Abstract

During the 2015–2016 academic year, racial protests swept across college campuses in the U.S. These protests were followed by large university investments in initiatives to promote diversity, which combined with existing diversity dynamics, have helped to shape recent faculty diversity trends. We document diversity trends among faculty in STEM and non-STEM fields since the protests in 2015–2016. We find that recent diversity trends are narrowing the gender gap among faculty in STEM and non-STEM fields, but widening racial-ethnic gaps, especially among Black faculty. A large body of prior research suggests these trends will affect students’ college experiences and how they choose majors.

Similar content being viewed by others

There is long-standing interest among researchers and policymakers in the racial-ethnic and gender diversity of university faculty (Griffin, 2019). Advocates for diversifying the faculty argue diversity has many benefits, including (1) it promotes a variety of perspectives and experiences in the curriculum (Deo et al. 2010; Hurtado, 2001), (2) it fosters a sense of belonging and encourages broader engagement among students (Whittaker et al. 2015; Zambrana et al. 2015), and (3) it helps to break down stereotypes and biases with regard to what success looks like in academia (O’Meara et al. 2020). Calls to increase faculty diversity have been around for decades but gained a new sense of urgency when racial protests swept across college campuses in the U.S. during the 2015–2016 academic year (Griffin, 2019; Hartocollis and Bidgood, 2015).

Following the 2015–2016 protests, universities made large investments aimed at improving diversity along many dimensions, including among faculty. For example, in 2016 the University of Michigan pledged $85 million to complete a strategic plan for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI), in addition to its existing $40 million annual budget (Allen, 2016). Similarly, in 2015 Yale launched a five year, $50 million initiative to improve faculty diversity (Salovey and Polak, 2015). More broadly, from 2015 to 2019 the share of universities with a Chief Diversity Officer increased by almost twenty percentage points (Bradley et al. 2022). Diversity investments at many universities have emphasized racial-ethnic diversity, but gender diversity has also been prominent in DEI initiatives. Gender diversity has been of long-standing policy interest, especially in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) fields, and has been supported by major federal programs for decades (e.g., NSF ADVANCE). The emphasis on gender diversity in recent university efforts is exemplified by newly formed committees such as the Louisiana State University Council on Gender Equity and the Commission on Women and Gender Equity in Academia at the University of Rochester.

Universities’ efforts to improve faculty diversity have centered primarily on hiring practices. For instance, a common strategy is to appoint “diversity advisors” to faculty hiring committees. Among other things, these advisors provide implicit bias training, monitor the procedures and outreach efforts of hiring committees, review the diversity of applicant pools and interview lists, compile and report relevant diversity data for job searches, and assist hiring committees in posting job descriptions.Footnote 1 Likely as a result of these and other, related efforts, job postings for academic positions have increasingly emphasized diversity—in a 2021 study of almost 1000 faculty job postings, Paul and Maranto (2021) report that 68 percent mentioned diversity and 19 percent required a diversity statement. Among selective universities in the top 100 of U.S. News and World Report rankings, these percentages jump to 78 and 34, respectively. In addition, some universities established postdoctoral programs designed to complement standard recruiting practices and enhance diversity. Lehigh University’s Advancing Future Faculty Diversity Postdoctoral Scholars Program is an example. Lehigh describes this initiative as creating a “professional opportunity for scholars with diverse backgrounds, experiences, and perspectives, including those historically underrepresented in the academy, who possess a commitment to inclusive excellence as they prepare for future tenure track appointments at Lehigh or elsewhere.”Footnote 2 The emphasis of these initiatives on hiring practices suggests that their impacts will be most readily observed in the diversity of newly hired faculty.

Li and Koedel (2017) document racial-ethnic and gender diversity among faculty at the time of the protests using data from the 2015-16 academic year. They show Black, Hispanic, and female professors are underrepresented among faculty, and that this is especially true in STEM fields. They further show these same groups are less likely to complete PhDs in STEM fields relative to non-STEM fields, suggesting the PhD pipeline contributes to the cross-field diversity imbalance (also see Ginther et al. 2010; Parsons, 2023).Footnote 3 Li and Koedel (2017) raise the concern that efforts to diversify the faculty in the wake of the protests, if not carefully targeted, may serve to reinforce existing racial/ethnic and gender imbalances between STEM and non-STEM fields. Specifically, they argue that because the supply of qualified Black, Hispanic, and female applicants for faculty positions is greater in non-STEM fields, untargeted policies would be prone to build greater diversity in these fields, exacerbating existing gaps. They write: “If an aim of diversifying the faculty is to promote better long-term outcomes for underrepresented students, targeted efforts to increase diversity in STEM fields may need to be an explicit objective. However, STEM-specific considerations do not seem to be prominent in current policy discussions on faculty diversity.” (Li and Koedel, 2017, p. 351).

