Abstract

The purpose of this study is to understand the role of professional isolation and work–family balance (WFB) as talent retention strategies, considering organizational commitment (OC) and the mediating role of job satisfaction (JS) among IT employees in the technological industry have been forced by their companies to telework. While previous research has examined the connections between professional isolation (PI), OC, WFB, and JS separately in the context of teleworking, this research proposes an integrative model examining the connections between all these work-related constructs and allowing for mediating and moderating effects. It focuses on IT employees in the technological industry forced to telework, a setting underexamined by previous literature. The final sample is composed of 294 teleworkers forced to work partly at home by their companies. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was applied, and SmartPLS 4.0.8.7 software was used to analyze the data and test the hypotheses. Our results indicate a positive and significant direct effect of WFB on JS and OC, a negative and significant effect of PI on JS and OC, and a positive and significant effect of JS on OC. Our results also indicate that JS mediates the relationship between WFB and OC and between PI and OC and that neither time spent teleworking nor gender moderates the association between PI and OC. Overall, our results suggest that while PI negatively affects OC, JS, and WFB are the most relevant determinants of OC in the context of teleworking. In addition, a complementary IPMA analysis reinforces this view by suggesting that WFB and JS are the most important factors in determining OC performance among IT employees working from home, while PI is not important. The originality of this article is the proposal of an integrative model examining the connections between JS, WFB, PI, and OC and allowing for mediating (JS) and moderating (gender and percentage of time teleworking) effects from a talent management perspective. Moreover, this study focuses on information technology companies and the situation of forced remote working, two settings that have been underexamined. The results could help companies with forced teleworking develop effective strategies to attract, develop, and retain top talent in the information technology industry in the post-pandemic era. It is important for practitioners to consider the interactions between diverse work-related dimensions and the mediating and moderating effects between them to efficiently implement talent management strategies and reinforce OC and, in turn, economic performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 crisis had significant and lasting consequences in all areas of people’s lives. This global crisis triggered one of the most dramatic labor transformations in recent years (Carnevale and Hatak, 2020; Deschênes, 2023; Krehl and Büttgen, 2022), a scenario traditionally known as crisis management (Deschênes, 2023). Numerous academics began to study the new scenarios generated by the pandemic as crisis management in search of modifications to address the crisis (’t Hart et al., 2001). How organizations and people respond and adapt to crises has been and will continue to be marked by the pandemic. In this sense, talent management (TM) is one of the most effective human resource approaches employed during the COVID-19 pandemic (Vecch et al., 2021). One of the most widely applied schemes during the COVID-19 crisis was adjusting and adapting employees to a drastically altered work environment and offering them new and alternative workplace arrangements to retain them. In this context, TM (Lewis and Heckman, 2006) is especially relevant because, if companies want to properly manage their talent in adapting to the new ways of working, they should consider the objectives of their employees so they will stay motivated. In this sense, organizational commitment (OC) (Mowday et al., 1979) is a key predictor of employee retention (Porter et al., 1974). OC is a TM challenge in new teleworking scenarios (Da Silv et al., 2022) and in TM practices (Luna-Arocas and Lara, 2020). According to Luna-Arocas et al. (2020), if employees receive different types of noneconomic compensation, they will feel more linked to the organization.

Before the crisis, although well established in some organizations, remote work had a very low prevalence worldwide (Deschênes, 2023; Eurostat, 2020; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2019). However, its use has increased since the crisis, revealing advantages. Teleworking can offer employees flexibility regarding work hours and location, enabling remote collaboration and communication, and potentially improving JS and WFB and even productivity by, for example, reducing commuting stress (Carnevale and Hatak, 2020). However, it can also lead to feelings of constant connection and pressure to always be available, isolation from colleagues and company culture, and work–family imbalance or conflict, which can negatively impact JS and talent retention. That is, if it is poorly managed or made mandatory for employees, teleworking can also have negative conseqfiguences.

To better understand these associations, previous research has examined the connections between PI, OC, WFB, and JS separately in the context of teleworking (e.g., Ćulibr et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2020; Clai et al., 2021; Deschênes, 2023; Rochwulaningsih et al., 2023; Zhou and Nanakida, 2023), this research proposes a causal-predictive model, examining the connections between all those work-related constructs and allowing for mediating and moderating effects. In particular, our research objectives are as follows:

-

To understand the role of professional isolation (PI) and work–family balance (WFB) as talent retention strategies by considering organizational commitment (OC) and the mediating effect of job satisfaction (JS).

-

To examine the potential moderating role of gender and time spent teleworking on the relationships between PI, WFB, and OC.

-

To assess the predictive capability of the proposed model in the context of forced teleworking.

To conduct the analysis, this research examines data on IT employees in the Spanish technological industry who have been forced to telework by their companies, which is an underexamined setting in the previous literature, and it uses a multi-theoretical approach by considering the models of organizational support theory (Rhoades and Eisenberger, 2002), need-to-belong theory (Baumeister and Leary, 1995), and self-determination theory (SDT; Deci and Ryan, 2012). Specifically, it examines a sample composed of 297 teleworkers forced by their companies to work partly at home by their companies using partial least-squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) and SmartPLS 4.0.8.7 software.

Our results indicate a positive and significant direct effect of WFB on JS and OC, a negative and significant effect of PI on JS and OC, and a positive and significant effect of JS on OC. Our results also indicate that JS mediates the relationship between WFB and OC and between PI and OC and that neither gender nor time spent teleworking moderates the association between PI and OC. Overall, our results suggest that while PI negatively affects OC, JS, and WFB are the most relevant determinants of OC. Our results highlight the value of considering an integrative model of work-related outcomes, including WFB, IP, JS, and OC, to understand the role of WFB and non-IP as talent retention strategies in the teleworking context using a multi-theoretical approach. Our results could help companies with forced teleworking cultivate effective strategies to attract, develop, and retain top talent in the information technology industry in the post-pandemic era.

Literature review and theoretical framework

During the time of pandemic-induced teleworking, organizations played an essential role in supporting their employees. Organizational support theory (Rhoades and Eisenberger, 2002) is relevant for understanding how PI relates to employees’ satisfaction with teleworking. This theory is based on the premise that employees, to meet socioemotional needs and assess the organization’s readiness to reward their efforts, develop beliefs about how much the organization cares about their well-being and values their contributions. Need-to-belong theory (Baumeister and Leary, 1995) suggests that individuals have an innate desire to cultivate and maintain positive, trusting relationships with others with implications for their well-being. Therefore, developing meaningful relationships requires continuous and pleasant interactions (Kessler, 2013). In this sense, the need-to-belong theory can explain how the isolation of teleworkers can condition their ability to form connections with their coworkers. For example, Wang et al. (2020) conclude that telecommuters’ affective commitment is negatively associated with psychological isolation. Moreover, emotional connections with organizations are generated by the affective ties of individuals within the organization (Thye et al., 2014). The creation of links between people and organizations begins with frequent and positive social exchanges between individuals, benefiting OC, and the previous literature has shown that interactions between coworkers and superiors based on text messages and emails are worse than face-to-face interactions because they lack nonverbal cues (Daft and Lengel, 1984). In this sense, remote work can make it difficult for teleworkers to have efficient conversations with colleagues and superiors and can harm trust in labor relations, which is crucial for social health (Wheatley, 2012). Telecommuting can affect communication quality and the development of employment relationships. Telecommuters may interact and connect with colleagues and superiors less than employees who go to their workplaces daily, thereby increasing the PI of telecommuters.

In addition, self-determination theory argues that satisfying the basic psychological needs for relatedness and a sense of belonging among others is vital for employee well-being. When employees’ need for relatedness is satisfied, it makes them feel connected and supported by their work environment. In contrast, remote work reduces face-to-face interaction and interpersonal links between coworkers and supervisors (Golden, 2006).

