Abstract

Amphibian conservation breeding programs often rely on assisted reproductive technologies (ART) to produce offspring due to the difficulty of replicating natural reproductive cues under human care. Reproductive management using in-vitro fertilization (IVF) with cryopreserved sperm has been successfully applied to a variety of anurans, yet the approach has seen limited use for internally-fertilizing caudates. This study aimed to test two cryoprotectants, dimethyl formamide (DMFA) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), in combination with three different sperm extenders, HAM’s F-10, diluted HAM’s F-10, and 10% Holtfreter’s, for the production of salamander larvae from cryopreserved sperm. Fresh sperm was collected from tiger salamanders (n = 12) and diluted with one of three extenders, then subsequently mixed 1:1 with cryoprotectant. Samples were frozen using liquid nitrogen and later thawed to be applied in IVF. The diluted HAM’s and DMFA treatment resulted in the highest (p < 0.05) fertilization rate, with over 40% of eggs cleaving. The DMFA treatments resulted in 87 hatched offspring, while DMSO treatments resulted in only one offspring. This research highlights the potential of biobanking to produce internally-fertilizing salamander larvae, with DMFA being the likely preferred sperm cryoprotectant. These findings can inform conservation breeding programs by increasing caudate population sustainability through genetic management, facilitated by ART.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The caudate family Ambystomatidae, otherwise known as the mole salamanders, consists of 37 species ranging across North America1–2. Nearly half (18 out of 37 species) are listed as Vulnerable, Endangered, Critically Endangered, or Data Deficient2. Due to salamanders’ reliance on water as part of their reproductive niche, threats such as pollution, habitat destruction, drought, diseases, and climate change have had major impacts on populations in recent decades2–3. To help avert extinctions, captive breeding programs for amphibians have been established to increase the long-term sustainability of populations where in-situ conservation actions alone cannot ensure the survival of a species4. Unfortunately, many threatened ambystomid species in captivity (e.g., Ambystoma bishopi, A. cingulatum, A. californiense, A. andersoni) can be challenging to reproduce even with appropriate simulation of natural conditions, potentially impacting the establishment of reintroduction programs and long-term genetic sustainability. Conservation breeding programs can benefit from the implementation of assisted reproductive technologies (ART) such as hormone administration, ultrasound analysis, sperm cryopreservation, and in-vitro fertilization (IVF) to manage reproduction and increase genetic diversity. Over the last several decades, numerous advancements in anuran ART could be applicable to caudates5–6. The development of a germplasm biobank for caudates, where frozen sperm could be thawed and used to produce offspring with increased genetic diversity, would have great potential for the genetic management and conservation of threatened mole salamanders.

Gamete survival during the cooling and rewarming stages of cryopreservation can be impacted by a range of factors. Threats to gamete survival include metabolic imbalances, changes in membrane fluidity, DNA damage from oxidative stressors, and induced apoptosis7–8. Cryoprotectants, sperm extenders, and freezing/thawing rates can help mitigate some of the mechanical and chemical stress on cell physiology and structure during freezing. For example, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and dimethyl formamide (DMFA) are two permeating cryoprotective agents (CPAs) that have been applied to sperm cell cryopreservation across several taxa including mammals9–10, birds11–12, coral13–14, and fish15–16. The purpose of DMSO and DMFA in sperm cryopreservation is to depress the melting point of water, facilitate controlled dehydration, and inhibit ice crystal formation that leads to cellular damage during freezing. Both DMSO and DMFA have been useful for cryopreserving anuran (frog and toad) sperm17,18,19. Recent research with Fowler’s toads (Anaxyrus fowleri) showed that DMFA was superior to DMSO in recovering post-thaw sperm motility20. Within caudates, DMSO has been used to cryopreserve sperm from externally-fertilizing hellbenders (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis)21. Yet, a direct comparison of DMFA to DMSO on the post-thaw sperm metrics and embryo production has not been examined for internally-fertilizing caudates.

Following exogenous hormone treatments, ambystomid salamander milt is excreted in very small volumes (e.g., 10 µL) at high concentrations22,23,24 and requires an extender to dilute the sperm for analysis. During cryopreservation, an extender can also help maintain motility and fertility, provide energy substrates, stabilize the plasma membrane, and prevent the harmful effects of pH and osmolality changes25. For tiger salamanders (Ambystoma tigrinum), the most frequently used sperm extender has been 10% Holtfreter’s solution22,24, which is meant to mimic stream or pond water. Although 10% Holtfreter’s solution is useful for anuran sperm, where fertilization occurs in aquatic environments, it may not be the optimal extender for use with mole salamander sperm, where fertilization is internal. Therefore, commercial extenders optimized for internally-fertilizing species, such as mammals, may provide better protective mechanisms through the freezing process for internally-fertilizing salamanders. A recent study by Chen et al.23 examining various extenders on tiger salamander sperm metrics found that 10% Holtfreter’s solution, HAM’s F-10, and diluted HAM’s F-10 nutrient mix provided better pre-freeze motility and morphology over time compared to other extenders. The combination of extender and cryoprotectant could have a compounding effect on survival through the freezing process.

