Abstract

This study analyzes the effect of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance on banking stability in the digital era for a selected group of European banking institutions. Unlike many research, this paper incorporates the digital environment in which the European banking system operates into its investigation to capture the relationship between ESG scores, digitization, and bank stability from 2005 to 2022. This study uses a regime-switching model to investigate the non-linear hypothesis of the relationship, an aspect that has received insufficient attention in previous research. The empirical results confirm the non-linearity between ESG performance and banking stability in the digital era, identifying three ESG performance regimes. Moreover, higher ESG scores are associated with a lower risk of bank failure, aligning with stakeholder theory. Finally, European banks with weak ESG scores fail to avoid the fragility caused by investments in technological infrastructure. Overall, our results suggest that critics and proponents of banks’ commitment to social responsibility are, to some extent, right. Indeed, low or moderate ESG performance (Regimes 1 and 2) aligns with the classical perspective, while high ESG engagement (Regime 3) is consistent with the stakeholder view. Consequently, European banks need to adopt a digital strategy based on improving sustainability to leverage the positive impact of digitization and ESG performance on bank stability. On the policymakers’ side, they need to strengthen the legal infrastructure to support digitization and engagement in social responsibility activities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the current context of a socially conscious economy, sustainability trends have attracted the interest of regulators and researchers. Sustainability is reflected in corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities that integrate environmental, social, and governance (ESG) aspects into decision-making processes (Sassen et al., 2016). These CSR activities can be evaluated based on ESG performance scores (Chollet and Sandwidi, 2018; Nofsinger et al., 2019), which explicitly integrate governance aspects (Gillan et al., 2021).

In this sense, a rich literature has developed on the effect of ESG scores on corporate performance (Lee and Faff, 2009; Oikonomou et al., 2012; Albertini, 2013; Lisin et al., 2022) and banks (Paltrinieri et al., 2020; Aracil et al., 2021; SN Azmi et al., 2023). This impact has generally been considered positive concerning the banking sector’s profitability (Buallay, 2019). The interest in the banking sector stems from its importance in sustainable development due to its intermediation role, which allows financial resources to be mobilized to achieve sustainable goals (Yip and Bocken, 2018). In addition, several external shocks have affected the banking sector, most notably the 2008 financial crisis (Forcadell and Aracil, 2017), digitalization (Del Gaudio et al., 2021; Chinoda and Kapingura, 2023), and facilitating the sustainable digital transformation of banking institutions (Forcadell et al., 2020).

The attention paid to the impact of ESG commitments on the banking sector, especially after the 2008 financial crisis, has been the origin of several studies on the relationship between ESG performance and banking risk or stability (Srivastav and Hagendorff, 2016; Chollet and Sandwidi, 2018; Chiaramonte et al., 2022; Neitzert and Petras, 2022; Aevoae et al., 2023; Galletta et al., 2023). The literature on the nexus between ESG scores and bank stability mainly reveals a theoretical debate between the shareholder view of the firm (Friedman, 1970), which sees these ESG practices as a cost and, therefore, an overinvestment, and the stakeholder view (Freeman, 1984), which sees them more as an ethical obligation to mitigate bank risk. Both views suggest opposite effects. Despite the existence of recent literature, major theoretical gaps remain in examining the nexus between ESG scores and the probability of bank failure (DZ Huang, 2022), and bank stability. Indeed, there is still no consensus on the nature, intensity, and direction of the relationship, given the complexity of the institutional context in which ESG activities take place. This complexity is due to organizational constraints and the diversity of individual decision-makers (DZX Huang, 2021). Furthermore, the nexus between ESG and banking stability remains unclear despite recent empirical literature. It requires further exploration, including consideration of non-linearity. To our knowledge, the study by Lupu et al. (2022) is the only one to test this aspect empirically. Finally, previous empirical studies on the impact of ESG commitments on bank stability have not considered the evolution of banking activities in an increasingly digitized environment, except for the Salah Mahdi et al. (2023) study.

Against this backdrop, this paper addresses the following central question: How do changes in ESG scores affect bank stability in the digital era? In addition to this main question, there are other equally important ones. These include the following: What is the link between the impact of digitization on bank stability and ESG activities? Does the stability of banks in the digital era depend on the level of their ESG scores?

In doing so, this paper highlights its contribution to empirical research. First, this article aims to test the hypothesis that the relationship is characterized by non-linearity and contingent upon the level of ESG scores, complementing the recent literature that has shown the positive impact of high ESG scores on bank stability (Chiaramonte et al., 2022), reducing systemic distress (Aevoae et al., 2023), and enabling a better predictive ability of bank distress (Citterio and King, 2023). Second, to account for the impact of the digital age, this study also examines the impact of ICT diffusion and endowment on bank stability, controlling for ESG scores. To our knowledge, this is the first study to link the impact of digitization on bank stability to ESG activities. Third, this article highlights its contribution to the empirical literature from a methodological point of view, opting for the Panel Smooth Transition AutoRegressive (hereafter, PSTAR) modeling approaches to capture the nuances and regime change of the nexus between ESG scores and banking stability in the digital era for a group of European banks operating in 15 European countries between 2005 and 2022. This relatively long period encompasses both the 2008 global financial crisis and the European 2010–2012 sovereign debt crisis, providing insight into the nexus between ESG and stability in the digital age, particularly in the context of crises.

The European context is important for several reasons. First, the European banking sector is a major component of the global financial system (Batten et al., 2022), so its stability is important not only for the region but also for all global economies, given the potential contagion effects outside Europe (Gabrieli and Salakhova, 2019; Teply and Klinger, 2019). Second, in the European banking context, engagement in ESG activities is a priority, especially for the European Banking Authority, which requires ESG disclosure in a regulatory framework aimed at improving the sustainability of the European financial system (Bruno and Lagasio, 2021). In addition, there are several countries in the region whose banks have been pioneers in sustainable development. Finally, the focus on the EU is important because it allows us to identify the possible impact of digitization and ESG ratings on bank stability in the presence of a mature banking sector.

The results highlight three key findings. First, the empirical results confirm the non-linear nexus between ESG performance and banking stability in the advent of the digital age. Second, higher ESG scores are associated with a lower risk of bank failure. Finally, European banks with low ESG scores fail to avoid the fragility caused by investments in technological infrastructure.

The subsequent section is structured in the following sequence: in section “Theoretical background and hypothesis”, the theoretical and empirical literature, on the influence of ESG scores and digitization on bank stability, are checked. The PSTAR modeling approach and associated data are presented in the section “Econometric modeling and variable processing”. Descriptive analysis of variables and the model employed are the subjects of the section “Empirical analysis”. The primary estimation results are discussed in section “Discussion”. Section “Conclusion and policy recommendations” concludes with the policy implications.

Theoretical background and hypothesis

This section aims to distinguish between two relationships. Firstly, it reports on the theoretical debate regarding the relationship between digitization and bank stability. This debate is based on two opposing hypotheses: ‘innovation-stability’ and ‘innovation-fragility’. Secondly, it aims to deepen the analysis of the relationship between ESG performance and bank stability, referring to existing theories and empirical investigations.

Digitization and bank stability

The digitization of the financial sector, thanks to information and communication technologies (ICT), is one of the defining phenomena of today’s financial world (Kasri et al., 2022). Indeed, ICTs are profoundly reshaping the economic landscape, eliminating information asymmetries thanks to big data (Kosmidou et al., 2017; Guérineau and Léon, 2019), and enabling the rapid spread of financial innovations. The development of digital capabilities is accompanied by a rise in customer expectations and the entry of fintech companies into the banking ecosystem. As a result, competition is intensifying, and the dynamics of financial services, in the broadest sense, within the banking ecosystem are becoming completely different (Zavolokina et al., 2017). Consequently, in the digital age, the competitiveness and viability of banks are becoming increasingly complex, stimulating scientific research into the impacts of digitization on bank stability.