Organizational commitment and perceived job satisfaction

OC is the most relevant factor in explaining organizational outcomes (Cater and Zabkar, 2009), and while there are different possible conceptualizations, they tend to cover three dimensions: affective, normative, and continuance (Allen and Meyer, 1990; Mowday et al., 1979; Wang et al., 2020). It can be defined as ‘the relative strength of an individual’s identification with and involvement in a particular organization’ (Mowday et al., 1979, p. 226). It represents the degree of identification with the values of an organization—affective; the willingness to make a significant effort to help the organization succeed—normative; and the desire to continue working in the organization—continuance (Ćulibr et al., 2018; Greenberg and Baron, 2008; Mowday et al., 1979).

Previous research has shown that JS, or the ‘pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job or job experiences’ (Mowday et al., 1979, p. 2), positively affects OC (Andreassen and Olsen, 2008; Ashill et al., 2008; Ćulibr et al., 2018; Mukherjee and Malhotra, 2006; Valaei and Rezaei, 2016). In fact, while the two concepts differ (for example, OC tends to be more stable than JS; Mowday et al., 1979; Porter et al., 1974), OC is an attitude that can be understood as ‘an extension of JS’ (Ćulibr et al., 2018, p. 8) because, while JS reflects the attitude toward one’s job (Ćulibr et al., 2018; Mowday et al., 1979), OC is a more global construct that reflects the employee’s attitude towards the organization as a whole (Ćulibr et al., 2018; Mowday et al., 1979). In fact, previous research has shown that JS mediates the effect of work environment attributes on OC (Valaei and Rezaei, 2016; Williams and Hazer, 1986).

Regarding the technological sector, previous research has also shown a positive relationship between JS and OC among teleworkers (Aban et al., 2019; Valaei and Rezaei, 2016); they may experience more JS than those who work in a traditional work environment as a result of less travel stress and stress from coworkers (Morganson et al., 2010).

Based on the above reasoning, and consistent with prior research, we hypothesize the following:

H1: JS has a positive, significant, and direct effect on OC.

Perceived professional isolation and organizational commitment

Following Golden et al. (2008), we define PI as the combination of psychological and physical isolation suffered by teleworkers. Psychological isolation is the extent to which employees feel disconnected from their colleagues and the company culture. Psychological isolation is ‘a state of mind or belief that one is out of touch with others in the workplace’ (Golden et al., 2008, p. 1412). It is related to the frustration of one’s inherent ‘desire to feel socially connected in the workplace’ (Golden et al., 2008, p. 1412) and the belief of having an insufficient connection to ‘critical networks of influence and social contact’ (Miller, 1975, p. 261). While not all teleworkers may necessarily suffer psychological isolation (Golden et al., 2008), teleworking, or ‘working anywhere other than the organization’s primary office(s)’ (Wang et al., 2020, p. 609), can have significant implications for psychological isolation, due to the physical isolation that teleworking involves (Wang et al., 2020). Physical isolation refers to teleworkers’ ‘physical separation from their colleagues’ (Wang et al., 2020, p. 610) and implies a lack of face-to-face interaction with colleagues and supervisors, which can lead to feelings of loneliness, decreased motivation, and reduced JS (Deschênes, 2023; Wang et al., 2020). Physically isolated workers tend to believe they are at a disadvantage with respect to working on-site because they feel they are ‘less respected in their organizations and possess fewer career advantages’ (Wang et al., 2020, p. 610).

Need-to-belong theory (Baumeister and Leary, 1995) argues that individuals have an inherent desire to develop and preserve reliable, meaningful, and positive connections to others, which are critical to well-being (Wang et al., 2020). Forming such relationships requires frequent and repeated interactions to acquire a perception of acceptance (Baumeister and Leary, 1995; Buss, 1991; Gainey et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2020). The absence of these relationships can lead to psychological isolation (Wang et al., 2020). Baumeister and Leary (1995) highlighted that merely being physically near others is important for relationship formation and that telework powerfully restrains opportunities for direct interactions (Bartel et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2020). According to Wang et al. (2020), computer communication tools cannot provide ‘the human touch’ that occurs during face-to-face interactions or generate informal and spontaneous exchanges between colleagues (Golden et al., 2008; Golden and Veiga, 2005; Smith and Rupp, 2002). Computer interactions hinder the development of meaningful emotional connections (Wang et al., 2020). With the impossibility of direct on-site control, some managers might perceive teleworkers as unreliable and increase communication with them using information communication technologies (ICTs) (Golden, 2006; Leonardi et al., 2004; Marsh and Musson, 2008; Wang et al., 2020). This can lead teleworkers to feel obliged to be constantly connected and available, untrusted, and in turn psychologically isolated (Wang et al., 2020).

Previous literature has shown that PI leads to job dissatisfaction (Bartel et al., 2012; Gainey et al., 1999; Golden and Veiga, 2005; McCloskey and Igbaria, 2003; Spilker and Breaugh, 2021). Spilker and Breaugh (2021) also found this relationship among teleworkers and argued that more complex relationships between JS and OC should be examined because other variables, such as the amount of time spent teleworking, could moderate this relationship. For example, with more remote work, the association between feelings of isolation and JS could decrease as the teleworker becomes more aware of the benefits of working off-site (due to, for example, fewer distractions or less travel time) that offset the effect of PI. Furthermore, over time, the teleworker could adapt to the lack of social interaction (Gajendran and Harrison, 2007). Self-determination theory (SDT; Deci and Ryan, 2012) is helpful in explaining the negative association between JS and PI. SDT is a motivational theory that argues that satisfying the basic psychological needs for relatedness, among others, is vital for employee well-being (Deci et al., 2001), satisfaction, and performance outcomes (Van denBroeck et al., 2008). Relatedness refers to the extent to which individuals feel accepted, connected with, and related to others (Baumeister and Leary, 1995). Previous research has shown that relatedness enhances the quality of employees’ work experience (Deschênes, 2023; Van den Broeck et al., 2010). As a result of PI, mandatory telework may reduce feelings of relatedness with colleagues and supervisors (Deschênes, 2023).

Based on the above theoretical approaches and results from previous research, we posit the following:

H2: PI has a negative, significant, and direct effect on JS.

Relatedly, previous research has shown that PI negatively affects OC (Hitlan et al., 2006; Mann and Holdsworth, 2003; Wang et al., 2020). According to the need-to-belong theory, employees look for occasions to interact with colleagues, take part in joint activities to confirm team acceptance, and do more than required in the organization to satisfy their need for meaningful relations (Wang et al., 2020). Such efforts may ‘generate trust, positive affect, and reciprocity among coworkers and create a sense of belonging’ (Wang et al., 2020, p. 612). Individuals create emotional ties with organizations through ‘frequent and positive social exchanges among individuals’ (Wang et al., 2020, p. 611). These positive connections between individuals may then be extended to the whole organization, leading to OC (Thye et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2020).

When these interpersonal connections between colleagues are disrupted by forced teleworking and PI, the ‘sense of organizational belonging, embeddedness, and obligation’ is harmed (Wang et al., 2020, p.612). Related research, such as Jung et al. (2021), has shown that the feeling of loneliness at work negatively affects OC. In contrast, Golden et al. (2008) found that teleworkers who experienced greater PI expressed less of a desire to leave the organization. This may be because the flexibility in the work and life spheres derived from telework (Golden and Wiens-Tuers, 2006) may outweigh any downside.

We therefore expect a negative relationship and posit the following:

H3: PI has a negative, significant, and direct effect on OC.

Work–family balance and organizational commitment

While some prepandemic research has shown the benefits of teleworking regarding reduced work-related stress and improved WFB (Charalampous et al., 2019), the COVID-19 pandemic and mandatory teleworking disrupted work and life routines (Carnevale and Hatak, 2020), for example, by increasing caregiving duties (Hu and Subramony, 2022; Lin and Meissner, 2020). Previous research has shown that perceived organizational support is vital for employee well-being during teleworking (Deschênes, 2023). While this support can take many different forms (Deschênes, 2023), we focus precisely on the WFB dimension, which is expected to be highly relevant for JS in the setting under study. Perceived organizational support derives from organizational support theory (Rhoades and Eisenberger, 2002), which suggests that workers build an overall perception of the organization’s interest in their well-being. This theory argues that the perception of organizational support generates a moral obligation among employees to support the organization and a sense of belonging to the organization. In turn, it increases employees’ well-being and JS (Deschênes, 2023). Previous research (Žnidaršič and Marič, 2021; Rahman et al., 2020, 2018; Haar, 2013; Ferguson et al., 2012; Greenhaus and Allen, 2011) has shown that WFB has a positive effect on job satisfaction, and this result is also confirmed by meta-analysis studies (Grawitch et al., 2013).

