Abstract

The present study enhances our understanding of followers’ perceptions of the information credibility of Chinese social media influencers. Employing the heuristic-systematic model, we examined the influence of source credibility and argument quality on the content credibility of micro-influencers and their relational impact on followers’ attitudes and behavioural decisions, with involvement as a moderator. Chinese respondents who follow beauty influencers on Sina Weibo were targeted. The respondents were contacted by posting a web link on WeChat to the survey created on Sojump. Structural equation modelling was used to examine the relationship between variables. The results revealed that argument quality (i.e. systematic cue) and source credibility (i.e. heuristic cue) are significantly affect the information credibility perceived by consumers. The findings also indicate that perceived information credibility has a significant impact on brand/video attitude and purchase intention. There are notable theoretical extensions to the literature on information processing, attitude and consumer behaviour.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the advent of Web 2.0, consumers can share their experiences about product and services with other consumers in the form of online reviews (Filieri and McLeay, 2014), and these online reviews can be favourable or unfavourable narratives about a particular product or service (Hennig et al. 2004). When assessing products (e.g. beauty products), people trust the reviews from ordinary consumers or third parties (e.g., influencers). Numerous studies have emphasized that information shared by social media influencers (SMIs) about product features assist the consumer’s behavioural decisions (Book et al. 2018; Mahmut Modanli et al. 2022) because it reduces vagueness and uncertainty (Sokolova and Kefi, 2020). Influencer marketing is thus an important entry point for consumer companies looking to reach a larger audience. In China, this sector is expected to be worth over 100 billion yuan in 2023, with the overall influencer economy expected to reach nearly 7 trillion yuan by 2025 (Statista, 2024). SMIs have transformed the Chinese market and altered customer behaviour and decision-making. A 2023 survey found that influencer endorsements were particularly effective in advertising fashion and beauty products. According to the same survey, more than two-thirds of Chinese consumers were persuaded by an influencer review or endorsement video; they also thought SMIs were rational shoppers. Over 50% of Chinese respondents had purchased the recommended cosmetics and apparel (Lai Lin Thomala, 2024). It thus comes as no surprise that Chinese fashion advertisers have prioritized influencer promotion in their marketing strategies. Advertisers’ interest in SMIs has, however, led some influencers to game the system. In 2023, around 45% of influencers had fake followers across China’s major social media platforms. Aside from fake social followers, other prevalent types of influencer fraud include disguised interaction, fake sponsored posts and fraudulent giveaways, which can cost businesses a fortune (Statista, 2024). Due to the practical relevance of SMIs, fashion marketers thus confront a huge challenge in selecting and collaborating with the right influencer for brand exposure, accurate positioning and stimulating purchase intention (Sardar et al. 2024).

Several seminal works in the beauty and fashion industry have focused on SMI attributes (i.e. expertise, source credibility, trustworthiness and homophiles), the features of the content produced (i.e. quality of argument, and number of reviews) and their influence on the usefulness of content, content adoption, electronic word-of-mouth and peer purchase intention (Erkan and Evans, 2016; Zhang et al. 2014). Less effort has been made to examine the information products mentioned in posts or videos, or to examine factors associated with content credibility. In the same vein, the credibility of videos or posts shared by influencers may also be a driver of the rise of influencer marketing (Marketing to China, 2019), as a product may seem more reliable when it is recommended by an SMI than when it is simply advertised by the brand (Jin and Phua, 2014). SMIs with high expertise and trustworthiness are perceived to have credible information and objective arguments (Kyung-Hyan and Ulrike, 2009). Djafarova and Rushworth (2017) have suggested that the argument quality of the SMI may affect peer attitude. When a product is endorsed persuasively, followers will have a positive attitude towards SMIs, otherwise they may develop an unfavourable attitude (Cheung et al. 2009). SMIs thought to be more persuasive communicators have the strongest impact on followers, which then enhances purchase decisions (Zak and Hasprova, 2020).

Prior studies have used the elaboration likelihood model (ELM) for their theoretical underpinnings instead of the heuristic-systematic information processing model (HSM). Despite the calls from earlier researchers, few studies have employed heuristic-systematic models in the field of influencer marketing and online content reviews (Son et al. 2020, Yeon et al. 2019). The HSM implies that the consumer uses both modes of information processing (heuristic and systematic) in their purchase decision (Trumbo, 2002). More specifically, source credibility is associated with heuristic information processing, while argument quality is associated with systematic information processing. In brief, Source credibility and argument quality are essential heuristics that profoundly affect users’ evaluation of information (Hovland et al. 1953). Elevated source credibility and robust argument quality can influence users’ opinions and behaviors (Petty and Cacioppo, 1986). Moreover, Focusing on source credibility and argument quality in social media influence research is essential for understanding how users evaluate information, engage with content, and make decisions in a complex digital environment. (Witte, 1992). Few studies have addressed how these two types of cues influence consumer decision-making (Guo et al. 2020; Vrontis et al. 2021; Yeon et al. 2019). We have responded to this call and developed a model that enriches our understanding of the effect of both heuristic (i.e. source credibility) and systematic cues (i.e. argument quality) on follower attitudes and purchase intention through perceived content or information credibility. Earlier research has defined follower involvement, “as a person’s knowledge about the topic being discussed in a post” (Sussman and Siegal, 2003). Although this a dominant aspect of the SMI–follower relationship, follower involvement (i.e. systematic cues) has been overlooked in consumer behavioural studies (Khan et al. 2021; Netemeyer and Teel, 2014; Sardar et al. 2024). This study fills this gap by considering follower involvement in the context of beauty-related content or reviews to examine the credibility of microinfluencers.

There are lacunae in the current literature reviews in the field of influencer marketing (Abdul Wahab et al., 2022, Vrontis et al. 2021). Drawing on the HSM, we present a research model, which deepens our understanding of how informational cues influence the perceived credibility of SMI information or content, the influence of follower involvement on information credibility and its associated impact on followers’ attitude and purchase intention. We specifically address the following research queries:

-

1.

How does SMI source credibility in the form of expertise and trustworthiness and argument quality in the form of informativeness and persuasiveness affect followers’ evaluation of perceived information credibility?

-

2.

Does perceived information and content credibility affect the audience’s attitude towards posts?

-

3.

How does the audience attitude towards posts effects purchase intention?

-

4.

Does follower involvement moderate the relationship among source credibility, argument quality, and perceived information credibility, and if so, how?

This study contributes to research in the field in several ways. First, it advances the relevance of the HSM as a theoretical lens advocated by Chaiken (1980), the application of which has remained limited thus far to user-generated content (Akhtar et al. 2019; I.A. Shah et al. 2022; Zhang et al. 2014), particularly in the setting of microblogging platforms like WeChat and Sina Weibo. We also extend its application in response to the calls from Xiao et al. (2018) and Belanche et al. (2021a) to measure the information credibility of micro-influencers and their impacts on decision-making (Tan et al. 2021). Our study also sheds light on the posts of SMIs on Sina Weibo to better highlight the influence of heuristic and systematic cues on purchase intention via information credibility and consumer attitude, as well as adding new insights to the literature of consumer behaviour. Finally, this study responds to the calls from Zhang et al. (2014) and Chu et al. (2020) to explicate the moderating effects of involvement in the HSM.

The remainder part of this study is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the theoretical grounding, followed by the research model and the development of the hypotheses in Section 3. Section 4 presents the methodology, followed by the analysis and findings in Section 5. Sections 6 and 7 consist of the discussion and concluding remarks about our findings; outline the theoretical and practical implications of the findings; and present the limitations and avenues for future research.