The objectives of this study were to test two different CPAs, DMFA and DMSO, in combination with three different extenders on: (1) post-thaw sperm parameters including motility, viability, and morphology, and (2) embryo cleavage rates for tiger salamanders. We hypothesized that, given our previous findings showing DMFA produced higher post-thaw sperm metrics for anurans, a similar finding would be observed for caudates, with higher embryo production following optimal post-thaw sperm quality. Our overarching goal was to find a cryosolution treatment that was capable of producing tiger salamander offspring from frozen-thawed sperm, which could eventually be applied to the management of threatened mole salamanders in conservation breeding programs.

Methods

Experimental animals and hormone administration

Captive-bred, sexually mature male eastern tiger salamanders (n = 12) were housed in 30 × 46 × 66 cm enclosures, with 5 cm of coconut fiber as bedding, in groups of 2–6 animals26. Salamanders were kept on a 12-hour light cycle and provided with water baths as well as clay and polyvinyl chloride hides and were fed a diet of crickets (Gryllodes sigillatus), mealworms (Tenebrio molitor), and Dubia roaches (Blaptica dubia) dusted with a calcium supplement (Zoo Med Laboratories, Inc., CA, USA) and vitamin mix (Supervite, Repashy Ventures Inc., CA, USA). Males were administered gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) at a concentration of 1 µg/µL nasally using a pipette, or alternatively through injection into the epaxial muscle26. Following hormone treatment, males were kept individually in 28 × 15 × 13 cm plastic tubs with 200 mL of water for up to 48 h until a sufficient volume and concentration of milt (several microliters of thick, white viscous material above 1 × 106 sperm/mL) was collected. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All experimental protocols were approved by Mississippi State University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (#20–160). The ARRIVE guidelines were additionally followed to the best of our ability.

Sperm collection, analysis, and cryopreservation

Milt was collected with a pipette by lightly tapping the cloaca of male salamanders (n = 12) for 10 s, then massaging downwards on the lateral sides for another 10 s, and finally applying light pressure above the pelvis on each side. Milt was subsequently diluted to a concentration of 1 × 106 sperm/mL with either: (1) 10% Holtfreter’s (chemicals purchased from Sigma-Aldrich®); (2) HAM’s F-10 solution (FUJIFILM Irvine Scientific®, Catalog No. 99168), or (3) diluted HAM’s F-10 solution, to a standardized concentration of 1 × 106 sperm/mL for all three treatments. Diluted HAM’s F-10 was generated by diluting HAM’s F-10 stock (~ 1:2.3) with sterile embryo transfer water (Sigma-Aldrich®, Catalog No. W1503) to 90 mOsm/kg23 (see Supplementary Table S1). Each extended sperm suspension was then mixed 1:1 with either of two stock cryoprotectants to a final concentration of: (1) 10% dimethyl formamide (DMFA) + 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA), or (2) 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) + 0.5% BSA, resulting in a 3 × 2 factorial design (3 extenders x 2 cryoprotectants) with six treatments (Fig. 1).

Diluted fresh milt samples were analyzed immediately after collection and before cryopreservation for several sperm quality parameters including progressive motility (PM; sperm actively rotating in a circular motion), stationary motility (SM; flagella movement without circular movement), and total motility (TM), which was calculated as PM + SM20. The velocity of PM sperm was observed on a scale where 5 indicates maximal circular rotation, 1 indicates minimal circular rotation, and 0 indicates no movement. Sperm morphology was categorized as either normal or abnormal with subcategories of damaged heads, tails, or both20. Both motility and morphology parameters were assessed from the unbiased observation of 100 random sperm cells under a 20x objective lens using a phase contrast microscope (Olympus® CX41), and sperm concentration (sperm/mL) was analyzed using a Neubauer® hemocytometer.

