Abstract

Achieving sustainable rural development is essential for countries worldwide to balance development between urban and rural areas; especially, sustainable social development is crucial. In the face of rapid urbanization in China, the withdrawal of rural homesteads (WRH) has become the core policy for attaining sustainable rural development. Compared with the literature that focuses on the economic or environmental impacts of the policy, few studies have evaluated how social sustainability is accomplished through such land-reform policies. Given the consensus that exploring sustainability emphasizes complex causal relationships between multiple dimensions, assessment models must further consider interdependencies. Based on Chinese expertise and perspective, this study proposes a hybrid multi-attribute decision analysis model to evaluate the contribution of WRH policies toward social sustainability. First, the Delphi method was used to build evaluation criteria covering four dimensions—the socio-ecological environment, social welfare, social equity, and social inclusion—and 20 criteria were based on the existing literature. Second, influential network relations maps (INRMs) were constructed based on the fuzzy decision-making trial and evaluation laboratory (DEMATEL), considering complex causal relationships between dimensions and criteria to further identify the key evaluation criteria for the social sustainability of the homestead exit policy. The results show that the five subdimensions are key to achieving sustainable social development through WRH. Based on our results, we propose certain policy recommendations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Social sustainability is a crucial part of a broader sustainability framework to address environmental and climate change risks (Eizenberg and Jabareen, 2017). Social Sustainability is an important aspect of sustainable development. However, the social sustainability of rural areas is often neglected, in contrast to the economic and environmental aspects (Chatzinikolaou et al., 2013). Rural areas are regional complexes with natural, social, and economic characteristics and multiple functions, such as production, life, ecology, and culture (Long et al., 2019). Rural sustainable development can be defined as development that improves the living standards and quality of life of residents while preserving and improving the natural environment and respecting local culture and history (Yigitcanlar and Kamruzzaman, 2015). Development in rural areas is a pressing concern because of the profound challenges of poverty and inequality in rural areas, with four out of five people living below the international poverty line (You and Zhang, 2017). Rural populations typically have limited access to education, healthcare, and other services. In some areas, these urban–rural disparities have led to rising rural discontent, social polarization, and unrest. In addition, current rural development strategies do not aim to protect natural ecosystems. The continued loss of forests and increased pollution are contributing factors to climate change and are widely recognized as causes of the increased frequency of zoonotic diseases, such as the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (Di Marco et al., 2020). Climate change has an even greater negative impact on agriculture and the rural economy. Although rural communities have always experienced cycles of growth and decline as they interacted with their external environment, rural decline is proceeding at a rapid rate worldwide owing to urbanization and industrial development (World Social Report, 2021).

China is the second most populous country in the world. In the past three decades, China has experienced unprecedented urbanization; the economic, spatial, and social patterns of rural areas have been transformed, and the quality of rural living has greatly improved (Chen et al., 2022). However, the imbalance between urban and rural development and the lack of rural development have forced labor, talent, land, finance, and investment to move from rural to urban areas (Li et al., 2010). This has led to a brain drain, depopulation, the spread of hollow villages, and the abandonment of farmland (Ye and Christiansen, 2009; Long et al., 2016; Liu, 2018). In recent years, the Chinese government’s rural revitalization initiatives have improved the quality of life of rural residents. In terms of the four objectives of rural revitalization, rural land consolidation played a more positive than negative role. Among these, there are positive effects on farmers’ livelihoods and industrial prosperity (Yin et al., 2022). However, many social problems are still not effectively solved (Guo and Liu, 2021; Liu et al., 2018). First, as the rural population decreases, both the bonding and bridging aspects of social capital become more vulnerable. In this process, villages tend toward individualism, lose social cohesion, and become socially and economically isolated (Liu and Li, 2017). Second, as the social structure of rural areas changes, the absence of rural residents leads to the degradation of the function of rural land (Jian-Rong, 2001). Finally, the income of rural residents is much lower than that of urban residents. Therefore, public services, healthcare systems, educational systems, cultural and recreational activities, and social security systems tend to be poorer in rural areas (Shayo et al., 2016; Saleh, 2015a). In conclusion, as the environmental quality of rural areas continues to decline (Aguilera et al., 2018), rural hollowing-out, agricultural marginalization, and population aging hinder the advancement of urban–rural integration and the overall development of a well-off society (Long, 2014; Yang et al., 2015; Long and Tu, 2018).

The withdrawal of rural homesteads refers to a type of land transfer involving rural construction land, where farmers give up their land use rights completely to obtain better compensation for their benefits (Zhou et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2022). The Withdraw of Rural Homestead policy (WRH) transforms rural land from a resource to an asset by unlocking the economic potential constrained by complex property rights structures (Song et al., 2021; Hu et al., 2023). The WRH is an essential part of China’s rural land reform and is a core strategy for sustainable rural development in China (Kong et al., 2018). It has multiple important functions, such as rebuilding urban and rural spaces, optimizing land use in rural areas, guaranteeing food security, coordinating urban and rural development, ensuring intensive and scientific use of resources, and improving the human living environment. This contributes to the harmony, stability, and sustainable development of the region (Long et al., 2010). The WRH is central to addressing the long-standing neglect of the capital and asset attributes of land in rural China and strengthening the anti-poverty role of land, which contributes to the achievement of sustainable rural development. Many studies have focused on the institutional reform of WRH (Cao et al., 2019) and argued that exit and compensation mechanisms for WRH are key to achieving sustainable rural development (Huang et al., 2014; Liang et al., 2022). However, few studies have focused on how home-based policies can achieve socially sustainable development, particularly WRH policies involving land transfer, to promote sustainable rural livelihoods and community building. These policies ultimately aim to achieve participation, sharing, and equitable distribution. There is a lack of evaluation indicators to assess how WRH achieves social sustainability. Moreover, although scholars have used hierarchical analysis (AHP) to evaluate agricultural sustainability and rural environmental quality (Zand et al., 2020), this approach does not consider the interdependence among indicators, which is a particularly important feature of sustainable development. Ignoring this component is likely to result in inaccurate decision-making.

How successful is the WRH in implementing sustainable rural social development? What criteria should be considered during policy evaluation? Which dimensions are the key contributors? These are the core research questions of the present study. WRH is centered on land use policy; therefore, its evaluation framework needs to be developed with similar objectives (comprehensive) as the rural revitalization program but should be more focused on social sustainability and land policy analysis. Based on the academic literature on sustainable rural development, we selected indicators applicable to the evaluation of WRH programs. We further assessed the direction and level of interaction between each dimension. Dimensions are sub-categories under the evaluation framework; for the dimensions in this study, the criteria or sub-criteria (or domains/sub-domains) are considered important and interact with each other in the evaluation system. Moreover, the degree of the influence of each variable may vary. In other words, each domain has its own influence or weight.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section “Literature review” presents a review of relevant literature and the development of our model. The section “Materials and methodology” describes our research methodology in detail. Results are presented in Section “Fuzzy dematel”. Finally, the Section “Discussion” provides a brief conclusion and policy recommendations.

Literature review

Current status of research on sustainability assessment in rural societies

Objective measurement tools are necessary to determine the ability of rural sustainable development projects to achieve their objectives. Several indicators have been proposed for measuring human social development. Examples include the Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare (ISEW), the Sustainable Net Benefit Index (SNBI), and the Composite Welfare Indicator (SWI) (Daly and Cobb, 1989; Beça and Santos, 2010). Espina and Arechavala (2013) pointed out that, although material wealth and social service capacity are the most fundamental aspects of social development outcomes, they are not sufficient to fully assess the quality of development. Currently, the tools and metrics used to promote sustainable community development are biased toward environmental sustainability. Municipalities have begun to experiment with composite indices (e.g., “social indices”) that integrate social dimensions (Colantonio et al., 2009). However, for municipalities and so-called “open space” areas (which can be considered a type of rural area), policies tend to take a narrower view of sustainable development (Šimková, 2008). These policies must be formulated so that their outcomes are measurable, not only to determine whether goals have been reached but also to allow for a degree of adaptability that enables policymakers to abandon goals that are no longer relevant and strengthen those applicable to arising challenges (Abreu and Mesias, 2020).

