Abstract

Comparing data from different years and the time of year during which data are collected can affect respondents’ answers or health status. This study investigated the possible association between seasonality and the self-reported health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) during rehabilitation and at a 2-year follow-up. The study included 1026 respondents (79% men; mean age 56 ± 9 years). Baseline characteristics covered socio-demographic, clinical factors, and psychological assessments using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. HRQoL was evaluated using the 36-item Short Form Medical Outcome Questionnaire (SF-36) and the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ). The MLHFQ data were collected longitudinally. The results of the multivariable linear regression confirmed a potential association between seasonality and self-reported HRQoL as assessed during cardiac rehabilitation period in patients with CAD. According to the SF-36, the summer season was associated with improved mental health outcomes, while the winter season was significantly linked to better scores in the pain domain. Based on the MLHFQ data, the winter season was associated with better overall HRQoL both during rehabilitation and at the 2-year follow-up. Similarly, the MLHFQ physical dimension showed better scores in winter at the 2-year follow-up, but not at baseline.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) remains a significant public health concern1, with negative implications for health-related quality of life (HRQoL). CAD is a chronic disease with many physical, psychological, social, and economic issues that affect the patient’s adherence to treatment guidelines. CAD has an impact on an individual’s physical, emotional, and social functions, which prevents them from being happy with their lives and lowers their quality of life2. HRQoL is a patient-reported outcome that represents the functional impact of an illness and its subsequent therapy on a patient’s daily life as perceived by the patient3. The assessment of HRQoL is encouraged both in research studies and in the clinical care of patients with CAD. There is evidence that poor HRQoL, rather than more conventional risk factors, can predict negative health outcomes in patients with CAD, such as cognitive decline, mortality, and subsequent hospitalization4,5,6,7. Due to the growing importance of HRQoL in the management of individuals with cardiac pathologies, it is encouraged to consider not only identifying the main risk factors associated with impaired quality of life in this population but also assessing other factors that may also contribute to the HRQoL assessment score8,9,10.

Several human physiology and behavior elements are known to exhibit seasonal fluctuations, which can be attributed to the mid-to-long-term influences of meteorological conditions and non-atmospheric factors such as environmental conditions or socioeconomic status11,12,13. Seasonality, the systematic periodicity of events over the course of a year, is a well-known phenomenon in the life and health sciences14. The changes in the seasons cause changes in many environmental and social variables. These changes are repeated year after year and create a natural experiment for studying links between seasonal exposure and disease15. Seasonality has been well documented to influence cardiovascular events16, emotional and psychiatric disorders17, and many rheumatic diseases18. Comparing data from different years and the time of year during which data are collected can affect respondents’ answers or health status19. A recent study showed how much variation there is by month in happiness and life satisfaction data20. Although numerous studies have examined HRQoL until now, little is known about the impact of seasonality on self-reported HRQoL in patients with CAD19,21. According to evidence in the literature, patients with heart disease are more vulnerable to environmental triggers. Therefore, in patients with CAD, seasonality might have a more pronounced impact on HRQoL. For instance, cold weather can lead to increased blood pressure and heart rate due to blood vessel constriction22. This added strain on the cardiovascular system can exacerbate symptoms such as chest pain and shortness of breath, which negatively affects HRQoL. Fluctuations in sunlight exposure during different seasons can affect mood and mental health, with studies showing a correlation between mental illness and cardiovascular disease23. All the above and other factors can exacerbate symptoms, leading to a decline in HRQoL during certain seasons.

As mentioned above, we hypothesized that the seasonal variation is associated with the subjective report of HRQoL. Our study aimed to investigate the possible association with seasonality on the self-reported HRQoL of patients with CAD during rehabilitation and at a 2-year follow-up.

Results

Baseline and follow up characteristics of study variables

Baseline sociodemographic variables, clinical characteristics, and HADS scores are presented in Table 1.