The beneficial influence of ICT on financial institutions’ profitability and operational effectiveness (DeYoung et al., 2007; Ciciretti et al., 2009; Scott et al., 2017), in line with creative destruction Schumpeter’s theory of (Schumpeter, 1934), which considers technological progress and innovation as the primary drivers of business performance, has not prevented a theoretical discussion on the impact of digitization on banking stability. This debate is based on two opposing hypotheses “innovation stability” and “innovation fragility.”

According to the first hypothesis, the technological innovation that characterizes the digital age translates into improved bank stability. Several empirical studies supported this view. Del Gaudio et al. (2021), who study the impact of ICT on bank stability in EU countries, find a positive effect of ICT diffusion, endowment, and infrastructure. They find empirical evidence of a positive relationship between the reduction of bank failure risk and ICT diffusion and endowment. They show that the reduced fragility of European banks resulted from improved performance and information dissemination. Kasri et al. (2022), in their study of the banking sector in Indonesia, using the ARDL model, asserted the existence of a positive short-term relationship between digital payments and bank stability with unidirectional causality. Similarly, Hasan et al. (2012), in their study of banks in 27 European countries, found a positive relationship between efficient electronic payment services and bank performance and stability.

According to the second hypothesis, the technological innovation that characterizes the digital era makes the banking sector more fragile. Indeed, empirical studies have shown that the ICT behind financial innovation can increase systemic risks to financial stability and bank soundness (Uddin et al., 2020). Numerous empirical studies have highlighted the distortions introduced by financial innovation and its contribution to significant risk-taking, which was reported as a primary contributing factor to the 2007–2008 global financial crisis (Rainey and Ibikunle, 2012). Moreover, according to Beck et al. (2016), financial innovation can also lead to fragility in banks because of greater profitability volatility, especially in nations with more stringent regulatory environments and larger securities markets.

It should be noted that some studies have found mixed results, as in the case of Syed et al. (2022), which included one developed and one developing country. Using ARDL estimation, this study examined the influence of digital financial services on banking stability and efficiency in India and the US. Their results show that the effects vary by country’s level of development. Specifically, the “innovation-stability” hypothesis holds only in the case of the US in the short and long terms. However, in the short-term, the Indian banking sector supports the “innovation-fragility” hypothesis.

A synthesis of the empirical literature reveals two significant gaps. First, the extant studies tend to concentrate on the influence of financial innovation or digital financial inclusion resulting from digitization on stability. As far as we are aware, only the study by Del Gaudio et al. (2021) has analyzed the impact of digitization on bank stability through ICT diffusion, endowment, and infrastructure. Second, all studies assumed the linearity of the relationship without considering possible non-linearity. Following in the footsteps of Del Gaudio et al. (2021), this research attempts to present new findings while exploring the non-linear relationship between digitization and bank stability.

Based on the above discussions, we put forth the following hypotheses for consideration:

H1. The diffusion of ICT has a positive impact on bank stability.

H2. The technological endowment of the banking sector positively impacts bank stability.

ESG performance and bank stability

The relationship between ESG performance and bank stability is a topic of theoretical debate. The classical view (Friedman, 1970) supports a negative relationship, while the stakeholder view (Freeman, 1984) confirms a positive impact of ESG scores on bank stability.

In line with the classical view, the sole responsibility of banks is to maximize profits. From this perspective, engaging in ESG activities diverts scarce bank resources away from maximizing shareholder wealth and increasing banking value (Barnea and Rubin, 2010). In this line of thinking, ESG investments, according to the managerial opportunism argument, are a waste of resources and negatively affect the bank’s performance (Barnea and Rubin, 2010). According to Barnea and Rubin (2010), these investments can be considered agency costs, in the sense that managers, concerned with their reputation, make them to the detriment of shareholders’ interests. From this perspective, investors perceived these firms as riskier. This view of overinvestment thus predicts a positive (negative) relationship between bank risk (stability) and the ESG score.

In line with the overinvestment perspective, we can formulate the hypothesis as follows:

H3. The relationship between ESG scores and bank stability is negative.

Conversely, the stakeholder theory suggests that involvement in ESG practices leads to investments in ESG activities, which generate moral capital that can act as an insurance mechanism to mitigate both operational (Galletta et al., 2023) and ESG risks. Thus, the more a bank engages in ESG activities, the more it demonstrates greater transparency, enabling it to garner greater support from stakeholders (W. Azmi et al., 2021).

Such signals improve the bank’s reputation (Forcadell and Aracil, 2017) and attract more customers (McWilliams and Siegel, 2011). The benefits of reputational capital allow banks to finance their operations from stable sources, thereby reducing risk and consequently improving bank stability (Gangi et al., 2019). From this perspective, banks need to become more involved in ESG practices to enhance the image of the banking sector, particularly in the wake of the 2007–2008 global financial crisis, which led to customer distrust. Moreover, it is thanks to this reputational effect that the cost of capital and cash flows allow ESG activities to have a favorable influence on bank stability (W. Azmi et al., 2021).

The empirical literature has shown that most findings are consistent with the vision of stakeholder theory. Indeed, Aevoae et al. (2023) in their study of the influence of changes in ESG scores on the systemic risk found conclusions consistent with stakeholder theory. They documented the positive impact of ESG scores on reducing banks’ contribution to systemic risk. In other words, the higher the ESG score, the lower the banks’ contribution to system-wide difficulties. These findings are consistent with those of Scholtens and van’t Klooster (2019). Aevoae et al. (2023) analysis of the different sub-pillars of ESG showed that only the governance pillar has a significant positive impact. Their results are consistent with previous studies (Kiesel and Lücke, 2019; Chiaramonte et al., 2022). It should be noted, however, that the literature finds a significant positive impact of the social pillar on reducing banks’ risk (Chiaramonte et al., 2022). Similarly, the empirical literature shows that the more banks address environmental issues, the lower the risk of bank failure (Gangi et al., 2019). This effect is even stronger in times of crisis (Chiaramonte et al., 2022). In the same vein, Neitzert and Petras (2022), who analyzed the impact of ESG practices on banking risk and explored its factors of influence on a sample of banks worldwide between 2002 and 2018, showed that a high ESG score for banks is likely to reduce the risk of bank failure. However, this study notes that decomposing this overall effect by considering sub-pillars separately shows the importance of environmental engagement in mitigating and managing banks’ risks, which is consistent with the findings of Gangi et al. (2019) and Chiaramonte et al. (2022).

This study by Chiaramonte et al. (2022), which addresses the European banking sector, could be considered a useful reference for our study. Considering a group of banks in 21 European nations from 2005 to 2017, Chiaramonte et al. (2022) find that the impact of the ESG score on banking stability is positive. They find a stabilizing effect and a reduction in the fragility of banks with high ESG scores. These findings are consistent with those of Di Tommaso and Thornton (2020), who support the negative relationship between ESG engagement and risk-taking.

Di Tommaso and Thornton (2020) examine this relationship between ESG scores and the risk-taking of 81 European banks active in 19 nations after the global financial crisis. They show that the effect of high ESG scores on risk-taking, while negative, remains relatively modest for both low-risk and high-risk banks. Their results remain consistent with stakeholder theory regarding the positive impact of ESG practices on banking stability (risk reduction). Nevertheless, when examining the effect of ESG scores on bank value, they find a negative relationship, with high ESG scores reducing bank value. Such a conclusion is consistent with the view of “overinvestment” associated with ESG activities. They thus show that, in terms of bank value, the indirect positive effect of reduced risk-taking resulting from these ESG activities cannot compensate for their direct negative impact on bank value. The extant empirical review on the relationship between banks’ engagement in ESG activities and bank stability shows that most researchers find a positive effect of high ESG scores on risk reduction, consistent with stakeholders’ views. Considering the above discussion, we develop the hypothesis to be tested:

H4. The effect of European banks’ ESG scores on bank stability is positive.