Despite the proliferation of development indicators, tools for evaluating homestead exit policies are lacking. These issues are complex because they involve multiple dimensions and levels of analysis, and sustainable development indicators should characterize goals quantitatively and offer a means of summarizing key criteria (Oerther, 2019; Nguyen et al., 2019; Kiselitsa et al., 2018, Gorlachuk et al., 2018). For example, the rural development index constructed by Kageyama (2008) to measure the effectiveness of public policies for rural development is characterized by the fact that the aggregation of different indicators is additive (i.e., it relies on the simple arithmetic mean of four dimensions). Constantin et al. (2015) used the concept of vulnerability to classify rural issues as territorial, demographic, economic, or environmental. Based on the vulnerability level in each dimension, integrated projects can be developed and implemented to reduce vulnerability and achieve sustainable development. Other scholars have used geometric means to construct rural development indices to avoid the substitution effect, which could result in a high score in one dimension (Abreu et al., 2014). These indicators were grouped into four dimensions: demographic, economic, social, and environmental. They have the advantage of incorporating indicators related not only to economic and demographic aspects but also to social criteria that are highly relevant to policy. However, there have been no studies on evaluation indicators based on the WRH.

Constructing a WRH evaluation system to promote sustainable social development

The goals of sustainable development, as stated in the report “Our Common Future,” should be peace, security, development, and the environment (Brundtland, 1987). Previous studies, however, have prioritized the sustainable performance of rural development in terms of climate change and economic development, and the need for social development in rural areas has received considerable attention (Grundmann and Stehr, 2010; Chan and Lee, n.d.). An important feature of social sustainability is equity, fairness, and participation in the decision-making and implementation process of regeneration projects, and the social needs of rural development policies and construction projects are equity, participation, sustainability awareness, and social cohesion (Murphy, 2012). In addition, the sustainable development of rural societies aims to reduce disparities in the welfare and health of citizens and improve the living conditions and social status of the most vulnerable groups in society (de Andrade et al., 2015). Therefore, the social performance of rural construction projects is crucial for their success and social sustainability. However, there is a lack of a systematic framework for assessing the social performance of construction projects. In addition, existing methods are time-consuming and subjective to a certain degree (Xiahou et al., 2018).

A key challenge in framing a social sustainability assessment framework lies in the interface synergy and tradeoffs between its dimensions. A triadic model with intertwined ecological, economic, and social dimensions is required for sustainable development assessments (Hopwood, 2005). In a related application, rural sustainable development—the social sustainability of a region—is measured by constructing measures of the environment, equity, well-being, and inclusiveness. This study proposes an evaluation system based on the relevant literature to assess how rural homesteads contribute to sustainable social development. Each of the four dimensions is composed of sub-dimensions or criteria, as presented in Table 1.

The socio-ecological environment dimension aims to emphasize the improvement of rural ecology and rural livability, and to mitigate villagers’ out-migration by improving the natural and rural living environments, thus achieving sustainable social development (Peters, 2013). Second, the social welfare dimension provides citizens with quality welfare and meets various social needs, such as enhancing their subjective well-being (Leung et al., 2013; Fitouss et al., 2011). This dimension aims to provide investments in public infrastructure and social services to improve villagers’ quality of life and promote the sustainable development of developing societies (Eberts, 1986; Xu et al., 2023). The third dimension is social equity, which is designed to improve villagers’ access to infrastructure and public services and expand social protection in rural areas (Xu et al., 2022). Bigdeli Rad and Maleki (2020) argued that improving safety, education, social participation, population, health, leisure, social responsibility, satisfaction with services, and a sense of belonging to a place are social dimensions of sustainable development. Finally, social inclusion is one of the main objectives of the WRH policy (Farrington and Farrington, 2005). These guidelines improve existing rural social networks, including vulnerable groups, and negatively affect the living environment (Zheng et al., 2017). In addition, the retention and development of cultural programs reduce social exclusion, increase the well-being of urban residents, and encourage participation in community life (Evans, 2005). This dimension contributes to social sustainability by mitigating internal social inequalities and excluding vulnerable groups.

Therefore, an evaluation system based on the four dimensions related to the criteria is described as follows:

Socio-ecological environment (D 1)

The natural environment impacts social sustainability, as farmers today have higher expectations for quality of life in terms of their living environments and support facilities. Beautiful, clean, and healthy villages are thus not only the new goal of current rural habitat management but are also key to WRH, which has improved the rural living landscape alongside social productivity (Wang et al., 2019). Therefore, farmers have higher expectations for a higher quality of life, a suitable living environment, and perfect supporting facilities and expect to have beautiful and livable villages. The lack of sustainable management measures for the residential land of rural residents has led to many negative phenomena in more underdeveloped rural areas, including a scattered and disorganized village layout, the decline of local cultural identity, and the unsightly appearance of villages (Du et al., 2014). The living environment, quality of water resources, air quality, sanitation, and safety of the habitat on which they depend are the basis for livability. Thus, the planning and layout of residential sites should take into account the local natural ecological system, socio-cultural environment, and regional spatial environment (Faiz et al., 2012; Qu et al., 2017).

In recent years with the increase of urbanization, rural areas have attracted entrepreneurs to open factories. These provide employment for farmers and boost the local economy; however, the expansion of homesteads and the construction of factories have led to new problems, such as environmental damage and high energy consumption. There is a link between energy consumption and the built environment of a village, as house sites affect the energy consumption of the area. Studies have found that people are less likely to own a car if they live in a high-density built environment; therefore, a well-designed built environment can reduce travel energy consumption (Zarghami et al., 2017). In addition, as an inherent feature of sustainable development, the reuse of residential building stock may significantly reduce the environmental burden over the next three decades. From the perspective of environmental performance, WRH retains recyclable materials from old buildings and avoids demolition and generating waste (Assefa and Ambler, 2017; Yung and Chan, 2012).

Thus, from a socio-ecological perspective, the quality of the Socio-ecological environment depends on (C1) improving water quality, (C2) improving air quality, (C3) improving sanitation, (C4) improving residential safety, (C5) enhancing landscape harmony, and (C6) adopting environmentally friendly building materials.

Social welfare (D 2)

WRH also improves the quality of life and happiness of villagers by considering their social welfare while improving the physical environment. The happiness of farmers is related to the harmony and stability of a country, especially in China, which has a rural population of more than 500 million. There is a positive correlation between happiness and sustainable development (Schimmel, 2009; Zidanšek, 2007); therefore, improving farmers’ happiness is one of the main tasks of rural development in China. Haller and Hadler (2006) argued that good social relationships can provide spiritual or material help to farmers, increase their self-esteem and self-confidence, and thus positively impact their subjective well-being. WRH builds and improves the functionality of rural communities, providing villagers with public resources such as high-quality public services. In addition, WRH enhances farmers’ well-being by integrating and planning rural land resources and using them for the construction and improvement of public facilities. After the implementation of WRH, a communication platform is established for the subsequent development planning of the village. WRH involves the individual interests of the villagers as well as the collective interests of the village. Individual interests relate to villagers’ rights, land property rights, personal health, welfare, and public services (Wang and Sun, 2016). Given that collective land ownership was abstract in China from 1978 to 2006, collectives were entitled to earn a certain amount of farmers’ agricultural income and use it to support village public welfare and construction. However, since the state abolished the agricultural tax in 2006, this collective income has disappeared. Consequently, collective rights to farmland have become extremely limited, leaving only the right to contract and supervise land, a phenomenon known as virtual or vacant collective ownership (Wang and Zhang, 2017). WRH policy recognizes farmers’ residential property rights and rights to land, which guarantees farmers’ basic interests in land property rights (Wang et al., 2018). The collective interest is the overarching goal of village development, where road planning and housing construction are related to the mobility of the village and the accessibility between villages and cities (Mosaberpanah and Khales, 2013). Well-planned transport routes can enhance economic development and village sustainability and have a beneficial impact on the community economy, while sustainable development of the transport sector can help the lower-income segments of the community to meet their transport needs (Mosaberpanah et al., 2012). In rural areas, houses are the basic structures in which villagers live, and their quality is related not only to the safety of farmers but also to the sustainability of the village. If the lifespan of a house is too low, it becomes costly in terms of rebuilding expenses and the waste of construction materials.