Theoretical Background

Heuristic-Systematic Information Processing Model

The HSM has been extensively used to assess how one receives and processes information (Chaiken, 1980). HSM encompasses two modes for processing information: heuristic and systematic (Bohner et al. 2008). In the systematic information-processing mode, one makes a high cognitive effort to evaluate content-related factors for outcomes (Chaiken, 1980). In the heuristic information-processing mode, one uses little or low cognitive effort to assess cues that are not related to content for outcomes. Prior research as employed both modes of the HSM concurrently especially in the context of online communication studies (James et al. 2021; Lee and Hong, 2021), but the co-occurrence of these modes influences one another and produces three effects (Chaiken and Maheswaran, 1994): attenuation, additivity and bias. The attenuation effect concerns how the systematic mode mitigates the impact of the heuristic mode (Griffin et al. 2002). The additivity effect stresses the autonomous effects of the systematic and heuristic modes on how people assess information when both methods are linked (Ito, 2002). The bias effect addresses how heuristic processing affects systematic processing through biased evaluation (Chaiken and Maheswaran, 1994). The underlying premise is that heuristic factors may permit people to draw inferences concerning message validity (Maheswaran and Chaiken, 1991).

Key Literature on the HSM

The HSM has been employed in various research domains, including information technology, information management, risk prevention and consumer behaviour. For instance, Luo et al. (2013) investigated online phishing scams using HSM as a theoretical lens and found that both argument quality and source credibility influenced the rate of victimization. Vijay et al. (2017) used HSM and identified that neither systematic factors (i.e. information credibility, argument quality) and heuristic factors (i.e. source credibility) had any effect on the adoption of reviews directly but only through the perception of reviewers’ usefulness and the value of such reviews. In the field of risk prevention, another study examined how risk-preventive messages influence individual competency. These findings guide the present study in suggesting that motivation and content quality are significant predictors and have positive impact on individual ability to process risk-preventive messages (Ryu and Kim, 2015). In the field of information management, Son, et al. (2020) adopted the HSM as a theoretical lens to comprehend how Twitter users decide to retweet by classifying tweet content as systematically processed information and the Twitter user’s profile as heuristically processed information. They suggested that a Twitter user profile is a trusted source of information that makes it easier for other users to evaluate the credibility of tweets related to a disaster.

In research on consumer behaviour, Zhang et al. (2014) used the HSM to assess consumers’ perceptions about product reviews. They found that both argument quality and source credibility/review quantity influenced consumer perceptions of online product reviews and purchase intention. In similar vein, Xiao et al. (2018) used HSM to investigate how information processing cues influence SMI content credibility. Their findings suggest that both systematic (argument quality, involvement) and heuristic cues (source advocacy, trustworthiness) affect the credibility of SMIs. Tan et al. (2021) employed the HSM to investigate the impact of the systematic processing (e.g. the informativeness or persuasiveness of advertisements) and heuristic modes (ad poster category) on brand awareness and its ultimate impact on purchase intention. Their findings suggest that systematic factors contribute to brand awareness and purchase intention to a greater extent, while the heuristic factor positively moderates the influence of ad informativeness on brand awareness. Another study integrated the relational communication viewpoint with the HSM to investigate the psychological processes underpinning the impact of influencers’ ISDs on followers’ purchasing intentions. Follower attitudes towards recommended products and SMIs’ perceived altruistic motives for recommending products progressively mitigated the effect of ISDs on purchasing intentions. Zheng et al. (2024) also noted that follower involvement in the message and product knowledge together mitigate this serial mediation effect. Using the HSM, Eslami et al. (2024) examined over 210,000 social media posts and investigated a range of variables such as influencer types, depth of persuasive power and features of individual appearance. Their results illuminate the unique effects of different influencer archetypes (e.g. celebrities and micro-celebrities) on user engagement and demonstrate the complex moderating effects of these archetypes on the connections between individual characteristics, persuasive power and influencer success.

Rationale for Current Study

The basic rationale behind espousing the HSM instead of the ELM is its pertinence and the desire to produce both practical and theoretical advances. First, previous studies have used the ELM to assess how individuals evaluate information credibility (Sauls, 2018) more widely than the HSM, which remains under-researched (Abedin et al. 2019; Hinsley et al. 2022; Son et al. 2020). A comprehensive assessment of the credibility of SMIs on video sharing and microblogging platforms using this model has been particularly overlooked. Second, according to HSM, the two modes of information processing are not mutually exclusive, but the ELM stresses their exclusivity. Rather, the HSM advocates that heuristic and systematic modes can co-occur and affect each other (Griffin et al. 2002). Third, on the presumption of attenuation and bias effects, we deduced that the processing of heuristic and systematic cues should attenuate and bias one another, particularly when information is vague (Tan et al. 2021). Heuristic processing also limits the comprehensive processing of SMI posts, as information searching is complicated. Followers thus depend upon heuristic cues before systematic processing occurs (Lee and Hong, 2021). Based on the theoretical claims of the HSM, we assert that searching for information about beauty products involves risk due to the experiential nature of the products (Phiri and Ponte, 2017) and potential consumer tend to use both approaches (i.e. heuristic and systematic) to information processing for precision and rationality (van Kleef et al. 2004).

Previous studies have clearly illustrated that, in the context of influencer marketing, SMI source credibility (i.e. heuristic cue) and the quality of the argument in the post (i.e. systematic cue) affect the evaluation of information credibility, audience attitude and purchase intention (Zheng et al. 2024). The degree of involvement (i.e. systematic cue) can also strengthen and weaken the relational impact of information credibility on audience decision-making. The HSM has therefore been used here as the theoretical framework to understand comprehensively the effects of both heuristic (i.e. source credibility/influencer credibility in this context) and systematic cues (argument quality) in the evaluation of information credibility and the interaction effect of involvement, and its consequent impact on follower attitude and purchase intention.

Research model and hypothesis development

Heuristic information processing cues

Hovland et al. (1953) proposed a model of source credibility according to which one can determine the effectiveness of a message by using one key feature: source trustworthiness. O’Keefe (1990) advocated source credibility as “a judgment made by a perceiver concerning the believability of a communicator”. Based on this definition, information or content credibility is affected by source credibility (Wathen and Burkell, 2002). A message received from a credible source is more likely to be believed (Dinh and Doan, 2019). Dankwa (2021) also found that individuals were more likely to use source expertise and informative knowledge about the product or subject being discussed to evaluate message credibility, particularly when the content was irrelevant or unfamiliar, while Cheung et al. (2009) found that SMI’s credibility was positively related to perceived content credibility. Researchers have identified several dimensions of source credibility (Sardar, et al. 2024), but this study considered only two imperative dimensions: source expertise and source trustworthiness (M. Xiao et al. 2018). Trustworthiness and credibility both affect an influencer’s efficacy; however, trustworthiness refers to relational and reliable aspects, whereas credibility highlights expertise in their domain and knowledge (Pornpitakpan, 2004). In this study, comprehending the interaction between these two factors might yield insights into how influencers can efficiently engage and influence their audiences.

Expertise

According to Hovland et al. (1953), source expertise is the extent to which a speaker can make sound assertions. Being knowledgeable in a domain of interest, having expertise or even having a reliable title, such as a doctorate, together shape speaker expertise (Pornpitakpan, 2004). Empirical studies have also suggested that communicator expertise rigorously influences the audience’s compliance behaviour: the audience is more likely to conform to a communicator whom they perceive as “expert” (Crisci and Kassinove, 1973). The literature suggests that showcasing source expertise in posts and videos is positively related to consumer engagement (Sarkar et al. 2024), attitude towards the posts or videos and purchase intentions (Braunsberger, 1996; Coutinho et al. 2023).

Trustworthiness

McGinnies and Ward (1980) defined source trustworthiness as the audience’s confidence in the integrity of the communicator to make sound and valid assertions. Audience conviction in source expertise or knowledge is not sufficient; the audience also needs to recognize the source’s integrity, reliability or trustworthiness (Pornpitakpan, 2004). Source credibility (measured with these two dimensions: trustworthiness and expertise) is one of the most important heuristic cue (Coutinho et al. 2023). Followers prime concern is influencer credibility than influencer attractiveness (Sardar et al. 2024), it significantly affects message persuasiveness (Wathen and Burkell, 2002) and the audience evaluation of information credibility (Giffin, 1967). In marketing and advertising in particular, consumer attitude towards brands is greatly affected by source trustworthiness (Saini and Bansal, 2023; Yoon et al. 1998). In the context of present study, perceived information credibility indicates the believability of the content shared through posts or videos posted by Sina Weibo influencers. Extant empirical studies have recommended that heuristic information cues influence a person’s perception of information credibility (Zha et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2014). According to Holt et al. (2019) & Vosoughi et al., (2018) source credibility, argument quality with perceived information credibility on social media is crucial for addressing misinformation to improving decision-making, understanding user behavior, enhancing trust, and promoting healthy public discourse. To measure the information credibility of influencers both source credibility and argument quality plays a pivotal role. Therefore, two dimensions of source credibility—SMI expertise and trustworthiness—are taken as heuristic information cues that influence the follower’s assessment of information credibility (Chen and Chaiken, 1999; Metzger and Flanagin, 2013). The following hypothesis is thus proposed:

H1: Source credibility is positively related with perceived information credibility.