The majority (81%, n = 834), of the participants had NYHA functional class II, and 11% (n = 113) were NYHA functional class III. There were no patients classified as NYHA IV class in this study. The prevalence of patients with anxiety disorder risk (HADS-A score ≥ 8) and depressive disorder risk (HADS-D score ≥ 5) was 30% (n = 303) and 33% (n = 340), respectively. The HRQoL scores, as reported using SF-36 and MLHFQ are shown in Table 2.

Associations between health-related quality of life and seasons

Table 3 presents the results of the univariate analyses, where potential predictors were screened. We hypothesized that the seasonal variation is associated with the subjective report of HRQoL. To investigate independent associations the multivariable linear regression analysis, which controlled for sex, age, NYHA classification, and mental distress symptoms was performed. Variables with a p-value less than 0.1 were identified in the univariate analyses for further inclusion in the multivariate analysis.

Even though not all variables showed significance in every season, separate multivariable linear regression models were constructed for each season to explore how the relationships between predictors and outcomes might vary due to seasonal factors. It should be noted that a higher NYHA class indicates a more severe condition, and participants classified as NYHA class III were more likely to report poorer total HRQoL scores during rehabilitation and poorer total and physical HRQoL scores at the 2-year follow-up.

Analysis revealed a significant seasonal influence on subjective scale score according to the SF-36 (Table 4). Specifically, findings indicated that the summer season (β = 0.066, 95% CI − 0.05 to 0.18, p = 0.010) was positively associated with improved mental health outcomes. The winter season was significantly linked to better assessments within the pain domain (β = 0.071, 95% CI − 0.13 to 0.27, p = 0.019), reflecting reduced pain intensity and fewer limitations in daily activities due to pain.

In the multivariable linear regression analysis, controlling for same confounders, but using MLHFQ as an outcome measure, was a trend of association observed between winter and better HRQoL (β = − 0.056, 95% CI − 0.19 to 0.08, p = 0.054 at baseline, β = − 0.059, 95% CI − 0.17 to − 0.05, p = 0.050 after 2 years), suggesting that patients reported slightly fewer health-related limitations in winter compared to other seasons. In the assessment period after 2 years, but not at the baseline, winter was associated with significantly better physical HRQoL (β = − 0.081, 95% CI − 0.14 to − 0.02, p = 0.008), suggesting that patients experienced fewer physical limitations in winter. Conversely, spring (β = − 0.065, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.12, p = 0.032) had a small negative impact, indicating slightly worse physical HRQoL in spring compared to other seasons. For additional visual representation of MLHFQ scores during rehabilitation and at the 2-year follow-up, see Supplementary Fig. 1.

Discussion

Our study aimed to investigate the possible association between seasonality and the self-reported HRQoL of patients with CAD. We found seasonal variations in the self-assessment of both generic and disease-specific HRQoL. Our findings highlight these seasonal differences, with winter showing potential benefits, especially for physical health. The winter season was associated with lower pain intensity and fewer pain-related limitations in daily activities (according to the SF-36 domains), and with a slightly better HRQoL compared to other seasons, as measured by the MLHFQ. Specifically, at baseline and after 2-years (according to the MLHFQ domains), winter showed a trend towards fewer health-related limitations. After 2 years, winter was significantly associated with better physical HRQoL, indicating fewer physical limitations. On the other hand, spring was associated with a small negative impact on physical HRQoL, suggesting slightly worse physical well-being in the spring compared to other seasons. Moreover, the summer season was associated with a better assessment of generic mental health-related quality of life in patients with CAD. Our study was conducted in a coastal climate region of Lithuania, characterized by a cool spring and cool summer, a warm winter often without permanent snow cover, a warm and rainy autumn, and slight variations in daily and annual temperatures24. The average air temperature in the area where the rehabilitation clinic is located and where the study was carried out is − 0.7 °C in winter, 6.1 °C in spring, 16.8 °C in summer and 8.6 °C in autumn.

