Abstract

The present study revisits the unique item hypothesis (UIH) from the perspective of translation directionality in the Chinese–English(C–E) language pair. Phrasal verb (PV) is used as the linguistic feature to investigate whether UIH holds true in C–E translations and whether translation directionality plays a role in the representation of unique items, based on a self-built parallel corpus of Lu Xun’s short stories and their English translations done by two L1 and two L2 translators, and a reference corpus of BNC short stories as the non-translated reference. It is found PVs are significantly over-represented in C–E translated texts when compared with English non-translated texts, and this overrepresentation is mainly attributed to the remarkable use of PVs by L1 translators; and there is a significant difference in the use of PVs by translators of different directionality, while no significant difference is found within the same direction. Additionally, L2 translators tend to use a limited range of PVs and prefer transparent PVs to semi-transparent and opaque ones. The results falsify the UIH in general and suggest that UIH is a conditional translation tendency constrained by translation directionality, or UIH is directionality-dependent. Gravitational pull model is used to analyze and explain the divergence between different translation directions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Unique item hypothesis

The unique item hypothesis (UIH) is a translation universal tendency proposed by Tirkkonen-Condit (2002), claiming translations tend to contain fewer unique items than comparable non-translated texts. Unique items are defined as target-language-specific items that lack straightforward translation counterparts or equivalents in the source language (Tirkkonen-Condit 2004). Presumably, translators may ignore these items, as they are not likely to suggest themselves readily as one-to-one equivalents to any particular item in the source text (Tirkkonen-Condit 2002). Tirkkonen-Condit (2004) attributed the underrepresentation of unique items to translators’ tendency to rely on a literal approach when selecting lexical items, syntactic structures, and idiomatic expressions from their bilingual mental lexicon during the translation process. Therefore, the absence of an obvious linguistic trigger for these items in the source language could lead to their underrepresentation or less frequent use in the translated texts compared to non-translated texts.

Since its proposal, the unique items hypothesis (UIH) has garnered significant scholarly attention and has been the subject of many empirical investigations and tests. The evidence gathered from these studies presents a diverse picture. Tirkkonen-Condit (2004) conducted a study on Finnish translated texts from English and found that certain typical elements of Finnish were less frequently used compared to non-translated Finnish texts, providing empirical support for the UIH. Similarly, Cappelle (2012) examined the use of manner-of-motion verbs in translated and non-translated English texts. The study revealed that translations from French contained fewer manner-of-motion verbs than original English texts, given the verb-framed nature of the French language. In contrast, no such difference was observed between English translations from German and original English, as Germanic languages share a similar satellite-framed structure. These findings further bolstered the validity of the unique item hypothesis. Further evidence for the UIH was presented by Vilinsky (2012), who compared the frequencies of Spanish verbal periphrases in original Spanish texts and Spanish translations from English. The study revealed a lower frequency of Spanish verbal periphrases in translated texts, indicating a tendency among translators to avoid unique items. Similarly, Tello (2022) explored the translation of diminutives into Spanish using the COVALT corpus and found supporting evidence for the UIH. Translated texts exhibited lower frequencies of diminutives compared to non-translated texts, suggesting a deliberate avoidance by translators. The study also found that the use of diminutives varies depending on the source language, target language, and genre. In another investigation by Cappelle and Loock (2017), an underuse of phrasal verbs was observed in English translations from Romance languages compared to non-translated fictions in the British National Corpus. However, no significant difference in the use of phrasal verbs was found between non-translated English and English translated from Germanic languages. This discrepancy was attributed to source-language interference resulting from typological differences between the source and target languages. These findings underscore the influence of typological similarities or differences between language pairs on the use of unique items in translated texts, suggesting that the use of unique items in translated texts is source language dependent and influenced by typological similarities or differences between the language pair. These evidences consistently support the unique item hypothesis, i.e., translators tend to underuse linguistic structures that are not present in the source language.

However, findings from other research have challenged or falsified the unique item hypothesis. Hareide’s studies (Hareide 2017a; Hareide 2017b) on the Spanish gerund in translations from Norwegian found that the Spanish gerund was significantly over-represented. The study suggests that over-representation of target-language specific features may occur in translations, in contrast to the under-representation predicted by the UIH. The study attributed this over-representation to the normalization process, where translated texts tend to conform to the linguistic norms of the target language. Kenny and Satthachai’s study (2018) on the translation of passive voice from English into Thai also refuted the UIH. The study found that most English passives are translated into Thai using passive voice, indicating that unique items are not underrepresented in Thai translation.

To provide possible explanations for translation universal tendencies, Halverson (2003, 2010) proposed the gravitational pull hypothesis (GPH) and developed it into a cognitive linguistic model (2017). The model depicts three cognitive forces influencing translators’ choice of language items (Hareide 2017b; Halverson 2010, 2017), namely, the gravitational pull caused by the highly salient representational elements in the source language (Halverson 2017), the magnetism exerted by the target language items with high salience/frequency (ibid.), the connectivity resulting from the strength of connectivity between elements in the source and target languages(ibid.). The interrelation and interplay of the three forces will result in the make-up of the translated language. Regarding unique items, the gravitational pull hypothesis suggests that both over- and under-representation of particular target-language items is possible, depending on the specific structure of the bilingual semantic network activated in any given instance. (Halverson 2010). Specifically, this model may predict an underrepresentation resulting from insufficient gravitational pull due to the lack of these items in the source language, an overrepresentation caused by magnetism due to their pervasiveness in the English target language, and an underrepresentation due to weak connectivity between the language pair. The ultimate outcome depends on which force outweighs the other.

To determine which force predominates the others, previous researches tested gravitational pull model in different contexts. Marco and Oster (2018) compared the use of diminutive suffixes in Catalan translated from German and English, the former having productive diminutive suffixes while the latter not. The major findings include that the force of connectivity overrules that of magnetism, and the counterbalance of the forces makes the outcome somewhat unpredictable. Marco (2021) examined the use of the Catalan modal verb caldre in translations from English and French into Catalan, using data from two sub-corpora of the COVALT corpus. The study found evidence to support hypotheses of under-representation of caldre in the English-Catalan sub-corpus and over-representation in the French-Catalan sub-corpus. The study additionally revealed that the over-representation of caldre was significantly influenced by its strong connectivity with corresponding linguistic triggers in the French source texts. It concludes that connectivity may determine the over or under-representation of the language features in translations. Lefera and De Sutterb (2022) used Halverson’s gravitational pull hypothesis to explain the interpretation and translation of concatenated nouns in mediated European Parliament discourse and support the applicability of GPH in this specific domain. They found that the forces of gravitational pull, magnetism, and connectivity all play a role in the translation and interpretation of concatenated nouns and suggested the gravitational pull model is a useful tool for understanding the complex interplay of forces that influence the translation and interpretation of specific linguistic features.

In summary, three cognitive forces were found waxing and waning, counterbalancing each other, and jointly shaping the translational language. However, no consistent conclusion was reached regarding which cognitive force predominates in the specific context.