Thus, the quality of social welfare depends on (C7) enhancing happiness, (C8) enhancing village circulation, (C9) improving public service facilities, (C10) improving social welfare protection, (C11) securing housing property rights, (C12) increasing satisfaction with WRH policy, (C13) improving housing quality, and (C14) improving personal health.

Social equity (D 3)

Social sustainability is fundamentally related to distributive justice or social equity, which is an important component in creating a way of life accessible to all (Trudeau, 2018). The WRH aims to view sustainable rural social development as balancing economic, environmental, and equity interests; despite shifting priorities for social equity, persistent social inequalities persist between urban and rural areas. For example, hukou has been used to develop and implement discriminatory educational policies for migrant workers. Because of their rural hukou type, migrant workers do not have access to social services and social benefits despite paying taxes. Resident migrant workers who work in China’s cities but do not have local hukou (household registration) are widely regarded as vulnerable social groups in contemporary China (Chan, 2015). This group also includes lonely empty nesters (Jin et al., 2020).

Rural homesteads are both a resource and an asset with the dual attribute of representing collective and individual interests (Dong and Xiong 2019). The government, in promoting WRH, has paid attention to the subsequent livelihoods of dislocated farmers by adopting different exit models to support disadvantaged groups and protect the individual interests of farmers participating in WRH. The right to eligibility for home base allocation is a membership right (Tao et al., 2020) or derived from social security rights (Lu et al., 2020). The right to eligibility for home base allocation is acquired based on collective membership and is a status enjoyed by members of rural collective economic organizations (Jiang, 2019). It was found that the right to eligibility for home base allocation reflects the public contribution of home bases, and the security of eligibility as a social function is emphasized in the content of the right. Based on this identity privilege, farmers’ participation in the WRH process should be respected to ensure that farmers’ individual rights and interests are treated fairly.

Because these rights are designed for collective members to use collective building sites, it focuses on income and disposal. Collective members can obtain property rights certificates, extend security and mortgage rights, acquire the right to use the land for residential bases, and have the right to decide whether to transfer the right to use the land for residential bases while ensuring basic livelihood equity for farmers (Dong, 2018). Thus, the village government integrates collective resources to develop tourism, agriculture, and the real economy in the local area, and the evacuated residents are entitled to the proceeds obtained from their collective economy. The village collectives pay dividends to local villagers in order to reduce the gap between the rich and the poor in the area.

In addition, studies have confirmed the positive effect of homestead withdrawal on the educational advancement of school-age children (Shi et al., 2022), despite the problems of education financing over the past 40 years and the government’s commitment to improving human capital levels. However, rural students and schools lag behind their urban counterparts in this respect (Yue et al., 2018). China’s spending patterns favor urban students and schools, especially because of its focus on higher education. In preschools, the gap is greatest between urban and rural children, who receive the least funding (Luo et al., 2012). On the one hand, WRH makes it easier for the next generation in rural areas to transition into urban households and obtain the same treatment as urban residents for school-age children; on the other hand, WRH uses vacant land to build public facilities such as sanatoriums and medical centers and to bring educational resources to schools and libraries to improve the level of basic education resources. These public facilities also provide more opportunities for residents, thereby contributing to the sustainable development of rural societies.

The quality of social equity depends on (C15) supporting disadvantaged groups, (C16) improving the education level of residents, (C17) strengthening the livelihood of residents, (C18) narrowing the gap between the rich and the poor, and (C19) guaranteeing the compensation benefits of withdrawal.

Social inclusion (D 4)

To achieve social sustainability in rural areas, WRH is also concerned with the sustainability of communities or the continuation of community traditions, customs, and value systems (Han et al., 2021). Because rural urbanization has to some extent undermined rural residents’ attachment to the land, population movements may affect local residents’ sense of belonging, which is the process by which a person develops a sense of identity with their social, relational, and physical environment (Miller, 2003). The construction and transformation of communities that do not include foreign populations in their planning will not only increase the cost of community transformation but will also fail to promote community integration. WRH plans the location of houses throughout the countryside, organizing scattered houses into a residential area and reducing neighborhood distance in terms of geographic space. In addition, the application requirement for residential land in WRH states that villagers can apply for free residential land from the village committee with their local household registration, which increases the local villagers’ sense of belonging and attachment to the land as a matter of policy. Although the urban–rural dichotomy has had a very complex impact on rural China (Li and Hu, 2015), Western migration theory is still rich in information. Western explanations of immigrant integration mainly draw on perspectives of human capital characteristics (Branker, 2017), social networks (Van Meeteren et al., 2015), and institutional policies (Fix et al., 2001) around immigrants’ education level, work experience, social relations, and employment security. The community, as the key to WRH, provides a structured set of norms for community members. Through active participation in community activities, access to community services, and procedural involvement in decision-making, WRH gradually strengthens community identity (Ke and Ke, 2014). When communities become well-managed groups with the ability to implement practical value for their residents, they can give WRH a sense of belonging and thus help them to achieve re-socialization by integrating into the community and then into the city or countryside (Yin and Teng, 2022). Local communities’ awareness of the importance of heritage conservation is also crucial to educating future generations(Vázquez-Villegas et al., 2022). The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) defines tangible heritage as cultural heritage, including buildings, artifacts, and sites. Accents, folklore, and popular cultural heritage, including fashion and clothing and human habits, are considered intangible cultural heritage (Roslan et al., 2021). Gizzi et al. (2019) recognized the importance of cultural heritage in reuniting the community with the places and objects that belong to them in order to return to the value of the relationship between the site and its surroundings, informally understand the object and its symbolic meaning in the history of that community, and identify the connections that can repair the link between the individual and the social value of the cultural product. These functions encourage individuals in the community to be proactive in preserving cultural heritage for future generations (Qin and Leung, 2021). While preserving historical and cultural heritage, WRH integrates new homes into the local cultural characteristics, adding to the overall historical atmosphere and providing sufficient resources for the subsequent development of historical and cultural tourism. In addition, new technologies have been implemented in heritage education programs that preserve local cultural activities, including folk art and folklore activities. These programs enable students to identify and value their heritage (Billore, 2021). Sustainable development cannot be achieved without the inclusion and improvement of the well-being of rural populations as a central goal.

Thus, social inclusion depends on (C20) enhancing residents’ sense of belonging, (C21) enhancing social community integration, (C22) preserving local relics, (C23) preserving local cultural activities, and (C24) incorporating local cultural design.

Material and methodology

This study implements a two-stage approach. First, the appropriateness of the indicators is evaluated based on the index system proposed in the previous section combined with the modified Delphi method. Fuzzy DEMATEL is then used to explore the complex relationships among the dimensions and to propose improvement measures. A flow chart of this framework is presented in Fig. 1. Fuzzy Decision-making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory (DEMATEL) was introduced in 1971 at a conference in Geneva by Gabus and Fontela (Battelle Laboratories). It solves complex global decision problems by identifying causal relationships between various factors. It analyzes the importance of system factors based on graph theory and matrix tools (Fontela and Gabus, 1974).

Delphi criteria system

The Delphi method has been used in sustainability assessment studies to investigate the issues that need to be optimized in long-term natural, social, and industrial projects. Traditionally, the Delphi method involves anonymous surveys using questionnaires with controlled feedback to allow iterations within expert groups (Eastwood, 2011). It is also understood as a tool for reaching expert consensus through scientific discussion. This method is applicable to the development of assessment indicators (Smith et al., 2013; Hasson and Keeney, 2011). Expert panels propose solutions and improvements that make them sustainable at local, regional, and global scales (Escribano et al., 2018; Roy et al., 2014; Hasson and Keeney, 2011). The Delphi study presented in this paper was designed in a structured form to evaluate a list of predefined criteria for evaluating the WRH extracted from the literature. This method was used to develop the criteria used in this study.

