are used to mitigate the potential endogeneity between green finance Endogeneity test e and synergistic emission intensity, respectively and the results are shown in Table 9.

The result of the unidentifiable test is the Kleibergen-Paap rk LM statistic and the value in the corresponding parentheses corresponds to the p-value of the test statistic; the result of the weak instrumental variable test is the Kleibergen-Paap rk Wald F statistic and the value in the corresponding parentheses corresponds to the Stock-Yogo test at the 10% statistical level. critical value; the result of the overidentification test is the Hansen J statistic, with a result of 0, exactly identified.

Robustness tests

To verify the reliability of the regression results, this paper adopts the following ways to conduct the robustness test in order: first, replace the spatial weight matrix and adopt the economic-geographical nested matrix to conduct the robustness test. Second, government support and trade openness are added as control variables to observe the changes in the coefficients and significance of the core explanatory variables in the model. Third, the pilot provinces of green finance are excluded; there are differences between the pilot provinces and other provinces in terms of support policies, etc., which are excluded from the total sample to exclude the possible influence of outliers. Fourth, adjust the estimation sample, China’s economy began to enter the “new normal” in 2012, so to reflect the consistency of the balanced development of the economic environment and to consider the impact of the impact of the public health events in 2019, the sample interval is shortened to 2012–2019 and the benchmark regression is conducted again. Ultimately, the results of different robustness tests show that the direct impact and spatial spillover effects of green finance on synergistic emission intensity remain relatively robust (Table 10).

Conclusions and recommendations

Conclusions

This paper utilizes the entropy value method to construct indicators for the level of green finance development in 30 provinces in mainland China from 2011 to 2021. Further, this paper tests the spatial spillover effect of green finance on synergistic emission intensity using the super-efficient SBM model with non-expected output. The main conclusions of this paper are as follows: (1) The discrete degree of the development of green finance level in the country increases and the development tends to be balanced; while the synergistic emission intensity has a more spatially clustered trend. (2) There is an inverted “U” curve relationship between green finance and synergistic emission intensity in terms of direct effect and spatial spillover effect. (3) Heterogeneity analysis shows that the impact of green finance on synergistic emission intensity is more significant in the central and western regions.

Policy recommendations

-

1.

To address the unique challenges faced by the central and western regions, policymakers should consider implementing targeted green finance incentives. These could include subsidized green loans, green credit lines, and low-interest loans for sustainable businesses. In addition, technology support programs should be introduced to facilitate the adoption of green technologies, particularly in energy-intensive industries such as manufacturing and mining. Moreover, creating market-driven mechanisms, such as green bonds and carbon markets, can stimulate private sector investment and enhance the region’s transition to green growth. Additionally, cross-regional green finance cooperation should be promoted to share resources and expertise, helping less developed regions adopt best practices from more developed regions. This could include joint green investment initiatives or green technology partnerships between regions.

-

2.

One potential pathway for implementing green finance policies in the central and western regions is to leverage green bonds and green credit programs to finance sustainable projects. These financial instruments could be used to fund renewable energy projects, green infrastructure, and energy efficiency improvements. To enhance spatial coordination and ensure complementary development, green finance initiatives should be aligned across regions. This could involve the creation of regional green finance hubs that serve as coordination points for knowledge sharing, technical assistance, and financial collaboration. A regional policy coordination framework should also be established to ensure that green finance initiatives in more developed areas do not inadvertently overshadow or outcompete those in less developed regions. This would support more balanced and effective green growth across regions.

-

3.

To ensure the long-term sustainability of green finance policies, policymakers should consider the establishment of risk compensation mechanisms to mitigate potential risks for investors. This can include providing government-backed guarantees or insurance for green investments, particularly in regions with higher perceived risks. Additionally, creating a stable policy environment through long-term green finance frameworks will encourage sustainable investments and help strike a balance between short-term economic needs and long-term environmental goals. Moreover, to address spatial spillover effects, cross-regional governance tools should be established to enhance cooperation and ensure that the positive impacts of green finance initiatives in one region are not undermined by policy misalignment in neighboring regions.

Research limitations and future prospects

Research limitations

While this study offers valuable insights into the relationship between green finance and emission reduction, there are several limitations that must be acknowledged:

-

1.

Geographic and Sectoral Focus. This research primarily examines data from 30 provinces in China, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other countries or regions with different economic structures, industrial configurations, and policy environments. Future research could expand the analysis to include international comparisons or specific sectors to provide a broader understanding of the dynamics between green finance and emission reduction.

-

2.

Data Availability and Quality. The study relies on data from publicly available sources, such as national and provincial statistics, which may have varying levels of accuracy and completeness. In particular, there could be inconsistencies in the reporting of green finance activities across regions. Future studies would benefit from more granular, region-specific data and enhanced transparency in reporting green finance initiatives.

