Abstract

Patients who have experienced an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) are at increased risk of developing depression or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the long term. However, whether these psychiatric comorbidities are preceded by early psychological symptoms appearing within the first days after AMI remains unclear. This study provides the identification of early psychological symptoms after AMI and evaluates their predictive value for the subsequent development of AMI-related depression and PTSD. A cohort of 129 AMI patients underwent assessments for early psychological symptoms (depressive symptoms, anxiety, intrusions, avoidance, and hyperarousal) within the first days after AMI using the psychometric questionnaires HAMD-17, HADS, and IES-R. Patients with clinically significant depression or PTSD within the year prior to AMI were excluded based on a clinical assessment and a review of medical records conducted by an experienced consultation-liaison psychiatrist. At a six-month follow-up, long-term depression and PTSD were diagnosed based on the HAMD-17 and CAPS-5, with PTSD assessments explicitly keyed to AMI. Stepwise multiple regression analyses identified early psychological predictors of depression and PTSD following AMI. Five days after AMI, 55 (43%) out of 129 participants exhibited early depressive symptoms, which were strongly associated with hyperarousal, intrusions, avoidance, and anxiety symptoms. Women, individuals living alone, and those with a history of psychiatric illness or treatment were at increased risk of developing these early psychological symptoms. In 80% of these patients, early depressive symptoms progressed in the long term to clinically significant depression, with 49% also developing comorbid PTSD. PTSD without clinically significant depression occurred only in subclinical form. Predictors for AMI-induced depression in the long term included early depressive symptoms, hyperarousal, and living in a solitary arrangement. Predictors for comorbid PTSD included early avoidance symptoms and solitary living arrangements. In this study, women, individuals living alone, and those with a history of psychiatric illness were particularly affected by early psychological symptoms such as depressive symptoms, hyperarousal and avoidance behaviour within the first days after an AMI. These early psychological symptoms emerging within the first days after AMI and solitary living arrangements predict the development of AMI-related depression and PTSD in the long term. These findings suggest that a comprehensive biopsychosocial post-AMI treatment should incorporate an early psychological screening within the first days after AMI to identify high-risk patients at an early stage and to prevent AMI-related depression and PTSD in the long term. The observed impact of gender, living in a solitary arrangement and a history of psychiatric morbidity highlights the need for personalized care plans that also address preexisting mental health conditions and incorporate gender-specific psychosocial interventions. High-risk patients identified in this context may benefit from early admission to community-based psychosocial services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute myocardial infarction-induced mental disorders

Cardiovascular and mental health implications of AMI

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI), caused by a sudden blockage of blood flow to the heart muscle, remains a leading cause of illness and mortality worldwide1. Advances in treatment, particularly primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), have significantly improved survival rates2. However, beyond its cardiovascular effects, AMI can profoundly impact mental health, particularly through depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), both of which can severely reduce quality of life3,4. Studies indicate that up to 20% of AMI patients develop severe depression, with even higher rates of mild to moderate depression5. Additionally, many survivors experience anxiety6,7 and PTSD-like symptoms, including intrusive thoughts, hyperarousal, and avoidance behaviors, with prevalence estimates ranging from 12 to 25%8,9,10,11,12,13,14.

Understanding AMI-induced PTSD

The Enduring Somatic Threat (EST) model proposed by Edmondson offers a framework for understanding AMI-induced PTSD. Unlike PTSD resulting from external traumatic events, AMI-related PTSD arises from a persistent internal threat perception—the fear of another cardiac event—which can lead to sustained hyperarousal and avoidance behaviors14. This ongoing distress may contribute to long-term psychological burden and adverse cardiovascular outcomes15. Moreover, PTSD following AMI has been associated with an increased risk of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) and mortality15. Similarly, Birk et al. emphasize that intrusive thoughts about cardiac risk are particularly common among AMI patients with PTSD symptoms, reinforcing the importance of early psychological screening16.

However, the development of AMI-related depression and PTSD seems to be influenced by both biological and psychosocial factors. While psychological stressors—such as physical limitations and fear of recurrence—play a significant role, growing evidence also points to the impact of neurobiological mechanisms. Dysregulation of the HPA axis, chronic hypercortisolism, dopamine depletion, and systemic inflammation can impair stress regulation and emotional processing, increasing vulnerability to depression17,18,19,20.

Clinical relevance and underdiagnosis

Despite their significant impact, mental health disorders following AMI are often underestimated in clinical practice, leading to inadequate management21,22,23,24,25. Depression and PTSD can interfere with adherence to necessary lifestyle changes, increasing the risks of rehospitalization and cardiac mortality to a level comparable with traditional cardiovascular risk factors8,10,22,23,24,25.

Given the substantial psychosocial burden of AMI-induced mental health conditions26, early recognition of psychological distress should be a priority in both research and clinical practice27. However, despite growing awareness of the biopsychosocial aspects of AMI recovery, depression and PTSD frequently remain undiagnosed. Importantly, early warning signs of long-term mental health complications are not yet well understood.

