Abstract

Natural disasters occur when environmental systems have a disruptive effect on the socio-economic system. In recent years, particular unreasonable human behaviours have amplified losses from natural disasters as result of the increasing complexity of human systems. Because of the lack of both quantitative calculation of this amplification, and analysis of the root cause of these behaviours, existing risk assessment and management research rarely includes unreasonable human behaviour as a critical factor. This study therefore creates three simulation scenarios, each based on a twenty-first-century catastrophe in China, and calculates the disaster losses that are amplified when such behaviour increases exposure (the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake), vulnerability (the 2014 Ludian earthquake) and hazard (the 2021 Zhengzhou rainstorm) levels. In doing so, it intuitively demonstrates the amplification effect caused by unreasonable human behaviour. The results show that these behaviours amplified disaster losses significantly: increased exposure due to unscientific planning nearly doubled the death toll in the Wenchuan earthquake; high vulnerability caused by the low economic level of residents increased the disaster losses of the Ludian earthquake more than tenfold; and the elevated hazard intensity caused by anthropogenic climate change resulted in a 1.44-times expansion of the area severely affected by the Zhengzhou rainstorm. These behaviours have become an important cause of disasters, and the main driving factors behind them—such as neglecting disaster risk; the inability to cope with disasters; and a lack of certainty about how to deal with extreme events—are the inevitable outcomes of societal development. On this basis, we constructed an extended risk framework that included unreasonable behavioural factors and a disaster mechanism, to analyse in depth the relationship between human behaviours and disaster risk prevention in different developmental stages. The results provide an important reference for the development of risk management policies to control these unreasonable behaviours.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Natural disasters occur when environmental systems have a disruptive effect on the socio-economic system (Kates, 1978; Alexander, 1993). As socio-economic systems become more complex, the types of disasters that affect humans are becoming more diverse, and the range of impacts and losses they cause is expanding (Willner et al., 2018). Human have taken measures to reduce the impact of disasters, by addressing issues such as affordable housing, food security, poverty reduction, quality education, and social equity and equality, as outlined in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals for 2030 (Pielke, 2019; Raikes et al., 2021). As societies have developed, however, certain unreasonable human behaviours have begun to amplify the effects of natural disasters, e.g., when the excessive pursuit of economic benefits led to a population being concentrated in a disaster-prone area, and flooding was exacerbated because lakes had been converted to agricultural land (Brown and Westaway, 2011; Collins, 2018). A large number of previous studies analyse the influence degree and influence mechanism of these unreasonable human behaviours. Some focus on the mechanism of disaster formation, i.e., natural hazard, exposure and vulnerability (Wisner et al., 2004; Ward et al., 2020). These studies hold that the amplification effect of human behaviours on natural disasters is realised mainly when natural hazard, exposure or vulnerability are increased, and they focus on how human behaviours increase the intensity of these factors (Ward et al., 2020; Stuart-Smith et al., 2021). Some, for example, calculate changes in the intensity and frequency of meteorological hazards through the analysis of anthropogenic climate change (Ciscar et al., 2019; Wilhelm et al., 2022); and others ascertain differences in urban flood vulnerability through the analysis of urban land expansion (Smith et al., 2019). Other studies focus on the stakeholders of human behaviour (Aerts et al., 2018). They typically divide these stakeholders into three categories—individual, enterprise and government—and analyse the occurrence of unreasonable human behaviours in each, from the perspective of risk perception and decision-making (Slovic, 2000; Kellens et al., 2013). These analyses examine the lack of risk awareness, underestimation of the risk in the absence of recent experience of the hazard, and the use of short-term planning horizons by risk management stakeholders. Based on the literature, this study defines unreasonable human behaviours as human activities that lead to the amplification of disaster losses due to decision-making errors.

Previous studies provide a theoretical basis for understanding the amplification effect of human behaviours on disasters. Because of the complexity of human behaviour, however, most studies that focus on the formation mechanism of disasters are limited to the changes human behaviours induce in the factors of hazard, vulnerability and exposure; they do not calculate quantitatively the amplification of disaster losses caused by these behaviours (Aerts et al., 2018; Thieken et al., 2014). The lack of quantitative loss data makes it difficult for decision makers to understand intuitively the severity of the impact caused by these unreasonable human behaviours. As a result, disaster risk management measures rarely focus on controlling these behaviours. Similarly, studies that focus on the stakeholders of human behaviours concentrate on decision-making, but do not analyse the root cause of the eventual decision (Tierney, 2014). These limitations make it difficult for policy makers to take targeted measures to control these unreasonable human behaviours.