Extended sperm samples were loaded into 0.25 mL Minitube cryo-straws for an equilibrium period of 10 min while on an ice pack and subsequently frozen by parallel suspension in liquid nitrogen vapor at 10 cm above the liquid nitrogen surface (providing a cooling rate of -20 to -29 °C/min17) for 10 min before plunging into the liquid. All 12 male salamanders provided enough extended sperm for each of the six experimental treatments, with 2–4 straws frozen down from each treatment. For post-thaw sperm analysis, a total of 162 straws (2–4 straws/treatment/male) were thawed in a 40 °C water bath for approximately 5 s and assessed for PM, SM, TM, relative TM (post-thaw total motility/pre-thaw total motility), relative normal morphology (post-thaw normal morphology/pre-thaw normal morphology), and velocity. In addition, we measured sperm viability post-thaw using an Invitrogen™ Live/Dead stain containing SYBR14/propidium iodide, where live (green) and dead (red) sperm cells were counted out of 100 random cells on the slide using an Olympus® CX41 microscope with fluorescent attachment.

In-vitro fertilization using frozen sperm

To obtain eggs from tiger salamanders for the fertilization trials, females (n = 7) were hormonally stimulated through intramuscular injections and eggs manually expressed as previously described27. A subset of cryopreserved sperm straws (n = 40) was thawed for the IVF trials representing 7/12 males biobanked with 1 straw/treatment (except for one male where two treatments were excluded due to lack of eggs; 6 treatments x 7 males = 42 − 2). Immediately upon spawning of eggs, frozen sperm straws were thawed and used for IVF. Sperm was pipetted onto eggs in Petri dishes (mean = 18 eggs/dish) where 50,000 sperm cells were applied neat or diluted 1:1 with purified water from each straw into two respective dishes and underwent a 10 min fertilization period before dishes (n = 80) were flooded with water (~ 100 mL until eggs were covered). For comparison purposes, negative parthenogenetic control dishes were included (i.e., no sperm applied to eggs) for each female (n = 7 dishes) to ensure early cleavage was not a result of manipulating the eggs, while non-frozen, fresh sperm positive control dishes were included for each female (n = 7 dishes) to ensure eggs were of good quality. Eggs were examined for fertilization individually with a dissection microscope for cleavage rate (2–4 cell) approximately 6–8 h after sperm was applied. Embryo and larval development were monitored through metamorphosis and the number of salamanders moving to terrestrial life-stage counted27.

Statistical analysis

Pre-freeze sperm parameters were compared between the three extenders using Kruskal-Wallis tests. Post-thaw PM, TM, relative TM, relative normal morphology, viability, velocity of movement, and embryo cleavage rates were compared between the six overall treatments (extender + cryoprotectant) using Generalized Additive Models for Location, Scale, and Shape. Straws of the same treatment were averaged across males. Normality of the data was analyzed using the Shapiro-Wilk test and histogram visualization, whereas homoscedasticity was checked with a Levene’s test. The ‘gamlss’ package within the program R28 was used for the modeling analysis. The cryodiluent treatment (e.g., 10% Holt + DMFA) was used as a fixed effect, while individual male was the random effect. Either a beta, normal, beta inflated, or lognormal family was used for model fit depending on the distribution of the response variable. Residuals of the models were checked with Q-Q plots and Shapiro-Wilk tests to ensure proper model fit. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare embryo cleavage rates between diluted and undiluted thawed sperm. Data are shown as mean ± SEM, with the alpha value set as 0.05 for significance testing.

Results

Pre-freeze sperm parameters

We compared the three extenders’ (10% Holtfreter’s solution, HAM’s F-10, and diluted HAM’s F-10) impact on several salamander sperm metrics to determine if one of the solutions stood out as a better medium for initial dilution and analysis. Comparison of the three groups revealed there was no significant difference (n = 36; p > 0.05) between any of the pre-freeze sperm parameters including PM, SM, TM, velocity, or normal morphology (Table 1). The average PM for sperm in the three extenders ranged from 28 to 35%, while the average TM ranged from 57 to 61% for samples prior to freezing. Average velocity of sperm ranged from 3.1 to 3.2, while normal morphology ranged from 68 to 71% (Table 1). The measure of spread within the range was clustered tightly resulting in the absence of any effect on sperm metrics between the extenders, indicating that extender did not affect sperm quality prior to freezing. Thus, all three extenders were chosen to be tested, in combination with the two CPAs (10% DMFA or DMSO), on sperm freeze-thawing resilience.