The importance of early detection

Clinical observations suggest that many AMI patients exhibit early depressive symptoms within days of the event, creating challenges for timely diagnosis, as these symptoms do not fit the established time criteria for major depression in the ICD-10 or DSM-5. However, emerging evidence suggests that early depressive reactions may have prognostic value for long-term mental health and mortality, highlighting the need for improved screening strategies28. Additionally, early depressive symptoms are often accompanied by other psychiatric symptoms, reinforcing the necessity of a clinically applicable screening tool to identify at-risk patients early.

In summary, the relationship between cardiovascular and mental health requires a comprehensive perspective to fully understand the long-term consequences of AMI. This study aims to highlight the prevalence of depression and PTSD after AMI while emphasizing the importance of early detection and intervention to improve patient outcomes and enhance biopsychosocial care.

Objectives

The objectives of this study are as follows:

-

1.

Investigate the frequency of early psychological symptoms: Examine and quantify the prevalence of early depressive symptoms as well as symptoms of anxiety, avoidance, hyperarousal, and intrusions within the initial days following AMI.

-

2.

Evaluate associations with sociodemographic and clinical parameters: Assess the potential associations between early psychological symptoms and various factors, including sociodemographic characteristics, acute cardiac and somatic parameters at the time of AMI, and a history of psychiatric disorders.

-

3.

Assess predictive value for long-term mental health outcomes: Evaluate the predictive value of early psychiatric symptoms, alongside sociodemographic, cardiological, and other somatic parameters, as well as AMI treatment-related factors, for the development of AMI-induced depression and PTSD over the long term.

-

4.

Integrate a biopsychosocial perspective: Incorporate a biopsychosocial perspective that integrates sociodemographic, clinical, and psychiatric factors to enhance our understanding of the complex interplay involved in AMI-related depression and PTSD.

By addressing these objectives, the study aims to contribute valuable insights into the early manifestations, potential risk factors, and predictive indicators of mental health outcomes following AMI, ultimately striving toward the development of a holistic model for the understanding and management of AMI-related depression and PTSD.

Materials and methods

Subjects and recruitment

Study population

All participants in this study were recruited from inpatients diagnosed with AMI who were admitted to the Division of Cardiology at the Medical University of Graz, Austria, between 2017 and 2018.

Recruitment and consent

An experienced consultation-liaison psychiatrist (A.B.) contacted 142 AMI patients one day after their inpatient admission, seeking their participation in the study. Patients were approached consecutively during the recruitment period to ensure a representative sample. Simultaneously, preexisting psychiatric morbidity was identified during this initial contact.

Out of the approached patients, 11 declined participation, and two patients passed away during the study period. Thus, 129 AMI patients formed the final study sample. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Exclusion criteria

Patients presenting with dementia or delirium during clinical examination, as well as those with a history of clinically significant depression or PTSD within the year prior to AMI, were excluded from participation.

Ethical considerations

The study adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committee of the Medical University of Graz (Protocol-No: 28–126 Ex 15/16). Data protection measures complied with Austrian law. Participants provided written informed consent before inclusion in the study.

Sociodemographic data

Sociodemographic data were collected, including age, sex, education level, employment status, and marital status.

Psychiatric assessments

All patients underwent a comprehensive psychiatric assessment conducted by an experienced consultation-liaison psychiatrist (A.B.). This evaluation included a structured assessment using the HAMD-17 and CAPS-5 to ensure a thorough and standardized assessment of depressive symptoms and PTSD. This combined approach allowed for both clinical expertise and objective measurement, enhancing the reliability of the diagnostic process.

Early depressive symptoms and depression in the long-term

Participants were assessed for depressive symptoms using the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD-17)29,30 on two occasions: Five days after AMI and again 6 months later. The HAMD-17, a 17-item observer rating scale, measures the severity of depressive symptomatology. Scoring recommendations by Zimmerman et al.31 were used to classify depression severity, with scores categorized as follows: no depression (0–7), mild depression (8–16), and moderate depression (17–23).

Early symptoms of intrusions, avoidance, and hyperarousal

5 days after AMI, participants completed the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R)32, a well-validated 22-item self-assessment rating scale designed to evaluate symptoms of intrusions, avoidance, and hyperarousal.

Early symptoms of anxiety

Anxiety symptoms were assessed using the anxiety subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-A)33. This well-validated seven-item tool, specifically designed to measure anxiety symptoms, was administered 5 days after AMI.

PTSD

A structured interview based on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5)34,35 was conducted 5 days after AMI to exclude preexisting PTSD. Subsequent assessments were conducted six months after AMI to evaluate PTSD symptomatology, with all PTSD measures explicitly keyed to the AMI event. The CAPS-5 is a 30-item structured interview that assesses PTSD based on DSM-5 criteria, including.

-

Criterion A: Severe or life-threatening traumatic event (AMI in this study).

-

Criterion B: Reexperiencing symptoms, intrusions, and flashbacks.