Undergirding the concern of Li and Koedel (2017) is one of the most consistent findings in research on student-teacher interactions at both the K-12 and postsecondary levels: students perform better when exposed to more demographically matched instructors (e.g., see Bettinger and Long, 2005; Carrell et al. 2010; Dee, 2004; Egalite et al. 2015; Fairlie et al. 2014; Gershenson et al. 2022; Gottfried et al. 2022; Hoffman and Oreopoulos, 2009; Lindsay and Hart, 2017; Price, 2010). A subset of this literature at the postsecondary level further shows college students are more likely to complete classes, and majors, in fields when they experience a demographic match with a professor (Bettinger and Long, 2005; Carrell et al. 2010; Fairlie et al. 2014; Price, 2010). The implication is that relative diversity between STEM and non-STEM fields can affect students’ educational trajectories. Given evidence that STEM degrees have higher labor market returns (Carnevale et al. 2015), even conditional on measures of students’ cognitive and non-cognitive skills (Webber, 2016), the relative diversity of faculty in STEM fields has implications for equity inside and outside of academia. Furthermore, noting that today’s students are tomorrow’s faculty, it also has implications for future faculty diversity.

We contribute to the literature on faculty diversity by examining diversity trends in STEM and non-STEM fields from 2015-16 to 2022-23. Trends during this period reflect the influence of universities’ recent diversity investments combined with broader diversity dynamics in academia. Contrary to the concern raised by Li and Koedel (2017), we find the share of female faculty in STEM fields has been increasing at a faster rate than in non-STEM fields. Because female faculty are more common in non-STEM fields, this is helping to narrow the cross-field faculty gender gap. However, the shares of Black and Hispanic faculty are increasing at a slower rate in STEM fields than in non-STEM fields, widening racial-ethnic representation gaps across fields. These cross-field differences are driven primarily by changes in the composition of assistant professors, which suggests a role of recent, hiring-centric university efforts to diversify the faculty. We do not believe these trends are well understood because available large-scale datasets on faculty do not include information on faculty fields.

Results

Data Overview

We use two data sources for our analysis. The first data source is the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS). IPEDS data are valuable because they are comprehensive (IPEDS includes data from all universities in the U.S. that participate in federal student financial aid programs) and information on faculty demographics has been collected in a uniform way that permits the construction of long-term trends. However, a limitation of IPEDS is that there is no information about faculty fields, making it impossible to study cross-field trend heterogeneity. We address this limitation with our second data source, which is a unique panel dataset we constructed based on the original dataset used by Li and Koedel (2017). We refer to this dataset as the “L&K dataset.” The key feature of the L&K dataset that makes our analysis possible is that we identify faculty by field.

We use IPEDS data on public R1 universities (i.e., doctoral-granting universities with high research activity) to document broad diversity trends among tenured and tenure-track faculty. Our IPEDS data cover the academic years 2001-02 through 2021-22 and include between 102,592-115,297 individual faculty each year. The L&K dataset is a department-level panel dataset covering all tenured and tenure-track faculty in 120 academic departments at 40 public universities originally sampled by Li and Koedel (2017). The 40 universities are (approximately) the 40 highest-ranked public universities in the 2016 U.S. News & World Report rankings and we refer to them as “selective universities” for ease of presentation throughout.Footnote 4 They are listed in Appendix Table A1. Li and Koedel (2017) collected the first wave of data during the 2015-16 academic year. In the spring of 2023, we conducted a follow-up data collection of the same departments to construct the data panel. Waves 1 and 2 of the L&K dataset include 4139 and 3851 individual faculty, respectively.

The original Li and Koedel (2017) sampling frame covered six academic departments: biology, chemistry, economics, English, educational leadership and policy, and sociology. Acknowledging some ambiguity in which fields should be defined as STEM, for our primary field comparison we categorize biology, chemistry, and economics as STEM fields, and English, educational leadership and policy, and sociology as non-STEM fields. We also show our findings are similar if we use narrower definitions of STEM and non-STEM fields—specifically, if we categorize only biology and chemistry as STEM, and only English and sociology as non-STEM (see below). Details about the original Li and Koedel data collection in 2016, and our follow-up in 2023, are provided in the methods section below.