We, therefore, expect that perceived organizational support regarding WFB may improve JS and OC. Accordingly, we posit the following:

H4: WFB has a positive, significant, and direct effect on JS.

H5: WFB has a positive, significant, and direct effect on OC.

The mediating role of job satisfaction: the dispositional approach

There is extensive literature suggesting that JS is of special significance for understanding the impact of diverse variables on OC (Chatzopoulou et al., 2022; Djastuti, 2015; Williams and Hazer, 1986; Saridakis et al., 2020; To and Huang, 2022). For example, causal models of OC suggest that the effects of various antecedents, such as perceived job characteristics, on OC are mediated by JS (Ozturk et al., 2014; Williams and Hazer, 1986).

In recent years, much research effort has been devoted to exploring numerous antecedents of OC, but the focus has tended to be on environmental rather than dispositional sources, such as JS (Organ and Ryan, 1995). JS is relevant in our context because dispositional variables influence forced teleworkers’ perceptions of PI or WFB, leading to a better or worse predisposition to OC. In other words, we assume that being forced to telework predisposes individuals to lower levels of OC, but this negative predisposition can be counteracted with adequate levels of JS. Thus, it depends on whether employees perceive PI and WFB needs as obstacles to OC.

For example, Lok and Crawford (2001) concluded that although JS mediates the relationships between OC and leadership, culture, and subculture variables, JS did not substantially reduce the influence of any of the independent variables included in their study on OC. Ruiz-Palomo et al. (2020) concluded that JS mediates the relationship between implementing enrichment strategies and OC.

Recent studies focusing on teleworking have also shown that JS plays a mediating role in OC. For instance, Ababneh (2020) found that JS significantly mediates the relationship between the work environment and organizational commitment (OC) in the context of teleworking, and Awotoye et al. (2020) found the same result in the case of working mothers’ telecommuting. Sultana et al. (2021) also found that JS plays a mediating role between OC and employee performance among remote workers. These studies underscore the importance of considering JS as a mediator in teleworking settings.

Accordingly, we hypothesize the following:

H6: JS mediates the relationship between PI and OC.

H7: JS mediates the relationship between WFB and OC.

The moderating role of gender (GE) and the percentage of time spent teleworking (TST)

Ruiz-Palomo et al. (2020) concluded that gender moderates the relationship between enrichment strategies and OC in the hotel industry, suggesting an interest in a greater implementation of enrichment strategies for women.

When females have problematic interpersonal relationships, they are more easily distressed than males because they have higher expectations of their social relationships (Shear et al., 2000). Therefore, because women tend to be more sensitive due to those higher expectations, they may need more help in overcoming external work burdens.

There is also empirical evidence showing that women generally have more external workloads, which may reduce their OC (Shear et al., 2000; Yigit and Tatch, 2017). Based on these arguments, it can be assumed that women are more sensitive to PI derived from remote work and that they have more work-family conflict because of higher external workloads, such that their OC can be expected to be lower.

We also expect that the intensity with which employees perform telework will affect the impact of PI on OC. We expect that the perception of PI will negatively affect OC more intensively when the proportion of work time teleworking is high since the opportunities to overcome this perception of PI through face-to-face interactions with colleagues are reduced.

Based on the above arguments, we posit the following:

Hypothesis 8: GE will moderate the association between PI and OC in forced teleworkers.

Hypothesis 9: TST will moderate the association between PI and OC in forced teleworkers.

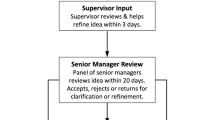

Figure 1 presents the theoretical model developed based on the literature review’s results.

The figure presents the importance-performance map analysis (IPMA) for organizational commitment (OC). This analysis visualizes the relative importance and performance of key factors influencing organizational commitment, helping to identify areas where improvements in performance would have the most significant impact.

Methodology

Research design and analytic procedure

This research adopts a purely quantitative approach, employing a cross-sectional survey design rooted in the post-positivism worldview assumptions (Creswell, 2012). Its focus lies on testing a theoretical model with an emphasis on explanation and prediction (Ghasemy et al., 2020; Henseler, 2017).

We used PLS-SEM (partial least squares and structural equation modeling) to estimate the overall model because this method is recommended when research focuses on the predictive performance of the model (Hair et al., 2017; Rigdon, 2016; Shmueli et al., 2016), as is the case here. SmartPLS 4.0.8.7 software (Ringle et al. 2015) was used to analyze the data and test the hypotheses. This study relied on the two-stage approach suggested by Hair et al. (2017) to evaluate the measurement and structural models. The measurement model was assessed by checking the reflective constructs’ reliability and validity, while the structural model was assessed by estimating the coefficient of determination (R2), Q2_predict values in the PLSpredict procedure, and path coefficients (Hair et al., 2019).

Sample and population

The target population of the present study was employees who work in a teleworking modality in the technological sector in Spain. Spain was a suitable environment for this research because, after the pandemic lockdown, many enterprises in this sector decided to adopt a teleworking strategy. The rate of implementation of teleworking in Spanish companies was one of the lowest in Europe before the pandemic; in Europe, 15% of employees teleworked, and in Spain, only approximately 4% of employees regularly worked from home before the COVID-19 crisis (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, 2020). However, according to Eurofound (2020), 36.3% of employees in the EU27 started teleworking full-time as a result of the pandemic (Blahopoulou et al. 2022).

The link to the questionnaire was distributed to employees through email listings via the snowball method. The process began with a convenience sampling of 30 teleworkers from technology companies listed in the directory of the Spanish Association of Technology Parks (https://apte.org/empresas), within the category of ‘computer science and telecommunications’, which comprises 1074 companies. The questionnaire was sent via email, inviting them to participate and encouraging them to forward the survey link to at least two colleagues in that sector who also teleworked, preferably from companies other than theirs. They were also invited to report on the sampling process so that their colleagues could, in turn, continue forwarding the questionnaire to others in the target group.

Before they gained access to the instrument, the participants were informed about the objectives of the study and that participation was voluntary and anonymous. The questionnaire was shown only when they provided their consent to participate by clicking a tick box. A screening question was posed to exclude employees who did not belong to the target group. At the end of the questionnaire, the participants were thanked and encouraged to continue spreading it among other colleagues in the specified category.

Using a convenience sampling method, the data were collected through an online questionnaire-based survey from January to March 2021. Of the final total of 297 surveys obtained, none were incomplete since the form required all questions to be filled out before it could be submitted. Thus, none were discarded, ensuring that the maximum missingness rate per indicator was <1% (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2013). Then, we focused on identifying multivariate outliers (Ghasemy et al., 2020). In doing so, the computation of squared Mahalanobis distance indicated the multivariate non-normal nature of the data. Similarly, this analysis detected multivariate outliers (Byrne, 2016) revealing the presence of 3 extreme outlying cases that were excluded from the dataset. The removal of the outlying cases was mainly because they were considerably different from other cases as well as their potential influence on the findings (Hair et al., 2017). This provided us with further support in terms of the applicability of our nonparametric PLS method in estimating the model from an explanatory–predictive perspective (Ghasemy et al., 2022).

The final valid questionnaires consisted of 294 teleworkers (belonging to 294 companies) with a mean age of 36.42 years (SD = 8.39); 63.61% were male and 48.64% teleworked more than 50% of their working day (see Table 1). In order to measure the representativeness of the sample, since there is no census of teleworkers, we consider the population to be the number of companies within the category of ‘computer science and telecommunications’ (1074 companies). Therefore, the sample size (294 companies in this category) results in a sampling error rate of 4.87% (95% confidence level, p = q = 0.5). This error rate is low enough to be taken into consideration for a statistical study in social sciences (Lakens, 2022; Taherdoost, 2017).

