Abstract

Current legislation and market dynamics require and encourage systems to become more open and interoperable. Given this shift, the challenge arises as to how service providers can navigate such environments and whether and how known platform economics are affected by that change. In this context, our work investigates behavior when users interact with services in highly interoperable environments, examining the influence of service attributes and platform economics on service selection and switching decisions, with a focus on the role of transaction cost and time, onboarding time, privacy, ownership, and community. For this purpose, we designed and conducted an extensive survey study with more than 500 respondents that combined a conjoint study with an experimental part on switching scenarios. Our findings suggest that transaction features such as cost, time, and privacy are the main factors in service selection with part-worth utilities being 2.1 to 14.7 times higher than non-transactional features. Additionally, building a strong community and offering ownership opportunities to users are effective strategies for customer retention. Further, we observe that rational choice theory does not explain switching decisions in many cases. Our study has important implications for both industry practitioners and policymakers. Practitioners can use our results to carefully manage effective customer retention strategies, while policymakers can use them to better regulate digital markets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the realm of economics and technology, the capability to select and switch products or services is not just a consumer privilege but a powerful force shaping market success and economic change. Historically, market dynamics were subject to well-researched phenomena such as network effects (Katz and Shapiro, 1985, 1986, 1994) and switching costs (Farrell and Klemperer, 2007; Klemperer, 1987, 1995), largely under conditions of limited interoperability. However, the landscape is shifting. Recent years have witnessed the rise of markets characterized by higher levels of interoperability, in part due to large amounts of venture capital and corporate funds being invested into distributed ledger technology (DLT) (Autore et al., 2021; Friedlmaier et al., 2018) such as Blockchain or Web3 (Di Pierro, 2017; Mohammed et al., 2021; Nofer et al., 2017).

At the same time, new legislative frameworks have fueled this trend from another angle: the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (Li et al. 2019; Tankard, 2016) enshrined the consumer right to data portability, i.e., allowing users to export data from services; however, without an obligation for services to offer import possibilities for data from other services. Going further, the Digital Markets Act (DMA) (Bongartz et al., 2021; Podszun and Bongartz, 2021) defines vertical and horizontal interoperability obligations. Horizontal interoperability concerns services on the same level and aims at sharing network effects among them, while vertical interoperability aims at allowing services on different levels of the value chain to interact (Bourreau and Krämer, 2023). Together, these regulations and technological advances shape the market landscape and influence how users engage with digital services, presumably fostering market settings that exhibit a high degree of interoperability with low switching costs (Farrell and Klemperer, 2007). However, services in this domain are characterized by different attributes that create levers to induce switching costs even when interoperability is high by exerting influence on users’ decision-making processes.

We aim to make an economic and behavioral research contribution to the literature on decentralized markets and to shed light on the relative importance of key service characteristics in service selection and switching scenarios. Thereby, we draw on the existing literature on platform economics, including studies on network effects (Katz and Shapiro, 1985, 1986, 1994) and switching costs (Farrell and Klemperer, 2007; Klemperer, 1987, 1995). To better explain service selection and switching decisions, we determine likely key factors of influence, such as community, ownership, or privacy, that affect choice behavior in highly interoperable domains and subsequently determine their utility values. Using these values, we research whether service selection and switching decisions follow a rational model of consumer choice.

Our research follows a two-phase research approach where we first gather exploratory qualitative insights from targeted interviews to collect key attributes of services in high-interoperability domains that could potentially influence user behavior during service choice and switching. Second, building on the insights from the interviews, we designed and conducted a comprehensive online survey study that replicates service selection and switching in an abstract form. Participants were asked to select different services for financial transactions characterized by a set of five different attributes. Based on their selections, we used a conjoint analysis approach to retrieve individual part-worths of each attribute and followed prior work (Krasnova et al., 2009; Pu and Grossklags, 2017) to assign monetary values to each attribute. After the service selection task, we presented respondents with a second scenario where they were asked to stay with an attributed service or switch to a new option. We then analyzed whether users maximize utility during service selection and switching.

With our work, we aim to answer the following research questions: (1) What defines Web3 as a contemporary interoperable system? (2) How are different attributes of interoperable services (e.g., privacy or price of transactions) valued? (3) Does the valuation of attributes explain switching behaviors between interoperable services?

We find that transaction features such as cost, time, and privacy are the main factors in service selection with part-worth utilities being 2.1 to 14.7 times higher than non-transactional features. Our findings also suggest that building a strong community and offering ownership opportunities to users are effective strategies for retaining customers and that the influence of privacy is stronger during service selection than in the service switching scenarios. Finally, we observe that rational choice theory does not explain switching decisions in many cases.

Our study has important practical implications, informing both industry practitioners and policymakers. Practitioners can benefit from our results by developing effective customer retention strategies, while policymakers can use them to more effectively regulate digital markets and to better understand the economic underpinnings of current regulatory approaches like the GDPR and DMA. Our findings contribute to the growing literature on user behavior in highly interoperable systems and highlight the role of ownership and community, among others, in retaining customers.

We proceed as follows. In Section “Background and related work”, we provide an overview of related and prior research. Methodology and research design are illustrated in Section “Methodology”. All results are presented in Section “Results”. We then discuss our findings in Section “Discussion” and end with implications and concluding remarks in Section “Conclusion”.

Background and related work

The concept of interoperability is multifaceted, encompassing various domains. Historically, it has been pivotal in areas such as government operations during crises, military joint operations, lean production, and supply chain management, focusing primarily on organizational strategies (Brunnermeier and Martin, 2002; Chopra and Meindl, 2007; Dahm and Haindl, 2011; Martínez-Jurado and Moyano-Fuentes, 2014; Tolk and Muguira, 2003). Contemporary research continues to emphasize supply chain management, particularly in automating production and transportation systems (Al-Rakhami and Al-Mashari, 2022; Lechowski and Krzywdzinski, 2022; Melluso et al., 2022; Rammohan, 2023; Vernadat, 2023; Ziegler et al., 2017). Other important areas include healthcare (de Mello et al., 2022; Heacock et al., 2022) and financial systems (Vats, 2023).

Achieving interoperability faces obstacles that extend beyond technological aspects. They include aligning interoperability principles with strategic goals like openness, assessing its impact on ecosystem fragmentation, and considering privacy and data security concerns. Technological performance aspects, including reliability, scalability, and latency, are also crucial (Hodapp and Hanelt, 2022; Mirani et al., 2022). Blockchain technology is often highlighted for its data integrity benefits (Al-Rakhami and Al-Mashari, 2022; Lim et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2023), alongside the need for standardized approaches (Davis, 2022; de Mello et al., 2022; Hughes and Kalra, 2023; Song and Le Gall, 2023; Vernadat, 2023).

In essence, interoperability allows systems to exchange and process both physical and non-physical assets. It requires systems to seamlessly interact, appearing as a unified entity (Brunnermeier and Martin, 2002; Hodapp and Hanelt, 2022; Kosanke, 2006; Litwin et al., 1990; Tolk and Muguira, 2003; van der Veer and Wiles, 2008). Interoperability can be categorized into three levels: syntactic (data exchange), semantic (data understanding), and pragmatic (contextual use) (Antonios et al., 2023; de Mello et al., 2022; Kosanke and Nell, 1999; Stegwee and Rukanova, 2003). Achieving high interoperability relies on consistent data, shared ontologies, and standardized data elements (de Mello et al., 2022; Stegwee and Rukanova, 2003; Tolk and Muguira, 2003), areas where knowledge graphs and natural language processing advancements are particularly beneficial (Melluso et al., 2022).