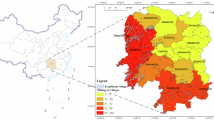

The selection of expert panel members is a key procedure in the Delphi method because the experts’ experience plays a crucial role in the validity of the results. At this stage, the criteria for the target sample of experts included (1) at least five years of experience in sustainable development and rural management and (2) a mid-level position or degree in a related field. The situation of “idle residential land” and “hollow villages” exists in many rural areas of China (Zhou et al., 2021). Given the similarity of China’s residential land problems, there is a desire to address this issue and achieve sustainable social development in rural areas. As the first region to implement WRH policy, this questionnaire was completed by 13 local experts from Fujian and land reform scholars. Invitation letters were emailed to the nominated participants to complete the two-round rating process, and they were asked to fill in their demographic information. The questionnaire provided participants with the opportunity to add free-text comments. A random sample of three experts was selected to complete a pre-survey and confirm its validity. This list is presented in Table 2.

Two email reminders were sent in each round, and participants were asked to rate the importance of the four dimensions on a seven-point scale (1 = very low importance to 7 = very high importance). The first round of questionnaires was conducted from April 29 to May 7, 2022. When the first round of questionnaires was complete, the experts’ suggestions were compiled, and the questions were revised. During the second round of questionnaire distribution, the experts were presented with the mean scores of each indicator from the first round of assessment as well as the feedback results and were asked to score the revised indicators again. The literature suggests a range of 10–15 participants for heterogeneous groups (expertise from different social or professional groups but on a single topic) with at least 2–3 experts (Geist, 2010). Thus, the sample size of this study was considered appropriate and met the Delphi survey criteria.

Consensus criteria

Four sets of combined standard measures were used to achieve consensus among expert opinions (see Table 3 for details). Before applying the Delphi method, we removed extreme values (i.e., the maximum and minimum values of the single indicator scores), informed the experts in the expert meeting email, and obtained their consent. The mean (N), first quartile (01), third quartile (03), standard deviation (SD), and coefficient of variation (CV) of the expert ratings were calculated using the Delphi method. After the first round of inquiries, one indicator of low importance (improving social welfare protection (C10), N < 3.5, 01 < 3, 03 < 4) was eliminated. Six indicators were rated as low importance (SD > 1, CV > 0.25): improving water quality (C1), improving air quality (C2), improving residential safety (C4), enhancing landscape coordination (C5), improving social welfare protection (C10), strengthening residents’ livelihoods (C17), and narrowing the gap between the rich and poor (C18). Therefore, we redesigned the questionnaire options to combine C1, C2, and C4 into a new C1 (improving the living conditions of residents) and C5, C10, C17, and C18 into a new C10 (promoting social equality in employment).

Based on the results of the second round of inquiries, the specific descriptions of the 20 criteria and their contents were confirmed. In addition, the criteria met the requirements in terms of importance and coherence. We further examined the results of expert ratings. Kendall’s coefficient of coordination test was used to examine the consistency of the evaluations. The results of Kendall’s coefficient of coordination test on expert opinions using the SPSS software showed that Kendall’s W = 0.144, p = 0. showed significance (p = 0.000 < 0.05). This indicates that the 12 evaluators’ evaluations were correlated and consistent. Kendall’s coordination coefficient test is used to measure the degree of consistency, for example, the consistency of multiple judges’ evaluations of multiple singers and multiple judges’ evaluations of multiple athletes (Schoonjans et al., 1995). Second, each expert’s opinion, degree of difference from the mean, and a new questionnaire were sent to the experts. The experts’ opinions were collected and compared with those obtained in the first step. If the difference between the two stages was less than a threshold of 0.2, the Delphi process was stopped.

Based on the screening and revision of criteria by experts, this study analyzed the criteria influencing social sustainability in rural China in four dimensions: Socio-ecological environment, social welfare, social equality, and social inclusion. These dimensions comprise 20 criteria, namely, improving residents’ living conditions (C1), improving the sanitary environment (C2), improving the built environment (C3), adopting environment-friendly building materials (C4), improving happiness (C5), enhancing village mobility (C6), improving infrastructure facilities (C7), securing housing property rights (C8), securing compensation benefits for home base withdrawal (C9), improving housing quality (C10), improving health (C11), supporting disadvantaged groups (C12), improving education (C13), promoting social equality in employment (C14), enhancing local government support policies (C15), enhancing residents’ sense of belonging (C16), enhancing social integration (C17), preserving local heritage (C18), preserving folk art and folklore activities (C19), and incorporating local cultural design (C20). After a comprehensive and iterative consultation process, an evaluation system consisting of four social dimensions and 20 criteria was finally developed through consensus among the selected experts (see Table 4 for details).

Fuzzy DEMATEL

The evaluation criteria focus on the environment, welfare, equity, and inclusiveness. These dimensions interact with each other, creating a complex system. The identification of evaluation criteria in previous studies has relied on subjective experience. According to Gabus and Fontela (1972), a decision-making trial and evaluation laboratory (DEMATEL) can be applied to complex systems to obtain the degree of influence and association of criteria, granting each factor its own weight in each domain (Abdullah and Rahim, 2020). The Fuzzy DEMATEL model collects expert empirical judgments, identifies the interrelationships among criteria, and builds a system model structure through an influence matrix, which maps influence network relationships (INRM). The influence matrix explains the causal relationships among criteria and helps to identify those that are key for decision-making. This application of matrix theory simplifies complex Socio-ecological environments, enabling the deduction of the direction of improvement. Fuzzy DEMATEL has been widely applied to spatial decision-making problems in housing planning and social sustainability projects as well as in other research areas, where many alternatives are evaluated using multiple criteria and perspectives (Koca et al., 2021). In real-world applications, uncertainty is inherent. To minimize subjective bias, fuzzy set theory has been applied to the concept of Fuzzy DEMATEL to make the model applicable to fuzzy contexts (Bidstrup et al., 2015; Fountas et al., 2006; Silva et al., 2014).

Fuzzy DEMATEL

Fuzzy DEMATEL uses an analytical approach to construct a structural model that illustrates the interrelationships among criteria. The mathematical model can also be transformed into a visual mapping, the Influence Network Relations Mapping (INRM), which can clarify the complex interrelationships between criteria, as in this study.

Following Lin et al. (2021), an exclusive Fuzzy DEMATEL questionnaire was designed for the experts. This questionnaire was designed in two parts in Chinese and sent to the experts’ email addresses. The first part was designed to collect basic information about experts. The second part included a 5-point Likert scale (no effect ← 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 → very high effect) to assess the impact of the relationship, as described in the supplementary material. The purpose of the Fuzzy DEMATEL questionnaire is to confirm the correlation and causality among the criteria by scoring their degree of interaction based on the judgment of an expert panel. A questionnaire was used to assess the influence of the criteria and causality among them.

We believe that WRH is not only about the land but also about the construction of buildings on the ground of the house site; therefore, two enterprise members of real estate were added to the expert team to obtain more precise expert opinions. Therefore, 15 valid questionnaires were administered. Among them, corporate experts are mainly middle and senior managers of land-use planning or housing construction planning businesses, who have deep knowledge of construction quality and the rationality of building area planning, and the academic field experts are mainly scholars who have published articles on residential land acquisition in domestic authoritative journals and have a strong influence in the field. Most researchers have been involved in the construction and development of rural areas. The list is presented in Table 5.

The plurality of direct influence scores among the criteria judged by experts was used as the initial direct influence matrix, and feedback was triangulated and defuzzified to obtain a new and more accurate initial direct influence matrix (see Appendix A2 for details). Subsequently, the fuzzy DEMATEL technique was used in Excel to identify the relationships between the criteria (Khalilzadeh et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2018). The calculation process for each step of the Fuzzy DEMATEL and the results of each calculation are as follows.

Step 1: Set fuzzy linguistic variables.

The recovered questionnaire values were first converted into fuzzy scales

(See Table 6 for details).

Step 2: Generate fuzzy directionalization matrix: z

In order to determine the relationship model between n factors, an n × n matrix is first generated. The influence of the elements in each row on the elements in each column of this matrix can be expressed as a fuzzy number. In this matrix, if one expert’s opinion is complete, the remaining experts must also complete the questionnaire.