-

Criterion C: Avoidance symptoms.

-

Criterion D: Negative alterations in cognition and mood.

-

Criterion E: Hyperarousal.

-

Criterion F: Significant disturbance lasting at least one month.

-

Criterion G: Disturbance causing significant impairment.

For a diagnosis of full PTSD, patients must fulfil criteria A, F, and G and exhibit at least one criterion B symptom, at least one criterion C symptom, at least two criterion D symptoms, and at least two criterion E symptoms (National Center of PTSD, 2020). Subsyndromal PTSD symptomatology was diagnosed when one or two criteria from B-E were missing36.

Clinical data collection

A comprehensive clinical data collection aimed to provide a thorough understanding of the participants’ somatic health status, cardiac history, and psychiatric background.

Anthropometry

Height [m] and weight [kg] measurements were collected to establish the anthropometric profiles of the participants.

Type of myocardial infarction (AMI)

AMI was categorized into ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) or non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI).

Electrocardiogram (ECG) patterns

ECG recorded frequency, presence of atrial fibrillation, and other relevant ECG indicators.

AMI-related cardiac biomarkers

Troponin T levels were measured to assess myocardial damage. AMI-associated cardiogenic shock and instances of resuscitation were documented.

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)-related parameters

-

Indication for PCI: STEMI, NSTEMI, PCI following successful lysis, or lysis failure.

-

Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) Grade Flow: Assessed before and after PCI on a scale from 0 to 3 (0: no perfusion, 3: normal flow)37.

-

PCI characteristics: Documented whether single or multivessel PCI was performed and recorded maximal stent diameter and length [mm].

Killip class

Utilized for post-AMI mortality risk stratification, with classes I-IV38: I: No clinical signs of heart failure. II: Presence of rales or crackles in the lungs, S3 heartbeat, and elevated jugular venous pressure. III: Acute pulmonary edema. IV: Cardiogenic shock or hypotension (systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg).

In-hospital adverse AMI-related outcome

Outcomes during the hospital stay were monitored and recorded, including mortality, major bleeding incidents, reinfarction, and decreased left ventricular ejection fraction (%).

Preexisting cardiac risk factors

An assessment of preexisting conditions that could contribute to cardiac risk included Nicotine abuse, known coronary artery disease, peripheral arterial occlusive disease, diabetes mellitus (IDDM), hypertension, hyperlipidemia, positive family history of myocardial infarction, history of myocardial infarction, severe liver disease, history of transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke.

Psychiatric morbidity before AMI

Patients’ psychiatric history was investigated, encompassing a history of mental illness before AMI, current psychopharmacological treatment, and substance abuse history.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics were employed to outline the characteristics of patients with and without early depressive symptoms five days after AMI, patients with or without depression in the long-term, and depressive patients in the long-term with or without comorbid PTSD six months after AMI. Means, standard deviations (SD), medians, and ranges were presented for continuous variables, providing a comprehensive overview of the patient groups.

Categorical and continuous variable analysis

Categorical variables were analyzed using χ2 tests or Fisher’s exact tests, while continuous variables were subjected to Student’s t-tests and Pearson’s correlation coefficients. Nonparametric tests, including Wilcoxon signed-rank tests or Mann-Whitney U tests, were applied when data exhibited skewness. An alpha adjustment (Bonferroni) was considered for multiple comparisons to maintain statistical rigor.

Stepwise multiple regression analyses

To assess the predictive value of early psychological symptoms alongside other clinical or anamnestic data, a stepwise (forward) multiple regression approach was employed. The variables considered in these analyses encompassed scores from psychometric questionnaires [HAMD-17, HADS-A, IES-R (hyperarousal, intrusion, and avoidance)] as well as somatic parameters [such as acute cardiac situation at the time of AMI (type of myocardial infarction, ECG patterns, troponin T, cardiogenic shock, and resuscitation), PCI parameters (indication for PCI and TIMI flow), in-hospital outcome, preexisting cardiac risk factors], and history of mental illness before AMI, and current psychopharmacological treatment. A significance level of 0.05 was required for inclusion in the prediction equations.

Statistical software

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Descriptive overview of the study population

Sociodemographic characteristics

In this study, all 129 participants were of Caucasian ethnicity, comprising 83% males (107/129) and 17% females (22/129). The mean age for the entire cohort was 59.9 years (SD: ±11.7).

AMI-related characteristics, PCI, and outcome

All participants presented elevated troponin T levels upon hospital admission for AMI and underwent PCI following acute admission to the Division of Cardiology. Indications for PCI included STEMI in 64% (82/129) and NSTEMI in 36% (47/129) of patients. Two patients (2/129, 2%) had undergone lysis previously (one successful lysis and one lysis failure). Coronary blood flow, assessed by the TIMI flow score, showed that before PCI, 81% (104/129) had a score of 0 or 1, 15% (20/129) had a score of 2, and 4% (5/129) had a score of 3. After PCI, 4% (5/129) had a score of 0 or 1, 7% (9/129) had a score of 2, and 89% (115/129) regained normal flow (TIMI flow score of 3). In terms of outcomes, 2% (2/129) experienced reinfarction during hospitalization, and 2% (2/129) died before the 6-month follow-up. No instances of stroke or major bleeding were observed.