Baseline Conditions & Data Comparability in 2015–2016

Table 1 reports summary statistics from IPEDS and the L&K dataset in 2015–2016 (hereafter we denote academic years by the spring year—e.g., 2015-16 as 2016). Columns 1 and 2 use IPEDS to compare all public R1 universities and the 40-university subsample that matches the L&K dataset. The full sample and 40-university subsample are very similar demographically in IPEDS. Columns 2 and 3 compare the IPEDS data to the L&K dataset for the same universities. The datasets are similar, although small differences arise for several reasons.

We briefly identify three factors that contribute to differences between IPEDS and the L&K dataset. First, IPEDS asks about faculty gender (though only in two categories: men and women) whereas the L&K dataset codes faculty sex. The similarity of the gender/sex shares in IPEDS and the L&K dataset, shown at the bottom of columns 2 and 3 in Table 1, suggests the substantive implication of the gender/sex coding difference is negligible for tracking diversity trends. Or said differently, sex as coded in the L&K dataset appears to be a good proxy for gender as coded in IPEDS, and vice-versa.Footnote 5 For ease of presentation, but without substantive import (or intent), we use the terms “gender” and “sex” interchangeably. Second, in terms of race/ethnicity, two notable categories are represented in IPEDS but not in the L&K dataset: multi-race faculty (0.7 percent in IPEDS) and non-resident alien faculty (i.e., faculty who are not U.S. citizens and do not have a green card; 4.4 percent in IPEDS). In addition, IPEDS has a larger share of faculty with unknown race-ethnicity (2.0 percent versus 0.2 percent in the L&K dataset). Finally, a third and more general source of potential differences between the datasets is that IPEDS covers faculty in all fields, whereas the L&K dataset covers faculty in just six fields. To the extent the six fields covered in the L&K dataset are not representative of faculty in all fields, some differences may emerge. Noting these issues, on the whole we interpret Table 1 as showing that IPEDS and the L&K dataset are broadly aligned.

The last two columns of Table 1 use the L&K dataset to document differences in faculty representation between STEM and non-STEM fields in 2016. Consistent with prior research, large gaps in gender and racial-ethnic representation are apparent in the data. For instance, the share of Black faculty in non-STEM fields is more than seven times larger than in STEM fields (9.9 percent versus 1.3 percent). Hispanic faculty are also disproportionately in non-STEM fields, though the gap is less extreme (5.2 versus 3.3 percent). These field differences for Black and Hispanic faculty are offset by differences in the opposite direction for Asian and White faculty, with the imbalance in favor of STEM being particularly large for Asian faculty. Turning to gender, female faculty account for 48.6 of faculty in non-STEM fields, but just 25.5 percent of faculty in STEM fields.

Trends in Faculty Diversity

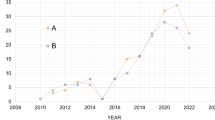

Figure 1 provides context for our analysis of STEM and non-STEM fields by documenting broad trends in faculty diversity since 2002 using IPEDS. Trends in faculty shares by race-ethnicity and gender are reported overall and by faculty rank. For consistency of presentation, we restrict the university sample in Fig. 1 to match the universities in the L&K dataset (from column 2 of Table 1), but below we confirm the trends are nearly identical for the full sample of public R1 universities in IPEDS.Footnote 6

Notes. Data are from IPEDS for the L&K university sample. A is for Asian faculty, B is for Black faculty, C is for Hispanic faculty, D is for White faculty, and E is for female faculty. Odd-numbered years prior to 2017, and 2010, are omitted because reporting on faculty demographics in IPEDS was optional in these years. The racial-ethnic percentages in any given year do not sum to 100 because there are other racial-ethnic IPEDS categories not shown (see Table 1). The vertical scale is in percentage points and different in each graph to show trends over time for the different groups at appropriate scale.