The mean age of populations undergoing CR can vary based on the demographic and geographical characteristics of the study population. However, there are general trends in recent research showing that the average age of the predominantly post-MI and post-revascularization population ranges from 47 to 77 years25. In our study, the mean age was 56 ± 9 years, which is in line with these findings.

To our knowledge, this is the first study in which the possible effect of seasonal variation associated with general and disease-specific HRQoL was investigated in patients with CAD. Therefore, direct comparisons with previous studies are limited. We found only three studies that examined seasonality in HRQoL19,21,26. The most recent study conducted in southern Finland with four unique seasons investigated the possible seasonal variation in HRQoL among patients with rhinologic disease21. There was no statistically significant seasonal variation in either generic or disease-specific HRQoL. An earlier study conducted among the United States population showed the opposite results: physical HRQoL was best during summer and worst during winter19. However, mental health was worse during spring and autumn, suggesting that it was better in summer, as in our results. Possible reasons for the differences may be related to different measurement tools, study design, study location and especially investigated population. The nature of rhinologic diseases differs from coronary artery disease, where physical activity and respiratory health significantly impact HRQoL. Effective year-round management of rhinologic conditions may prevent significant seasonal variation in HRQoL. Patients with CAD are more sensitive to seasonal variations due to their cardiovascular condition, influencing both physical and mental HRQoL. Differences in climate conditions and daylight hours between the U.S., Finland, and Lithuania can influence how seasonal changes affect HRQoL. The instruments used to assess HRQoL in studies varied and captured different aspects of physical and mental health. Differences in the sensitivity and focus of these tools can lead to variations in reported outcomes.

Seasonality patterns are reported in mood and behavior in various mental disorders27,28, and changes in daylight hours are thought to be a major contributor to these seasonal variations in some symptoms10. Some studies show that the seasonality of mood and behavior is a dimension not distributed equally among diagnostic categories: it is linked more with affective disorders than with pure anxiety disorders29; the greater seasonality of symptoms is associated with more severe depression and mania28; and depressive symptoms usually peak in winter27. We found that the summer season was associated with a better assessment of mental health using a generic HRQoL instrument in patients with CAD. Meanwhile, there was no statistically significant seasonal variation in disease-specific emotional HRQoL. We assume these results are due to the different nature of questions in two different generic and disease-specific HRQoL questionnaires. While a substantial number of persons with CAD exhibited an elevated risk of depressive and anxiety disorders; however, we modified our results based on mental health status as assessed by HADS.

While the primary aim of this study was to examine seasonal variations in HRQoL, the results highlight that sex and disease severity (NYHA functional class) also have a considerable impact. Women reported worse HRQoL, which is consistent with previous studies suggesting that female patients with heart failure often experience greater symptom burden and lower physical functioning30. Additionally, patients classified as NYHA functional class III experience significantly worse HRQoL outcomes associated with physical activity compared to those in NYHA functional classes I–II. The significant effect of NYHA functional class III on HRQoL aligns with findings that more severe heart failure symptoms are strongly associated with reduced quality of life31.

Seasonality effects depend on how an individual or community controls its exposure to and physiological response to environmental stimuli, such as cold or heat32. Since the quality of life, pain, and physical condition are subjective health complaints, we hypothesized that seasonal differences in our study are related more to psychological and behavioral factors. One factor is seasonal behavioral patterns in physical activity. In winter, people are generally less physically active, probably because of the colder weather and lack of sunlight. The results of a recently conducted systematic review showed that physical activity increases significantly in the summer and spring months compared to winter, and sedentary behavior follows the opposite trend33. This occurs independently of the countries’ climate, the characteristics, and the previous pathologies of the participants. There is also less work in the home environment during the winter months. This may explain why patients with CAD in our study reported some dimensions of HRQoL, mainly those associated with physical components, better in the winter. When life is less active, people feel the impact of illness on their quality of life less strongly.