Phrasal verbs

Unique items in a target language can be found at various linguistic levels, such as lexical, phraseological, syntactical, textual, collocational, or pragmatic (Tirkkonen-Condit 2002). The present study is interested in the use of phrasal verbs at the phraseological level. A phrasal verb is usually defined as a structure that consists of a verb proper and a morphologically invariable particle that functions as a single unit both lexically and syntactically (Darwin and Gray 1999). The present study determines on phrasal verbs as the linguistic feature for several reasons.

Firstly, phrasal verbs are a typical phenomenon of the English language and have always held a central place in English. Phrasal verbs occur more frequently than other linguistic features, such as the verb are, the determiners this or his, the negative not, the conjunction but, or the pronoun they (Gardner and Davies 2007).

Secondly, phrasal verbs exhibit the traits of unique items in the context of Chinese–English translation. According to Tirkkonen-Condit (2004) and Chesterman (2004, 2011), unique items should semantically or pragmatically the same but structurally different in the language pair. Although in the Chinese language, there are examples of verb-particle structures like the motion verbs guolai (过来 - come over here) and guoqu (过去 - go over there), where particles lai (来) and qu (去) are added to the verb guo (过) to indicate direction. However, unlike in English, the particles in these Chinese words are generally considered inseparable from the verbs and are always treated as a single unit or word (Liao and Fukuya 2004). Moreover, English phrasal verbs can be replaced with a single verb (e.g., put off can be replaced with postpone), whereas Chinese verb-particles cannot. Furthermore, English phrasal verbs and Chinese motion verbs differ significantly in their numbers. English has about 3,000 established phrasal verbs, which make up one-third of the English verb vocabulary (Li et al. 2003), while Chinese motion verbs are limited in number (Liao and Fukuya 2004).

Lastly, verb-particle structures rarely take on figurative meanings in Chinese as they often do in English (ibid). Phrasal verbs can be categorized into three types based on their semantic transparency: directional, aspectual, and figurative. Directional PVs are semantically transparent, in which both the verb and the particle retain their literal meanings, the particle often indicating geographical direction, e.g., stand up. Aspectual PVs are semantically semi-transparent, in which the verb has a literal meaning and the particle provides an aspectual meaning, e.g., read through. Figurative PVs are semantically opaque in which the verb and the particle have an idiomatic meaning, e.g., figure out (Wierszycka 2013; Riguel 2014).

What is worth notice is that the limited number of semantically transparent directional PVs like stand up, have equivalents of motion verbs like Zhanqilai(站起来) in Chinese, while many semantically semitransparent aspectual phrasal verbs like read through and semantically opaque figurative ones like figure out do not have direct equivalents in Chinese. Due to these distinct features of verb-particle structures between Chinese and English, English phrasal verb can be regarded as a unique item to test unique item hypothesis in C–E translation.

Regarding the use of phrasal verbs, studies on second language acquisition have highlighted significant challenges faced by L2 English language users, primarily due to the idiomaticity and polysemy of these constructions (Riguel 2014). Research has shown that second language learners of English often exhibit a preference for single-word verbs over phrasal verbs (Dagut and Laufer 1985; Laufer and Eliasson 1993). This inclination is observed across all proficiency levels, including the most advanced learners (Siyanova and Schmitt 2007), although an improvement in phrasal verb use has been noted from intermediate to advanced proficiency levels (Wei 2021). Scholars refer to this phenomenon as “avoidance behavior” (Kleinmann 1977), suggesting that learners consciously avoid phrasal verbs to minimize errors and maintain linguistic safety. Notably, this tendency is particularly observed in English learners whose first language lacks equivalent phrasal verb constructions (Riguel 2014; Liao and Fukuya 2004). Additionally, L2 learners tend to use a limited range of PVs and prefer transparent verbs to semi-transparent and opaque ones (Dagut and Laufer 1985; Wierszycka 2013). These findings highlight the perplexity of acquiring and using phrasal verbs by Chinese L2 English learners and spark our curiosity about the use of phrasal verbs by L2 translators. Given these, phrasal verbs may serve as an ideal linguistic feature to investigate unique item hypothesis in Chinese to English translation.

Directionality

Translation directionality can be understood in two ways. One is the direction between the source language (SL) and target language (TL), like Chinese to English as one direction and English to Chinese the other. The other understanding of directionality concerns whether translators are working from a foreign language into their mother language or vice versa (Beeby Lonsdale1998), the one done from a foreign language into one’s mother tongue being native translation or L1 translation, otherwise non-native translation or L2 translation. This study adopts the second understanding.

The significance of directionality has been highlighted by the findings made in the studies of cognitive processes during translation. These studies typically utilize neurolinguistic and psycholinguistic approaches, such as eye-tracking, keylogging, and behavioral experiments together with recall interviews, to compare the cognitive processes involved in L1-L2 and L2-L1 translation and interpretation tasks. The results consistently demonstrate that translation directionality does have impact on the cognitive processing of translation (Pavlović and Jensen 2009; Chou et al. 2021; Tomczak and Whyatt 2022; Jia et al. 2023) and suggest the importance of considering directionality when investigating the cognitive processes of translation, although directionality may not impact translation quality as decisively as other factors like L2 proficiency, the broadness of the translator’s general knowledge and text type (Pokorn et al. 2020).

Despite the growing interests in cognitive translation and interpreting studies (Ferreira 2023), translation directionality is not a primary concern in descriptive translation studies. Although factors like text types, language pairs, language typology, translator style etc. are generally taken into consideration when researchers try to test various translation generalizations and explore the boundaries of their validity in the translated texts, directionality receives little attention. This neglect of translation directionality may stem from the conventional belief that translations away from one’s own language are not noteworthy unless when the difficulties are emphasized. Consequently, the predominance of L1 translations is often assumed, overshadowing L2 translations and neglecting the potential impact of directionality on the final translated products.

Few researchers have studied the impact of translation directionality on the translational texts. Zhan and Jiang (2023) found that the idiomaticity level of native translations of Lu Xun’s short stories is significantly higher than that in non-native translations by observing the use of phrasal verbs in the translational texts; Xu et al. (2021) found that translation directionality influences the representation of the emotions and thus influences the image reconstruction of in the target texts. Despite the valuable insights already gained, the role of translation directionality remains underexplored in the context of the translation universal hypothesis. Integrating an analysis of translation directionality into the study of translation universals is anticipated to provide pivotal insights, particularly in validating and expanding our understanding of prevalent translation tendencies, such as those observed in the UIH in the present study. This broadening of research scope holds significant promise for extending the boundary conditions of the UIH and illuminating the complex dynamics inherent in cognitive processes during translation.