This paper takes three catastrophes in China as examples to quantitatively analyse the amplification effect of unreasonable human behaviours on disaster losses by increasing hazard, vulnerability and exposure through scenario simulation. Then, based on the level of social and economic development when the three catastrophes occurred, the root cause of unreasonable human behaviours is discussed. On this basis, an extended risk framework, including unreasonable behavioural factors and a disaster mechanism, is constructed to analyse the relationship between human behaviours and disaster risk prevention in different developmental stages. This study provides an important reference for risk assessment and risk management.

Methods

Study design

From the perspective of disaster formation mechanism, unreasonable human behaviours can easily increase the intensity of hazard, vulnerability and exposure. Such an increase in any of these factors can dramatically amplify losses, and can turn an ordinary disaster into a catastrophe (Fig. 1). To intuitively show the degree to which unreasonable human behaviour amplifies disaster loss by increasing hazard intensity, vulnerability and exposure, three catastrophes with amplified losses caused by unreasonable human behaviours were selected: one in which such behaviour increased hazard intensity; one in which it increased vulnerability; and one in which it increased exposure. Through the method of situational simulation, we calculated the possible losses of these three disasters without unreasonable human behaviours (assuming that other conditions remained unchanged), and compared the losses obtained by simulation with the actual losses to reflect the extent of the losses that may be amplified by unreasonable human behaviours.

a Mechanism of disaster formation. b–d Increased exposure, vulnerability or intensity of hazard due to unreasonable human behaviours amplified disaster losses. In a, the red squares represent disaster losses, which are determined by exposure, vulnerability and hazard. In b–d, the dark red squares represent amplified disaster losses due to increased exposure, vulnerability, or intensity of hazard caused by unreasonable human behaviours.

Case study selection and data sources

To avoid differences in management systems, this study selected three cases in the same country. China is among the countries with the highest number of disasters and the largest losses, and as such provides sufficient cases for research selection. In addition, the level of social and economic development in different regions in China varies greatly, and this allows an in-depth analysis of the reasons behind unreasonable human behaviours and their relationship to developmental levels.

The Wenchuan earthquake

In the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake, the lack of scientific urban planning meant that a large number of people lived near the earthquake fault zone: this unreasonable human behaviour therefore led to a substantial increase in exposure. The earthquake can therefore be used to simulate the degree of amplification of disaster losses as a result of increased exposure caused by human behaviour. To create a simulation for the Wenchuan earthquake, socio-economic and population death data were needed. The former, including GDP, population (population size), age (age structure), gender (gender ratio), social dependency(employed), and medical facilities (number of medical institutions), was collected from the 2008 Sichuan statistics yearbook (Sichuan Provincial Bureau of Statistics, 2008). The number of deaths caused by the earthquake was obtained from the Wenchuan post-disaster statistical report (Fan et al., 2009).

The Ludian earthquake

In the 2014 Ludian earthquake, the quake resistance of houses was far lower than that required for disaster prevention, and this substantial increase of housing vulnerability was the main reason for the huge disaster losses. It can therefore be used to simulate the amplification degree of disaster losses as a result of increased vulnerability caused by human behaviour. The data required for the Ludian earthquake simulation scenario included pre-quake housing distribution and structure data, a seismic intensity map, and post-quake housing damage data. It was obtained from the Ludian post-disaster statistical report (Fan et al., 2016).

The Zhengzhou rainstorm

The 2021 Zhengzhou rainstorm was caused by increased precipitation intensity as a result of anthropogenic climate change (Zhao et al., 2022). It can therefore be used to simulate the amplification degree of disaster losses due to increased hazard intensity caused by human behaviour. Meteorological data for the Zhengzhou rainstorm was collected from the Zhengzhou meteorological station, and a digital elevation model (DEM) of the area was downloaded from Shuttle Radar Topography Mission Data.

Death simulation for Wenchuan earthquake

Population size simulation

The evaluation results of territorial functional suitability (Fan et al., 2019) (The type and scale of territorial space adaptation development, based on land, water, environment, disasters, population gathering capacity, development status of urban areas, and economic development level, which has been used to guide the layout of industries and populations in China from 2011) show that of the 37 counties in the core affected area of the Wenchuan earthquake, 17 were urbanisation areas, 7 were major agricultural production areas and 13 were key ecological function areas. The population and land development intensity of urbanisation areas remain unchanged from that in the 2007 population data. The intensity of land development in major agricultural production areas was 40% of that in urbanisation areas, while in key ecological areas it was 15% (Fan et al., 2019). Based on the ratio of population and land development intensity, the population numbers of the main agricultural and ecological areas were re-fitted as simulated populations.