Effect of cryosolution treatment on sperm post-thaw parameters

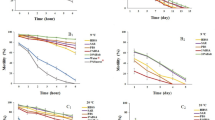

In contrast to the pre-freeze sperm data, several differences were found within post-thaw sperm metrics, suggesting the treatments impacted sperm quality and survival during the cryopreservation process. The average post-thaw sperm parameters and significant differences for PM, TM, velocity, viability, and normal morphology are shown in Table 2, while Fig. 2 provides additional information on the distribution of the data set. Included in Fig. 2 is a measure of relative TM, which provides an assessment of what we recovered, compared to the initial pre-freeze TM. We observed that all treatments containing 10% Holtfreter’s, regardless of CPA, resulted in lower (p < 0.05) post-thaw PM (Table 2; Fig. 2A) and TM (Table 2; Fig. 2B) for sperm samples compared to other treatments. In contrast, DMSO + HAM’s produced the highest PM (13%) and TM (32%), although there was no difference in PM between this treatment and DMFA + HAM’s or DMFA + diluted HAM’s (Table 2). Figure 2B shows that while the average post-thaw TM was in the mid-20s for DMFA + HAM’s and diluted HAM’s, quite a few samples were much higher, even reaching over 40% TM. Similarly, DMSO + HAM’s and diluted HAM’s had several samples with TM over 40% and even a couple of samples near 60% post-thaw motility.

Comparison of post-thaw metrics of tiger salamander (n = 12 males with 2–4 straws averaged per treatment) sperm samples frozen with the two cryoprotectants (10% DMSO + 0.5% BSA and 10% DMFA + 0.5% BSA) and the three extenders (10% Holt = 10% Holtfreter’s, HAM’s = HAM’s F-10 nutrient mix, and Dil HAM’s = diluted HAM’s to 90 mOsm). (A) Post-thaw progressive motility; (B) Post-thaw total motility; (C) Relative post-thaw (final/initial) sperm motility; and (D) Post-thaw velocity of movement. Whiskers show the range of the data (excluding outliers), and boxes represent the interquartile range. Black horizontal bars represent the median, while white diamonds indicate the mean. Different letters represent significant (p < 0.05) differences within a panel.

When evaluating the post-thaw recovered motility relative to pre-freeze motility, we found that the DMSO + HAM’s treatment produced the overall highest (p < 0.05) post-thaw relative motility (52 ± 7%), while DMSO + 10% Holtfreter’s (28 ± 4%) and DMFA + 10% Holtfreter’s (26 ± 4%) resulted in the lowest (p < 0.05) relative motilities (Fig. 2C). Thus, we were able to recover slightly over 50% of our starting motility following cryopreservation using DMSO + HAM’s. We found that post-thaw velocity of movement was lowest (p < 0.05) for treatments containing 10% Holtfreter’s (DMSO: 1.6 ± 0.3, DMFA: 1.8 ± 0.3) across any of the treatments (Table 2; Fig. 2D). Sperm viability was similar (p > 0.05) across treatments except for DMFA + 10% Holtfreter’s (21 ± 3%) and DMSO + 10% Holtfreter’s (24 ± 3%), which had lower (p < 0.05) viability compared to all other treatments. In nearly all treatments, viability either closely matched or exceeded the motility by a small margin, possibly suggesting that most cells not exhibiting motility were also dead.

Effect of cryosolution treatment on embryo cleavage

To examine whether post-thaw sperm metrics from our six cryopreservation treatments are a reliable indicator of fertilization and embryo development, we conducted IVF trials to evaluate these effects. From post-thaw sperm data, it would be naturally assumed that DMSO + HAM’s should present with a higher embryo cleavage rate given its higher TM and relative TM. Interestingly, we found that DMFA + diluted HAM’s (40 ± 9%) had higher (p < 0.05) embryo cleavage rates than all other treatments (Fig. 3). One of the thawed sperm straws used for IVF resulted in > 60% embryo cleavage rates for the DMFA + diluted HAM’s treatment (Fig. 3). All treatments containing DMSO (HAM’s: 3 ± 1%; diluted HAM’s: 10 ± 7%; 10% Holtfreter’s: 5 ± 3%) were similar (p > 0.05) to each other and exhibited the overall lowest embryo cleavage rates, with none of the average rates exceeding 10% (Fig. 3). Half of the thawed sperm straw volume for each treatment was diluted 1:1 with water upon expulsion to determine if reducing the concentration of cryoprotectant would provide higher embryo cleavage rates. We did not see any differences (p > 0.05) in embryo cleavage rates (19 ± 3% vs. 18 ± 3%). Thus, both diluted and undiluted thawed sperm from each of the six cryodiluent treatments were grouped together for the above analysis. Overall, a total of 88 tiger salamander larvae successfully hatched from embryos that were generated with frozen-thawed sperm, with only one larva successfully hatching from any of the DMSO treatments, while 87 hatched collectively from the DMFA treatments. Figure 4 shows various images of the progression from two-cell cleaved embryos through hatched larvae formation for offspring produced using cryopreserved sperm from the DMFA treatments.