The non-linear relationship between ESG performance and bank stability

Although a growing body of empirical evidence shows that ESG activities can reduce bank risk and improve bank stability, the issue still requires further investigation. Indeed, the evolving nature of ESG, as well as advances in digital technologies linked to big data and the potential of new empirical models, will allow new evidence to enrich the debate (Gillan et al., 2021). The empirical studies previously cited have all assumed a linear relationship between ESG scores and bank stability. However, as pointed out by Korinth and Lueg (2022), non-linear relationships should also be considered (Nollet et al., 2016; Barnett and Salomon, 2012). According to Barnett and Salomon (2012), engagement in social responsibility activities initially leads to a decrease in the firm’s financial performance, but subsequently, increased investment in social responsibility leads to an increase in financial performance. In this sense, their results confirm the hypothesis of a U-shaped relationship between social and financial performance. This shape of the relationship is also supported by the study of Nollet et al. (2016). However, Nollet et al. (2016) specify that low engagement in social responsibility activities is better for the firm’s financial performance compared to moderate engagement. Furthermore, high social performance is associated with the highest financial performance. They find that involvement in social responsibility activities only pays off once a certain threshold is reached.

Based on these studies of the relationship between ESG performance and firm financial performance, and by translating an improvement in financial performance into a reduction (improvement) in risk (stability), it is possible to predict a non-linear relationship between ESG performance and risk (or stability). The Korinth and Lueg (2022) study, which examines the relationship between ESG scores and risk on the German stock market for the 100 largest listed companies in the post-crisis period from 2012 to 2019, fits into this perspective. They show that the relationship between ESG scores and risk is inverse and non-linear. In the same vein, Lupu et al. (2022) studied the impact of ESG scores on the financial stability of 110 European banks between 2010 and 2022 using the cross-quantilogram approach. Their results show that the ESG performance of listed European banks influences their financial stability, which is consistent with the results of Tóth et al. (2021). Furthermore, Lupu et al. (2022) support the existence of a non-linear relationship between ESG performance and the financial stability of European banks. Their methodology analyzes the dependence on the lower and upper percentiles and demonstrates that ESG scores around their 60% percentile exhibit low levels of instability.

To fully comprehend the nexus between ESG scores and bank stability, it is imperative to give due consideration to the digital environment in which banks operate. All previous studies on this relationship have neglected the effect of ESG performance on the nexus between digitization and bank stability. Based on stakeholder theory, the more a bank engages in ESG activities, the more it demonstrates greater transparency and thus receives greater support from stakeholders (W. Azmi et al., 2021). This support is even more important with the digitalization of the banking sector, which protects stakeholders by reducing the risk of mismanagement (Mu et al., 2023). Salah Mahdi et al. (2023) argue that the digitization of the banking sector could improve the financial stability of banks by promoting ESG activities. On the other hand, the negative effects of digitization may be offset by the reputation generated by engaging in ESG activities (Forcadell et al., 2020), thus ensuring that bank stability is maintained. In the same vein, Stefanovic et al. (2021), studying the impact of digitization and sustainability on bank performance, argue that banks engaged in both digitization and ESG practices are profitable and, therefore, more stable even in times of crisis.

Based on the above discussion, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5. The relationship between ESG scores and bank stability is non-linear.

H6: The impact of digitization on bank stability depends on the level of banks’ ESG scores.

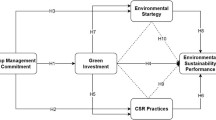

Figure 1 presents the conceptual model of the study.

The present study is similar to Lupu et al. (2022) and Salah Mahdi et al. (2023) in its focus but differs in its approach. Like Lupu et al. (2022), we investigate the relationship between ESG performance and European financial stability in the banking sector, but our study differs in two keyways. The study considers the digital environment in which European banks operate to capture the impact of ESG performance on the nexus between digitization and bank stability. The methodological approach is different, using the PSTAR model to estimate ESG score thresholds and their impact on bank stability. Finally, while the study by Salah Mahdi et al. (2023) focuses on Fintech, the present study examines the effect of ESG performance on the impact of ICT diffusion and endowment on bank stability to account for the digital era in which European banks operate.

Econometric modeling and variable processing

The paper introduces Panel Smooth Transition AutoRegressive (PSTAR) modeling approaches to capture the nuances and regime change of the relationship between bank stability and ESG scores in the digital era, following the presentation of the econometric model and the data. Diagnostic tests will be conducted to evaluate the assumptions and the model’s appropriateness in order to guarantee the results’ validity and reliability. These tests identify potential issues, including stationarity and dependency tests, and implement any required modifications.

Econometric model and variables description

The following general form of a linear model is assumed for the subject relationship:

where the subscripts “\({\rm{i}}\)” and “\({\rm{t}}\)” denote the bank and time, respectively. The bank-specific effect is captured by \({{\rm{\lambda }}}_{{\rm{i}}}\), the relevant time effect is taken into consideration by \({{\rm{\mu }}}_{{\rm{t}}}\), and the random error term is represented by \({{\rm{\varepsilon }}}_{{\rm{it}}}\). We provide a comprehensive summary of all variables in Table 1.

The current study covers the years 2005–2022. It included a panel of 15 European countries (France, Germany, Belgium, Denmark, Czechia, the Netherlands, Finland, Spain, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Norway, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, and Sweden). The selection of countries is not arbitrary. As the objective of this study is to examine the influence of ESG scores on bank stability in the digital era, it is based on the 2022 GII. What’s more, this diversified sample encompasses nations that exemplify the disparate rankings associated with this criterion, with every nation situated within the top 30. In addition, the selection of banks is a function of data availability.

Moreover, this diversified sample comprises nations that are illustrative of the diverse rankings to this criterion, all of which are situated within the top 30. Furthermore, the selection of banks is contingent upon the availability of pertinent data.

This study excludes countries with less than 18 years of bank observations and countries with insufficient observations to obtain reasonable variable estimates.

PSTAR model

In line with the research conducted by Helali and Kalai (2021), Bouattour et al. (2024), and Kalai et al. (2024), this study builds upon the work of Gonzalez et al. (2017), who developed regime change models that can be enhanced through the Panel Smooth Transition Regression (PSTR) modeling. This model’s contribution is analogous to the transitioning of time series from rapid transition approaches to gradual transition approaches.

A two-tier PSTR model is therefore satisfied by the process (\({y}_{{it}},t\in Z,i\in Z\)) but only if:

where \(G\left({q}_{{it}};\gamma {;c}\right)\) represents the transition function about the transition variable \({q}_{{it}}\), the threshold parameter \(c\), and a smoothing coefficient \(\gamma\). The matrix of \(k\) exogenous variables, \({X}_{{it}}=\left({X}_{it}^{1},\ldots ,{X}_{it}^{k}\right)\) does not contain any delayed explanatory variables, \(\beta =\left({\beta }_{1},\ldots ,{\beta }_{k}\right)\) and \({\varepsilon }_{{it}} \sim \aleph \left(0,{\sigma }^{2}\right)\). The index \(i=1,\ldots ,N\) denotes the individual dimension, while the index \(t=1,\ldots ,T\) denotes the temporal dimension.

Like the growth model of time series, the continuous transition function \(G\left({q}_{{it}};\gamma {;c}\right)\) modifies the indicator function of the Panel Threshold Regression (PTR) modeling. This function is differentiable on the interval \(\left(\mathrm{0,1}\right)\). The change permits the gradual transition process from one regime to another. Two distinct theories can be posited to explain the PSTR model. It can initially be viewed as an approach that is bound by two extreme schemes and contains an infinite number of schemes. In this study, we examine the coefficients that have the potential to fluctuate based on the units and the time period under consideration. The second area of focus is the commentary on the non-linear PSTAR technique, which entails a slow alternation between two homogenous and linear extreme regimes.

Ideally, a speed-to-speed transition function can be achieved by utilizing a variety of transition functions that are continuous and derivable over the range of \(\left(\mathrm{0,1}\right)\). Gonzalez et al. (2017) recommend the establishment of a logistic transition function of order \(m\) in this scenario:

where \(c\) is an m-dimensional vector of location parameters denoted by \(c={\left({c}_{1},\ldots ,{c}_{m}\right)}^{{\prime} }\). The slope parameter \(\gamma\) is the determinant of the regularity of the transitions. The restrictions \(\gamma \,> \,0\) and \({c}_{1}\le {c}_{2}\le \ldots \le {c}_{m}\) are enforced for the purpose of identification. In practical application, it is typically adequate to take into account m = 1 or m = 2, as these values accommodate frequently observed variations in the parameters.