Research gaps and questions

In summary, three significant research gaps have been identified. Firstly, testing of the Unique item hypothesis has been conducted mainly between Indo-European language pairs, and there is a lack of investigation into the UIH in the linguistically distant Chinese–English language pair. Secondly, despite the significance of translation directionality, there is a notable absence of research in descriptive translation studies that specifically explores how it influences the features of translational products. This gap limits the understanding of how translation directionality might support or refute such hypotheses of translation universals like the UIH in this study. Thirdly, in attempting to prove the validity of the gravitational pull model in accounting for the varying outcomes observed in the testing of the UIH, existing research has overlooked the potential impact of translation directionality on the cognitive semantic networks of translators, which in turn limits the insights into unique item hypothesis. Addressing these gaps can enhance the understanding of the unique item hypothesis, highlight the differences in cognitive processes of translators of different directionality, and contribute to the ongoing development of descriptive translation studies.

The present study is to examine the validity of the UIH in the Chinese–English language pair and to explore whether the representation of unique items differs between L1 and L2 translations. Specifically, we aim to test the UIH in Chinese–English translation by considering the directionality of translation, to determine whether UIH holds true in Chinese–English translation and whether translation directionality affects the use of unique items in the target texts.

The first question is whether phrasal verbs will be underrepresented in Chinese–English translations when compared with original English. Based on the UIH, we predict that phrasal verbs will be underrepresented in the Chinese–English (C–E) translated texts than non-translated texts. Considering translation directionality, we also seek to explore whether the use of phrasal verbs diverges between L1 and L2 translations. Building upon the findings in second language acquisition, we aim to investigate whether L2 translators with Chinese as their mother tongue may have a similar tendency to underuse PVs, particularly those semantically opaque ones, compared to L1 English translators. Accordingly, in what follows, the present study aims to seek answers to the questions below:

-

1.

Are phrasal verbs underrepresented in C–E translations when compared with non-translated (original) English texts, respectively?

-

2.

Does the overall frequency of phrasal verb use differ between L1 and L2 translations? If the answer is yes, we will proceed to question 3.

-

3.

What specific differences do L1 and L2 translations demonstrate in the use of phrasal verbs, with reference to the original English?

The writer and the translators

To guarantee the representativeness and relevance of the parallel corpus, we controlled several key variables, including the reputation of both the author and the translators, the distinctiveness of the source texts’ style, and an equal number of translations in both directions. We finally determined on short stories by renowned Chinese author Lu Xun, translated by four distinguished L2 and L1 translators, proficient in both languages: Wang Jizhen and Yang Xianyi, Julia Lovell and William A. Lyell.

The present study chose Lu Xun’s short stories as the source texts for two primary considerations: their distinct casual and colloquial language style, and the abundance of available target texts. Lu Xun (1881–1936) was a pivotal figure in the New Culture Movement in early 20th-century China, particularly renowned for his groundbreaking contributions in the advocacy and utilization of vernacular Chinese. His departure from the use of highly codified wenyan (classical Chinese, 文言文) to the use of baihua (vernacular Chinese,白话文) in writing was meant to bridge the gap between literature and the common people, to break down the barriers that existed between the elite literary circles and the general populace, to better capture the realities of the society and resonate with a broader audience. Therefore, vernacular Chinese is depicted as dialectal, plain, unadorned and colloquial, close to the spoken Chinese used by ordinary people, contrasted with the “classical Chinese” used by the elites (Kullberg and Watson 2022). This vernacular style involves a high level of colloquiality and idiomaticity, characterized by the frequent use of dialects, idioms, and colloquialisms (Wang and Phil 2011). A phrasal verb is a typical feature of colloquial language and everyday English, and thus, English translations of Lu Xun’s works are assumed to characterize a typical use of phrasal verbs, to preserve the stylistic essence of the source texts. Furthermore, Lu Xun’s literary works have gained widespread attention worldwide and have been extensively translated by esteemed translators, contributing to their significance and relevance in translation studies.

Both the two L2 translators, Wang and Yang, were highly proficient bilingual translators with extensive experience. They received higher education in English-speaking countries and were immersed in English language environments for many years. As such, their translations can represent the pinnacle of Chinese-to-English L2 translations. Similarly, both the two L1 translators, Lovell and Lyell, gained immense recognition in translating Chinese literature into English. Their translations are believed to exemplify the highest quality of Chinese-to-English translational language.

It is noteworthy that Yang Xianyi collaborated with his wife, Gladys, in their translation endeavors: Yang Xianyi would craft the initial draft of the translation, while Gladys undertook the tasks of proofreading and typing (Yang 2003; Wang and Wang 2013). The translation approach used by the Yangs involved both partners initially reading the source material together. Subsequently, Xianyi Yang would create a preliminary translation draft. This draft would then be revised by Gladys Yang, typically undergoing two or three revisions (Yang 2002). Despite their differing views on translation, where Yang prioritized loyalty and adhered to literal translation, while Gladys sought creativity with a target culture orientation (Fu 2011), their collaboration was notably dominated by Yang. The resulting translations predominantly mirror Yang’s well-established translation habits, as asserted by Wang et al. (2020). Consequently, their translation is conventionally classified as L2 translation or indirect translation.

Materials and methodology

Corpus

A parallel corpus was built composed of 10 Chinese short stories written by Lu Xun and their corresponding English versions translated both by four L1 and L2 translators.

We initially aimed to include all of 25 Lu Xun’s short stories from the collections “Nahan” (呐喊) and “Panghuang” (彷徨) as the source texts. However, Yang and Wang had translated only a subset of these stories, rather than the entire collection. To balance the corpus, we only used the ten source texts that were translated by all the four translators. The resulting corpus contains a sub-corpus of 84018 Chinese words and four sub-corpora of 261888 English words in total, as shown in Table 1. The target texts were cleaned, tagged with CLAWS7 and aligned at the sentence level with the cleaned source texts.

For the original reference corpus, we randomly sampled 40 short stories from BNC sub-corpus of fiction, totaling 371,155 words (see Appendix). BNC short stories were also cleaned and tagged with CLAWS7.

Procedures

Combining quantitative and qualitative analysis, the research follows these steps:

-

1.

Retrieving phrasal verbs

To facilitate the analysis of phrasal verbs in our study, we utilized Python programming to count and extract these linguistic structures. Specifically, we employed Python scripts to tally the occurrences of phrasal verbs in each text and extract them from both the L1 and L2 corpora. The identified phrasal verbs were subsequently subjected to lemmatization, allowing us to generate comprehensive lists of phrasal verbs for both L1 and L2 translations.

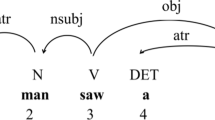

PVs under the CLAWS tagging system are annotated as VV0, VVD, VVG (including VVGK), VVI, VVN, and VVZ as lexical verbs followed by RP standing for adverbial prepositions. The tags, their explanations, and examples are shown in Table 2 for clarity. The number of intervening words between the lexical verb and the adverbial particle is set between 0 and 6 (Gardner and Davies 2007).

