Abstract

Previous research has focused primarily on replicating bells that were expected to resemble the original closely in terms of material, size, shape, and tone. There has, however, been no effort to use original bells as templates from which to re-create or re-design new bells that deviate significantly in size, yet maintain the shape of the originals in order to address issues in the history of art and in the archeology of ancient China. Experimentation with ancient bells in this field remains largely untapped. This article proposes to re-create bells in enlarged and reduced sizes through casting, based on 3D-printed resin models that have been correspondingly scaled up and down, from a 3D model scanned from a 500 BCE bell that was excavated from Xinzheng in Henan province, China. The study seeks to answer a series of questions, including whether replication of bells was practiced in ancient times, how casters could predict the tones a bell would produce before casting, and how a set of bells used as a musical ensemble could have been developed over history.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction and background

This article offers fresh perspectives on our understanding of bronze chime bells produced in China from approximately 1100 to 500 BCE by using digitally and physically re-created bells as research samples. While replicating ancient Chinese bells has been a common practice in conservation science (Hubei, 1981, 1983; Hu et al. 1981; Li, 2012; Ren, 2013; Wang, 2012, 2021; Zhang, 2016; Fang et al. 2022), using re-created bells in art historical and archeological studies, namely, modern scholars designing new bells with reference to old bells, remains relatively underdeveloped. This approach can help us understand how ancient bells were designed and cast, how the unique two-tone feature of a single bell was invented, and how an ensemble of chime bells was formed. As a result, this article focuses on how the re-creation of ancient artifacts benefits, in return, our research into the ancient artifacts themselves.

The re-creation of ancient artifacts can pioneer new methodologies in the field of digital humanities. This process currently involves, both digitally and physically, the re-creation of missing parts from damaged artifacts for restoration purposes, as well as the reproduction of entire artifacts for display and educational purposes (Hu et al. 2009; Zhang, 2016; Weng and Xin, 2016; Debut et al. 2016, 2018; Cekus et al. 2020; Carvalho et al. 2021; Parfenov et al. 2022; Fang et al. 2022). Artifact replication also constitutes a large-scale business sector since these newly created items can be sold as metalcraft items or even as forgeries masquerading as antiques (Zhang, 2016, p. 60). Given this rich background of development in digital humanities, the re-creation of ancient artifacts provides the immense potential to make significant contributions to historical studies, particularly in the non-textual realm. Many current digital humanities projects in historical studies focus primarily on using text-based approaches to extract historical patterns (Burdick et al. 2012, pp. 30–60, 122–123; Svensson et al. 2012). By contrast, the re-creation of ancient Chinese bells does not depend on textual sources. Since casters from the period under discussion in this article left no textual records, in order to explore the mindset of those ancient bell casters, there is a need to establish such new, non-text-based methodologies.

Ancient Chinese bronze chime bells possess many unique characteristics compared to bells that were produced around the rest of the world (Ma, 1981; Shen, 1987; Lehr, 1987, 1988, 2005). One of their most notable features is their almond-shaped cross-section, which is distinct from the round shape of other bells. This unique shape enables each bell to produce two distinct absolute pitches depending on where it is struck (Huang, 1978–1980; Chen and Zheng, 1980; Dai, 1980; Ma, 1981; Shen, 1987; Lehr, 1988; Falkenhausen, 1993, pp. 67–97; 2018, 2023). The almond shape also results in shorter sounds, making these bells suitable for ensemble performances, as opposed to the longer, monotone produced by round bells (Dai, 1980; Falkenhausen, 1993, pp. 67–97, 2023; Bagley, 2005, pp. 54–55). Bronze, being a non-perishable material, ensures the durability of these bells. This enduring nature of this material, if well-preserved, means that the sounds produced by these bells in the present day are likely to be similar to those produced by the same bells in ancient times (Bagley, 2000, p. 36). We can, therefore, use the bell sounds generated in the present day to study how the bells may have sounded in ancient times and how musicians of that era interpreted bell music.

In this article, we aim to answer the following series of questions regarding the design and production of ancient bells by using our newly re-created bells.

Question (Q)1: Was the replication of bells practiced in ancient times?

Q2: If the answer to Q1 is yes, were the replication methods used in ancient times similar to those used today?

Q3: If a bell was re-created, did its two tones remain unchanged, or if not, how were they changed?

Q4: How did casters know before casting what two tones a bell could generate?

Q5: How was the two-tone feature invented and developed?

Q6: How did a set of two-tone bells form a musical ensemble?

While many unsolvable mysteries remain in this historical field, addressing these six questions will provide valuable data for future research.

Modern practices of bell restoration and replication

Conservators employ extensive re-creation methods to reproduce or repair bells. For example, a team of conservators undertook the restoration of a broken bell from the church of S. Pedro de Coruche in Lisbon, Portugal, dating to around the 13th century CE, which was believed to be incapable of generating its original sound (Debut et al. 2016). Using 3D scanning technologies, this team processed the 3D-scanned model of the broken bell in professional 3D software and digitally re-created the missing portion of the bell. They then 3D-printed the missing portion in metal and affixed it to the broken bell, which enabled it to once again emit a clear tone. In China, similar restoration efforts have been made, albeit with greater complexity due to the two-tone feature of their ancient bells (Hu et al. 2009; Falkenhausen 2018, pp. 45–50; Fang et al. 2022). It is crucial that the shape and pitch of a bell after repair need to be as close as possible to those of the original bell. A team of conservators in the Hubei Provincial Museum, who repaired a group of large bells by soldering them, did successfully make them clearly produce their distinctive two tones. Another team of conservators at the same museum used 3D printing in their restoration process. They digitally modeled the shape and size of the missing sections and 3D-printed them in resin. Those resin models were used to create wax models, which in turn were used in a lost-wax casting method (Fang et al. 2022), with molds prepared from the wax models, into which molten bronze was poured. When solidified, the newly-cast sections were soldered onto the broken bell. These cases serve as classic examples of repairing bells as musical instruments.

Another prevalent practice is the reproduction of whole bells. The 3D scanning and printing technologies outlined above can be applied to the reproduction of entire bells, and other techniques and materials such as plaster and silicone have also been used (Hubei, 1981, p. 4; Hu et al. 1981). In historical and modern Europe, church chime bells can be replicated by using wooden strickles of pre-determined sizes and shapes in order to form the shapes and sizes of bell models (Lehr, 2005, pp. 12–18; O’Brien, 2021). Any model could subsequently be produced in exactly the same size and shape as the desired bell. While there may or may not be a pre-designed bell model for direct replication, this process can still be considered a form of replication.