Systematic information processing cues

When an individual is knowledgeable about the subjects being discussed, they are more likely to rely on systematic information cues to process information (Petty and Cacioppo, 1984, 1986b). Argument quality is one systematic information cue that covers content-related perceptions derived from the systematic processing of SMI posts (Xiao et al. 2018). Argument quality has a great impact on the consumer perception of message content and has been extensively examined as a systematic cue in information processing studies (Hussain, et al. 2017). Weibo influencers can share their experience with their followers or make statements. In the present study, the quality of the statement is considered the quality of the argument. Argument information has been considered a precursor of perceived content/information credibility, and a positive affiliation between argument strength and perceived information credibility has been found in the context of Facebook communication. M. Xiao et al. (2018) also reaffirmed that a significant association exists between argument quality and perceived information credibility. The present study primarily focuses on the argument quality of posts/video in general. We also argue that argument quality is a multidimensional construct, rather than one-dimensional; two dimensions of argument quality are proposed: perceived informativeness and perceived persuasiveness. Perceived informativeness is the audience’s overall perceptions about information quality (Ducoffe, 1996), while perceived persuasiveness is the general perception of the strength of persuasiveness embedded in posts (Zhang, 1996). Posts that have high argument quality should be both informative and persuasive (Bhattacherjee and Sanford, 2006), which then contributes to favourable behavioural decisions (Angst and Agarwal, 2009, Tan et al. 2021). We therefore postulate that:

H2: Argument quality is positively related to perceived information credibility.

Information credibility and followers’ attitudes towards mentioned products

We postulate that consumer attitude is the most influential predictor of behavioural decisions (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1977). The marketing and advertising literature has thoroughly considered consumer attitude and its impact on behavioural intentions (Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibáñez, 2012). For instance, product and brand recommendations are widely seen on Weibo posts or videos. Sina Weibo influencers may not only share how-to put-on makeups but also make recommendations about certain brands. An attitude towards-ad-model investigated the factors that influence the viewers’ attitudes towards an advertisement developed by MacKenzie and Lutz (1989), which was similar to dual process theories (Petty and Cacioppo, 1981). Their findings suggest that advertise credibility is perceived as an influential factor in the formation of user attitudes towards the advertisement (Mackenzie and Lutz, 1989).

Extant studies have affirmed the substantial impact of perceived information credibility in attitude formation in diverse settings (Alcántara-Pilar et al. 2024; Greer, 2003; Wang et al. 2008). Greer (2003) found that user attitudes towards a story were greatly influenced by content credibility. In the health sector, the perceived credibility of a website was influenced by an individual assessment of online fitness content (Machackova and Smaheal, 2018). In the context of advertising, extant studies have revealed the significant impact of perceived credibility of endorsers on user attitudes towards the ad or the endorser (Wahid and Hasanah, 2019). A favourable association has also been found between the content credibility of website sponsors and viewer attitudes towards the sponsor (Rifon et al. 2004). In another study, Choi and Rifon (2002) found a positive association between perceived advertisement credibility and attitudes towards the brand and advertisement, and attitudes towards the brand recommended in the blog were greatly affected by the perceived credibility of bloggers. Blog readers were more likely to have a positive brand attitude when they were reading a high-quality blog written by a credible blogger than a less credible one (Chu and Kamal, 2008). The following hypothesis is thus proposed:

H3. Information/content credibility is positively related to the attitude towards the product mentioned in the posts.

Follower’s attitudes and behavioural intention

Consumer behavioural intentions are affected by attitude (Kraft et al. 2005). Behavioural intentions are positive or negative assessments about displaying a certain behaviour (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975). At present, to determine consumer attitudes and facilitate the buying behaviour, online reviews are perceived as a significant type of electronic word-of-mouth (Plummer, 2007). This is in line with the findings of Yang et al. (2010) that user attitudes towards online services significantly affect the intention to use those services. Hsu and Lin (2008) also found a significant effect of attitude on user intention to be a member of blog, while Saxena (2011) demonstrated a significant effect of attitude on user intention to use blogs and make real purchases (Bouhlel et al. 2010). Another study conducted by Mir and Rehman (2013) verified a significant connection between consumers’ attitude towards the content generated by YouTubers and intention to further use the content for purchase decisions. M. Xiao et al. (2018) found that holding a positive attitude towards a product or brand foretell a viewer’s intention to buy a particular product shown in the video streaming website, although consumer attitudes and purchase intentions are closely related to one another. Consumers who hold a positive attitude when watching a product related to make-up or beauty videos on Sina Weibo showed a higher intention to purchase those products. In similar vein, other studies have also found the significant effect of attitude on intention (Saxena, 2011). In such studies, attitude is perceived as consumers’ thoughts, feelings and beliefs towards buying a product or services mentioned in Weibo posts or videos. The following hypothesis is thus proposed:

H4: Attitude towards a post is positively related with consumer purchase intention.

Moderating role of involvement

Involvement is an individual’s information about the subject being debated in a post or video that further instigates the use of systematic means of information processing (Chen and Chaiken, 1999). Earlier studies have suggested that consumer response to advertisements is affected by the viewer’s involvement (Muehling and Laczniak, 1988), although high involvement prevents the message from being processed through the systematic route (Celsi and Olson, 1988). When viewers are less involved, the message is processed via the heuristic route (i.e. viewers focus more on other dimensions such as endorsers) (Fernando et al. 2016) – that is, the endorser has an increased influence on the viewer’s attitude and behavioural decisions. In high involvement conditions, the effect of the endorser on attitude and behavioural decisions is minimal (Petty et al. 1983). For instance, in the context of Sina Weibo, an individual who frequently watches beauty and fashion posts is probably highly involved, so they acknowledge the expertise of SMIs. An individual’s primary focus on the information being processed is entirely through the systematic route. When an individual identifies the information as reliable, they form a favourable attitude and ultimately behavioural intentions. SMIs comparable to celebrities are more likely to affect behavioural intention through the systematic processing mode (Petty et al. 1987). An individual who seldom watches posts or videos is likely less involved and thus focuses more on the attractiveness of the SMI instead of the message content; the message is thus processed heuristically (Perloff, 2010).

Consumer involvement is an important factor influencing content interpretations (Fogg et al. 2003). The degree of involvement in is a noteworthy systematic cue that urges the viewer to process the information vigorously. The level of involvement depends upon the subject’s relevance. The degree of involvement also influences the viewer’s assessment of the message as having weak or strong arguments (Petty and Cacioppo, 1979). High involvement leads an individual to favour messages with strong arguments (i.e. highly informative and persuasive), while undermines the processing of those with weak arguments (i.e. less informative and persuasive) (Braverman, 2008; Sardar et al. 2024).). The higher the involvement in a post or video, the more likely an individual is to depend on the use of a high-quality argument (i.e. highly informative and persuasive) to evaluate information credibility. Researchers have asserted that source credibility (i.e. expertise and trustworthiness) plays a vital role in the assessment of content credibility (Wertgen et al. 2021). In the social media setting, high-involved viewers see SMIs as trusted sources who have expertise and knowledge in a particular domain of interest to a greater extent than less-involved viewers do. In other words, high-involved consumers trust microinfluencers, as they are perceived to be peers (Ding et al. 2019). The relationship between involvement and source credibility cues (i.e. expertise and trustworthiness) thus aids the assessment of information credibility. In the context of Weibo influencer marketing, we can thus expect that involvement moderates the effect of source credibility (i.e. expertise and trustworthiness) and argument quality (i.e. informativeness and persuasiveness) on perceived information credibility. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H5a: Involvement moderates the relationship between source credibility and perceived information credibility when it is high (vs low).