The Internet exemplifies an interoperable system dominated by large platforms (Devine, 2008; Evans and Schmalensee, 2014; Telang et al., 2004). These platforms facilitate information exchange among users, setting participation rules and sometimes charging fees (Cusumano and Annabelle, 2002; Gawer, 2022; Hein et al., 2020; Täuscher and Laudien, 2018). They act as intermediaries, leveraging network effects and user data. The exchanges can range from data matching to resource booking and content sharing (Hein et al., 2020).

In the platform economy, “platforms” and “marketplaces” are often used interchangeably, but they differ in transaction management. Marketplaces, like Amazon, often manage transactions end-to-end, whereas platforms like early Airbnb and eBay act more as transaction brokers without necessarily providing any transaction infrastructure (Casadeus-Masanell and Thaker, 2012; Gawer, 2021; Guttentag, 2019; Hagiu and Wright, 2013; Hein et al., 2020; Wang and Archer, 2007). Platforms can evolve into ecosystems with additional service providers, enhancing user experience and value (Adner, 2017; Hagiu and Wright, 2015; Hein et al., 2020; Tiwana, 2014).

Understanding the dynamics of these systems is crucial, including how network effects and switching costs influence user choices and what impact interoperability has on platform economics. Network effects and switching costs play a significant role in user retention and service selection (Burnham et al., 2003; Farrell and Klemperer, 2007; Jeon et al., 2023; Katz and Shapiro, 1985, 1986, 1994; Klemperer, 1995). Advances in technology can further shift the dynamics between platforms and users, as argued by Gregory et al. (2021) in the case of “data network effects” caused by the use of machine learning algorithms. Similarly, effects can be expected from removing traditional switching costs by introducing high interoperability. Web3 is theorized to epitomize such a highly interoperable platform, affecting market entry costs and fostering competition (Bourreau and Krämer, 2022; Ethereum, 2023; Roose, 2022; Voshmgir, 2020). High interoperability can lead to competitive pricing and market dynamics, though it can also have anti-competitive effects if not implemented effectively (Bourreau and Krämer, 2022; Colangelo and Borgogno, 2023).

Switching costs deter users from changing services and are influenced by the compatibility of offerings within a network (Farrell and Klemperer, 2007; Klemperer, 1987, 1995). High compatibility may spur competition and diminish the benefits of market incumbency. While empirical studies on the impact of high interoperability are scarce owing to its recent emergence, it is crucial to investigate whether elevated interoperability truly lowers switching costs or merely redistributes them within a service's value proposition. This inquiry extends to whether environments with pronounced service interoperability will witness shorter product lifespans and more diverse market environments, suggesting a shift in focus toward protocols over brand and service engagement. It is hence vital to understand the evolution of switching behavior and its enforcement mechanisms in such contexts.

Behavioral research in settings with low interoperability, such as retail banking and relationship marketing, provides insights but does not fully address the nuances of high-interoperability environments (Chakravarty et al., 2004; Chiu et al., 2005; Gerrard and Barton Cunningham, 2004). Studies in high-interoperability settings often focus on incentive structures, applications of game theory, or user reactions to infrastructure changes (Galdeman et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2019; Toyoda, 2023). Beyond that, we see work investigating psychological aspects of interoperable systems like teamwork or well-being (e.g., Arnold and Schneider 2017, Power et al. 2024), the impact of privacy and security concerns or governance aspects of interoperable (social) networks (Bodle, 2011; Stöger et al., 2024; van der Vlist et al., 2022; Yang, 2023), still without examining in-depth behavioral aspects. Therefore, more research is needed to understand service selection and switching behaviors in environments characterized by high interoperability from a behavioral perspective.

Methodology

Reflecting its exploratory nature, our study unfolds in two distinct phases. In Phase 1, we build a broad understanding of the domain (e.g., Creswell and Creswell 2017, Creswell and Poth 2016). Based on expert interviews, we identify the core attributes of financial services in an interoperable domain such as Web3 that are potentially viable to induce switching costs.

In Phase 2, we use these attributes to design an extensive survey study, which consists of two parts and replicates service selection and switching in an abstract form. In the first part, we place participants in a service selection scenario that is using a conjoint study approach to determine the relative importance and utilities of the service attributes. The utilities also let us track if choices are generally made in a utility-maximizing way. In the second part, we present participants with service switching scenarios where an assigned service is presented alongside a service with a potentially better configuration. This way, we can observe and analyze participants’ switching behaviors and assess if decisions generally follow rational patterns or if certain attribute expressions influence switching decisions. Figure 1 provides an overview on the two phases of the research process.

Interviews

Our survey study was informed by ten interviews with domain experts and prominent researchers in the Web3 arena. These discussions provided valuable insights, leading to the creation of a model for abstracted, exemplary online financial services. These services, primarily focusing on user-to-user money transfers, were chosen due to their increasing interoperability, partly influenced by recent EU legislation (PSD1 and PSD2), constituting a case of in situ access rights that represent a form of (data) interoperability as data can be accessed in real-time and in a continuous manner (Crémer et al., 2019; Martens et al., 2021). The complete interview guidelines are available in the supplementary materials.

We identified potential participants through LinkedIn, using keywords like “Web3,” “NFT,” and “Blockchain.” Our selection criteria emphasized leadership or research and development roles with significant industry impact or involvement in technological advancements. We approached 50 individuals, and 10 interviews were confirmed and conducted. Our analysis predominantly relies on eight of these interviews given variations in the depth of expertise.

The interviewees’ backgrounds were diverse, with most having strong technological expertise, particularly in software engineering or technology-driven decision-making within their organizations. A key finding was the unanimous view of interoperability as a vital element for Web3 applications. Furthermore, a preference for controlled user data access over unrestricted availability was noted. An additional point of discussion was whether Blockchain technology is essential for the realization of Web3.

In total, the interviews generated over 500 statements. These were coded and assigned unique identifiers for ease of reference. The detailed coding scheme is provided in the supplementary materials for further reference. Crucially, the interviews offered valuable insights into both conceptual and technological aspects that influenced the development of attribute sets for the subsequent survey study.

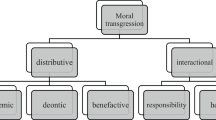

Interviewees highlighted basic financial service attributes, such as transaction fees and transaction time. These attributes are clear characteristics of financial services and hence necessary to be included in the configuration. In addition, the analysis of the interviews revealed attributes with technological and human-factors relevance, including transaction privacy and onboarding time. These features reflect important underlying design choices of interoperable systems and commonly build on some form of distributed ledger technology.

Finally, we incorporated the attributes ownership and community engagement due to their identified influence on user behavior and service loyalty. For instance, one interviewee suggested that service ownership represents a “modern form of user lock-in”, while another highlighted how ownership enhances accountability, fostering a stronger identification with the service and diminishing the likelihood of switching. The concept of allocating specific roles through tokens was discussed as a mechanism for enhancing a sense of belonging to a service. By distributing limited tokens to early adopters, services can decrease the propensity for switching by endowing users with a status that promotes loyalty. The literature supports this view, noting that loyalty programs, particularly those offering non-monetary rewards, significantly deter customers from switching providers (e.g., Lee et al. 2001, Melnyk and Bijmolt 2015). Additionally, the role of community as a pivotal element in fostering customer loyalty was underscored. Interviewees suggested that even in competitive markets, the value of community engagement is considerable, thereby diminishing the tangible benefits of switching to lower-priced services. This can also enhance the developer network, particularly in open-source environments, thereby elevating service quality and, consequently, customer satisfaction and loyalty (e.g., Chang and Chen 2008, Molina-Castillo et al. 2011). This perspective was reinforced by an interviewee who observed that all successful services significantly leverage community engagement. Table 1 provides an overview of all attributes derived from the interviews and later on used in Phase 2 of the study.