Comparison of embryo cleavage rates (2–4 cells) resulting from sperm cryopreserved with the two cryoprotectants used (10% DMSO + 0.5% BSA and 10% DMFA + 0.5% BSA) and the three diluents (10% Holt = 10% Holtfreter’s, HAM’s = HAM’s F-10 nutrient mix, and Dil HAM’s = diluted HAM’s to 90 mOsm). Whiskers show the range of the data (excluding outliers), and boxes represent the interquartile range. Black horizontal bars represent the median, while white diamonds indicate the mean. Different letters represent significant (p < 0.05) differences across the six treatments.

Discussion

With nearly half of all Ambystomatidae salamander species threatened with extinction, advancing conservation strategies, such as biobanking and IVF for genetic management and reintroduction programs, are desperately needed for long-term sustainability. Here, we compared the use of six different cryosolutions mixed with tiger salamander sperm on survival, motility, velocity, and normal morphology through cryopreservation. Moreover, we compared these same six freezing treatments on early embryo development, which is an important bioassay to use as a measure of success for sperm function. Our hypothesis that DMFA would result in better post-thaw sperm metrics and subsequent embryo cleavage rates was only partially supported. In contrast to our predicted outcome that DMFA would result in better overall post-thaw sperm metrics, DMFA was not different from DMSO for most of the metrics measured, while also resulting in overall lower total motility for several cryoprotective solution treatments. Despite the lower total motility, DMFA-treated sperm resulted in much higher embryo cleavage rates, which was counter-intuitive to our prediction that embryo cleavage rates would follow the treatments with higher post-thaw motility. Our results further indicate that functionality of tiger salamander sperm through the cryopreservation process depends not only on the principal extender used to dilute the sperm samples for analysis, but also on the CPA employed. In this experiment, we found that all three treatments containing 10% DMSO appeared toxic to embryo development given the low cleavage rates and only one metamorphosed larva. Embryo cleavage was not observed in the parthenogenetic control IVF dishes, indicating that the frozen sperm fertilized eggs in this study. We were able to achieve the highest fertilization rate (over 40%) of tiger salamander eggs using frozen-thawed sperm to date, which led to the successful hatching of 88 tiger salamander larvae; to our knowledge, this result represents the largest clutch of salamanders produced using cryopreserved sperm.

Prior to this study, post-thaw motility of tiger salamander sperm frozen using combinations of DMSO, bovine serum albumin (BSA), and trehalose ranged between 0 and 14%24,29, which is low relative to several anuran species18,20,30. For example, previous cryopreservation work showed that tiger salamander sperm frozen in 10% Holtfreter’s + 5% DMSO + 0.5% BSA resulted in a post-thaw total motility of about 10% with ~ 25% of eggs being fertilized24. This average post-thaw motility is similar to what we obtained here with 10% Holtfreter’s + 10% DMSO + 0.5% BSA, except the percent of eggs fertilized is higher than what we observed. This further suggests that DMSO is toxic at higher concentrations, and its continued use in amphibian cryobiology may need to be reduced to concentrations below what is often reported in the literature. DMFA may be a good replacement for DMSO as it provided good fertilization rates in the current study. Previous studies also showed that trehalose, a common non-permeating cryoprotectant used for sperm freezing in anurans17–18,20, was toxic to salamander sperm29. Hence, there are a number of unique differences in how salamander sperm responds to co-incubation with CPAs compared to anuran sperm.

In addition, our discovery that 10% Holtfreter’s had significantly lower progressive and total motility upon thawing than sperm co-incubated with HAM’s F-10 or diluted HAM’s F-10 was an interesting finding and improved upon past performance metrics. The higher post-thaw motility in both HAM’s F-10 treatments could be due to the lower water content in these solutions as compared to 10% Holtfreter’s that is predominantly water, which causes cell damage upon formation of ice crystals31. In addition to the lower water content in HAM’s F-10, the medium’s unique chemical composition and osmolality may also have impacted the post-thaw motility results. Higher concentrations of antioxidants, energy sources, and amino acids found in the HAM’s and diluted HAM’s may offer benefits during the fertilization process compared to the simple salt solution of 10% Holtfreter’s. For example, thioctic acid is an antioxidant found within HAM’s and has been linked to improved IVF outcomes in the mouse model32. Diluted HAM’s was significantly better than HAM’s for fertilization when combined with DMFA, which suggests there is possibly an effect of osmolality that is impacting the fertilization process. Past research found that Ciona intestinalis embryos that underwent a brief osmotic shock experienced a lack of neurula rotation and subsequent cell death33. The lower osmolality with the diluted HAM’s treatment may be supporting a more natural fertilization environment, thereby avoiding osmotic shock to the sperm and/or eggs.