Strengths and limitations

Large sample size, longitudinal design and the use of well-validated instruments are the major strengths of our study. The findings of this study provide important information about the long-term effects of seasonality on HRQoL assessment in patients with CAD. Despite the consistent results, our study has limitations. Participant recruitment from a single cardiac rehabilitation center could have subjected our results to selection bias. Particularly, most of the patients were males, had NYHA-II functional class and all of them attended a single in-patient center, which may limit the generalization of our results. There is a strong need for replication in more diverse clinical samples, particularly by including more female participants. This emphasis on female inclusion is supported by existing evidence of gender differences in cardiovascular disease outcomes34.

Conclusions and implications

Our results confirmed a possible association with seasonality on the self-reported HRQoL assessment during cardiac rehabilitation in patients with CAD. The association of seasonality with HRQoL was relatively minor, which limits the straightforward clinical interpretation of the study results. The large sample size allowed the detection of small effects, but the clinical importance of these results requires further cross-validation in future studies. Further research is needed across diverse populations (e.g., by age, gender, and comorbidities) and in different geographical regions to determine if certain subgroups are more affected by seasonal variations. This would help identify whether specific demographic or clinical profiles are more vulnerable to seasonally influenced changes in HRQoL during rehabilitation.

Materials and methods

Study design, setting and participants

This prospective observational study was designed and reported in accordance with the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines35. The STROBE checklist was used to ensure completeness and accuracy in the reporting of the study’s design, methodology, and results. A completed STROBE checklist is provided in the supplementary material.

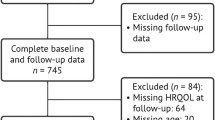

In a period from 2014 to 2024, a total of 1105 patients with CAD attending an in-patient cardiac rehabilitation programme at the Palanga Clinic of the Neuroscience Institute of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences in Palanga, Lithuania, were invited to participate in this study. Detailed rehabilitation programme is described elsewhere36. All patients participating in the study were admitted to the rehabilitation within two weeks after treatment for acute coronary syndromes (i.e., myocardial infarction25 or angina pectoris) and gave written informed consent. Patients were excluded from the present study for the following conditions/reasons: a) unstable cardiovascular status (n = 52), b) unwillingness to participate (n = 24), and c) current use of benzodiazepines (n = 3). Patients taking benzodiazepines were excluded from this study to avoid potential confounding effects on mood, sleep patterns, anxiety levels, and overall psychological well-being. Excluding such patients ensures that the results more accurately reflect the impact of seasonality on health-related quality of life without the interference of benzodiazepine-related effects. Following the exclusion criteria, the study population comprised 1026 (79% men and 21% women with a mean age of 56 ± 9 years) patients with CAD.

All participants underwent standardized diagnostic and treatment procedures for secondary CAD prevention based on the established guidelines37,38,39,40. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki for research with human beings and approved by the Ethics Committee for Biomedical Research at Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, Kaunas, Lithuania (Protocol code BE-2–9). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Study procedure

Within three days of admission for a cardiac rehabilitation, all participants’ socio-demographic (age, sex) and clinical (New York Heart Association41 functional class, medication use) records were obtained. At the same time, in a separate room in the clinic, patients participating in the study independently completed a questionnaire assessing symptoms of anxiety and depression as measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)42. In terms of HRQoL asessment, we used the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ)43 and the 36-Item Short Form Medical Outcome Questionnaire (SF-36)44. Only MLHFQ data were gathered longitudinally. This methodology was used to prevent overloading research participants with recurrent enquiries in a longitudinal setting; nonetheless, we recognise that this method reduced the comprehensiveness of the data gathered. Answers to the MLHFQ scale were recorded by a qualified nurse at baseline and after 2 years follow-up telephone interview. Due to the follow-up design at both 1 and 2 years, we were able to reach fewer patients for telephone interviews compared to the baseline. The longitudinal data for the MLHFQ included 925 participants who were interviewed at baseline, 1 year, and 2 years. There were no differences in baseline characteristics (see Supplementary Table S1) of study participants who were interviewed at baseline vs. those individuals who were interviewed during the follow-up.