To ensure accuracy and double-check the results obtained through Python programming, we conducted additional searches using the Concordance function of AntConc 3.5.7w, specifically targeting the adverbial preposition tag (RP) in each text. This manual check allowed us to reconfirm the counts obtained through the Python program. It is important to note that, due to the inherent limitations of the tagging system, manual screening was necessary to eliminate some unwanted concordances, such as cases where the adverbial particle is not part of a phrasal verb (e.g., “all the way down to the floor,” where “down” functions as an adverbial particle but not part of a phrasal verb).

-

2.

Performing statistical significance testing

After counting the occurrences of phrasal verbs in each text, a statistical analysis was performed to determine the presence of any significant differences in the frequencies of phrasal verbs. Our analysis focused on three comparisons: (1) between translated texts and non-translated texts, (2) between L1 and non-translated texts, between L2 and non-translated texts, and (3) between L1 and L2 translations.

-

3.

Comparing the TTR, ARR, hapax legomena, and high-frequency PVs

TTR is a metric used to assess the level of variation or diversity in the usage of phrasal verbs within a text. A higher TTR indicates a greater variety of phrasal verb lemmas used, suggesting a more diverse usage of phrasal verbs. Conversely, a lower TTR suggests a more concentrated or repetitive use of phrasal verbs within the text. ARR is a measure of the concentration and repetitiveness of phrasal verb lemmas in a given text or corpus, reflecting the morphological concentration and lexical complexity of phrasal verbs. ARR is calculated by dividing the total number of PV tokens by the number of unique PV lemmas. A higher ARR value suggests a more concentrated and repetitive use of PVs, indicating a lower degree of diversification in the choice of PV lemmas. Conversely, a lower ARR value indicates a higher level of lexical diversity in the usage of phrasal verbs. Hapax legomena refers to phrasal verb forms that occur only once within a specific text or corpus (Kenny, 2001). It is considered an indicator of creativity, suggesting a unique and innovative expression. The use of hapax legomena can provide insights into the stylistic and linguistic creativity in the use of phrasal verbs in the translated texts.

The TTR, hapax, and the top twenty phrasal verbs were compared to uncover the more specific differences or similarities between L1 and L2 translations.

-

4.

Making semantic analysis of the key PVs

Python programming was used to lemmatize and generate the PV lists of L1 and L2 corpus. Then the keyword (PV) analysis was conducted to identify the key phrasal verbs in different lists, based on which a further qualitative semantic analysis of key phrasal verbs used in L1 and L2 translations was performed.

Results

Are phrasal verbs underrepresented in C–E translations when compared with non-translated (original) English texts?

As shown in Table 3 and Fig. 1, BNC short stories contain an average of 12.9‰ of PVs, with the peak point at 25.4‰, and the valley point at 4.5‰. The proportion of PVs in the translated texts is averaged 15.8‰, with the peak at 25.5‰ and the valley at 8.7‰. Figure 1 is the standardized proportion of PVs per thousand words across texts in BNC, with the horizontal axis listing the 40 randomly sampled novels of BNC.

As the BNC corpus of short stories was limited in its size, to cross-validate the results, we proceeded to compare the data from Lu Xun’s translated texts with that drawn from another English fictional corpus, which was referenced from Rodríguez-Puente (2019). Through a chronological study of phrasal verbs from 1650 to 1990, Rodríguez-Puente found the use of phrasal verbs showed a steady increase in fiction over time. The standardized frequency of PVs per 1000 words in original English fiction was approximately 9.7(‰) between 1900–1950 and 13.3(‰) between 1950 and 1990. The average number of 13.3‰ is very close to the data we obtained from the corpus of the sampled BNC short stories in the present study, 12.9‰. With the PV frequency in translated texts averaged 15.8(‰), it is evident that phrasal verbs are generally overrepresented in C–E translations than that in the English original.

Statistical analysis of the standardized PV proportion (Table 4) showed that there was a significant difference in the use of PV between Lu Xun translational corpus and BNC (P < 0.001). We observed the standard deviation in BNC was 5.1, while that in translated texts was 4.6, with the former more discrete than the latter, suggesting that the PV use in original English is more varied across texts and than that in translations.

Thus, our answer to the first question is negative, i.e., phrasal verbs are not underrepresented in Chinese–English translated texts when compared with original English. This result is contrary to what the unique item hypothesis predicts as the tendency of underrepresentation of unique items in the target texts. On the contrary, our results suggest an over-representation of phrasal verbs in C–E translations, which runs counter to the aforementioned hypothesis.

Does the use of phrasal verbs significantly differ between L1 and L2 translations and original English, respectively?

What arouses our curiosity is whether L1 and L2 translations unanimously contain a higher proportion of phrasal verbs when compared with original texts. To further investigate the influence of translation directionality on the use of phrasal verbs, we compared the proportion of PVs between L1 translations and BNC, L2 translations and BNC, and L1 and L2 translations, respectively. It was found that L1 translations contained a significantly higher proportion of phrasal verbs compared to BNC short stories, with an average of 19.2‰ and 12.9‰, respectively (P < 0.001). However, L2 translations had a slightly lower proportion of phrasal verbs than BNC short stories, with an average of 12.3‰ and 12.9‰, respectively, and this underrepresentation is not statistically significant (P > 0.05). Furthermore, L1 translations contained a significantly higher proportion of phrasal verbs than L2 translations, with an average of 19.2‰ and 12.3‰, respectively, and the statistical difference is remarkably significant (P < 0.001) (see Table 4).

To test whether the use of PVs significantly differs within the same translation direction, another statistical analysis was carried out. The results, as presented in Table 5, indicate that there is no significant difference in the use of PVs between the two translators within the same translation direction (P > 0.05).

Therefore, our answer to the second research question is that the use of phrasal verbs remarkably differs between L1 and L2 translations. On the one hand, all the L1 translated texts contain a significantly higher proportion of PVs than L2 translated texts (see Fig. 2). As is shown in Fig. 3, Wang’s translations contain the lowest proportion of PVs (8.7‰), slightly lower than of Yang’s (8.8‰), while Lyell’s the highest (23.5‰), with the ranking order as Lyell>Lovell>Yang>Wang. These findings lend support to the effect of translation directionality on the use of phrasal verbs; namely, the use of phrasal verbs is apparently directionality dependent in C–E translations.

Even when narrowing down the search to the top three most commonly used particles up, out, and down (Cappelle and Loock 2017), the results are still consistent with what is previously found with all the particles. The use of PVs is ranked as L1 translations>BNC > L2 translations (see Table 6). L1 translations contain a remarkably higher proportion of adverbials up, out, and down than BNC short stories and L2 translations contain less proportion of up, out, and down than BNC short stories. Overall, phrasal verbs containing the three top particles are slightly over-represented in translations when compared with BNC short stories.

The findings contradict what the unique item hypothesis predicts, as phrasal verbs are slightly more prevalent in Chinese–English translations compared to their occurrence in English originals.