It is crucial to assess linearity, or if the regime change effect is statistically significant, before estimating the PSTR model. A methodology for evaluating the null linearity hypothesis in comparison to a PSTR model was developed by Gonzalez et al. (2017). In the context of the PSTR model with unknown nuisance parameters under the null hypothesis \({H}_{0}:{\beta }_{2}=0\), the conventional testing approach is not standard. Gonzalez et al. (2017) proposed an alternative method to assess the linearity hypothesis \({H}_{0}:\gamma =0\). This involves substituting a first-order Taylor expansion around \(\gamma =0\) for \(G\left({q}_{{it}};\gamma {;c}\right)\) and resetting, leading to the auxiliary regression as presented below.

where \({\beta }_{1}^{{\prime} * }\) are inversely proportional to the slope parameter \(\gamma\); \({\varepsilon }_{it}^{* }={\varepsilon }_{{it}}+{R}_{1}{\beta }_{2}^{{\prime} * }{X}_{{it}}\), where \({R}_{1}\) is the remaining Taylor’s development. Consequently, the evaluation of \({H}_{0}:\gamma =0\) is equivalent to the evaluation of \({H}_{0}^{* }:{\beta }_{2}^{{\prime} * }=0\).

The following statistics are defined for each test: Wald, likelihood ratio and Fisher:

In the context of a linear panel model with individual effects, \({{SSR}}_{0}\) represents the residual sum of squares, while \({{SSR}}_{1}\) represents the residual sum of squares of the non-linear panel model with two regimes. If the null hypothesis is valid, the Wald Lagrange multiplier (\(L{M}_{w}\)) and the likelihood ratio (\({LR}\)) statistics will exhibit a chi-square distribution with k degrees of freedom, where k represents the number of explanatory variables. In other ways, the Fisher Lagrange multiplier (\(L{M}_{F}\)) statistic follows a two-degree Chi-square distribution.

Furthermore, if we assume the existence of two regimes (\(h=1\) and \(h=2\)) and consider the potential presence of an autoregressive issue, our fundamental linear model can be expressed in Panel Smooth Transition AutoRegression (PSTAR) specification as follows:

The coefficients of the lagged Banking Z_Score (\({{BZ\_Score}}_{{it}-j}\)) are \({\rho }_{1j}^{1}\) and \({\rho }_{1j}^{2}\) at each regime, \(h=1\) or \(h=2\).

Empirical analysis

Data analyze

Concerning Table 2, we describe the main variables in our model. We restrict ourselves to the variables BZ_Score, IUI, MCS, ATM, and ESG.

The BZ_Score variable has an overall mean of 29.959 with a standard deviation of 75.458, indicating considerable heterogeneity and dispersion in our distribution (CV = 2.519 > 1). The 1854 observations all lie between −322.080 and 1943.306. This distribution shows a rightward skewness (skewness > 0) and a marked leptokurtosis (kurtosis > 0). Overall, the distribution rejects the null hypothesis of normality (JB p-value < 5%) and shows a significant serial correlation (BB p-value < 5%).

The variable IUI exhibits an overall mean of 67.459 with a standard deviation of 24.625, indicating relatively low heterogeneity in our distribution (CV = 0.365 < 1). All values lie between 7.285 and 99.058. The sample distribution shows a slight left skewness (skewness < 0) and a marked leptokurtosis (kurtosis > 0). Overall, the distribution did not follow the null hypothesis of normality (JB p-value < 5%) and showed significant serial correlation (BB p-value < 5%).

The MCS variable displays an average value of 112.282, accompanied by a relatively low standard deviation of 24.565, indicating a distribution that is not highly heterogeneous (CV = 0.25 < 1). All the values of this variable are between 17,523 and 192,073. The sample distribution is weakly skewed to the left (skewness < 0) and leptokurtic (kurtosis >0). Overall, the distribution rejects the null hypothesis of normality (JB p-value < 5%) and exhibits strong serial correlation (BB p-value < 5%).

The ATM variable shows comparatively little heterogeneity in our distribution (CV = 0.4 < 1), with an average value of 80.451 and a standard deviation of 32.232. The range of all values is 19.386–194.63. There is a noticeable leptokurtosis (kurtosis > 0) and a modest rightward skewness (skewness > 0) in the sample distribution. Overall, there is a substantial serial correlation (BB p-value < 5%), and the distribution does not fit the null hypothesis of normality (JB p-value < 5%).

The mean value of the ESG variable is 49.028, and its standard deviation is a quite modest 18.967, suggesting that our distribution is not too diverse (CV = 0.387 < 1). This variable’s values are all between 0.000 and 95.533. The distribution of the sample is leptokurtic (kurtosis > 0) and somewhat skewed to the left (skewness < 0). Overall, the distribution shows a substantial serial correlation (BB p-value < 5%) and deviates from the assumption of normalcy (JB p-value < 5%).

At the bottom of Table 2, all the coefficients are well below 0.8, which is below the limit recommended by Kennedy (1985), above which serious problems of multicollinearity between the explanatory variables may arise. In addition, the independent variables were found to be weakly correlated. Consequently, the problem of multicollinearity does not arise in our situation. The correlation matrix provided above reveals that there are indeed correlations among the exogenous variables, potentially indicating the presence of multicollinearity. This issue could be addressed by exploring alternative models that incorporate less strongly related data. Notably, all variables demonstrate a positive and significant correlation with the BZ_Score variable, except for the ESG and CIR variables, which exhibit a negative and statistically significant correlation. Additionally, the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) test yields a low value of 1.24, confirming the absence of significant multicollinearity.

Unit root tests are of crucial importance in panel data analysis to check whether the data can be used in stationary time series models. If unit root behavior is identified, it may be necessary to consider methods such as differencing to make the data stationary before continuing with the analysis. In this context, we intend to present the results of the first- and second-generation unit root tests.

This phase will involve the interpretation of the unit root tests for two generations. Based on the notion that residuals are not influenced by individual differences, the first generation of tests was developed. This allows for the calculation of statistical distributions for the tests and the acquisition of asymptotic or semi-asymptotic normal distributions. From this perspective, any correlations between individuals are regarded as nuisance parameters. In the majority of cases, the assumption of independence is removed in the second generation of tests, which are more recent. Rather than viewing individual correlations as nuisance parameters, these tests suggest that these co-movements be taken advantage of to establish new test statistics, thereby completely reversing the previously adopted perspective. The null hypothesis of the two generations of tests infers the existence of a unit root in the series, with the exception of the Hadri (2000) LM test, which assumes the absence of a unit root.

Table 3 presents the first-generation unit root tests of Levin et al. (2002) (LLC), Im et al. (2003) (IPS), and Hadri (2000) (LM), which indicate the stationarity of all model variables in the first difference. Moreover, the stationarity of all variables in the first difference is observed in the second-generation studies of M. H. Pesaran (2003) and M. H. Pesaran (2007), as illustrated in Table 4. This implies that the data have been transformed in a manner that ensures their behavior is time-independent, at least until the initial difference.

The unit root test with break, as originally proposed by Karavias and Tzavalis (2014) and summarized in Table 5, was implemented to enhance our findings. The purpose of this is to verify the stability of the data series under various analysis methods and to guarantee that the conclusions operated from Pesaran’s tests are robust. According to Table 5, the results confirm that all the variables are stationary in the first difference with the presence of breaks linked to economic and financial shocks, namely the global financial crisis and the European sovereign debt crisis (2008–2012) and the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, which began in early 2020. In this case, it is necessary to test the cointegration between the variables in the model. The existence of breaks offers empirical proof of the correlation between ESG and stability in the digital era, particularly in the context of crises.

The presence of several structural breaks in the variables suggests that the relationship will not be stable over the 2005–2022 study period. Thus, it is essential to choose the regime-switching model in this article.