G*Power version 3.1.9.2 software was used to conduct an a priori statistical power analysis and compute the minimum sample size for our study (Faul et al., 2009). With a desired statistical power level of 0.95, a confidence level of 0.99, an anticipated effect size of 0.15, and a predictor variable number of three, it was revealed that the minimum sample size needed to estimate the proposed model was 119 respondents, which is less than our final sample of 297 (Sarstedt et al., 2023).

In accordance with the recommendations of Kock (2015) and Kock and Lynn (2012), this research showed an absence of common method bias (CMB). The procedure involved a random latent variable that was dependent on all the other variables in the model. This new variable (CMB) approached the variables as potential antecedents and included the necessary indicators. In this regard, the variance inflation factors needed to yield a value lower than 3.3 to ensure that the sample was not influenced by CMB. Table 2 shows that the obtained values for every construct in the model were within the recommended threshold.

Measures and covariates

The model constructs were measured through reflective measurement scales validated in previous research. In all cases, 7-point Likert scales were used (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree). Since the original scales were in the English language and the target population was Spanish, to maintain the accuracy of the original scales, the questionnaire was translated into Spanish by a professional service. PI was measured by four items adapted from the eight original items used by Golden et al. (2008). This decision was made to simplify the questionnaire, as the professional translator indicated that the items were very similar when translated into Spanish; JS was measured through five items adapted from Pond and Geyer (1991); OC was measured through four items adapted from Meyer and Allen (1991); and WFB was measured through five items adapted from Thompson et al. (1999) (see Table 3).

The choice to approach the variables as reflective constructs was made based on precedent in the literature. However, we recognize the importance of a well-founded rationale. Reflective and formative constructs are defined by the manner of their application rather than an inherent characteristic. Hence, we re-evaluated our approach by considering existing studies that utilize the same items for these variables.

Reflective constructs are those where the latent variable is assumed to cause the observed variables (indicators), meaning changes in the latent variable will be reflected in changes in the indicators. This conceptualization is based on the understanding that the indicators are manifestations of the underlying construct. For instance, in our study, professional isolation (PI) is treated as a reflective construct. This is because various indicators (such as feelings of loneliness and disconnection from colleagues) are seen as outcomes that reflect the underlying level of professional isolation experienced by teleworkers. Our decision is supported by numerous studies in the literature, such as Deschênes (2023), Ficapal-Cus et al. (2023), and Golden et al. (2008), which have consistently used similar items to measure PI reflectively.

Similarly, organizational commitment (OC) is considered to be a reflective construct. OC is typically defined by indicators such as emotional attachment to the organization, willingness to exert effort on behalf of the organization, and desire to maintain membership in the organization. These indicators are considered effects of the underlying commitment construct. The reflective nature of OC is widely accepted in organizational research, as evidenced by foundational works by Meyer and Allen (1991), Meyer et al. (1993), Francis and Lingard (2004), and Norton (2009). Our literature review did not reveal any significant studies that treated OC as a formative construct, particularly in the context of teleworking. Moreover, in the specific context of teleworking, reflective measurement has been the norm (Tanpipat et al., 2021).

However, constructs such as work–family balance (WFB) and job satisfaction (JS) have been employed in both reflective and formative modes in the literature. To ensure the appropriateness of the reflective model for these constructs in our study, we applied confirmatory tetrad analysis-PLS (CTA-PLS), as recommended by Gudergan et al. (2008). This mode of analysis helps determine whether the reflective specification is suitable by examining tetrad differences. Our results show that all confidence intervals included zero for each construct, confirming the reflective nature of WFB and JS (see Table 4). This methodological rigor strengthens the validity of our measurement model and ensures that our constructs are appropriately specified.

The application of the CTA-PLS method has reinforced our approach, providing additional validity to our findings. Conducting this analysis allowed us to verify that the reflective mode is not only consistent with previous literature but also statistically appropriate for our data. By confirming the reflective nature of these constructs, we can confidently interpret the relationships and effects within our structural model, thereby enhancing the robustness and credibility of our study’s conclusions.

In addition, before collecting the data, three experts reviewed the questionnaire to enhance question comprehension without altering the meanings of the original scales. Then, a pretest was performed with a sample of 30 undergraduate students who had prior experience in teleworking. The Cronbach’s alpha values exceeded 0.80 (Nunnally, 1978). The final survey questionnaire consisted of one screening question (if they were forced to telework), 18 items designed to measure the four model constructs, and two other questions (gender and time spent on teleworking as a percentage of their working day).

Results

Measurement model assessment

Table 5 shows the results of the evaluations of construct reliability and convergent validity. Three items (JS4, OC3, and PI3) were excluded from the model because their factorial loads did not exceed 0.7. After implementing these adjustments, all measurements, including Cronbach’s alpha (CA), Dijkstra–Henseler’s rho (p_A), and composite reliability (CR), consistently surpassed the minimum criterion of 0.8 suggested by Nunnally and Bernstein (1994). Similarly, the average variance extracted (AVE) values for all the constructs were >0.5, as recommended by Fornell and Larcker (1981).

Following Hair et al. (2019), two valid PLS-SEM methods were employed to ensure discriminant validity: the Fornell–Larcker criterion (inter-construct correlations must be less than the square root of the average variance extracted) and the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT) (correlations must be < 0.9). Table 6 shows that all recorded values remained below the suggested thresholds, confirming the discriminant validity of the measurements and, therefore, that the structural model was deemed appropriate for analysis.

Structural model assessment

To assess the empirical significance of the hypothesized relationships and the predictive relevance of the proposed model, the structural model was evaluated. Through a bootstrapping procedure with 10,000 subsamples, the significance of the coefficient paths was assessed (Hair et al., 2011). Table 7 shows that all the model hypotheses were supported, except H8 and H9.

The predictive capacity values of the model are shown in Table 8. Specifically, the R2 values of all the constructs were >0.1 (Falk and Miller, 1992). The predictive capacities of the dependent constructs and the endogenous variables were also measured using the Q2 value in the PLSpredict procedure (Shmueli et al., 2016). All the values were positive, so the proposed model has predictive relevance. In addition, all the variance inflation factors (VIFs) in the inner model were under 3.3, and collinearity was not present between the constructs.

In the final step, we evaluated the model’s predictive power on out-of-sample data. We conducted PLSpredict analysis (Shmueli et al., 2019) using the default settings (10 folds and 10 repetitions) and focused on OC as the primary target construct.

All Q2_predict values in the PLS results section were above zero, and the mean absolute error (MAE) statistics for one out of three items in the PLS results section were lower than the MAE values for the items derived from the linear model (LM). Therefore, we concluded that the proposed model’s out-of-sample predictive performance was low (Ghasemy et al., 2022; Shmueli et al., 2019). The detailed PLSpredict results are presented in Table 9.

In terms of direct effects, the results show a positive and significant influence of WFB on JS (β = 0.478, p < 0.001) and OC (β = 0.360, p < 0.001), supporting H4 and H5, respectively. In addition, the results indicated that PI has a negative and significant effect on JS (β = −0.470, p < 0.001) and OC (β = −0.070, p < 0.05). Therefore, H2 and H3 are supported. Furthermore, the findings indicate the positive and significant influence of JS on OC (β = 0.508, p < 0.001), supporting H1 (see Table 7).

In terms of indirect effects, the results indicate the mediating role of JS in the relationship between WFB and OC (β = 0.243, p < 0.001) and in the relationship between PI and OC (β = −0.210, p < 0.001). Thus, H6 and H7 are supported (see Table 7).

In terms of moderating effects, the results indicate that both GE (β = 0.025, p < 0.353) and TST (β = 0.054, p < 0.205) have no moderating influence on the relationship between PI and OC; thus, H8 and H9 are rejected (see Table 7). This is why we stopped continuing the moderation analysis using a permutation-based multigroup analysis. Likewise, the control variables (GE and TST) have no moderating effect on the dependent variable (OC).