H5b: Involvement moderates the relationship between argument quality and perceived information credibility when it is high (vs low).

Research model

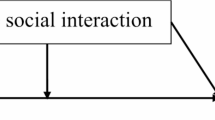

Based on this discussion, we proposed an HSM to examine how informational cues (i.e. heuristic and systematic) affect the perceived content credibility of Weibo influencers. Source credibility was considered a heuristic cue and involvement and argument quality systematic cues; we then inspected their effects on the information or content credibility of SMIs and the consequent impact on audience attitude towards posts and their behavioural responses (See Fig. 1).

This model is based on the heuristic-systematic model by Chaiken (1980). This figure shows the research framework developed to achieve research objectives.

Research methodology

Contextual research setting

China was selected as the setting of this study because it has world’s most active social media population to date. According to Statista (2020), 904 million people access social media frequently, from video-sharing platforms like TikTok and Youku to microblogging sites like WeChat and Sina Weibo. The upsurge of SMIs has not only occurred on global online platforms like Twitter (now called X), Instagram and YouTube but also on their Chinese counterparts (i.e. WeChat, Sina Weibo) (Zexu Guan, 2020). Weibo is now one of the leading platforms for influencer marketing (eMarketer, 2018) and has been rapidly expanding and gaining popularity in China (Hwang and Zhang, 2018). According to China Internet Watch Team (2020), in the first half of 2020, Weibo had 550 million active users monthly, a total count of approximately 85 million users, or a 16% surge on yearly basis. Weibo’s average daily active users were 241 million, a total of approximately 38 million users on a year-over-year basis. Weibo’s vice president, Cao Zhenghui, stated that the company’s surge was mainly due to beauty influencers (Hundundaxue, 2017). Chinese beauty influencers fascinate their followers by generating content ranging from skincare, clothing to makeup and have a greater impact on female viewers (Casalo et al. 2018; Chen, 2018b). We therefore selected female respondents to validate our postulated hypotheses due to the continuous bloom of beauty influencers in the rapid-growing internet industries of China.

Instrument and Measures

The questionnaire items were adapted from the prior literature and later modified slightly to best suit the study context. All constructs were rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (=1) to strongly agree (=7). Perceived source trustworthiness and perceived source expertise were gauged with four items adapted from Ohanian (1990) and Xiao et al. (2018). To measure perceived informativeness, a scale of three items was adapted from Ducoffe (1995, 1996) and Zhang et al. (2014). For perceived persuasiveness, a scale of four items was adapted from Cheung et al. (2009) and Zhang et al. (2014). To measure perceived information credibility, a scale of five items was adapted from Prendergast et al. (2010) and Xiao et al. (2018). Purchase intentions were measured with three items borrowed from Coyle and Thorson (2001), Prendergast et al. (2010) and Erkan and Evans (2016). Attitude towards posts or video was measured with five items adopted from Voss et al. (2003) and Spears and Singh (2004); these were also rated on 7-point scales, the but scale measures varied, ranging from “not fun” to “fun”. The brand or product mentioned in the post was measured on a scale of 1 to 7 from “unappealing” to “appealing”. Finally, for follower involvement, ten semantic differential scale items were adopted from Zaichkowsky (1995, 1994). For example, “How do you feel about the posts of Sina Weibo influencers related to beauty products? Irrelevant ( = 1) to Relevant ( = 7); Not needed ( = 1) to Needed ( = 7); Uninvolving ( = 1) to Involving ( = 7).

The survey instrument contained three sections: Section 1 had three closed-ended questions about the respondents’ demographic information. Section 2 had four screening closed-ended questions, and Section 3 included the 38 items related to the research variables. The survey instrument was initially developed in an English version and later translated into a Chinese version; it was back-translated into English by a bilingual professor and doctoral candidates to confirm the precision of the Chinese-language version (Van de Vijver and Tanzer, 2004). Questions about a few of the items in the Chinese version were rewritten to convey a true reflection of the original meaning in the English version questionnaire. A pilot study was conducted (n = 49) to ensure the content validity of survey instrument, and the collected pilot data showed that scale was reliable and consistent, having Cronbach’s alpha (α) values > 0.70.

Sampling technique and data collection procedures

G*Power 3.1 software was used to determine sample size (Hair et al. 2017), and a minimum sample of 103 was required to attain a power of 80% with a medium effect size (0.50). Data were collected based on purposive sampling (Sekaran and Bougie, 2016) from followers of Sina Weibo beauty influencers. An online questionnaire created on Sojump was used and distributed to the followers of the micro influencers. The recruitment process involved contacting potential respondents by posting a link to the survey on WeChat. It is noted that online surveys can help reach larger numbers of participants and more relevant respondents by eliminating irrelevant ones through screening questions (Denscombe, 2014). The survey began with a cover letter that elucidated the aim of the survey, sought demographic information and provided an operational definition of micro influencers. The data were collected for a period of 8 weeks from August to October 2023, and it took each participant at least 15 min to complete the questionnaire.

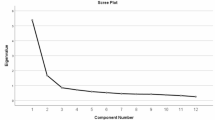

Measurement of scale validation

First, following the guidelines of Ruyter and Bloemer (1999), exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed to ensure the basic factor structure using varimax rotation; six factors were extracted: source credibility (Sc), argument quality (Argq), perceived information credibility (Pci), attitude (Att), purchase intention (PI) and involvement (Inv). Almost all factor loadings (FLs) were above 0.80. The eigenvalues of the factors (1.221, 1.745, 2.932, 2.544, 1.201, 1.156, 2.324, 3.475 and 4.367) indicated that they aggregately elucidated 74.267% of the total variance. Second, to ensure the face and content validity, a marketing professor and doctoral candidates skilled in both English and Chinese were invited to assess the scale items adapted from the prior literature. The experts evaluated the scale items in terms of their precision and relevance to the constructs. The recommendations of the experts were considered, and the scale revised accordingly. The experts reviewed the improved scale items to ensure that all scale items were clear after revision. Face and content validity were thus achieved. Third, a pilot survey was conducted with 68 respondents; 19 responses were discarded due to participant disqualification (i.e. screening questions), missing data or unvarying responses (all 1 or all 7). Consequently, 49 data points were valid for statistical analysis with a response rate of 72.05%. The demographic attributes of the participants indicated that approximately half of the respondents (49.0%) were in the 18–30 age category, followed by 31–45 (40.7%) and above 45 (10.2%). In terms of marital status, 59.1% of the respondents were single and 40.8% were married. Most of the respondents (55.1%) had earned a bachelor’s degree, followed by master’s (32.7%), doctorate (6.12%), high secondary school (4.08%) and high school (2.04%). Most respondents spent 30 min to 1 h (40.8%) on Weibo daily, followed by more than 1 h (22.4%), 15–30 min (18.4%), 5–15 min (14.2%) and 5 min or less (4.08%). The pilot-test reliability results indicated that the scale was reliable. Values for all constructs – source credibility (0.934), argument quality (0.920), information credibility (0.967), attitude towards posts/videos (0.945), purchase intention (0.928) and involvement (0.915) – were within the acceptable range of internal consistency (Rashidin et al., 2022; Nunnally and Bernstein, 1994).

Data analysis: main testing

Respondents’ profile

A total of 794 questionnaires were received; of these, 762 had been filled out completely for an effective response rate of 95.9%. A further 32 surveys were dropped due to disqualification (i.e. screening questions), incomplete data or unvarying answers (e.g. entire 1 or entire 7); a total of 722 survey questionnaires were thus valid for statistical analysis. The demographic information for the respondents can be seen in Table 1; their characteristics were, in general, similar to those of the respondents in the pilot study, although a greater proportion (12.3 vs 4.08% in the pilot study) claimed to spend less than 5 min on Weibo daily. more claimed to spend five.