Service selection

Phase 2 of our study begins with a choice-based conjoint analysis aimed at determining the relative utilities of various attributes of a hypothetical financial transaction service. Conjoint analysis, a technique commonly used in marketing, helps identify the optimal alignment between a product or service’s features and consumer preferences (Green and Srinivasan, 1978, 1990). This approach enables us to infer the ideal attribute levels by analyzing customer choice patterns and to ascertain the overall utility and relative importance of different attributes (Green and Srinivasan, 1978; Johnson, 1974; Pu and Grossklags, 2017), including their attributed monetary values (Krasnova et al., 2009; Pu and Grossklags, 2017).

While various methods exist for performing conjoint analyses, choice-based conjoint analysis is particularly effective for studies focusing on web services or applications where the utility of individual attributes needs to be assessed (Pu and Grossklags, 2017). This preference is due to the cognitive complexity involved in other methods, such as full-profile conjoint studies, which often result in a high proportion of low-quality responses (Pu and Grossklags, 2015, 2016). In a choice-based conjoint analysis, respondents select from a set of binary choice sets (Desarbo et al., 1995; Green and Srinivasan, 1978), as illustrated in Fig. 2. This process is repeated a limited number of times with different sets, yielding high-quality data due to the reduced cognitive load involved in comparing pairs or triplets of options (Pu and Grossklags, 2017). Typically, respondents can comfortably handle 16–17 choice sets (Bech et al., 2011; Wittink and Cattin, 1989). Our study uses 16 choices, including one repeated set to check for response consistency (Pu and Grossklags, 2017), effectively resulting in 15 unique choices.

A full factorial design for our experiment would involve 64 different scenarios. However, not all attribute combinations are equally relevant, allowing us to employ a fractional factorial design. We derived the fractional factorial using resources like Aizaki and Nishimura (2008), Pu and Grossklags (2017), Burda and Teuteberg (2016), Kraeusel and Möst (2012), and Balderjahn et al. (2009). We used the R library bayesm (Allenby and Rossi, 2002; Rossi, 2023), which utilizes Fedorov’s algorithm (Fedorov, 1972).

Service switching

Our analysis of respondents’ service-switching behaviors involved a methodology similar to the one used for the service selection phase. Participants were presented with a set of ‘cards,’ each representing a service option. The focus was on whether respondents would switch from their currently selected service to an alternative presented alongside it. Each alternative was designed to have a high utility on just one attribute level. By comparing each alternative’s overall utility to the decision made by the user, we assessed whether a decision was rational. The assigned service had lower switching costs compared to the new service, adding a realistic consideration to the decision-making process. Furthermore, to simulate a sense of user attachment or familiarity, we added a distinctive background color and a slightly thicker border to its representation.

The composition of the switching sets, as detailed in Table 2, was crafted to evaluate the influence of ownership and community on users’ switching decisions in a high-interoperability context. In the control group, users were initially engaged with a service where all attributes, except onboarding time, were set to lower utility values. Sequentially, new alternatives were presented, and users had to choose between staying with the existing service or opting for the new one. A similar process was followed for the treatment groups, with the added dimension of either enhanced ownership or community utility. By presenting an improved version of the current service (higher overall utility), rational choice theory would predict a switch to the new option. The actual choices made by the participants, when compared to the predicted ones, allowed us to draw conclusions about the rationality behind their switching behavior. The table illustrates the various attributes and their levels across the different treatment and control groups, providing a clear framework for our analysis.

Data collection

In our study, we gathered 539 responses, which were divided into a training set (80%, 431 respondents) and a test set (20%, 108 respondents) for the main experiment. In the service-switching experiment, the participants were randomly assigned to the control group (189 participants) or one of the two treatment groups: Ownership (169 participants) and Community (181 participants). Additionally, we collected 100 responses for a validation set dedicated to a switching experiment, where no conjoint study was involved.

We acquired all respondents through the platform Prolific Academic. At the conclusion of the survey, participants answered demographic questions and inquiries about their preferences. We utilized established scales where available to gauge respondents’ preferences. Specifically, scales for transaction price were adapted from Goldsmith et al. (2010), transaction privacy from Buck and Burster (2017), and onboarding time from Brockhoff et al. (2015). For areas such as ownership and community preferences, which were unique to our research, we developed bespoke scales. The assessment of switching behavior and readiness to switch drew upon scales from Luzsa et al. (2022). Additionally, impulsiveness was measured using scales from Patton et al. (1995) and Stanford et al. (2009), while technical versatility was gauged using criteria from Neyer et al. (2012) and Neyer et al. (2016). Each survey block consisted of Likert scale questions (ranging from 1 to 5), with responses averaged to yield an overall preference rating. We evaluated the internal coherence of each block using Cronbach’s alpha to ensure consistency. Mean values and standard deviations for each block are shown in Table 3. Further analysis of these scales is subject to future work.

The demographic data from our study (excluding the validation set) revealed a diverse panel with a balanced representation across different backgrounds, age groups, and genders. The participants were predominantly from Europe (84%), with a balanced gender distribution (50% male, 48% female). The majority were aged 30–45 (33%) or 23–30 (26%), held a Bachelor’s degree (41%), and were employed full-time (48%). A detailed overview of the demographic data is provided in the supplemental materials. It is noteworthy, however, that our panel exhibited higher-than-average education levels, a characteristic likely influenced by the nature of our respondent acquisition channel.

Survey procedure

Participants began by consenting to the study’s terms. They were then introduced to detailed instructions about the task, along with comprehensive descriptions of all attributes and their respective levels involved in the conjoint study. The first part of the survey required participants to choose their preferred options from a series of 16 choice sets. Each set presented two distinct options for selection, ensuring a focused decision-making process. Following the recommendation of Pu and Grossklags (2017), we allowed participants to refer back to the instructions during their selections. This approach was implemented to alleviate any uncertainties about the meanings of specific attributes. Consequently, detailed explanations of all attribute levels were accessible below the task window at any time. After completing all 16 selection tasks, participants proceeded to the second part, i.e., the switching scenarios, which were structured in a similar choice-based manner. An example of a switching task can be seen in Fig. 3.

Ethics and validity

For the survey study, we recruited participants from Prolific Academic, which is a popular platform for collecting respondents for research experiments. The study is a standard consumer study that builds on established methodology and only uses hypothetical choice situations (Pu and Grossklags, 2017). The survey did not collect any identifying data.

Quality assurance

To ensure the reliability of the responses collected, we implemented consistency and attention checks. These checks involved using repeated choice or switch sets and straightforward attention checks within the demographic questions section. Based on these criteria, ~10% of the responses were identified as inconsistent or inattentive. To evaluate the robustness of our research design, we conducted analyses both including and excluding the responses flagged during these quality checks. Since no significant issues emerged from this comparison, we ultimately chose not to omit any responses from our final dataset.

In addition, we incorporated a set of test questions designed to gather feedback on the clarity and comprehensibility of the individual attributes and their explanations. The survey’s key attributes were found to be highly understandable and accessible, with only a small fraction of participants experiencing difficulties.

Prior to launching the main study, we executed several test runs with smaller respondent groups. These preliminary trials were aimed at assessing and enhancing the quality of our survey application.

Results

In the following section, we present the outcomes of our study. We begin by examining the service selection process, where we employed choice-based conjoint analysis. This approach enabled us to assess the importance of different service attributes and develop a model capable of predicting users’ service selection decisions.

Following this, we investigate the behavior of users in terms of switching between services in a highly interoperable environment. Utilizing the same predictive model, we noted a significant decrease in the accuracy of predictions when they were based solely on rational choice considerations. This observation indicates that other factors, beyond just rational decision-making, significantly influence users’ tendencies to switch services.