Simulation of the number of deaths

To ensure the consistency of vulnerability in the simulation, GDP per capita, percentage of population aged between 15 and 65, percentage of male residents, percentage of employed, and number of medical institutions per km2 in 2007 were selected to construct vulnerability indicators (Intentional Strategy for Disaster Reduction, 2004; Liu et al., 2017). A Bayesian network was constructed using the number of deaths as the parent node, and the simulated population numbers, seismic intensity and vulnerability indicators as the child nodes (Jensen and Nielsen, 2007) (Supplementary Table 1). Based on the actual number of deaths in each county during the Wenchuan earthquake, the conditional probability of each node was determined by the Expectation-Maximisation algorithm (Lauritzen, 1995). Finally, on the basis of the given conditional probability, the possible death toll of each county subjected to the Wenchuan earthquake intensity under the simulated population was calculated (Supplementary note 1).

Vulnerability curve of different housing structure types for the Ludian earthquake

The main data for the Ludian earthquake simulation were pre-quake housing distribution and structure data, a seismic intensity map, and post-quake housing damage data. House structure consisted of four types: steel-concrete, brick-concrete, brick-wood, wood-and-earth. Housing damage was divided into four categories: collapse, severely damaged, slightly damaged, and no damage. A simple random sampling method with a sampling ratio of 10% was used to determine the damage to buildings of different structure types in different seismic intensity areas.

The inundation area simulation for Zhengzhou rainstorm

Calculation of 100-year return period precipitation

The annual maximum daily precipitation and annual cumulative maximum precipitation for three consecutive days during 1960–2020 at the Zhengzhou meteorological station were selected. The exceedance probability curves of daily maximum precipitation and cumulative maximum precipitation for three consecutive days were calculated by the information diffusion method (Liu et al., 2013) (Supplementary note 2). The precipitation that corresponded to the 1% exceedance probability was 100-year return period precipitation.

Inundation depth simulation

The inundated area was simulated using a high-performance hydrodynamic model (HiPIMS) (Ming et al., 2020) (Supplementary note 3). The model is based on the full version of 2D Shallow Water Equations, and dynamically simulates water depth and velocity between different grid cells. It is a fully physically based model, capable of modelling extreme or unprecedented events. For fluvial flooding, HiPIMS takes inputs of rainfall time series across a spatial domain, and produces inundation depth and velocity on each grid cell in each computing time step. The model was implemented in Zhengzhou at a 5 m spatial resolution over a 930 km2 domain. The high-resolution inundation maps produced by the HiPIMS model allowed assessment of impacts at a local level.

Results

Increased exposure due to unscientific planning nearly doubled the death toll in the Wenchuan earthquake

An 8.0 magnitude earthquake struck in Wenchuan County, Sichuan Province on May 12, 2008. It affected 46.24 million people, and left nearly 100,000 dead or missing (Cui et al., 2011). One of the main reasons for the huge death toll was that a large proportion of the population lived near earthquake fault zones because of unscientific planning, which resulted in a large increase in exposure. To test the effect of this excessive exposure, we introduced the evaluation results of territorial functional suitability. According to the land development intensity of the urbanisation area, major agricultural production area and key ecological function area as shown in the evaluation, we simulated reasonable population distribution in 2008. The actual population of the core area of the Wenchuan earthquake was 16.4084 million, and the simulated population was 12.1889 million, which only accounted for 74.28% of the former (Fig. 2). Of the five counties subjected to XI intensity, Pengzhou and Dujiangyan were urbanisation areas, and their simulated total population was consistent with their actual one. Wenchuan, Beichuan and Pingwu were key ecological function areas, whose actual population ranged from 0.1 to 0.3 million, while the simulated one was less than 0.1 million. The total simulated population of the three counties was almost 70% lower than the actual one, which shows that a large number of people were exposed to high-intensity areas due to unscientific planning.

a, b Population distribution during the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. a Actual population. b Simulated population under scientific planning. c, d 2008 Wenchuan earthquake death toll distribution. c Actual death toll. d Simulated death toll under scientific planning. e Wenchuan earthquake seismic intensity map.