Relative post-thaw sperm motility was the highest (> 50%) when sperm were cryopreserved using 10% DMSO + 0.5% BSA. This improves upon initial work in which tiger salamander sperm that was frozen in 5% DMSO + 0.5% BSA was recovered at only 18%24. While our post-thaw motility results were encouraging using DMSO, we found the CPA had negative effects on embryo development compared to DMFA. This highlights the importance of testing post-thaw sperm motility metrics in addition to fertilization capabilities in IVF. The better embryo cleavage rates for the DMFA treatments are reflected in the number of larvae hatched with 87 tiger salamanders produced from frozen sperm using DMFA, while only one individual was produced using sperm frozen with DMSO. We suggest that the 10% DMSO may be toxic to salamander eggs during the fertilization period, although we are uncertain where the fertilization process may be affected (e.g., sperm binding, penetration, pronuclei formation, fusion of the pronuclei to form a zygote). Alternatively, 10% DMSO could be activating a polyspermy block mechanism in the eggs preventing fertilization34. The high viscosity and osmolality (> 1,400 mOsm) of the DMSO treatments could be impacting eggs by causing the movement of water out of the eggs via osmosis. For example, DMSO has been found to have membrane thinning activity through lipid bilayer reorganization35, which could be negatively affecting the outer layer of salamander eggs, thus exacerbating dehydration. The stability of the outer jelly coat layers is especially important for fertilization in internally-fertilizing caudates36, and the high water volume within salamander eggs could be negatively impacted by DMSO at the 10% concentration (1485–1737 mOsm). In comparison, our DMFA treatments have a much lower total osmolality (140–280 mOsm), which may be more tolerable for both the salamander sperm cells and eggs. Despite diluting salamander sperm cryopreserved with DMSO, this treatment still appeared toxic during the fertilization process. Future experiments using DMSO may need to examine whether thawed sperm could be diluted at a higher ratio (e.g., 1:10) or lightly centrifuged (100 x g) and resuspended to separate the sperm from the cryoprotectant37, which may yield higher fertilization rates.

To date, comparisons between DMFA and DMSO for cryopreserving amphibian sperm have only been explored in anurans. For example, Shishova et al.19 found that cryosolutions containing DMFA resulted in significantly higher post-thaw motility and membrane integrity in Rana temporaria sperm compared to DMSO and that sperm treated with DMFA had higher fertilization rates and a significantly higher number of viable larvae seven days post-fertilization. Although work in Fowler’s toads showed no difference on embryo development rates between 10% DMFA and 10% DMSO, embryo development rate was higher with 5% DMFA than with 10% DMSO20. Together, these results with a limited number of species suggest that use of DMFA may be a preferable alternative to the use of DMSO in biobanking programs. However, DMSO has been used with success (> 50% post-thaw motility) with certain anuran species’ sperm38,39,40, though these did not test the effect on fertilization rate. Our results in an Ambystomatidae species support the use of DMFA as a cryoprotectant for this family of caudates, especially due to the production of numerous offspring that could supplement a conservation breeding program. While the eastern tiger salamander (A. tigrinum) is not currently threatened, many regional populations are now gone or in decline due to land conversion and habitat degradation. Moreover, this research is especially valuable for its potential application to other ambystomid salamanders (e.g., A. californiense, A. cingulatum, A. bishopi, A. andersoni) in captive care, which are federally listed and found on the IUCN Red List2. Overall, this research shows that DMFA can be successfully used to cryopreserve ambystomid sperm and produce offspring.

Conclusions

The findings from this study support the use of diluted HAM’s F-10 medium as an extender and DMFA as a cryoprotectant for freezing salamander sperm. Further work is needed into methodologies for washing tiger salamander sperm cryopreserved with DMSO to warrant its future use, as the chemical appears toxic during the fertilization process. The results from this study suggest that sperm motility post-cryopreservation may not be the optimal functional assay for sperm fertilization potential in tiger salamanders, and more studies should consider IVF to test the functionality of frozen sperm. The high number of offspring produced using diluted HAM’s F-10 medium and 10% DMFA demonstrates how genetic diversity through biobanking of cryopreserved sperm can be applied as a conservation tool for the long-term, sustainable management of declining salamanders.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in this publication as well as from the corresponding author, A.J.K., upon request.