Common method bias

Due to cross-sectional nature of the study and the use of a single method for data collection, common method bias might be an issue. The present study used two approaches—Harman’s single-factor test (Podsakoff et al. 2003) and the unmeasured latent method construct (ULMC) following Liang et al. (2007)—to investigate whether factitious covariance was present in the included variables in the model. According to the results of the Harmon’s single-factor tests, the EFA of all variable items indicated that nine factors had an eigenvalue greater than 1. The first five factors together accounted for 71.016% of the variance: the first factor accounted 26.059%, the second for 16.366%, the third for 12.365%, and the fourth and fifth factors accounted for 9.206 and 7.022%, respectively. No single factor explained most of the variance; no major concerns are reported. The ULMC results indicate that the substantive the factor loadings (R1) were significant, while most method factor loadings (R2) were not statistically significant. The substantive variances (R12) of the items were thus considerably higher than their method variances (R22). The average substantive variance was 0.749, and the average method variance was 0.009. The ratio of substantive variance to average method variance was 83:1 which is far above the criterion (42:1) suggested by Liang et al. (2007). Common method bias therefore did not appear to be an issue in our dataset (see Table 2).

Measurement model analysis

Analysis was carried out in SPSS AMOS graphics version 21. We checked the reliability and the validity of the latent variables through a measurement model by performing confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The CFA output designated good model fit (χ2 (51.968)), df =33, χ2/df = 1.575, CFI = 0.968; NFI = 0.918; IFI = 0.968; TLI = 0.956; AGFI = 0.941; RMSEA = 0.025; SRMR = 0.053) (Hu and Bentler, 1999) and these various statistical fit indices exhibit that all six latent constructs are well measured by their indicators. Reliability was assessed using the Cronbach’s α and composite reliability (CR) values. Table 3 demonstrates that all constructs can be considered reliable as their CR scores are above the cut-off level 0.70 (Hair et al. 2011), ranging from 0.929 to 0.971, and Cronbach’s α values surpassed the suggested cut-off level >0.70 (Hair, 2010) ranging from 0.930 to 0.973. Fornell and Larcker’s (1981) approach was employed to test the convergent validity, which implies that factor loadings of all items should be greater than 0.70 and significant and the value of the average variance extracted (AVE) of each variable should be greater than 0.50. Table 3 demonstrates that factor loadings of all construct items are above the threshold level ( > 0.70) with values ranging from 0.703 to 0.979 with four exceptions, Att_1, Att_4, Iv_5 and Iv_9. The Att_1 and Att_4 had values of 0.671, 0.64 and Iv_5 and Iv_9 had value of 0.653and 0.685, respectively. These scores were corroborated as >0.60 following the criterion advised by Bagozzi et al. (1991). The AVE values ranged from 0.740 to 0.813, which are above the suggested cut-off level >0.50 (Fornell and Larcker, 1981; Hair et al. 2011), thus establishing the convergent validity (Hair, 2010). The criteria of Fornell and Larcker (1981) were employed to ensure the discriminant validity, as presented in Table 4, where the square roots of the AVE are higher than the correlations between constructs, and the correlation among the constructs does not exceed 0.85 (Kline, 2005).

Structural model results

Structural equation modelling with the maximum likelihood approach was used to evaluate model fit and the hypothesized relationships in the proposed model. Numerous statistical indices, such as χ2, CFI, AGFI, NFI, IFI, TLI, AGFI, RMSEA and SRMR (Hair, 2010) demonstrated adequate model fitness: χ2 = 752.267, df = 360; χ2/df=2.090, RMR = 0.063, AGFI = 0.808, IFI = .938, TLI = .925, CFI = 0.938, PCFI = .776, PNFI = .735; RMSEA = 0.046. All fit indices met the acceptable level of 0.90–1.00 (Hooper et al. 2008; Hu and Bentler, 1999; MacCallum and Hong, 1997; Schreiber, 2008).

Hypothesis testing

In SPSS, we checked for potential multicollinearity in our dataset; the variance inflation factor (VIF) scores suggest that all constructs had VIF scores within the suggested range <3, so multicollinearity was not an issue in our dataset (see Table 5). All path coefficients are shown in Fig. 2. The testing of the hypotheses revealed that source credibility (perceived expertise, perceived trustworthiness) had a significant effect on the perceived information credibility (β = 0.409, t = 7.377, p < 0.001) of Weibo beauty influencers, thus supporting H1. The source credibility model proposes that the effectiveness of a message is assessed by the degree of source expertise and trustworthiness (Ohanian, 1991). An SMI needs to have high niche expertise and trustworthiness (i.e. honest opinions) to build a strong perception among followers about their information credibility (e.g. Jing, Li Jiaqi). Our findings are in line with those of prior studies (Belanche et al. 2021b; Ren et al. 2023). The results showed that argument quality (i.e. informativeness and persuasiveness) is significantly related to perceived content credibility (β = 0.420 t = 7.573, p < 0.001), which is consistent with prior findings that message and argument quality are based on informativeness and persuasiveness (Kim and Kim, 2022). Micro influencers (e.g. Zhang Mofan) are more likely to post informative content or present persuasive knowledge about products than celebrities are (Lou and Yuan, 2019). The high perceived informativeness and persuasiveness of SMIs thus contributes to building a favourable perception about information credibility (Balaban et al. 2022). H2 was thus supported.

The next hypothesis was related to the perceived content credibility of SMIs. With high perceived information credibility, SMIs are often regarded as valuable sources of information and which has a positive impact on the follower’s subsequent attitude (Schouten et al. 2020). Holding a positive perception about SMI credibility makes the follower feel closer to them and thereby generates a favourable opinion about them (Belanche et al. 2021a; Breves et al. 2019). The research findings demonstrated a significant impact of perceived information credibility on follower attitude towards SMI posts/videos (β = 0.296, t = 5.065, p < 0.01), so H3 was supported. Our last hypothesis focused on the follower’s attitude towards SMI posts or videos. Attitude is the main antecedent of behavioural intentions according to the theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen, 1991). The results demonstrated that a follower’s attitude towards posts or videos had a significant effect their purchase intention (β = 0.258, t = 4.365, p < 0.01), thus supporting H4. These findings are in line with earlier studies findings (Nguyen et al. 2023; Li et al. 2023; Balaji et al. 2021; Kim and Kim, 2022).

To test the mediation effects, we employed PROCESS macro 3.2 for SPSS 23.0, and selected Model 6 with 10000 bootstrap samples with a bias-corrected method and 95% confidence interval (CI) (Hayes, 2013). As Table 6 indicates, all coefficients of the indirect path were found to be statistically significant (p < .001) and fell within the confidence intervals of the bootstrapped results. Source credibility significantly indirectly affects purchase intention (βSC → PIC → ATT → PI = 0.023, [CI: 0.008, 0.038]) via perceived information credibility and attitude towards posts. The indirect effect of argument quality affects purchase intention (βARGQ → PIC → ATT → PI = 0.026, [CI: 0.007, 0.044]) via perceived information credibility and attitude towards posts. These findings affirm the mediating role of perceived information credibility and audience attitude towards SMI posts in associating influencer credibility (i.e. expertise, trustworthiness) and argument quality (i.e. informativeness, persuasiveness) with audiences’ actual purchase behaviour.

Figure 2 displays the predicting power (R2) of each response variable. Traditionally, the value of R2 specifies that the percentage of total variance in the endogenous constructs is elucidated by the exogenous constructs. The findings indicate that 28.3% of the total variance were accounted for by source credibility and argument quality in perceived information credibility, the variance of 25.7% in attitude towards posts is explained by perceived information credibility, and 22.4% of variance in purchase intention is accounted for by attitude towards posts. However, this variance is explained by all the predictor variables and exceeded the suggested criterion of 60% advised by Hair et al. (2011). We followed Cohen’s (1973) suggestions for effect size (f2) (small effect = 0.02, medium effect = 0.15, and large effect = 0.35) to inspect the major effect of the research model. We calculated the effect size as Cohen’s f2 = R2/ 1 − R2. Our model thus suggests that the path linking perceived information credibility (f2 = 0.394), follower’s attitude towards posts/videos (f2 = 0.345) and purchase intention (f2 = 0.288) had a large effect size.