In contemporary China, bell replication has evolved into a substantial industry that utilizes modern metallurgical knowledge and technology. This development largely stemmed from the discovery and replication of the chime bell set excavated from the famous tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng (died circa 433 BCE) (Hubei, 1981, 1983; Hu et al. 1981; Zhang, 1985). This bell set comprises sixty-five bronze bells spanning more than three octaves, which are tuned to the chromatic scale. The knowledge at that time of the twelve semitones within an octave is demonstrated by all pitches that are provided by the bells and the then-existing musical theories that are inscribed on them. Modern musicians, recognizing the immense value of replicating this bell set, initiated the practice of their replication in the 1980s (Hubei, 1981; Wang, 2012, 2021, pp. 1–47; Li, 2012). Collaborative teams consisting of archeologists, musicians, acousticians, metallurgists, and traditional casters were assembled to take part in replication experiments. They employed various types of molding silicone to imitate the exact size and shape of the bells, conducted a comprehensive analysis of the metallurgical composition of the bell alloy, and prepared crucibles of molten bronze according to that alloy ratio. The newly-cast bells did, therefore, closely resemble the original bells in terms of size, shape, wall thickness, and metallurgical composition. These teams also acknowledged, however, that the newly-cast bells required fine-tuning in the post-processing process to ensure that the two tones of each bell would closely match those of the original (Wang, 2012, pp. 48–49). Numerous further bell sets, as well as the Zeng Hou Yi bells, have since been replicated, with the factories undertaking these replication experiments amassing a wealth of experience (Zheng, 1998; Hua, 2004; Li, 2012; Ren, 2013; Wang, 2012, 2021, pp. 1–47, 101–231, 356–385).

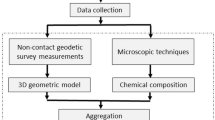

Our digital and physical re-creation methods

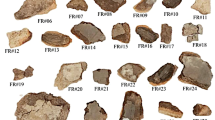

Our re-creation methods have utilized both digital and physical aspects. The first sample set we selected is from bronze bells excavated from multiple sacrificial pits at the site of the Construction Bank of China in Xinzheng county, Zhengzhou city, Henan, which date to about 500 BCE (hereafter “the Xinzheng bells”) (Henan, 2006, vol 1, pp. 311–327; Wang, 2006; Falkenhausen, 2009, 2018, 2023, pp. 230–31). We 3D-scanned some of the Xinzheng bells and generated their corresponding 3D models using professional software. The white-light 3D scanner used was the Artec Eva scanner, which provides an accuracy of up to 0.1 mm. Our 3D models were generated in both formats of mesh and point cloud. In order to validate the accuracy and precision of these 3D models, we scanned a modern camel sculpture twice and superimposed the two 3D models together for comparison (Fig. 1). Using the professional software provided by the scanner company, Artec Studio 11, we demonstrated an ideal overlap between the two 3D camel models. This example implies that each 3D model generated for our subsequent comparison experiments is sufficiently accurate and precise for our study purposes.

a The modern camel sculpture we 3D-scanned. b The first 3D computer model generated. c The second 3D computer model was generated. d Point cloud of the two 3D models, when superimposed. e The two overlapped 3D models are shown in blue and red. Photograph and images by the author. This figure is not covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Reproduced with permission of Kin Sum Li; copyright © Kin Sum Li, all rights reserved.

In the subsequent simulation experiments, we used the digital 3D computer models of the Xinzheng bells to create 3D-printed resin models and sent these resin models to a foundry for casting. The foundry workers used the resin models as the equivalent of wax models in their lost-wax casting process. As such, they would encase a resin model in soft, wet clay and allow the clay to dry to form the clay mold. The mold was then heated to a temperature at which the resin softened and was drained out, leaving a cavity in the shape of the original bell. The molten metal that was then poured into the mold upon solidification became a new metal bell corresponding to the original bell, referred to as a “surmoulage” (Li, 2017, p. 262). They also used the indirect lost-wax casting technique to replicate the resin models. In this way, they could replicate as many as they desired, provided that they retained the original resin model (Peng, 2023).

Due to budget and local environmental issues, brass, an alloy composed of 79–83% copper, 7–9% zinc, and 10–12% tin, was used to cast these new bells, although ancient Chinese casters did not use brass until the tenth to fifteenth century CE. We did not use the same metallurgical composition as the original bronze bells, which contained 73–84.6% copper, 8.5–12.5% tin, and 6.9–11.1% lead (Huang and Li, 2006).Footnote 1 These ratios, as tested from the original bells, may have varied slightly, within an acceptable range, due to factors such as corrosion and sampling position. One factor that we initially overlooked was the approximate 1.05% contraction rate of the newly cast bells. In consequence, the new bells are slightly smaller than the originals. For example, for the original bell with a side length of 20 centimeters (cm), its corresponding new counterpart measures approximately 19.8 cm, and the counterpart of a 40 cm original bell measures 39.5 cm. Although metal contraction is inevitable in making surmoulages, these were mistakes that we must acknowledge and rectify in future experiments. However, at this stage, we have found that the different alloys and the contraction rate did not result in significant discrepancies in their tones, a point which will be elaborated upon in the following sections. Since we aimed to imitate only the design and production process of the original bells, in order to retain the raw, original two tones of each new bell, we did not fine-tune these newly cast bells.

After casting the new bells, we used a wooden mallet to strike each one in order to generate its two tones. Each bell has two A-tone and four B-tone positions (Fig. 2), and we struck every position three times, recording the tones using the professional software “Audacity”.Footnote 2 Only the fundamental tone of each vibration was documented, with overtones ignored since they were probably not the sounds sought by ancient musicians. These fundamental tones were then converted from hertz to musical notes and recorded in the international scientific notation format (A4 = 440 Hz). In our analyses, we use the musical notes of the two tones of each bell for comparison with other bells. The same testing method was used to record and analyze all of the ancient and newly cast bells.

The two shown here are bells Pit16–G1x and –G1y from Xinzheng, Henan. Photograph by the author. After Li et al. (2024a, p. 4 of 14, Fig. 2). This figure is covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Reproduced with permission of Kin Sum Li; copyright © Kin Sum Li, all rights reserved.

We established constants and variables for our experiments. The constants were factors that mostly remained unchanged, including but not limited to the force and gesture used to strike the bells. The shape of the bell was kept proportional. The variables referred to factors leading to changes in the bell tones. For example, we altered the size and mass of the bells to observe how they correspondingly impacted their tones.