-

3.

Non-Linearity and Threshold Effects. This study explores the inverted "U" curve relationship between green finance and synergistic emission intensity, but further research could more thoroughly investigate the precise mechanisms behind the threshold effect. Understanding the specific factors that influence the transition from promoting to suppressing emission intensity could provide deeper insights into how green finance policies can be more effectively tailored to different stages of development.

-

4.

Cross-Regional Spillover Effects. While this study highlights the importance of spatial spillovers, there is a need for a more detailed examination of how green finance policies in one region impact neighboring regions. Future research could explore these spillovers in greater depth, examining not only the economic but also the social and environmental dimensions of spillover effects across regions.

Future prospects

Looking ahead, the role of green finance in achieving sustainable development goals will continue to evolve. Future research could explore the integration of green finance with emerging technologies such as digital finance, green fintech, and artificial intelligence, which have the potential to further enhance emission reduction efforts. Additionally, the growing importance of global environmental collaboration and the need for cross-border green finance initiatives present exciting opportunities for future research into how international green finance flows can help address global environmental challenges. In summary, while this study provides valuable insights into the spatial and dynamic effects of green finance on emission reduction, addressing these limitations and exploring future directions will enhance our understanding of the complex relationship between green finance, policy, and environmental sustainability.

Data availability

All the raw data are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Change history

26 August 2025

This article has been retracted. Please see the Retraction Notice for more detail: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16392-9

References

MA, X. F., HUANG, G. & CAO, J. J The significant roles of anthropogenic aerosols on surface temperature under carbon neutrality. Sci. Bull. 67, 470–473 (2022).

BAUER, P., STEVENS, B. & HAZELEGER, W. A digital twin of Earth for the green transition. Nat. Clim. Change. 11, 80–83 (2021).

SHAN, Y. L. et al. City-level emission peak and drivers in China. Sci. Bull. 67, 1910–1920 (2022).

Hu, Q. et al. Can government-led urban expansion simultaneously alleviate pollution and carbon emissions? Staggered difference-in-differences evidence from Chinese firms. Economic Anal. Policy 84, 1–25 (2024).

Ren, X. et al. Natural gas and the battle of carbon emissions: Interpreting the Spatial effects of provincial carbon emissions in China. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance. 97, 103835 (2025).

Xian, B., Xu, Y., Chen, W., Wang, Y. & Qiu, L. Co-benefits of policies to reduce air pollution and carbon emissions in China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 104, 107301 (2024).

WEN, L. & SONG, Q. Simulation study on carbon emission of China’s freight system under the target of carbon peaking. Sci. Total Environ. 812 (2022).

DU, W. & LI, M. Assessing the impact of environmental regulation on pollution abatement and collaborative emissions reduction: Micro-evidence from Chinese industrial enterprises. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 82 (2020).

MUGANYI, T. YAN, L. N., SUN, H. P. Green finance, fintech and environmental protection: evidence from China. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 7 (2021).

AL MAMUN, M. BOUBAKER, S., NGUYEN, D. K. Green finance and decarbonization: evidence from around the world. Finance Res. Lett. 46 (2022).

ALLAMEH, S. M. Antecedents and consequences of intellectual capital: The role of social capital, knowledge sharing and innovation. J. Intellect. Capital. 19, 858–874 (2018).

FELíCIO, J. A., COUTO, E. & CAIADO, J Human capital, social capital and organizational performance. Manag. Decis. 52, 350–364 (2014).

Sun, H., Liu, J. & Zhang, L. Differential Game Analysis of Carbon Emission Reduction Effect and Price Strategy Considering Government Intervention and Manufacturer Competition. Managerial and Decision Economics. (2024).

Sun, X. et al. Time-varying impact of information and communication technology on carbon emissions. Energy Econ. 118, 106492 (2023).

SHI, Y. R. & YANG, B. How digital finance and green finance can synergize to improve urban energy use efficiency? New evidence from China. Energy Strategy Rev. 55 (2024).

ZHANG, G. X., WANG, Y. T. & ZHANG, Z. H. SU, B. Can green finance policy promote green innovation in cities? Evidence from pilot zones for green finance reform and innovation in China. J. Environ. Manage. 370 (2024).

ZHOU, P., HUANG, X. Q. & SONG, F. M. The deterrent effect of environmental judicature on firms’ pollution emissions: Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. China Econ. Rev. 88 (2024).

CAGLAR, A. E., DASTAN, M., AHMED, Z., MERT, M. & AVCI, S. B The Synergy of Renewable Energy Consumption, Green Technology and Environmental Quality: Designing Sustainable Development Goals Policies (Natural Resources Forum, 2024).