Moderating effects of involvement

We assessed the moderating effect of involvement via interaction effects in SPSS. We first inspected the direct effects of the predictor variables and moderator on the response constructs separately for SMI credibility and argument quality, because involvement moderates their association with perceived influencer content credibility. The direct effect of source credibility was statistically significant (F = 104.848, p < 0.001), and the interaction effect of involvement with source credibility (SC×INV) on perceived information credibility was also significant (H5a–βSC×INV → PIC = 0.498 t = 10.003 p < 0.001), which supported H5a. We also found a main direct effect of SMI argument quality on perceived information credibility (F = 193.55, p < 0.001) and a significant interaction effect between involvement with argument quality (ARGQ×INV) on perceived information credibility, which supported H5b (H5b–βARGQ × INV → PIC = 0.553, t = 10.732 p < 0.001). We followed the guidelines of Aiken et al. (1991) to determine the kind of interaction effect via the mean centric approach. We mean-centred the predictors and moderator, then divided the moderator data (i.e. recoding the involvement construct into categories and replace old values with new ones 1 → 1, 2 → 1, 3 → 2, 4 → 2, 5 → 2 and label 1 = low group and 2 = high group). We then developed the interaction term of the mean-centred predictors and moderator. We measured the impact of source credibility and argument quality on perceived content credibility at both low and high levels of follower involvement. As anticipated, source credibility had a noteworthy impact on perceived information credibility at both high (H5a– βSC×INV (high) → PIC = 0.207, t = 3.462, p < 0.001) and low levels of follower involvement (H5a–βSC× INV (low) → PIC = 0.190, t = 3.164, p < 0.01). For argument quality, too, involvement also exhibits a remarkable interaction effect at both high (H5b–βARGQ × INV (high) → PIC = 0. 3160, t = 5.271, p < 0.01) and low levels (H5b–βARGQ × INV (low) → PIC = 0.123, t = 2.034, p < 0.01). These results thus supported our hypotheses H5a and H5b that involvement strengthens the association more at a high level than at a low level.

Discussion and conclusions

Main findings

To make informed decisions, consumers interact with third-party user discussion forums on a continuous basis. The worth of such information depends upon message quality and the credibility of the message source, which are key factors in business success. The present study identified how heuristic and systematic cues affect Weibo influencer’s credibility, particularly at the individual level, thus extending the use of heuristic and systematic processing factors t theoretically and practically. Due to the growth in Chinese internet industries, particularly beauty influencers (Zexu Guan, 2020), the findings of the study offer a worthy outlook to comprehend follower behaviour dependent on the advice and recommendations of beauty SMIs on Weibo.

The findings from the application of structural equation modelling revealed that source credibility is a significant heuristic cue when a consumer evaluates the information credibility of SMIs in the heuristic information processing mode. When followers perceive that the SMI is knowledgeable and has expertise particularly in the beauty and fashion field, they likewise acknowledge his/her trustworthiness, which is an important factor in the evaluation of credibility. This finding is in line with prior research (Le et al. 2021; Xiao et al. 2018) and increases our understanding of the role of heuristic information processing cues in credibility evaluations of SMIs. Metzger et al. (2003) confirmed that the audience does not solely rely on source credibility (i.e. expertise and trustworthiness) but also considers argument quality (i.e. informative and persuasive) for accurate decision-making, although assessing SMI content credibility is an integral measure.

Our second major finding is that argument quality (i.e. systematic cue) has significant impact on information credibility because followers felt that informative content reduced ambiguity and uncertainty, while leading toward purchase. Consumers reap more benefits from clear advice and follow the convincing recommendations of SMIs whose content is highly persuasive in nature. The co-occurrence of heuristic and systematic information processing mode is elucidated by attenuation and bias effect (Zhang et al. 2014). Heuristic information processing implicitly changes the behavioural decisions of an individual by biasing their systematic processing. Here, when the audience found posts or videos shared by their favourite influencers, they anticipated the post content, which may implicitly bias their perception about its credibility. The attenuation effect suggests that the audience initially adopts heuristic processing and later this mode is weakened when the audience is motivated to comprehensively elaborate SMI posts or process the information systematically. Based on this, both heuristic (i.e. source credibility) and systematic cues (i.e. argument quality) influence one another when both modes co-occur simultaneously (Chaiken and Maheswaran, 1994; Chen and Chaiken, 1999). These findings coincide with previous empirical findings (Belanche et al. 2021a; Sardar et al. 2024; Tan et al. 2021; Xiao et al. 2018).

The present findings show that perceived information credibility has a significant effect on audience attitude towards posts, despite earlier information processing research which hypothesized that content credibility does not have any direct impact on the determination of consumer behavioural decision. These findings validate that information credibility, during the initial phase, has a significant impact on audience attitude (β = 0.296). The findings thus verified prior research findings that perceived information credibility is crucial in the development of follower attitude (Le et al. 2021). SMI content also facilitates the follower’s decision-making. Our next finding is associated with relationship between follower attitude and subsequent behaviour by probing the impact of follower’s attitude on purchase intention. Our study verified that a positive attitude increases purchase intention: If consumers find an SMI credible, they are more likely to purchase the products they recommend. This is in line with previous findings (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1977).

We observed the indirect impact of perceived information credibility and attitude towards posts on the association among heuristic cue (i.e. source credibility), systematic cue (i.e. argument quality) and behavioural intentions. We found that perceived information credibility and attitude towards posts have a significant effect on the relationship among heuristic cue (i.e. source credibility), systematic cue (i.e. argument quality) and purchase intention. This is in line with prior research (Sardar et al. 2024; Xiao et al. 2018). Finally, the results point to the moderating impact of involvement as a systematic cue in the influencer marketing context. The literature has shown that involvement influences the interpretation of information i (Fogg et al. 2003). Our results suggest that audience involvement is a prominent systematic information processing factor influencing the evaluation of information credibility. We observed that source credibility and argument quality had robust moderating effects when follower involvement is high versus low. Highly involved consumers perceived SMIS to be more of a trusted source due to their expertise and knowledge in the beauty field than less-involved consumers. This is in line with former empirical findings (Ding et al. 2019).

Conclusions

SMIs on microblogging and video-sharing platforms are vital source for consumers seeking product information, which thus influences behavioural decisions. The current study extends the literature both theoretically and practically by addressing the factors influencing the content credibility of Sina Weibo influencers. Our findings emphasize the significance of both the heuristic and systematic information processing modes while evaluating the credibility of SMI content. Source credibility is an important heuristic cue when a follower assesses content credibility (i.e. SMI is a trustworthy source and has expertise in the sector) in the heuristic information processing mode. In similar vein, argument quality (i.e. content that is informative and persuasive) is a significant systematic cue that accelerates the assessment of SMI content credibility.

We further provide evidence for the stimulated perception of SMI content credibility (i.e. perceiving that the SMI is a credible source in terms of having expertise while providing reliable, informative and persuasive content) predominantly creates a positive attitude in the audience and thus leads to increased positive behavioural outcomes. Involvement has a strong moderating among heuristic, systematic cues and SMI content credibility. In short, we found that the influence of source credibility and argument quality on information credibility depends on the follower’s level of involvement. Followers also use their level of involvement as a decisive factor when determining content credibility. In today’s age of excess data, these findings have implications for both advertising mangers and SMIs. From a practical perspective, the findings suggest the marketers leverage the impact of SMIs’ posts or videos through the lens of our research model, track the performance of SMIs when evaluating partnership credibility and design an examination system whereby followers can freely report any posts/videos with inappropriate, less informative and unpersuasive content. SMIs should also improve the impact of systematic processing on their audience by posting highly informative, persuasive content, which would increase viewer involvement in posts or videos and ultimate have a positive impact on audience decision-making.