Thus, each statistical model using the longitudinal data was performed on the sample of 925 individuals. In addition, all study tests were completed in full by study participants, resulting in no cases of missing data.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

During the initial interview with the main researcher (NK), demographic information on age and sex was obtained. The NYHA functional I-IV classification system was used by the cardiologist to classify the degree of functional disability based on the symptoms of fatigue, palpitations or dyspnea and activity limitations45. NYHA Class I represents no functional limitations, Class II represents slight limitations, Class III represents marked limitations in patient’s physical activity, and Class IV represents individual’s inability to carry out any physical activity without discomfort. Individual’s history of MI, acute MI and angina pectoris was retrieved from existing medical records.

Minnesota living with heart failure questionnaire

Disease-specific assessments, such as the MLHFQ, are recommended for accurately measuring HRQoL in patients with CAD and heart failure. The MLHFQ offers advantages over generic scales, as it is highly responsive and can distinguish varying degrees of change in an individual’s HRQoL. It is a widely used instrument specifically designed to assess HRQoL in patients with HF. The questionnaire consists of 21 questions covering physical, socioeconomic and psychological dimensions of life, relative to the limitations frequently associated with the profile of cardiac insufficiency43. Items are rated on a 6-point Likert scale from 0 (no impact of HF on HRQoL) to 5 (significant negative impact of HF on HRQoL). The total score is the sum of the responses and varies from 0 (no impairment) to 105 (total impairment). The psychometric properties of the scale are good, with Cronbach ɑ for total scale ranging from 0.83 to 0.91 in a previous study46. MLHFQ had good internal reliability in the current study (Total HRQoL Cronbach’s α = 0.91; Physical HRQoL Cronbach’s α = 0.88 and Emotional HRQoL Cronbach’s α = 0.82).

36-Item short form medical outcome questionnaire

The SF-36 is comprised of 8 multi-item scales that evaluate HRQoL on eight domains: (1) physical functioning, (2) social functioning, role limitations due to (3) emotional problems and (4) physical problems, (5) mental health, (6) energy/vitality, (7) pain, and (8) general health perception. Each SF-36 domain is scored from 0 to 100, where higher scores reflect better HRQoL44. The SF-36 was validated in Lithuania in patients with brain tumours47 and previous studies have reported acceptable internal consistency of Lithuanian translation of the SF-36 in CAD patients41,48. In our study, the internal reliability of eight subscales has been found to range between 0.56 and 0.85 in the current sample.

Hospital anxiety and depression scale

The HADS is a self-report questionnaire consisting of 14 items that are used to evaluate anxiety (HADS-A) and depression (HADS-D) symptoms49. Total scores on the HADS-A and HADS-D range from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating more severe anxiety or depressive symptoms. The Lithuanian version of HADS was documented to have good psychometric characteristics in patients with CAD (HADS-D Cronbach’s α = 0.79; HADS-A Cronbach’s α = 0.86)50,51. Good internal consistency of HADS was also observed in this study sample (HADS-D Cronbach’s α = 0.72; HADS-A Cronbach’s α = 0.83). Optimal cut scores for screening of anxiety disorder risk were set to ≥ 8 for the HADS-A and depressive disorder risk ≥ 5 for the HADS-D, and as defined in previous validation studies in general and CAD populations49,52.

Study location and seasons

The study was carried out in a country with four distinct seasons and varying winter-summer conditions. The city of Palanga is situated in northwest Lithuania on the Baltic Sea’s eastern shore and belongs to the country’s coastal climate region (55°58′ N, 21°03′ E). Its climatic indices differ from those of the other three Lithuanian climate zones and are closest to Europe’s maritime northwest climate. The classification of seasons was based on the date of data collection. According to the meteorological season calendar, spring begins on March 1, summer on June 1, autumn on September 1, and winter on December 1.