The following section will analyze cross-sectional dependence by employing a variety of tests, including Friedman (1937), Breusch and Pagan (1980), Frees (1995, 2004), M. H. Pesaran (2004, 2006, 2015), and M. H. Pesaran et al. (2008) tests. Designed to ascertain the existence of a dependency relationship among individuals, these assessments are described in Table 6. The existence of a dependency among individuals is confirmed by the majority of these tests, as all of the associated probabilities are less than 1%, as the results indicate. Furthermore, the hypothesis of homogeneity is rejected at the 5% significance level when the p-values of the homogeneity tests are less than 0.05. In addition, the homogeneity test conducted by Pesaran and Yamagata (2008) provides evidence of heterogeneous coefficients.

Implemented to evaluate the cross-sectional independence of the residuals in a fixed-effects regression model, the Breusch and Pagan (1980) test, thereby providing additional support for the aforementioned findings. The Wald statistic was used to evaluate groupwise heteroscedasticity in the residues of the regression model with the fixed effects, and the Breusch and Pagan (1979) and White (1980) tests were implemented upon this foundation. The residuals demonstrate robust cross-sectional independence, as described in Table 7, which underscores the existence of substantial individual heteroscedasticity.

According to the heteroscedasticity test results, the coefficients are associated with a probability that is less than 1% (chi2 statistic = 3.5e + 06) and statistically significant (p-value = 0.000). Consequently, we reject the homoscedasticity hypothesis (H0). Additionally, the autocorrelation test provides evidence of the model’s strong serial autocorrelation, which is significant (p-value = 0.000) and less than 1% (chi2 = 12625.733). Consequently, we reject the H0 hypothesis. These outcomes reinforce our earlier observations regarding the interdependence between individuals and underscore the necessity of considering such heteroscedasticity in our analytical framework.

It is crucial to investigate the existence of a cointegration relationship between the variables under examination and to look at the dependence test because, in the first difference, the majority of the variables in question are predominantly stationary. These outcomes reinforce our earlier observations regarding the interdependence between individuals and underscore the necessity of considering such heteroscedasticity in our analytical framework. According to SN Azmi et al. (2023), Pedroni (1999) is the first to introduce cointegration tests in a panel model configuration. The Kao (1999), Pedroni (2004), and Westerlund (2007) tests were acknowledged as first-generation panel cointegration tests, which resolved the issue of limited observations and handled slope variations and intercepts among panel members. Yet, they overlook the existence of cross-sectional interdependence between individuals. The literature has suggested several panel cointegration tests that consider cross-sectional dependence. The test of second-generation panel cointegration proposed by Persyn and Westerlund (2008) accounted for the presence of cross-sectional dependence among individuals. This test is also useful in cases where the variables have different integration levels, provided that the dependent variable is not stationary at that level, i.e., I(0).

We can conclude that there is at least one cointegrating relationship for all of the variables in our model based on the findings of Table 8, which presents the results of various cointegration tests of the first and second generations. All these tests have a probability lower than the 5% threshold.

PSTAR analysis

We proceeded to re-estimate our fundamental model using the PSTAR strategy described above. To address the issue of serial autocorrelation, initially identified in Table 7, we employed the Chi-square statistic, which yielded a value of 1751.124 with a zero p-value. This confirms the existence of a single lag in the model, a PSTAR (p = 1). The main non-linearity results are shown in Table 9. These results demonstrate the existence of a non-linear effect of the ESG on the BZ_Score with an optimal order “m” equal to 1. Additionally, there are two optimal thresholds (r = 2).

Table 10 findings reveal two optimal thresholds of 6.975 and 33.018, suggesting that the PSTAR model’s transition parameter, with values of 18.557 and 975.09, influences the smooth transition. These results suggest the existence of a non-linear relationship between BZ_Score and ESG. In addition, the Akaike and Schwarz information criteria are respectively equivalent to 8.108 and 8.183, and the RSS (Residual Sum of Squares) value is 7.6e + 7.

After the application of linearity tests, we move on to estimate the PSTAR model. Table 11 displays the results. This table shows three regimes, with the first regime representing an ESG lower than 33.314, the second regime representing an ESG framed between 33.314 and 63.348, and the last regime representing an ESG greater than 63.348.

In the first regime (385 observations), a 1% increase in the ESG score decreases the BZ_Score by 0.245%. In the second regime (970 observations), a 1% increase in the ESG reduces the BZ_Score by 0.171%. In the third regime (499 observations), where the ESG score is higher than 63.348%, a 1% increase in the ESG score increases the BZ_Score by 0.173%.

The two transition functions of the ESG score, are in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3 below.

From these two figures, it is important to note that transitions between regimes are abrupt. The high value indicates that the ESG score has an immediate influence on stability. The continuous effect of the ESG score on stability suggests that changes in favor of ESG commitment have a significant and lasting influence.

Robustness tests: Granger-causality tests

In order to consolidate our findings on the link between ESG scores and banking stability in the digital era, we perform robustness tests based on the new Granger-causality tests, namely Dumitrescu and Hurlin (2012) and Juodis et al. (2021).

Table 12 presents the causal relationship between the model variables of Dumitrescu and Hurlin (2012). The results show a bi-directional causality between NIM, ROA, IUI, MCS, ATM, ESG, and BZ_Score, and a unidirectional relationship move from CIR and GDPG to BZ_Score.

The bi-directional relationship found between engagement in ESG activities, and the stability of European banks is consistent with previous literature (Ben Abdallah et al., 2020; Gaies and Jahmane, 2022). Ben Abdallah et al. (2020) support the classical view that such engagement leads to higher costs that alter bank soundness. On the other hand, bank soundness favors sustainable development investments. In the same vein, Gaies and Jahmane (2022) confirm this bi-directional relationship, pointing out that the stability of European banks encourages engagement in ESG activities, which in turn positively affects their stability.

The estimates of the Granger-causality test of Juodis et al. (2021) are presented in Table 13 to consolidate the results below, which are nearly identical. The majority of the variables are causal for the variable BZ_Score, with the exception of ATM and GDPG, as determined by the jackknife estimator in demi-panel and the transversal estimation of variance with correction of heteroscedasticity.

Discussion

To move away from the long-standing but unsuccessful quest to prove that the relationship between ESG performance and bank stability is either always positive or always negative, this article attempts to develop a contingent perspective that specifies under which conditions the impact is positive or negative, based on the hypothesis of non-linearity of the relationship. To this end, two hypotheses are put forward. In line with the overinvestment perspective, H3 (The relationship between ESG scores and bank stability is negative), and in line with the stakeholder perspective, H4 (The effect of European banks’ ESG scores on bank stability is positive). In addition, to account for the digital environment in which banks operate, this study has put forward two hypotheses on the relationship between digitization and bank stability, H1 (The diffusion of ICT has a positive impact on bank stability) and H2 (The technological endowment of the banking sector positively impacts bank stability). Finally, to account for the effect of ESG performance on the relationship between digitization and bank stability, hypothesis H6 (The impact of digitization on bank stability depends on the level of banks’ ESG scores) was issued.

In order to address the research question, we will execute a two-level analysis of the results. Initially, the interpretation will concentrate on the influence of ESG performance on bank stability in order to either confirm or disprove our research hypotheses (H3, H4, and H5). Secondly, the analysis will concentrate on the interpretation of the impact of digitization on bank stability in order to either confirm or refute our research hypotheses (H1 and H2) and to ascertain whether this effect is contingent upon the ESG score of the banks (H6).

ESG scores and bank stability

Regarding the impact of engagement in ESG activities on bank stability, the study found a negative impact in the first two regimes. Only in the third regime, when ESG scores reach 63.348 and above, does their effect on bank stability shift from weakening to stabilization. These results confirm the non-linear relationship between engagement in ESG activities and bank stability, supporting hypothesis H5. The results of the study are consistent with previous literature suggesting a non-linear relationship (Barnett and Salomon, 2012; Korinth and Lueg, 2022) and, more specifically, with Lupu et al. (2022), who, it should be recalled, support the existence of a non-linear relationship between ESG performance and the financial stability of European banks. The present study, therefore, provides new empirical evidence challenging the assumption of linearity in the relationship between ESG performance and bank stability supported by most of the empirical literature (Gangi et al., 2019; Di Tommaso and Thornton, 2020; Chiaramonte et al., 2022; Neitzert and Petras, 2022).