The arithmetic mean of all expert opinions is used to generate the direct relationship matrix.

Step 3: Assume that \(\tilde Z = \left( {Z^l,Z^m,Z^u} \right)\) is a fuzzy number and the \({{{\tilde{\boldsymbol x}}}}_{{{{\boldsymbol{ij}}}}}\) is the defuzzification value of \(\tilde Z\). Applying Eq. (2) to normalize the fuzzy direct relationship matrix.(The matrix [xij] represents the degree of influence of [xi] on [xj]. When i = j, [xij = 0]).

The direct relationship matrix is normalized. Table A2 shows the results:

where

Table A3 represents the results of the normalized fuzzy direct relationship matrix.

Step 4: Applying Eq. (4) to calculate the fuzzy full relationship matrix \(\tilde S\).

The fuzzy full relationship matrix is calculated successively, as follows, In the formula, I represents the identity matrix:

Step 5: Declutter to clear values

Using the Converting Fuzzy data into Crisp Scores (CFCS) method proposed by Opricovic and Tzeng (2003), the clear values of the total relationship matrix are obtained. Table A4 represents the total impact relationship matrix of the criteria.

Step 6: Applying Eqs. (5) and (6) to calculate the causal attributes of the factors.

The last step is to find the sum of each row and column of T,t. The sum of rows (D) and columns (R) is calculated as follows:

Step 7: Create the influential network relations maps

A threshold value has to be determined to create the network structure using the total effect matrix. After the threshold value is determined, in the total effect matrix, cell values equal to or above this threshold value show the relationships between the criteria and the direction of these relationships. Various methods can be used to determine the threshold value. This study took the average of the elements in the total effect matrix.

Empirical results

The row sums (R), column sums (D), centrality (R + D), and causality (R-D) of each dimension/criterion are shown in Table 7.

For (R + D), a higher result means greater importance. The top-5 indicators with the highest (R + D) in each dimension are increasing happiness (C5) (2.925), increasing sense of belonging (C16) (2.922), increasing social integration (C17) (−0.274), improving living conditions (C1) (2.483), and improving infrastructure facilities (C7) (0.183). However, the R-value of enhancing social integration (C17) did not pass the average threshold of R 1.321; thus, the four criteria of increasing happiness (C5), increasing residents’ sense of belonging (C16), enhancing social integration (C17), and improving residents’ living conditions (C1) were considered key criteria. In addition, the table shows that the three criteria of promoting social equality in employment (C14) (0.931), improving the built environment (C3) (0.97), and enhancing village mobility (C6) (0.931) have the lowest R + D ranking. This indicates that they are low-priority factors.

The causal characteristics of the indicators were defined using (R-D), where a negative value means that the indicator has an outcome characteristic, and conversely, a positive value means that the indicator has a causal characteristic. Among the 20 criteria, improving education level (C13) (0.256) has the highest (R-D) value, indicating the strongest influence, which affects other criteria, followed by guaranteeing compensation benefits for residential land (C9) (0.209), guaranteeing home ownership (C8) (0.186), and C7 (0.183), C6 (0.169), C15 (0.157), C20 (0.117), C14 (0.089), C10 (0.068), C4 (0.061), C3 (0.031), and C18 (0.08). Factors with negative (R-D) values include preserving folk art and folklore activities (C19) (−0.009), improving sanitation (C2), and C19 (−0.009), C2 (−0.049), C12 (−0.107), C1 (−0.113), C11 (−0.18), C17 (−0.274), C16 (−0.287), and C5 (−0.513). The improvement of these 12 criteria will positively influence the 8 criteria with outcome characteristics (i.e., negative (R-D) values). For example, improving the level of education (C13) will improve the retention of folk art and folklore activities (C19).

Discussion

The order of influence of the antecedent variable social equity dimension through social welfare dimension and social equity dimension mediating variables (see Fig. 2) to influence the relationship results of the social inclusion dimension relationship is similar to the Fuzzy DEMATEL model proposed by Liu (2018), with the difference that social welfare can also function as an antecedent variable and directly influence the relationship results of social equity, further confirming the network relationship between variables demonstrated through the Fuzzy DEMATEL model; a network relationship exceeded the traditional linear relationship (Liu, 2018).

In addition, the INRM of the criteria plotted using the calculated results of the Fuzzy DEMATEL (see Fig. 3) demonstrates the causal relationships between the criteria under the subdimensions, which also confirms that D3 is the most influential dimension. Many studies have proposed assessing the quantification of indicators and comparing their contributions to each indicator (Vahabzadeh et al., 2015; Koplovitz et al., 2011). However, few studies have suggested a causal relationship between indicators, measured their contribution, or identified a criterion that may play a “leading role.” For example, the Rural Development Index (SDI) has been proposed to assess the level of each dimension using the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) method, which divides indicators and dimensions into specific components and quantifies them (Liang et al., 2017); however, it is unable to demonstrate the interactions of indicators (Zhao et al., 2021) proposed a multi-ethnic population development analysis method that used multiple data sources to construct an accurate SDI system and a joint multi-factor weighting model to assign specific SDI values to indicators; however, the indicators in this SDI did not interfere with each other. These findings may be useful for extending this theory and elucidating further exploration.

The Fuzzy DEMATEL has been widely applied in conjunction with integrated assessments to solve problems involving fuzzy or imprecise data. Fuzzy DEMATEL, which is a reliable decision-making method based on fuzzy set theory, is suitable for cases where the relationship between two elements in the AHP is difficult. It explains the weight ranking of the criteria, in addition to the influencing relationship between the criteria. Thus, it has been applied to the quantitative description of socioeconomic conditions and ecological characteristics (Feng and Xu, 1999; Meng et al., 2009). Figure 4 clearly classifies the causes and outcomes, showing that improving education levels (C13) and securing housing compensation benefits (C9) influenced all the other criteria. Du and Liang (2011) argued that improving labor productivity is central to achieving a leap from low to high-middle income and that securing social equity is fundamental.

In this study, the Delphi method was used to screen the criteria. We then applied fuzzy DEMATEL to measure the degrees of influence R and D of the four dimensions and 20 criteria. Third, the weights of each indicator were determined, and the INRM criteria and dimensions were plotted based on the centrality R + D and causality R-D values. Finally, based on the centrality R + D values, the measures related to the WRH policy and sustainable development of rural societies were identified by ranking the causality of the criteria. Rural areas have the greatest potential to transition from low to moderate-to-high income, and sustainable social development in rural areas is a prerequisite for realizing this potential. Future WRH policies should focus on strengthening the integration of rural education and on accelerating the development of rural education. To improve the level of rural human capital, promote the modernization of agriculture, improve the quality of rural labor transfer, and reduce the urban–rural gap, the rural economy and society must achieve long-term sustainable development (Yousefian et al., 2010).

This study highlights the importance of society in the development of sustainable development systems by analyzing the criteria for evaluating homestead exit policies. Saleth and Swaminathan (1993) proposed the Sustainable Livelihood Security (SLS) index to determine the necessary conditions for sustainable livelihood or development in a given area (Moser, 1996). SLS has also been used to focus on the linkages between livelihood capital assets and livelihood strategies such as agricultural expansion, land use, livelihood diversification, and migration (Fang et al., 2014; Martin and Kai, 2016; Xu et al., 2018; Wan et al., 2018), as well as the extent to which farmers are able to secure adequate and sustainable livelihoods. Happiness enhancement (C5) had the least negative R&D value and was an outcome factor). In other words, increasing the level of each factor would eventually increase residents’ happiness, which is consistent with Zhong et al. (2022) finding that the goal of rural urbanization is to increase villagers’ happiness. In terms of the living environment, narrowing the income gap between urban and rural residents, improving residents’ education level, and accessibility to public infrastructure and public services are the keys to perpetuating sustainable social development, such as Lin and Hou (2023). Our findings further prioritize the above key criteria for ranking, with improving residents’ education level being the most important one.