XU, Y. G. & DING, Z. Sustainable growth unveiled: exploring the nexus of green finance and high-quality economic development in China. Front. Environ. Sci. 12 (2024).

HAN, J. & GAO, H. Green finance, social inclusion and sustainable economic growth in OECD member countries. Humanit. Social Sci. Commun. 11 (2024).

KHURSHID, A., KHAN, K. & CIFUENTES-FAURA, J. 2030 Agenda of sustainable transport: can current progress lead towards carbon neutrality? Transp. Res. Part. D-Transport Environ. 122 (2023).

RAN, C. & ZHANG, Y. The driving force of carbon emissions reduction in China: does green finance work. J. Clean. Prod. 421 (2023).

YU, H., WEI, W., LI, J. & LI, Y. The impact of green digital finance on energy resources and climate change mitigation in carbon neutrality: case of 60 economies. Resour. Policy 79 (2022).

DE DEUS, J. L., CROCCO, M. & SILVA, F. F. The green transition in emerging economies: Green bond issuance in Brazil and China. Clim. Policy 22, 1252–1265 (2022).

WANG, S. G., SUN, L. & IQBAL, S. Green financing role on renewable energy dependence and energy transition in E7 economies. Renew. Energy. 200, 1561–1572 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. Does green finance facilitate firms in achieving corporate social responsibility goals? Economic research-Ekonomska Istraživanja 35(1), 5400–5419 (2022).

Zhang, L. et al. Do green finance and hi-tech innovation facilitate sustainable development? Evidence from the Yangtze river economic belt. Econo Anal. Policy. 81, 1430–1442 (2024).

Zhang, D. et al. The impact of firm’s ESG performance on the skill premium: evidence from China’s green finance reform pilot zone. Int. Rev. Financ Anal. 93, 103213 (2024).

CHEN, X., WANG, M. E. N. G. Q., LIU, K. & SHEN, Y. W. Spatial patterns and evolution trend of coupling coordination of pollution reduction and carbon reduction along the yellow river basin. China Ecol. Indic. 154 (2023).

WANG, Y., ZHANG, X., ZHU, L. & WANG, X. ZHOU, L., YU, X. Synergetic effect evaluation of pollution and carbon emissions in an industrial park: an environmental impact perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 467 (2024).

ZHANG, B. & WANG, N. YAN, Z., SUN, C. Does a mandatory cleaner production audit have a synergistic effect on reducing pollution and carbon emissions? Energy Policy 182 (2023).

WANG, H., DONG, G. U. K. & F., SUN, H Does the low carbon City pilot policy achieve the synergistic effect of pollution and carbon reduction? Energy Environ. 35, 569–596 (2024a).

HIRSCH, J. A., WINTERS, M., CLARKE, P. & MCKAY, H. Generating GPS activity spaces that shed light upon the mobility habits of older adults: a descriptive analysis. Int. J. Health Geogr. 13 (2014).

LEMEY, P., RAMBAUT, A., DRUMMOND, A. J. & SUCHARD, M. A Bayesian phylogeography finds its roots. PLoS Comput. Biol. 5, e1000520–e1000520 (2009).

BIVAND, R. S. & WONG, D. W. S Comparing implementations of global and local indicators of Spatial association. Test 27, 716–748 (2018).

LAEPPLE, D. & KELLEY, H. Spatial dependence in the adoption of organic drystock farming in Ireland. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 42, 315–337 (2015).

DAVIS, S. J. & CALDEIRA, K. Consumption-based accounting of CO2 emissions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 5687–5692 (2010).

ZHANG, Y. J., LIU, Z., ZHANG, H. & TAN, T.-D The impact of economic growth, industrial structure and urbanization on carbon emission intensity in China. Nat. Hazards. 73, 579–595 (2014).

Feng, L. et al. CO2 emissions are first aggravated and then alleviated with economic growth in China: A new multidimensional EKC analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut R 30(13), 37516–37534 (2023).

Yu, M. et al. Does green finance improve energy efficiency? New evidence from developing and developed economies. Econ. Change Restruct., 1–25. (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W.: Project administration, Writing—review & editing, Writing—original draft, investigation. Z.C.: Validation, Conceptualization, Visualization. Z.W.: Project administration, Supervision, Writing—review & editing, Resources. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article has been retracted. Please see the retraction notice for more detail: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16392-9"

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Chen, Z. & Wang, Z. RETRACTED ARTICLE: Inverted U-shaped pattern of green finance influencing the synergistic effect of pollution and carbon reduction. Sci Rep 15, 12468 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97740-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97740-7