When translation direction is considered, it is found that the representation of PVs diverges between different directions, that is, phrasal verbs are slightly underrepresented in L2 translations but remarkably overrepresented in L1 translations. This observation suggests that while phrasal verbs may exhibit an overrepresentation in translations compared to original English texts, this overrepresentation is predominantly influenced by the behavior of L1 translators. Contrarily, L2 translators tend to slightly underuse phrasal verbs. This divergence indicates that the unique item hypothesis is not a universal tendency as it is claimed, but instead is constrained by translation directionality.

What specific differences do L1 translations and L2 translations demonstrate in the use of phrasal verbs, with reference to the original English?

TTR, ARR, hapax legomena, and high-frequency PVs

To make an in-depth analysis of PV use in different directions, we ran a self-designed Python program to retrieve all the PV tokens, count the occurrences of the PV tokens, manually screen out the noisy items, lemmatize the tokens, and count the number of PV lemmas, and then output all these results to excel files.

The comparison of TTR, ARR, and Hapax between the translated and original English texts has yielded several findings (Table 7). Firstly, the TTR of the translated texts is lower than that of the BNC, with a value of 0.50 for translations compared to 0.62 for the BNC. This suggests that the translated texts contain a less diverse range of phrasal verbs compared to the original English texts. Secondly, the average repetition of each PV in the translated texts is higher than that in the BNC, with a value of 1.97 for translations compared to 1.59 for the BNC. This indicates a higher degree of repetitiveness and concentration in the usage of PVs in the translated texts. Thirdly, the proportion of PV hapax in the translated texts is much higher than that in the BNC. PV hapax accounts for 64% of all PVs in the translated texts, whereas the proportion of PV hapax is only 22% in the BNC. This indicates that the translated texts contain a much greater number of unique or rare PVs compared to the BNC, reflecting a higher level of creativity and distinctiveness in the use of phrasal verbs. These findings suggest that translated texts may be less diverse in their use of PVs, but they compensate for this by using some PVs more concentratedly and introducing a greater number of unique PVs.

Regarding translation directionality, it is found that the total counts of PVs in L1 translations are strikingly higher than that in L2 translations, the former being 2781 and the latter 1622; PV lemmas used by native translators are 1298 and 747 by non-natives. L1 translations contain almost twice as many distinct phrasal verbs as L2 translations, although the total L1 text length is only 11% more than that of L2 (see Table 1). Apparently, the numbers of both PV types and tokens in L1 translations are dramatically higher than those in L2 despite that they are translated from the same source texts. L1 translators use PVs much more valiantly and diversely than L2 translators. However, when examining lexical diversity as measured by TTR, no significant difference was observed between L1 and L2 translations, with the former being 0.50 and the latter 0.51. Similarly, ARR of PVs in L1 translations (2.01) is slightly higher than in L2 translations (1.98), but the difference is insignificant, suggesting a comparable repetition rate of PVs in both L1 and L2 translations. In terms of hapax legomena, L1 translators used 823 unique PVs, which is 1.7 times higher than the 481 used by L2 translators. However, the percentage of hapax legomena in both corpora is similar, around 63–64%. This indicates that hapax legomena account for more than half of the total PV lemmas in both L1 and L2 translations. The overall analysis indicates that L1 translators employ a more extensive range and a higher frequency of phrasal verbs compared to their L2 counterparts. However, when specific metrics are examined, such as PV lexical diversity, average repetition rates of each phrasal verb, and the percentage of hapax legomena, a closer similarity between L1 and L2 translations emerges. However, the PV lexical diversity, average repetition rates of each phrasal verb, and hapax percentage show more similarity between L1 and L2 translations. Despite these similarities in terms of type-token ratio (TTR), average repetition rate (AAR), and hapax proportion, the data suggests that L1 translators demonstrate a more diverse and varied use of phrasal verbs than L2 translators.

A comparison of the PV lists of L1 and L2 translations shows an overall similarity (Table 8). Specifically, the majority of the top 20 phrasal verbs are semantically transparent directional and semi-transparent aspectual phrasal verbs, with only turn out, make out, set out, and take on being semantically opaque in L1 translations and turn out and make up being semantically opaque in L2 translations. It is evident that both L1 and L2 translators use directional and aspectual phrasal verbs quite frequently, with L2 translators’ use even more remarkable than L1 translators.

It’s also found that the use of the top 20 PV lemmas takes up a substantial proportion of the total PV occurrences, accounting for about 1/5(21.5%) and 1/3(31.1%) of the total occurrences of PVs in L1 and L2 texts, respectively. The keyness of phrasal verbs used in L1 translations is lower than that in L2 translations, reconfirming that L1 translators have a more balanced and varied use of PVs than L2, while L2 translators rely more heavily on the high frequency PVs than L1 translators.

Keyword analysis of PVs

A keyword is defined as “a word which occurs with unusual frequency in a given text compared with a reference corpus of some kind” (Scott1997). A key PV in the context of the present study is a PV that occurs in L1 or L2 translational corpus more often than in BNC. It is calculated by carrying out a statistical test that compares the PV frequency in L1 and L2 corpus against those in BNC as a reference. Keyness is the statistical significance of a keyword’s frequency in the present corpus, relative to BNC-fiction.

To limit the data to a manageable range, the top ten key PVs are chosen for analysis (Table 9). It is evident that the key PVs used in L2 translations demonstrate a higher level of keyness than those in L1 translations, indicating that L2 translators exhibit a pronounced preference for and concentration on particular high-frequency PVs.

A semantic comparison of the ten key phrasal verbs used in L2 and L1 translations shows an overall difference. Specifically, almost all the key PVs used by L2 translators are comprised of a dynamic action verb such as go, come, rush, walk, or look, along with commonly used particles, either semantically transparent or semi-transparent. By contrast, among the ten key PVs used by L1 translators, only come along and stare up are semantically transparent, whereas all the others, including work up, take back, figure out, head back, let out, scrub up, head off, and throw in, are idiomatic in the context. The observation suggests that L2 translators may rely more on the semantically explicit PVs, probably due to their priority of achieving clarity and accuracy in translations. L1 translators, being native speakers of the target language, presumably with a greater command of linguistic nuances, use phrasal verbs of a higher level of diversity and balance between semantically implicit and explicit ones.

Key PV analysis reveals a distinct preference among L2 translators for literal PVs over idiomatic ones, a tendency not as pronounced in L1 translators who exhibit a more balanced usage across different PV categories. In Chinese–English translations, certain items in the source language act as catalysts for the use of directional and aspectual phrasal verbs in the target language, as in the case of “出去” in Chinese triggering the English phrasal verb “go out” in translations. However, there appears to be no direct linguistic trigger in the source text for the use of idiomatic phrasal verbs, making these idiomatic PVs genuinely unique items.

Discussion

The present study found that phrasal verbs are significantly overused in the translated texts in general compared to the non-translated texts. This result falsified the unique item hypothesis in general, but how does this happen? When translation directionality is considered, a significant divergence is observed between L1 and L2 translators. L1 translators significantly overuse phrasal verbs, while L2 translators slightly underuse them, resulting in an overrepresentation of phrasal verbs in translated texts primarily due to the significant overuse by L1 translators. While both L1 and L2 translators prefer to use semantically transparent phrasal verbs, L1 translators use more semantically opaque phrasal verbs than L2 translators.