A Bayesian network was used to simulate casualties in the simulated population under scientific planning during the Wenchuan earthquake. A comparison of simulated casualties with actual deaths is shown in Fig. 2. In the 17 urbanisation counties whose total population was not adjusted, the simulated death toll was consistent with the actual one, so the simulation results of the model verifiably reflected the actual losses of the disaster. In the core affected area of the earthquake, the actual death toll was 77,530, but the simulated death toll was only 39,901. With the same vulnerability and hazard intensity, increased exposure due to unscientific planning nearly doubled the death toll in the Wenchuan earthquake. In the simulation, the number of counties with more than 10,000 deaths dropped from three (Beichuan, Mianzhu, and Wenchuan) to one (Mianzhu). Mianzhu is an urbanised area, and its simulated population is consistent with its actual one; the number of simulated deaths is therefore consistent with the actual number. In Wenchuan and Beichuan, the number of simulated deaths decreased significantly compared with the actual one, due to the reduction in the simulated population. We can therefore see that excessive exposure due to unscientific planning was the main cause of mass deaths in the Wenchuan earthquake.

High vulnerability caused by low socio-economic level increased the disaster losses of the Ludian earthquake more than tenfold

On 3 August 2014, a 6.5 magnitude earthquake occurred in Ludian County, Zhaotong City, Yunnan Province (Wei et al., 2017). The earthquake caused direct economic losses in housing damage of 12.82 billion yuan. This included the collapse of 86,282 rural homes and serious damage to 121,516 in the core affected area. Houses with steel-concrete and brick-concrete structures accounted for 0.1% and 1.8% respectively of collapsed and severely damaged houses. Other structures such as brick-wood and wood-and-earth accounted for 98.1%. The low socio-economic level of residents in this region means that the earthquake resistance of their houses cannot be effectively improved. The majority of houses were wood-and-earth structure, which is extremely vulnerable to natural disasters. This vulnerability accounted for the high number of houses that collapsed in the region during the 6.5 magnitude earthquake. To test the effect of high vulnerability caused by a low socio-economic level on the overall losses in the region, we fitted the collapse and damage rates of buildings for different structure types in different seismic intensity areas, combined with the field investigation results in the Ludian post-disaster statistical report (Fan et al., 2016).

The results are shown in Fig. 3. In the IX intensity zone, the collapse rate was 8.90% for steel-concrete structures, 30.45% for brick-concrete structures, and 80.21% for wood-and-earth structures. The loss rate of wood-and-earth structures was 9.01 times that of steel-concrete structures, and 2.63 times that of brick-concrete structures. In the VIII intensity zone, the collapse rate of steel-concrete structures was 0, while that of wood-and-earth structures was 55.52%. This implies that if the buildings in this area were upgraded to steel-concrete structures, the collapse rate of houses would be reduced by at least 90%. Consequently, high vulnerability caused by low socio-economic level can be considered the root cause of the large number of house collapses in the Ludian earthquake.

Increased hazard intensity caused by anthropogenic climate change resulted in a 1.44-times expansion of the area severely affected by the Zhengzhou rainstorm

As a result of anthropogenic climate change, in July 2021 Zhengzhou was hit by a rainstorm of rare intensity, which caused severe flooding (Zhao et al., 2022). On 19 July, the single-day precipitation reached 552.5 mm, and the 3-day process precipitation from 17th to 20th July was 617.1 mm. The single-day precipitation was the highest recorded level in the Zhengzhou meteorological station’s 70-year history. To test the effect of increased hazard intensity caused by anthropogenic climate change on disaster losses, we used the 1960–2020 historical precipitation data to simulate 100-year return period precipitation in this region (China’s highest urban standard for flood prevention is based on 100-year return period precipitation). The simulation results showed the single-day precipitation in the core area was 180.50 mm, which was one third of the actual precipitation. The 3-day process precipitation was 240.80 mm, less than half the actual precipitation (Fig. 4).

a, b The exceedance probability curves of precipitation. a Daily maximum precipitation. b Cumulative maximum precipitation for three consecutive days. The horizontal axis is precipitation value, and the vertical axis is exceedance probability, i.e., the probability of precipitation being greater than or equal to a given value. c, d The inundation depth distribution in Zhengzhou. c Inundation depth of actual precipitation. d Inundation depth of 100-year return period precipitation.