Figure 1 shows that university faculty are becoming more diverse, and that this broad trend predates the protests in 2016. Panel D shows the share of White faculty has declined persistently between 2002 and 2022, falling from 83 to 66 percent overall. Correspondingly, Panels A-C show the shares of Asian, Black, and Hispanic faculty all increased, albeit with different patterns of growth. The Asian faculty share has more than doubled since 2002, increasing from 7.7 to 16.0 percentage points. The trend in the Asian assistant professor share is flat during the latter half of the data panel, but this is offset in the total trend by increases at the associate and full levels. The total Black faculty share increased only slightly since 2002, rising from just 3.3 to 3.8 percent. Recently, however, there is a sharp increase in the Black assistant professor share, which has grown by almost 40 percent since 2016 (albeit off a low base of just 4.2 percentage points). The Hispanic faculty share at the beginning of the data panel was slightly below the Black faculty share, but it has grown much faster, roughly doubling since 2002. Like with Black faculty, there is a more distinct increase in the share of Hispanic assistant professors toward the end of our data panel.Footnote 7

Turning to gender, panel E shows a persistent increase in the representation of women among faculty since 2002. Overall, the share of women increased from 25 to 36 percent. At the assistant professor level and as of 2022, the share of women is approaching gender parity, at 47 percent. Women’s assistant professor share consistently exceeds their shares at other ranks, as has been well-documented elsewhere (e.g., see Ceci et al. 2014; Ginther and Kahn, 2004). Interestingly, however, the gender gap across ranks is closing over time—that is, the share of full professors who are women is increasing faster (13 percentage points from 2002-2022) than the shares of assistants and associates (7 and 10 percentage points, respectively).

Figure 1 makes clear that faculty diversity was increasing well before the 2016 protests. Have diversity trends changed since 2016? To explore this question, we estimate interrupted time series (ITS) models to test whether the trends in faculty diversity after 2016 differ from what would be predicted based on the pre-protest trends. Our ITS models take the following form:

In Eq. (1) \({Y}_{{it}}\) is a faculty racial-ethnic or gender share at university i in year t, Tt is a linear time variable that increments annually, Ix is an indicator variable equal to one if the year is x and zero otherwise, and εit is an idiosyncratic error. The parameters of interest are θ1−θ6. These parameters identify deviations from the pre-protest linear trend identified by β1.Footnote 8

As noted above, universities’ faculty diversity efforts have emphasized recruitment, which will affect the flow of faculty. Changes to the stock of faculty should be expected to take place over a longer time horizon. Given that the flow into professor positions is predominantly at the assistant professor level (i.e., most newly hired faculty enter as assistant professors), we focus on results from Eq. (1) for assistant professors to gauge the potential impact of the protests. We show the results in Table 2.

The visual patterns in Fig. 1 are borne out in the results in Table 2. However, only some post-protest deviations are statistically significant. Most notably, the share of Black assistant professors is weakly increasing relative to the linear prediction after the protests and the deviations from trend in 2021 and 2022—when the trend for Black assistant professors shows the largest increases visually in Fig. 1—are statistically significant. The deviation from trend for White assistant professors also becomes more pronounced over time, though only the coefficient on the year-2022 indicator is statistically significant. The post-protest deviations for Asian assistant professors are consistently negative and reflect the flattening of their trend in the latter portion of our data panel. However, the flattening of the trend clearly predates the protests in Fig. 1, suggesting it is driven by faculty diversity dynamics outside of the protests. For Hispanic and Female assistant professors, the deviations from their pre-protest trends after 2016 are not statistically significant.

In the appendix, we also estimate ITS regressions for the other faculty ranks (Appendix Tables A2 and A3). Given the emphasis on hiring-based initiatives in universities’ post-protest responses, we would expect their influence at higher ranks to be modest over the time horizon we study, but we find some statistically significant deviations from the linear trends. This is a useful reminder that post-protest changes to faculty diversity cannot be attributed solely to university responses to the protests and embody university diversity dynamics more broadly. An instructive example is the downward trend for White full professors, which we show in Appendix Table A3 accelerates significantly after the protests despite no evidence of explicit university policies that would influence this trend. This could occur for many reasons. One possibility is that the gap in the White share between (relatively) young, rising full professors and older, retiring full professors is growing over time due to long-run (and pre-protest) diversity trends. In summary, our ITS regressions uncover some changes to the trends in faculty diversity since 2016 that are consistent with the influence of the diversity initiatives implemented by universities, but also serve as a reminder that other factors likely play an important role as well.

Next, in Fig. 2, we compare diversity trends in STEM and non-STEM fields since 2016. We report four different calculations of the change in the faculty share for each racial-ethnic and gender group, by rank: (1) in all fields in IPEDS using the L&K university sample from 2016-2022 (2023 IPEDS data are not yet available), (2) in all fields in the L&K dataset from 2016–2023, (3) in STEM fields in the L&K dataset, and (4) in non-STEM fields in the L&K dataset. The first two calculations are provided to compare the general trends in IPEDS and the L&K dataset since 2016.Footnote 9 The third and fourth calculations are of primary interest and show field heterogeneity between STEM and non-STEM fields.