References

AmphibiaWeb Species Lists. The Regents of the University of California. (2023). https://amphibiaweb.org/lists/index.shtml.

IUCN. The IUCN red list of threatened species. Version 2022-1. (2022). https://www.iucnredlist.org.

Woolrich-Piña, G., Smith, G. R., Lemos-Espinal, J. A., Zamora, A. E. & Ayala, R. M. Observed localities for three endangered, endemic Mexican ambystomatids (Ambystoma altamirani, A. leorae, and A. rivulare) from central Mexico. Herpetol Bull. 139, 12–15 (2017).

Carrillo, L., Johnson, K. & Mendelson, I. I. I. Principles of program development and management for amphibian conservation captive breeding programs. IZN 62(2), 96–107 (2015).

Kouba, A. J. Genome resource banks as a tool for amphibian conservation. in Reproductive Technologies and Biobanking for the Conservation of Amphibians 204 (CRC Press, 2022).

Kouba, C. K. & Julien, A. R. Linking in situ and ex situ populations of threatened amphibian species using genome resource banks. in Reproductive Technologies and Biobanking for the Conservation of Amphibians 188 (CRC Press, 2022).

Baust, J. M., Snyder, K. K., VanBuskirk, R. G. & Baust, J. Changing paradigms in biopreservation. Biopreserv Biobank 7(1), 3–12 (2009).

Costanzo, J. P., Mugnano, J. A., Wehrheim, H. M. & Lee, R. E. Jr Osmotic and freezing tolerance in spermatozoa of freeze-tolerant and-intolerant frogs. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 275(3), R713–R719 (1998).

Bezerra, F. S. B. et al. Objective assessment of the cryoprotective effects of dimethylformamide for freezing goat semen. Cryobiology 63(3), 263–266 (2011).

Si, W., Zheng, P., Li, Y., Dinnyes, A. & Ji, W. Effect of glycerol and dimethyl sulfoxide on cryopreservation of rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) sperm. Am. J. Primatol. 62(4), 301–306 (2004).

Herrera, J. A., Quintana, J. A., López, M. A., Betancourt, M. & Fierro, R. Individual cryopreservation with dimethyl sulfoxide and polyvinylpyrrolidone of ejaculates and pooled semen of three avian species. Arch. Androl. 51(5), 353–360 (2005).

Taşkın, A., Ergün, F., Karadavut, U. & Ergün, D. Effects of extenders and cryoprotectants on cryopreservation of duck semen. TURJAF 8(9), 1965–1970 (2020).

Hagedorn, M. et al. Preliminary studies of sperm cryopreservation in the mushroom coral, Fungia scutaria. Cryobiology 52(3), 454–458 (2006).

Viyakarn, V., Chavanich, S., Chong, G., Tsai, S. & Lin, C. Cryopreservation of sperm from the coral Acropora humilis. Cryobiology 80, 130–138 (2018).

Aoki, K., Okamoto, M., Tatsumi, K. & Ishikawa, Y. Cryopreservation of Medaka spermatozoa. Zool. Sci. 14(4), 641–644 (1997).

Zhang, Y. Z. et al. Cryopreservation of flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) sperm with a practical methodology. Theriogenology 60(5), 989–996 (2003).

Burger, I. J. et al. Applying sperm collection and cryopreservation protocols developed in a model amphibian to three threatened anuran species targeted for biobanking management. Biol. Conserv. 277, 109850 (2023).

Poo, S. & Hinkson, K. M. Applying cryopreservation to anuran conservation biology. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 1(9), e91 (2019).

Shishova, N. R., Uteshev, V. K., Kaurova, S. A., Browne, R. K. & Gakhova, E. N. Cryopreservation of hormonally induced sperm for the conservation of threatened amphibians with Rana temporaria as a model research species. Theriogenology 75(2), 220–232 (2011).

Burger, I. J., Lampert, S. S., Kouba, C. K., Morin, D. J. & Kouba, A. J. Development of an amphibian sperm biobanking protocol for genetic management and population sustainability. Conserv. Physiol. 10(1), coac032 (2022).

McGinnity, D., Reinsch, S. D., Schwartz, H., Trudeau, V. & Browne, R. K. Semen and oocyte collection, sperm cryopreservation and IVF with the threatened North American giant salamander Cryptobranchus alleganiensis. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 34(5), 470–477 (2021).