Replication phenomenon in 500 BCE

To address the first question (Q1) posed above, we did indeed find evidence of bell replication around 500 BCE in Xinzheng (Fig. 2), as demonstrated by our superimposed 3D models (Fig. 3). This is the first time that the practice of bell replication has been seen in archeological records of ancient China (Li et al. 2021, p. 141). Figure 3 shows the result of superimposing 3D models of two bells discovered in Pit 16 in Xinzheng, specifically bells no. G2x and G2y (originally numbered A2 and B2; see also Table 1). It is evident that the overall size, shape, and wall thickness of the two overlapped bells align perfectly. Table 1 also reveals that the measurement data of their overall size and shape are strikingly similar. Their two tones are nearly the same, as both bells’ A-tones are D5, while their B-tones are E5 and F5. Given that E5 and F5 are adjacent semitones and considering the technological level of the era, we can conclude that their two tones are almost the same, indicating that they are a pair of bells that were successfully replicated in around 500 BCE. Figure 3 does not show any protrusions, which suggests that their original model was not substantially different. In other words, they originated from the same rough clay model, and their clay molds are highly similar (Daxi (Shanxi), p. 86).

a View of the textured models of the two bells’ mouths. b Two textured models overlapped. c–g Different views of the point clouds of the two superimposed 3D models. Images by the author. After Li et al. (2024a, p. 11 of 14, Fig. 9). This figure is covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Reproduced with permission of Kin Sum Li; copyright © Kin Sum Li, all rights reserved.

The reason for stating that they could not have shared the same mold in ancient times is that the clay molds would not have been re-usable having been smashed open to retrieve the bell after the molten bronze solidified (Bagley, 2009). They were, moreover, cast using the section-mold method rather than the lost-wax method. This difference resulted in mold marks on the bells cast by the section-mold method, whereas bells cast by the lost-wax method did not bear any mold marks (Bagley, 2009; Peng, 2023, p. 9). Therefore, while their molds might have appeared to be highly similar, they were not the same actual mold. Casters could further decorate their molds by adding patterns or altering minor parts, such as the patterns on their handles, and as a result, minor parts such as handles may have differed from each other. However, the bells’ overall size, shape, and wall thickness remained identical.

From these observations, it is clear that ancient casters did not use the lost-wax method that is commonly used today (Q2). Instead, they used the section-mold method, in which the mold was sliced into sections and re-assembled when the model was removed. They also decorated directly onto the mold. Their final, cast bells would exhibit slight differences from the original model. They merely replicated the general size, shape, cavity, and wall thickness of the original bells. These factors are crucial to the tonal similarities between the original and the surmoulage bells. On the other hand, the patterns and minor parts, which did not need to be completely replicated, are not significant factors in the tones that the bells generate.

Our reproduction in 2023 CE

Variable 1: Material

A further question arose above as to whether the two tones of a replicated, surmoulage bell would be the same as those of the original bell (Q3). In order to address this question, we selected the Xinzheng Pit16–G2x bell to use as the prototype from which to cast a series of new bells (Fig. 4, Table 2). We cast sixteen bells in total, and divided them into four distinct types (A–D), with each type consisting of four bells. We will discuss the Type A bells first.

a The four different 3D computer models created based on the original Xinzheng Pit16–G2x bell with a side length of 20 cm. The side lengths of the other 3D computer bell models, as specified in the sub-image, are 10 cm (100 mm), 30 cm, and 40 cm respectively. b One of the 3D-printed resin models (Type B, side length 40 cm) based on the corresponding 3D computer model. c Some of the newly cast brass bells. d One of the largest brass bells (Type B, intended side length 40 cm, actual side length 39.6 cm), hung on a frame and ready for testing. e Type A, B, D brass bells stored on a wooden shelf (in total 12). f Type C bells (in total 4). Images and photographs by Chen Xueqing and the author. This figure is not covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Reproduced with permission of Kin Sum Li; copyright © Kin Sum Li, all rights reserved.

While other constants were maintained unchanged to ensure that the size, shape, and wall thickness of the new bells would be the same as those of the original bell (Type A in Table 2, intended side length 20 cm), the casting material was set as Variable 1. Conforming to the same proportion, we cast four brass bells for Type A based on the same resin model. The contraction rate may vary slightly in actual casting exercises due to a variety of factors. However, the dimension measurement results shown in Table 2 display that our newly cast brass bells are remarkably similar in size to the prototype bell.

The pitch testing results are documented in Table 3. The tones of these brass bells are notably clear and consistent. Readers are reminded that we struck each bell at least 18 times, with 3 strikes at each of the 6 A- and B-tone positions, and occasionally more. For Type A bells, usually, only one frequency was recorded for each of the two tones, which implies that the Type A bells were very well cast. The A-tones of all four brass bells span from F5 to F#5 (712–749 Hz), while the B-tones range from G#5 to A5 (840–886 Hz). Considering that we did not fine-tune the brass bells and that their tonal variances are confined to only neighboring semitones, it can be inferred that all four bells yield the same two tones. With the two tones of the original bell being D5 and E5 (Table 1), the two tones of each of the newly-cast Type A bells are merely elevated by one minor or major third. Owing to the consistent interval of the two tones of the new bells, we can infer that the tonal disparities are attributable to the different materials used, namely, the substitution of lead with zinc. If ancient casters had used the same alloy as in this study, it is highly plausible that they could have reproduced bells with strikingly similar two tones by replicating a bell’s size and shape.

If ancient casters started to work from a completely new model, it is highly plausible that they did not know what two tones a bell could generate before it was cast (Q4). Even today, we still do not clearly understand how to cast a bell from scratch with precise control over its two tones. Due to the tremendous effort required in calculation and experimentation, modern acousticians and engineers themselves find this task challenging. As far as the author is aware, to date no one has successfully achieved this feat. Modern European foundry workers, leveraging at least three to five centuries of experience, of which the history and tools of the Whitechapel church bell foundry provide evidence, can cast a round bell with one specific, desired tone (O’Brien, 2021). However, their technical expertise is limited to single-tone bells and they lack the knowledge and technology necessary for casting a two-tone bell. Similarly, modern Chinese foundry workers are unable to work successfully from a blank slate and can only cast a bell with two desired tones because they can replicate an existing bell with its two already-known tones. When ancient casters intended to cast a bell with two desired tones, they would, very probably, have first referred to a bell with two known tones and reproduced them by replicating that bell.