Notes. IPEDS Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, L&K Li and Koedel Data. Changes in faculty percentages are from 2016 to 2022 in IPEDS and 2016 to 2023 in the L&K dataset (IPEDS data from 2023 are not yet available). IPEDS data are restricted to the L&K university sample. STEM fields are defined as biology, chemistry and economics; non-STEM fields are defined as English, educational leadership and policy, and sociology. A is for all faculty, B is for assistant professors, C is for associate professors, and D is for full professors. The vertical scale is in percentage points and differs as necessary to show changes for the different groups at appropriate scale. * indicates the difference between STEM and non-STEM fields is statistically significant at the 10 percent level.

We start by looking at field heterogeneity across all faculty ranks in Panel A. There is visual heterogeneity for two groups. Recent growth in the female faculty share is higher in STEM fields than in non-STEM fields, by about 1.3 percentage points (4.5 versus 3.2 percentage points), and recent growth in the Black faculty share is higher in non-STEM fields, by about 0.8 percentage points (0.4 versus 1.2 percentage points). However, none of the differences among all faculty in panel A are statistically significant.

We find the largest differences in faculty diversity across fields among assistant professors, shown in panel B of the figure. Note we expand the scale of the vertical axis for assistant professors because their changes are much larger than for faculty at other ranks. The field differences for Black and Hispanic assistant professors indicate more rapid growth in non-STEM fields, which will further widen existing racial-ethnic gaps across STEM and non-STEM fields. In contrast, recent growth in the female assistant professor share is entirely in STEM fields, and in fact there was a modest decline in the share of female assistant professors in non-STEM fields from 2016 to 2023. Thus, recent diversity trends are helping to narrow the gender imbalance between STEM and non-STEM fields.

Panels C and D show rank-specific changes for associate and full professors, respectively. These changes are modest and none are statistically significant (we also bring the scale of the vertical axis back down from panel B). In summary, Fig. 2 illustrates substantial and statistically significant field differences in changes to faculty diversity in STEM and non-STEM fields between 2016 and 2023, concentrated among assistant professors.

Discussion

We document heterogenous trends in faculty diversity in STEM and non-STEM fields since the 2015-16 academic year. Racial-ethnic diversity gaps between STEM and non-STEM fields are widening, especially for Black faculty, while the gender diversity gap is narrowing. The trend heterogeneity is concentrated among assistant professors, which suggests an influence of universities’ post-protest, hiring-centric diversity efforts. However, other faculty diversity dynamics also likely play some role.

We note several limitations of our analysis. One is that our sample is too small to credibly track diversity trends by field for specific race-gender groups, such as Black females or White males. Future research using larger samples may be able to shed light on these more granular trends. It would also be of interest to compare faculty diversity to student diversity by field, though research suggests the latter is likely directly affected by the former, making inference difficult. Matias, Lewis, and Hope (2022) examine a related concept by comparing faculty diversity to population diversity in the U.S., concluding that absent substantial changes in trajectories, faculty diversity will continue to lag population diversity. Finally, the differential diversity trends we document by field are concentrated primarily at the assistant professor level, where most new faculty enter. Long-term follow up research can shed light on how the stock of faculty diversity across fields is changing over time.

In terms of the implications of our findings, a large body of evidence suggests students are more likely to continue in fields in which they are exposed to more demographically matched instructors. For instance, Fairlie et al. (2014) find racial minority students are more likely to enroll in subsequent courses and major in an area if they have a racial minority instructor, and Price (2010) shows having a Black STEM instructor increases the likelihood that Black students continue in a STEM major. Likewise, Bettinger and Long (2005) show female instructors cause female students to take more courses in the same field, and major in the same field, and Carrell et al. (2010) replicate this finding for female students with high SAT math scores in STEM fields.Footnote 10

A concern raised by our findings is that recent trends in racial-ethnic diversity among faculty may reinforce the current underrepresentation of Black and Hispanic students in STEM fields (Bleemer and Mehta, 2023; Carnevale et al. 2015). This, in turn, will have implications for future efforts to diversify the faculty. Conversely, we find no such cause for concern with regard to gender diversity. This is because while women remain underrepresented among faculty in STEM fields, recent trends in gender diversity are narrowing the cross-field faculty gender gap. A possible explanation for this result is the long-standing emphasis on STEM fields in efforts to promote gender diversity among faculty (e.g., through programs such as NSF ADVANCE).