Service selection

In this section, we focus on how the different attributes influence decision-making during the service selection process. Utilizing a conjoint study, we calculated average part-worths for various attributes and employed these part-worths to construct a predictive model based on rational choice theory.

Attribute utilities

By applying a hierarchical Bayesian classifier to our dataset, we were able to determine the average part-worths for each (two-leveled) attribute. The part-worths, starting from a baseline of zero, represent the utility gained from improving each attribute. As indicated in Table 4, transaction costs emerged as a primary determinant in the decision-making process, reflected in its high part-worth. Privacy and transaction time were also significant, ranking second and third in terms of utility.

The utilities detailed in Table 4 represent average values derived from the training set. These averages were instrumental in developing a model capable of predicting service selection choices for a broad user base. However, it is important to acknowledge the variability in individual preferences, which can lead to different utility values on a more detailed level.

Predicted service selection behavior

Rational choice theory states that individuals maximize their expected utility by choosing options that yield the highest utility (e.g., Aleskerov and Monjardet 2002, Hechter and Kanazawa 1997, Hey and Orme 1994, Schoemaker 1982). This theory suggests that rational users would naturally gravitate towards options that align with their individual preferences and offer higher utility. In our study, we explored whether this principle of utility maximization holds true both in the context of initial service selection and during the process of switching services.

To investigate this, we calculated the average utility for each set of choices within the test dataset. We then analyzed whether the majority of respondents selected the option that corresponded to the higher utility, as indicated by the average utilities in Table 4. Our findings reveal a strong alignment with rational choice theory: the model based on derived utilities successfully predicted users’ service selection decisions with an accuracy of 87.50%.

Service switching

The service-switching experiment aimed to determine whether the survey participants would opt to continue with their current service or switch to a new, alternative option. To evaluate this, we utilized the predictive model developed from the service selection phase. That is, we applied the average part-worths from the service selection phase to determine rational choices in the service-switching experiment. Then, we compared the actual choice behavior in the service-switching experiment with the predicted choices.Footnote 1

Our analysis revealed that decisions based on rational choice and utility maximization accurately reflected the behavior of 64.26% of respondents (in the test set) in the switching context. This rate of prediction accuracy is notably lower than the one observed in the service selection phase. Our findings suggest that certain service attributes (community and ownership) play a significant role in deterring users from switching. Notably, attributes such as having an ownership stake in the service or the existence of a robust community were influential factors in dissuading users from making a switch.

Treatment groups

During the switching experiment, respondents were randomly assigned to one of three groups: two treatment groups and a control group. Their task was to evaluate whether they preferred to continue with their current service or switch to a new alternative. The treatment groups, labeled Community and Ownership, were specifically designed to examine the impact of the corresponding attributes on participants’ switching decisions.

Switching behavior and factors of influence

We analyzed the full dataset to evaluate the frequency of user switching behavior over the course of the experiment. Our findings reveal that 92.38% of users switched at least once, while only a small fraction (7.62%) remained consistently committed to their initial service.

We conducted an analysis of individual switching behavior within each treatment group to investigate the existence of any discernible group-level patterns. The treatment groups were enrolled in a service that exhibited a high utility level with respect to community or ownership, whereas the control group did not experience any enhancements. All participants were informed that they had already undergone the onboarding process for the pre-assigned service. The alternatives presented distinct attribute levels, but the improvements in the new alternatives were deterministic and congruent for all groups. Table 5 provides an overview of the comparison of switching across different treatment groups. The overall switch rate was 59.05% for the control group, 48.76% for the Ownership treatment, and 37.68% for the Community treatment.

Our analysis indicates that the addition of a robust community to the assigned service led to a decrease in the number of switching decisions and fostered a greater propensity among users to remain with the current service. Similarly, the treatment group that received a manipulation on ownership (i.e., being informed that they owned a stake in the service) also exhibited a comparable albeit weaker effect. Notably, the overall reduction in the frequency of switching decisions was statistically significant for both treatment groups. We investigate the mutual relationships between different attributes. To that end, switching behavior is analyzed on a per-attribute basis, for each treatment group. The results are shown in Table 6. For example, a comparison of a current selection featuring a strong community with an alternative that has an improved transaction price allows us to calculate the probabilities of a switching or stay decision. Comparing those with a random selection where either probability converged towards 0.5, we investigate whether this effect is statistically significant.

Bounded rational choice phenomena in switching behavior

Contrasting the concept of rational choice in service selection, our empirical data demonstrates a significant deviation from this model in the context of user switching behavior. Specifically, rational choice and utility maximization theories accurately predict only 64.26% of decisions made by respondents in our test set, consisting of 108 individuals (and 64.41% for the training set). This finding reflects a notable reduction of 26.56% in predictability compared to service selection predictions (conjoint analysis). Figure 4 provides a visual representation of this decreased predictability on an individual basis across the entire respondent spectrum within the test set, thereby highlighting a pronounced decline in the effectiveness of prediction models. These insights suggest that rational choice theory may not be entirely sufficient in explaining user switching behavior in contexts where market interoperability is high and switching costs are minimal.

To assess the degree of rationality in respondent behavior, we utilized a categorization methodology that defines participants as rational if their actions predominantly conform to utility maximization. We apply this methodology using a series of thresholds, requiring that 55%, 65%, 75%, 85%, and 95% of decisions adhere to the principle of utility maximization. Table 7 presents the distribution of decisions classified as rational during both service selection and switching, across these varying thresholds. The data reveals a progressive decline in the proportion of rational decisions associated with switching as the threshold for rationality increases. It is noteworthy, however, that the final stage (95% threshold) should be approached with caution, as it implies a level of decision-making precision that may be unrealistically high for practical scenarios.

To assess the statistical significance of the decline in rational decision-making between service selection and switching, we perform t-tests to compare the number of rational decisions made across different threshold levels or buckets (Table 8). Our analysis yields a noteworthy finding: rational decision-making differs significantly across all buckets, except for the 95% bucket, in both the training and test datasets. This result supports the internal validity of the model and suggests that the observed decrease in rational decision-making likely generalizes to a variety of scenarios.

Follow-up survey

To further validate our findings on switching behavior, we conducted a follow-up survey with a new set of 100 participants (validation set), deliberately excluding the conjoint experiment component. This approach was designed to assess whether the integration of a conjoint study within the original experiment had any impact on the observed switching behavior.

In analyzing the follow-up survey data, we utilized the utility values derived from the main experiment to gauge the rationality of decision-making during service switching.Footnote 2 Remarkably, the proportion of decisions that maximized utility remained fairly consistent at 70.00% (compared to 64.26% from the first survey). The consistency in decision-making rationality across both sets of participants reinforces our initial observations. It indicates that the reduced level of rational decision-making identified in the main experiment is not attributable to factors such as survey fatigue or any other influence of the conjoint study.

Discussion

Impact of interoperability on business models

Over the past decade, the world of digital platforms has been expanding rapidly, providing businesses with new opportunities to innovate and reach a broader audience. However, in highly interoperable domains, retaining customers can be challenging as users frequently switch services in a setting where common mechanics of platform economics may no longer apply to individual platforms but rather to the totality of offerings in the ecosystem. We investigate switching behavior in such domains and empirically demonstrate that switching costs can be imposed even when barriers to switching are low. Our results indicate that ownership—the user’s ability to hold a stake in their service—and a strong community can mitigate the impact of interoperability on switching decisions, e.g., users are less likely to switch services when they are part of a strong community or own a share of the service. Therefore, in highly interoperable environments, integrating community building and ownership into business strategies can effectively counteract the effects of interoperability on switching costs.