Regarding the negative effect of ESG scores on bank stability in the first two regimes, the results show that this negative effect becomes weaker in the second regime and then becomes positive in the third regime. These results are consistent with those of Barnett and Salomon (2012), who argue that engagement in social responsibility activities initially leads to a decrease in financial performance, but subsequently, increased investment in social responsibility leads to an increase in financial performance. By translating an improvement in financial performance into a reduction (improvement) in risk (stability), it becomes possible to explain the sequence of negative to positive effects of ESG performance on bank stability.

Therefore, in the absence of a sufficient ESG score (i.e., below 63.348) to transform their ESG investment into a financial return, banks with low ESG performance obtain a negative return on their ESG expenditure, translating into a negative impact on stability. Such results are in line with the classic view of overinvestment, which maintains a negative relationship between ESG performance and financial performance (Friedman, 1970) and consequently alters the bank’s stability. From this perspective, ESG investments are a waste of resources, acting negatively on the bank’s performance (Barnea and Rubin, 2010), resulting in increased risk and, therefore, bank fragility. These investments can be seen as agency costs in the sense that managers, concerned about their reputation, make them to the detriment of shareholders’ interests. From this point of view, these banks are considered riskier by investors. The results of the first two regimes thus confirm hypothesis H3. However, as banks invest more and exceed the ESG score of 33.314, the negative impact on bank stability becomes smaller (Regime 2). In other words, before adequate ESG scores (i.e., scores below 63.348), engagement in ESG activities continues to alter bank stability, but to a lesser extent.

In contrast, banks with ESG scores equal to or above 63.348 can transform ESG investments into financial returns, thereby strengthening their stability. Although banks with higher ESG scores have higher costs, these costs are offset by the positive financial returns generated by these additional ESG investments, in line with previous literature (Barnett and Salomon, 2012). The more a bank engages in ESG activities, the more it demonstrates greater transparency, enabling it to garner greater support from stakeholders (W Azmi et al., 2021). Furthermore, these results are close to those of Lupu et al. (2022), who show that high levels of stability are recorded when ESG values are around their 60% percentile. This positive effect of ESG score on bank stability is in line with stakeholder theory, which is consistent with previous literature highlighting that high ESG scores are associated with lower bank insolvency risk (Aevoae et al., 2023; Neitzert and Petras, 2022; Cerqueti et al., 2021; Scholtens and van’t Klooster, 2019). Thus, hypothesis H4 is only retained if ESG scores reach the threshold of 63.348 and above.

Overall, our results suggest that critics and proponents of banks’ commitment to social responsibility are, to some extent, right. Indeed, low or moderate ESG performance (Regimes 1 and 2) is consistent with the conventional view, while high ESG performance (Regime 3) is consistent with the stakeholder view. Thus, our results support Barnett’s (2007) theoretical argument that social responsibility commitment enables a stakeholder influence capacity that enhances the ability to convert ESG investments into financial returns and, consequently, improves bank stability. The accumulation of this stakeholder influence capacity means that the benefits of ESG performance increase at a higher rate than the costs, enabling a shift from a negative relationship between ESG performance and bank stability to a positive one.

The role of ESG performance in the relationship between digitization and bank stability

The digital era in which European banks operate favors their stability through the spread of ICT. This evidence follows from the results presented above (Table 13), showing that ICT diffusion in terms of the Internet (IUI) and mobile devices (MCS) has a positive impact on bank stability in all three regimes. These results are consistent with previous literature supporting the “innovation-stability” hypothesis in studies concerning the European banking sector (Del Gaudio et al., 2021), thus confirming the first H1 research hypothesis.

In contrast, the technological endowment of the European banking sector, as reflected by ATM penetration, had a negative impact on bank stability in the first regime, which corresponds to an ESG score below 33.314. This result is in line with the literature supporting the “innovation-fragility” vision (Instefjord, 2005; Fostel and Geanakoplos, 2012; Gennaioli et al., 2012), highlighting the distortions introduced by digitization and its contribution to significant risk-taking by banks. On the other hand, the impact of the technological endowment of the European banking sector on bank stability becomes positive for the second regime, where the ESG score is framed between 33.314 and 63.348, and for the last regime, where the ESG score is equal to or above 63.348. Thus, the endowment of technological infrastructure, which reflects the ICT investments of European banks, keeps them away from the risk of insolvency. This positive effect is in line with the extensive literature supporting the “innovation-stability” vision (Hasan et al., 2012; Del Gaudio et al., 2021; Kasri et al., 2022).

This ATM variable, which reflects access to financial services through ICT investments by European banks, with a negative impact on bank stability in the first regime, invalidates research hypothesis H2. However, in the other two regimes, hypothesis H2 is confirmed. Therefore, an interpretation based on the threshold variable is required.

According to the results, European banks with a low ESG score (i.e., below 33.314) are unable to avoid the fragility caused by investments in technological infrastructure. Only in the second regime (i.e., an ESG score between 33.314 and 63.348), do banks manage to avoid the risk of insolvency. In other words, banks with a low commitment to ESG activities become riskier in the digital age. These results are consistent with the literature, which argues that digitization could improve banks’ financial stability by promoting social responsibility (Forcadell et al., 2020; Stefanovic et al., 2021; Salah Mahdi et al., 2023), thus confirming hypothesis H6.

Finally, the study’s findings are consistent with previous literature and provide additional empirical insights into the relationship between ESG performance and bank stability in the digital age. Nevertheless, the discrepancies in the present study’s sample, in terms of both country and bank selection, preclude a direct comparison with previous literature. This calls for further research in this area.

Conclusion and policy recommendations

Unlike researchers who have studied the relationship between bank stability and ESG performance, this study integrates the digital environment in which the banking system evolves to capture the relationship between ESG performance, digitization, and bank stability. From a methodological standpoint, this paper opted for a regime-switching model to test the hypothesis of a non-linearity of the relationship not yet considered in previous studies. Estimates from the PSTAR model revealed evidence, for the occurrence of three regimes with different characteristics. The first regime is characterized by low ESG scores, the second by moderate ESG scores, and the last by high ESG scores.

Overall, our results suggest that critics and proponents of banks’ commitment to social responsibility are, to some extent, right. Indeed, low or moderate ESG performance (Regime 1 and Regime 2) is congruent with the classical perspective, while high ESG score (Regime 3) is consistent with the stakeholder view. So, our results back up Barnett’s (2007) theory that a commitment to social responsibility gives stakeholders more power, which makes it easier to turn ESG investments into financial returns and, in turn, makes banks more stable. The accumulation of this stakeholder influence capacity means that the benefits of ESG score increase at a rate that exceeds the costs, enabling a shift from a negative relationship between ESG performance and bank stability to a positive one. Additionally, banks with a low commitment to ESG activities become riskier in the digital age. These results are consistent with the literature, which argues that digitization could improve banks’ financial stability by promoting social responsibility (Forcadell et al., 2020; Stefanovic et al., 2021; Salah Mahdi et al., 2023).

From an empirical point of view, this study makes three important contributions. First, this paper has provided empirical evidence that the relationship is characterized by non-linearity and contingent upon the level of ESG scores, complementing the recent literature showing the positive impact of high ESG scores on bank stability. Second, to consider the impact of the digital age, this study also examines the impact of ICT diffusion and endowment on bank stability, controlling for ESG scores. To our knowledge, this is the first study to link the impact of digitization on bank stability to ESG activities. Third, this article has highlighted its contribution to the empirical literature from a methodological point of view by opting for the PSTAR model, which allowed us to estimate ESG score thresholds and their impact on the stability of European banks.

In terms of important implications, it is possible to distinguish between those for European banks and those for the Union’s policymakers. Indeed, given the positive impact of ICT on bank stability, European banks need to embrace digitization as a means of better exploiting the opportunities offered by the single market by relaxing the subsidiary-based model and opting for the free provision of services. Furthermore, knowing the threshold for a positive impact of ESG scores on bank stability should encourage them to improve their ESG performance by adopting a digital strategy based on a business model overhaul and improved organizational sustainability. On the policy side, the findings suggest that Europe, and more specifically, the European Commission, needs to ensure that the overall framework for regulating and supervising bank stability is adapted to the changes brought about by digitization and the quest for sustainability. While remaining neutral, policymakers need to strengthen the regulatory infrastructure to support their joint evolution.