L2 translators’ more limited and less frequent use of phrasal verbs and their favor for semantically transparent over semantically implicit phrasal verbs are in line with the tendency of L2 learners, but we think it insufficient to attribute these simply to translators’ strategic choice to minimize errors or ensure safety, given L2 translators’ language proficiency as professional bilinguals. Based on the gravitational pull hypothesis (Halverson 2017), it is highly possible that the use of phrasal verbs involves the translators’ cognitive process in which the translators may subconsciously choose to use or avoid phrasal verbs.

Gravitational pull model

Halverson’s gravitational pull hypothesis, initially proposed in 2003 and 2010 and later evolved into a cognitive linguistic model in 2017, offers insights into translation universals. This model outlines three key cognitive forces that shape translators’ choices of linguistic elements, as noted by Hareide (2013b) and Halverson (2010, 2017). These include the gravitational pull from highly salient features in the source language (Halverson 2017), the magnetism from salient or frequently used items in the target language, and the connectivity derived from the strength of links between elements in both the source and target languages. The combined effect and interaction of these forces ultimately determine the features of the translated texts. Our findings about the translation directionality add an important variable to this model, i.e., the translator. With reference to this model, L1 and L2 translators may be under different degrees of cognitive forces. For L2 translators, the gravitational pull is often stronger from the salient linguistic items of the source language because they are part of the source language culture. This indicates that while they may understand the source text well, the cognitive effort to translate idiomatic or culturally specific elements into the target language is greater. Their translations might be more literal and faithful to the source or less nuanced in terms of idiomatic usage, as the magnetism of their native language (which is now the source language) influences their cognitive processing. For L1 translators, the magnetism is towards the target language, which is their native tongue. They are deeply rooted in the cultural and linguistic nuances of the target language, causing them to produce translations that are more idiomatic and culturally resonant than L2 translators. This strong force of magnetism towards the native language allows L1 translators to navigate semantically complex constructs with greater ease and intuition.

In the specific case of idiomatic phrasal verbs, which are often semantically opaque and culturally loaded, these differences in the cognitive forces play a crucial role. L1 translators are more likely to use a higher frequency of these constructs due to the strong magnetism of phrasal verbs in the target language norms. L2 translators, without any gravitational pull of similar structures from their native language, might opt for more literal translations or may underuse such idiomatic expressions. These may help to explain why phrasal verbs are significantly overrepresented in L1 translations than the non-translated and L2 translated texts, and why phrasal verbs are slightly underrepresented in L2 translations.

For semantically transparent phrasal verbs, L1 and L2 translators may be similarly influenced by the force of connectivity and equally likely to select those correspondent and equivalent items in the Chinese–English language pair. Although L2 translators use phrasal verbs less frequently in general, they still prefer to use semantically transparent ones. As these types of phrasal verbs are perfectly equivalent in the Chinese–English language pair, all translators are supposed to experience the same forces of magnetism, gravitational pull, and connectivity. The corresponding items in the source and target languages especially exert a strong force of connectivity for translators, making them activated and readily available in translators’ minds, despite the translation directionality. The result confirms Halverson’s hypothesis (Halverson 2017) that the more established a link is between the source and target languages, the more likely it will be activated and used in translation, and vice versa”.

Traditionally, the gravitational pull model has focused on the influence of source and target languages’ salient features on translation choices. It considered factors like the saliency of linguistic elements and the strength of connections between the source and target language. However, this approach primarily views translation as a language-centered process, without explicitly considering the role of the translator, specifically, whether they are translating into their first language (L1) or second language (L2).

The present study broadens its scope and application boundaries by incorporating the crucial factor: the translation directionality, into the semantic network analysis. This expansion allows for a more comprehensive understanding of how the directionality of translation influences the decision-making process of translators, enhancing the model’s applicability in real-world scenarios.

Other possible explanations

The findings of the present study are not in line with what Cappelle and Loock (2017) found about the use of phrasal verbs in English translations done from Germanic and Romance languages. They found in translations done from Romance language, phrasal verbs are significantly underused when compared with non-translated texts in BNC; while no significant difference was found in the use of phrasal verbs between translations done from Germanic language and non-translated texts in BNC. Therefore, they propose that typological differences between source and target texts may result in a significant underuse of unique linguistic items, while typological similarities in the S-T language pair may result in no significant difference. In contrast, the present study didn’t find a similar tendency of significant underuse of phrasal verbs in the translated texts between the Chinese and English languages. Chinese belongs to the Sino-Tibetan language family, while English is part of the Indo-European family, making them far more distinct than the Romance and Germanic language pairs. It is possible that “typological difference shining through” (ibid.) may be more prominent when the language pair belongs to the same language family, but when the language pair is typologically more distant, like Chinese and English, translators may be more aware of the typological difference of the language pairs. This heightened awareness could lead them to emphasize the use of unique items typical of the target language, possibly to counterbalance the typological interference effect.

The discrepancy between L1 and L2 translations prompts an investigation into various influencing factors, including publication years. This inquiry is grounded in the historical evolution of phrasal verb usage in English, as illustrated in Fig. 4. Such a trend suggests that the chronological progression of PV usage might impact the translation choices in different eras. Particularly in fiction, there has been a steady increase in the use of PV since the 1800s, with a more pronounced escalation post-1900, as reported by Rodríguez-Puente (2019). Consequently, this chronological evolution in the usage of PV could be a significant factor influencing the variations in different translations.

Diachronic development of phrasal verb use in English originals (per 10,000 words). Note: Fig. 4 is referenced from Rodríguez-Puente (2019).

For instance, Wang’s translation of “Ah Q and Others, Selected Stories of Lusin” was published by Columbia University Press in 1941. In contrast, Yang’s “Complete Stories of Lu Xun” came out in 1981 through Indiana University Press in collaboration with Foreign Language Press. Later, Lyell’s “Diary of a Madman and Other Stories” was published by the University of Hawaii Press in 1999, and Lovell’s “The Real Story of Ah-Q and Other Tales of China: The Complete Fiction of Lu Xun” by Penguin Classics in 2010. The span of publication years for these works is as much as 40 years. Given this considerable temporal spread, the question arises: does the time difference in publication play a role in causing the divergence between L1 and L2 translations?

Given the chronological evolution of PV usage in English fiction, we may expect an order of PV use as Lovell (2010)>Lyell (1999)>Yang (1981)>Wang (1941), with Wang’s translations having the lowest and Lovell’s the highest frequency of PVs. And if the use of PVs increases steadily over time, we may expect a more remarkable difference between Wang and the other three translators, as there is forty years of time difference between Wang and the other three. However, the data reveals a different order (see Table 5): Lyell > Lovell > Yang > Wang, with Wang’s translations showing a slightly lower frequency of PVs (11.2‰) compared with Yang’s (12.7‰), but not significantly different. Lyell’s translations exhibit the highest frequency (19.2‰). This unexpected order challenges the assumption that the chronological evolution of PV use is the primary determinant of their frequency in translations. Instead, the data suggests that the time of publication may not play as decisive a role as previously thought. It points toward translation directionality as a more significant factor influencing the discrepancies in PV usage between L1 and L2 translations.