Variable 2: Size

We know that the almond-shape cross-section is a crucial element in creating a bell’s unique vibration, enabling it to generate two different pitches (Chen and Zheng, 1980; Dai, 1980; Ma, 1981; Shen, 1987). The almond-shaped cross-section design has a long history. Some pottery and bronze bells appearing before or around 1500 BCE, predominantly discovered in North China, were designed with this almond shape (Daxi (Henan), pp. 45–48; Bagley, 2000, p. 46). However, their acoustic properties remain largely unknown, due either to a lack of testing or to extensive corrosion that prevents the generation of sound of an acceptable quality. When continuing the search for almond-shaped bells of later eras, there are some dating to approximately the twelfth century BCE that are known, having been found in the Yangzi River areas of South China. These bells are notably larger and heavier than those found in the north (Bagley, 2000, pp. 46–48). More of these bells have been tested. In this era, these bells’ tones were clearer and more consistent, and the interval between a bell’s two tones could range from a major second to a major third, with occasionally no detectible difference between the two tones (Ma, 1981, p. 134). From 1000 BCE onward, a more consistent minor third or major third interval featured between a bell’s two tones. This interval later became a norm in the bell-casting industry for subsequent generations, whose bells also retained their almond shape (Ma, 1981, p. 134). It is impossible to rule out the ability of bells from 1500 to 1000 BCE to have produced two different pitches as, although their consistency is not on a par with those made after 1000 BCE, this characteristic has indeed been observed in them. We can acknowledge that the two-tone feature was invented and widely implemented during this era and that after 1000 BCE it became standardized (Q5).

How musicians and casters used the two-tone feature of each bell to develop music forms another query. While we know that after 1000 BCE, they were able to form a chime bell ensemble, it was not entirely clear whether they had already done so before then, namely in the period from 1500 to 1000 BCE (Q6). In order to understand the technical origins of chime bell ensembles, we need to explore the methods used to manipulate changes in the bell tones. While the exact process of how the first two-tone bells were invented and realized by musicians and casters remains unknown, experiments can be conducted with existing bells to tackle this issue.

In our experiments we focus on exploring how the two tones of a bell change as we adjust its size proportion (Falkenhausen and Rossing, 1995; Asahara, 2000). Since adjusting the shape of a bell would introduce too many variables, its size and mass are set as Variable 2 while keeping other factors, such as bell shape, constant. Using professional computer software, we adjusted the bell size and proportion according to the ratios set in Table 2 (see also Fig. 4a). For instance, we first created the Type B bells. By enlarging the size of the Xinzheng Pit16–G2x bell while maintaining its shape resulted in, for example, the original 20 cm side length of the prototype bell being enlarged to 40 cm. All other parts, including the spine length and wall thickness, were enlarged proportionately, through the use of a simple automated software command. Using the same method, we increased the size slightly to create the Type D bells, changing the side length, for example, from 20 to 30 cm, whilst also proportionately enlarging the other parts. In a similar vein, we experimented with shrinking the size of the prototype bell to create the Type C bells (i.e., side length from 20 to 10 cm). While the bell walls became very thin at that size, the foundry workers did manage to cast from this model. As the size of the bells changed, their mass also changed correspondingly. Since we continued to use the same alloy ratio, the changed mass can also be considered as a form of change in size. We then had the three types of bells, Types B–D, 3D-printed in resin (Fig. 4b), and the foundry workers used their own techniques to cast bells with each type of resin model (Fig. 4c–f). The tones of these twelve bells were then tested, with the results documented in Table 3 (cf. Fig. 4d).

Table 2 demonstrates that the sizes of the actual cast bells closely match the intended dimensions for each type. Similarly, Table 3 shows that the tones produced by these bells are very clear and consistent too. However, it is occasionally hard to control the tones of extremely large or small bells, as tested on the Type B bells. The A-tones of the Type B bells exhibit minimal variation, whereas their B-tones appear to be relatively diverse.

To further analyze the relationship between bell size and tones, we selected one bell from each type and compared their tones in Tables 4 and 5, using the tones of the Type A starter bells for a more lucid comparison. To facilitate readers’ understanding of the chromatic scale, the twelve semitones from C to B are listed in the bottom row of Table 5, with the numbers of the octaves listed in the left-hand column. Since these sixteen newly cast bells are not fine-tuned, whereas in ancient China fine-tuning was common in order to adjust final bell pitches to accord with musicians’ requirements, variations or ranges in the tones should be allowed for in the pitches of our new bells. In Table 4 the accepted variation rate has been set as a major second. With this in mind, the A-tone of bell A4 (a musical note of F#5) should, therefore, be interpreted as a range of musical notes deviating from F#5. In ancient times, an experienced caster would have been able to fine-tune the A-tone of the bell, and of course, simultaneously its B-tone, to accommodate musicians’ demand for a set of harmonious instruments.

It can be seen that the relationship between bell size and tones has now become clearer (Table 5). If we proportionally enlarge the size of the bell to a certain degree (Type B), the two tones drop by an octave, shifting from F#5 and A5 to F#4 and A4. Conversely, if we proportionally reduce the bell size to a certain degree (Type C), the two tones rise by an octave, reaching G6 and A#6. Fine-tuning would make these tones neater and closer. The two tones of the Type D bells would sit midway between those of the Type B and Type A bells.

This may seem at first glance to align with the principles of Pythagorean arithmetic, which was probably not, however, a viable method for casters in the twelfth century BCE to have been able to discover or realize the chromatic scale (Bagley, 2005, pp. 86–88). According to Pythagorean tuning theory, the vibration frequency, or the pitch, of a string will be an octave higher when plucked in comparison to a string double its length and an octave lower when compared to a string half its length (Adkins, 2001, p. 3). When the string length is shortened according to other certain ratios, such as 2/3 and 3/4 or..., intervals of a perfect fifth and a perfect fourth are obtained, respectively. The Pythagorean method of calculating intervals does, however, fall short when attempting to calculate all the equal semitones of the chromatic scale, since the calculation of other equal semitones becomes significantly more complex (seeking the twelfth root of two in the equal-semitone chromatic scale) (Kuttner, 1975; Adkins, 2001; Cho, 2003). In the context of bell-casting, numerous uncertainties and variables would have surfaced, which would have made the calculation of appropriate bell sizes even more challenging. This remains one of the reasons why modern acousticians and engineers still struggle to precisely manipulate bell size and tones.Footnote 3

The experiments we have undertaken shed light on the initial relationship between bell size and tones. They have shown that enlarging and reducing the size of the starter bell to a certain degree roughly lowers or raises the tones, respectively, by one octave. Simple arithmetic does not, however, hold true for bells of sizes falling between the largest and smallest bells, and casters and musicians would have had to use different methods to create bells in order to attain the other semitones in this range.

Bell casting and the multiple discoveries of the chromatic scale

Achieving desired tones by proportionately adjusting the size of the starter bell presents a straightforward method by which to produce instruments that span two octaves. It was quite possible that ancient casters and musicians were aware of this technique, which would have been possible for them to achieve if they had conducted experiments based on this method. This would, however, only have enabled them to obtain the initial two tones, along with their corresponding two tones an octave higher, and another set of two tones an octave lower. They would still have had to grapple with the pitches within these two octaves. Nevertheless, this method would have enabled them to establish the starter bell, a double-sized bell, and a half-sized bell, thus providing them with a foundation for further exploration.