Despite these important implications, this study has limitations that suggest areas for future research. Indeed, considering ESG sub-pillars would enable us to capture the relative importance of each pillar in the relationship between ESG performance and bank stability in the digital age. In addition, considering other variables, such as banks’ investments in digital technologies, would provide a more robust basis for understanding the relationship between ESG performance, bank stability, and banks’ digital transformation.

Data availability

Data are available from the DATASTREAM database (https://www.eui.eu/Research/Library/ResearchGuides/Economics/Statistics/DataPortal/datastream), the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) database (https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/publications/wtid.aspx), and the World Development Indicators (WDI) database (https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators). The current study covers the years 2005–2022. It included a panel of 15 European countries (France, Germany, Belgium, Denmark, Czechia, the Netherlands, Finland, Spain, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Norway, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, and Sweden). This paper is based on the 2022 GII (https://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/wipo-pub-2000-2022-section1-en-gii-2022-at-a-glance-global-innovation-index-2022-15th-edition.pdf). The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Aevoae GM, Andrieș AM, Ongena S, Sprincean N (2023) ESG and systemic risk. Appl Econ 55(27):3085–3109. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2022.2108752

Albertini E (2013) Does environmental management improve financial performance? A meta-analytical review. Organ Environ 26(4):431–457. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026613510301

Altunbas Y, Binici M, Gambacorta L (2018) Macroprudential policy and bank risk. J Int Money Finance 81:203–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2017.11.012

Aracil E, Nájera-Sánchez J-J, Forcadell FJ (2021) Sustainable banking: a literature review and integrative framework. Financ Res Lett 42:101932. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2021.101932

Azmi SN, Khan T, Azmi W, Azhar N (2023) A panel cointegration analysis of linkages between international trade and tourism: case of India and South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) countries. Qual Quant. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-022-01602-7

Azmi W, Hassan MK, Houston R, Karim MS (2021) ESG activities and banking performance: International evidence from emerging economies. J Int Financ Mark Inst Money 70:101277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2020.101277

Banna H, Alam MR (2021) Impact of digital financial inclusion on ASEAN banking stability: implications for the post-Covid-19 era. Stud Econ Financ 38(2):504–523. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEF-09-2020-0388

Barnea A, Rubin A (2010) Corporate social responsibility as a conflict between shareholders. J Bus Ethics 97(1):71–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0496-z

Barnett ML (2007) Stakeholder influence capacity and the variability of financial returns to corporate social responsibility. Acad Manag Rev 32(3):794–816. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.25275520

Barnett ML, Salomon RM (2012) Does it pay to be really good? addressing the shape of the relationship between social and financial performance. Strateg Manag J 33(11):1304–1320. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.1980

Batten JA, Choudhury T, Kinateder H, Wagner NF (2022) Volatility impacts on the European banking sector: GFC and COVID-19. Ann Operat Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-022-04523-8

Beck T, Chen T, Lin C, Song FM (2016) Financial innovation: the bright and the dark sides. J Bank Financ 72:28–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2016.06.012

Ben Abdallah S, Saïdane D, Ben Slama M (2020) CSR and banking soundness: a causal perspective. Bus Ethics A Eur Rev 29(4):706–721. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12294

Ben Ali MS (2022) Digitalization and Banking Crisis: A Nonlinear Relationship? J Quant Econom 20(2):421–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40953-022-00292-0

Born B, Breitung J (2016) Testing for serial correlation in fixed-effects panel data models. Econom Rev 35(7):1290–1316. https://doi.org/10.1080/07474938.2014.976524

Bouattour A, Kalai M, Helali K (2024) Threshold effects of technology import on industrial employment: a panel smooth transition regression approach. J Econ Struct 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40008-023-00322-x

Breusch TS, Pagan AR (1979) A simple test for heteroscedasticity and random coefficient variation. Econometrica 47(5):1287. https://doi.org/10.2307/1911963

Breusch TS, Pagan AR (1980) The lagrange multiplier test and its applications to model specification in econometrics. Rev Econ Stud 47(1):239. https://doi.org/10.2307/2297111

Bruno M, Lagasio V (2021) An overview of the European policies on ESG in the banking sector. Sustainability 13(22):12641. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212641

Buallay A (2019) Is sustainability reporting (ESG) associated with performance? Evidence from the European banking sector. Manag Environ Qual Int J 30(1):98–115. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEQ-12-2017-0149

Cerqueti R, Ciciretti R, Dalò A, Nicolosi M (2021) ESG investing: a chance to reduce systemic risk. J Financ Stab 54:100887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2021.100887

Chiaramonte L, Dreassi A, Girardone C, Piserà S (2022) Do ESG strategies enhance bank stability during financial turmoil? Evidence from Europe. Eur J Financ 28(12):1173–1211. https://doi.org/10.1080/1351847X.2021.1964556

Chinoda T, Kapingura FM (2023) The impact of digital financial inclusion and bank competition on bank stability in Sub-Saharan Africa. Economies 11(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11010015

Chollet P, Sandwidi BW (2018) CSR engagement and financial risk: a virtuous circle? International evidence. Glob Financ J 38:65–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfj.2018.03.004

Ciciretti R, Hasan I, Zazzara C (2009) Do internet activities add value? evidence from the traditional banks. J Financ Serv Res 35(1):81–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-008-0039-2

Citterio A, King T (2023) The role of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) in predicting bank financial distress. Financ Res Lett 51:103411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2022.103411

Danisman GO, Demirel P (2019) Bank risk-taking in developed countries: the influence of market power and bank regulations. J Int Financ Mark Inst Money 59:202–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2018.12.007

Del Gaudio BL, Porzio C, Sampagnaro G, Verdoliva V (2021) How do mobile, internet and ICT diffusion affect the banking industry? An empirical analysis. Eur Manag J 39(3):327–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2020.07.003

DeYoung R, Lang WW, Nolle DL (2007) How the Internet affects output and performance at community banks. J Bank Financ 31(4):1033–1060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2006.10.003

Di Tommaso C, Thornton J (2020) Do ESG scores effect bank risk taking and value? Evidence from European banks. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 27(5):2286–2298. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1964

Dumitrescu E-I, Hurlin C (2012) Testing for Granger non-causality in heterogeneous panels. Econ Model 29(4):1450–1460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2012.02.014

Forcadell FJ, Aracil E (2017) European banks’ reputation for corporate social responsibility. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 24(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1402

Forcadell FJ, Aracil E, Úbeda F (2020) The impact of corporate sustainability and digitalization on international banks’ performance. Glob Policy 11(S1):18–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12761

Fostel A, Geanakoplos J (2012) Tranching, CDS, and asset prices: how financial innovation can cause bubbles and crashes. Am Econ J Macroecon 4(1):190–225. https://doi.org/10.1257/mac.4.1.190

Freeman RE (1984) Strategic management. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139192675

Frees EW (1995) Assessing cross-sectional correlation in panel data. J Econ 69(2):393–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(94)01658-M

Frees EW (2004). Longitudinal and panel data analysis and applications in the social sciences (1st edn.). Cambridge University Press

Friedman M (1937) The Use of Ranks to Avoid the Assumption of Normality Implicit in the Analysis of Variance. J Am Stat Assoc 32(200):675–701. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1937.10503522

Friedman M (1970) The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. In: Corporate Ethics and Corporate Governance. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 173–178

Gabrieli S, Salakhova D (2019) Cross-border interbank contagion in the European banking sector. Int Econ 157:33–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inteco.2018.07.002

Gaies B, Jahmane A (2022) Corporate social responsibility, financial globalization and bank soundness in Europe–Novel evidence from a GMM panel VAR approach. Financ Res Lett 47:102772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2022.102772

Galletta S, Goodell JW, Mazzù S, Paltrinieri A (2023) Bank reputation and operational risk: the impact of ESG. Financ Res Lett 51:103494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2022.103494