History of mental illness before In-hospital treatment

Upon a clinical psychiatric interview and a review of medical history at inpatient admission, specific preexisting psychiatric diagnoses were identified. These included a history of depression (7%, 9/129), burnout (1.6%, 2/129), alcohol dependence (4.7%, 6/129), benzodiazepine abuse (0.8%, 1/129), panic disorder (2.3%, 3/129), and borderline personality disorder (0.8%, 1/129).

Early psychological symptoms

Early depressive symptoms within the first days after AMI

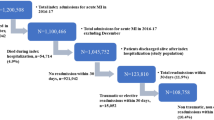

Five days post-AMI, 43% (55/129) of patients surpassed the HAMD-17 cutoff, as suggested by Zimmermann et al. (2013), signifying early depressive symptoms (see Fig. 1). Predominant symptoms included psychophysical exhaustion and lack of interest (93%), anxiety (89%), late-onset insomnia (86%), early-onset insomnia (73%), increased body awareness (69%), somatic anxiety (65%), feelings of guilt (62%), depressed mood (61%), and general somatic symptoms (61%). The mean scores (± SD) on the HAMD-17 five days after AMI are presented in Table 1.

In terms of sociodemographic characteristics, women exhibited a significantly higher prevalence of early depressive symptoms than men (Fisher’s exact test, p = .035). However, no significant differences were found between patients with and without early depressive symptoms regarding age, living arrangement, marital status, maximum education level, and employment status (see Table 2).

Patients with a history of mental illness before AMI or current psychopharmacological treatment exhibited a higher likelihood of experiencing early depressive symptoms 5 days after AMI (history of mental illness before AMI: Fisher’s exact test, p < .001; current psychopharmacological treatment: Fisher’s exact test, p < .001). In contrast, no significant differences were observed in substance abuse (nicotine, alcohol, benzodiazepine, and illicit drugs) between patients with and without early depressive symptoms following AMI.

The associations of early depressive symptoms with a history of mental illness before AMI, current psychopharmacological treatment, and substance abuse are detailed in Table 2.

Analysis of acute cardiac status at the time of admission due to AMI, PCI-related parameters, in-hospital outcome parameters, preexisting cardiac risk factors, and anthropometry revealed no significant differences between patients with or without early depressive symptoms (see Table 3).

Anxiety, Intrusions, Hyperarousal, and avoidance within the first days after AMI

The HAMD-17 scores, assessed 5 days after AMI, exhibited significant correlations with other psychological measures. Specifically, HAMD-17 scores were positively correlated with the HADS-anxiety subscale scores (Spearman’s ρ = 0.536; p < .001) and the IES-R subscale scores for intrusions (Spearman’s ρ = 0.479; p < .001), hyperarousal (Spearman’s ρ = 0.553; p < .001), and avoidance (Spearman’s ρ = 0.434; p < .001). The mean scores for HAMD-17, HADS-Anxiety, and IES-R, all measured five days after AMI, are summarized in Table 1.

Development of depression and PTSD in the Long-term

Transition of early depressive symptoms into depression 6 months after AMI

Patients with early depressive symptoms within the first days after AMI were significantly more prone to developing clinically significant depression 6 months later compared to those without such symptoms (Fisher’s exact test, p < .001). Specifically, 80% (44/55) of patients with early depressive symptoms experienced such a transition into depression in the long term. Among these, 66% (29/44) suffered from mild depression, 27% (12/44) from moderate depression, and 7% (3/44) from severe depression. Conversely, 13% (7/55) of patients who initially had early depressive symptoms were free from any psychopathology 6 months later.

31% (23/74) of patients without early depressive symptoms within the first days after AMI also exhibited clinically significant depression 6 months later. Among these patients, 78% (18/23) experienced mild depression, 13% (3/23) moderate depression, and 9% (2/23) severe depression.

Sex differences were observed in the results, with more women than men suffering from clinically significant depression 6 months after AMI (Fisher’s exact test, p = .037). Additionally, patients in solitary living arrangements had a significantly higher risk of suffering from depression 6 months after AMI (Fisher’s exact test, p = .044). However, no significant differences were found in age, marital status, maximum education level, and employment status between patients with and without AMI-related depression 6 months after AMI (see Table 2).

Patients with a history of mental illness before AMI and current psychopharmacological treatment were more likely to suffer from clinically significant depression 6 months after AMI (Fisher’s exact test, p = .019 and p = .038, respectively). However, no significant differences were found in substance abuse (nicotine, alcohol, benzodiazepine, and illicit drugs) between patients with and without AMI-related depression. Table 2 presents the associations of depression 6 months after AMI with a history of mental illness before AMI, current psychopharmacological treatment, and substance abuse.