Implications

Theoretical implications

This research has made some notable theoretical extensions to the literature of information processing, attitude and consumer behaviour. It addressed the call from Vrontis et al. (2021) for additional studies on influencer marketing using the HSM perspective. Moreover, limited studies have used HSM for consumer assessments of the credibility of SMI content (Yang et al. 2017). The HSM emphasises that heuristic and systematic cues can coincide and interact in complex ways (Attia et al. 2022; Ruiz-Mafe et al. 2018). Consumers can shift back and forth between heuristic and systematic modes while making choices for precision and security (Bilal Sardar et al. 2022; Lee and Hong, 2021). This research extended this implication to SMI content and used heuristic (i.e. source credibility) and systematic (i.e. argument quality and involvement) cues in an elevated explanation setting (i.e. beauty industry) while assessing the credibility of Weibo influencers. Earlier studies (Yang et al. 2017) emphasized that consumers call for the validity of SMI information to reach decision-making, which makes the use of both heuristic and systematic cues are inevitable. Drawing on the attenuation and bias effects (Chen and Chaiken (1999); Xu et al. 2022), the present study concludes that both modes weaken each other during information processing when cues co-occur, which further influences the individual behavioural decisions. The literature on information processing is thus augmented by the presentation of how source credibility and argument quality affect individual evaluations of SMI information credibility on Sina Weibo using the HSM. The impact on perceived information credibility was thoroughly examined because the constructs of source credibility (i.e. expertise and trustworthiness) and argument quality (i.e. informativeness and persuasiveness) were divided into two distinct dimensions.

Second, audience attitude is based on information processing, which offers a direction for decision-making. Earlier studies have explored the direct impact of information credibility on consumers’ attitude (Lin et al. 2016; Majid Esmaeilpour and Farshad Aram, 2016). Our study broadens the effects of information credibility by evaluating its direct association with audience attitudes towards SMI postings and its indirect association with consumers’ behavioural responses (i.e. purchase intention). The information provided about consumers’ attitude adds to the attitude literature by examining the thoughts of the audience after assessing SMI information credibility.

Third, the present study takes a further step towards understanding consumer behaviour in the context of content generated by beauty SMIs on Sina Weibo. It contributes to the consumer behaviour literature by inspecting the role of audience attitude in furthering behavioural decisions. The results show a positive association between attitude towards SMI posts and purchase intentions, which is in line with previous research (Miranda et al. 2019; Akbar Qureshi et al. 2022).

Fourth and last, audience involvement has not been given sufficient scholarly attention, particularly in evaluating the credibility of SMIs (Iqbal et al. 2023; Xiao et al. 2018). The current study thus extends the scholarship, provides a novel technique and clarifies the significance of audience interaction in the context of SMI-generated content. An association for the moderating role of involvement was recognized and postulated by the hypotheses. This study enhances the role of involvement (high vs low) with the interaction of source credibility and argument quality in strengthening the evaluation of the credibility of information provided by SMIs, which has been overlooked.

Practical and managerial implications

At present, SMI recommendations are an influential purchasing factor in China (Dudarenok, 2018; Farman et al. 2022). Brands and social media managers thus need to pay more attention to potential influencers by doing research or looking beyond numerical indicators (i.e. number of followers, popularity) on microblogging platforms. Audunsson (2018) advocated that the focus of influencer marketers has now shifted from who to work with to how to activate the audience. Brands should thus capitalize their resources to leverage the impact of self–influencer connection, monitor the performance of SMIs and keep track of their content quality. From a practical perspective, the findings provide valuable insights for social media marketers and influencers. Acknowledging the importance of user-generated content, marketers should pay extra attention to leveraging the impact of SMI posts or videos through the lens of this research model.

First, as Chinese consumers become more pragmatic, brand managers in the fashion sector should prioritize SMIs who are trustworthy and have a particular focus. For example, Li Jiaqi is a top influencer in the Chinese beauty market and has been recognized for his expertise in makeup. He has millions of fans on social media platforms like Weibo. Viya is another significant name in the cosmetics industry, with over 16 million followers on Weibo. She can sell millions of dollars’ worth of things in minutes because she is perceived as a trustworthy source. Beauty brands should thus choose SMIs like Li Jiaqi and Viya who are effectively reaching their audiences (i.e. have expertise and are trustworthy) and already have a good impact on their purchasing decisions.

Second, marketers should use argument quality to assess the impact of a beauty influencer as a prospective marketing partner. To maximize the influence of systematic information cues, brand managers must monitor SMI performance when evaluating influencer credibility, particularly the informativeness and persuasiveness dimensions (i.e. content quality), rather than focusing solely on the number of followers they have gathered, as fame does not always translate into influence over audiences’ attitudes or behaviour. In terms of fashion influencers, this research is crucial for moulding/amending their content strategies (i.e. moving away from text and photos towards short videos and live streaming) to allow identification and use of components that strengthen their persuasive power.

Third, brand managers and fashion influencers should tailor their content strategy to the level of customer involvement. To achieve high involvement, marketers should emphasize content attributes (strong arguments, informative and persuasive content) while reaching out to their target audience. In contrast, in cases of limited involvement, marketers should prioritize highly reputable influencers over content quality. According to the HSM, those who are less involved are more likely to process information using heuristic pathways, while those who are more involved are more likely to process information through the systematic route.

Fourth, we suggest marketers design an examination system through which followers can freely report any posts or videos whose content is inappropriate, less informative and unpersuasive. The findings of this study are not only effective for marketers but also for SMIs. Less informative and persuasive content is likely to hinder audience purchase behaviour, so we suggest SMIs improve the impact of systematic processing on the audience and be careful about the content of posts or videos, thus increasing viewer involvement in posts or videos.

Limitations and future research

Despite the valued input from the extant literature in the field of influencer marketing in the Chinese social media context, the current research identified certain limitations that can form the basis for future studies. First, this study validated the effects of only two source credibility dimensions (i.e. expertise and trustworthiness). Other source credibility dimensions should therefore be examined, such as attractiveness, likeability and familiarity, to assess their effect on information credibility. Second, our study examined the effect of the posts of beauty influencers on Weibo in general without differentiating brands; future studies should analyse specific types of posts/videos (e.g. product reviews, makeup tutorials), alternate content formats (e.g. videos on Youkhu/Taobao etc.) or other product types (e.g. electronics, apparels, food, travel). Third, this research considered Chinese respondents, and further comparison-based studies are recommended to increase the robustness of these findings and validate the research model, as consumers might react in other ways in other markets and cultures. Consumers in collectivist cultures are usually more likely to seek information from online communities than consumers in individualist cultures. We employed cross-sectional data for our analysis, so future research could use longitudinal data to confirm causal mechanisms.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this research. It can be available on request to correspondence author Md Salamun Rashidin.

References

Abdul Wahab H, Tao M, Tandon A, Ashfaq M, Dhir A (2022) Social media celebrities and new world order. What drives purchasing behavior among social media followers? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 68:103076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.103076

Abedin E, Mendoza A, Karunasekera S (2019) What Makes a Review Credible? Heuristic and Systematic Factors for the Credibility of Online Reviews. 13th Australiasian Conference on Information Systems, Perth Western Australia, p 701–711

Aiken L, West S, Reno R (1991) Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 50(2):179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Ajzen I, Fishbein M (1977) Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychol. Bull. 84(5):888–918

Akbar Qureshi Z, Bilal S, Khan U, Akgül A, Sultana M, Botmart T, Zahran HY, Yahia IS (2022) Mathematical analysis about influence of Lorentz force and interfacial nano layers on nanofluids flow through orthogonal porous surfaces with injection of SWCNTs. Alex. Eng. J. 61(12):12925–12941. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2022.07.010

Akhtar N, Sun J, Chen J, Akhtar M (2019) The role of attitude ambivalence in conflicting online hotel reviews. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 29(4):471–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2019.1650684

Alcántara-Pilar J, Rodriguez ME, Zoran K, Francisco L-C (2024) From likes to loyalty: Exploring the impact of influencer credibility on purchase intentions in TikTok. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 78:103709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2024.103709

Angst CM, Agarwal R (2009) Adoption of electronic health records in the presence of privacy concerns: the elaboration likelihood model and individual persuasion. MIS Q. 33:339–370