Gangi F, Meles A, D’Angelo E, Daniele LM (2019) Sustainable development and corporate governance in the financial system: are environmentally friendly banks less risky? Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 26(3):529–547. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1699

Gennaioli N, Shleifer A, Vishny R (2012) Neglected risks, financial innovation, and financial fragility. J Financ Econ 104(3):452–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2011.05.005

Gillan SL, Koch A, Starks LT (2021) Firms and social responsibility: a review of ESG and CSR research in corporate finance. J Corp Financ 66:101889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2021.101889

Gonzalez A, Träsvirta T, Van Dijk D, Yang Y (2017) Panel smooth transition regression models. https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:hhs:hastef:0604

Guérineau S, Léon F (2019) Information sharing, credit booms and financial stability: do developing economies differ from advanced countries? J Financ Stab 40:64–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2018.08.004

Hadri K (2000) Testing for stationarity in heterogeneous panel data. Econ J 3(2):148–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/1368-423X.00043

Hafeez B, Li X, Kabir MH, Tripe D (2022) Measuring bank risk: forward-looking z-score. Int Rev Financ Anal 80:102039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2022.102039

Hasan I, Schmiedel H, Song L (2012) Returns to retail banking and payments. J Financ Serv Res 41(3):163–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-011-0114-y

Helali K, Kalai M (2021) Threshold effect of foreign direct investment on economic growth: New evidence from a panel regime switching models. Glob Bus Econ Rev 25(2). https://doi.org/10.1504/GBER.2021.118212

Huang DZ (2022) An integrated theory of the firm approach to environmental, social and governance performance. Account Financ 62(S1):1567–1598. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.12832

Huang DZX (2021) Environmental, social and governance (ESG) activity and firm performance: a review and consolidation. Account Financ 61(1):335–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.12569

Im KS, Pesaran MH, Shin Y (2003) Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. J Econ 115(1):53–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4076(03)00092-7

Instefjord N (2005) Risk and hedging: do credit derivatives increase bank risk? J Bank Financ 29(2):333–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2004.05.008

Jarque CM, Bera AK (1987) A test for normality of observations and regression residuals. Int Stat Rev / Rev Int de Statistique 55(2):163. https://doi.org/10.2307/1403192

Juodis A, Karavias Y, Sarafidis V (2021) A homogeneous approach to testing for Granger non-causality in heterogeneous panels. Empir Econ 60(1):93–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-020-01970-9

Kalai M, Becha H, Helali K (2024) Threshold effect of foreign direct investment on economic growth in BRICS countries: new evidence from PTAR and PSTAR models. Int J Econ Policy Stud 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42495-023-00126-8

Kao C (1999) Spurious regression and residual-based tests for cointegration in panel data. J Econ 90(1):1–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4076(98)00023-2

Karavias Y, Tzavalis E (2014) Testing for unit roots in short panels allowing for a structural break. Computat Stat Data Anal 76:391–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csda.2012.10.014

Kasri RA, Indrastomo BS, Hendranastiti ND, Prasetyo MB (2022) Digital payment and banking stability in emerging economy with dual banking system. Heliyon 8(11):e11198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11198

Kennedy P (1985) A rule of thumb for mixed heteroskedasticity. Econ Lett 18(2–3):157–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1765(85)90172-7

Kiesel F, Lücke F (2019) ESG in credit ratings and the impact on financial markets. Financ Mark Inst Instrum 28(3):263–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/fmii.12114

Klapper L, Lusardi A (2020) Financial literacy and financial resilience: evidence from around the world. Financ Manag 49(3):589–614. https://doi.org/10.1111/fima.12283

Korinth F, Lueg R (2022) Corporate sustainability and risk management—the U-shaped relationships of disaggregated ESG rating scores and risk in the German capital market. Sustainability 14(9):5735. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095735

Kosmidou K, Kousenidis D, Ladas A, Negkakis C (2017) Determinants of risk in the banking sector during the European Financial Crisis. J Financ Stab 33:285–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2017.06.006

Laeven L, Levine R (2009) Bank governance, regulation and risk taking. J Financ Econ 93(2):259–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2008.09.003

Lee DD, Faff RW (2009) Corporate sustainability performance and idiosyncratic risk: a global perspective. Financ Rev 44(2):213–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6288.2009.00216.x

Levin A, Lin C-F, James Chu C-S (2002) Unit root tests in panel data: asymptotic and finite-sample properties. J Econ 108(1):1–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4076(01)00098-7

Lippai-Makra E, Szládek D, Tóth B, Kiss GD (2021). Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) scores in the service of financial stability for the European banking system. In: Green financial perspectives. Budapesti Corvinus Egyetem. pp. 29–38 https://publicatio.bibl.u-szeged.hu/22070/1/Environmental%2C%20social%20and%20Governance.pdf

Lisin A, Kushnir A, Koryakov AG, Fomenko N, Shchukina T (2022) Financial stability in companies with high ESG scores: evidence from North America using the Ohlson O-score. Sustainability 14(1):479. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010479

Lupu I, Hurduzeu G, Lupu R (2022) How is the ESG reflected in European financial stability? Sustainability 14(16):10287. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610287

McWilliams A, Siegel DS (2011) Creating and capturing value: strategic corporate social responsibility, resource-based theory, and sustainable competitive advantage. J Manag 37(5):1480–1495. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310385696

Mu W, Liu K, Tao Y, Ye Y (2023) Digital finance and corporate ESG. Financ Res Lett 51:103426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2022.103426

Neitzert F, Petras M (2022) Corporate social responsibility and bank risk. J Bus Econ 92(3):397–428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-021-01069-2

Nofsinger JR, Sulaeman J, Varma A (2019) Institutional investors and corporate social responsibility. J Corp Financ 58:700–725. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2019.07.012

Nollet J, Filis G, Mitrokostas E (2016) Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: a non-linear and disaggregated approach. Econ Model 52:400–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2015.09.019

Oikonomou I, Brooks C, Pavelin S (2012) The impact of corporate social performance on financial risk and utility: a longitudinal analysis. Financ Manag 41(2):483–515. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-053X.2012.01190.x

Paltrinieri A, Dreassi A, Migliavacca M, Piserà S (2020) Islamic finance development and banking ESG scores: Evidence from a cross-country analysis. Res Int Bus Financ 51:101100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2019.101100

Pedroni P (1999) Critical values for cointegration tests in heterogeneous panels with multiple regressors. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 61(s1):653–670. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0084.61.s1.14

Pedroni P (2001) Fully modified OLS for heterogeneous cointegrated panels. In: Baltagi BH, Fomby TB, Carter Hill R (eds) Nonstationary Panels, Panel Cointegration, and Dynamic Panels (Advances in Econometrics), vol 15. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Leeds, pp 93–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0731-9053(00)15004-2

Pedroni P (2004) Panel cointegration: asymptotic and finite sample properties of pooled time series tests with an application to the ppp hypothesis. Economet Theory 20(03). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266466604203073

Persyn D, Westerlund J (2008) Error-correction–based cointegration tests for panel data. Stata J Promoting Commun Stat Stata 8(2):232–241. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X0800800205

Pesaran MH (2003) Estimation and inference in large heterogenous panels with cross section dependence. SSRN Electron J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.385123

Pesaran MH (2004) General diagnostic tests for cross section dependence in panels (0435). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.572504

Pesaran MH (2006) Estimation and inference in large heterogeneous panels with a multifactor error structure. Econometrica 74(4):967–1012. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0262.2006.00692.x

Pesaran MH (2007) A simple panel unit root test in the presence of cross‐section dependence. J Appl Econ 22(2):265–312. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.951

Pesaran MH (2015) Testing weak cross-sectional dependence in large panels. Econom Rev 34(6–10):1089–1117. https://doi.org/10.1080/07474938.2014.956623

Pesaran MH, Ullah A, Yamagata T (2008) A bias-adjusted LM test of error cross-section independence. Econ J 11(1):105–127. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23116064

Pesaran M, Yamagata T (2008) Testing slope homogeneity in large panels. J Econ 142(1):50–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2007.05.010