Patients with a positive history of myocardial infarction before the index AMI had a significantly higher risk of suffering from depression 6 months after AMI (Fisher’s exact test, p = .047) (see Table 3). No other cardiological parameters, including acute cardiac status at admission due to AMI, PCI-related parameters, other preexisting cardiac risk factors, and anthropometry, showed a significant impact. Table 3 presents the associations of depression 6 months after AMI with acute cardiac status at the time of admission due to AMI, PCI-related parameters, in-hospital outcome parameters, preexisting cardiac risk factors, and anthropometry.

PTSD as a comorbidity of AMI-induced depression

Patients who exhibited early depressive symptoms within the initial days after AMI and transitioned into depression 6 months later faced a significantly higher risk of developing comorbid PTSD symptoms compared to those without early depressive symptoms (Fisher’s exact test, p < .001). Among those with depression 6 months post-AMI, 61% (27/44) also experienced comorbid PTSD. Specifically, 17% (5/29) of patients with mild depression, 50% (6/12) of patients with moderate depression, and 100% (3/3) of patients with severe depression met all PTSD criteria from A to F for the diagnosis of comorbid full PTSD 6 months after AMI.

The visual representation of these findings is depicted in Fig. 1.

No significant differences were observed between depressive patients with AMI-related comorbid PTSD symptomatology and those without concerning sociodemographic characteristics, history of mental illness before AMI, current psychopharmacological treatment, substance abuse, parameters of acute cardiac status at the time of in-hospital admission due to AMI, PCI-related parameters, preexisting cardiac risk factors, and anthropometry (refer to Tables 2 and 3).

Subsyndromal PTSD without depression

Within the cohort, a total of 4 out of 55 patients (7%) experiencing early depressive symptoms five days after AMI exhibited solely subsyndromal PTSD symptomatology six months later, without concurrent clinically significant depression. Among these, 1 patient (25%) lacked one of the PTSD criteria from B to E, and 3 patients (75%) lacked two of the PTSD criteria from B to E for a full PTSD diagnosis.

Moreover, 8 out of 74 patients (11%) without early depressive symptoms within the initial days after AMI also suffered from subsyndromal PTSD symptomatology but not depression six months post-AMI. Within this subgroup, 3 patients (36%) lacked one of the PTSD criteria from B to E, and 5 patients (64%) lacked two of the PTSD criteria from B to E.

Refer to Fig. 1 for a graphical representation of these results.

Identification of predictors for post-AMI depression and PTSD

Early predictors of AMI-induced depression in the long-term

The optimal model for predicting HAMD-17 scores 6 months after AMI involved a linear combination of a constant, the HAMD-17 score 5 days after AMI, the score on the IES subscale for hyperarousal 5 days after AMI, and a solitary living arrangement. Detailed outcomes of the stepwise multiple regression analysis are presented in Table 4.

Early predictors of comorbid PTSD

The most effective model for predicting CAPS-5 scores 6 months after AMI involved a linear combination of a constant, the IES subscale score for avoidance within the initial days after AMI, and a solitary living arrangement. The detailed results of the stepwise multiple regression analysis are presented in Table 4.

Discussion

The early psychological response to AMI as a complex phenomenon

This study examined early psychological symptoms within the first days after AMI and their predictive value for the development of AMI-related depression and PTSD in the long term. The observed findings highlight the intricate interplay of psychosocial and biological factors in the aftermath of AMI, underscoring the need for a more comprehensive biopsychosocial approach to treatment.

In this study, five days after AMI, 43% of AMI patients exhibited a wide range of clinically relevant psychological symptoms, including early depressive symptoms, anxiety, intrusion, avoidance, and hyperarousal. Women, individuals living alone, and those with a history of psychiatric illness or treatment were at increased risk of developing these early psychological symptoms. These findings align with Edmondson’s diathesis-stress model, which emphasizes that preexisting psychiatric conditions serve as key vulnerability factors that interact with the traumatic experience of a cardiac event, increasing the risk of PTSD and depression14.

Classifying this early psychological response pattern presents challenges. Labeling it as a depressive episode seems inadequate given the diversity of symptoms, and the brief duration makes such a classification inappropriate. Instead, the close association of these symptoms suggests a complex psychological response pattern indicative of overall mental distress, as discussed by Baranyi et al.39. The concept of ‘overall mental distress’ is broader than the term ‘mental illness’ and refers to psychological symptoms such as depression, anxiety, or emotional dysregulation, even in the absence of a formal psychiatric diagnosis39.

Requirements for early detection & need for early intervention

The high prevalence of early depressive symptoms, hyperarousal, and avoidance in 43% of AMI patients within the first days after AMI underscores the importance of recognizing overall mental distress shortly after the cardiac event. As Edmondson’s Enduring Somatic Threat (EST) model suggests, it is not merely the occurrence of the cardiac event itself but rather the persistent perception of an internal threat that plays a crucial role in shaping long-term psychological outcomes14. This ongoing sense of vulnerability may contribute to the development of AMI-related depression and PTSD, making early psychological distress a key predictor of future mental health complications. In this study, early depressive symptoms, hyperarousal, and solitary living arrangements were significant predictors of AMI-induced depression, while early avoidance symptoms and solitary living arrangements were significant predictors of comorbid PTSD. Figure 2 presents a biopsychosocial perspective that integrates the findings of this study regarding AMI-related depression and comorbid PTSD.