Attia N, Akgül A, Seba D, Nour A, Asad J (2022) A novel method for fractal-fractional differential equations. Alex. Eng. J. 61(12):9733–9748. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2022.02.004

Audunsson, S (2018), December 6. 2019 will be the year influencer marketing shifts from who to how. Campaign, available at https://www.campaignlive.co.uk/article/2019-will-year-influencer-marketing-shifts/1520478. (Accessed 20 June 2022)

Bagozzi R, Yi Y, Phillips L (1991) Assessing Construct Validity in Organization Research. Adm. Sci. Q. 36(3):421–458

Balaban D, Szambolics J, Chirică M (2022) Parasocial relations and social media influencers’ persuasive power. Exploring the moderating role of product involvement. Acta Psychol. 230:103731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2022.103731

Balaji MS, Jiang Y, Jha S (2021) Nanoinfluencer marketing: How message features affect credibility and behavioral intentions. J. Bus. Res. Elsev. 136:293–304

Belanche D, Casaló Ariño L, Flavián M, Ibáñez Sánchez S (2021a) Understanding influencer marketing: The role of congruence between influencers, products and consumers. J. Bus. Res. 132(2):186–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.03.067

Belanche D, LV Casaló, M Flavián, S Ibáñez-Sánchez, (2021b), Building influencers’ credibility on Instagram: Effects on followers’ attitudes and behavioral responses toward the influencer, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services,Vol. 61

Bhattacherjee N, Sanford N (2006) Influence Processes for Information Technology Acceptance: An Elaboration Likelihood Model. MIS Quarterly 30(4):805. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148755

Bilal S, Ali Shah I, Akgül A, Taştan Tekin M, Botmart T, Sayed Yousef E, Yahia IS (2022) A comprehensive mathematical structuring of magnetically effected Sutterby fluid flow immersed in dually stratified medium under boundary layer approximations over a linearly stretched surface. Alex. Eng. J. 61(12):11889–11898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2022.05.044

Bohner G, Erb H-P, Siebler F (2008) Information processing approaches to persuasion: Integrating assumptions from the dual- and single-processing perspectives. In: Crano WD, Prislin R (Eds.) Attitudes and attitude change. Psychology Press, New York, NY, p 161–188

Book L, Tanford S, Chang W (2018) Customer reviews are not always informative: The impact of effortful versus heuristic processing. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 41:272–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.01.001

Bouhlel O, Mzoughi N, Ghachem MS, Negra A (2010) Online Purchase Intention, Understanding the Blogosphere Effect. Int. J. e-Bus. Manag. 4(2):37–51

Braunsberger, K (1996), The effects of source and product characteristics on persuasion (Doctoral dissertation), University of Texas at Arlington. Retrieved from http://dspace.nelson.usf.edu:8080/xmlui/handle/10806/6778

Braverman J (2008) Testimonials Versus Informational Persuasive Messages: The Moderating Effect of Delivery Mode and Personal Involvement. Commun. Res. 35(5):666–694. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650208321785

Breves PL, Liebers N, Abt M, Kunze A (2019) The perceived fit between instagram influencers and the endorsed brand: how influencer–brand fit affects source credibility and persuasive effectiveness. J. Advert. Res. 59(4):440–454. https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-2019-030

Casaló Ariño, L & Flavian, C & Ibáñez Sánchez, S. (2018), Influencers on Instagram: Antecedents and consequences of opinion leadership, Journal of Business Research, 117 3 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.005

Celsi RL, Olson JC (1988) The role of involvement in attention and comprehension processes. J. Consum. Res. 15(2):210–224. https://doi.org/10.1086/209158

Chaiken S (1980) Heuristic versus systematic information processing and the use of source versus message cues in persuasion. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 39(5):752–766

Chaiken S, Maheswaran D (1994) Heuristic processing can bias systematic processing: Effects of source credibility, argument ambiguity, and task importance on attitude judgment. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 66(3):460–473

Chen, L, 2018b, Kuangre de zimeiti zouxiang hefang (Where will the fever of wemedia go), China Youth Daily, 27 March, 12

Chen S, Chaiken S (1999) The heuristic-systematic model in its broader context. In: Chaiken S, Trope Y (eds) Dual-process theories in social psychology. The Guilford Press, New York, NY, pp 73–96

Cheung M, Luo C, Sia C, Chen H (2009) Credibility of electronic word-of-mouth: Information and normative determinants of on-line consumer recommendations. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 13(4):9–38

China Internet Watch Team (2020), Weibo MAU grew to 550 million in Q1 2020, available at https://www.chinainternetwatch.com/30609/weibo-q1-2020/ (accessed 28th July 2020)

Choi SM, Rifon NJ (2002) Antecedents and consequences of web advertising credibility: A study of consumer response to banner ads. J. Interact. Advert. 3(1):12–24

Chu SC, Kamal S (2008) The effect of perceived blogger credibility and argument quality on message elaboration and brand attitudes: An exploratory study. J. Interact. Advert. 8(2):26–37

Chu X, Liu Y, Chen X, Ling H (2020) Whose and what Content Matters? Consumers ‘liking behavior toward advertisements in microblogs. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 21:4

Cohen T (1973) Aesthetic/Non‐aesthetic and the concept of taste: a critique of Sibley’s position. Theoria 39(1‐3):113–152

Coutinho F, Dias Á, Pereira L (2023) Credibility of social media influencers: Impact on purchase intention. Hum. Technol. 19:220–237. https://doi.org/10.14254/1795-6889.2023.19-2.5

Coyle JR, Thorson E (2001) The Effects of Progressive Levels of Interactivity and Vividness in Web Marketing Sites. J. Advert. 30(3):65–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2001.10673646

Crisci R, Kassinove H (1973) Effect of perceived expertise, strength of advice, and environmental setting on parental compliance. J. Soc. Psychol. 89(2):245–250

Dankwa DD (2021) Social media advertising and consumer decision-making: The mediating role of consumer engagement. Int. J. Internet Mark. Advert. 15(1):29–53. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJIMA.2021.112786

Denscombe, M (2014), The good research guide: for small-scale social research projects, McGraw-Hill Education. http://hdl.handle.net/2086/10239

Ding, W, Henninger, CE, Blazquez, M, & Boardman, R (2019), Effects of beauty vloggers’ eWOM and sponsored advertising on weibo. In R Boardman, M Blazquez, CE Henninger, & D Ryding (Eds.), Social commerce: consumer behavior in online environments Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. pp. 235-253. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03617-1_13

Dinh H, Doan TH (2019) The impact of senders’ identity on the acceptance of electronic word-of-mouth of consumers in Vietnam. J. Asian Financ., Econ., Bus. 7(2):213–219. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no2.213

Djafarova AE, Rushworth C (2017) Exploring the credibility of online celebrities’ Instagram profiles in influencing the purchase decisions of young female users. Comput. Hum. Behav. 68:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.009

Ducoffe (1995) How consumers assess the value of advertising. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 17(1):1–18

Ducoffe (1996) Advertising value and advertising the web. J. Advert. Res. 36(5):21–35

Dudarenok, J (2018), Influencer Marketing in China: No Longer an Option, Now a Necessity, available at https://chinaeconomicreview.com/influencer-marketing-in-china-no-longer-an-optionnow-a-necessity/ (accessed on January 1, 2020)

eMarketer, (2018), Instagram Leads as a Global Platform for Influencer Marketing available at https://www.emarketer.com/content/instagram-is-the-leading-platform-for-influencer-marketing accessed on 10th December, 2020

Erkan I, Evans C (2016) The influence of eWOM in social media on consumers’ purchase intentions: An extended approach to information adoption. Comput. Hum. Behav. 61:47–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.003

Eslami P, Najafabadi M, Gharehgozli A (2024) Exploring the journey of influencers in shaping social media engagement success. Online Soc. Netw. Media 41:100277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.osnem.2024.100277

Esmaeilpour M, Aram F (2016) Investigating the impact of viral message appeal and message credibility on consumer attitude toward the brand. Manag. Mark. Chall. Knowl. Soc. 11(2):471–483