A hydrodynamics model was used to further simulate the inundation area in Zhengzhou. The results are shown in Fig. 4. The total influence area (i.e., area with an inundation depth of more than 0.2 m) of actual precipitation (229.64 km2) was 34.46 km2 more than that of the 100-year return period precipitation (195.18 km2). In the area with an inundation depth of 0.2 m to 1 m, the inundation area of 100-year return period precipitation was 122.15 km2, which was consistent with that of the actual precipitation (126.42 km2). In areas where the inundation depth was greater than 1 m, the actual affected area was much larger than that of 100-year return period precipitation. When the inundation depth was over 2 m, the inundation area of 100-year return period precipitation was 26.71 km2, which was 67.2% of that of actual precipitation. In places where the inundation depth was 1–2 m, the inundation area of 100-year return period precipitation was 46.31 km2, which was 70.7% of that of actual precipitation. In total, the area with an inundation depth of more than 1 m of actual precipitation was 1.44 times larger than that of 100-year return period precipitation. In addition, areas with an inundation depth of more than 1 m incurred the most serious losses. It can therefore be assumed that if exposure and vulnerability remain unchanged, an increase in hazard intensity will significantly enlarge the area affected by a disaster, and increase the losses it incurs.

Discussion

Unreasonable human behaviours are an inevitable outcome of societal development

Based on the above case analysis, we divided the human behaviours that lead to the amplification effect of natural disasters into three categories, and further explored the root causes of these human behaviours according to the characteristics of societal development when each case occurred.

The first category is behaviours caused by insufficient risk cognition or ignorance of disaster risk, which manifest mainly in times of rapid industrialisation and urbanisation (Collins, 2018; Raikes et al., 2021). This kind of expansion requires a large amount of land and other resources, and in the process, humans tend to pursue economic interests and ignore the risk of natural disasters. This in turn induces a series of unreasonable behaviours with environmental consequences, e.g., resource exploitation activities that lead to major mining accidents; the filling of lakes and flattening of mountains to expand agricultural or construction land, which causes floods and landslides; and unscientific urban planning, which blindly gathers people in high-risk areas (Lavell and Maskrey, 2014; Hallegatte et al., 2017). In 2008, Wenchuan was in a stage of rapid urbanisation and population growth. As land resources were limited, the local government ignored the disaster risk and housed a large number of people around an earthquake fault zone. The 2010 Zhouqu mudslide is also a typical example: 1557 people died because unreasonable human behaviours converted a mudslide-prone area into construction land (Xiang et al., 2011).

The second category is behaviours caused by inadequate coping ability, i.e., there is an awareness of the existence of a disaster risk, but insufficient economic, scientific or technological resources mean that effective preventive measures cannot be taken, and a series of unreasonable behaviours occur (Dadson et al., 2017; Hallegatte et al., 2020). The specific manifestation is that building design and construction standards cannot meet disaster prevention requirements. This behaviour is particularly prominent in less-developed societies. In this stage, poverty forces individuals in high disaster risk areas to focus on obtaining the bare essentials, such as food and clothing. These people do not have the extra capacity to take necessary disaster prevention measures, and this magnifies vulnerability factors and increases disaster losses. In 2014, Ludian was one of the poorest areas in China, with an average rural income of just 4300 yuan (less than half of rural China’s 2013 average annual income) (Yunnan Provincial Bureau of Statistics, 2014). Most local farmers could only afford food and clothing, and earthquake-resistant houses that cost 100,000–200,000 yuan were entirely out of reach. In addition, local government finances were strained, leaving authorities little money to subsidise housing improvements for their 4.1 million rural residents. Correspondingly, Ludian’s relatively affluent urban area was almost unaffected by the 2014 earthquake (Fan et al., 2016).

The third category is behaviours induced by a lack of certainty in the decision-making process, when dealing with low-probability but high-intensity extreme disaster events. These behaviours occur most often in areas with a relatively developed economy, and stable urbanisation (Zhao et al., 2022). Climate change has meant that extreme weather events have become more frequent and more intense, and in many cases they have exceeded the disaster preparedness standards of the cities in which they occurred (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2012). For these cities to improve their disaster protection standards, and upgrade their infrastructure to accommodate the increasing intensity of extreme events, a large-scale risk prevention investment needs to be made. This will inevitably lead to a change in local economies, and the perceived waste of certain resources. It is difficult to conduct an accurate risk prevention cost and benefit assessment for low-probability, high-intensity extreme events, because they are by nature hard to predict (Mechler et al., 2014). Consequently, most regions have not increased their spending on prevention strategies, or formulated emergency plans, and this has led to the amplification of losses in extreme disaster events. In 2021, although Zhengzhou’s urban development was relatively stable, the city did not update its flood prevention standards and emergency plan to accommodate extreme events. The precipitation it experienced in 2021 was three times that of the 100-year return period precipitation. Owing to the lack of an emergency plan, the government, enterprises and individuals were not able to respond to the disaster in time, and consequently incurred substantially higher losses. China’s 2008 snowstorm, which knocked out large parts of the power grid, is another case in point (Wei et al., 2020).