The indicator system proposed in this study examines the link between livelihood assets (homesteads) and rural society. Social capital has been used to explore the sustainable development of rural societies, and most findings suggest that an increase in social capital promotes land transfer (Yan et al., 2021). The government can encourage farmers with high social capital to quit their homesteads and use strong social networks to actively expand their income channels. Strong social cohesion and high levels of social capital can significantly reduce household vulnerability, enhance livelihood capital, and improve livelihood resilience (Thulstrup, 2015; Quandt, 2018).

Considering the social security function of residential land and the subsequent development of farmers’ livelihoods, the construction of an index system for assessing the effectiveness of residential land withdrawal can provide clearer ideas for the transformation of rural villages in China. Thus, this meaningful index system contributes to the sustainable development of rural society in China.

Conclusions

We analyzed the impact of the home-based withdrawal policy on sustainable social development, based on the analysis of factors influencing the sustainable development of rural society and China’s home-based withdrawal policy, and constructed an evaluation system of home-based withdrawal policy from a combination of quantitative and qualitative perspectives, focusing on four dimensions: social-ecological environment, social welfare, social equity, social fairness, and social inclusion, as well as the evaluation method for each specific criterion. The calculation method and source of the evaluation values are explained. Considering the uncertainty and vagueness of the qualitative criteria in the calculation of the impact assessment of the home-based withdrawal policy on social sustainability, this study introduced the fuzzy multi-criteria decision-making and Delphi methods to conduct relevant research. In addition, since sustainable social development is a concept involving the combination of “ecology-fairness-welfare-inclusion,” each sub-dimension is closely related to each other, and in order to express the influence relationship between the criteria, this study adopts the Fuzzy-DEMATEL model to quantify the relationship between the criteria and draws INRMs on this basis.

The results of the INRM study showed that increased well-being, an increased sense of belonging, enhanced social integration, and improved living conditions were the key determinants of WRH policy success, with the greatest ability to influence other criteria. This implies that the key factors in improving the well-being, sense of belonging, social integration, and living conditions of rural residents are the goals of WRH policy to achieve social sustainability in rural areas. This provides a more logical and convincing perspective for policymakers when revising their policies. The 20 criteria collated by the assessment system provide a comprehensive representation of the four irreplaceable and diverse dimensions of social sustainability. Additionally, the evaluation system proposed in this study can be modified according to the needs of different regions, and the robustness of the results can be further confirmed through feedback from different experts.

Recommendations for future research include further integration of the influencing relationships obtained from Fuzzy DEMATEL with the Analytic Network Process (ANP) to obtain evaluation weights and evaluate cases in practice. Additionally, the evaluation system proposed in this study can be modified according to the needs of different regions, and the robustness of the results can be further confirmed through feedback from different experts.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Abdullah, L, Rahim, N, (2020) The Use of Fuzzy DEMATEL for Urban Sustainable Development. In Kahraman, C, Cebi, S, Cevik Onar, S, Oztaysi, B, Tolga, A, Sari, I (eds) Intelligent and fuzzy techniques in big data analytics and decision making. Springer, Cham, pp 722–729

Abreu CG, Coelho CG, Ralha CG, Macchiavello B (2014) A model and simulation framework for exploring potential impacts of land use policies: The Brazilian Cerrado case. In 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, IEEE, pp 847–856

Abreu I, Mesias FJ (2020) The assessment of rural development: identification of an applicable set of indicators through a Delphi approach. J Rural Stud 80:578–585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.10.045

Aguilera GR, Ferrandiz L, Ramírez M (2018) Urban tele dermatology: concept, advantages, and disadvantages. Actas Dermosifiliog 109:471–475

Ao Y, Yang D, Chen C, Wang Y (2019) Exploring the effects of the rural built environment on household car ownership after controlling for preference and attitude: Evidence from Sichuan, China. J Transp Geogr 74:24–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2018.11.002

Assefa G, Ambler C (2017) To demolish or not to demolish: life cycle consideration of repurposing buildings. Sustain Cities Soc 28:146–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2016.09.011

Badal BP (2017) Social welfare model of rural development. Nepal J Dev Rural Stud 14(1–2):1–11. https://doi.org/10.3126/njdrs.v14i1-2.19642

Baker JA, Lovell K, Harris N, Campbell M (2007) Multidisciplinary consensus of best practice for pro re nata (PRN) psychotropic medications within acute mental health settings: a Delphi study. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 14(5):478–484

Ballet J, Bazin D, Mahieu F (2020) A policy framework for social sustainability: social cohesion, equity and safety. Sustain Dev 28(5):1388–1394. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2092

Barrios EB (2008) Infrastructure and rural development: household perceptions on rural development. Progr Plan 70(1):1–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2008.04.001

Bekun FV, Alola AA, Sarkodie SA (2019) Toward a sustainable environment: nexus between CO2 emissions, resource rent, renewable and nonrenewable energy in 16-EU countries. Sci Tot Env 657:1023–1029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.104

Beça P, Santos R (2010) Measuring sustainable welfare: a new approach to the ISEW. Ecol Econ 69(4):810–819

Bidstrup M, Pizzol M, Højrup Schmidt J (2015) Life cycle assessment in spatial planning—a procedure for addressing systemic impacts. J Clean Prod 91:136–144

Bill Hopwood, Mary Mellor, Geoff O’Brien (2005) Sustainable development: mapping different approaches, 13(1), 38–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.244

Billore S (2021) Cultural consumption and citizen engagement—strategies for built heritage conservation and sustainable development. a case study of Indore City, India. Sustainability 13(5):2878

Branker RR (2017) Labour market discrimination: the lived experiences of English-speaking Caribbean immigrants in Toronto. J Int Migr Integr 18:203–222

Brundtland GH (1987) Our common future—Call for action. Environ Conserv 14(4):291–294

Burja C, Burja V (2014) Sustainable development of rural areas: a challenge for Romania. Environ En Manag J 13(8):1861–1871. https://doi.org/10.30638/eemj.2014.205

Cai J, Zhang L, Tang J, Pan D (2019) Adoption of multiple sustainable manure treatment technologies by pig farmers in rural China: A case study of Poyang Lake Region. Sustainability 11(22):6458

Cai M, Murtazashvili I, Murtazashvili J (2020) The politics of land property rights. J Inst Econ 16(2):151–167. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744137419000158

Cao Q, Sarker MNI, Sun J (2019) Model of the influencing factors of the withdrawal from rural homesteads in China: application of grounded theory method. Land Use Policy 85:285–289

Chan WK (2015) Higher education and graduate employment in China: challenges for sustainable development. High Educ Policy 28(1):35–53. https://doi.org/10.1057/hep.2014.29

Chandrasekhar CP (1993) Agrarian change and occupational diversification: non-agricultural employment and rural development in West Bengal. J Peasant Stud 20(2):205–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066159308438507

Chatzinikolaou P, Bournaris T, Manos B (2013) Multicriteria analysis for grouping and ranking European Union rural areas based on social sustainability indicators. Int J Sustain Dev 16(3/4):335. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSD.2013.056559

Chen M, Chen L, Cheng J, Yu J (2022) Identifying interlinkages between urbanization and sustainable development goals. Geogr Sustain 3(4):339–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geosus.2022.10.001

Chen T, Hui ECM, Lang W, Tao L (2016) People, recreational facility and physical activity: New-type urbanization planning for the healthy communities in China. Habitat Int 58:12–22

Clapham D (2010) Happiness, well-being and housing policy. Policy Polit 38(2):253–267. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557310X488457

Cloutier S, Jambeck J, Scott N (2014) The sustainable neighborhoods for happiness index (SNHI): a metric for assessing a community’s sustainability and potential influence on happiness. Ecol Indic 40:147–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2014.01.012

Colantonio, A, Dixon, T, Ganser, R, Carpenter, J, Ngombe, A (2009) Measuring social sustainability urban regeneration in Europe. Oxford Brooks University, Oxford

Connelly R, Maurer-Fazio M (2016) Left behind, at-risk, and vulnerable elders in rural China. China Econ Rev 37:140–153