The discovery of the chromatic scale may have been achieved through a combination of hunting bells with compatible tones, experimentation, and transposition. As Robert Bagley argues, ancient bell musicians may have sought out bells with special tones that were unfamiliar to them but could be integrated into their existing list of tones within an octave (Bagley, 2000, p. 49). Musicians may have added these bells into their ensemble, either as a backup or for future musical experiments. The pursuit of more accurate and precise methods of transposition could also have prompted them to discover more semitones. Bagley posits that musicians in the Ningxiang area in the twelfth century BCE had already realized the chromatic scale since at least seven of the twelve semitones can be found on the ten Ningxiang bells (Bagley, 2005, pp. 79–85). A recent pitch test conducted by the author of this article further confirmed the existence of at least nine to ten consecutive semitones on the Ningxiang bells (Li et al. 2024b, p. 12). This evidence is not likely to be coincidental, but rather bearing testament to the achievement of the chromatic scale by the Hunan casters and musicians of the twelfth century BCE. Considering the maturity of the techniques, the process of attaining the chromatic scale might, in fact, have occurred even earlier than the twelfth century BCE.

Bell casters could well have experimented with the changing relationship between bell size and tones while maintaining the same bell shape. They would have discovered that by slightly altering the size of a bell, its two tones would correspondingly change. For example, if casters had scraped a small quantity of clay from the clay model of the double-sized bell, and used this modified model to cast a new bell, they could have achieved two higher tones. Alternatively, they could have started from the half-sized bell model and gradually, little by little, enlarged subsequent models. They could also have incrementally enlarged or reduced the size of the starter bell. Any of these three ways would have been effective, and the sequence in which they were applied would not have been important. The critical matter would have been to obtain the tones that would meet the needs of an ensemble that had adopted the chromatic scale, and a process of experimentation and adjustment would have been key to musical development.

This hypothesis can be corroborated by the evidence presented in Table 6 of bells found in the Middle Yangzi River area that share highly similar patterns and shapes. Despite having been discovered in various locations across the provinces of Hunan and Jiangxi, their strikingly similar decorative patterns indicate that it is highly possible for these bells to have been produced by the same workshop (Fig. 5). Given the geographical locations of the discoveries and the widespread availability of water transportation throughout the region, it is plausible that the bells could have been easily transported between these different locations. As shown in Table 6, even more compelling reasons supporting this notion can be derived from the size and tonal relationships between these bells.

a The Hunan-Ningxiang-Beifengtan-four-tigers bell. b The Hunan-Ningxiang-Shiguzhai-elephant1 bell. c The Hunan-Ningxiang-Shiguzhai-Feng2 bell. d The Hunan-Ningxiang-Shiguzhai-tiger1 bell. e The Beijing-Ningxiang-Shiguzhai-tiger2 bell. f The Hunan-Ningxiang-Shiguzhai-Feng1 bell. Photographs by the author. This figure is not covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Reproduced with permission of Kin Sum Li; copyright © Kin Sum Li, all rights reserved.

Table 6 links bells based on several criteria, including similar decorative patterns and shape (crucial typological markers), and nearly sequential two tones and size. Starting with the largest bell producing the lowest tones—the Hunan-Ningxiang-Yueshanpu bell, also known as “the nao king” and the largest nao-bell found until the present day—we see a series of bells gradually decreasing in size and producing progressively higher two tones. We must acknowledge the many missing links, as numerous bells with similar patterns have not had their two tones tested or documented. Many bells may no longer exist, having been melted down for re-casting, destroyed over time, or not having been located. Despite these gaps, Table 6 demonstrates the pattern of increasing two tones correlating with decreasing bell size. A comparison between the Hunan-Ningxiang-Shiguzhai-elephant1 bell and the Hunan-Zhuzhou-collect bell demonstrates that the two tones elevate from G#3 and A#3 to G#3 and B3, while the dimensions (side length, spine length, xianjian and gujian, wuxiu and wuguang) decrease. This suggests that the casters of the two bells were attempting to manipulate the size and tones, as by slightly reducing the size of the Zhuzhou bell, they could minutely raise its two tones. Similar hypotheses can be made when comparing the Hunan-Ningxiang-Chenjiawan bell, BPM-Wenwuju-transfer bell, ShanghaiM-collect-19976 bell, and many subsequent bells. Exceptions such as the Hunan-Ningxiang-Shiguzhai-Feng2 bell are few in number. Such anomalies are to be expected, given the then-experimental nature of bell casting and tone control and the levels of technology available during the ancient period, and taking into consideration that bell tones are, in any case, subject to a certain degree of variation. It can, however, be confidently inferred that, from the Hunan-Ningxiang-Chenjiawan bell to the Tianjin-BiKui-collect bell, ancient bell casters were experimenting with size adjustments to achieve their desired tones.

Evidence also suggests that ancient casters experimented with halving a bell size to achieve tones roughly an octave higher, or, conversely, doubling the size to achieve tones approximately an octave lower. In this case the former scenario seems more probable. This hypothesis is based on a comparison between the nao king (the Hunan-Ningxiang-Yueshanpu bell) and three other bells listed in Table 7. When the size of the nao king was halved, the casters created three bells. The two tones of these half-sized bells, C4 and D4, D4 and E4, and D#4 and F4, are almost an octave higher than the two tones, C3 and D3, of the nao king. While the data does not show a perfect relationship between the tones and size, if it is treated as data generated at the experimental stage, it shows that the casters were making a concentrated range of attempts to develop bells with a controlled range of tones. Since the data in Table 6 is from only a small number of bells and it covers tones generated over only a little more than two octaves, this hypothesis must end here and still awaits further research.