A policy recommendation that follows from our findings is that universities should pay attention to the balance of faculty diversity across different fields of study. This is not a trivial recommendation given that the supply of PhDs—the key qualification necessary for a faculty position—is out of balance along the same dimensions as the faculty (Li and Koedel, 2017; Parsons, 2023). However, ignoring field imbalance in efforts to diversify the faculty may lead to unintended negative consequences for precisely the students who are meant to benefit most from such efforts, while at the same time reinforcing existing imbalances in the availability of qualified candidates for faculty positions in the future.

Methods

General Data Information

An advantage of both the IPEDS and L&K datasets is that they are not survey-based; rather, they are effectively “universe samples” of faculty. University reporting to IPEDS is required by the federal government for all institutions that participate in federal student financial aid programs (although as noted above, prior to 2017 demographic data reporting was optional in odd-numbered years). The L&K dataset covers only selected universities and departments, but among these, includes all faculty listed on departmental websites. By not relying on surveys in either dataset, we mitigate concerns about misleading inference due to endogenous survey participation rates. For instance, Bollinger et al. (2019) show that survey response rates can differ by race and correlate differentially with earnings for men and women. This can be problematic for studying faculty diversity and diversity across fields with disparate pay. Even data from the National Study of Postsecondary Faculty—a survey administered by the (well-resourced) National Center for Education Statistics from the late 1980s to early 2000s—had a response rate of just 76% by the final wave in 2003-04. Smaller surveys often have even lower response rates—e.g., in Morgan et al.’s (2022) study of the socioeconomic roots of faculty, they report that just 10–15 percent of their sample frame provided key information on their survey.

Construction of the L&K Dataset

We refer interested readers to Li and Koedel’s original 2017 article for a detailed discussion of their original data collection during the 2015-16 academic year. Here we briefly highlight key aspects of their data collection and provide information about our follow-up collection in 2022-23.

During the 2015-16 academic year, Li and Koedel (2017) collected data on individual faculty from six academic departments—biology, chemistry, economics, English, educational leadership and policy, and sociology—across 40 selective public universities. The universities in the original dataset correspond roughly to the highest-ranked universities by U.S. News & World Report in 2016, with several adjustments as described in their original article (Li and Koedel, 2017). Three of the six focal departments were sampled at random at each university, generating a dataset of faculty in 120 unique academic departments. For selected departments, information was collected for all tenured and tenure-track faculty. Appendix Table A1 lists the universities and departments included in dataset.

We conducted a follow-up data collection of all faculty in the same departments during the 2022-23 academic year to construct the department-level panel dataset used for our analysis. In the follow-up, we collected information for each tenured and tenure-track faculty member on race-ethnicity, sex, and academic rank. Many of the faculty members in these departments in 2022-23 were also present in 2015-16, but there were many new additions and exits. We also identified a small number of likely errors in the original Li and Koedel dataset, which we corrected during the process of building our data panel.

In Li and Koedel’s original dataset, faculty race-ethnicity and sex designations were made by visual inspection of faculty pictures, origins of names, and in some cases, biographical details (e.g., the country of the undergraduate institution listed on the CV). We used the same approach in our follow-up data collection. In both waves of the dataset, interrater reliability of the race-ethnicity and sex designations is high.Footnote 11 Interrater agreement does not ensure measurement accuracy (e.g., both raters could be in agreement but wrong); however, a high interrater reliability rules out at least some types of measurement error. Conceptually, there are strengths and weaknesses of the external approach used to code race-ethnicity and sex in the L&K dataset. We do not relitigate these strengths and weaknesses here, but they are discussed in depth in the original Li and Koedel article (Li and Koedel, 2017), and in follow-up commentaries by Laughter (2018) and Li and Koedel (2018).

Sensitivity Analysis

We conduct two tests to examine the sensitivity of our findings to data adjustments. First, we examine whether the long-term diversity trends in Fig. 1 are similar if we use all public R1 universities in IPEDS rather than the 40 universities included in the L&K dataset. Appendix Figure A1 shows that the diversity trends are almost identical to the trends in Fig. 1 if we use the full sample of public R1 universities. Second, we test whether the trends in STEM and non-STEM fields look similar if we define these fields more rigidly. Specifically, we define STEM fields as biology and chemistry, and non-STEM fields as English and sociology, and omit faculty in economics and educational leadership and policy from the dataset. Appendix Figure A2 shows our findings in STEM and non-STEM fields are unchanged substantively when we use these alternative definitions, though the difference for Black assistant professors is no longer statistically significant.

Data availability

The datasets used in this study are publicly available in the Harvard Dataverse: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/XK7OEI.