Constantin V, Ştefănescu L, Kantor C-M (2015) Vulnerability assessment methodology: a tool for policy makers in drafting a sustainable development strategy of rural mining settlements in the Apuseni Mountains, Romania. Environ Sci Policy 52:129–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2015.05.010

Daly, HE, Cobb, J (1989) For the common good: redirecting the economy toward community, the environment, and a sustainable future. Beacon Press, Boston, p 482

Davey G, Chen Z, Lau A (2009) ‘Peace in a thatched hut—that is happiness’: subjective wellbeing among peasants in rural China. J Happiness Stud 10(2):239–252

de Andrade LOM, Filho AP, Solar O, Rígoli F, de Salazar LM, Serrate PC-F, Ribeiro KG, Koller TS, Cruz FNB, Atun R (2015) Social determinants of health, universal health coverage, and sustainable development: Case studies from Latin American countries. The Lancet 385(9975):1343–1351. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61494-X

Devereux S (2001) Livelihood Insecurity and Social Protection: a re-emerging issue in rural development. Dev Policy Rev 19(4):507–519. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7679.00148

Di Marco M, Baker ML, Daszak P, De Barro P, Eskew EA, Godde CM, Harwood TD, Herrero M, Hoskins AJ, Johnson E, Karesh WB, Machalaba C, Garcia JN, Paini D, Pirzl R, Smith MS, Zambrana-Torrelio C, Ferrier S (2020) Sustainable development must account for pandemic risk. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117(8):3888–3892. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2001655117

Dong X, Xiong J (2019) The effect of social network on the diversification of rural families’ livelihood in the process of marketization. J Huazhong Agric Univ 143(5):71–77. https://doi.org/10.13300/j.cnki.hnwkxb.2019.05.009. (in Chinese)

Dong XH (2018) The predicament, outlet and remodeling of the circulation system of homestead right of use. Acad Exch 9:104–111. (in Chinese)

Du Y, Liang W. (2011) Rural education and rural economic development: a human capital perspective. J Beijing Norm Univ (06), 70–78

Du LZ, Chen X, Sun XM, Shang AY, Cao M (2014) Analysis on current situation and countermeasures of rural household garbage in China. Adv Mat Res 955–959:2640–2643. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.955-959.2640

Eberts, R (1986) Estimating the contribution of urban public infrastructure to regional growth (No. 86-10)

Eizenberg E, Jabareen Y (2017) Social sustainability: a new conceptual framework. Sustainability 9(1):68. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9010068

Escribano, M, Díaz-Caro, C, Mesias, FJ, (2018) A participative approach to develop sustainability indicators for dehesa agroforestry farms. Sci. Total Environ. 640–641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.05.297

Espina PZ, Arechavala NS (2013) An assessment of social welfare in Spain: territorial analysis using a synthetic welfare indicator. Soc Indic Res 111:1–23

Eastwood JL (2011) The paradox of scientific authority: the role of scientific advice in democracies: book Review. Sci Educ 95(2):380–382. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.20442

Evans G (2005) Measure for measure: evaluating the evidence of culture’s contribution to regeneration. Urb Stud 42(5–6):959–983. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980500107102

Faiz A, Faiz A, Wang W, Bennett C (2012) Sustainable rural roads for livelihoods and livability. Proc Soc Behav Sci 53:1–8

Fang YP, Fan J, Shen MY, Song MQ (2014) Sensitivity of livelihood strategy to livelihood capital in mountain areas: Empirical analysis based on different settlements in the upper reaches of the Minjiang River, China. Ecol Indic 38:225–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2013.11.007

Farrington J, Farrington C (2005) Rural accessibility, social inclusion and social justice: towards conceptualization. J Transp Geogr 13:1–12. Return to ref 2005 in article

Feng D, Zhu H (2022) Migrant resettlement in rural China: homemaking and sense of belonging after domicide. J Rural Stud 93:301–308

Feng S, Xu LD (1999) Decision support for fuzzy comprehensive evaluation of urban development. Fuzzy Set Syst 105:1–12

Fitouss JP, Sen AK, Stiglitz JE (2011) Mismeasuring our lives: why GDP doesn’t add up. ReadHowYouWant. com

Fix, M; Zimmermann, W, Passel, JS (2001) The Intergration of Immigrant Families in the United States; Urban Inst., Washington, DC, USA, pp 1–66

Fontela E, Gabus A (1974) Events and economic forecasting models. Futures 6(4):329–333

Foster S, Hooper P, Knuiman M, Christian H, Bull F, Giles-Corti B (2016) Safe RESIDential environments? A longitudinal analysis of the influence of crime-related safety on walking. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity 13(1):22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-016-0343-4

Fountas S, Wulfsohn D, Blackmore BS, Jacobsen HL, Pederson SM (2006) A model of decision-making and information flows for information-intensive agriculture. Agr Syst 87:192210

Gabus, A, & Fontela, E (1972) World problems, an invitation to further thought within the framework of DEMATEL. Battelle Geneva Research Center, Geneva, Switzerland, 1(8)

Galiani S, Schargrodsky E (2011) Land property rights and resource allocation. J Law Econ 54(S4):S329–S345. https://doi.org/10.1086/661957

García-Quero F, Guardiola J (2018) Economic poverty and happiness in rural Ecuador: the importance of buen vivir (living well). Appl Res Qual Life 13(4):909–926. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-017-9566-z

Ge J, Hokao K (2004) Residential environment index system and evaluation model established by subjective and objective methods. J Zhejiang Univ Sci A 5(9):1028–1034. https://doi.org/10.1631/jzus.2004.1028

Geist MR (2010) Using the Delphi method to engage stakeholders: A comparison of two studies. Eval Program Plan 33(2):147–154

Gizzi FT, Biscione M, Danese M, Maggio A, Pecci A, Sileo M, Potenza MR, Masini N, Ruggeri A, Sileo A et al. (2019) An experience within the framework of the Italian school-work alternation (SWA)—from outcomes to outlooks. Heritage 2:1986–2016

Gorlachuk V, Azarieva O, Belinska S, Potapsky Y, Petryshche O (2018) Defining the measures to rationally manage the sustainable development of agricultural land use. East Eur J Enterp Technol 4(3):47–53

Grundmann R, Stehr N (2010) Climate change: what role for sociology?: A response to constance lever-tracy. Curr Sociol 58(6):897–910. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392110376031

Guo Y, Liu Y (2021) Poverty alleviation through land assetization and its implications for rural revitalization in China. Land Use Policy 105:105418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105418

Gür M, Murat D, Sezer FŞ (2020) The effect of housing and neighborhood satisfaction on perception of happiness in Bursa, Turkey. J Hous Built Env 35(2):679–697. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-019-09708-5

Haller M, Hadler M (2006) How social relations and structures can produce happiness and unhappiness: An international comparative analysis. Soc Indic Res 75(2):169–216

Han, L, Wu, H, & Zeng, X (2021) What affects the “house-for-pension” scheme consumption behavior of land-lost farmers in China? Habitat Int 15

Hasson F, Keeney S (2011) Enhancing rigour in the Delphi technique research. Technol Forecast Soc Change 78(9):1695–1704

Higgs G, White SD (1997) Changes in service provision in rural areas. Part 1: the use of GIS in analysing accessibility to services in rural deprivation research. J Rural Stud 13(4):441–450

Hoeft TJ, Fortney JC, Patel V, Unützer J (2018) Task‐sharing approaches to improve mental health care in rural and other low‐resource settings: a systematic review. J Rural Health 34(1):48–62

Hong, Z (2020) Power, capital, and the poverty of farmers’ land rights in China. Land Use Policy 8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104471

Huang D, Jin H, Zhao X, Liu S (2014) Factors influencing the conversion of arable land to urban use and policy implications in Beijing, China. Sustainability 7(1):180–194

Hu G, Wang J, Fahad S (2023) Influencing factors of farmers’ land transfer, subjective well-being, and participation in agri-environment schemes in environmentally fragile areas of China. Environ Sci Pollut Res 30:4448–4461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-22537-4