The explanation above reveals that the use of simple arithmetical processing is insufficient to achieve the desired bell size and two tones and that the process of tuning bells to desired tones required numerous trials and adjustments. Casters working during this period made substantial advancements, as evidenced by Tables 6–8, which demonstrate that they had almost mastered the chromatic scale. While Bagley’s theory is predicated on the 10 bells found together in one pit, our hypothesis draws upon a typological comparison of bells that may have been made in the same workshop, as well as the progressive changes in size and two tones outlined in Table 6. It must be reiterated that many bells listed in Table 6 have not yet undergone testing, rendering the pitch distribution in Table 8 incomplete. Despite this, Tables 6 and 8 already showcase the ancient casters and musicians’ remarkable comprehension and execution of the chromatic scale. While we suspect that the bell tones may extend into the No. 5 octave, to date, we lack sufficient evidence to confirm this. Nevertheless, the numerous tones that fill the grids of the twelve semitones in the Nos. 3 and 4 octaves present a newer perspective, as they indicate that casters were producing bells spanning over three octaves, all the while tuning them to the chromatic scale.Footnote 5

This process of the realization and attainment of the chromatic scale is likely to have occurred around or before the twelfth century BCE. Pythagoras (ca. 570–ca. 490 BCE) and his disciples in the West, as well as proponents of the Pythagorean tuning theory in China, worked for over around two millennia to calculate the twelve semitones within an octave.Footnote 6 They forcibly calculated ratio numbers to satisfy their pursuit of harmony in attaining the chromatic scale. It is now known, however, that there was more than one way to achieve the chromatic scale, one of which involved the creation and assembly of bells (Bagley, 2005). Repeated adjustments and experiments with bell size and the corresponding two tones would have allowed casters and musicians to attain the chromatic scale in a manner distinct from the Pythagorean arithmetic approach, as revealed by the impressive bell ensemble that is likely to have been produced by a single workshop in the Hunan area.

Conclusion

This article has endeavored to address the six questions we initially posed. Through our own experimental work, we have verified that bells were replicated around 500 BCE by using superimposed 3D bell models to develop evidence. While the replication methods used by casters at that time were distinct from ours, they successfully replicated the size and shape of the original bells, which were the crucial factors determining the two tones of the newly cast bells. Our simulation experiments show that the two tones of the replicated bells are very close to those of the original bells, albeit fine-tuning would be required to generate an exact match. This has led to the confirmation of our hypothesis that ancient casters could have replicated bells bearing two tones resembling those of the original ones. These ancient casters discovered the existence of the chromatic scale by seeking bells with tones that could be incorporated into their ensemble, by transposition, and by experimenting with bells of varying sizes. Our simulation experiments show that by changing the size of the starter bells, they could create new bells with tones roughly an octave lower or higher. They gradually adjusted the size of the bells, and through this method, rather than by calculation, they managed to produce bells that could generate the 12 semitones within an octave. They could subsequently use this method to cast many more bells in order to form an ensemble tuned to the chromatic scale. Our digital and physical re-creation of ancient Chinese bells has proved to be an innovative and successful approach to generating new knowledge about ancient Chinese bell music and bell casting.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Notes

This report describes that fragments or damaged areas of the bells were tested (Huang and Li, 2006, pp. 1001–1002). The mouths of eight niu-bells from Pits 7 and 16 and two bo-bells from Pits 4 and 16 were tested by using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) (Huang and Li, 2006, p. 1026).

Audacity Team (2021). Audacity(R): Free Audio Editor and Recorder [Computer application]. Version 3.1.3. Retrieved on August 9, 2021. Audacity® software is copyright © 1999–2021 Audacity Team. Website: https://audacityteam.org/. It is free software distributed under the terms of the GNU General Public License. The name Audacity® is a registered trademark.

For the purpose of distinction, the spirals on the bell handles are referred to as “G pattern,” and the spirals on the main register of the bell bodies as “spiral pattern.”

The upper register of the body of the Hunan-Yueyang-Feijiahe bell and many of its counterparts, along with the G pattern on the handles of numerous bells, show a close relationship with the taotie pattern on the main register of the bells. It would have been visually and mentally easy and straightforward for casters to adopt the spirals as another main decorative pattern.

This implies that bells adorned with the spiral pattern on their main register have a close association with the taotie-patterned bells. A list of the spiral-patterned bells will demonstrate another exciting version of pitch distribution.

It will be demonstrated in another article that the ten Ningxiang bells found in the same pit on the Shiguzhai hill were merely a portion of a larger ensemble.

References

Adkins C (2001) Monochord. In: Sadie S, Tyrrell J (Eds) The new Grove dictionary of music and musicians, vol 17, 2nd edn. Macmillan, pp 2–4

Asahara T 浅原達郎 (2000) Seishū kōki no henshō no sekkei—Jūshian dokukyūki shi san 西周後期の編鐘の設計―戎肆庵讀裘記之三― (Design of chime bells of later Western Zhou—reading notes of Jūshian). Tōhō gakuhō 東方學報 72:630–656

Bagley R (2000) Percussion. In: So JF (Ed) Music in the age of Confucius. Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution https://doi.org/10.5479/sil.850012.39088016680316

Bagley R (2015) Ancient Chinese bells and the origin of the chromatic scale. In: Center for the Study of Art and Archaeology, Zhejiang University (Ed) Zhejiang University Journal of Art and Archaeology, vol 2. Zhejiang University Press, pp 56–102

Bagley R (2005) Prehistory of Chinese music theory. Proc Br Acad 131:41–90

Bagley R (2009) Anyang mold-making and the decorated model. Artibus Asiae 69(1):39–90

Burdick A et al. (2012) Digital humanities. MIT Press

Carvalho M et al. (2021) Physical modelling techniques for the dynamical characterization and sound synthesis of historical bells. Herit Sci 157(9):1–17

Cekus D et al. (2020) Quality assessment of a manufactured bell using a 3D scanning process. Sensors 20(24). https://doi.org/10.3390/s20247057

Chen T 陳通, Zheng DR 鄭大瑞 (1980) Gudai bianzhong de shengxue texing 古代編鐘的聲學特性 (Acoustic properties of ancient chime bells). Shengxue xuebao 聲學學報 1980(3):161–171

Cho GJ (2003) The discovery of musical equal temperament in China and Europe in the sixteenth century. Edwin Mellen Press

Dai NZ 戴念祖 (1980) Gudai bianzhong fayin de wuli texing 古代編鐘發音的物理特性 (Physical properties of sound generation of ancient chime bells). Baike zhishi 百科知識 1980(8):68–71

(Daxi) Zhongguo yinyue wenwu daxi zongbianjibu 《中國音樂文物大系》總編輯部 (Ed) (1999–2007) Zhongguo yinyue wenwu daxi 中國音樂文物大系 (Catalogs of Chinese musical instruments). Series I, 10 vols, published in 1999: Shanghai juan Jiangsu juan 上海卷 江蘇卷; Beijing juan 北京卷; Sichuan juan 四川卷; Shandong juan 山東卷; Shanxi juan 山西卷; Xinjiang juan 新疆卷; Henan juan 河南卷; Hubei juan 湖北卷; Gansu juan 甘肅卷; Shaanxi juan Tianjin juan 陝西卷 天津卷. Series II, 6 vols, published in 2007: Jiangxi juan xu Henan juan 江西卷 續河南卷; Hebei juan 河北卷; Guangdong juan 廣東卷; Fujian jun 福建卷; Nei Menggu juan 內蒙古卷; Hunan juan 湖南卷. Daxiang Chubanshe