Gillis, A. B. et al. Short-term storage of tiger salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum) spermatozoa: The effect of collection type, temperature and time. PLoS One 16(1), e0245047 (2021).

Chen, D. M. et al. Comparing novel sperm extenders for the internally-fertilizing tiger salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum). Front. Amphib Reptile Sci. 1, 1320803 (2024).

Marcec, R. M. Development of assisted reproductive technologies for endangered North American salamanders. (Doctoral dissertation, Mississippi State University, 2016).

Bustani, G. S. & Baiee, F. H. Semen extenders: an evaluative overview of preservative mechanisms of semen and semen extenders. Vet. World. 14(5), 1220 (2021).

Chen, D. M. Advancing salamander conservation efforts in zoos and aquaria through assisted reproductive technologies (ART). (Doctoral dissertation, Mississippi State University, 2023).

Lampert, S. S. Oocytes to offspring: Optimizing assisted reproductive technologies (ART) to support amphibian conservation. (Master’s thesis, Mississippi State University, 2023).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2022). https://www.R-project.org/.

Gillis, A. B. Assisted reproductive technologies in male ambystoma tigrinum with application to threatened newt species. (Master’s thesis, Mississippi State University, 2020).

Uteshev, V. K., Shishova, N. V., Kaurova, S. A., Manokhin, A. A. & Gakhova, E. N. Collection and cryopreservation of hormonally induced sperm of pool frog (Pelophylax lessonae). Russ J. Herpetol. 20(2), 105–109 (2013).

Sharma, Y. & Sharma, M. Sperm cryopreservation: Principles and biology. J. Infertil Reprod. Biol. 8(3), 43–48 (2020).

Truong, T. & Gardner, D. K. Antioxidants improve IVF outcome and subsequent embryo development in the mouse. Hum. Reprod. 32(12), 2404–2413 (2017).

Katsumoto, S., Hatta, K. & Nakagawa, M. Brief hypo-osmotic shock causes test cell death, prevents neurula rotation, and disrupts left-right asymmetry in Ciona intestinalis. Zool. Sci. 30(5), 352–359 (2013).

Gould, M. Polyspermy-preventing mechanisms. in Biology of Fertilization V3: The Fertilization Response of the Egg vol. 3, 223 (2012).

Gironi, B. et al. Effect of DMSO on the mechanical and structural properties of model and biological membranes. Biophys. J. 119(2), 274–286 (2020).

Watanabe, A. & Onitake, K. The urodele egg-coat as the apparatus adapted for the internal fertilization. Zool. Sci. 19(12), 1341–1347 (2002).

Yang, H., Hazlewood, L., Walter, R. B. & Tiersch, T. R. Effect of osmotic immobilization on refrigerated storage and cryopreservation of sperm from a viviparous fish, the green swordtail Xiphophorus helleri. Cryobiology 52(2), 209–218 (2006).

Kouba, A. J. et al. Emerging trends for biobanking amphibian genetic resources: the hope, reality and challenges for the next decade. Biol. Conserv. 164, 10–21 (2013).

Langhorne, C. J. Developing assisted reproductive technologies for endangered North American amphibians. (Doctorial dissertation, Mississippi State University, 2016).

Upton, R. et al. Refrigerated storage and cryopreservation of hormonally induced sperm in the threatened frog, Litoria aurea. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 262, 107416 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Austin Simpson and Tamera Abram for their assistance in the lab with research projects and husbandry care of the animals.

Funding

This project was supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service (ARS), Biophotonics project #6066-31000-015-00D and is a contribution of the Mississippi Agriculture and Forestry Experiment Station under the National Institute of Food and Agriculture Hatch project accession numbers W3173 and W4173; an Institute of Museum and Library Services National Leadership Grant on Amphibian Sustainable Collections Management grant #MG-30-17-0052-17 and an IMLS National Leadership Grant on the Amphibian and Biobanking Network grant #MG-251614-OMS-22. Lastly, this publication is a contribution of the Forest and Wildlife Research Center, Mississippi State University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.M.C.: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing—original draft. S.S.L.: Conceptualization, Investigation. L.C.: Investigation, Writing—review & editing. I.J.B.: Conceptualization, Investigation. C.K.K.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. N.S.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. T.L.R.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. P.J.A.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. A.J.K.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, D.M., Lampert, S.S., Chen, LD. et al. Production of live tiger salamander offspring using cryopreserved sperm. Sci Rep 15, 15702 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99052-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99052-2