While our analysis focused on identifying risk factors for persistent PTSD and depression, it is equally important to consider why some individuals do not develop these disorders despite experiencing AMI-related psychological distress. Our regression models were also suitable for detecting protective factors; however, none were identified within the variables assessed in this study. This finding suggests that resilience mechanisms, such as cognitive appraisal, perceived control, or social support, may play a role in the spontaneous remission of early symptoms but were not captured within our dataset. Future research should explore these factors further to refine screening and intervention strategies aimed at preventing chronic psychopathology following AMI.

The progression of early symptoms into clinically significant depression in 80% of cases observed in this study aligns with Pedersen et al.5 and reinforces the prognostic value of early detection. Notably, 49% of these depressive AMI patients also experienced comorbid PTSD in the long term, underscoring the substantial mental health burden. The occurrence of PTSD without clinically significant depression, observed only in subclinical form six months after AMI, contributed to our interpretation of PTSD as frequently co-occurring with AMI-induced depression. However, we recognize that an alternative perspective in the literature views PTSD following cardiovascular events as an independent consequence of cardiac events, as explored in recent years. Some studies suggest that cardiac disease-induced PTSD can be distinct from depression and may serve as an independent predictor of recurrent CVD and mortality40,41,42, highlighting the need for further investigation into the relationship between these disorders.

Implications for clinical practice

Incorporating psychological screening for early depressive symptoms, hyperarousal, and avoidance within the first days post-AMI by trained staff, such as medical residents, nurse practitioners, and psychologists, is therefore vital to identify high-risk patients at an early stage. This could prevent the progression of AMI-related depression and PTSD and support the establishment of an effective biopsychosocial post-AMI treatment approach. Such targeted early intervention may mitigate the risk of severe psychiatric conditions, as also noted by Van Dijk et al.22, Carney and Freedland23, Edmondson et al.14,43, and Birk et al.16,44.

The impact of gender, living alone, and a history of psychiatric morbidity observed in this study highlights the need for personalized care plans, as recommended by Edmondson et al. and Richards et al.14,22. These plans should address preexisting mental health conditions and incorporate gender-specific psychosocial interventions. High-risk patients identified in this context might benefit from referrals to outreach or community-based psychosocial services, which have shown particular efficacy in elderly patients45,46,47. To strengthen the implementation of early interventions, it is essential to identify the most effective strategies. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has shown promise in reducing posttraumatic stress symptoms in high-risk patients following acute medical events48. Structured psychological counseling, such as brief trauma-focused interventions, may also be beneficial, particularly when integrated into standard post-hospitalization care49. Additionally, pharmacological treatments, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), have demonstrated efficacy in reducing PTSD symptoms in some patient populations50,51. However, while these interventions show promise, further randomized controlled trials are needed to determine their effectiveness specifically in survivors of life-threatening medical events. Future research should focus on identifying the most efficient and feasible strategies for implementation in diverse clinical settings.

Study limitations and future directions

The study’s limitations, including its exclusive focus on Caucasian participants, underscore the need for future research to explore potential ethnic variations in these associations. Additionally, while our study primarily focused on early psychological symptoms as predictors of long-term depression and PTSD, we acknowledge that other factors—such as stress levels, social support, socioeconomic status, and personality traits—could further contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of psychiatric morbidity after AMI. While our linear regression analysis was, in principle, also suited to identify protective factors among the clinical-cardiological and psychometric parameters we examined, none were found within the assessed variables. This suggests that resilience mechanisms, for example, cognitive appraisal, perceived control, or social support, may contribute to symptom remission but were not captured in our study. Future research should integrate these psychosocial variables to refine predictive models and improve personalized interventions for at-risk patients.

Furthermore, while previous studies in this domain have often included larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods, our study provides valuable insights by examining the very early psychological response within the first days post-AMI – a critical but relatively understudied period. Despite the smaller sample size, we employed rigorous psychometric assessments and validated diagnostic tools to ensure the reliability of our findings. However, we acknowledge that the generalizability of our results may be limited, and future studies with larger cohorts and extended follow-up durations are necessary to confirm and expand upon our findings. Integrating established psychocardiological frameworks into future research and clinical practice will be essential in addressing the growing mental health burden associated with cardiovascular disease.

Conclusions

This study highlights the significant role of early psychological symptoms as predictors of depression and PTSD following AMI in the long term. Implementing early screening and tailored interventions based on a biopsychosocial AMI model is crucial for improving mental health outcomes in AMI patients. Future research should focus on better understanding specific symptomatology patterns and gender-specific differences, emphasizing the importance of personalized care plans.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Thygesen, K. et al. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 72 (18), 2231 (2018).