Debut V et al. (2016) The sound of bronze: virtual resurrection of a broken medieval bell. J Cult Herit 19:544–554

Debut V et al. (2018) Reverse engineering techniques for investigating the vibro-acoustics of historical bells. In: Tahar F et al. (Eds) International conference on acoustics and vibration ICAV 2018: advances in acoustics and vibration II. Springer, pp 218–226

Falkenhausen L (1993) Suspended music: chime-bells in the culture of Bronze Age China. University of California Press

Falkenhausen L (2009) The Xinzheng bronzes and their funerary contexts. In: So JF (Ed) Institute of Chinese Studies visiting professor lecture series (II). Chinese University of Hong Kong, pp 1–130

Falkenhausen L (2018) The earliest Chinese bells in light of new archaeological discoveries. In: Amelung I, Kurtz J (Eds) Reading the signs: Philology, history, prognostication. Festschrift for Michael Lackner. IUDICIUM Verlag GmbH, München

Falkenhausen L (2023) Ritual change in Late Bronze Age China: musical dimensions. In: Bujard M et al. (Eds) Temps, espace et destin: Mélanges offerts à Marc Kalinowski. Institut des Hautes Études Chinoises, Collège de France, pp 225–237

Falkenhausen L, Rossing TD (1995) Acoustical and musical studies on the Sackler bells. In: So JF (Ed) Eastern Zhou ritual bronzes from the Arthur M Sackler collections. The Arthur M Sackler, pp 431–485

Fang C 方晨 et al. (2022) Suizhou Wenfengta M1 (Zeng Hou Yu mu) chutu M1:2 yongzhong baohu xiufu 隨州文峰塔M1(曾侯與墓)出土M1:2甬鐘保護修復 (Protection and conservation of the M1:2 yong-bell from Suizhou Wenfengta M1 [Zeng Hou Yu’s tomb)) Jiang Han kaogu 江漢考古 2022(3):138–144

Henan (2006) Henan sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo 河南省文物考古研究所 (Ed) (2006) Xinzheng Zhengguo jisi yizhi 新鄭鄭國祭祀遺址 (Sacrificial ritual site of the state of Zheng at Xinzheng), 3 vols. Daxiang Chubanshe

Hu JX 胡家喜 et al. (1981) Caiyong guochan youji guixiangjiao fanmo fuzhi Zeng Hou Yi mu bianzhong chenggong 採用國產有機硅橡膠翻模複製曾侯乙墓編鐘成功 (A success of using domestically produced silicone rubber to replicate models for re-casting the Zeng Hou Yi chime bells). Jiang Han kaogu 江漢考古 1981(S1):37–40

Hu JX et al. (2009) Jiuliandun Zhanguo bianzhong xing sheng fuyuan yanjiu 九連墩戰國編鐘形聲復原研究 (A study of reconstructing the shape and sound of the Warring States chime bells at Jiuliandun). Wenwu baohu yu kaogu kexue 文物保護與考古科學 21(2):17–26

Hua JM 華覺明 (2004) Zeng Hou Yi bianzhong de yanjiu fuzhi 曾侯乙編鐘的研究複製 (Study and replication of the Zeng Hou Yi chime bells). Zhongguo wenhua yichan 中國文化遺產 2004(3):42–43

Huang XJ 黃曉娟, Li XH 李秀輝 (2006) Zhengguo jisi yizhi qingtongqi de fenxi jianding baogao 鄭國祭祀遺址青銅器的分析鑒定報告 (Test report of the bronzes at the sacrificial ritual site of the state of Zheng). In: Henan sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo (Ed) Xinzheng Zhengguo jisi yizhi, vol 2. Daxiang Chubanshe, pp 1001–1037

Huang XP 黃翔鵬 (1978–1980) Xinshiqi he Qingtong Shidai yizhi yinxiang ziliao yu woguo yinjie fazhanshi wenti (shang) 新石器和青銅時代已知音響資料與我國音階發展史問題(上) (Known sound-related materials from the Neolitic and Bronze Ages and problems in the development history of musical scales in our country [part A]). In: Yinyue luncong bianjibu 《音樂論叢》編輯部 (Ed), Yinyue luncong 音樂論叢, vol 1. pp 184–206; Xinshiqi he Qingtong Shidai yizhi yinxiang ziliao yu woguo yinjie fazhanshi wenti (xia) …下 (…[part B]), vol 3. Renmin Yinyue Chubanshe, pp 126–161

Hubei (1981) Zeng Hou Yi bianzhong fuzhi yanjiuzu 曾侯乙編鐘複製研究組 (1981) Duoxueke xiezuo gongguan de chengguo—Zeng Hou Yi bianzhong fuzhi de yanjiu yu shizhi jiben chenggong 多學科協作攻關的成果—曾侯乙編鐘複製的研究與試製基本成功 (Achievements of transdisciplinary collaboration—basically successful in studying and experimenting with the reconstruction of the Zeng Hou Yi chime bells). Jiang Han kaogu 江漢考古 1981(S1):1–4

Hubei (1983) Zeng Hou Yi bianzhong fuzhi yanjiuzu (1983) Zeng Hou Yi bianzhong fuzhi yanjiu zhong de kexue jishu gongzuo 曾侯乙編鐘複製研究中的科學技術工作 (Scientific and technological work in the study of the reconstruction of the Zeng Hou Yi chime bells). Wenwu 文物 1983(8):55–60

Hunan (2020) Yueyang shi wenlü guangdianju 岳陽市文旅廣電局 (2020) Yueyang Miluo xinfaxian Shangdai shoumianwen tongnao 岳陽汨羅新發現商代獸面紋銅鐃 (Shang dynasty bronze animal-faced nao-bell newly found in Miluo, Yueyang). News report. Website of Hunan Provincial Department of Culture and Tourism. https://whhlyt.hunan.gov.cn/whhlyt/news/sxxw/202011/t20201106_13952520.html. Accessed 31 Dec 2023

Hunt FV (1992) Origins in acoustics. Acoustical Society of America

Kuttner FA (1975) Prince Chu Tsai-Yü’s life and work: a re-evaluation of his contribution to equal temperament theory. Ethnomusicology 19(2):163–206

Lehr A (1987) From theory to practice. Music Percept 4(3):267–280

Lehr A (1988) The tuning of the bells of Marquis Yi. Acoustica 67:144–148

Lehr A (2005) Campanology textbook: the musical and technical aspects of swinging bells and carillons. Originally published in Dutch (translated to English: Schafer K). The Guild of Carillonneurs in North America

Li CY 李純一 (1996) Zhongguo shanggu chutu yueqi zonglun 中國上古出土樂器綜論 (A comprehensive discussion of excavatedmusical instruments from ancient China). Wenwu Chubanshe