Unobserved heterogeneity assessment

Following Sarstedt et al.’s (2023) systematic procedure for identifying unobserved heterogeneity in PLS path models, we first ran the FIMIX-PLS procedure on the data. Following Matthews et al. (2016), we initiated the procedure by assuming a one-segment solution, using the default settings for the stop criterion (10–9 = 1.0E−9), the maximum number of iterations (5000), and the number of repetitions (10). To determine the maximum number of segments to extract, we first computed the minimum sample size required to estimate each segment. The results of a post hoc power analysis assuming an effect size of 0.15, three predictors, and a power level of 80% suggest that the minimum sample size requirement is 77, which allows for extracting a maximum of three segments. We, therefore, reran FIMIX-PLS for two to three segments using the same settings as in the initial analysis.

The results of the fit indices for the one- to three-segment models show that all the indicators (AIC, AIC3, AIC4, BIC, CAIC, HQ, MDL5, LnL) point to a one-segment solution (Table 10). We therefore assume that unobserved heterogeneity is not at a critical level, which supports the results of the analysis of the entire dataset.

Importance-performance map analysis (IPMA)

According to Ringle and Sarstedt (2016), the objective of IPMA is to identify predecessor constructs that exhibit relatively low performance but are highly important for the target constructs. An increase of one unit in the performance of a predecessor construct will enhance the performance of the target construct by an amount equal to the total effect size (i.e., importance) of that predecessor construct.

In our study, OC was the target construct, as predicted by three predecessors: PI, JS, and WFB. We conducted an IPMA for this study, and the results are shown in Fig. 2. The lower right area of the importance-performance map indicates that WFB has the highest importance score of 0.603. Thus, if companies increase their WFB performance by one unit, their overall organizational commitment (OC) will increase by 0.603, all other factors being equal. PI has the lowest importance score of −0.280. This means that if teleworkers’ PI performance increases by one unit, their overall organizational commitment (OC) will decrease by 0.280, all other factors being equal.

Additionally, our findings reveal that the technological companies analyzed have the lowest performance score for professional isolation (PI), at 32.634. This suggests that there is significant room for improvement in this area. The complete list of importance-performance values is provided in Table 11.

Discussion

Our results show that, as expected, PI negatively affects OC, while WFB positively affects OC. A plausible explanation for this finding is that individuals with PI are concerned that they may miss out on workplace interactions if they work at home. Our finding is consistent with the idea that when teleworkers experience PI, they feel disconnected and are less likely to seek the frequent interactions with coworkers that are necessary to create positive emotions, leaving their need for interpersonal connections and a sense of belonging unmet (Golden et al., 2008). Consequently, in the absence of positive connections with coworkers, teleworkers’ sense of belonging, rootedness, and obligation to the organization is likely to erode, weakening their OC (Morganson et al., 2010; Mulk et al., 2009; Thye et al., 2014).

Our WFB results are consistent with those of numerous studies that have concluded that work–family benefits (i.e., telework, health and wellness programs, childcare, and older adult care) were positively associated with OC. Moreover, our results also suggest that companies should consider employees’ JS to better understand the forces driving OC since JS mediates the effects of WFB and PI on OC.

Our results do not confirm the hypotheses that the gender of employees and the intensity with which they telework might be important for OC. In particular, we find that the negative effect of PI on OC among telecommuters is not influenced by gender or the amount of time spent teleworking. According to our results, whether employees work from home a few days a week or full-time, this negative impact is still significant.

Our results from the PLS-SEM analysis suggest that companies should pay attention to the perception of PI among those employees. That is, companies should monitor those perceptions more closely and think about strategies to overcome them. Practices such as mentoring programs specifically designed for telecommuters or informal meetings where they can share their experiences could be of value.

However, another finding that deserves special mention is that, to the best of our knowledge, this paper is the first to show that, in a telework context in the IT sector, WFB and JS have a greater positive influence on OC than the negative influence of PI. This, therefore, broadens the scope of the study of OC by providing an approach where IP, in the IT sector, does not seem to be a relevant problem. In addition, our complementary IPMA analysis reinforces this conclusion by showing that WFB and JS are the most important factors in determining OC performance, while PI does not seem to be important. That is, our results suggest that companies in the IT sector can encourage teleworking because the benefits appear to be greater than the costs.

Conclusions

In a context where society promotes and values innovation and sustainability as a solution to the challenges ahead, many organizations are rushing to rethink and look for ways to transform their existing organizational models towards digitization. This context can lead to higher levels of innovation, better customer service, and a stronger competitive advantage for the company.

Since the post pandemic era, in practice, there has been a major reorganization of work based on digitalization and telework. However, at the theoretical level, there is little conceptual clarity at the base of a multitude of similar streams of research on the modalities and modifications of work (Schäfer et al., 2023). In very generic terms, a recent study concluded that because of reduced social connectivity, digital onboarding has a significant impact on employee outcomes (Sani et al., 2022). In the tech industry, teleworking has become increasingly prevalent due to the pandemic, and studies have found that it has both positive and negative impacts on work outcomes in that industry. Nakrošienė et al. (2019) identified reduced communication with coworkers, supervisor trust and support, and the suitability of the home as a workplace as important factors in generating positive telework outcomes. For example, some teleworkers report increased JS due to reduced commute time and increased flexibility, while others report decreased JS due to increased workload and difficulty separating work and family (e.g., Abid et al., 2020). Studies have shown that teleworkers who receive social support from their supervisors and colleagues report higher levels of JS and that emotional intelligence can buffer the negative impact of stress on JS. Even in the gaming industry, after the outbreak of COVID-19, the OC of teleworkers who perceived organizational support was affected directly and indirectly through JS (To and Huang, 2022).

The crisis also raised concerns about job security and the potential impact of economic uncertainty on JS. For example, Zeng and Wang (2020) found that job insecurity was negatively related to employee JS in the technology industry. A widely accepted idea in management and human resources, discussed and supported by many authors, is that studying the relationship between JS, perceived PI, WFB, and OC in the context of (forced) teleworking in the technology industry is critical for developing effective TM strategies to manage remote teams, promote employee well-being and JS, and enhance organizational outcomes. In this sense, Mahjoub et al. (2018) confirm that strategic TM would improve OC, thus proving our reflection on the importance of TM in OC. In addition to increased JS, OC is one of the most widely recognized benefits of working remotely. In the technological sector, Chakra and Charef (2022) concluded that there was a positive correlation between teleworking and OC. Similarly, Taboroši et al. (2020) concluded that remote employees show stronger OC and trust at work than conventional employees.

Theoretical, practical, and methodological implications

Concerning the implications for theory, while previous research has examined the connections between PI, OC, WFB, and JS separately in the context of teleworking, this research highlights the value of using an integrative model to examine the connections between all those work-related constructs and allowing for mediating and moderating effects. Another theoretical implication is the absence of a moderating effect of GE and TST on the relationship between PI and OC. This provides an avenue for future research in terms of studying the moderating effect of GE and TST between the antecedents of OC and this construct.

Our results also highlight the value of using a multi-theoretical approach and a talent management perspective to better understand the opposing effects of teleworking on work-related outcomes found in the previous literature. Regarding practical implications, our results suggest that practitioners should consider the interactions between diverse work-related dimensions and the mediating and moderating effects between them to efficiently implement talent management strategies and reinforce OC and, in turn, economic performance. The results could help companies with forced teleworking develop effective strategies to attract, develop, and retain top talent in the information technology industry in the post-pandemic era. The results from a complementary IPMA analysis suggest that WFB and JS are the most important factors in determining IT employees’ OC performance through teleworking, while PI does not seem to be important for OC performance. That is, these results suggest that PI is not a main concern among those employees, while WFB and JS are key determinants of their OC. These results have relevant implications for companies that are seeking to enhance OC among IT teleworkers. In particular, they indicate that companies should prioritize managerial actions that improve employees’ WFB, for example, offering online psychological training and consultation programs for employees to ensure that they have comprehensive knowledge in the area of work-life balance (Ghasemy and Elwood, 2023).