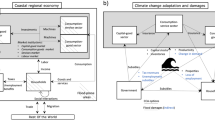

An extended disaster risk framework that includes unreasonable behavioural factors and a disaster mechanism

Appropriate human behaviours can mitigate the effects of natural disasters, while unreasonable ones can amplify them. If governments, enterprises and individuals behave unreasonably, they magnify disaster losses by increasing hazard, vulnerability and exposure intensity. Based on the cases analysed, we constructed an extended disaster risk framework, including unreasonable behavioural factors and a disaster mechanism, as shown in Fig. 5.

a Less-developed stage. b Relatively developed stage of dealing with normal disasters. c Relatively developed stage of dealing with extreme disaster events. The brown arrow represents the effect of driver factors on human behaviour stakeholders; the red arrow represents the magnifying effect of human behaviour stakeholders on the three components of disaster; the blue arrow represents the interaction between the various stakeholders of human behaviours; and the green arrow represents the influence of behaviour stakeholders on driver factors.

Governments often play a major role, because they have a certain amount of control over human behaviours, especially in less-developed societies (Raikes et al., 2021). In this stage, the disaster prevention is largely government-led, and the authorities guide the behaviours of enterprises and individuals when dealing with natural disasters (Djalante, 2012). The human behaviours that increase disaster losses in less-developed societies are, therefore, mainly a result of governmental ignorance of disaster risk and a lack of coping ability. The unreasonable behaviours of the government will guide enterprises and individuals to conduct related unreasonable behaviours, which further aggravate the amplifying effect on disaster losses (Fig. 5a). The intervention of external forces—such risk perception arbitration by higher levels of government, and economic and technological assistance—can often reduce the occurrence of these unreasonable behaviours.

The ability of enterprises and individuals to prevent and reduce disaster risk has been continuously enhanced with societal progress. When a society becomes more developed, the government’s guidance of the behaviours of enterprises and individuals gradually weakens (Djalante, 2012). At this stage, when faced with normal disasters (non-extreme disaster events), the role of government is usually to reduce risk. Because of the difference in risk cognition or prevention capacity caused by the gap between socio-economic levels, some enterprises and individuals will conduct a series of unreasonable behaviours that contradict the government’s aims (Dadson et al., 2017). These are the behaviours that are most responsible for increased losses from normal disasters in relatively developed societies (Fig. 5b). Support and guidance from the government to enterprises and individuals play a key role in controlling these unreasonable human behaviours.

When extreme disaster events occur, the lack of certainty in the decision-making process is the behavioural driver of losses. Once the government fails to upgrade disaster prevention infrastructure, enterprises and individuals will also ignore the risks (Djalante, 2012). This whole-society neglect will inevitably increase the losses caused by extreme events. If the government chooses to comprehensively upgrade disaster prevention facilities, it will, however, cause a perceived waste of certain resources (Mechler et al., 2014). At this stage of development, the government should therefore actively guide enterprises and individuals to build a disaster prevention, mitigation and relief system with the participation of the whole society. This way, the cost of disaster prevention is shared, and the area can respond effectively to extreme events. External assistance should focus on risk transfer (to reduce the investment cost of disaster prevention), and relief for local governments (Fig. 5c).

Conclusion

This paper quantitatively analysed the amplification effect of unreasonable human behaviours on disaster losses caused by increased levels of hazard, vulnerability and exposure, and explored the root causes of these unreasonable behaviours. Through simulation scenarios of the Wenchuan and Ludian earthquakes and the Zhengzhou rainstorm, it found that unreasonable human behaviours have a significant impact on disaster losses, and have even been an important cause of some catastrophes. In different stages of social development, the increase of disaster losses caused by unreasonable human behaviours varies in its dominant factors, and its mechanism and degree of influence. On the basis of these differences, we constructed an extended disaster risk framework, including unreasonable behavioural factors and a disaster mechanism. Regions can use this framework to continuously optimise their disaster prevention and mitigation systems in light of their current social development characteristics, and actively reduce the amplification effect of human behaviours on disasters.

In areas with relatively underdeveloped economies, the focus of external assistance and governmental poverty alleviation should be shifted to disaster prevention and reduction. The ability of the community to withstand disasters should be enhanced by strengthening infrastructure such as housing, and raising disaster prevention awareness among the public. The focus should be shifted from post-disaster relief to pre-disaster prevention, so as to stop these areas from falling into poverty as a result of a natural disaster.