Our empirical findings are consistent with the qualitative interview studies we conducted in preparation for our primary study. We spoke with experts in the highly interoperable domain of Web3, who currently struggle to tie users to their offerings and rely on community building and ownership to achieve that goal (see supplementary materials).

The majority of respondents in the interviews stated that these actions had a measurable effect on the performance of their businesses or organizations. Some went as far as to allocate more resources to community management than they poured into more traditional marketing efforts. One respondent emphasized the shift away from conventional marketing strategies, noting, “It’s less about traditional go-to-market or advertisement strategies, but more about how to ensure that users stay connected to the community.” This extends to investors who consider metrics such as a community’s genuine user engagement and the level of automated interactions (e.g., bots) as crucial elements during due diligence and project valuation. Ownership in service or immediate benefit for participation were likewise ingrained into most offerings. The interplay of effects of ownership and community further enhances the value of certain (digital) items, signaling an early commitment to a project within emerging communities where long-term membership is associated with a higher reputation. Experiments have shown that players who contribute more to a community and, therefore, build a higher reputation are treated more favorably by other players, leading to a higher overall outcome (see, e.g., Wedekind and Milinski 2000). This phenomenon aligns with broader societal trends toward reputation-based systems, exemplified by the controversial Chinese Social Credit System. This system underscores the role of status and community identification, rewarding individuals with higher reputations (Dai, 2018; Engelmann et al., 2019). Similarly, projects in our problem context can issue unique digital tokens, allowing users to express their status and foster a sense of belonging and community engagement.

Our results suggest that these strategies can likely be generalized and applied in different domains, including more traditional ones. Incumbents with greater resources may be able to manage communities at scale and therefore strengthen their market position. However, the effects may not be sustainable indefinitely, as large groups become increasingly unstable and overall cohesion fades (Carley, 1991, 1990; Demange, 2004). Nonetheless, investing in communities can provide significant support for growing businesses up to a certain threshold.

Further research should explore the underlying cognitive processes that drive users to remain with services where they feel a strong sense of community or have ownership stakes. In any sense, being part of a community instills a sense of belonging and identity (Ashforth and Mael, 1989). Abandoning such social capital may induce a negative utility for users (Ashforth and Mael, 1989; Katz and Shapiro, 1985; Tajfel et al., 1979). This concept is related to the sunk cost fallacy, where prior investments in a community or project make one less inclined to leave (Arkes and Blumer, 1985). Likewise, the endowment effect, which has also been investigated in the context of the value of personal information (Grossklags and Acquisti, 2007), emphasizes the personal attachment to a good or service, which is already in the possession of an individual. Although the impact of ownership might be less pronounced due to the transferability of shares or assets, our findings reflect a similar trend.

Our findings suggest that establishing a sense of belonging and loyalty through community involvement or ownership creates an emotional bond with the service, complicating the decision to switch to a competitor, even if comparable features and benefits are offered. This has profound implications for current and future business models in interoperable domains, implying that incorporating community building and distributed ownership from the onset can be a strategic move to decrease user attrition over the long term.

Decision making during sign-up and switching

Through our analysis, we found that the decision-making behavior of users during service switching cannot be entirely explained by rational choice models. Although our model, which was trained on data from a choice-based conjoint study, could account for 87.5% of the decisions made, the decisions made during the switching experiment did not align with maximizing individual utility based on the attributes examined. In accordance with Loewenstein (1994) and Kashdan and Silvia (2009), we hypothesize that latent factors such as privacy concerns, the appeal of the new, or the comfort of staying with the familiar play a role in explaining this behavior. Other factors, such as cognitive overload, frustration with an existing service, or a declining user experience, may also contribute to the phenomenon. For example, previous research has shown that rational decision-making is bounded by cognitive constraints and availability of information (Simon, 1955), or is subject to heuristics and biases, i.e., users may not systematically analyze the specific configuration of a given service but jump to a conclusion (Tversky and Kahneman, 1974). For platforms that are not subject to high interoperability, research shows a certain level of inertia towards switching to new services (Polites and Karahanna, 2012). Our data, on the other hand, shows that high interoperability does not lead to low levels of switching - the overall switch rate was 48.65% in our experiment - but that inertia to switch can be induced by weighing in on social factors to increase switching costs.

The implications of these findings are significant for service providers. To attract customers from competitors, especially if their services are superior, providers should streamline the decision-making process, possibly through explicit comparisons that highlight their advantages and support rational decisions. Incumbent businesses or those looking to retain their customer base should actively promote their strengths, such as better pricing, privacy policies, or other key features, to counteract the tendency for impulsive or curiosity-driven switching.

Further research is necessary to explore the role of hidden variables in decision-making during service switching. Specifically, understanding the value of using something new or retaining familiarity could be helpful, and dedicated assessments of a user’s preference for the new and tendency to stick with the known may provide additional insights. Additionally, it would be beneficial to examine similar choice situations in domains beyond financial services.

Ensuring competitive equilibria in digital markets

Our study demonstrates that community management significantly influences switching behavior. As a result, even in highly interoperable environments, services can retain customers by imposing community-related switching costs. This indicates that technical interoperability does not automatically lead to a balanced competitive landscape. Consequently, trends and regulations aiming to reduce technical lock-in may not necessarily increase opportunities for new market entrants to gain substantial market share. Specifically, EU legislation designed to enhance the prospects of new offerings by simplifying data transfers, such as the Right to Data Portability (RtDP), can be effectively countered by investing in establishing and nurturing robust and sustainable communities. The fundamental premise of the RtDP is that data control significantly contributes to customer lock-in within digital markets (e.g., De Hert et al. 2018, Jeon et al. 2023, Krämer 2021). The expectation is that easing data access and reducing individual firms’ dominance over data will heighten competition in markets predominantly controlled by large platforms. Contrary to this assumption, our study indicates that efforts focused on crafting technically interoperable systems to lower entry barriers for new market participants (Kranz et al., 2023; Syrmoudis et al., 2021; Wong and Henderson, 2019) might not be as effective as anticipated. This ineffectiveness stems from the existence of alternative mechanisms for imposing switching costs, which remain influential even when barriers related to data are diminished.

Consequently, it is imperative to acknowledge that factors other than data retention play a crucial role in maintaining user loyalty. Solely concentrating on regulations that facilitate data mobility may fall short of the intended objectives. Current legislative measures may have to broaden their scope to encompass additional aspects, such as regulating the growth and influence of company-centric communities and fostering more decentralized infrastructures.

Conclusion

In our study, we shed light on user decision-making in scenarios where service selection and switching occur in highly interoperable contexts. The deployment of an extensive conjoint analysis facilitated an in-depth evaluation of the influence exerted by various service attributes on user preferences and actions. Critical transactional factors such as pricing, timing, and privacy considerations have been identified as pivotal in the service selection process. Notably, our research underscores the importance of elements like community engagement and ownership in influencing service-switching decisions. The cultivation of robust community ties and the provision of ownership opportunities emerge as key strategies for customer retention within these interoperable domains.

Moreover, our study shows that rational choice and utility maximization cannot comprehensively explain switching decisions in highly interoperable environments. An interesting observation is that users exhibit a tendency towards less rational decision-making patterns when transitioning between services, as compared to their initial service selection process. This trend of reduced rationality in decision-making is evident across both our training and test datasets. To address concerns regarding potential experimental fatigue, a subsequent study focusing only on service switching was conducted. The additional data reaffirms our initial findings, thus solidifying the evidence of a decrease in rational decision-making during service switching.

The implications of these insights are profound for both industry professionals and policy regulators. For industry practitioners operating within highly interoperable environments, these findings offer a strategic foundation for devising effective customer retention tactics. Concurrently, for policymakers, the study provides a basis for crafting regulations that promote openness and competition, particularly by counteracting strategies that transcend traditional market dominance through data control.