Regarding methodological implications, in the field of organizational commitment, particularly in the context of teleworkers in the technological industry, our paper can serve as a guide by highlighting the essential steps in evaluating PLS path models based on the latest proposed guidelines (Hair et al., 2019) and demonstrating the application of advanced PLS methods (Ringle et al., 2020).

Theoretical, practical, and methodological limitations

Despite its valuable insights, this study has several limitations that future research should strive to overcome. First, future works could consider a necessary condition analysis (NCA) to identify the must-have factors required for organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Second, while the current study focused on the perspectives of HR managers, it is important to gather input from workers themselves to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the current state of organizations. This type of research would not only complement existing knowledge but also provide a holistic view, incorporating the analysis of documents and interviews with diverse organizational stakeholders. By doing so, we can better address potential issues and create a more positive and productive work environment for all. Third, this study uses a cross-sectional design and, therefore, cannot identify cause-and-effect relationships; future research could perform analyses using longitudinal modeling to justify causality, for example, using new methodologies such as PLSe2 (Ghasemy, 2022; Ghasemy and Elwood, 2023; Bentler and Huang, 2014). Fourth, the snowball method used to collect the data in this study is not random, but it was selected because we do not know the universe of teleworkers in the analyzed sector since there is no “census” of such workers. Future research could include the conducting of such a census of teleworkers to allow for the use of random sampling methods. Fifth, this research uses a multi-theoretical approach based on three selected theories (organizational support theory by Rhoades and Eisenberger, 2002; need-to-belong theory by Baumeister and Leary 1995; and self-determination theory by Deci and Ryan, 2012). Future research could enrich the analysis by exploring alternative theoretical lenses. The moderating role of GE and TS in the relationship between PI and OC should be analyzed for other teleworkers and in different contexts (geographical and sectorial) since our study focused on the period immediately after the pandemic lockdown, and that situation could have conditioned the results. Finally, future research could also control for other variables that could affect the results, such as job type, company type, work experience, educational level, and marital status (Ghasemy and Elwood, 2023).

Data availability

The authors made the data available in the supplementary files.

References

Ababneh KI (2020) Effects of met expectations, trust, job satisfaction, and commitment on faculty turnover intentions in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Int J Hum Resour Man 31(2):303–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1255904

Aban CJI, Perez VEB, Ricarte KKG, Chiu JL (2019) The relationship of organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and perceived organizational support of telecommuters in the national capital region. Rev Integr Bus Econ Res 8:162–197

Abid H, Mohd J, Raju V (2020) Effects of COVID-19 pandemic in daily life. Curr Med Res Pract 24(3):45–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmrp.2020.03.011

Allen NJ, Meyer JP (1990) The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization. J Occup Psychol 63(1):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00506.x

Andreassen TW, Olsen LL (2008) The impact of customers’ perception of varying degrees of customer service on commitment and perceived relative attractiveness. Manag Serv Qual: Int J 18(4):309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/09604520810885581

Ashill NJ, Rod M, Thirkell P, Carruthers J (2008) Job resourcefulness, symptoms of burnout and service recovery performance: An examination of call center frontline employees. J Serv Mark 22(5):395–406. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876040810889132

Awotoye Y, Javadian G, Kpekpena I (2020) Examining the impact of working from home on a working mother’s organizational commitment: the mediating role of occupational stress and job satisfaction. J Organ Psychol 20(2). https://doi.org/10.33423/jop.v20i2.2877

Bartel CA, Wrzesniewski A, Wiesenfeld BM (2012) Knowing where you stand: physical isolation, perceived respect, and organizational identification among virtual employees. Organ Sci 23(3):743–757. https://doi.org/10.2307/23252086

Baumeister RF, Leary MR (1995) The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol Bull 117(3):497. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Bentler PM, Huang W (2014) On components, latent variables, PLS and simple methods: reactions to Rigdon’s rethinking of PLS. Long Range Plann 47(3):138–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2014.02.005

Blahopoulou J, Ortiz-Bonnin S, Montañez-Juan M, Torrens Espinosa G, García-Buades ME (2022) Telework satisfaction, wellbeing, and performance in the digital era: lessons learned during COVID-19 lockdown in Spain. Curr Psychol 41(5):2507–2520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02873-x

Buss DM (1991) Evolutionary personality psychology. Annu Rev Psychol 42(1):459–491. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.42.020191.002331

Byrne BM (2016) Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 3rd edn. Routledge, New York

Carnevale JB, Hatak I (2020) Employee adjustment and well-being in the era of COVID-19: implications for human resource management. J Bus Res 116:183–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.037

Cater B, Zabkar V (2009) Antecedents and consequences of commitment in marketing research services: the client’s perspective. Ind Mark Manag 38(7):785–797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2007.10.004

Chakra R, Charef F (2022) The effect of telework on organizational commitment, case of IT Engineers Casablanca Rabat region. Int J Acc Financ 23(12):789–801. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6582487

Charalampous M, Grant CA, Tramontano C, Michailidis E (2019) Systematically reviewing remote e-workers’ well-being at work: a multidimensional approach. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 28(1):51–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2018.1541886

Chatzopoulou EC, Manolopoulos D, Agapitou V (2022) Corporate social responsibility and employee outcomes: interrelations of external and internal orientations with job satisfaction and organizational commitment. J Bus Ethics 179:795–817. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04872-7

Ćulibr J, Deli M, Mitrović S, Ćulibrk D (2018) Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and job involvement: the mediating role of job involvement. Front Psychol 9:132. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00132

Clai R, Gordon M, Kroon M, Reilly C (2021) The effects of social isolation on well-being and life satisfaction during a pandemic. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8:1. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00710-3

Creswell JW (2012) Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research, 4th edn. Pearson, Boston, MA

Da Silv AB, Castelló-Sirvent F, Canós-Daró L (2022) Sensible leaders and hybrid working: challenges for talent management. Sustainability 14(24):16883. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416883

Daft RL, Lengel RH (1984) Information richness: a new approach to managerial behavior and organization design. In: Staw B, Cummings LL (eds) Research in organizational behavior, vol 6. JAI, Greenwich, CT, pp. 191–233

Deci EL, Rya R, Gagné M, Leone DR, Usunov J, Kornazheva BP (2001) Need satisfaction, motivation, and well-being in the work organizations of a former Eastern Bloc country: a cross-cultural study of self-determination. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 27:930–942. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167201278002

Deci EL, Ryan RM (2012) Self-determination theory. In: Van Lange PAM, Kruglanski AW, Higgins ET (eds) Handbook of theories of social psychology. Sage Publications, pp. 416–436

Deschênes AA (2023) Professional isolation and pandemic teleworkers’ satisfaction and commitment: the role of perceived organizational and supervisor support. Eur Rev Appl Psychol 73(2):100823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erap.2022.100823

Djastuti I (2015) The influence of job characteristics on job satisfaction, organizational commitment and managerial performance a study on construction companies in Central Java. Int Res J Bus Stud 3(2):145–166

Eurostat (2020) Data retrieved from Eurostat database. You can access their reports and publications via Eurostat

Falk R, Miller N (1992) A primer for soft modeling. University of Akron Press

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG (2009) Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods 41(4):1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

Ferguson M, Carlson D, Zivnuska S, Whitten D (2012) Support at work and home: the path to satisfaction through balance. J Vocat Behav 80(2):299–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.001

Ficapal-Cus P, Torrent-Sellens J, Palos-Sanchez P, González-González I (2023) The telework performance dilemma: exploring the role of trust, social isolation and fatigue. Int J Manpow 45(1):155–168. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-08-2022-0363

Francis V, Lingard H (2004) A Quantitative study of work–life experiences in the public and private sectors of the Australian construction industry. For Construction Industry Institute, Australia Inc., Australia. Brisbane, 142 pp

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18(1):39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

Gainey TW, Kelley DE, Hill JA (1999) Telecommuting’s impact on corporate culture and individual workers: examining the effect of employee isolation. SAM Adv Manag J 6(4):4