Statistical analysis

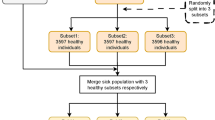

Statistical analysis were performed using the IBM SPSS, Version 29.0.0.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), while categorical variables are expressed as number (percent). The distribution of measures was evaluated using skewness and kurtosis. Means and frequencies were calculated for sociodemographic characteristics, cardiac variables, mental distress, as well as HRQoL scores. Initial univariate analyses were conducted to screen potential seasons as predictors of HRQoL, and variables with a p-value < 0.1 were included in the subsequent multivariable analysis. Separate multivariable linear regression models “enter method” were constructed for each season to assess the possible impact of seasonality on assessment of HRQoL while controlling for possible confounding factors such as sex, age, NYHA functional class, anxiety and depression scores. Categorical variables, as NYHA functional classes and seasons, were transformed into dummy variables for regression analysis. NYHA classification was recoded as a dummy variable, where NYHA classes I and II were grouped as the reference category (coded as 0), and NYHA class III was coded as 1. We grouped these variables based on clinical meaning—NYHA functional class I and II both represent milder heart failure symptoms, NYHA functional class III, in contrast, represents moderate to severe limitations in daily activities. Similarly, seasons were included as dummy variables, with winter, spring, and summer coded as 1 if applicable and 0 otherwise. Separate multivariable linear regression models were constructed for each of these seasons, except for autumn. Autumn was not included as it was not identified as a significant factor in the univariate analyses.

The minimum required sample size for a multiple regression model was calculated to be N = 921, based on a desired significance level of 0.05, six predictors in the model, an anticipated effect size (f2) of 0.02 (corresponding to a 2% increase in R2), and a desired statistical power of 0.9.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Virani, S. S. et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2021 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 143, e254–e743. https://doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000000950 (2021).

Muhammad, I., He, H. G., Kowitlawakul, Y. & Wang, W. Narrative review of health-related quality of life and its predictors among patients with coronary heart disease. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 22, 4–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12356 (2016).

Höfer, S., Benzer, W. & Oldridge, N. Change in health-related quality of life in patients with coronary artery disease predicts 4-year mortality. Int. J. Cardiol. 174, 7–12 (2014).

De Smedt, D., Clays, E. & De Bacquer, D. Measuring health-related quality of life in cardiac patients. Eur. Heart J. Qual. Care Clin. Outcomes 2, 149–150. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjqcco/qcw015 (2016).

Conradie, A. et al. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and the effect on outcome in patients presenting with coronary artery disease and treated with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI): Differences noted by sex and age. J. Clin. Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11175231 (2022).

Kazukauskiene, N. et al. Predictive value of baseline cognitive functioning on health-related quality of life in individuals with coronary artery disease: A 5-year longitudinal study. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 21, 473–482 (2022).

Gecaite-Stonciene, J. et al. Cortisol response to psychosocial stress, mental distress, fatigue and quality of life in coronary artery disease patients. Sci. Rep. 12, 19373 (2022).

Schweikert, B. et al. Quality of life several years after myocardial infarction: Comparing the MONICA/KORA registry to the general population. Eur. Heart J. 30, 436–443. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehn509 (2009).

Sudevan, R. et al. Health-related quality of life of coronary artery disease patients under secondary prevention: A cross-sectional survey from south India. Heart Surg. Forum. 24, E121-e129. https://doi.org/10.1532/hsf.3261 (2021).

Zhang, R. & Volkow, N. D. Seasonality of brain function: Role in psychiatric disorders. Transl. Psychiatry 13, 65 (2023).