Notes

These responsibilities are taken from the posted responsibilities of diversity advisors at the University of Washington in St. Louis and the University of San Diego, California. The information was retrieved on 06.06.2024 at the following links: https://diversity.med.wustl.edu/resources/diversity-advisors/ and https://facultydiversity.ucsd.edu/recruitment/#Faculty-Equity-Advisors.

Description retrieved on 06.06.2024 at the following link: https://advance.cc.lehigh.edu/advancing-future-faculty-diversity-postdoctoral-program.

The pipeline issue is more severe for Blacks and Hispanics than for women, who are underrepresented, but to a lesser degree, among PhDs in STEM fields (also see Ceci et al., 2014).

Li and Koedel (2017) made a small number of substitutions of universities due to data limitations, leading to small deviations from the U.S. News top 40, as described in their article.

It is worth noting that IPEDS has been unclear about sex versus gender in its data collection instruments and reporting to date, raising questions about whether the data reflect sex or gender (IPEDS Technical Review Panel, 2016). IPEDS is revising its gender data collection protocols beginning with the 2023-24 collection.

Trends prior to 2017 use even-numbered years only because demographic data reporting was optional in odd-numbered years. Race-ethnicity data reporting was also optional in 2010, so it is omitted.

The percentages of Asian, Black, Hispanic, and White faculty do not sum to 100 in the figure because IPEDS includes additional racial-ethnic categories (per Table 1).

The parameter β1 identifies the pre-protest trend because we include indicator variables for each post-protest year. That is, the year indicators for years 2017-2022 are included as year fixed effects and there is no within-year variation in Tt. This restricts the identifying variation used to identify β1 to pre-2017 years only.

The overall trends are similar in both datasets in panel A. When we split faculty by rank the trends are directionally aligned but differ in magnitude in some instances, which we attribute primarily to sampling variance. The sampling variance explanation is consistent with the pattern of discrepancies in the figure. Namely, the largest discrepancies are at the assistant and associate levels, where the L&K sample size is smallest (Table 1). At the full professor level, the discrepancies shrink considerably.

As noted above, these studies can be viewed as a subset of studies in a much larger literature on the effects of student-teacher demographic matches at the K-12 and postsecondary levels.

In wave-1 during the 2015-16 academic year, Li and Koedel (2017) report reliabilities of 95.5 and 99.75 percent for faculty race-ethnicity and sex, respectively. In wave-2 during the 2022-23 academic year, our interrater reliabilities were 96 and 100 percent, respectively.

References

Allen J (2016) U-M unveils five-year strategic plan for diversity, equity and inclusion. In: The University Record - University of Michigan

Bettinger EP, Long BT (2005) Do faculty serve as role models? The impact of instructor gender on female students. Am. Economic Rev. 95:152–157

Bleemer Z, Mehta A (2023) College major restrictions and student stratification. Unpublished manuscript

Bollinger CR, Hirsh BT, Hokayem CM, Ziliak JP (2019) Trouble in the tails? Earnings non-response and response bias across the distribution. J. Political Econ. 127(5):2143–2185

Bradley SW, Garven JR, Law WW, West JE (2022) The impact of chief diversity officers on diverse faculty hiring. South. Economic J. 89:3–36

Carnevale AP, Cheah B, Hanson AR (2015) The Economic Value of College Majors. Policy Report. Center on Education and the Workforce, Washigton DC

Carrell SE, Page ME, West JE (2010) Sex and science: How professor gender perpetuates the gender gap. Q. J. Econ. 125:1101–1144

Ceci SJ, Ginther DK, Kahn S, Williams WM (2014) Women in academic science: A changing landscape. Psychological Sci. Public Interest 15(3):75–141

Dee TS (2004) Teachers, race, and student achievement in a randomized experiment. Rev. Econ. Stat. 86:195–210

Deo ME, Woodruff M, Vue R (2010) Paint by number-How the race and gender of law school faculty affect the first-year curriculum. Chicana/o-Lat./o L. Rev. 29:1

Egalite AJ, Kisida B, Winters MA (2015) Representation in the classroom: The effect of own-race teachers on student achievement. Econ. Educ. Rev. 45:44–52

Fairlie RW, Hoffmann F, Oreopoulos P (2014) A community college instructor like me: Race and ethnicity interactions in the classroom. Am. Economic Rev. 104:2567–2591

Gershenson S, Hart CMD, Hyman J, Lindsay CA, Papageorge NW (2022) The long-run impacts of same-race teachers. Am. Economic J.: Economic Policy 14(4):300–342