In less-developed areas with rapid urbanisation, it is important to carry out multi-scale disaster risk assessment to identify risk areas, and to strengthen understanding of these risks. Disaster prevention and mitigation should be included in economic development and population development plans (Smith et al., 2019; Biggs et al., 2021). The lack of fundamental scientific and technological resources in some less-developed areas means that there is no reliable data to support effective urban planning. The focus of external assistance at this stage should therefore be to strengthen the capacity of scientific and technological disaster prevention support.

In relatively developed areas, disaster prevention facilities are usually relatively complete, and low-probability, high-intensity extreme events are the disasters with the biggest impact. Owing to the low probability of these extreme events, however, excessive investment in disaster prevention and mitigation will waste resources to an extent. Risk prevention in these areas should therefore focus on territorial space planning, to form a solid foundation for disaster prevention. In addition, the role enterprises and individuals play in disaster prevention, mitigation and relief should be actively brought into play, and related policies should be improved with the involvement of society as a whole.

Data availability

Socio-economic data for the Wenchuan earthquake—including GDP, population (population size), age (age structure), gender (gender ratio), social dependency (employed), and medical facilities (number of medical institutions)—was collected from the 2008 Sichuan statistics yearbook. The number of deaths for the Wenchuan earthquake was collected from the Wenchuan post-disaster statistical report. Housing data for the Ludian earthquake including pre-quake housing distribution data, post-quake housing structure data, a seismic intensity map, and post-quake housing damage data, was collected from the Ludian post-disaster statistical report. Meteorological data for the Zhengzhou storm was collected from the Zhengzhou meteorological station. The Zhengzhou digital elevation model (DEM) is available at https://srtm.csi.cgiar.org/srtmdata/. All data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Aerts JCJH, Botzen WJ, Clarke KC et al. (2018) Integrating human behaviour dynamics into flood disaster risk assessment. Nat Clim Change 8:193–199

Alexander D (1993) Natural disasters. UCL Press, London

Biggs J, Ayele A, Fischer TP et al. (2021) Volcanic activity and hazard in the East African Rift Zone. Nat Commun 12:6881

Brown K, Westaway E (2011) Agency, capacity, and resilience to environmental change: lessons from human development, well-being, and disasters. Annu Rev Environ Resour 36:321–342

Ciscar JC, Rising J, Kopp RE et al. (2019) Assessing future climate change impacts in the EU and the USA: insights and lessons from two continental-scale projects. Environ Res Lett 14:084010

Collins AE (2018) Advancing the disaster and development paradigm. Int J Disaster Risk Sci 9(4):486–495

Cui P, Chen XQ, Zhu YY et al. (2011) The Wenchuan Earthquake (May 12, 2008), Sichuan Province, China, and resulting geohazards. Nat Hazards 56:19–36

Dadson S, Hall JW, Garrick D et al. (2017) Water security, risk and economic growth: lessons from a dynamical systems model. Water Resour Res 53(8):6425–6438

Djalante R (2012) Adaptive governance and resilience: the role of multi-stakeholder platforms in disaster risk reduction. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 12:2923–2942

Fan J, Zhou C, Gu X, Deng W, Zhang B (eds.) (2009) National post-Wenchuan earthquake reconstruction plan-evaluation of resources and environment carrying capacity. China Science Publishing & Media Ltd, Beijing

Fan J, Lan H, Zhou K (eds.) (2016) Restoration and reconstruction after the Ludian earthquake—evaluation of resources and environment carrying capacity and research on sustainable development. China Science Publishing & Media Ltd, Beijing

Fan J, Wang Y, Wang CS et al. (2019) Reshaping the sustainable geographical pattern: a major function zoning model and its applications in China. Earths Future 7:25–42

Hallegatte S, Vogt-Schilb A, Bangalore M et al. (2017) Unbreakable: building the resilience of the poor in the face of natural disasters. World Bank, Washington

Hallegatte S, Vogt-Schilb A, Rozenberg J et al. (2020) From poverty to disaster and back: a review of literature. Econ Disasters Clim Change 4:223–247

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2012) Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation. Cambridge Univ Press, Cambridge

Intentional Strategy for Disaster Reduction (2004) Living with risk. A global review of disaster reduction initiatives. United Nations publication, New York

Jensen FV, Nielsen TD (2007) Bayesian networks and decision graphs, 2nd ed. Springer, New York