Gajendran RS, Harrison DA (2007) The good, the bad, and the unknown about telecommuting: meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences. J Appl Psychol 92(6):1524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1524

Ghasemy M (2022) Estimating models with observed independent variables based on the PLSe2 methodology: a Monte Carlo simulation study. Qual Quant 56:4129–4415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-021-01297-2

Ghasemy M, Elwood JA (2023) Job satisfaction, academic motivation, and organizational citizenship behavior among lecturers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-national comparative study in Japan and Malaysia. Asia Pac Educ Rev 24:353–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-022-09757-6

Ghasemy M, Mohajer L, Cepeda-Carrión G et al. (2022) Job performance as a mediator between affective states and job satisfaction: a multigroup analysis based on gender in an academic environment. Curr Psychol 41:1221–1236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00649-9

Ghasemy M, Teeroovengadum V, Becker J-M, Ringle CM (2020) This fast car can move faster: a review of PLS-SEM application in higher education research. High Educ 80:1121–1152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00534-1

Golden L, Wiens-Tuers B (2006) To your happinesaTo your happiness? Extra hours of labor supply and worker well-beings. J Socio-Econ 35(2):382–397

Golden TD (2006) Avoiding depletion in virtual work: Telework and the intervening impact of work exhaustion on commitment and turnover intentions. J Vocat Behav 69(1):176–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2006.02.003

Golden TD, Veiga JF (2005) The impact of extent of telecommuting on job satisfaction: resolving inconsistent findings. J Manag 31(2):301–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206304271768

Golden TD, Veiga JF, Dino RN (2008) The impact of professional isolation on teleworker job performance and turnover intentions: does time spent teleworking, interacting face-to-face, or having access to communication enhancing technology matter? J Appl Psychol 93(6):1412–1421. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012722

Greenhaus JH, Allen TD (2011) Work-family balance: A review and extension of the literature. In: Quick JC, Tetrick LE (eds) Handbook of Occupational Health Psychology, 2nd edn. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, pp 165–183

Gudergan SP, Ringle CM, Wende S, Will A (2008) Confirmatory tetrad analysis in PLS path modeling. J Bus Res 61(12):1238–1249

Grawitch MJ, Maloney PW, Barber LK, Mooshegian SE (2013) Examining the nomological network of satisfaction with work–life balance. J Occup Health Psychol 18(3):276–284. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032754

Greenberg J, Baron RA (2008) Behavior in organizations: understanding and managing the human side of work. Pearson Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ

Haar JM (2013) Testing a new measure of WLB: a study of parent and non‐parent employees from New Zealand. Int J Hum Resour Manag 24(17/18):3305–3324. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.775175

Hair JF, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2011) PLS-SEM: indeed, a silver bullet. J Mark Theory Pract 19(2):139–152. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

Hair JF, Risher JJ, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM (2019) When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus Rev 31(1):2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Hair JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2017) A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage Publications

Henseler J (2017) Partial least squares path modeling. In: PSH Leeflang, JE Wieringa, THA Bijmolt, Pauwels Koen H (eds). Advanced methods for modeling markets. Springer, Heidelberg, pp. 361–381

Hitlan RT, Cliffton RJ, DeSoto MC (2006) Perceived exclusion in the workplace: the moderating effects of gender on work-related attitudes and psychological health. N Am J Psychol 8(2):217–236

Hu X, Subramony M (2022) Disruptive pandemic effects on telecommuters: a longitudinal study of work–family balance and well‐being during COVID-19. Appl Psychol 71(3):807–826. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12387

Instituto Nacional de Estadística (2020) Reports and data available from INE

Jung HS, Song MK, Yoon HH (2021) The effects of workplace loneliness on work engagement and organizational commitment: moderating roles of leader-member exchange and coworker exchange. Sustainability 13(2):948. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020948

Kessler EH (ed) (2013) Encyclopedia of management theory. Sage Publications, Pace University, USA

Kock N (2015) Common method bias in PLS-SEM: a full collinearity assessment approach. Int J E-Collab 11(4):1–10. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijec.2015100101

Kock N, Lynn GS (2012) Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: an illustration and recommendations. J Assoc Inf Syst 13(7):546–580. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00302

Krehl EH, Büttgen M (2022) Uncovering the complexities of remote leadership and the usage of digital tools during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative diary study. Ger J Hum Resour Manag 36(3):325–352. https://doi.org/10.1177/23970022221083697

Lakens D (2022) Sample size justification. Collabra: Psychol 8(1):33267. https://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.33267

Leonardi PM, Jackson MH, Marsh NN (2004) The strategic use of distance among virtual team members: a multi-dimensional communication model. In: Godar S, Ferris SP (eds) Virtual and collaborative teams: process, technologies, and practice. Idea Group, Hershey, PA, pp. 156–172

Lewis RE, Heckman RJ (2006) Talent management: a critical review. Hum Resour Manag Rev 16:139–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2006.03.001

Lin Z, Meissner CM (2020) Health vs. wealth? Public health policies and the economy during COVID-19 NBER Working Papers 27099, National Bureau of Economics Research

Luna-Arocas R, Danvila-Del Valle I, Lara FJ (2020) Talent management and organizational commitment: The partial mediating role of pay satisfaction. Empl Relat 42(4):863–881. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-11-2019-0429

Luna-Arocas R, Lara FJ (2020) Talent management, affective organizational commitment, and service performance in local government. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(13):4827. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134827

Lok P, Crawford J (2001) Antecedents of organizational commitment and the mediating role of job satisfaction. J Manag Psychol 16(8):594–613. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000006302

Mahjoub M, Atashsokhan S, Khalilzadeh M, Aghajanloo A, Zohrehvandi S (2018) Linking “project success” and “strategic talent management”: satisfaction/motivation and organizational commitment as mediators. Proc Comp Sci 138:764–774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2018.10.100

Meyer JP, Allen NJ (1991) A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum Resour Manag Rev 1(1):61–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/1053-4822(91)90011-Z

Meyer JP, Allen NJ, Smith CA (1993) Commitment to organizations and occupations: extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. J Appl Psychol 78(4):538–551. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.4.538

Mann S, Holdsworth L (2003) The psychological impact of teleworking: stress, emotions, and health. N Technol Work Employ 18(3):196–211. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-005X.00121

Marsh K, Musson G (2008) Men at work and at home: managing emotion in telework. Gend Work Organ 15(1):31–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2007.00353.x

Matthews LM, Sarstedt M, Hair JF, Ringle CM (2016) Identifying and treating unobserved heterogeneity with FIMIX-PLS: Part II–A case study. Eur Bus Rev 28(2):208–224

McCloskey DW, Igbaria M (2003) Does ‘out of sight’ mean ‘out of mind’? An empirical investigation of the career advancement prospects of virtual workers. Resour Manag J 16:19–34. https://doi.org/10.4018/irmj.2003040102

Miller J (1975) Isolation in organizations: alienation from authority, control, and expressive relations. Adm Sci Q 2:260–271. https://doi.org/10.2307/2391698

Morganson VJ, Major DA, Oborn KL, Verive JM, Heelan MP (2010) Comparing telework locations and traditional work arrangements: differences in work–life balance support, job satisfaction, and inclusion. J Manag Psychol 25(6):578–595. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941011056941

Mowday RT, Steers RM, Porter LW (1979) The measurement of organizational commitment. J Vocat Behav 14(2):224–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(79)90072-1

Mukherjee A, Malhotra N (2006) Does role clarity explain employee‐perceived service quality? A study of antecedents and consequences in call centers. Int J Serv Ind Manag 17(5):444–473. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564230610689777

Mulk J, Bardhi F, Lassk F, Nanavaty-Dahl J (2009) Set up remote workers to thrive. MIT Sloan Manag Rev 51:62–69

Nakrošienė A, Bučiūnienė I, Goštautaitė B (2019) Working from home: characteristics and outcomes of telework. Int J Manpow 40(1):87–101. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-07-2017-0172

Norton J (2009) Employee organisational commitment and work–life balance in Australia Carpe Diem Aust J Bus Inform 4(1):1–7