Ginther DK, Schaffer WT, Schnell J, Masimore B, Liu G, Haak LL, Kington R (2010). Diversity in academic biomedicine: An evaluation of education and career outcomes with implications for policy. Unpublished working paper

Ginther DK, Kahn S (2004) Women in economics: Moving up or falling off the academic career ladder? J. Economic Perspect. 18(3):193–214

Gottfried M, Kirksey JJ, Fletcher TL (2022) Do high school students with a same-race teacher attend class more often. Educ. Evaluation Policy Anal. 44(1):149–169

Griffin KA (2019) Institutional barriers, strategies, and benefits to increasing the representation of women and men of color in the professoriate: Looking beyond the pipeline, in Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research Vol 35 (ed. L.W. Perna). Berlin: Springer

Hartocollis A, Bidgood J (2015) Racial Discriminiation Protests Ignite at Colleges Across the U.S. New York Times (11.11.2015) (retreived at the following link on 12.12.2023: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/12/us/racial-discrimination-protests-ignite-at-colleges-across-the-us.html)

Hoffman F, Oreopoulos P (2009) A professor like me: The influence of professor gender on college achievement. J. Hum. Resour. 44(2):479–494

Hurtado S (2001) Linking diversity and educational purpose: How diversity affects the classroom environment and student development. In: Orfield G, Kurlaender Michal (Eds.) Diversity challenged: Evidence on the impact of affirmative action. Harvard Education, Cambridge, MA:, p 187–203

IPEDS Technical Review Panel (2016) Report and Suggestions from IPEDS Technical Review Panel #51: Gender. Unpublished report, RTI International (retreived on 12.17.2023 at https://ipedstrp.rti.org/)

Laughter J (2018) Race in Educational Researcher: A technical comment on Li and Koedel (2017). Educ. Researcher 47(4):259–261

Li D, Koedel C (2017) Representation and salary gaps by race-ethnicity and gender at selective public universities. Educ. researcher 46:343–354

Li D, Koedel C (2018) A Technical Comment on Li and Koedel (2017): Author Response. Educ. Researcher 47(4):262–263

Lindsay CA, Hart CMD (2017) Exposure to same-race teachers and student disciplinary outcomes for Black students in North Carolina. Educ. Evaluation Policy Anal. 39(3):485–510

Matias JN, Lewis NA, Hope EC (2022) US universities are not succeeding in diversifying faculty. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6:1606–1608

Morgan AC, LaBerge N, Larremore DB, Galesic M, Brand JE, Clauset A (2022) Socioeconomic roots of academic faculty. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6:1625–1633

O’Meara K, Culpepper D, Templeton LL (2020) Nudging toward diversity: Applying behavioral design to faculty hiring. Rev. Educ. Res. 90(3):311–348

Parsons S (2023) Understanding Diversity within the Higher Education Faculty Pipeline. Policy Brief. Urban Institute, Washington DC

Paul JD, Maranto R (2021) Other than merit: The prevalence of diversity, equity, and inclusion statements in university hiring. Policy report. American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, Washington, DC

Price J (2010) The effect of instructor race and gender on student persistence in STEM fields. Econ. Educ. Rev. 29:901–910

Salovey P, Polak B (2015) Yale Launches $50 million Faculty Diversity Initiative. Office of the Provost, Yale University, New Haven, CT, https://news.yale.edu/2015/11/03/yale-launches-five-year-50-million-initiative-increase-faculty-diversity (retreived at: 08.02.2023)

Webber DA (2016) Are college costs worth it? How ability, major, and debt affect the returns to schooling. Econ. Educ. Rev. 53:296–310

Whittaker JA, Montgomery BL, Martinez Acosta VG (2015) Retention of underrepresented minority faculty: Strategic initiatives for institutional value proposition based on perspectives from a range of academic institutions. J. Undergrad. Neurosci. Educ. 13(3):A136–A145

Zambrana RE, Ray R, Espino MM, Castro C, Douthirt Cohen B, Eliason J (2015) “Don’t leave us behind”: The importance of mentoring for underrepresented minority faculty. Am. Educ. Res. J. 52(1):40–72

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SPB and CK contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baker, S.P., Koedel, C. Diversity trends among faculty in STEM and non-STEM fields at selective public universities in the U.S. from 2016 to 2023. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1149 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03687-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03687-x

This article is cited by

-

Race and Measurement of Publication Productivity Using Sociology as a Case

Innovative Higher Education (2025)