Reed, G. W., Rossi, J. E. & Cannon, C. P. Acute myocardial infarction. Lancet 389 (10065), 197–210 (2017).

Wang, J. et al. Resilience and its influencing factors after emergency percutaneous coronary intervention in young and middle-aged patients with first acute myocardial infarction. Sci. Rep. 14, 9507. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-59885-9 (2024).

Wu, M. et al. The prevalence of acute stress disorder after acute myocardial infarction and its psychosocial risk factors among young and middle-aged patients. Sci. Rep. 12, 7675. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-11855-9 (2022).

Pedersen, S. S., von Känel, R., Tully, P. J. & Denollet, J. Psychosocial perspectives in cardiovascular disease. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 24 (3_suppl), 108–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487317703827 (2017).

Huffman, J. C., Smith, F. A., Blais, M. A., Januzzi, J. L. & Fricchione, G. L. Anxiety, independent of depressive symptoms, is associated with in-hospital cardiac complications after acute myocardial infarction. J. Psychosom. Res. 65 (6), 557–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.08.001 (2008).

Pająk, A. et al. Depression, anxiety, and risk factor control in patients after hospitalization for coronary heart disease: the EUROASPIRE III study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 20 (2), 331–340 (2013).

Burg, M. M. & Soufer, R. Post-traumatic stress disorder and cardiovascular disease. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 18 (10), 94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-016-0770-5 (2016).

Baranyi, A. et al. Assessment of trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) as a potential biomarker of severe stress in patients vulnerable to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after acute myocardial infarction. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 12 (1), 1920201. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.1920201 (2021).

Frasure-Smith, N., Lespérance, F. & Talajic, M. Depression following myocardial infarction. Impact on 6-month survival. JAMA 270 (15), 1819–1825 (1993).

Scherer, M. et al. Psychological distress in primary care patients with heart failure: a longitudinal study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 57 (543), 801–807 (2007).

Rocha, L. P. et al. Incidence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after myocardial infarction (MI) and predictors of PTSD symptoms post-MI – a brief report. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 38 (3), 297–306 (2008).

Roberge, M. A., Dupuis, G. & Marchand, A. Post-traumatic stress disorder following myocardial infarction: prevalence and risk factors. Can. J. Cardiol. 26 (5), e170–e175 (2010).

Edmondson, D. An enduring somatic threat model of posttraumatic stress disorder due to acute life-threatening medical events. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass. 8, 118–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12089 (2014).

Edmondson, D. et al. Posttraumatic stress due to an acute coronary syndrome increases risk of 42-month major adverse cardiac events and all-cause mortality. J. Psychiatr Res. 45, 1621–1626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.07.004 (2011).

Birk, J. L. et al. Association between cardiac event-induced PTSD symptoms and daily intrusive thoughts about cardiac risk: an ecological momentary assessment study. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 86, 103–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2023.11.014 (2024).

Juruena, M. F., Werne Baes, C. V., Menezes, I. C. & Graeff, F. G. Early life stress in depressive patients: role of glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors and of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity. Curr. Pharm. Des. 21, 1369–1378. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612821666150105125500 (2015).

Knezevic, E., Nenic, K., Milanovic, V. & Knezevic, N. N. The role of cortisol in chronic stress, neurodegenerative diseases, and psychological disorders. Cells 12, 2726. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12232726 (2023).

Vellapandian, P. S. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis: unveiling the potential mechanisms involved in stress-induced Alzheimer’s disease and depression. Cureus 16, e67595. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.67595 (2024).

Nijm, J. & Jonasson, L. Inflammation and cortisol response in coronary artery disease. Ann. Med. 41, 224–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890802508934 (2009).

Rothenhäusler, H. B., Stepan, A., Kreiner, B., Baranyi, A. & Kapfhammer, H. P. Patterns of psychiatric consultation in an Austrian tertiary care center - results of a systematic analysis of 3,307 referrals over 2 years. Psychiatr Danub. 20 (3), 301–309 (2008).

van Dijk, M. R. et al. Depression and anxiety symptoms as predictors of mortality in PCI patients at 10 years of follow-up. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 23 (5), 552–558. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487315571889 (2016).

Carney, R. M. & Freedland, K. E. Depression and coronary heart disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 14, 145–155 (2017).

Greenman, P. S. et al. Of sound heart and Mind: a scoping review of risk and protective factors for symptoms of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress in people with heart disease. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 33 (5), E16–E28. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCN.0000000000000508 (2018).

Richards, S. H. et al. Psychological interventions for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 4, CD002902 (2017).

Lespérance, F., Frasure-Smith, N., Talajic, M. & Bourassa, M. G. Five-year risk of cardiac mortality in relation to initial severity and one-year changes in depression symptoms after myocardial infarction. Circulation 105 (9), 1049–1053 (2002).

Larsen, K. K. Depression following myocardial infarction – an overseen complication with prognostic importance. Dan. Med. J. 60 (8), B4689 (2013).