Nunnally J (1978) Psychometric theory, vol 2. McGraw-Hill, New York

Nunnally J, Bernstein I (1994) Psychometric theory, 3rd edn. McGraw-Hill, New York

Organ DW, Ryan K (1995) A meta‐analytic review of attitudinal and dispositional predictors of organizational citizenship behavior. Pers Psychol 48(4):775–802. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1995.tb01781.x

Ozturk AB, Hancer M, Im JY (2014) Job characteristics, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment for hotel workers in Turkey. J Hosp Mark Manag 23(3):294–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2013.796866

Pond SB, Geyer PD (1991) Differences in the relation between job satisfaction and perceived work alternatives among older and younger blue-collar workers. J Vocat Behav 39(2):251–262

Porter LW, Steers RM, Mowday RT, Boulian PV (1974) Organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover among psychiatric technicians. J Appl Psychol 59(5):603–609

Rahman MM, Ali NA, Jantan AH, Mansor ZD, Rahaman MS (2020) Work to family, family to work conflicts and work-family balance as predictors of job satisfaction of Malaysian academic community. J Enterp Communities 14(4):621–642. https://doi.org/10.2478/orga-2021-0015

Rahman MM, Ali NA, Mansor ZD, Jantan AH, Samuel AB, Alam MK, Hosen S (2018) Work–family conflict and job satisfaction: the moderating effects of gender. Acad Strateg Manag J 7(5):1–6. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.1.2018.812.1157.1169

Rochwulaningsih Y, Sulistiyono ST, Utama MP et al. (2023) Integrating socio-cultural value system into health services in response to Covid-19 patients’ self-isolation in Indonesia. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10:162. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01629-7

Rhoades L, Eisenberger R (2002) Perceived organizational support: a review of the literature. J Appl Psychol 87(4):698–714. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.698

Ringle C, Da Silva D, Bido D (2015) Structural equation modeling with the SmartPLS. Braz J Mark 13(2)

Ringle CM, Sarstedt M, Mitchell R, Gudergan SP (2020) Partial least squares structural equation modeling in HRM research. Int J Hum Resour Man 31(12):1617–1643

Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2016) Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Handbook of Market Research 15:587–632

Rigdon EE (2016) Choosing PLS path modeling as analytical method in European management research: a realist perspective. Eur Manag J 34(6):598–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2016.05.006

Ruiz-Palomo D, Leon-Gomez A, García-Lopera F (2020) Disentangling organizational commitment in the hospitality industry: the roles of empowerment, enrichment, satisfaction, and gender. Int J Hosp Manag 90:102637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102637

Saridakis G, Lai Y, Muñoz Torres RI, Gourlay S (2020) Exploring the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment: an instrumental variable approach. Int J Hum Resour Man 31(13):1739–1769. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1423100

Sani KF, Adisa TA, Adekoya OD, Oruh ES (2022) Digital onboarding and employee outcomes: empirical evidence from the UK. Manag Decis 61(3):637–654. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-11-2021-1528

Sarstedt M, Hair JH, Ringle CM (2023) “PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet” – retrospective observations and recent advances. J Mark Theory Pract 31(3):261–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/10696679.2022.2056488

Schäfer B, Koloch L, Storai D, Gunkel M, Kraus S (2023) Alternative workplace arrangements: tearing down the walls of a conceptual labyrinth. J Innov Knowl 8(2):100352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2023.100352

Shear MK, Feske U, Greeno C (2000) Gender differences in anxiety disorders: Clinical implications. In: Frank E (ed) Gender and its effects on psychopathology. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC, pp. 151–165

Shmueli G, Sarstedt M, Hair JF, Cheah J-H, Hiram T, Vaithilingam S, Ringle CM (2019) Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: guidelines for using PLSpredict. Eur J Mark 53(11):2322–2347. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-02-2019-0189

Shmueli G, Ray S, Estrada JMV, Chatla SB (2016) The elephant in the room: predictive performance of PLS models. J Bus Res 69(10):4552–4564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.03.049

Smith AD, Rupp WT (2002) Communication and loyalty among knowledge workers: a resource of the firm theory view. J Knowl Manag 6(3):250–261

Spilker MA, Breaugh JA (2021) Potential ways to predict and manage telecommuters’ feelings of professional isolation. J Vocat Behav 131:103646. https://doi.org/10.3390/info13110545

Sultana R, Rana S, Mirza R (2021) The impact of job satisfaction on employee performance. Int J Manag Stud 18(2):85–98

’t Hart P, Heyse L, Boin A (2001) New trends in crisis management practice and crisis management research: setting the agenda. J Conting Crisis Manag 9(4):181–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.00168

Taboroši S, Strukan E, Poštin J, Konjikušić M, Nikolić M (2020) Organizational commitment and trust at work by remote employees. J Eng Manag Compet 10(1):48–60. https://doi.org/10.5937/jemc2001048T

Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS (2013) Using multivariate statistics, 6th edn. Pearson, Boston

Tanpipat W, Lim HW, Deng X (2021) Implementing remote working policy in corporate offices in Thailand: strategic facility management perspective. Sustain Sci 13(3):1284

Taherdoost H (2017) Determining sample size; how to calculate survey sample size. Int J Econ Manag Syst 2:237–239

To WM, Huang G (2022) Effects of equity, perceived organizational support, and job satisfaction on organizational commitment in Macao’s gaming industry. Manag Decis 9:2433–2454. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-11-2021-1447

Thompson CA, Beauvais LL, Lyness KS (1999) When work–family benefits are not enough: the influence of work–family culture on benefit utilization, organizational attachment, and work–family conflict. J Vocat Behav 54(3):392–415. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2000.1774

Thye SR, Vincent A, Lawler EJ, Yoon J (2014) Relational cohesion, social commitments, and person-to-group ties: twenty-five years of a theoretical research program. Adv Group Process 31:99–138. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0882-614520140000031008

U.S. Bureau of Labour Statistics (2019) Reports available from BLS

Valaei N, Rezaei S (2016) Job satisfaction and organizational commitment: an empirical investigation among ICT-SMEs. Manag Res Rev 39(12):1663–1694. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-09-2015-0216

Van den Broeck A, Vansteenkiste M, De Witte H, Lens W (2008) Explaining the relationships between job characteristics, burnout, and engagement: the role of basic psychological need satisfaction. Work Stress 22(3):277–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370802393672

Van den Broeck A, Vansteenkiste M, De Witte H, Lens W (2010) Capturing autonomy, competence, and relatedness at work: Construction and initial validation of the work-related basic need satisfaction scale. J Occup Organ Psychol 83(4):981–1002. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317909X481382

Vecch A, Della Piana B, Feola R, Crudele C (2021) Talent management processes and outcomes in a virtual organization. Bus Process Manag J 27(7):1937–1965. https://doi.org/10.1108/BPMJ-06-2019-0227

Wang W, Albert L, Sun Q (2020) Employee isolation and telecommuter organizational commitment. Empl Relt Int J 42(3):609–625. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-06-2019-0246

Williams LJ, Hazer JT (1986) Antecedents and consequences of satisfaction and commitment in turnover models: a reanalysis using latent variable structural equation methods. J Appl Psychol 71(2):219. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.71.2.219

Wheatley D (2012) Good to be home? Time-use and satisfaction levels among home-based teleworkers. N Technol Work Employ 27(3):224–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-005X.2012.00289.x

Yigit E, Tatch K (2017) Investigating the effects of job satisfaction on employee performance in higher education. J Bus Res 10(2):127–140

Zeng J, Wang Z (2020) Digital leadership: How leaders manage in the era of digital transformation. J Bus Res 118:42–51

Žnidaršič J, Marič M (2021) Relationships between work-family balance, job satisfaction, life satisfaction, and work engagement among higher education lecturers. Organizacija 54(3):227–237. https://doi.org/10.7595/management.fon.2021.0008

Zhou YF, Nanakida A (2023) Job satisfaction and self-efficacy of in-service early childhood teachers in the post-COVID-19 pandemic era. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10:721. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02174-z

Acknowledgements