Still, our study’s insights come with some limitations. The use of a small sample size for interviews, ten participants, is due to the newness of the field, limiting the pool of available experts. Also, the hypothetical setup of our study limits the generalizability of our findings as users may behave differently in real-world situations, e.g., where actual money is involved. Additionally, our participant pool for the quantitative study, sourced from Prolific, may introduce a bias towards individuals with greater technological proficiency and survey-taking experience. Therefore, in light of our results, we recommend that future research continues to explore the nuances of user decision-making in interoperable environments to prepare for emerging setups as well as the potential impact of bounded rationality on service adoption and market dynamics.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

Given the average part-worths from the service selection phase, all switching sets yielded a higher utility for respondents in the control group. For the treatment groups, the switching sets Alt 1, Alt 2, and Alt 3 yielded a higher utility.

We compared the decisions from the follow-up survey to the test set of the main experiment.

References

Adner R (2017) Ecosystem as structure: an actionable construct for strategy. J Manag 43:39–58

Aizaki H, Nishimura K (2008) Design and analysis of choice experiments using R: a brief introduction. Agric Inform Res 17:86–94

Al-Rakhami M, Al-Mashari M (2022) Interoperability approaches of blockchain technology for supply chain systems. Bus Process Manag J 28:1251–1276

Aleskerov F, Monjardet B (2002) Utility maximization, choice and preference, Studies in economic theory. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-662-04992-1

Allenby GM, Rossi PE (2002) Bayesian statistics and marketing. SSRN Electron J 22:304–328

Antonios P, Konstantinos K, Christos G (2023) A systematic review on semantic interoperability in the IoE-enabled smart cities. Internet Things 22:100754

Arkes HR, Blumer C (1985) The psychology of sunk cost. Organ Behav Hum Dec Processes 35:124–140

Arnold R, Schneider A (2017) An app for every step: a psychological perspective on interoperability of mobile messenger apps. In: 28th European regional conference of the international telecommunications society. https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/169444

Ashforth BE, Mael F (1989) Social identity theory and the organization. Acad Manag Rev 14:20–39

Autore DM, Clarke N, Jiang D (2021) Blockchain speculation or value creation? Evidence from corporate investments. Financ Manag 50:727–746

Balderjahn I, Hedergott D, Peyer M (2009) Choice-based Conjointanalyse. In: Baier D and Brusch M (eds) Conjointanalyse. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, p 129–146. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-642-00754-5_9

Bech M, Kjaer T, Lauridsen J (2011) Does the number of choice sets matter? Results from a web survey applying a discrete choice experiment. Health Econ 20:273–286

Bodle R (2011) Regimes of sharing: open APIs, interoperability, and Facebook. Inform Commun Soc 14:320–337

Bongartz P, Langenstein S, Podszun R (2021) The Digital Markets Act: moving from competition law to regulation for large gatekeepers. J Eur Consum Market Law 10:60–67

Bourreau M, Krämer J (2023) Horizontal and vertical interoperability in the DMA. Issue paper, Centre on Regulation in Europe. https://cerre.eu/publications/horizontal-and-vertical-interoperability-in-the-dma/

Bourreau M, Krämer J (2022) Interoperability in digital markets: Boon or bane for market contestability? Working Paper 4172255, SSRN

Brockhoff K, Margolin M, Weber J (2015) Towards empirically measuring patience. Univ J Manag 3:169–178

Brunnermeier SB, Martin SA (2002) Interoperability costs in the US automotive supply chain. Supply Chain Manag Int J 7:71–82

Buck C, Burster S (2017) App information privacy concerns. In: Proceedings of the 23rd Americas conference on information systems (AMCIS). AIS, p 1–10. https://aisel.aisnet.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1056&context=amcis2017

Burda D, Teuteberg F (2016) Exploring consumer preferences in cloud archiving – A student’s perspective. Behav Inform Technol 35:89–105

Burnham TA, Frels JK, Mahajan V (2003) Consumer switching costs: a typology, antecedents, and consequences. J Acad Mark Sci 31:109–126

Carley K (1991) A theory of group stability. Am Sociol Rev 56:331–354

Carley K (1990) Group stability: a socio-cognitive approach. Adv Group Processes 7:1–44

Casadeus-Masanell R, Thaker A (2012) eBay, Inc. and Amazon.com. Case 712-405, Harvard Business School. https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=41660

Chakravarty S, Feinberg R, Rhee EY (2004) Relationships and individuals’ bank switching behavior. J Econ Psychol 25:507–527

Chang HH, Chen SW (2008) The impact of customer interface quality, satisfaction and switching costs on e-loyalty: Internet experience as a moderator. Comput Hum Behav 24:2927–2944

Chiu HC, Hsieh YC, Li YC et al. (2005) Relationship marketing and consumer switching behavior. J Bus Res 58:1681–1689

Chopra S, Meindl P (2007) Supply chain management. Strategy, planning & operation. In: Boersch C and Elschen R (eds) Das Summa Summarum des Management. Gabler, Wiesbaden, Germany, p 265–275. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-8349-9320-5_22

Colangelo G, Borgogno O (2023) Shaping interoperability for the internet of things: The case for ecosystem-tailored standardisation. Eur J Risk Regul 15:137–152

Crémer J, de Montjoye, YA, Schweitzer H (2019) Competition policy for the digital era. Report, Directorate General for Competition (European Commission). https://op.europa.eu/s/zj5W

Creswell JW, Creswell JD (2017) Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage Publications, Los Angeles, CA

Creswell JW, Poth CN (2016) Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. Sage Publications, Los Angeles, CA

Cusumano MA, Annabelle G (2002) The elements of platform leadership. MIT Sloan Manag Rev 43:51–58

Dahm MH, Haindl C (2011) Lean-Management und Six Sigma: Qualität und Wirtschaftlichkeit in der Wettbewerbsstrategie. 2nd edn. Erich Schmidt Verlag, Berlin, Germany

Dai X (2018) Toward a reputation state: The social credit system project of China. Working Paper 3193577, SSRN

Davis, MW (2022) Regulatory and emerging standards. In: Davis M, Kirwan M, Maclay W et al. (eds) Closing the Care Gap with Wearable Devices. Productivity Press, New York, NY

de Hert P, Papakonstantinou V, Malgieri G (2018) The right to data portability in the GDPR: towards user-centric interoperability of digital services. Comput Law Secur Rev 34:193–203

de Mello BH, Rigo SJ, da Costa CA et al. (2022) Semantic interoperability in health records standards: a systematic literature review. Health Technol 12:255–272

Demange G (2004) On group stability in hierarchies and networks. J Polit Economy 112:754–778

Desarbo WS, Ramaswamy V, Cohen SH (1995) Market segmentation with choice-based conjoint analysis. Mark Lett 6:137–147

Devine KL (2008) Preserving competition in multi-sided innovative markets: How do you solve a problem like Google? N C J Law Technol 10:59–117

Di Pierro M (2017) What is the blockchain? Comput Sci Eng 19:92–95

Engelmann S, Chen M, Fischer F et al. (2019) Clear sanctions, vague rewards: how china’s social credit system currently defines “good" and “bad" behavior. In: Proceedings of the Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency. FAT* ’19, ACM, New York, NY, USA, p. 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1145/3287560.3287585

Ethereum (2023) What is Web3 and why is it important? ∣ ethereum.org. https://ethereum.org/en/web3/

Evans D, Schmalensee R (2014) The antitrust analysis of multisided platform businesses. In: Blair RD and Sokol DD (eds) The Oxford handbook of international antitrust economics, Oxford University Press, p 404–448. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199859191.013.0018