Resurrección, D. M. et al. Factors associated with non-participation in and dropout from cardiac rehabilitation programmes: a systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 18 (1), 38–47 (2018).

Hamilton, M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 6 (4), 278–296 (1967).

Larsen, K. K., Vestergaard, M., Søndergaard, J. & Christensen, B. Screening for depression in patients with myocardial infarction by general practitioners. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 20 (5), 800–806. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487312444994 (2013).

Zimmerman, M., Martinez, J. H., Young, D., Chelminski, I. & Dalrymple, K. Severity classification on the Hamilton depression rating scale. J. Affect. Disord. 150 (2), 384–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.04.028 (2013).

Horowitz, M., Wilner, N. & Alvarez, W. Impact of event scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom. Med. 41, 209–218 (1979).

Zigmond, A. S. & Snaith, R. P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 67 (6), 361–370 (1983).

Weathers, F. W. et al. The Clinician-Administered PTSD scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation in military veterans. Psychol. Assess. 30 (3), 383–395. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000486 (2018).

National Center of PTSD. Clinician-administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5) – PTSD, accessed July 4, (2024). https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-int/caps.asp

Baranyi, A. et al. Relationship between post-traumatic stress disorder, quality of life, social support, and affective and dissociative status in severely injured accident victims 12 months after trauma. Psychosomatics 51 (3), 237–247. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psy.51.3.237 (2010).

Antman, E. M. et al. The TIMI risk score for unstable Angina/Non–ST elevation MI. JAMA 284 (7), 835–842 (2000).

Killip, T. & Kimball, J. T. Treatment of myocardial infarction in a coronary care unit. A two year experience with 250 patients. Am. J. Cardiol. 20 (4), 457–464 (1967).

Baranyi, A., Krauseneck, T. & Rothenhäusler, H. B. Overall mental distress and health-related quality of life after solid-organ transplantation: results from a retrospective follow-up study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 8, 11–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-11-15 (2013).

Vilchinsky, N., Ginzburg, K., Fait, K. & Foa, E. B. Cardiac-disease-induced PTSD (CDI-PTSD): a systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 55, 92–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.04.009 (2017).

Edmondson, D. et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder prevalence and risk of recurrence in acute coronary syndrome patients: a meta-analytic review. PLoS One. 7, e38915. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0038915 (2012).

Khan, N. et al. Association of cardiovascular diseases with post-traumatic stress disorder: an updated review. Cardiol. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1097/CRD.0000000000000628 (2023).

Edmondson, D. et al. A test of the diathesis-stress model in the emergency department: who develops PTSD after an acute coronary syndrome? J. Psychiatr Res. 53, 8–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.02.009 (2014).

Birk, J. L. et al. Early interventions to prevent posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in survivors of life-threatening medical events: a systematic review. J. Anxiety Disord. 64, 24–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2019.03.003 (2019).

Klug, G. et al. Effectiveness of home treatment for elderly people with depression: randomized controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry. 197 (6), 463–467. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083121 (2010).

Klug, G., Gallunder, M., Hermann, G., Singer, M. & Schulter, G. Effectiveness of multidisciplinary psychiatric home treatment for elderly patients with mental illness: a systematic review of empirical studies. BMC Psychiatry 19(1) .382. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2369-z

Farley RL, Wade TD, Birchmore L. Factors influencing attendance at cardiac rehabilitation among coronary heart disease patients. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2003 2: 205–212

Darnell, D. et al. Enhancing the reach of cognitive-behavioral therapy targeting posttraumatic stress in acute care medical settings. Psychiatr Serv. 68, 258–263. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201500458 (2017).

von Känel, R. et al. Early psychological counseling for the prevention of posttraumatic stress induced by acute coronary syndrome: the MI-SPRINT randomized controlled trial. Psychother. Psychosom. 87, 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1159/000486099 (2018).

Hidalgo, R. B. & Davidson, J. R. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in post-traumatic stress disorder. J. Psychopharmacol. 14, 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/026988110001400110 (2000).

Stein, D. J., Ipser, J. C. & Seedat, S. Pharmacotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 1, CD002795. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002795.pub2 (2006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.A.-G., D.v.L., M.S. and A.B. contributed to the conception or design of the work. O.A.-G., D.v.L., A.W.K., L.H., G.K., S.M., B.H., J.W.S, D.E., B.O.-P., H.R., M.P., H.K. and A.B. contributed to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work. M.S. prepared Figs. 1 and 2. O.A.-G., D.v.L., M.S., A.W.K. and A.B. drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript and gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Amouzadeh-Ghadikolai, O., von Lewinski, D., Wagner-Skacel, J. et al. Red flags for depression and PTSD following acute myocardial infarction: the role of early psychological symptoms. Sci Rep 15, 14033 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97755-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97755-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Predictive modeling of depression and anxiety after myocardial infarction: a study on influential factors and heart rate variability

Health Information Science and Systems (2025)