Burkart, K. et al. Seasonal variations of all-cause and cause-specific mortality by age, gender, and socioeconomic condition in urban and rural areas of Bangladesh. Int. J. Equity Health 10, 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-10-32 (2011).

Winthorst, W., Post, W., Meesters, Y., Penninx, B. & Nolen, W. Seasonality in depressive and anxiety symptoms. Light Upon Seasonal. 17 (2020).

Martinaitienė, D. et al. A randomised controlled trial assessing the effects of weather sensitivity profile and walking in nature on the psychophysiological response to stress in individuals with coronary artery disease. A study protocol. BMC Psychol. 12, 82 (2024).

Naumova, E. N. Mystery of seasonality: Getting the rhythm of nature. J. Public Health Policy 27, 2–12. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jphp.3200061 (2006).

Barnett, A. G. & Dobson, A. J. Analysing Seasonal Health Data Vol. 30 (Springer, 2010).

Stewart, R. A. et al. Physical activity and mortality in patients with stable coronary heart disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 70, 1689–1700 (2017).

Geoffroy, P. A., Bellivier, F., Scott, J. & Etain, B. Seasonality and bipolar disorder: A systematic review, from admission rates to seasonality of symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 168, 210–223 (2014).

Patberg, W. R. & Rasker, J. J. Weather effects in rheumatoid arthritis: From controversy to consensus. A review. J. Rheumatol. 31, 1327–1334 (2004).

Jia, H. & Lubetkin, E. I. Time trends and seasonal patterns of health-related quality of life among US adults. Public Health Rep. 124, 692–701 (2009).

Blanchflower, D. G. & Bryson, A. Seasonality and the female happiness paradox. Qual. Quant. 8, 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-023-01628-5 (2023).

Ylivuori, M. et al. Seasonal variation in generic and disease-specific health-related quality of life in Rhinologic patients in southern Finland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 6428 (2021).

Liu, C., Yavar, Z. & Sun, Q. Cardiovascular response to thermoregulatory challenges. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 309, H1793-1812. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00199.2015 (2015).

Li, X., Zhou, J., Wang, M., Yang, C. & Sun, G. Cardiovascular disease and depression: A narrative review. Front Cardiovasc. Med. 10, 1274595. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2023.1274595 (2023).

Galvonaitė, A., Kilpys, J., Kitrienė, Z. & Valiukas, D. Lietuvos kurortų klimatas. Vilnius: Lietuvos hidrometeorologijos tarnyba prie Aplinkos ministerijos (2015).

Dibben, G. et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 11, Cd001800. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001800.pub4 (2021).

Challier, B. et al. Is quality of life affected by season and weather conditions in ankylosing spondylitis?. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 19, 277–281 (2001).

Magnusson, A. An overview of epidemiological studies on seasonal affective disorder. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 101, 176–184 (2000).

Reynaud, E. et al. Validity and usage of the seasonal pattern assessment questionnaire (SPAQ) in a French population of patients with depression, bipolar disorders and controls. J. Clin. Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10091897 (2021).

Wirz-Justice, A., Graw, P., Kräuchi, K. & Wacker, H. R. Seasonality in affective disorders in Switzerland. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. Suppl. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.108.s418.18.x (2003).

Johansson, P., Dahlström, U. & Broström, A. Factors and interventions influencing health-related quality of life in patients with heart failure: A review of the literature. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 5, 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2005.04.011 (2006).

Malik, A. & Chhabra, L. In StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2025, StatPearls Publishing LLC., 2025).

Stewart, S. et al. Winter peaks in heart failure: An inevitable or preventable consequence of seasonal vulnerability?. Card. Fail. Rev. 5, 83 (2019).

Garriga, A., Sempere-Rubio, N., Molina-Prados, M. J. & Faubel, R. Impact of seasonality on physical activity: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010002 (2021).

Narvaez Linares, N. F. et al. Neuropsychological sequelae of coronary heart disease in women: A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 127, 837–851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.05.026 (2021).

von Elm, E. et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 61, 344–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008 (2008).