The unique style of the source texts may also be an important factor accounting for the results of the present study. The short stories by Lu Xun are written in vernacular Chinese and are rich in direct quotations and everyday conversations, marked by a colloquial, casual, and informal style, as noted by Zhan and Jiang (2017). Presumably, experienced translators may be well aware of this stylistic feature of the source texts and try to keep the original style in the target texts, as evidenced by the interview with Yang Xianyi (Qian, Almberg 2001). In other words, the translators’ sensitivity to Lu Xun’s distinctive narrative style and their conscientious efforts to reflect it in the target language could have overridden the expected patterns of PV usage as predicted by the UIH. Therefore, contrary to the UIH prediction of a significantly lower usage of phrasal verbs in translations when compared with the original English, L1 translated texts did not exhibit such a trend, and only L2 texts display a marginal underrepresentation. This finding underscores the complexity of translation as an art form, where linguistic choices are deeply intertwined with cognitive, cultural, and stylistic considerations, and where translators navigate between the source text’s idiosyncrasies and the target language’s norms to create a text that resonates with the source in both content and style.

Conclusion

This is the first study testing and investigating the unique item hypothesis from the perspective of translation directionality. It’s found L1 translators tend to normalize the target-language-specific features to make the translations sound native-like, resulting in the significant overuse and broader range and richness of the phrasal verbs; while L2 translators are comparatively more source-language-dependent, without the natural trigger of unique items in source language, they tend to slightly underuse the phrasal verbs. Despite both L1 and L2 translators showing a preference for semantically transparent phrasal verbs, it’s observed that L1 translators use more semantically opaque phrasal verbs compared to their L2 counterparts. The results have falsified the UIH in general and suggest that UIH is a conditional translation tendency constrained by translation directionality, or UIH is directionality-dependent.

The gravitational pull model is used to provide an explanation for the divergence in the representation of phrasal verbs between L1 and L2 translations. According to this model, three forces, i.e., gravitational pull, magnetism, and connectivity, interrelate and interact to shape translational texts. Both over- and under-representation of unique items is possible, depending on the specific structure of the bilingual semantic network activated (Halverson, 2010), and which force outweighs the other two. When the language pair and the translation task are both controlled, translation directionality is identified as an important factor influencing the translators’ cognitive processing. Specifically, L1 translators are under a stronger force of magnetism exerted by the target language, L2 translators are seemingly under more influence of the source language, and both the L1 and L2 translators are affected by the connectivity between the source and target texts. It is, therefore, proposed that the semantic network is not a closed system but with translation directionality as a vital variable that influences the interplay and the counteraction of the three cognitive forces.

Traditionally, research into the translation universal hypothesis has not taken translation directionality into account. The inclusion of translation directionality opens new avenues for future research. Upcoming studies could, for example, compare the translation outputs of L1 and L2 translators in various contexts to testify translation universals, investigate how translation directionality influences the handling of specific linguistic constructs, explore the psychological and cognitive aspects of translation from the perspective of L1 and L2 translators, etc.

Methodologically, the present study utilizes a source-text controlled corpus, which enables a finer granularity study and observation of the language phenomenon in the language pair, thus increasing the comparability of the data. This design significantly improves data comparability, making it particularly suitable for testing the translation universal hypothesis within the realm of corpus translation studies, which typically rely on large and balanced corpora, and thus can explore some boundary conditions for the applicability of translation universal tendencies.

However, even as a case study, the corpus size is not big enough yet, constrained by the controlled variables of the same source texts and the limited number of translators in each direction. Therefore, we only cautiously suggest considering the conditional factor of translation directionality when testing various translation universal tendencies and acknowledge that further academic justification and statistical evidence are required.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Beeby Lonsdale A (1998) Direction of Translation (directionality). In: Baker M (ed), Routledge encyclopedia of translation studies. Routledge, London/New York, p 63–67

Cappelle B (2012) English is less rich in manner-of-motion verbs when translated from French. Across Lang Cult 13(2):173–195. https://doi.org/10.1556/Acr.13.2012.2.3

Cappelle B, Loock R (2017) Typological differences shining through: The case of phrasal verbs in translated English. In: Sutter et al. (eds) Empirical translation studies: new methodological and theoretical traditions. De Gruyter Mouton, Berlin/Boston, p 235–262. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110459586-009

Chesterman A (2004) Beyond the particular. In: Mauranen A, Kujamaki P (eds) Translation universals: do they exist? Benjamins, Amsterdam, p 33–49

Chesterman A (2011) Reflections on the literal translation hypothesis. In: Alvstad C et al. (eds) Methods and strategies of process research: integrative approaches in translation studies. John Benjamins, Amsterdam/Philadelphia, p 23–35

Chou I, Liu KL, Zhao N (2021) Effects of directionality on interpreting performance: evidence from interpreting between Chinese and English by trainee interpreters. Front Psychol 12:781610. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.781610

Dagut M, Laufer B (1985) Avoidance of phrasal verbs: a case for contrastive analysis. Stud Second Lang Acquis 7(1):73–79. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263100005167

Darwin CM, Gray LS (1999) Going after the phrasal verb: an alternative approach to classification. TESOL Q 33(1):65–83. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588191

Ferreira A (2023) Directionality in cognitive translation and interpreting studies. In: Ferreira A, Schwieter JW (eds.) The Routledge handbook of translation, interpreting and bilingualism. Routledge, London

Fu WH (2011) Interpreting Gladys’ English translations under multiple cultural identities. Chin Translators J 6:16–20

Gardner D, Davies M (2007) Pointing out frequent phrasal verbs: a corpus‐based analysis. TESOL Q 41(2):339–359. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1545-7249.2007.tb00062.x

Halverson SL (2003) The cognitive basis of translation universals. Target Int J Translation Stud 15(2):197–241. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.15.2.02hal

Halverson S (2010) Cognitive translation studies: development in theory and method. In: Shreve GM, Angelone E (eds.) Translation and cognition. John Benjamins, Amsterdam/Philadelphia, p 349–369

Halverson S (2017) Gravitational pull in translation. Testing a revised model. In: De Sutter G, Lefer MA, Delaere I (eds.) Empirical translation studies. De Gruyter Mouton, Berlin, pp 9-45

Hareide L (2017a) The translation of formal source-language lacunas. An empirical study of the over-representation of target-language specific features and the unique items hypothesis. In: Ji M et al. (eds) Corpus methodologies explained. an empirical approach to translation studies. Routledge, London/New York, p 137–187