Farrell J, Klemperer P (2007) Coordination and lock-in: Competition with switching costs and network effects. In: Handbook of industrial organization, Elsevier, p 1967–2072. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1573448X06030317

Fedorov VV (1972) Theory of optimal experiments. Academic Press, New York, NY

Friedlmaier M, Tumasjan A, Welpe IM (2018) Disrupting industries with blockchain: the industry, venture capital funding, and regional distribution of blockchain ventures. In: Proceedings of the 51st annual Hawaii international conference on system sciences (HICSS). AIS. https://aisel.aisnet.org/hicss-51/in/blockchain/7/

Galdeman A, Zignani M, Gaito S (2023) User migration across Web3 online social networks: Behaviors and influence of hubs. In: ICC 2023 - IEEE International Conference on Communications. IEEE, p 5595–5601

Gawer A (2021) Digital platforms’ boundaries: the interplay of firm scope, platform sides, and digital interfaces. Long Range Plan 54:102045

Gawer A (2022) Digital platforms and ecosystems: remarks on the dominant organizational forms of the digital age. Innovation 24:110–124

Gerrard P, Cunningham BJ (2004) Consumer switching behavior in the Asian banking market. J Serv Mark 18:215–223

Goldsmith RE, Flynn LR, Kim D (2010) Status consumption and price sensitivity. J Mark Theory Pract 18:323–338

Green PE, Srinivasan V (1978) Conjoint analysis in consumer research: Issues and outlook. J Consum Res 5:103–123

Green PE, Srinivasan V (1990) Conjoint analysis in marketing: new developments with implications for research and practice. J Market 54:3–19

Gregory RW, Henfridsson O, Kaganer E et al. (2021) The role of artificial intelligence and data network effects for creating user value. Acad Manag Rev 46:534–551

Grossklags J, Acquisti A (2007) When 25 cents is too much: an experiment on willingness-to-sell and willingness-to-protect personal information. In: Workshop on the economics of information security (WEIS). Pittsburgh, PA

Guttentag D (2019) Progress on Airbnb: a literature review. J Hosp Tourism Technol 10:814–844

Hagiu A, Wright J (2013) Do you really want to be an eBay? Harvard Bus Rev 91:102–108

Hagiu A, Wright J (2015) Multi-sided platforms. Int J Ind Organ 43:162–174

Heacock ML, Lopez AR, Amolegbe SM et al. (2022) Enhancing data integration, interoperability, and reuse to address complex and emerging environmental health problems. Environ Sci Technol 56:7544–7552

Hechter M, Kanazawa S (1997) Sociological rational choice theory. Ann Rev Sociol 23:191–214

Hein A, Schreieck M, Riasanow T et al. (2020) Digital platform ecosystems. Electron Mark 30:87–98

Hey JD, Orme C (1994) Investigating generalizations of expected utility theory using experimental data. Econometrica 62:1291–1326

Hodapp D, Hanelt A (2022) Interoperability in the era of digital innovation: an information systems research agenda. J Inform Technol 37:407–427

Hughes N, Kalra D (2023) Data standards and platform interoperability. In: He W, Fang Y and Wang H (eds) Real-world evidence in medical product development. Springer International Publishing, Cham, Switzerland, p 79–107

Jeon DS, Menicucci D, Nasr N (2023) Compatibility choices, switching costs, and data portability. Am Econ J Microecon 15:30–73

Johnson RM (1974) Trade-off analysis of consumer values. J Mark Res 11:121–127

Kashdan TB, Silvia PJ (2009) Curiosity and interest: the benefits of thriving on novelty and challenge. In: Lopez SJ and Snyder C (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, p 366–374. https://academic.oup.com/edited-volume/28153/chapter/212951868

Katz ML, Shapiro C (1985) Network externalities, competition, and compatibility. Am Econ Rev 75:424–440

Katz ML, Shapiro C (1986) Technology adoption in the presence of network externalities. J Polit Economy 94:822–841

Katz ML, Shapiro C (1994) Systems competition and network effects. J Econ Persp 8:93–115

Klemperer P (1987) Markets with consumer switching costs. Q J Econ 102:375–394

Klemperer P (1995) Competition when consumers have switching costs: an overview with applications to industrial organization, macroeconomics, and international trade. Rev Econ Stud 62:515–539

Kosanke K (2006) ISO standards for interoperability: a comparison. In: Konstantas D, Bourrières JP, Léonard M et al. (eds) Interoperability of enterprise software and applications. Springer-Verlag, London, p 55–64. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/1-84628-152-0_6

Kosanke K, Nell JG (1999) Standardisation in ISO for enterprise engineering and integration. Comput Ind 40:311–319

Kraeusel J, Möst D (2012) Carbon Capture and Storage on its way to large-scale deployment: social acceptance and willingness to pay in Germany. Energy Policy 49:642–651

Kranz J, Kuebler-Wachendorff S, Syrmoudis E et al. (2023) Data portability. Bus Inf Syst Eng 65:597–607

Krasnova H, Hildebrand T, Guenther O (2009) Investigating the value of privacy in online social networks: conjoint analysis. In: Proceedings of the internation conference on information systems (ICIS). AIS, Phoenix, AZ. https://aisel.aisnet.org/icis2009/173

Krämer J (2021) Personal data portability in the platform economy: economic implications and policy recommendations. J Comp Law Economics 17:263–308

Lechowski G, Krzywdzinski M (2022) Emerging positions of German firms in the industrial internet of things: a global technological ecosystem perspective. Global Netw 22:666–683

Lee J, Lee J, Feick L (2001) The impact of switching costs on the customersatisfaction-loyalty link: mobile phone service in France. J Serv Mark 15:35–48

Li H, Yu L, He W (2019) The impact of GDPR on global technology development. J Global Inform Technol Manag 22:1–6

Lim MK, Li Y, Wang C et al. (2021) A literature review of blockchain technology applications in supply chains: a comprehensive analysis of themes, methodologies and industries. Comput Ind Eng 154:107133

Litwin W, Mark L, Roussopoulos N (1990) Interoperability of multiple autonomous databases. ACM Comput Surv 22:267–293

Liu Z, Luong NC, Wang W et al. (2019) A survey on blockchain: a game theoretical perspective. IEEE Access 7:47615–47643. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/8684838

Loewenstein G (1994) The psychology of curiosity: a review and reinterpretation. Psychol Bull 116:75–98

Luzsa R, Mayr S, Syrmoudis E et al. (2022) Online service switching intentions and attitudes towards data portability - the role of technology-related attitudes and privacy. In: Mensch und Computer 2022. ACM, Darmstadt Germany, p 1–13. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3543758.3543762

Martens B, Parker G, Petropoulos G et al. (2021) Towards efficient information sharing in network markets. SSRN Electronic Journal https://www.ssrn.com/abstract=3956256

Martínez-Jurado PJ, Moyano-Fuentes J (2014) Lean management, supply chain management and sustainability: a literature review. J Clean Prod 85:134–150

Melluso N, Grangel-González I, Fantoni G (2022) Enhancing industry 4.0 standards interoperability via knowledge graphs with natural language processing. Comput Ind 140:103676

Melnyk V, Bijmolt T (2015) The effects of introducing and terminating loyalty programs. Eur J Market 49:398–419

Mirani AA, Velasco-Hernandez G, Awasthi A et al. (2022) Key challenges and emerging technologies in industrial IoT architectures: a review. Sensors 22:5836

Mohammed AH, Abdulateef AA, Abdulateef IA (2021) Hyperledger, ethereum and blockchain technology: a short overview. In: 2021 3rd International Congress on Human-Computer Interaction, Optimization and Robotic Applications (HORA). IEEE, Ankara, Turkey, p 1–6. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9461294/