Kazukauskiene, N. et al. Mental distress factors and exercise capacity in patients with coronary artery disease attending cardiac rehabilitation program. Int. J. Behav. Med. 25, 38–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-017-9675-y (2018).

Gibbons, R. J. et al. ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for exercise testing: summary article. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Update the 1997 Exercise Testing Guidelines). J. Am. College Cardiol. 40, 1531–1540 (2002).

Piepoli, M. F. Editor’s Presentation. Secondary prevention: First of all, address the basics. Eur. J. Prevent. Cardiol. 27, 227–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487320904919 (2020).

Piepoli, M. F. et al. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Revista espanola de cardiologia (English ed.) 69(939), 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2016.09.009 (2016).

O’Gara, P. T. et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: Developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians and Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Intervent. 82, E1-27. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccd.24776 (2013).

Staniute, M., Bunevicius, A., Brozaitiene, J. & Bunevicius, R. Relationship of health-related quality of life with fatigue and exercise capacity in patients with coronary artery disease. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 13, 338–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474515113496942 (2014).

Denollet, J. et al. Reduced positive affect (anhedonia) predicts major clinical events following implantation of coronary-artery stents. J. Intern. Med. 263, 203–211. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01870.x (2008).

Rector, T. S. & Cohn, J. N. Assessment of patient outcome with the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire: reliability and validity during a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of pimobendan. Pimobendan Multicenter Research Group. Am. Heart J. 124, 1017–1025 (1992).

Ware, J. E. Jr. & Sherbourne, C. D. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med. Care 30, 473–483 (1992).

Ponikowski, P. et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 18, 891–975. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.592 (2016).

Gecaite-Stonciene, J. et al. Validation and psychometric properties of the Minnesota living with heart failure questionnaire in individuals with coronary artery disease in Lithuania. Front. Psychol. 12, 771095. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.771095 (2021).

Bunevicius, A. Reliability and validity of the SF-36 Health Survey Questionnaire in patients with brain tumors: A cross-sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 15, 92. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0665-1 (2017).

Staniute, M., Brozaitiene, J. & Bunevicius, R. Effects of social support and stressful life events on health-related quality of life in coronary artery disease patients. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 28, 83–89. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCN.0b013e318233e69d (2013).

Zigmond, A. S. & Snaith, R. P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 67, 361–370 (1983).

Bunevicius, A., Peceliuniene, J., Mickuviene, N., Valius, L. & Bunevicius, R. Screening for depression and anxiety disorders in primary care patients. Depress Anxiety 24, 455–460. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20274 (2007).

Bunevicius, A., Brozaitiene, J., Stankus, A. & Bunevicius, R. Specific fatigue-related items in self-rating depression scales do not bias an association between depression and fatigue in patients with coronary artery disease. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 33, 527–529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.06.009 (2011).

Bunevicius, A., Staniute, M., Brozaitiene, J. & Bunevicius, R. Diagnostic accuracy of self-rating scales for screening of depression in coronary artery disease patients. J. Psychosom. Res. 72, 22–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.10.006 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank all the staff of the Laboratory for their great help in collecting the data, and for statistician Elena Bovina, who did significant work in analyzing the data. We thank the COST Action CA23113 “Climate change impacts on mental health in Europe (CliMent)”, supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology: www.cost.eu), for the inspiration to explore this topic.

Funding

This study is funded by a Grant (No. S-MIP-23-114) from the Research Council of Lithuania.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DM designed the study and wrote the first manuscript. JB and NK analyzed the data and drafted and edited the manuscript. FS, ZD and BG critical review of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Martinaitienė, D., Sampaio, F., Demetrovics, Z. et al. The role of seasonality on evaluating health-related quality of life in patients with coronary artery disease. Sci Rep 15, 15248 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99478-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99478-8