Hareide L (2017b) Is there gravitational pull in translation? A corpus-based test of the gravitational pull hypothesis on the language pairs Norwegian-Spanish and English-Spanish. In: Ji M et al. (eds) Corpus methodologies explained. an empirical approach to translation studies. Routledge, London/New York, p 188–231

Jia J et al. (2023) Translation directionality and translator anxiety: Evidence from eye movements in L1-L2 translation. Front Psychol 14:1120140. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1120140

Pokorn KN et al. (2020) The influence of directionality on the quality of translation output in educational settings. Interpreter Translator Train 14(1):58–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2019.1594563

Kenny D, Satthachai M (2018) Explicitation, unique items and the translation of English passives in Thai legal texts. Meta 63(3):604–626. https://doi.org/10.7202/1060165ar

Kenny D (2001) Lexis and creativity in translation: a corpus-based approach, 1st edn. Routledge, London. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315759968

Tomczak E, Whyatt B (2022) Directionality and lexical selection in professional translators: evidence from verbal fluency and translation tasks. Translation Interpreting 14(2):120–136. https://doi.org/10.12807/ti.114202.2022.a08

Kleinmann HH (1977) Avoidance behavior in adult second language acquisition. Lang Learn 27:93–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.1977.tb00294.x

Kullberg C, Watson D (2022) Vernaculars in an age of world literatures. Bloomsbury Academic, New York

Laufer B, Eliasson S (1993) What causes avoidance in L2 learning: L1-L2 difference, L1-L2 similarity, or L2 complexity. Stud Second Lang Acquis 15(1):35–48. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263100011657

Lefera MA, De Sutterb G (2022) Using the Gravitational Pull Hypothesis to explain patterns in interpreting and translation: The case of concatenated nouns in mediated European Parliament discourse. In: Kajzer-Wietrzny M et al.(eds) Mediated discourse at the European Parliament: empirical investigations in translation and multilingual natural language processing, vol 19. Language Science Press, pp 133–159

Li W et al. (2003) An Expert Lexicon Approach to Identifying English Phrasal Verbs. In: Proceedings of the 41st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Sapporo, Japan, p 513–520

Liao Y, Fukuya YJ (2004) Avoidance of phrasal verbs: the case of Chinese learners of English. Lang Learn 54(2):193–226. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2004.00254.x

Marco J, Oster U (2018) The gravitational pull of diminutives in Catalan translated and non-translated texts. Using Corpora in Contrastive and Translation Studies Conference, 5th edn., Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium

Marco J (2021) Testing the gravitational pull hypothesis on modal verbs expressing obligation and necessity in Catalan through the COVALT corpus. In: Bisiada M (ed) Empirical studies in translation and discourse. Language Science Press, Berlin, p 27–52

Pavlović N, Jensen K (2009) Eye tracking translation directionality. In: Pym A, Perekrestenko A (eds) Translation research projects 2. Intercultural Studies Group, Tarragona, p 93–109. http://isg.urv.es/publicity/isg/publications/trp_2_2009/index.htm

Qian DX, Almberg ES-P (2001) Interview with Yang Xianyi. Translation Rev 62(1):17–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/07374836.2001.10523795

Riguel E (2014) Phrasal verbs, “the scourge of the learner”. : 9th Lanc Univ Postgrad Conf Linguist Lang Teach 9:1–20

Rodríguez-Puente P (2019) The English Phrasal Verb, 1650-Present: history, stylistic drifts, and lexicalisation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Scott M (1997) PC analysis of key words—and key key words. System 25(2):233–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(97)00011-0

Siyanova A, Schmitt N (2007) Native and nonnative use of multi-word vs. one-word verbs. IRAL-Int Rev Appl Linguist Lang Teach 45(2):119–139. https://doi.org/10.1515/IRAL.2007.005

Tello I (2022) The translation of diminutives into Spanish: testing the unique items hypothesis with COVALT corpus. Book of Abstracts. Translation Transit 6:p190–p194

Tirkkonen-Condit S (2002) Translationese—a myth or an empirical fact? A study into the linguistic identifiability of translated language. Target. International Journal of Translation. Studies 14(2):207–220. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.14.2.02tir

Tirkkonen-Condit S (2004) Unique items—over-or under-represented in translated language? In: Mauranen A, Kujamäki P(eds). Translation universals: do they exist? John Benjamins, Amsterdam, p 177–184

Vilinsky B (2012) On the lower frequency of occurrence of Spanish verbal periphrases in translated texts as evidence for the unique items hypothesis. Across Lang Cult 13(2):197–210. https://doi.org/10.1556/Acr.13.2012.2.4

Wang BR, Li WR (2020) A comparative analysis of the translatorial habitus of Yang Xianyi and Gladys. Fudan J Foreign Lang Lit 01:141–146

Wang BR, Phil M (2011) Lu Xun’s Fiction in English Translation: the early years. Dissertation, University of Hong Kong http://hdl.handle.net/10722/173974

Wang YC, Wang KF (2013) The development of translator’s working patterns in rendering Chinese fictions into English. Foreign Lang Lit 29(2):118–124

Wei Y (2021) Use of English phrasal verbs of Chinese students across proficiency levels: a corpus-based analysis. Int J TESOL Stud 3(4):25–41. https://doi.org/10.46451/ijts.2021.12.03

Wierszycka J (2013) Phrasal verbs in learner English: a semantic approach. A study based POS tagged Spok Corpus learner Engl Res Corpus Linguist 1:81–93. https://ricl.aelinco.es/index.php/ricl/article/view/14

Xu ZH, Jiang Y, Zhan JH (2021) Direct and inverse translations of “Li Sao”: Emotion-related elements and reconstruction of Qu Yuan’s image. Foreign Lang Res 4:81–88. https://doi.org/10.13978/j.cnki.wyyj.2021.04.014

Yang XY (2002) White Tiger: An Autobiography of Yang Xianyi. The Chinese University Press, Hong Kong

Yang XY (2003) I Have Two Motherlands - Gladys and Her World. Guangxi Normal University Press, Guilin

Zhan JH, Jiang Y (2017) A study of the contractions in Chinese-English literary translation: a case study of Lu Xun’s novels. Foreign Lang Res 5:75–82. https://doi.org/10.13978/j.cnki.wyyj.2017.05.015

Zhan JH, Jiang Y (2023) A comparative study on the idiomaticity between native and non-native translations by comparing the use of phrasal verbs. J Xi’ Int Stud Univ 3:103–108. https://doi.org/10.16362/j.cnki.cn61-1457/h.2023.03.023

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Shaanxi Provincial Social Science Fund (Grant No. 2021K007).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the design of the work. The first author implemented the work, interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. The corresponding authors revised and proofread it. All authors approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors. Lu Xun’s short stories, the different versions of translations, and the BNC fictional corpus belong to the public domain. Informed consent is thus not applicable in the context of our specific study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhan, J., Jiang, Y. Testing the unique item hypothesis with phrasal verbs in Chinese–English translations of Lu Xun’s short stories: the perspective of translation directionality. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 344 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02814-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02814-y