Jiang N (2019) Legal structure and realizing path of the “Division of three rights” to the land of homestead. J Nanjing Agric Univ 19(03):105–116+159. https://doi.org/10.19714/j.cnki.1671-7465.2019.0043. (in Chinese)

Jian-Rong, YU (2001). Reasons for the absence of ownership of rural land. J Yl Teach Coll (in Chinese)

Jin H, Li L, Qian X, Zeng Y (2020) Can rural e-commerce service centers improve farmers’ subject well-being? A new practice of ‘internet plus rural public services’ from China. Int Food Agribus Manag Rev 23(5):17. https://doi.org/10.22434/IFAMR2019.0217

Kageyama, AA (2008) Desenvolvimento rural: conceitos e aplicação ao caso brasileiro. UFRGS Editora, Porto Alegre, pp 117–181

Kan K (2021) Creating land markets for rural revitalization: land transfer, property rights and gentrification in China. Journal of Rural Studies 81:68–77

Karahan F, Davardoust S (2020) Evaluation of vernacular architecture of Uzundere District (architectural typology and physical form of building) in relation to ecological sustainable development. J Asian Archit Build Eng 19(5):490–501

Kaygusuz K (2011) Energy services and energy poverty for sustainable rural development. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 15(2):936–947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2010.11.003

Ke Y, Ke H (2014) An analysis of the citizenship of migrant workers based on the perspective of community integration. Rural Econ 8:105–109. (in Chinese)

Kellekci ÖL, Berköz L (2006) Mass housing: user satisfaction in housing and its environment in Istanbul, Turkey. Eur J Hous Policy 6(1):77–99

Khalilzadeh M, Shakeri H, Zohrehvandi S (2021) Risk identification and assessment with the fuzzy DEMATEL-ANP method in oil and gas projects under uncertainty. Proc Comput Sci 181:277–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2021.01.147

Kinsella J, Wilson S, de Jong F, Renting H (2000) Pluriactivity as a livelihood strategy in irish farm households and its role in rural development. Sociol Ruralis 40(4):481–496. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9523.00162

Kinsella S, NicGhabhann N, Ryan A (2017) Designing policy: collaborative policy development within the context of the European capital of culture bid process. Cult Trends 26(3):233–248

Kiselitsa E, Shilova N, Liman I (2018) Impact of spatial development on sustainable entrepreneurship. Entrep Sustain Issues 6(2):890–911

Kitchen P, Williams A, Chowhan J (2012) Sense of belonging and mental health in Hamilton, Ontario: an intra-urban analysis. Soc Indic Res 108(2):277–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0066-0

Kizos T, Primdahl J, Kristensen LS, Busck AG (2010) Introduction: landscape change and rural development. Landsc Res 35(6):571–576. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2010.502749

Koca G, Egilmez O, Akcakaya O (2021) Evaluation of the smart city: applying the dematel technique. Telemat Inform 62:101625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2021.101625

Kong X, Liu Y, Jiang P, Tian Y, Zou Y (2018) A novel framework for rural homestead land transfer under collective ownership in China. Land Use Policy 78:138–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.06.046

Koplovitz G, McClintock JB, Amsler CD, Baker BJ (2011) A comprehensive evaluation of the potential chemical defenses of Antarctic ascidians against sympatric fouling microorganisms. Mar Biol 158(12):2661–2671

Ku BH-B (2011) ‘Happiness being like a blooming flower’: an action research of rural social work in an ethnic minority community of Yunnan Province, PRC. Action Res 9(4):344–369. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750311402227

Kumar S, Jain A, Kar S (2011) Health and environmental sanitation in India: issues for prioritizing control strategies. Indian J Occup Environ Med 15(3):93. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5278.93196

Chan E, Lee GKL (n.d.) Critical factors for improving social sustainability of urban renewal projects. 14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-007-9089-3

Leung A, Kier C, Fung T, Fung L, Sproule R (2013) Searching for happiness: the importance of social capital. In The exploration of happiness. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 247–267

Li Y, Westlund H, Cars G (2010) Future urban‐rural relationship in China: comparison in a global context. China Agric Econ Rev 2(No. 4):396–411. https://doi.org/10.1108/17561371011097713

Liang F, Wang Z, Lin S-H (2022) Can land policy promote farmers’ subjective well-being? A study on withdrawal from rural homesteads in Jinjiang, China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(12):7414. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127414

Liang R, Song S, Shi Y, Shi Y, Lu Y, Zheng X, Han X (2017) Comprehensive assessment of regional selenium resources in soils based on the analytic hierarchy process: assessment system construction and case demonstration. Sci Total Env 605:618–625

Li Y, Hu Z (2015) Approaching integrated urban-rural development in China: the changing institutional roles. Sustainability 7(6):7031–7048

Lin S, Hou L (2023) SDGs-oriented evaluation of the sustainability of rural human settlement environment in Zhejiang, China. Heliyon 9(2):e13492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13492

Lin S-H, Huang X, Fu G, Chen J-T, Zhao X, Li J-H, Tzeng G-H (2021) Evaluating the sustainability of urban renewal projects based on a model of hybrid multiple-attribute decision-making. Land Use Policy 108:105570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105570

Liu G, Yang L, Guo S, Deng X, Song J, Xu D (2022) Land attachment, intergenerational differences and land transfer: evidence from Sichuan Province, China. Land 11(5):695. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11050695

Liu Y (2018) Introduction to land use and rural sustainability in China. Land Use Policy 74:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.01.032

Liu K-M, Lin S-H, Hsieh J-C, Tzeng G-H (2018) Improving the food waste composting facilities site selection for sustainable development using a hybrid modified MADM model. Waste Manag 75:44–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2018.02.017

Liu, X, Yang, F, Cheng, W, Wu, Y, Cheng, J, Sun, W, Yan, X, Luo, M, Mo, X, Hu, M, Lin, Q, Shi, J (2020) Mixed Methods Research on Satisfaction with Basic Medical Insurance for Urban and Rural Residents in China [Preprint]. In Review. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-15564/v2

Liu YS, Li YH (2017) Revitalize the world’s countryside. Nature 548:275–277

Long H (2014) Land consolidation: an indispensable way of spatial restructuring in rural China. J Geogr Sci 24(2):211–225

Long H, Liu Y, Li X et al. (2010) “Building new countryside in China: a geographical perspective. Land Use Policy 27(2):457–470

Long H, Tu S (2018) Land use transition and rural vitalization. China Land Sci 32(7):1–6. (in Chinese)

Long H, Zhang Y, Tu S (2019) Rural vitalization in China: a perspective of land consolidation. J Geogr Sci 29(4):517–530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11442-019-1599-9

Long H, Li Y, Liu Y, Woods M, Zou J (2012) Accelerated restructuring in rural China fueled by ‘increasing vs. decreasing balance’land-use policy for dealing with hollowed villages. Land Use Policy 29(1):11–22

Long HL, Tu SS, Ge DH, Li TT, Liu YS (2016) The allocation and management of critical resources in rural China under restructuring: problems and prospects. J Rural Stud. 47:392–412

Lu H, Zhao P, Hu H, Zeng L, Wu KS, Lv D (2022) Transport infrastructure and urban-rural income disparity: a municipal-level analysis in China. J Transp Geogr 99:103292

Lu X, Peng W, Huang X, Fu Q, Zhang Q (2020) Homestead management in China from the “separation of two rights” to the “separation of three rights”: Visualization and analysis of hot topics and trends by mapping knowledge domains of academic papers in China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI). Land Use Policy 97:104670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104670

Luo R, Zhang L, Liu C, Zhao Q, Shi Y, Rozelle S, Sharbono B (2012) Behind before they Begin: The Challenge of Early Childhood Education in Rural China. Aust J Early Child 37(1):55–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/183693911203700107

Malhoit, GC (2005) Providing Rural Students with a High Quality Education: The Rural Perspective on the Concept of Educational Adequacy. Rural School and Community Trust

Martin SM, Kai L (2016) Livelihood diversification in rural Laos. World Dev 83:231–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.01.018

Meng W, Zhong Q, Chen Y et al. (2019) Energy and air pollution benefits of household fuel policies in northern China. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116(34):16773–16780