Molina-Castillo FJ, Munuera-Alemán JL, Calantone RJ (2011) Product quality and new product performance: The role of network externalities and switching costs. J Product Innov Manag 28:915–929

Neyer FJ, Felber J, Gebhardt C (2012) Entwicklung und Validierung einer Kurzskala zur Erfassung von Technikbereitschaft. Diagnostica 58:87–99

Neyer FJ, Felber J, Gebhardt C (2016) Kurzskala Technikbereitschaft (TB, technology commitment). Zusammenstellung sozialwissenschaftlicher Items und Skalen (ZIS) http://zis.gesis.org/DoiId/zis244

Nofer M, Gomber P, Hinz O et al. (2017) Blockchain. Bus Inform Syst Eng 59:183–187

Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES (1995) Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol 51, 768–774

Podszun R, Bongartz P (2021) The digital markets act: moving from competition law to regulation for large gatekeepers. J Eur Consum Market Law 10:60–67

Polites GL, Karahanna E (2012) Shackled to the status quo: the inhibiting effects of incumbent system habit, switching costs, and inertia on new system acceptance. MIS Q 36:21

Power N, Alcock J, Philpot R et al. (2024) The psychology of interoperability: a systematic review of joint working between the UK emergency services. J Occup Organ Psychol 97:233–252

Pu Y, Grossklags J (2015) Using conjoint analysis to investigate the value of interdependent privacy in social app adoption scenarios. In: Proceedings of the Internation Conference on Information Systems (ICIS). AIS, Fort Worth, TX. https://aisel.aisnet.org/icis2015/proceedings/SecurityIS/12

Pu Y, Grossklags J (2016) Towards a model on the factors influencing social app users’ valuation of interdependent privacy. Proc Privacy Enhanc Technol 2016:61–81

Pu Y, Grossklags J (2017) Valuating friends’ privacy: does anonymity of sharing personal data matter? In: Thirteenth Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security (SOUPS). USENIX Association, Santa Clara, CA, p 339–355. https://www.usenix.org/conference/soups2017/technical-sessions/presentation/pu

Rammohan A (2023) Revolutionizing intelligent transportation systems with cellular vehicle-to-everything (C-V2X) technology: current trends, use cases, emerging technologies, standardization bodies, industry analytics and future directions. Veh Commun 43:100638

Roose K (2022) What is web3? The New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/03/18/technology/web3-definition-internet.html

Rossi P (2023) bayesm: Bayesian Inference for Marketing/Micro-Econometrics. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/bayesm/index.html

Schoemaker PJH (1982) The expected utility model: its variants, purposes, evidence and limitations. J Econ Lit 20:529–563

Simon HA (1955) A behavioral model of rational choice. Q J Econ 69:99

Song J, Le Gall F (2023) Digital twin standards, open source, and best practices. Springer International Publishing, Cham, p 497–530. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-21343-4_18

Stanford MS, Mathias CW, Dougherty DM et al. (2009) Fifty years of the Barratt impulsiveness scale: an update and review. Pers Ind Differ 47:385–395

Stegwee RA, Rukanova BD (2003) Identification of different types of standards for domain-specific interoperability. In: Proceedings of the MIS quarterly special issue workshop on standard making: a critical research frontier for information systems, 2003, Seattle. p 161–170. https://research.utwente.nl/en/publications/identification-of-different-types-of-standards-for-domain-specifi

Stöger F, Zho, A, Duan H et al. (2024) Demystifying Web3 centralization: the case of off-chain NFT hijacking. In: Baldimtsi F and Cachin C (eds) Financial cryptography and data security. Springer Nature, Cham, Switzerland, p 182–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-47751-5_11

Syrmoudis E, Mager S, Kuebler-Wachendorff S et al. (2021) Data portability between online services: an empirical analysis on the effectiveness of GDPR Art. 20. Proc Privacy Enhanc Technol 2021:351–372

Tajfel H, Turner JC, Austin WG et al. (1979) An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. Organizational identity: a reader 56(65)

Tankard C (2016) What the GDPR means for businesses. Netw Secur 2016:5–8

Telang R, Rajan U, Mukhopadhyay T (2004) The market structure for internet search engines. J Manag Inform Syst 21:137–160

Tiwana A (2014) Platform ecosystems: aligning architecture, governance, and strategy. Morgan Kaufmann

Tolk A, Muguira JA (2003) The levels of conceptual interoperability model. In: Proceedings of the 2003 fall simulation interoperability workshop, vol. 7. p 1–11

Toyoda K (2023) Web3 meets behavioral economics: an example of profitable crypto lottery mechanism design. In: 2023 IEEE international conference on metaverse computing, networking and applications (MetaCom). p 678–679

Tversky A, Kahneman D (1974) Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases: biases in judgments reveal some heuristics of thinking under uncertainty. Science 185:1124–1131

Täuscher K, Laudien SM (2018) Understanding platform business models: a mixed methods study of marketplaces. Eur Manag J 36:319–329

van der Veer H, Wiles A (2008) Achieving technical interoperability. https://portal.etsi.org/CTI/Downloads/ETSIApproach/IOP

van der Vlist FN, Helmond A, Burkhardt M et al. (2022) API governance: the case of Facebook’s evolution. Social Media + Society 8(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051221086228

Vats A (2023) Beyond the hype: developing interoperability standards for digital currency at the G20

Vernadat FB (2023) Interoperability and standards for automation. Springer International Publishing, Cham, p 729–752. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96729-1_33

Voshmgir S (2020) Token economy: how the Web3 reinvents the internet. 2nd edn. BlockchainHub, Berlin

Wang G, Wang Q, Chen S (2023) Exploring blockchains interoperability: a systematic survey. ACM Comput Surv 55:1–38

Wang S, Archer NP (2007) Electronic marketplace definition and classification: literature review and clarifications. Enterpr Inform Syst 1:89–112

Wedekind C, Milinski M (2000) Cooperation through image scoring in humans. Science 288:850–852

Wittink DR, Cattin P (1989) Commercial use of conjoint analysis: an update. J Mark 53:91–96

Wong J, Henderson T (2019) The right to data portability in practice: exploring the implications of the technologically neutral GDPR. Int Data Privacy Law 9:173–191

Yang L (2023) Recommendations for metaverse governance based on technical standards. Humanit Social Sci Commun 10:253

Ziegler S, Baron L, Vermeulen B et al. (2017) F-interop - online platform of interoperability and performance tests for the internet of things. In: Building the future internet through FIRE. River Publishers

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants of our study for contributing their time and Maximilian J. Frank for his research assistance. We further are grateful for funding support from the Bavarian Research Institute for Digital Transformation (bidt). Responsibility for the contents of this publication rests with the authors.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

1. Main Author (Johannes Pecher): Conducted the primary research, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript writing. Played a leading role in conceptualizing the study and interpreting the results. 2. Supervisory Authors (Emmanuel Syrmoudis, Jens Grossklags): These authors jointly supervised this work. They were involved in guiding the research design, methodology, and provided critical revisions of the manuscript. They also assisted in interpreting the findings and provided substantial intellectual contributions to the development of the study. 3. Corresponding Author: Johannes Pecher.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

When we conducted our research in 2022, our institution, TUM, did not require ethics approval for interview-based and survey-based studies. When conducting the study and analyzing the data, we followed expected practices for ethical research; in particular, assuring and maintaining confidentiality of the participants. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants before taking part in the study. Still, no identifying personal data was collected during the experiments.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pecher, J., Syrmoudis, E. & Grossklags, J. Service selection and switching decisions: user behavior in high-interoperability environments. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1585 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04056-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04056-4