Li KS (2017) The component-model method of mirror manufacture in 300 BCE China. Arch Asian Art 67(2):257–276. https://doi.org/10.1215/00666637-4229728

Li KS et al. (2021) Decorated model, replication, and assembly line of the bronze industrial production in 500 BCE China. Early China 44:109–142

Li KS et al. (2024a) Potential scale of industrial outputs of the bronze bell casting industry in 500 BCE China. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 16:14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-024-01979-6

Li KS et al. (2024b) A “set” of ancient bronze bells excavated in Changsha, Hunan Province, China. Herit Sci 12:264. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01377-0

Li MA 李明安 (2012) Fuyuan Zeng Hou Yi bianzhong de shijian ji gongyi tupo 復原曾侯乙編鐘的實踐及工藝突破 (Breakthroughs in practices and artistry in the reconstruction of the Zeng Hou Yi chime bells). Zhongguo yinyue (jikan) 中國音樂(季刊) 2012(4):61–64

Ma CY 馬承源 (1981) Shang Zhou qingtong shuangyinzhong 商周青銅雙音鐘 (Bronze two-toned bells of the Shang and Zhou dynasties). Kaogu xuebao 考古學報 1981(1):131–146

O’Brien H (2021) The bell v. the boutique hotel: the battle to save Britain’s oldest factory. News report. The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/news/2021/may/11/whitechapel-bell-foundry-battle-save-britains-oldest-factory

Parfenov V et al. (2022) Use of 3D laser scanning and additive technologies for reconstruction of damaged and destroyed cultural heritage objects. Quantum Beam Sci 6(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/qubs6010011

Peng P (2023) Between piece molds and lost wax: the casting of a diatrete ornamentation in early China rethought. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10:456. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01984-5

Peng SF 彭適凡, Sun YM 孫一鳴 (2011) Zhejiang Wenzhou shi Ouhai Yangfushan tudunmu de niandai ji xiangguan wenti 浙江溫州市甌海楊府山土墩墓的年代及相關問題 (Dates of and related problems about the tumulus at Yangfushan, Ouhai, Wenzhou county, Zhejiang). Kaogu 考古 2011(9):71–81

Ren H 任宏 (2013) Zhongguo yinyue xueyuan yueqi bowuguan (chou) guyueqi fuyuan xilie huodong gaishu 中國音樂學院樂器博物館(籌)古樂器復原系列活動概述 (Brief report of the series of activities of the reconstruction of ancient musical instruments by the Museum of Musical Instruments, China Conservatory of Music). Zhongguo yinyue (jikan) 中國音樂(季刊) 2013(1):97–101

Shen SY (1987) Acoustics of ancient Chinese bells. Sci Am 256(4):104–110

Sun M 孫明 (2022) Xuanhe bogutu shoulu de jijian nanfang fengge Shang Zhou tongqin, tongnao yu bozhong 《宣和博古圖》收錄的幾件南方風格商周銅磬、銅鐃與鎛鐘 (Several Southern-styled bronze chime stones, bronze nao- and bo-bells from the Shang and Zhou dynasties, recorded in the Catalog of Xuanhe antiquities). Hunan bowuyuan yuankan 湖南博物院院刊 18:193–202

Svensson P et al. (2012) Beyond the big tent. Blog posts. In: Gold M (Ed) Debates in the digital humanities. University of Minnesota Press, pp 36–71

Wang ZC 王子初 (2006) Zhengguo jisi yizhi chutu bianzhong de kaocha he yanjiu 鄭國祭祀遺址出土編鐘的考察和研究 (Exploration and study of the chime bells excavated at the sacrificial ritual site of the state of Zheng). In: Henan sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo (Ed) Xinzheng Zhengguo jisi yizhi, vol 2. Daxiang Chubanshe, pp 951–994

Wang ZC (2012) Fuyuan Zeng Hou Yi bianzhong jiqi sheji linian 復原曾侯乙編鐘及其設計理念 (Reconstruction of the Zeng Hou Yi chime bells and its design ideas). Zhongguo yinyue (jikan) 中國音樂(季刊) 2012(4):42–49

Wang ZC (2021) Suijin fenghua: yinyue wenwu de fuzhi, fuyuan yanjiu 碎金風華: 音樂文物的複製、復原研究 (Splendors of the fragmentary bronzes: reconstruction and repairing study of musical antiquities). Kexue Chubanshe

Weng ZW 翁志文, Xin MF 辛玫芬 (2016) Zeng Hou Yi fuzhi bianzhong zhi ceyin yanjiu 曾侯乙複製編鐘之測音研究 (Pitch test study of the reconstructed Zeng Hou Yi chime bells). Taiwan yinyue yanjiu 臺灣音樂研究 22:63–84

Zhang HL 張宏禮 (1985) Zeng Hou Yi bianzhong fuzhi yanjiu huo zhongda chengguo 曾侯乙編鐘複製研究獲重大成果 (Major outcomes achieved in the study of the reconstruction of the Zeng Hou Yi chime bells). Zhongguo keji shiliao 中國科技史料 6(2):56

Zhang Y 張寅 (2016) Guyueqi yinxiang fuyuan ji xiangguan gainian de taolun 古樂器音響復原及相關概念的討論 (Discussion of the reconstruction of ancient musical instruments and related concepts). Renmin yinyue 人民音樂 2016(9):60–62

Zheng RD 鄭榮達 (1998) Zeng Hou Yi bianzhong fuzhi de yinlü dingwei yanjiu 曾侯乙編鐘複製的音律定位研究 (Study of the determination of the musical scale of the reconstruction of the Zeng Hou Yi chime bells). Huangzhong (Wuhan yinyue xueyuan xuebao) 黃鐘(武漢音樂學院學報) 1998(3):30–34

Acknowledgements

The work described in this paper was partially supported by grants from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR), People’s Republic of China (Project No. HKBU 12618422), and Quality Education Fund E-Learning Ancillary Facilities Program (2021/0257). Sincere appreciation is extended to all curators and staff at the museums and archeological institutes referenced in this article, especially Liu Haiwang of the Henan Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archeology, Liu Yu of the Changsha Museum, Nie Fei, Yu Lixin, and student helpers involved in the experiments. Special thanks go to my former students at HKBU, David Tsang and Venus Ng, for meticulously compiling the initial bell database. All remaining errors belong to the author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The author is responsible for the content of this article and bears all responsibilities.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests. The author was a member of the Editorial Board of this journal at the time of acceptance for publication. The manuscript was assessed in line with the journal’s standard editorial processes.

Ethical statement

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by the author.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, K.S. Digital and physical re-creation of ancient Chinese bells: new understandings and discoveries. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 48 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04133-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04133-8