Kates RW (1978) Risk assessment of environmental hazard. Wiley, New York

Kellens W, Terpstra T, De Maeyer P (2013) Perception and communication of flood risks: A systematic review of empirical research. Risk Anal 33:24–49

Lauritzen SL (1995) The EM algorithm for graphical association models with missing data. Comput Stat Data Anal 19(2):191–201

Lavell A, Maskrey A (2014) The future of disaster risk management. Environ Hazards 13(4):267–280

Liu B, Siu YL, Mitchell G et al. (2013) Exceedance probability of multiple natural hazards: risk assessment in China’s Yangtze River Delta. Nat Hazards 69(3):2039–2055

Liu B, Siu YL, Mitchell G (2017) A quantitative model for estimating risk from multiple interacting natural hazards: an application to northeast Zhejiang, China. Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess 31:1319–1340

Mechler R, Bouwer LM, Linnerooth-Bayer J et al. (2014) Managing unnatural disaster risk from climate extremes. Nat Clim Change 4:235–237

Ming X, Liang Q, Xia X et al. (2020) Real-time flood forecasting based on a high-performance 2D hydrodynamic model and numerical weather predictions. Water Resour Res 56:e2019WR025583

Pielke R (2019) Tracking progress on the economic costs of disasters under the indicators of the sustainable development goals. Environ Hazards 18:1–6

Raikes J, Smith TF, Baldwin C et al. (2021) Linking disaster risk reduction and human development. Clim Risk Manag 32:100291

Sichuan Provincial Bureau of Statistics (2008) 2008 Sichuan statistics yearbook. China Statistics Press, Beijing

Slovic P (2000) The perception of risk. Earthscan Publications Ltd, London

Smith A, Bates PD, Wing O et al. (2019) New estimates of flood exposure in developing countries using high-resolution population data. Nat Commun 10:1814

Stuart-Smith RF, Roe GH, Li S et al. (2021) Increased outburst flood hazard from Lake Palcacocha due to human-induced glacier retreat. Nat Geosci 14:85–90

Thieken AH, Cammerer H, Dobler C et al. (2014) Estimating changes in flood risks and benefits of non-structural adaptation strategies: a case study from Tyrol, Austria. Mitig Adapt Strateg Global Change 21:343–376

Tierney K (2014) Social roots of risk: Producing disaster, promoting resilience. Stanford University Press, Stanford

Ward PJ, Blauhut V, Bloemendaal N et al. (2020) Review article: natural hazard risk assessments at the global scale. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 20:1069–1096

Wei B, Nie G, Su G et al. (2017) Risk assessment of people trapped in earthquake based on km grid: a case study of the 2014 Ludian earthquake, China. Geomat Nat Haz Risk 8(2):1289–1305

Wei L, Qiu Z, Zhou G et al. (2020) Rainfall interception recovery in a subtropical forest damaged by the great 2008 ice and snow storm in southern China. J Hydrol 590:125232

Wilhelm B, Rapuc W, Amann B et al. (2022) Impact of warmer climate periods on flood hazard in the European Alps. Nat Geosci 15:118–123

Willner SN, Levermann A, Zhao F et al. (2018) Adaptation required to preserve future high-end river flood risk at present levels. Sci Adv 4:eaao1914

Wisner B, Blaikie P, Cannon T et al. (2004) At risk: natural hazards, people’s vulnerability and disasters, 2nd ed. Routledge, London

Xiang WN, Stuber RMB, Meng X (2011) Meeting critical challenges and striving for urban sustainability in China. Landscape Urban Plan 100(4):418–420

Yunnan Provincial Bureau of Statistics (2014) 2014 Yunnan statistics yearbook. China Statistics Press, Beijing

Zhao X, Li H, Qi Y (2022) Are Chinese cities prepared to manage the risks of extreme weather events? Evidence from the 2021.07.20 Zhengzhou Flood in Henan Province. Available at https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4043303. Accessed 15 March 2022

Acknowledgements

This research is jointly funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Project (grant 42230510) and China’s Second Scientific Research Project on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau (grant 2019QZKK0401). We thank Professor Lindsay Stringer and Dr. Ke Huang for helpful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by the author.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by the author.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, J., Liu, B., Ming, X. et al. The amplification effect of unreasonable human behaviours on natural disasters. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9, 322 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01351-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01351-w

This article is cited by

-

Stabilising CO2 concentration as a channel for global disaster risk mitigation

Scientific Reports (2024)